Action Research: Steps, Benefits, and Tips

Introduction

History of action research, what is the definition of action research, types of action research, conducting action research.

Action research is an approach to qualitative inquiry in social science research that involves the search for practical solutions to everyday issues. Rooted in real-world problems, it seeks not just to understand but also to act, bringing about positive change in specific contexts. Often distinguished by its collaborative nature, the action research process goes beyond traditional research paradigms by emphasizing the involvement of those being studied in resolving social conflicts and effecting positive change.

The value of action research lies not just in its outcomes, but also in the process itself, where stakeholders become active participants rather than mere subjects. In this article, we'll examine action research in depth, shedding light on its history, principles, and types of action research.

Tracing its roots back to the mid-20th century, Kurt Lewin developed classical action research as a response to traditional research methods in the social sciences that often sidelined the very communities they studied. Proponents of action research championed the idea that research should not just be an observational exercise but an actionable one that involves devising practical solutions. Advocates believed in the idea of research leading to immediate social action, emphasizing the importance of involving the community in the process.

Applications for action research

Over the years, action research has evolved and diversified. From its early applications in social psychology and organizational development, it has branched out into various fields such as education, healthcare, and community development, informing questions around improving schools, minority problems, and more. This growth wasn't just in application, but also in its methodologies.

How is action research different?

Like all research methodologies, effective action research generates knowledge. However, action research stands apart in its commitment to instigate tangible change. Traditional research often places emphasis on passive observation , employing data collection methods primarily to contribute to broader theoretical frameworks . In contrast, action research is inherently proactive, intertwining the acts of observing and acting.

The primary goal isn't just to understand a problem but to solve or alleviate it. Action researchers partner closely with communities, ensuring that the research process directly benefits those involved. This collaboration often leads to immediate interventions, tweaks, or solutions applied in real-time, marking a departure from other forms of research that might wait until the end of a study to make recommendations.

This proactive, change-driven nature makes action research particularly impactful in settings where immediate change is not just beneficial but essential.

Action research is best understood as a systematic approach to cooperative inquiry. Unlike traditional research methodologies that might primarily focus on generating knowledge, action research emphasizes producing actionable solutions for pressing real-world challenges.

This form of research undertakes a cyclic and reflective journey, typically cycling through stages of planning , acting, observing, and reflecting. A defining characteristic of action research is the collaborative spirit it embodies, often dissolving the rigid distinction between the researcher and the researched, leading to mutual learning and shared outcomes.

Advantages of action research

One of the foremost benefits of action research is the immediacy of its application. Since the research is embedded within real-world issues, any findings or solutions derived can often be integrated straightaway, catalyzing prompt improvements within the concerned community or organization. This immediacy is coupled with the empowering nature of the methodology. Participants aren't mere subjects; they actively shape the research process, giving them a tangible sense of ownership over both the research journey and its eventual outcomes.

Moreover, the inherent adaptability of action research allows researchers to tweak their approaches responsively based on live feedback. This ensures the research remains rooted in the evolving context, capturing the nuances of the situation and making any necessary adjustments. Lastly, this form of research tends to offer a comprehensive understanding of the issue at hand, harmonizing socially constructed theoretical knowledge with hands-on insights, leading to a richer, more textured understanding.

Disadvantages of action research

Like any methodology, action research isn't devoid of challenges. Its iterative nature, while beneficial, can extend timelines. Researchers might find themselves engaged in multiple cycles of observation, reflection, and action before arriving at a satisfactory conclusion. The intimate involvement of the researcher with the research participants , although crucial for collaboration, opens doors to potential conflicts. Through collaborative problem solving, disagreements can lead to richer and more nuanced solutions, but it can take considerable time and effort.

Another limitation stems from its focus on a specific context: results derived from a particular action research project might not always resonate or be applicable in a different context or with a different group. Lastly, the depth of collaboration this methodology demands means all stakeholders need to be deeply invested, and such a level of commitment might not always be feasible.

Examples of action research

To illustrate, let's consider a few scenarios. Imagine a classroom where a teacher observes dwindling student participation. Instead of sticking to conventional methods, the teacher experiments with introducing group-based activities. As the outcomes unfold, the teacher continually refines the approach based on student feedback, eventually leading to a teaching strategy that rejuvenates student engagement.

In a healthcare context, hospital staff who recognize growing patient anxiety related to certain procedures might innovate by introducing a new patient-informing protocol. As they study the effects of this change, they could, through iterations, sculpt a procedure that diminishes patient anxiety.

Similarly, in the realm of community development, a community grappling with the absence of child-friendly public spaces might collaborate with local authorities to conceptualize a park. As they monitor its utilization and societal impact, continual feedback could refine the park's infrastructure and design.

Contemporary action research, while grounded in the core principles of collaboration, reflection, and change, has seen various adaptations tailored to the specific needs of different contexts and fields. These adaptations have led to the emergence of distinct types of action research, each with its unique emphasis and approach.

Collaborative action research

Collaborative action research emphasizes the joint efforts of professionals, often from the same field, working together to address common concerns or challenges. In this approach, there's a strong emphasis on shared responsibility, mutual respect, and co-learning. For example, a group of classroom teachers might collaboratively investigate methods to improve student literacy, pooling their expertise and resources to devise, implement, and refine strategies for improving teaching.

Participatory action research

Participatory action research (PAR) goes a step further in dissolving the barriers between the researcher and the researched. It actively involves community members or stakeholders not just as participants, but as equal partners in the entire research process. PAR is deeply democratic and seeks to empower participants, fostering a sense of agency and ownership. For instance, a participatory research project might involve local residents in studying and addressing community health concerns, ensuring that the research process and outcomes are both informed by and beneficial to the community itself.

Educational action research

Educational action research is tailored specifically to practical educational contexts. Here, educators take on the dual role of teacher and researcher, seeking to improve teaching practices, curricula, classroom dynamics, or educational evaluation. This type of research is cyclical, with educators implementing changes, observing outcomes, and reflecting on results to continually enhance the educational experience. An example might be a teacher studying the impact of technology integration in her classroom, adjusting strategies based on student feedback and learning outcomes.

Community-based action research

Another noteworthy type is community-based action research, which focuses primarily on community development and well-being. Rooted in the principles of social justice, this approach emphasizes the collective power of community members to identify, study, and address their challenges. It's particularly powerful in grassroots movements and local development projects where community insights and collaboration drive meaningful, sustainable change.

Key insights and critical reflection through research with ATLAS.ti

Organize all your data analysis and insights with our powerful interface. Download a free trial today.

Engaging in action research is both an enlightening and transformative journey, rooted in practicality yet deeply connected to theory. For those embarking on this path, understanding the essentials of an action research study and the significance of a research cycle is paramount.

Understanding the action research cycle

At the heart of action research is its cycle, a structured yet adaptable framework guiding the research. This cycle embodies the iterative nature of action research, emphasizing that learning and change evolve through repetition and reflection.

The typical stages include:

- Identifying a problem : This is the starting point where the action researcher pinpoints a pressing issue or challenge that demands attention.

- Planning : Here, the researcher devises an action research strategy aimed at addressing the identified problem. In action research, network resources, participant consultation, and the literature review are core components in planning.

- Action : The planned strategies are then implemented in this stage. This 'action' phase is where theoretical knowledge meets practical application.

