Illustration by James Round

How to plan a research project

Whether for a paper or a thesis, define your question, review the work of others – and leave yourself open to discovery.

by Brooke Harrington + BIO

is professor of sociology at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. Her research has won international awards both for scholarly quality and impact on public life. She has published dozens of articles and three books, most recently the bestseller Capital without Borders (2016), now translated into five languages.

Edited by Sam Haselby

Need to know

‘When curiosity turns to serious matters, it’s called research.’ – From Aphorisms (1880-1905) by Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach

Planning research projects is a time-honoured intellectual exercise: one that requires both creativity and sharp analytical skills. The purpose of this Guide is to make the process systematic and easy to understand. While there is a great deal of freedom and discovery involved – from the topics you choose, to the data and methods you apply – there are also some norms and constraints that obtain, no matter what your academic level or field of study. For those in high school through to doctoral students, and from art history to archaeology, research planning involves broadly similar steps, including: formulating a question, developing an argument or predictions based on previous research, then selecting the information needed to answer your question.

Some of this might sound self-evident but, as you’ll find, research requires a different way of approaching and using information than most of us are accustomed to in everyday life. That is why I include orienting yourself to knowledge-creation as an initial step in the process. This is a crucial and underappreciated phase in education, akin to making the transition from salaried employment to entrepreneurship: suddenly, you’re on your own, and that requires a new way of thinking about your work.

What follows is a distillation of what I’ve learned about this process over 27 years as a professional social scientist. It reflects the skills that my own professors imparted in the sociology doctoral programme at Harvard, as well as what I learned later on as a research supervisor for Ivy League PhD and MA students, and then as the author of award-winning scholarly books and articles. It can be adapted to the demands of both short projects (such as course term papers) and long ones, such as a thesis.

At its simplest, research planning involves the four distinct steps outlined below: orienting yourself to knowledge-creation; defining your research question; reviewing previous research on your question; and then choosing relevant data to formulate your own answers. Because the focus of this Guide is on planning a research project, as opposed to conducting a research project, this section won’t delve into the details of data-collection or analysis; those steps happen after you plan the project. In addition, the topic is vast: year-long doctoral courses are devoted to data and analysis. Instead, the fourth part of this section will outline some basic strategies you could use in planning a data-selection and analysis process appropriate to your research question.

Step 1: Orient yourself

Planning and conducting research requires you to make a transition, from thinking like a consumer of information to thinking like a producer of information. That sounds simple, but it’s actually a complex task. As a practical matter, this means putting aside the mindset of a student, which treats knowledge as something created by other people. As students, we are often passive receivers of knowledge: asked to do a specified set of readings, then graded on how well we reproduce what we’ve read.

Researchers, however, must take on an active role as knowledge producers . Doing research requires more of you than reading and absorbing what other people have written: you have to engage in a dialogue with it. That includes arguing with previous knowledge and perhaps trying to show that ideas we have accepted as given are actually wrong or incomplete. For example, rather than simply taking in the claims of an author you read, you’ll need to draw out the implications of those claims: if what the author is saying is true, what else does that suggest must be true? What predictions could you make based on the author’s claims?

In other words, rather than treating a reading as a source of truth – even if it comes from a revered source, such as Plato or Marie Curie – this orientation step asks you to treat the claims you read as provisional and subject to interrogation. That is one of the great pieces of wisdom that science and philosophy can teach us: that the biggest advances in human understanding have been made not by being correct about trivial things, but by being wrong in an interesting way . For example, Albert Einstein was wrong about quantum mechanics, but his arguments about it with his fellow physicist Niels Bohr have led to some of the biggest breakthroughs in science, even a century later.

Step 2: Define your research question

Students often give this step cursory attention, but experienced researchers know that formulating a good question is sometimes the most difficult part of the research planning process. That is because the precise language of the question frames the rest of the project. It’s therefore important to pose the question carefully, in a way that’s both possible to answer and likely to yield interesting results. Of course, you must choose a question that interests you, but that’s only the beginning of what’s likely to be an iterative process: most researchers come back to this step repeatedly, modifying their questions in light of previous research, resource limitations and other considerations.

Researchers face limits in terms of time and money. They, like everyone else, have to pose research questions that they can plausibly answer given the constraints they face. For example, it would be inadvisable to frame a project around the question ‘What are the roots of the Arab-Israeli conflict?’ if you have only a week to develop an answer and no background on that topic. That’s not to limit your imagination: you can come up with any question you’d like. But it typically does require some creativity to frame a question that you can answer well – that is, by investigating thoroughly and providing new insights – within the limits you face.

In addition to being interesting to you, and feasible within your resource constraints, the third and most important characteristic of a ‘good’ research topic is whether it allows you to create new knowledge. It might turn out that your question has already been asked and answered to your satisfaction: if so, you’ll find out in the next step of this process. On the other hand, you might come up with a research question that hasn’t been addressed previously. Before you get too excited about breaking uncharted ground, consider this: a lot of potentially researchable questions haven’t been studied for good reason ; they might have answers that are trivial or of very limited interest. This could include questions such as ‘Why does the area of a circle equal π r²?’ or ‘Did winter conditions affect Napoleon’s plans to invade Russia?’ Of course, you might be able to make the argument that a seemingly trivial question is actually vitally important, but you must be prepared to back that up with convincing evidence. The exercise in the ‘Learn More’ section below will help you think through some of these issues.

Finally, scholarly research questions must in some way lead to new and distinctive insights. For example, lots of people have studied gender roles in sports teams; what can you ask that hasn’t been asked before? Reinventing the wheel is the number-one no-no in this endeavour. That’s why the next step is so important: reviewing previous research on your topic. Depending on what you find in that step, you might need to revise your research question; iterating between your question and the existing literature is a normal process. But don’t worry: it doesn’t go on forever. In fact, the iterations taper off – and your research question stabilises – as you develop a firm grasp of the current state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 3: Review previous research

In academic research, from articles to books, it’s common to find a section called a ‘literature review’. The purpose of that section is to describe the state of the art in knowledge on the research question that a project has posed. It demonstrates that researchers have thoroughly and systematically reviewed the relevant findings of previous studies on their topic, and that they have something novel to contribute.

Your own research project should include something like this, even if it’s a high-school term paper. In the research planning process, you’ll want to list at least half a dozen bullet points stating the major findings on your topic by other people. In relation to those findings, you should be able to specify where your project could provide new and necessary insights. There are two basic rhetorical positions one can take in framing the novelty-plus-importance argument required of academic research:

- Position 1 requires you to build on or extend a set of existing ideas; that means saying something like: ‘Person A has argued that X is true about gender; this implies Y, which has not yet been tested. My project will test Y, and if I find evidence to support it, that will change the way we understand gender.’

- Position 2 is to argue that there is a gap in existing knowledge, either because previous research has reached conflicting conclusions or has failed to consider something important. For example, one could say that research on middle schoolers and gender has been limited by being conducted primarily in coeducational environments, and that findings might differ dramatically if research were conducted in more schools where the student body was all-male or all-female.

