Jump to navigation

Cochrane Training

Chapter 1: starting a review.

Toby J Lasserson, James Thomas, Julian PT Higgins

Key Points:

- Systematic reviews address a need for health decision makers to be able to access high quality, relevant, accessible and up-to-date information.

- Systematic reviews aim to minimize bias through the use of pre-specified research questions and methods that are documented in protocols, and by basing their findings on reliable research.

- Systematic reviews should be conducted by a team that includes domain expertise and methodological expertise, who are free of potential conflicts of interest.

- People who might make – or be affected by – decisions around the use of interventions should be involved in important decisions about the review.

- Good data management, project management and quality assurance mechanisms are essential for the completion of a successful systematic review.

Cite this chapter as: Lasserson TJ, Thomas J, Higgins JPT. Chapter 1: Starting a review. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023). Cochrane, 2023. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

1.1 Why do a systematic review?

Systematic reviews were developed out of a need to ensure that decisions affecting people’s lives can be informed by an up-to-date and complete understanding of the relevant research evidence. With the volume of research literature growing at an ever-increasing rate, it is impossible for individual decision makers to assess this vast quantity of primary research to enable them to make the most appropriate healthcare decisions that do more good than harm. By systematically assessing this primary research, systematic reviews aim to provide an up-to-date summary of the state of research knowledge on an intervention, diagnostic test, prognostic factor or other health or healthcare topic. Systematic reviews address the main problem with ad hoc searching and selection of research, namely that of bias. Just as primary research studies use methods to avoid bias, so should summaries and syntheses of that research.

A systematic review attempts to collate all the empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria in order to answer a specific research question. It uses explicit, systematic methods that are selected with a view to minimizing bias, thus providing more reliable findings from which conclusions can be drawn and decisions made (Antman et al 1992, Oxman and Guyatt 1993). Systematic review methodology, pioneered and developed by Cochrane, sets out a highly structured, transparent and reproducible methodology (Chandler and Hopewell 2013). This involves: the a priori specification of a research question; clarity on the scope of the review and which studies are eligible for inclusion; making every effort to find all relevant research and to ensure that issues of bias in included studies are accounted for; and analysing the included studies in order to draw conclusions based on all the identified research in an impartial and objective way.

This Handbook is about systematic reviews on the effects of interventions, and specifically about methods used by Cochrane to undertake them. Cochrane Reviews use primary research to generate new knowledge about the effects of an intervention (or interventions) used in clinical, public health or policy settings. They aim to provide users with a balanced summary of the potential benefits and harms of interventions and give an indication of how certain they can be of the findings. They can also compare the effectiveness of different interventions with one another and so help users to choose the most appropriate intervention in particular situations. The primary purpose of Cochrane Reviews is therefore to inform people making decisions about health or health care.

Systematic reviews are important for other reasons. New research should be designed or commissioned only if it does not unnecessarily duplicate existing research (Chalmers et al 2014). Therefore, a systematic review should typically be undertaken before embarking on new primary research. Such a review will identify current and ongoing studies, as well as indicate where specific gaps in knowledge exist, or evidence is lacking; for example, where existing studies have not used outcomes that are important to users of research (Macleod et al 2014). A systematic review may also reveal limitations in the conduct of previous studies that might be addressed in the new study or studies.

Systematic reviews are important, often rewarding and, at times, exciting research projects. They offer the opportunity for authors to make authoritative statements about the extent of human knowledge in important areas and to identify priorities for further research. They sometimes cover issues high on the political agenda and receive attention from the media. Conducting research with these impacts is not without its challenges, however, and completing a high-quality systematic review is often demanding and time-consuming. In this chapter we introduce some of the key considerations for potential review authors who are about to start a systematic review.

1.2 What is the review question?

Getting the research question right is critical for the success of a systematic review. Review authors should ensure that the review addresses an important question to those who are expected to use and act upon its conclusions.

We discuss the formulation of questions in detail in Chapter 2 . For a question about the effects of an intervention, the PICO approach is usually used, which is an acronym for Population, Intervention, Comparison(s) and Outcome. Reviews may have additional questions, for example about how interventions were implemented, economic issues, equity issues or patient experience.

To ensure that the review addresses a relevant question in a way that benefits users, it is important to ensure wide input. In most cases, question formulation should therefore be informed by people with various relevant – but potentially different – perspectives (see Chapter 2, Section 2.4 ).

1.3 Who should do a systematic review?

Systematic reviews should be undertaken by a team. Indeed, Cochrane will not publish a review that is proposed to be undertaken by a single person. Working as a team not only spreads the effort, but ensures that tasks such as the selection of studies for eligibility, data extraction and rating the certainty of the evidence will be performed by at least two people independently, minimizing the likelihood of errors. First-time review authors are encouraged to work with others who are experienced in the process of systematic reviews and to attend relevant training.

Review teams must include expertise in the topic area under review. Topic expertise should not be overly narrow, to ensure that all relevant perspectives are considered. Perspectives from different disciplines can help to avoid assumptions or terminology stemming from an over-reliance on a single discipline. Review teams should also include expertise in systematic review methodology, including statistical expertise.

Arguments have been made that methodological expertise is sufficient to perform a review, and that content expertise should be avoided because of the risk of preconceptions about the effects of interventions (Gøtzsche and Ioannidis 2012). However, it is important that both topic and methodological expertise is present to ensure a good mix of skills, knowledge and objectivity, because topic expertise provides important insight into the implementation of the intervention(s), the nature of the condition being treated or prevented, the relationships between outcomes measured, and other factors that may have an impact on decision making.

A Cochrane Review should represent an independent assessment of the evidence and avoiding financial and non-financial conflicts of interest often requires careful management. It will be important to consider if there are any relevant interests that may constitute a conflict of interest. There are situations where employment, holding of patents and other financial support should prevent people joining an author team. Funding of Cochrane Reviews by commercial organizations with an interest in the outcome of the review is not permitted. To ensure that any issues are identified early in the process, authors planning Cochrane Reviews should consult the Conflict of Interest Policy . Authors should make complete declarations of interest before registration of the review, and refresh these annually thereafter until publication and just prior to publication of the protocol and the review. For authors of review updates, this must be done at the time of the decision to update the review, annually thereafter until publication, and just prior to publication. Authors should also update declarations of interest at any point when their circumstances change.

1.3.1 Involving consumers and other stakeholders

Because the priorities of decision makers and consumers may be different from those of researchers, it is important that review authors consider carefully what questions are important to these different stakeholders. Systematic reviews are more likely to be relevant to a broad range of end users if they are informed by the involvement of people with a range of experiences, in terms of both the topic and the methodology (Thomas et al 2004, Rees and Oliver 2017). Engaging consumers and other stakeholders, such as policy makers, research funders and healthcare professionals, increases relevance, promotes mutual learning, improved uptake and decreases research waste.

Mapping out all potential stakeholders specific to the review question is a helpful first step to considering who might be invited to be involved in a review. Stakeholders typically include: patients and consumers; consumer advocates; policy makers and other public officials; guideline developers; professional organizations; researchers; funders of health services and research; healthcare practitioners, and, on occasion, journalists and other media professionals. Balancing seniority, credibility within the given field, and diversity should be considered. Review authors should also take account of the needs of resource-poor countries and regions in the review process (see Chapter 16 ) and invite appropriate input on the scope of the review and the questions it will address.

It is established good practice to ensure that consumers are involved and engaged in health research, including systematic reviews. Cochrane uses the term ‘consumers’ to refer to a wide range of people, including patients or people with personal experience of a healthcare condition, carers and family members, representatives of patients and carers, service users and members of the public. In 2017, a Statement of Principles for consumer involvement in Cochrane was agreed. This seeks to change the culture of research practice to one where both consumers and other stakeholders are joint partners in research from planning, conduct, and reporting to dissemination. Systematic reviews that have had consumer involvement should be more directly applicable to decision makers than those that have not (see online Chapter II ).