- Observation : Post-implementation, the researcher observes the outcomes and effects of the action. This stage ensures that the research remains grounded in the real-world context.

- Critical reflection : This part of the cycle involves analyzing the observed results to draw conclusions about their effectiveness and identify areas for improvement.

- Revision : Based on the insights from reflection, the initial plan is revised, marking the beginning of another cycle.

Rigorous research and iteration

It's essential to understand that while action research is deeply practical, it doesn't sacrifice rigor . The cyclical process ensures that the research remains thorough and robust. Each iteration of the cycle in an action research project refines the approach, drawing it closer to an effective solution.

The role of the action researcher

The action researcher stands at the nexus of theory and practice. Not just an observer, the researcher actively engages with the study's participants, collaboratively navigating through the research cycle by conducting interviews, participant observations, and member checking . This close involvement ensures that the study remains relevant, timely, and responsive.

Drawing conclusions and informing theory

As the research progresses through multiple iterations of data collection and data analysis , drawing conclusions becomes an integral aspect. These conclusions, while immediately beneficial in addressing the practical issue at hand, also serve a broader purpose. They inform theory, enriching the academic discourse and providing valuable insights for future research.

Identifying actionable insights

Keep in mind that action research should facilitate implications for professional practice as well as space for systematic inquiry. As you draw conclusions about the knowledge generated from action research, consider how this knowledge can create new forms of solutions to the pressing concern you set out to address.

Collecting data and analyzing data starts with ATLAS.ti

Download a free trial of our intuitive software to make the most of your research.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Action Research: What it is, Stages & Examples

The best way to get things accomplished is to do it yourself. This statement is utilized in corporations, community projects, and national governments. These organizations are relying on action research to cope with their continuously changing and unstable environments as they function in a more interdependent world.

In practical educational contexts, this involves using systematic inquiry and reflective practice to address real-world challenges, improve teaching and learning, enhance student engagement, and drive positive changes within the educational system.

This post outlines the definition of action research, its stages, and some examples.

Content Index

What is action research?

Stages of action research, the steps to conducting action research, examples of action research, advantages and disadvantages of action research.

Action research is a strategy that tries to find realistic solutions to organizations’ difficulties and issues. It is similar to applied research.

Action research refers basically learning by doing. First, a problem is identified, then some actions are taken to address it, then how well the efforts worked are measured, and if the results are not satisfactory, the steps are applied again.

It can be put into three different groups:

- Positivist: This type of research is also called “classical action research.” It considers research a social experiment. This research is used to test theories in the actual world.

- Interpretive: This kind of research is called “contemporary action research.” It thinks that business reality is socially made, and when doing this research, it focuses on the details of local and organizational factors.

- Critical: This action research cycle takes a critical reflection approach to corporate systems and tries to enhance them.

All research is about learning new things. Collaborative action research contributes knowledge based on investigations in particular and frequently useful circumstances. It starts with identifying a problem. After that, the research process is followed by the below stages:

Stage 1: Plan

For an action research project to go well, the researcher needs to plan it well. After coming up with an educational research topic or question after a research study, the first step is to develop an action plan to guide the research process. The research design aims to address the study’s question. The research strategy outlines what to undertake, when, and how.

Stage 2: Act

The next step is implementing the plan and gathering data. At this point, the researcher must select how to collect and organize research data . The researcher also needs to examine all tools and equipment before collecting data to ensure they are relevant, valid, and comprehensive.

Stage 3: Observe

Data observation is vital to any investigation. The action researcher needs to review the project’s goals and expectations before data observation. This is the final step before drawing conclusions and taking action.

Different kinds of graphs, charts, and networks can be used to represent the data. It assists in making judgments or progressing to the next stage of observing.

Stage 4: Reflect

This step involves applying a prospective solution and observing the results. It’s essential to see if the possible solution found through research can really solve the problem being studied.

The researcher must explore alternative ideas when the action research project’s solutions fail to solve the problem.

Action research is a systematic approach researchers, educators, and practitioners use to identify and address problems or challenges within a specific context. It involves a cyclical process of planning, implementing, reflecting, and adjusting actions based on the data collected. Here are the general steps involved in conducting an action research process:

Identify the action research question or problem

Clearly define the issue or problem you want to address through your research. It should be specific, actionable, and relevant to your working context.

Review existing knowledge

Conduct a literature review to understand what research has already been done on the topic. This will help you gain insights, identify gaps, and inform your research design.

Plan the research

Develop a research plan outlining your study’s objectives, methods, data collection tools, and timeline. Determine the scope of your research and the participants or stakeholders involved.

Collect data

Implement your research plan by collecting relevant data. This can involve various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, document analysis, or focus groups. Ensure that your data collection methods align with your research objectives and allow you to gather the necessary information.

Analyze the data

Once you have collected the data, analyze it using appropriate qualitative or quantitative techniques. Look for patterns, themes, or trends in the data that can help you understand the problem better.

Reflect on the findings

Reflect on the analyzed data and interpret the results in the context of your research question. Consider the implications and possible solutions that emerge from the data analysis. This reflection phase is crucial for generating insights and understanding the underlying factors contributing to the problem.

Develop an action plan

Based on your analysis and reflection, develop an action plan that outlines the steps you will take to address the identified problem. The plan should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART goals). Consider involving relevant stakeholders in planning to ensure their buy-in and support.

Implement the action plan

Put your action plan into practice by implementing the identified strategies or interventions. This may involve making changes to existing practices, introducing new approaches, or testing alternative solutions. Document the implementation process and any modifications made along the way.

Evaluate and monitor progress

Continuously monitor and evaluate the impact of your actions. Collect additional data, assess the effectiveness of the interventions, and measure progress towards your goals. This evaluation will help you determine if your actions have the desired effects and inform any necessary adjustments.

Reflect and iterate

Reflect on the outcomes of your actions and the evaluation results. Consider what worked well, what did not, and why. Use this information to refine your approach, make necessary adjustments, and plan for the next cycle of action research if needed.

Remember that participatory action research is an iterative process, and multiple cycles may be required to achieve significant improvements or solutions to the identified problem. Each cycle builds on the insights gained from the previous one, fostering continuous learning and improvement.

Explore Insightfully Contextual Inquiry in Qualitative Research

Here are two real-life examples of action research.

Action research initiatives are frequently situation-specific. Still, other researchers can adapt the techniques. The example is from a researcher’s (Franklin, 1994) report about a project encouraging nature tourism in the Caribbean.

In 1991, this was launched to study how nature tourism may be implemented on the four Windward Islands in the Caribbean: St. Lucia, Grenada, Dominica, and St. Vincent.

For environmental protection, a government-led action study determined that the consultation process needs to involve numerous stakeholders, including commercial enterprises.

First, two researchers undertook the study and held search conferences on each island. The search conferences resulted in suggestions and action plans for local community nature tourism sub-projects.

Several islands formed advisory groups and launched national awareness and community projects. Regional project meetings were held to discuss experiences, self-evaluations, and strategies. Creating a documentary about a local initiative helped build community. And the study was a success, leading to a number of changes in the area.

Lau and Hayward (1997) employed action research to analyze Internet-based collaborative work groups.

