Find anything you save across the site in your account

A Guide to Thesis Writing That Is a Guide to Life

“How to Write a Thesis,” by Umberto Eco, first appeared on Italian bookshelves in 1977. For Eco, the playful philosopher and novelist best known for his work on semiotics, there was a practical reason for writing it. Up until 1999, a thesis of original research was required of every student pursuing the Italian equivalent of a bachelor’s degree. Collecting his thoughts on the thesis process would save him the trouble of reciting the same advice to students each year. Since its publication, “How to Write a Thesis” has gone through twenty-three editions in Italy and has been translated into at least seventeen languages. Its first English edition is only now available, in a translation by Caterina Mongiat Farina and Geoff Farina.

We in the English-speaking world have survived thirty-seven years without “How to Write a Thesis.” Why bother with it now? After all, Eco wrote his thesis-writing manual before the advent of widespread word processing and the Internet. There are long passages devoted to quaint technologies such as note cards and address books, careful strategies for how to overcome the limitations of your local library. But the book’s enduring appeal—the reason it might interest someone whose life no longer demands the writing of anything longer than an e-mail—has little to do with the rigors of undergraduate honors requirements. Instead, it’s about what, in Eco’s rhapsodic and often funny book, the thesis represents: a magical process of self-realization, a kind of careful, curious engagement with the world that need not end in one’s early twenties. “Your thesis,” Eco foretells, “is like your first love: it will be difficult to forget.” By mastering the demands and protocols of the fusty old thesis, Eco passionately demonstrates, we become equipped for a world outside ourselves—a world of ideas, philosophies, and debates.

Eco’s career has been defined by a desire to share the rarefied concerns of academia with a broader reading public. He wrote a novel that enacted literary theory (“The Name of the Rose”) and a children’s book about atoms conscientiously objecting to their fate as war machines (“The Bomb and the General”). “How to Write a Thesis” is sparked by the wish to give any student with the desire and a respect for the process the tools for producing a rigorous and meaningful piece of writing. “A more just society,” Eco writes at the book’s outset, would be one where anyone with “true aspirations” would be supported by the state, regardless of their background or resources. Our society does not quite work that way. It is the students of privilege, the beneficiaries of the best training available, who tend to initiate and then breeze through the thesis process.

Eco walks students through the craft and rewards of sustained research, the nuances of outlining, different systems for collating one’s research notes, what to do if—per Eco’s invocation of thesis-as-first-love—you fear that someone’s made all these moves before. There are broad strategies for laying out the project’s “center” and “periphery” as well as philosophical asides about originality and attribution. “Work on a contemporary author as if he were ancient, and an ancient one as if he were contemporary,” Eco wisely advises. “You will have more fun and write a better thesis.” Other suggestions may strike the modern student as anachronistic, such as the novel idea of using an address book to keep a log of one’s sources.

But there are also old-fashioned approaches that seem more useful than ever: he recommends, for instance, a system of sortable index cards to explore a project’s potential trajectories. Moments like these make “How to Write a Thesis” feel like an instruction manual for finding one’s center in a dizzying era of information overload. Consider Eco’s caution against “the alibi of photocopies”: “A student makes hundreds of pages of photocopies and takes them home, and the manual labor he exercises in doing so gives him the impression that he possesses the work. Owning the photocopies exempts the student from actually reading them. This sort of vertigo of accumulation, a neocapitalism of information, happens to many.” Many of us suffer from an accelerated version of this nowadays, as we effortlessly bookmark links or save articles to Instapaper, satisfied with our aspiration to hoard all this new information, unsure if we will ever get around to actually dealing with it. (Eco’s not-entirely-helpful solution: read everything as soon as possible.)

But the most alluring aspect of Eco’s book is the way he imagines the community that results from any honest intellectual endeavor—the conversations you enter into across time and space, across age or hierarchy, in the spirit of free-flowing, democratic conversation. He cautions students against losing themselves down a narcissistic rabbit hole: you are not a “defrauded genius” simply because someone else has happened upon the same set of research questions. “You must overcome any shyness and have a conversation with the librarian,” he writes, “because he can offer you reliable advice that will save you much time. You must consider that the librarian (if not overworked or neurotic) is happy when he can demonstrate two things: the quality of his memory and erudition and the richness of his library, especially if it is small. The more isolated and disregarded the library, the more the librarian is consumed with sorrow for its underestimation.”

Eco captures a basic set of experiences and anxieties familiar to anyone who has written a thesis, from finding a mentor (“How to Avoid Being Exploited By Your Advisor”) to fighting through episodes of self-doubt. Ultimately, it’s the process and struggle that make a thesis a formative experience. When everything else you learned in college is marooned in the past—when you happen upon an old notebook and wonder what you spent all your time doing, since you have no recollection whatsoever of a senior-year postmodernism seminar—it is the thesis that remains, providing the once-mastered scholarly foundation that continues to authorize, decades-later, barroom observations about the late-career works of William Faulker or the Hotelling effect. (Full disclosure: I doubt that anyone on Earth can rival my mastery of John Travolta’s White Man’s Burden, owing to an idyllic Berkeley spring spent studying awful movies about race.)

In his foreword to Eco’s book, the scholar Francesco Erspamer contends that “How to Write a Thesis” continues to resonate with readers because it gets at “the very essence of the humanities.” There are certainly reasons to believe that the current crisis of the humanities owes partly to the poor job they do of explaining and justifying themselves. As critics continue to assail the prohibitive cost and possible uselessness of college—and at a time when anything that takes more than a few minutes to skim is called a “longread”—it’s understandable that devoting a small chunk of one’s frisky twenties to writing a thesis can seem a waste of time, outlandishly quaint, maybe even selfish. And, as higher education continues to bend to the logic of consumption and marketable skills, platitudes about pursuing knowledge for its own sake can seem certifiably bananas. Even from the perspective of the collegiate bureaucracy, the thesis is useful primarily as another mode of assessment, a benchmark of student achievement that’s legible and quantifiable. It’s also a great parting reminder to parents that your senior learned and achieved something.

But “How to Write a Thesis” is ultimately about much more than the leisurely pursuits of college students. Writing and research manuals such as “The Elements of Style,” “The Craft of Research,” and Turabian offer a vision of our best selves. They are exacting and exhaustive, full of protocols and standards that might seem pretentious, even strange. Acknowledging these rules, Eco would argue, allows the average person entry into a veritable universe of argument and discussion. “How to Write a Thesis,” then, isn’t just about fulfilling a degree requirement. It’s also about engaging difference and attempting a project that is seemingly impossible, humbly reckoning with “the knowledge that anyone can teach us something.” It models a kind of self-actualization, a belief in the integrity of one’s own voice.

A thesis represents an investment with an uncertain return, mostly because its life-changing aspects have to do with process. Maybe it’s the last time your most harebrained ideas will be taken seriously. Everyone deserves to feel this way. This is especially true given the stories from many college campuses about the comparatively lower number of women, first-generation students, and students of color who pursue optional thesis work. For these students, part of the challenge involves taking oneself seriously enough to ask for an unfamiliar and potentially path-altering kind of mentorship.

It’s worth thinking through Eco’s evocation of a “just society.” We might even think of the thesis, as Eco envisions it, as a formal version of the open-mindedness, care, rigor, and gusto with which we should greet every new day. It’s about committing oneself to a task that seems big and impossible. In the end, you won’t remember much beyond those final all-nighters, the gauche inside joke that sullies an acknowledgments page that only four human beings will ever read, the awkward photograph with your advisor at graduation. All that remains might be the sensation of handing your thesis to someone in the departmental office and then walking into a possibility-rich, almost-summer afternoon. It will be difficult to forget.

Books & Fiction

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Mary Norris

By Joshua Rothman

By Adam Iscoe

By Louisa Thomas

How to Write a Better Thesis

- © 2014

- Latest edition

- David Evans 0 ,

- Paul Gruba 1 ,

- Justin Zobel 2

(deceased) University of Melbourne, Carlton, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

School of Languages and Linguistics, University of Melbourne, Carlton, Australia

Computing & Information Systems, University of Melbourne, Carlton, Australia

- Offers a step-by-step guide on the mechanics of thesis writing

- Illustrates the complete process of how to structure a thesis by providing specific examples

- Equips readers to understand how to conceptualize and approach the problems of producing a thesis

- Written by authors with over 20 years experience of supervising and advising students

- Includes supplementary material: sn.pub/extras

287k Accesses

14 Citations

744 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

About this book

From proposal to examination, producing a dissertation or thesis is a challenge. Grounded in decades of experience with research training and supervision, this fully updated and revised edition takes an integrated, down-to-earth approach drawing on case studies and examples to guide you step-by-step towards productive success.

