- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

The Oxford Handbook of Quantitative Methods in Psychology, Vol. 1

Todd D. Little, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Research today demands the application of sophisticated and powerful research tools. Fulfilling this need, this two-volume text provides the tool box to deliver the valid and generalizable answers to today's complex research questions. The Oxford Handbook of Quantitative Methods in Psychology aims to be a source for learning and reviewing current best-practices in quantitative methods as practiced in the social, behavioral, and educational sciences. Comprising two volumes, this text covers a wealth of topics related to quantitative research methods. It begins with essential philosophical and ethical issues related to science and quantitative research. It then addresses core measurement topics before delving into the design of studies. Principal issues related to modern estimation and mathematical modeling are also detailed. Topics in the book then segway into the realm of statistical inference and modeling with articles dedicated to classical approaches as well as modern latent variable approaches. Numerous articles associated with longitudinal data and more specialized techniques round out this broad selection of topics.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 5 |

| October 2022 | 5 |

| October 2022 | 6 |

| October 2022 | 4 |

| October 2022 | 14 |

| October 2022 | 2 |

| October 2022 | 5 |

| October 2022 | 5 |

| October 2022 | 5 |

| October 2022 | 6 |

| October 2022 | 6 |

| October 2022 | 6 |

| October 2022 | 5 |

| October 2022 | 3 |

| October 2022 | 7 |

| October 2022 | 9 |

| October 2022 | 5 |

| October 2022 | 6 |

| October 2022 | 5 |

| October 2022 | 3 |

| October 2022 | 8 |

| October 2022 | 6 |

| October 2022 | 5 |

| October 2022 | 4 |

| October 2022 | 6 |

| October 2022 | 5 |

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 6 |

| November 2022 | 4 |

| November 2022 | 8 |

| November 2022 | 1 |

| November 2022 | 3 |

| November 2022 | 2 |

| November 2022 | 6 |

| November 2022 | 2 |

| November 2022 | 1 |

| November 2022 | 4 |

| November 2022 | 1 |

| November 2022 | 1 |

| November 2022 | 3 |

| November 2022 | 2 |

| November 2022 | 2 |

| November 2022 | 2 |

| November 2022 | 1 |

| November 2022 | 2 |

| November 2022 | 2 |

| November 2022 | 6 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 1 |

| December 2022 | 5 |

| December 2022 | 3 |

| December 2022 | 17 |

| December 2022 | 3 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 3 |

| December 2022 | 8 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 10 |

| December 2022 | 3 |

| December 2022 | 10 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 6 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 5 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 1 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 1 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 3 |

| December 2022 | 1 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| January 2023 | 2 |