Over two years, the researchers facilitated three action research problem -solving cycles with 15 teachers, project personnel, and 25 health practitioners from diverse areas. The goal was to see how Internet-based communications might affect their virtual workgroup.

First, expectations were defined, technology was provided, and a bespoke workgroup system was developed. Participants suggested shorter, more dispersed training sessions with project-specific instructions.

The second phase saw the system’s complete deployment. The final cycle witnessed system stability and virtual group formation. The key lesson was that the learning curve was poorly misjudged, with frustrations only marginally met by phone-based technical help. According to the researchers, the absence of high-quality online material about community healthcare was harmful.

Role clarity, connection building, knowledge sharing, resource assistance, and experiential learning are vital for virtual group growth. More study is required on how group support systems might assist groups in engaging with their external environment and boost group members’ learning.

Action research has both good and bad points.

- It is very flexible, so researchers can change their analyses to fit their needs and make individual changes.

- It offers a quick and easy way to solve problems that have been going on for a long time instead of complicated, long-term solutions based on complex facts.

- If It is done right, it can be very powerful because it can lead to social change and give people the tools to make that change in ways that are important to their communities.

Disadvantages

- These studies have a hard time being generalized and are hard to repeat because they are so flexible. Because the researcher has the power to draw conclusions, they are often not thought to be theoretically sound.

- Setting up an action study in an ethical way can be hard. People may feel like they have to take part or take part in a certain way.

- It is prone to research errors like selection bias , social desirability bias, and other cognitive biases.

LEARN ABOUT: Self-Selection Bias

This post discusses how action research generates knowledge, its steps, and real-life examples. It is very applicable to the field of research and has a high level of relevance. We can only state that the purpose of this research is to comprehend an issue and find a solution to it.

At QuestionPro, we give researchers tools for collecting data, like our survey software, and a library of insights for any long-term study. Go to the Insight Hub if you want to see a demo or learn more about it.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

Frequently Asked Questions(FAQ’s)

Action research is a systematic approach to inquiry that involves identifying a problem or challenge in a practical context, implementing interventions or changes, collecting and analyzing data, and using the findings to inform decision-making and drive positive change.

Action research can be conducted by various individuals or groups, including teachers, administrators, researchers, and educational practitioners. It is often carried out by those directly involved in the educational setting where the research takes place.

The steps of action research typically include identifying a problem, reviewing relevant literature, designing interventions or changes, collecting and analyzing data, reflecting on findings, and implementing improvements based on the results.

MORE LIKE THIS

QuestionPro: Leading the Charge in Customer Journey Management and Voice of the Customer Platforms

Sep 17, 2024

Was The Experience Memorable? (Part II) — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Data Discovery: What it is, Importance, Process + Use Cases

Sep 16, 2024

Competitive Insights : Importance, How to Get + Usage

Sep 13, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Section 2: Home

- Developing the Quantitative Research Design

- Qualitative Descriptive Design

- Design and Development Research (DDR) For Instructional Design

- Qualitative Narrative Inquiry Research

- Action Research Resource

What is Action Research?

Considerations, creating a plan of action.

- Case Study Design in an Applied Doctorate

- SAGE Research Methods

- Research Examples (SAGE) This link opens in a new window

- Dataset Examples (SAGE) This link opens in a new window

- IRB Resource Center This link opens in a new window

Action research is a qualitative method that focuses on solving problems in social systems, such as schools and other organizations. The emphasis is on solving the presenting problem by generating knowledge and taking action within the social system in which the problem is located. The goal is to generate shared knowledge of how to address the problem by bridging the theory-practice gap (Bourner & Brook, 2019). A general definition of action research is the following: “Action research brings together action and reflection, as well as theory and practice, in participation with others, in the pursuit of practical solutions to issues of pressing concern” (Bradbury, 2015, p. 1). Johnson (2019) defines action research in the field of education as “the process of studying a school, classroom, or teacher-learning situation with the purpose of understanding and improving the quality of actions or instruction” (p.255).

Origins of Action Research

Kurt Lewin is typically credited with being the primary developer of Action Research in the 1940s. Lewin stated that action research can “transform…unrelated individuals, frequently opposed in their outlook and their interests, into cooperative teams, not on the basis of sweetness but on the basis of readiness to face difficulties realistically, to apply honest fact-finding, and to work together to overcome them” (1946, p.211).

Sample Action Research Topics

Some sample action research topics might be the following:

- Examining how classroom teachers perceive and implement new strategies in the classroom--How is the strategy being used? How do students respond to the strategy? How does the strategy inform and change classroom practices? Does the new skill improve test scores? Do classroom teachers perceive the strategy as effective for student learning?

- Examining how students are learning a particular content or objectives--What seems to be effective in enhancing student learning? What skills need to be reinforced? How do students respond to the new content? What is the ability of students to understand the new content?

- Examining how education stakeholders (administrator, parents, teachers, students, etc.) make decisions as members of the school’s improvement team--How are different stakeholders encouraged to participate? How is power distributed? How is equity demonstrated? How is each voice valued? How are priorities and initiatives determined? How does the team evaluate its processes to determine effectiveness?

- Examining the actions that school staff take to create an inclusive and welcoming school climate--Who makes and implements the actions taken to create the school climate? Do members of the school community (teachers, staff, students) view the school climate as inclusive? Do members of the school community feel welcome in the school? How are members of the school community encouraged to become involved in school activities? What actions can school staff take to help others feel a part of the school community?

- Examining the perceptions of teachers with regard to the learning strategies that are more effective with special populations, such as special education students, English Language Learners, etc.—What strategies are perceived to be more effective? How do teachers plan instructionally for unique learners such as special education students or English Language Learners? How do teachers deal with the challenges presented by unique learners such as special education students or English Language Learners? What supports do teachers need (e.g., professional development, training, coaching) to more effectively deliver instruction to unique learners such as special education students or English Language Learners?

Remember—The goal of action research is to find out how individuals perceive and act in a situation so the researcher can develop a plan of action to improve the educational organization. While these topics listed here can be explored using other research designs, action research is the design to use if the outcome is to develop a plan of action for addressing and improving upon a situation in the educational organization.

Considerations for Determining Whether to Use Action Research in an Applied Dissertation

- When considering action research, first determine the problem and the change that needs to occur as a result of addressing the problem (i.e., research problem and research purpose). Remember, the goal of action research is to change how individuals address a particular problem or situation in a way that results in improved practices.

- If the study will be conducted at a school site or educational organization, you may need site permission. Determine whether site permission will be given to conduct the study.

- Consider the individuals who will be part of the data collection (e.g., teachers, administrators, parents, other school staff, etc.). Will there be a representative sample willing to participate in the research?

- If students will be part of the study, does parent consent and student assent need to be obtained?

- As you develop your data collection plan, also consider the timeline for data collection. Is it feasible? For example, if you will be collecting data in a school, consider winter and summer breaks, school events, testing schedules, etc.

- As you develop your data collection plan, consult with your dissertation chair, Subject Matter Expert, NU Academic Success Center, and the NU IRB for resources and guidance.

- Action research is not an experimental design, so you are not trying to accept or reject a hypothesis. There are no independent or dependent variables. It is not generalizable to a larger setting. The goal is to understand what is occurring in the educational setting so that a plan of action can be developed for improved practices.