Early chapters frame the tasks ahead and show you how to get started. From there, practical advice and illustrations take you through the elements of formulating research questions, working with software, and purposeful writing of each of the different kinds of chapters, and finishes with a focus on revision, dissemination and deadlines. How to Write a Better Thesis presents a cohesive approach to research that will help you succeed.

Similar content being viewed by others

How to Write a Protocol

Commentaries on retrospect and prospects for IS research

Writing case studies in information systems research

- Dissertation writing

- Mechanics of writing

- Research writing

- Thesis structure

- Thesis writing

- learning and instruction

Table of contents (12 chapters)

Front matter, what is a thesis.

- David Evans†, Paul Gruba, Justin Zobel

Thesis Structure

Mechanics of writing, making a strong start, the introductory chapter, background chapters, establishing your contribution, outcomes and results, the discussion or interpretation, the conclusion, before you submit, beyond the thesis, back matter.

From the book reviews:

"I have been using this book whilst writing my thesis and I want to express my sincere thanks to the authors as it has provided me with an excellent source of guidance and has made my life a lot easier over the past five months. I've recommended this book to a number of other PhD students and hope you continue to publish further editions as I found it to be an extremely valuable resource." (Chris De Gruyter, PhD Candidate at Monash University, Australia, March 2015)

Authors and Affiliations

David Evans

Computing & Information Systems, University of Melbourne, Carlton, Australia

Justin Zobel

About the authors

David Evans was Reader and Associate Professor in the Faculty of Architecture Building and Planning, University of Melbourne.

Paul Gruba is Senior Lecturer in the School of Languages and Linguistics, University of Melbourne.

Justin Zobel is Professor in the Department of Computing and Information Systems, University of Melbourne.

Bibliographic Information

Book Title : How to Write a Better Thesis

Authors : David Evans, Paul Gruba, Justin Zobel

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04286-2

Publisher : Springer Cham

eBook Packages : Computer Science , Computer Science (R0)

Copyright Information : Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-319-04285-5 Published: 08 April 2014

eBook ISBN : 978-3-319-04286-2 Published: 26 March 2014

Edition Number : 3

Number of Pages : XIV, 167

Number of Illustrations : 2 b/w illustrations

Topics : Computer Science, general , Learning & Instruction , Natural Language Processing (NLP) , Popular Science, general , Science, Humanities and Social Sciences, multidisciplinary

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

What is a thesis | A Complete Guide with Examples

Table of Contents

A thesis is a comprehensive academic paper based on your original research that presents new findings, arguments, and ideas of your study. It’s typically submitted at the end of your master’s degree or as a capstone of your bachelor’s degree.

However, writing a thesis can be laborious, especially for beginners. From the initial challenge of pinpointing a compelling research topic to organizing and presenting findings, the process is filled with potential pitfalls.

Therefore, to help you, this guide talks about what is a thesis. Additionally, it offers revelations and methodologies to transform it from an overwhelming task to a manageable and rewarding academic milestone.

What is a thesis?

A thesis is an in-depth research study that identifies a particular topic of inquiry and presents a clear argument or perspective about that topic using evidence and logic.

Writing a thesis showcases your ability of critical thinking, gathering evidence, and making a compelling argument. Integral to these competencies is thorough research, which not only fortifies your propositions but also confers credibility to your entire study.

Furthermore, there's another phenomenon you might often confuse with the thesis: the ' working thesis .' However, they aren't similar and shouldn't be used interchangeably.

A working thesis, often referred to as a preliminary or tentative thesis, is an initial version of your thesis statement. It serves as a draft or a starting point that guides your research in its early stages.

As you research more and gather more evidence, your initial thesis (aka working thesis) might change. It's like a starting point that can be adjusted as you learn more. It's normal for your main topic to change a few times before you finalize it.

While a thesis identifies and provides an overarching argument, the key to clearly communicating the central point of that argument lies in writing a strong thesis statement.

What is a thesis statement?

A strong thesis statement (aka thesis sentence) is a concise summary of the main argument or claim of the paper. It serves as a critical anchor in any academic work, succinctly encapsulating the primary argument or main idea of the entire paper.

Typically found within the introductory section, a strong thesis statement acts as a roadmap of your thesis, directing readers through your arguments and findings. By delineating the core focus of your investigation, it offers readers an immediate understanding of the context and the gravity of your study.

Furthermore, an effectively crafted thesis statement can set forth the boundaries of your research, helping readers anticipate the specific areas of inquiry you are addressing.

Different types of thesis statements

A good thesis statement is clear, specific, and arguable. Therefore, it is necessary for you to choose the right type of thesis statement for your academic papers.

Thesis statements can be classified based on their purpose and structure. Here are the primary types of thesis statements:

Argumentative (or Persuasive) thesis statement

Purpose : To convince the reader of a particular stance or point of view by presenting evidence and formulating a compelling argument.

Example : Reducing plastic use in daily life is essential for environmental health.

Analytical thesis statement

Purpose : To break down an idea or issue into its components and evaluate it.

Example : By examining the long-term effects, social implications, and economic impact of climate change, it becomes evident that immediate global action is necessary.

Expository (or Descriptive) thesis statement

Purpose : To explain a topic or subject to the reader.

Example : The Great Depression, spanning the 1930s, was a severe worldwide economic downturn triggered by a stock market crash, bank failures, and reduced consumer spending.

Cause and effect thesis statement

Purpose : To demonstrate a cause and its resulting effect.

Example : Overuse of smartphones can lead to impaired sleep patterns, reduced face-to-face social interactions, and increased levels of anxiety.

Compare and contrast thesis statement

Purpose : To highlight similarities and differences between two subjects.

Example : "While both novels '1984' and 'Brave New World' delve into dystopian futures, they differ in their portrayal of individual freedom, societal control, and the role of technology."

When you write a thesis statement , it's important to ensure clarity and precision, so the reader immediately understands the central focus of your work.

What is the difference between a thesis and a thesis statement?

While both terms are frequently used interchangeably, they have distinct meanings.

A thesis refers to the entire research document, encompassing all its chapters and sections. In contrast, a thesis statement is a brief assertion that encapsulates the central argument of the research.

Here’s an in-depth differentiation table of a thesis and a thesis statement.

Aspect | Thesis | Thesis Statement |

Definition | An extensive document presenting the author's research and findings, typically for a degree or professional qualification. | A concise sentence or two in an essay or research paper that outlines the main idea or argument. |

Position | It’s the entire document on its own. | Typically found at the end of the introduction of an essay, research paper, or thesis. |

Components | Introduction, methodology, results, conclusions, and bibliography or references. | Doesn't include any specific components |

Purpose | Provides detailed research, presents findings, and contributes to a field of study. | To guide the reader about the main point or argument of the paper or essay. |

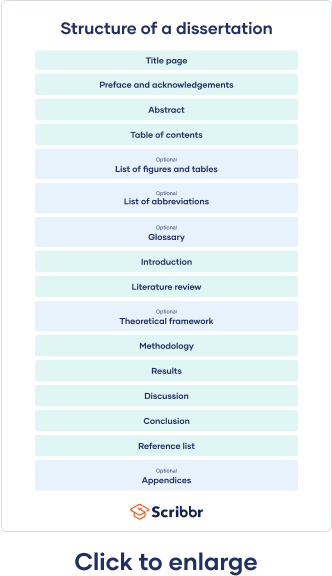

Now, to craft a compelling thesis, it's crucial to adhere to a specific structure. Let’s break down these essential components that make up a thesis structure

15 components of a thesis structure

Navigating a thesis can be daunting. However, understanding its structure can make the process more manageable.

Here are the key components or different sections of a thesis structure:

Your thesis begins with the title page. It's not just a formality but the gateway to your research.

Here, you'll prominently display the necessary information about you (the author) and your institutional details.

- Title of your thesis

- Your full name

- Your department

- Your institution and degree program

- Your submission date

- Your Supervisor's name (in some cases)

- Your Department or faculty (in some cases)

- Your University's logo (in some cases)

- Your Student ID (in some cases)

In a concise manner, you'll have to summarize the critical aspects of your research in typically no more than 200-300 words.

