Case-based learning: acute diarrhoea

SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand the various causes of acute diarrhoea

- Elicit the necessary information to guide management

- Effectively manage patients presenting with acute diarrhoea

- Know when to refer patients for medical review

Diarrhoea is defined as the passage of three or more loose stools in 24 hours, or defecation more frequent than what is normal for an individual [1] . Diarrhoea can be classified as:

- Acute — symptoms lasting less than 14 days;

- Persistent — symptoms lasting more than 14 days; or

- Chronic — symptoms of more than 4 weeks duration [1] .

This article discusses the diagnosis and management of acute diarrhoea and when pharmacists should refer patients for a further medical opinion.

Acute diarrhoea has a considerable impact on UK morbidity. Approximately 50% of acute diarrhoea patients report absence from work or school and around 25% of the UK population is affected by infectious diarrhoea annually [2,3] . During the winter months, gastroenteritis also carries a significant financial burden, costing the NHS an estimated £7m to £10m per year owing to resultant hospital bed closures and staff sickness [4] .

Taking an accurate history is essential when assessing patients with diarrhoeal symptoms. The assessment should determine the onset, duration, frequency and severity of symptoms, the presence of any red flags and attempt to determine the underlying cause. It is also important to assess patients for complications, such as dehydration [4] .

Children or adults presenting at a pharmacy with faecal urgency, abdominal cramps, abdominal pain, frequent passing of loose, watery faeces, nausea and/or vomiting need to be assessed carefully [4] . Immediate referral is required if the patient presents with any ‘Red flag’ symptoms and signs of significant disease, which are summarised in Box 1 . Although most episodes of diarrhoea tend to be short lived, self limiting and benign, identifying cases that represent potentially serious illness can be a challenge [4] .

Box 1: Red flag symptoms [5–8]

Patients presenting with ‘one or more’ of the following symptoms should be referred:

- Feeling generally unwell with fever and vomiting — risk of severe dehydration;

- Age <6 months with symptoms >24 hours duration — refer immediately and provide oral rehydration salts immediately;

- Infants with sunken fontanelle;

- Age >6 months with symptoms >48 hours duration;

- Vomiting or unable to tolerate oral rehydration;

- Pre-existing medical conditions worsened by diarrhoea (e.g. diabetes, congestive heart failure);

- Immunocompromised or on immunosuppressive medications;

- Abdominal pain;

- Blood or mucus in stool;

- Bleeding from rectum;

- Evidence of dehydration (e.g. skin turgor) or shock (e.g. tachycardia, systolic blood pressure <90mmHg, weakness, confusion, oliguria or anuria, marked peripheral vasoconstriction);

- Unintentional weight loss;

- Ongoing diarrhoea after recent completion of an antibiotic course;

- Nocturnal symptoms;

- Abdominal or rectal mass.

Pharmacists should use their clinical judgement when deciding on the urgency of the referral and whether it is necessary to refer to the GP or urgent care.

The majority (90%) of acute diarrhoea cases are associated with bacterial or viral infection [5] . Norovirus and Campylobacter are the most common diarrhoea-causing agents in the community [5] . Travellers’ diarrhoea can be caused by bacteria and parasites such as Escherichia coli, Campylobacter, Shigella and Salmonella [9] .

Other causes of acute diarrhoea include food allergies (products containing sorbitol), alcohol, excess stress, recent pelvic irradiation, medication side effects (e.g. non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs] or antibiotics) and acute flares of chronic inflammation, such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, which affect water reabsorption in the colon resulting in loose and/or watery stools [7] .

There are many causes of acute diarrhoea in babies, most commonly viral gastroenteritis; however, the cause may be extra-intestinal (such as mening i tis , chest infection, ear infection or a urinary tract infection) [5] .

Eliciting an accurate history of symptoms is the most effective way of diagnosing acute diarrhoea and will guide the choice of management. Box 2 summarises the questions pharmacists should ask to guide patient assessment.

Box 2: Questions to ask during a consultation with a patient experiencing diarrhoea

“When did it start?”

Onset of symptoms:

- Within one to two days of ingesting food suggests contaminated food ( Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella or E. coli , Bacillus cereus toxin or norovirus) [10,11]

“What does it look like?”

Amount, consistency and frequency [12] :

- Higher volume and/or frequency of watery stools;

- Blood, mucus and/or pus in stools suggest severe inflammation and/or infectious cause;

- Mucus and pus indicate a chronic inflammatory cause or infective pathogen.

“How do you feel?”

Associated symptoms:

- Pain, bloating, nausea, vomiting, fever, tenesmus;

- Thirsty but no appetite;

- What does the patient look like? Ill or well, nutritional status, fever?

“Where have you been recently?”

Travel, diet and lifestyle [6,9] :

- Recent travel or consumption of foods, such as meat, eggs, dairy or seafood, are suggestive of infection. Ask about any recent picnics or barbecues as well as water intake;

- Exposure to pets or cattle suggests infectious cause;

- Individuals who work in day care centres, hospitals or nursing homes suggests infection;

- Social history, such as sexual practice, alcohol use or drug use;

- Family history of cancer, irritable bowel disease (prevalence 0.5–1.0%), coeliac disease (prevalence of 0.5–1.0%) or irritable bowel syndrome (prevalence 10.0–13.0%).

Patients who are systemically unwell — such as those recently admitted to hospital and/or taking antibiotics, who have blood or pus in their stool, or who are immunocompromised — must be referred for further investigation involving routine microbiology of stool samples [3] .

Testing for Clostridium difficile infection is also warranted for patients who have recently completed a course of antibiotics, are on a proton pump inhibitor, have been recently discharged from hospital, or have recently returned from foreign travel [7] . Additional testing for ova, cysts and parasites, including amoebae, Giardia or Cryptosporidium, is also recommended following travel abroad, particularly if diarrhoea is persistent (≥14 days) or the person has travelled to an at-risk area, such as Africa, Latin America, the Middle East and most parts of Asia [3,9] . Box 3 summarises the diet and personal hygiene measures travellers should follow to reduce their risk of developing travellers’ diarrhoea.

Patient advice

It is important that pharmacists provide patients and carers with the following advice to help manage symptoms [13] .

- Stay at home and get plenty of rest;

- Drink lots of fluids, such as water or squash — take small sips if you feel sick;

- Eat when you feel able to — you do not need to eat or avoid any specific foods;

- Take paracetamol if you’re in discomfort — check the leaflet before giving it to a child.

- Carry on breast or bottle feeding your baby — if they’re being sick, try giving small feeds more often than usual;

- Give babies on formula or solid foods small sips of water between feeds;

- Have fruit juice or fizzy drinks — they can make diarrhoea worse;

- Make baby formula weaker — prepare formula at its usual strength;

- Give children aged under 12 years medicine to stop diarrhoea;

- Give aspirin to children aged under 16 years.

If the patient works with older people or young children, they may pose a risk of passing on the infection. Provide infection prevention and control advice as summarised below [13] :

- Wash your hands with soap and water frequently;

- Wash any clothing or bedding that has faeces or vomit on it separately on a hot wash;

- Clean toilet seats, flush handles, taps, surfaces and door handles every day.

- Prepare food for other people, if possible;

- Share towels, flannels, cutlery or utensils;

- Use a swimming pool until two weeks after the symptoms stop.

Return to work should be delayed until 48 hours after symptoms resolve and if symptoms do not improve or resolve within 1 week of onset, the patient should ring NHS 111 or visit their GP for further investigation of the cause [13] .

There is a high risk of dehydration associated with acute diarrhoea, particularly in young children, frail people and older people [5,7,14] . It is important to assess the level of dehydration ( see Box 1 ) and determine whether referral is needed or if the patient can be safely managed with over-the-counter treatments, such as oral rehydration therapy (ORT). In severe dehydration (e.g. caused by dysentery and cholera), patients may require referral for intravenous hydration [5,7,14] .

Oral rehydration therapy

Fluid and electrolyte depletion caused by diarrhoea is often prevented or reversed by ORT. Dehydration is the most common complication of acute diarrhoea and correction of hydration is best done with an orally administered low-osmolarity (i.e. hypotonic) alkaline rehydration solution containing glucose and sodium (240–250 mOsm/L) [5] .

