This issue: Summer 2020

COVID-19 Photo Essay

Photos by Chris Low

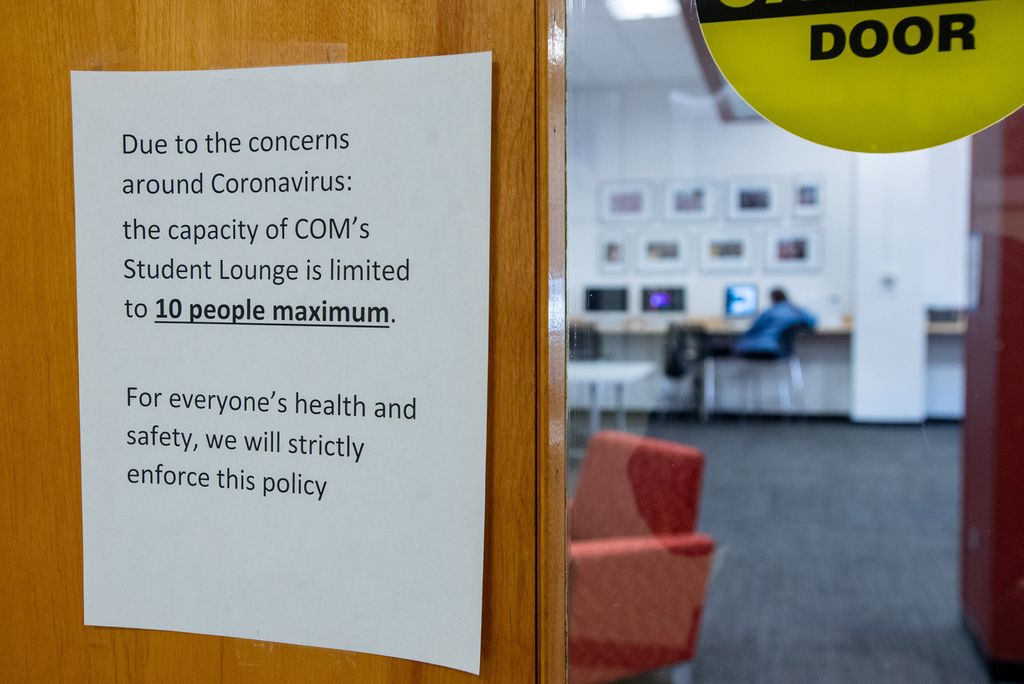

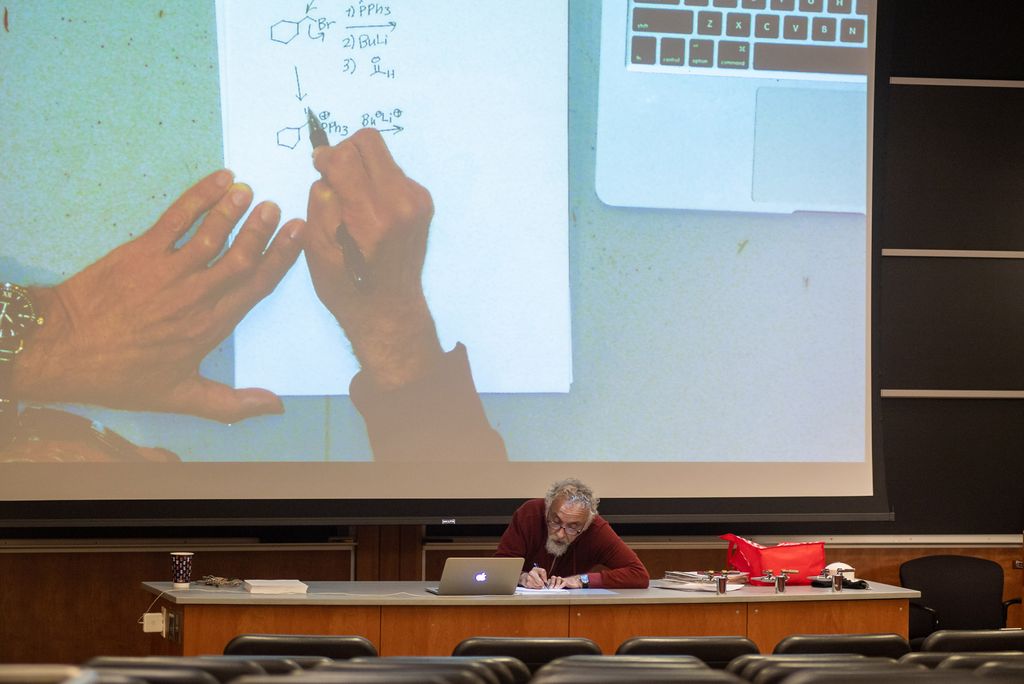

A new reality: As news of the spread of COVID-19 became more prevalent, students began practicing social distancing and other safety precautions in the classroom. In late March, campus was closed to comply with Oregon’s “Stay Home, Save Lives” mandate.

Sign of the times: A traffic sign on highway 99W reminds drivers coming into Newberg to avoid large group gatherings.

Strength in community: While campus was closed, the Bruin Community Pantry food bank remained open, with enhanced safety protocols, to ensure that no George Fox student went hungry.

Social distancing: A student sits alone in the university’s outdoor amphitheater. As students moved home to begin remote learning, sights like this around campus became much more common.

Meeting of the minds: The university leadership team, including President Robin Baker, connects via Zoom to discuss how best to care for students in a remote learning environment.

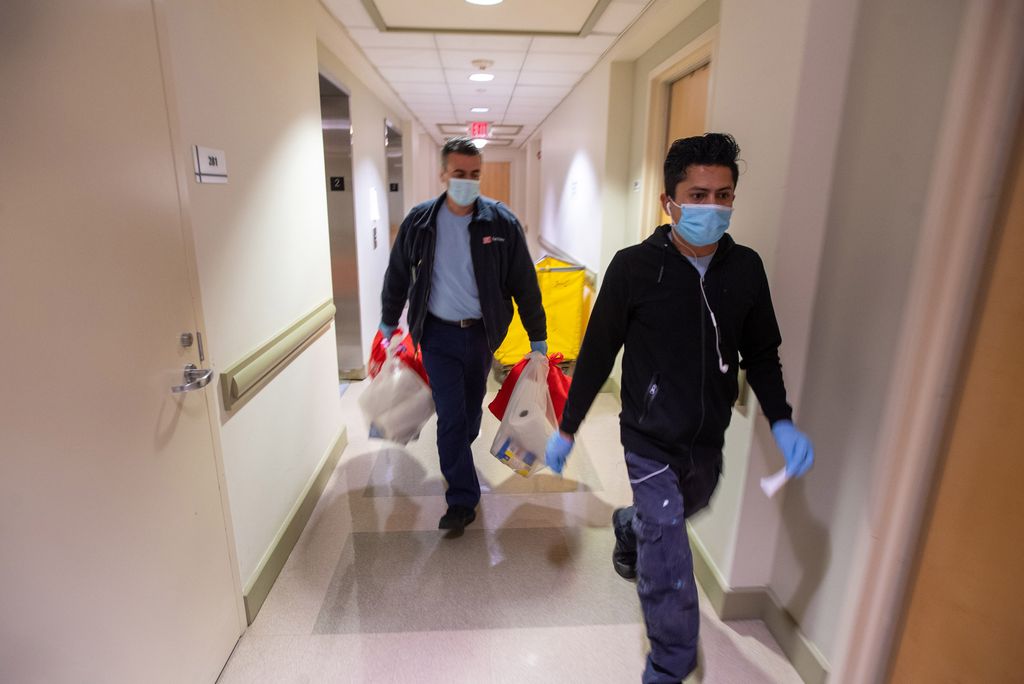

Deep cleaning: A Jani-King employee disinfects one of the residence hall bathrooms.

Home/work: English professor Jessica Ann Hughes leads class from a makeshift home office.

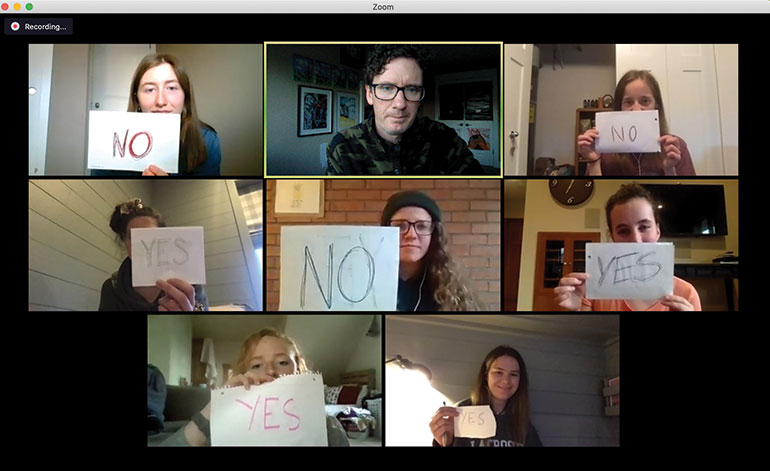

Virtual classroom: Biblical studies professor Brian Doak finds a creative way to engage with students.

Signs of hope: George Fox alumna Jessica (Lavarias) Brittell (’06), co-owner of MOB Signs, created this display outside the Providence Newberg Medical Center to show appreciation for doctors and nurses on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The university that prays together… Jake Thiessen and Moses Hooper from the marketing communications department pray before a virtual meeting.

