Assignment - pronunciation: audio and phonetic transcription

American english:, [əˈsaɪnmənt] ipa, /uhsienmuhnt/ phonetic spelling.

Watch my latest YouTube video "Don't use a dictionary when you learn a language!"

Practice pronunciation of assignment and other English words with our Pronunciation Trainer. Try it for free! No registration required.

American English British English

Do you learn or teach English?

We know sometimes English may seem complicated. We don't want you to waste your time.

Check all our tools and learn English faster!

Add the word to a word list

Edit transcription, save text and transcription in a note, we invite you to sign up, check subscription options.

Sign up for a trial and get a free access to this feature!

Please buy a subscription to get access to this feature!

In order to get access to all lessons, you need to buy the subscription Premium .

Phonetic symbols cheat sheet

- Assignments

CS224S Assignment 1: Speech Systems and Phonetics

Spring 2024.

Time and Location

Mon. & Wed. 12:30 PM - 1:20 PM Pacific Time Jordan Hall room 040 (420-040)

Please read this entire handout before beginning. We advise you to start early and to make use of the TAs by coming to office hours and asking questions! For collaboration and the late day policy, please refer to the home page.

About the Assignment

In this assignment you will become familiar with some easily available spoken language processing systems and perform some basic analysis and manipulation of speech audio. The goal of this assignment is to familiarize yourself with some of the basic tools/libraries available and get you thinking about challenges in building spoken language systems.

Submission Instructions

This assignment is due on 04/15/2024 by 11:59PM pacific (or at latest on 04/18/2024 with three late days) and has three parts. For parts 1-2, you should submit a PDF to Gradescope and mark in the PDF which page corresponds to which question . For part 3, you will submit your filled-in/executed Colab Notebook with all code/output.

You will submit your materials for parts 1-2 and part 3 to Gradescope. Please tag your question responses.

Part 1: Speech APIs and Personal Assistants

For the first part of your assignment, you will be investigating the performance of popular speech transcription and personal assistant services. Your task will be to interact with three different speech systems, document your results, and describe the types of failures or issues you discover in the writeup.

Speech Transcription (10 points)

First, compose some short (2-4 sentence) emails or text messages using the speech input button on your mobile keyboard (usually in the email or messaging app). Try your best to limit yourself to “everyday” sentences and “optimal” conditions (no obscure vocabulary, low background noise, etc) to gauge how well the system could work at its best. Try composing messages that include different domain-specific words (e.g. machine learning jargon) or proper nouns (e.g. restaurant or actor names) to challenge the system.

- Paste the results for one message in your writeup including any errors the system generated.

- What is the rough number of errors per word in your results? We can count an error as anything you would manually correct before sending the message/email.

- Describe how the system handles punctuation. Does it guess, insert no punctuation, or allow punctuation commands?

- Try composing a message where you correct yourself (e.g. “I’m leaving at five – delete that I meant 6”). Include the resulting text and comment on how the system handles attempts to edit the utterance and to quickly correct partial words.

- Try to break the system . For instance, speak in a different pitch, volume, or distance to the microphone. Try talking with background noises. If you know a different language, try speaking in that language. Show 2 example utterances and describe what types of errors the system makes, along with what you did to cause those errors. Can you consistently produce different types of errors using different approaches to break the system?

Personal Assistants (10 points)

Use Siri, Google Assistant, Amazon Alexa or any kind of similar speech-based personal assistant. In this section, you will try to perform a few goal-oriented interactions and describe how the system handles your requests. For each of the below, include a description or screenshot of the interaction. Depending on what system you are using, try to describe the interaction or include a screenshot if possible (not necessary to provide a verbatim description)

- Ask some factual questions about a favorite book, show/movie, sports team. Is the system accurate in its responses? How does the system handle follow-on questions? (e.g. “Who wrote The Great Gatsby? … When was that book published?”)

- Pretend you are searching for a restaurant for take-out food today. Try to explore possible restaurants, learn about their ratings/food, and start an order if possible. How many turns did you take in this interaction (a turn in dialog is each time you speak)? Were you able to explore new places and learn about them? Was the interaction completely speech-driven, or does your assistant prompt you to look at options visually?

- Create some calendar events that involve a meeting name and add details (location, attendees, or similar). If you offer a lengthy initial command, does the system add all the details you specify? If you start with a simple “make a calendar event” prompt, what questions does the system ask?

- Using any of the above themes, try an interaction where you “barge in” to edit or correct something (barging in is talking while the system is talking to you). Does the system allow for you to barge-in for corrections? Does it detect that you had something to add while it was speaking?

- Describe any types of error you found while completing the tasks above. When the system didn’t achieve the result you hoped, can you attribute issues to limited functionality (e.g. not allowing calendar events to have notes attached), issues with speech recognition, or knowledge of concepts in the world?

Part 2: Phonetic Transcription

In this section you will do some basic creation and editing of phonetic pronunciations.

ARPAbet Transcriptions (20 points)

- three [dh r i]

- sing [s ih n g]

- eyes [ay s]

- study [s t uh d i]

- though [th ow]

- planning [p pl aa n ih ng]

- slight [s l iy t]

- action [ae k t ah n]

- tangle [t ae ng g l]

- higher [hh ay g er]

Part 3: Audio analysis toolkits

Audio analysis notebook (70 points).

Complete the exercises described in the Colab notebook provided via Google Drive folder . Turn in a PDF of your fully executed Colab notebook, showing the plots you created. Remember to make a copy of the Colab notebook before you start working so changes will save!

| ELT Concourse teacher training |

- ELT Concourse home

- A-Z site index

- Teacher training index

- Teacher development

- For teachers

- For trainers

- For managers

- For learners

- About language

- Language questions

- Other areas

- Academic English

- Business English

- Entering ELT

- Courses index

- Basic ELT course

- Language analysis

- Training to train

- Transcription

Transcription: a teach-yourself course

This guide also forms Strand 6 of the Teacher Development section.

This guide concerns transcription, not a description of the sounds of English. For a description of how the sounds of English are made and what mouth parts do, see the in-service guides to pronunciation (new tab). This course is:

- Firstly, a guide to teaching yourself to transcribe words in what are called their citation forms, i.e., the way they are pronounced when you ask someone to read a list carefully.

- Secondly, a guide to how things are pronounced in normal but not very rapid or mumbled connected speech.

- Thirdly, to provide you with some practice at transcribing what you read and what you hear (see the link at the end for the latter).

- Free. All materials on this site are covered by a Creative Commons licence which means that you are free to share, copy and amend any of the materials but under certain conditions. You may not use this material for commercial purposes. The material may be used with fee-paying learners of English but may not be used on fee-paying courses for teachers. Small excerpts from materials, conventionally attributed, may be used on such courses but wholesale lifting of materials is explicitly forbidden. There is, of course, no objection at all to providing fee-paying course participants with a link to this guide or any other materials on this site. Indeed, that is welcomed.

| The components of the course |

This is what the course covers. If you cannot transcribe or your transcription skills are shaky, do the whole course. If you are here for a specific area of transcription or returning for some revision, the following will help you find what you need. Clicking on -index - at the end of each section will return you to this menu.

| . American pronunciation |

The sounds transcribed here are generally those of an educated southern British-English speaker. That is not intended to imply that the dialect is somehow better than others. It is one of the conventional ways to do these things. American English pronunciation and any of the other multiple standard forms of the language would be different, especially but not solely, concerning the vowel sounds. Where there are significant differences (for example in the use of a rhotic or non-rhotic pronunciation) it will be noted.

There are teachers of English language who can lead successful careers in the classroom without ever using more than a minimal amount of phonemic transcription. Some use none at all. There are, however, six good reasons why knowing how to transcribe sounds is a useful skill for a teacher and knowing how to read transcriptions is a useful skill for learners. Here they are:

- For the teacher, the ability to transcribe what is heard allows rapid identification of troublesome sounds and other issues that need to be brought to the attention of learners. One can, of course, rely on a pronouncing or other form of dictionary to do the work but that is time consuming and not always possible. Freeing yourself from the need to consult a website or a dictionary for the pronunciation of words allows you to focus on what's important.

- For the learner, the ability to read the transcriptions of pronunciation in a dictionary, mono- or bi-lingual, gives autonomous access to how the word should sound without reference to the spelling or to a model. Many people, dazzled by the spelling, are unaware that, for example, no and know are identically pronounced or that the words right, rite and write also share a single pronunciation. By the same token, it may not at first be obvious that in the words troupe, bought, should, cough and tourist the combination of the letters o and u is differently pronounced in each case. It is, of course, possible for the teacher to model the pronunciations in the classroom but the ability to note them down in phonemic script is a valuable learning tool.

- Systematicity Phonemic transcription is independent of the language insofar as it is systematic. Many attempts have been made to spell English words phonetically but without some unambiguous system of symbols such attempts fail. Unless we can rely on a generally accepted system, there is, for example, no easy way to show the pronunciation of diphthongs and the difference between long and short vowels without resorting to a range of odd and obscure marks over letters such as ç, â, œ and so on. Having a single system works.

- Reliability As you may know, spelling in English is not a reliable guide to how a word is pronounced so, even if a learner can correctly recognise and produce the different pronunciations of the o in love and move that is not a guide to knowing how shove or hove are pronounced at all. Access to the phonemic script allows learners instantly to relate the pronunciation of words to one another and not to pronounce hove as if it rhymed with love or shave as if it rhymed with have . Teachers who can transcribe have the ability to make this clear and learners who can read transcription are able to make a note of the difference.