Your overall goal in this step of the process is to show that your research will be part of a larger conversation: that is, how your project flows from what’s already known, and how it advances, extends or challenges that existing body of knowledge. That will be the contribution of your project, and it constitutes the motivation for your research.

Two things are worth mentioning about your search for sources of relevant previous research. First, you needn’t look only at studies on your precise topic. For example, if you want to study gender-identity formation in schools, you shouldn’t restrict yourself to studies of schools; the empirical setting (schools) is secondary to the larger social process that interests you (how people form gender identity). That process occurs in many different settings, so cast a wide net. Second, be sure to use legitimate sources – meaning publications that have been through some sort of vetting process, whether that involves peer review (as with academic journal articles you might find via Google Scholar) or editorial review (as you’d find in well-known mass media publications, such as The Economist or The Washington Post ). What you’ll want to avoid is using unvetted sources such as personal blogs or Wikipedia. Why? Because anybody can write anything in those forums, and there is no way to know – unless you’re already an expert – if the claims you find there are accurate. Often, they’re not.

Step 4: Choose your data and methods

Whatever your research question is, eventually you’ll need to consider which data source and analytical strategy are most likely to provide the answers you’re seeking. One starting point is to consider whether your question would be best addressed by qualitative data (such as interviews, observations or historical records), quantitative data (such as surveys or census records) or some combination of both. Your ideas about data sources will, in turn, suggest options for analytical methods.

You might need to collect your own data, or you might find everything you need readily available in an existing dataset someone else has created. A great place to start is with a research librarian: university libraries always have them and, at public universities, those librarians can work with the public, including people who aren’t affiliated with the university. If you don’t happen to have a public university and its library close at hand, an ordinary public library can still be a good place to start: the librarians are often well versed in accessing data sources that might be relevant to your study, such as the census, or historical archives, or the Survey of Consumer Finances.

Because your task at this point is to plan research, rather than conduct it, the purpose of this step is not to commit you irrevocably to a course of action. Instead, your goal here is to think through a feasible approach to answering your research question. You’ll need to find out, for example, whether the data you want exist; if not, do you have a realistic chance of gathering the data yourself, or would it be better to modify your research question? In terms of analysis, would your strategy require you to apply statistical methods? If so, do you have those skills? If not, do you have time to learn them, or money to hire a research assistant to run the analysis for you?

Please be aware that qualitative methods in particular are not the casual undertaking they might appear to be. Many people make the mistake of thinking that only quantitative data and methods are scientific and systematic, while qualitative methods are just a fancy way of saying: ‘I talked to some people, read some old newspapers, and drew my own conclusions.’ Nothing could be further from the truth. In the final section of this guide, you’ll find some links to resources that will provide more insight on standards and procedures governing qualitative research, but suffice it to say: there are rules about what constitutes legitimate evidence and valid analytical procedure for qualitative data, just as there are for quantitative data.

Circle back and consider revising your initial plans

As you work through these four steps in planning your project, it’s perfectly normal to circle back and revise. Research planning is rarely a linear process. It’s also common for new and unexpected avenues to suggest themselves. As the sociologist Thorstein Veblen wrote in 1908 : ‘The outcome of any serious research can only be to make two questions grow where only one grew before.’ That’s as true of research planning as it is of a completed project. Try to enjoy the horizons that open up for you in this process, rather than becoming overwhelmed; the four steps, along with the two exercises that follow, will help you focus your plan and make it manageable.

Key points – How to plan a research project

- Planning a research project is essential no matter your academic level or field of study. There is no one ‘best’ way to design research, but there are certain guidelines that can be helpfully applied across disciplines.

- Orient yourself to knowledge-creation. Make the shift from being a consumer of information to being a producer of information.

- Define your research question. Your question frames the rest of your project, sets the scope, and determines the kinds of answers you can find.

- Review previous research on your question. Survey the existing body of relevant knowledge to ensure that your research will be part of a larger conversation.

- Choose your data and methods. For instance, will you be collecting qualitative data, via interviews, or numerical data, via surveys?

- Circle back and consider revising your initial plans. Expect your research question in particular to undergo multiple rounds of refinement as you learn more about your topic.

Good research questions tend to beget more questions. This can be frustrating for those who want to get down to business right away. Try to make room for the unexpected: this is usually how knowledge advances. Many of the most significant discoveries in human history have been made by people who were looking for something else entirely. There are ways to structure your research planning process without over-constraining yourself; the two exercises below are a start, and you can find further methods in the Links and Books section.

The following exercise provides a structured process for advancing your research project planning. After completing it, you’ll be able to do the following:

- describe clearly and concisely the question you’ve chosen to study

- summarise the state of the art in knowledge about the question, and where your project could contribute new insight

- identify the best strategy for gathering and analysing relevant data

In other words, the following provides a systematic means to establish the building blocks of your research project.

Exercise 1: Definition of research question and sources

This exercise prompts you to select and clarify your general interest area, develop a research question, and investigate sources of information. The annotated bibliography will also help you refine your research question so that you can begin the second assignment, a description of the phenomenon you wish to study.

Jot down a few bullet points in response to these two questions, with the understanding that you’ll probably go back and modify your answers as you begin reading other studies relevant to your topic:

- What will be the general topic of your paper?

- What will be the specific topic of your paper?

b) Research question(s)

Use the following guidelines to frame a research question – or questions – that will drive your analysis. As with Part 1 above, you’ll probably find it necessary to change or refine your research question(s) as you complete future assignments.

- Your question should be phrased so that it can’t be answered with a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

- Your question should have more than one plausible answer.

- Your question should draw relationships between two or more concepts; framing the question in terms of How? or What? often works better than asking Why ?