This includes the problem statement, methodology, key findings, and conclusions. For many, the abstract will determine if they delve deeper into your work, so ensure it's clear and compelling.

Acknowledgments

Research is rarely a solitary endeavor. In the acknowledgments section, you have the chance to express gratitude to those who've supported your journey.

This might include advisors, peers, institutions, or even personal sources of inspiration and support. It's a personal touch, reflecting the humanity behind the academic rigor.

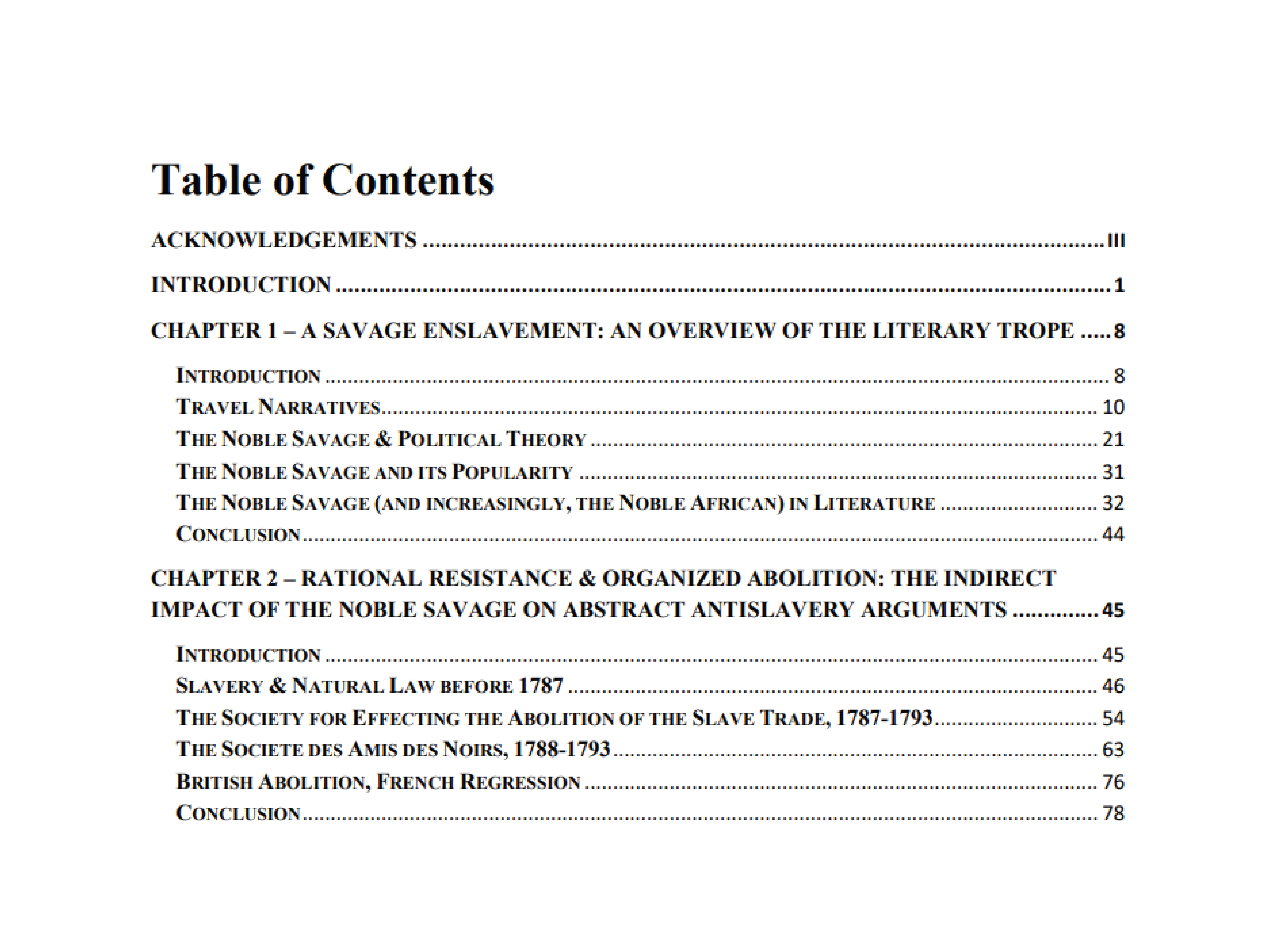

Table of contents

A roadmap for your readers, the table of contents lists the chapters, sections, and subsections of your thesis.

By providing page numbers, you allow readers to navigate your work easily, jumping to sections that pique their interest.

List of figures and tables

Research often involves data, and presenting this data visually can enhance understanding. This section provides an organized listing of all figures and tables in your thesis.

It's a visual index, ensuring that readers can quickly locate and reference your graphical data.

Introduction

Here's where you introduce your research topic, articulate the research question or objective, and outline the significance of your study.

- Present the research topic : Clearly articulate the central theme or subject of your research.

- Background information : Ground your research topic, providing any necessary context or background information your readers might need to understand the significance of your study.

- Define the scope : Clearly delineate the boundaries of your research, indicating what will and won't be covered.

- Literature review : Introduce any relevant existing research on your topic, situating your work within the broader academic conversation and highlighting where your research fits in.

- State the research Question(s) or objective(s) : Clearly articulate the primary questions or objectives your research aims to address.

- Outline the study's structure : Give a brief overview of how the subsequent sections of your work will unfold, guiding your readers through the journey ahead.

The introduction should captivate your readers, making them eager to delve deeper into your research journey.

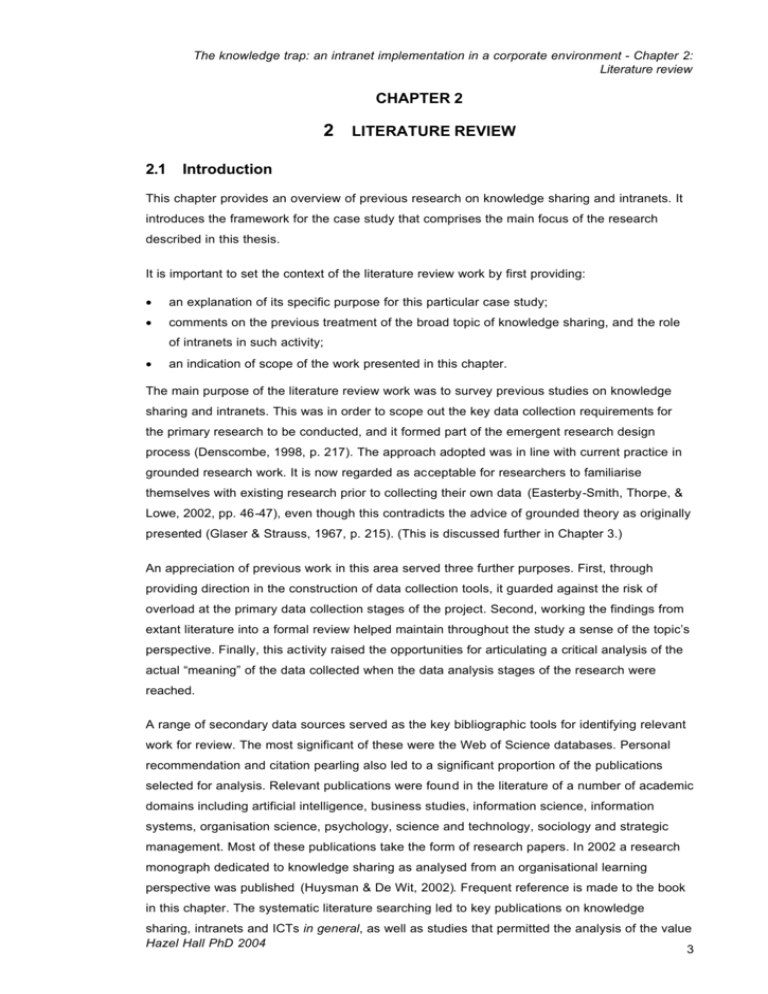

Literature review section

Your study correlates with existing research. Therefore, in the literature review section, you'll engage in a dialogue with existing knowledge, highlighting relevant studies, theories, and findings.

It's here that you identify gaps in the current knowledge, positioning your research as a bridge to new insights.

To streamline this process, consider leveraging AI tools. For example, the SciSpace literature review tool enables you to efficiently explore and delve into research papers, simplifying your literature review journey.