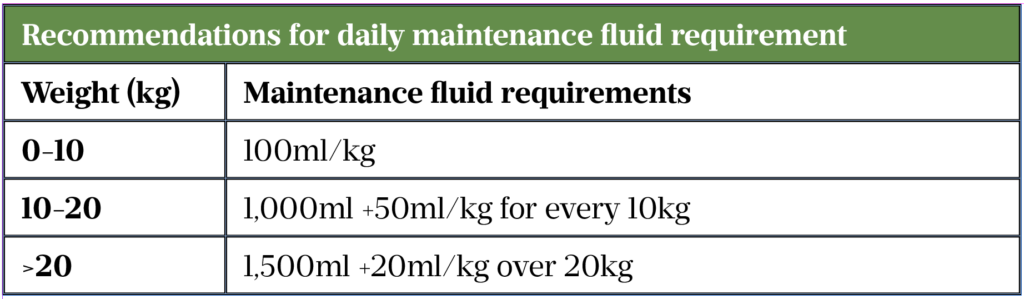

Each oral rehydration sachet (ORS) should be reconstituted with 200ml of water (freshly boiled and cooled water for children aged under 1 year) and may be kept at room temperature for up to 1 hour or in the fridge for up to 24 hours before discarding [5] . Frequent, small sips of refrigerated solutions may be more palatable and less likely to be regurgitated than giving a large volume quickly. When supplying ORS for children it may be helpful to provide an oral syringe for ease of administration. An alternative is to give the solution on a teaspoon or medicine spoon, or in a feeding bottle with a low flow teat. Administration of ORT to a healthy child is unlikely to cause any harm. Please see Table 1 for ORT recommendations.

Pharmacological treatment

Antidiarrhoeal agents are mostly opioid based and should only be used for short-term, rapid control of symptoms (such as travellers’ diarrhoea), but should be avoided if infection suspected ( see Case 1 ) [9] . Their use is limited by their actions on the central nervous system (CNS), which include CNS depression and the risk of dependence. Long-term use can also cause serious complications, such as toxic megacolon.

Loperamide is the antidiarrhoeal of choice for travellers, but should be avoided if blood or mucus is present in stools [9] . The recommended dosage is 4mg initially, followed by 2mg after each loose stool, up to 12mg a day for a maximum of 2 days if supplied over the counter or up to 16mg a day if prescribed [9] . In patients with short bowel syndrome, higher doses of orodispersible tablets should be prescribed owing to rapid intestinal transit times and minimal absorption [16] . The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency reports serious cardiac adverse reactions at high doses and recommends caution [17] . Notable side effects include drowsiness, headache, constipation, nausea and flatulence.

Codeine increases the risk of colonic perforation if used in acute infective diarrhoea and should not be recommended [18,19] . However, in stoma patients with shorter transit time and reduced absorption, codeine is given at doses of 15–30mg up to every 4 hours, titrated to response [19] . Pharmacists should monitor patients for the usual opioid side effects, such as drowsiness and constipation [19] .

Antimotility agents

Antimotility drugs should not be used in patients with a high fever or blood and/or mucus present in their stool (dysentery), or in confirmed E. coli (VTEC) or Shigellosis infections [20] .

Co-phenotrope (atropine 25 micrograms and diphenoxylate 2.5mg) is licensed as an adjunct to rehydration in acute diarrhoea but effectiveness is debatable. The recommended dosage is four tablets initially followed by two tablets every six hours until diarrhoea is controlled [20] .

Racecadotril, an enkephalinase inhibitor, is licensed as an adjunct to rehydration. It is currently not available in the UK for adults and the Scottish Medicines Consortium advised against the use in children owing to insufficient evidence [21] .

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are not recommended in view of the infection being most likely viral, but are occasionally used for prophylaxis of travellers’ diarrhoea (e.g. ciprofloxacin) [22] .

Advice for continuing care

In most cases, acute diarrhoea symptoms resolve within five to seven days [7,13] .

Individuals should not return to work until 48 hours after their symptoms have resolved [13] . If symptoms do not improve or resolve after a week, the patient should be referred for further investigation [13] .

It is essential to maintain good hydration with ORT [13] and antidiarrhoeals must be stopped immediately if symptoms of ileus, constipation or abdominal distension are present [23] .

Box 3: Diet and personal hygiene measures to prevent travellers’ diarrhoea [9]

Foods and beverages to be avoided while travelling:

- Raw or undercooked meats, fish and seafood;

- Unpasteurised milk, cheese, ice cream and other dairy products;

- Tap water and ice cubes;

- Cold sauces and toppings;

- Ground-grown leafy greens, vegetables and fruit;

- Cooked foods that have stood at room temperature in warm environments;

- Food from street vendors, unless freshly prepared and served piping hot.

Hygiene measures:

- Render water potable by either bringing it to a boil or treating it with chlorine or iodine preparations and filtering with a filter of 1μm or less;

- Wash hands before and after eating.

Case studies

Case 1: Adult patient with acute diarrhoea

A woman aged 39 years presents to her local pharmacy requesting loperamide and co-codamol.

Consultation

The woman reports up to 10 episodes of watery diarrhoea in the past 24 hours. There are no obvious signs of blood or mucus in her stool. She has no appetite, is thirsty and has occasional cramping but no other pain . She has two children at the local school and works as a community carer for older people. She needs to go back to work owing to staff shortages.

Assessment

Viral or bacterial infection is the most likely cause with some signs of dehydration, thirst and dizziness. Cramping mainly on emptying her bowels and no pain making a flare of chronic diarrhoea less likely. No possible underlying causes identified, such as any recent surgery, faecal incontinence or overflow diarrhoea resulting from constipation. She is not immunocompromised and has no history of chronic bowel disease. The patient is exhibiting no red flag symptoms, therefore referral to her GP is not required.

Recommend ORS as the mainstay of management and explain that acute diarrhoea usually resolves within five to seven days [15] . An antidiarrhoeal should be used with caution as acute diarrhoea is a defence mechanism and there is a risk of toxic megacolon. Antibiotics are not indicated without microbiological tests. Advise her to drink water and isotonic sports drinks (e.g. Lucozade) to provide potassium but to avoid hypertonic sugary or fizzy drinks, fruit juices and milk, which can worsen symptoms owing to damage to the intestinal lining caused by infecting organisms [13,24,25] . Recommend the consumption of easily digestible foods with high water content, such as soup or broth containing sodium. Provide infection prevention and control advice. Return to work should be delayed until 48 hours after symptoms resolve, and if symptoms do not improve or resolve within seven days of onset, she should visit her GP for further investigation of the cause [13] .

Case 2: Paediatric patient

A woman comes into the pharmacy on a Saturday afternoon asking for advice on diarrhoea management for her son who is six months old. The mother states she has kept him home from nursery as he hasn’t quite been himself and is a bit clingier than usual. He is requesting breast feeds more frequently and urine in his nappy is dark yellow in colour.

The mother says the baby has had watery diarrhoea for around 36 hours. He has no other medical conditions, is not receiving medication and she has not taken any actions so far. The baby has not vomited and has no fever, but looks quite pale with cold hands and has a slightly sunken fontanelle.

The child is already at a high risk of dehydration owing to his age and is displaying signs of clinical dehydration, such as dark urine, pallor, cold hands and a sunken fontanelle. Other red flag symptoms, such as the duration of diarrhoea, warrant referral [5] .

Advice

The mother should be signposted to the local out-of-hours GP or hospital emergency department for assessment, but she should be supplied with and advised on the use of ORS so that treatment can commence immediately in case of clinical delay.

Reassure her that diarrhoea is usually self-limiting and manageable at home with ORS and can last five to seven days, but that it should stop within two weeks [5] . Provide infection prevention and control advice, delay return to nursery until 48 hours after symptoms resolve and advise to keep away from swimming pools for two weeks. Advise not to make formula weaker or give fruit juice as it can make diarrhoea worse [13] .

Case 3: Travellers’ diarrhoea

A 25-year-old male patient presents at the pharmacy with complaints of diarrhoea (approximately 5 times per day), abdominal pain and nausea for the past 3 to 4 days. He also complains of dry mouth, abdominal cramping and overall malaise. He states that he recently travelled to India on an adventure trip and has returned the day before.

The patient did not receive any vaccinations or medications prior to travel and has not received antibiotics in the past five years. He reports no blood in the stool. He was on the return journey when the symptoms started so has not sought any professional advice.

Travellers’ diarrhoea is, for most people, a short-lived, self-limiting illness with recovery in a few days [6]. If the patient complains of blood in the stool and intermittent fevers and dehydration, he should seek medical advice as soon as possible [9] .