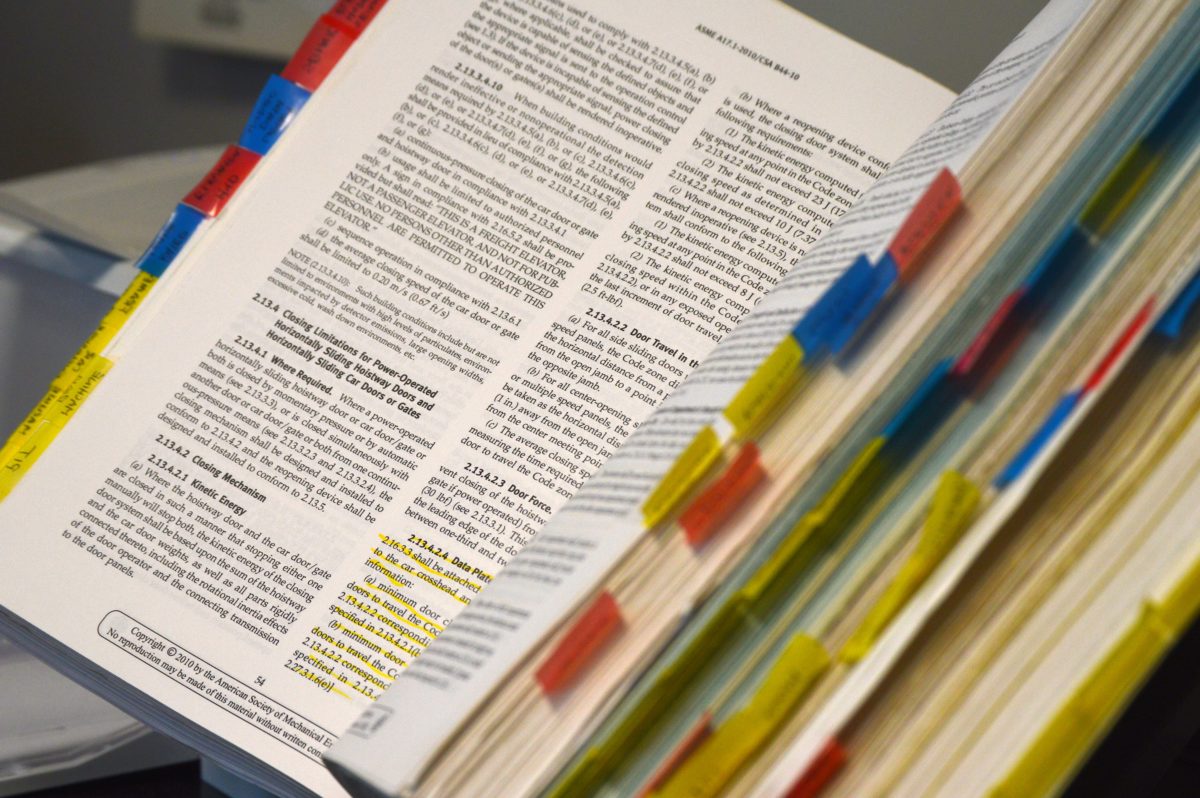

c) Annotated bibliography

Most or all of your background information should come from two sources: scholarly books and journals, or reputable mass media sources. You might be able to access journal articles electronically through your library, using search engines such as JSTOR and Google Scholar. This can save you a great deal of time compared with going to the library in person to search periodicals. General news sources, such as those accessible through LexisNexis, are acceptable, but should be cited sparingly, since they don’t carry the same level of credibility as scholarly sources. As discussed above, unvetted sources such as blogs and Wikipedia should be avoided, because the quality of the information they provide is unreliable and often misleading.

To create an annotated bibliography, provide the following information for at least 10 sources relevant to your specific topic, using the format suggested below.

Name of author(s):

Publication date:

Title of book, chapter, or article:

If a chapter or article, title of journal or book where they appear:

Brief description of this work, including main findings and methods ( c 75 words):

Summary of how this work contributes to your project ( c 75 words):

Brief description of the implications of this work ( c 25 words):

Identify any gap or controversy in knowledge this work points up, and how your project could address those problems ( c 50 words):

Exercise 2: Towards an analysis

Develop a short statement ( c 250 words) about the kind of data that would be useful to address your research question, and how you’d analyse it. Some questions to consider in writing this statement include:

- What are the central concepts or variables in your project? Offer a brief definition of each.

- Do any data sources exist on those concepts or variables, or would you need to collect data?

- Of the analytical strategies you could apply to that data, which would be the most appropriate to answer your question? Which would be the most feasible for you? Consider at least two methods, noting their advantages or disadvantages for your project.

Links & books

One of the best texts ever written about planning and executing research comes from a source that might be unexpected: a 60-year-old work on urban planning by a self-trained scholar. The classic book The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961) by Jane Jacobs (available complete and free of charge via this link ) is worth reading in its entirety just for the pleasure of it. But the final 20 pages – a concluding chapter titled ‘The Kind of Problem a City Is’ – are really about the process of thinking through and investigating a problem. Highly recommended as a window into the craft of research.

Jacobs’s text references an essay on advancing human knowledge by the mathematician Warren Weaver. At the time, Weaver was director of the Rockefeller Foundation, in charge of funding basic research in the natural and medical sciences. Although the essay is titled ‘A Quarter Century in the Natural Sciences’ (1960) and appears at first blush to be merely a summation of one man’s career, it turns out to be something much bigger and more interesting: a meditation on the history of human beings seeking answers to big questions about the world. Weaver goes back to the 17th century to trace the origins of systematic research thinking, with enthusiasm and vivid anecdotes that make the process come alive. The essay is worth reading in its entirety, and is available free of charge via this link .

For those seeking a more in-depth, professional-level discussion of the logic of research design, the political scientist Harvey Starr provides insight in a compact format in the article ‘Cumulation from Proper Specification: Theory, Logic, Research Design, and “Nice” Laws’ (2005). Starr reviews the ‘research triad’, consisting of the interlinked considerations of formulating a question, selecting relevant theories and applying appropriate methods. The full text of the article, published in the scholarly journal Conflict Management and Peace Science , is available, free of charge, via this link .

Finally, the book Getting What You Came For (1992) by Robert Peters is not only an outstanding guide for anyone contemplating graduate school – from the application process onward – but it also includes several excellent chapters on planning and executing research, applicable across a wide variety of subject areas. It was an invaluable resource for me 25 years ago, and it remains in print with good reason; I recommend it to all my students, particularly Chapter 16 (‘The Thesis Topic: Finding It’), Chapter 17 (‘The Thesis Proposal’) and Chapter 18 (‘The Thesis: Writing It’).

How to use ‘possibility thinking’

Have you hit an impasse in your personal or professional life? Answer these questions to open your mind to what’s possible

by Constance de Saint Laurent & Vlad Glăveanu

The nature of reality

How to think about time

This philosopher’s introduction to the nature of time could radically alter how you see your past and imagine your future

by Graeme A Forbes

Cognitive and behavioural therapies

How to stop living on auto-pilot

Are you going through the motions? Use these therapy techniques to set meaningful goals and build a ‘life worth living’

by Kiki Fehling

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Research Process Steps: What they are + How To Follow

There are various approaches to conducting basic and applied research. This article explains the research process steps you should know. Whether you are doing basic research or applied research, there are many ways of doing it. In some ways, each research study is unique since it is conducted at a different time and place.

Conducting research might be difficult, but there are clear processes to follow. The research process starts with a broad idea for a topic. This article will assist you through the research process steps, helping you focus and develop your topic.

Research Process Steps

The research process consists of a series of systematic procedures that a researcher must go through in order to generate knowledge that will be considered valuable by the project and focus on the relevant topic.

To conduct effective research, you must understand the research process steps and follow them. Here are a few steps in the research process to make it easier for you:

Step 1: Identify the Problem

Finding an issue or formulating a research question is the first step. A well-defined research problem will guide the researcher through all stages of the research process, from setting objectives to choosing a technique. There are a number of approaches to get insight into a topic and gain a better understanding of it. Such as:

- A preliminary survey

- Case studies

- Interviews with a small group of people

- Observational survey

Step 2: Evaluate the Literature

A thorough examination of the relevant studies is essential to the research process . It enables the researcher to identify the precise aspects of the problem. Once a problem has been found, the investigator or researcher needs to find out more about it.

This stage gives problem-zone background. It teaches the investigator about previous research, how they were conducted, and its conclusions. The researcher can build consistency between his work and others through a literature review. Such a review exposes the researcher to a more significant body of knowledge and helps him follow the research process efficiently.