Considerations for Action Research

Below are some things to consider when developing your applied dissertation proposal using Action Research (adapted from Johnson, 2019):

- Research Topic and Research Problem -- Decide the topic to be studied and then identify the problem by defining the issue in the learning environment. Use references from current peer-reviewed literature for support.

- Purpose of the Study —What need to be different or improved as a result of the study?

- Research Questions —The questions developed should focus on “how” or “what” and explore individuals’ experiences, beliefs, and perceptions.

- Theoretical Framework -- What are the existing theories (theoretical framework) or concepts (conceptual framework) that can be used to support the research. How does existing theory link to what is happening in the educational environment with regard to the topic? What theories have been used to support similar topics in previous research?

- Literature Review -- Examine the literature, focusing on peer-reviewed studies published in journal within the last five years, with the exception of seminal works. What about the topic has already been explored and examined? What were the findings, implications, and limitations of previous research? What is missing from the literature on the topic? How will your proposed research address the gap in the literature?

- Data Collection —Who will be part of the sample for data collection? What data will be collected from the individuals in the study (e.g., semi-structured interviews, surveys, etc.)? What are the educational artifacts and documents that need to be collected (e.g., teacher less plans, student portfolios, student grades, etc.)? How will they be collected and during what timeframe? (Note--A list of sample data collection methods appears under the heading of “Sample Instrumentation.”)

- Data Analysis —Determine how the data will be analyzed. Some types of analyses that are frequently used for action research include thematic analysis and content analysis.

- Implications —What conclusions can be drawn based upon the findings? How do the findings relate to the existing literature and inform theory in the field of education?

- Recommendations for Practice--Create a Plan of Action— This is a critical step in action research. A plan of action is created based upon the data analysis, findings, and implications. In the Applied Dissertation, this Plan of Action is included with the Recommendations for Practice. The includes specific steps that individuals should take to change practices; recommendations for how those changes will occur (e.g., professional development, training, school improvement planning, committees to develop guidelines and policies, curriculum review committee, etc.); and methods to evaluate the plan’s effectiveness.

- Recommendations for Research —What should future research focus on? What type of studies need to be conducted to build upon or further explore your findings.

- Professional Presentation or Defense —This is where the findings will be presented in a professional presentation or defense as the culmination of your research.

Adapted from Johnson (2019).

Considerations for Sampling and Data Collection

Below are some tips for sampling, sample size, data collection, and instrumentation for Action Research:

Sampling and Sample Size

Action research uses non-probability sampling. This is most commonly means a purposive sampling method that includes specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. However, convenience sampling can also be used (e.g., a teacher’s classroom).

Critical Concepts in Data Collection

Triangulation- - Dosemagen and Schwalbach (2019) discussed the importance of triangulation in Action Research which enhances the trustworthiness by providing multiple sources of data to analyze and confirm evidence for findings.

Trustworthiness —Trustworthiness assures that research findings are fulfill four critical elements—credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability. Reflect on the following: Are there multiple sources of data? How have you ensured credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability? Have the assumptions, limitations, and delimitations of the study been identified and explained? Was the sample a representative sample for the study? Did any individuals leave the study before it ended? How have you controlled researcher biases and beliefs? Are you drawing conclusions that are not supported by data? Have all possible themes been considered? Have you identified other studies with similar results?

Sample Instrumentation

Below are some of the possible methods for collecting action research data:

- Pre- and Post-Surveys for students and/or staff

- Staff Perception Surveys and Questionnaires

- Semi-Structured Interviews

- Focus Groups

- Observations

- Document analysis

- Student work samples

- Classroom artifacts, such as teacher lesson plans, rubrics, checklists, etc.

- Attendance records

- Discipline data

- Journals from students and/or staff

- Portfolios from students and/or staff

A benefit of Action Research is its potential to influence educational practice. Many educators are, by nature of the profession, reflective, inquisitive, and action-oriented. The ultimate outcome of Action Research is to create a plan of action using the research findings to inform future educational practice. A Plan of Action is not meant to be a one-size fits all plan. Instead, it is mean to include specific data-driven and research-based recommendations that result from a detailed analysis of the data, the study findings, and implications of the Action Research study. An effective Plan of Action includes an evaluation component and opportunities for professional educator reflection that allows for authentic discussion aimed at continuous improvement.

When developing a Plan of Action, the following should be considered:

- How can this situation be approached differently in the future?

- What should change in terms of practice?

- What are the specific steps that individuals should take to change practices?

- What is needed to implement the changes being recommended (professional development, training, materials, resources, planning committees, school improvement planning, etc.)?

- How will the effectiveness of the implemented changes be evaluated?

- How will opportunities for professional educator reflection be built into the Action Plan?

Sample Action Research Studies

Anderson, A. J. (2020). A qualitative systematic review of youth participatory action research implementation in U.S. high schools. A merican Journal of Community Psychology, 65 (1/2), 242–257. https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.proxy1.ncu.edu/doi/epdf/10.1002/ajcp.12389

Ayvaz, Ü., & Durmuş, S.(2021). Fostering mathematical creativity with problem posing activities: An action research with gifted students. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 40. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselp&AN=S1871187121000614&site=eds-live

Bellino, M. J. (2018). Closing information gaps in Kakuma Refugee Camp: A youth participatory action research study. American Journal of Community Psychology, 62 (3/4), 492–507. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ofs&AN=133626988&site=eds-live

Beneyto, M., Castillo, J., Collet-Sabé, J., & Tort, A. (2019). Can schools become an inclusive space shared by all families? Learnings and debates from an action research project in Catalonia. Educational Action Research, 27 (2), 210–226. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=135671904&site=eds-live

Bilican, K., Senler, B., & Karısan, D. (2021). Fostering teacher educators’ professional development through collaborative action research. International Journal of Progressive Education, 17 (2), 459–472. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=149828364&site=eds-live

Black, G. L. (2021). Implementing action research in a teacher preparation program: Opportunities and limitations. Canadian Journal of Action Research, 21 (2), 47–71. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=149682611&site=eds-live

Bozkuş, K., & Bayrak, C. (2019). The Application of the dynamic teacher professional development through experimental action research. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 11 (4), 335–352. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=135580911&site=eds-live

Christ, T. W. (2018). Mixed methods action research in special education: An overview of a grant-funded model demonstration project. Research in the Schools, 25( 2), 77–88. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=135047248&site=eds-live

Jakhelln, R., & Pörn, M. (2019). Challenges in supporting and assessing bachelor’s theses based on action research in initial teacher education. Educational Action Research, 27 (5), 726–741. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=140234116&site=eds-live

Klima Ronen, I. (2020). Action research as a methodology for professional development in leading an educational process. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 64 . https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselp&AN=S0191491X19302159&site=eds-live

Messiou, K. (2019). Collaborative action research: facilitating inclusion in schools. Educational Action Research, 27 (2), 197–209. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=135671898&site=eds-live

Mitchell, D. E. (2018). Say it loud: An action research project examining the afrivisual and africology, Looking for alternative African American community college teaching strategies. Journal of Pan African Studies, 12 (4), 364–487. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ofs&AN=133155045&site=eds-live

Pentón Herrera, L. J. (2018). Action research as a tool for professional development in the K-12 ELT classroom. TESL Canada Journal, 35 (2), 128–139. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ofs&AN=135033158&site=eds-live

