- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

BanksandBanking →

No results found in working knowledge.

- Were any results found in one of the other content buckets on the left?

- Try removing some search filters.

- Use different search filters.

Please update your browser .

- History of Our Firm

- Art Collection

- Our Leadership

- CEO Letters

- Overview Opens Supplier Overview page

- Diversity Opens Supplier Diversity page

- Gold Suppliers Opens Gold Suppliers page

- Contingent Workers Opens Contingent Workers page

- Guidelines & Documents Opens Guidelines & Documents page

- FAQs Opens Faqs page

Our Business

- Morgan Health

- Business Principles

- Media Contacts

- Historical Prime Rate

- Human Rights

Our Culture

- Employee Programs

- Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

- Awards & Recognition

- Governance Principles

- Board of Directors and Board Committees

- Code of Conduct & Ethics

- Policy Engagement & Political Participation

- ESG Information

- COVID-19 Response

- Racial Equity

Our Approach

- Jobs and Skills

- Small Business Expansion

- Neighborhood Development

- Financial Health

- PolicyCenter

- Impact Finance

Communities

- Advancing Cities

- Our Markets

- Advancing Black Pathways : Advancing Black Pathways

- Advancing Hispanics & Latinos :Advancing Hispanics & Latinos

- Asian & Pacific Islander :Asian & Pacific Islander

- Disability Inclusion : Disability Inclusion

- LGBTQ+ : LGBT+

- Military and Veterans :Military and Veterans

- Skilled Volunteerism

- Spotlight Stories

- Women on the Move : Women on the Move

- Be[Series] Be Series

Sustainability

- Our Initiatives

- Stakeholder & Policy Engagement

The changing demographics of retail investors

Household Income & Spending

Small Business

Household Debt

- Cities & Local Communities

Financial Markets

Labor Markets

- COVID-19 :opens link

- Data Privacy Protocols

News & Events

- Expert Insights for the Public Good Accessible Text

- Research Accessible Text

Latest Research

2024-05-23T00:00:00.000-05:00

2024-04-25T00:00:00.000-05:00

Household Pulse: Balances through February 2024

2024-04-16T00:00:00.000-05:00

Hidden costs of homeownership: Race, income, and lender differences in loan closing costs

2024-04-03T00:00:00.000-05:00

Scaling to $1 Million: How Small Businesses Fare by Owner Race and Gender

2024-04-02T00:00:00.000-05:00

The rise in retail investing: Roles of the economic cycle and income growth

2024-03-27T00:00:00.000-05:00

How did advance Child Tax Credit payments affect households’ 2021 tax year outcomes and spending response?

2024-03-25T00:00:00.000-05:00

Checking in on Real Incomes after February Labor Market Data

2024-02-23T00:00:00.000-05:00

Balancing restarted student loan payments and a mortgage: How will household budgets adapt?

2024-01-25T00:00:00.000-05:00

Household Pulse: Balances through October 2023

2023-11-20T00:00:00.000-05:00

The Purchasing Power of Household Incomes: Worker outcomes through August 2023 by income and race

2023-07-12T00:00:00.000-05:00

Household Pulse: Balances through March 2023

Household Cash Buffer Management from the Great Recession through COVID-19

2023-06-21T00:00:00.000-05:00

Measuring the gap: Refinancing trends and disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic

2023-06-15T00:00:00.000-05:00

Household Pulse & Cash Buffer Management throughout the pandemic

2023-05-26T00:00:00.000-05:00

The potential borrower impact of proposed IDR reforms

JPMorgan Chase Institute Take

2023-05-24T00:00:00.000-05:00

Cash or credit: Small business use of credit cards for cash flow management

Cities and Local Communities

2023-01-31T00:00:00.000-05:00

Downtown Downturn: The Covid Shock to Brick-and-Mortar Retail

2022-12-12T00:00:00.000-05:00

The Dynamics and Demographics of U.S. Household Crypto-Asset Use

2022-11-15T00:00:00.000-05:00

How families used the advanced Child Tax Credit

2022-10-27T00:00:00.000-05:00

The Purchasing Power of Household Incomes from 2019 to 2022

2022-09-13T00:00:00.000-05:00

Household Pulse through June 2022: Gains for most, but not all

Last Updated with June 2022 data

2022-08-31T00:00:00.000-05:00

Who benefits from the 2022 student debt cancellation?

JPMorgan Chase Institute

2022-08-15T00:00:00.000-05:00

Expanding Access to Unemployment Insurance

Spending and Job-Finding Impacts of Expanded Unemployment Benefits

2022-07-26T00:00:00.000-05:00

Credit and the Family: The Economic Consequences of Closing the Credit Gap of US Couples

2022-06-28T00:00:00.000-05:00

Income Driven Repayment: Who needs student loan payment relief?

2022-06-21T00:00:00.000-05:00

Household Pulse: The State of Cash Balances through March 2022

Last Updated with March 2022 data

2022-05-26T00:00:00.000-05:00

Healthcare spending through the Pandemic: the impact of high-cost medical events on household finances

2022-05-19T00:00:00.000-05:00

Racial Income Inequality Dynamics

Big Data Insights from 2013 through COVID-19

2022-05-03T00:00:00.000-05:00

Small business owner liquid wealth at firm startup and exit

2022-04-20T00:00:00.000-05:00

Rising prices for fuel, rent, and food eat into families’ financial gains

2022-04-18T00:00:00.000-05:00

Lessons learned from the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance Program during COVID-19

2022-04-11T00:00:00.000-05:00

Post-COVID Consumer Spending in New York City

2022-03-29T00:00:00.000-05:00

Reading Inflation Expectations from the Treasury Market

Insights from Institutional Investor Trading Activity

2022-03-02T00:00:00.000-05:00

What do Fed rate hikes mean for U.S. households’ financial health?

2022-02-23T00:00:00.000-05:00

Household Pulse: The State of Cash Balances at Year End

Last Updated with December 2021 data

2022-02-17T00:00:00.000-05:00

Will this tax season be a boost or bust?

2021-12-15T00:00:00.000-05:00

Year in Review: 10 Key charts that summarize 2021

2021-12-09T00:00:00.000-05:00

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity?

2021-11-30T00:00:00.000-05:00

The COVID Shock to Online Retail: The persistence of new online shopping habits and implications for the future of cities

2021-11-15T00:00:00.000-05:00

Household Cash Balance Pulse: Family Edition

Last updated with September 2021 data

2021-10-21T00:00:00.000-05:00

How did landlords fare during COVID?

2021-10-18T00:00:00.000-05:00

The Online Platform Economy through the Pandemic

2021-09-21T00:00:00.000-05:00

How did the distribution of income growth change alongside the hot pre-pandemic labor market and recent fiscal stimulus?

2021-09-15T00:00:00.000-05:00

Household Finances Pulse: Cash Balances during COVID-19

Last updated with July 2021 data

2021-08-31T00:00:00.000-05:00

The Governor’s choice: Continue or end expanded unemployment benefits?

2021-08-17T00:00:00.000-05:00

Spending after Job Loss from the Great Recession through COVID-19

The Roles of Financial Health, Race, and Policy

2021-07-29T00:00:00.000-05:00

When unemployment insurance benefits are rolled back

Impacts on job finding and the recipients of the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance Program

2021-06-30T00:00:00.000-05:00

Financial outcomes by race during COVID-19

2021-06-23T00:00:00.000-05:00

Small Business Finances in Illinois during the COVID-19 Pandemic

2021-06-15T00:00:00.000-05:00

The Local Commerce Data Series

2021-05-04T00:00:00.000-05:00

Family cash balances, income, and expenditures trends through 2021

A distributional perspective

2021-04-19T00:00:00.000-05:00

Retail Spending Response to Local Conditions during COVID-19

2021-04-06T00:00:00.000-05:00

Local Commerce Data Series: Pandemic Spending

2021-04-01T00:00:00.000-05:00

Balancing accessibility and fraud prevention in housing assistance

2021-03-17T00:00:00.000-05:00

Who Benefits from Student Debt Cancellation?

2021-03-11T00:00:00.000-05:00

Renters vs. Homeowners

Income and Liquid Asset Trends during COVID-19

2021-03-04T00:00:00.000-05:00

Small business ownership and liquid wealth

2021-02-24T00:00:00.000-05:00

The First 100 Days and Beyond

Data-Driven Policies to Support Inclusive Economic Recovery and Equitable Long-Term Growth

2021-02-10T00:00:00.000-05:00

Unemployment insurance, job search, and spending during the pandemic

2021-01-27T00:00:00.000-05:00

The Paycheck Protection Program

Small Business Balances, Revenues, and Expenses in the Weeks after Loan Disbursement

2021-01-21T00:00:00.000+05:30

The Stock Market and Household Financial Behavior

2020-12-16T00:00:00.000-05:00

Household Cash Balances during COVID-19: A Distributional Perspective

2020-12-15T00:00:00.000-05:00

The New Year’s Cliff: How the Expiration of Unemployment Benefits Will Affect Families

2020-12-02T00:00:00.000-05:00

Tapping Home Equity

Income and Spending Trends Around Cash-Out Refinances and HELOCs

Did Mortgage Forbearance Reach the Right Homeowners?