ORS is the treatment of choice for mild travellers’ diarrhoea [9] . As a rough guide, advise to drink at least 200ml after each watery stool. This extra fluid should be taken in addition to what the patient would normally drink [9] . If the patient is vomiting, advise to wait five to ten minutes and then start drinking again but more slowly. Advise them to take a sip every two to three minutes but make sure that the total intake is as described above [26,27] .

It used to be advised to avoid eating for a while; however, it is now advised to eat small, light meals if possible, such as plain bread or rice. Continue with fluids and avoid fatty, spicy or ‘heavy’ food [9] .

Loperamide or bismuth preparations can be considered for short-term treatment (two days). Advise the person not to use loperamide or bismuth subsalicylate if they have blood or mucus in the stool and/or high fever or severe abdominal pain, but seek medical advice [9] .

This article was amended on 1 September 2021 to clarify that the codeine dose is every four hours, not up to 4 per hour, and the maximum daily dose of loperamide is 12mg when supplied over the counter and 16mg when prescribed.

Useful resources

- NHS: Diarrhoea and/or vomiting advice sheet (gastroenteritis) — advice for parents and carers of children

- National Travel Health Network and Centre (NATHAC) : Travel health information aimed at healthcare professionals advising travellers and people travelling overseas from the UK

- NHS: Diarrhoea and vomiting

- www.patient.info: Travellers’ diarrhoea patient information

- www.patient.info: Gastroenteritis in children patient information

- www.patient.info: Food poisoning in children patient information

- Medicines for Children: Oral rehydration salts patient information leaflet

- 1 Diarrhoeal disease fact sheet. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diarrhoeal-disease (accessed Jul 2021).

- 2 Sandmann FG, Jit M, Robotham JV, et al. Burden, duration and costs of hospital bed closures due to acute gastroenteritis in England per winter, 2010/11–2015/16. Journal of Hospital Infection 2017; 97 :79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2017.05.015

- 3 Managing Suspected Infectious Diarrhoea: Quick Reference Guide for Primary Care. Public Health England. 2015. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/409768/Managing_Suspected_Infectious_Diarrhoea_7_CMCN29_01_15_KB_FINAL.pdf (accessed Jul 2021).

- 4 Arasaradnam RP, Brown S, Forbes A, et al. Guidelines for the investigation of chronic diarrhoea in adults: British Society of Gastroenterology, 3rd edition. Gut 2018; 67 :1380–99. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315909

- 5 Diarrhoea and vomiting caused by gastroenteritis diagnosis, assessment and management in children younger than 5 years. NICE clinical guideline [CG84]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2009. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg84/resources/full-guideline-pdf-243546877 (accessed Jul 2021).

- 6 Spiller R, Aziz Q, Creed F, et al. Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management. Gut 2007; 56 :1770–98. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.119446

- 7 Diarrhoea – adult’s assessment. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2018. https://cks.nice.org.uk/diarrhoea-adults-assessment#!topicSummary (accessed Jul 2021).

- 8 Oral rehydration salts. Information for parents and carers leaflet. Medicines for Children. https://www.medicinesforchildren.org.uk/oral-rehydration-salts (accessed Jul 2021).

- 9 Diarrhoea prevention advice for travellers. Clinical Knowledge Summary. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/diarrhoea-prevention-advice-for-travellers/background-information/causes (accessed Jul 2021).

- 10 Food poisoning. NHS Inform. https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/infections-and-poisoning/food-poisoning (accessed Jul 2021).

- 11 BAM Chapter 14: Bacillus cereus. US Food & Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/food/laboratory-methods-food/bam-chapter-14-bacillus-cereus (accessed Jul 2021).

- 12 Shane AL, Mody RK, Crump JA, et al. 2017 Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Infectious Diarrhea. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017; 65 :e45–80. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix669

- 13 UK conditions: Diarrhoea and vomiting. NHS. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/diarrhoea-and-vomiting (accessed Jul 2021).

- 14 Dehydration. NHS. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/dehydration (accessed Jul 2021).

- 15 Gastroenteritis. NICE clinical knowledge summary. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019. https://cks.nice.org.uk/gastroenteritis#!topicSummary (accessed Jul 2021).

- 16 Owen S. Can high dose loperamide be used to reduce stoma output? . Specialist Pharmacy Service. 2019. https://www.sps.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/UKMI_QA_Highdoseloperamide_updateSep-2018_FINAL_partial-update-Mar2019.pdf (accessed Jul 2021).

- 17 Loperamide (Imodium): reports of serious cardiac adverse reactions with high doses of loperamide associated with abuse or misuse. Gov.uk. 2017. https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/loperamide-imodium-reports-of-serious-cardiac-adverse-reactions-with-high-doses-of-loperamide-associated-with-abuse-or-misuse (accessed Jul 2021).

- 18 Codeine phosphate 15mg tablets BP. Summary of product characteristics. Aurobindo Pharma – Milpharm Ltd. . medicines.org. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/11268 (accessed Jul 2021).

- 19 Pharmaceutical considerations for patients with stomas. Pharmaceutical Journal Published Online First: 2020. doi: 10.1211/pj.2020.20208146

- 20 Co-phenotrope drug monograph. British National Formulary. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/co-phenotrope.html (accessed Jul 2021).

- 21 SMC advice racecadotril 10mg, 30mg granules for oral suspension (Hidrasec Infants®, Hidrasec Children®)SMC No.(818/12). Scottish Medicines Consortium. 2014. https://www.scottishmedicines.org.uk/medicines-advice/racecadotril-hidrasec-resubmission-81812 (accessed Jul 2021).

- 22 Diarrhoea (acute) treatment summary. British National Formulary. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summary/diarrhoea-acute.html (accessed Jul 2021).

- 23 Cipla EU L. Loperamide 2mg Capsules. Summary of product characteristics. medicines.org.uk. 2020. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/10287/smpc (accessed Sep 2021).

- 24 Knott L. Gastroenteritis. Patient. 2017. https://patient.info/digestive-health/diarrhoea/gastroenteritis (accessed Jul 2021).

- 25 Lactose intolerance Causes. NHS. 2019. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/lactose-intolerance/causes (accessed Jul 2021).

- 26 Hill DR, Ryan ET. Management of travellers’ diarrhoea. BMJ 2008; 337 :a1746–a1746. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1746

- 27 Traveller’s diarrhoea. Patient. https://patient.info/travel-and-vaccinations/travellers-diarrhoea-leaflet (accessed Jul 2021).

Please leave a comment Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You might also be interested in…

Inflammatory bowel disease: treatment and management

Inflammatory bowel disease: symptoms and diagnosis

Case-based learning: gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in adults

- Register-org

- Subscriptions

Recent Posts

- Balancing Work and Wellness: Health Management Tips for Busy Women

- Transform Your Health: A Beginner’s Guide To Effective Exercise

- Lichen Planopilaris: Confronting The Inflammatory Battle Against Hair Loss

- Stressed Out? Watch Your Veins!

- Office Live, Healthy Veins: Quick Tips

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.org

- Allergy and Immunology

- Anesthesiology

- Basic Science

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Cardiovascular

- Complementary Medicine

- Critical Care Medicine

- Dermatology

- Emergency Medicine

- Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Hematology, Oncology and Palliative Medicine

- Internal Medicine

- Medical Education

- Neonatal – Perinatal Medicine

- Neurosurgery

- Nursing & Midwifery & Medical Assistant

- Obstetrics & Gynecology

- Opthalmology

- Orthopaedics

- Otolaryngology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Plastic Reconstructive Surgery

- Pulmolory and Respiratory

- Rheumatology

Search Engine

Diarrhea (Case 24)

Published on 24/06/2015 by admin

Filed under Internal Medicine

Last modified 24/06/2015

This article have been viewed 2662 times

David Rudolph DO and James Thornton MD

Case: A 22-year-old man was referred to gastroenterology with intractable bloody diarrhea. His past medical history was unremarkable until last month, when he first noted the development of crampy abdominal pain, multiple daily bloody, mucus-filled stools, rectal urgency, and tenesmus. He also reported progressive fatigue, intermittent light-headedness, diminished appetite, and a subsequent 7-lb weight loss since symptom onset. He initially didn’t seek medical attention, because he thought the symptoms would just go away and, frankly, “just didn’t want to describe it to anyone.” He denied any recent travel, antibiotic use, close sick contacts, or high-risk sexual behaviors. On physical examination, he was somewhat ill-appearing with conjunctival pallor. Left lower quadrant abdominal tenderness was elicited with deep palpation, but no rebound or guarding was detected. The remainder of his physical examination was unremarkable.