1.3.2 Working with consumers and other stakeholders

Methods for working with consumers and other stakeholders include surveys, workshops, focus groups and involvement in advisory groups. Decisions about what methods to use will typically be based on resource availability, but review teams should be aware of the merits and limitations of such methods. Authors will need to decide who to involve and how to provide adequate support for their involvement. This can include financial reimbursement, the provision of training, and stating clearly expectations of involvement, possibly in the form of terms of reference.

While a small number of consumers or other stakeholders may be part of the review team and become co-authors of the subsequent review, it is sometimes important to bring in a wider range of perspectives and to recognize that not everyone has the capacity or interest in becoming an author. Advisory groups offer a convenient approach to involving consumers and other relevant stakeholders, especially for topics in which opinions differ. Important points to ensure successful involvement include the following.

- The review team should co-ordinate the input of the advisory group to inform key review decisions.

- The advisory group’s input should continue throughout the systematic review process to ensure relevance of the review to end users is maintained.

- Advisory group membership should reflect the breadth of the review question, and consideration should be given to involving vulnerable and marginalized people (Steel 2004) to ensure that conclusions on the value of the interventions are well-informed and applicable to all groups in society (see Chapter 16 ).

Templates such as terms of reference, job descriptions, or person specifications for an advisory group help to ensure clarity about the task(s) required and are available from INVOLVE . The website also gives further information on setting and organizing advisory groups. See also the Cochrane training website for further resources to support consumer involvement.

1.4 The importance of reliability

Systematic reviews aim to be an accurate representation of the current state of knowledge about a given issue. As understanding improves, the review can be updated. Nevertheless, it is important that the review itself is accurate at the time of publication. There are two main reasons for this imperative for accuracy. First, health decisions that affect people’s lives are increasingly taken based on systematic review findings. Current knowledge may be imperfect, but decisions will be better informed when taken in the light of the best of current knowledge. Second, systematic reviews form a critical component of legal and regulatory frameworks; for example, drug licensing or insurance coverage. Here, systematic reviews also need to hold up as auditable processes for legal examination. As systematic reviews need to be both correct, and be seen to be correct, detailed evidence-based methods have been developed to guide review authors as to the most appropriate procedures to follow, and what information to include in their reports to aid auditability.

1.4.1 Expectations for the conduct and reporting of Cochrane Reviews

Cochrane has developed methodological expectations for the conduct, reporting and updating of systematic reviews of interventions (MECIR) and their plain language summaries ( Plain Language Expectations for Authors of Cochrane Summaries ; PLEACS). Developed collaboratively by methodologists and Cochrane editors, they are intended to describe the desirable attributes of a Cochrane Review. The expectations are not all relevant at the same stage of review conduct, so care should be taken to identify those that are relevant at specific points during the review. Different methods should be used at different stages of the review in terms of the planning, conduct, reporting and updating of the review.

Each expectation has a title, a rationale and an elaboration. For the purposes of publication of a review with Cochrane, each has the status of either ‘mandatory’ or ‘highly desirable’. Items described as mandatory are expected to be applied, and if they are not then an appropriate justification should be provided; failure to implement such items may be used as a basis for deciding not to publish a review in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR). Items described as highly desirable should generally be implemented, but there are reasonable exceptions and justifications are not required.

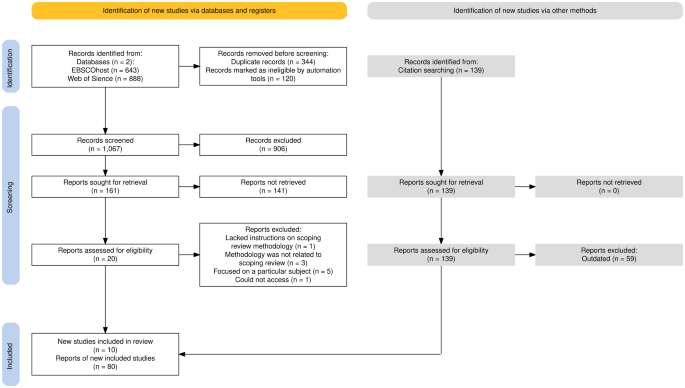

All MECIR expectations for the conduct of a review are presented in the relevant chapters of this Handbook . Expectations for reporting of completed reviews (including PLEACS) are described in online Chapter III . The recommendations provided in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement have been incorporated into the Cochrane reporting expectations, ensuring compliance with the PRISMA recommendations and summarizing attributes of reporting that should allow a full assessment of the methods and findings of the review (Moher et al 2009).

1.5 Protocol development

Preparing a systematic review is complex and involves many judgements. To minimize the potential for bias in the review process, these judgements should be made as far as possible in ways that do not depend on the findings of the studies included in the review. Review authors’ prior knowledge of the evidence may, for example, influence the definition of a systematic review question, the choice of criteria for study eligibility, or the pre-specification of intervention comparisons and outcomes to analyse. It is important that the methods to be used should be established and documented in advance (see MECIR Box 1.5.a , MECIR Box 1.5.b and MECIR Box 1.5.c ).

Publication of a protocol for a review that is written without knowledge of the available studies reduces the impact of review authors’ biases, promotes transparency of methods and processes, reduces the potential for duplication, allows peer review of the planned methods before they have been completed, and offers an opportunity for the review team to plan resources and logistics for undertaking the review itself. All chapters in the Handbook should be consulted when drafting the protocol. Since systematic reviews are by their nature retrospective, an element of knowledge of the evidence is often inevitable. This is one reason why non-content experts such as methodologists should be part of the review team (see Section 1.3 ). Two exceptions to the retrospective nature of a systematic review are a meta-analysis of a prospectively planned series of trials and some living systematic reviews, as described in Chapter 22 .

The review question should determine the methods used in the review, and not vice versa. The question may concern a relatively straightforward comparison of one treatment with another; or it may necessitate plans to compare different treatments as part of a network meta-analysis, or assess differential effects of an intervention in different populations or delivered in different ways.

The protocol sets out the context in which the review is being conducted. It presents an opportunity to develop ideas that are foundational for the review. This concerns, most explicitly, definition of the eligibility criteria such as the study participants and the choice of comparators and outcomes. The eligibility criteria may also be defined following the development of a logic model (or an articulation of the aspects of an extent logic model that the review is addressing) to explain how the intervention might work (see Chapter 2, Section 2.5.1 ).

MECIR Box 1.5.a Relevant expectations for conduct of intervention reviews

A key purpose of the protocol is to make plans to minimize bias in the eventual findings of the review. Reliable synthesis of available evidence requires a planned, systematic approach. Threats to the validity of systematic reviews can come from the studies they include or the process by which reviews are conducted. Biases within the studies can arise from the method by which participants are allocated to the intervention groups, awareness of intervention group assignment, and the collection, analysis and reporting of data. Methods for examining these issues should be specified in the protocol. Review processes can generate bias through a failure to identify an unbiased (and preferably complete) set of studies, and poor quality assurance throughout the review. The availability of research may be influenced by the nature of the results (i.e. reporting bias). To reduce the impact of this form of bias, searching may need to include unpublished sources of evidence (Dwan et al 2013) ( MECIR Box 1.5.b ).

MECIR Box 1.5.b Relevant expectations for the conduct of intervention reviews

Developing a protocol for a systematic review has benefits beyond reducing bias. Investing effort in designing a systematic review will make the process more manageable and help to inform key priorities for the review. Defining the question, referring to it throughout, and using appropriate methods to address the question focuses the analysis and reporting, ensuring the review is most likely to inform treatment decisions for funders, policy makers, healthcare professionals and consumers. Details of the planned analyses, including investigations of variability across studies, should be specified in the protocol, along with methods for interpreting the results through the systematic consideration of factors that affect confidence in estimates of intervention effect ( MECIR Box 1.5.c ).