Featured Stories

The Class of COVID-19

COVID-19 Through the Eyes of Students

Engineering a Solution

Essential Personnel

Friendship House

Taking Aim at the Opioid Epidemic

What's Next

52 Years and Counting

A Century of Mentorship

Going for Gold

PNW Adventures

Serving with Passion

Bruin Notes

- More than $139,000 Raised for Students Affected by Coronavirus

- COVID-19 Pandemic Leads to Spring Semester Unlike Any Other

- Faculty Members Honored as Top Teachers, Researchers for 2019-20

- George Fox Digital to Deliver Be Known Promise in Online Format

- Development of Patient-Centered Care Model Puts DPT Program in National Spotlight

- Physician Assistant Program Set to Launch in 2021

- Rankings Roundup: George Fox Earns Top Spot Among Christian Colleges in Oregon

- Recent Recognition

- Scott Selected as New Provost

Alumni Connections

- Art and Entrepreneurship

- Art with an Impact

- Babies and Marriages

- News, by Graduating Year

- Not a Spectator

- Working in Small Infinities

- Send Us Your News

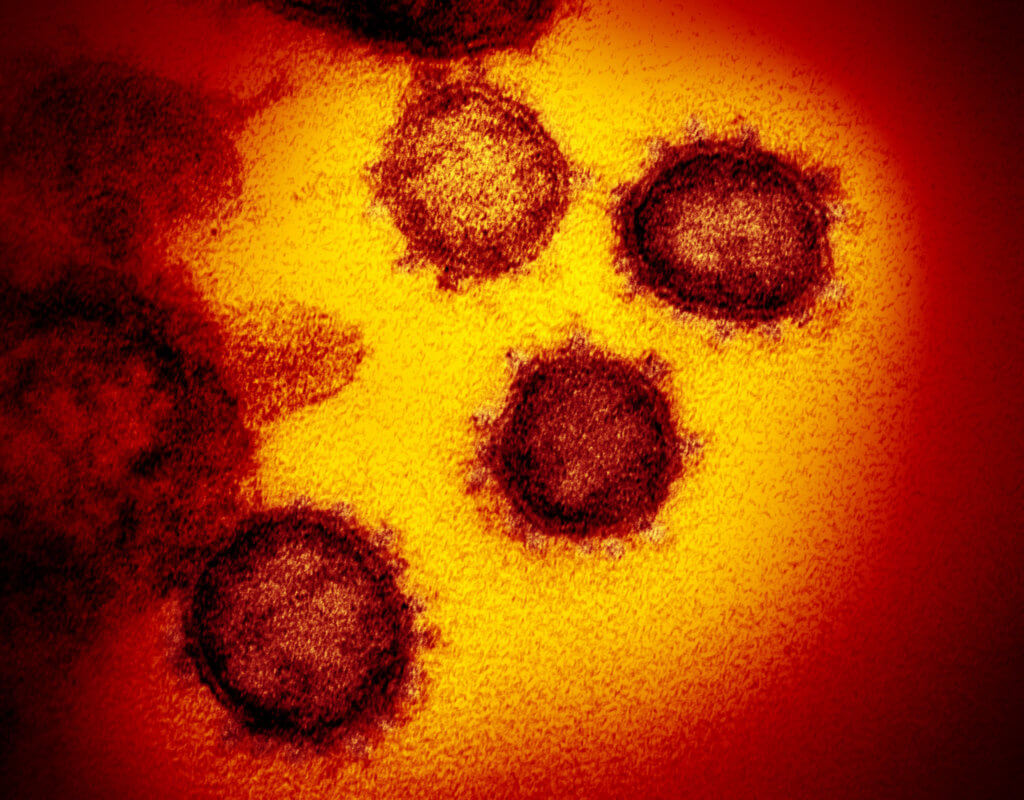

Coronavirus

COVID-19 photo essay reflects on the day our lives changed forever three years ago

While it feels almost a lifetime ago for some, it's been exactly three years since a state of emergency was declared in Western Australia as the novel coronavirus began to send shock waves around the world.

Already isolated by its geography, the unprecedented move cemented the state as a hermit kingdom and fundamentally changed the way sandgropers went about their daily lives.

This picture essay illustrates a pivotal and unsettling chapter in our history, and reflects how the virus dictated the way we lived.

Panic and confusion

COVID-19 was first detected in the Chinese city of Wuhan in December 2019, but the panic didn't set in until a couple of months later when news of mass deaths overseas was beamed in to living rooms across Australia.

The virus captivated the entire world, but the threat really hit home when Australia recorded its first COVID death on March 1 — a Perth man who had been aboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship.

Australians were given a stern warning to return home as soon as possible ahead of the country's border being slammed shut, with international arrivals forced into hotel quarantine in an effort to stop the deadly virus getting in.

The first round of COVID-19 restrictions, including gathering limits and indoor venue closures, started to give people an inkling of how much their lives were about to be turned upside down.

Holidays and big events were cancelled, weddings went online and Rottnest Island went from the home of quokka selfies to a quarantine hub for cruise ship passengers.

Lines curled around liquor stores as the fear of being locked down without a cold stubbie or red wine in hand was too much to bear for most, while subscriptions to streaming services went through the roof.

Grocery store shelves were stripped bare and arguments broke out in supermarket aisles as panic buying led to a nationwide toilet paper drought.

ABC reporter Francesca Mann dared to dream when she saw a shopper walk past her with the rare commodity at a Geraldton supermarket.

"I could not believe my eyes," she said.

"I quickly walked over to the toilet paper aisle and there were about seven packs left. It felt like the most valuable item at the time, so it got the royal treatment on the way home."

Mann snapped an equally humorous shot of her pet cat Arya sprawled across her desk in the first few days of working from home.

'Stop the spread'

The state introduced its first round of border restrictions at the end of March, restricting interstate travel to stop the virus spreading between regions and to protect vulnerable Indigenous communities.

On April 5, 2020, the WA government implemented its harshest border restrictions yet, slamming its borders shut — not just to international arrivals, but to the east as well.

It marked the beginning of an upsetting chapter in the state's history, leaving families divided for two years and living up to Premier Mark McGowan's promise to turn WA into an "island within an island".

The travel restrictions wreaked havoc on the tourism and events industries, but it also created a spike in domestic tourism when the state eased restrictions to allow West Australians to holiday in their own backyard.

Sandgropers swapped their annual pilgrimage to Bali for the sublime sunsets in Broome, the chance to swim with whale sharks in Exmouth or to see the ancient gorges in the Karijini National Park.

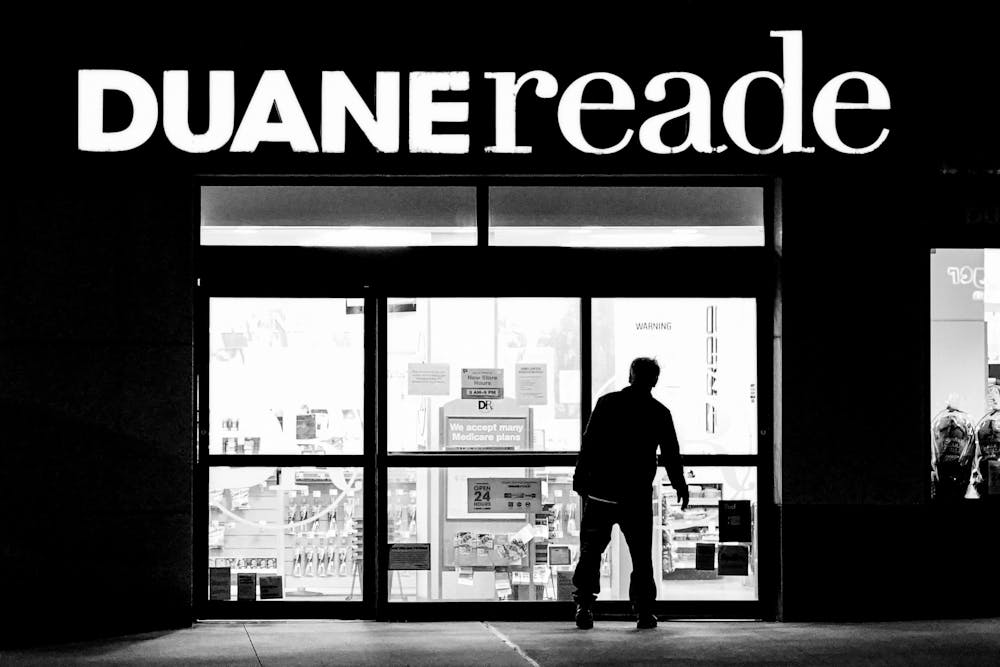

But Perth's bustling city centre had turned into a ghost town as West Australians dutifully obeyed restrictions, which shut down the city.

Just a few pedestrians could be spotted in Forrest Place in April, 2020. Image: Hugh Sando.

Even a trip to the beach came with reminders to practise social distancing. Image: Amelia Searson.

Trains crisscrossed the city virtually empty. Image: Hugh Sando.

The doors to restaurants, cafes and bars were shuttered. Image: Rebecca Mansell.

The state library was eerily empty. Image: Emma Wynne.

Children were cooped up inside as playgrounds closed. Image: Gian De Poloni.

Slogans like this started popping up around Perth as people banded together to face the crisis. Image: Damian Smith.

For weeks, the cruise ship Artania became the focus of a tense stand-off between the operator and Mr McGowan, who demanded it leave WA waters.

Anzac Day that year was unlike any other due to the traditional service and march being cancelled — the first time since 1942.

Veterans and families instead marked Anzac Day from the end of their suburban driveways.

By this stage, the virus dominated every aspect of our lives.

Even the security guard, Steve, who opened the door for the premier before he delivered his daily press conference, had become part of life under COVID.

Living inside the bubble

Restrictions were gradually eased in May after the virus was eliminated, allowing West Australians to continue living relatively normally for many months compared to what was happening over east.

With no community transmission, WA moved from a hard border to a controlled border in October, with authorities continually lowering and lifting the drawbridge in line with outbreaks in other states.

On December 5, a tool was unveiled that would dramatically change the way West Australians interacted with the world around them.

The trio of snap lockdowns

But it was impossible to keep the virus out forever, with the state's 10-month coronavirus-free streak ending on January 21, 2021 when a hotel quarantine security guard tested positive.

Perth was locked down twice more in 2021 — from April 24 to April 27 after a hotel quarantine outbreak and from June 29 to July 3 after three COVID cases were detected in the community.

Vaccine hesitancy takes hold

In October, one of the most divisive policies in WA's history was announced — mandatory vaccination for 75 per cent of the state's workforce.

Some were concerned about potential health impacts from the vaccine and felt it was impinging on people's right to have autonomy over their own bodies, while others felt it was the only way to reopen the borders and protect people from the virus.

When the double-dose vaccination rate reached 80 per cent in December, it was announced that WA would finally reopen its border to the rest of the world on February 5, 2022.

But the joy that rippled through the community was short-lived, with WA Premier Mark McGowan performing a sensational backflip just a few weeks later at a late night press conference when he announced the reopening would be delayed.

However, it turned out the virulent strain was circulating in the community anyway, and the virus started to spread significantly for the first time in two years.

'Let it rip'

On February 18, Mr McGowan made the announcement many had been waiting for — WA's hard border would come down on March 3 as he conceded it was no longer possible to stop the spread of the virus.

Many employers, including ABC News in Perth, quickly reverted to working from home arrangements for all but operationally critical staff to minimise the risk of spreading the virus in the workplace.

As case numbers grew, so too did tensions between the state government and peak medical groups that warned against easing restrictions, as cracks in the hospital system deepened.

After being on the frontline of the battle against COVID, health workers began rallying for better pay, which would eventually lead to full-scale industrial action.

As vaccination rates rose and the COVID outbreak in WA eased in April, the McGowan Government lifted most mask-wearing requirements but the Perth CBD remained a ghost town.

Most remaining restrictions were removed in May as the triple-dose vaccination rate hit 80 per cent, but many vulnerable West Australians chose to stay home to shield themselves from the virus.

But COVID continued to fade into the background for most, as the things that derailed our lives — lockdowns, mandatory isolation, mask and vaccine mandates— gradually became distant memories.

Living with the virus

People have learned how to live with the virus, and getting the vaccine has become about as normal as getting a yearly flu jab.

After 963 days, WA's state of emergency finally ended on November 4, but the heartache caused by the 956 people who lost their lives, and the far-reaching impact on society and people's livelihoods, will be felt for years to come.

- X (formerly Twitter)

Related Stories

Three years into the pandemic, it's clear covid won't fix itself. here's what we need to focus on next.

When I caught COVID, I thought I'd get back to normal. I was wrong

Take a look at life behind WA's hard border if you want to see a post-COVID world

- State and Territory Government

- HISTORY & CULTURE

- CORONAVIRUS COVERAGE

Photos show the first 2 years of a world transformed by COVID-19

Our photographers bore witness to the ways the world has coped—and changed—since the pandemic began.

Two years ago this month, on March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization formally declared a pandemic caused by a novel coronavirus . And as COVID-19 spread across the globe, humanity had little time to adapt to lockdowns and staggering losses.

Nearly six million people have died from the disease so far, a death toll that experts say barely scratches the surface of the pandemic’s true harm. Hospitals and health care workers have been pushed to the brink, debates over masking have tested our bonds, and millions of grieving families will never truly return to life as normal—if it’s even possible to go back to a time when “social distancing” was an alien concept.

Over past two years, National Geographic has documented how the world has coped with COVID-19 through the lenses of more than 80 photographers in dozens of countries. In the frightening early days, Cédric Gerbehave’s haunting image of Belgian nurses revealed the trauma of hospitals overrun by a disease that scientists didn’t yet understand. Tamara Merino confronted the overwhelming isolation of confinement during lockdown in Chile. And Muhammad Fadli took us to the gravesite of one of the many COVID-19 victims whose bodies filled up an Indonesian cemetery.

Our photographers have also shown us how the world adapted to these challenges. Families found new ways to connect when social distancing kept us from our loved ones, and new ways to grieve when we couldn’t hold funerals. Schools from Haiti to South Korea were able to safely reopen with mask mandates, smaller classes, and exams taken outdoors. And the 2021 graduating class of Howard University found a joyous way to celebrate commencement outdoors: by dancing down the streets of Washington, D.C.

Now, as we enter the pandemic’s third year, scientists warn that it isn’t over yet. More than 10 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines have been administered globally—but that isn’t enough to quell the danger of future surges and even more deadly variants . Still, there’s reason to hope that we’ll finally find our way toward a new normal.

Many of these images were made with the support of the National Geographic Society's COVID-19 Emergency Fund for Journalists , which launched in March 2020 and funded more than 324 projects in over 70 countries. These projects revealed the social, emotional, economic, educational, and equity issues threatening livelihoods all over the world.

Physician Gerald Foret dons a full-face respirator mask before seeing COVID-19 patients at Our Lady of the Angels Hospital in Bogalusa, Louisiana. The mask was donated to the hospital when it was running low on disposable N95 masks. In the early months of the pandemic, health-care systems faced severe shortages of personal protective equipment such as face masks and disposable gloves—putting front-line workers like Foret in further jeopardy.

A baby is born at the only maternity hospital in Dagestan, Russia. Located on the southernmost tip of Russia along the Caspian Sea, the Muslim-majority republic suffered a catastrophic surge of coronavirus deaths in the spring of 2020. The losses in Dagestan raised questions about whether the Russian government was obscuring the pandemic’s true death toll.

Alfonso Sellano, age 64, battles COVID-19 while his wife and a nurse tend to him in Espinar, Peru. As of March 2022, the country has the highest COVID-19 death rate in the world , which experts say can be attributed to the country’s weak health-care system and pervasive social inequalities that make it difficult for marginalized people to protect themselves from the virus. For instance, many had to continue commuting to work even during lockdown in order to provide for their families.

Hours of work in a protective mask leave a transient scar down the face of Yves Bouckaert, the chief intensive care unit physician at Tivoli Hospital in La Louvière, Belgium.

Ghislaine, a nurse in the geriatric ward at the same hospital, poses for a portrait with a tear running down her cheek. These photos were taken during the third wave of COVID-19, which triggered a new round of lockdowns in March 2021.

In Mons, Belgium, nursing colleagues take brief refuge in a shift break and each other’s company. Like medical facilities around the world, Belgian hospitals were initially overwhelmed by the rush of patients with a virulent new disease. These nurses, pulled from their standard duties, were thrown into full-time COVID-19 work—reinforcement troops for a long, exhausting battle.

COVID-19 has posed a particularly grave threat to Africa’s informal urban settlements —communities with high poverty rates where millions of people live in close quarters and often do not have access to clean water or toilets. In Nairobi, Kenya, residents of the Kibera informal settlement have their temperature checked by community health workers at a station set up by Shining Hope for Communities on March 26, 2020.

Home health-care worker Delores Jetton bathes her client Jean Robbins in a sunlit bedroom. “She is slow and prayerful as she bathes each person, washing with warm water and a touch that is so appreciated by these elders, who often face pain and fear at the end of life,” writes photographer Lynn Johnson. “As the bath progresses, one can see Robbins literally surrender to the touch.”

Even with the availability of effective vaccines, people over 65 remain at high risk of dying from COVID-19 . Many have been told to stay home rather than visit health clinics in person—causing a significant rise in demand for home health workers, who have often found themselves stretched to exhaustion in these past two years.

The mummified body of a COVID-19 victim lies on the patient’s deathbed awaiting a bodybag in Jakarta, Indonesia. It took two nurses about an hour to wrap the patient in plastic—a measure intended to keep the coronavirus from spreading. Indonesians were shocked when they saw this image, which humanizes the losses of COVID-19 and horror of death from the disease.

“It’s clear that the power of this image has galvanized discussion about coronavirus,” photographer Joshua Irwandi told National Geographic in July 2020 . “We have to recognize the sacrifice, and the risk, that the doctors and nurses are making.”

At the Rayer Bazar graveyard in Dhaka, Bangladesh, Farid conducts the janazah , an Islamic funeral prayer, for a COVID-19 victim and his relatives attending the burial. Bangladesh designated the cemetery as its official burial place for COVID-19 victims in April 2020.

Defying Peruvian government protocols, the Shipibo-Konibo have organized illegal mourning and funerals during the pandemic to honor their dead as their tradition dictates. At the funeral of Milena Canayo, who died in July 2020 with symptoms of COVID-19, her 9-year-old daughter lights a candle before taking refuge at home. Shipibo-Konibo people live in the Amazon rainforest of Peru, including in cities like Pucallpa where Milena's funeral was held. But she was not treated at the local hospital—Ronald Suarez, head of the organization Coshikox, says the health and welfare of Indigenous people is always the last to be considered.

Workers from a funeral home in Huancavelica wait until the end of a service to move a coffin into a grave at a city cemetery in April 2021. Much like the rest of the country, this city in central Peru has been hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic.

After keeping their social distance during the New York City funeral of Annie Lewis, family members draw together around the casket to say a final goodbye. In the United States, COVID-19 has been particularly devastating for low-income communities of color. As photographer Ruddy Roye told National Geographic , “The coronavirus pandemic has laid bare the divisions in our city.”

Relatives visit a loved one’s fresh grave at Rorotan Public Cemetery in Cilincing, North Jakarta, Indonesia, on July 21, 2021. The cemetery, which is dedicated to COVID-19 victims, opened in March. Even though it can hold up to 7,200 people, the cemetery filled up fast during the surge in cases caused by the Delta variant—which made Indonesia an epicenter of the pandemic. In response, Jakarta's government planned to add more land to the 25-hectare cemetery.

Elaine Fields, with her daughter Etana Fields-Purdy, stand close to her husband's gravesite at the Elmwood Cemetary in Detroit, on June 14, 2020. Eddie Fields, a retired General Motors plant worker, had died from COVID-19 complications in April. "It's hard because we haven't been able to mourn,” Elaine told photographer Wayne Lawrence . “We weren't able to be with him or have a funeral, so our mourning has been stunted."

Detroit journalist Biba Adams stands for a portrait at her home with daughter Maria Williams and granddaughter Gia Williams in Detroit on June 10, 2020. Adams lost her mother, grandmother, and aunt to the coronavirus. “To lose one’s mother is one thing,” Adams said in late July 2020 , when U.S. pandemic death totals were pushing past 150,000. “To lose her as one of 150,000 people is even more painful. I don’t want her to just be a number. She had dreams, things she still wanted to do. She was a person. And I am going to lift her name up.”

Family members place flowers atop the coffin of Eric Hallett, 76, just before a hearse carries his body to the crematorium in Crewkerne, England, on May 4, 2020. Pandemic safety protocols forced the crematorium to limit the number of mourners at each funeral. Instead, Hallett’s loved ones lined the streets to wave goodbye.

Sisters Dana Cobbs and Darcey Cobbs-Lomax lost both their father and paternal grandmother to COVID-19 in April 2020. Evelyn Cobbs was rushed to the hospital in ambulances just one day after her son Morgan—and the two died within a week of one another. Photographer Celeste Sloman took this virtual portrait of the sisters, who had to say goodbye to their loved ones from a distance due to the restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic.

White flags planted on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. represent each of the American lives lost to COVID-19. When the art installation opened in September 2021, the country had surpassed 670,000 deaths. For more than 30 hours, photographer and National Geographic Explorer Stephen Wilkes watched people move through the sea of white flags , capturing individuals as they grappled with the enormity of loss. Wilkes took 4,882 photographs of the exhibit, then blended them into a single composite image as part of his Day to Night series.

Kristiana Nicole Bell attends a candlelight vigil at St. Margaret of Scotland Catholic Church in Foley, Alabama, where she was baptized later that evening. The service, held the night before Easter Sunday, was led in both English and Spanish by Father Paul Zohgby. He decided about eight years ago that it was important to learn Spanish so he could welcome and minister to the community’s growing Latino immigrant population. Zohgby told photographer Natalie Keyssar that he was elated to rejoin his congregation in person after spending eight days in the hospital with severe COVID-19.

Quarantined for two weeks after traveling from Belgium to Shanghai, Justin Jin reads out his temperature to a medic on the other side of his closed hotel door. The picture was taken through the door’s peephole. Jin made the arduous journey to see his father, who just had surgery.

Photographer Ian Teh spends much of his working life on the road—so the pandemic allowed him to stay home with his wife, Chloe Lim, in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. “My partner and I are lucky that both our families are safe,” he says. “The pandemic has been an opportunity for us to connect with our loved ones, virtually.” He took this self-portrait of the couple in a favorite spot in their apartment, looking out on nearby houses and greenery. “It’s peaceful,” he says.

Heavy rain falls on Buenos Aires, Argentina, on April 27, 2020. Argentina entered a full lockdown on March 20 that endured more than four months. Feeling trapped, and still recovering from a miscarriage, photographer Sarah Pabst picked up her camera to document her pandemic experiences. The result: Morning Song , a project that uses photography to explore motherhood, love, and loss, and our connection with nature.

Greta Tanini and Cristoforo Lippi decided to take advantage of Italy's quarantine lockdown—to regard their enforced time together as a new exploration of their relationship. They divided up domestic tasks—including shopping, cleaning, and tidying up—and limited their social interaction to chatting with neighbors at a safe distance so as not to spread the virus.

The Apollo Theater has been a Harlem landmark since the 1930s, when it helped propel music genres such as jazz, R & B, and the blues into the American mainstream. The Apollo was one of New York City’s many historic entertainment venues that closed in early 2020 to stem the spread of COVID-19. It remained shuttered for a year and a half—and finally returned, to much excitement, in August 2021.

In spring 2020, sculptor Antonio Canova's The Three Graces (1812-1817) stand alone in the rotunda of Milan’s Galleria d’Italia. COVID-19 lockdowns forced museums across Europe to close their door for months— sparking fears that the loss of revenue might keep them permanently closed. By June, however, some museums began to reopen with limited numbers of visitors, temperature checks, and socially distant experiences.

Photographer Mariceu Erthal took this self-portrait in July 2020 during her first visit to the sea after being confined at home by COVID-19 lockdowns. She says the experience “brought me peace of mind and allowed me to observe the sadness and anxieties I had inside.”

Photographer Bethany Mollenkof found out she was pregnant three months before COVID-19 shut down swaths of the United States. She began to document her own experiences during quarantine in Los Angeles—from her first ultrasound, which her husband had to watch from the parking lot over FaceTime, to childbirth. Although Mollenkof had hoped for a natural birth, she decided to deliver in a hospital in case of complications—which proved the right choice. After her water broke, her contractions did not start, and ultimately labor was induced to keep the baby safe.

“I thought about my friends, my community, and what it would feel like to become new parents in isolation—to not have people around us to help, people who years later could tell our daughter that they’d held her when she was a few days old,” Mollenkof wrote in a photo essay for National Geographic . “But I also thought about women throughout history, women who have survived wars, pandemics, miscarriages. Their resilience guided me.”

Exhausted after giving birth to her daughter, Suzette, Kim Bonsignore lies in the birthing pool in her living room on April 20, 2020, in New York City. Instead of having her baby in the hospital as planned, the Bonsignores decided to have their second child at home when they learned that family members would not be allowed in the delivery room because of COVID-19 restrictions.

In Moscow, a nurse wearing a hazmat suit holds a bouquet of flowers for at Hospital No. 52 on March 9, 2020—or Victory Day. Russia’s most important national holiday commemorates the surrender of Nazi Germany in 1945. Although celebrations were more subdued because of the pandemic, the hospital arranged a small tribute for veterans and their families under treatment.

Photographer Tamara Merino took this self-portrait with her son Ikal on the first day of total isolation in Santiago, Chile. “The confinement feels stronger and more overwhelming when someone imposes it on you,” she wrote. “When we have freedom over our actions, and we decide to stay home, we still feel free. Not anymore.”

Image of customers seen through a thermal scanner at the entrance of a supermarket in Ushuaia, the capital of Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. The vast majority of food on the island is imported, and shopping is centralized in big supermarket chains—creating a challenge for social distancing. During lockdown, thermal scanners were placed in the supermarkets to take the temperature of incoming customers. Customers with elevated temperatures were sent home.

Girls form a socially distant queue to take a shower at a facility in Kibera, an informal settlement in Nairobi, Kenya. Most residents in the community do not have access to indoor plumbing, so a local organization provided free water to help prevent the spread of coronavirus by helping people maintain their personal hygiene.

An Istanbul city employee disinfects the streets of Beyoglu on April 14, 2020. Typically bustling with tourists intent on sampling its historic winehouses, museums, nightclubs and shops, the neighborhood fell quiet at the start of the pandemic. Many cities initially tried to curb the spread of the coronavirus by spraying their walkways with disinfectant—a practice that the World Health Organization ultimately recommended against , as the chemicals were likely to harm people’s health.

Migrants climb onto a truck which will take them toward their village on the outskirts of Lucknow, India, on May 6, 2020. When the Indian government announced a nationwide lockdown on March 24, it requested that people stay put, wherever they were. But that created a shortage of food for the huge migrant population in cities—so, after much deliberation and implementation of new public safety measures, state governments coordinated efforts to transport the migrants to their homes on special trains.

Students resume in-person classes at Elementary School No. 1 in Jakarta, Indonesia. More than 600 schools across the city reopened on a limited basis in fall 2021, offering face-to-face classes three days a week with strict health protocols in place. Schools also restricted the number of students who could attend in person, with half of each class still learning from home via video conference. Nadiem Makarim, the Indonesian minister of education, pushed for a return to classrooms, telling parliament that COVID-19 lockdowns caused “learning losses that have permanent impacts.”

In a Pétion-Ville high school, a student distributes handmade masks to his classmates before classes begin. The pandemic disrupted education for children everywhere—but the crisis was particularly dire in Haiti, where students have also suffered gaps in their education as a result of social unrest and natural disasters. The Caribbean nation reopened many of its schools in August 2020 with public health measures like masking in place.

Aspiring insurance agents sit for their qualification exams at desks spread apart on a soccer field in South Korea on April 25, 2020. The Korea Life Insurance Association and the General Insurance Association of Korea were among the many public and private institutions that introduced socially distanced exams during the pandemic. It was a very windy day, but more than 18,000 people across Korea took the insurance agent exam—happy that they had resumed after a hiatus of more than two months.

Eighteen-year-old Stephen Onyango (center) teaches his brothers Collins and Gavan while their sister Genevieve Akinyi watches at their home in Kibera. They hadn't been to class since the Kenyan government closed all schools in the country in mid-March to curb the spread of COVID-19. Stephen told photographer Brian Otieno that his teacher suggested an app he could use to teach his siblings. “It's my responsibility to ensure that my brothers are at home studying now that coronavirus is here with us and we don't know when this will end,” he said. Kenya reopened schools in January 2021, even as the pandemic continued to spread.

Members of the Phi Beta Sigma fraternity gather for an impromptu step dance after Howard University's commencement ceremony in Washington, D.C., on May 8, 2021. Only undergraduate students were allowed to attend the outdoor, in-person ceremony held at the university’s stadium. Friends and family scattered around outside of the stadium instead.

You May Also Like

COVID-19 has tested us. Will we be ready for the next pandemic?

COVID-19 can ruin your sleep in many different ways—here's why

Why does COVID-19 cause brain fog? Scientists may finally have an answer.

“As I was bouncing around campus, I started to think about how much the students had been through the past year and how this particular moment must feel for them,” said photographer Jared Soares. “To be able to witness the students' jubilation was a huge privilege, and even more meaningful based on the circumstances that we as a community had to endure the past year and a half.”

Seoulites lounge on picnic mats in the grass at Ttukseom Hangang Park on a late summer weekend in 2021. Located under ring-shaped entry and exit ramps leading to a bridge and an expressway, the park is a popular gathering spot for young and old alike.

Nadia, one of the hosts of the talent quest TV show Afghan Star , interviews masked young women at a taping on February 18, 2021. As the Taliban moved to retake national control, Afghan Star ’s cast and crew came under serious threat—judges and participants had to stay at a safe house with armed security guards and blast walls until the end of the season. Kabul fell to the Taliban six months after this photograph was taken, leaving an uncertain future for Afghan women .

Berlin partygoers share a moment In a hallway of the Ritter Butzke, a venerable electronic music clubs, on August 28, 2021. Recently government-designated a German cultural institution, the Ritter Butzke—like other clubs with open air spaces— was approved last summer for public reopening . Some pandemic rules still apply: signs at the club urge patrons to wear masks and refrain from drinking on the dance floor.

Members of the Orquesta Sinfónica Gran Mariscal de Ayacucho play music from their new album, Sinfonía Desordenada (Disorderly Symphony), during an open-air performance on November 12, 2021 in Caracas, Venezuela. The album was recorded during the pandemic lockdown by 75 musicians who blended elements of classical music with Afro-Caribbean rhythms.

A boy flies his kite during lockdown in Amman, Jordan, in April 2020. For a few days in March, the government had imposed even tighter restrictions—shutting down nearly everything and instituting a 24-hour curfew backed up by tanks and army trucks, with no exceptions even to get food and medicine.

Amman is built on hills, and from his kitchen, photographer Moises Saman could hear the echoes of citywide sirens, the kind used for air raid warnings. He stayed inside with his family until the curfews began to ease. Then he went to find the places where refugees live, including the neighborhood where this photograph was taken. Despite fears that their crowded settlements and neighborhoods would lead to uncontainable spread of COVID-19, Jordan's strict lockdown kept the pandemic at bay during its early months. But as lockdown measures eased, cases began to surge by the fall —a warning to all countries to remain vigilant.

Related Topics

- CORONAVIRUS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

Is the COVID-19 pandemic over?

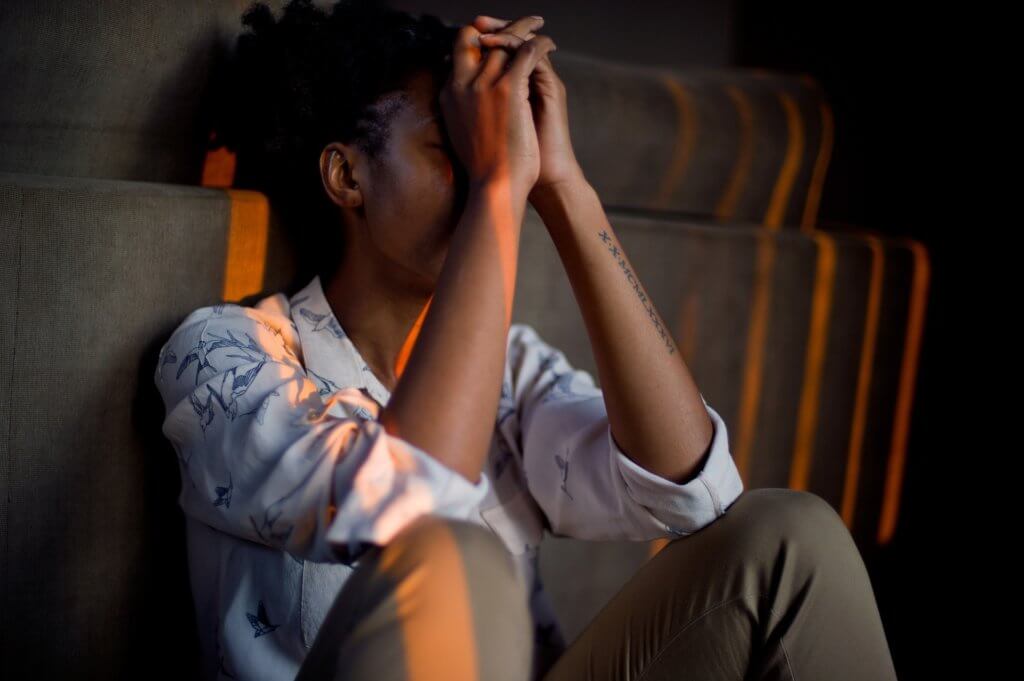

Could COVID-19 trigger depression?

How multiple COVID-19 infections can harm the body

COVID-19 took a unique toll on undocumented immigrants

One of the best tools for predicting COVID-19 outbreaks? Sewage.

- Perpetual Planet

- Environment

History & Culture

- History Magazine

- History & Culture

- Race in America

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Paid Content

- Adventures Everywhere

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Together Apart: A COVID-19 photo essay by Cody Duty

Since the pandemic arrived in Houston, we have adapted to a new normal.

We have quarantined at home to keep ourselves and others safe.

We have visited drive-thru COVID-19 testing sites.

We have gone to work on the front lines of the pandemic.

We have celebrated the birthdays of loved ones with car parades.

We have submitted to thermal scanners that take our temperatures as we enter medical buildings.

We have said goodbye, temporarily, to our favorite restaurants and venues, until it is safe for us congregate again in large groups.

Texas Medical Center photojournalist Cody Duty has captured pandemic life with images that wring warmth and beauty from this devastating period in history.

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: Looking for the latest on the CORONAVIRUS? Read our daily updates HERE . ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Recommended News

COVID-19 coverage: Stories by the TMC News staff

“How are you doing emotionally?”

Coronavirus: A Texas Medical Center continuing update

Friday essay: COVID in ten photos

Lecturer of art history, Griffith University

Disclosure statement

Chari Larsson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Griffith University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Our memories are malleable, they change over time. Memories can, however, crystallise through repetition. One of the most interesting things about memory is it is distinctly visual. With time, dramatic events reduce to a series of still images, which psychologists call “ flashbulb memories ”. Retrieving them is akin to rifling through a visual database.

The history of war photography offers many powerful examples of how memory and photographic images work together to symbolise entire events.

Consider one of the most famous news images from the Vietnam War, Nick Ut’s image of nine-year old Phan Thị Kim Phúc , badly burned and running down the road after a napalm attack. Or the Abu Ghraib photographs of prisoner abuse in the American military .

Viruses are distinctly anti-spectacular. They are invisible. We can, nevertheless, capture their impact. In 1990, at the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis in America, Life magazine published an image of a dying man, David Kirby, surrounded by his anguished family. Therese Frare’s photograph was credited for humanising HIV and raising much needed awareness.

We are still in the early days of this pandemic. It is not too premature, however, to start writing its history through images. Here are some of the photos that captured the impact of COVID-19 in Australia.

The Ruby Princess stranded

Networks of globalisation, such as the tourism industry, helped spread the virus between countries. This image was taken from the Waverley Cemetery, in Sydney’s east in early April. Tightly framed by gravestones, the Ruby Princess cruise ship intersects with the strong blue of the horizon.

Sydney is reimagined as an ancient burial site, a necropolis, a city of the dead.

It is not unusual for cruise liners to sit off the city’s coast. This photograph is chilling, however because of the large cluster of COVID-19 infections linked to this ship. When Joel Carrett took this photograph, passengers had already disembarked, and health authorities were scrambling to control community transmission.

Sometimes, images are powerful because they have long historical links. Ships have historically been carriers of disease, treated suspiciously by coastal towns and ports.

During the height of the Black Death in the 14th century, the citizens of Venice realised infected persons were on ships and the best defence was isolation. The modern term quarantine is derived from the Italian quaranta giorni , the 40 days vessels were kept offshore.

Read more: Fleas to flu to coronavirus: how 'death ships' spread disease through the ages

Bondi Beach crowds

We were still learning how to socially distance in March and adhere to the government’s advice to “stay at home” when images of beach-lovers making the most of Sydney’s glorious Indian summer went viral on social media.

The beach occupies a sacred place in our national psyche: a place of leisure and of freedom. What was ominous about this image, however, was the crowd’s ability to render a usually benign activity into a menacing threat.

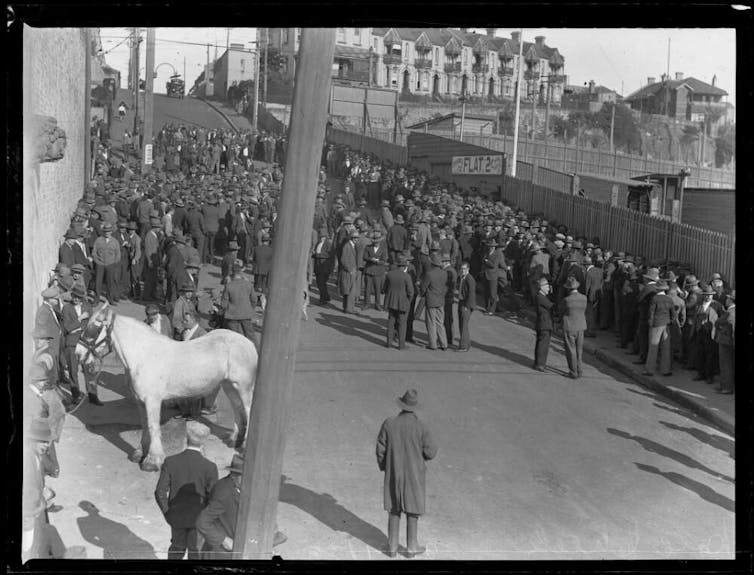

Centrelink queue, Sydney

The most visceral signs of an economy in free fall came in late March with long queues of people waiting outside Centrelink offices across the country. As the myGov website collapsed under the strain, people were forced onto the streets, echoing scenes from Depression-era unemployment .

This photograph is cropped, leaving the viewer’s eye to run down the line of umbrellas, before pausing to rest on the woman in the yellow jumper and clear poncho. Her body language speaks of exasperation and frustration.

The image is taken at street level, a powerful levelling effect: the spectator joins the queue.

A very different strategy is at play in this 1932 image of the dole queue at Sydney’s Harold Park. Here, the photographer captures the group from an elevated position. This creates the effect of “hovering” above the queue like a bird. The spectator remains separate and apart from the crowd. The telegraph pole reinforces this division.

Panic buying, Coles supermarket

In March, supermarket shelves were emptying as Australians started panic buying essentials such as toilet paper, pasta and rice.

The idea of an image being active and capable of influencing our behaviour is underscored by photographs of empty supermarket shelves. Images such as these helped fuel further panic buying, reinforcing the misconception we were running out of food.

Read more: Disagreeability, neuroticism and stress: what drives panic buying during the COVID-19 pandemic

In this image, the bare shelves retreat, drawing the spectator’s eye diagonally backwards towards the far wall. People wait patiently while maintaining a careful distance from each other. The spectator’s eye returns to rest with the central seated figure. His posture indicates fatigued resignation.

Panic buying is not unprecedented in Australia. During World War II, food and clothing rationing was introduced to control consumption and ensure equitable distribution of resources.

This archival image shows people in Melbourne stocking up on meat in 1944 in advance of impending rationing. The small enclosed space feels claustrophobic as shoppers crowd in, waiting to be served.

Public housing towers lockdown, Melbourne

Physical distancing is a luxury not everyone can afford. COVID-19 thrives in dense living spaces, making visible class and race divisions. The early July lockdown of nine public housing towers in Melbourne was a blunt reminder the pandemic embeds itself in communities that house some of our most vulnerable. The towers were presented as crime scenes, sealed off with police tape.

David Crosling’s photograph is striking because of its distinct lack of people. The police tape occupies the immediate foreground, while the towers rise threateningly in the distance.

On closer inspection, a solitary figure can be detected in the left middle ground. The pathway leads the viewer’s eye straight to a COVID-19 testing tent. The site is registered as a crime scene; a barrier is placed between the spectator and the towers.

The absence of people became a foreboding sign of what was to come: Melbourne’s “hard lockdown”.

Empty Melbourne CBD

The atmosphere is bleak and unnerving. An empty city is a lonely city. A city needs its people. Today, the usually bustling alleyways in Melbourne’s CBD lie mute, waiting for the stage four restrictions to pass.

An eerie quality emerges when architectural landscapes are silent and empty. Usually an index of vitality, the street art in the foreground of the image is transformed, becoming a trace or relic of former human activity.

Images of Melbourne devoid of its people resonate with Eugène Atget ’s photographs of the “old Paris”. Working at the turn of the 20th century, Atget focused on documenting the old, disappearing streets of Paris under pressure to modernise.

Writing in the 1930s, German philosopher and essayist Walter Benjamin observed Atget’s images were like deserted crime scenes “photographed for the purpose of establishing evidence”.

They demand a specific kind of approach; free-floating contemplation is not appropriate to them. They stir the viewer; he feels challenged by them in a new way.

A crime scene asks more from its spectator than just viewing passively. Instead, the spectator becomes a witness or bystander.

Read more: Friday essay: the uncanny melancholy of empty photographs in the time of coronavirus

Face mask and face shield

As the virus asserts its grip, the face mask has now become a symbol of the next phase of our collective efforts to suppress COVID-19.

The practice of wearing a mask in the times of disease and pandemics has a long history. The medieval Latin word masca ominously means “spectre or nightmare”.

In the 17th century, plague doctors were recognised by their distinctive beak-like masks when attending sick patients, protecting the doctors from “bad air” and preventing contagion.

Centuries on, the basic premise of creating a barrier between the patient and the health workforce remains remarkably the same.

Temporary memorial, St Basil’s Homes for the Aged

Australia has avoided the rampant transmission and devastating loss of life seen in parts of Europe, the USA and Brazil. Our mortality rates, nevertheless, are steadily creeping upwards as the pandemic spreads, particularly in aged care facilities.

We haven’t seen images like the overflowing intensive care wards in Italy , or the drone footage of New York’s mass graves . For privacy and ethical reasons, photographs from inside aged care homes and intensive care wards are rare. Our understanding of the deaths is thus shaped by personal photographs of COVID-19’s victims released by their families or photos of the exteriors of aged care homes.

In late July, temporary memorials were set up outside one of the hardest hit facilities, St Basil’s Home for the Aged. Here, fences create a barrier between the photographer and the buildings. For the viewer, the physicality of lockdown is reinforced.

Healthcare workers in PPE

Frontline health workers in full personal protective equipment have largely become the face of COVID-19.

Widespread testing is proving crucial to controlling the pandemic. Here, healthcare workers are captured working at a drive through clinic. The camera’s lens is focused on the middle ground, with the staff rendered crisply in silhouette. Healthcare workers are our first and last line of defence against COVID-19.

There is unlikely to be one single photograph that comes to symbolise the pandemic. But it is possible to start reflecting on images that have been instrumental in shaping policy and debate.

These images serve as a chronicle of the disorientating early days of COVID-19 in Australia.

- Photography

- Coronavirus

- Friday essay

- Ruby Princess

Postdoctoral Research Fellowship

Health Safety and Wellbeing Advisor

Social Media Producer

Dean (Head of School), Indigenous Knowledges

Senior Research Fellow - Curtin Institute for Energy Transition (CIET)

About the Project

Every person on every continent has been affected by COVID-19. But as the world reels from the devastation caused by this unprecedented crisis, how much is known and documented about the grave and far-reaching repercussions on the lives and livelihoods of millions of people?

COVID-19: The Bigger Picture uses the power of photography and journalism to bring to the world’s attention stories of how those most vulnerable to the pandemic are being impacted – stories that are often untold or overlooked.

Photo Competition

Could your picture tell a thousand words? Then the camera is in your hands. Our photo competition is open to anyone with a passion for turning the lens on the real lives behind the headlines, and an ability to capture the most powerful images of the pandemic’s impact on everyday people.

Photo Essays

When everyone is consumed by just one conversation, some voices struggle to be heard. Often these belong to the most vulnerable people in the world, hit hardest by the severity of the pandemic. Our world-class journalists have expertise in telling their stories.

The United States has been decimated by the crisis. We’ll be bringing you a series of five photo essays over the next three months, each shining a spotlight on different themes and different states.

Sign up to be notified when the next photo essay is released.

Florida’s care workers face daily risks as dream retirements turn into nightmares.

Black businesses in new orleans fear coronavirus blow will be ‘mightier than katrina’..

North Carolina

Child care workers in North Carolina battle new set of rules to stay safe as parents go back to work.

Coronavirus slams brakes on lives of california’s hotel and theme park workers as tourism dives..

Washington DC

The gig workers struggling to be heard in the U.S. capital amid COVID-19.

- PHOTO COMPETITION

- PHOTO ESSAYS

- Signs of the Times: Public Displays at the Height of the COVID-19 Pandemic

From politics and the pandemic to Halloween and graduation, 2020 was notable for its proliferation of citizen signage. This photo essay provides a time capsule of the COVID-19 era in West Philadelphia.

By Kelly Diaz

Like so many people did during those days of fear and uncertainty that marked the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, I brought home a puppy. A “cavachon” (Cavalier King Charles Spaniel and Bichon Frise mix), Matilda (“Tillie”) was eight weeks old when I got her in May 2020, and while she was potty training, she needed up to 10 walks a day.

It was frustrating for me to spend so much time of the day away from my computer, taking breaks that the diligent graduate student in me did not think I had earned.

But I took comfort in Tanya Behrisch’s “Slow” philosophy . In reference to the time she spent cooking for herself and loved ones, she explains:

“Rather than viewing those hours in neoliberal time as ‘lost hours’ I want to shift to a Slow appreciation of ‘gained hours.’ [...] Care work requires Slowing down, taking time to notice what should be done, for whom, when, and how. The Slow movement invites me to explore this relational process through research, writing, and embodied practice of cooking for others (p. 3).”

With this in mind, I realized my puppy would never be so young and impressionable again. Each day she got older, bigger, and more independent. Work would always be there needing my attention, but my precious fur baby would not.

Throughout some of the hardest and most stressful months of my life, I was cheered up by the fresh air, Tillie’s adorable sidewalk strut, and the messages my neighbors displayed in the windows, balconies, porches, and yards of residential buildings and storefronts. I began to consider the visual messaging on graffiti, memorial displays, flyers, and other citizen signage.

Between May and December of 2020, I took photographs of these displays on my iPhone as I walked Tillie through the streets of West Philadelphia, in particular the University City and Spruce Hill neighborhoods. You will find a gallery of these images below.

A Constellation of Issues

In a Slate.com article about the trend of posting signs in the early months of the pandemic, journalist Henry Grabar wrote, “Chicago is empty of people but full of signs [...] Every city is like this now, as if our protective masks stifled the ability to speak and left us to communicate only in writing.”

As those who lived through 2020 recall, there was no shortage of fodder for signage.

The pandemic coincided with a presidential election, which exponentially increased the degree to which people were displaying a national identity and concern.

Another significant percentage of the signs expressed “thank you” messages for essential workers who were continuing to leave their homes and risk COVID exposure to keep the community running. These were, at times, bright and uplifting artwork to demonstrate one’s positive outlook in the midst of crisis and tragedy.

As protests against racial injustice and anti-Blackness in the United States grew, many residents in my neighborhood displayed either homemade or commercially manufactured Black Lives Matter signs to demonstrate an intolerance for violence and discrimination against Black Americans.

Performing One’s Values

Signs are both display and performance, a way that people articulate their definition of self as someone who takes public health seriously and is community-oriented.

Just as many of the themes overlapped, so too did the media. Images that were made by hand with markers or crayons and hung in windows may have also been photographed and uploaded to Instagram or Facebook. Similarly, the immediate intended audience might be passersby, but it could also be one’s own social media followers or the extended networks of anyone who walks by and takes a picture as I did, and now share with you in the gallery below.

As I took these photos, I thought about Erving Goffman’s 1959 book, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life . It helped me to see the signs as a means of performing identity, gratitude, care, and allyship. This is not to say that the displays are not genuine, but rather that they are calculated and intentional attempts to put forward into the world an image of oneself through a visual. Goffman writes:

“The individual may attempt to induce the audience to judge him and the situation in a particular way, and he may seek this judgment as an ultimate end in itself, and yet he may not completely believe that he deserves the valuation of self which he asks for or that the impression or reality which he fosters is valid (p. 21).”

Indeed, I saw many signs that seem to have been made and displayed in order to have an audience “judge” (in a positive sense) the person or household sharing that message or “performance.” I imagine that some of my neighbors hoped to be viewed by passersby as anti-racists or feminists or Biden/Harris supporters.

As Goffman suggests, however, many might have found that even after creating the display of care or identity they still felt guilty or insecure about their place in our deeply flawed society. This was certainly true of myself.

What Goes Unseen

Performative allyship has been critiqued widely as a phenomenon wherein people seek attention for their support for justice without doing actual justice work. While I recognize this problem, I can also see merits to the displays of allyship in this context. After all, performing allyship is not in itself a problem, if accompanied by action.

As a new member of the community, it was comforting and affirming to see my neighbors’ values on display through this signage. While I recognized the many problematic ways that people have engaged in virtue signaling, in this case, I wanted my neighbors to signal their virtues to me. If I wanted to know, for example, that it was safe to wear my Pride shirt around the neighborhood, I could find my answer in many of the signs displayed by my neighbors.

I thought about the labor and care people took to make homemade signs, though this does not necessarily point to further social action. I also thought about how it would be easy to judge someone for simply displaying a commercially made sign, though at times those signs come as a result of a donation to a justice organization. In this case, people displaying them have “put their money where their mouth is” and directly supported the cause.

Assigning motivation was, of course, impossible. In these times of social distancing, I was unable to pair the displays of allyship through signage with discussions with the creators about their social justice work. It was also not clear which signs came from allies and which came from people directly impacted.

Politics on Display

While lawn and window signs are common every election season, I do wonder if there was an increase in signage to compensate for the loss of other forms of political identity and candidate support during physical distancing. For example, people who usually wear campaign t-shirts, pins, and hats might have instead opted for a sign that they could display from the safety of their home, while still reaching an audience.

The signs were also a reflection of our local political leanings. The prevalence of Black Lives Matter, Biden/Harris signs, and COVID-19 safety signs was notable in the absence of signage in support of police, the Trump/Pence administration, or claims that COVID-19 was a hoax to be ignored.

The few times I left the community this summer I found myself in areas with large numbers of Blue Lives Matter products, signs demanding that the government reopen restaurants and shops, and Trump 2020 flags.

The difference in my degree of safety and comfort as a queer woman of color was palpable in those communities versus in my own, and I was proud to see the intolerance of racism, homophobia, and other forms of discrimination on display amongst West Philadelphia residents — acknowledging, of course, that these generalizations do not apply to all residents.

Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times

Another thing that caught my attention were the contrasts in subject matter. While people were mourning the loss of lives and experiences due to COVID-19 and white supremacy, people were also celebrating graduations and holidays. Once mundane Halloween decorations such as tombstones and skeletons took on a new meaning for me when I encountered them during a period of mass death.

While people were calling for police abolition, they were also expressing gratitude for postal and sanitation workers who had been working through frustrating budget cuts and high COVID-19 risk.

The images also demonstrated the ways in which mundane and regular tasks persisted even throughout the COVID crisis. People continued to grab coffee at the local café, get their flu shots, and wash their clothes at the laundromat, even as the logistics of these tasks changed greatly.

Although many photographs below captured similar displays, no two photos are identical. Even when signs were exactly the same in content, they varied in terms of placement, materiality, size, and many other factors.

This collection is useful even in 2020 as a way to understand West Philadelphia residents in 2020, and it will likely be even more valuable in future years as a time capsule. While I took these photos without asking for permission, I hope that by sharing them, I am honoring the West Philadelphia community that gave me a warm welcome and offered me a home during some of the most difficult months of my life.

Kelly Diaz is a doctoral candidate at the Annenberg School for Communication.

West Philadelphia During COVID

Use the arrows to scroll through photos taken by Kelly Diaz on her iPhone between May and December of 2020.

Photo Essay Captures How COVID-19 Has Transformed BU

A darkened hallway in the College of Arts & Sciences, March 18. BU buildings have been largely vacant since the University moved all teaching and learning remotely on March 16 in response to the coronavirus pandemic. Photo by Cydney Scott

Images document the subtle—and not so subtle—ways the pandemic has altered campus

Bu today staff.

From the moment the University announced that starting March 16 it was moving to remote teaching and learning for the rest of the spring semester, then shuttered residences for most students as of March 22, BU campuses took on a startlingly different look, transformed overnight from bustling metropolises to a series of largely empty interior and exterior landscapes.

Staff photojournalists Cydney Scott and Jackie Ricciardi have continued to photograph the campuses since the pandemic caused the city of Boston to limit the normal operations of businesses, even as most students have returned home and most faculty and staff are working remotely.

“As a photographer for BU Today, the biggest danger I usually face at work is whether or not I’ll squeeze into a spot on the BU shuttle on my way to an assignment on a rainy day,” Scott says. “Photographing Comm Ave during the midst of a pandemic brings risks of a different, more frightening order.” The two maintain a safe social distance when shooting their subjects—which brings new challenges. “Where I would typically move around during a shoot, being a ‘fly on the wall,’ my movement now is largely limited,” she says.

“Photographing during the pandemic has been a struggle for me,” says Ricciardi. “As a photojournalist, my goal is to capture human connection, and I wonder how I can do that successfully when the streets are empty and we’re told we must stay away from people…yet one of the most significant events in history is happening in my lifetime and it’s my responsibility to try and capture that.”

Their images will serve to chronicle this moment in history for years to come.

Meredith Siegel (left) and Rachel Reiser, both Questrom assistant deans, practice social distancing while prepping for a “dean’s huddle” meeting via Zoom on March 16. Photo by Cydney Scott

A sign posted outside the College of Communication student lounge March 16. Photo by Cydney Scott

Bruno Rubio, a College of Arts & Sciences master lecturer in chemistry, holding remote office hours in a Metcalf Science Center lecture hall March 17. “I was old-school with my teaching,” says Rubio, “My clinging to traditional methods of learning and teaching? I’m paying for it now!” In fact, he mastered Zoom quickly and was able to assist the eight students who needed help that day. Photo by Cydney Scott

An eerily empty FitRec basketball court on March 17. FitRec closed that day. Photo by Cydney Scott

Paradise Rock Club assistant production manager Will Powell posting an encouraging message on the club’s marquee March 17. The Paradise is closed indefinitely because of the coronavirus pandemic, like all the commonwealth’s bars, restaurants, and entertainment spots. Photo by Cydney Scott

COM staff members on video screens in the school’s Zimmerman Social Media Activation Center during a Zoom meeting March 17. Photo by Cydney Scott

BU custodian Grace Araujo at work at StuVi I on March 17. BU’s custodial staff continues to clean and maintain BU’s 300 buildings during the pandemic. Photo by Jackie Ricciardi

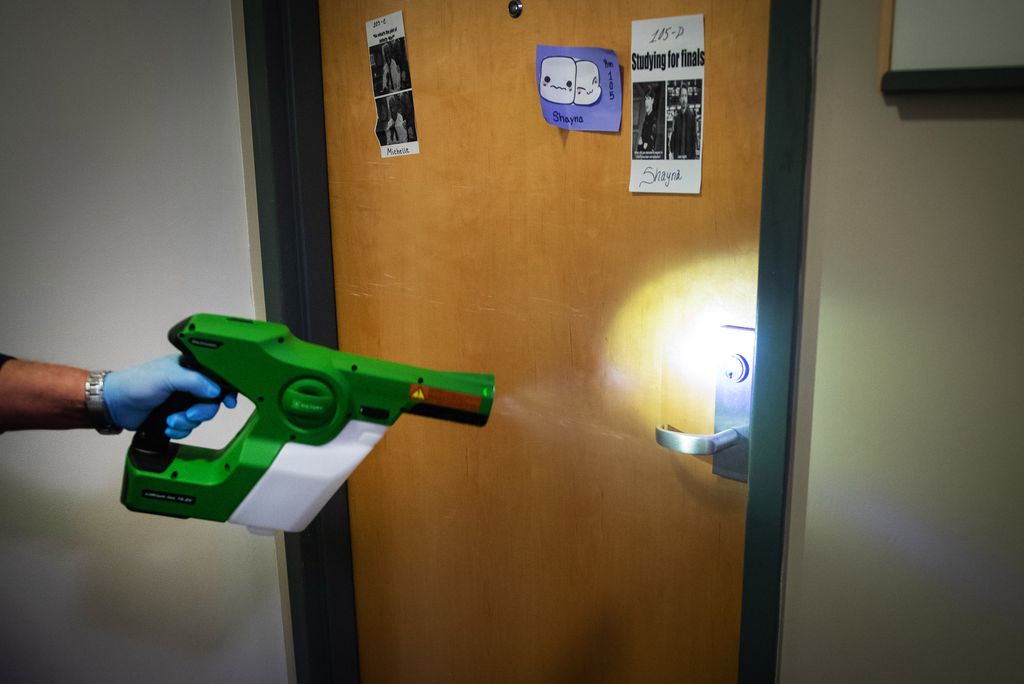

Victory Innovations battery-operated electrostatic spray guns are prized by custodial workers for their deep cleaning ability. BU invested in about 20 of the spray guns, which are in such high demand now that they are almost impossible to get. Photo by Jackie Ricciardi

The first day of remote learning: a lone student studying at Mugar Memorial Library on March 16. The library is now closed to students, but staff continue to provide support and services remotely. Photo by Jackie Ricciardi

Entering the George Sherman Union on March 16 (left) and finding it almost empty on March 18 (right) must have been surreal experiences. Fewer than 450 students remain in BU housing at present. Photos by Jackie Ricciardi (left) and Cydney Scott (right)

Rev. Dr. Robert Allan Hill, dean of Marsh Chapel, on his way to the chapel’s first virtual Sunday service on March 22. The eight choral scholars on the altar are six feet apart during the service. Photos by Cydney Scott

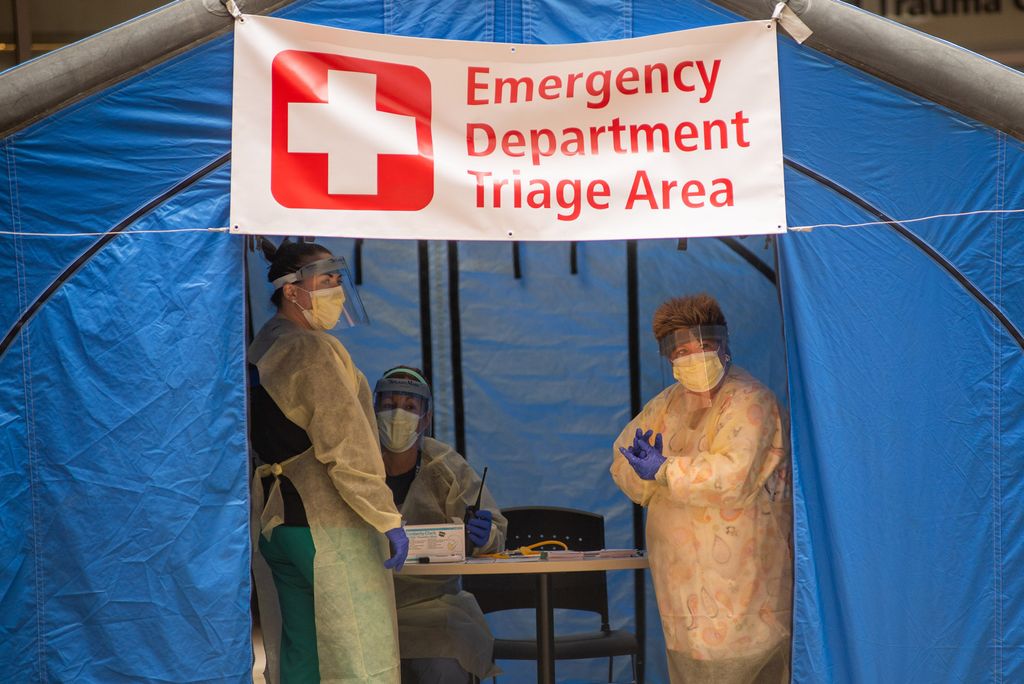

A triage tent for intake of potential coronavirus patients set up outside Boston Medical Center March 20. BMC nurses Marisa McIntyre (left) and Maureen Shanahan-Frappie are among staff there who assess patients’ symptoms and determine whether they should be sent to BMC’s influenza-like illness clinic (ILI) for moderate symptoms or to the Emergency Department for more serious conditions. COVID-19 testing is done at both. Photo by Cydney Scott

Except for exceptional cases, most students living on campus had to be out of their rooms by March 22. Xing Hu (CAS’22) (left) waits with Abin George (ENG’23) outside Claflin Hall to be picked up March 20. Photo by Cydney Scott

Goodbyes: Northeastern freshman Nadhur Prashant (left) with his girlfriend, Anindita Lal (CAS’23), on West Campus March 20. Lal was returning home to Acton, Mass., and Prashant was leaving Boston to go home to India. Photo by Cydney Scott

Bicycles and strewn moving carts in the courtyard between 722 and 726 Comm Ave on March 25, after dorms were shuttered. Photo by Cydney Scott

Millyan Phillips of Piece by Piece Moving Company empties a room on the Fenway Campus’ Riverway House March 27. Students who had left belongings behind when they went on spring break were able to use an app to specify items they wanted stored, saved, or thrown out. Photo by Cydney Scott

An abandoned Fenway Campus Center, bereft of its usual throngs of students, on April 15. The 150 Riverway building houses the campus dining hall and common student spaces as well as student residences. Photo by Jackie Ricciardi