| January 2023 | 4 |

| January 2023 | 6 |

| January 2023 | 38 |

| January 2023 | 5 |

| January 2023 | 4 |

| January 2023 | 5 |

| January 2023 | 2 |

| January 2023 | 9 |

| January 2023 | 6 |

| January 2023 | 2 |

| January 2023 | 3 |

| January 2023 | 3 |

| January 2023 | 4 |

| January 2023 | 5 |

| January 2023 | 4 |

| January 2023 | 2 |

| January 2023 | 2 |

| January 2023 | 1 |

| January 2023 | 2 |

| January 2023 | 4 |

| January 2023 | 2 |

| January 2023 | 2 |

| February 2023 | 2 |

| February 2023 | 11 |

| February 2023 | 7 |

| February 2023 | 5 |

| February 2023 | 5 |

| February 2023 | 5 |

| February 2023 | 5 |

| February 2023 | 4 |

| February 2023 | 2 |

| February 2023 | 8 |

| February 2023 | 3 |

| February 2023 | 4 |

| February 2023 | 3 |

| February 2023 | 2 |

| February 2023 | 7 |

| February 2023 | 4 |

| February 2023 | 4 |

| February 2023 | 4 |

| February 2023 | 4 |

| February 2023 | 3 |

| February 2023 | 2 |

| February 2023 | 1 |

| February 2023 | 2 |

| February 2023 | 2 |

| March 2023 | 15 |

| March 2023 | 3 |

| March 2023 | 6 |

| March 2023 | 8 |

| March 2023 | 1 |

| March 2023 | 6 |

| March 2023 | 19 |

| March 2023 | 9 |

| March 2023 | 2 |

| March 2023 | 10 |

| March 2023 | 3 |

| March 2023 | 16 |

| March 2023 | 5 |

| March 2023 | 4 |

| March 2023 | 1 |

| March 2023 | 7 |

| March 2023 | 16 |

| March 2023 | 7 |

| March 2023 | 1 |

| March 2023 | 12 |

| March 2023 | 3 |

| March 2023 | 3 |

| March 2023 | 4 |

| March 2023 | 7 |

| March 2023 | 6 |

| March 2023 | 5 |

| March 2023 | 14 |

| April 2023 | 2 |

| April 2023 | 7 |

| April 2023 | 3 |

| April 2023 | 6 |

| April 2023 | 7 |

| April 2023 | 5 |

| April 2023 | 3 |

| April 2023 | 13 |

| April 2023 | 14 |

| April 2023 | 6 |

| April 2023 | 8 |

| April 2023 | 3 |

| April 2023 | 6 |

| April 2023 | 2 |

| April 2023 | 14 |

| April 2023 | 2 |

| April 2023 | 3 |

| April 2023 | 9 |

| April 2023 | 12 |

| April 2023 | 2 |

| April 2023 | 4 |

| April 2023 | 1 |

| April 2023 | 3 |

| April 2023 | 4 |

| April 2023 | 4 |

| April 2023 | 3 |

| April 2023 | 1 |

| May 2023 | 4 |

| May 2023 | 3 |

| May 2023 | 3 |

| May 2023 | 5 |

| May 2023 | 7 |

| May 2023 | 1 |

| May 2023 | 2 |

| May 2023 | 5 |

| May 2023 | 2 |

| May 2023 | 2 |

| May 2023 | 1 |

| May 2023 | 2 |

| May 2023 | 4 |

| May 2023 | 5 |

| May 2023 | 1 |

| May 2023 | 2 |

| June 2023 | 4 |

| June 2023 | 1 |

| June 2023 | 9 |

| June 2023 | 7 |

| June 2023 | 5 |

| June 2023 | 5 |

| June 2023 | 2 |

| June 2023 | 4 |

| June 2023 | 3 |

| June 2023 | 5 |

| June 2023 | 3 |

| June 2023 | 3 |

| June 2023 | 5 |

| June 2023 | 4 |

| June 2023 | 5 |

| June 2023 | 4 |

| June 2023 | 3 |

| June 2023 | 3 |

| June 2023 | 1 |

| June 2023 | 2 |

| June 2023 | 4 |

| June 2023 | 7 |

| June 2023 | 1 |

| June 2023 | 3 |

| June 2023 | 2 |

| June 2023 | 5 |

| June 2023 | 2 |

| June 2023 | 2 |

| July 2023 | 2 |

| July 2023 | 1 |

| July 2023 | 8 |

| July 2023 | 9 |

| July 2023 | 5 |

| July 2023 | 5 |

| July 2023 | 5 |

| July 2023 | 9 |

| July 2023 | 3 |

| July 2023 | 5 |

| July 2023 | 1 |

| July 2023 | 2 |

| July 2023 | 6 |

| July 2023 | 4 |

| July 2023 | 1 |

| July 2023 | 3 |

| July 2023 | 2 |

| July 2023 | 2 |

| July 2023 | 1 |

| July 2023 | 1 |

| August 2023 | 5 |

| August 2023 | 2 |

| August 2023 | 7 |

| August 2023 | 12 |

| August 2023 | 4 |

| August 2023 | 2 |

| August 2023 | 5 |

| August 2023 | 9 |

| August 2023 | 2 |

| August 2023 | 8 |

| August 2023 | 3 |

| August 2023 | 1 |

| August 2023 | 3 |

| September 2023 | 2 |

| September 2023 | 2 |

| September 2023 | 5 |

| September 2023 | 6 |

| September 2023 | 23 |

| September 2023 | 3 |

| September 2023 | 8 |

| September 2023 | 4 |

| September 2023 | 6 |

| September 2023 | 4 |

| September 2023 | 13 |

| September 2023 | 2 |

| September 2023 | 6 |

| September 2023 | 3 |

| September 2023 | 2 |

| September 2023 | 3 |

| September 2023 | 2 |

| September 2023 | 4 |

| September 2023 | 2 |

| September 2023 | 2 |

| September 2023 | 5 |

| September 2023 | 2 |

| September 2023 | 1 |

| September 2023 | 4 |

| September 2023 | 2 |

| September 2023 | 2 |

| October 2023 | 2 |

| October 2023 | 8 |

| October 2023 | 15 |

| October 2023 | 11 |

| October 2023 | 3 |

| October 2023 | 1 |

| October 2023 | 4 |

| October 2023 | 4 |

| October 2023 | 8 |

| October 2023 | 2 |

| October 2023 | 3 |

| October 2023 | 2 |

| October 2023 | 4 |

| October 2023 | 2 |

| October 2023 | 5 |

| October 2023 | 2 |

| October 2023 | 5 |

| October 2023 | 1 |

| October 2023 | 2 |

| October 2023 | 4 |

| October 2023 | 1 |

| October 2023 | 5 |

| October 2023 | 2 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| November 2023 | 3 |

| November 2023 | 2 |

| November 2023 | 3 |

| November 2023 | 7 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| November 2023 | 2 |

| November 2023 | 3 |

| November 2023 | 4 |

| November 2023 | 2 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| November 2023 | 4 |

| November 2023 | 2 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| November 2023 | 7 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| December 2023 | 2 |