Step 3: Create Hypotheses

Formulating an original hypothesis is the next logical step after narrowing down the research topic and defining it. A belief solves logical relationships between variables. In order to establish a hypothesis, a researcher must have a certain amount of expertise in the field.

It is important for researchers to keep in mind while formulating a hypothesis that it must be based on the research topic. Researchers are able to concentrate their efforts and stay committed to their objectives when they develop theories to guide their work.

Step 4: The Research Design

Research design is the plan for achieving objectives and answering research questions. It outlines how to get the relevant information. Its goal is to design research to test hypotheses, address the research questions, and provide decision-making insights.

The research design aims to minimize the time, money, and effort required to acquire meaningful evidence. This plan fits into four categories:

- Exploration and Surveys

- Data Analysis

- Observation

Step 5: Describe Population

Research projects usually look at a specific group of people, facilities, or how technology is used in the business. In research, the term population refers to this study group. The research topic and purpose help determine the study group.

Suppose a researcher wishes to investigate a certain group of people in the community. In that case, the research could target a specific age group, males or females, a geographic location, or an ethnic group. A final step in a study’s design is to specify its sample or population so that the results may be generalized.

Step 6: Data Collection

Data collection is important in obtaining the knowledge or information required to answer the research issue. Every research collected data, either from the literature or the people being studied. Data must be collected from the two categories of researchers. These sources may provide primary data.

- Questionnaire

Secondary data categories are:

- Literature survey

- Official, unofficial reports

- An approach based on library resources

Step 7: Data Analysis

During research design, the researcher plans data analysis. After collecting data, the researcher analyzes it. The data is examined based on the approach in this step. The research findings are reviewed and reported.

Data analysis involves a number of closely related stages, such as setting up categories, applying these categories to raw data through coding and tabulation, and then drawing statistical conclusions. The researcher can examine the acquired data using a variety of statistical methods.

Step 8: The Report-writing

After completing these steps, the researcher must prepare a report detailing his findings. The report must be carefully composed with the following in mind:

- The Layout: On the first page, the title, date, acknowledgments, and preface should be on the report. A table of contents should be followed by a list of tables, graphs, and charts if any.

- Introduction: It should state the research’s purpose and methods. This section should include the study’s scope and limits.

- Summary of Findings: A non-technical summary of findings and recommendations will follow the introduction. The findings should be summarized if they’re lengthy.

- Principal Report: The main body of the report should make sense and be broken up into sections that are easy to understand.

- Conclusion: The researcher should restate his findings at the end of the main text. It’s the final result.

LEARN ABOUT: 12 Best Tools for Researchers

The research process involves several steps that make it easy to complete the research successfully. The steps in the research process described above depend on each other, and the order must be kept. So, if we want to do a research project, we should follow the research process steps.

QuestionPro’s enterprise-grade research platform can collect survey and qualitative observation data. The tool’s nature allows for data processing and essential decisions. The platform lets you store and process data. Start immediately!

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Employee Lifecycle Management Software: Top of 2024

Apr 15, 2024

Top 15 Sentiment Analysis Software That Should Be on Your List

Top 13 A/B Testing Software for Optimizing Your Website

Apr 12, 2024

21 Best Contact Center Experience Software in 2024

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

WashU Libraries

Conducting research, the research process.

- Step 1: Exploring an idea

- Step 2: Finding background info.

- Step 3: Gathering more info.

- Get it This link opens in a new window

- Step 5: Evaluating your sources

- Step 6: Citing your sources

- FAQs This link opens in a new window

- Library Vocabulary

- Research in the Humanities

- Research in the Social Sciences

- Research in the Sciences

Step 1: Exploring Your Research Idea and Constructing Your Search

If you know you are interested in doing research in a broad subject area, try to think of ways you can make your subject more specific. One way is by stating your topic as a question. For example, if you are interested in writing about sleep disorders you might ask yourself the following question: Can sleep disorders affect academic success in college students? If you don't have enough information to express your topic idea as a specific question, do some background reading first.

Step 2: Finding Background Information

Consult general reference sources, e.g., an encyclopedia, before jumping into more specialized and specific searches. Encyclopedias provide information on key concepts, context, and vocabulary for many different fields. Subject-specific encyclopedias will provide additional information that may lead to ideas for additional search terms.

Step 3: Gathering More Information

Use the search terms/keywords you brainstormed in Step 1: Exploring your Research Idea to search the Classic Catalog . Note where the item is located in the library and the circulation status. When you find a good book, scan the bibliography for additional sources. Look for book-length bibliographies, literature reviews, and annual reviews in your research area; this type of resource lists hundreds of books and articles in one subject area. To find these resources, use your keywords/search terms followed by the word "AND bibliographies" in the Classic Catalog .

Step 4: Locating Current Research

Journal articles are a great resource for learning about cutting-edge research in your area. Indexes and databases allow you to search across many journal publishers at once to find citations, abstracts, and full-text to articles.

Step 5: Evaluating Your Sources

As you search and find citations and/or abstracts for specific books, articles, or websites, consider the following established criteria for evaluating the quality of books, journal articles, and websites.

Step 6: Cite What You Find in Discipline-Appropriate Format

When conducting research, it’s necessary to document sources you use; commonly, this is called citing your sources. Citing your sources is an important part of research and scholarship; it is important to give credit to the ideas of others. In addition, readers of your work may want to find and read some of the sources you used. Different academic disciplines follow different citation styles. Two of the more common citation styles are APA or MLA. Failing to cite properly is plagiarism. For further details on other aspects of plagiarism, consult WU’s Academic Integrity Policy .

- Research Tips

- Responsible and Efficient Literature Searching

- Next: Step 1: Exploring an idea >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 3:23 PM

- URL: https://libguides.wustl.edu/research

Key Steps in the Research Process - A Comprehensive Guide

Embarking on a research journey can be both thrilling and challenging. Whether you're a student, journalist, or simply inquisitive about a subject, grasping the research process steps is vital for conducting thorough and efficient research. In this all-encompassing guide, we'll navigate you through the pivotal stages of what is the research process, from pinpointing your topic to showcasing your discoveries.

We'll delve into how to formulate a robust research question, undertake preliminary research, and devise a structured research plan. You'll acquire strategies for gathering and scrutinizing data, along with advice for effectively disseminating your findings. By adhering to these steps in the research process, you'll be fully prepared to confront any research endeavor that presents itself.

Step 1: Identify and Develop Your Topic

Identifying and cultivating a research topic is the foundational first step in the research process. Kick off by brainstorming potential subjects that captivate your interest, as this will fuel your enthusiasm throughout the endeavor.

Employ the following tactics to spark ideas and understand what is the first step in the research process:

- Review course materials, lecture notes, and assigned readings for inspiration

- Engage in discussions with peers, professors, or experts in the field

- Investigate current events, news pieces, or social media trends pertinent to your field of study to uncover valuable market research insights.

- Reflect on personal experiences or observations that have sparked your curiosity

Once you've compiled a roster of possible topics, engage in preliminary research to evaluate the viability and breadth of each concept. This initial probe may encompass various research steps and procedures to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the topics at hand.