Rodriguez, R., Macias, R. L., Perez-Garcia, R., Landeros, G., & Martinez, A. (2018). Action research at the intersection of structural and family violence in an immigrant Latino community: a youth-led study. Journal of Family Violence, 33 (8), 587–596. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ccm&AN=132323375&site=eds-live

Vaughan, M., Boerum, C., & Whitehead, L. (2019). Action research in doctoral coursework: Perceptions of independent research experiences. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 13 . https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsdoj&AN=edsdoj.17aa0c2976c44a0991e69b2a7b4f321&site=eds-live

Sample Journals for Action Research

Educational Action Research

Canadian Journal of Action Research

Sample Resource Videos

Call-Cummings, M. (2017). Researching racism in schools using participatory action research [Video]. Sage Research Methods http://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?URL=https://methods.sagepub.com/video/researching-racism-in-schools-using-participatory-action-research

Fine, M. (2016). Michelle Fine discusses community based participatory action research [Video]. Sage Knowledge. http://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?URL=https://sk-sagepub-com.proxy1.ncu.edu/video/michelle-fine-discusses-community-based-participatory-action-research

Getz, C., Yamamura, E., & Tillapaugh. (2017). Action Research in Education. [Video]. You Tube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X2tso4klYu8

Bradbury, H. (Ed.). (2015). The handbook of action research (3rd edition). Sage.

Bradbury, H., Lewis, R. & Embury, D.C. (2019). Education action research: With and for the next generation. In C.A. Mertler (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of action research in education (1st edition). John Wiley and Sons. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nu/reader.action?docID=5683581&ppg=205

Bourner, T., & Brook, C. (2019). Comparing and contrasting action research and action learning. In C.A. Mertler (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of action research in education (1st edition). John Wiley and Sons. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nu/reader.action?docID=5683581&ppg=205

Bradbury, H. (2015). The Sage handbook of action research . Sage. https://www-doi-org.proxy1.ncu.edu/10.4135/9781473921290

Dosemagen, D.M. & Schwalback, E.M. (2019). Legitimacy of and value in action research. In C.A. Mertler (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of action research in education (1st edition). John Wiley and Sons. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nu/reader.action?docID=5683581&ppg=205

Johnson, A. (2019). Action research for teacher professional development. In C.A. Mertler (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of action research in education (1st edition). John Wiley and Sons. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nu/reader.action?docID=5683581&ppg=205

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. In G.W. Lewin (Ed.), Resolving social conflicts: Selected papers on group dynamics (compiled in 1948). Harper and Row.

Mertler, C. A. (Ed.). (2019). The Wiley handbook of action research in education. John Wiley and Sons. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nu/detail.action?docID=5683581

- << Previous: Qualitative Narrative Inquiry Research

- Next: Case Study Design in an Applied Doctorate >>

- Last Updated: Jul 28, 2023 8:05 AM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/c.php?g=1013605

© Copyright 2024 National University. All Rights Reserved.

Privacy Policy | Consumer Information

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 What is Action Research for Classroom Teachers?

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

- What is the nature of action research?

- How does action research develop in the classroom?

- What models of action research work best for your classroom?

- What are the epistemological, ontological, theoretical underpinnings of action research?

Educational research provides a vast landscape of knowledge on topics related to teaching and learning, curriculum and assessment, students’ cognitive and affective needs, cultural and socio-economic factors of schools, and many other factors considered viable to improving schools. Educational stakeholders rely on research to make informed decisions that ultimately affect the quality of schooling for their students. Accordingly, the purpose of educational research is to engage in disciplined inquiry to generate knowledge on topics significant to the students, teachers, administrators, schools, and other educational stakeholders. Just as the topics of educational research vary, so do the approaches to conducting educational research in the classroom. Your approach to research will be shaped by your context, your professional identity, and paradigm (set of beliefs and assumptions that guide your inquiry). These will all be key factors in how you generate knowledge related to your work as an educator.

Action research is an approach to educational research that is commonly used by educational practitioners and professionals to examine, and ultimately improve, their pedagogy and practice. In this way, action research represents an extension of the reflection and critical self-reflection that an educator employs on a daily basis in their classroom. When students are actively engaged in learning, the classroom can be dynamic and uncertain, demanding the constant attention of the educator. Considering these demands, educators are often only able to engage in reflection that is fleeting, and for the purpose of accommodation, modification, or formative assessment. Action research offers one path to more deliberate, substantial, and critical reflection that can be documented and analyzed to improve an educator’s practice.

Purpose of Action Research

As one of many approaches to educational research, it is important to distinguish the potential purposes of action research in the classroom. This book focuses on action research as a method to enable and support educators in pursuing effective pedagogical practices by transforming the quality of teaching decisions and actions, to subsequently enhance student engagement and learning. Being mindful of this purpose, the following aspects of action research are important to consider as you contemplate and engage with action research methodology in your classroom:

- Action research is a process for improving educational practice. Its methods involve action, evaluation, and reflection. It is a process to gather evidence to implement change in practices.

- Action research is participative and collaborative. It is undertaken by individuals with a common purpose.

- Action research is situation and context-based.

- Action research develops reflection practices based on the interpretations made by participants.

- Knowledge is created through action and application.

- Action research can be based in problem-solving, if the solution to the problem results in the improvement of practice.

- Action research is iterative; plans are created, implemented, revised, then implemented, lending itself to an ongoing process of reflection and revision.

- In action research, findings emerge as action develops and takes place; however, they are not conclusive or absolute, but ongoing (Koshy, 2010, pgs. 1-2).

In thinking about the purpose of action research, it is helpful to situate action research as a distinct paradigm of educational research. I like to think about action research as part of the larger concept of living knowledge. Living knowledge has been characterized as “a quest for life, to understand life and to create… knowledge which is valid for the people with whom I work and for myself” (Swantz, in Reason & Bradbury, 2001, pg. 1). Why should educators care about living knowledge as part of educational research? As mentioned above, action research is meant “to produce practical knowledge that is useful to people in the everyday conduct of their lives and to see that action research is about working towards practical outcomes” (Koshy, 2010, pg. 2). However, it is also about:

creating new forms of understanding, since action without reflection and understanding is blind, just as theory without action is meaningless. The participatory nature of action research makes it only possible with, for and by persons and communities, ideally involving all stakeholders both in the questioning and sense making that informs the research, and in the action, which is its focus. (Reason & Bradbury, 2001, pg. 2)

In an effort to further situate action research as living knowledge, Jean McNiff reminds us that “there is no such ‘thing’ as ‘action research’” (2013, pg. 24). In other words, action research is not static or finished, it defines itself as it proceeds. McNiff’s reminder characterizes action research as action-oriented, and a process that individuals go through to make their learning public to explain how it informs their practice. Action research does not derive its meaning from an abstract idea, or a self-contained discovery – action research’s meaning stems from the way educators negotiate the problems and successes of living and working in the classroom, school, and community.

While we can debate the idea of action research, there are people who are action researchers, and they use the idea of action research to develop principles and theories to guide their practice. Action research, then, refers to an organization of principles that guide action researchers as they act on shared beliefs, commitments, and expectations in their inquiry.