| December 2023 | 4 |

| December 2023 | 7 |

| December 2023 | 5 |

| December 2023 | 8 |

| December 2023 | 2 |

| December 2023 | 5 |

| December 2023 | 2 |

| December 2023 | 3 |

| December 2023 | 1 |

| December 2023 | 4 |

| December 2023 | 1 |

| December 2023 | 1 |

| December 2023 | 2 |

| January 2024 | 3 |

| January 2024 | 1 |

| January 2024 | 6 |

| January 2024 | 18 |

| January 2024 | 14 |

| January 2024 | 17 |

| January 2024 | 8 |

| January 2024 | 4 |

| January 2024 | 3 |

| January 2024 | 19 |

| January 2024 | 2 |

| January 2024 | 9 |

| January 2024 | 5 |

| January 2024 | 13 |

| January 2024 | 7 |

| January 2024 | 3 |

| January 2024 | 1 |

| January 2024 | 2 |

| January 2024 | 4 |

| January 2024 | 3 |

| January 2024 | 6 |

| January 2024 | 2 |

| January 2024 | 1 |

| January 2024 | 2 |

| January 2024 | 2 |

| January 2024 | 1 |

| January 2024 | 3 |

| January 2024 | 2 |

| February 2024 | 1 |

| February 2024 | 8 |

| February 2024 | 4 |

| February 2024 | 1 |

| February 2024 | 9 |

| February 2024 | 2 |

| February 2024 | 16 |

| February 2024 | 3 |

| February 2024 | 1 |

| February 2024 | 1 |

| February 2024 | 2 |

| February 2024 | 10 |

| February 2024 | 3 |

| February 2024 | 2 |

| February 2024 | 1 |

| February 2024 | 6 |

| February 2024 | 2 |

| February 2024 | 2 |

| February 2024 | 6 |

| February 2024 | 4 |

| February 2024 | 1 |

| February 2024 | 2 |

| March 2024 | 4 |

| March 2024 | 9 |

| March 2024 | 3 |

| March 2024 | 8 |

| March 2024 | 4 |

| March 2024 | 25 |

| March 2024 | 4 |

| March 2024 | 6 |

| March 2024 | 3 |

| March 2024 | 10 |

| March 2024 | 3 |

| March 2024 | 2 |

| March 2024 | 2 |

| March 2024 | 2 |

| March 2024 | 8 |

| March 2024 | 2 |

| March 2024 | 6 |

| March 2024 | 6 |

| March 2024 | 12 |

| March 2024 | 8 |

| March 2024 | 5 |

| March 2024 | 13 |

| March 2024 | 2 |

| March 2024 | 2 |

| March 2024 | 2 |

| March 2024 | 3 |

| March 2024 | 1 |

| March 2024 | 12 |

| April 2024 | 1 |

| April 2024 | 9 |

| April 2024 | 8 |

| April 2024 | 5 |

| April 2024 | 11 |

| April 2024 | 1 |

| April 2024 | 12 |

| April 2024 | 2 |

| April 2024 | 1 |

| April 2024 | 7 |

| April 2024 | 1 |

| April 2024 | 3 |

| April 2024 | 2 |

| April 2024 | 4 |

| April 2024 | 4 |

| April 2024 | 3 |

| April 2024 | 4 |

| April 2024 | 2 |

| April 2024 | 9 |

| April 2024 | 11 |

| May 2024 | 3 |

| May 2024 | 8 |

| May 2024 | 3 |

| May 2024 | 6 |

| May 2024 | 9 |

| May 2024 | 4 |

| May 2024 | 27 |

| May 2024 | 1 |

| May 2024 | 1 |

| May 2024 | 8 |

| May 2024 | 3 |

| May 2024 | 2 |

| May 2024 | 7 |

| May 2024 | 9 |

| May 2024 | 1 |

| May 2024 | 1 |

| May 2024 | 3 |

| May 2024 | 4 |

| May 2024 | 1 |

| May 2024 | 2 |

| June 2024 | 6 |

| June 2024 | 4 |

| June 2024 | 5 |

| June 2024 | 10 |

| June 2024 | 1 |

| June 2024 | 6 |

| June 2024 | 10 |

| June 2024 | 9 |

| June 2024 | 6 |

| June 2024 | 11 |

| June 2024 | 3 |

| June 2024 | 5 |

| June 2024 | 4 |

| June 2024 | 13 |

| June 2024 | 10 |

| June 2024 | 11 |

| June 2024 | 4 |

| June 2024 | 11 |

| June 2024 | 3 |

| June 2024 | 6 |

| June 2024 | 1 |

| June 2024 | 17 |

| June 2024 | 9 |

| June 2024 | 4 |

| June 2024 | 4 |

| June 2024 | 5 |

| June 2024 | 4 |

| July 2024 | 2 |

| July 2024 | 6 |

| July 2024 | 3 |

| July 2024 | 7 |

| July 2024 | 4 |

| July 2024 | 4 |

| July 2024 | 2 |

| July 2024 | 2 |

| July 2024 | 2 |

| July 2024 | 1 |

| July 2024 | 5 |

| July 2024 | 2 |

| July 2024 | 6 |

| July 2024 | 2 |

| July 2024 | 2 |

| July 2024 | 9 |

| July 2024 | 1 |

| July 2024 | 3 |

| July 2024 | 11 |

| July 2024 | 2 |

| July 2024 | 2 |

| July 2024 | 1 |

| July 2024 | 1 |

| July 2024 | 3 |

| August 2024 | 3 |

| August 2024 | 1 |

| August 2024 | 3 |

| August 2024 | 1 |

| August 2024 | 13 |

| August 2024 | 3 |

| August 2024 | 8 |

| August 2024 | 2 |

| August 2024 | 2 |

| August 2024 | 2 |

| August 2024 | 2 |

| August 2024 | 5 |

| August 2024 | 2 |

| August 2024 | 4 |

| August 2024 | 3 |

| August 2024 | 1 |

| August 2024 | 3 |

| August 2024 | 2 |

| August 2024 | 1 |

| August 2024 | 2 |

| August 2024 | 2 |

| September 2024 | 1 |

| September 2024 | 1 |

| September 2024 | 7 |

| September 2024 | 2 |

| September 2024 | 2 |

| September 2024 | 5 |

| September 2024 | 2 |

| September 2024 | 2 |

| September 2024 | 4 |

| September 2024 | 1 |

| September 2024 | 2 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Quantitative Research: A Successful Investigation in Natural and Social Sciences

- January 2021

- Journal of Economic Development Environment and People 9(4)

- CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

- Premier University

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Rabia Ghaffar

- Nargis Sultana

- Shafqat Ali

- Fábio Santiago

- Nwabueze Emekwuru

- Hendra Gunawan

- Rahmawaty Djaffar

- M. Fahrul Husni

- Muhammad Ashary Anshar

- Ahmad Zikri

- Nurhizrah Gustiati

- Rusdinal Rusdinal

- Kibrom Ejigu

- Tilahun Muluneh

- Devajit Mohajan

- Desyani Desyani

- Roya Yadegar

- Nimisha Mukund

- Nelson Pinheiro Gomes

- BMC MED RES METHODOL

- Monika Mueller

- Maddalena D’Addario

- Pippa Scott

- Hellmut Wollmann

- Paul Connolly

- Garry Anderson

- Nancy Arsenault

- Meredith Young

- Young Ho Lee

- Adela Clayton

- G. E. Gorman

- Peter Clayton

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Emotion Regulation and Academic Burnout Among Youth: a Quantitative Meta-analysis