- Scanning Wikipedia articles or other general reference sources for an overview

- Searching for scholarly articles, books, or media related to your topic

- Identifying key concepts, theories, or debates within the field

- Considering the availability of primary sources or data for analysis

While amassing background knowledge, begin to concentrate your focus and hone your topic. Target a subject that is specific enough to be feasible within your project's limits, yet expansive enough to permit substantial analysis. Mull over the following inquiries to steer your topic refinement and address the research problem effectively:

- What aspect of the topic am I most interested in exploring?

- What questions or problems related to this topic remain unanswered or unresolved?

- How can I contribute new insights or perspectives to the existing body of knowledge?

- What resources and methods will I need to investigate this topic effectively?

Step 2: Conduct Preliminary Research

Having pinpointed a promising research topic, it's time to plunge into preliminary research. This essential phase enables you to deepen your grasp of the subject and evaluate the practicality of your project. Here are some pivotal tactics for executing effective preliminary research using various library resources:

- Literature Review

To effectively embark on your scholarly journey, it's essential to consult a broad spectrum of sources, thereby enriching your understanding with the breadth of academic research available on your topic. This exploration may encompass a variety of materials.

- Online catalogs of libraries (local, regional, national, and special)

- Meta-catalogs and subject-specific online article databases

- Digital institutional repositories and open access resources

- Works cited in scholarly books and articles

- Print bibliographies and internet sources

- Websites of major nonprofit organizations, research institutes, museums, universities, and government agencies

- Trade and scholarly publishers

- Discussions with fellow scholars and peers

- Identify Key Debates

Engaging with the wealth of recently published materials and seminal works in your field is a pivotal part of the research process definition. Focus on discerning the core ideas, debates, and arguments that define your topic, which will in turn sharpen your research focus and guide you toward formulating pertinent research questions.

- Narrow Your Focus

Hone your topic by leveraging your initial findings to tackle a specific issue or facet within the larger subject, a fundamental step in the research process steps. Consider various factors that could influence the direction and scope of your inquiry.

- Subtopics and specific issues

- Key debates and controversies

- Timeframes and geographical locations

- Organizations or groups of people involved

A thorough evaluation of existing literature and a comprehensive assessment of the information at hand will pinpoint the exact dimensions of the issue you aim to explore. This methodology ensures alignment with prior research, optimizes resources, and can bolster your case when seeking research funding by demonstrating a well-founded approach.

Step 3: Establish Your Research Question

Having completed your preliminary research and topic refinement, the next vital phase involves formulating a precise and focused research question. This question, a cornerstone among research process steps, will steer your investigation, keeping it aligned with relevant data and insights. When devising your research question, take into account these critical factors:

Initiate your inquiry by defining the requirements and goals of your study, a key step in the research process steps. Whether you're testing a hypothesis, analyzing data, or constructing and supporting an argument, grasping the intent of your research is crucial for framing your question effectively.

Ensure that your research question is feasible, given your constraints in time and word count, an important consideration in the research process steps. Steer clear of questions that are either too expansive or too constricted, as they may impede your capacity to conduct a comprehensive analysis.

Your research question should transcend a mere 'yes' or 'no' response, prompting a thorough engagement with the research process steps. It should foster a comprehensive exploration of the topic, facilitating the analysis of issues or problems beyond just a basic description.

- Researchability

Ensure that your research question opens the door to quality research materials, including academic books and refereed journal articles. It's essential to weigh the accessibility of primary data and secondary data that will bolster your investigative efforts.

When establishing your research question, take the following steps:

- Identify the specific aspect of your general topic that you want to explore

- Hypothesize the path your answer might take, developing a hypothesis after formulating the question

- Steer clear of certain types of questions in your research process steps, such as those that are deceptively simple, fictional, stacked, semantic, impossible-to-answer, opinion or ethical, and anachronistic, to maintain the integrity of your inquiry.

- Conduct a self-test on your research question to confirm it adheres to the research process steps, ensuring it is flexible, testable, clear, precise, and underscores a distinct reason for its importance.

By meticulously formulating your research question, you're establishing a solid groundwork for the subsequent research process steps, guaranteeing that your efforts are directed, efficient, and yield productive outcomes.

Step 4: Develop a Research Plan

Having formulated a precise research question, the ensuing phase involves developing a detailed research plan. This plan, integral to the research process steps, acts as a navigational guide for your project, keeping you organized, concentrated, and on a clear path to accomplishing your research objectives. When devising your research plan, consider these pivotal components:

- Project Goals and Objectives

Articulate the specific aims and objectives of your research project with clarity. These should be in harmony with your research question and provide a structured framework for your investigation, ultimately aligning with your overarching business goals.

- Research Methods

Select the most appropriate research tools and statistical methods to address your question effectively. This may include a variety of qualitative and quantitative approaches to ensure comprehensive analysis.

- Quantitative methods (e.g., surveys, experiments)

- Qualitative methods (e.g., interviews, focus groups)

- Mixed methods (combining quantitative and qualitative approaches)

- Access to databases, archives, or special collections

- Specialized equipment or software

- Funding for travel, materials, or participant compensation

- Assistance from research assistants, librarians, or subject matter experts

- Participant Recruitment

If your research involves human subjects, develop a strategic plan for recruiting participants. Consider factors such as the inclusion of diverse ethnic groups and the use of user interviews to gather rich, qualitative data.

- Target population and sample size

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Recruitment strategies (e.g., flyers, social media, snowball sampling)

- Informed consent procedures

- Instruments or tools for gathering data (e.g., questionnaires, interview guides)

- Data storage and management protocols

- Statistical or qualitative analysis techniques

- Software or tools for data analysis (e.g., SPSS, NVivo)

Create a realistic project strategy for your research project, breaking it down into manageable stages or milestones. Consider factors such as resource availability and potential bottlenecks.

- Literature review and background research

- IRB approval (if applicable)

- Participant recruitment and data collection

- Data analysis and interpretation

- Writing and revising your findings

- Dissemination of results (e.g., presentations, publications)

By developing a comprehensive research plan, incorporating key research process steps, you'll be better equipped to anticipate challenges, allocate resources effectively, and ensure the integrity and rigor of your research process. Remember to remain flexible and adaptable to navigate unexpected obstacles or opportunities that may arise.

Step 5: Conduct the Research

With your research plan in place, it's time to dive into the data collection phase. As you conduct your research, adhere to the established research process steps to ensure the integrity and quality of your findings.

Conduct your research in accordance with federal regulations, state laws, institutional SOPs, and policies. Familiarize yourself with the IRB-approved protocol and follow it diligently, as part of the essential research process steps.

- Roles and Responsibilities

Understand and adhere to the roles and responsibilities of the principal investigator and other research team members. Maintain open communication lines with all stakeholders, including the sponsor and IRB, to foster cross-functional collaboration.

- Data Management

Develop and maintain an effective system for data collection and storage, utilizing advanced research tools. Ensure that each member of the research team has seamless access to the most up-to-date documents, including the informed consent document, protocol, and case report forms.