- Ambiguity Even when words are spelled the same, they may be differently pronounced (a phenomenon known as homography) so we get, for example, entrance meaning a way in and a verb meaning bewitch or hold someone's complete attention . The words are very differently pronounced. Other examples will include row, minute, live and hundreds more. Being able instantly to spot the difference is a skill learners need to develop if they are sensibly to use a dictionary and teachers need instantly to point out when teaching. The best way to do that is via phonemic transcription.

- Professionalism The ability to use a simple, if technical, area of linguistics is an indicator of professional competence. An inability to read or write a transcription of how something is pronounced is a handicap when it comes to teaching pronunciation and most learners expect formal pronunciation work to be part of what happens in the classroom.

- Correction and needs analysis The ability to transcribe how learners pronounce certain phonemes and words is helpful when it comes to researching the needs of your learners. Having a transcription of what they actually produce next to a transcription of what they should produce helps you to identify what needs work and what is adequate. For learners, too, a transcription of what they say and the model to compare it to helps them to notice the gap.

If even some of that sounds convincing, read on.

We are talking about English sounds here. The study of language sounds (phonemic analysis) is language specific . This mini-course is concerned with the transcription of English sounds. You will not, therefore, find mention of the vowel /ɯ/ (which occurs in Turkish, Korean, Irish and many other languages) or /ɾ/ which is the Spanish trilled /r/ sound that does not appear in English but is common in, e.g., Japanese and other languages. The chart below does not, therefore, describe all the sounds of language, just the ones that are used in English (and not all of them as we shall shortly see).

| words | transcriptions |

| /hʌt/ /bʌt/ /ʃʌt/ /mʌt/ /dʒʌt/ /let/ /set/ /met/ /ˈbet/ /ˈdʒet/ |

| words | transcriptions |

| /ˈmʌð.ə/ /ˈmʌ.tə/ /ˈlɪ.və/ /ˈlɪ.tə/ /spend/ /spent/ /ruːf/ /ruːt/ |

| words | transcriptions |

| /bəʊt/ /buːt/ /ˈbɔːt/ /baɪt/ /bɪt/ /beɪt/ /ˈbɑːt/ /bʌt/ |

- the sound /t/ can be pronounced with and without a following /h/ sound Compare the sounds in track and tack In the first, when the /t/ is followed by another consonant, the sound is without much aspiration (transcribed as /t/) but in the second, the sound is aspirated and transcribed as /tʰ/. In English, these sounds are not phonemes because you can change /t/ to /tʰ/ without changing the meaning of a word. In some languages, Mandarin, for example, /t/ and /tʰ/ are separate phonemes and swapping them around will change the meaning of what you say.

- The same applies to /k/ vs. /kʰ/ ( ski vs. cat ). When /k/ is not the first sound in the word, it lacks much aspiration but when it is the first sound, or, like /t/ when it is the first sound of a syllable, it carries the aspiration and is transcribed that way.

- The sound /p/ exhibits the same characteristic. Make it the first sound in a word or a syllable, such as in copper and it will be aspirated to /pʰ/.

- the light [l] as in lap which is simply transcribed as /læp/ with the sound pronounced with the tongue tip on the alveolar ridge behind the top teeth. This pronunciation occurs when /l/ is followed by any vowel sound so pull it is transcribed as /pʊl.ɪt/.

- the dark version (which has the symbol [ɫ]) and occurs at the end of words like full , transcribed as [fʊɫ] with the tongue further back in the mouth approaching the velum or soft palate. The sound is referred to, incidentally, as velarised. The pronunciation is used when /l/ is not followed by a vowel so pull that is transcribed as /pʊɫ.ðæt/. The transcription may safely be left as /l/ in all cases because it is simpler and we have a rule for the pronunciation of the allophones.

- in Standard British English, the word nurse is transcribed with a long vowel (as /nɜːs/) but in rapid speech the vowel may be shortened to give /nɜs/. No-one listening will mistake the word or assume that the word with a shorter vowel carries a different meaning so the transcription need not distinguish too carefully. The sounds are allophones. In Standard American English the word is transcribed as /ˈnɝːs/ with the tiny /r/ denoting that the 'r' sound is pronounced by most American-English speakers but, again, that is an allophonic, not phonemic, difference because the word remains the same with the same meaning. In some varieties of British English, too, the /r/ will be pronounced so we will have /nɜːrs/ as the transcription.

- the words beauty and booty may be pronounced identically as /ˈbuː.ti/ although the standard form for beauty is /ˈbjuː.ti/ and for booty , it is /ˈbuː.ti/. It makes no difference to meaning if your dialect does not distinguish.

For a list of useful minimal pairs (for your own practice and use in the classroom, click here (new tab).

Click here to take a short test to see if you can match minimal pairs. There are no transcriptions in this test so you will have to say the words aloud or to yourself to find the pairs. You can click on the other answers to see what feedback you get.

Here's the list you'll learn. If you want to download this chart as a PDF document to keep by you as reference, click here .

The symbols we are using in the course are those introduced by Gimson (1962) in the first edition of An Introduction to the Pronunciation of English .

The consonants are the easiest so we can start there. Most of them are transcribed using the normal letters of the alphabet and they are often the same as the written form of the letter but remember that spelling in English is not a reliable guide to pronunciation. There are five sounds which are denoted by special symbols and these you have to learn:

- /ʒ/ which is the sound represented by the letter 's' in plea s ure (/ˈple.ʒə/)

- /ʃ/ which is the sound represented by the letters 'sh' in sham (/ʃæm/)

- /θ/ which is the sound represented by the letters 'th' in thank (/θæŋk/)

- /ð/ which is the sound represented by the letters 'th' in mother (/ˈmʌð.ə/)

- /ŋ/ which is the sound represented by the letters 'ng' in ring (/rɪŋ/)

Additionally, there is one anomaly and two combination consonant sounds:

- /j/ is not a representation of the sound at the beginning of jug but is the sound which the letter 'y' represents in young (/jʌŋ/)

- /dʒ/ is a combination of /d/ and /ʒ/ and is the sound represented by the letter 'j' in jump (/dʒʌmp/)

- /tʃ/ is a combination of /t/ and /ʃ/ and is the sound represented by the letters 'ch' in chat (/tʃæt/)

| Voicing |

Voicing describes how phonemes may be different depending on whether the vocal cords vibrate or not at the time of pronunciation. (There are those who will aver that the technically correct term is vocal folds not vocal cords.) Voicing is also called sonorisation. For example, the /k/ sound is made without voicing but the /ɡ/ sound is made with the mouth parts in the same place but with voice added. Here are some examples of words containing voiced and unvoiced consonants. The consonant in question is underlined, in bold . Say them aloud and you will hear the differences.

| Unvoiced | Say: | |

| apanese | ap | |

| e | e | |

In all the words above, the place of articulation (i.e., where in the mouth the sound is made) is identical for both pairs of consonants. All that changes is whether or not the vocal cords or folds vibrate. If you put your hand on your throat and say the words sue and zoo , you will see what is meant and feel a slight vibration on the second word (/s/ is unvoiced but /z/ is voiced). Try saying the words and examples in the table above out loud and you will see that you need to pronounce the voiced consonants with a vibration of the vocal cords and a little more energy than the sounds in the unvoiced cases. A check is to try saying ZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSS with a hand on your throat so you can feel the vibration.

Of the consonants, 16 form pairs of voiced-unvoiced sounds:

| Unvoiced | Minimal pairs | |

| /p/ | ||

| /tʃ/ | ||

| /f/ | ||

| /s/ | ||

| /k/ | ||

| /t/ | ||

| /θ/ | (plural noun) (verb) | |

| /ʃ/ |

You have to listen out for voicing when you are transcribing because voiced and unvoiced consonants are full phonemes in English. There is, in fact, a cline between fully unvoiced phonemes and those which are heavily voiced but for the purposes of a phonemic rather than phonetic transcription, we simply have to draw a line and have unvoiced and voiced consonants on either side of it. Individual speakers, too, vary in the amount of voicing they exhibit and in which consonants they voice in which environments. For more, see the section below under assimilation concerning voicing and devoicing.

Click here for a little test to see if you can match voiced and unvoiced sounds by saying some words aloud.

To get us started with transcribing consonants, take a piece of paper and transcribe the consonants only in these words, using the right-hand side of the phoneme chart. Look at the example words and check to see if the pronunciation is the same as the words in this test. Click on the table when you have done that.

| Given here is a full transcription but you can ignore the vowels (for now). You should have noticed these things: both the 'c' and the 'k' are transcribed as /k/. both the 'j' and the 'dg' are transcribed as /dʒ/. This is how the 'j' is usually pronounced but the /j/ is the one at the beginning of . is different from the 'th' in . The first is unvoiced, the second voiced so they are transcribed as /θ/ and /ð/. is transcribed as /s/ not as in , of course. is voiced so it is transcribed as /z/. It is a different sound from the beginning of . is actually pronounced as 'sh' so it is transcribed as /ʃ/. is not pronounced like that. It is transcribed as /ʒ/. That is not the same as the /z/ at the end of . is the same as the 'c' in . and are both nasalised and transcribed as /ŋ/. Compare them to the 'n' in . |

All the other sounds are transcribed using ordinary English alphabetic letters taking on their usual pronunciation.