Reflection and the Process of Action Research

When an individual engages in reflection on their actions or experiences, it is typically for the purpose of better understanding those experiences, or the consequences of those actions to improve related action and experiences in the future. Reflection in this way develops knowledge around these actions and experiences to help us better regulate those actions in the future. The reflective process generates new knowledge regularly for classroom teachers and informs their classroom actions.

Unfortunately, the knowledge generated by educators through the reflective process is not always prioritized among the other sources of knowledge educators are expected to utilize in the classroom. Educators are expected to draw upon formal types of knowledge, such as textbooks, content standards, teaching standards, district curriculum and behavioral programs, etc., to gain new knowledge and make decisions in the classroom. While these forms of knowledge are important, the reflective knowledge that educators generate through their pedagogy is the amalgamation of these types of knowledge enacted in the classroom. Therefore, reflective knowledge is uniquely developed based on the action and implementation of an educator’s pedagogy in the classroom. Action research offers a way to formalize the knowledge generated by educators so that it can be utilized and disseminated throughout the teaching profession.

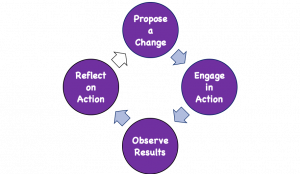

Research is concerned with the generation of knowledge, and typically creating knowledge related to a concept, idea, phenomenon, or topic. Action research generates knowledge around inquiry in practical educational contexts. Action research allows educators to learn through their actions with the purpose of developing personally or professionally. Due to its participatory nature, the process of action research is also distinct in educational research. There are many models for how the action research process takes shape. I will share a few of those here. Each model utilizes the following processes to some extent:

- Plan a change;

- Take action to enact the change;

- Observe the process and consequences of the change;

- Reflect on the process and consequences;

- Act, observe, & reflect again and so on.

Figure 1.1 Basic action research cycle

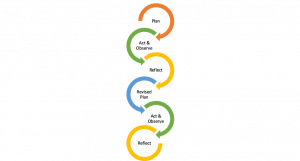

There are many other models that supplement the basic process of action research with other aspects of the research process to consider. For example, figure 1.2 illustrates a spiral model of action research proposed by Kemmis and McTaggart (2004). The spiral model emphasizes the cyclical process that moves beyond the initial plan for change. The spiral model also emphasizes revisiting the initial plan and revising based on the initial cycle of research:

Figure 1.2 Interpretation of action research spiral, Kemmis and McTaggart (2004, p. 595)

Other models of action research reorganize the process to emphasize the distinct ways knowledge takes shape in the reflection process. O’Leary’s (2004, p. 141) model, for example, recognizes that the research may take shape in the classroom as knowledge emerges from the teacher’s observations. O’Leary highlights the need for action research to be focused on situational understanding and implementation of action, initiated organically from real-time issues:

Figure 1.3 Interpretation of O’Leary’s cycles of research, O’Leary (2000, p. 141)

Lastly, Macintyre’s (2000, p. 1) model, offers a different characterization of the action research process. Macintyre emphasizes a messier process of research with the initial reflections and conclusions as the benchmarks for guiding the research process. Macintyre emphasizes the flexibility in planning, acting, and observing stages to allow the process to be naturalistic. Our interpretation of Macintyre process is below:

Figure 1.4 Interpretation of the action research cycle, Macintyre (2000, p. 1)

We believe it is important to prioritize the flexibility of the process, and encourage you to only use these models as basic guides for your process. Your process may look similar, or you may diverge from these models as you better understand your students, context, and data.

Definitions of Action Research and Examples

At this point, it may be helpful for readers to have a working definition of action research and some examples to illustrate the methodology in the classroom. Bassey (1998, p. 93) offers a very practical definition and describes “action research as an inquiry which is carried out in order to understand, to evaluate and then to change, in order to improve educational practice.” Cohen and Manion (1994, p. 192) situate action research differently, and describe action research as emergent, writing:

essentially an on-the-spot procedure designed to deal with a concrete problem located in an immediate situation. This means that ideally, the step-by-step process is constantly monitored over varying periods of time and by a variety of mechanisms (questionnaires, diaries, interviews and case studies, for example) so that the ensuing feedback may be translated into modifications, adjustment, directional changes, redefinitions, as necessary, so as to bring about lasting benefit to the ongoing process itself rather than to some future occasion.

Lastly, Koshy (2010, p. 9) describes action research as:

a constructive inquiry, during which the researcher constructs his or her knowledge of specific issues through planning, acting, evaluating, refining and learning from the experience. It is a continuous learning process in which the researcher learns and also shares the newly generated knowledge with those who may benefit from it.

These definitions highlight the distinct features of action research and emphasize the purposeful intent of action researchers to improve, refine, reform, and problem-solve issues in their educational context. To better understand the distinctness of action research, these are some examples of action research topics:

Examples of Action Research Topics

- Flexible seating in 4th grade classroom to increase effective collaborative learning.

- Structured homework protocols for increasing student achievement.

- Developing a system of formative feedback for 8th grade writing.

- Using music to stimulate creative writing.

- Weekly brown bag lunch sessions to improve responses to PD from staff.

- Using exercise balls as chairs for better classroom management.

Action Research in Theory

Action research-based inquiry in educational contexts and classrooms involves distinct participants – students, teachers, and other educational stakeholders within the system. All of these participants are engaged in activities to benefit the students, and subsequently society as a whole. Action research contributes to these activities and potentially enhances the participants’ roles in the education system. Participants’ roles are enhanced based on two underlying principles:

- communities, schools, and classrooms are sites of socially mediated actions, and action research provides a greater understanding of self and new knowledge of how to negotiate these socially mediated environments;

- communities, schools, and classrooms are part of social systems in which humans interact with many cultural tools, and action research provides a basis to construct and analyze these interactions.

In our quest for knowledge and understanding, we have consistently analyzed human experience over time and have distinguished between types of reality. Humans have constantly sought “facts” and “truth” about reality that can be empirically demonstrated or observed.

Social systems are based on beliefs, and generally, beliefs about what will benefit the greatest amount of people in that society. Beliefs, and more specifically the rationale or support for beliefs, are not always easy to demonstrate or observe as part of our reality. Take the example of an English Language Arts teacher who prioritizes argumentative writing in her class. She believes that argumentative writing demonstrates the mechanics of writing best among types of writing, while also providing students a skill they will need as citizens and professionals. While we can observe the students writing, and we can assess their ability to develop a written argument, it is difficult to observe the students’ understanding of argumentative writing and its purpose in their future. This relates to the teacher’s beliefs about argumentative writing; we cannot observe the real value of the teaching of argumentative writing. The teacher’s rationale and beliefs about teaching argumentative writing are bound to the social system and the skills their students will need to be active parts of that system. Therefore, our goal through action research is to demonstrate the best ways to teach argumentative writing to help all participants understand its value as part of a social system.

The knowledge that is conveyed in a classroom is bound to, and justified by, a social system. A postmodernist approach to understanding our world seeks knowledge within a social system, which is directly opposed to the empirical or positivist approach which demands evidence based on logic or science as rationale for beliefs. Action research does not rely on a positivist viewpoint to develop evidence and conclusions as part of the research process. Action research offers a postmodernist stance to epistemology (theory of knowledge) and supports developing questions and new inquiries during the research process. In this way action research is an emergent process that allows beliefs and decisions to be negotiated as reality and meaning are being constructed in the socially mediated space of the classroom.

