An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Change Management: From Theory to Practice

Jeffrey phillips.

1 University Libraries, Florida State University, 116 Honors Way, Tallahassee, FL 32306 USA

James D. Klein

2 Department of Educational Psychology & Learning Systems, College of Education, Florida State University, Stone Building-3205F, Tallahassee, FL 32306-4453 USA

This article presents a set of change management strategies found across several models and frameworks and identifies how frequently change management practitioners implement these strategies in practice. We searched the literature to identify 15 common strategies found in 16 different change management models and frameworks. We also created a questionnaire based on the literature and distributed it to change management practitioners. Findings suggest that strategies related to communication, stakeholder involvement, encouragement, organizational culture, vision, and mission should be used when implementing organizational change.

Organizations must change to survive. There are many approaches to influence change; these differences require change managers to consider various strategies that increase acceptance and reduce barriers. A change manager is responsible for planning, developing, leading, evaluating, assessing, supporting, and sustaining a change implementation. Change management consists of models and strategies to help employees accept new organizational developments.

Change management practitioners and academic researchers view organizational change differently (Hughes, 2007 ; Pollack & Pollack, 2015 ). Saka ( 2003 ) states, “there is a gap between what the rational-linear change management approach prescribes and what change agents do” (p. 483). This disconnect may make it difficult to determine the suitability and appropriateness of using different techniques to promote change (Pollack & Pollack, 2015 ). Hughes ( 2007 ) thinks that practitioners and academics may have trouble communicating because they use different terms. Whereas academics use the terms, models, theories, and concepts, practitioners use tools and techniques. A tool is a stand-alone application, and a technique is an integrated approach (Dale & McQuater, 1998 ). Hughes ( 2007 ) expresses that classifying change management tools and techniques can help academics identify what practitioners do in the field and evaluate the effectiveness of practitioners’ implementations.

There is little empirical evidence that supports a preferred change management model (Hallencreutz & Turner, 2011 ). However, there are many similar strategies found across change management models (Raineri, 2011 ). Bamford and Forrester’s ( 2003 ) case study showed that “[change] managers in a company generally ignored the popular change literature” (p. 560). The authors followed Pettigrew’s ( 1987 ) suggestions that change managers should not use abstract theories; instead, they should relate change theories to the context of the change. Neves’ ( 2009 ) exploratory factor analysis of employees experiencing the implementation of a new performance appraisal system at a public university suggested that (a) change appropriateness (if the employee felt the change was beneficial to the organization) was positively related with affective commitment (how much the employee liked their job), and (b) affective commitment mediated the relationship between change appropriateness and individual change (how much the employee shifted to the new system). It is unlikely that there is a universal change management approach that works in all settings (Saka, 2003 ). Because change is chaotic, one specific model or framework may not be useful in multiple contexts (Buchanan & Boddy, 1992 ; Pettigrew & Whipp, 1991 ). This requires change managers to consider various approaches for different implementations (Pettigrew, 1987 ). Change managers may face uncertainties that cannot be addressed by a planned sequence of steps (Carnall, 2007 ; Pettigrew & Whipp, 1991 ). Different stakeholders within an organization may complete steps at different times (Pollack & Pollack, 2015 ). Although there may not be one perspective change management approach, many models and frameworks consist of similar change management strategies.

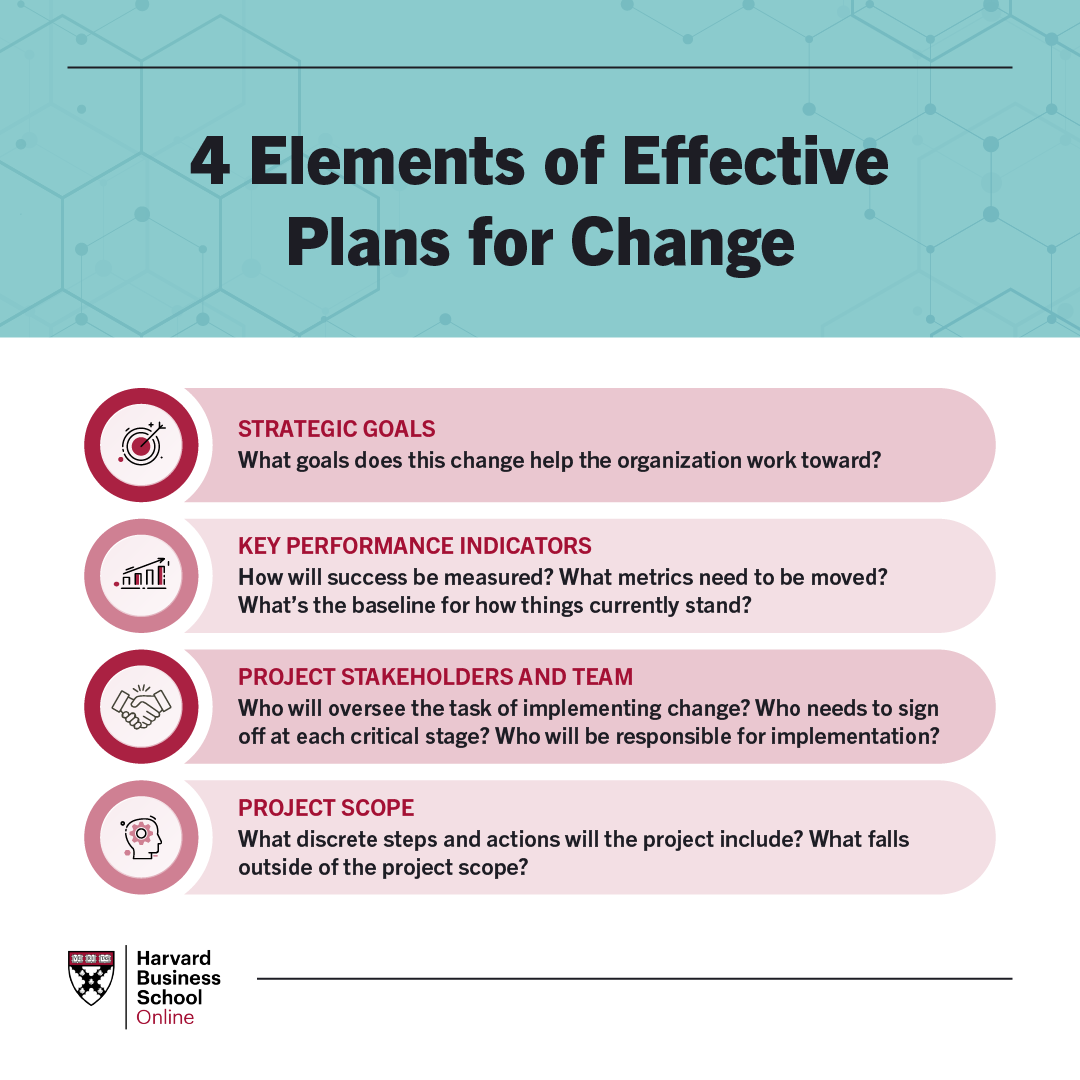

Anderson and Ackerman Anderson ( 2001 ) discuss the differences between change frameworks and change process models. They state that a change framework identifies topics that are relevant to the change and explains the procedures that organizations should acknowledge during the change. However, the framework does not provide details about how to accomplish the steps of the change or the sequence in which the change manager should perform the steps. Additionally, Anderson and Ackerman Anderson ( 2001 ) explain that change process models describe what actions are necessary to accomplish the change and the order in which to facilitate the actions. Whereas frameworks may identify variables or theories required to promote change, models focus on the specific processes that lead to change. Based on the literature, we define a change strategy as a process or action from a model or framework. Multiple models and frameworks contain similar strategies. Change managers use models and frameworks contextually; some change management strategies may be used across numerous models and frameworks.

The purpose of this article is to present a common set of change management strategies found across numerous models and frameworks and identify how frequently change management practitioners implement these common strategies in practice. We also compare current practice with models and frameworks from the literature. Some change management models and frameworks have been around for decades and others are more recent. This comparison may assist practitioners and theorists to consider different strategies that fall outside a specific model.