Methodology

In the research methodology section, you’ll detail the tools, techniques, and processes you employed to gather and analyze data. This section will inform the readers about how you approached your research questions and ensures the reproducibility of your study.

Here's a breakdown of what it should encompass:

- Research Design : Describe the overall structure and approach of your research. Are you conducting a qualitative study with in-depth interviews? Or is it a quantitative study using statistical analysis? Perhaps it's a mixed-methods approach?

- Data Collection : Detail the methods you used to gather data. This could include surveys, experiments, observations, interviews, archival research, etc. Mention where you sourced your data, the duration of data collection, and any tools or instruments used.

- Sampling : If applicable, explain how you selected participants or data sources for your study. Discuss the size of your sample and the rationale behind choosing it.

- Data Analysis : Describe the techniques and tools you used to process and analyze the data. This could range from statistical tests in quantitative research to thematic analysis in qualitative research.

- Validity and Reliability : Address the steps you took to ensure the validity and reliability of your findings to ensure that your results are both accurate and consistent.

- Ethical Considerations : Highlight any ethical issues related to your research and the measures you took to address them, including — informed consent, confidentiality, and data storage and protection measures.

Moreover, different research questions necessitate different types of methodologies. For instance:

- Experimental methodology : Often used in sciences, this involves a controlled experiment to discern causality.

- Qualitative methodology : Employed when exploring patterns or phenomena without numerical data. Methods can include interviews, focus groups, or content analysis.

- Quantitative methodology : Concerned with measurable data and often involves statistical analysis. Surveys and structured observations are common tools here.

- Mixed methods : As the name implies, this combines both qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

The Methodology section isn’t just about detailing the methods but also justifying why they were chosen. The appropriateness of the methods in addressing your research question can significantly impact the credibility of your findings.

Results (or Findings)

This section presents the outcomes of your research. It's crucial to note that the nature of your results may vary; they could be quantitative, qualitative, or a mix of both.

Quantitative results often present statistical data, showcasing measurable outcomes, and they benefit from tables, graphs, and figures to depict these data points.

Qualitative results , on the other hand, might delve into patterns, themes, or narratives derived from non-numerical data, such as interviews or observations.

Regardless of the nature of your results, clarity is essential. This section is purely about presenting the data without offering interpretations — that comes later in the discussion.

In the discussion section, the raw data transforms into valuable insights.

Start by revisiting your research question and contrast it with the findings. How do your results expand, constrict, or challenge current academic conversations?

Dive into the intricacies of the data, guiding the reader through its implications. Detail potential limitations transparently, signaling your awareness of the research's boundaries. This is where your academic voice should be resonant and confident.

Practical implications (Recommendation) section

Based on the insights derived from your research, this section provides actionable suggestions or proposed solutions.

Whether aimed at industry professionals or the general public, recommendations translate your academic findings into potential real-world actions. They help readers understand the practical implications of your work and how it can be applied to effect change or improvement in a given field.

When crafting recommendations, it's essential to ensure they're feasible and rooted in the evidence provided by your research. They shouldn't merely be aspirational but should offer a clear path forward, grounded in your findings.

The conclusion provides closure to your research narrative.

It's not merely a recap but a synthesis of your main findings and their broader implications. Reconnect with the research questions or hypotheses posited at the beginning, offering clear answers based on your findings.

Reflect on the broader contributions of your study, considering its impact on the academic community and potential real-world applications.

Lastly, the conclusion should leave your readers with a clear understanding of the value and impact of your study.

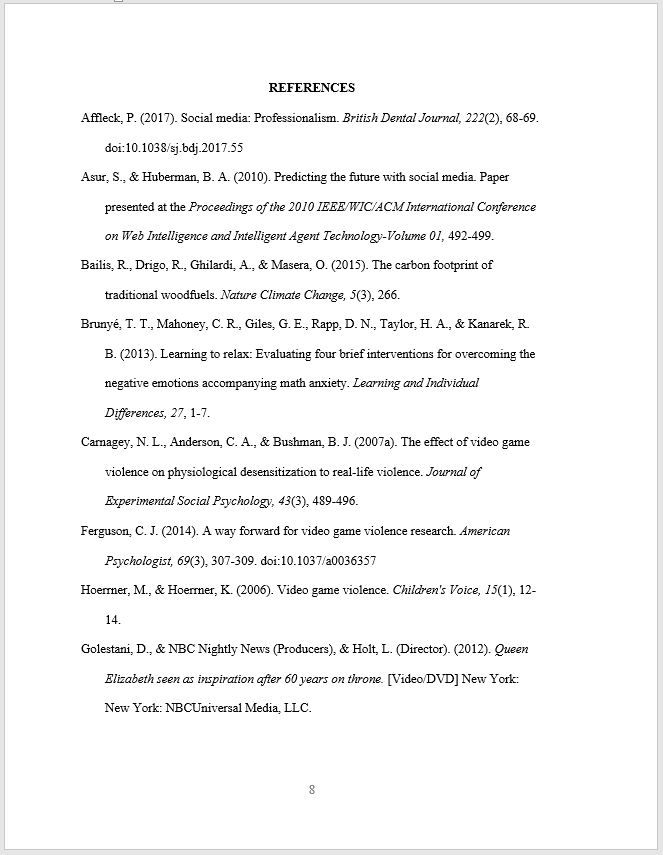

References (or Bibliography)

Every theory you've expounded upon, every data point you've cited, and every methodological precedent you've followed finds its acknowledgment here.

In references, it's crucial to ensure meticulous consistency in formatting, mirroring the specific guidelines of the chosen citation style .

Proper referencing helps to avoid plagiarism , gives credit to original ideas, and allows readers to explore topics of interest. Moreover, it situates your work within the continuum of academic knowledge.

To properly cite the sources used in the study, you can rely on online citation generator tools to generate accurate citations!

Here’s more on how you can cite your sources.

Often, the depth of research produces a wealth of material that, while crucial, can make the core content of the thesis cumbersome. The appendix is where you mention extra information that supports your research but isn't central to the main text.

Whether it's raw datasets, detailed procedural methodologies, extended case studies, or any other ancillary material, the appendices ensure that these elements are archived for reference without breaking the main narrative's flow.

For thorough researchers and readers keen on meticulous details, the appendices provide a treasure trove of insights.

Glossary (optional)

In academics, specialized terminologies, and jargon are inevitable. However, not every reader is versed in every term.

The glossary, while optional, is a critical tool for accessibility. It's a bridge ensuring that even readers from outside the discipline can access, understand, and appreciate your work.

By defining complex terms and providing context, you're inviting a wider audience to engage with your research, enhancing its reach and impact.

Remember, while these components provide a structured framework, the essence of your thesis lies in the originality of your ideas, the rigor of your research, and the clarity of your presentation.

As you craft each section, keep your readers in mind, ensuring that your passion and dedication shine through every page.

Thesis examples

To further elucidate the concept of a thesis, here are illustrative examples from various fields:

Example 1 (History): Abolition, Africans, and Abstraction: the Influence of the ‘Noble Savage’ on British and French Antislavery Thought, 1787-1807 by Suchait Kahlon.

Example 2 (Climate Dynamics): Influence of external forcings on abrupt millennial-scale climate changes: a statistical modelling study by Takahito Mitsui · Michel Crucifix

Checklist for your thesis evaluation

Evaluating your thesis ensures that your research meets the standards of academia. Here's an elaborate checklist to guide you through this critical process.

Content and structure

- Is the thesis statement clear, concise, and debatable?

- Does the introduction provide sufficient background and context?

- Is the literature review comprehensive, relevant, and well-organized?

- Does the methodology section clearly describe and justify the research methods?

- Are the results/findings presented clearly and logically?

- Does the discussion interpret the results in light of the research question and existing literature?

- Is the conclusion summarizing the research and suggesting future directions or implications?

Clarity and coherence

- Is the writing clear and free of jargon?

- Are ideas and sections logically connected and flowing?

- Is there a clear narrative or argument throughout the thesis?

Research quality

- Is the research question significant and relevant?

- Are the research methods appropriate for the question?

- Is the sample size (if applicable) adequate?

- Are the data analysis techniques appropriate and correctly applied?

- Are potential biases or limitations addressed?

Originality and significance

- Does the thesis contribute new knowledge or insights to the field?

- Is the research grounded in existing literature while offering fresh perspectives?

Formatting and presentation

- Is the thesis formatted according to institutional guidelines?