- META-ANALYSIS

- Open access

- Published: 10 September 2024

- Volume 36 , article number 106 , ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Ioana Alexandra Iuga ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9152-2004 1 , 2 &

- Oana Alexandra David ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8706-1778 2 , 3

Emotion regulation (ER) represents an important factor in youth’s academic wellbeing even in contexts that are not characterized by outstanding levels of academic stress. Effective ER not only enhances learning and, consequentially, improves youths’ academic achievement, but can also serve as a protective factor against academic burnout. The relationship between ER and academic burnout is complex and varies across studies. This meta-analysis examines the connection between ER strategies and student burnout, considering a series of influencing factors. Data analysis involved a random effects meta-analytic approach, assessing heterogeneity and employing multiple methods to address publication bias, along with meta-regression for continuous moderating variables (quality, female percentage and mean age) and subgroup analyses for categorical moderating variables (sample grade level). According to our findings, adaptive ER strategies are negatively associated with overall burnout scores, whereas ER difficulties are positively associated with burnout and its dimensions, comprising emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and lack of efficacy. These results suggest the nuanced role of ER in psychopathology and well-being. We also identified moderating factors such as mean age, grade level and gender composition of the sample in shaping these associations. This study highlights the need for the expansion of the body of literature concerning ER and academic burnout, that would allow for particularized analyses, along with context-specific ER research and consistent measurement approaches in understanding academic burnout. Despite methodological limitations, our findings contribute to a deeper understanding of ER's intricate relationship with student burnout, guiding future research in this field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Does Burnout Affect Academic Achievement? A Meta-Analysis of over 100,000 Students

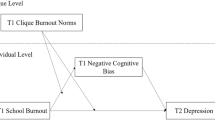

Antecedents of school burnout: A longitudinal mediation study

How School Burnout Affects Depression Symptoms Among Chinese Adolescents: Evidence from Individual and Peer Clique Level

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The transitional stages of late adolescence and early adulthood are characterized by significant physiological and psychological changes, including increased stress (Matud et al., 2020 ). Academic stress among students has long been studied in various samples, most of them focusing on university students (Bedewy & Gabriel, 2015 ; Córdova Olivera et al., 2023 ; Hystad et al., 2009 ) and, more recently, high school (Deb et al., 2015 ) and middle school students (Luo et al., 2020 ). Further, studies report an exacerbation of academic stress and mental health difficulties in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Guessoum et al., 2020 ), with children facing additional challenges that affect their academic well-being, such as increasing workloads, influences from the family, and the issue of decreasing financial income (Ibda et al., 2023 ; Yang et al., 2021 ). For youth to maintain their well-being in stressful academic settings, emotion regulation (ER) has been identified as an important factor (Santos Alves Peixoto et al., 2022 ; Yildiz, 2017 ; Zahniser & Conley, 2018 ).

Emotion regulation, referring to”the process by which individuals influence which emotions they have, when they have them, and how they experience and express their emotions” (Gross, 1998b ), represents an important factor in youth’s academic well-being even in contexts that are not characterized by outstanding levels of stress. Emotion regulation strategies promote more efficient learning and, consequentially, improve youth’s academic achievement and motivation (Asareh et al., 2022 ; Davis & Levine, 2013 ), discourage academic procrastination (Mohammadi Bytamar et al., 2020 ), and decrease the chances of developing emotional problems such as burnout (Narimanj et al., 2021 ) and anxiety (Shahidi et al., 2017 ).

Approaches to Emotion Regulation

Numerous theories have been proposed to elucidate the process underlying the emergence and progression of emotional regulation (Gross, 1998a , 1998b ; Koole, 2009 ; Larsen, 2000 ; Parkinson & Totterdell, 1999 ). One prominent approach, developed by Gross ( 2015 ), refers to the process model of emotion regulation, which lays out the sequential actions people take to regulate their emotions during the emotion-generative process. These steps involve situation selection, situation modification, attentional deployment, cognitive change, and response modulation. The kind and timing of the emotion regulation strategies people use, according to this paradigm, influence the specific emotions people experience and express.

Recent theories of emotion regulation propose two separate, yet interconnected approaches: ER abilities and ER strategies. ER abilities are considered a higher-order process that guides the type of ER strategy an individual uses in the context of an emotion-generative circumstance. Further, ER strategies are considered factors that can also influence ER abilities, forming a bidirectional relationship (Tull & Aldao, 2015 ). Researchers use many definitions and classifications of emotion regulation, however, upon closer inspection, it becomes clear that there are notable similarities across these concepts. While there are many models of emotion regulation, it's important to keep from seeing them as competing or incompatible since each one represents a unique and important aspect of the multifaceted concept of emotion regulation.

Emotion Regulation and Emotional Problems

The connection between ER strategies and psychopathology is intricate and multifaceted. While some researchers propose that ER’s effectiveness is context-dependent (Kobylińska & Kusev, 2019 ; Troy et al., 2013 ), several ER strategies have long been attested as adaptive or maladaptive. This body of work suggests that certain emotion regulation strategies (such as avoidance and expressive suppression) demonstrate, based on findings from experimental studies, inefficacy in altering affect and appear to be linked to higher levels of psychological symptoms. These strategies have been categorized as ER difficulties. In contrast, alternative emotion regulation strategies (such as reappraisal and acceptance) have demonstrated effectiveness in modifying affect within controlled laboratory environments, exhibiting a negative association with clinical symptoms. As a result, these strategies have been characterized as potentially adaptive (Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012a , 2012b ; Aldao et al., 2010 ; Gross, 2013 ; Webb et al., 2012 ).