Income and Liquid Assets Trends for Homeowners during the COVID-19 Pandemic

2020-11-19T00:00:00.000-05:00

Small Business Expenses during COVID-19

Home Advantage? Resident Retail Distances and Small Business Financial Outcomes

2020-10-15T00:00:00.000-05:00

The unemployment benefit boost: Initial trends in spending and saving when the $600 supplement ended

2020-10-01T00:00:00.000-05:00

Student Loan Debt: Who is Paying it Down?

Evidence from administrative banking data, credit bureau student loan data, and public records on race

2020-08-10T00:00:00.000+05:30

Expanded Unemployment Benefits and the Impact of Inaction

2020-07-31T00:00:00.000-05:00

Data Dialogue: The Initial Impact of COVID-19 on Consumer Spending and Local Economies

2020-07-22T00:00:00.000+05:30

Small Business Owner Race, Liquidity, and Survival

Racial Gaps in Small Business Outcomes

2020-07-20T00:00:00.000-04:00

Small Business Financial Outcomes during the COVID-19 Pandemic

2020-07-16T00:00:00.000-05:00

Report Consumption Effects of Unemployment Insurance during the COVID-19 Pandemic

2020-07-15T00:00:00.000-05:00

Consumption Effects of Unemployment Insurance during the COVID-19 Pandemic

2020-07-01T00:00:00.000-05:00

The Early Impact of COVID-19 on Local Commerce Report

Changes in Spend Across Neighborhoods and Online

2020-07-01T00:00:00.000+05:30

Fed watchers now turn their attention to September

2020-06-26T00:00:00.000+05:30

The Housing Wealth Effect in the Post-Great Recession Period

Evidence from Big Data

2020-06-25T00:00:00.000+05:30

Initial Impacts of the Pandemic Reflect that Families Changed their Saving and Spending Behavior

2020-06-24T00:00:00.000+05:30

Small Business Financial Outcomes during the Onset of COVID-19

2020-06-03T00:00:00.000+05:30

Data Dialogue: National Urban League, PolicyLink, and the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies Discuss Racial, Economic, and Social Equity

The Early Impact of COVID-19 on Local Commerce

2020-05-29T00:00:00.000+05:30

Data Dialogue: The Economic Impacts of COVID-19 on Small Business

2020-05-27T00:00:00.000-04:00

The Initial Household Spending Response to COVID-19 Part 2

Evidence from Credit Card Transactions - Part 2

2020-05-20T00:00:00.000-04:00

Tracking Spillovers During the Taper Tantrum

Evidence from Institutional Investor Transactions in Emerging Markets

2020-05-14T00:00:00.000-04:00

The Initial Household Spending Response to COVID-19

Evidence from Credit Card Transactions

2020-05-04T00:00:00.000-04:00

How COVID-19 is impacting local economies and small businesses

A Cash Flow Perspective on the Small Business Sector

2020-04-20T00:00:00.000+05:30

Racial Gaps in Financial Outcomes

Big Data Evidence

2020-04-16T00:00:00.000-04:00

How COVID-19 could widen racial gaps in financial outcomes

2020-04-09T00:00:00.000-04:00

Forbearance for mortgages a short-term solution; savings programs for the long term

2020-04-01T00:00:00.000-04:00

Small Business Cash Liquidity in 25 Metro Areas

2020-03-31T00:00:00.000-05:00

Expanded unemployment insurance may lessen impact of layoffs

JPMorgan Chase Institute take

2020-03-31T00:00:00.000-04:00

Who benefits from a tax-payment deadline extension?

2020-03-24T00:00:00.000-04:00

Coronavirus may impact workers' income volatility

2020-03-20T00:00:00.000-04:00

Quick liquidity to small businesses could mitigate impacts from coronavirus

2020-03-06T00:00:00.000-05:00

Tax Refunds and Household Spending

2020-03-01T00:00:00.000-05:00

The potential economic impacts of COVID-19 on families, small businesses, and communities

Insights from five years of big data research

2019-12-04T00:00:00.000-05:00

Small Business Financial Outcomes in Miami Communities

2019-11-21T00:00:00.000-05:00

The Gender Gap: Exploring Consumer and Small Business Financial Health

2019-11-05T00:00:00.000-05:00

Financial and Physical Health in a Changing Healthcare Market

2019-10-31T00:00:00.000-04:00

Bridging the Gap

How Families Use the Online Platform Economy to Manage their Cash Flow

2019-10-23T00:00:00.000-04:00

Weathering Volatility 2.0

A Monthly Stress Test to Guide Savings

2019-09-30T00:00:00.000-04:00

Place Matters

Small Business Financial Health in Urban Communities

2019-09-26T00:00:00.000-04:00

In Conversation: Experts on Student Loan Payments and JPMC Institute Research

2019-08-12T00:00:00.000-04:00

Facing Uncertainty

Small Business Cash Flow Patterns in 25 U.S. Cities

2019-07-31T00:00:00.000+05:30

Data and Collaboration for Good

The JPMorgan Chase Institute 2nd Annual Conference on Economic Research

2019-07-01T00:00:00.000-04:00

Student Loan Payments

Evidence from 4 Million Families

2019-06-01T00:00:00.000-04:00

Trading Equity for Liquidity

Bank Data on the Relationship Between Liquidity and Mortgage Default

The San Francisco Economy

Household and Small Business Financial Outcomes

2019-05-09T00:00:00.000-04:00

How Data Can Improve the Financial Health of U.S. Small Businesses

2019-05-01T00:00:00.000-04:00

The Small Business Sector in Urban America

Growth and Vitality in 25 Cities

2019-04-01T00:00:00.000-05:00

The Online Platform Economy in 27 Metro Areas

The Experience of Drivers and Lessors

2019-03-22T00:00:00.000-05:00

Technology and the Future of Work

2019-03-01T00:00:00.000-05:00

How Families Manage Tax Refunds and Payments

2019-02-01T00:00:00.000-05:00

Gender, Age, and Small Business Financial Outcomes

2019-01-15T00:00:00.000-05:00

Does the Timing of Central Bank Announcements Matter?

Trade-Level Data on Hedge Fund Behavior Before Swiss National Bank Meetings

2018-12-04T00:00:00.000-05:00

Local Commerce Index

The Local Commerce Index (LCI) is a measure of the monthly year-over-year growth rate of everyday debit and credit card spending by over 64 million de-identified Chase customers across 14 metro areas in the US. The LCI is an alternative view of the health and vibrancy of the US consumer.

Estimating Family Income from Administrative Banking Data

A Machine Learning Approach

2018-12-01T00:00:00.000-05:00

Deferred Care

How Tax Refunds Enable Healthcare Spending

Shopping Near and Far: Local Commerce in the Digital Age

Insights from 4 Billion Transactions across the United States

2018-10-23T00:00:00.000-05:00

Measuring the Online Platform Economy

How Banking and Survey Data Compare

2018-10-01T00:00:00.000-04:00

Falling Behind

Bank Data on the Role of Income and Savings in Mortgage Default

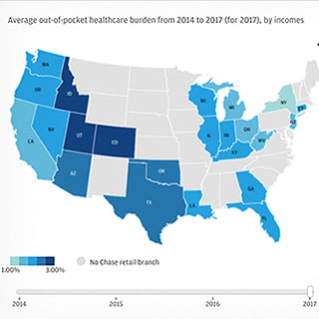

On the Rise

Out-of-Pocket Healthcare Spending in 2017

2018-09-01T00:00:00.000-05:00

The Online Platform Economy in 2018

Drivers, Workers, Sellers, and Lessors

2018-08-29T00:00:00.000-04:00

JPMorgan Chase Institute 2018 Inaugural Conference on Economic Research

2018-07-01T00:00:00.000-04:00

Growth, Vitality, and Cash Flows

High-Frequency Evidence from 1 Million Small Businesses

2018-06-20T00:00:00.000-05:00

Where are all the Contingent Workers?

2018-06-12T00:00:00.000-04:00

FX Markets Move on Surprise News

Institutional Investor Trading Behavior around Brexit, the U.S. Election, and the Swiss Franc Floor

2018-04-01T00:00:00.000-04:00

Filing Taxes Early, Getting Healthcare Late

Insights from 1.2 Million Households

2018-03-15T00:00:00.000-04:00

Healthcare When It’s Needed

How to Mitigate High Costs and Deferred Care

2018-03-01T00:00:00.000-05:00

The Commercial Vibrancy of Chicago Neighborhoods, 2016

2018-02-01T00:00:00.000-05:00

Bend, Don’t Break

Small Business Financial Resilience After Hurricanes Harvey and Irma

Weathering the Storm

The Financial Impacts of Hurricanes Harvey and Irma on One Million Households

Local Consumer Commerce in the Wake of a Hurricane

2017-12-14T00:00:00.000-05:00

Institute Insights for Open Enrollment

2017-12-01T00:00:00.000-05:00

Mortgage Modifications after the Great Recession

New Evidence and Implications for Policy

2017-11-01T00:00:00.000-04:00

Paying a Premium

Dynamics of the Small Business Owner Health Insurance Market

2017-10-10T00:00:00.000-04:00

Younger and Lower Income Consumers Drive Small Business Spending

2017-09-06T00:00:00.000-04:00

Coping with Medical Costs through Life

2017-09-01T00:00:00.000-04:00

Paying Out-of-Pocket

The Healthcare Spending of 2 Million U.S. Families

Mapping Segments in the Small Business Sector

2017-05-01T00:00:00.000-04:00

The Gender Gap in Financial Outcomes

The Impact of Medical Payments

2017-04-20T00:00:00.000-04:00

The Consumer Spending Response to Mortgage Resets

2017-04-01T00:00:00.000-04:00

The Consumer Spending Response to Mortgage Resets Report

Microdata on Monetary Policy

2017-03-17T00:00:00.000-04:00

The Monthly Stress-Test on Family Finances

2017-03-01T00:00:00.000-05:00

Consumption Inequality

What’s in Your Shopping Basket?