Now transcribe the underlined CONSONANTS only in these words. Do not worry now about the rest of the words.

| ToBaCCo | CHair | JuMP | BaFFLe | VaN | BaDGe | DaDDy | PaTH | THiS | MaZe | SHaVe | HaNG | HuLL | RaBBLe | Way | YaNK |

You should have:

| tobacco | chair | jump | baffle | van | badge | daddy | path | this | maze | shave | hang | hull | rabble | way | yank | |

| /t/ + /b/ + /k/ | /ɡ/ + /ɡ/ +/l/ | /tʃ/ | /dʒ/ + /m/ + /p/ | /b/ + /f/ + /l/ | /v/ + /n/ | /b/ + /dʒ/ | /d/ + /d/ | /p/ + /θ/ | /ð/ + /s/ | /m/ + /z/ | /ʃ/ + /v/ | /h/ + /ŋ/ | /h/ + /l/ | /r/ + /b/ + /l/ | /w/ | /j/ + /n/ + /k/ |

If you have included an /r/ sound at the end of your transcription of the word chair , that's fine because it would be pronounced that way if the following sound were a vowel. If not, in BrE the /r/ is not included but it is in many other varieties of English including AmE .

As a very simple check, try these three tests which just ask you to match the transcription of the consonant with a word containing only that consonant. If you would like to try an exercise in transcribing the consonants you hear rather than ones you read, click here (new tab).

The pronunciation of /w/ If you are transcribing the speech of someone from Scotland, Ireland or parts of the southern United States, listen out for how, for example, they pronounce the initial consonant on where, when, whether, whine, what etc . Although the sound is now almost extinct except in some varieties, a variant of /w/ usually transcribed as /hw/ (or you may see it as [ʍ]), appears at the beginning of words spelled wh- but has for almost all speakers of English now merged with /w/. The result is that apart from a small minority of speakers, there is no distinction in pronunciation between weather and whether, wine and whine etc. The merger is generally called the whine-wine merger.

Here's a list of the vowels in English (authorities may differ slightly about how many there are, incidentally).

| /iː/ | sleep sheep free | /æ/ | sat hat flab | /ɪə/ | here beer mere |

| /ɪ/ | kid slid blip | /ʌ/ | blood cup shut | */ʊə/ | d ring f rious poor |

| /ʊ/ | put foot suit | /ɑː/ | part large heart | /ɔɪ/ | boy depl toy |

| /uː/ | goose loose Bruce | /ɒ/ | hot cot shod | /eə/ | lair share pr yer |

| /e/ | Fred dead said | †/i/ | happ navv sall | /eɪ/ | lace day betr |

| /ə/ | bout fath cross | /aɪ/ | price wine shine | ||

| /ɜː/ | verse hearse curse | /əʊ/ | boat coat note | ||

| /ɔː/ | fought caught brought | /aʊ/ | south house louse | ||

* This diphthong in the example words is not pronounced by all speakers. For example, sure may be pronounced with the diphthong as /ʃʊə/ or with a monophthong as /ʃɔː/ † /i/ may be transcribed as /iː/ in some analyses. The schwa (/ə/) is the commonest sound in English but there is no letter for its representation.

The first two columns contain the 13 pure vowels in English. The right-hand column contains the 8 diphthongs making a total of 21 in all.

If you haven't already done so, to do this exercise, you may want to download the chart as a PDF document so you can have it at your elbow. Click here to do that .

Using the chart, transcribe the following words and then click on the table to check your answers.

If you didn't get the final vowel of ago , or the first one of happy , that doesn't matter (yet). In the first case the initial vowel was the schwa , transcribed as /ə/, and in the second case, the final vowel is transcribed as /i/ and lies between the short vowel in sit (/sɪt/and the longer one in seat (/siːt/). Try another short recognition test by clicking here .

There are 8 of these and they are combinations of pure vowels which merge together. We have, e.g., /ɪ/ + /ə/ (the sounds we know from bid and ago ) following one another to produce /ɪə/ as in merely (mee-err-ly). You can usually work out what the diphthong is by saying the word it contains very slowly and distinctly.

There is another test of your ability to recognise all the diphthongs here .

An issue to note is with the transcription here of tour. Here, we use the diphthong /ʊə/ but there are many speakers who pronounce, especially, short words such as sure, poor etc. with the monophthong /ɔː/ so, for example, sure as /ʃʊə/ or with a monophthong as /ʃɔː/, poor / pour as /pʊə/ or with a monophthong as /pɔː/ and tour as /tʊə/ or with a monophthong as /tɔː/. This sound is more often present in longer words such as individ ua l (/ˌɪn.dɪ.ˈvɪ.dʒʊəl/). If you are being careful to transcribe exactly what someone says, this is worth listening out for.

Finally, there is a set of three tests of your ability to recognise some commonly confused vowel transcriptions. Click here to go to it (new tab).

You have now transcribed words using all the vowels and consonant sounds of English.

As a check of your knowledge, try the following.

Did you get it right? One thing to notice is that in rapid connected speech, the transcription of come with me would probably be /kʌm wɪ miː/ without the /ð/ because we usually leave it out. You may also, depending on how you say things, have had /iɡ's/ or even /ik's/ at the beginning of exactly . That doesn't matter too much but note the convention for marking the stress on multisyllabic words: it's a ' inserted before the stressed syllable. There is also the convention of putting a stop (.) between syllables (as in, e.g., sentence ('sen.təns). Your students may not need that but many find it helpful. More on that in a moment.

The most common vowel in the spoken language has no letter to represent it. It is, of course, the humble schwa. If you teach no other phoneme symbol, teach this one. Including it in your transcriptions is simply a matter of listening out for it and making sure that you aren't being influenced by the spelling of words. You should also note that the schwa only occurs in unstressed syllables . You can't stress the schwa. The schwa may be how any of the traditionally spelled vowels are pronounced:

| vowel | a schwa in | transcribed |

| a | / .'sliːp/ | |

| e | /'dɪ.fr nt/ | |

| i | /'de.fɪ.n t/ | |

| o | /'prɒ.s .di/ | |

| u | /'tiː.dɪ m/ | |

| ou | /'tiː.dɪ s/ | |

| io | /'neɪʃ. n/ |

How many schwa sounds can you detect when you say and transcribe this sentence? Click on the bar when you have an answer.

No fewer than 12 in 11 words. Note:

- The last bits of the words celebration and official are known as syllabic consonants . That is to say, there is no proper vowel sound between the /ʃ/ and the /l/ in official and between the /ʃ/ and the /n/ in celebration . Other examples are table , doable and so on where there is no proper vowel between the /b/ and the /l/. Some transcriptions would remove the schwa, transcribing them as /ə.'fɪʃ.l/ and /se.lə.'breɪʃ.n/. An alternative is to insert a raised schwa for these very short vowels (e.g., /ˌse.lə.ˈbreɪʃ.ᵊn/). A third alternative you may see is to place a dot below the final consonant to indicate the pronunciation, using, e.g., /l̩/ and /n̩/. You choose but be consistent with your learners. There is more on this below in the bit about crushing the schwa. (Many would omit or use the raised symbol in a word like simple (/'sɪm.pl/ or /'sɪm.pᵊl/), but the comparative form, simpler , is pronounced with nothing between the two consonants (/'sɪm.plə/). In simple , the /l/ is dark ([ɫ]), in simpler , it is light.)

- The first incidence of the definite article is not transcribed with a schwa because it is followed by a vowel sound (so it's pronounced /ði/). The rules for article form and pronunciation (especially before /h/) are not simple and are set out in the guide to them here (new tab).

- You may have preferred to have the second vowel sound in celebration as /ɪ/ rather than the schwa and that just depends on your preferred pronunciation.

- The syllables containing the schwa are all unstressed.

As a check, we'll look again at an exercise from the section on consonants and ask you to try the test again but this time, transcribe the whole of each word, putting in the correct vowel transcriptions, the stress marks and the schwa. Here's the list again:

| /tə.ˈbæˌko.ʊ/ | /ˈɡuː.ɡl̩/ | /tʃeə/ | /dʒʌmp/ | /ˈbæf.l̩/ | /væn/ | /bædʒ/ | /ˈdæ.di/ | /pɑːθ/ | /ðɪs/ | /meɪz/ | /ʃeɪv/ | /hæŋ/ | /hʌl/ | /ˈræb.l̩/ | /ˈweɪ/ | /jæŋk/ |

You may have transcribed three of these words slightly differently. They are:

- Google : which can be transcribed either as /ˈɡuː.ɡl̩/ or as /ˈɡuː.ɡəl/

- baffle : which can be transcribed either as /ˈbæf.l̩/or as /ˈbæf.əl/

- rabble : which can be transcribed either as /ˈræb.l̩/ or as /ˈræb.əl/

The reason for this is that the final syllable is so short that most people do not pronounce the schwa at all in rapid speech and instead produce what is known as a syllabic consonant which is transcribed as /l̩/ with a mark below the phoneme to show that it is a syllable in its own right. There is more on this below. Be patient. By the way, if you transcribed chair as /tʃeər/, that's OK, too, because it would be pronounced that way if the following sound were a vowel. If not, in BrE the /r/ is not included but it is in many other varieties of English including AmE. The usual way to transcribe the word in AmE is as /ˈtʃer/.

Now you can get a little practice in transcribing the vowels you hear in some simple words. Click here to do that.