- Quality Assurance

Implement comprehensive quality assurance measures to verify that the study adheres strictly to the IRB-approved protocol, institutional policy, and all required regulations. Confirm that all study activities are executed as planned and that any deviations are addressed with precision and appropriateness.

- Participant Eligibility

As part of the essential research process steps, verify that potential study subjects meet all eligibility criteria and none of the ineligibility criteria before advancing with the research.

To maintain the highest standards of academic integrity and ethical conduct:

- Conduct research with unwavering honesty in all facets, including experimental design, data generation, and analysis, as well as the publication of results, as these are critical research process steps.

- Maintain a climate conducive to conducting research in strict accordance with good research practices, ensuring each step of the research process is meticulously observed.

- Provide appropriate supervision and training for researchers.

- Encourage open discussion of ideas and the widest dissemination of results possible.

- Keep clear and accurate records of research methods and results.

- Exercise a duty of care to all those involved in the research.

When collecting and assimilating data:

- Use professional online data analysis tools to streamline the process.

- Use metadata for context

- Assign codes or labels to facilitate grouping or comparison

- Convert data into different formats or scales for compatibility

- Organize documents in both the study participant and investigator's study regulatory files, creating a central repository for easy access and reference, as this organization is a pivotal step in the research process.

By adhering to these guidelines and upholding a commitment to ethical and rigorous research practices, you'll be well-equipped to conduct your research effectively and contribute meaningful insights to your field of study, thereby enhancing the integrity of the research process steps.

Step 6: Analyze and Interpret Data

Embarking on the research process steps, once you have gathered your research data, the subsequent critical phase is to delve into analysis and interpretation. This stage demands a meticulous examination of the data, spotting trends, and forging insightful conclusions that directly respond to your research question. Reflect on these tactics for a robust approach to data analysis and interpretation:

- Organize and Clean Your Data

A pivotal aspect of the research process steps is to start by structuring your data in an orderly and coherent fashion. This organizational task may encompass:

- Creating a spreadsheet or database to store your data

- Assigning codes or labels to facilitate grouping or comparison

- Cleaning the data by removing any errors, inconsistencies, or missing values

- Converting data into different formats or scales for compatibility

- Calculating measures of central tendency (mean, median, mode)

- Determining measures of variability (range, standard deviation)

- Creating frequency tables or histograms to visualize the distribution of your data

- Identifying any outliers or unusual patterns in your data

- Perform Inferential Analysis

Integral to the research process steps, you might engage in inferential analysis to evaluate hypotheses or extrapolate findings to a broader demographic, contingent on your research design and query. This analytical step may include:

- Selecting appropriate statistical tests (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA, regression analysis)

- As part of the research process steps, establishing a significance threshold (e.g., p < 0.05) is essential to gauge the likelihood of your results being a random occurrence rather than a significant finding.

- Interpreting the results of your statistical tests in the context of your research question

- Considering the practical significance of your findings, in addition to statistical significance

When interpreting your data, it's essential to:

- Look for relationships, patterns, and trends in your data

- Consider alternative explanations for your findings

- Acknowledge any limitations or potential biases in your research design or data collection

- Leverage data visualization techniques such as graphs, charts, and infographics to articulate your research findings with clarity and impact, thereby enhancing the communicative value of your data.

- Seek feedback from peers, mentors, or subject matter experts to validate your interpretations

It's important to recognize that data interpretation is a cyclical process that hinges on critical thinking, inventiveness, and the readiness to refine your conclusions with emerging insights. By tackling data analysis and interpretation with diligence and openness, you're setting the stage to derive meaningful and justifiable inferences from your research, in line with the research process steps.

Step 7: Present the Findings

After meticulous analysis and interpretation of your research findings, as dictated by the research process steps, the moment arrives to disseminate your insights. Effectively presenting your research is key to captivating your audience and conveying the importance of your findings. Employ these strategies to create an engaging and persuasive presentation:

- Organize Your Findings :

Use the PEEL method to structure your presentation:

- Point: Clearly state your main argument or finding

- Evidence: Present the data and analysis that support your point

- Explanation: Provide context and interpret the significance of your evidence

- Link: Connect your findings to the broader research question or field

- Tailor Your Message

Understanding your audience is crucial to effective communication. When presenting your research, it's important to tailor your message to their background, interests, and level of expertise, effectively employing user personas to guide your approach.

- Use clear, concise language and explain technical terms

- Highlight what makes your research unique and impactful

- Craft a compelling narrative with a clear structure and hook

- Share the big picture, emphasizing the significance of your findings

- Engage Your Audience : Make your presentation enjoyable and memorable by incorporating creative elements:

- Use visual aids, such as tables, charts, and graphs, to communicate your findings effectively

- To vividly convey your research journey, consider employing storytelling techniques, such as UX comics or storyboards, which can make complex information more accessible and engaging.

- Injecting humor and personality into your presentation can be a powerful tool for communication. Utilize funny messages or GIFs to lighten the mood, breaking up tension and refocusing attention, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of humor in communication.

By adhering to these strategies, you'll be well-prepared to present your research findings in a manner that's both clear and captivating. Ensure you follow research process steps such as citing your sources accurately and discussing the broader implications of your work, providing actionable recommendations, and delineating the subsequent phases for integrating your findings into broader practice or policy frameworks.

The research process is an intricate journey that demands meticulous planning, steadfast execution, and incisive analysis. By adhering to the fundamental research process steps outlined in this guide, from pinpointing your topic to showcasing your findings, you're setting yourself up for conducting research that's both effective and influential. Keep in mind that the research journey is iterative, often necessitating revisits to certain stages as fresh insights surface or unforeseen challenges emerge.

As you commence your research journey, seize the chance to contribute novel insights to your field and forge a positive global impact. By tackling your research with curiosity, integrity, and a dedication to excellence, you're paving the way towards attaining your research aspirations and making a substantial difference with your work, all while following the critical research process steps.

Sign up for more like this.

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Project – Definition, Writing Guide and Ideas

Research Project – Definition, Writing Guide and Ideas

Table of Contents

Research Project

Definition :

Research Project is a planned and systematic investigation into a specific area of interest or problem, with the goal of generating new knowledge, insights, or solutions. It typically involves identifying a research question or hypothesis, designing a study to test it, collecting and analyzing data, and drawing conclusions based on the findings.

Types of Research Project

Types of Research Projects are as follows:

Basic Research

This type of research focuses on advancing knowledge and understanding of a subject area or phenomenon, without any specific application or practical use in mind. The primary goal is to expand scientific or theoretical knowledge in a particular field.

Applied Research

Applied research is aimed at solving practical problems or addressing specific issues. This type of research seeks to develop solutions or improve existing products, services or processes.

Action Research

Action research is conducted by practitioners and aimed at solving specific problems or improving practices in a particular context. It involves collaboration between researchers and practitioners, and often involves iterative cycles of data collection and analysis, with the goal of improving practices.

Quantitative Research

This type of research uses numerical data to investigate relationships between variables or to test hypotheses. It typically involves large-scale data collection through surveys, experiments, or secondary data analysis.