Going the Distance

Big Data on Resident Access to Everyday Goods

Seniors Lead the Slowdown in Local Consumer Commerce

2017-02-09T00:00:00.000-05:00

Why Managing Expenses Is Not an Easy Task

2017-02-01T00:00:00.000-05:00

Coping with Costs

Big Data on Expense Volatility and Medical Payments

2017-01-18T00:00:00.000-05:00

The Ups and Downs of Small Business Employment

2017-01-01T00:00:00.000-05:00

The Ups and Downs of Small Business Employment Report

Big Data on Payroll Growth and Volatility

2016-11-15T00:00:00.000-05:00

Is the Online Platform Economy the Future of Work?

2016-11-01T00:00:00.000-05:00

The Online Platform Economy

Has Growth Peaked?

2016-11-01T00:00:00.000-04:00

Shedding Light on Daylight Saving Time

2016-09-21T00:00:00.000-04:00

For Small Businesses: Cash is King

2016-09-09T00:00:00.000-04:00

Big Spend on the Weekend:

The Local Consumer Commerce Index declined in May

2016-09-01T00:00:00.000-04:00

Cash is King: Flows, Balances, and Buffer Days

Evidence from 600,000 Small Businesses

2016-08-18T00:00:00.000-05:00

Past 65 and Still Working

Big Data Insights on Senior Citizens’ Financial Lives

2016-07-14T00:00:00.000-04:00

A Year of Low Gas Prices: The Consumer Response in 15 Metro Areas

2016-07-11T00:00:00.000-04:00

The Consumer Response to Lower Gas Prices

2016-07-01T00:00:00.000-04:00

The Consumer Response to a Year of Low Gas Prices

Evidence From 1 Million People

2016-06-29T00:00:00.000-04:00

Good Things Come in Small (Business) Packages

2016-05-05T00:00:00.000-05:00

The Online Platform Economy: Who earns the most?

2016-04-13T00:00:00.000-04:00

Taking the Financial Stress Out of Tax Time

2016-03-29T00:00:00.000-04:00

The Local Consumer Commerce Index

How did everyday spending fare in December 2015?

2016-02-18T00:00:00.000-05:00

Understanding Income Volatility and the Role of the Online Platform Economy

2016-02-09T00:00:00.000-05:00

Dining Out or Eating In: Where does your city rank?

Spending Growth at Restaurants

2016-02-08T00:00:00.000-05:00

Consumption Inequality: Where does your city rank?

Spending by the Top Income Quintile

2016-02-04T00:00:00.000-05:00

Travel for Business or Pleasure: Where does your city rank?

Share of Spending by Visitors to the Metro Area

2016-02-01T00:00:00.000-05:00

Paychecks, Paydays, and the Online Platform Economy

Big Data on Income Volatility

The Online Platform Economy Trajectory

What is the growth trajectory?

2016-01-31T00:00:00.000-05:00

Recovering from Job Loss

The Role of Unemployment Insurance

2016-01-18T00:00:00.000-05:00

Economic Contributions by Seniors

Spending by Consumers 65 years and Older

2016-01-07T00:00:00.000-05:00

Big Data to Build Sharper Profiles of Consumer Commerce at the City Level

2016-01-01T00:00:00.000-05:00

Boutiques or Big Box Stores: Where does your city rank?

Share of Spending at Small and Medium Enterprises

2015-12-01T00:00:00.000-05:00

Profiles of Local Consumer Commerce

Insights from 12 Billion Transactions in 15 U.S. Metro Areas

2015-10-01T00:00:00.000-04:00

How Falling Gas Prices Fuel the Consumer

Evidence From 25 Million People

2015-05-01T00:00:00.000-04:00

Weathering Volatility

Big Data on the Financial Ups and Downs of U.S. Individuals

Small Business Data Resources

Diverse Ownership

Business Dynamism

Regional Employment

Economic Activity

Where did recent gas price declines affect consumers the most?

JPMCI HOSP Geographic Data Visualization Tool

Major Market Events Data Visualization Tool

Infographic: How Falling Gas Prices Fuel the Consumer

Infographic: Weathering Volatility

Small Business Data Dashboard

Small businesses are an economically important component of the US economy and a key driver of production, employment, and growth.

How Much Cash Buffer Do You Need?

Data Visualization

You are now leaving JPMorgan Chase & Co.

JPMorgan Chase & Co.'s website terms, privacy and security policies don't apply to the site or app you're about to visit. Please review its website terms, privacy and security policies to see how they apply to you. JPMorgan Chase & Co. isn't responsible for (and doesn't provide) any products, services or content at this third-party site or app, except for products and services that explicitly carry the JPMorgan Chase & Co.

Global Banking Annual Review 2023: The Great Banking Transition

The Global Banking Annual Review 2023: The Great Banking Transition

Banking has had to chart a challenging course over the past few years, during which institutions faced increased oversight, digital innovation, and new competitors, and all at a time when interest rates were at historic lows. The past few months have also brought their share of upsets, including liquidity woes and some bank failures. But, broadly speaking, a favorable wind seems to have returned to the industry’s sails. The past 18 months have been the best period for global banking overall since at least 2007, as rising interest rates have boosted profits in a more benign credit environment.

About the authors

This report is a collaborative effort by Debopriyo Bhattacharyya, Miklós Dietz , Alexander Edlich , Reinhard Höll , Asheet Mehta , Brian Weintraub , and Eckart Windhagen , representing views from McKinsey’s Global Banking Practice.

Below the surface, too, much has changed: balance sheet and transactions have increasingly moved out of traditional banks to nontraditional institutions and to parts of the market that are capital-light and often differently regulated—for example, to digital payments specialists and private markets, including alternative asset management firms. While the growth of assets under management outside of banks’ balance sheets is not new, our analysis suggests that the traditional core of the banking sector—the balance sheet—now finds itself at a tipping point. Given the size of this movement, we have broadened the scope of this year’s Global Banking Annual Review to define banks as including all financial institutions except insurance companies.

In this year’s review, we focus on this “Great Banking Transition,” analyzing causes and effects and considering whether the improved performance in 2022–23 and the recent rise in interest rates in many economies could change its dynamics. To conclude, we suggest five priorities for financial institutions as they look to reinvent and future-proof themselves. The five are: exploiting leading technologies (including AI), flexing and potentially even unbundling the balance sheet, scaling or exiting transaction business, leveling up distribution, and adapting to the evolving risk landscape .

All financial institutions will need to examine each of their businesses to assess where their competitive advantages lie across and within the three core banking activities of balance sheet, transactions, and distribution. And they will need to do so in a world in which technology and AI will play a more prominent role, and against the backdrop of a shifting macroeconomic environment and heightened geopolitical risks.

The past 18 months brought banks their highest highs and lowest lows

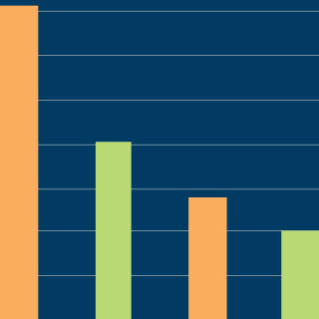

The recent upturn arises from the sharp increase in interest rates in many advanced economies, including a 500-basis-point rise in the United States. The higher interest rates enabled a long-awaited improvement in net interest margins, which boosted the sector’s profits by about $280 billion in 2022 and lifted return on equity (ROE) to 12 percent in 2022 and an expected 13 percent in 2023, compared with an average of just 9 percent since 2010 (Exhibit 1).

Over the past year, the banking sector has continued its journey of continuous cost improvement: the cost-income ratio dropped by seven percentage points from 59 percent in 2012 to about 52 percent in 2022 (partially driven by margin changes), and the trend is also visible in the cost-per-asset ratio (which declined from 1.6 to 1.5).

See past reports:

- 2022: Banking on a sustainable path

- 2021: The great divergence

- 2020: A test of resilience

- 2019: The last pit stop? Time for bold late-cycle moves

- 2018: Banks in the changing world of financial intermediation

- 2017: Remaking the bank for an ecosystem world

- 2016: A brave new world for global banking

- 2015: The fight for the customer

- 2014: The road back

The ROE growth was accompanied by volatility over the past 18 months. This contributed to the collapse or rescue of high-profile banks in the United States and the government-brokered takeover of one of Switzerland’s oldest and biggest banks. Star performers of past years, including fintechs and cryptocurrency players, have struggled against this backdrop.