There are those who argue (Wells, for example) that there is actually no such thing as a triphthong in English. They take the view, roughly summarised, that the vowels in, e.g., player break into two syllables so what we have is simply a diphthong followed by another vowel so the transcription should be: /ˈpleɪ.ə/, not /ˈpleɪə/ and that means the diphthong /eɪ/ as in day followed by the schwa in the second syllable. Wells puts it like this:

I would argue that part of the definition of a true triphthong must be that it constitutes a single V unit, making with any associated consonants just a single syllable. Given that, do we have triphthongs in English? I claim that generally, at the phonetic level, we don’t. I treat the items we are discussing as basically sequences of a strong vowel plus a weak vowel. Wells, 2009

Roach, on the other hand, argues differently and states that:

The most complex English sounds of the vowel type are the triphthongs. They can be rather difficult to pronounce, and very difficult to recognise. A triphthong is a glide from one vowel to another and then to a third, all produced rapidly and without interruption . Roach, 2009:29 (emphasis added)

Crystal, states:

The distinction between triphthongs and the more common diphthongs is sometimes phonetically unclear. Crystal, 2008:497

This is not the place to pit two esteemed phoneticians against each other so we'll stick with the simplest explanation, the one proposed by Wells, and suggest that what is sometimes called a triphthong is, in fact a glide from a diphthong to another vowel, the schwa and that there are (or can be) two syllables in such pronunciations. Here, we will recognise five of these combinations of sounds. Whether whomever you are transcribing produces all five is a matter of the accent and background of the speaker as well as how carefully and slowly the words are spoken. Here's the list:

- /eɪə/ as in player (/ˈpleɪər̩/) or mayor (/ˈmeɪər/. Start with the diphthong /eɪ/ as in say (ˈseɪ/) and glide from the end of that to the /ə/.

- /aɪə/ as in liar (/ˈlaɪər/) or shyer (/ˈʃaɪər/). Start with the diphthong /aɪ/ as in nice (ˈnaɪs/) and glide to the /ə/.

- /ɔɪə/ as in soil (/ˈsɔɪəl/) or loyal (ˈlɔɪəl/). Start with the diphthong /ɔɪ/ as in toy (tɔɪ/) and glide to the /ə/.

- /əʊə/ as in lower (/ˈləʊ.ə/) or knower . (/ˈnəʊ.ə/ This one has a schwa at both ends. Start with the diphthong /əʊ/ as in coat (/kəʊt/) and glide to the /ə/.

- /aʊə/ as in tower (/ˈtaʊər/) or our (/ˈaʊər/. Start with the diphthong /aʊ/ as in mouth (/ˈmaʊθ/) and glide to the /ə/.

You should have: mower : /ˈməʊə/ or /ˈməʊ.ə/ tyre : /ˈtaɪə/ or /ˈtaɪ.ə/ slayer : /ˈsleɪə/ or /ˈsleɪ.ə/ toil : /ˈtɔɪəl/ or /ˈtɔɪ.əl/ (but many pronounce that as /tɔɪl/, a single-syllable word with a diphthong vowel sound) shower : /ˈʃaʊə/ or /ˈʃaʊ.ə/

As far as transcription is concerned, you do not have to take sides in the Roach-Wells debate and can equally well have the transcription with the syllable-marking '.' or without. It just depends on whether you hear the sound as a single vowel or two syllables and that will vary from speaker to speaker. See the next section for how we recognise syllables.

As we saw, the main stressed syllable is conventionally indicated by ' before the syllable (e.g., /'sɪl.əb.l̩/). It is sometimes helpful to mark secondary stress in longer words like incontrovertible by a lowered symbol like this: /ɪn ˌ k.ɒn.trə.'vɜː.təb.l̩/ in which you can see a small ˌ before the /k/ sound indicating that the second syllable carries secondary stress and the main stress falls on the fourth syllable and is shown by the 'vɜː in the transcription. Most learners find just one stressed syllable enough to cope with. If we want to show that non-phonemically, we might write: in con tro VER tible on the board with an underline lower-case for secondarily stressed syllables but bold, underlined CAPITALS for the main stress. (An alternative way to mark stress sometimes used by professional phoneticians is to place an acute accent over the onset vowel of a stressed syllable and a grave accent over a secondarily stressed item. In this case, the syllable borders are usually ignored.)

However, before we can decide where to put the stress mark, we need to identify the syllables in an utterance. That is not always as easy as it sounds. A syllable is a unit of pronunciation having one vowel sound, with or without surrounding consonants . By that definition, all of the following are single syllables: or go ask bus of various kinds (there is a guide to the difference on this site which you can access in the guide to syllables and phonotactics (new tab)). You can transcribe these individual words without any stress or syllable marks because there is no stress to note and only one syllable in question. In connected speech, of course, we may need to insert a stress mark if the word carries stress in a longer string of text. The transcription of those words is, therefore: or: /ɔː/ go: /ɡəʊ/ ask: /ɑːsk/ bus: /bʌs/ and there are no other markings.

However, words or utterances of more than one syllable pose a problem because the transcription needs to show both the division into syllables and the place where the stress appears.

You should have: There are 7 syllables so the word is broken down as de-na-tio-na-li-za-tion . The transcription is: /ˌdi:.ˌnæ.ʃə.nə.laɪ.ˈzeɪʃ.n̩/ In rapid speech, however, many speakers will omit some of the syllables in very long words so the transcription might easily be: /ˌdi:.ˌnæʃ.nə.laɪ.ˈzeɪʃ.n̩/ with the third syllable dropped. Notice, too, that the final syllable in both cases is simply /n̩/ which denotes that there is no obvious vowel between the /ʃ/ and the /n/ sounds. That's called a syllabic consonant because the single consonant forms a syllable. If you transcribed that with /ən/ at the end, that's fine (and correct). It can also be transcribed as /ᵊn/ to show that the vowel is very short. There is a bit more on syllabic consonants below.

The rules for deciding where a syllable starts and stops are quite complex in English but there is a rule of thumb we can use to decide, for example, how to divide a word like tumbler . We could have: /ˈtʌm.blə/ or /ˈtʌ.mblə/ or /ˈtʌmb.lə/ so how do we decide? Here are the rules:

- If there is a choice, attach the consonant to the right-hand syllable, not the left: That would mean that the transcription would be: /ˈtʌm.blə/ and that's fine, but why don't we attach both consonants to the right-hand syllable and it isn't: /ˈtʌ.mblə/? Here, we need rule 2:

- If attaching the consonants to the right-hand element produces a syllable which is forbidden as the beginning of a word in English, move one of them to the left. In English, no word can begin /mb/ (although that is allowable in some languages). We can, however, have a word beginning /bl/, of course, such as black, blur, block etc. Therefore, applying both rules, we end up with /ˈtʌm.blə/

Now the stress marking. Once we have applied the rules (or used a bit of common sense and intuition) we can divide multisyllabic items up conventionally and then decide where the stresses fall.

You should have: /ɪm.ˌpɒ.sə.ˈbɪ.lɪ.ti/ and /ˌɪnt.ə.ˌnæʃ.n̩.əl.aɪ.ˈzeɪʃ.n̩/ We cannot, of course, following Rule 2 above have /ɪ.ˌmpɒ.sə.ˈbɪ.lɪ.ti/ or /ˌɪnt.ə.ˌnæ.ʃn̩.əl.aɪ.ˈzeɪʃ.n̩/ because no word in English can begin with /mp/ or /ʃn/ so we move the /m/ and the /ʃ/ to the left and then we have something acceptable. Do not worry if your transcription was not exactly the same. If you have identified the syllable divisions and put the main and subsidiary stresses in the right places, that's OK for now.

Transcribing connected speech spoken at normal speed rather than someone reading from a list of words, requires the inclusion of a variety of new factors. Four are considered here.

| Intrusive and linking sounds |

There are three sounds which speakers insert between vowels in connected speech. They need to be included in your transcriptions. They are:

You may see an intrusive sound put in superscript ( rwj ) and that's a good way to draw your learners' attention to the sounds. There is, however, a case to be made that you don't have to teach these at all because they are the inevitable effects of vowel-vowel combinations in speech. They aren't, of course, only applicable to English.

Try this next mini-test. Click on the table to get the answer.

There are times when you have to listen extremely carefully to hear whether a speaker is actually producing the intrusive sound or inserting /ʔ/, a glottal stop (see next section). For example, many will pronounce Go out as /gəʊʔaʊt/ rather than /ɡəʊ.ˈwaʊt/, The gorilla and me as /ðə.ɡə.ˈrɪ.ləʔənd.miː/ rather than /ðə.ɡə.ˈrɪ.lə.rənd.miː/ and I am here as /ˈaɪʔæm.hɪə/ rather than /ˈaɪ.jæm.hɪə/.

As we saw above with the transcription of suet , many speakers of all varieties will insert an intrusive /w/ in the middle of the word, producing /ˈsuːwɪt/ instead of /ˈsuːɪt/ and so we also hear fuel as /ˈfjuːwəl/ but that word, even without the intrusive /w/ is pronounced with an intrusive /j/ as the transcriptions show. if you listen carefully to some British English speakers pronouncing words such as tune, fortune, produce, century, nature, mixture, picture, creature, opportunity, situation, actually you may hear an intrusive /j/ sound after the /t/ or /d/ not shown in the spelling. Therefore, the transcription is actually: tune /tjuːn/ actually /ˈæk.tjuə.li/ situation /ˌsɪ.tjʊ.ˈeɪʃ.n̩/ etc. although ˈæk.tʃuə.li/ and /ˌsɪ.tʃʊ.ˈeɪʃ.n̩/ are also heard. Not all speakers do this.

A further issue to listen for is the linking /r/ sound. In British English, the final 'r' on many words is unsounded so, for example, harbour is pronounced as /ˈhɑː.bə/, whereas in AmE, the standard pronunciation includes the /r/ sound and the pronunciation is /ˈhɑːr.bər/. However, when a word ending in 'r' immediately precedes a word with an initial vowel, we get the linking /r/ and the sound is produced so, for example: My father asked will be pronounced as /maɪ.ˈfɑːð.ər.ˈɑːskt/ in BrE and as /maɪ.ˈfɑːð.r̩.ˈæskt/ in AmE.