A long line of research highlights the divergent impact of putatively maladaptive and adaptive ER strategies on psychopathology and overall well-being (Gross & Levenson, 1993 ; Gross, 1998a ). Increased negative affect, increased physiological reactivity, memory problems (Richards et al., 2003 ), a decline in functional behavior (Dixon-Gordon et al., 2011 ), and a decline in social support (Séguin & MacDonald, 2018 ) are just a few of the negative effects that have consistently been linked to emotional regulation difficulties, which include but are not limited to the use of avoidance, suppression, rumination, and self-blame strategies. Additionally, a wide range of mental problems, such as depression (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008 ), anxiety disorders (Campbell-Sills et al., 2006a , 2006b ; Mennin et al., 2007 ), eating disorders (Prefit et al., 2019 ), and borderline personality disorder (Lynch et al., 2007 ; Neacsiu et al., 2010 ) are connected to self-reports of using these strategies.

Conversely, putatively adaptive strategies, including acceptance, problem-solving, and cognitive reappraisal, have consistently yielded beneficial outcomes in experimental studies. These outcomes encompass reductions in negative emotional responses, enhancements in interpersonal relationships, increased pain tolerance, reductions in physiological reactivity, and lower levels of psychopathological symptoms (Aldao et al., 2010 ; Goldin et al., 2008 ; Hayes et al., 1999 ; Richards & Gross, 2000 ).

Notably, despite the fact that therapeutic techniquest for enhancing the use of adaptive ER strategies are core elements of many therapeutic approaches, from traditional Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) to more recent third-wave interventions (Beck, 1976 ; Hofmann & Asmundson, 2008 ; Linehan, 1993 ; Roemer et al., 2008 ; Segal et al., 2002 ), the association between ER difficulties and psychopathology frequently show a stronger positive correlation compared to the inverse negative association with adaptive ER strategies, as highlighted by Aldao and Nolen-Hoeksema ( 2012a ).

Pines & Aronson ( 1988 ) characterize burnout that arises in the workplace context as a state wherein individuals encounter emotional challenges, such as experiencing fatigue and physical exhaustion due to heightened task demands. Recently, driven by the rationale that schools are the environments where students engage in significant work, the concept of burnout has been extended to educational contexts (Salmela-Aro, 2017 ; Salmela-Aro & Tynkkynen, 2012 ; Walburg, 2014 ). Academic burnout is defined as a syndrome comprising three dimensions: exhaustion stemming from school demands, a cynical and detached attitude toward one's academic environment, and feelings of inadequacy as a student (Salmela-Aro et al., 2004 ; Schaufeli et al., 2002 ).

School burnout has quickly garnered international attention, despite its relatively recent emergence, underscoring its relevance across multiple nations (Herrmann et al., 2019 ; May et al., 2015 ; Meylan et al., 2015 ; Yang & Chen, 2016 ). Similar to other emotional difficulties, it has been observed among students from various educational systems and academic policies, suggesting that this phenomenon transcends cultural and geographical boundaries (Walburg, 2014 ).

The link between ER and school burnout can be understood through Gross's ( 1998a ) process model of emotion regulation. This model suggests that an individual's emotional responses are influenced by their ER strategies, which are adaptive or maladaptive reactions to stressors like academic pressure. Given that academic stress greatly influences school burnout (Jiang et al., 2021 ; Nikdel et al., 2019 ), the ER strategies students use to manage this stress may impact their likelihood of experiencing burnout. In essence, whether a student employs efficient ER strategies or encounters ER difficulties could influence their susceptibility to school burnout.

The exploration of ER in relation to student burnout has garnered attention through various studies. However, the existing body of research is not yet robust enough, and its outcomes are not universally congruent. Suppression, defined as efforts to inhibit ongoing emotional expression (Balzarotti et al., 2010 ), has demonstrated a positive and significant correlation with both general and specific burnout dimensions (Chacón-Cuberos et al., 2019 ; Seibert et al., 2017 ), with the exception of the study conducted by Yu et al., ( 2022 ), where there is a negative, but not significant association between suppression and reduced accomplishment. Notably, research by Muchacka-Cymerman and Tomaszek ( 2018 ) indicates that ER strategies, encompassing both dispositional and situational approaches, exhibit a negative relationship with overall burnout. Situational ER, however, displays a negative impact on dimensions like inadequacy and declining interest, particularly concerning the school environment.

Cognitive ER strategies such as reappraisal, positive refocusing, and planning are, generally, negatively associated with burnout, while self-blame, other-blame, rumination, and catastrophizing present a positive association with burnout (Dominguez-Lara, 2018 ; Vinter et al., 2021 ). It's important to note that these relationships have not been consistently replicated across all investigations. Inconsistencies in the findings highlight the complexity of the interactions and the potential influence of various contextual factors. Consequently, there remains a critical need for further research to thoroughly examine these associations and identify the factors contributing to the variability in results.

Existing Research

Although we were unable to identify any reviews or meta-analyses that synthesize the literature concerning emotion regulation strategies and student burnout, recent meta-analyses have identified the role of emotion regulation across pathologies. A recent network meta-analysis identified the role of rumination and non-acceptance of emotions to be closely related to eating disorders (Leppanen et al., 2022 ). Further, compared to healthy controls, people presenting bipolar disorder symptoms reported significantly higher difficulties in emotion regulation (Miola et al., 2022 ). Weiss et al. ( 2022 ) identified a small to medium association between emotion regulation and substance use, and a subsequent meta-analysis conducted by Stellern et al. ( 2023 ) confirmed that individuals with substance use disorders have significantly higher emotion regulation difficulties compared to controls. The study of Dawel et al. ( 2021 ) represents the many research papers asking the question”Cause or symptom” in the context of emotion regulation. The longitudinal study brings forward the bidirectional relationship between ER and depression and anxiety, particularly in the case of suppression, suggesting that suppressing emotions is indicative of and can predict psychological distress.