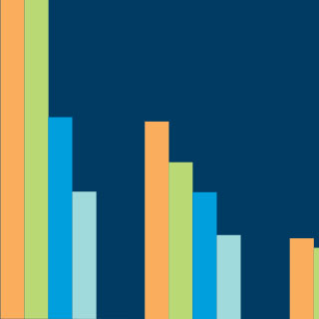

Performance varied widely within categories. While some financial institutions across markets have generated a premium ROE, strong growth in earnings, and above-average price-to-earnings and price-to-book multiples, others have lagged (Exhibit 2). While more than 40 percent of payments providers have an ROE above 14 percent, almost 35 percent have an ROE below 8 percent. Among wealth and asset managers, who typically have margins of about 30 percent, more than one-third have an ROE above 14 percent, while more than 40 percent have an ROE below 8 percent. Bank performance varies significantly, too. These variations indicate the extent to which operational excellence and decisions relating to cost, efficiency, customer retention, and other issues affecting performance are more important than ever for banking. Strongest performers tend to use the balance sheet effectively, are customer centric, and often lead on technology usage.

Between 2017 and 2022, payment providers, capital market infrastructure providers, and asset managers, as well as investment banks and brokers-dealers increased their price to earnings, whereas other financial institutions including GSIB (global systematically important banks), universal banks, and nonbank lenders saw a decline in their price to earnings.

Payment providers, investment banks and broker dealers also increased their earnings per share more than the other types of institutions. Consequently, these two types of institutions come out best in terms of value creation and total return to shareholders among financial institutions during this five-year period.

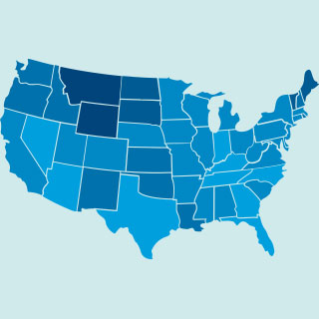

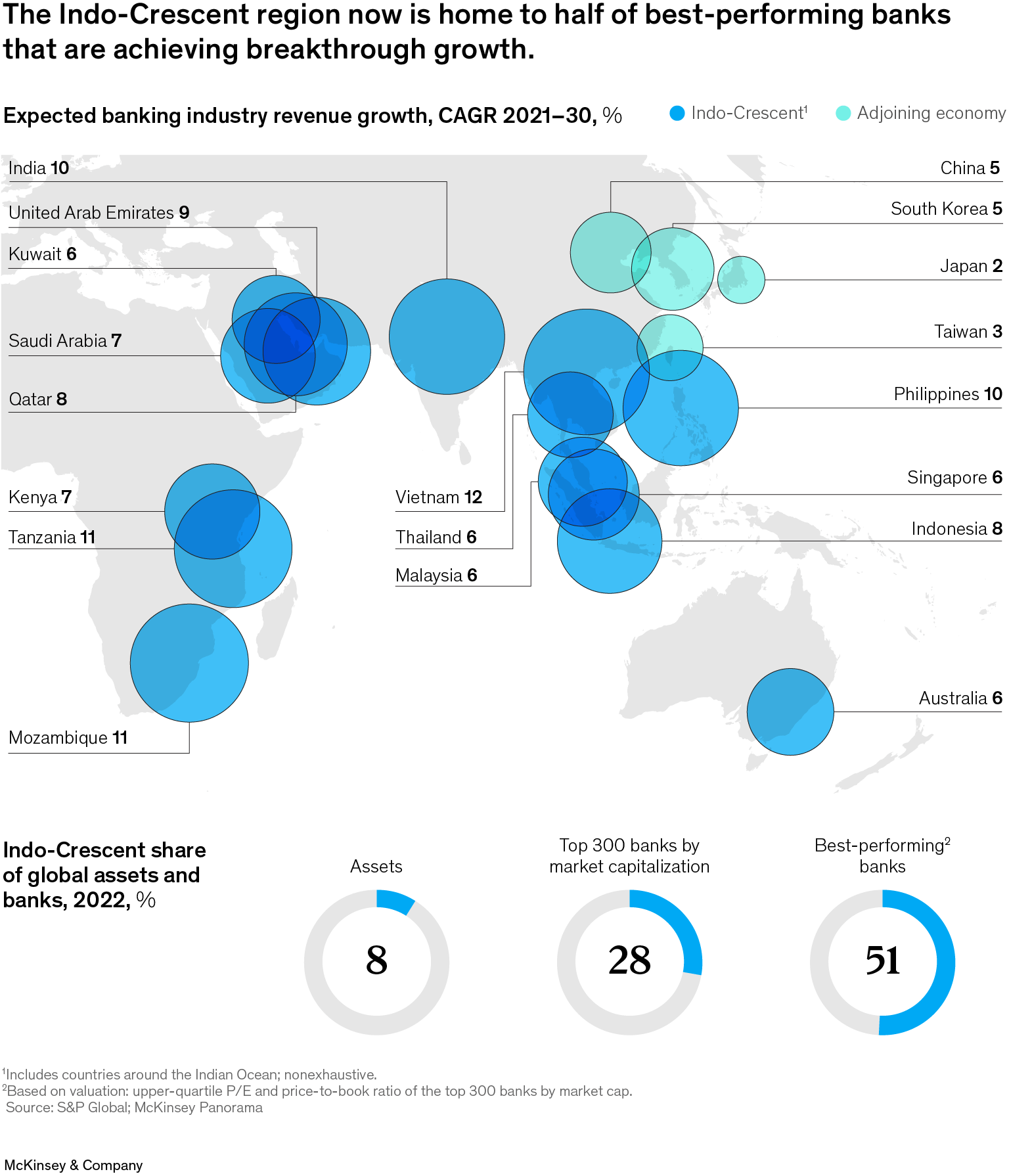

The geographic divergence we have noted in previous years also continues to widen. Banks grouped along the crescent formed by the Indian Ocean, stretching from Singapore to India, Dubai, and parts of eastern Africa, are home to half of the best-performing banks in the world (Exhibit 3). In other geographies, many banks buoyed by recent performance are able to invest again. But in Europe and the United States, as well as in China and Russia, banks overall have struggled to generate their cost of capital.

One aspect of banking hasn’t changed, however: the price-to-book ratio, which was at 0.9 in 2022. This measure has remained flat since the 2008 financial crisis and stands at a historic gap to the rest of the economy—a reflection that capital markets expect the duration-weighted return on equity to remain below the cost of equity. While the price-to-book ratio reflects some of the long-term systematic challenges the sector is facing, it also suggests the possible upside: every 0.1-times improvement in the price-to-book ratio would cause the sector’s value added to increase by more than $1 trillion.

Looking to the future, the outlook for financial institutions is likely to be especially shaped by four global trends. First, the macroeconomic environment has shifted substantially, with higher interest rates and inflation figures in many parts of the world, as well as a possible deceleration of Chinese economic growth. An unusually broad range of outcomes is suddenly possible, suggesting we may be on the cusp of a new macroeconomic era. Second, technological progress continues to accelerate, and customers are increasingly comfortable with and demanding about technology-driven experiences. In particular, the emergence of generative AI could be a game changer, lifting productivity by 3 to 5 percent and enabling a reduction in operating expenditures of between $200 billion and $300 billion, according to our estimates. Third, governments are broadening and deepening regulatory scrutiny of nontraditional financial institutions and intermediaries as the macroeconomic system comes under stress and new technologies, players, and risks emerge. For example, recently published proposals for a final Basel III “endgame” would result in higher capital requirements for large and medium-size banks, with differences across banks. And fourth, systemic risk is shifting in nature as rising geopolitical tensions increase volatility and spur restrictions on trade and investment in the real economy.

The Great Transition for the balance sheet, transactions, and payments has gained momentum

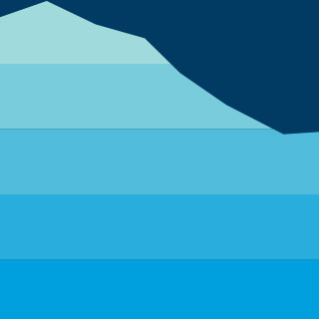

In this context, the future dynamics of the Great Transition are critical for the banking sector overall. Evidence of the transition’s profound effect on the sector to date abounds. For example, between 2015 and 2022, more than 70 percent of the net increase of financial funds ended up off banking balance sheets, held by insurance and pension funds, sovereign wealth funds and public pension funds, private capital, and other alternative investments, as well as retail and institutional investors (Exhibit 4).

The shift off the balance sheet is a global phenomenon (Exhibit 5). In the United States, 75 percent of the net increase in financial funds ended up off banking balance sheets, while the figure in Europe is about 55 percent.

The growth of private debt is another manifestation of the transition away from traditional financial institutions. Private debt saw its highest inflows in 2022, with growth of 29 percent, driven by direct lending.

Beyond the balance sheet, transactions and payments also are shifting. For example, consumer digital payment processing conducted by payments specialists grew by more than 50 percent between 2015 and 2022 (Exhibit 6).

The oscillating interest rate environment will affect the Great Transition, but exactly how remains to be seen. We may be going through a phase in which a long-term macroeconomic turning point—including a higher-for-longer interest rate scenario and an end to the asset price super cycle—changes the attractiveness of some models that were specifically geared to the old environment, while other structural trends, especially in technology, continue. Fundamentally, the question for banks is to what extent they can offer the products in high demand at a time when risk capacity is broadening and many clients and customers are searching for the highest deposit yields.

Focusing on five priorities can help banks capture the moment

Regardless of the macroeconomic developments, financial institutions will have to adapt to the changing environment of the Great Transition, especially the trends of technology, regulation, risk, and scale. Mergers and acquisitions may gain importance.