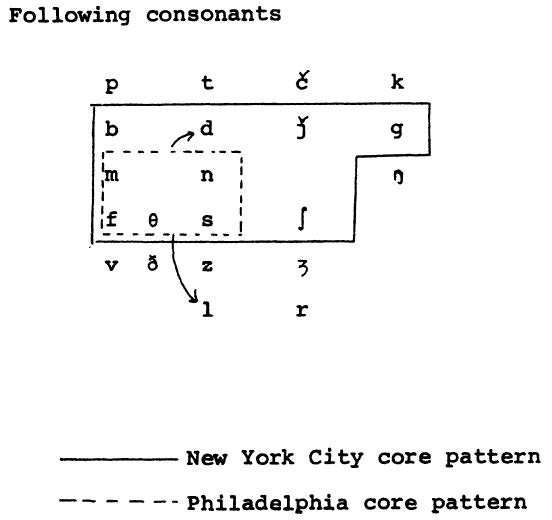

The guide to connected speech contains more detail on the different forms of assimilation. For the purposes of transcribing sounds in connected speech, the various types are not as important as the ability to step away from the written word and transcribe only what you hear. You must be aware, however, that not all speakers will pronounce everything the same way and the phenomena listed here are not consistently produced by everyone. Much will depend on how careful speakers are and what variety of English they use. Assimilation describes the alteration of sounds under the influence of other sounds in the vicinity. The guide to connected speech has this table:

| Before these sounds | this sound | assimilates to | for example | transcription |

| /m/, /b/, /p/ | /n/ | /m/ | /ðem.ˈbeɪk.ɪt/ | |

| /ðemˈpʊt.ɪt/ | ||||

| /ðem.ˈɪks.ɪt/ | ||||

| /t/ | /p/ or /ʔ/ | /ðəʔ.ˈmɪks.tʃə/ | ||

| /ðəp.bred/ | ||||

| /ðəʔ.ˈpeɪ.pə/ | ||||

| /d/ | /b/ or /ʔ/ | /ˈmæʔ.mæn/ | ||

| /ˈmæʔ.ˌbɔɪ/ | ||||

| /mæb.ˈɒ.lə.si/ | ||||

| /k/, /ɡ/ | /n/ | /ŋ/ | /ˈbiːŋ.keɪks/ | |

| /biːŋ.ˈɡʊd/ | ||||

| /t/ | /k/ or /ʔ/ | /ˈðəʔ.keɪk/ | ||

| /bək.ˈɡəʊ/ | ||||

| /d/ | /ɡ/ | /ˈbeɡ.kləʊðz/ | ||

| /j/ | /t/ | /tʃ/ | /ˈmaɪtʃu/ | |

| /d/ | /dʒ/ | /ˈhədʒu/ | ||

| /ʃ/ | /s/ | /ʃ/ | /ˈɡlɑː.ʃɒp/ | |

| /z/ | /ʃ/ | /hæ.ˈʃʌt/ |

In the last case, the assimilation of /s/ and /z/ to /ʃ/, some would aver that the /s/ and /z/ sounds are simply being omitted and that's elision, the topic of the next section. Others believe that the /ʃ/ sound is, in fact being extended to nearly double its usual pronunciation so this is a case of assimilation. The distinction, such as it is, is not vital for teaching purposes. Consonant lengthening is a minor area in English (but not so in some languages). There are times when two non-plosive consonants occur together and, normally in rapid speech, one of them is assimilated (or elided, depending on your point of view). So, for example: some milk is usually pronounced as /səm.ɪlk/ with only one /m/ sound. However, when people are being slightly more careful and speaking a little more slowly, both /m/ sounds are heard so the transcription is /səm.mɪlk/ and it would appear from that that there are two separate sounds in the middle of the phrase. What in fact frequently happens is not that we have two /m/ sounds but that we have a single sound slightly lengthened. The transcription is sometimes adjusted to take this into account and a length mark is inserted after the consonant so we get the transcription as /səmː.ɪlk/. The phenomenon is called gemination (from the Latin gemini , meaning twins). This sort of lengthening occurs most frequently with certain consonants because plosives such as /p/ cannot usually be lengthened. Some examples are: club bar /klʌb.bɑː/ mad demons /mæd.ˈdiː.mənz/ safe fire /seɪf.ˈfaɪə/ big gate /bɪɡ.ɡeɪt/ full label /fʊl.ˈleɪb.l̩/ warm margarine /wɔːm.ˌmɑː.dʒə.ˈriːn/ gin next /dʒɪn.nekst/ car research /kɑː.rɪ.ˈsɜːtʃ/ less sense /les.sens/ mash shop /mæʃ.ʃɒp/ cave visit /keɪv.ˈvɪ.zɪt/ and here we have followed the convention of transcribing both consonants although we are aware that in rapid speech one will not usually be sounded. If that is the case in what you hear, delete the second of the consonant sounds but retain the syllable marker. If you wish to use the length marker after the consonant, that's fine too, providing that it is what you heard, but be aware that it is not a widely used convention. In some languages, including Arabic, Danish, Estonian, Hindi, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Polish and Turkish, consonant lengthening carries meaning so a short or long consonant are independent phonemes. In English, no such meaning attaches to a longer consonant so we are dealing with allophonic differences and the transcription may be unaffected, therefore.

You should have: /ˈɡəʊl.dəm.bɒks/ /ˈtʃɪl.drəm.mʌst/ (or /ˈtʃɪl.drəm.mʌs/ with the elision of the final /t/ on must ) /ˈpʊt.paɪ/ or / ˈpʊʔ.baɪ/ /həʔ.ˈmæ.nɪdʒd/ With /n/ assimilated to /m/, /t/ to / ʔ / and /d/ to / ʔ/. Do not worry if your transcription was not exactly the same.

You should have: /faɪŋ.ˈkɑːs.l̩/ (with /ŋ/ not /n/) /sɪ ʔ .ˈkʌmf.tə.bli/ /həd.ˈ ɡ ʌ.vəd/ With /n/ assimilated to /ŋ/, /t/ to / ʔ / and /k/ to / ɡ/. Do not worry if your transcription was not exactly the same.

You should have: /peɪnʃ.ˈje.ləʊ/ /wʊdʒ.et/ With /t/ assimilated to /ʃ/ and /d/ to /dʒ /. Do not worry if your transcription was not exactly the same.

You should have: /le.ˈʃʊ.ɡə/ /wə. ˈ ʃʊə/ (or / wə. ˈʃɔːr/ depending on your accent) With /s/ assimilated to /ʃ/ (and lengthened, often) and /z/ also assimilated into a lengthened / ʃ/. Do not worry if your transcription was not exactly the same.

Voicing and devoicing

Assimilation, both progressive and regressive, also affects voicing (sometimes known as sonorisation). For example:

- the s following an unvoiced consonant will be pronounced as /s/ so we get hat and hats (/hæt/ and /hæts/), make and makes (/ˈmeɪk/ and /ˈmeɪks/) and so on.

- following a voiced consonant, however, s is usually voiced from /s/ to /z/ so we get rug and rugs (/rʌɡ/ and /rʌɡz/), cab and cabs (/kæb/ and /kæbz/) and so on.

- some speakers carry this over to other sounds, particularly the /θ/ and may pronounce, for example, baths as /bɑːðz/ and youths as /juːðz/. Others will retain the /θ/ in the plural forms. You simply have to listen out for which the speaker is doing.

- regressively, the /v/ in, for example, have is often devoiced before a voiceless consonant such as /t/ so the pronunciation of have to is /həf.tuː/ or /həf.tə/ and love camping is /ˈlʌf.ˈkæmp.ɪŋ/. Not all speakers do this and many retain the voiced /v/ in such expressions so, again, you have to listen for which variety the speaker is producing.

- a teaching point is that in some languages, German, Dutch, Polish and Russian, for example, a final consonant is always devoiced so, e.g., bag, club, has, had and cave may be pronounced as /bæk/, /klʌp/, /hæs/, /hət/, /keɪf/, respectively, instead of /bæɡ/, /klʌb/, /hæz/, /həd/ and /keɪv/. If you are transcribing learner English, that is something to listen out for.

It is important, too, to listen carefully for what is not pronounced and this also involves releasing oneself from the spell of the written word and hearing only what is being said, not what one expects to be said. Again, the guide to connected speech has more detail in this area but here it will be enough to present some examples:

- English uses a variety of contracted forms, leaving out whole sections of words ( hasn't, can't, wouldn't've etc.). You need to listen carefully to detect whether the speaker has used these or not (as, e.g., /ˈhæznt/, /kɑːnt/, /ˈwʊdnt.əv/ etc. There are other examples such as: the loss of the /d/ in sandwich (/ˈsæn.wɪdʒ/) the pronunciation of library as /ˈlaɪ.bri/, comfortable as /ˈkʌmf.təb.l̩/ or probably as /ˈprɒbli/.

- The initial /h/ sound is often dropped in rapid speech so, e.g.: Give it to him may be correctly transcribed as / ˈ ɡɪv.ɪt.tu.ɪm/.

- The initial vowel in if is often elided in conditional clauses so, for example: If I were you ... is pronounced as: /ˈfaɪ.wə.ju/

- Function words are often reduced. We saw above that the schwa often appears in reduced function words such as of, and, to and so on. Reduction also occurs, however, when all or part of a function word such as of is omitted as in, e.g.: cup of coffee being pronounced as cuppa coffee (/kʌpə ˈkɒ.fi/ In many cases the word and is reduced to 'n' and the /d/ is dropped as in, e.g.: tea 'n' cakes as /tiː n̩ keɪks/.