Common Strategies in the Change Management Literature

We examined highly-cited publications ( n > 1000 citations) from the last 20 years, business websites, and university websites to select organizational change management models and frameworks. First, we searched two indexes—Google Scholar and Web of Science’s Social Science Citation Index. We used the following keywords in both indexes: “change management” OR “organizational change” OR “organizational development” AND (models or frameworks). Additionally, we used the same search terms in a Google search to identify models mentioned on university and business websites. This helped us identify change management models that had less presence in popular research. We only included models and frameworks from our search results that were mentioned on multiple websites. We reached saturation when multiple publications stopped identifying new models and frameworks.

After we identified the models and frameworks, we analyzed the original publications by the authors to identify observable strategies included in the models and frameworks. We coded the strategies by comparing new strategies with our previously coded strategies, and we combined similar strategies or created a new strategy. Our list of strategies was not exhaustive, but we included the most common strategies found in the publications. Finally, we omitted publications that did not provide details about the change management strategies. Although many of these publications were highly cited and identified change implementation processes or phases, the authors did not identify a specific strategy.

Table Table1 1 shows the 16 models and frameworks that we analyzed and the 15 common strategies that we identified from this analysis. Ackerman-Anderson and Anderson ( 2001 ) believe that it is important for process models to consider organizational imperatives as well as human dynamics and needs. Therefore, the list of strategies considers organizational imperatives such as create a vision for the change that aligns with the organization’s mission and strategies regarding human dynamics and needs such as listen to employees’ concerns about the change. We have presented the strategies in order of how frequently the strategies appear in the models and frameworks. Table Table1 1 only includes strategies found in at least six of the models or frameworks.

Common strategies in the change management literature

| Strategy | Models & frameworks | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | AA | B | BB | BH | C | CW | FB | GE | K | KSJ | L | LK | M | N | PW | |

| Provide all members of the organization with clear communication about the change | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Have open support and commitment from the administration | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Focus on changing organizational culture | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |

| Distinguish the differences between leadership and management | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Create a vision for the change that aligns with the organization’s mission | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||

| Reward new behavior | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||

| Listen to employees’ concerns about the change | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||

| Include employees in change decisions | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||

| Prepare for unexpected shifts | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||

| Generate short-term wins | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||

| Create groups or subsystems to tackle the change | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||

| Provide employees with training | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||

| Concentrate on ending old habits before starting new ones | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||

| Train managers and supervisors to be change agents | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||

| Gain support from opinion leaders | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||

A = ADKAR (Hiatt, 2006 ); AA = Ackerman Anderson and Anderson ( 2001 ); B = Bridges ( 1991 ); BB = Buchanan and Boddy ( 1992 ); BH = Beckhard and Harris ( 1987 ); C = Carnall ( 2007 ); CW = Cummings and Worley ( 1993 ); FB = French and Bell ( 1999 ); GE = GE CAP model (Neri et al., 2008 ; Polk, 2011 ); K = Kotter ( 2012 ); KSJ = Kanter et al. ( 1992 ); L = Lewin’s Three-step model (Bakari et al., 2017 ; Lewin, 1951 ); LK = Luecke ( 2003 ); M = McKinsey’s 7-S framework (Cox et al., 2019 ; Waterman et al., 1980 ); N = Nadler and Tushman ( 1997 ); PW = Pettigrew and Whipp (1993)

Strategies Used by Change Managers

We developed an online questionnaire to determine how frequently change managers used the strategies identified in our review of the literature. The Qualtrics-hosted survey consisted of 28 questions including sliding-scale, multiple-choice, and Likert-type items. Demographic questions focused on (a) how long the participant had been involved in the practice of change management, (b) how many change projects the participant had led, (c) the types of industries in which the participant led change implementations, (d) what percentage of job responsibilities involved working as a change manager and a project manager, and (e) where the participant learned to conduct change management. Twenty-one Likert-type items asked how often the participant used the strategies identified by our review of common change management models and frameworks. Participants could select never, sometimes, most of the time, and always. The Cronbach’s Alpha of the Likert-scale questions was 0.86.

The procedures for the questionnaire followed the steps suggested by Gall et al. ( 2003 ). The first steps were to define the research objectives, select the sample, and design the questionnaire format. The fourth step was to pretest the questionnaire. We conducted cognitive laboratory interviews by sending the questionnaire and interview questions to one person who was in the field of change management, one person who was in the field of performance improvement, and one person who was in the field of survey development (Fowler, 2014 ). We met with the reviewers through Zoom to evaluate the questionnaire by asking them to read the directions and each item for clarity. Then, reviewers were directed to point out mistakes or areas of confusion. Having multiple people review the survey instruments improved the reliability of the responses (Fowler, 2014 ).

We used purposeful sampling to distribute the online questionnaire throughout the following organizations: the Association for Talent Development (ATD), Change Management Institute (CMI), and the International Society for Performance Improvement (ISPI). We also launched a call for participation to department chairs of United States universities who had Instructional Systems Design graduate programs with a focus on Performance Improvement. We used snowball sampling to gain participants by requesting that the department chairs forward the questionnaire to practitioners who had led at least one organizational change.

Table Table2 2 provides a summary of the characteristics of the 49 participants who completed the questionnaire. Most had over ten years of experience practicing change management ( n = 37) and had completed over ten change projects ( n = 32). The participants learned how to conduct change management on-the-job ( n = 47), through books ( n = 31), through academic journal articles ( n = 22), and from college or university courses ( n = 20). The participants had worked in 13 different industries.

Characteristics of participants

| Traits | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| Percentage of job responsibilities spent as a change manager | 53.5% | |

| Percentage of job responsibilities spent as a project manager | 37.6% | |

| Years of experience | ||

10 + years 7–10 years 4–6 years 1–3 years Less than one year | 37 3 3 4 2 | |

| Number of change projects | ||

10 + projects 7–10 projects 4–6 projects 1–3 projects | 32 4 6 7 | |

| Where they learned how to conduct change management | ||

On-the-job Books Academic journal articles College or university courses Professional organization websites Certification training Other Mentors | 47 31 22 20 17 16 9 3 | |

| The most common industries where they have worked | ||

Technology Education Manufacturing Healthcare Government Pharmaceuticals Finance Chemical or fuel Retail Telecommunications Food and food processing Transportation Military and law enforcement | 21 13 13 11 9 8 8 6 6 6 5 4 2 | |

( n = 49)

Table Table3 3 shows how frequently participants indicated that they used the change management strategies included on the questionnaire. Forty or more participants said they used the following strategies most often or always: (1) Asked members of senior leadership to support the change; (2) Listened to managers’ concerns about the change; (3) Aligned an intended change with an organization’s mission; (4) Listened to employees’ concerns about the change; (5) Aligned an intended change with an organization’s vision; (6) Created measurable short-term goals; (7) Asked managers for feedback to improve the change, and (8) Focused on organizational culture.

Strategies used by change managers

| Strategy | Never 0 | Sometimes 1 | Most of the time 2 | Always 3 | Total of always and most of the time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asked members of senior leadership to support the change | 0 | 1 | 7 | 41 | 48 |

| Listened to managers’ concerns about the change | 0 | 2 | 18 | 29 | 47 |

| Aligned an intended change with an organization’s mission | 2 | 1 | 21 | 25 | 46 |

| Listened to employees’ concerns about the change | 1 | 3 | 22 | 23 | 45 |

| Aligned an intended change with an organization’s vision | 2 | 3 | 17 | 27 | 44 |

| Created measurable short-term goals | 0 | 5 | 21 | 23 | 44 |

| Asked managers for feedback to improve the change | 1 | 5 | 16 | 27 | 43 |

| Focused on organizational culture | 1 | 7 | 16 | 25 | 41 |

| Asked employees for feedback to improve the change | 2 | 9 | 9 | 29 | 38 |

| Provided verbal or written encouragement to employees about the change | 1 | 11 | 14 | 23 | 37 |

| Ensured that employees were trained for new change initiatives | 1 | 10 | 18 | 20 | 38 |

| Ensured that managers were trained to promote the change | 0 | 12 | 21 | 16 | 37 |

| Measured the success of your change initiative | 0 | 13 | 22 | 14 | 36 |

| Notified all members of the organization about the change | 2 | 14 | 17 | 16 | 33 |

| Used opinion leaders to promote the change | 2 | 16 | 19 | 12 | 31 |

| Developed managers into leaders | 1 | 20 | 16 | 12 | 28 |

| Adjusted your change implementation because of reactions from senior administrators | 1 | 20 | 17 | 11 | 28 |

| Adjusted your change implementation because of reactions from employees | 1 | 25 | 12 | 11 | 23 |

| Focused on diversity and inclusion when conducting a change | 4 | 22 | 19 | 4 | 23 |

| Helped create an organization’s vision statement | 6 | 24 | 15 | 4 | 19 |

| Provided employees with incentives to implement the change | 13 | 24 | 11 | 1 | 12 |