- Are figures, tables, and charts clear, labeled, and referenced in the text?

- Is the bibliography or reference list complete and consistently formatted?

- Are appendices relevant and appropriately referenced in the main text?

Grammar and language

- Is the thesis free of grammatical and spelling errors?

- Is the language professional, consistent, and appropriate for an academic audience?

- Are quotations and paraphrased material correctly cited?

Feedback and revision

- Have you sought feedback from peers, advisors, or experts in the field?

- Have you addressed the feedback and made the necessary revisions?

Overall assessment

- Does the thesis as a whole feel cohesive and comprehensive?

- Would the thesis be understandable and valuable to someone in your field?

Ensure to use this checklist to leave no ground for doubt or missed information in your thesis.

After writing your thesis, the next step is to discuss and defend your findings verbally in front of a knowledgeable panel. You’ve to be well prepared as your professors may grade your presentation abilities.

Preparing your thesis defense

A thesis defense, also known as "defending the thesis," is the culmination of a scholar's research journey. It's the final frontier, where you’ll present their findings and face scrutiny from a panel of experts.

Typically, the defense involves a public presentation where you’ll have to outline your study, followed by a question-and-answer session with a committee of experts. This committee assesses the validity, originality, and significance of the research.

The defense serves as a rite of passage for scholars. It's an opportunity to showcase expertise, address criticisms, and refine arguments. A successful defense not only validates the research but also establishes your authority as a researcher in your field.

Here’s how you can effectively prepare for your thesis defense .

Now, having touched upon the process of defending a thesis, it's worth noting that scholarly work can take various forms, depending on academic and regional practices.

One such form, often paralleled with the thesis, is the 'dissertation.' But what differentiates the two?

Dissertation vs. Thesis

Often used interchangeably in casual discourse, they refer to distinct research projects undertaken at different levels of higher education.

To the uninitiated, understanding their meaning might be elusive. So, let's demystify these terms and delve into their core differences.

Here's a table differentiating between the two.

Aspect | Thesis | Dissertation |

Purpose | Often for a master's degree, showcasing a grasp of existing research | Primarily for a doctoral degree, contributing new knowledge to the field |

Length | 100 pages, focusing on a specific topic or question. | 400-500 pages, involving deep research and comprehensive findings |

Research Depth | Builds upon existing research | Involves original and groundbreaking research |

Advisor's Role | Guides the research process | Acts more as a consultant, allowing the student to take the lead |

Outcome | Demonstrates understanding of the subject | Proves capability to conduct independent and original research |

Wrapping up

From understanding the foundational concept of a thesis to navigating its various components, differentiating it from a dissertation, and recognizing the importance of proper citation — this guide covers it all.

As scholars and readers, understanding these nuances not only aids in academic pursuits but also fosters a deeper appreciation for the relentless quest for knowledge that drives academia.

It’s important to remember that every thesis is a testament to curiosity, dedication, and the indomitable spirit of discovery.

Good luck with your thesis writing!

Frequently Asked Questions

A thesis typically ranges between 40-80 pages, but its length can vary based on the research topic, institution guidelines, and level of study.

A PhD thesis usually spans 200-300 pages, though this can vary based on the discipline, complexity of the research, and institutional requirements.

To identify a thesis topic, consider current trends in your field, gaps in existing literature, personal interests, and discussions with advisors or mentors. Additionally, reviewing related journals and conference proceedings can provide insights into potential areas of exploration.

The conceptual framework is often situated in the literature review or theoretical framework section of a thesis. It helps set the stage by providing the context, defining key concepts, and explaining the relationships between variables.

A thesis statement should be concise, clear, and specific. It should state the main argument or point of your research. Start by pinpointing the central question or issue your research addresses, then condense that into a single statement, ensuring it reflects the essence of your paper.

You might also like

Boosting Citations: A Comparative Analysis of Graphical Abstract vs. Video Abstract

The Impact of Visual Abstracts on Boosting Citations

Introducing SciSpace’s Citation Booster To Increase Research Visibility

While Sandel argues that pursuing perfection through genetic engineering would decrease our sense of humility, he claims that the sense of solidarity we would lose is also important.

This thesis summarizes several points in Sandel’s argument, but it does not make a claim about how we should understand his argument. A reader who read Sandel’s argument would not also need to read an essay based on this descriptive thesis.

Broad thesis (arguable, but difficult to support with evidence)

Michael Sandel’s arguments about genetic engineering do not take into consideration all the relevant issues.

This is an arguable claim because it would be possible to argue against it by saying that Michael Sandel’s arguments do take all of the relevant issues into consideration. But the claim is too broad. Because the thesis does not specify which “issues” it is focused on—or why it matters if they are considered—readers won’t know what the rest of the essay will argue, and the writer won’t know what to focus on. If there is a particular issue that Sandel does not address, then a more specific version of the thesis would include that issue—hand an explanation of why it is important.

Arguable thesis with analytical claim

While Sandel argues persuasively that our instinct to “remake” (54) ourselves into something ever more perfect is a problem, his belief that we can always draw a line between what is medically necessary and what makes us simply “better than well” (51) is less convincing.

This is an arguable analytical claim. To argue for this claim, the essay writer will need to show how evidence from the article itself points to this interpretation. It’s also a reasonable scope for a thesis because it can be supported with evidence available in the text and is neither too broad nor too narrow.

Arguable thesis with normative claim

Given Sandel’s argument against genetic enhancement, we should not allow parents to decide on using Human Growth Hormone for their children.

This thesis tells us what we should do about a particular issue discussed in Sandel’s article, but it does not tell us how we should understand Sandel’s argument.

Questions to ask about your thesis

- Is the thesis truly arguable? Does it speak to a genuine dilemma in the source, or would most readers automatically agree with it?

- Is the thesis too obvious? Again, would most or all readers agree with it without needing to see your argument?

- Is the thesis complex enough to require a whole essay's worth of argument?

- Is the thesis supportable with evidence from the text rather than with generalizations or outside research?

- Would anyone want to read a paper in which this thesis was developed? That is, can you explain what this paper is adding to our understanding of a problem, question, or topic?

- picture_as_pdf Thesis

The best two books on doing a thesis

I started my PhD at the University of Melbourne in early 2006 and finished in 2009. I did well, collecting the John Grice Award for best thesis in my faculty and coming second for the university medal (dammit!). I attribute this success to two ‘how to’ books in particular: Evans and Gruba’s “How to write a better thesis” and Kamler and Thomson’s “Helping doctoral students write” , both of which recently went into their second edition.

I picked up “How to write a better thesis” from the RMIT campus bookstore in June, 2004. I met this book at a particularly dark time in my first thesis journey. I did my masters by creative practice at RMIT, which meant I made a heap of stuff and then had to write about it. The making bit was fun, but the writing was agony.

My poor supervisors did their best to help me revise draft after draft, but I was terrible at it. Nothing in my previous study in architecture had prepared me for writing a proper essay, let alone a long thesis. I had no idea what one should even look like. What sections should I have? What does each one do? In desperation, I visited the bookstore and “How to write a better thesis” jumped off the rack and into my arms.

I’ll admit, my choice was largely informed by its student friendly price point : at the time it was $21.95, it’s now gone up to around $36. In my opinion that’s a bit steep, given that the average student budget is still as constrained as it was a decade ago, but you do get a lot for your money.

David Evans sadly died some years ago, but Justin Zobel has ably stepped into his shoes for the revision. What I’ve always liked best about this book is the way it breaks the ‘standard thesis’ down into its various components: introduction, literature review, method etc, then treats the problems of each separately. This enables you to use it tactically to ‘spot check’ for problem areas in your thesis.

The new edition of the book has remained essentially the same, but with some useful additions that, I think, better reflect the complexity of the contemporary thesis landscape. It acknowledges a broader spread of difficulties with writing the thesis and includes worked examples which illustrate the various traps students can fall into.

A couple of weeks ago I was sent a review copy of Zobel and Gruba’s new collaboration: “How to write a better Minor Thesis” . This is a stripped down version of the original book, with some minor additions, but designed specifically for masters by course work and honours students who have to write a thesis between 15,000 and 30,000 in length. It’s a brilliant idea as, to my knowledge, there hasn’t been much on the market for these students before. The majority of the book is relevant to the PhD and since it’s only $9.95 on Kindle you might want to start with this instead and upgrade to the more expensive paperback if you think you want more.

My introduction to Barbara Kamler and Pat Thomson’s “Helping doctoral students to write: pedagogies for supervision” was quite different. My colleague at the time, Dr Robyn Barnacle, handed me this book when I was in the first year of my PhD. By that time I was a much more confident writer and I was ready for the more complex writing journey this book offered. And “Helping doctoral students to write” does tackle complicated issues – nominalisation, modality, them/rheme analysis and so on – but not in a complicated way. This is largely because it’s full of practical exercises and suggestions, many of which I use in my workshops (for an example, see this slide deck on treating the zombie thesis ).

Although “Helping doctoral students write” has more of a humanities bent than ‘how to write a thesis’, it steps through a broad range of thesis writing issues with a light touch that never makes you feel bored or frustrated. It argues that the thesis is a genre proposition – an amazingly powerful insight – and the chapter on grammar is simply a work of brilliance.

I’ve given this book to engineers, architects, biologists and musicologists, all of whom have told me it was useful – but I find total beginners react with fear to sub-headings like ‘modality: the goldilocks dilemma’. For that reason I usually save it for students near their final year, especially when they tell me their supervisor doesn’t like their writing, but can’t explain why.

“Helping doctoral students to write” is not explicitly written for PhD students (the authors are in the process of doing one). The new edition is an improvement on the old in many ways and well worth buying again if you happen to own it already. The new edition is around $42, which is ok but I think the Kindle edition is over priced (why do publishers keep doing this when many people like to own both for convenience?). It’s a great book for the advanced student who is prepared to roll up their sleeves and do some serious work. Not only will this work pay dividends, as my award attests, it will stand you in good stead for being a supervisor yourself later on as you will be able to diagnose and treat some of the most common – yet difficult to describe – writing problems.

Pat Thomson, is, of course, the author of the popular ‘Patter’ blog , so you can access her wisdom, for free, on a weekly basis. I should own up to the fact that Pat and I met on Twitter, as many bloggers do, and started to collaborate. I’m still in awe of Pat’s knowledge, experience and good humour. I sometimes pinch myself that we have become friends (in fact, she gave me my new copy of the book when I last visited the UK), but I hope this isn’t the only reason the new edition mentions the Whisperer in one of the chapters (squee!).

If I hadn’t already had deep familiarity with this book before I met Pat I would definitely have to say I have a conflict of interest, but I can hand on my heart tell you I would recommend it anyway. Pat and Barbara have written another, truly fantastic, book “Writing for peer review journals: strategies for getting published” but that’s a review for another time 🙂

Have you read these books? Or any others that you think have significantly helped you on your PhD journey? Love to hear about them in the comments.

Other book reviews on the Whisperer

How to write a lot

BITE: recipes for remarkable research

Study skills for international postgraduates

Doing your dissertation with Microsoft Word

How to fail your Viva

Mapping your thesis

Demystifying dissertation writing

If you have a book you would like us to review, please email me.

Share this:

The Thesis Whisperer is written by Professor Inger Mewburn, director of researcher development at The Australian National University . New posts on the first Wednesday of the month. Subscribe by email below. Visit the About page to find out more about me, my podcasts and books. I'm on most social media platforms as @thesiswhisperer. The best places to talk to me are LinkedIn , Mastodon and Threads.

- Post (607)

- Page (16)

- Product (6)

- Getting things done (259)

- Miscellany (138)

- On Writing (138)

- Your Career (113)

- You and your supervisor (66)

- Writing (48)

- productivity (23)

- consulting (13)

- TWC (13)

- supervision (12)

- 2024 (6)

- 2023 (12)

- 2022 (11)

- 2021 (15)

- 2020 (22)

Whisper to me....

Enter your email address to get posts by email.

Email Address

Sign me up!

- On the reg: a podcast with @jasondowns

- Thesis Whisperer on Facebook

- Thesis Whisperer on Instagram

- Thesis Whisperer on Soundcloud

- Thesis Whisperer on Youtube

- Thesiswhisperer on Mastodon

- Thesiswhisperer page on LinkedIn

- Thesiswhisperer Podcast

- 12,151,804 hits

Discover more from The Thesis Whisperer

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Library Subject Guides

4. writing up your research: books on thesis writing.

- Books on Thesis Writing

- Thesis Formatting (MS Word)

- Referencing

Other Research Support Guides 1. Plan (Design and Discover) your Research >> 2. Find & Manage Research Literature >> 3. Doing the Research >> 5. Publish & Share >> 6. Measure Impact

Your dissertation may be the longest piece of writing you have ever done, but there are ways to approach it that will help to make it less overwhelming.

Write up as you go along. It is much easier to keep track of how your ideas develop and writing helps clarify your thinking. It also saves having to churn out 1000s of words at the end.

You don't have to start with the introduction – start at the chapter that seems the easiest to write – this could be the literature review or methodology, for example.

Alternatively you may prefer to write the introduction first, so you can get your ideas straight. Decide what will suit your ways of working best - then do it.

Think of each chapter as an essay in itself – it should have a clear introduction and conclusion. Use the conclusion to link back to the overall research question.

Think of the main argument of your dissertation as a river, and each chapter is a tributary feeding into this. The individual chapters will contain their own arguments, and go their own way, but they all contribute to the main flow.

Write a chapter, read it and do a redraft - then move on. This stops you from getting bogged down in one chapter.

Write your references properly and in full from the beginning.

Keep your word count in mind – be ruthless and don't write anything that isn't relevant. It's often easier to add information, than have to cut down a long chapter that you've slaved over for hours.

Save your work! Remember to save your work frequently to somewhere you can access it easily. It's a good idea to at least save a copy to a cloud-based service like Google Docs or Dropbox so that you can access it from any computer - if you only save to your own PC, laptop or tablet, you could lose everything if you lose or break your device.

E-books on thesis writing

Who to Contact

Nick scullin, phone: +6433693904, find more books.

Try the following subject headings to search UC library catalogue for books on thesis writing

More books on writing theses

Dissertations, Academic

Dissertations, Academic -- Authorship

Dissertations, Academic -- Handbooks, manuals ,

Academic writing

Academic writing -- Handbooks, manuals ,

Report writing

Technical writing

Remember to save your work in different places

Save your work! Remember to save your work frequently to somewhere you can access it easily. It's a good idea to save your work in at least three places: on your computer, a flash drive and a copy to a cloud-based service like Google Docs or Dropbox .

Save each new file with the date in the file name as different files can get very confusing

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Thesis Formatting (MS Word) >>

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 10:10 AM

- URL: https://canterbury.libguides.com/writingup

Book series

Springer Theses

Recognizing Outstanding Ph.D. Research

About this book series

Aims and Scope

The series “Springer Theses” brings together a selection of the very best Ph.D. theses from around the world and across the physical sciences. Nominated and endorsed by two recognized specialists, each published volume has been selected for its scientific excellence and the high impact of its contents for the pertinent field of research. For greater accessibility to non-specialists, the published versions include an extended introduction, as well as a foreword by the student’s supervisor explaining the special relevance of the work for the field. As a whole, the series will provide a valuable resource both for newcomers to the research fields described, and for other scientists seeking detailed background information on special questions. Finally, it provides an accredited documentation of the valuable contributions made by today’s younger generation of scientists.

Theses may be nominated for publication in this series by heads of department at internationally leading universities or institutes and should fulfill all of the following criteria

- They must be written in good English.

- The topic should fall within the confines of Chemistry, Physics, Earth Sciences, Engineering and related interdisciplinary fields such as Materials, Nanoscience, Chemical Engineering, Complex Systems and Biophysics.

- The work reported in the thesis must represent a significant scientific advance.

- If the thesis includes previously published material, permission to reproduce this must be gained from the respective copyright holder (a maximum 30% of the thesis should be a verbatim reproduction from the author's previous publications).

- They must have been examined and passed during the 12 months prior to nomination.

- Each thesis should include a foreword by the supervisor outlining the significance of its content.

- The theses should have a clearly defined structure including an introduction accessible to new PhD students and scientists not expert in the relevant field.

Book titles in this series

Enhanced microbial and chemical catalysis in bio-electrochemical systems.