As financial institutions consider how they want to change, we outline five priorities which, though not an exhaustive list, can serve as thought starters (Exhibit 7).

- Exploit technology and AI to improve productivity, talent management, and the delivery of products and services. This includes applying AI and advanced analytics to deploy process automation, platforms, and ecosystems. Other principles associated with success include operating more like a tech company to scale the delivery of products and services; cultivating a cloud-based, platform-oriented architecture; and improving capabilities to address technology risks. Distinctive technology development and deployment will increasingly become a critical differentiator for banks.

- Flex and even unbundle the balance sheet. Flexing implies active use of syndication, originate-to-distribute models, third-party balance sheets (for example, as part of banking-as-a-service applications), and a renewed focus on deposits. Unbundling, which can be done to varying degrees and in stages, pushes this concept further and can mean separating out customer-facing businesses from banking as a service and using technology to radically restructure costs.

- Scale or exit transaction business. Scale in a market or product is a key to success, but it can be multifaceted. Institutions can find a niche in which to go deep, or they can look to cover an entire market. Banks can aggressively pursue economies of scale in their transactions business, including through M&A (which has been a major differentiator between traditional banks and specialists) or by leveraging partners to help with exits.

- Level up distribution to sell to customers and advise them directly and indirectly, including through embedded finance and marketplaces and by offering digital and AI-based advisory. An integrated omnichannel approach could make the most of automation and human interaction, for example. Deciding on a strategy for third-party distribution—which could be via partnerships to create embedded finance opportunities or platform-based models—can create opportunities to serve customer needs including with products outside the institution’s existing business models.

- Adapt to changing risks. Financial institutions everywhere will need to stay on top of the ever-evolving risk environment. In the macroeconomic context, this includes inflation, an unclear growth outlook, and potential credit challenges in specific sectors such as commercial real estate exposure. Other risks are associated with changing regulatory requirements, cyber and fraud risk, and the integration of advanced analytics and AI into the banking system. To manage these risks, banks could consider elevating the risk function to make it a true differentiator. For example, in client discussions, product design, and communications they could highlight the bank’s resilience based on its track record of managing systemic risk and liquidity. They could also further strengthen the first line and embed risk in day-to-day activities, including investing in new risk activities driven by the growth of generative AI. Underlying changes in the real economy will likely continue in unexpected ways, requiring banks to remain ever more vigilant.

All these priorities have significant implications for financial institutions’ capital plans, including the more active raising and return of capital. As financial institutions reexamine their businesses and identify their relative competitive advantages in each of the balance sheet, transactions, and distribution components, they will need to ensure that they are positioned to generate adequate returns. And they will need to do so in a very different macroeconomic and geopolitical environment and at a time when AI and other technologies are potentially changing the environment and with a broader set of competitors. Scale and specialization will be determinant, as will value-creating diversification. Minimum economies of scale are also likely to shift, especially where technology and data are the drivers of scale. The years ahead will likely be more dynamic than the immediate past, with the gap between winners and losers increasing even more. Now is the time to begin charting the path forward.

Debopriyo Bhattacharyya is a director of solution delivery in McKinsey’s Gurugram office; Miklós Dietz is a senior partner in the Vancouver office; Alexander Edlich and Asheet Mehta are senior partners in the New York office, where Brian Weintraub is a partner; Reinhard Höll is a partner in the Berlin office, and Eckart Windhagen is a senior partner in the Frankfurt office.

The authors would like to thank the following colleagues for their contributions to this report: Mayank Aggarwal, Krishna Bhattacharya, Alessio Botta, Andrea Cappo, Miguel Leiria Carvalho, Cristina Catania, Matt Cooke, Alison Corsi, Julie Crothers, Anubhav Das, Chris Depin, Thorsten Ehinger, Nnenna Elumogo, Xiyuan Fang, Fuad Faridi, Max Flötotto, Suhrid Gajendragadkar, Jeff Galvin, Amit Garg, Jonathan Godsall, Peter Gumbel, Nils Jean-Mairet, Rushabh Kapashi, Attila Kincses, Ida Kristensen, Matthieu Lemerle, Kate McCarthy, Jared Moon, Jesus Moreno, Marie-Claude Nadeau, Jatin Pant, Thomas Poppensieker, Angela Samper, Gokhan Sari, Manu Saxena, Kai Schindelhauer, Simone Schöberl, Joydeep Sengupta, Vishnu Sharma, Mark Staples, Vik Sohoni, Gregor Theisen, Marco Vettori, and Nicole Zhou.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

McKinsey’s Global Banking Annual Review archive: 2014 to 2022

Search for:

BAI gives financial services leaders the confidence to make smart business decisions, every day.

- Board of Directors

- In the News

- Advertising & Sponsorship

Trusted, Accurate & Relevant Online Training Courses for Banks & Financial Institutions

- Compliance Courseware

- Professional Development Courseware

- Professional Skills Library

- Leadership Innovation Library

- Board of Directors Insight Series

- BAI Learning Manager

- BAI Career Pathing

- BAI Training Insights

- BAI Documents & Resources

- System Requirements

- Regulatory Resources

- Quick and Easy Setup

- Focused Processes

- Powerful Communication Tools

- Credit Unions

- Mortgage Lenders

- Customer Benefits

- Tailored Solutions

- Terms of Service

Real Data, Real Insights, Real Results

- Business Banking

- Consumer Banking

- Digital Banking

- Talent Management

- Banking Trends by BAI Banking Outlook

- Small Business Reporting from BQ and BAI

Your trusted source for actionable insights and groundbreaking ideas.

- Compliance, Regulation & Risk

- Customer Experience

- DEI & ESG

- Fraud Prevention

- Marketing & Sales

- Talent & Workforce Management

Infographic

- Roundtables

- Learning Manager Login

- Research & Benchmarking

Validate Results, Find Opportunities, Create Strategies – Repeat

What do you get from participating in BAI Research Programs?

- Macro level Insights , derived from direct reported data, into the biggest banking trends

- Validation of your initiatives compared to your peers, so you know if you’re lagging or leading

- Deposit Product level analysis

- Market level analysis

- Segment level analysis

- Channel level analysis

- Timely data to keep a pulse on the market dynamics

- Detailed metrics to measure what matters

- Interpretation and review of results from BAI Research Intelligence Experts

Without real data, you could miss insights into understanding how you’re doing and where you need to shift. BAI’s independent, unbiased programs allow you to stop guessing and start implementing.

True Industry Expertise

We’ve delivered actionable benchmarking data and insights for two decades , enabling leaders to make smart business decisions every day. With the majority of the top 100 U.S. Financial Institutions contributing and relying on BAI to provide timely and insightful metrics we offer a bird’s eye view through data and conversations about what is really happening in the constantly evolving financial services industry.

What’s in Our Database?

Consumer deposits benchmarking:.

U.S. MARKET SHARE

PRODUCT BALANCES

Small Business Benchmarking (Businesses up to $20MM):

MARKET SHARE

Go In-Depth With Our Benchmarking Programs

Consumer banking: deposits & cross-sell.

BAI helps financial institutions understand consumer deposit benchmarking in the industry. The unique resource enables you to assess total deposit performance versus peers. Validate results, find opportunities, and create strategies. This report goes in-depth by product, account, household, and various segments.

Small Business Banking: Deposits & Cross-Sell

Define small banking your way by cutting BAI’s data how you need to see it, up to $20MM. This way, you can finally get comparable insights versus your peers. The report goes in-depth by business size, business age, industry and product to help you confirm results, find opportunities, and create strategies.

Digital is complex. BAI brings a unique view into your digital performance to help you simplify results so you can validate how your digital acquisition, on-boarding, and adoption metrics compare to your peers.

BAI brings banking and organizational structure insight into people management. This includes recruiting and retention metrics, as well as DEI initiatives.

How BAI’s Unbiased Benchmarking Works for You

We provide unbiased insight into your performance. As a nonprofit, independent organization, we have no agenda other than promoting the best interests of financial institutions and the industry as a whole.

Submit Your Data

Detailed reports, objective analysis, thorough presentations, ongoing reports.

We collect and anonymize important banking data about your organization, customers, employees, and outcomes.

You receive detailed reports with options to segment in multiple areas such as; generations, granular geography, wealth, channel, and more.

We compare your data to your industry peers, objectively evaluating your performance across segments through measurable metrics and scorecards.

Our Research Intelligence Experts present the benchmarking results to your entire team. The executive readouts, 1:1 reviews, and training help ensure a clear understanding of your report.

Add ongoing Pulse Reports for weekly or monthly updates to keep you up-to-date.

The Small Business Landscape is Rapidly Changing. Use BAI’s Small Business Industry Report to understand how to adapt.

Small business industry data gives financial services organizations the power to serve their customers. BAI and BrightQuery (BQ) have formed a strategic alliance to provide the resources businesses need to understand their markets, customers, and future.

Using 100% of private and public company information, this industry report created in conjunction with BAI allows you to see what is changing monthly in the Small Business Landscape. Select views by industry, size, age, and geography to drill, confirm, and discover areas of opportunities or risks.

Have the clarity and confidence to make smart, strategic decisions for your organization and the businesses that you serve.

“If I ever went to a bank that didn’t have BAI research, I would bring it in!”