MECIR Box 1.5.c Relevant expectations for conduct of intervention reviews

While the intention should be that a review will adhere to the published protocol, changes in a review protocol are sometimes necessary. This is also the case for a protocol for a randomized trial, which must sometimes be changed to adapt to unanticipated circumstances such as problems with participant recruitment, data collection or event rates. While every effort should be made to adhere to a predetermined protocol, this is not always possible or appropriate. It is important, however, that changes in the protocol should not be made based on how they affect the outcome of the research study, whether it is a randomized trial or a systematic review. Post hoc decisions made when the impact on the results of the research is known, such as excluding selected studies from a systematic review, or changing the statistical analysis, are highly susceptible to bias and should therefore be avoided unless there are reasonable grounds for doing this.

Enabling access to a protocol through publication (all Cochrane Protocols are published in the CDSR ) and registration on the PROSPERO register of systematic reviews reduces duplication of effort, research waste, and promotes accountability. Changes to the methods outlined in the protocol should be transparently declared.

This Handbook provides details of the systematic review methods developed or selected by Cochrane. They are intended to address the need for rigour, comprehensiveness and transparency in preparing a Cochrane systematic review. All relevant chapters – including those describing procedures to be followed in the later stages of the review – should be consulted during the preparation of the protocol. A more specific description of the structure of Cochrane Protocols is provide in online Chapter II .

1.6 Data management and quality assurance

Systematic reviews should be replicable, and retaining a record of the inclusion decisions, data collection, transformations or adjustment of data will help to establish a secure and retrievable audit trail. They can be operationally complex projects, often involving large research teams operating in different sites across the world. Good data management processes are essential to ensure that data are not inadvertently lost, facilitating the identification and correction of errors and supporting future efforts to update and maintain the review. Transparent reporting of review decisions enables readers to assess the reliability of the review for themselves.

Review management software, such as Covidence and EPPI-Reviewer , can be used to assist data management and maintain consistent and standardized records of decisions made throughout the review. These tools offer a central repository for review data that can be accessed remotely throughout the world by members of the review team. They record independent assessment of studies for inclusion, risk of bias and extraction of data, enabling checks to be made later in the process if needed. Research has shown that even experienced reviewers make mistakes and disagree with one another on risk-of-bias assessments, so it is particularly important to maintain quality assurance here, despite its cost in terms of author time. As more sophisticated information technology tools begin to be deployed in reviews (see Chapter 4, Section 4.6.6.2 and Chapter 22, Section 22.2.4 ), it is increasingly apparent that all review data – including the initial decisions about study eligibility – have value beyond the scope of the individual review. For example, review updates can be made more efficient through (semi-) automation when data from the original review are available for machine learning.

1.7 Chapter information

Authors: Toby J Lasserson, James Thomas, Julian PT Higgins

Acknowledgements: This chapter builds on earlier versions of the Handbook . We would like to thank Ruth Foxlee, Richard Morley, Soumyadeep Bhaumik, Mona Nasser, Dan Fox and Sally Crowe for their contributions to Section 1.3 .

Funding: JT is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care North Thames at Barts Health NHS Trust. JPTH is a member of the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol. JPTH received funding from National Institute for Health Research Senior Investigator award NF-SI-0617-10145. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

1.8 References

Antman E, Lau J, Kupelnick B, Mosteller F, Chalmers T. A comparison of results of meta-analyses of randomized control trials and recommendations of clinical experts: treatment for myocardial infarction. JAMA 1992; 268 : 240–248.

Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B, Garattini S, Grant J, Gulmezoglu AM, Howells DW, Ioannidis JP, Oliver S. How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. Lancet 2014; 383 : 156–165.

Chandler J, Hopewell S. Cochrane methods – twenty years experience in developing systematic review methods. Systematic Reviews 2013; 2 : 76.

Dwan K, Gamble C, Williamson PR, Kirkham JJ, Reporting Bias Group. Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias: an updated review. PloS One 2013; 8 : e66844.

Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA. Content area experts as authors: helpful or harmful for systematic reviews and meta-analyses? BMJ 2012; 345 .

Macleod MR, Michie S, Roberts I, Dirnagl U, Chalmers I, Ioannidis JP, Al-Shahi Salman R, Chan AW, Glasziou P. Biomedical research: increasing value, reducing waste. Lancet 2014; 383 : 101–104.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine 2009; 6 : e1000097.

Oxman A, Guyatt G. The science of reviewing research. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1993; 703 : 125–133.

Rees R, Oliver S. Stakeholder perspectives and participation in reviews. In: Gough D, Oliver S, Thomas J, editors. An Introduction to Systematic Reviews . 2nd ed. London: Sage; 2017. p. 17–34.

Steel R. Involving marginalised and vulnerable people in research: a consultation document (2nd revision). INVOLVE; 2004.

Thomas J, Harden A, Oakley A, Oliver S, Sutcliffe K, Rees R, Brunton G, Kavanagh J. Integrating qualitative research with trials in systematic reviews. BMJ 2004; 328 : 1010–1012.

For permission to re-use material from the Handbook (either academic or commercial), please see here for full details.

Systematic Review

- Library Help

- What is a Systematic Review (SR)?

Steps of a Systematic Review

- Framing a Research Question

- Developing a Search Strategy

- Searching the Literature

- Managing the Process

- Meta-analysis

- Publishing your Systematic Review

Forms and templates

Image: David Parmenter's Shop

- PICO Template

- Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

- Database Search Log

- Review Matrix

- Cochrane Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Included Studies

• PRISMA Flow Diagram - Record the numbers of retrieved references and included/excluded studies. You can use the Create Flow Diagram tool to automate the process.

• PRISMA Checklist - Checklist of items to include when reporting a systematic review or meta-analysis

PRISMA 2020 and PRISMA-S: Common Questions on Tracking Records and the Flow Diagram

- PROSPERO Template

- Manuscript Template

- Steps of SR (text)

- Steps of SR (visual)

- Steps of SR (PIECES)

Adapted from A Guide to Conducting Systematic Reviews: Steps in a Systematic Review by Cornell University Library

Source: Cochrane Consumers and Communications (infographics are free to use and licensed under Creative Commons )

Check the following visual resources titled " What Are Systematic Reviews?"

- Video with closed captions available

- Animated Storyboard

- << Previous: What is a Systematic Review (SR)?

- Next: Framing a Research Question >>

- Last Updated: May 8, 2024 1:44 PM

- URL: https://lib.guides.umd.edu/SR

- Open access

- Published: 01 August 2019

A step by step guide for conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis with simulation data

- Gehad Mohamed Tawfik 1 , 2 ,

- Kadek Agus Surya Dila 2 , 3 ,

- Muawia Yousif Fadlelmola Mohamed 2 , 4 ,

- Dao Ngoc Hien Tam 2 , 5 ,

- Nguyen Dang Kien 2 , 6 ,

- Ali Mahmoud Ahmed 2 , 7 &

- Nguyen Tien Huy 8 , 9 , 10

Tropical Medicine and Health volume 47 , Article number: 46 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

806k Accesses

193 Citations

94 Altmetric

Metrics details

The massive abundance of studies relating to tropical medicine and health has increased strikingly over the last few decades. In the field of tropical medicine and health, a well-conducted systematic review and meta-analysis (SR/MA) is considered a feasible solution for keeping clinicians abreast of current evidence-based medicine. Understanding of SR/MA steps is of paramount importance for its conduction. It is not easy to be done as there are obstacles that could face the researcher. To solve those hindrances, this methodology study aimed to provide a step-by-step approach mainly for beginners and junior researchers, in the field of tropical medicine and other health care fields, on how to properly conduct a SR/MA, in which all the steps here depicts our experience and expertise combined with the already well-known and accepted international guidance.

We suggest that all steps of SR/MA should be done independently by 2–3 reviewers’ discussion, to ensure data quality and accuracy.

SR/MA steps include the development of research question, forming criteria, search strategy, searching databases, protocol registration, title, abstract, full-text screening, manual searching, extracting data, quality assessment, data checking, statistical analysis, double data checking, and manuscript writing.

Introduction

The amount of studies published in the biomedical literature, especially tropical medicine and health, has increased strikingly over the last few decades. This massive abundance of literature makes clinical medicine increasingly complex, and knowledge from various researches is often needed to inform a particular clinical decision. However, available studies are often heterogeneous with regard to their design, operational quality, and subjects under study and may handle the research question in a different way, which adds to the complexity of evidence and conclusion synthesis [ 1 ].

Systematic review and meta-analyses (SR/MAs) have a high level of evidence as represented by the evidence-based pyramid. Therefore, a well-conducted SR/MA is considered a feasible solution in keeping health clinicians ahead regarding contemporary evidence-based medicine.

Differing from a systematic review, unsystematic narrative review tends to be descriptive, in which the authors select frequently articles based on their point of view which leads to its poor quality. A systematic review, on the other hand, is defined as a review using a systematic method to summarize evidence on questions with a detailed and comprehensive plan of study. Furthermore, despite the increasing guidelines for effectively conducting a systematic review, we found that basic steps often start from framing question, then identifying relevant work which consists of criteria development and search for articles, appraise the quality of included studies, summarize the evidence, and interpret the results [ 2 , 3 ]. However, those simple steps are not easy to be reached in reality. There are many troubles that a researcher could be struggled with which has no detailed indication.

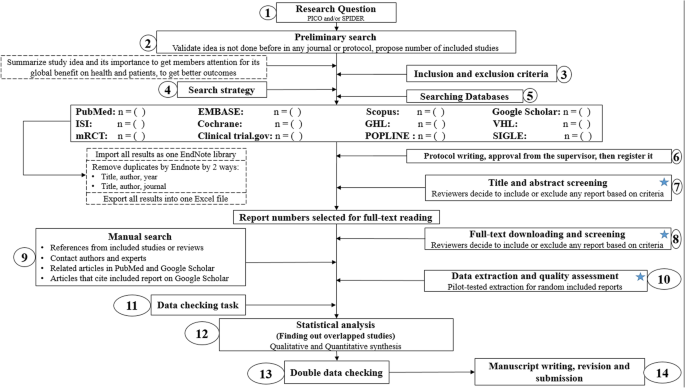

Conducting a SR/MA in tropical medicine and health may be difficult especially for young researchers; therefore, understanding of its essential steps is crucial. It is not easy to be done as there are obstacles that could face the researcher. To solve those hindrances, we recommend a flow diagram (Fig. 1 ) which illustrates a detailed and step-by-step the stages for SR/MA studies. This methodology study aimed to provide a step-by-step approach mainly for beginners and junior researchers, in the field of tropical medicine and other health care fields, on how to properly and succinctly conduct a SR/MA; all the steps here depicts our experience and expertise combined with the already well known and accepted international guidance.

Detailed flow diagram guideline for systematic review and meta-analysis steps. Note : Star icon refers to “2–3 reviewers screen independently”

Methods and results

Detailed steps for conducting any systematic review and meta-analysis.

We searched the methods reported in published SR/MA in tropical medicine and other healthcare fields besides the published guidelines like Cochrane guidelines {Higgins, 2011 #7} [ 4 ] to collect the best low-bias method for each step of SR/MA conduction steps. Furthermore, we used guidelines that we apply in studies for all SR/MA steps. We combined these methods in order to conclude and conduct a detailed flow diagram that shows the SR/MA steps how being conducted.

Any SR/MA must follow the widely accepted Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis statement (PRISMA checklist 2009) (Additional file 5 : Table S1) [ 5 ].

We proposed our methods according to a valid explanatory simulation example choosing the topic of “evaluating safety of Ebola vaccine,” as it is known that Ebola is a very rare tropical disease but fatal. All the explained methods feature the standards followed internationally, with our compiled experience in the conduct of SR beside it, which we think proved some validity. This is a SR under conduct by a couple of researchers teaming in a research group, moreover, as the outbreak of Ebola which took place (2013–2016) in Africa resulted in a significant mortality and morbidity. Furthermore, since there are many published and ongoing trials assessing the safety of Ebola vaccines, we thought this would provide a great opportunity to tackle this hotly debated issue. Moreover, Ebola started to fire again and new fatal outbreak appeared in the Democratic Republic of Congo since August 2018, which caused infection to more than 1000 people according to the World Health Organization, and 629 people have been killed till now. Hence, it is considered the second worst Ebola outbreak, after the first one in West Africa in 2014 , which infected more than 26,000 and killed about 11,300 people along outbreak course.

Research question and objectives

Like other study designs, the research question of SR/MA should be feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, and relevant. Therefore, a clear, logical, and well-defined research question should be formulated. Usually, two common tools are used: PICO or SPIDER. PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) is used mostly in quantitative evidence synthesis. Authors demonstrated that PICO holds more sensitivity than the more specific SPIDER approach [ 6 ]. SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type) was proposed as a method for qualitative and mixed methods search.

We here recommend a combined approach of using either one or both the SPIDER and PICO tools to retrieve a comprehensive search depending on time and resources limitations. When we apply this to our assumed research topic, being of qualitative nature, the use of SPIDER approach is more valid.

PICO is usually used for systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trial study. For the observational study (without intervention or comparator), in many tropical and epidemiological questions, it is usually enough to use P (Patient) and O (outcome) only to formulate a research question. We must indicate clearly the population (P), then intervention (I) or exposure. Next, it is necessary to compare (C) the indicated intervention with other interventions, i.e., placebo. Finally, we need to clarify which are our relevant outcomes.

To facilitate comprehension, we choose the Ebola virus disease (EVD) as an example. Currently, the vaccine for EVD is being developed and under phase I, II, and III clinical trials; we want to know whether this vaccine is safe and can induce sufficient immunogenicity to the subjects.

An example of a research question for SR/MA based on PICO for this issue is as follows: How is the safety and immunogenicity of Ebola vaccine in human? (P: healthy subjects (human), I: vaccination, C: placebo, O: safety or adverse effects)

Preliminary research and idea validation

We recommend a preliminary search to identify relevant articles, ensure the validity of the proposed idea, avoid duplication of previously addressed questions, and assure that we have enough articles for conducting its analysis. Moreover, themes should focus on relevant and important health-care issues, consider global needs and values, reflect the current science, and be consistent with the adopted review methods. Gaining familiarity with a deep understanding of the study field through relevant videos and discussions is of paramount importance for better retrieval of results. If we ignore this step, our study could be canceled whenever we find out a similar study published before. This means we are wasting our time to deal with a problem that has been tackled for a long time.

To do this, we can start by doing a simple search in PubMed or Google Scholar with search terms Ebola AND vaccine. While doing this step, we identify a systematic review and meta-analysis of determinant factors influencing antibody response from vaccination of Ebola vaccine in non-human primate and human [ 7 ], which is a relevant paper to read to get a deeper insight and identify gaps for better formulation of our research question or purpose. We can still conduct systematic review and meta-analysis of Ebola vaccine because we evaluate safety as a different outcome and different population (only human).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligibility criteria are based on the PICO approach, study design, and date. Exclusion criteria mostly are unrelated, duplicated, unavailable full texts, or abstract-only papers. These exclusions should be stated in advance to refrain the researcher from bias. The inclusion criteria would be articles with the target patients, investigated interventions, or the comparison between two studied interventions. Briefly, it would be articles which contain information answering our research question. But the most important is that it should be clear and sufficient information, including positive or negative, to answer the question.

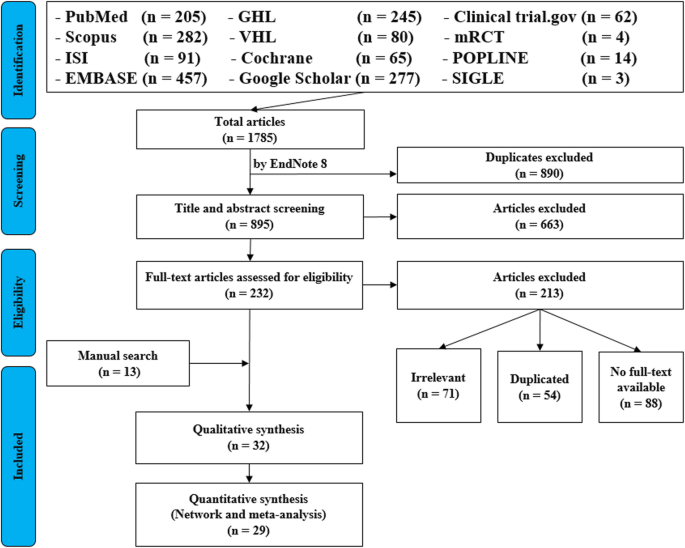

For the topic we have chosen, we can make inclusion criteria: (1) any clinical trial evaluating the safety of Ebola vaccine and (2) no restriction regarding country, patient age, race, gender, publication language, and date. Exclusion criteria are as follows: (1) study of Ebola vaccine in non-human subjects or in vitro studies; (2) study with data not reliably extracted, duplicate, or overlapping data; (3) abstract-only papers as preceding papers, conference, editorial, and author response theses and books; (4) articles without available full text available; and (5) case reports, case series, and systematic review studies. The PRISMA flow diagram template that is used in SR/MA studies can be found in Fig. 2 .

PRISMA flow diagram of studies’ screening and selection

Search strategy

A standard search strategy is used in PubMed, then later it is modified according to each specific database to get the best relevant results. The basic search strategy is built based on the research question formulation (i.e., PICO or PICOS). Search strategies are constructed to include free-text terms (e.g., in the title and abstract) and any appropriate subject indexing (e.g., MeSH) expected to retrieve eligible studies, with the help of an expert in the review topic field or an information specialist. Additionally, we advise not to use terms for the Outcomes as their inclusion might hinder the database being searched to retrieve eligible studies because the used outcome is not mentioned obviously in the articles.

The improvement of the search term is made while doing a trial search and looking for another relevant term within each concept from retrieved papers. To search for a clinical trial, we can use these descriptors in PubMed: “clinical trial”[Publication Type] OR “clinical trials as topic”[MeSH terms] OR “clinical trial”[All Fields]. After some rounds of trial and refinement of search term, we formulate the final search term for PubMed as follows: (ebola OR ebola virus OR ebola virus disease OR EVD) AND (vaccine OR vaccination OR vaccinated OR immunization) AND (“clinical trial”[Publication Type] OR “clinical trials as topic”[MeSH Terms] OR “clinical trial”[All Fields]). Because the study for this topic is limited, we do not include outcome term (safety and immunogenicity) in the search term to capture more studies.

Search databases, import all results to a library, and exporting to an excel sheet

According to the AMSTAR guidelines, at least two databases have to be searched in the SR/MA [ 8 ], but as you increase the number of searched databases, you get much yield and more accurate and comprehensive results. The ordering of the databases depends mostly on the review questions; being in a study of clinical trials, you will rely mostly on Cochrane, mRCTs, or International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP). Here, we propose 12 databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, EMBASE, GHL, VHL, Cochrane, Google Scholar, Clinical trials.gov , mRCTs, POPLINE, and SIGLE), which help to cover almost all published articles in tropical medicine and other health-related fields. Among those databases, POPLINE focuses on reproductive health. Researchers should consider to choose relevant database according to the research topic. Some databases do not support the use of Boolean or quotation; otherwise, there are some databases that have special searching way. Therefore, we need to modify the initial search terms for each database to get appreciated results; therefore, manipulation guides for each online database searches are presented in Additional file 5 : Table S2. The detailed search strategy for each database is found in Additional file 5 : Table S3. The search term that we created in PubMed needs customization based on a specific characteristic of the database. An example for Google Scholar advanced search for our topic is as follows:

With all of the words: ebola virus

With at least one of the words: vaccine vaccination vaccinated immunization

Where my words occur: in the title of the article

With all of the words: EVD

Finally, all records are collected into one Endnote library in order to delete duplicates and then to it export into an excel sheet. Using remove duplicating function with two options is mandatory. All references which have (1) the same title and author, and published in the same year, and (2) the same title and author, and published in the same journal, would be deleted. References remaining after this step should be exported to an excel file with essential information for screening. These could be the authors’ names, publication year, journal, DOI, URL link, and abstract.

Protocol writing and registration

Protocol registration at an early stage guarantees transparency in the research process and protects from duplication problems. Besides, it is considered a documented proof of team plan of action, research question, eligibility criteria, intervention/exposure, quality assessment, and pre-analysis plan. It is recommended that researchers send it to the principal investigator (PI) to revise it, then upload it to registry sites. There are many registry sites available for SR/MA like those proposed by Cochrane and Campbell collaborations; however, we recommend registering the protocol into PROSPERO as it is easier. The layout of a protocol template, according to PROSPERO, can be found in Additional file 5 : File S1.

Title and abstract screening

Decisions to select retrieved articles for further assessment are based on eligibility criteria, to minimize the chance of including non-relevant articles. According to the Cochrane guidance, two reviewers are a must to do this step, but as for beginners and junior researchers, this might be tiresome; thus, we propose based on our experience that at least three reviewers should work independently to reduce the chance of error, particularly in teams with a large number of authors to add more scrutiny and ensure proper conduct. Mostly, the quality with three reviewers would be better than two, as two only would have different opinions from each other, so they cannot decide, while the third opinion is crucial. And here are some examples of systematic reviews which we conducted following the same strategy (by a different group of researchers in our research group) and published successfully, and they feature relevant ideas to tropical medicine and disease [ 9 , 10 , 11 ].

In this step, duplications will be removed manually whenever the reviewers find them out. When there is a doubt about an article decision, the team should be inclusive rather than exclusive, until the main leader or PI makes a decision after discussion and consensus. All excluded records should be given exclusion reasons.

Full text downloading and screening

Many search engines provide links for free to access full-text articles. In case not found, we can search in some research websites as ResearchGate, which offer an option of direct full-text request from authors. Additionally, exploring archives of wanted journals, or contacting PI to purchase it if available. Similarly, 2–3 reviewers work independently to decide about included full texts according to eligibility criteria, with reporting exclusion reasons of articles. In case any disagreement has occurred, the final decision has to be made by discussion.

Manual search

One has to exhaust all possibilities to reduce bias by performing an explicit hand-searching for retrieval of reports that may have been dropped from first search [ 12 ]. We apply five methods to make manual searching: searching references from included studies/reviews, contacting authors and experts, and looking at related articles/cited articles in PubMed and Google Scholar.

We describe here three consecutive methods to increase and refine the yield of manual searching: firstly, searching reference lists of included articles; secondly, performing what is known as citation tracking in which the reviewers track all the articles that cite each one of the included articles, and this might involve electronic searching of databases; and thirdly, similar to the citation tracking, we follow all “related to” or “similar” articles. Each of the abovementioned methods can be performed by 2–3 independent reviewers, and all the possible relevant article must undergo further scrutiny against the inclusion criteria, after following the same records yielded from electronic databases, i.e., title/abstract and full-text screening.

We propose an independent reviewing by assigning each member of the teams a “tag” and a distinct method, to compile all the results at the end for comparison of differences and discussion and to maximize the retrieval and minimize the bias. Similarly, the number of included articles has to be stated before addition to the overall included records.

Data extraction and quality assessment

This step entitles data collection from included full-texts in a structured extraction excel sheet, which is previously pilot-tested for extraction using some random studies. We recommend extracting both adjusted and non-adjusted data because it gives the most allowed confounding factor to be used in the analysis by pooling them later [ 13 ]. The process of extraction should be executed by 2–3 independent reviewers. Mostly, the sheet is classified into the study and patient characteristics, outcomes, and quality assessment (QA) tool.

Data presented in graphs should be extracted by software tools such as Web plot digitizer [ 14 ]. Most of the equations that can be used in extraction prior to analysis and estimation of standard deviation (SD) from other variables is found inside Additional file 5 : File S2 with their references as Hozo et al. [ 15 ], Xiang et al. [ 16 ], and Rijkom et al. [ 17 ]. A variety of tools are available for the QA, depending on the design: ROB-2 Cochrane tool for randomized controlled trials [ 18 ] which is presented as Additional file 1 : Figure S1 and Additional file 2 : Figure S2—from a previous published article data—[ 19 ], NIH tool for observational and cross-sectional studies [ 20 ], ROBINS-I tool for non-randomize trials [ 21 ], QUADAS-2 tool for diagnostic studies, QUIPS tool for prognostic studies, CARE tool for case reports, and ToxRtool for in vivo and in vitro studies. We recommend that 2–3 reviewers independently assess the quality of the studies and add to the data extraction form before the inclusion into the analysis to reduce the risk of bias. In the NIH tool for observational studies—cohort and cross-sectional—as in this EBOLA case, to evaluate the risk of bias, reviewers should rate each of the 14 items into dichotomous variables: yes, no, or not applicable. An overall score is calculated by adding all the items scores as yes equals one, while no and NA equals zero. A score will be given for every paper to classify them as poor, fair, or good conducted studies, where a score from 0–5 was considered poor, 6–9 as fair, and 10–14 as good.

In the EBOLA case example above, authors can extract the following information: name of authors, country of patients, year of publication, study design (case report, cohort study, or clinical trial or RCT), sample size, the infected point of time after EBOLA infection, follow-up interval after vaccination time, efficacy, safety, adverse effects after vaccinations, and QA sheet (Additional file 6 : Data S1).

Data checking

Due to the expected human error and bias, we recommend a data checking step, in which every included article is compared with its counterpart in an extraction sheet by evidence photos, to detect mistakes in data. We advise assigning articles to 2–3 independent reviewers, ideally not the ones who performed the extraction of those articles. When resources are limited, each reviewer is assigned a different article than the one he extracted in the previous stage.

Statistical analysis

Investigators use different methods for combining and summarizing findings of included studies. Before analysis, there is an important step called cleaning of data in the extraction sheet, where the analyst organizes extraction sheet data in a form that can be read by analytical software. The analysis consists of 2 types namely qualitative and quantitative analysis. Qualitative analysis mostly describes data in SR studies, while quantitative analysis consists of two main types: MA and network meta-analysis (NMA). Subgroup, sensitivity, cumulative analyses, and meta-regression are appropriate for testing whether the results are consistent or not and investigating the effect of certain confounders on the outcome and finding the best predictors. Publication bias should be assessed to investigate the presence of missing studies which can affect the summary.

To illustrate basic meta-analysis, we provide an imaginary data for the research question about Ebola vaccine safety (in terms of adverse events, 14 days after injection) and immunogenicity (Ebola virus antibodies rise in geometric mean titer, 6 months after injection). Assuming that from searching and data extraction, we decided to do an analysis to evaluate Ebola vaccine “A” safety and immunogenicity. Other Ebola vaccines were not meta-analyzed because of the limited number of studies (instead, it will be included for narrative review). The imaginary data for vaccine safety meta-analysis can be accessed in Additional file 7 : Data S2. To do the meta-analysis, we can use free software, such as RevMan [ 22 ] or R package meta [ 23 ]. In this example, we will use the R package meta. The tutorial of meta package can be accessed through “General Package for Meta-Analysis” tutorial pdf [ 23 ]. The R codes and its guidance for meta-analysis done can be found in Additional file 5 : File S3.

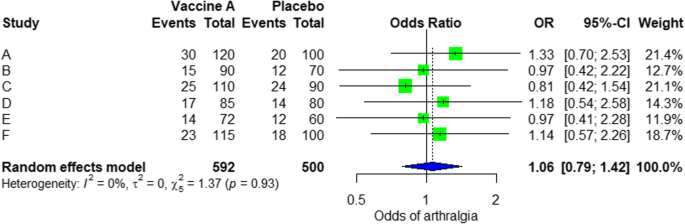

For the analysis, we assume that the study is heterogenous in nature; therefore, we choose a random effect model. We did an analysis on the safety of Ebola vaccine A. From the data table, we can see some adverse events occurring after intramuscular injection of vaccine A to the subject of the study. Suppose that we include six studies that fulfill our inclusion criteria. We can do a meta-analysis for each of the adverse events extracted from the studies, for example, arthralgia, from the results of random effect meta-analysis using the R meta package.

From the results shown in Additional file 3 : Figure S3, we can see that the odds ratio (OR) of arthralgia is 1.06 (0.79; 1.42), p value = 0.71, which means that there is no association between the intramuscular injection of Ebola vaccine A and arthralgia, as the OR is almost one, and besides, the P value is insignificant as it is > 0.05.

In the meta-analysis, we can also visualize the results in a forest plot. It is shown in Fig. 3 an example of a forest plot from the simulated analysis.

Random effect model forest plot for comparison of vaccine A versus placebo

From the forest plot, we can see six studies (A to F) and their respective OR (95% CI). The green box represents the effect size (in this case, OR) of each study. The bigger the box means the study weighted more (i.e., bigger sample size). The blue diamond shape represents the pooled OR of the six studies. We can see the blue diamond cross the vertical line OR = 1, which indicates no significance for the association as the diamond almost equalized in both sides. We can confirm this also from the 95% confidence interval that includes one and the p value > 0.05.

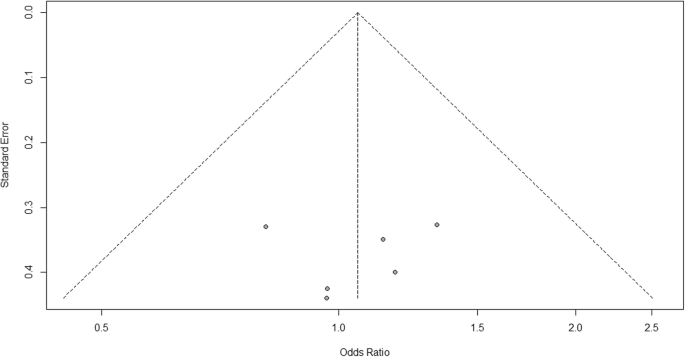

For heterogeneity, we see that I 2 = 0%, which means no heterogeneity is detected; the study is relatively homogenous (it is rare in the real study). To evaluate publication bias related to the meta-analysis of adverse events of arthralgia, we can use the metabias function from the R meta package (Additional file 4 : Figure S4) and visualization using a funnel plot. The results of publication bias are demonstrated in Fig. 4 . We see that the p value associated with this test is 0.74, indicating symmetry of the funnel plot. We can confirm it by looking at the funnel plot.

Publication bias funnel plot for comparison of vaccine A versus placebo

Looking at the funnel plot, the number of studies at the left and right side of the funnel plot is the same; therefore, the plot is symmetry, indicating no publication bias detected.

Sensitivity analysis is a procedure used to discover how different values of an independent variable will influence the significance of a particular dependent variable by removing one study from MA. If all included study p values are < 0.05, hence, removing any study will not change the significant association. It is only performed when there is a significant association, so if the p value of MA done is 0.7—more than one—the sensitivity analysis is not needed for this case study example. If there are 2 studies with p value > 0.05, removing any of the two studies will result in a loss of the significance.

Double data checking

For more assurance on the quality of results, the analyzed data should be rechecked from full-text data by evidence photos, to allow an obvious check for the PI of the study.

Manuscript writing, revision, and submission to a journal

Writing based on four scientific sections: introduction, methods, results, and discussion, mostly with a conclusion. Performing a characteristic table for study and patient characteristics is a mandatory step which can be found as a template in Additional file 5 : Table S3.

After finishing the manuscript writing, characteristics table, and PRISMA flow diagram, the team should send it to the PI to revise it well and reply to his comments and, finally, choose a suitable journal for the manuscript which fits with considerable impact factor and fitting field. We need to pay attention by reading the author guidelines of journals before submitting the manuscript.

The role of evidence-based medicine in biomedical research is rapidly growing. SR/MAs are also increasing in the medical literature. This paper has sought to provide a comprehensive approach to enable reviewers to produce high-quality SR/MAs. We hope that readers could gain general knowledge about how to conduct a SR/MA and have the confidence to perform one, although this kind of study requires complex steps compared to narrative reviews.

Having the basic steps for conduction of MA, there are many advanced steps that are applied for certain specific purposes. One of these steps is meta-regression which is performed to investigate the association of any confounder and the results of the MA. Furthermore, there are other types rather than the standard MA like NMA and MA. In NMA, we investigate the difference between several comparisons when there were not enough data to enable standard meta-analysis. It uses both direct and indirect comparisons to conclude what is the best between the competitors. On the other hand, mega MA or MA of patients tend to summarize the results of independent studies by using its individual subject data. As a more detailed analysis can be done, it is useful in conducting repeated measure analysis and time-to-event analysis. Moreover, it can perform analysis of variance and multiple regression analysis; however, it requires homogenous dataset and it is time-consuming in conduct [ 24 ].

Conclusions

Systematic review/meta-analysis steps include development of research question and its validation, forming criteria, search strategy, searching databases, importing all results to a library and exporting to an excel sheet, protocol writing and registration, title and abstract screening, full-text screening, manual searching, extracting data and assessing its quality, data checking, conducting statistical analysis, double data checking, manuscript writing, revising, and submitting to a journal.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Network meta-analysis

Principal investigator

Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis statement

Quality assessment

Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type

Systematic review and meta-analyses

Bello A, Wiebe N, Garg A, Tonelli M. Evidence-based decision-making 2: systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Methods Mol Biol (Clifton, NJ). 2015;1281:397–416.

Article Google Scholar

Khan KS, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G. Five steps to conducting a systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2003;96(3):118–21.

Rys P, Wladysiuk M, Skrzekowska-Baran I, Malecki MT. Review articles, systematic reviews and meta-analyses: which can be trusted? Polskie Archiwum Medycyny Wewnetrznej. 2009;119(3):148–56.

PubMed Google Scholar

Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. 2011.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R, Cheraghi-Sohi S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:579.

Gross L, Lhomme E, Pasin C, Richert L, Thiebaut R. Ebola vaccine development: systematic review of pre-clinical and clinical studies, and meta-analysis of determinants of antibody response variability after vaccination. Int J Infect Dis. 2018;74:83–96.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, ... Henry DA. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008.

Giang HTN, Banno K, Minh LHN, Trinh LT, Loc LT, Eltobgy A, et al. Dengue hemophagocytic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis on epidemiology, clinical signs, outcomes, and risk factors. Rev Med Virol. 2018;28(6):e2005.

Morra ME, Altibi AMA, Iqtadar S, Minh LHN, Elawady SS, Hallab A, et al. Definitions for warning signs and signs of severe dengue according to the WHO 2009 classification: systematic review of literature. Rev Med Virol. 2018;28(4):e1979.

Morra ME, Van Thanh L, Kamel MG, Ghazy AA, Altibi AMA, Dat LM, et al. Clinical outcomes of current medical approaches for Middle East respiratory syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol. 2018;28(3):e1977.

Vassar M, Atakpo P, Kash MJ. Manual search approaches used by systematic reviewers in dermatology. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA. 2016;104(4):302.

Naunheim MR, Remenschneider AK, Scangas GA, Bunting GW, Deschler DG. The effect of initial tracheoesophageal voice prosthesis size on postoperative complications and voice outcomes. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2016;125(6):478–84.

Rohatgi AJaiWa. Web Plot Digitizer. ht tp. 2014;2.

Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5(1):13.

Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):135.

Van Rijkom HM, Truin GJ, Van’t Hof MA. A meta-analysis of clinical studies on the caries-inhibiting effect of fluoride gel treatment. Carries Res. 1998;32(2):83–92.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

Tawfik GM, Tieu TM, Ghozy S, Makram OM, Samuel P, Abdelaal A, et al. Speech efficacy, safety and factors affecting lifetime of voice prostheses in patients with laryngeal cancer: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15_suppl):e18031-e.

Wannemuehler TJ, Lobo BC, Johnson JD, Deig CR, Ting JY, Gregory RL. Vibratory stimulus reduces in vitro biofilm formation on tracheoesophageal voice prostheses. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(12):2752–7.

Sterne JAC, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355.

RevMan The Cochrane Collaboration %J Copenhagen TNCCTCC. Review Manager (RevMan). 5.0. 2008.

Schwarzer GJRn. meta: An R package for meta-analysis. 2007;7(3):40-45.

Google Scholar

Simms LLH. Meta-analysis versus mega-analysis: is there a difference? Oral budesonide for the maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease: Faculty of Graduate Studies, University of Western Ontario; 1998.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted (in part) at the Joint Usage/Research Center on Tropical Disease, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Nagasaki University, Japan.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt

Gehad Mohamed Tawfik

Online research Club http://www.onlineresearchclub.org/

Gehad Mohamed Tawfik, Kadek Agus Surya Dila, Muawia Yousif Fadlelmola Mohamed, Dao Ngoc Hien Tam, Nguyen Dang Kien & Ali Mahmoud Ahmed

Pratama Giri Emas Hospital, Singaraja-Amlapura street, Giri Emas village, Sawan subdistrict, Singaraja City, Buleleng, Bali, 81171, Indonesia

Kadek Agus Surya Dila

Faculty of Medicine, University of Khartoum, Khartoum, Sudan

Muawia Yousif Fadlelmola Mohamed

Nanogen Pharmaceutical Biotechnology Joint Stock Company, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Dao Ngoc Hien Tam

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Thai Binh University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Thai Binh, Vietnam

Nguyen Dang Kien

Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt

Ali Mahmoud Ahmed

Evidence Based Medicine Research Group & Faculty of Applied Sciences, Ton Duc Thang University, Ho Chi Minh City, 70000, Vietnam

Nguyen Tien Huy

Faculty of Applied Sciences, Ton Duc Thang University, Ho Chi Minh City, 70000, Vietnam

Department of Clinical Product Development, Institute of Tropical Medicine (NEKKEN), Leading Graduate School Program, and Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Nagasaki University, 1-12-4 Sakamoto, Nagasaki, 852-8523, Japan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

NTH and GMT were responsible for the idea and its design. The figure was done by GMT. All authors contributed to the manuscript writing and approval of the final version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nguyen Tien Huy .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:.

Figure S1. Risk of bias assessment graph of included randomized controlled trials. (TIF 20 kb)

Additional file 2:

Figure S2. Risk of bias assessment summary. (TIF 69 kb)

Additional file 3:

Figure S3. Arthralgia results of random effect meta-analysis using R meta package. (TIF 20 kb)

Additional file 4:

Figure S4. Arthralgia linear regression test of funnel plot asymmetry using R meta package. (TIF 13 kb)

Additional file 5:

Table S1. PRISMA 2009 Checklist. Table S2. Manipulation guides for online database searches. Table S3. Detailed search strategy for twelve database searches. Table S4. Baseline characteristics of the patients in the included studies. File S1. PROSPERO protocol template file. File S2. Extraction equations that can be used prior to analysis to get missed variables. File S3. R codes and its guidance for meta-analysis done for comparison between EBOLA vaccine A and placebo. (DOCX 49 kb)

Additional file 6:

Data S1. Extraction and quality assessment data sheets for EBOLA case example. (XLSX 1368 kb)

Additional file 7:

Data S2. Imaginary data for EBOLA case example. (XLSX 10 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Tawfik, G.M., Dila, K.A.S., Mohamed, M.Y.F. et al. A step by step guide for conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis with simulation data. Trop Med Health 47 , 46 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-019-0165-6

Download citation

Received : 30 January 2019

Accepted : 24 May 2019

Published : 01 August 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-019-0165-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Tropical Medicine and Health

ISSN: 1349-4147

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Literature Reviews

- Getting started

What is a literature review?

Why conduct a literature review, stages of a literature review, lit reviews: an overview (video), check out these books.

- Types of reviews

- 1. Define your research question

- 2. Plan your search

- 3. Search the literature

- 4. Organize your results

- 5. Synthesize your findings

- 6. Write the review

- Artificial intelligence (AI) tools

- Thompson Writing Studio This link opens in a new window

- Need to write a systematic review? This link opens in a new window

Contact a Librarian

Ask a Librarian

Definition: A literature review is a systematic examination and synthesis of existing scholarly research on a specific topic or subject.

Purpose: It serves to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of knowledge within a particular field.

Analysis: Involves critically evaluating and summarizing key findings, methodologies, and debates found in academic literature.

Identifying Gaps: Aims to pinpoint areas where there is a lack of research or unresolved questions, highlighting opportunities for further investigation.

Contextualization: Enables researchers to understand how their work fits into the broader academic conversation and contributes to the existing body of knowledge.

tl;dr A literature review critically examines and synthesizes existing scholarly research and publications on a specific topic to provide a comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge in the field.

What is a literature review NOT?

❌ An annotated bibliography

❌ Original research

❌ A summary

❌ Something to be conducted at the end of your research

❌ An opinion piece

❌ A chronological compilation of studies

The reason for conducting a literature review is to:

Literature Reviews: An Overview for Graduate Students

While this 9-minute video from NCSU is geared toward graduate students, it is useful for anyone conducting a literature review.

Writing the literature review: A practical guide

Available 3rd floor of Perkins

Writing literature reviews: A guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences

Available online!

So, you have to write a literature review: A guided workbook for engineers

Telling a research story: Writing a literature review

The literature review: Six steps to success

Systematic approaches to a successful literature review

Request from Duke Medical Center Library

Doing a systematic review: A student's guide

- Next: Types of reviews >>

- Last Updated: May 17, 2024 8:42 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.duke.edu/litreviews

Services for...

- Faculty & Instructors

- Graduate Students

- Undergraduate Students

- International Students

- Patrons with Disabilities

- Harmful Language Statement

- Re-use & Attribution / Privacy

- Support the Libraries

How-to conduct a systematic literature review: A quick guide for computer science research

Affiliations.

- 1 Faculty of Engineering, Mondragon University.

- 2 Design Innovation Center(DBZ), Mondragon University.

- PMID: 36405369

- PMCID: PMC9672331

- DOI: 10.1016/j.mex.2022.101895

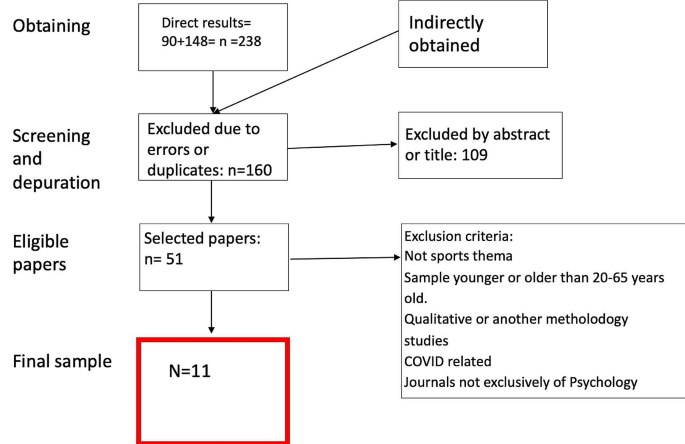

Performing a literature review is a critical first step in research to understanding the state-of-the-art and identifying gaps and challenges in the field. A systematic literature review is a method which sets out a series of steps to methodically organize the review. In this paper, we present a guide designed for researchers and in particular early-stage researchers in the computer-science field. The contribution of the article is the following:•Clearly defined strategies to follow for a systematic literature review in computer science research, and•Algorithmic method to tackle a systematic literature review.

Keywords: Systematic literature reviews; computer science; doctoral studies; literature reviews; research methodology.

© 2022 The Author(s).

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.8(11); 2016 Nov

How to Conduct a Systematic Review: A Narrative Literature Review

Nusrat jahan.

1 Psychiatry, Mount Sinai Chicago

Sadiq Naveed

2 Psychiatry, KVC Prairie Ridge Hospital

Muhammad Zeshan

3 Department of Psychiatry, Bronx Lebanon Hospital Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Bronx, NY

Muhammad A Tahir

4 Psychiatry, Suny Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY

Systematic reviews are ranked very high in research and are considered the most valid form of medical evidence. They provide a complete summary of the current literature relevant to a research question and can be of immense use to medical professionals. Our goal with this paper is to conduct a narrative review of the literature about systematic reviews and outline the essential elements of a systematic review along with the limitations of such a review.

Introduction and background

A literature review provides an important insight into a particular scholarly topic. It compiles published research on a topic, surveys different sources of research, and critically examines these sources [ 1 ]. A literature review may be argumentative, integrative, historical, methodological, systematic, or theoretical, and these approaches may be adopted depending upon the types of analysis in a particular study [ 2 ].

Our topic of interest in this article is to understand the different steps of conducting a systematic review. Systematic reviews, according to Wright, et al., are defined as a “review of the evidence on a clearly formulated question that uses systematic and explicit methods to identify, select and critically appraise relevant primary research, and to extract and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review” [ 3 ]. A systematic review provides an unbiased assessment of these studies [ 4 ]. Such reviews emerged in the 1970s in the field of social sciences. Systematic reviews, as well as the meta-analyses of the appropriate studies, can be the best form of evidence available to clinicians [ 3 ]. The unsystematic narrative review is more likely to include only research selected by the authors, which introduces bias and, therefore, frequently lags behind and contradicts the available evidence [ 5 ].

Epidemiologist Archie Cochrane played a vital role in formulating the methodology of the systematic review [ 6 ]. Dr. Cochrane loved to study patterns of disease and how these related to the environment. In the early 1970s, he found that many decisions in health care were made without reliable, up-to-date evidence about the treatments used [ 6 ].

A systematic review may or may not include meta-analysis, depending on whether results from different studies can be combined to provide a meaningful conclusion. David Sackett defined meta-analysis as a “specific statistical strategy for assembling the results of several studies into a single estimate” [ 7 - 8 ].

While the systematic review has several advantages, it has several limitations which can affect the conclusion. Inadequate literature searches and heterogeneous studies can lead to false conclusions. Similarly, the quality of assessment is an important step in systematic reviews, and it can lead to adverse consequences if not done properly.

The purpose of this article is to understand the important steps involved in conducting a systematic review of all kinds of clinical studies. We conducted a narrative review of the literature about systematic reviews with a special focus on articles that discuss conducting reviews of randomized controlled trials. We discuss key guidelines and important terminologies and present the advantages and limitations of systematic reviews.

Narrative reviews are a discussion of important topics on a theoretical point of view, and they are considered an important educational tool in continuing medical education [ 9 ]. Narrative reviews take a less formal approach than systematic reviews in that narrative reviews do not require the presentation of the more rigorous aspects characteristic of a systematic review such as reporting methodology, search terms, databases used, and inclusion and exclusion criteria [ 9 ]. With this in mind, our narrative review will give a detailed explanation of the important steps of a systematic review.

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) checklist