Differential Diagnosis

Speaking Intelligently

When we encounter a patient with diarrhea, our investigation always begins with a thorough history and physical examination. The differential diagnosis for diarrhea is extremely broad, but by asking appropriate questions we can usually narrow the differential considerably. In addition, a complete physical examination helps differentiate which patients are currently stable and which patients are in need of more urgent medical attention. Volume depletion, a common sequela of secretory diarrhea, will be manifested by dry mucous membranes, poor skin turgor, and, if severe, tachycardia and hypotension. Anemia, a potential consequence of inflammatory diarrhea, should be suspected in the patient with diffuse pallor, fatigue, light-headedness, and exertional dyspnea.

PATIENT CARE

Clinical thinking.

• Determine the duration of the diarrhea. Acute diarrhea is typically defined as lasting ≤14 days and is often due to infections with viruses or bacteria. Chronic diarrhea is a decrease in fecal consistency and an increase in frequency lasting for 4 or more weeks and has a much broader differential diagnosis.

• Patients with sudden onset of watery diarrhea who provide a history of recent travel, close sick contacts, or ingestion of suspicious foods can be presumed to have acute infectious diarrhea, which is usually self-limited and often (in the absence of clinical volume depletion) requires no further workup or treatment.

• Pus or blood in the stools should alert the clinician to an invasive infectious or inflammatory etiology, which necessitates further workup. In this instance, initial evaluation should include checking stools for routine culture, leukocytes, and occult blood and, in the appropriate clinical setting, performing a Clostridium difficile assay and examination for ova and parasites.

• Oily, foul-smelling stools that float are suggestive of steatorrhea. Workup for disorders of malabsorption or maldigestion should be undertaken in patients who present with steatorrhea.

• Patients with clinical evidence of volume depletion and/or symptomatic anemia should be admitted to the hospital for IV fluid resuscitation and/or transfusion of packed RBCs.

• Factitious diarrhea, often secondary to surreptitious laxative use, should be considered in patients with chronic diarrhea with no identifiable etiology after extensive workup.

• A detailed history should include the duration of the diarrhea, the frequency and volume of stools, as well as associated symptoms (abdominal pain, vomiting, fever, myalgias, arthralgias, rash, diminished appetite, weight loss).

• Ask patients about any recent travel history, close sick contacts, day care exposures, or ingestion of undercooked foods. Recent antibiotic use is suggestive of C. difficile infection.

• Diarrhea that awakens a patient from sleep is worrisome for a pathologic etiology. Patients with IBS are much less likely to report a history of nocturnal symptoms.

• The presence of blood or mucus in stools suggests an inflammatory or invasive infectious etiology. Large-volume watery stools are consistent with secretory diarrhea. Oily, foul-smelling stools that float are suggestive of fat malabsorption or maldigestion.

• Ask patients about a family history of IBD, lactose intolerance, celiac disease, or other malabsorption syndromes.

• Inquire about any other significant medical history. Disordered motility can result from uncontrolled hyperthyroidism or long-standing diabetes mellitus.

• Review current prescribed and over-the-counter medications. Diarrhea can be precipitated by a multitude of commonly used medications including selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors, colchicine, metoclopramide, antibiotics, laxatives, magnesium-containing antacids, NSAIDs, antiarrhythmics, and antihypertensive agents.

• Review surgical history. Short-bowel syndrome can result in patients who have undergone previous bowel resections. Bile salt diarrhea can occur in patients who have undergone ileal resection.

Physical Examination

• Dry mucous membranes, sunken eyes, poor skin turgor, tachycardia, and orthostatic hypotension are signs concerning for volume depletion. Pallor is suggestive of anemia.

• Oral aphthous ulcers or episcleritis may be seen in patients with IBD.

• Close attention should be paid to the dermatologic examination. Erythema nodosum or pyoderma gangrenosum suggests underlying IBD. Dermatitis herpetiformis is suggestive of celiac disease.

• Abdominal examination should include inspection for surgical scars, palpation to assess for tenderness, masses, and/or hepatosplenomegaly, and auscultation for bowel sounds and abdominal bruits.

• Perianal fissures, fistulas, or abscesses provide support for a diagnosis of Crohn disease.

• Visible blood or pus on digital rectal examination (DRE) suggests an inflammatory or invasive infectious etiology.

• Palpable mass on DRE should raise suspicion for rectal neoplasm or fecal impaction.

• Fecal incontinence should be excluded with evaluation of anal sphincter tone to assess sphincter competence.

• Thyromegaly, exophthalmos, fine resting tremor, and hyperactive reflexes suggest uncontrolled hyperthyroidism.

Tests for Consideration

Share this:.

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Related posts:

Medicine A Competency-Based Companion With STUDENT CONSULT Onlin

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Case Study on Acute Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis, sometimes referred to as “stomach flu”, is an inflammation of the GI (gastrointestinal) tract, which includes the stomach and intestines. Most cases of gastroenteritis are caused by viruses. Bacterial gastroenteritis (caused by bacteria) often causes severe symptoms. It can even be fatal. It is also the most common digestive disorder among children. Severe gastroenteritis causes dehydration and an imbalance of blood chemicals (electrolytes) because of a loss of body fluids in the vomit and stool. This can be acquired through contaminated food and water that contains harmful bacteria (such as salmonella, Campylobacter, and E. coli). Food can be contaminated when food handlers don’t wash their hands. Or when food isn’t stored, handled, or cooked correctly. This can also be acquired and spread through the fecal-oral route, people with gastroenteritis have harmful bacteria in their stool. When they don’t wash their hands well after using the bathroom, they can spread the germs to objects. If you touch the same objects, you can pick up the germs on your hands and transfer them to your mouth. (Fairview.org, 2021)

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

23: Traveler’s Diarrhea

Amber B. Giles

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Patient presentation.

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Chief Complaint

“I can’t stop going to the bathroom, and I’m starting to get dehydrated.”

History of Present Illness

JB is a 32-year-old Caucasian male who presents to his primary care physician with complaints of bloody diarrhea approximately 5 times per day, abdominal pain, and nausea for the past 4 days. He also complains of intermittent fevers and dry mouth. He states that he recently traveled to India on a medical mission trip with other students in his medical school program. Of note, JB did not receive any vaccinations or medications prior to travel and has not received antibiotics in the past 5 years. He is up-to-date on all routine childhood vaccines.

Past Medical History

Seasonal allergies, depression, anxiety

Surgical History

Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy in primary school

Family History

Father has hyperlipidemia and type 2 diabetes; mother has no significant medical history

Social History

Student in his third year of medical school, married, lives with wife, and drinks alcohol occasionally. Reports no illicit drug or tobacco use

Ciprofloxacin (hives/shortness of breath)

Home Medications

Cetirizine 10 mg PO daily

Sertraline 100 mg PO daily

Physical Examination

Vital signs.

Temp 102.3°F, P 89, RR 24 breaths per minute, BP 110/69 mm Hg, pO 2 94%, Ht 6′2″, Wt 89 kg

Male with dizziness and in mild distress

Normocephalic, PERRLA, EOMI, dry mucous membranes and conjunctiva, fair dentition

Normal breath sounds

Cardiovascular

NSR, no m/r/g

Slightly distended, positive for abdominal pain, bowel sounds hyperactive

Genitourinary

Normal male genitalia, no complaints of dysuria or hematuria

Oriented to place and person

Extremities

Negative for pain or rash

Negative for back pain

Laboratory Findings

Sign in or create a free Access profile below to access even more exclusive content.

With an Access profile, you can save and manage favorites from your personal dashboard, complete case quizzes, review Q&A, and take these feature on the go with our Access app.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

- Advanced Life Support

- Endocrinology

- Gastroenterology

- Infectious disease

- Intensive care

- Palliative Care

- Respiratory

- Rheumatology

- Haematology

- Endocrine surgery

- General surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Ophthalmology

- Plastic surgery

- Vascular surgery

- Abdo examination

- Cardio examination

- Neurolo examination

- Resp examination

- Rheum examination

- Vasc exacmination

- Other examinations

- Clinical Cases

- Communication skills

- Prescribing

Diarrhoea case study with questions and answers

Diarrhoea example case study: How to investigate and treat diarrhoea

This page is currently being written and will be available soon. To be updated when it is complete please like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter or subscribe on YouTube using the ‘follow us’ buttons.

Related page: constipation example case study with questions and answers

Click the tags below or use our search bar for other cases and detailed pages on managing diarrhoea.

