Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 17 April 2014

How does the bilingual experience sculpt the brain?

- Albert Costa 1 , 2 , 3 &

- Núria Sebastián-Gallés 1

Nature Reviews Neuroscience volume 15 , pages 336–345 ( 2014 ) Cite this article

22k Accesses

239 Citations

131 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cognitive control

- Neural circuits

The ability to speak two languages often marvels monolinguals, although bilinguals report no difficulties in achieving this feat. Here, we examine how learning and using two languages affect language acquisition and processing as well as various aspects of cognition. We do so by addressing three main questions. First, how do infants who are exposed to two languages acquire them without apparent difficulty? Second, how does language processing differ between monolingual and bilingual adults? Last, what are the collateral effects of bilingualism on the executive control system across the lifespan? Research in all three areas has not only provided some fascinating insights into bilingualism but also revealed new issues related to brain plasticity and language learning.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

176,64 € per year

only 14,72 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

How bilingualism modulates selective attention in children

Language combinations of multilinguals are reflected in their first-language knowledge and processing

A comparison of language control while switching within versus between languages in younger and older adults

Grosjean, F. What bilingualism is NOT. Multilingual Living [online] , (2010).

Google Scholar

Genesee, F. Bilingual first language acquisition: exploring the limits of the language faculty. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 21 , 153–168 (2001).

Article Google Scholar

Gervain, J. & Mehler, J. Speech perception and language acquisition in the first year of life. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 61 , 191–218 (2010).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Kuhl, P. K. Brain mechanisms in early language acquisition. Neuron 67 , 713–727 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Byers-Heinlein, K., Burns, T. C. & Werker, J. F. The roots of bilingualism in newborns. Psychol. Sci. 21 , 343–348 (2010).

Nazzi, T., Bertoncini, J. & Mehler, J. Language discrimination by newborns: toward an understanding of the role of rhythm. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 24 , 756–766 (1998).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ramus, F., Hauser, M., Miller, C., Morris, D. & Mehler, J. Language discrimination by human newborns and by cotton-top tamarin monkeys. Science 288 , 349–351 (2000).

Toro, J., Trobalon, J. & Sebastian-Galles, N. The use of prosodic cues in language discrimination tasks by rats. Animal Cogn. 6 , 131–136 (2003).

Bosch, L. & Sebastian-Galles, N. Native-language recognition abilities in 4-month-old infants from monolingual and bilingual environments. Cognition 65 , 33–69 (1997).

Bosch, L. & Sebastian-Galles, N. Evidence of early language discrimination abilities in infants from bilingual environments. Infancy 2 , 29–49 (2001).

Nazzi, T., Jusczyk, P. W. & Johnson, E. K. Language discrimination by English-learning 5-month-olds: effects of rhythm and familiarity. J. Mem. Lang. 43 , 1–19 (2000).

Calvert, G. A. et al. Activation of auditory cortex during silent lipreading. Science 276 , 593–596 (1997).

van Wassenhove, V., Grant, K. W. & Poeppel, D. Visual speech speeds up the neural processing of auditory speech. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102 , 1181–1186 (2005).

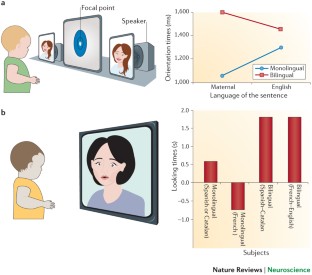

Weikum, W. M. et al. Visual language discrimination in infancy. Science 316 , 1159–1159 (2007).

Sebastian-Galles, N., Albareda-Castellot, B., Weikum, W. M. & Werker, J. F. A bilingual advantage in visual language discrimination in infancy. Psychol. Sci. 23 , 994–999 (2012).

Kuhl, P. K. Early language acquisition: cracking the speech code. Nature Rev. Neurosci. 5 , 831–843 (2004).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kuhl, P. K. et al. Infants show a facilitation effect for native language phonetic perception between 6 and 12 months. Dev. Sci. 9 , F13–F21 (2006).

Albareda-Castellot, B., Pons, F. & Sebastian-Galles, N. The acquisition of phonetic categories in bilingual infants: new data from an anticipatory eye movement paradigm. Dev. Sci. 14 , 395–401 (2011).

Burns, T. C., Yoshida, K. A., Hill, K. & Werker, J. F. The development of phonetic representation in bilingual and monolingual infants. Appl. Psycholinguist. 28 , 455–474 (2007).

Sundara, M., Polka, L. & Molnar, M. Development of coronal stop perception: bilingual infants keep pace with their monolingual peers. Cognition 108 , 232–242 (2008).

Petitto, L. A. et al. The “Perceptual Wedge Hypothesis” as the basis for bilingual babies' phonetic processing advantage: new insights from fNIRS brain imaging. Brain Lang. 121 , 130–143 (2012).

Anderson, J. L., Morgan, J. L. & White, K. S. A statistical basis for speech sound discrimination. Lang. Speech 46 , 155–182 (2003).

Jusczyk, P. W., Friederici, A. D., Wessels, J., Svenkerud, V. Y. & Jusczyk, A. M. Infants' sensitivity to the sound patterns of native language words. J. Mem. Lang. 32 , 402–420 (1993).

Sebastian-Galles, N. & Bosch, L. Building phonotactic knowledge in bilinguals: role of early exposure. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 28 , 974–989 (2002).

Markman, E. & Wachtel, G. Children's use of mutual exclusivity to constrain the meanings of words. Cogn. Psychol. 20 , 121–157 (1988).

Byers-Heinlein, K. & Werker, J. Monolingual, bilingual, trilingual: infants' language experience influences the development of a word-learning heuristic. Dev. Sci. 12 , 815–823 (2009).

Byers-Heinlein, K. & Werker, J. Lexicon structure and the disambiguation of novel words: evidence from bilingual infants. Cognition 128 , 407–416 (2013).

Houston-Price, C., Caloghiris, Z. & Raviglione, E. Language experience shapes the development of the mutual exclusivity bias. Infancy 15 , 125–150 (2010).

Hoff, E. et al. Dual language exposure and early bilingual development. J. Child Lang. 39 , 1–27 (2012).

Core, C., Hoff, E., Rumiche, R. & Señor, M. Total and conceptual vocabulary in Spanish–English bilinguals from 22 to 30 months: implications for assessment. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 56 , 1637–1649 (2013).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bialystok, E., Craik, F. I. M. & Luk, G. Bilingualism: consequences for mind and brain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16 , 240–250 (2012).

Pavlenko, A. & Malt, B. C. Kitchen Russian: cross-linguistic differences and first-language object naming by Russian–English bilinguals. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 14 , 19–45 (2011).

Gollan, T. & Acenas, L. What is a TOT? Cognate and translation effects on tip-of-the-tongue states in Spanish–English and Tagalog–English bilinguals. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 30 , 246–269 (2004).

Ivanova, I. & Costa, A. Does bilingualism hamper lexical access in speech production? Acta Psychol. 127 , 277–288 (2008).

Sadat, J., Martin, C. D., Alario, F. X. & Costa, A. Characterizing the bilingual disadvantage in noun phrase production. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 41 , 159–179 (2012).

Gollan, T., Montoya, R. & Werner, G. Semantic and letter fluency in Spanish–English bilinguals. Neuropsychology 16 , 562–576 (2002).

Runnqvist, E., Gollan, T. H., Costa, A. & Ferreira, V. S. A disadvantage in bilingual sentence production modulated by syntactic frequency and similarity across languages. Cognition 129 , 256–263 (2013).

García-Sierra, A., Ramírez-Esparza, N., Silva-Pereyra, J., Siard, J. & Champlin, C. A. Assessing the double phonemic representation in bilingual speakers of Spanish and English: an electrophysiological study. Brain Lang. 121 , 194–205 (2012).

Gollan, T. H., Montoya, R. I., Cera, C. & Sandoval, T. C. More use almost always means a smaller frequency effect: aging, bilingualism, and the weaker links hypothesis. J. Mem. Lang. 58 , 787–814 (2008).

Baus, C., Costa, A. & Carreiras, M. On the effects of second language immersion on first language production. Acta Psychol. 142 , 402–409 (2013).

Schmid, M. S. Languages at play: the relevance of L1 attrition to the study of bilingualism. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 13 , 1–7 (2010).

Pallier, C. et al. Brain imaging of language plasticity in adopted adults: can a second language replace the first? Cereb. Cortex 13 , 155–161 (2003).

Green, D. W. Mental control of the bilingual lexico-semantic system. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 1 , 67–81 (1998).

Kroll, J. F., Bobb, S. C., Misra, M. & Guo, T. Language selection in bilingual speech: evidence for inhibitory processes. Acta Psychol. 128 , 416–430 (2008).

Colome, A. Lexical activation in bilinguals' speech production: language-specific or language-independent? J. Mem. Lang. 45 , 721–736 (2001).

Thierry, G. & Wu, Y. J. Brain potentials reveal unconscious translation during foreign-language comprehension. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104 , 12530–12535 (2007).

Spivey, M. J. & Marian, V. Cross talk between native and second languages: partial activation of an irrelevant lexicon. Psychol. Sci. 10 , 281–284 (1999).

Kovelman, I., Baker, S. A. & Petitto, L. Bilingual and monolingual brains compared: a functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation of syntactic processing and a possible “neural signature” of bilingualis. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 20 , 153–169 (2008).

Kovelman, I., Shalinsky, M. H., Berens, M. S. & Petitto, L. Shining new light on the brain's “bilingual signature”: a functional near infrared spectroscopy investigation of semantic processing. Neuroimage 39 , 1457–1471 (2008).

Crinion, J. et al. Language control in the bilingual brain. Science 312 , 1537–1540 (2006).

Nosarti, C., Mechelli, A., Green, D. W. & Price, C. J. The impact of second language learning on semantic and nonsemantic first language reading. Cereb. Cortex 20 , 315–327 (2010).

Parker Jones, O. et al. Where, when and why brain activation differs for bilinguals and monolinguals during picture naming and reading aloud. Cereb. Cortex 22 , 892–902 (2012).

Abutalebi, J. Neural aspects of second language representation and language control. Acta Psychol. 128 , 466–478 (2008).

Abutalebi, J. et al. Language control and lexical competition in bilinguals: an event-related fMRI study. Cereb. Cortex 18 , 1496–1505 (2008).

Abutalebi, J. & Green, D. Bilingual language production: the neurocognition of language representation and control. J. Neurolinguist. 20 , 242–275 (2007).

Garbin, G. et al. Neural bases of language switching in high and early proficient bilinguals. Brain Lang. 119 , 129–135 (2011).

Zou, L., Ding, G., Abutalebi, J., Shu, H. & Peng, D. Structural plasticity of the left caudate in bimodal bilinguals. Cortex 48 , 1197–1206 (2012).

Krizman, J., Marian, V., Shook, A., Skoe, E. & Kraus, N. Subcortical encoding of sound is enhanced in bilinguals and relates to executive function advantages. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109 , 7877–7881 (2012).

Mechelli, A. et al. Neurolinguistics: structural plasticity in the bilingual brain. Nature 431 , 757 (2004).

Abutalebi, J. et al. The role of the left putamen in multilingual language production. Brain Lang. 125 , 307–315 (2013).

Ressel, V. et al. An effect of bilingualism on the auditory cortex. J. Neurosci. 32 , 16597–16601 (2012).

García-Pentón, L., Pérez Fernández, A., Iturria-Medina, Y., Gillon-Dowens, M. & Carreiras, M. Anatomical connectivity changes in the bilingual brain. Neuroimage 84 , 495–504 (2014).

Luk, G., Bialystok, E., Craik, F. I. M. & Grady, C. L. Lifelong bilingualism maintains white matter integrity in older adults. J. Neurosci. 31 , 16808–16813 (2011).

Miyake, A. et al. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: a latent variable analysis. Cogn. Psychol. 41 , 49–100 (2000).

Shallice, T. & Burgess, P. The domain of supervisory processes and temporal organization of behaviour. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 351 , 1405–1411 (1996).

Bialystok, E., Craik, F. I. M., Klein, R. & Viswanathan, M. Bilingualism, aging, and cognitive control: evidence from the Simon task. Psychol. Aging 19 , 290–303 (2004).

Costa, A., Hernandez, M. & Sebastian-Galles, N. Bilingualism aids conflict resolution: evidence from the ANT task. Cognition 106 , 59–86 (2008).

Costa, A., Hernandez, M., Costa-Faidella, J. & Sebastian-Galles, N. On the bilingual advantage in conflict processing: now you see it, now you don't. Cognition 113 , 135–149 (2009).

Bialystok, E. & Martin, M. M. Attention and inhibition in bilingual children: evidence from the dimensional change card sort task. Dev. Sci. 7 , 325–339 (2004).

Martin-Rhee, M. M. & Bialystok, E. The development of two types of inhibitory control in monolingual and bilingual children. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 11 , 81–93 (2008).

Prior, A. & MacWhinney, B. A bilingual advantage in task switching. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 13 , 253–262 (2010).

Hernández, M., Martin, C. D., Barceló, F. & Costa, A. Where is the bilingual advantage in task-switching? J. Mem. Lang. 69 , 257–276 (2013).

Stroop, J. R. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J. Exp. Psychol. 18 , 643–662 (1935).

Kovacs, A. M. & Mehler, J. Cognitive gains in 7-month-old bilingual infants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106 , 6556–6560 (2009).

Hilchey, M. D. & Klein, R. M. Are there bilingual advantages on nonlinguistic interference tasks? Implications for the plasticity of executive control processes. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 18 , 625–658 (2011).

Paap, K. R. & Greenberg, Z. I. There is no coherent evidence for a bilingual advantage in executive processing. Cogn. Psychol. 66 , 232–258 (2013).

Kousaie, S. & Phillips, N. A. Conflict monitoring and resolution: are two languages better than one? Evidence from reaction time and event-related brain potentials. Brain Res. 1446 , 71–90 (2012).

Dunabeitia, J. A. et al. The inhibitory advantage in bilingual children revisited. Exp. Psychol. http://dx.doi.org/10.1027/1618-3169/a000243 (2013).

Calabria, M., Hernandez, M., Branzi, F. M. & Costa, A. Qualitative differences between bilingual language control and executive control: evidence from task-switching. Front. Psychol. 2 , 399 (2012).

Prior, A. & Gollan, T. H. Good language-switchers are good task-switchers: evidence from Spanish–English and Mandarin–English bilinguals. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 17 , 682–691 (2011).

Brito, N. & Barr, R. Influence of bilingualism on memory generalization during infancy. Dev. Sci. 15 , 812–816 (2012).

Garbin, G. et al. Bridging language and attention: brain basis of the impact of bilingualism on cognitive control. Neuroimage 53 , 1272–1278 (2010).

Abutalebi, J. et al. Bilingualism tunes the anterior cingulate cortex for conflict monitoring. Cereb. Cortex 22 , 2076–2086 (2012).

Rodriguez-Pujadas, A. et al. Bilinguals use language-control brain areas more than monolinguals to perform non-linguistic switching tasks. PLoS ONE 8 , e73028 (2013).

Kave, G., Eyal, N., Shorek, A. & Cohen-Mansfield, J. Multilingualism and cognitive state in the oldest old. Psychol. Aging 23 , 70–78 (2008).

Gold, B. T., Kim, C., Johnson, N. F., Kryscio, R. J. & Smith, C. D. Lifelong bilingualism maintains neural efficiency for cognitive control in aging. J. Neurosci. 33 , 387–396 (2013).

Bialystok, E., Craik, F. I. M. & Freedman, M. Bilingualism as a protection against the onset of symptoms of dementia. Neuropsychologia 45 , 459–464 (2007).

Craik, F. I. M., Bialystok, E. & Freedman, M. Delaying the onset of Alzheimer disease: bilingualism as a form of cognitive reserve. Neurology 75 , 1726–1729 (2010).

Schweizer, T. A., Ware, J., Fischer, C. E., Craik, F. I. M. & Bialystok, E. Bilingualism as a contributor to cognitive reserve: evidence from brain atrophy in Alzheimer's disease. Cortex 48 , 991–996 (2012).

Chertkow, H. et al. Multilingualism (but not always bilingualism) delays the onset of Alzheimer disease: evidence from a bilingual community. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 24 , 118–125 (2010).

Crane, P. K. et al. Use of spoken and written Japanese did not protect Japanese-American men from cognitive decline in late life. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 65 , 654–666 (2010).

Gollan, T. H., Salmon, D. P., Montoya, R. I. & Galasko, D. R. Degree of bilingualism predicts age of diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease in low-education but not in highly educated Hispanics. Neuropsychologia 49 , 3826–3830 (2011).

Sanders, A. E., Hall, C. B., Katz, M. J. & Lipton, R. B. Non-native language use and risk of incident dementia in the elderly. J. Alzheimers Dis. 29 , 99–108 (2012).

Schmid, M. S. in Language Attrition. Theoretical Perspectives (eds Köpke, B., Schmid, M. S., Keijzer, M. & Dostert, S.) 135–153 (John Benjamins, 2007).

Book Google Scholar

Dewaele, J. M. in First Language Attrition: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Methodological Issues (eds Schmid, M. S., Köpke, B., Keijzer, M. & Weilemar, L.) 81–104 (John Benjamins, 2004).

Schmid, M. S. & Dusseldorp, E. Quantitative analyses in a multivariate study of language attrition: the impact of extralinguistic factors. Second Lang. Res. 26 , 125–160 (2010).

Schmid, M. S. Language Attrition (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2011).

Leroy, F. et al. Early maturation of the linguistic dorsal pathway in human infants. J. Neurosci. 31 , 1500–1506 (2011).

Mahmoudzadeh, M. et al. Syllabic discrimination in premature human infants prior to complete formation of cortical layers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110 , 4846–4851 (2013).

Bhattacharjee, Y. Why bilinguals are smarter. The New York Times SR12 (18 Mar 2012).

Wiese, A. & Garcia, E. The Bilingual Education Act: language minority students and US Federal education policy. Int. J. Bilingual Educ. Biling. 4 , 229–248 (2010).

Li, P. Computational modeling of bilingualism: how can models tell us more about the bilingual mind? Biling. Lang. Cogn. 16 , 241–245 (2013).

Dijkstra, T. & van Heuven, W. J. B. Modeling bilingual word recognition: past, present and future. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 5 , 219–224 (2002).

Diaz, B., Baus, C., Escera, C., Costa, A. & Sebastian-Galles, N. Brain potentials to native phoneme discrimination reveal the origin of individual differences in learning the sounds of a second language. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105 , 16083–16088 (2008).

Ventura-Campos, N. et al. Spontaneous brain activity predicts learning ability of foreign sounds. J. Neurosci. 33 , 9295–9305 (2013).

Tversky, A. & Kahneman, D. K. Belief in the law of small numbers. Psychol. Bull. 76 , 105–110 (1971).

Button, K. S. et al. Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nature Rev. Neurosci. 14 , 365–376 (2013).

Chiswick, B. R. Are immigrants favorably self-selected? Am. Econ. Rev. 89 , 181–185 (1999).

Hartsuiker, R. J., Pickering, M. J. & Veltkamp, E. Is syntax separate or shared between languages? Cross-linguistic syntactic priming in Spanish–English bilinguals. Psychol. Sci. 15 , 409–414 (2004).

Dijkstra, A. & Van Heuven, W. J. B. in Localist Connectionist Approaches to Human Cognition (eds Grainger, J. & Jacobs, A. M.) 189–225 (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1998).

Kroll, J. F., Bobb, S. C. & Wodniecka, Z. Language selectivity is the exception, not the rule: arguments against a fixed locus of language selection in bilingual speech. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 9 , 119–135 (2006).

Klein, D., Zatorre, R. J., Milner, B., Meyer, E. & Evans, A. C. Left putaminal activation when speaking a second language: evidence from PET. Neuroreport 5 , 2295–2297 (1994).

Chee, M. W. Dissociating language and word meaning in the bilingual brain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 10 , 527–529 (2006).

Chee, M. W., Soon, C. S. & Lee, H. L. Common and segregated neuronal networks for different languages revealed using functional magnetic resonance adaptation. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 15 , 85–97 (2003).

Perani, D. et al. The bilingual brain. Proficiency and age of acquisition of the second language. Brain 121 , 1841–1852 (1998).

Green, D. W. in The Interface between Syntax and the Lexicon in Second Language Acquisition (eds van Hout, R., Hulk, A., Kuiken, F. & Towell, R.) 197–217 (John Benjamins, 2003).

Kotz, S. A. A critical review of ERP and fMRI evidence on L2 syntactic processing. Brain Lang. 109 , 68–74 (2009).

Willms, J. L. et al. Language-invariant verb processing regions in Spanish–English bilinguals. Neuroimage 57 , 251–261 (2011).

Golestani, N. et al. Syntax production in bilinguals. Neuropsychologia 44 , 1029–1040 (2006).

Luk, G., Green, D. W., Abutalebi, J. & Grady, C. Cognitive control for language switching in bilinguals: a quantitative meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Lang. Cogn. Process. 27 , 1479–1488 (2012).

Hensch, T. K. Critical period plasticity in local cortical circuits. Nature Rev. Neurosci. 6 , 877–888 (2005).

Epstein, S., Flynn, S. & Martohardjono, G. Second language acquisition: theoretical and experimental issues in contemporary research. Behav. Brain Sci. 19 , 677–714 (1996).

Li, P. Lexical organization and competition in first and second languages: computational and neural mechanisms. Cogn. Sci. 33 , 629–664 (2009).

Werker, J. & Tees, R. Speech perception as a window for understanding plasticity and commitment in language systems of the brain. Dev. Psychobiol. 46 , 233–251 (2005).

Juffs, A. Second language acquisition. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 2 , 277–286 (2011).

Hu, W. Parents take language class into their own hands. The New York Times [online] , (2006).

Hickok, G. & Poeppel, D. The cortical organization of speech processing. Nature Rev. Neurosci. 8 , 393–402 (2007).

Huttenlocher, P. R. & Dabholkar, A. S. Regional differences in synaptogenesis in human cerebral cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 387 , 167–178 (1997).

Huttenlocher, P. R. Dendritic and synaptic development in human cerebral cortex: time course and critical periods. J. Dev. Neuropsychol. 16 , 347–349 (1999).

Pujol, J. et al. Myelination of language-related areas in the developing brain. Neurology 66 , 339–343 (2006).

Garcia-Sierra, A. et al. Bilingual language learning: an ERP study relating early brain responses to speech, language input, and later word production. J. Phon. 39 , 546–557 (2011).

Bartoletti, A., Medini, P., Berardi, N. & Maffei, L. Environmental enrichment prevents effects of dark-rearing in the rat visual cortex. Nature Neurosci. 7 , 215–216 (2004).

Pitres, A. Étude sur l'aphasie chez les polyglottes. Rev. Méd. 15 , 873–899 (in French) (1895).

Pearce, J. M. S. A note on aphasia in bilingual patients: Pitres' and Ribot's laws. Eur. Neurol. 54 , 127–131 (2005).

Paradis, M. in Handbook of Neuropsychology (ed. Berndt, R. S.) 69–91 (Elsevier Science, 2001).

Abutalebi, J., Rosa, P. A. D., Tettamanti, M., Green, D. W. & Cappa, S. F. Bilingual aphasia and language control: a follow-up fMRI and intrinsic connectivity study. Brain Lang. 109 , 141–156 (2009).

Green, D. W. & Abutalebi, J. Understanding the link between bilingual aphasia and language control. J. Neurolinguist. 21 , 558–576 (2008).

Faroqi-Shah, Y., Frymark, T., Mullen, R. & Wang, B. Effect of treatment for bilingual individuals with aphasia: a systematic review of the evidence. J. Neurolinguist. 23 , 319–341 (2010).

Green, D. W. in Handbook of Bilingualism: Psycholinguistic Approaches (eds Kroll, J. F. & de Groot, A. M. B.) 516–530 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2005).

Kiran, S., Grasemann, U., Sandberg, C. & Miikkulainen, R. A computational account of bilingual aphasia rehabilitation. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 16 , 325–342 (2013).

Costa, A. et al. On the parallel deterioration of lexico-semantic processes in the bilinguals' two languages: evidence from Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychologia 50 , 740–753 (2012).

Gollan, T. H., Salmon, D. P., Montoya, R. I. & da Pena, E. Accessibility of the nondominant language in picture naming: a counterintuitive effect of dementia on bilingual language production. Neuropsychologia 48 , 1356–1366 (2010).

Zanini, S. et al. Greater syntactic impairments in native language in bilingual Parkinsonian patients. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 75 , 1678–1681 (2004).

Zanini, S., Tavano, A. & Fabbro, F. Spontaneous language production in bilingual Parkinson's disease patients: evidence of greater phonological, morphological and syntactic impairments in native language. Brain Lang. 113 , 84–89 (2010).

de Souza, L. C., Lehericy, S., Dubois, B., Stella, F. & Sarazin, M. Neuroimaging in dementias. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 25 , 473–479 (2012).

Ferreira, L. K., Diniz, B. S., Forlenza, O. V., Busatto, G. F. & Zanetti, M. V. Neurostructural predictors of Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis of VBM studies. Neurobiol. Aging 32 , 1733–1741 (2011).

Pavese, N. PET studies in Parkinson's disease motor and cognitive dysfunction. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 18 , S96–S99 (2012).

Ray, N. J. & Strafella, A. P. The neurobiology and neural circuitry of cognitive changes in Parkinson's disease revealed by functional neuroimaging. Mov. Disord. 27 , 1484–1492 (2012).

Wang, X., Wang, Y., Jiang, T., Wang, Y. & Wu, C. Direct evidence of the left caudate's role in bilingual control: an intra-operative electrical stimulation study. Neurocase 19 , 462–469 (2012).

Dehaene-Lambertz, G. & Houston, D. Faster orientation latencies toward native language in two-month old infants. Lang. Speech 41 , 21–43 (1998).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank J. Abutalebi, D. Green, M. Burgaleta, P. Li, J. Corey, Y. Gilichinskaya and several members of the Center for Brain and Cognition at Pompeu Fabra University, Spain, for their comments on the manuscript. The authors are supported by grants from the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013): ERG grant agreement number 323961; Cooperation grant agreement number 613465 - AThEME), the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (PSI2011-23033; PSI2012-34071; Consolider-Ingenio2010-CDS-2007-00012) and the Catalan Government (SGR 2009–1521). N.S.G. received the prize ''ICREA Acadèmia'' for excellence in research, funded by the Generalitat de Catalunya.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Technology, Center for Brain and Cognition, Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona, 08018, Spain

Albert Costa & Núria Sebastián-Gallés

ICREA (Institució Catalana de Recerca I Estudis Avançats), Passeig Lluís Companys, 23,

Albert Costa

Barcelona, 08010, Spain

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Albert Costa .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

PowerPoint slides

Powerpoint slide for fig. 1, rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Costa, A., Sebastián-Gallés, N. How does the bilingual experience sculpt the brain?. Nat Rev Neurosci 15 , 336–345 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3709

Download citation

Published : 17 April 2014

Issue Date : May 2014

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3709

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

- Olga Kepinska

- Jocelyn Caballero

- Fumiko Hoeft

Scientific Reports (2023)

Parents’ Willingness to Pay for Bilingualism: Evidence from Spain

- Ainhoa Vega-Bayo

- Petr Mariel

Journal of Family and Economic Issues (2023)

An investigation across 45 languages and 12 language families reveals a universal language network

- Saima Malik-Moraleda

- Dima Ayyash

- Evelina Fedorenko

Nature Neuroscience (2022)

The transferability of handwriting skills: from the Cyrillic to the Latin alphabet

- Thibault Asselborn

- Anara Sandygulova

npj Science of Learning (2021)

Outgroup faces hamper word recognition

- Simone Sulpizio

- Eduardo Navarrete

Psychological Research (2020)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

EDITORIAL article

Editorial: new approaches to how bilingualism shapes cognition and the brain across the lifespan: beyond the false dichotomy of advantage versus no advantage.

A correction has been applied to this article in:

Corrigendum: Editorial: New approaches to how bilingualism shapes cognition and the brain across the lifespan: beyond the false dichotomy of advantage versus no advantage

- Read correction

- 1 The MARCS Institute for Brain, Behaviour and Development, Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, Australia

- 2 School of Psychology and Clinical Language Sciences, University of Reading, Reading, United Kingdom

- 3 Centro de Investigación Nebrija en Cognición, Universidad Nebrija, Madrid, Spain

- 4 Department of Speech-Language-Hearing Sciences, Hofstra University, Hempstead, NY, United States

Editorial on the Research Topic New approaches to how bilingualism shapes cognition and the brain across the lifespan: Beyond the false dichotomy of advantage versus no advantage

For much of the 20 th century, bilingualism was thought to result in cognitive disadvantages. In recent decades, however, research findings have suggested that experience with multiple languages may yield cognitive benefits and even counteract age-related cognitive decline, possibly delaying the manifestation of symptoms of dementia. Subsequently, conflicting evidence has emerged, and this has led to questions regarding the robustness and generalizability of these claims. A heated debate has raged for more than a decade ( Antoniou, 2019 ), with certain research groups consistently finding support for a bilingual advantage, and others consistently finding none. The field has reached a stalemate, which has stifled research opportunities and the advancement of knowledge. In organizing the present Research Topic, we sought contributions describing new approaches needed to advance our field. These contributions help move the field beyond the traditional framing of bilingualism as a binary variable and toward approaches that capture the dynamic nature of effects relating to bilingualism and cognition.

New conceptualizations

One way of moving beyond traditional framing is to explore new conceptualizations of bilingualism, itself, and the relationship between bilingualism and cognition.

In her opinion piece, Bialystok likens the bilingual advantage debate to COVID-19 debates concerning which public health measures and mandates should (or should not) be implemented. She quotes virologist, Ian Mackay, who applied Reason's (1990) Swiss cheese model to COVID-19 risk mitigation by proposing that individual measures are imperfect (containing holes like a slice of Swiss cheese) and that only a multi-layered approach has sufficient redundancy built in to successfully offer protection from the risks at hand (similar to stacking slices of Swiss cheese so that the holes become covered). By adopting this metaphor, Bialystok is proposing that our field should move beyond simple conceptions concerning the relationship between bilingualism and cognition. Through this lens, bilingualism offers a layer of cognitive protection, but one which is porous rather than absolute. Bialystok's framing serves as a reminder that we, as a field, need to move beyond the “all or nothing” framing that has featured throughout the bilingual advantage debate over the past two decades.

The contribution from Sanches de Oliveira and Bullock Oliveira argues that the question of whether there are bilingual advantages in cognition is ill-formed and unanswerable. Bilingualism is a problematic category, according to the authors, because bilingualism and monolingualism are on a continuum rather than discrete, and languages and dialects are likewise on a continuum; what is more, a person's language proficiency is variable and skill- and context-specific, and full proficiency in any language is not even attainable, as one cannot have full proficiency in the vocabulary jargon of every possible activity. Cognition (and by extension cognitive advantages) are similarly problematic concepts, Sanches de Oliveira and Bullock Oliveira claim, partly because such concepts fail to account for the context-specific and thus variable nature of cognitive functioning.

Wagner et al. explore the questions of what it means to be bilingual, and what people consider to be a language. In doing so, they address the concern that many studies rely on participants' judgments of whether they themselves belong in the bilingual group or monolingual group. This self-assignment can be problematic because participants might vary considerably in what they believe constitutes a bilingual and even a language. In a survey of 528 participants, Wagner et al. observe a range of responses from participants when judging whether fictional speakers qualified as bilingual and fictional linguistic systems qualified as a language. Participants' definitions of bilingualism depended on several factors, including continued use of a language after immigrating and the presence of a writing system. Participants' definitions of a language depended on the presence of a writing system, similarity to other languages, and geographic breadth. Wagner et al. conclude that the variable and potentially inaccurate conceptions of bilingualism and language could contribute to some of the variable findings in the literature.

Chung-Fat-Yim et al. discuss the nuanced nature of attention, dividing this multi-faceted concept into sustained attention, selective attention, alternating attention, divided attention, and disengagement of attention. For each component of attention, the authors review relevant models from the psychology and neuroscience literature, as well as empirical research that has examined bilingualism's potential positive effects.

Voits et al. discuss the commonalities and complementarities between the bilingualism and cognitive aging literatures. Bilingualism tends to be reduced to a dichotomous trait, which misrepresents its status as a complex experience; other times it is overlooked as a contributory factor all together. These authors discuss why bilingualism is not recognized as a contributor to cognitive reserve. They also helpfully suggest how bilingualism can be better integrated into aging research in future work. A model of aging is needed that encompasses the contributions of lifestyle factors, one of which is likely to be bilingual experience.

New measures

Another way of moving beyond the stalemate debate surrounding bilingual benefits is to create new tasks, measures, and analyses.

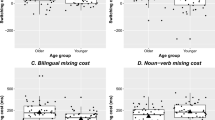

Wu and Struys examine the influence of language dominance on bilingual word recognition. Uyghur-Chinese bilinguals completed lexical decision tasks administered in the L1 and L2, as well as a flanker task. Although bilinguals differed in their language dominance, all reported that they preferred reading in Chinese, their L2. Consequently, better performance was observed in their L2 than L1 on the lexical decision tasks. Further, those who had acquired their L2 earlier and had higher across-modality dominance in the L2 tended to recognize L2 words faster. The findings suggest that language dominance may be operationalized as a continuous or a categorical variable, and in doing so may exhibit effects not only for lexical recognition but also indirectly impacting domain-general contributions to recognition.

van den Berg et al. also investigate how individual bilingual experiences affect executive control in different contexts of language use. They tested bilingual university students, for whom they calculated a measure of language entropy for different contexts (university and non-university) by using a language background questionnaire. These language entropy measures were used as continuous predictors of the participants' performance in a color-shape switching task. Apart from collecting Reaction Times, pupil size was also measured as an objective index of set shifting abilities that are required for this task. The authors report that, while typical switching costs in RTs were not affected by entropy in either context, entropy did predict a switching cost in a non-university context when pupil dilation was studied. van den Berg et al. conclude that social diversity in bilinguals' experiences may indeed be linked to their executive control abilities, but this may depend on the exact social context and may be detectable in measures that are more sensitive than RT, such as pupil size.

Similarly, Freeman et al. focus on how quantified individual bilingual experiences affect performance in a non-linguistic task tapping executive control. Specifically, a sample of 146 Spanish-English heritage bilinguals were tested in a Stroop arrows task, from which the Stroop, facilitation and inhibition effects were calculated. Measures of individual experiences were used as predictors of these effects, including participants' sociolinguistic context (categorical), a composite continuous variable indexing L2 proficiency and exposure, as well as L2 age of acquisition, L2 proficiency and a measure of non-verbal cognitive reasoning, all continuous factors. The authors report a rich pattern of findings which converged in that increased bilingual experiences and cognitive skills led to increased abilities of focusing on relevant stimuli while ignoring irrelevant ones. These findings were also modulated by the sociolinguistic environment of the individuals, suggesting that any effects of bilingualism on cognition should be viewed in relation to the contexts that bilinguals find themselves in.

Grant et al.'s contribution follows on the same path of avoiding a binary monolingual-bilingual comparison and employing a seldom-used but meaningful and sensitive neural measure. Specifically, participants listened to speech-in-noise in their L1 and L2; the continuous independent variable of L2 age of acquisition and the dependent variable of EEG-measured alpha power were used. Findings indicate an increased alpha power when listening in the L2 and when the participant had an older L2 age of acquisition.

In a similar vein, Marin-Marin et al. turn their attention to the effects of bilingualism on brain structure, by using a measure of bilingual experiences as a predictor of regional gray matter volume in a group of Catalan-Spanish bilinguals that were immersed in a bilingual environment. They report non-linear volumetric fluctuations in a series of cortical and subcortical regions that have been linked to speech processing and language control. The authors argue that their pattern of results are corroborative of theoretical suggestions for dynamic, non-linear effects of bilingualism on the adult brain.

Finally, Dash et al. attempt to advance modeling bilingualism as a continuous variable. They show that a multifactorial approach to different dimensions of bilingual study may lead to a better understanding of the role of bilingualism on cognitive performance. Rather than reducing variability or treating it as problematic, these authors argue that variability needs to be embraced in bilingual profiles if we are to generalize the results of individual studies to the wider literature.

Future directions

Taken together, the articles within this Research Topic provide suggestions concerning how our field might move beyond the entrenched positions that have characterized the bilingual advantage debate for more than a decade. We are excited by the ambitious and rigorous studies that will emerge in coming years to advance understanding of how experience with multiple languages interacts with other variables to affect cognition, the structure and function of the brain, and aging. There remains a need for detailed theoretical models that generate testable predictions in order for us to understand what types of bilingual experiences are more (or less) likely to show plasticity effects in a given domain. To achieve this, it is necessary to pay attention to how bilingualism is conceptualized and to methodological nuances in experimental designs, such as differences in tasks used and in the components of cognition they measure. By focusing on these aspects, we believe that this Research Topic offers a window into how knowledge can advance within our field, specifically concerning how bilingualism affects cognition and the brain.

Author contributions

MA, CP, and SRS contributed equally to the writing of this editorial article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was funded by the Australian Research Council, Grant Number: DP190103067.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Antoniou, M. (2019). The advantages of bilingualism debate. Annu. Rev. Linguist. 5, 395–415. doi: 10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011718-011820

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Reason, J. (1990). Human Error . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Google Scholar

Keywords: bilingualism, cognition, brain, advantage, new approaches

Citation: Antoniou M, Pliatsikas C and Schroeder SR (2023) Editorial: New approaches to how bilingualism shapes cognition and the brain across the lifespan: Beyond the false dichotomy of advantage versus no advantage. Front. Psychol. 14:1149062. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1149062

Received: 20 January 2023; Accepted: 25 January 2023; Published: 07 February 2023.

Edited and reviewed by: Sara Palermo , University of Turin, Italy

Copyright © 2023 Antoniou, Pliatsikas and Schroeder. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

† These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Cognitive Consequences of Bilingualism and Multilingualism: Cross-Linguistic Influences

- Published: 12 April 2021

- Volume 50 , pages 313–316, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Michael C. W. Yip ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9790-334X 1

2100 Accesses

2 Citations

Explore all metrics

Bilingualism and multilingualism are common in almost all communities worldwide today. Research studies on the psycholinguistics of bilingualism and multilingualism in East Asia region has developed tremendously in the past 20 years. Along with the new methodologies, innovative approaches, and the development of those state-of-the-art technologies (Altarriba and Heredia (eds) in An introduction to bilingualism: principles and processes, Routledge, 2018), a lot of new research findings on this line of research have been reported.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Bilingualism and Multilingualism

Research Perspectives on Bilingualism and Bilingual Education

Altarriba, J., & Heredia, R. R. (Eds.). (2018). An introduction to bilingualism: Principles and processes . Routledge.

Google Scholar

Bhatia, T. K., & Ritchie, W. C. (Eds.). (2014). The handbook of bilingualism and multilingualism . Wiley.

Chomsky, N. (1969). Aspects of the theory of syntax . MIT Press.

Clyne, M. (1967). Trasferring and triggering . Nijhoff.

Grosjean, F. (2010). Bilingual . Harvard University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Grosjean, F., & Byers-Heinlein, K. (2018). The listening bilingual: Speech perception, comprehension, and bilingualism . Wiley.

Grosjean, F., & Li, P. (2013). The psycholinguistics of bilingualism . Wiley.

Hernandez, A. E. (2013). The bilingual brain . Oxford University Press.

Marian, V., & Spivey, M. (2003). Competing activation in bilingual language processing: Within-and between-language competition. Bilingualism, 6 (2), 97–115.

Article Google Scholar

Shaffer, D. (1978). The place of code-switching in linguistic contacts. In M. Paradis (Ed.), Aspects of bilingualism. (pp. 265–274). Hornbeam Press Inc.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, The Education University of Hong Kong, 10 Lo Ping Road, Tai Po, New Territories, Hong Kong SAR, China

Michael C. W. Yip

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

I am the sole author of this article.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Michael C. W. Yip .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

I am one of the associate editors of this Journal.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Yip, M.C.W. Cognitive Consequences of Bilingualism and Multilingualism: Cross-Linguistic Influences. J Psycholinguist Res 50 , 313–316 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-021-09779-y

Download citation

Accepted : 30 March 2021

Published : 12 April 2021

Issue Date : April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-021-09779-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Bilingualism

- Multilingualism

- Psycholinguistics

- Cross-linguistic effects

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Applied Linguistics

- Biology of Language

- Cognitive Science

- Computational Linguistics

- Historical Linguistics

- History of Linguistics

- Language Families/Areas/Contact

- Linguistic Theories

- Neurolinguistics

- Phonetics/Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sign Languages

- Sociolinguistics

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Bilingualism and multilingualism from a socio-psychological perspective.

- Tej K. Bhatia Tej K. Bhatia Department of Linguistics, Syracuse University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.82

- Published online: 28 June 2017

Bilingualism/multilingualism is a natural phenomenon worldwide. Unwittingly, however, monolingualism has been used as a standard to characterize and define bilingualism/multilingualism in linguistic research. Such a conception led to a “fractional,” “irregular,” and “distorted” view of bilingualism, which is becoming rapidly outmoded in the light of multipronged, rapidly growing interdisciplinary research. This article presents a complex and holistic view of bilinguals and multilinguals on conceptual, theoretical, and pragmatic/applied grounds. In that process, it attempts to explain why bilinguals are not a mere composite of two monolinguals. If bilinguals were a clone of two monolinguals, the study of bilingualism would not merit any substantive consideration in order to come to grips with bilingualism; all one would have to do is focus on the study of a monolingual person. Interestingly, even the two bilinguals are not clones of each other, let alone bilinguals as a set of two monolinguals. This paper examines the multiple worlds of bilinguals in terms of their social life and social interaction. The intricate problem of defining and describing bilinguals is addressed; their process and end result of becoming bilinguals is explored alongside their verbal interactions and language organization in the brain. The role of social and political bilingualism is also explored as it interacts with individual bilingualism and global bilingualism (e.g., the issue of language endangerment and language death).

Other central concepts such as individuals’ bilingual language attitudes, language choices, and consequences are addressed, which set bilinguals apart from monolinguals. Language acquisition is as much an innate, biological, as social phenomenon; these two complementary dimensions receive consideration in this article along with the educational issues of school performance by bilinguals. Is bilingualism a blessing or a curse? The linguistic and cognitive consequences of individual, societal, and political bilingualism are examined.

- defining bilinguals

- conceptual view of bilingualism

- becoming bilingual

- social networks

- language organization of bilinguals

- the bilingual mind

- bilingual language choices

- language mixing

- code-mixing/switching

- bilingual identities

- consequences of bilingualism

- bilingual creativity

- and political bilingualism

1. Understanding Multilingualism in Context

In a world in which people are increasingly mobile and ethnically self-aware, living with not just a single but multiple identities, questions concerning bilingualism and multilingualism take on increasing importance from both scholarly and pragmatic points of view. Over the last two decades in which linguistic/ethnic communities that had previously been politically submerged, persecuted, and geographically isolated, have asserted themselves and provided scholars with new opportunities to study the phenomena of individual and societal bilingualism and multilingualism that had previously been practically closed to them. Advances in social media and technology (e.g., iPhones and Big Data Capabilities) have rendered new tools to study bilingualism in a more naturalistic setting. At the same time, these developments have posed new practical challenges in such areas as language acquisition, language identities, language attitudes, language education, language endangerment and loss, and language rights.

The investigation of bi- and multilingualism is a broad and complex field. Unless otherwise relevant on substantive grounds, the term “bilingualism” in this article is used as an all-inclusive term to embody both bilingualism and multilingualism.

2. Bilingualism as a Natural Global Phenomenon: Becoming Bilingual

Bilingualism is not entirely a recent development; for instance, it constituted a grassroots phenomenon in India and Africa since the pre-Christian era. Contrary to a widespread perception, particularly in some primarily monolingual countries—for instance, Japan or China—or native English-speaking countries, such as the United States, bilingualism or even multilingualism is not a rare or exceptional phenomenon in the modern world; it was and it is, in fact, more widespread and natural than monolingualism. The Ethnologue in the 16th edition ( 2009 , http://www.ethnologue.com/show_country.asp?name=lb ) estimates more than seven thousand languages (7,358) while the U.S. Department of States recognizes only 194 bilingual countries in the world. There are approximately 239 and 2,269 languages identified in Europe and Asia, respectively. According to Ethnologue , 94% of the world’s population employs approximately 5% of its language resources. Furthermore, many languages such as Hindi, Chinese, Arabic, Bengali, Punjabi, Spanish, and Portuguese are spoken in many countries around the globe. Such a linguistic situation necessitates people to live with bilingualism and/or multilingualism. For an in-depth analysis of global bilingualism, see Bhatia and Ritchie ( 2013 ).

3. Describing Bilingualism

Unlike monolingualism, childhood bilingualism is not the only source and stage of acquiring two or more languages. Bilingualism is a lifelong process involving a host of factors (e.g., marriage, immigration, and education), different processes (e.g., input conditions, input types, input modalities and age), and yielding differential end results in terms of differential stages of fossilization and learning curve (U-shape or nonlinear curve during their grammar and interactional development). For this reason, it does not come as a surprise that defining, describing, and categorizing a bilingual is not as simplistic as defining a monolingual person. In addition to individual bilingualism, social and political bilingualism adds yet other dimensions to understanding bilingualism. Naturally then, there is no universally agreed upon definition of a bilingual person.

Bilingual individuals are subjected to a wide variety of labels, scales, and dichotomies, which constitute a basis of debates over what is bilingualism and who is a bilingual. Before shedding light on the complexity of “individual” bilingualism, one should bear in mind that the notion of individual bilingualism is not devoid of social bilingualism, or an absence of a shared social or group grammar. The term “individual” bilingualism by no means refers to idiosyncratic aspects of bilinguals, which is outside the scope of this work.

Relying on a Chomskyan research paradigm, bilingualism is approached from the theoretical distinction of competence vs. performance (actual use). Equal competency and fluency in both languages—an absolute clone of two monolinguals without a trace of accent from either language—is one view of a bilingual person. This view can be characterized as the “maximal” view. Bloomfield’s definition of a bilingual with “a native-like control of two languages” attempts to embody the “maximal” viewpoint (Bloomfield, 1933 ). Other terms used to describe such individuals are “ambilinguals” or “true bilinguals.” Such bilinguals are rare, or what Valdes terms, “mythical bilingual” (Valdes, 2001 ). In contrast to maximal view, a “minimal” view contends that practically every one is a bilingual. “That is no one in the world (no adult, anyway) which does not know at least a few words in languages other than the maternal variety” (Edwards, 2004/2006 ). Diebold’s notion of “Incipient bilingualism”—that is, exposure to two languages—belongs to the minimal view of bilingualism (Diebold, 1964 ). While central to the minimalist viewpoint is the onset point of the process of becoming a bilingual, the main focus of the maximalist view is the end result, or termination point, of language acquisition. In other words, the issue of degree and the end state of second language acquisition is at the heart of defining the concept of bilingualism.

Other researchers such as Mackey, Weinreich, and Haugen define bilingualism to capture language use of bilinguals’ verbal behavior. For Haugen, bilingualism begins when the speakers of one language produce complete meaningful utterances in the second language (Haugen, 1953 ; Mackey, 2000 ; Weinrich, 1953 ). Mackey, on the other hand, defines bilingualism as an “alternate use of two or more languages” (Mackey, 2000 ). Observe that the main objective of the two definitions is to focus on language use rather the degree of language proficiency or equal competency in two languages.

The other notable types of bilingualism identified are as follows: Primary/Natural bilingualism in which bilingualism is acquired in a natural setting without any formal training; Balanced bilingualism that develops with minimal interference from both languages; Receptive or Passive bilingualism wherein there is understanding of written and/or spoken proficiency in second language but an inability to speak it; Productive bilingualism then entails an ability to understand and speak a second language; Semilingualism, or an inability to express in either language; and Bicultural bilingualism vs. Monocultural bilingualism. The other types of bilingualism, such as Simultaneous vs. Successive bilingualism (Wang, 2008 ), Additive vs. Subtractive bilingualism (Cummins, 2000 ), and Elite vs. Folk bilingualism (Skutnabb-Kangas, 1981 ), will be detailed later in this chapter. From this rich range of scales and dichotomies, it becomes readily self-evident that the complexity of bilingualism and severe limitation of the “fractional” view of bilingualism that bilinguals are two monolinguals in one brain. Each case of bilingualism is a product of different sets of circumstances and, as a result, no two bilinguals are the same. In other words, differences in the context of second language acquisition (natural, as in the case of children) and proficiency in spoken, written, reading, and listening skills in the second language, together with the consideration of culture, add further complexity to defining individual bilingualism.

3.1 Individual Bilingualism: A Profile

The profile of this author further highlights the problems and challenges of defining and describing a bilingual or multilingual person. The author, as an immigrant child growing up in India, acquired two languages by birth: Saraiki—also called Multani and Lahanda, spoken primarily in Pakistan—and Punjabi, which is spoken both in India and Pakistan. Growing up in the Hindi-speaking area, he learned the third language Hindi-Urdu primarily in schools; and his fourth language, English, primarily after puberty during his higher education in India and the United States. He cannot write or read in Saraiki but can read Punjabi in Gurmukhi script, and he cannot write with the same proficiency. He has native proficiency in speaking, listening, reading, and writing. A close analysis of his bilingualism reveals that no single label or category accounts for his multifaceted bilingualism/multilingualism. Interestingly, his self-assessment finds him linguistically least secured in his two languages, which he acquired at birth. Is he a semilingual without a mother tongue? No matter how challenging it is to come to grips with bilingualism and, consequently, develop a “holistic” view of bilingualism, it is clear that a bilingual person demonstrates many complex attributes rarely seen in a monolingual person. See Edwards ( 2004/2006 ) and Wei ( 2013 ) for more details. Most important, multiple languages serve as a vehicle to mark multiple identities (e.g., religious, regional, national, ethnic, etc.).

3.2 Social Bilingualism

While social bilingualism embodies linguistic dimensions of individual bilingualism, a host of social, attitudinal, educational, and historical aspects of bilingualism primarily determine the nature of social bilingualism. Social bilingualism refers to the interrelationship between linguistic and non-linguistic factors such as social evaluation/value judgements of bilingualism, which determine the nature of language contact, language maintenance and shift, and bilingual education among others. For instance, in some societies, bilingualism is valued and receives positive evaluation and is, thus, encouraged while in other societies bilingualism is seen as a negative and divisive force and is, thus, suppressed or even banned in public and educational arenas. Compare the pattern of intergenerational bilingualism in India and the United states, where it is well-known that second or third-generation immigrants in the United States lose their ethnic languages and turn monolinguals in English (Fishman, Nahirny, Hofman, & Hayden, 1966 ). Conversely, Bengali or Punjabi immigrants living in Delhi, generation after generation, do not become monolinguals in Hindi, the dominant language of Delhi. Similarly, elite bilingualism vs. folk bilingualism has historically prevailed in Europe, Asia, and other continents and has gained a new dimension in the rapidly evolving globalized society. As aristocratic society patronized bilingualism with French or Latin in Europe, bilingualism served as a source of elitism in South Asia in different ages of Persian and English. Folk bilingualism is often the byproduct of social dominance and imposition of a dominant group. While elite bilingualism is viewed as an asset, folk bilingualism is seen as problematic both in social and educational arenas (Skutnabb-Kangas, 1981 ). One of the outcomes of a stable elite and folk bilingualism is diglossia (e.g., Arabic, German, Greek, and Tamil) where both High (elite) and Low (colloquial) varieties of a language—or two languages with High and Low social distinctions—coexist (e.g., French and English diglossia after the Norman conquest (Ferguson, 1959 ). Diasporic language varieties have been examined by Clyne and Kipp ( 1999 ) and Bhatia ( 2016 ). Works by Baker and Jones ( 1998 ) show how bilinguals belong to communities of variable types due to accommodation (Sachdev & Giles, 2004/2006 ), indexicality (Eckert & Rickford, 2001 ), social meaning of language attitudes (Giles & Watson, 2013 ; Sachdev & Bhatia, 2013 ), community of practice, and even imagined communities.

3.3 Political Bilingualism

Political bilingualism refers to the language policies of a country. Unlike individual bilingualism, categories such as monolingual, bilingual, and multilingual nations do not reflect the actual linguistic situation in a particular country (Edwards, 1995 , 2004/2006 ; Romaine, 1989/1995 ). Canada, for instance, is officially recognized as a bilingual country. This means that Canada promotes bilingualism as a language policy of the country as well as in Canadian society as a whole. By no means does it imply that most speakers in Canada are bilinguals. In fact, monolingual countries may reflect a high degree of bilingualism. Multilingual countries such as South Africa, Switzerland, Finland and Canada often use one of the two approaches—“Personality” and “Territorial”—to ensure bilingualism. The Personality principle aims to preserve individual rights (Extra & Gorter, 2008 ; Mackey, 1967 ) while the Territorial principle ensures bilingualism or multilingual within a particular area to a variable degree, as in the case of Belgium. In India, where 23 languages are officially recognized, the government’s language policies are very receptive to multilingualism. The “three-language formula” is the official language policy of the country (Annamalai, 2001 ). In addition to learning Hindi and English, the co-national languages, school children can learn a third language spoken within or outside their state.

4. The Bilingual Mind: Language Organization, Language Choices, and Verbal Behavior

Unlike monolinguals, a decision to speak multiple languages requires a complex unconscious process on the part of bilinguals. Since a monolingual’s choice is restricted to only one language, the decision to choose a language is relatively simple involving, at most, the choice of an informal style over a formal style or vice versa. However, the degree and the scale of language choice are much more complicated for bilinguals since they need to choose not only between different styles but also between different languages. It is a widely held belief, at least in some monolingual speech communities, that the process of language choice for bilinguals is a random one that can lead to a serious misunderstanding and a communication failure between monolinguals and bi- and multilingual communities (see pitfalls of a sting operation by a monolingual FBI agent (Ritchie & Bhatia, 2013 )). Such a misconception of bilingual verbal behavior is also responsible for communication misunderstandings about social motivations of bilinguals’ language choices by monolinguals; for example, the deliberate exclusion or sinister motives on the part of bilinguals when their language choice is different from a monolingual’s language. A number of my international students have reported that on several occasions monolingual English speakers feel compelled to remind them that they are in America and they should be using English, rather than say Chinese or Arabic, with countrymen/women.

Now let us examine some determinants of language choice by bilinguals. Consider the case of this author’s verbal behavior and linguistic choices that he normally makes while interacting with his family during a dinner table conversation in India. He shares two languages with his sisters-in-law (Punjabi and Hindi) and four languages with his brothers (Saraiki, Punjabi, Hindi, and English). While talking about family matters or other informal topics, he uses Punjabi with his sisters-in-law but Saraiki with his brothers. If the topic involves ethnicity, then the entire family switches to Punjabi. Matters of educational and political importance are expressed in English and Hindi, respectively. These are unmarked language choices, which the author makes unconsciously and effortlessly with constant language switching depending on participants, speech events, situations, or other factors. Such a behavior is largely in agreement with the sociolinguistic Model of Markedness, which attempts to explain the sociolinguistic motivation of code-switching by considering language choice as a means of communicating desired group membership, or perceived group memberships, and interpersonal relationships (Pavlenko, 2005 ).

Speaking Sariki with brothers and Punjabi with sister-in-laws represent unconscious and unmarked choices. Any shift to a marked choice is, of course, possible on theoretical grounds; however, it can take a serious toll in terms of social relationships. The use of Hindi or English during a general family dinner conversation (i.e., a “marked” choice) will necessarily signal social distancing and fractured relations.

Languages choice is not as simple as it seems at first from the above example of family conversation. In some cases, it involves a complex process of negotiation. Talking with a Punjabi-Hindi-English trilingual waiter in an Indian restaurant, the choice of ethnic language, Punjabi, by a customer such as this author may seem to be a natural choice at first. Often, it is not the case if the waiter refuses to match the language choice of the customer and replies in English. The failure to negotiate a language in such cases takes an interesting turn of language mismatching before a common language of verbal exchange is finally agreed upon; often, it turns out to be a neutral and prestige language: English. See Ritchie and Bhatia ( 2013 ) for further details. When the unmarked choice is not clear, speakers tend to use code-switching in an exploratory way to determine language choice and thus restore a social balance.

During a speech event, language choice is not always static either. If the topic of conversation shifts from a casual topic to a formal topic such as education, a more suitable choice in this domain would be English; subsequently, a naturally switch to English will take place. In other words, “complementarity” language domains or language-specific domain allocation represent the salient characteristics of bilingual language choice. The differential domain allocation manifests itself in the use of “public” vs. “private” language by bilinguals, which is central to bilingual verbal repertoire (Ritchie & Bhatia, 2013 ). Often the role of expressing emotions or one’s private world is best played by the bilingual’s mother tongue rather than by the second or prestige/distant language. Research on bilingualism, emotions, and autobiographical memory accounts of bilinguals shows that an account of emotional events is qualitatively and quantitatively different when narrated in one’s mother tongue than in a distant second language (Devaele, 2010 ; Pavlenko, 2005 ). While the content of an event can be narrated equally well in either language, the emotional experience/pain is best described in the first language of the speaker. Particularly, bilingual parents use their first language for terms of endearment for their children. Their first language serves as the best vehicle for denoting emotions toward their children than any other language in their verbal repertoire. Taboo topics, on the other hand, favor the second or a distant language.

Any attempt to characterize the bilingual mind must account for the following three natural aspects of bilingual verbal behavior: (1) Depending upon the communicative circumstances, bilinguals swing between the monolingual and bilingual language modes; (2) Bilinguals have an ability to keep two or more languages separate whenever needed; and (3) More interestingly, they can also carry out an integration of two or more languages within a speech event.

4.1 Bilingual Language Modes

Bilinguals are like a sliding switch who can move between one or more language states/modes as required for the production, comprehension, and processing of verbal messages in a most cost-effective and efficient way. If bilinguals are placed in a predominantly monolingual setting, they are likely to activate only one language; while in a bilingual environment, they can easily shift into a bilingual mode to a differential degree. The activation or deactivation process is not time consuming. In a bilingual environment, this process usually does not require bilinguals to take more than a couple of milliseconds to swing into a bilingual language mode and revert back to a monolingual mode with the same time efficiency. However, under unexpected circumstances (e.g., caught off-guard by a white Canadian speaking an African language in Canada) or under emotional trauma or cultural shock, the activation takes considerable time. In the longitudinal study of his daughter, Hildegard, reported that Hildegard, while in Germany, came to tears at one point when she could not activate her mother tongue, English (Leopard, 1939–1950 ). The failure to ensure natural conditions responsible for the activation of bilingual language mode is a common methodological shortcoming of bilingual language testing, see Grosjean ( 2004 / 2006 , 2010 ). An in-depth review of processing cost involved in the language activation-deactivation process can be found in Meuter ( 2005 ). Do bilinguals turn on their bilingual mode, even if only one language is needed to perform a task? Recent research employing an electrophysiological and experimental approach shows that both languages compete for selection even if only one language is needed to perform a task (Martin, Dering, Thomas, & Thierry, 2009 ; Hoshino & Thierry, 2010 ). For more recent works on parallel language activation and language competition in speech planning and speech production, see Blumenfeld and Marian ( 2013 ). In other words, the potential of activation and deactivation of language modes—both monolingual and bilingual mode—hold an important key to bilingual’s language use.

4.2 Bilingual Language Separation and Language Integration

In addition to language activation or deactivation control phenomena, the other two salient characteristics of bilingual verbal behavior are bilinguals’ balanced competence and capacity to separate the two linguistic systems and to integrate them within a sentence or a speech event. Language mixing is a far more complex cognitive ability than language separation. Yet, it is also very natural to bilinguals. Therefore, it is not surprising to observe the emergence of mixed systems such as Hinglish, Spanglish, Germlish, and so on, around the globe. Consider the following utterances:

Such a two-faceted phenomenon is termed as code-mixing (as in 1 and 2) and code-switching (as in 3). Code-mixing (CM) refers to the use of various linguistic units—words, phrases, clauses, and sentences—primarily from two participating grammatical systems within a sentence. While CM is intra-sentential, code-switching (CS) is an inter-sentential phenomenon. CM is constrained by grammatical principles and is motivated by socio-psychological factors. CS, on the other hand, is subject to discourse principles and is also motivated by socio-psychological factors.

Any unified treatment of the bilingual mind has to account for the language separation (i.e., CS) and language integration (CM) aspects of bilingual verbal competence, capacity, use, and creativity. In that process, it needs to address the following four key questions, which are central to an understanding the universal and scientific basis for the linguistic creativity of bilinguals.

Is language mixing a random or a systematic phenomenon?

What motivates bilinguals to mix and alternate two languages?

What is the social evaluation of this mixing and alternation?

What is the difference between code-mixing or code-switching and other related phenomena?

I. Language mixing as a systematic phenomenon

Earlier research from the 1950s–1970s concluded that CM is either a random or an unsystematic phenomenon. It was either without subject to formal syntactic constraints or is subject only to “irregular mixture” (Labov, 1971 ). Such a view of CM/CS is obsolete since late the 20th century . Recent research shows that CM/CS is subject to formal, functional, and attitudinal factors. Studies of formal factors in the occurrence of CM attempt to tap the unconscious knowledge of bilinguals about the internal structure of code-mixed sentences. Formal syntactic constraints on the grammar of CM, such as The Free Morpheme Constraint (Sankoff & Poplack, 1981 ); The Closed Class Constraint (Joshi, 1985 ), within the Generative Grammar framework; and The Government Constraint and the Functional Head Constraint within the non-lexicalist generative framework, demonstrate the complexity of uncovering universal constraints on CM; for details, see Bhatia and Ritchie ( 2009 ). Recently, the search for explanations of cross-linguistic generalizations about the phenomenon of CM, specifically in terms of independently justified principles of language structure and use, has taken two distinct forms. One approach is formulated in terms of the theory of linguistic competence within the framework of Chomsky’s Minimalist Program (MacSwan, 2009 ). The other approach—as best exemplified by the Matrix Language Frame (MLF) model (Myers-Scotton & Jake, 2001 ) is grounded in the theory of sentence production, particularly that of Levelt ( 1989 ). Herring and colleagues test the strengths and weaknesses of both a Minimalist Program approach and the MLF approach on explanatory grounds based on switches between determiner and their noun complements drawn from Spanish-English and Welsh-English data (Herring, Deuchar, Couto, & Quintanilla, 2010 ). Their work lends partial support to the two approaches.

II. Motivations for language mixing

While research on the universal grammar of CM attempts to unlock the mystery of the systematic nature of CM on universal grounds, it does not attempt to answer Question (II), namely, the “why” aspect of CM. The challenge for linguistic research in the new millennium is to separate grammatical constraints from those motivated by, or triggered by, socio-pragmatic factors or competence. Socio-pragmatic studies of CM reveal the following four factors, which trigger CM/CS: (1) the social roles and relationships of the participants (e.g., dual/multiple identities; social class); (2) situational factors (discourse topic and language domain allocation); (3) message-intrinsic consideration; (4) language attitudes, including social dominance and linguistic security. See Ritchie and Bhatia ( 2013 ) and Myers-Scotton ( 1998 ) for further details. The most commonly accepted rule is that language mixing signals either a change or a perceived change by speaker in the socio-psychological context of a speech event. In essence, CM/CS is motivated by the consideration of “optimization,” and it serves as an indispensable tool for meeting creative and innovative needs of bilinguals (Bhatia, 2011 ). A novel approach provides further insights into a discourse-functional motivation of CM, namely, coding of less predictable, high information-content meanings in one language and more predictable, lower information-content meanings in another language (Myslin & Levy, 2015 ).

III. Social evaluation of language mixing