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research focuses on understanding and interpreting phenomena from the perspective of the people involved. It involves collecting and analyzing data in the form of text, images, or other non-numerical forms.

Mixed Methods Research

Mixed methods research combines elements of both quantitative and qualitative research, using multiple data sources and methods to gain a more comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon.

Longitudinal Research

This type of research involves studying a group of individuals or phenomena over an extended period of time, often years or decades. It is useful for understanding changes and developments over time.

Case Study Research

Case study research involves in-depth investigation of a particular case or phenomenon, often within a specific context. It is useful for understanding complex phenomena in their real-life settings.

Participatory Research

Participatory research involves active involvement of the people or communities being studied in the research process. It emphasizes collaboration, empowerment, and the co-production of knowledge.

Research Project Methodology

Research Project Methodology refers to the process of conducting research in an organized and systematic manner to answer a specific research question or to test a hypothesis. A well-designed research project methodology ensures that the research is rigorous, valid, and reliable, and that the findings are meaningful and can be used to inform decision-making.

There are several steps involved in research project methodology, which are described below:

Define the Research Question

The first step in any research project is to clearly define the research question or problem. This involves identifying the purpose of the research, the scope of the research, and the key variables that will be studied.

Develop a Research Plan

Once the research question has been defined, the next step is to develop a research plan. This plan outlines the methodology that will be used to collect and analyze data, including the research design, sampling strategy, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques.

Collect Data

The data collection phase involves gathering information through various methods, such as surveys, interviews, observations, experiments, or secondary data analysis. The data collected should be relevant to the research question and should be of sufficient quantity and quality to enable meaningful analysis.

Analyze Data

Once the data has been collected, it is analyzed using appropriate statistical techniques or other methods. The analysis should be guided by the research question and should aim to identify patterns, trends, relationships, or other insights that can inform the research findings.

Interpret and Report Findings

The final step in the research project methodology is to interpret the findings and report them in a clear and concise manner. This involves summarizing the results, discussing their implications, and drawing conclusions that can be used to inform decision-making.

Research Project Writing Guide

Here are some guidelines to help you in writing a successful research project:

- Choose a topic: Choose a topic that you are interested in and that is relevant to your field of study. It is important to choose a topic that is specific and focused enough to allow for in-depth research and analysis.

- Conduct a literature review : Conduct a thorough review of the existing research on your topic. This will help you to identify gaps in the literature and to develop a research question or hypothesis.

- Develop a research question or hypothesis : Based on your literature review, develop a clear research question or hypothesis that you will investigate in your study.

- Design your study: Choose an appropriate research design and methodology to answer your research question or test your hypothesis. This may include choosing a sample, selecting measures or instruments, and determining data collection methods.

- Collect data: Collect data using your chosen methods and instruments. Be sure to follow ethical guidelines and obtain informed consent from participants if necessary.

- Analyze data: Analyze your data using appropriate statistical or qualitative methods. Be sure to clearly report your findings and provide interpretations based on your research question or hypothesis.

- Discuss your findings : Discuss your findings in the context of the existing literature and your research question or hypothesis. Identify any limitations or implications of your study and suggest directions for future research.

- Write your project: Write your research project in a clear and organized manner, following the appropriate format and style guidelines for your field of study. Be sure to include an introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion.

- Revise and edit: Revise and edit your project for clarity, coherence, and accuracy. Be sure to proofread for spelling, grammar, and formatting errors.

- Cite your sources: Cite your sources accurately and appropriately using the appropriate citation style for your field of study.

Examples of Research Projects

Some Examples of Research Projects are as follows:

- Investigating the effects of a new medication on patients with a particular disease or condition.

- Exploring the impact of exercise on mental health and well-being.

- Studying the effectiveness of a new teaching method in improving student learning outcomes.

- Examining the impact of social media on political participation and engagement.

- Investigating the efficacy of a new therapy for a specific mental health disorder.

- Exploring the use of renewable energy sources in reducing carbon emissions and mitigating climate change.

- Studying the effects of a new agricultural technique on crop yields and environmental sustainability.

- Investigating the effectiveness of a new technology in improving business productivity and efficiency.

- Examining the impact of a new public policy on social inequality and access to resources.

- Exploring the factors that influence consumer behavior in a specific market.

Characteristics of Research Project

Here are some of the characteristics that are often associated with research projects:

- Clear objective: A research project is designed to answer a specific question or solve a particular problem. The objective of the research should be clearly defined from the outset.

- Systematic approach: A research project is typically carried out using a structured and systematic approach that involves careful planning, data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

- Rigorous methodology: A research project should employ a rigorous methodology that is appropriate for the research question being investigated. This may involve the use of statistical analysis, surveys, experiments, or other methods.

- Data collection : A research project involves collecting data from a variety of sources, including primary sources (such as surveys or experiments) and secondary sources (such as published literature or databases).

- Analysis and interpretation : Once the data has been collected, it needs to be analyzed and interpreted. This involves using statistical techniques or other methods to identify patterns or relationships in the data.

- Conclusion and implications : A research project should lead to a clear conclusion that answers the research question. It should also identify the implications of the findings for future research or practice.

- Communication: The results of the research project should be communicated clearly and effectively, using appropriate language and visual aids, to a range of audiences, including peers, stakeholders, and the wider public.

Importance of Research Project

Research projects are an essential part of the process of generating new knowledge and advancing our understanding of various fields of study. Here are some of the key reasons why research projects are important:

- Advancing knowledge : Research projects are designed to generate new knowledge and insights into particular topics or questions. This knowledge can be used to inform policies, practices, and decision-making processes across a range of fields.

- Solving problems: Research projects can help to identify solutions to real-world problems by providing a better understanding of the causes and effects of particular issues.

- Developing new technologies: Research projects can lead to the development of new technologies or products that can improve people’s lives or address societal challenges.

- Improving health outcomes: Research projects can contribute to improving health outcomes by identifying new treatments, diagnostic tools, or preventive strategies.

- Enhancing education: Research projects can enhance education by providing new insights into teaching and learning methods, curriculum development, and student learning outcomes.

- Informing public policy : Research projects can inform public policy by providing evidence-based recommendations and guidance on issues related to health, education, environment, social justice, and other areas.

- Enhancing professional development : Research projects can enhance the professional development of researchers by providing opportunities to develop new skills, collaborate with colleagues, and share knowledge with others.

Research Project Ideas

Following are some Research Project Ideas:

Field: Psychology

- Investigating the impact of social support on coping strategies among individuals with chronic illnesses.

- Exploring the relationship between childhood trauma and adult attachment styles.

- Examining the effects of exercise on cognitive function and brain health in older adults.

- Investigating the impact of sleep deprivation on decision making and risk-taking behavior.

- Exploring the relationship between personality traits and leadership styles in the workplace.

- Examining the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for treating anxiety disorders.

- Investigating the relationship between social comparison and body dissatisfaction in young women.

- Exploring the impact of parenting styles on children’s emotional regulation and behavior.

- Investigating the effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions for treating depression.

- Examining the relationship between childhood adversity and later-life health outcomes.

Field: Economics

- Analyzing the impact of trade agreements on economic growth in developing countries.