Diarrhea Nursing Care Plan and Management

Use this nursing care plan and management guide to help care for patients with diagnosis of diarrhea . Learn about the nursing assessment , nursing interventions, goals and nursing diagnosis for diarrhea in this guide.

Table of Contents

What is diarrhea, signs and symptoms, goals and outcomes, nursing assessment and rationales, nursing interventions and rationales, recommended resources, references and sources.

Diarrhea is defined as an increase in the frequency of bowel movements and the water content and volume of the waste. It may arise from various factors, including malabsorption disorders, increased secretion of fluid by the intestinal mucosa, and hypermotility of the intestine. It may also be due to infection, inflammatory bowel diseases, side effects of drugs, increased osmotic loads, radiation, or increased intestinal motility.

Diarrhea can be an acute or severe problem. Mild diarrhea cases can recover in a few days. However, severe diarrhea can lead to dehydration or severe nutritional problems. Problems associated with diarrhea include fluid and electrolyte imbalances , impaired nutrition , and altered skin integrity . Additionally, nurses and the healthcare team members must take precautions to prevent transmission of infection associated with some causes of diarrhea.

The following are the common causes and factors related to the development of diarrhea:

- Alcohol abuse

- Chemotherapy

- Disagreeable dietary intake

- Enteric infections: viral, bacterial, or parasitic

- Gastrointestinal disorders

- Increased secretion

- Laxative abuse

- Malabsorption (e.g., lactase deficiency)

- Motor disorders: irritable bowel

- Mucosal inflammation: Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis

- Short bowel syndrome

- Side effects of medication use

- Surgical procedures: bowel resection, gastrectomy

- Tube feedings

A patient with diarrhea may report the following signs and symptoms:

- Abdominal pain

- Frequency of stools (more than 3/day)

- Hyperactive bowel sounds (borborygmi) or sensations

- Loose or liquid stools

The following are the common goals and expected outcomes for Diarrhea :

- Within 8 hours of nursing interventions, the patient verbalizes understanding of diarrhea’s causes and the rationale for treatment.

- Within 24 hours of nursing interventions, the patient will consume at least 1,500 to 2,000 mL of clear liquids to maintain good skin turgor and normal weight.

- Within 24 hours of nursing interventions, the patient re-establishes and maintains a normal pattern of bowel functioning.

A thorough assessment is important to ascertain potential problems that may have led to diarrhea and handle any conflict that may appear during nursing care.

1. Assess for abdominal discomfort, pain, cramping, frequency, urgency, loose or liquid stools, and hyperactive bowel sensations. These assessment findings are usually linked with diarrhea. Patients differ in their definition of diarrhea, noting loose stool consistency, increased frequency, the urgency of bowel movements, or incontinence as key symptoms. Normal stool frequency ranges from three times a week to three times a day. Physicians have used increased frequency of defecation or increased stool weight as major criteria and distinguish acute diarrhea (Schiller et al., 2016). Many patients with acute diarrhea, regardless of cause, experience gas, cramps, bloating, distention, flatulence, nausea , vomiting, and abdominal pain. Abdominal pain or “stomachache” can be felt between the chest and pelvis. It can be cramp-like, achy, dull, or sharp. Excessively fast entry of chyme into the small or large intestine causes propulsive motor patterns leading to accelerated transit (Spiller, 2006).

2. Evaluate the pattern of defecation. Everyone’s bowels are unique to them. What’s normal for one person may not be normal for another. A person can have a bowel movement anywhere from one to three times a day at the most, or three times a week at the least, and still be considered regular, as long as it’s their usual pattern. Assessment of defecation pattern will help direct treatment.

3. Culture stool. Testing or stool examinations will distinguish infectious or parasitic organisms, bacterial toxins, blood , fat, electrolytes , white blood cells, and potential etiological organisms for diarrhea.

4. Determine tolerance to milk and other dairy products. Diarrhea is a typical indication of lactose intolerance. Patients with lactose intolerance have insufficient lactase, the enzyme that digests lactose. The presence of lactose in the intestines increases osmotic pressure and draws water into the intestinal lumen. The capacity of lactose malabsorption can be measured using the noninvasive lactose breath hydrogen test (Jankowiak & Ludwig, 2008).

5. Determine intolerances to food. If a person has a food intolerance, eating that food can cause diarrhea or loose stool. Foods may trigger intestinal nerve fibers and cause increased peristalsis. Some foods can increase intestinal osmotic pressure and draw fluid into the intestinal lumen. Spicy, fatty, or high-carbohydrate foods; caffeine; sugar-free foods with sorbitol; or contaminated tube feedings may cause diarrhea. Keeping a food and symptom diary can help determine a pattern. Food intolerance is different from a food allergy . Food allergies can likewise cause diarrhea, along with hives, itchy skin, congestion , and throat tightening.

6. Determine methods of food preparation. Diarrhea may also be due to inadequately cooked food, food contaminated with bacteria during preparation, foods not maintained at appropriate temperatures, or contaminated tube feedings. Based on a study in children and improving mothers’ knowledge, attitude, and practices regarding safe feeding practices, there was a 52% reduction in the incidence of diarrhea after food safety education intervention (Sheth & Obrah, 2004).

7. Review the medications the patient is or has been taking. Diarrhea can be caused by certain medications such as thyroid hormone replacement, stool softeners, laxatives, prokinetic agents, antibiotics , chemotherapy, antiarrhythmics , antihypertensives , magnesium -based antacids. Antibiotics are a common cause of hospital-acquired diarrheas in about 20% of patients receiving broad-spectrum antibiotics (Semrad, 2012).

8. Assess changes in eating habits and behaviors. Good health habits, good eating habits, and regular exercise can prevent episodes of diarrhea and thus decrease the potential for disease occurrence (Ma et al., 2014). Alterations in eating habits can cause intestinal function changes and lead to diarrhea. These may include:

- Eating too quickly. It takes less than 30 minutes for the stomach to tell the brain it’s full, therefore, eating too quickly means that the person is most likely to overeat and have more to digest.

- Gulping down food. When the person gulps, the person also swallows air, which can lead to trapped wind and poor digestion.

- Eating big, heavy meals. These take longer to digest and make the system work harder.

- Eating late at night. The digestive system is at its least efficient at the end of the day.

9. Review osmolality of tube feedings. Hyperosmolar food or fluid draws excess fluid into the gut, stimulates peristalsis, and causes diarrhea. Other factors associated with enteral nutrition that may contribute to diarrhea include the composition of the formula, the manner of administration, or bacterial contamination. All possible causes of diarrhea should be considered first before discontinuing or reducing the amount of formula delivered. Such conditions as diabetes often cause diarrhea in patients who receive enteral nutrition, malabsorption syndromes, infection, gastrointestinal complications, or concomitant drug therapy other than enteral formula (Chang & Huang, 2013)

10. Assess stress levels. Certain individuals respond to stress with hyperactivity of the gastrointestinal tract. In response to stress, a psychological reaction happens (Fight-or-Flight Response). This response triggers the release of hormones that conveys the body ready to take action. Along with this, the brain sends a signal to the bowels to increase bowel movement in the large intestine. This leads to a mild case of diarrhea.

11. Assess for fecal impaction. Liquid stool (apparent diarrhea) may seep past fecal impaction. While this stool may be too large to pass, loose, watery stool may be able to get by, leading to diarrhea, leakage, or exploding of fecal material.

12. Determine hydration status by assessing input and output . Diarrhea can lead to profound dehydration. A prolonged episode of diarrhea or vomiting can push the body to lose more fluid than it can take in. The result is dehydration, which happens when the body doesn’t have the fluid it requires to function correctly.

13. Assess moisture of mucous membranes. Dehydration causes dry mucous membranes. The nurse should also watch for dry mouth and tongue, no tears when crying, listlessness or crankiness, sunken cheeks or eyes, sunken fontanel (the soft spot on the top of a baby’s head), fever , and skin that does not return to normal when pinched and released.

14. Assess skin turgor. A decrease in skin turgor is exhibited when the skin (on the back of the hand for an adult or the abdomen for a child) is pinched and released but does not flatten back to normal right away. Decreased skin turgor and tenting of the skin occur in dehydration.

15. Assess for other signs of dehydration. Signs of dehydration include thirst, urinating less frequently than normal, dark-colored urine , dry mouth and tongue, feeling tired, sunken eyes or cheeks, lightheadedness or fainting, and a decreased skin turgor. Additional signs in children include a lack of energy, no wet diapers for three hours, listlessness or irritability, and the absence of tears while crying.