Despite the increasing research attention to academic burnout in recent years, the current body of literature primarily concentrates on specific groups such as medical students (Almutairi et al., 2022 ; Frajerman et al., 2019 ), educators (Aloe et al., 2014 ; Park & Shin, 2020 ), and students at the secondary and tertiary education levels (Madigan & Curran, 2021 ) in the context of meta-analyses and reviews. A limited number of recent reviews have expanded their focus to include a more diverse range of participants, encompassing middle school, graduate, and university students (Kim et al., 2018 , 2021 ), with a particular emphasis on investigating social support and exploring the demand-control-support model in relation to student burnout.

The significance of managing burnout in educational settings is becoming more widely acknowledged, as seen by the rise in interventions designed to reduce the symptoms of burnout in students. Specific interventions for alleviating burnout symptoms among students continue to proliferate (Madigan et al., 2023 ), with a focus on stress reduction through mindfulness-based strategies (Lo et al., 2021 ; Modrego-Alarcón et al., 2021 ) and rational-emotive behavioral techniques (Ogbuanya et al., 2019 ) to enhance emotion-regulation skills (Charbonnier et al., 2022 ) and foster rational thinking (Bresó et al., 2011 ; Ezeudu et al., 2020 ). This underscores the significance of emotion regulation in addressing burnout.

Despite several randomized clinical trials addressing student burnout and an emerging body of research relating emotion regulation and academic burnout, there's a lack of a systematic examination of how emotion regulation strategies relate to various dimensions of student burnout. This highlights the necessity for a systematic review of existing evidence. The current meta-analysis addresses the association between emotion regulation strategies and student burnout.

A secondary objective is to test the moderating effect of school level and female percentage in the sample, as well as study quality, in order to identify possible sources of heterogeneity among effect sizes. By analyzing the moderating effect of school level and gender, we may determine if the strength of the association between student burnout and emotion regulation is contingent upon the educational setting and participant characteristics. This offers information on the findings' generalizability to all included student demographics, including those in elementary, middle, and secondary education and of different genders. Additionally, the reliability and validity of meta-analytic results rely on the evaluation of research quality, and the inclusion of study quality rating allows us to determine if the observed association between emotion regulation and student burnout differs based on the methodological rigor of the included studies.

Materials and Methods

Study protocol.

The present meta-analysis has been carried out following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher et al., 2009 ). The protocol for the meta-analysis was pre-registered in PROSPERO (PROSPERO, 2022 CRD42022325570).

Selection of Studies

A systematic search was performed using relevant databases (PubMed, Web of Science, PsychINFO, and Scopus). The search was carried out on 25 May of 2023 using 25 key terms related to the variables of interest, such as: (a) academic burnout, (b) school burnout, (c) student burnout (d) education burnout, (d) exhaustion, (e) cynicism, (f) inadequacy, (g) emotion regulation, (h) coping, (i) self-blame, (j) acceptance, and (h) problem solving.

Studies of any design published in peer-reviewed journals were eligible for inclusion, provided they used empirical data to assess the relationship between student burnout and emotion regulation strategies. Only studies that employed samples of children, adolescents, and youth were eligible for inclusion. For the purpose of the current paper, we define youth as people aged 18 to 25, based on how it is typically defined in the literature (Westhues & Cohen, 1997 ).

Studies were excluded from the meta-analysis if they: (a) were not a quantitative study, (b) did not explore the relationship between academic burnout and emotion regulation strategies, (c) did not have a sample that can be defined as consisting of children and youth (Scales et al., 2016 ), (e) did not utilize Pearson’s correlation or measures that could be converted to a Pearson’s correlation, (f) include medical school or associated disciplines samples.

Statistical Analysis

For the data analysis, we employed Comprehensive Meta-Analysis 4 software. Anticipating significant heterogeneity in the included studies, we opted for a random effects meta-analytic approach instead of a fixed-effects model, a choice that acknowledges and accounts for potential variations in effect sizes across studies, contributing to a more robust and generalizable synthesis of the results. Heterogeneity among the studies was assessed using the I 2 and Q statistics, adhering to the interpretation thresholds outlined in the Cochrane Handbook (Deeks et al., 2023 ).

Publication bias was assessed through a multi-faceted approach. We first examined the funnel plot for the primary outcome measures, a graphical representation revealing potential asymmetry that might indicate publication bias. Furthermore, we utilized Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill procedure (Duval & Tweedie, 2000 ), as implemented in CMA, to estimate the effect size after accounting for potential publication bias. Additionally, Egger's test of the intercept was conducted to quantify the bias detected by the funnel plot and to determine its statistical significance.

When dealing with continuous moderating variables, we employed meta-regression to evaluate the significance of their effects. For categorical moderating variables, we conducted subgroup analyses to test for significance. To ensure the validity of these analyses, it was essential that there was a minimum of three effect sizes within each subgroup under the same moderating variable, following the guidelines outlined by Junyan and Minqiang ( 2020 ). In accordance with the guidance provided in the Cochrane Handbook (Schmid et al., 2020 ), our application of meta-regression analyses was limited to cases where a minimum of 10 studies were available for each examined covariate. This approach ensures that there is a sufficient number of studies to support meaningful statistical analysis and reliable conclusions when exploring the influence of various covariates on the observed relationships.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

In addition to the identification information (i.e., authors, publication year), we extracted data required for the effect size calculation for the variables relevant to burnout and emotion regulation strategies. Where data was unavailable, the authors were contacted via email in order to provide the necessary information. Potential moderator variables were coded in order to examine the sources of variation in study findings. The potential moderators included: (a) participants’ gender, (b), grade level (c) study quality, and (d) mean age.