Theorizing Action Research for the Classroom

All research, at its core, is for the purpose of generating new knowledge and contributing to the knowledge base of educational research. Action researchers in the classroom want to explore methods of improving their pedagogy and practice. The starting place of their inquiry stems from their pedagogy and practice, so by nature the knowledge created from their inquiry is often contextually specific to their classroom, school, or community. Therefore, we should examine the theoretical underpinnings of action research for the classroom. It is important to connect action research conceptually to experience; for example, Levin and Greenwood (2001, p. 105) make these connections:

- Action research is context bound and addresses real life problems.

- Action research is inquiry where participants and researchers cogenerate knowledge through collaborative communicative processes in which all participants’ contributions are taken seriously.

- The meanings constructed in the inquiry process lead to social action or these reflections and action lead to the construction of new meanings.

- The credibility/validity of action research knowledge is measured according to whether the actions that arise from it solve problems (workability) and increase participants’ control over their own situation.

Educators who engage in action research will generate new knowledge and beliefs based on their experiences in the classroom. Let us emphasize that these are all important to you and your work, as both an educator and researcher. It is these experiences, beliefs, and theories that are often discounted when more official forms of knowledge (e.g., textbooks, curriculum standards, districts standards) are prioritized. These beliefs and theories based on experiences should be valued and explored further, and this is one of the primary purposes of action research in the classroom. These beliefs and theories should be valued because they were meaningful aspects of knowledge constructed from teachers’ experiences. Developing meaning and knowledge in this way forms the basis of constructivist ideology, just as teachers often try to get their students to construct their own meanings and understandings when experiencing new ideas.

Classroom Teachers Constructing their Own Knowledge

Most of you are probably at least minimally familiar with constructivism, or the process of constructing knowledge. However, what is constructivism precisely, for the purposes of action research? Many scholars have theorized constructivism and have identified two key attributes (Koshy, 2010; von Glasersfeld, 1987):

- Knowledge is not passively received, but actively developed through an individual’s cognition;

- Human cognition is adaptive and finds purpose in organizing the new experiences of the world, instead of settling for absolute or objective truth.

Considering these two attributes, constructivism is distinct from conventional knowledge formation because people can develop a theory of knowledge that orders and organizes the world based on their experiences, instead of an objective or neutral reality. When individuals construct knowledge, there are interactions between an individual and their environment where communication, negotiation and meaning-making are collectively developing knowledge. For most educators, constructivism may be a natural inclination of their pedagogy. Action researchers have a similar relationship to constructivism because they are actively engaged in a process of constructing knowledge. However, their constructions may be more formal and based on the data they collect in the research process. Action researchers also are engaged in the meaning making process, making interpretations from their data. These aspects of the action research process situate them in the constructivist ideology. Just like constructivist educators, action researchers’ constructions of knowledge will be affected by their individual and professional ideas and values, as well as the ecological context in which they work (Biesta & Tedder, 2006). The relations between constructivist inquiry and action research is important, as Lincoln (2001, p. 130) states:

much of the epistemological, ontological, and axiological belief systems are the same or similar, and methodologically, constructivists and action researchers work in similar ways, relying on qualitative methods in face-to-face work, while buttressing information, data and background with quantitative method work when necessary or useful.

While there are many links between action research and educators in the classroom, constructivism offers the most familiar and practical threads to bind the beliefs of educators and action researchers.

Epistemology, Ontology, and Action Research

It is also important for educators to consider the philosophical stances related to action research to better situate it with their beliefs and reality. When researchers make decisions about the methodology they intend to use, they will consider their ontological and epistemological stances. It is vital that researchers clearly distinguish their philosophical stances and understand the implications of their stance in the research process, especially when collecting and analyzing their data. In what follows, we will discuss ontological and epistemological stances in relation to action research methodology.

Ontology, or the theory of being, is concerned with the claims or assumptions we make about ourselves within our social reality – what do we think exists, what does it look like, what entities are involved and how do these entities interact with each other (Blaikie, 2007). In relation to the discussion of constructivism, generally action researchers would consider their educational reality as socially constructed. Social construction of reality happens when individuals interact in a social system. Meaningful construction of concepts and representations of reality develop through an individual’s interpretations of others’ actions. These interpretations become agreed upon by members of a social system and become part of social fabric, reproduced as knowledge and beliefs to develop assumptions about reality. Researchers develop meaningful constructions based on their experiences and through communication. Educators as action researchers will be examining the socially constructed reality of schools. In the United States, many of our concepts, knowledge, and beliefs about schooling have been socially constructed over the last hundred years. For example, a group of teachers may look at why fewer female students enroll in upper-level science courses at their school. This question deals directly with the social construction of gender and specifically what careers females have been conditioned to pursue. We know this is a social construction in some school social systems because in other parts of the world, or even the United States, there are schools that have more females enrolled in upper level science courses than male students. Therefore, the educators conducting the research have to recognize the socially constructed reality of their school and consider this reality throughout the research process. Action researchers will use methods of data collection that support their ontological stance and clarify their theoretical stance throughout the research process.

Koshy (2010, p. 23-24) offers another example of addressing the ontological challenges in the classroom:

A teacher who was concerned with increasing her pupils’ motivation and enthusiasm for learning decided to introduce learning diaries which the children could take home. They were invited to record their reactions to the day’s lessons and what they had learnt. The teacher reported in her field diary that the learning diaries stimulated the children’s interest in her lessons, increased their capacity to learn, and generally improved their level of participation in lessons. The challenge for the teacher here is in the analysis and interpretation of the multiplicity of factors accompanying the use of diaries. The diaries were taken home so the entries may have been influenced by discussions with parents. Another possibility is that children felt the need to please their teacher. Another possible influence was that their increased motivation was as a result of the difference in style of teaching which included more discussions in the classroom based on the entries in the dairies.

Here you can see the challenge for the action researcher is working in a social context with multiple factors, values, and experiences that were outside of the teacher’s control. The teacher was only responsible for introducing the diaries as a new style of learning. The students’ engagement and interactions with this new style of learning were all based upon their socially constructed notions of learning inside and outside of the classroom. A researcher with a positivist ontological stance would not consider these factors, and instead might simply conclude that the dairies increased motivation and interest in the topic, as a result of introducing the diaries as a learning strategy.

Epistemology, or the theory of knowledge, signifies a philosophical view of what counts as knowledge – it justifies what is possible to be known and what criteria distinguishes knowledge from beliefs (Blaikie, 1993). Positivist researchers, for example, consider knowledge to be certain and discovered through scientific processes. Action researchers collect data that is more subjective and examine personal experience, insights, and beliefs.