16. Assess history for gastrointestinal diseases. Diseases such as gastroenteritis and Crohn’s disease can result in malabsorption and chronic diarrhea. Watery stools are characteristic of disorders of the small bowel, while loose, semisolid stools are linked more frequently with disorders of the large bowel. Voluminous, greasy stools indicate intestinal malabsorption, and the presence of blood, mucus, and pus in the stools indicates inflammatory enteritis or colitis. Oil droplets on the toilet water are constantly diagnostic of pancreatic insufficiency. Nocturnal diarrhea may be a manifestation of diabetic neuropathy.

17. Assess history for abdominal radiation therapy. Radiation causes sloughing of the intestinal mucosa, decreased absorption capacity, and diarrhea. Exudative diarrhea is caused by changes in mucosal integrity, epithelial loss, or tissue destruction by radiation or chemotherapy (Sabol & Carlson, 2007).

18. Use the Common Toxicity Criteria (CTC) to grade chemotherapy-related diarrhea. CTC guidelines are used in many countries like the U.S. and U.K. in grading and treating chemotherapy-related diarrhea.

- Grade 0: None

- Grade 1: An increase of fewer than four stools per day over pretreatment

- Grade 2: An increase of 4 to 6 stools per day, or nocturnal stools

- Grade 3: An increase of 7 or more stools per day or incontinence; or need for parenteral support for dehydration

- Grade 4: physiologic consequences requiring intensive care; or hemodynamic collapse

- Grade 1: mild increase in loose, watery colostomy output compared with pretreatment

- Grade 2: moderate increase in loose, watery colostomy output compared with pretreatment, but not interfering with normal activity

- Grade 3: severe increase in loose, watery colostomy output compared with pretreatment, interfering with normal activity

- Grade 4: physiologic consequences, requiring intensive care; or hemodynamic collapse

19. Assess history for previous gastrointestinal surgery . Diarrhea is normal 1 to 3 weeks after bowel resection. Patients with gastric partitioning surgery for weight loss may experience diarrhea as they begin refeeding. Diarrhea is a manifestation of dumping syndrome in which an increased osmotic bolus entering the small intestine draws fluid into the small intestine.

20. Assess history of foreign travel, ingestion of unpasteurized dairy products, or drinking untreated water. Patients may acquire intestinal infections from eating contaminated foods or drinking contaminated water. North American travelers to developing countries and travelers on airplanes and cruise ships are at high risk for acute infectious diarrhea. Most travelers’ diarrhea (85%) is due to enterotoxin E. coli (Semrad, 2012).

21. Determine the type of stools using the Bristol Stool Chart. The Bristol Stool Chart or Bristol Stool Scale is a medical aid designed to classify stools into seven groups. Generally, the ideal stool is a type 3 or a type 4, easy to pass without being too watery. If the patient is type 1 or 2, the patient is probably constipated. If the patient falls under types 5, 6, and 7, the patient tends toward diarrhea.

- Type 1: Separate hard lumps, like nuts (hard to pass)

- Type 2: Sausage-shaped but lumpy

- Type 3: Like a sausage but with cracks on its surface

- Type 4: Like a sausage or snake, smooth and soft

- Type 5: Soft blobs with clear-cut edges (passed easily)

- Type 6: Fluffy pieces with ragged edges, a mushy stool

- Type 7: Watery, no solid pieces (entirely liquid)

22. Assess the condition of the perianal skin. Diarrheal stools may be highly corrosive as a result of increased enzyme content. Frequent loose and acidic stools can cause perianal skin breakdown, specifically in young children.

23. Examine the emotional impact of illness, hospitalization, and soiling accidents. Loss of control of bowel elimination that occurs with diarrhea can lead to feelings of embarrassment and decreased self-esteem . People who felt they were unable to foresee and manage their diarrhea experienced significant fear and worry associated with the chance of becoming incontinent in public and being humiliated. Most felt their diarrhea controlled them in that it often dictated what they could and could not do socially or when they could leave the house, and as a result, it greatly impacted their mood (Siegel et al., 2010).

The following are the therapeutic nursing interventions for diarrhea:

1. Weigh daily and note decreased weight. Diarrhea causes severe water loss from the body. As a result, the body loses weight. An accurate daily weight is an important indicator of fluid balance in the body. It has consistently been associated with decreased weight over the short term, but the longer-term impact of diarrhea on weight has been less consistently documented and is more controversial (Richard et al., 2013).

2. Have the patient keep a diary of their bowel movements. Stool consistency needs to be evaluated, which may be accomplished by the patient keeping a self-care log or diary. Evaluation of defecation pattern will help direct treatment, especially for cancer -related diarrhea. Diary log should include the time of day defecation occurs; a usual stimulus for defecation; consistency, amount, and frequency of stool; type of, amount of, and time food consumed; fluid intake; history of bowel habits and laxative use; diet; exercise patterns; obstetrical/gynecological, medical, and surgical histories; medications; alterations in perianal sensations; and present bowel regimen (O’Brien et al., 2005).

3. Avoid using medications that slow peristalsis. If an infectious process occurs , such as Clostridium difficile infection or food poisoning , medication to slow down peristalsis should generally not be given. Over the years, several case reports have described adverse events, such as toxic megacolon, exacerbation of colitis, and systemic infection, associated with the use of antimotility agents for CDI. The increase in gut motility helps eliminate the causative factor, and the use of antidiarrheal medication could result in toxic megacolon. Note that antidiarrheals are agents that may exacerbate toxic megacolon, such as opioids, antidepressants , nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, and anticholinergics (Koo et al., 2009).

4. Give antidiarrheal drugs as ordered. Most antidiarrheal drugs suppress gastrointestinal motility, thus allowing for more fluid absorption. Supplements of beneficial bacteria (“probiotics”) or yogurt may reduce symptoms by reestablishing normal flora in the intestine. Antidiarrheal agents are of two types: those used for mild to moderate diarrheas and those used for severe secretory diarrheas. A major shortcoming of opiates, the most commonly prescribed antidiarrheal agents, is that they have no antisecretory effect. Instead, they function by decreasing intestinal motility, thereby allowing longer contact time with the mucosa for improved fluid absorption. In contrast, racecadotril, an enkephalinase inhibitor, blocks intestinal fluid secretion without affecting motility. Meanwhile, antidiarrheal agents used to treat severe secretory and inflammatory diarrheas typically have profiles with more serious side effects (Semrad, 2012).

5. Provide bulk fiber (e.g., cereal, grains, psyllium) in the diet. Bulking agents and dietary fibers absorb fluid from the stool and help thicken the stool. Psyllium is found in some cereal products, dietary supplements, and commercial bulk fiber laxatives (e.g., Metamucil, Konsyl, generic). According to the International Foundation for Gastrointestinal Disorders (IFFGD, 2022), one teaspoonful of psyllium twice daily is usually recommended for constipation . It is also used for diarrhea due to its water-holding effect in the intestines that may aid in bulking up the watery stool. It can also bind some toxins that may cause acute diarrhea. Psyllium products combined with laxatives should be avoided. A study demonstrated that psyllium husk (Ispaghula) has a gut-stimulatory effect, mediated partially by muscarinic and 5-HT4 receptor activation, which may complement the laxative effect of its fiber content, and a gut-inhibitory activity possibly mediated by blockade of Ca2+ channels and activation of NO-cyclic guanosine monophosphate pathways. This may explain its medicinal use in diarrhea. It is, perhaps, also intended by nature to offset an excessive stimulant effect (Mehmood et al., 2010).

6. Provide “Natural” bulking agents (e.g., rice, apples, matzos, cheese) in the diet. Soluble fiber removes excess fluid, which is how it helps decrease diarrhea. Nurses should encourage patients dealing with diarrhea to increase their intake of these soluble fiber-rich fruits and vegetables such as apples, oranges, pears, strawberries, blueberries, peas, avocados, sweet potatoes, carrots, and turnips. There are two different types of fiber — soluble and insoluble fiber. Soluble fiber slows things down in the digestive tract, helping with diarrhea, while insoluble fiber can speed things up, alleviating constipation.

7. Explain the need to avoid stimulants (e.g., caffeine, carbonated beverages, artificial sweeteners) Caffeine may stimulate the intestines and increase motility. Aside from caffeine, some sugary sodas also contain high-fructose corn syrup, a combination of fructose and dextrose that may lead to fructose malabsorption. Symptoms include bloating and stomach pain, heartburn, diarrhea, and gas. Artificial sweeteners can have a laxative effect. They pull water into the colon and aid to mobilize the stool, which can cause the runs. Another reason soda may induce diarrhea is the carbonation that provides soda its fizz that can create belching, flatulence, and indigestion. The bloating and gas may cause a flare and lead to diarrhea.

8. Record the number and consistency of stools per day; if desired, use a fecal incontinence collector for accurate measurement of output. Documentation of output provides a baseline and helps direct replacement fluid therapy. The Fecal Collection System can also be used. It is a closed catheter system used in managing incontinence patients with liquid or semi-liquid stool. It can also be used for diverting feces from the burned area to diminish the risk of skin breakdown and prevent cross-infection by protecting patients’ wounds.

9. Evaluate dehydration by observing skin turgor over the sternum and inspecting for longitudinal furrows of the tongue. Watch for excessive thirst, fever, dizziness, lightheadedness, palpitations, excessive cramping, bloody stools, hypotension , and symptoms of shock. Severe diarrhea can cause deficient fluid volume with extreme weakness and cause death in the very young, the chronically ill, and the elderly . A study illustrated how the combination of malnutrition, acute diarrhea, and alcohol withdrawal could lead to potentially fatal consequences, such as shock (Zhao et al., 2021).

10. Encourage intake of fluids 1.5 to 2 L/24 hr plus 200 mL for each loose stool in adults unless contraindicated; consider nutritional support. It’s necessary to increase fluid intake, especially when experiencing diarrhea. Increased fluid intake and liquid meal replacements can replenish fluid loss.

11. Encourage to take oral rehydration solution. Drinking more water may not be enough for a patient with diarrhea. Aside from fluids, the patient is also losing important minerals and electrolytes that water can’t supply.

- Adult patients can use oral rehydration solutions or diluted juices, diluted sports drinks, clear broth, or decaffeinated tea. Sugary, carbonated, caffeinated, or alcoholic drinks can worsen diarrhea.

For children

- Six to 24 months 90 mL to 125 mL (3 oz to 4 oz) every hour.

- Over two years 125 mL to 250 mL (4 oz to 8 oz) every hour

- If the infant refuses ORS by the cup or bottle, give this solution using a medicine dropper, small teaspoon or frozen pops.

- If the child vomits, stop giving food and drink but continue to give ORS using a spoon. Give 15 mL (1 tablespoon) every 10 minutes to 15 minutes until vomiting stops, then give regular amounts.

- Keep giving the oral rehydration solution until diarrhea is less frequent. When vomiting decreases, it’s important to have the child drink the usual formula or whole milk and regular food in small frequent feedings. After 24 to 48 hours, most children can resume their normal diet. Stools may increase at first (one or two more each day). It may take seven to 10 days or longer for stools to become completely formed. This is part of healing the bowel.

12. Monitor and record intake and output; note oliguria and dark, concentrated urine. Measure the specific gravity of urine if possible. Dark, concentrated urine, along with a high specific gravity of urine, is an indication of deficient fluid volume . These measurements are important to help evaluate a person’s fluid and electrolyte balance, suggest various diagnoses, and prompt intervention to correct the imbalance. The nurse should record all intake and output meticulously in an Intake and Output Chart (I/O Chart). All amounts must be measured and recorded in milliliters. Do not estimate the amount. If the person can cooperate, they should be encouraged to help in keeping an accurate record of his daily fluid intake and output.

13. Evaluate the appropriateness of protocols for bowel preparation based on age, weight, condition, disease, and other therapies. Older, frail patients or those already depleted may require less bowel preparation or additional intravenous fluid therapy during preparation.

14. Provide perianal care after each bowel movement. Diarrhea can cause burning and inflammation around the anus. When cleaning, use a mild cleansing agent (perineal skin cleanser), apply a protective ointment or barrier creams, and if the skin is excoriated or desquamated, apply a wound hydrogel. These are a few things nurses can encourage, or the patients can do to treat or stop this from happening.

15. Avoid the use of rectal Foley catheters. Rectal tubes may be safely and effectively used to prevent soiling in critically ill patients with diarrhea. However, rectal Foley catheters can cause rectal necrosis, sphincter damage, or rupture. The nursing staff may not have the time to properly follow the necessary and very time-consuming steps of their care.

16. If diarrhea is associated with cancer or cancer treatment, once the infectious cause of diarrhea is ruled out, provide medications as ordered to stop diarrhea. Cancer treatment can make the patient more susceptible to various infections, which can cause diarrhea. Antibiotics used to treat some infections also can cause diarrhea. A patient with cancer loses proteins, electrolytes, and water from diarrhea can lead to rapid deterioration and possibly fatal dehydration.

17. For patients with enteral tube feeding, employ the following interventions:

- 17.1. Change feeding tube equipment according to institutional policy, but no less than every 24 hours. Contaminated equipment can result to diarrhea. Emphasize the importance of regular monitoring of feeding practices and procedures when providing enteral nutrients for patients.

- 17.2. Administer tube feeding at room temperature. Extremes of temperature can stimulate peristalsis.

- 17.3. Initiate tube feeding slowly. Starting a tube feeding at a slow infusion rate allows the gastrointestinal system to accommodate intake.

- The caloric density refers to the calories per unit of volume. Commercially available formulas range in caloric density from 0.5 to 2.0 kcal/mL. As the caloric density increases, gastric motility and gastric emptying time decrease.

- The osmolality (mOsm/kg of water) or ionic concentration of commercial formulas ranges from 280 to 1100 mOsm/kg. Formulas that are higher in osmolarity, 400 to 1100 mOsm/kg, are hypertonic but can also be initiated at full strength. Patients who receive hypertonic formulas should be observed for delayed gastric emptying, severe diarrhea, electrolyte depletion, and severe dehydration. Decreasing the rate of infusion or osmolarity of the feeding prevents hyperosmolar diarrhea.

- With nutrient density , a complication of high-fat/low-CHO formulas is a delay in gastric emptying. Delayed gastric emptying poses the risk of reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus or trachea , causing aspiration .

- A little or no residue content formulas are usually hypertonic with a caloric density that ranges from 1 to 2 kcal/mL. The low-residue enteral formulas contain soy or pectin fiber. Insoluble fiber, such as soy polysaccharides, increases fecal weight, thereby increasing peristalsis and decreasing fecal transit time.

- Formulas that are made from food processed in a blender contain lactose . When administered to patients with a known lactase deficiency, they should be given by continuous, not intermittent, or bolus infusion. A continuous infusion reduces the intolerance of lactose by the gastrointestinal tract.

18. If diarrhea is chronic and there is an indication of malnutrition, discuss with the primary care practitioner for a dietary consult and possible use of a hydrolyzed formula to maintain nutrition while the gastrointestinal system heals. The hydrolyzed formula is one type of hypoallergenic infant formula. It is designed for infants who have trouble digesting standard cow’s milk-based formulas and experience GI issues, reflux, colicky crying, and other symptoms when given these “regular” formulas. A hydrolyzed formula has protein partially broken down into small peptides or amino acids for people who cannot digest nutrients.

19. Encourage the patient to eat small, frequent meals and to consume foods that normally cause constipation and are easy to digest. Bland, starchy foods are initially recommended when starting to eat solid food again.

20. Educate patient not to eat only bland foods. BRAT diet of bananas, rice, applesauce, and toast is fine for the first day or so of stomach flu . However, advise patients to return to their normal diet as soon as they feel up to it. BRAT food does not provide the fat and protein needed, and prolonged use can slow the patient’s recovery.

21. Educate patient or caregiver about dietary measures to control diarrhea. These measures include avoiding spicy, fatty foods, alcohol, and caffeine; broiling, baking, or boiling foods instead of frying in oil; and avoiding disagreeable foods. Specific foods and diets are often incriminated as causes of diarrhea, some with good evidence and others less so. These dietary changes can slow the passage of stool through the colon and reduce or eliminate diarrhea. Remind the patient to avoid foods that may cause diarrhea. Examples include carbonated drinks, beverages, and dairy products.

22. Remind the patient of the importance of diet modification. Diet modification is an important part of self-management for patients with diarrhea. Advise patient to look for foods with potassium (such as potatoes, bananas, and fruit juices), salt (such as pretzels and soup), and yogurt with active bacterial cultures. Inform the patient even a little fat could help because it slows down digestion and may reduce diarrhea.

23. Allow patient to communicate with nurse or caregiver if diarrhea occurs with prescription drugs. Many diarrheas have more than one mechanism. One of the many causes of diarrhea is medications. Diarrhea triggered by prescription drugs should be reported immediately to prevent the worsening of diarrhea. More than 700 medications can cause diarrhea, including furosemide , caffeine, protease inhibitors, thyroid preparations, metformin , mycophenolate mofetil, sirolimus, cholinergic drugs, colchicine, theophylline, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, proton pump inhibitors, histamine-2 blockers, 5- ASA derivatives, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, bisacodyl, senna, aloe, anthraquinones, and magnesium- or phosphorus-containing medications. Antibiotics are a common cause of hospital-acquired diarrheas in about 20% of patients receiving broad-spectrum antibiotics (Semrad, 2012).

24. Educate patient or caregiver on the proper use of antidiarrheal medications as ordered. Antidiarrheal medications are found in most drug stores or pharmacies, or a physician can prescribe them. In taking antidiarrheal medications, discuss with the patient the proper use of each antidiarrheal medication to prevent worsening of the condition and prevent further dehydration. Appropriate use of antidiarrheal medications can promote effective bowel elimination.

25. Discuss the importance of fluid replacement during diarrheal episodes. Aside from antidiarrheal agents, nutritional support, and antimicrobial therapy, one of the primary treatments for diarrhea is fluid replacement. Severely dehydrated patients should be immediately managed and treated with intravenous Ringer’s lactate or saline solution , with additional potassium and bicarbonate as needed. Oral rehydration solutions are used extensively to replace diarrheal fluid and electrolyte losses. They are useful and effective because of their sodium , sugars, and, often, amino acid contents that use nutrient-dependent sodium uptake transporters. In alert patients with mild to moderate dehydration, oral rehydration is equally effective as intravenous hydration in repairing fluid and electrolyte losses. After rehydration has been accomplished, oral rehydration solutions are given at rates equaling stool loss plus insensible losses until diarrhea stops. Fluid intake is vital to prevent dehydration (Semrad, 2012).

26. Impart to the patient the importance of good perianal hygiene. Hygiene reduces the risk of perianal excoriation and promotes comfort. A condition known as Fournier’s gangrene was associated with neglected prolonged diarrhea, perianal excoriation resulting from diarrhea, and poor hygiene. Fournier’s gangrene is necrotizing fasciitis of the perineal region. It is progressive and life-threatening if not aggressively treated. It is seen more frequently in adults than children and is associated with immunosuppressant factors. Poor hygiene and improper treatment of diarrhea have also contributed to the pathology (Neogi et al., 2013).

27. Educate patient and significant other (SO) on preparing food properly and the importance of good food sanitation practices and handwashing . These could prevent outbreaks and spread infectious diseases transmitted through the fecal-oral route.

28. Provide tips on how to manage stress. Certain individuals respond to stress with hyperactivity of the gastrointestinal tract that leads to mild diarrhea. Discuss what might have triggered stress with the patient and plan ways to prevent them. Deep breathing is one of the best ways to lower stress in the body. When a person breathes deeply, it sends a message to the brain to calm down and relax.

29. Allow the patient to use free time to relax, meditate, read a book, or listen to music. Encourage patients to read books that have captured their interest and provide a space for the mind to relax every day. Another way to release stress is through the power of music. Music is effective for relaxation and stress management. A slower tempo can quiet the mind and relax the muscles, making the person feel soothed. Research confirms these personal experiences with music.

30. Provide emotional support for patients who have trouble controlling unpredictable episodes of diarrhea. Diarrhea can be a great source of embarrassment to the elderly and lead to social isolation and a feeling of powerlessness . Providing care and support to those in need brings great meaning and purpose to nursing professionals.

Recommended nursing diagnosis and nursing care plan books and resources.

Disclosure: Included below are affiliate links from Amazon at no additional cost from you. We may earn a small commission from your purchase. For more information, check out our privacy policy .

Ackley and Ladwig’s Nursing Diagnosis Handbook: An Evidence-Based Guide to Planning Care We love this book because of its evidence-based approach to nursing interventions. This care plan handbook uses an easy, three-step system to guide you through client assessment, nursing diagnosis, and care planning. Includes step-by-step instructions showing how to implement care and evaluate outcomes, and help you build skills in diagnostic reasoning and critical thinking.

Nursing Care Plans – Nursing Diagnosis & Intervention (10th Edition) Includes over two hundred care plans that reflect the most recent evidence-based guidelines. New to this edition are ICNP diagnoses, care plans on LGBTQ health issues, and on electrolytes and acid-base balance.

Nurse’s Pocket Guide: Diagnoses, Prioritized Interventions, and Rationales Quick-reference tool includes all you need to identify the correct diagnoses for efficient patient care planning. The sixteenth edition includes the most recent nursing diagnoses and interventions and an alphabetized listing of nursing diagnoses covering more than 400 disorders.

Nursing Diagnosis Manual: Planning, Individualizing, and Documenting Client Care Identify interventions to plan, individualize, and document care for more than 800 diseases and disorders. Only in the Nursing Diagnosis Manual will you find for each diagnosis subjectively and objectively – sample clinical applications, prioritized action/interventions with rationales – a documentation section, and much more!

All-in-One Nursing Care Planning Resource – E-Book: Medical-Surgical, Pediatric, Maternity, and Psychiatric-Mental Health Includes over 100 care plans for medical-surgical, maternity/OB, pediatrics, and psychiatric and mental health. Interprofessional “patient problems” focus familiarizes you with how to speak to patients.

Other recommended site resources for this nursing care plan:

- Nursing Care Plans (NCP): Ultimate Guide and Database MUST READ! Over 150+ nursing care plans for different diseases and conditions. Includes our easy-to-follow guide on how to create nursing care plans from scratch.

- Nursing Diagnosis Guide and List: All You Need to Know to Master Diagnosing Our comprehensive guide on how to create and write diagnostic labels. Includes detailed nursing care plan guides for common nursing diagnostic labels.

References and sources you can use to further your research for diarrhea.

- Chang, S. J., & Huang, H. H. (2013). Diarrhea in enterally fed patients: blame the diet?. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care, 16(5), 588-594.

- Dehydration and diarrhea. (2003). Paediatrics & Child Health, 8(7), 459–460.

- Eisenberg, P. (1993). Causes of diarrhea in tube-fed patients: a comprehensive approach to diagnosis and management. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 8(3), 119–123.

- Jankowiak, C., & Ludwig, D. (2008). Frequent causes of diarrhea: celiac disease and lactose intolerance. Medizinische Klinik (Munich, Germany: 1983), 103(6), 413-22.

- Koo, H. L., Koo, D. C., Musher, D. M., & DuPont, H. L. (2009). Antimotility agents for the treatment of Clostridium difficile diarrhea and colitis. Clinical infectious diseases, 48(5), 598-605.

- Ma, C., Wu, S., Yang, P., Li, H., Tang, S., & Wang, Q. (2014). Behavioral factors associated with diarrhea among adults over 18 years of age in Beijing, China . BMC public health, 14(1), 1-7.

- Mehmood, M.H.; Aziz, N.; Ghayur, M.N.; Gilani, A. (2011). Pharmacological Basis for the Medicinal Use of Psyllium Husk (Ispaghula) in Constipation and Diarrhea. Dig Dis Sci 56, 1460–1471

- Neogi, S., Kariholu, P. L., Chatterjee, D., Singh, B. K., & Kumar, R. (2013). Fournier’s gangrene in a pediatric patient after prolonged neglected diarrhea: A case report. IJCRI, 4(2), 135-137.

- O’Brien, Bridget E.; Kaklamani Virginia G.; Benson, Al B., III. (2005). The Assessment and Management of Cancer Treatment-Related Diarrhea. , 4(6), 375–381.

- Richard, S. A.; Black, R. E.; Gilman, R. H.; Guerrant, R. L.; Kang, G.; Lanata, C. F.; Molbak, K.; Rasmussen, Z. A.; Sack, R. B.; Valentiner-Branth, P.; Checkley, W. (2013). Diarrhea in Early Childhood: Short-term Association With Weight and Long-term Association With Length. American Journal of Epidemiology, 178(7), 1129–1138.

- Schiller, L. R., Pardi, D. S., & Sellin, J. H. (2017). Chronic diarrhea: diagnosis and management. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 15(2), 182-193.

- Schiller, Lawrence R.; Pardi, Darrell S.; Sellin, Joseph H. (2016). Chronic Diarrhea: Diagnosis and Management. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, (), S1542356516305018–.

- Semrad, C. E. (2012). Approach to the patient with diarrhea and malabsorption. Goldman’s cecil medicine, 895.