Table Table4 4 identifies how frequently the strategies appeared in the models and frameworks and the rate at which practitioners indicated they used the strategies most often or always. The strategies found in the top 25% of both ( n > 36 for practitioner use and n > 11 in models and frameworks) focused on communication, including senior leadership and the employees in change decisions, aligning the change with the vision and mission of the organization, and focusing on organizational culture. Practitioners used several strategies more commonly than the literature suggested, especially concerning the topic of middle management. Practitioners focused on listening to middle managers’ concerns about the change, asking managers for feedback to improve the change, and ensuring that managers were trained to promote the change. Meanwhile, practitioners did not engage in the following strategies as often as the models and frameworks suggested that they should: provide all members of the organization with clear communication about the change, distinguish the differences between leadership and management, reward new behavior, and include employees in change decisions.

A comparison of the strategies used by practitioners to the strategies found in the literature

| Strategy used by participants ( = 49) | Total of Always and Most of the time | Strategy found in the models and frameworks ( = 16) | Total models and frameworks that list the strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Used by practitioners and suggested by models and frameworks | |||

| Asked members of senior leadership to support the change | 48 | Have open support and commitment from the administration | 16 |

| Aligned an intended change with an organization’s mission | 46 | Create a vision for the change that aligns with the organization’s mission | 13 |

| Listened to employees’ concerns about the change | 45 | Listen to employees’ concerns about the change | 12 |

| Aligned an intended change with an organization’s vision | 44 | Create a vision for the change that aligns with the organization’s mission | 13 |

| Focused on organizational culture | 41 | Focus on changing organizational culture | 15 |

| Asked employees for feedback to improve the change | 38 | Include employees in change decisions | 12 |

| Used more often by practitioners than suggested by models and frameworks | |||

| Listened to managers’ concerns about the change | 47 | Train managers and supervisors to be change agents | 7 |

| Created measurable short-term goals | 44 | Generate short-term wins | 10 |

| Asked managers for feedback to improve the change | 43 | Train managers and supervisors to be change agents | 7 |

| Ensured that employees were trained for new change initiatives | 38 | Provide employees with training | 8 |

| Ensured that managers were trained to promote the change | 37 | Train managers and supervisors to be change agents | 7 |

| Suggested more often by models and frameworks than used by practitioners | |||

| Notified all members of the organization about the change | 33 | Provide all members of the organization with clear communication about the change | 16 |

| Developed managers into leaders | 28 | Distinguish the differences between leadership and management | 14 |

| Adjusted your change implementation because of reactions from employees | 23 | Include employees in change decisions | 12 |

| Provided employees with incentives to implement the change | 12 | Reward new behavior | 13 |

Common Strategies Used by Practitioners and Found in the Literature

The purpose of this article was to present a common set of change management strategies found across numerous models and frameworks and to identify how frequently change management practitioners implement these common strategies in practice. The five common change management strategies were the following: communicate about the change, involve stakeholders at all levels of the organization, focus on organizational culture, consider the organization’s mission and vision, and provide encouragement and incentives to change. Below we discuss our findings with an eye toward presenting a few key recommendations for change management.

Communicate About the Change

Communication is an umbrella term that can include messaging, networking, and negotiating (Buchanan & Boddy, 1992 ). Our findings revealed that communication is essential for change management. All the models and frameworks we examined suggested that change managers should provide members of the organization with clear communication about the change. It is interesting that approximately 33% of questionnaire respondents indicated that they sometimes, rather than always or most of the time, notified all members of the organization about the change. This may be the result of change managers communicating through organizational leaders. Instead of communicating directly with everyone in the organization, some participants may have used senior leadership, middle management, or subgroups to communicate the change. Messages sent to employees from leaders can effectively promote change. Regardless of who is responsible for communication, someone in the organization should explain why the change is happening (Connor et al., 2003 ; Doyle & Brady, 2018 ; Hiatt, 2006 ; Kotter, 2012 ) and provide clear communication throughout the entire change implementation (McKinsey & Company, 2008 ; Mento et al., 2002 ).

Involve Stakeholders at All Levels of the Organization

Our results indicate that change managers should involve senior leaders, managers, as well as employees during a change initiative. The items on the questionnaire were based on a review of common change management models and frameworks and many related to some form of stakeholder involvement. Of these strategies, over half were used often by 50% or more respondents. They focused on actions like gaining support from leaders, listening to and getting feedback from managers and employees, and adjusting strategies based on stakeholder input.

Whereas the models and frameworks often identified strategies regarding senior leadership and employees, it is interesting that questionnaire respondents indicated that they often implemented strategies involving middle management in a change implementation. This aligns with Bamford and Forrester’s ( 2003 ) research describing how middle managers are important communicators of change and provide an organization with the direction for the change. However, the participants did not develop managers into leaders as often as the literature proposed. Burnes and By ( 2012 ) expressed that leadership is essential to promote change and mention how the change management field has failed to focus on leadership as much as it should.

Focus on Organizational Culture

All but one of the models and frameworks we analyzed indicated that change managers should focus on changing the culture of an organization and more than 75% of questionnaire respondents revealed that they implemented this strategy always or most of the time. Organizational culture affects the acceptance of change. Changing the organizational culture can prevent employees from returning to the previous status quo (Bullock & Batten, 1985 ; Kotter, 2012 ; Mento et al., 2002 ). Some authors have different views on how to change an organization’s culture. For example, Burnes ( 2000 ) thinks that change managers should focus on employees who were resistant to the change while Hiatt ( 2006 ) suggests that change managers should replicate what strategies they used in the past to change the culture. Change managers require open support and commitment from managers to lead a culture change (Phillips, 2021 ).

In addition, Pless and Maak ( 2004 ) describe the importance of creating a culture of inclusion where diverse viewpoints help an organization reach its organizational objectives. Yet less than half of the participants indicated that they often focused on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). Change managers should consider diverse viewpoints when implementing change, especially for organizations whose vision promotes a diverse and inclusive workforce.

Consider the Organization’s Mission and Vision

Several of the models and frameworks we examined mentioned that change managers should consider the mission and vision of the organization (Cummings & Worley, 1993 ; Hiatt, 2006 ; Kotter, 2012 ; Polk, 2011 ). Furthermore, aligning the change with the organization’s mission and vision were among the strategies most often implemented by participants. This was the second most common strategy both used by participants and found in the models and frameworks. A mission of an organization may include its beliefs, values, priorities, strengths, and desired public image (Cummings & Worley, 1993 ). Leaders are expected to adhere to a company’s values and mission (Strebel, 1996 ).

Provide Encouragement and Incentives to Change

Most of the change management models and frameworks suggested that organizations should reward new behavior, yet most respondents said they did not provide incentives to change. About 75% of participants did indicate that they frequently gave encouragement to employees about the change. The questionnaire may have confused participants by suggesting that they provide incentives before the change occurs. Additionally, respondents may have associated incentives with monetary compensation. Employee training can be considered an incentive, and many participants confirmed that they provided employees and managers with training. More information is needed to determine why the participants did not provide incentives and what the participants defined as rewards.