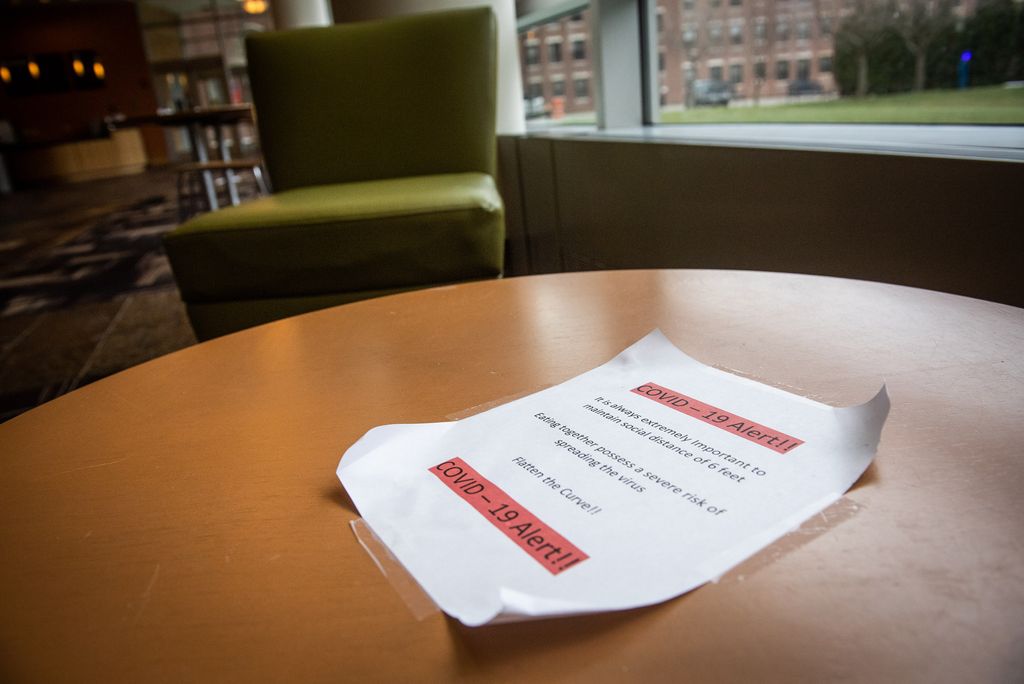

A flyer reminding residents to maintain social distance guidelines, left on a Fenway Campus Center table. Photo by Jackie Ricciardi

Left photo: Quarantine kits lined up in the GSU Ballroom on April 15. The kits, containing two weeks’ worth of cleaning supplies, paper goods, pillows, linens, and nonperishable snacks and meals, were available to students quarantined on campus because of exposure to COVID-19. Right photo: Jennifer Skikas (left), GSU catering sales manager, and Joann Flores, catering manager for Questrom, load up some of the items to be delivered to empty quarantine rooms across campus on April 21. Photos by Cydney Scott

Lead custodian Carlos Carreiro (left) and custodian Andres Lopez deliver paper goods to empty quarantine rooms at 580 Comm Ave April 21. The University reserved approximately 50 rooms across campus for students who needed to be quarantined during the pandemic. Photo by Cydney Scott

Explore Related Topics:

- Charles River Campus

- Coronavirus

- Photography

- Share this story

- 7 Comments Add

BU Today staff Profile

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.

There are 7 comments on Photo Essay Captures How COVID-19 Has Transformed BU

Jackie and Cydney, wonderful yet weird campus shots. Thank you for being on site capturing this for us.

Thank you, Cydney and Jackie, for these images that capture so many elements of BU during this difficult time of grieving for the world, and caring for each other. You make us proud, even prouder, of BU people!

Thanks for Cydney and Jackie’s excellenct and memorable work with these capturing photos! my son is still in BU for his master degree study and will finish his study by May. Our family apprecaites all the work and effort by BU during this special and difficult period. We are proud my son is a student of BU!

Wow! Great images. Your photos tell a very moving story. You also managed to capture an image of my son studying in the library. He is the lone student at the Mugar Memorial Library. Can you please let me know how I can buy a copy of that image? Thank you.

Great work. Is there a way that I can get a copy Of one of the images. My son is in that photo.

Shoot me an email Dina and I’ll see what we can do. Cydney [email protected]

Fantastic photography & story, thank you for sharing! Our son never had the chance to return to BU after spring break, so to see what BU looks like now is very moving. Our family is grateful to all the BU staff, faculty & students and look forward to the day we can visit Boston again!

Post a comment. Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Latest from BU Today

Court upholds gun ban for those accused of domestic violence; bu law expert explains, best summer study spots on bu’s campus, to do today: tour fenway park, five tips for navigating college without regrets, pov: what all that change americans leave behind at airport security checkpoints tells us, want to experience a true new england summer, wheelock lecturer works inside and outside system to fight for education equality, choosing between an airbnb and a hotel this summer here are some things to consider, lessons from an interim president: kenneth freeman reflects on a historic year, as boston braces for first heat wave of season, bu opens cooling stations for students, to do today: summer solstice celebration, to do today: attend the annual roxbury international film festival, supreme court strikes down ban on gun bump stocks, to do today: explore the historic longfellow house, meet bu’s new lgbtqia+ student resource center director, supreme court upholds access to abortion pill mifepristone, mlb is including negro league stats in its record books. is it too little, too late, pov: biden’s asylum ban is legally, morally, and politically wrong, here’s how you can celebrate juneteenth on and off campus this year, bridgerton season 3 wraps: exactly how historically accurate is netflix’s hit regency-era romantic drama.

'COVID-19 Threw a Curve Ball at Us': Student Photo Essays Document Life During a Pandemic

- Share this story on facebook

- Share this story on twitter

- Share this story on reddit

- Share this story on linkedin

- Get this story's permalink

- Print this story

“We wanted a senior year for the record books, and we got it! … Just not for the reason we expected. COVID-19 threw a curve ball at us, but we’ve made it our mission to find happiness in different places.”

With these words, Duke student Nneka Nwabueze begins a photo essay of student life during the pandemic. It’s part of a class project Digital Documentary Photography: Education, Childhood, and Growth (DOCTST 209S / FS), a Center for Documentary Studies course taught by Susie Post-Rust. Students created essays showcasing how they used documentary photography to explore topics such as essential workers, anti-racism work, the economy and more.

“At the Center for Documentary Studies we have been committed to making art that reflects this unusual time in our collective history,” Post-Rust said. “This semester was not the norm, and these students rose to the challenge! They turned their cameras to the issues of this moment, ranging from responses to coronavirus to Black Lives Matter and even the effort to find identity or normalcy in this moment. Our class was held remotely, and students attended from as far away as southern California or Maine and from as close as campus. Throughout the semester, each student documented their project in an effort to be AWAKE to this moment in history.”

The class was held in conjunction with Duke Service-Learning. To see the photos, created two portfolio sites, Colored by COVID and College with COVID .

Related Story

Eleven student documentary films about women in politics, link to this page.

Copy and paste the URL below to share this page.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

‘Where We Are’: A Photo Essay Contest for Exploring Community

Using an immersive Times series as inspiration, we invite teenagers to document the local communities that interest them. Contest dates: Feb. 14 to March 20.

By The Learning Network

Update, June 6: We plan to announce the winners early next week.

The Covid-19 pandemic closed schools and canceled dances. It emptied basketball courts, theaters, recreation centers and restaurants. It sent clubs, scout troops and other groups online.

Now, many people have ventured back out into physical spaces to gather with one another once again. What does in-person “community” look like today? And what are the different ways people are creating it?

In this new contest, inspired by “ Where We Are ” — an immersive visual project from The New York Times that explores the various places around the world where young people come together — we’re inviting teenagers to create their own photo essays to document the local, offline communities that interest them.

Take a look at the full guidelines and related resources below to see if this is right for your students. We have also posted a student forum and a step-by-step lesson plan . Please ask any questions you have in the comments and we’ll answer you there, or write to us at [email protected]. And, consider hanging this PDF one-page announcement on your class bulletin board.

Here’s what you need to know:

- The Challenge

- A Few Rules

- Resources for Teachers and Students

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Submission Form

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

- History, Facts & Figures

- YSM Dean & Deputy Deans

- YSM Administration

- Department Chairs

- YSM Executive Group

- YSM Board of Permanent Officers

- FAC Documents

- Current FAC Members

- Appointments & Promotions Committees

- Ad Hoc Committees and Working Groups

- Chair Searches

- Leadership Searches

- Organization Charts

- Faculty Demographic Data

- Professionalism Reporting Data

- 2022 Diversity Engagement Survey

- State of the School Archive

- Faculty Climate Survey: YSM Results

- Strategic Planning

- Mission Statement & Process

- Beyond Sterling Hall

- COVID-19 Series Workshops

- Previous Workshops

- Departments & Centers

- Find People

- Biomedical Data Science

- Health Equity

- Inflammation

- Neuroscience

- Global Health

- Diabetes and Metabolism

- Policies & Procedures

- Media Relations

- A to Z YSM Lab Websites

- A-Z Faculty List

- A-Z Staff List

- A to Z Abbreviations

- Dept. Diversity Vice Chairs & Champions

- Dean’s Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Intersex Affairs Website

- Minority Organization for Retention and Expansion Website

- Office for Women in Medicine and Science

- Committee on the Status of Women in Medicine Website

- Director of Scientist Diversity and Inclusion

- Diversity Supplements

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Recruitment

- By Department & Program

- News & Events

- Executive Committee

- Aperture: Women in Medicine

- Self-Reflection

- Portraits of Strength

- Mindful: Mental Health Through Art

- Event Photo Galleries

- Additional Support

- MD-PhD Program

- PA Online Program

- Joint MD Programs

- How to Apply

- Advanced Health Sciences Research

- Clinical Informatics & Data Science

- Clinical Investigation

- Medical Education

- Visiting Student Programs

- Special Programs & Student Opportunities

- Residency & Fellowship Programs

- Center for Med Ed

- Organizational Chart

- Leadership & Staff

- Committee Procedural Info (Login Required)

- Faculty Affairs Department Teams

- Recent Appointments & Promotions

- Academic Clinician Track

- Clinician Educator-Scholar Track

- Clinican-Scientist Track

- Investigator Track

- Traditional Track

- Research Ranks

- Instructor/Lecturer

- Social Work Ranks

- Voluntary Ranks

- Adjunct Ranks

- Other Appt Types

- Appointments

- Reappointments

- Transfer of Track

- Term Extensions

- Timeline for A&P Processes

- Interfolio Faculty Search

- Interfolio A&P Processes

- Yale CV Part 1 (CV1)

- Yale CV Part 2 (CV2)

- Samples of Scholarship

- Teaching Evaluations

- Letters of Evaluation

- Dept A&P Narrative

- A&P Voting

- Faculty Affairs Staff Pages

- OAPD Faculty Workshops

- Leadership & Development Seminars

- List of Faculty Mentors

- Incoming Faculty Orientation

- Faculty Onboarding

- Past YSM Award Recipients

- Past PA Award Recipients

- Past YM Award Recipients

- International Award Recipients

- Nominations Calendar

- OAPD Newsletter

- Fostering a Shared Vision of Professionalism

- Academic Integrity

- Addressing Professionalism Concerns

- Consultation Support for Chairs & Section Chiefs

- Policies & Codes of Conduct

- First Fridays

- Fund for Physician-Scientist Mentorship

- Grant Library

- Grant Writing Course

- Mock Study Section

- Research Paper Writing

- Establishing a Thriving Research Program

- Funding Opportunities

- Join Our Voluntary Faculty

- Child Mental Health: Fostering Wellness in Children