- Xian-Wei Liu

- Copyright: 2025

Available Renditions

Low Energy Neutrino-Nucleus Interactions at the Spallation Neutron Source

- Samuel Hedges

- Copyright: 2024

Stochastic Thermodynamic Treatment of Thermal Anisotropy

- Olga Movilla Miangolarra

Noise, Dynamics and Squeezed Light in Quantum Dot and Interband Cascade Lasers

- Shiyuan Zhao

Probing New Physics Beyond the Standard Model

Axions, Flavor, and Neutrinos

- Gioacchino Piazza

Publish with us

Abstracted and indexed in.

- Enroll & Pay

Open Access Theses and Dissertations (OATD)

OATD.org provides open access graduate theses and dissertations published around the world. Metadata (information about the theses) comes from over 1100 colleges, universities, and research institutions. OATD currently indexes 6,654,285 theses and dissertations.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Appl Basic Med Res

- v.12(3); Jul-Sep 2022

Thesis Writing: The T, H, E, S, I, S Approach – Review of the Book

Vijendra devisingh chauhan.

1 Pro Vice Chancellor, Swami Rama Himalayan University, Himalayan Institute of Medical Sciences, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India

2 Professor and Head, Department of Orthopedics, Himalayan Institute of Medical Sciences, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India

Dr. Rajiv Mahajan, Dr. Tejinder Singh, editors. 2022. 1st ed. Jaypee Brothers, Medical Publishers (P) Ltd.354. Rs. 795/-. ISBN: 978-93-5465-131-1.

After a long time, I am seeing a book on thesis writing which would be of a great use for the medical fraternity and especially, the postgraduates (PGs).

I recapitulate my residency days when I did my thesis project. I had no clue from where to begin; I was fortunate to have a good mentor who mentored me but every PG resident is not so lucky. This book will definitely supplement the efforts being made by PG thesis supervisors in guiding the PGs.

After going through the book, it inspired me to write a review. The title of the book is so catchy “THESIS WRITING ‒ the T, H, E, S, I, S. Approach.” It compelled me to peep into the book and explore the acronym ‒ T: Tickling, H: Hologram, E: Expansion, S: Scenarios, I: Improvisation, and S: Summary. I found that every chapter is crafted using this philosophy. The second reason which stimulated me to go through this book is that it has been authored by well-known medical educationists who could appreciate the real need of the PGs of this country.

I have no hesitation in saying that not only fresh PGs but even many of their guides may be ignorant of what constitutes writing/guiding a quality thesis. J. Frank Dobi once said “ The average PhD thesis is nothing but transference of bones from one graveyard to another .” Moreover, this is true even for PG medical thesis produced in this country every year. I quote Prof. Vivek A Saoji, Vice-Chancellor, KLE Academy of Higher Education of Research, Belgaum, Karnataka, who has appropriately mentioned in his foreword of this book, “ Proper guidance and training will go a long way in improving the quality of research the postgraduates do and in turn the quality of thesis .”

Usually, in a multiauthored book, style changes with every chapter. Credit goes to the editors, Dr. Rajiv Mahajan and Dr. Tejinder Singh for keeping the uniform language, writing style, and format for each chapter. Hence, one finds continuity and connectivity between the chapters. The editors have ensured that the reader remains hooked to the book till the end. The flowcharts and boxes have been provided for easy remembrance and recapitulation of the salient features of the chapters. I personally feel that these tables, boxes, and flowcharts must be printed and hanged in the seminar room of the departments. I would suggest authors to prepare a small booklet so that these flowcharts are available to the students in their pockets when they are embarking on their thesis.

The book begins with a chapter on “Role and importance of thesis in PG training.” It talks about the statutory and mandatory requirements of the training and how research and publication can open new vistas and opportunities for a PG student. The author has supplemented the list of funding agencies and the nature of support extended for research. The chapter ends with a beautiful inspiring story of Dr. Althesis, tips for conducting a research – a self-checklist to facilitate writing a PG thesis and tips for writing a high-quality thesis.

Chapter 2 deals with the basic concepts of research. It describes lucidly what makes good research and different types of research, i.e., quantitative, qualitative, basic and applied research, and prominent features of each. The author has nicely depicted commonly employed sampling strategies. Stress has been laid on collecting tools for data collection and establishing ethical considerations. Simple examples of quantitative and qualitative research make things simplified for readers.

Chapter 3 is on research design. I need to congratulate the editors for providing a separate chapter on research design. Yes, this is a big confusion for the teacher as well as for the students. A nice pictorial classification has been provided and each design has been explained in a Lucid language with examples so that the PGs can choose the right design for the thesis. I liked the flowcharts and boxes provided, particularly ‒ criteria to choose research design and ‒ choosing study design. The author has used an analogy to explain certain difficult terminology. It made things so simple, both for teachers as well as students.

Chapter 4 ‒ how to start a research describes the importance of the research problem, how to identify the broad problem, and develop a research question. It reflects on types of research questions and explains beautifully what constitutes a good research question using PICO-T and C-Re FINERS criteria. The author has done a creditable job of explaining the concept of hypothesis and various steps involved in writing a good hypothesis; and has rightly cautioned the readers about the errors in hypothesis testing.

Chapter 5 deals with aims and objectives. I am sure after reading this chapter, the students would be able to frame the aim and objectives for their research with great ease. Every chapter provides you with the scenario for easy and better understanding, followed by tips.

Chapter 6 deals with a review of the literature. This is the most difficult and tedious part of a thesis, but one of the most important parts. The author has demonstrated how to use various commonly used search engines, how to develop strategies for literature search, identify the keywords, and the use of Boolean operators. Emphasis is on how to critically analyze the searched material and write the literature review.

A full chapter has been devoted to writing a synopsis which every PG has to submit within the 1 st semester of the PG program. The chapter on materials and methods (M&M) has been prepared like a recipe in a cookbook. A lot of stress is on how to write M&M. The tips provided are worth remembering.

I have seen students and their mentors frequently rushing to the statistician for the calculation of the sample size. Chapter 9 has touched this subject beautifully. It starts with why we need an adequate sample size for any research. It then goes on to ingrain the recipe of sample size, calculation, effect size, standard deviation, type 1 error, power, direction of the effect, expected attrition, and statistical test and each is explained with examples.

Chapter 10 is on results and inferences; the authors have given very practical tips for the presentation of the results. There are general tips on preparing tables, graphs, pie charts, bar graphs, line graphs, and scatter plots. The authors have nicely described P value and its utility in deriving scientific inferences.

Managing the timeline is a very important aspect in the life of the resident. The resident is busy in clinics, patient care, operation theaters, and teaching and at the same time, he has to conduct a research. Managing time is an art. The editors have devoted a separate chapter on this subject. Concepts of the time management matrix, the Gantt chart, and the backward planning have been adequately explained in this chapter.

Ethics and plagiarism are a buzz word now. A separate chapter has been devoted to cover various ethical aspects involved in thesis writing and publications. The authors have discussed in detail about autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, justice, informed consent, the consent process and plagiarism, and how to avoid plagiarism. I am happy to note the topic of plagiarism has been touched and the penalties described by University Grant Commission have been included. Tools to be used for detection have been mentioned. In fact, without a plagiarism check, thesis should not be submitted. A small mention about the availability of various platforms for uploading thesis could have been added. A checklist to avoid plagiarism is appreciated.

A student of medicine is afraid of “biostatistics” and always confused which test needs to be used for his thesis. The authors have provided a nice table on how to choose the appropriate statistical tests. The authors have nicely defined various variables, data collection, data entry and cleaning, assessing the distribution of data, approach to data analysis, and application of post hoc tests. A separate chapter has been devoted to IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, IBM Corp. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) for data validation and analysis and how to make good use of this tool.

Compilation of thesis is very important. Majority of the universities provide templates of the title page and the certificates to be annexed. The authors have lucidly and in a systematic manner described what needs to be done under each heading. They also discussed about research and ethics committee approval letters, pro forma of study, consent forms, master charts, photos, permission letter from other institution if applicable, conflict of interest form (for funded projects), disclosure of the source of funding (if applicable), Gantt chart, certificate of clinical trials registry-India registration (if applicable), and above all are very useful tips for writing the thesis draft and binding of thesis document.

Handling revision is a big issue. The movement the student hears this, he becomes disturbed. The authors have nicely discussed about the reasons for thesis revisions in a tabular form. I liked the tables ‒ how to communicate to the examiners after making revisions. The authors also provided useful tips for preventing rejection and revisions.

Chapters 18 and 19 talk about disseminating thesis research through quality poster and publication of the paper. These two chapters are very practical chapters and I am sure the students would definitely be benefited. I am sure if these practical tips are followed, we would see quality posters and publications from our PGs. A separate chapter devoted to a manuscript-based thesis introduces the readers to a different approach of thesis writing – like a manuscript.