Future Conversations Between Practitioners and Researchers

Table Table4 4 identified five strategies that practitioners used more often than the models and frameworks suggested and four strategies that were suggested more often by the models and frameworks than used by practitioners. One strategy that showed the largest difference was provided employees with incentives to implement the change. Although 81% of the selected models and frameworks suggested that practitioners should provide employees with incentives, only 25% of the practitioners identified that they provided incentives always and most of the time. Conversations between theorists and practitioners could determine if these differences occur because each group uses different terms (Hughes, 2007 ) or if practitioners just implement change differently than theorists suggest (Saka, 2003 ).

Additionally, conversations between theorists and practitioners may help promote improvements in the field of change management. For example, practitioners were split on how often they promoted DEI, and the selected models and frameworks did not focus on DEI in change implementations. Conversations between the two groups would help theorists understand what practitioners are doing to advance the field of change management. These conversations may encourage theorists to modify their models and frameworks to include modern approaches to change.

Limitations

The models and frameworks included in this systematic review were found through academic research and websites on the topic of change management. We did not include strategies contained on websites from change management organizations. Therefore, the identified strategies could skew towards approaches favored by theorists instead of practitioners. Additionally, we used specific publications to identify the strategies found in the models and frameworks. Any amendments to the cited models or frameworks found in future publications could not be included in this research.

We distributed this questionnaire in August 2020. Several participants mentioned that they were not currently conducting change management implementations because of global lockdowns due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Because it can take years to complete a change management implementation (Phillips, 2021 ), this research does not describe how COVID-19 altered the strategies used by the participants. Furthermore, participants were not provided with definitions of the strategies. Their interpretations of the strategies may differ from the definitions found in the academic literature.

Future Research

Future research should expand upon what strategies the practitioners use to determine (a) how the practitioners use the strategies, and (b) the reasons why practitioners use certain strategies. Participants identified several strategies that they did not use as often as the literature suggested (e.g., provide employees with incentives and adjust the change implementation because of reactions from employees). Future research should investigate why practitioners are not implementing these strategies often.

Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic may have changed how practitioners implemented change management strategies. Future research should investigate if practitioners have added new strategies or changed the frequency in which they identified using the strategies found in this research.

Our aim was to identify a common set of change management strategies found across several models and frameworks and to identify how frequently change management practitioners implement these strategies in practice. While our findings relate to specific models, frameworks, and strategies, we caution readers to consider the environment and situation where the change will occur. Therefore, strategies should not be selected for implementation based on their inclusion in highly cited models and frameworks. Our study identified strategies found in the literature and used by change managers, but it does not predict that specific strategies are more likely to promote a successful organizational change. Although we have presented several strategies, we do not suggest combining these strategies to create a new framework. Instead, these strategies should be used to promote conversation between practitioners and theorists. Additionally, we do not suggest that one model or framework is superior to others because it contains more strategies currently used by practitioners. Evaluating the effectiveness of a model or framework by how many common strategies it contains gives an advantage to models and frameworks that contain the most strategies. Instead, this research identifies what practitioners are doing in the field to steer change management literature towards the strategies that are most used to promote change.

Declarations

This research does not represent conflicting interests or competing interests. The research was not funded by an outside agency and does not represent the interests of an outside party.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jeffrey Phillips, Email: ude.usf@spillihpbj .

James D. Klein, Email: ude.usf@nielkj .

- Ackerman-Anderson, L. S., & Anderson, D. (2001). The change leader’s roadmap: How to navigate your organization’s transformation . Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer.

- Anderson, D., & Ackerman Anderson, L. S. (2001). Beyond change management: Advanced strategies for today’s transformational leaders . Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer.

- Bakari H, Hunjra AI, Niazi GSK. How does authentic leadership influence planned organizational change? The role of employees’ perceptions: Integration of theory of planned behavior and Lewin’s three step model. Journal of Change Management. 2017; 17 (2):155–187. doi: 10.1080/14697017.2017.1299370. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bamford DR, Forrester PL. Managing planned and emergent change within an operations management environment. International Journal of Operations & Production Management. 2003; 23 (5):546–564. doi: 10.1108/01443570310471857. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beckhard, R., & Harris, R. T. (1987). Organizational transitions: Managing complex change (2 nd ed.). Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

- Bridges, W. (1991). Managing transitions: Making the most of change . Perseus Books.

- Buchanan DA, Boddy D. The expertise of the change agent. Prentice Hall; 1992. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bullock RJ, Batten D. It's just a phase we're going through: A review and synthesis of OD phase analysis. Group & Organization Studies. 1985; 10 (4):383–412. doi: 10.1177/105960118501000403. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Burnes, B. (2000). Managing change: A strategic approach to organisational dynamics (3 rd ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Burnes B, By RT. Leadership and change: The case for greater ethical clarity. Journal of Business Ethics. 2012; 108 (2):239–252. doi: 10.1007/s10551-011-1088-2. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carnall, C. A. (2007). Managing change in organizations (5th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Connor, P. E., Lake, L. K., & Stackman, R. W. (2003). Managing organizational change (3 rd ed.). Praeger Publishers.

- Cox AM, Pinfield S, Rutter S. Extending McKinsey’s 7S model to understand strategic alignment in academic libraries. Library Management. 2019; 40 (5):313–326. doi: 10.1108/LM-06-2018-0052. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cummings, T. G., & Worley, C. G. (1993). Organizational development and change (5 th ed.). West Publishing Company.

- Dale, B. & McQuater, R. (1998) Managing business improvement and quality: Implementing key tools and techniques . Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

- Doyle T, Brady M. Reframing the university as an emergent organisation: Implications for strategic management and leadership in higher education. Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management. 2018; 40 (4):305–320. doi: 10.1080/1360080X.2018.1478608. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fowler, F. J., Jr. (2014). Survey research methods: Applied social research methods (5 th ed.). Sage Publications Inc.

- French, W. L., & Bell, C. H. Jr. (1999). Organizational development: Behavioral science interventions for organizational improvement (6 th ed.). Prentice-Hall Inc.

- Gall, M., Gall, J. P., & Borg, W. R. (2003). Educational research: An introduction (7 th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

- Hallencreutz, J., & Turner, D.-M. (2011). Exploring organizational change best practice: Are there any clear-cut models and definitions? International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences , 3 (1), 60–68. 10.1108/17566691111115081 [ CrossRef ]

- Hiatt, J. M. (2006). ADKAR: A model for change in business, government, and our community . Prosci Learning Publications.

- Hughes M. The tools and techniques of change management. Journal of Change Management. 2007; 7 (1):37–49. doi: 10.1080/14697010701309435. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kanter, R. M., Stein, B. A., & Jick, T. D. (1992). The challenge of organizational change . The Free Press.

- Kotter, J. P. (2012). Leading change . Harvard Business Review Press.

- Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science: Selected theoretical papers . Harper & Brothers Publishers.

- Luecke R. Managing change and transition. Harvard Business School Press; 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- McKinsey & Company. (2008). Creating organizational transformations: McKinsey global survey results . McKinsey Quarterly. Retrieved August 5, 2020, from http://gsme.sharif.edu/~change/McKinsey%20Global%20Survey%20Results.pdf

- Mento AJ, Jones RM, Dirndorfer W. A change management process: Grounded in both theory and practice. Journal of Change Management. 2002; 3 (1):45–59. doi: 10.1080/714042520. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nadler, D. A., & Tushman, M. L. (1997). Competing by design: The power of organizational architecture . Oxford University Press.