- Examining the effects of tax policy on income distribution and poverty reduction.

- Investigating the relationship between foreign aid and economic development in low-income countries.

- Exploring the impact of globalization on labor markets and job displacement.

- Analyzing the impact of minimum wage laws on employment and income levels.

- Investigating the effectiveness of monetary policy in managing inflation and unemployment.

- Examining the relationship between economic freedom and entrepreneurship.

- Analyzing the impact of income inequality on social mobility and economic opportunity.

- Investigating the role of education in economic development.

- Examining the effectiveness of different healthcare financing systems in promoting health equity.

Field: Sociology

- Investigating the impact of social media on political polarization and civic engagement.

- Examining the effects of neighborhood characteristics on health outcomes.

- Analyzing the impact of immigration policies on social integration and cultural diversity.

- Investigating the relationship between social support and mental health outcomes in older adults.

- Exploring the impact of income inequality on social cohesion and trust.

- Analyzing the effects of gender and race discrimination on career advancement and pay equity.

- Investigating the relationship between social networks and health behaviors.

- Examining the effectiveness of community-based interventions for reducing crime and violence.

- Analyzing the impact of social class on cultural consumption and taste.

- Investigating the relationship between religious affiliation and social attitudes.

Field: Computer Science

- Developing an algorithm for detecting fake news on social media.

- Investigating the effectiveness of different machine learning algorithms for image recognition.

- Developing a natural language processing tool for sentiment analysis of customer reviews.

- Analyzing the security implications of blockchain technology for online transactions.

- Investigating the effectiveness of different recommendation algorithms for personalized advertising.

- Developing an artificial intelligence chatbot for mental health counseling.

- Investigating the effectiveness of different algorithms for optimizing online advertising campaigns.

- Developing a machine learning model for predicting consumer behavior in online marketplaces.

- Analyzing the privacy implications of different data sharing policies for online platforms.

- Investigating the effectiveness of different algorithms for predicting stock market trends.

Field: Education

- Investigating the impact of teacher-student relationships on academic achievement.

- Analyzing the effectiveness of different pedagogical approaches for promoting student engagement and motivation.

- Examining the effects of school choice policies on academic achievement and social mobility.

- Investigating the impact of technology on learning outcomes and academic achievement.

- Analyzing the effects of school funding disparities on educational equity and achievement gaps.

- Investigating the relationship between school climate and student mental health outcomes.

- Examining the effectiveness of different teaching strategies for promoting critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

- Investigating the impact of social-emotional learning programs on student behavior and academic achievement.

- Analyzing the effects of standardized testing on student motivation and academic achievement.

Field: Environmental Science

- Investigating the impact of climate change on species distribution and biodiversity.

- Analyzing the effectiveness of different renewable energy technologies in reducing carbon emissions.

- Examining the impact of air pollution on human health outcomes.

- Investigating the relationship between urbanization and deforestation in developing countries.

- Analyzing the effects of ocean acidification on marine ecosystems and biodiversity.

- Investigating the impact of land use change on soil fertility and ecosystem services.

- Analyzing the effectiveness of different conservation policies and programs for protecting endangered species and habitats.

- Investigating the relationship between climate change and water resources in arid regions.

- Examining the impact of plastic pollution on marine ecosystems and biodiversity.

- Investigating the effects of different agricultural practices on soil health and nutrient cycling.

Field: Linguistics

- Analyzing the impact of language diversity on social integration and cultural identity.

- Investigating the relationship between language and cognition in bilingual individuals.

- Examining the effects of language contact and language change on linguistic diversity.

- Investigating the role of language in shaping cultural norms and values.

- Analyzing the effectiveness of different language teaching methodologies for second language acquisition.

- Investigating the relationship between language proficiency and academic achievement.

- Examining the impact of language policy on language use and language attitudes.

- Investigating the role of language in shaping gender and social identities.

- Analyzing the effects of dialect contact on language variation and change.

- Investigating the relationship between language and emotion expression.

Field: Political Science

- Analyzing the impact of electoral systems on women’s political representation.

- Investigating the relationship between political ideology and attitudes towards immigration.

- Examining the effects of political polarization on democratic institutions and political stability.

- Investigating the impact of social media on political participation and civic engagement.

- Analyzing the effects of authoritarianism on human rights and civil liberties.

- Investigating the relationship between public opinion and foreign policy decisions.

- Examining the impact of international organizations on global governance and cooperation.

- Investigating the effectiveness of different conflict resolution strategies in resolving ethnic and religious conflicts.

- Analyzing the effects of corruption on economic development and political stability.

- Investigating the role of international law in regulating global governance and human rights.

Field: Medicine

- Investigating the impact of lifestyle factors on chronic disease risk and prevention.

- Examining the effectiveness of different treatment approaches for mental health disorders.

- Investigating the relationship between genetics and disease susceptibility.

- Analyzing the effects of social determinants of health on health outcomes and health disparities.

- Investigating the impact of different healthcare delivery models on patient outcomes and cost effectiveness.

- Examining the effectiveness of different prevention and treatment strategies for infectious diseases.

- Investigating the relationship between healthcare provider communication skills and patient satisfaction and outcomes.

- Analyzing the effects of medical error and patient safety on healthcare quality and outcomes.

- Investigating the impact of different pharmaceutical pricing policies on access to essential medicines.

- Examining the effectiveness of different rehabilitation approaches for improving function and quality of life in individuals with disabilities.

Field: Anthropology

- Analyzing the impact of colonialism on indigenous cultures and identities.

- Investigating the relationship between cultural practices and health outcomes in different populations.

- Examining the effects of globalization on cultural diversity and cultural exchange.

- Investigating the role of language in cultural transmission and preservation.

- Analyzing the effects of cultural contact on cultural change and adaptation.

- Investigating the impact of different migration policies on immigrant integration and acculturation.

- Examining the role of gender and sexuality in cultural norms and values.

- Investigating the impact of cultural heritage preservation on tourism and economic development.

- Analyzing the effects of cultural revitalization movements on indigenous communities.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

- High School

- College Search

- College Admissions

- Financial Aid

- College Life

Your Guide to Conducting Independent Research Projects

For me, asking questions is the best way to stay curious and inspire others.

I am currently earning my undergraduate degree in Dance and minor in Modern Languages – French at Point Park University . I am a part of their honors program in which I have been given various opportunities to do research that has been published and presented at national conferences.

I want to note that you do not have to do research through an organization. The project I’m currently working on is for a conference and will not receive any academic credit for it.

You probably have already done a research project and did not even realize it. I was first introduced to how to do research in high school, so after finding what worked best for me, I wanted to share my process to make the project less daunting and more fun.

Step 1: Define the project

What is your subject?

Normally the subject is related to your major, but if you are interested in a subject, your project can be based on something you have no previous knowledge about.

When applying to conferences, my research typically fit under a certain category and theme. When choosing a subject, look at the requirements closely to determine if the subject will work.

What is its purpose?

Answer the question: Why do I want to do this research project? Is it to forward your academic goals, spread awareness, inform or persuade a group of people, or to learn more about a subject you are passionate about?