Executive Super Regional Bank

“The BAI team provides insights and presents information through the lens of a banker – and I really appreciate that”.

What Can Unbiased Benchmarking Do for You?

Get more insights. Ask better questions. Glean actionable intelligence and boost your performance. Expand your potential with BAI’s unbiased benchmarking.

Leverage Your Knowledge With BAI Banking Outlook

Dive deeper into the state of the industry.

State of the U.S. Deposit Market

Apr 25, 2024

Top trends and challenges for 2024

Feb 20, 2024

Banking outlook for 2024 and beyond

Feb 16, 2024

we are here to help

Want to learn more about Benchmarking?

See how BAI’s unbiased benchmarking unlocks actionable insights for your financial institution.

- The BAI Mission

- Advertising & Sponsorship

- Compliance & Training

- BAI Policy Manager

- Small Business Industry Reporting

- Banking Outlook

- Banking Strategies

- Privacy Policy

- Antitrust Compliance Statement

- Terms of Use

- © BAI 2024 All rights reserved. BAI is Bank Administration Institute and BAI Center.

Analytics Cookies

- Tracking Cookies

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East & Africa

- North America

- Australia & New Zealand

Mainland China

- Hong Kong SAR, China

- Philippines

- Taiwan, China

- Channel Islands

- Netherlands

- Switzerland

- United Kingdom

- Saudi Arabia

- South Africa

- United Arab Emirates

- United States

From startups to legacy brands, you're making your mark. We're here to help.

- Innovation Economy Fueling the success of early-stage startups, venture-backed and high-growth companies.

- Midsize Businesses Keep your company growing with custom banking solutions for middle market businesses and specialized industries.

- Large Corporations Innovative banking solutions tailored to corporations and specialized industries.

- Commercial Real Estate Capitalize on opportunities and prepare for challenges throughout the real estate cycle.

- Community Impact Banking When our communities succeed, we all succeed. Local businesses, organizations and community institutions need capital, expertise and connections to thrive.

- International Banking Power your business' global growth and operations at every stage.

- Client Stories

Prepare for future growth with customized loan services, succession planning and capital for business equipment.

- Asset Based Lending Enhance your liquidity and gain the flexibility to capitalize on growth opportunities.

- Equipment Financing Maximize working capital with flexible equipment and technology financing.

- Trade & Working Capital Experience our market-leading supply chain finance solutions that help buyers and suppliers meet their working capital, risk mitigation and cash flow objectives.

- Syndicated Financing Leverage customized loan syndication services from a dedicated resource.

- Employee Stock Ownership Plans Plan for your business’s future—and your employees’ futures too—with objective advice and financing.

Institutional Investing

Serving the world's largest corporate clients and institutional investors, we support the entire investment cycle with market-leading research, analytics, execution and investor services.

- Institutional Investors We put our long-tenured investment teams on the line to earn the trust of institutional investors.

- Markets Direct access to market leading liquidity harnessed through world-class research, tools, data and analytics.

- Prime Services Helping hedge funds, asset managers and institutional investors meet the demands of a rapidly evolving market.

- Global Research Leveraging cutting-edge technology and innovative tools to bring clients industry-leading analysis and investment advice.

- Securities Services Helping institutional investors, traditional and alternative asset and fund managers, broker dealers and equity issuers meet the demands of changing markets.

- Financial Professionals

- Liquidity Investors

Providing investment banking solutions, including mergers and acquisitions, capital raising and risk management, for a broad range of corporations, institutions and governments.

- Center for Carbon Transition J.P. Morgan’s center of excellence that provides clients the data and firmwide expertise needed to navigate the challenges of transitioning to a low-carbon future.

- Corporate Finance Advisory Corporate Finance Advisory (“CFA”) is a global, multi-disciplinary solutions team specializing in structured M&A and capital markets. Learn more.

- Development Finance Institution Financing opportunities with anticipated development impact in emerging economies.

- Sustainable Solutions Offering ESG-related advisory and coordinating the firm's EMEA coverage of clients in emerging green economy sectors.

- Mergers and Acquisitions Bespoke M&A solutions on a global scale.

- Capital Markets Holistic coverage across capital markets.

- Capital Connect

- In Context Newsletter from J.P. Morgan

- Director Advisory Services

Accept Payments

Explore Blockchain

Client Service

Process Payments

Manage Funds

Safeguard Information

Banking-as-a-service

Send Payments

- Partner Network

A uniquely elevated private banking experience shaped around you.

- Banking We have extensive personal and business banking resources that are fine-tuned to your specific needs.

- Investing We deliver tailored investing guidance and access to unique investment opportunities from world-class specialists.

- Lending We take a strategic approach to lending, working with you to craft the fight financing solutions matched to your goals.

- Planning No matter where you are in your life, or how complex your needs might be, we’re ready to provide a tailored approach to helping your reach your goals.

Whether you want to invest on your own or work with an advisor to design a personalized investment strategy, we have opportunities for every investor.

- Invest on your own Unlimited $0 commission-free online stock, ETF and options trades with access to powerful tools to research, trade and manage your investments.

- Work with our advisors When you work with our advisors, you'll get a personalized financial strategy and investment portfolio built around your unique goals-backed by our industry-leading expertise.

- Expertise for Substantial Wealth Our Wealth Advisors & Wealth Partners leverage their experience and robust firm resources to deliver highly-personalized, comprehensive solutions across Banking, Lending, Investing, and Wealth Planning.

- Why Wealth Management?

- Retirement Calculators

- Market Commentary

Who We Serve

Explore a variety of insights.

Global Research

- Newsletters

Insights by Topic

Explore a variety of insights organized by different topics.

Insights by Type

Explore a variety of insights organized by different types of content and media.

- All Insights

We aim to be the most respected financial services firm in the world, serving corporations and individuals in more than 100 countries.

Institutional Investor Surveys

2024 Institutional Investor Surveys

J.P. Morgan Global Research. Setting a new standard.

Please provide your feedback in the Institutional Investor surveys.

Strategic, full-service solutions to support your evolving governance needs

Key opportunity spaces for the pharmaceuticals sector in 2024.

Chris: Heading into 2024, we're seeing a really exciting opportunity to revisit the pharmaceutical sector given some of the underperformance we saw in 2023. We've got investors sentiments actually pretty bearish for the group right now. And we think that's going to be a really nice opportunity for investors to look at a fairly well positioned group at record low valuations.

Chris: We're really excited about the innovation more broadly across the sector. If you just think about 2023, we had the first disease modifying Alzheimer's drug fully approved by the FDA. If you look at oncology market, we had new technologies, things like CAR-T, bispecific antibodies, ADCs, meaningfully improving standard of care in a number of tumor types. These are huge markets where you haven't seen innovation in the last decade or longer.

Chris: The GLP one category. This year has been really an exciting year. We're estimating that this will be over a hundred billion revenue opportunity for the sector by the time we go out to the early 2030s. And that would make the GLP-1s the largest therapeutic market we've ever seen. We're expecting the capacity for the GLP-1s to double in 2024, increase another 50% in 2025, and that should really alleviate the bottlenecks we have from the capacity standpoint.

Chris: As we think about M&A, the themes really remain growth and innovation and that should lead to further consolidation of the small and mid-cap biotech sector, particularly the higher quality names. What we're seeing is a pivot away from larger, more complex transactions that we saw in the past. And instead what the industry seems to be doing is looking at these kind of smaller assets that are easier to integrate.

Chris: As I think about healthcare reform, the big focus for us is going to be on drug price negotiations. This is really coming about because of the inflation reduction act, which is allowing the US government for the first time to directly negotiate drug pricing with the pharmaceutical industry. Many of these are going to make drugs more affordable for seniors, which is great. But for the drug industry specifically, we're got to really watch to see how these negotiations go. It's a big overhang for the sector. One we think is manageable, but obviously we've got to watch exactly how these negotiations play out.

Lisa: Things to watch for in 2024 when we think about healthcare services specific to managed care and facilities, one, utilization trends. If you think about 2023, we saw an uptick in Medicare advantage utilization trends, we anticipate that those trends will carry forward into the first half of 2024. Second, GLP-1, the impact on both sides. How will this impact the commercial market? How will it impact PBMs? Third, the presidential election.

Lisa: GLP-1 were a big area of topic in 2023. They are currently not covered by Medicare or Medicaid. However, as we move into 2024, We'll need a legislative change for them to be covered.

We recently conducted a survey of 50 of the top 500 companies in the country, a large percentage of them are saying they're not going to cover it for weight loss, so we'll have to wait and see what happens.

Lisa: As we think about the medical costs and pharmacy costs in 24, we're getting back to normalization. Post covid, we had two years where people did not go to the doctor. They did not have surgical procedures done.

We had anticipated coming into 23 that we would see a higher acuity level. what we saw this year is that both cardiac procedures as well as orthopedic procedures, were higher than expected.

As we go into 2024, we expect that trend to continue within Medicare Advantage. On the commercial side, we have generally seen in line, utilization trends across the commercial population.

Lisa: As we think about potential legislative changes for the PBM, pharmacy benefit management business. One of the areas that they're trying to drive is more transparency in the business model. We believe any of the legislation is pretty benign to the current industry as we see it and therefore remain positive on the industry.

Environmental Social Governance is growing in every geography around the globe. It’s in the headlines, high up on the agendas of corporations, and at the forefront of investor interest.