- Neri RA, Mason CE, Demko LA. Application of Six Sigma/CAP methodology: Controlling blood-product utilization and costs. Journal of Healthcare Management. 2008; 53 (3):183–196. doi: 10.1097/00115514-200805000-00009. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Neves P. Readiness for change: Contributions for employee’s level of individual change and turnover intentions. Journal of Change Management. 2009; 9 (2):215–231. doi: 10.1080/14697010902879178. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pettigrew AM. Theoretical, methodological, and empirical issues in studying change: A response to Starkey. Journal of Management Studies. 1987; 24 :420–426. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pettigrew, A., & Whipp, R. (1991). Managing change for competitive success . Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

- Phillips, J. B. (2021). Change happens: Practitioner use of change management strategies (Publication No. 28769879) [Doctoral dissertation, Florida State University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

- Pless N, Maak T. Building an inclusive diversity culture: Principles, processes and practice. Journal of Business Ethics. 2004; 54 (2):129–147. doi: 10.1007/s10551-004-9465-8. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Polk, J. D. (2011). Lean Six Sigma, innovation, and the Change Acceleration Process can work together. Physician Executive, 37 (1), 38̫–42. [ PubMed ]

- Pollack J, Pollack R. Using Kotter’s eight stage process to manage an organizational change program: Presentation and practice. Systemic Practice and Action Research. 2015; 28 :51–66. doi: 10.1007/s11213-014-9317-0. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Raineri AB. Change management practices: Impact on perceived change results. Journal of Business Research. 2011; 64 (3):266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.11.011. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Saka A. Internal change agents’ view of the management of change problem. Journal of Organizational Change Management. 2003; 16 (5):480–496. doi: 10.1108/09534810310494892. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Strebel P. Why do employees resist change? Harvard Business Review. 1996; 74 (3):86–92. [ Google Scholar ]

- Waterman RH, Jr, Peters TJ, Phillips JR. Structure is not organization. Business Horizons. 1980; 23 (3):14–26. doi: 10.1016/0007-6813(80)90027-0. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

How to Write a Change Proposal? – A Comprehensive Guide

Change proposals are powerful tools that communicate not just the ‘what’ and ‘why’ of change, but also the ‘how’.

Whether you want to improve processes, adopt new technology, or shift strategies, knowing how to create a convincing change proposal is crucial for making your ideas happen.

But writing a change proposal that captures attention, addresses key concerns, and garners support is no small feat.

It requires a blend of strategic thinking, detailed planning, and persuasive communication.

In this blog post, we’ll walk you through every step of how to write a change proposal that not only persuades decision-makers but also lays a clear roadmap for implementation.

Whether you’re a seasoned manager or just starting your career, our comprehensive guide will equip you with the knowledge and tools to write a change proposal that makes an impact.

Let’s dive in and transform your ideas into actionable plans!

What is organizational change?

Organizational change refers to the process through which a company or any other type of organization undergoes a transition to reach a desired future state.

This change can be driven by internal or external factors and can involve a wide range of activities, including but not limited to:

Strategic Changes: These involve changes in the organization’s overarching goals, objectives, mission, or vision. This might include shifting focus to new markets, altering the company’s trajectory, or redefining its business model.

Structural Changes: These changes involve modifications to the organizational structure, such as the hierarchy, departmental configuration, or distribution of responsibilities. This can include mergers, acquisitions, downsizing, or departmental reorganizations.

Process Changes: These kind of changes refer to implementing new or revised methods and procedures for carrying out work. This could involve introducing new technologies, optimizing workflows, or improving efficiency in existing processes.

Cultural Changes: These changes are all about adjusting the organization’s culture, values, and norms. This often focuses on aspects like improving workplace diversity, fostering a more inclusive environment, or changing the organizational mindset and attitudes.

People Changes: Changes relating to personnel, including leadership transitions, staff retraining, role redefinitions, or changes in staff motivation and engagement methods.

What is Change Proposal?

A Change Proposal is a formal suggestion put forward to modify existing methods, processes, structures, or strategies within an organization.

It is a structured plan that outlines the need for change, the proposed adjustments, and the expected outcomes.

A well-crafted Change Proposal is crucial for gaining support and approval from decision-makers and stakeholders. It demonstrates a thoughtful, strategic approach to making improvements and is essential for successful change management in any organization.

Learn more about: A Step-by-Step Guide for Organizational Change Proposal

Why is it important to write a change proposal?

Writing a change proposal is an essential step in the process of organizational change. It serves several important functions, each contributing to the success and smooth implementation of the proposed changes:

Provides a Structured Approach:

A change proposal creates a structured framework for considering and implementing change. It compels the proposer to thoroughly analyze the current situation, identify specific issues or opportunities, and develop a detailed plan for addressing them.

This structured approach ensures that all aspects of the change are carefully thought out, including objectives, resources needed, potential risks, and the impact on various stakeholders.

Facilitates Clear Communication:

Effective communication is vital for successful change. A good change proposal clearly explains why the change is needed, its benefits, and how it will happen. It’s kind of a reference document for change idea that everyone can reflect on and discuss, express their feedback and concerns.

Helps in Gaining Support and Approval:

For any change to be implemented, it often requires the approval and support of various stakeholders, including top management, employees, and sometimes external parties like investors or board members. A comprehensive change proposal demonstrates the thought and analysis that has gone into the proposed change.

It shows that the proposer has considered the implications and is prepared to manage the risks. This thoroughness and professionalism can be crucial in persuading decision-makers and gaining their buy-in.

Enables Effective Planning and Resource Allocation:

A change proposal outlines the resources—such as time, budget, and personnel—required to implement the change. This allows for effective planning and allocation of resources, ensuring that the change process is not hindered by resource constraints. The proposal can also serve as a guide to prioritize activities and allocate resources in a way that maximizes efficiency and impact.

Assists in Risk Management:

By requiring a detailed risk assessment, a change proposal helps in identifying potential challenges and obstacles that could impede the success of the change. This proactive identification allows for the development of mitigation strategies and contingency plans.

Provides a Basis for Evaluation:

A change proposal sets out specific goals and metrics for evaluating the success of the change. This provides a clear basis for ongoing evaluation and allows the organization to measure progress, assess the effectiveness of the change, and make necessary adjustments. Regular evaluation based on the initial proposal ensures that the change remains aligned with organizational objectives and delivers the intended outcomes.

15 Key Sections of Change Proposal

Here is the breakdown of key sections that will guide you about how to write a change proposal.

1. Identification of the problem or Need of Change:

The first element of a change proposal, the identification of the problem or need for change, is foundational in setting the stage for the entire proposal. This step involves a comprehensive analysis of the current state of affairs to pinpoint specific issues or areas where improvement is necessary.

It requires a deep understanding of the organization’s operations, market conditions, internal challenges, or external opportunities that prompt the need for change.

The identification process is not merely about stating a problem; it’s about articulating it clearly and precisely, often backed by data, insights, and a thorough understanding of its implications.

This clarity is crucial as it directly influences the direction of the proposed solution, ensuring that the change initiative is relevant, targeted, and addresses real issues that impact the organization’s performance or potential.

Learn more about: Identifying the Need for Change in an Organizationa – Explained

2. Stating Goals and Objectives of Change:

Sating the goals and objectives of the change is a crucial because it defines what the change aims to achieve. It provides a clear target for the proposed actions. Goals and objectives should be SMART: specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound.

This ensures they are clear and realistic, aligning with the organization’s strategic direction.

Well-defined goals and objectives serve as a guidepost throughout the change process, helping to keep the project on track, measure progress, and evaluate success upon completion.

They also play a vital role in communicating the purpose of the change to stakeholders, helping to build understanding, support, and engagement with the change initiative.

3. Rationale of Change:

This part of the section delves into the reasoning behind the proposed change. It involves explaining why the change is necessary and timely. This could be due to various factors such as evolving market dynamics, internal operational challenges, technological advancements, compliance requirements, or to leverage new opportunities.

The rationale should be backed by solid evidence, data, and analysis to make a compelling case. It’s about connecting the dots between the current challenges or opportunities (identified in the initial part of the proposal) and the proposed solution, showing how the latter addresses the former.

4. Proposed Solution or Approach:

The “Proposed Solution or Approach” is a crucial element of a change proposal, as it outlines the specific strategies or actions that will be implemented to achieve the defined goals and objectives.

This section goes into the details of the ‘how’ – how the change will be executed, what methodologies will be used, and what steps will be taken to transition from the current state to the desired future state.

It should include a clear description of the proposed changes, whether they involve new processes, technologies, organizational structures, or behavioral shifts.

A well-articulated solution should be logical, feasible, and backed by research and analysis. It should address the issues or opportunities identified in the first element of the proposal and align with the goals and objectives stated in the second element.

This part of the proposal often includes an outline of the anticipated phases or stages of implementation.

5. Benefits of Change:

The change proposal should enumerate the benefits of the proposed change. These benefits should be specific, quantifiable (where possible), and directly tied to the goals and objectives previously outlined.

Benefits could range from improved efficiency, cost savings, increased revenue, better customer satisfaction, enhanced employee morale, to staying competitive in the market.

The key here is to articulate these benefits in a way that resonates with the stakeholders, clearly showing the value addition or positive impact the change will bring.

This section essentially answers the ‘what’s in it for us’ question that most stakeholders will have. It’s about painting a picture of a better future post-change, providing a persuasive argument that the benefits of the change outweigh the costs and efforts involved.

Learn more about: Step-by-Step Guide to Calculate ROI of Change Management

6. A Detailed Implementation Plan:

The implementation plan is a pivotal element of a change proposal. It is a roadmap outlining how the proposed change will be put into action. It breaks down the somewhat abstract concepts of the proposal into concrete, actionable steps, making the change process more manageable and understandable.

It describes what will be done, how it will be done, and by whom. These steps should be clearly defined and sequenced logically to ensure a smooth transition from the current state to the desired future state.

7. Roles and Responsibilities:

This part assigns clear responsibilities to individuals or teams. It specifies who is responsible for what, ensuring accountability and clarity in the execution of the plan. Identifying the right people for the right tasks and empowering them with the necessary authority and resources is key to effective implementation.

8. Resource Allocation:

Here, the proposal details the resources required for the implementation – including personnel, technology, finances, and other materials. It also explains how these resources will be allocated, ensuring that the project has everything it needs to proceed smoothly.

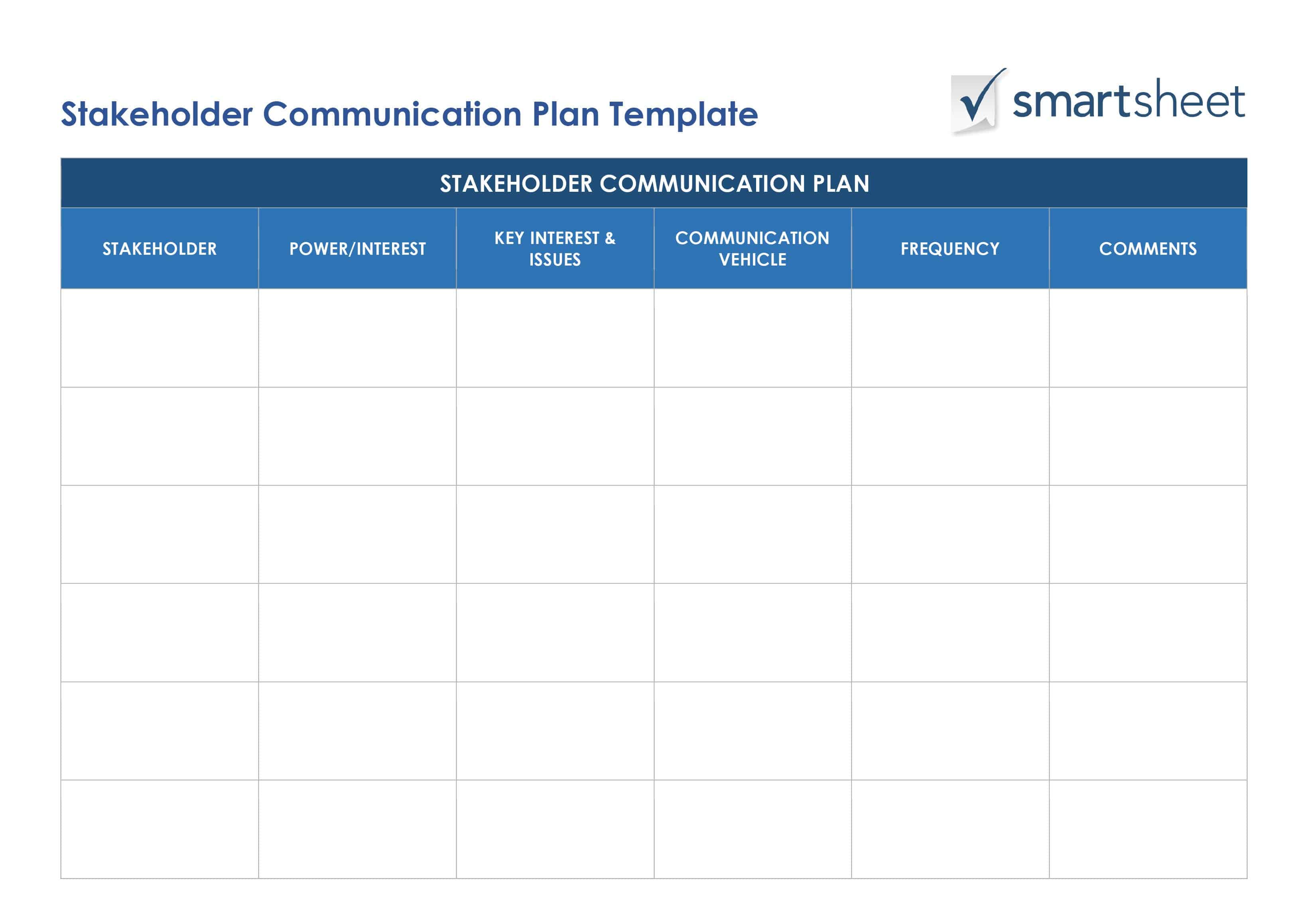

9. Communication Plan:

A communication plan is essential for keeping everyone informed and engaged. It should detail how the changes will be communicated to different stakeholders, including the frequency and methods of communication. Effective communication helps in managing expectations, reducing resistance, and ensuring buy-in.

10: Budget:

This section outlines the financial and material requirements necessary to successfully implement the proposed change. This element provides a detailed estimation of the costs associated with the change and identifies the resources needed to support it.

This involves a detailed breakdown of all the costs associated with the proposed change. It includes direct costs like materials, technology, and additional personnel, as well as indirect costs such as training and potential downtime during implementation. The cost estimation should be as accurate and realistic as possible to avoid unexpected expenses that could derail the project.

11. Cost-Benefit Analysis:

To strengthen the case for the proposed change, this section can also include a cost-benefit analysis. This analysis compares the costs of implementing the change against the benefits it will bring, providing a clear picture of the return on investment. This is particularly important for stakeholders and decision-makers who are assessing the proposal from a financial perspective.

Learn more about: How to Estimate Cost of Change Management

12. Risk Assessment and Mitigation:

This section outlines possible risks that might arise during the implementation of the change. Risks can vary widely depending on the nature of the change and can include operational, financial, technological, legal, and human resource-related risks, among others.

The goal is to anticipate any factor that could potentially disrupt the change process or prevent the achievement of its objectives.

For each significant risk identified, the proposal should outline specific strategies or actions to mitigate that risk.

Mitigation strategies might include contingency plans, alternative courses of action, additional resources or buffers, training and communication plans, or any other steps that can reduce the likelihood of the risk occurring or lessen its impact if it does occur.

Learn more about: How to Conduct Change Management Risk Assessment?

13. Communication Plan :

The core of this section is a comprehensive plan detailing how, when, and what will be communicated to each stakeholder group.

The communication plan should outline the key messages, communication channels (e.g., meetings, emails, newsletters), frequency of communication, and the person responsible for communicating with each stakeholder group.

The plan should be designed to keep stakeholders informed, engaged, and supportive, addressing their concerns and expectations.

Learn more about: 08 Steps to Create Communication Plan in Change Management

14. Evaluation and Performance Metrics:

The “Evaluation and Performance Metrics” section of a change proposal is vital for measuring the success and effectiveness of the implemented changes. This element sets out the criteria and methods that will be used to assess whether the change has achieved its intended objectives.

The proposal should specify clear, quantifiable metrics or key performance indicators (KPIs) that will be used to evaluate the success of the change. These metrics should be directly linked to the goals and objectives stated earlier in the proposal.