The full-text articles were independently assessed using the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields tool (Kmet et al., 2004 ) by a pair of coders (II and SM), to ensure the reliability of the data, resulting in a substantial level of agreement (Cohen’s k = 0.89). The disagreements and discrepancies between the two coders were resolved through discussion and consensus. If consensus could not be reached, a third researcher (OD) was consulted to resolve the disagreement.

The checklist items focused on evaluating the alignment of the study's design with its stated objectives, the methodology employed, the level of precision in presenting the results, and the accuracy of the drawn conclusions. The assessment criteria were composed of 14 items, which were evaluated using a 3-point Likert scale (with responses of 2 for "yes," 1 for "partly," and 0 for "no"). A cumulative score was computed for each study based on these items. For studies where certain checklist items were not relevant due to their design, those items were marked as "n/a" and were excluded from the cumulative score calculation.

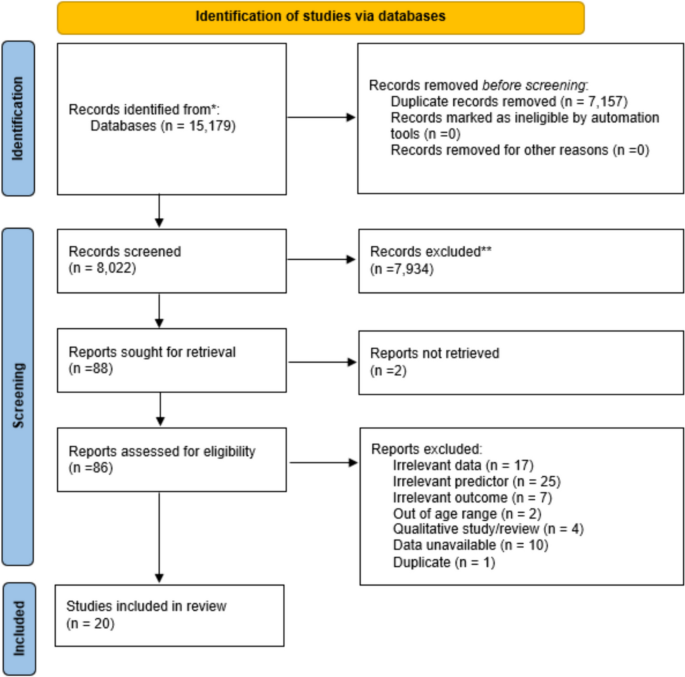

Study Selection

The combined search terms yielded a total of 15,179 results. The duplicate studies were removed using Zotero, and a total of 8,022 studies remained. The initial screening focused on the titles and abstracts of all remaining studies, removing all documents that target irrelevant predictors or outcomes, as well as qualitative studies and reviews. Two assessors (II and SA) independently screened the papers against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A number of 7,934 records were removed, while the remaining 88 were sought for retrieval. Out of the 88 articles, we were unable to find one, while another has been retracted by the journal. Finally, 86 articles were assessed for eligibility. A total of 20 articles met the inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1 ). Although a specific cutoff criterion for reliability coefficients was not imposed during study selection, the majority of the included studies had alpha Cronbach values for the instruments assessing emotion regulation and school burnout greater than 0.70.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart of the study selection process

Data Overview

Among the included studies, four focused on middle school students, two encompassed high school student samples, and the remaining 14 articles involved samples of university students. The majority of the included studies had cross-sectional designs (17), while the rest consisted of 2 longitudinal studies and one non-randomized controlled pilot study. The percentage of females within the samples ranged from 46% to 88.3%, averaging 65%, while the mean age of participants ranged from 10.39 to 25. The investigated emotional regulation strategies within the included studies exhibit variation, encompassing other-blame, self-blame, acceptance, rumination, catastrophizing, putting into perspective, reappraisal, planning, behavioral and mental disengagement, expressive suppression, and others (see Table 1 for a detailed study presentation).

Study Quality

Every study surpasses a quality threshold of 0.60, and 75% of the studies achieve a score above the more conservative threshold indicated by Kmet et al. ( 2004 ). This indicates a minimal risk of bias in these studies. Moreover, 80% of the studies adequately describe their objectives, while the appropriateness of the study design is recognized in 50% of the cases, mostly utilizing cross-sectional designs. While 95% of the studies provide sufficient descriptions of their samples, only 10% employ appropriate sampling methods, with the majority relying on convenience sampling. Notably, there is just one interventional study that lacks random allocation and blinding of investigators or subjects.

In terms of measurement, 85% of the studies employ validated and reliable tools. Adequacy in sample size and well-justified and appropriate analytic methods are observed across all included studies. While approximately 50% of the studies present estimates of variance, a mere 30% of them acknowledge the control of confounding variables. Lastly, 95% of the studies provide results in comprehensive detail, with 60% effectively grounding their discussions in the obtained results. The quality assessment criteria and results can be consulted in Supplementary Material 4 .

Pooled Effects

A sensitivity analysis using standardized residuals was conducted. Provided that the residuals are normally distributed, 95% of them would fall within the range of -2 to 2. Residuals outside this range were considered unusual. We applied this cutoff in our meta-analysis to identify any outliers. The results of the analysis revealed that several relationships had standardized residuals falling outside the specified range. Re-analysis excluding these outliers demonstrated that our initial results were robust and did not significantly change in magnitude or significance. As a result, we have moved on with the analysis for the entire sample.