Even though it started to take shape in the 1960s, ESG has gained significant momentum in recent years, with 2020 standing out as a milestone year in this space. Adoption across the global asset management industry more than doubled, with total ESG funds growing more than 100 percent. And companies are now rally more ambitious ESG goals.

What’s driving the move from momentum to mainstream?

This is ESG Investing, Unpacked.

ESG Investing looks at an asset, like equities or bonds, through an Environmental, Social and Governance lens.

The goal is to determine whether the asset makes a positive impact. For example, fighting climate change or supporting safe working conditions. Governance is all about how a company balances stakeholder interests: How are decisions made? What processes are in place? Who benefits?

Here’s another way to think about it: The “E” and “S” are the end results. The “G” determines how these results are achieved.

This data helps investors make better-informed decisions.

The rise of ESG investing is based on a few points in history. Among them are the social movements against the Vietnam war and apartheid in South Africa, when companies faced divestments in opposition.

In 1981, the first major U.S. organization that advances responsible investing was founded: The U.S. Sustainable Investment Forum. And key events created global awareness of environmental issues.

In 2008, the Financial Crisis called into question the industry’s social license to operate: How can the financial system works for everyone and not just shareholders? In 2015, 196 countries signed the Paris Agreement to reduce carbon emissions.

Most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the connectivity between crises: Public health, climate change and social inequality. In response, companies prioritized even more ambitious goals around ESG.

Three main ESG Investing strategies are growing quickly. Negative Screening typically excludes investments related to weapons, tobacco and fossil fuels. While exclusions were historically based on moral or religious preferences, now it’s about the financial risk associated with the negative impact of industries, such as human health for tobacco and climate change for fossil fuels.

ESG Integration has become the leading strategy. It focuses on how companies incorporate ESG criteria into their daily activities to achieve long-term financial performance. Then, ESG considerations and timelines are factored into risk analysis and investment decisions moving forward.

Impact Investing is the newest strategy. It intentionally aims to create positive social and environmental impact that is actively measured, as well as financial return. Like investing in the private debt of a company with a business model aimed at providing access to high-quality education for students from low-income backgrounds. Impact Investing is becoming increasingly common because more people want their money to contribute to the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals.

The ESG lens can be applied to any asset class. While equity is the most common, representing half of total ESG assets under management, green bonds are on the rise. Typically purchased by institutional investors, they help finance a company’s specific project climate-related or environmental project.

Sustainability-linked bonds are also gaining traction. These are performance-based and tied to whether the issuer achieves pre-defined ESG objectives within a set timeline.

Many investors are now looking beyond ESG targets and are increasingly focused on measurable results with clear plans. This trend, along with wanting more of a say in a company’s ESG practices, is expected to continue for the next several years.

Heightened regulation including environmental, employment, and civil protections, is another factor driving ESG market growth. Around 90 percent of oversight was implemented in the last 20 years and 50 percent arrived after 2010.

Europe leads this effort, where public companies are required to report implemented policies and where regulations are constantly evolving to reflect broader sustainability goals. Take the EU Green Deal, a set of policies to help the EU reduce emissions 55 percent by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050.

But sustainability challenges are global and require mobilized capital to solve them, all countries are working on ESG. Asia is beginning to implement its own regulations, and the U.S. administration is currently working on its own standards as well.

For the next several years, innovation will continue to shape the ESG landscape. From advancements in clean energy, like the growing hydrogen market, to how companies will deliver on advancing racial equality, and the upcoming public investments on clean infrastructures, all eyes are on ESG.

How healthy is the US economy? Could a recession be coming? How do investors feel about the current economic situation?

While none of us can see into the future, yield curves can help us map what lies ahead, answering these questions and many more with surprisingly-high levels of accuracy. So what exactly is a yield curve and how can one little line tell us so much? "

This is "Yield Curves: Unpacked.

In a nutshell, a yield curve is found on a graph that compares bond yields to maturity dates. Once plotted, the points are joined together with a line, forming the familiar yield curve. Here are four terms you'll need to understand to wrap your head around yield curves.

Bonds are debt securities issued by governments and corporations to raise money. In other words, bonds are a loan from an investor to an issuer. If an investor buys a Treasury bond, for example, they're essentially lending money to the U.S. government. Coupons are fixed interest payments, which investors receive periodically. This is the same as the interest paid on any loan, such as a mortgage or personal loan.

Maturity is when a bond's term comes to an end. This can be from 1 year to more than 10 years. At this point, the investor will get back the money they paid for the bond.

Yields are the returns made on a bond. The simplest version of yield is calculated by dividing the interest rate by the bond's current market price. Longer-term bonds will have higher yields-- in a stable economic environment, anyway. This is because they're considered riskier investments, as there's more time for market conditions and bond prices to change.

While a price change doesn't affect the fixed coupon payment, it does affect the yield. When prices go up, yields go down, making the bond less appealing. When long-term bonds have higher yields than short-term bonds, this forms the typical upward slope of a yield curve from left to right. A steeper slope can signal better economic conditions ahead, with higher growth and inflation, meaning better returns on long-term bonds.

Yield curves can also invert and slope in the opposite direction. This happens when short-term bonds have higher yields than long-term bonds. It's rare, but it can signal that an economic slowdown or even a recession is coming. This is particularly true of the U.S. Treasury yield curve, which tracks yields on short- and long-term treasuries. If you hear someone talking about the yield curve, they're likely referring to this one. And it's predicted past recessions with a great degree of accuracy.

How is this possible? First, the Treasury yield curve is a good reflection of investor sentiment. If investors expect interest rates to fall in the future, they might buy longer-term bonds to lock in the current rate, pushing up the price and lowering the yield. This is one way a yield curve can invert.

Low interest rates are usually associated with a weak economic environment, which is why this pattern can spell bad news for the economy-- if investors are correct, of course. Another reason is simply that the Treasury yield curve is so widely watched. Potential signs of a flattening curve may be enough to put markets in a spin.

There can be many reasons behind the pattern seen on a yield curve. And it's hard to account for all the forces at play within the bond market. But whatever the reasons might be, the Treasury yield curve will remain a strong signal of economic activity.

Research insights

Watch our Research Insights to learn about the key trends impacting the global economy.

Research podcasts

Research Podcast

At Any Rate

Analysts from J.P. Morgan Global Research take a closer look at the stories behind some of the biggest trends, themes and developments in markets today.

Global Data Pod

Economists from J.P. Morgan Global Research offer their analysis on the economic data, macro trends and monetary and fiscal policy impacting the world today.

Our platforms

J.P. Morgan Markets

Delivering the latest Research, Trading and Post-Trade services to clients.

A portal into the industry-leading proprietary financial market data from Markets Research and Trading.

Global Index Research

Providing insights, bespoke products and informed index management decisions.

Macro quantamental trading made easy by breaking down the barriers between purely quantitative and fundamental trading styles.

Research in numbers

Research coverage

analysts located in 25 countries

countries covered

companies covered

Best-in-class thought leadership

pieces of research

Global recognition

Through breadth of our coverage, the depth of our expertise and our commitment to client service, we have become the trusted advisor for clients across the globe. Our top rankings across industry surveys reflect the deep trust and important relationships we have developed with our clients.

Top Global Research Firm (2023)

Institutional Investor

Top Global Fixed Income Research Firm (2023)

#2 global equity research firm (2023), top us fixed income research firm (2023), top latin america fixed income research firm (2023), #2 all-america equity research firm (2023), #3 latin america equity research firm (2023), top developed europe fixed income research firm (2023), top emerging emea fixed income research firm (2023), #3 developed europe equity research firm (2023), top emerging emea equity research firm (2023), #2 asia (ex-japan) fixed income research firm (2023), top japan fixed income research firm (2023), #3 asia (ex-japan) equity research firm (2023), top international equity research firm in japan (2024), modal title.

You're now leaving J.P. Morgan

J.P. Morgan’s website and/or mobile terms, privacy and security policies don’t apply to the site or app you're about to visit. Please review its terms, privacy and security policies to see how they apply to you. J.P. Morgan isn’t responsible for (and doesn’t provide) any products, services or content at this third-party site or app, except for products and services that explicitly carry the J.P. Morgan name.

- Open access

- Published: 18 June 2021

Financial technology and the future of banking

- Daniel Broby ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5482-0766 1

Financial Innovation volume 7 , Article number: 47 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

44k Accesses

55 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper presents an analytical framework that describes the business model of banks. It draws on the classical theory of banking and the literature on digital transformation. It provides an explanation for existing trends and, by extending the theory of the banking firm, it illustrates how financial intermediation will be impacted by innovative financial technology applications. It further reviews the options that established banks will have to consider in order to mitigate the threat to their profitability. Deposit taking and lending are considered in the context of the challenge made from shadow banking and the all-digital banks. The paper contributes to an understanding of the future of banking, providing a framework for scholarly empirical investigation. In the discussion, four possible strategies are proposed for market participants, (1) customer retention, (2) customer acquisition, (3) banking as a service and (4) social media payment platforms. It is concluded that, in an increasingly digital world, trust will remain at the core of banking. That said, liquidity transformation will still have an important role to play. The nature of banking and financial services, however, will change dramatically.