Learn more about: Change Management KPIs Examples

15. Timeline:

A well-defined timeline is crucial. It should provide a schedule for each stage of the implementation process, offering a clear sense of the time frame for the change. The timeline needs to be realistic, allowing enough time for each step while maintaining momentum

Tips for Writing a Winning Change Proposal

A winning change proposal is one that is thoughtfully prepared, clearly presented, and thoroughly researched. It addresses the concerns and interests of its audience, provides a clear rationale and plan for the change, and demonstrates a proactive approach to managing risks and measuring success.

Here are some useful tips that would help you to how a write a winning change proposal.

Understand Your Audience:

Tailor your proposal to the interests and concerns of your audience, which typically includes decision-makers, stakeholders, and those who will be affected by the change. Understanding their perspectives, priorities, and potential reservations helps in framing the proposal in a way that resonates with them.

Be Clear and Concise:

Clarity and conciseness are key. Avoid jargon and overly technical language; instead, use clear, simple terms that are easily understood. Focus on being direct and to the point, providing all necessary information without unnecessary elaboration. A well-structured, logical flow of ideas makes your proposal easier to follow and understand, thereby increasing its persuasiveness.

Back Up Claims with Data:

Support your proposal with solid data and evidence. This includes market research, case studies, statistical analyses, or any relevant data that underpins the need for change and the potential benefits. This not only lends credibility to your proposal but also demonstrates that you have done your homework and are proposing a change based on thoughtful analysis and evidence.

Present a Realistic Implementation Plan:

Your proposal should include a detailed, realistic plan for how the change will be implemented. This should cover the timeline, resource allocation, roles and responsibilities, and a step-by-step guide to the implementation process. A practical and well-thought-out plan shows that you have considered the logistical aspects of the change, making your proposal more convincing.

Address Potential Risks and Resistance:

Acknowledge potential risks and challenges and provide a plan for how these will be mitigated or managed. Demonstrating that you have considered possible obstacles and have prepared for them shows foresight and responsibility. Also, anticipate potential resistance to the change and suggest strategies for managing this, such as through stakeholder engagement and communication plans.

Final Words

In conclusion, learning how to write a change proposal is an invaluable skill in today’s dynamic business environment. A well-crafted proposal is more than just a document; it’s a roadmap for transformation and a tool for communication and alignment. By following the guidelines and tips discussed in this post, you’re well on your way to mastering the art of writing a change proposal that not only wins support but also drives meaningful change.

About The Author

Tahir Abbas

Related posts.

3 Cs of Change Management – Communication, Collaboration and Commitment

How to Develop 30 60 90 Day Plan for Team Leader? – Practical Tips

Identifying the Need for Change in an Organization – Explained

How To Write A Change Management Proposal

Change Strategists

Affiliate Disclaimer

As an affiliate, we may earn a commission from qualifying purchases. We get commissions for purchases made through links on this website from Amazon and other third parties.

If you are looking to initiate change within your organization, writing a change management proposal is a crucial step in the process.

A well-written proposal outlines the need for change, identifies the problem, proposes a solution, and provides a plan for implementation.

It is important to approach this task in a methodical and organized manner to ensure that your proposal is clear, concise, and effective in achieving your desired outcome.

When writing a change management proposal, it is important to clearly define the problem or issue to be addressed, outline the proposed change and its objectives, and detail the steps and resources required to implement the change. It is also important to identify potential risks and challenges and develop a plan for mitigating them.

The proposal should be backed by research and data, and should include a clear timeline and budget. Communication and stakeholder engagement strategies should also be included to ensure buy-in and support for the proposed change.

In this article, you will learn how to write a change management proposal that effectively communicates the need for change, proposes a viable solution, and addresses potential resistance and risk.

By following the steps outlined in this guide, you will be able to develop a comprehensive proposal that outlines the benefits of your proposed change, identifies potential challenges, and provides a clear plan for implementation.

Whether you are proposing a small change or a major organizational overhaul, this guide will provide you with the tools and strategies you need to ensure that your proposal is successful.

Understanding the Importance of Change Management Proposals

Understanding why it’s crucial to put together a plan for introducing new ways of doing things is key to getting everyone on board.

A change management proposal can help ensure that the transition from old to new is smooth and seamless. This proposal serves as a roadmap that outlines the steps involved in implementing change and communicating it effectively to all stakeholders.

The importance of change management communication cannot be overstated. Having a clear and concise communication plan helps to ensure that everyone understands what’s happening and why. This includes employees, customers, suppliers, and other stakeholders.

It’s important to keep all parties informed throughout the process to avoid any confusion or resistance.

Change management best practices for successful implementation should also be incorporated into the proposal. This includes involving key stakeholders in the planning process, identifying potential risks and challenges, and having a plan to mitigate them.

It’s also important to have a plan in place to measure the success of the change and make any necessary adjustments along the way. By following these best practices, you can increase the chances of a successful implementation and minimize any negative impacts on the organization.

Remember, introducing change can be difficult for some people, so it’s important to approach it in a methodical and organized way. By putting together a well-written change management proposal, you can help mitigate any resistance and ensure that everyone is on board with the new direction. So, take the time to do it right, and you’ll be well on your way to a successful change implementation.

Identifying the Need for Change

We’ve gotta figure out what’s not working and fix it if we wanna make things better around here. Change is necessary, but it should be approached with caution to ensure that it has a positive impact.

Before proposing any changes, it’s important to identify the challenges that need to be addressed.

Some of the common challenges that organizations face include outdated technology, inefficient processes, and poor communication between departments. Take the time to assess the impact of these challenges on the organization as a whole and determine how they can be addressed through change.

To identify the need for change, it’s important to involve all stakeholders in the process. This includes employees, managers, customers, and suppliers. Gather feedback from each group to get a complete picture of the challenges that need to be addressed. This can be done through surveys, focus groups, or one-on-one meetings.

Once you have a clear understanding of the challenges, prioritize them based on their impact on the organization and the ease of implementation. Assessing the impact of the challenges is an important step in the change management process. This involves determining how the challenges are affecting the organization’s bottom line, customer satisfaction, and employee morale.

It’s important to quantify the impact of the challenges to justify the need for change. Use data and metrics to support your proposal and show how the proposed changes will improve the organization’s performance. By identifying the need for change and assessing its impact, you can create a compelling change management proposal that’ll help your organization move forward.

Defining the Problem Statement

Defining the problem statement is crucial for pinpointing the root cause of organizational challenges and finding effective solutions to improve performance. Before writing a change management proposal, it’s important to conduct a problem analysis to identify what needs to be changed and why.

This involves examining the current situation, gathering data, and identifying the gap between the desired and actual state. Once the problem has been identified, it’s important to conduct a root cause analysis to determine the underlying reasons for the problem.

A problem statement should be clear, concise, and specific. It should describe the problem in enough detail to provide a clear understanding of its impact on the organization and its stakeholders.

Example problem statements:

- “The current software update process is causing frequent disruptions to employee productivity due to unexpected system downtimes, resulting in increased frustration among staff and delayed project timelines.”

- “Inadequate communication channels between departments are leading to misunderstandings and delays in project execution, resulting in decreased collaboration and suboptimal project outcomes.”

- “The lack of standardized procedures for onboarding new employees is resulting in inconsistent training experiences and longer ramp-up periods, leading to decreased employee satisfaction and retention rates.”

- “The current organizational structure is hindering cross-functional collaboration and decision-making, resulting in duplicated efforts, conflicting priorities, and missed opportunities for innovation.”

- “Inefficient inventory management practices are causing overstocking of certain items and stockouts of others, leading to increased carrying costs, decreased customer satisfaction, and lost sales opportunities.”

A well-defined problem statement helps to focus attention on the issue at hand and guides the development of an effective change management proposal. It also helps to ensure that the proposed solution addresses the root cause of the problem, rather than just the symptoms.

To define an effective problem statement, it’s important to involve stakeholders and gather their input. This helps to ensure that the problem is viewed from different perspectives and that the proposed solution is acceptable to all parties involved.

In addition, involving stakeholders in the problem definition process helps to build consensus and support for the proposed change. By taking the time to define the problem statement, you can increase the chances of success for your change management proposal.