- Clusters of consonants are often simplified so, e.g.: sixths may usually be transcribed as /sɪkθs/ or even /sɪkfs/ and text message becomes /teks.ˈme.sɪdʒ/ and so on. More examples are in the guide to connected speech.

- Adjacent sound elision occurs frequently. When the sound at the end of one stretch of language is the same as the one at the beginning of the next item, they are usually reduced to a single sound in connected speech so, for example: I'm meeting Mary is pronounced as: /aɪ.ˈmiːt.ɪŋ.ˈmeər.i/ not /aɪm.ˈmiːt.ɪŋ.ˈmeər.i/ and Don't take that table is pronounced as /dəʊn.teɪk.ðæ.ˈteɪb.l̩/ not /dəʊnt.teɪk.ðæt.ˈteɪb.l̩/ In the transcription here, we have removed the first of the sounds but you can decide whether it is the first or the second which is elided. Speakers are not consistent in this and some will retain both sounds or, when it is possible, as with /m/ to extend the sound slightly. That is not possible with stops such as /t/, /k/ /d/ etc. but occurs with fricatives like /f/ and /s/ and with the nasal sounds. When it happens both phonemes appear in the transcription so, e.g., She makes sandwiches can be transcribed either as /ʃi.ˈmeɪk.ˈsæn.wɪdʒ.ɪz/ or as /ʃi.ˈmeɪks.ˈsæn.wɪdʒ.ɪz/

Again, speakers vary in this with some being more careful and correct and others less so (or sloppy as writers to newspapers often describe them). You have to listen hard to hear what is really being said.

You may have: /bæɡ.ə.pə.ˈteɪ.təʊz/, with the /v/ elided, or /bæɡ.əv.pə.ˈteɪ.təʊz/

You should have: /hi. ʃ ʊdnt.əv. ˈ b ɪ n.ðeə/ or /hi. ʃ ʊdənt.əv. ˈ b ɪ n.ðeə/ with the /ə/ included.

You should have either: /pɑːs. ˈ ðə.tə.hə/ or /pɑːs. ˈ ðə ʔ .tə.hə/ (with the assimilation of /t/ to / ʔ/). You may also have omitted the /h/ on her . If you transcribed that as /ðæ/ (with the full vowel sound and the elided /t/), that's OK, too. Many speakers, even when they are speaking quite quickly avoid the schwa for the vowel.

You could have either: /ˈsevnθs/ or /ˈsevns/ (with the elision of / θ /).

You could have either: /dʒɪm.meɪ/ or /dʒɪ.meɪ/ (with the elision of / m /).

At the back of your mouth there is a part of your larynx called the glottis and this is where the glottal stop is produced, hence its name. A glottal stop is formed by briefly blocking the airflow at the back of the mouth and then releasing it. The symbol for this sound is /ʔ/ and we have seen a lot of examples of how some sounds are replaced by the glottal stop above.

You probably have: /'pʊ ʔ ɒn/, / ' pɪ ʔ ʌp/ and / ' hɪ ʔ ɪm/ instead of the more careful forms of /'pʊt ɒn/, / ' pɪk ʌp/ and / ' hɪt ɪm/

We can have also butter as /'bʌ ʔ .ə/ not /'bʌt.ə/ or fatter as /ˈfæ ʔ .ə/ not /ˈfæ.tə/ in some common dialects (London and Scots, for example).

See also the use of the glottal stop to avoid a linking /r/, /w/ or /j/ sound, above.

Dropping the /h/ on him is not always sloppy speech; it is very commonly acceptable. And it is very common (but not in all dialects). The /h/ in I have, when not contracted, is often replaced by an intrusive /j/ as in /'aɪj æv/ and this happens frequently elsewhere, too ( they have, we have, e.g., rendered as /'ðeɪjəv/, /'wijæv/). Notice, too, the tendency to pronounce have as /həv/ in they have but as /hæv/ in we have . Hello is often pronounced /hə.'ləʊ/ sometimes /hæ.ˈləʊ/ but often /ə.'ləʊ/ or /æ.ˈləʊ/. It may be safer to stick with /haɪ/.

Similarly, in many dialects the final /ŋ/ in words ending with -ing is often rendered as /n/ but this is generally considered low status. We get, e.g., /'ɡəʊɪn 'aʊt/ instead of /'ɡəʊɪŋ 'aʊt/. Oddly, some high-status British accents also make this conversion, exemplified by the so-called huntin', fishin' and shootin' set (the /'hʌnt.ɪn 'fɪʃ.ɪn ən 'ʃuːt.ɪn set/).

You could have: /ˈdeɪ.zi.əz.ə.dɒɡ/ instead of the more careful /ˈdeɪ.zi.hæz.ə.dɒɡ/

You could have: /ə.ju.ˈɡəʊɪn.ˈaʊt.tə.ˈnaɪt/ instead of the more careful /ə.ju.ˈɡəʊɪŋ.ˈaʊt.tə.ˈnaɪt/ or even the very careful /ɑː.ju.ˈɡəʊɪŋ.ˈaʊt.tə.ˈnaɪt/

A rhotic dialect or variety of English is one in which the letter 'r' is pronounced as /r/ before a consonant or at the end of a word. For example, a rhotic accent, in this case General American is our example, will pronounce: card as /kɑːrd/ far as /fɑːr/ murder as /ˈmɝː.dər/ The symbol /ɝ/ is called an R-coloured or rhotic vowel. A non-rhotic variety such as BrE will pronounce those three words as /kɑːd/, /fɑː/ and /ˈmɜː.də/. The rhotic pronunciation is standard in American English and is becoming slightly more frequent in BrE, too. You sometimes need to listen hard to recognise whether an 'r' is being sounded in the middle of a word so, for example the AmE pronunciation of diversion is: /daɪ.ˈvɝː.ʒən/ whereas the BrE pronunciation lacks rhoticity: /daɪ.ˈvɜːʃ.n̩/. There are other differences, too, which are covered later. The symbol /ɝː/ to show the sound (a rhotic vowel) may also appear as /ɜːr/

We saw above that in most southern British dialects, the /r/ sound is only pronounced when the following sound is a vowel so we get, e.g.: My father asked pronounced as /maɪ.ˈfɑːð.ər.ˈɑːskt/ in BrE and as /maɪ.ˈfɑːð.r̩.ˈæskt/ in AmE. When the following sound is non-vocalic (not a vowel), this linking /r/ does not occur so, e.g.: My father told me is pronounced as: /maɪ.ˈfɑːð.ə.təʊld.miː/ in non-rhotic accents but as /maɪ.ˈfɑːð.ər.təʊld.miː/ in rhotic accents. In some speakers, the linking /r/ is avoided in favour of a glottal /ʔ/ (see above). In transcribing what is actually said, either by speakers of the language or by learners, it is important to be alert to whether the speaker is using a rhotic accent or a non-rhotic accent.

There are three influences which determine the use of a rhotic accent and using knowledge of them can help you to listen out when transcribing speakers' production.

- Geographical location As a rule of thumb, the following varieties of English are non-rhotic: Southern British English BBC English Welsh English New Zealand English (although there is some evidence of the influence of Scottish settlers contributing to rhoticity in some areas) Australian English Malaysian English Singaporean English South African English and English spoken elsewhere in Africa as a lingua franca Trinidadian and Tobagonian English and the following varieties are generally rhotic: Most varieties of Scottish English (although non-rhotic accents are common in Edinburgh and latterly in Glasgow) South West English and some varieties in and around Manchester, parts of Yorkshire and Lincolnshire and on the Scottish Borders Irish English American English Barbadian English Indian English Pakistani English Bangladeshi English.

- Social class and perceived status The status of rhotic vs . non-rhotic accents has a somewhat chequered history. In most varieties of British English a non-rhotic production is associated with high status dialects such as BBC English and rhotic varieties are confined to rural areas and the north. This is changing with an identifiable move towards rhotic varieties everywhere. The degree of rhoticity closely matches socio-economic class. In North America, the situation is more complex. Up until the end of the 19th century, a non-rhotic pronunciation was considered prestigious, especially in East coast cities such as New York and Boston. The American Civil War (1861-1865) and, arguably, the previous War of Independence (1775-1783), changed things, removing the prestige of r -dropping and, since the Second World War, a rhotic pronunciation has become a standard high-prestige accent in the USA. African-American Vernacular English retains the non-rhotic pronunciation but some speakers with Hispanic heritages may use a Spanish-influenced trill for the /r/. Canadian English is generally rhotic.

- Influences Many speakers of English as a second language will use a rhotic accent either because of the influence of AmE on their learning of the language or because their first languages are rhotic and they carry over the pronunciation of /r/ into English. For example, speakers of English who have Hindi or a Dravidian language as their first will often use a rhotic pronunciation in English but speakers of Cantonese (which lacks the /r/ consonant) will often use a non-rhotic pronunciation. Hence, for example, Hong Kong English is generally non-rhotic although the influence of American media and cultural issues are contributing to more rhoticity even there.