Introduction

The bank of the future will have several different manifestations. This paper extends theory to explain the impact of financial technology and the Internet on the nature of banking. It provides an analytical framework for academic investigation, highlighting the trends that are shaping scholarly research into these dynamics. To do this, it re-examines the nature of financial intermediation and transactions. It explains how digital banking will be structurally, as well as physically, different from the banks described in the literature to date. It does this by extending the contribution of Klein ( 1971 ), on the theory of the banking firm. It presents suggested strategies for incumbent, and challenger banks, and how banking as a service and social media payment will reshape the competitive landscape.

The banking industry has been evolving since Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena opened its doors in 1472. Its leveraged business model has proved very scalable over time, but it is now facing new challenges. Firstly, its book to capital ratios, as documented by Berger et al ( 1995 ), have been consistently falling since 1840. This trend continues as competition has increased. In the past decade, the industry has experienced declines in profitability as measured by return on tangible equity. This is partly the result of falling leverage and fee income and partly due to the net interest margin (connected to traditional lending activity). These trends accelerated following the 2008 financial crisis. At the same time, technology has made banks more competitive. Advances in digital technology are changing the very nature of banking. Banks are now distributing services via mobile technology. A prolonged period of very low interest rates is also having an impact. To sustain their profitability, Brei et al. ( 2020 ) note that many banks have increased their emphasis on fee-generating services.

As Fama ( 1980 ) explains, a bank is an intermediary. The Internet is, however, changing the way financial service providers conduct their role. It is fundamentally changing the nature of the banking. This in turn is changing the nature of banking services, and the way those services are delivered. As a consequence, in order to compete in the changing digital landscape, banks have to adapt. The banks of the future, both incumbents and challengers, need to address liquidity transformation, data, trust, competition, and the digitalization of financial services. Against this backdrop, incumbent banks are focused on reinventing themselves. The challenger banks are, however, starting with a blank canvas. The research questions that these dynamics pose need to be investigated within the context of the theory of banking, hence the need to revise the existing analytical framework.

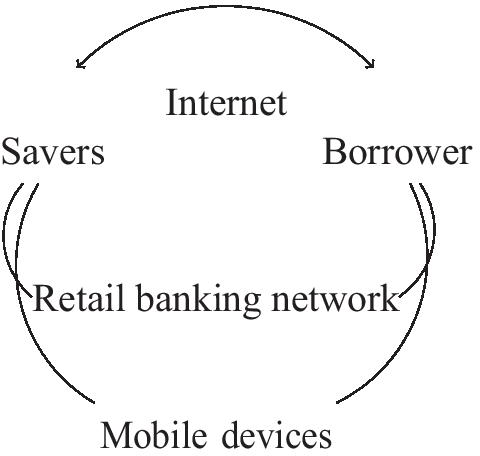

Banks perform payment and transfer functions for an economy. The Internet can now facilitate and even perform these functions. It is changing the way that transactions are recorded on ledgers and is facilitating both public and private digital currencies. In the past, banks operated in a world of information asymmetry between themselves and their borrowers (clients), but this is changing. This differential gave one bank an advantage over another due to its knowledge about its clients. The digital transformation that financial technology brings reduces this advantage, as this information can be digitally analyzed.

Even the nature of deposits is being transformed. Banks in the future will have to accept deposits and process transactions made in digital form, either Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC) or cryptocurrencies. This presents a number of issues: (1) it changes the way financial services will be delivered, (2) it requires a discussion on resilience, security and competition in payments, (3) it provides a building block for better cross border money transfers and (4) it raises the question of private and public issuance of money. Braggion et al ( 2018 ) consider whether these represent a threat to financial stability.

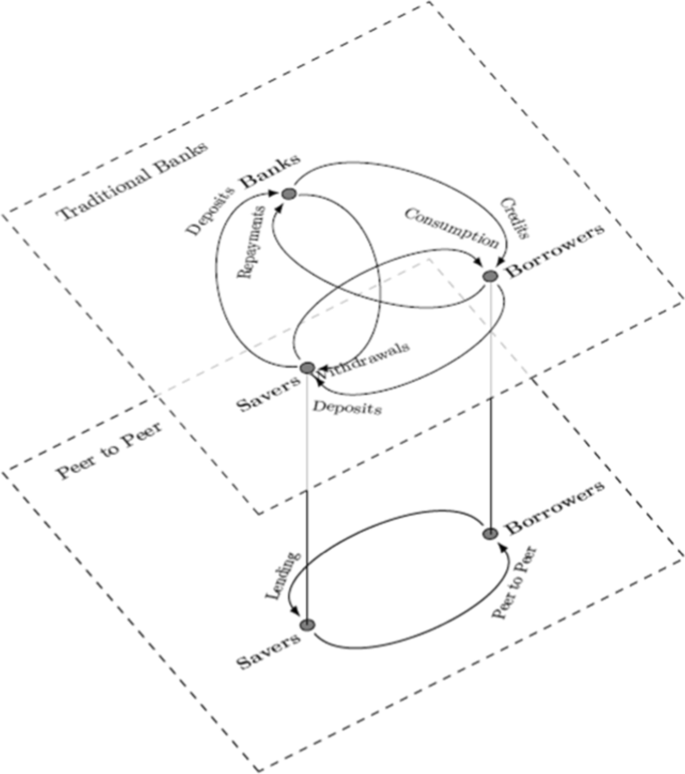

The academic study of banking began with Edgeworth ( 1888 ). He postulated that it is based on probability. In this respect, the nature of the business model depends on the probability that a bank will not be called upon to meet all its liabilities at the same time. This allows banks to lend more than they have in deposits. Because of the resultant mismatch between long term assets and short-term liabilities, a bank’s capital structure is very sensitive to liquidity trade-offs. This is explained by Diamond and Rajan ( 2000 ). They explain that this makes a bank a’relationship lender’. In effect, they suggest a bank is an intermediary that has borrowed from other investors.

Diamond and Rajan ( 2000 ) argue a lender can negotiate repayment obligations and that a bank benefits from its knowledge of the customer. As shall be shown, the new generation of digital challenger banks do not have the same tradeoffs or knowledge of the customer. They operate more like a broker providing a platform for banking services. This suggests that there will be more than one type of bank in the future and several different payment protocols. It also suggests that banks will have to data mine customer information to improve their understanding of a client’s financial needs.

The key focus of Diamond and Rajan ( 2000 ), however, was to position a traditional bank is an intermediary. Gurley and Shaw ( 1956 ) describe how the customer relationship means a bank can borrow funds by way of deposits (liabilities) and subsequently use them to lend or invest (assets). In facilitating this mediation, they provide a service whereby they store money and provide a mechanism to transmit money. With improvements in financial technology, however, money can be stored digitally, lenders and investors can source funds directly over the internet, and money transfer can be done digitally.

A review of financial technology and banking literature is provided by Thakor ( 2020 ). He highlights that financial service companies are now being provided by non-deposit taking contenders. This paper addresses one of the four research questions raised by his review, namely how theories of financial intermediation can be modified to accommodate banks, shadow banks, and non-intermediated solutions.

To be a bank, an entity must be authorized to accept retail deposits. A challenger bank is, therefore, still a bank in the traditional sense. It does not, however, have the costs of a branch network. A peer-to-peer lender, meanwhile, does not have a deposit base and therefore acts more like a broker. This leads to the issue that this paper addresses, namely how the banks of the future will conduct their intermediation.

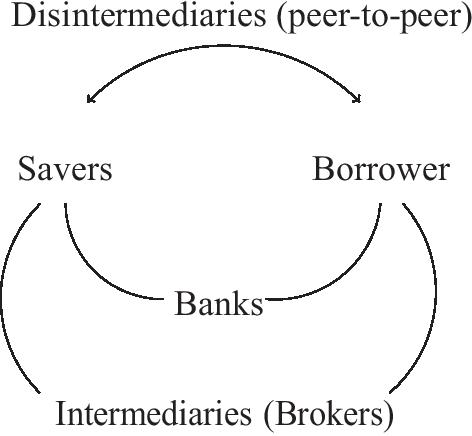

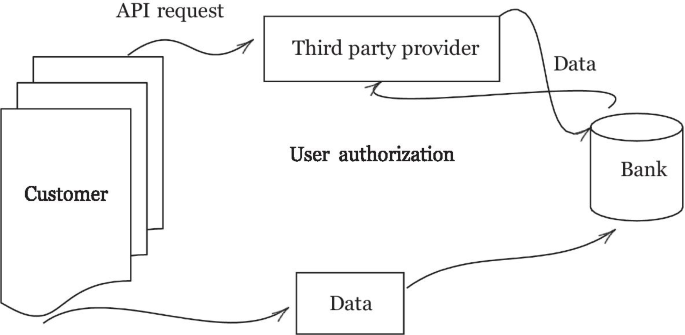

In order to understand what the bank of the future will look like, it is necessary to understand the nature of the aforementioned intermediation, and the way it is changing. In this respect, there are two key types of intermediation. These are (1) quantitative asset transformation and, (2) brokerage. The latter is a common model adopted by challenger banks. Figure 1 depicts how these two types of financial intermediation match savers with borrowers. To avoid nuanced distinction between these two types of intermediation, it is common to classify banks by the services they perform. These can be grouped as either private, investment, or commercial banking. The service sub-groupings include payments, settlements, fund management, trading, treasury management, brokerage, and other agency services.