Proposing a Solution

Now it’s time for you to propose a solution that effectively addresses the identified problem and meets the needs of all stakeholders involved. Crafting solutions requires a thorough understanding of the problem statement and the goals of the organization. You need to present recommendations that are feasible, practical, and aligned with the company’s vision and mission.

To propose a solution, you need to consider the following three items:

Identify the root cause of the problem: Before presenting recommendations, you need to identify the root cause of the problem. This will help you to develop solutions that address the underlying issue rather than just the symptoms. You can use tools such as fishbone diagrams, root cause analysis, and brainstorming sessions to identify the root cause.

Develop a plan of action: Once you have identified the root cause, you need to develop a plan of action. This plan should include specific steps that need to be taken to address the problem. You should also identify the resources required, the timeline, and the expected outcomes.

Communicate the plan: Finally, you need to communicate the plan to all stakeholders involved. This includes employees, managers, and other relevant parties. You should explain the rationale behind the plan, the expected outcomes, and the benefits to the organization. You should also address any concerns or questions that stakeholders may have.

In conclusion, proposing a solution requires a methodical approach that considers the needs of all stakeholders involved. By identifying the root cause of the problem, developing a plan of action, and communicating the plan effectively, you can craft solutions that effectively address the identified problem and meet the needs of the organization.

Developing an Implementation Plan

When developing an implementation plan, it’s important to define the scope of the change to ensure that everyone is on the same page.

You’ll need to identify the resources required for the change, including personnel, equipment, and funding.

Additionally, you should create a timeline that outlines the key milestones and deadlines for the project.

By taking a methodical approach, you’ll be able to ensure that the change is implemented smoothly and effectively.

Defining the Scope of the Change

Defining the scope of the change is essential to ensure a smooth transition. This involves setting project boundaries and conducting a requirements analysis to identify the specific areas that will be impacted by the change. By doing this, you can allocate the necessary resources, such as time and budget, appropriately.

Defining the scope of the change also helps prioritize tasks and create a timeline for implementation. This allows you to break down the change into manageable steps and ensure completion of each step before moving on to the next. Additionally, it helps communicate the change to stakeholders and obtain their buy-in by outlining how the proposed alterations will impact them and the organization as a whole.

Taking the time to define the scope of the change can increase the likelihood of a successful implementation and minimize the risk of unexpected setbacks.

Identifying the Resources and Timeline

You’re embarking on a journey to bring your vision to life, and it’s important to identify the resources and timeline that will help you reach your destination smoothly. Resource allocation is crucial for any change management proposal, as it determines the availability of personnel, tools, and equipment needed to execute the plan.

To identify the resources needed, consider the following:

- Determine the current resources available and assess whether they’re sufficient for the proposed change.

- Identify the additional resources needed to execute the plan, such as personnel, equipment, and technology.

- Allocate resources based on priority and criticality of tasks.

- Ensure that the resources are available at the right time and place.

- Monitor resource utilization to ensure that they’re used efficiently.

Time management is also essential for any change management proposal. A timeline provides a roadmap for executing the plan and ensures that everyone involved in the project is aware of the deadlines and milestones.

To manage time effectively, consider the following:

- Create a detailed timeline that outlines the major milestones and deadlines.

- Identify potential roadblocks and risks that may affect the timeline and develop contingency plans.

- Communicate the timeline to all stakeholders involved in the project.

- Monitor the timeline regularly to ensure that the project stays on track.

- Adjust the timeline as needed to accommodate changes or delays.

By identifying the resources and timeline needed for your change management proposal, you increase your chances of success. Resource allocation and time management are crucial for executing any plan smoothly and efficiently. By following the steps outlined above, you can ensure that your proposal is executed on time and within budget.

Identifying Key Stakeholders

Identifying the crucial stakeholders is essential in any plan to implement modifications within an organization. The process of stakeholder analysis helps you to identify who has a stake in the change and who will be affected by it.

These stakeholders can include employees, customers, suppliers, shareholders, and even the general public. Once you have identified the stakeholders, you need to analyze their needs, expectations, and potential reactions to the change. This will help you to develop effective communication strategies to engage them throughout the change process.

Communication is a critical component of any change management proposal, and it’s vital to identify key stakeholders before developing a communication strategy. The communication plan should be tailored to the specific needs and expectations of each stakeholder group.

For example, employees may need more detailed and frequent communication than external stakeholders. Suppliers may need assurance of continued business, while customers may require reassurance about the quality and availability of products or services.

By identifying the key stakeholders and developing a communication strategy that meets their needs, you can minimize resistance and promote a smooth transition to the proposed changes.

In summary, identifying key stakeholders is a critical step in developing a change management proposal. Stakeholder analysis helps you to identify who will be affected by the change and to understand their needs, expectations, and potential reactions.

Developing a communication strategy that meets the specific needs of each stakeholder group is essential to minimizing resistance and promoting a smooth transition. By following these steps, you can increase the likelihood of success in implementing the proposed changes.

Addressing Resistance to Change

Don’t let resistance derail your progress – learn how to overcome it and successfully implement your vision.

Resistance to change is a common occurrence in any organization, and it can come from different sources. It can be from employees, managers, or even customers. Regardless of the source, it’s important to address resistance to change to ensure that your change management proposal is successful.

Overcoming resistance starts with building support. You need to communicate your vision clearly and make sure that everyone understands why the change is necessary. You should also involve key stakeholders in the planning process.

By doing so, you can get their input and address their concerns early on. When stakeholders feel heard and involved, they’re more likely to support the change.

Another way to overcome resistance is to provide training and support. People are often resistant to change because they feel unsure or unprepared. By providing training and support, you can help people feel more comfortable with the change and increase their confidence in their ability to adapt.

You can also provide ongoing support to help people navigate the change and address any issues that arise. By addressing resistance to change head-on and building support, you can increase the likelihood of successfully implementing your change management proposal.

Assessing Risk and Mitigating Issues

As you navigate through this section, you’ll discover how to identify potential roadblocks and develop strategies to ensure your vision is smoothly executed, like a skilled captain navigating through rough waters.

Risk assessment is a crucial aspect of change management, and it involves identifying potential issues that could arise during the implementation process. This stage requires a detailed review of the project plan, stakeholder feedback, and organizational culture to determine the likelihood and potential impact of potential risks.

Once you’ve identified potential risks, the next step is to develop strategies to mitigate these issues. This stage involves creating a risk management plan that outlines the steps to be taken to minimize the impact of potential risks. Risk mitigation strategies may include developing contingency plans, establishing communication protocols, or providing training to stakeholders.

It’s essential to ensure that the risk management plan is flexible enough to adapt to changing circumstances and that stakeholders are aware of their roles and responsibilities in the process.

In conclusion, assessing risk and mitigating issues are critical components of any change management proposal. It’s essential to take a methodical approach to identify potential roadblocks and develop strategies to overcome them. By creating a comprehensive risk management plan, you can mitigate the impact of potential risks and ensure a smooth transition to the proposed changes. Remember, change management isn’t just about implementing structural changes; it’s about ensuring that your organization is equipped to handle these changes effectively.

Establishing Evaluation Metrics

Now it’s time for you to establish evaluation metrics, so you can measure the effectiveness of the changes you’ve implemented. Measuring effectiveness is crucial to determine if your vision has been achieved and if there are any areas that require further improvement.

Evaluation metrics can include data analysis, surveys, feedback from employees and stakeholders, and other relevant metrics. It’s important to establish these metrics before implementing any changes, so you have a baseline to compare against.

Data analysis is a critical component of establishing evaluation metrics. It helps you identify trends, patterns, and areas that require improvement. You can use various data sources, such as financial data, customer satisfaction surveys, and employee engagement surveys, among others.

Once you have collected the data, you need to analyze it and interpret the results. This will help you identify areas that require improvement and make necessary changes to your change management proposal.

In summary, establishing evaluation metrics is a crucial step in change management. Measuring effectiveness is essential to determine if your vision has been achieved and if there are any areas that require further improvement.

Data analysis is a critical component of establishing evaluation metrics. It helps you identify trends, patterns, and areas that require improvement. By using these techniques, you can improve your change management proposal and ensure that your changes are successful.