Varieties of /r/ sounds

In English, how the /r/ sound is produced is not semantically significant, the various pronunciations, therefore, heard in South West Britain, Ireland and Scotland etc. are allophonic not phonemic distinctions. Learners of English will, quite naturally, often carry over their native language pronunciation of /r/ into English and that contributes significantly to a foreign accent although it rarely interferes with communication. Here's a short list: In Spanish, the sole difference between pero ( but ) and perro ( dog ) is that in the former the 'r' is pronounced as a single flap (phonetically as [ɾ]) rather than trilled as it is in the latter like the Scottish [r]. Many languages, including Bulgarian, Swedish, Norwegian, Italian, Spanish, Russian, Polish, Ukrainian and Dutch use a similar trilled sound. French, European Portuguese and some German speakers may use a voiceless uvular fricative, phonetically [ʁ] which is produced by restricting the airflow over the back of the throat with the tongue. This is not so obvious if it occurs at all in many German dialects. Most Chinese languages, except Cantonese, use a retroflex sound, phonetically, [ɻ] in which the tip of the tongue is curled back but the situation is complex dialectically. This is not dissimilar, incidentally, to the sound as it is produced in South West Britain. Some languages, notably Thai and Japanese, do not distinguish phonemically between /r/ and /l/ so the production of 'r' and 'l' in English may be randomly one or the other.

If you listen very carefully to how someone pronounces a word like stable , you may hear two or three possible pronunciations:

- /ˈsteɪb.l̩/ or

- /ˈsteɪbəl/ or

The first is more likely to appear in quite rapid speech and the second sounds rather formal and slow. The third is an intermediate stage in which some people will hear a schwa but aver that it is simply shortened. That would be transcribed with the symbol for the schwa raised to signify its comparative shortness. What is happening is that the schwa between /b/ and /l/ is being crushed in normal rapid speech so that the final /l/ sound constitutes a syllable on its own. Usually, syllables are defined by vowels but, in this case, a consonant alone is the syllable because the schwa is all but impossible to hear. To transcribe this phenomenon, you need to place a dot before the syllable and insert a small mark below it to signify that it is a syllabic consonant (see above).

There are, in English, three types of syllabic consonant and they affect /l/ (the example above), /n/ and /r/. Here are some examples.

| /ˈkeɪ.pəb.l̩/ | |

| /dɪ.ˈfaɪ.nəb.l̩/ | |

| /kəm.ˈpjuː.təb.l̩/ | |

| /'ʌŋk.l̩/ |

| /ˈdɑːkən/ | or | /ˈdɑːk.n̩/ | |

| /ˈəʊ.pən/ | /ˈəʊp.n̩/ | ||

| /ˈdræ.ɡən/ | /ˈdræɡ.n̩/ |

| /ˌme.dɪ.ˈteɪʃ.ən/ | or | /ˌme.dɪ.ˈteɪʃ.n̩/ | |

| /ˌde.fɪ.ˈnɪʃ.ən/ | /ˌde.fɪ.ˈnɪʃ.n̩/ | ||

| /ɪk.ˈsep.ʃən/ | /ɪk.ˈsep.ʃ.n̩/ |

| /ɪn.ˈdɪ.fərəns/ | or | /ɪn.ˈdɪf.r̩əns/ | or | /ɪn.ˈdɪ.frəns/ | |

| /ˈbrʌð.ə/ | /ˈbrʌð.r̩/ | /ˈbrʌð.ər/ | |||

| /ˈre.və.rəns/ | /ˈrev.r̩əns/ | /ˈre.vrəns/ |

You could have: /ˈpæd.l̩/ /ˈfɪd.l̩/ /ˈduːə.b l̩ / /ˈlaɪt.n̩/ /ˈfɑːs.n̩/ /ˈtʃəʊ.zn̩/ but, of course, in more careful or slower speech, the / ə / will be inserted before a standard /l/ or /n/ instead of the syllabic /l̩/ or /n̩/. A New Yorker might produce: /ˈʃʌ.dr̩/ /ˈhʌn.tr̩/ /ˈdeɪn.dʒr̩əs/

Unlike individual sounds and issues of connected speech, there is no universally accepted or conventional way of transcribing intonation. In the classroom, most teachers develop their own ways of doing this depending on the features they want to highlight.

Whichever system or systems you adopt, you need to make sure that your learners understand its implications.

There is no exercise on this because

- you are free to choose, adapt or invent your own system

- people usually disagree about how the intonation actually works and

- there is simply no evidence that we can equate intonation to speaker emotion or intention on a simple one-to-one basis.

There are no arguments for teaching intonation in terms of attitude, because the rules for use are too obscure, too amorphous, and too easily refutable . (Brazil, D, Coulthard, RM, & Johns, C, 1980, Discourse Intonation and Language Teaching , Harlow: Longman, p120)

You are not advised to use both phonemic transcription and intonation diagrams together because that muddies the water and confuses your learners.

In the preceding, we have used transcriptions which seemed the most conventional and likely to be of some help in the classroom. As we noted, it is that introduced by Gimson (1962) in the first edition of An Introduction to the Pronunciation of English . There are, however, some alternatives to what has been used here that you may see, need to recognise or wish to use. Most commonly, the differences are between the transcriptions used here, those used by Daniel Jones (and refined by Gimson) and those used to transcribe the particular sounds of AmE. Here they are:

| Instead of ... | we can use ... | Used by or in |

| / / to enclose | | | to enclose | Anyone |

| /l̩/, /r̩/ and /n̩/ | /ᵊl/, /ᵊr/ and /ᵊn/ | Anyone |

| /ɪ/ | /i/ | Jones |

| /ɒ/ | /ɔ/ | Jones |

| /ʊ/ | /u/ | Jones |

| /e/ | /ɛ/ | AmE |

| /ʃ/ | /š/ | AmE |

| /ʒ/ | /ž/ | AmE |

| /tʃ/ | /č/ | AmE |

| /dʒ/ | /ǰ/ or /dž/ | AmE |

| /ɪə/ | /iə/ | Jones |

| /ʊə/ | /uə/ | Jones |

| /ɔɪ/ | /ɔi/ | Jones |

| /eɪ/ | /ei/ or /e/ | Jones or AmE |

| /aɪ/ | /ai/ or /ay/ | Jones or AmE |

| /əʊ/ | /ou/ or /o/ | Jones or AmE |

| /aʊ/ | /au/ or /aw/ | Jones or AmE |

There are a few other alternatives which are rarely used.

| . BrE pronunciation |

Nearly all of the above has so far been based on RP (Received Pronunciation) in British English although we have referred to other varieties when it was essential to do so. You may find yourself transcribing the standard American pronunciation, called GAm or just GA (General American) which has a similar status to RP in Britain. We need also to be aware that within varieties there are significant differences of accent. In the USA at least nine varieties are usually identified and, of course, the more precise and careful the analysis is, the more varieties will be described. Traditionally, in Britain eight varieties are usually recognised and each is further divided into between three and ten sub-varieties. You need to be alert to the usual differences between the varieties and transcribe what you heard, not what you expected to hear. Here's some help:

| Example | AmE | BrE |

| /ˈfɑːð.ᵊr/, /ˈfɑːð.ɚ/ or /ˈfɑːð.r̩/ | /ˈfɑːð.ə/ | |

| /nɝːs/ | /nɜːs/ | |

| /kɝːs/ | /kɜːs/ |

- Words stressed in the first syllable in BrE and the second in AmE include: ballet, barrage, baton, brochure, buffet, café, chauffeur, debris, detail, frontier, garage, massage, parquet, plateau, risqué, sachet, salon and vaccine .

- A few words show the opposite pattern, stressed on the second syllable in BrE and on the first in AmE and they include: address, cigarette, renaissance and magazine

- In BrE, it is common to stress two-syllable verbs which end in - ate on the second syllable but the first is often stressed in AmE. These include: collate, cremate, curate, dictate, donate, frustrate, gyrate, locate, migrate, mutate, narrate, placate, pulsate, rotate, spectate, stagnate, translate, vacat e and vibrate .

| Example | AmE | BrE |

| /ˈmɪ.lə.ˌte.ri/ | /ˈmɪ.lɪ.tri/ | |

| /ˈmɑː.nə.ˌste.ri/ | /ˈmɒ.nə.stri/ | |

| /ˈtest.əˌmo.ʊ.ni/ | /ˈtest.ɪ.mə.ni/ |

- Conversely, words ending in - ile usually retain the full form of the vowel in BrE but a reduced or absent form in AmE. For example, fertile is /ˈfɝː.təl/ in AmE but /ˈfɜː.taɪl/ in BrE. Another difference here is that the 'r' is given a pronunciation lacking in BrE (that can be alternatively transcribed as /ˈfɜːr.təl/ in AmE). AmE tends to have a syllabic final consonant in some words in this class so, for example, fragile may be pronounced as /ˈfræ.dʒəl/ or /ˈfræ.dʒl̩/ in AmE but is more likely to be /ˈfræ.dʒaɪl/ in BrE.