The book ends with chapters on translation education research. It talks about how a student can place his research into “a knowledge to action cycle” and how can PG students strive to achieve translation of their research to standard practice.

All good medical institutions in the country are running 2–3 days’ workshop on research methodology. I think if we can design these workshops based on the basic principles illustrated in this book, it would ensure consistency in the research component in the PG curriculum and second, things would become easy for students to comprehend.

I would like to end with the quote of Mortimer J. Adler: “ In the case of good books, the point is not to see how many of them you can get through, but rather how many can get through to you.” Yes, “Thesis Writing: The T, H, E, S, I, S Approach” gets through to you and I am sure it would inspire you to revisit it again and again.

MIT Libraries logo MIT Libraries

Thesis content and article publishing

Journal publishers usually acquire the copyright to scholarly articles through a publication agreement with the author. Their policies then determine what authors can do with their work.

Below are publisher policies regarding graduate students’ reuse of their previously published articles in their theses, and policies on accepting journal submissions that first appeared in an author’s previously released thesis.

If an article is co-authored with a member of the MIT faculty, or if you have opted-in to an OA license , the MIT open access policy is likely to apply to the article, which allows for the extension of additional rights to graduate student authors through MIT for reuse. Short excerpts of published works may also be available for reuse under the MIT Libraries license agreements .

See this page for information about who owns the copyright to your thesis (generally, it’s either MIT or you).

Please contact Ask Scholarly Communications with questions or if you need information that does not yet appear below.

American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS)

Reuse of author’s previously published article in author’s thesis

Check the terms of your publication agreement .

Submission of new article by author that first appeared as part of author’s thesis

Allows : “ We do not regard dissertations/theses as prior publications.”

American Chemical Society

Allows : “Authors may reuse all or part of the Submitted, Accepted or Published Work in a thesis or dissertation that the author writes and is required to submit to satisfy the criteria of degree-granting institutions…. Appropriate citation of the Published Work must be made as follows “Reprinted with permission from [COMPLETE REFERENCE CITATION]. Copyright [YEAR] American Chemical Society.”

“If the thesis or dissertation to be published is in electronic format, a direct link to the Published Work must be included using the ACS Articles on Request link.”

See also this FAQ for thesis info.

Each ACS journal has a specific policy on prior publication that is determined by the respective ACS Editor-in-Chief. Authors should consult these policies and/or contact the appropriate journal editorial office to ensure they understand the policy before submitting material for consideration.

American Geophysical Union

Allows : “If you wish to reuse your own article (or an amended version of it) in a new publication of which you are the author, editor or co-editor, prior permission is not required (with the usual acknowledgements). However, a formal grant of license can be downloaded free of charge from RightsLink by selecting “Author of this Wiley article” as your requestor type.”

Allows : “Previously published explicitly does not include oral or poster presentations, meeting abstracts or student theses/dissertations.”

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Allows : “ Upon publication of an article or paper in an AIAA journal or conference proceeding, authors can use in their own theses/dissertations (with permission of AIAA if required by copyright).”

From here : “In most cases when AIAA is the copyright holder of a work, authors will be automatically granted permission by AIAA to reprint their own material in subsequent works, to include figures, tables, and verbatim portions of text, upon request. Explicit permission should be sought from AIAA through Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) ; all reprinted material must be acknowledged and the original source cited in full.”

American Institute of Physics

Allows : “A uthors do not need permission from AIP Publishing to reuse your own AIP Publishing article in your thesis or dissertation (please format your credit line: “Reproduced from [FULL CITATION], with the permission of AIP Publishing”)” Author agreement says the version of record can be used .

Allows : Publishing the work in a thesis is not considered prior publication according to author warranties in the publication agreement.

American Meteorological Society

AMS seems to require permission. Email [email protected] . It can take 10 days to hear back. They will then ask that you include the complete bibliographic citation of the original source, as well as the following statement with that citation for each: © American Meteorological Society. Used with permission.

American Physical Society

Allows , “ provided the bibliographic citation and the APS copyright credit line are given on the appropriate pages.”

Allows Language from Physical Review journals page: “Publication of material in a master’s or doctoral thesis does not preclude publication of that material in the Physical Review journals.”

American Society for Clinical Investigation

After Jan 4, 2022 : “Effective with the January 4, 2022 issue of JCI, authors retain copyright on all articles, which are published with a Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0).”

Prior to Jan 4, 2022 : “ Permission can be obtained via Copyright Clearance Center . Copyright or license information is noted on each article.”

Likely allows : D oesn’t explicitly call out theses but says posting on preprints isn’t prior publication.

Association for Computing Machinery (ACM)

Allows : “Authors can include partial or complete papers of their own (and no fee is expected) in a dissertation as long as citations and DOI pointers to the Versions of Record in the ACM Digital Library are included. Authors can use any portion of their own work in presentations and in the classroom (and no fee is expected).”

Likely allows . Prior publication rules apply to “peer reviewed” publications.

Cambridge University Press

Allows : “Permissions requests are waived if t he author of the work wishes to reproduce a single chapter (not exceeding 20 per cent of their work), journal article or shorter extract in a subsequent work (i.e. with a later publication date) of which he or she is to be the author, co-author or editor.”

Policies set by individual journals.

Allows : “ Use and share their works for scholarly purposes (with full acknowledgement of the original article): Include in a thesis or dissertation (provided this is not published commercially).”

Allows : “ Elsevier does not count publication of an academic thesis as prior publication.”

Emerald Publishing

Allows . Authors should use the submitted version or accepted manuscript version. Use of the final published version is permitted in print, but not electronic versions of theses.

Allows : “We are happy for submissions to Emerald to include work that has previously formed part of your PhD or other academic thesis. Please submit your paper in the usual way but declare the existence of the uploaded thesis to the Editor of the journal. If the Editor wished to consider the paper further, the paper would go through our standard anonymised peer-review process.”

Allows , with some requirements

Theses not specifically addressed , but permitted subject to editorial discretion. Individual journals may have their own policies.

Institute of Physics

Allows. A uthor may use the final published version or figures/text, and should include citation and a link to the version of record. “When you transfer the copyright in your article to IOP, we grant back to you certain rights, including the right to include all or part of the Final Published Version of the article within any thesis or dissertation.”

Inter-Research Science Center

Reuse of published content is “generally free of charge,” but you must get permission. Email: [email protected]

Not addressed , except to say, “ Permission to re-use any previously published material must have been obtained by the authors from the copyright holders.”

International Speech Communication Association (ISCA) INTERSPEECH conference

Allows , with citation. “ISCA grants each author permission to use the article in that author’s dissertation….”

Mathematical Sciences Publishers

Allows , with citation. “The Author may use part or all of this Work or its image in any future works of his/her/their own.”

Unclear, but the author agreement says , “The Author warrants that the Work has not been published before, in any form except as a preprint.” We suggest asking your editor.

National Academy of Sciences

Allows , with citation. “ PNAS authors do not need to obtain permission in the following cases: …to include their articles as part of their dissertations.”

Not addressed . “ What constitutes prior publication…will be determined on a case-by-case basis.

Allows , with citation. “ Authors have the right to reuse their article’s Version of Record, in whole or in part, in their own thesis.”

Allows . “ Nature Portfolio will consider submissions containing material that has previously formed part of a PhD or other academic thesis which has been published according to the requirements of the institution awarding the qualification.”

Oxford University Press

Journals have their own policies . OUP uses the Copyright Clearance Center for permissions . Contact your editor.

Royal Society of Chemistry

Allows , but says, “ Excerpts or material from your dissertation that have not been through peer review will generally be eligible for publication. However, if the excerpt from the dissertation included in your manuscript is the same or substantially the same as any previously published work, the editor may determine that it is not suitable for publication in the journal.”

Allows — in addition, a special agreement with Springer for MIT authors allows for reuse for scholarly and educational purposes.

Policy varies by journal but according to Springer: “There are no overriding ethical issues as long as the dual publication is transparent and cross referenced. Transparency is key, though a few journals might reject such an article for the reason of non-originality.”

Taylor & Francis

Allows — authors retain the right to “Include your article Author’s Original Manuscript (AOM) or Accepted Manuscript(AM), depending on the embargo period, in your thesis or dissertation. The Version of Record cannot be used.”