The calculated overall effects can be consulted in Table 2 . The correlation between ER difficulties and student burnout is a significant one, with significant positive associations between ER difficulties and overall burnout (k = 13), r = 0.25 (95% CI = 0.182; 0.311), p < 0.001, as well as individual burnout dimensions: cynicism (k = 9), r = 0.28 (95% CI = 0.195; 0.353) p < 0.001, lack of efficacy (k = 8), r = 0.17 (95% CI = 0.023; 0.303), p < 0.05 and emotional exhaustion (k = 11), r = 0.27 (95% CI = 0.207; 0.335) p < 0.001. Regarding the relationship between adaptive ER strategies and student burnout, a statistically significant result is observed solely between overall student burnout and adaptive ER (k = 17), r = -14 (95% CI = -0.239; 0.046) p < 0.005. The forest plots can be consulted in Supplementary Material 1 .

Heterogeneity and Publication Bias

Table 3 shows that all Q tests were significant, indicating that there is significant variation among the effect sizes of the individual studies included in the meta-analysis. Further, all I 2 indices are over 75%, ranging from 83.67% to 99.32%, which also indicates high heterogeneity (Borenstein et al., 2017 ). This consistently high level of heterogeneity indicates substantial variation in effect sizes, pointing to influential factors that significantly shape the outcomes of the included studies. Consequentially, subgroup and meta-regression analyses are to be carried out in order to unravel the underlying factors driving this pronounced heterogeneity. The results of the publication bias analysis are presented individually below and, additionally, you can consult the funnel plots included in Supplementary Material 2 .

Adaptive ER and School Burnout

Upon visual examination of the funnel plot, asymmetry to the right of the mean was observed. To validate this observation, a trim-and-fill analysis using Duval and Tweedie’s method was conducted, revealing the absence of three studies on the left side of the mean. The adjusted effect size ( r = -0.17, 95% CI [0.27; 0.68]) resulting from this analysis was found to be higher than the initially observed effect size. Nevertheless, the application of Egger’s test did not yield a significant indication of publication bias ( B = -5.34, 95% CI [-11.85; 1.16], p = 0.10).

Adaptive ER and Cynicism

Following a visual examination of the funnel plot, a symmetrical arrangement of effect sizes around the mean was apparent. This finding was contradicted by the application of Duval and Tweedie's trim-and-fill method, which revealed two missing studies to the right of the mean. The adjusted effect size ( r = 0.04, 95% CI [-0.21; 0.13]) is smaller than the initially observed effect size. The application of Egger’s test did not yield a significant indication of publication bias ( B = -2.187, 95% CI [-8.57; 4.19], p = 0.43).

ER difficulties and Lack of Efficacy

The visual examination of the funnel plot revealed asymmetry to the right of the mean. This finding was validated by the application of Duval and Tweedie's trim-and-fill method, which revealed two missing studies to the left of the mean and a lower adjusted effect size ( r = 0.08, 95% CI [-0.07; 0.23]), the effect becoming statistically non-significant. The application of Egger’s test did not yield a significant indication of publication bias ( B = 7.76, 95% CI [-16.53; 32.05], p = 0.46).

Adaptive ER and Emotional Exhaustion

The visual examination of the funnel plot revealed asymmetry to the left of the mean. The trim-and-fill method also revealed one missing study to the right of the mean and a lower adjusted effect size ( r = 0.00, 95% CI [-0.13; 0.12]). The application of Egger’s test did not yield a significant indication of publication bias ( B = 7.02, 95% CI [-23.05; 9.02], p = 0.46).

Adaptive ER and Lack of Efficacy; ER difficulties and School Burnout, Cynicism, and Exhaustion

Upon visually assessing the funnel plot, a balanced distribution of effect sizes centered around the mean was observed. This observation is corroborated by the application of Duval and Tweedie's trim-and-fill method, which also revealed no indication of missing studies. The adjusted effect size remained consistent, and the intercept signifying publication bias was found to be statistically insignificant.

Moderator Analysis

We performed moderator analyses for the categorical variables, in the case of significant relationships that were uncovered in the initial analysis. These analyses were carried out specifically for cases where there were more than three effect sizes available within each subgroup that fell under the same moderating variable.

Students’ grade level was used as a categorical moderator. Pre-university students included students enrolled in primary and secondary education, while the university student category included tertiary education students. The results, presented in Table 4 , show that the moderating effect of grade level is not significant for the relationship between adaptive ER and overall school burnout Q (1) = 0.20, p = 0.66. At a specific level, the moderating effect is significant for the relationship between ER difficulties and overall burnout Q (1) = 9.81, p = 0.002, cynicism Q (1) = 16.27, p < 0.001, lack of efficacy Q (1) = 15.47 ( p < 0.001), and emotional exhaustion Q (1) = 13.85, p < 0.001. A particularity of the moderator analysis in the relationship between ER difficulties and lack of efficacy is that, once the effect of the moderator is accounted for, the relationship is not statistically significant anymore for the university level, r = -0.01 (95% CI = -0.132; 0.138), but significant for the pre-university level, r = 0.33 (95% CI = 0.217; 0.439).

Meta-regressions

Meta-regression analyses were employed to examine how the effect size or relationship between variables changes based on continuous moderator variables. We included as moderators the female percentage (the proportion of female participants in each study’s sample) and the study quality assessed based on the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields tool (Kmet et al., 2004 ).

Results, presented in Table 5 , show that study quality does not significantly influence the relationship between ER and school burnout. The proportion of female participants in the study sample significantly influences the relationship between ER difficulties and overall burnout ( β , -0.0055, SE = 0.001, p < 0.001), as well as the emotional exhaustion dimension ( β , -0.0049, SE = 0.002, p < 0.01). Mean age significantly influences the relationship between ER difficulties and overall burnout ( β , -0.0184, SE = 0.006, p < 0.01). Meta-regression plots can be consulted in detail in Supplementary Material 3 .