Action researchers utilize interpretation as a means for knowledge creation. Action researchers have many epistemologies to choose from as means of situating the types of knowledge they will generate by interpreting the data from their research. For example, Koro-Ljungberg et al., (2009) identified several common epistemologies in their article that examined epistemological awareness in qualitative educational research, such as: objectivism, subjectivism, constructionism, contextualism, social epistemology, feminist epistemology, idealism, naturalized epistemology, externalism, relativism, skepticism, and pluralism. All of these epistemological stances have implications for the research process, especially data collection and analysis. Please see the table on pages 689-90, linked below for a sketch of these potential implications:

Again, Koshy (2010, p. 24) provides an excellent example to illustrate the epistemological challenges within action research:

A teacher of 11-year-old children decided to carry out an action research project which involved a change in style in teaching mathematics. Instead of giving children mathematical tasks displaying the subject as abstract principles, she made links with other subjects which she believed would encourage children to see mathematics as a discipline that could improve their understanding of the environment and historic events. At the conclusion of the project, the teacher reported that applicable mathematics generated greater enthusiasm and understanding of the subject.

The educator/researcher engaged in action research-based inquiry to improve an aspect of her pedagogy. She generated knowledge that indicated she had improved her students’ understanding of mathematics by integrating it with other subjects – specifically in the social and ecological context of her classroom, school, and community. She valued constructivism and students generating their own understanding of mathematics based on related topics in other subjects. Action researchers working in a social context do not generate certain knowledge, but knowledge that emerges and can be observed and researched again, building upon their knowledge each time.

Researcher Positionality in Action Research

In this first chapter, we have discussed a lot about the role of experiences in sparking the research process in the classroom. Your experiences as an educator will shape how you approach action research in your classroom. Your experiences as a person in general will also shape how you create knowledge from your research process. In particular, your experiences will shape how you make meaning from your findings. It is important to be clear about your experiences when developing your methodology too. This is referred to as researcher positionality. Maher and Tetreault (1993, p. 118) define positionality as:

Gender, race, class, and other aspects of our identities are markers of relational positions rather than essential qualities. Knowledge is valid when it includes an acknowledgment of the knower’s specific position in any context, because changing contextual and relational factors are crucial for defining identities and our knowledge in any given situation.

By presenting your positionality in the research process, you are signifying the type of socially constructed, and other types of, knowledge you will be using to make sense of the data. As Maher and Tetreault explain, this increases the trustworthiness of your conclusions about the data. This would not be possible with a positivist ontology. We will discuss positionality more in chapter 6, but we wanted to connect it to the overall theoretical underpinnings of action research.

Advantages of Engaging in Action Research in the Classroom

In the following chapters, we will discuss how action research takes shape in your classroom, and we wanted to briefly summarize the key advantages to action research methodology over other types of research methodology. As Koshy (2010, p. 25) notes, action research provides useful methodology for school and classroom research because:

Advantages of Action Research for the Classroom

- research can be set within a specific context or situation;

- researchers can be participants – they don’t have to be distant and detached from the situation;

- it involves continuous evaluation and modifications can be made easily as the project progresses;

- there are opportunities for theory to emerge from the research rather than always follow a previously formulated theory;

- the study can lead to open-ended outcomes;

- through action research, a researcher can bring a story to life.

Action Research Copyright © by J. Spencer Clark; Suzanne Porath; Julie Thiele; and Morgan Jobe is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Guide to Writing the Results and Discussion Sections of a Scientific Article

A quality research paper has both the qualities of in-depth research and good writing ( Bordage, 2001 ). In addition, a research paper must be clear, concise, and effective when presenting the information in an organized structure with a logical manner ( Sandercock, 2013 ).

In this article, we will take a closer look at the results and discussion section. Composing each of these carefully with sufficient data and well-constructed arguments can help improve your paper overall.

The results section of your research paper contains a description about the main findings of your research, whereas the discussion section interprets the results for readers and provides the significance of the findings. The discussion should not repeat the results.

Let’s dive in a little deeper about how to properly, and clearly organize each part.

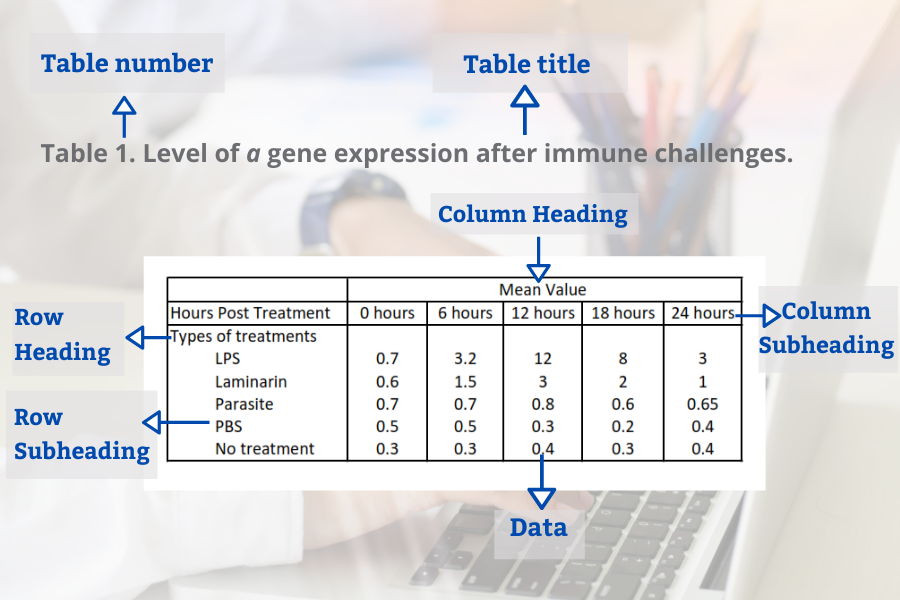

How to Organize the Results Section

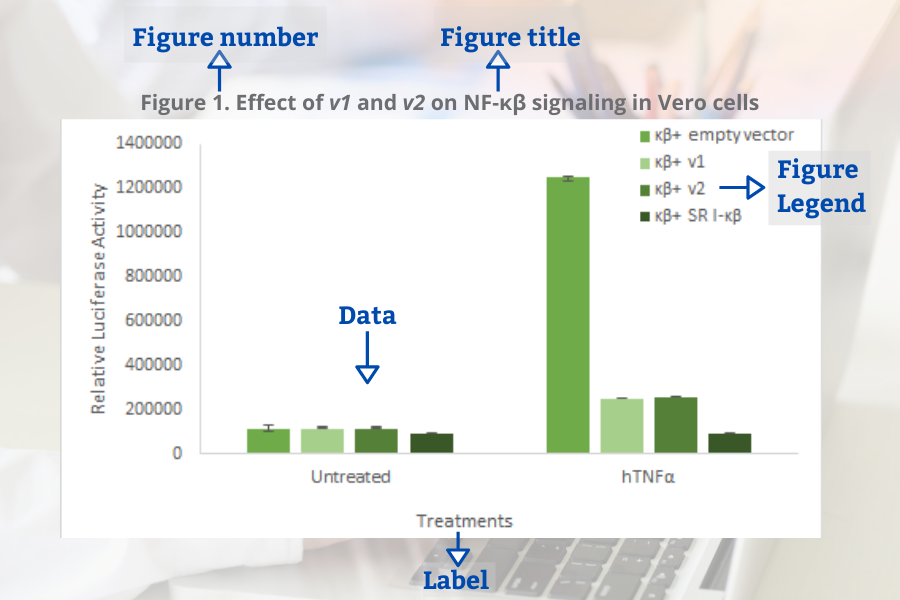

Since your results follow your methods, you’ll want to provide information about what you discovered from the methods you used, such as your research data. In other words, what were the outcomes of the methods you used?