- An outlier is the pronunciation of saint before a name. In AmE, this is usually the full form as /ˈseɪnt/ but in BrE, it is reduced to /sənt/.

| Example | AmE | BrE |

| /bə.ˈnæ.nə/ | /bə.ˈnɑː.nə/ | |

| /pæθ/ | /pɑːθ/ | |

| /læst/ | /lɑːst/ | |

| /kæst/ | /kɑːst/ |

| Example | AmE | BrE |

| /ʃoʊn/ | /ʃɒn/ | |

| /ˈjoʊɡ.r̩t/ | /ˈjɒɡ.ət/ |

| Example | AmE | BrE |

| /hɑːt/ | /hɒt/ | |

| /ˈjɑːt/ | /jɒt/ |

| Example | AmE | BrE |

| /brɑːt/ | /brɔːt/ | |

| /lɑːrd/ | /lɔːd/ |

| Example | AmE | BrE |

| /ˈdaɪ.nə.sti/ | /ˈdɪ.nə.sti/ | |

| /aɪ.ˈtæ.lɪk/ | /ɪ.ˈtæ.lɪk/ | |

| /ˈpraɪ.və.si | /ˈprɪ.və.si/ |

| Example | AmE | BrE |

| /ʃət/ | /ʃʌt/ | |

| /dəl/ | /dʌl/ |

| Example | AmE | BrE |

| /ˈniː.ðər/ | /ˈnaɪ.ðə/ | |

| /ˈiː.ðər/ | /ˈaɪ.ðə/ |

| Example | AmE | BrE |

| /bɪr/ | /bɪə/ | |

| /ʃɪr/ | /ʃɪə/ |

| Example | AmE | BrE |

| /per/ | /peə/ | |

| /ʃer/ | /ʃeə/ |

| Example | AmE | BrE |

| /ˈæk.sent | /ˈæk.sənt/ | |

| /ˈnɑːn.sens/ | /ˈnɒnsəns/ (or even /ˈnɒnsns/) |

| Example | AmE | BrE |

| /ˈɒ.si/ | /ˈɒ.zi/ | |

| /ɪ.ˈreɪs/ | /ɪ.ˈreɪz/ | |

| /ˈve.nəs.n̩/ | /ˈve.nɪz.n̩/ |

| Example | AmE | BrE |

| /ɪk.ˈskɝː.ʒən/ | /ɪk.ˈskɜːʃ.n̩/ | |

| /ˌɪ.ˈmɝː.ʒən/ | /ɪ.ˈmɜːʃ.n̩/ |

| Example | AmE | BrE |

| /ˈbʌd.r̩/ | /ˈbʌt.ə/ | |

| /ˈhɑː.dər/ | /hɒ.tə/ |

| Example | AmE | BrE |

| /nuː/ | /njuː/ | |

| /duː/ | /djuː/ |

There are, of course, plenty of other differences with individual words pronounced differently in the two varieties but they do not usually represent consistent patterns. You just have to listen. There is a short, simplified document on British and American pronunciation which was written in response to a visitor's question. You can get it here . If you would like the fuller list above as a PDF document, you can get that here .

You can easily get as much practice as you like by opening a book at random, selecting some words and transcribing them. You can then go online or to a dictionary and check your answers.

If you would like to get some practice transcribing spoken language, follow the links below to Audio transcription practice.

/'lɑːst.li 'traɪ træn.'skraɪb.ɪŋ ðɪs 'sen.təns ən ðen tʃek jər 'ɑːn.sə hɪə/ Note the effects of the features of connected speech in how your and and are transcribed. The final 'r' on your is sounded because it is followed by a vowel sound and the 'd' on and is omitted because it is followed by a voiced consonant.

The pronunciation section of the in-service index on this site has separate guides to consonants, vowels, connected speech and intonation as well as a guide to syllables and phonotactics which discusses syllabic consonants and much else.

| This is the test you did at the end of the section on consonants (new tab) | |

| This is the test you did at the end of the section on vowels (new tab) | |

| for some practice in transcribing what you hear in short sentences | |

| for some more (and more difficult) practice in transcribing what you hear | |

| for more guides to aspects of pronunciation | |

| for a list of weak forms in PDF format | |

| for a list in PDF format of minimal pairs to use for recognition and production practice | |

| for a set of three recognition-only tests |

References: Crystal, D, 2008, A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics (6th edition), Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Gimson, AC, 1962 An Introduction to the Pronunciation of English, London: Arnold Roach, P, 2009, English Phonetics and Phonology: A practical course , 4th edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Wells, J, 2009, phonetic-blog.blogspot.com/2009/12/triphthongs-anyone.html

Contact | FAQs | Copyright notice | ELT Concourse charter | Disclaimer and Privacy statement | Search ELT Concourse

Phonetic - vowel sounds

Phonetic: vowels 2

Phonetic: consonants

Phonetic: transcription

Worksheets - resources

Phonetic transcription

Exercises: phonetic symbols.

- Animals 1 - transcription

- Animals 2 - transcription

- Food - transcription

- Body - transcription

- Clothes - transcription

- Numbers and colours

- House and family

- School - vocabulary

- City - vocabulary

- Nature - vocabulary

- Calendar - vocabulary

- Adjectives - vocabulary

- Transcriptions - activities

- Short sentences - 1

- Short sentences - 2

- Short sentences - 3

The Complete Guide To Phonetic Transcription (2023)

- July 17, 2023

SpeakWrite Blog

Need phonetic transcription services want to know about phonological transcription methods this ultimate guide has everything you need to know..

fəʊˈnɛtɪk trænsˈkrɪpʃᵊn ɪz kuːl.

Are you familiar with the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA)?

If not, you might wonder if your computer (or brain) just glitched after reading that first line.

Don’t worry—it didn’t. That’s just the phonetic transcription of the words “phonetic transcription is cool!”

Because we think phonological transcription is pretty cool.

And by the end of this article, you’ll know everything you need to know about it.

So whether you’re searching for professional phonetic transcription services or seeking information about phonological transcription methods, this comprehensive guide is for you.

Here’s what you need to know.

What Is Phonetic Transcription?

Phonological transcription is essentially a bridge between spoken and written communication.

It can be described as the visual representation of spoken language in written form, and it’s achieved by using phonetic symbols to depict pronunciation accurately.

Use Cases For Phonetic Transcription

You’ve seen phonetic descriptions in dictionaries or textbooks. But there are a few other ways professionals put phonetic transcription to use, too.

Enhancing language learning

Accurate phonetic transcription serves as a powerful tool for language learners. Learners can develop a better understanding of the sounds and phonetic patterns of a target language by providing a visual representation of correct pronunciation.

This enables them to improve their speaking and listening skills, enhance their overall pronunciation accuracy, and develop a more authentic accent.

Enabling linguistic research

Phonetic transcription plays a crucial role in linguistic research. It allows linguists to analyze and compare speech sounds across languages, study phonetic and phonological patterns, and investigate the historical development of languages.

Researchers can uncover insights into dialectal variations, language evolution, and the intricacies of language structure by accurately transcribing spoken language.

Improving speech therapy and pronunciation

Phonetic transcription is an invaluable resource in the field of speech therapy.

It helps speech-language pathologists accurately assess and diagnose speech disorders and articulation difficulties.

Transcribing speech sounds also allows for targeted intervention and the development of personalized therapy plans.

Assisting multilingual communication

Phonetic transcription bridges language barriers.

It facilitates accurate pronunciation and comprehension among speakers of different languages by providing a standardized and universally recognized system for representing speech sounds.

It serves as a valuable resource for language teachers, translators, and interpreters, ensuring clear and accurate communication across diverse linguistic contexts.

Types of Phonetic Transcriptions

Language is incredibly complex. So it makes sense that there are several types of phonetic transcriptions. Each one has its own specific purpose and level of detail—here’s an overview of each kind.

| Captures exact pronunciation of individual sounds within a word or utterance. | “Ship” transcribed is represented as /ʃɪp/, indicating the specific sounds of /ʃ/. |

| Emphasizes overall phonemic distinctions rather than precise phonetic variations. | “Little” may be broadly transcribed as /ˈlɪtl̩/. |

| Provides info about aspects such as stress, nasalization, length, or articulatory variations. | The vowel /æ/ (as in “cat”) with a diacritic indicating nasalization would be transcribed as [æ̃]. |

| Provides a representation of the melodic and rhythmic aspects of speech.

| Rising intonation pattern in a sentence or indicating a stressed syllable with a diacritic mark. |

| Takes into account processes like assimilation, elision, and coarticulation. | “I’m going to” in connected speech is “I’m gonna” to reflect the common assimilation of /ŋ/ in “going to” to /n/ before the /t/ sound. |

| Focuses on capturing the accurate pronunciation of words as standalone units. | Transcribing the word “tomorrow” as /təˈmɒrəʊ/.

|

| Matches the written form of words rather than capturing their exact pronunciation. | Transcribing the word “knight” as “knight.”

|

Narrow Transcription

First up is narrow transcriptions.

This aims to capture the finest phonetic details of speech. It includes specific symbols and diacritics to represent precise articulatory features such as vowel quality, consonant voicing, and manner of articulation.

For example, narrow transcriptions might be used to denote the difference between “leave” and “live,” which are close in spelling but mean completely different things.

Broad Transcription

Broad transcriptions focus on representing the main phonetic features of speech, omitting certain fine-grained details . It’s commonly used in foreign language learning materials and dictionaries.

Diacritic Transcription

Diacritic transcription involves the use of accent marks or symbols to indicate modifications or nuances in pronunciation.

These diacritics can represent native speaker features such as stress or intonation, allowing for a more precise representation of spoken language.

For instance, the German word for tschüss uses an accent called an umlaut to denote a highly rounded vowel.

Suprasegmental Transcription

Suprasegmental transcription focuses on capturing features that extend beyond individual sounds , including:

It’s particularly useful in studying language variation, poetry, and intonation patterns.

Connected Speech Transcription

Connected speech transcription involves transcribing natural speech patterns, including phenomena like assimilation, elision, and coarticulation.

It’s valuable for understanding native-like pronunciation and conversational dynamics.

Discrete Word Transcription

Discrete word transcription involves transcribing words individually without considering their surrounding context.

It’s commonly used in language learning materials, pronunciation dictionaries, and language technology applications.

Orthographic Transcription

Orthographic transcription represents speech using the standard spelling conventions of a given language.

While not as precise as phonetic transcription, orthographic transcription is helpful in providing a rough guide to pronunciation for those who are less familiar with phonetic symbols.

A Closer Look at the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA)