Review of Literature: Inclusive Education

This brief review of relevant literature on inclusive education forms a component of the larger Inclusive School Communities Project: Final Evaluation Report delivered by the Research in Inclusive and Specialised Education (RISE) team to JFA Purple Orange in October, 2020.

Suggested citation for full evaluation report:

Jarvis, J. M., McMillan, J. M., Bissaker, K., Carson, K. L., Davidson, J., & Walker, P. M. (2020). Inclusive School Communities Project: Final Evaluation Report. Research in Inclusive and Specialised Education (RISE), Flinders University.

https://sites.flinders.edu.au/rise

Introduction

Inclusive education has featured prominently in worldwide educational discourse and reform efforts over the past 30 years (Berlach & Chambers, 2011; Forlin, 2006). Inclusive schools are critical to providing a strong foundation for young people with disabilities to access, participate in and contribute to their communities and lead fulfilling lives (Hehir et al., 2016). Schools also represent a key condition for the development of thriving, inclusive communities for all citizens. Yet, as reflected in submissions to the current Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability, and consistent with recent South Australian reports (Parliament of South Australia, 2017; Walker, 2017), many students living with disability (and their families) continue to report negative experiences of education. While progress has been made, traditional educational structures and practices often run counter to inclusive goals (Slee, 2013), and inconsistencies occur between theory and policy and the implementation of inclusive principles and practices in schools (Carrington & Elkins, 2002; Graham & Spandagou, 2011). In addition, both preservice and practicing teachers consistently report feeling underprepared to teach students with disabilities and special educational needs (Jarvis, 2019; OECD, 2019).

Despite legislation and policy imperatives related to inclusive education, there remains a lack of consensus in the field about the definition of inclusion and associated models of inclusive practice (Ainscow & Sandill, 2010; Kinsella, 2020). Multiple conceptualisations of inclusion and theoretical approaches to fostering inclusion in schools may contribute to confusion and uncertainty for educators and policymakers. With schools facing growing accountability and teachers expected to educate an increasingly diverse student population (Anderson & Boyle, 2015), it is vital that the concept of inclusive education is demystified for practitioners. Against this backdrop, initiatives such as the Inclusive School Communities (ISC) project that aim to deepen understandings of inclusion and increase the capacity of school communities to provide an inclusive education, are particularly important.

Inclusive Education

Inclusive education is based on a philosophy that stems from principles of social justice, and is primarily concerned with mitigating educational inequalities, exclusion, and discrimination (Anderson & Boyle, 2015; Booth, 2012; Waitoller & Artiles, 2013). Although inclusion was originally concerned with ‘disability’ and ‘special educational needs’ (Ainscow et al., 2006; Van Mieghem et al., 2020), the term has evolved to embody valuing diversity among all students, regardless of their circumstances (e.g., Carter & Abawi, 2018; Thomas, 2013). Among interpretations of inclusion, common themes include fairness, equality, respect, diversity, participation, community, leadership, commitment, shared vision, and collaboration (Booth, 2012; McMaster, 2015). The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), to which Australia is a signatory, defines inclusive education as:

. . . a process of systemic reform embodying changes and modifications in content, teaching methods, approaches, structures and strategies in education to overcome barriers with a vision serving to provide all students of the relevant age range with an equitable and participatory learning experience and environment that best corresponds to their requirements and preferences. (United Nations, 2016, para 11)

Consistent with this definition, inclusive education now generally refers to the process of addressing the learning needs of all students, through ensuring participation, achievement growth, and a sense of belonging, enabling all students to reach their full potential (Anderson & Boyle, 2015; Booth, 2012; Stegemann & Jaciw, 2018). Inclusion is concerned with identifying and removing potential barriers to presence (attendance, access), meaningful participation, growth from an individual starting point, and feelings of connectedness and belonging for all students and community members, with a focus on those at particular risk of marginalisation or exclusion (Ainscow et al., 2006; Forlin et al., 2013).

Critically, the view of inclusion described above moves beyond considerations of the physical placement of a student in a particular setting or grouping configuration. That is, while physical access to a mainstream school environment is essential to maintain the rights of students living with disabilities to access education “on the same basis” as their peers (consistent with legislation and human rights principles), it is not sufficient to ensure inclusion. Rather, inclusion can be considered a multi-faceted approach involving processes, practices, policies and cultures at all levels of a school and system (Booth & Ainscow, 2011). Inclusive education is responsive to each child and promotes flexibility, rather than expecting the child to change in order to ‘fit’ rigid schooling structures. The latter approach reflects integration, and inclusion is also inconsistent with segregation, in which children with disabilities are routinely educated separately from others.

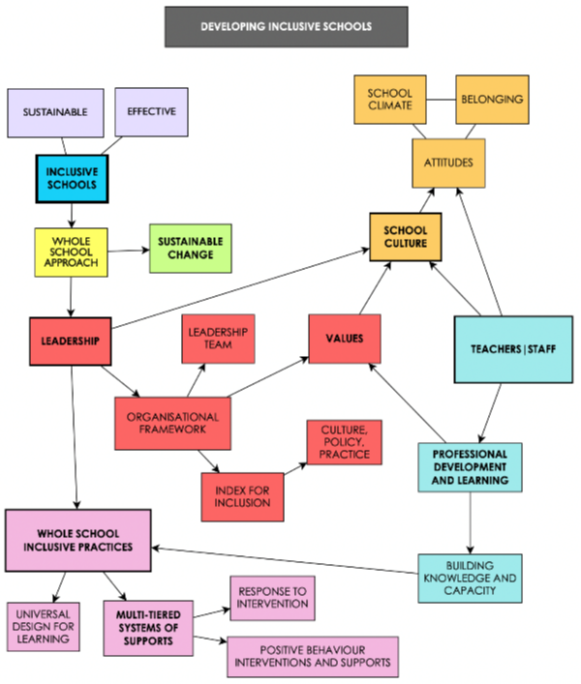

Considerable research has focused on the implementation of inclusive school processes, practices and cultures that are sustainable over time. Although a number of frameworks to achieve sustainable inclusive practice have been proposed, key elements are consistent across approaches and well supported by research (Booth & Ainscow 2011; Azorín & Ainscow, 2020). These interconnected elements are summarised in Figure 1 and considered fundamental to the process of achieving whole-school (and systemic) cultural change towards more inclusive ways of working. Of particular relevance to the Inclusive School Communities project are the concepts of a whole school approach, leadership, school values and culture, building staff capacity, and multi-tiered models of inclusive practice.

Inclusion as a Whole School Approach

Adopting a whole of school approach to inclusive education is fundamental to ensure efficacy and sustainability (Read et al., 2015). The process of developing inclusive schools is complex and multi-faceted, requiring time, commitment, ongoing reflection, and sustained effort. For inclusion to truly take root in schools, changes must be made from the inside out; a strong foundation must be built from inclusive school values, committed leadership, and shared vision amongst staff to support whole school structural reforms to policy, pedagogy, and practice (Ekins & Grimes, 2009). Whilst challenging, “it is necessary to unsettle default modes of operation” in schools (Johnston & Hayes, 2007, p.376), as inclusive education requires new, more efficient and effective ways of supporting student participation and achievement. This is made possible by implementing flexible, planned whole school support structures, such as multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS), where teachers work collaboratively with specialist staff to identify, monitor, and support students requiring varying levels and types of intervention at different times, and for different purposes (Sailor, 2017; Witzel & Clarke, 2015). This contrasts to the more traditional, ‘categorical’ and segregated approach of general educators referring identified students with additional needs to special educators, to devise and administer further education in isolation from the regular classroom (Sailor, 2017).

Figure 1. Interconnected elements in sustainable inclusive education, derived from research.

Even at the classroom level, inclusive planning and teaching practices must be supported by school policies, practices, and culture in order to be sustainable (Sailor, 2017). Barriers to inclusive classroom practice can include lack of effective professional learning and support for teachers; teachers’ lack of willingness to include students with particular needs; attitudes that are inconsistent with inclusive practices; teacher education that fails to address concerns about inclusion; and, a lack of accountability for the implementation of inclusive teaching practices (Forlin & Chambers, 2011; Forlin et al., 2008; van Kraayenoord et al., 2014). Addressing each of these relies on targeted, coordinated support. The complexity of embedding inclusive practices such as differentiated instruction or Universal Design for Learning (UDL) into classroom work is often underestimated, and these practices have the greatest chance of becoming embedded when they are reinforced by a shared vision and collaborative effort (McMaster, 2013; Sailor, 2015; Tomlinson & Murphy, 2017).

Sustainable, whole school change cannot be achieved via focus on a single element of inclusion in isolation, as components do not function in isolation. Rather, the core elements of inclusion including leadership, school culture, building staff capacity, and inclusive practices are parts of an interdependent system. Hence, key elements of inclusion must be considered collectively and accounted for in advanced planning to ensure they function harmoniously and are integrated into the developing inclusive fabric of the school (Alborno & Gaad, 2014).

Leadership for Inclusion

The importance of leadership for determining the success of school reforms or changes to practice is well established in the literature (McMaster & Elliot, 2014; Poon-McBrayer & Wong, 2013). Becoming a more inclusive school often requires significant shifts in school values, culture, practices, and organisational systems; thus, leadership is critical to ensuring sustainable inclusive change in schools (Ainscow & Sandill, 2010; McMaster, 2015; Poon-McBrayer & Wong, 2013). School leaders are highly influential figures whose values, beliefs, and actions directly affect the culture of the school, expectations of staff, and school operations (Slater, 2012; Wong & Cheung, 2009). It is critical that school leaders are committed to embodying inclusive principles, establishing and modelling a standard of behaviour that promotes the development of inclusion within the school community.

Organisational change on the scale often required for inclusion requires leadership across multiple levels (Jarvis et al., 2016; Tomlinson et al., 2008). It is likely to be most effective when facilitated through models of distributed leadership across roles and levels within a school, and when the case for change is underpinned by a broader, shared vision specifically related to student outcomes (Harris, 2013). Research has established the relationship between distributed leadership practices and the implementation of effective, inclusive school practices (Miškolci et al., 2016; Mullick et al., 2013; Robinson et al., 2008; Sharp et al., 2020). Leaders should consider utilising inclusive styles of management, replacing hierarchical structures with leadership teams (Ainscow & Sandill, 2010; McMaster, 2015). Effective school leadership enables shared responsibility, vision, and consistency within the school community, which is vital for the successful implementation of inclusion (Poon- McBrayer & Wong, 2013).

Fostering Inclusive School Cultures

Developing an inclusive school culture is a fundamental component of developing sustainable inclusion in schools (Dyson et al., 2004; McMaster, 2013). The culture of a school is made up of the shared values, attitudes, and beliefs of the school community (Booth, 2012). Transitioning to a truly inclusive culture requires close attention to attitudes and general support of the inclusive values being adopted, particularly by staff, but also by students and the broader school community (Dyson et al., 2004; Forlin & Chambers, 2011).

A whole school approach to inclusion prompts a school to reflect on and embrace values based on inclusive principles, such as equality, diversity, and respect. This process cannot be imposed, but should be a collaborative exercise with school leaders and staff, to ensure any pedagogical philosophies or practices based on outdated ideas or past assumptions are not operating by default (Johnston & Hayes, 2007; Schein, 2004). Evaluating and redefining existing school values also requires professional learning, to facilitate a collective reconceptualisation of inclusion specific to the unique context of the school; the meaning, aims, and expectations of inclusion must be clarified for the school community, to encourage a shared understanding, vision, and responsibility for supporting the inclusive changes unfolding within the school (Horrocks et al., 2008; Symes & Humphrey, 2011). Finally, it is vital that school policies and practices are regularly revised, to ensure that they reinforce the inclusive values and culture of the school; otherwise, they can act as a potential barrier to the development of sustainable whole school inclusion (Dybvik, 2004; McMaster, 2013).

Building Teachers’ Capacity for Inclusive Practice

Building the knowledge and capacity of teachers and other school staff is crucial to developing sustainable inclusion in schools. The evolution of an inclusive school culture depends on aligning the attitudes and behaviour of staff (McMaster, 2015). Teachers must be knowledgeable about how inclusive education has progressed over time, particularly how the meaning of inclusion has changed and what it means in their school context. Understanding the concepts and values behind inclusion can help teachers appreciate its significance, prompting reflection of their own practice and how they see their students (Anderson & Boyle, 2015; Skidmore, 2004). This can allow any unhelpful assumptions or beliefs that may have been unconsciously informing their teaching practice, particularly in relation to students living with disability, to be challenged and revised (Ashby, 2012; Ashton & Arlington, 2019).

While attention to attitudes, values, and broad understandings is fundamental, the goals of inclusion will only be achieved when principles are consistently enacted in daily classroom practice. At the classroom level, inclusion relies on teachers’ willingness and capacity to apply evidence-informed inclusive practices, such as Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and Differentiated Instruction (Van Mieghem et al., 2020). UDL is a planning framework for learning activities designed to maximise curriculum accessibility for all students by offering multiple opportunities for engagement, representation, and action and expression (CAST, 2018; Sailor, 2015). Differentiated Instruction (DI) is a holistic framework of interdependent principles and practices that enables teachers to design learning experiences to address variation in students’ readiness, interests and learning preferences (Tomlinson, 2014). UDL is primarily focused on inclusive task design, although the model has been expanded in recent years to include greater attention to pedagogy. Differentiation encompasses elements of planning (clear, concept-based learning objectives; formative assessment to inform proactive decision-making for diverse students), teaching (strategies to differentiate by readiness, interest and learning preference; ensuring respectful tasks and ‘teaching up’), and learning environment (flexible grouping, classroom management, establishing an inclusive culture) (Jarvis, 2015; Tomlinson, 2014).

The application of UDL and DI principles and practices by skilled teachers enables diverse students to access curriculum content in multiple ways (Kozik et al., 2009; McMaster, 2013), at appropriate levels of challenge and support to ensure learning growth, and in ways that support motivation, engagement, and feelings of connection and belonging (Beecher & Sweeney, 2008; Callahan et al., 2015; van Kraayenoord, 2007; Stegemann & Jaciw, 2018). These complementary frameworks apply to all students and define general, flexible classroom practices that also reduce the need for individualised adjustments for students with identified disabilities and specialised learning needs. However, in inclusive classrooms, teachers must also develop the knowledge and skills to make and implement reasonable adjustments and accommodations that enable students with identified disabilities and more complex needs to engage with curriculum and assessment ‘on the same basis’ as their peers, as defined within the Disability Standards for Education (Davies et al., 2016).

While inclusive teaching and classroom practices are non-negotiable, the challenge for some teachers to master the necessary skills and achieve the significant shift away from traditional teaching practices is often underestimated (Dixon et al., 2014; Tomlinson & Murphy, 2015). It is well-documented that teachers often find it difficult to apprehend both the conceptual and practical tools of DI and to embed differentiated practices into their daily work (Dack, 2019), particularly when they are not adequately resourced or supported to do so (Black-Hawkins & Florian, 2012; Brigandi et al., 2019; Fuchs et al., 2010; Mills et al, 2014). Perhaps related to teachers’ perceived lack of competence and confidence, the past 5-10 years have seen an enormous increase in the employment of teacher aides to work alongside students with disabilities in mainstream classrooms, despite limited evidence for its effectiveness and often in the context of inadequate planning and oversight (e.g., Sharma & Salend, 2016).

Engagement in targeted professional learning (PL) is fundamental to supporting the shift towards inclusive teaching. Yet, traditional approaches to PL have been criticised for a lack of systematic evaluation and inadequate adherence to principles of effectiveness (Avalos, 2011; Merchie et al., 2018). Research on effective professional learning for teachers has established common principles and practices that are associated with changes in practice, and these also align with teachers’ stated preferences (Walker et al., 2018). These include:

- professional learning is embedded in teachers’ own work contexts, and requires teachers to engage with content that is highly relevant to their daily practice, and closely linked to student learning (Desimone, 2009; Easton, 2008; Spencer, 2016; Van den Bergh et al., 2014);

- professional learning enables teachers to learn together with colleagues, such as in communities of practice (Gore et al., 2017; Voelkel & Chrispeels, 2017);

- professional learning activities are supported by robust school leadership and linked to broader school values and goals (Carpenter, 2015; Frankling et al., 2017; Sharp et al., 2020; Tomlinson et al., 2008; Whitworth & Chiu, 2015);

- professional learning is provided over extended periods, is led by facilitators with expert knowledge, and includes timely follow up activities such as mentoring and coaching to embed changes in practice (Desimone & Pak, 2017; Grierson & Woloshyn, 2013; Tomlinson & Murphy, 2015).

Multi-tiered Approaches to Whole School Inclusive Practice

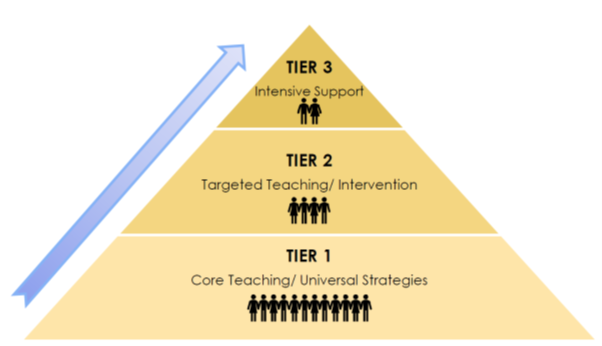

Multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) is an overarching term for a whole school inclusive framework that can be used to structure the flexible, timely distribution of resources to support students depending on their level of need (Sailor, 2017). As reflected in the generic depiction of MTSS in Figure 2, models generally utilise three tiers of intervention and teaching, where the intensity of the support is increased with each level or tier (McLeskey et al, 2014; Witzel & Clarke, 2015). Tier 1 includes core differentiated instruction and universal, evidence-based strategies for support that all students in the class receive. Tier 2 provides additional, targeted support to certain students for a specified purpose and period of time, usually in a small group format, while Tier 3 represents the most intensive and individualised support (Webster, 2016). The MTSS approach requires assessing all students regularly to assist in the early identification of needs requiring additional support, to enable prompt delivery of targeted interventions (McLeskey et al., 2014). MTSS is concerned with supporting the holistic development of students, by targeting their academic progress, behaviour, and socio-emotional well- being (McMillan & Jarvis, 2017).

When implemented with fidelity, MTSS is an effective whole school inclusive framework as teachers, therapists, and other support staff work collaboratively to assess, monitor, and plan interventions to support students (Sailor, 2017). Student progress is frequently monitored and data are evaluated by the support team to determine whether alternative interventions are required. MTSS additionally encourages the use of evidence-based practices to be implemented across the tiers of support. Some common examples of MTSS include Response to Intervention (RTI) and Positive Behaviour Interventions and Supports (PBIS) (Webster, 2016). RTI is focused on supporting students academically, while PBIS is concerned with emphasising behavioural expectations in a positive manner, naturally supporting the social and emotional development of students. MTSS models have also been applied in whole-school mental health promotion, prevention and intervention (McMillan & Jarvis, 2017) and inclusive approaches to academic talent development for more advanced students (Jarvis, 2017).

MTSS approaches to contemporary inclusive practice stand in contrast to traditional, categorical models whereby students were either ‘in’ or ‘out’ of special education services. The focus is on determining and responding to what students need when they need it, as opposed to focusing on a specific diagnosis or inflexible program options. In the MTSS framework, the tiers do not represent students or their placement, but the flexible suite of supports and interventions that may be provided. The implementation of MTSS approaches fundamentally reconceptualises the role of the classroom teacher, who must work collaboratively with specialist staff and other professionals to define and address individual student needs in ongoing ways, rather than relying on a specialist teacher or even a teacher aide to take responsibility for the education of students with identified special needs. While MTSS requires substantial changes to school operations (and must therefore be supported by leadership and culture in deliberate, coordinated ways), the general framework provides an organisation and structure to support the development of sustainable, contemporary inclusive schools (McLeskey et al., 2014).

Figure 2. Multi-tiered System of Supports (MTSS) framework.

Conclusion

Ultimately, developing sustainable and effective inclusion in schools is a challenging but worthwhile undertaking, requiring shared vision, commitment, ongoing reflection, and patience. Changes in practice, particularly in teachers’ daily planning and pedagogy, take time and will be supported by ongoing, well designed and embedded professional learning in the context of strong leadership and an inclusive school culture. By utilising a whole school approach, key areas including leadership, school values and culture, building staff capacity, and coordinated frameworks for inclusive practice, can be considered collectively and planned for in advance.

References

Ainscow, M., & Sandill, A. (2010). Developing inclusive education systems: The role of organizational cultures and leadership. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14 (4), 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802504903

Ainscow, M., Booth, T., & Dyson, A. (2006). Improving Schools, Developing Inclusion. Routledge.

Alborno, N., & Gaad, E. (2014). Index for Inclusion: A framework for school review in the United Arab Emirates. British Journal of Special Education, 41 (3), 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12073

Anderson, J., & Boyle, C. (2015). Inclusive education in Australia: Rhetoric, reality and the road ahead. Support for Learning, 30 (1), 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12074

Ashby, C. (2012). Disability studies and inclusive teacher preparation: A socially just path for teacher education. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 37 (2), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F154079691203700204

Ashton, J. R., & Arlington, H. (2019). My fears were irrational: Transforming conceptions of disability in teacher education through service learning. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 15 (1), 50–81.

Askell-Williams, H., & Koh, G. (2020). Enhancing the sustainability of school improvement initiatives. School Effectiveness and School Improvement. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2020.1767657

Avalos, B. (2011). Teacher professional development in teaching and teacher education over ten years. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.007

Beecher, M., & Sweeney, S. M. (2008). Closing the achievement gap with curriculum enrichment and differentiation: One school’s story. Journal of Advanced Academics, 19 (3), 502–530. https://doi.org/10.4219/jaa-2008-815

Berlach, R. G., & Chambers, D. J. (2011). Interpreting inclusivity: An endeavour of great proportions. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15, 529–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110903159300

Black-Hawkins, K. & Florian, L. (2012). Classroom teachers’ craft knowledge of their inclusive practice. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 8 (5), 567–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2012.709732

Booth, T. (2012). Creating welcoming cultures: The index for inclusion. Race Equality Teaching, 30 (2), 19–21. http://doi.org/10.18546/RET.30.2.07

Booth, T., & Ainscow, M. (2011). Index for Inclusion: developing learning and participation in schools (3rd ed.). Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education. http://www.csie.org.uk/resources/inclusion-index-explained.shtml

Brigandi, C., Gibson, C. M., & Miller, M. (2019). Professional development and differentiated instruction in an elementary school pull-out program: A gifted education case study. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 42 (4), 362–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353219874418

Callahan, C. M., Moon, T. R., Oh, S., Azano, A. P., & Hailey, E. P. (2015). What works in gifted education: Documenting the effects of an integrated curricular/instructional model for gifted students. American Education Research Journal, 52, 137–167. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831214549448

Carpenter, D. (2015). School culture and leadership of professional learning communities. International Journal of Educational Management, 29 (5), 682–694. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-04-2014-0046

Carrington, S., & Elkins, J. (2002). Bridging the gap between inclusive policy and inclusive culture in secondary schools. Support for Learning, 17 (2), 51–57.

Carter, S., & Abawi, L. (2018). Leadership, inclusion, and quality education for all. Australasian Journal of Special and Inclusive Education, 42 (1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/jsi.2018.5

CAST. (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 2.2. http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Davies, M., Elliott, S., & Cumming, J. (2016). Documenting support needs and adjustment gaps for students with disabilities: Teacher practices in Australian classrooms and on national tests. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20 (12), 1252–1269. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2016.1159256

Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38 (3),181–199. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X08331140

Desimone, L. M., & Pak, K. (2017). Instructional coaching as high-quality professional development. Theory Into Practice, 56 (1), 312. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2016.1241947

Dixon, F. A., Yssel, N., McConnell, J. A., & Hardin, T. (2014). Differentiated instruction, professional development and teacher efficacy. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 37 (2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353214529042

Dybvik, A. C. (2004). Autism and the inclusion mandate: What happens when children with severe disabilities like autism are taught in regular classrooms? Daniel knows. Education Next, 4 (1), 42–49.

Dyson, A., Farrell, P., Polat, F., Hutcheson, G., & Gallanaugh, F. (2004). Inclusion and pupil achievement. Department for Education and Skills.

Easton, L. B. (2008). From professional development to professional learning. Phi Delta Kappan, 89, 755–761. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172170808901014

Ekins, A., & Grimes, P. (2009). Inclusion: Developing an Effective Whole School Approach. McGraw Hill Open University Press.

Forlin, C. (2006). Inclusive education in Australia ten years after Salamanca. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 21 (3), 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173415

Forlin, C., & Chambers, D. (2011). Teacher preparation for inclusive education: Increasing knowledge but raising concerns. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 39 (1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2010.540850

Forlin, C., Chambers, D. J., Loreman, T., Deppler, J., & Sharma, U. (2013). Inclusive education for students with disability: A review of the best evidence in relation to theory and practice. The Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth. https://www.aracy.org.au/publicationsresources/command/download_file/id/246/filename/Inclusive_education_for_students_with_disability_-_A_review_of_the_best_evidence_in_relation_to_theory_and_practice.pdf73

Forlin, C., Keen, M., & Barrett. E. (2008). The concerns of mainstream teachers: Coping with inclusivity in an Australian context. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 55 (3), 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/10349120802268396

Frankling, T. W., Jarvis, J. M. & Bell. M. R. (2017). Leading secondary teachers’ understandings and practices of differentiation through professional learning. Leading and Managing, 23 (2), 72–86.

Fuchs, D., Fuchs, L. S., & Stecker, P. M. (2010). The ‘blurring’ of special education in a new continuum of general education placements and services. Exceptional Children, 76 (3), 301–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291007600304

Gore, J., Lloyd, A., Smith, M., Bowe, J., Ellis, H., & Lubans, D. (2017). Effects of professional development on the quality of teaching: Results from a randomised controlled trial of Quality Teaching Rounds. Teaching and Teacher Education, 68, 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.08.007

Graham, L., & Spandagou, I. (2011). From vision to reality: Views of primary school principals on inclusive education in New South Wales, Australia. Disability & Society, 26 (2), 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2011.544062

Grierson, A. L., & Woloshyn, V. E. (2013). Walking the talk: Supporting teachers’ growth with differentiated professional learning. Professional Development in Education, 39 (3), 401–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2012.763143

Guskey, T. R. (2000). Evaluating professional development. Corwin Press

Harris, A. (2013). Distributed leadership: Friend or foe? Educational Management, Administration & Leadership, 4 (5), 545–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213497635

Hehir, T., Pascucci, S., & Pascucci, C. (2016). A summary of the evidence on inclusive education, Instituto Alana, 2. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED596134.pdf

Horrocks, J. L., White, G., & Roberts, L. (2008). Principals' attitudes regarding inclusion of children with autism in Pennsylvania public schools. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1462–1473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0522-x

Jarvis, J. M. (2015). Inclusive Classrooms and Differentiation. In N. Weatherby-Fell (Ed.), Learning to Teach in the Secondary School (pp. 154–171). Cambridge University Press.

Jarvis, J. M. (2019). Most Australian teachers feel unprepared to teach students with special needs. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/most-australian-teachers-feel-unpreparedto-teach-students-with-special-needs-119227

Jarvis, J. M., (2017). Supporting diverse gifted students. In M. Hyde, L. Carpenter & S. Dole (Eds.), Diversity, Inclusion and Engagement (3rd ed., pp. 308–329). Oxford University Press.

Johnston, K., & Hayes, D. (2007). Supporting students’ success at school through teacher professional learning: The pedagogy of disrupting the default modes of schooling. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 11 (3), 371–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110701240666

Kinsella, W. (2020). Organising inclusive schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24 (12), 1340–1356. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1516820

Kozik, P., Cooney, B., Vinciguerra, S., Gradel, K., & Black, J. (2009). Promoting inclusion in secondary schools through appreciative inquiry. American Secondary Education, 38 (1), 77–91.

McLeskey, J., Waldron, N. L., Spooner, F., & Algozzine, B. (Eds.). (2014). Handbook of effective inclusive schools: Research and practice. Taylor & Francis.

McMaster, C. (2013). Building inclusion from the ground up: A review of whole school re-culturing programmes for sustaining inclusive change. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 9 (2), 1–24.

McMaster, C. (2015). Inclusion in New Zealand: The potential and possibilities of sustainable inclusive change through utilising a framework for whole school development. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 50 (2), 239–253.

McMaster, C., & Elliot, W. (2014). Leading inclusive change with the Index for Inclusion: Using a framework to manage sustainable professional development. Journal of Educational Leadership, Policy and Practice, 29 (1), 82–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-015-0010-3

McMillan, J., & Jarvis, J. M. (2017). Supporting mental health and well-being: Promotion, prevention and intervention. In M. Hyde, L. Carpenter & S. Dole (Eds.), Diversity, inclusion and engagement (3rd ed., pp. 65–392). Oxford University Press.

Merchie, E., Tuytens, M., Devos, G., & Vanderlinde, R. (2018). Evaluating teachers’ professional development initiatives: Towards an extended evaluative framework. Research Papers in Education, 33 (2), 143–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2016.1271003

Mills, M., Monk, S., Keddie, A., Renshaw, P., Christie, P., Geelan, D. & C. Gowlett, C. (2014). Differentiated learning: From policy to classroom. Oxford Review of Education, 40 (3), 331–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2014.911725

Miškolci, J., Armstrong, D., & Spandagou, I. (2016). Teachers' perceptions of the relationship between inclusive education and distributed leadership in two primary schools in Slovakia and New South Wales (Australia). Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 18 (2), 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1515/jtes-2016-001

Mullick, J., Sharma, U., & Deppeler, J. (2013). School teachers' perception about distributed leadership practices for inclusive education in primary schools in Bangladesh. School Leadership & Management, 33 (2), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2012.723615

OECD (2019). TALIS 2018 Results (Volume I): Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/1d0bc92a-en.

Parliament of South Australia. (2017). Report of the select committee on access to the South Australian Education System for students with a disability. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2017-05/apo-nid94396.pdf

Poon-McBrayer, K., & Wong, P. (2013). Inclusive education services for children and youth with disabilities: Values, roles and challenges of school leaders. Children and Youth Services Review, 35 (9), 1520–1525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.06.009

Read, K., Aldridge, J., Ala’i, K., Fraser, B., & Fozdar, F. (2015). Creating a climate in which students can flourish: A whole school intercultural approach. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 11 (2), 29–44. https://doi.org/1710-2146

Robinson, V. M. J., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44 (5), 635–674. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X08321509

Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability. (2019). Issues Paper: Education and Learning. https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/system/files/2020-07/Issues-paper-Education-Learning.pdf

Sailor, W. (2015). Advances in schoolwide inclusive school reform. Remedial and Special Education, 36, 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932514555021

Sailor, W. (2017). Equity as a basis for inclusive educational systems change. The Australasian Journal of Special Education, 41 (1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/jse.2016.12

Schein, E. (2004). Organizational culture and leadership (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Sharma, U., & Salend, S. (2016). Teaching assistants in inclusive classrooms: A systematic analysis of the international research. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 41 (8), 118–134.

Sharp, K., Jarvis, J. M., & McMillan, J. M. (2020). Leadership for differentiated instruction: Teachers' engagement with on-site professional learning at an Australian secondary school. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24 (8), 901–920. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1492639

Skidmore, D. (2004). Inclusion: The dynamic of school development. McGraw-Hill Education.

Slater, C. L. (2012). Understanding principal leadership: An international perspective and a narrative approach. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 39 (2), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143210390061

Slee, R. (2013). How do we make inclusive education happen when exclusion is a political predisposition? International Journal of Inclusive Education: Making Inclusive Education Happen: Ideas for Sustainable Change, 17 (8), 895–907. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2011.602534

Spencer, E. J. (2016). Professional learning communities: Keeping the focus on instructional practice. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 52 (2), 83–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/00228958.2016.1156544

Stegemann, K., & Jaciw, A. (2018). Making it logical: Implementation of inclusive education using a logic model framework. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 16 (1), 3–18.

Symes, W., & Humphrey, N. (2011). School factors that facilitate or hinder the ability of teaching assistants to effectively support pupils with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) in mainstream secondary schools. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 11 (3), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2011.01196.x

Thomas, G. (2013). A review of thinking and research about inclusive education policy, with suggestions for a new kind of inclusive thinking. British Educational Research Journal, 39 (3), 473–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2011.652070

Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners (2nd ed.). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Tomlinson, C. A., & Murphy, M. (2015). Leading for differentiation: Growing teachers who grow kids. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Tomlinson, C.A., Brimijoin, K., & Narvaez, L. (2008). The differentiated school: Making revolutionary changes in teaching and learning. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Van Den Bergh, L., Ros, A., & Beijaard, D. (2014). Improving teacher feedback during active learning: Effects of a professional development program. American Educational Research Journal, 51 (4), 772–809. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831214531322

van Kraayenoord, C. E. (2007). School and classroom practices in inclusive education in Australia. Childhood Education, 83 (6), 390–394, https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2007.10522957

van Kraayenoord, C. E., Waterworth, D., & Brady. T. (2014). Responding to individual differences in inclusive classrooms in Australia. Journal of International Special Needs Education, 17 (2), 48–59.

Van Mieghem, A., Verschueren, K., Petry, K., & Struyf, E. (2020). An analysis of research on inclusive education: A systematic search and meta review. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 26 (6), 675–689. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1482012

Voelkel, R. H., Jr., & Chrispeels, J. H. (2017). Understanding the link between professional learning communities and teacher collective efficacy. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 28, 505–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2017.1299015

Waitoller, F. R., & Artiles, A. J. (2013). A decade of professional development research for inclusive education: A critical review and notes for a research program. Review of Educational Research, 83 (3), 319–356. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313483905

Walker, P. M., Carson, K. L., Jarvis, J. M., McMillan, J. M., Noble, A. G., Armstrong, D., . . . Palmer, C. (2018). How do educators of students with disabilities in specialist settings understand and apply the Australian Curriculum framework? Australasian Journal of Special and Inclusive Education, 42 (2), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1017/jsi.2018.13

Webster, A. (2016). Utilising a leadership blueprint to build the capacity of schools to achieve outcomes for students with autism spectrum disorder. In G. Johnson & N. Dempster (Eds.), Leadership in diverse learning contexts (pp. 109–127). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28302-9_6

Whitworth, B. A., & Chiu, J. L. (2015). Professional development and teacher change: The missing leadership link. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 26 (2), 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-014-9411-2

Inclusive School Communities Project Phone: (08) 8373 8333 Email: [email protected] Address: 104 Greenhill Road, Unley SA 5061

Advertisement

Teachers’ Beliefs About Inclusive Education and Insights on What Contributes to Those Beliefs: a Meta-analytical Study

- Meta-Analysis

- Open access

- Published: 26 August 2022

- Volume 34 , pages 2609–2660, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Charlotte Dignath ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1707-8731 1 , 2 ,

- Sara Rimm-Kaufman 3 ,

- Reyn van Ewijk 4 &

- Mareike Kunter 1 , 2

22k Accesses

27 Citations

9 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

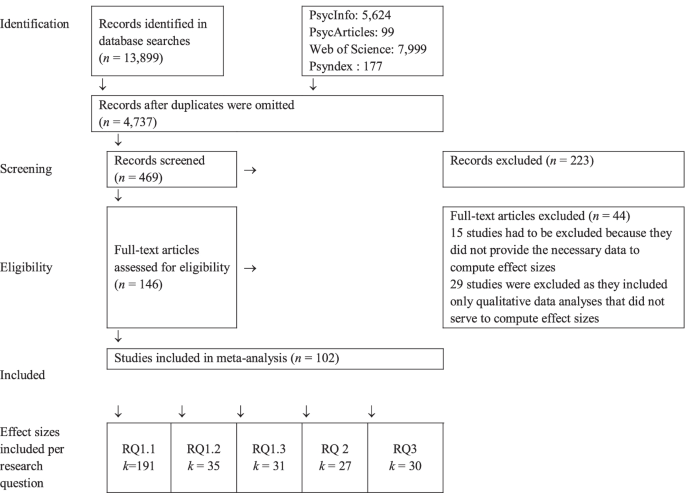

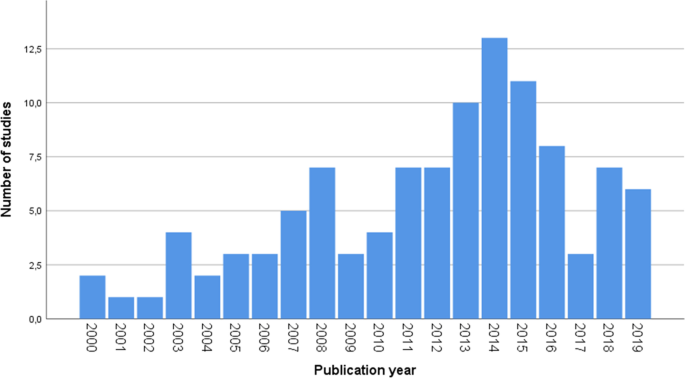

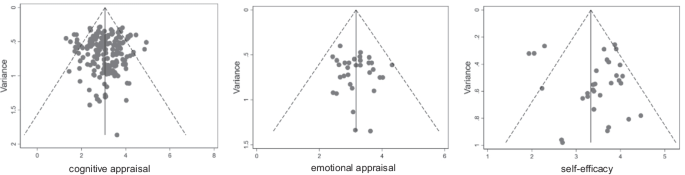

Teachers’ belief systems about the inclusion of students with special needs may explain gaps between policy and practice. We investigated three inter-related aspects of teachers’ belief systems: teachers’ cognitive appraisals (e.g., attitudes), emotional appraisal (e.g., feelings), and self-efficacy (e.g., agency to teach inclusive classrooms). To date, research in this field has produced contradictory findings, resulting in a sparse understanding of why teachers differ in their belief systems about inclusive education, and how teachers’ training experiences contribute to their development of professional beliefs. We used meta-analysis to describe the level and range of teachers’ beliefs about inclusive education, and examine factors that contribute to variation in teachers’ beliefs, namely (1) the point in teachers’ career (pre-service versus in-service), (2) training in special versus regular education, and (3) the effects of specific programs and interventions. We reviewed 102 papers (2000–2020) resulting in 191 effect sizes based on research with 40,898 teachers in 40 countries. On average, teachers’ cognitive appraisals, emotional appraisals, and efficacy about inclusion were found to be in the mid-range of scales, indicating room for growth. Self-efficacy beliefs were higher for preservice ( M = 3.69) than for in-service teachers ( M = 3.13). Teachers with special education training held more positive views about inclusion than regular education teachers ( d = 0.41). Training and interventions related to improved cognitive appraisal ( d = 0.63), emotional appraisal ( d = 0.63), and self-efficacy toward inclusive practices ( d = 0.93). The training was particularly effective in encouraging reflection of beliefs and, eventually, facilitating belief change when teachers gained practical experience in inclusive classrooms. Six key findings direct the next steps.

Similar content being viewed by others

Does Professional Development Effectively Support the Implementation of Inclusive Education? A Meta-Analysis

Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Inclusive Education: a Cross-National Exploration

Are teachers’ personal values related to their attitudes toward inclusive education? A correlational study

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Teachers’ classroom practices and how they implement educational reform account substantially for students’ academic learning and achievement (Hattie, 2009 ). The United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD ; 2006 ) and the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015 (United Nations, 2006 ) paved the way for reform toward inclusive education, and teachers play a key role in translating this reform into practice (Rouse, 2017). To implement the change towards more inclusive school systems, we must understand why some teachers use new teaching strategies while others resist inclusive reform efforts (Sutton & Wheatley, 2003 ). Identifying contributors and barriers to the implementation of inclusive education is a timely topic because inclusive education of students with special educational needs (SEN) has become one of the most significant educational reforms in countries all over the world (Savolainen et al., 2020 ).

A major driver for the development of inclusive education policies has been the right of children with SEN to be educated in mainstream schools. Yet, the likelihood of inclusive education actually occurring depends on teachers’ underlying belief systems (Lindsay, 2007 ). “Teachers’ belief systems” (Fives & Buehl, 2012 , p. 477) refer to a set of dynamic and integrated teacher views related to a certain topic that guides their perceptions, leads them to interpret incoming information and events in certain ways, and acts as an individual’s “working model of the world” (Bandura, 1977 , p. 3). The subcomponents of a teacher’s belief system are often entangled (e.g., Miesera et al., 2019 ; Woodcock & Jones, 2020 ). Knowing about teachers’ belief systems gives insights into the psychological experiences that drive teachers’ actions. Such knowledge is critical to inform teacher training (e.g., teacher preparation, professional development) that supports teachers’ implementation of reforms such as inclusive education. Using studies from across the globe and including high-, middle-, and low-income countries increases the likelihood that findings can be generalized widely.

There are numerous ways to build knowledge related to inclusive education. In this paper, we use studies from 40 countries to focus on teachers’ beliefs about inclusion as the key outcome. Yet, it seems important to acknowledge that research on teachers’ beliefs about inclusive education differs from research examining the effectiveness of inclusive education compared to other educational approaches. The latter is beyond the scope of this paper.

Researchers in education have produced a large body of work on teachers’ belief systems related to inclusive education. However, the existing research findings are contradictory and not easy to interpret. Some contradictions occur because of the wide range of beliefs teachers hold about inclusive education. Other contradictions reflect the variety of constructs studied; for instance, some work focuses on teaching approaches to inclusive education, other work focuses on thoughts about inclusive education, and still others assess teachers’ fears toward inclusive education. Given the existing contradictory information, the field needs a synthesis of research. We expect the resulting knowledge will shed light on factors that contribute to beliefs about inclusive education and inform teacher training in ways that will lead to inclusive education reform. For this reason, we conducted a meta-analysis to explain how and why teachers’ beliefs about inclusive education vary.

The goal of this article is twofold. To shed light on the variation of teachers’ beliefs about inclusive education, we investigate teachers’ belief systems regarding inclusive education and the extent to which they vary as a function of point in a career (i.e., preservice versus in-service) and teacher type (e.g., special education versus regular education). Then, we broaden the lens to understand how training and interventions provide teachers with experiences that contribute to teachers’ beliefs, such that teachers are more likely to implement inclusive practices (Forlin et al., 2014 ). To pursue these goals, first, we examine the effects of preservice teachers’ education and in-service teachers’ professional development on teachers’ beliefs on inclusive education. Second, we examine whether being a special or regular education teacher is related to teachers’ beliefs about inclusion. Third, to advance our knowledge about the malleability of inclusion-related beliefs, we examine the extent to which interventions (such as preservice courses, professional development training, and practical experiences in inclusive classrooms) moderate the effects of teacher education. We organize the literature by distinguishing between three components of beliefs—teachers’ cognitive appraisals (e.g., thoughts), emotional appraisals (e.g., feelings), and self-efficacy (e.g., agency to teach inclusive classrooms). The results provide the theoretical ground for future research on teachers’ belief systems about inclusive education reform, shed light on how teachers’ point in their career and whether they are special education versus regular teachers shape their belief systems about inclusive education reform, and provide information about what aspects of training and interventions are associated with more positive beliefs toward inclusion.

In the following section, we first describe the evidence for the implementation of the inclusive education reform and the role of teachers' beliefs in the implementation of this reform. Based on Gregoire's ( 2003 ) cognitive-affective model, we review the state of current research on teachers' belief systems and then describe factors that contribute to the development of teachers’ belief systems. Finally, we present our study and the research questions.

The Implementation and Effects of Inclusive Education

By definition, inclusive education refers to the education of all children within one classroom, irrespective of their cognitive or physiological conditions (UNESCO, 1994 ). Access to inclusive education has been viewed as a fundamental right of children with SEN and exclusion from such educational settings has been viewed as discrimination (Lindsay, 2007 ). The move toward inclusion is almost universal, and it reflects a change in values in many societies. However, there is remarkable variation in the definition and implementation of inclusive education around the world. According to UNESCO ( 2017a ), most countries have committed to the United Nations’ Convention on CRPD ; however, countries still differ substantially in terms of experience with inclusive education and the way in which inclusion is realized (O'Hanlon, 2017 ; UNESCO, 2017b ). Hence, implementing inclusive education remains a work in progress (Westwood, 2018 ). Whereas some countries, such as the USA, have been changing their educational systems to integrate students with SEN into regular education classrooms for decades, most countries worldwide are currently in the process of aligning their educational systems with the United Nations’ Convention on CRPD.

Inclusion has become a goal in many nations, but skeptics still question whether inclusion works for all children. To date, most empirical research on inclusion suggests it produces favorable outcomes. When research compares students in inclusive settings with those who remain segregated in specialized programs, the results show mostly positive effects of inclusion on academic achievement (Oh-Young & Filler, 2015 ) and student social contact (Nakken & Pijl, 2002 ), without having adverse effects (Wilberger & Palko, 2009). Moreover, research syntheses suggest that inclusive education does not lead to negative consequences for students without SEN (Kalambouka et al., 2007 ; Szumski et al., 2017 ). Nevertheless, there may be differential effects for different groups of students and types of inclusion practices (Ruijs & Peetsma, 2009 )—both of which depend on teachers’ inclusive classroom practices and, in turn, teachers’ beliefs. Before teachers take on new classroom practices to teach inclusive classrooms, they may first need to change their beliefs about inclusive education, which is a complex and cognitively demanding process (Gregoire, 2003 ). For many teachers, their existing beliefs may conflict with the underpinning philosophy of inclusive education (Wilson et al., 2016 ) and can prevent the implementation and sustained use of inclusive reform (Fox et al., 2021 ). Thus, understanding teachers’ beliefs about inclusive practices gives insights into an important precursor of whether teachers implement inclusive practices or not.

The Role of Teachers’ Belief Systems and the Implementation of Inclusive Reform

According to Gregoire’s ( 2003 ) cognitive–affective model of conceptual change, teachers’ belief systems play a major role in how comfortable teachers are with implementing reforms (Liou et al., 2019 ). If teachers think and feel positive about a set of practices, they are more likely to use those practices in the classroom (Fives & Buehl, 2012 ). Then, no conceptual change needs to take place and beliefs may stay the same (Gregoire, 2003 ). However, if a teacher’s prior beliefs and experiences are opposed to the reform approach, those beliefs and experiences may act as a barrier to implementing the reform (Fox et al., 2021 ). When teachers engage in critical appraisal, they may realize that the reform practices are actually at odds with how they have been teaching for a long time. Being confronted with a reform message that challenges a teacher’s current ideas about instruction (cognitive appraisal) can make the teacher appraise the situation as stressful, resulting in feelings of anxiety (emotional appraisal). Whether or not the teacher feels able to cope with this situation (self-efficacy) will determine whether the reform will be appraised as a challenge or a threat (Gregoire, 2003 ). Eventually, such negative appraisals can contribute to teacher burnout (Chang, 2009 ) and teacher turnover (Iancu et al., 2018 ).

Cognitive Appraisals of Inclusive Education

Cognitive appraisal refers to a person’s cognitive evaluation of an attitude object (i.e., whether it is favorable or unfavorable (Ajzen, 2002 )). More precisely, teachers’ cognitive appraisals of inclusive education include beliefs about the effectiveness of including students with diverse SEN in regular classrooms and whether inclusion is viewed positively or negatively (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002 ). This evaluation builds on teachers’ cognitive representations of inclusive education that reflect teachers’ thoughts about the costs and benefits of inclusion for classroom management, teachers’ own work, and for the students themselves (including those with and without SEN) (Forlin et al., 2010 ).

Cognitive appraisals of inclusive education affect the perception and the expectations that teachers have for their students, which can have profound consequences on their teaching (Kiely et al., 2015 ). For example, appraising inclusion as an obstacle often goes along with a deficit view of students at risk for school failure, wherein educational challenges are mainly explained by students’ deficits (Ainscow, 2007 ). In contrast, the appraisals of inclusion as an opportunity for education build on an approach towards diversity that considers students’ backgrounds as an asset for learning rather than an obstacle (Ainscow, 2005 ; UNESCO, 2017a ). Previous reviews suggest that teachers appraise the inclusion of students with SEN in regular schools in a slightly negative way. Thus, as far as we know today, teachers’ cognitive appraisals have been slightly more deficit-focused than asset-based (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002 ; De Boer et al., 2011 ; Scruggs & Mastropieri, 1996 ).

Emotional Appraisals of Inclusive Education

Compared to cognitive appraisals, emotional appraisals take inclusion to a personal level (Savolainen et al., 2012 ). Teachers’ emotional appraisals are most likely to occur when their cognitive evaluation of reform indicates that the reform is personally relevant and will impact their well-being (Gregoire, 2003 ). Whereas some teachers feel threatened by inclusive education because they fear the additional workload (Pearman et al., 1997 ), anticipate stress (Jenson, 2018 ), or experience feelings of threat related to a lack of resources (Sharma & Desai, 2002 ), others feel less concerned regarding inclusion (Forlin et al., 2010 ). Evidence on teachers’ emotional appraisals varies; typically, teachers range from being only marginally concerned to very concerned about using inclusive practices (e.g., Forlin & Chambers, 2011 ).

The response teachers have depends on the individual’s appraisal of the controllability and their ability to cope with that situation (Pekrun, 2006 ). When teachers feel like situations are out of control and/or they cannot cope with the challenge, their appraisals have negative consequences for their emotional state, resulting in burn-out, inability to mobilize cognitive resources, or difficulty choosing instructional strategies effectively (Sutton & Wheatley, 2003 ; Pekrun et al., 2002; Talmor et al., 2005 ; Kunter et al., 2013 ). In turn, this state can affect their students adversely (Frenzel et al., 2021; Aldrup et al., 2018). Given the evidence on the detrimental effects of teachers’ negative emotional appraisals on various teacher, student, and instruction outcomes, one important open question is if and how emotional appraisals can be modified (Sutton & Wheatley, 2003 ), which turns attention toward understanding self-efficacy beliefs.

Self-Efficacy Beliefs about Implementing Inclusive Education

Self-efficacy beliefs regarding inclusive education refer to teachers’ resources for coping as well as their expectations of being able to support students in specific situations. Teachers are more likely to act if they believe they can successfully accomplish a reform effort (Bandura, 1997 ), such as inclusion. These self-beliefs serve as a cognitive lens through which teachers evaluate whether or not to engage in efforts to carry out reform practices (Liou et al., 2019 ).

Teachers with low self-efficacy toward implementing inclusive practices may feel incapable of including students with SEN in their classrooms, and, consequently, make little effort to adapt their teaching to meet the needs of SEN students (Sharma et al., 2012 ). Many teachers do not feel well prepared for the tasks that can arise in inclusive settings, such as responding to particular difficulties or making adaptations (Florian & Black-Hawkins, 2011 ), and they experience concern about a lack of personal and material resources to implement inclusion effectively (Sharma et al., 2009 ). In contrast, higher self-efficacy beliefs about inclusive practices are associated with stronger intentions to teach inclusively (Miesera et al., 2019 ; Opoku et al., 2020 ), a stronger willingness to implement specific inclusive practices in their classrooms (Avramidis et al., 2019 ), and higher self-reported implementation of inclusive teaching practices (Schwab & Alnahdi, 2020 ).

Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs have been found to be the most influential of the belief constructs for predicting whether or not teachers take action to carry out reform (Liou et al., 2019 ). For example, teachers’ self-efficacy to implement inclusive practices contributes to teachers’ prospective cognitive appraisals and, even more so, toward their emotional appraisals of inclusive education, based on cross-lagged analyses (Savolainen et al., 2020 ; Sharma & Sokal, 2015 ). Beyond this, higher self-efficacy protects teachers from burnout (Evers et al., 2002 ) and is one of the main psychological resources that can reduce emotional exhaustion in teachers (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2017 ).

In sum, teachers’ cognitive appraisals, emotional appraisals, and self-efficacy beliefs contribute to the extent to which teachers are likely to implement inclusive education reform in their classrooms. To date, we know that teachers vary in all aspects of their belief system towards inclusive education. However, we do not fully understand what contributes to or produces changes in these belief components. Improving our understanding will help support teachers to perceive the new standards of inclusive education as a new opportunity rather than a threat to existing instructional practice, which in turn will improve the implementation of inclusive practices (Liou et al., 2019 ).

Do Teachers’ Experiences Create Variation in Teachers’ Belief Systems about Inclusive Education?

Teachers’ experiences inside and outside of classrooms vary, and they relate to their belief systems (Didion et al., 2020 ; Klassen & Chiu, 2011 ). The associations are bi-directional: not only can teachers’ beliefs shape teachers’ experiences (for example, beliefs contribute to whether a person decides to study to become a special or regular education teacher), but their experiences can contribute to their beliefs (Fives & Buehl, 2012 ). One prevalent theme in studies of teachers’ beliefs is the category of teacher type, thus differentiating between (1) teachers with general teaching experience in regular classrooms (i.e., teaching experience with typically developing students) and (2) teachers with specific training and experience as special-needs teachers (i.e., experiences in special or inclusive classrooms).

General Teaching Experience in Regular Classrooms

Teachers’ appraisals of inclusive education may be affected by their preservice education to become a regular education teacher and years of teaching experience in a typical classroom (i.e., how long they have worked as a regular education teacher). With more years of work experience, many actions become automated throughout a teacher’s career, which enables teachers to focus on other aspects of their work (Berliner, 1994). In the beginning, novice teachers report more feelings of work overload (Paquette & Rieg, 2016 ) and tend to use more avoidant strategies (e.g., withdrawing from sources of stress) than experienced teachers (Sharplin et al., 2011 ). On the other hand, novice teachers perceive less work-related stress (Klassen & Chiu, 2011 ) and tend to be more idealistic regarding their perception of teaching than in-service teachers who regard the teaching process more realistically (Anspal et al., 2012). This can lead to over-confidence in preservice teachers, but also to more negative feelings when classroom realities do not match their expectations (Toompalu et al., 2017 ). To date, it remains an open question whether or not teachers’ years of experience in a regular classroom translate into rather positive or negative appraisals of inclusive education, as the findings have been inconclusive (see Avramidis & Norwich, 2002 ; De Boer et al., 2011 ).

Specific Training and Experience in Special Education

Teachers’ preparedness for inclusive education may also vary in light of preservice teachers’ preparation for teaching and their years of experience teaching students with special needs. Special education teachers show more positive beliefs about inclusive education than regular education teachers (Lee et al., 2015 ). While regular teachers usually have little or no training in how to teach classes with SEN students effectively, special education teachers have knowledge about individual differences and have learned teaching strategies that allow them to adapt to students with SEN. Moreover, they developed their belief system based on classroom experience with teaching students with SEN. As a consequence, special education teachers hold more positive beliefs toward inclusion, which are partly mediated by higher self-efficacy beliefs about teaching in inclusive settings (Desombre et al., 2019). Not only in-service, but also preservice special education teachers tend to have higher self-efficacy beliefs for teaching students with SEN than preservice teachers in regular teacher preparation (Leyser et al., 2011 ). Of course, it is also possible that persons who are positive about inclusion are more inclined to choose a career in SEN.

Influence of Targeted Interventions

Interventions for pre-service and in-service teachers are designed to create change in people’s beliefs and actions. Among pre-service teachers, interventions typically take the form of courses. Among in-service teachers, these interventions may be programs or courses that are embedded into professional development opportunities. For both pre-service and in-service teachers, the interventions may involve practical experiences in inclusive classrooms and/or practical experiences with students with SEN. Such experiences vary in length from just a couple of days or weeks of training to long-term intervention. To date, findings have been inconclusive (e.g., for initial teacher preparation: (Ajuwon et al., 2015 ; Rakap et al., 2017 ); for in-service teachers’ professional development: (Aiello & Sharma, 2018 ; Sucuoğlu et al., 2015 )). Moreover, it is still poorly understood which parts of teachers’ belief systems are affected, and how changes in beliefs are achieved.

To be concrete, envision situations where preservice and in-service teachers are participating in interventions (e.g., coursework, programs) designed to teach them about inclusive education. In these training situations, a teacher may react in one of three ways. Some teachers will have cognitive appraisals of inclusive education that fit with their prior knowledge and experience; their emotional appraisals may result in feelings of pleasantness or curiosity, and they will not perceive the need to reflect on and change their practices. In contrast, other teachers will have cognitive appraisals of inclusive education that reveal incongruity between their current beliefs and the new instructional content. Among these teachers experiencing incongruity, some will have emotional appraisals of concern, worry, and threat about the implementation of inclusive education, whereas others will have emotional appraisals that signal an opportunity to learn new information and grow. What differentiates between these two latter groups? Is it teachers’ point in their career, training as special educator versus regular teachers, or some aspect of the training itself?

Existing studies of inclusive education interventions and teachers’ beliefs provide the raw material for meta-analysis to answer these key questions. As mentioned above, some studies focus on preservice teachers, whereas others study in-service teachers. Some studies examine special education teachers and/or regular education teachers to understand how interventions contribute to belief change. Studies of interventions related to inclusive education also examine the role of field experience in an inclusive classroom, practical experience with people with SEN, and length of interventions—thus setting the stage to consider these features as potential moderators of change in beliefs.

Field Experience in an Inclusive Classroom

Teachers’ field experience in an inclusive classroom creates mastery or vicarious experiences that may shape how teachers think and feel about inclusive education. Providing them with real-world experiences upon which they can base their beliefs, such as field placements and observations, is assumed to foster a more realistic sense of self-efficacy and more realistic beliefs about teaching and learning (Haverback & Parault, 2009). Some studies indicate that preservice and in-service teachers benefit from having the opportunity to gain experience with inclusive education through field experience (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002 ). Most of these studies embedded field experience in course work (McHatton & Parker, 2013 ). Mastery experience has been found to be vital in predicting teachers’ self-efficacy (Wilson et al., 2020 ).

Practical Experience with People with SEN

Teachers’ practical experiences with people with SEN could have shaped their belief system. In line with Allport’s intergroup contact theory, which posits that personal contact is an effective way to reduce prejudice (Allport, 1954), many researchers have argued that teachers develop more positive beliefs about inclusive education when they have regular contact with people in marginalized groups (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002 ; Parasuram, 2006; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006 ). Work measuring practical experience with people with SEN typically asks teachers questions about how much time people have spent with individuals with different disabilities as a way of assessing the amount of contact.

Length of Intervention

Training experiences and interventions range in length, with some being short workshops of several days (e.g., 5 days in the study by Carew et al., 2019 ) and others being long-term interventions (e.g., 2 years in the study by Sharma et al., 2008 ). Existing research on the length of interventions suggests that the effectiveness of interventions increases with their length (Bezrukova et al., 2016 ). On the other hand, other meta-analyses indicate that shorter teacher interventions lead to even higher effects (e.g., Egert et al., 2018 ), or that length did not affect the effectiveness of teacher interventions at all (e.g., Gesel et al., 2021 ). Synthesizing information about how the length of interventions relates to teachers’ beliefs can inform the development of effective interventions for future use.

Existing studies vary in who receives training (preservice or in-service teachers, special education or regular education teachers) and what is considered a critical component of the delivery (field experience in inclusive classrooms, practical experience with people with SEN, short- or long-duration trainings). To date, we still have a limited understanding of the characteristics that make such interventions most effective (Lautenbach & Heyder, 2019 ). Using longitudinal designs, one can investigate the effects of interventions in teacher preparation programs and professional development on the development of teachers’ belief systems. Such studies provide the ideal raw material for meta-analysis.

The Present Study

The existing work leads us to take a three-pronged approach to examine beliefs by focusing on cognitive and emotional appraisals of inclusion as well as teachers’ own self-efficacy in teaching inclusive classrooms. The focus on teachers’ cognitive appraisals of inclusive education is important because these evaluations affect the teachers’ perception of their students (Woolfolk Hoy et al., 2006 ), influence teachers’ classroom practice (Kiely et al., 2015 ), and teachers’ well-being (Buehl & Beck, 2015 ). Examining teachers’ emotional appraisals of inclusion is important because it affects teachers’ coping processes (Gregoire, 2003 ; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984 ). Finally, examining self-efficacy beliefs about teachers’ capabilities and the outcomes of their efforts is important because it can affect their classroom behavior (Klassen & Tze, 2014 ). As described above, these belief systems are interconnected and malleable.

With this meta-analysis, we aim to test how teachers’ cognitive and emotional appraisals and self-efficacy beliefs about inclusive education vary as a function of their experiences. Furthermore, we aim to clarify which elements of teacher training have an impact on teachers’ beliefs about inclusive education.

RQ 1 How do teachers think and feel about inclusive education and how does point in their career (pre-service versus in-service) contribute to their belief systems?

In the first step, we examined teachers’ belief systems about inclusive education using the full sample of 102 studies from 40 different countries. To this end, we quantified teachers’ cognitive appraisals, emotional appraisals, and self-efficacy beliefs about teaching inclusive classes and identified whether the point in teachers’ careers (preservice vs. in-service teachers) can explain variation in these beliefs.

RQ 1.1 How do teachers cognitively appraise inclusive education, and how does this vary depending on the point in teachers’ careers (pre-service versus in-service)?

Many studies ( m = 102) have investigated teachers’ beliefs (i.e., cognitive appraisals) about inclusive education, but the results are inconclusive. Literature reviews (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002 ; De Boer et al., 2011 ) indicate that teachers vary in their views about inclusive education, with some research showing that teachers hold positive beliefs, whereas others show that teachers hold negative beliefs. Some studies show that teachers have favorable views on average (e.g., Avramidis et al., 2000 ; Wilson et al., 2016 ), whereas in other studies, teachers held negative (Rapak & Kaczmarek, 2010; Thaver & Lim, 2014 ) or neutral views about inclusive education, meaning that they neither agree nor disagree with statements such as “most children with exceptional needs are well behaved in integrated education classrooms” (Galovic et al., 2014 ; Memisevic & Hodzic, 2011 ). Based on existing work, we hypothesized that cognitive appraisals would be near the mid-range of the scale (suggesting room for growth). Further, we expected cognitive appraisals about inclusive education would be more favorable among in-service teachers compared to preservice teachers because in-service teachers base their beliefs on a broader range of work experiences than preservice teachers (Berliner, 1994; Toompalu et al., 2017 ).

RQ 1.2 How do teachers emotionally appraise inclusive education, and how are these emotional appraisals moderated by the point in the teachers’ career (pre-service versus in-service)?

Only a few studies ( m = 23) have investigated teachers’ emotional appraisals of inclusive education. While some studies indicate that teachers feel moderately concerned (Forlin & Chambers, 2011 ; Sharma & Sokal, 2015 ), others report that teachers have many concerns about the consequences of including children with SEN in their classrooms (Savoleinen et al., 2011). Therefore, we hypothesized that teachers would be, on average, moderate and near the midpoint of the scale in their emotional appraisals of inclusive education, indicating hesitant feelings toward inclusive education. Further, we expected that emotional appraisals would be more positive among in-service teachers because they have more experience managing work overload (Paquette & Rieg, 2016 ) and possess more effective coping strategies than preservice teachers (Sharplin et al., 2011 ).

RQ 1.3 How self-efficacious are teachers toward implementing inclusive education, and how is self-efficacy moderated by teachers’ point in their careers (preservice versus in-service)?

Only a few studies ( m = 24) examined self-efficacy for inclusive education. In general, we hypothesized that teachers would rate near the midpoint of the scale for self-efficacy beliefs, suggesting room for growth before teachers adopt inclusive practices readily. Based on the evidence that shows higher self-efficacy beliefs for preservice than for in-service teachers (Ismailos et al., 2019 ; Tümkaya & Miller, 2020 ), we hypothesized higher self-efficacy among preservice than in-service teachers because preservice teachers tend to overestimate their abilities given their limited experience (Anspal et al., 2012; Ismailos et al., 2019 ).

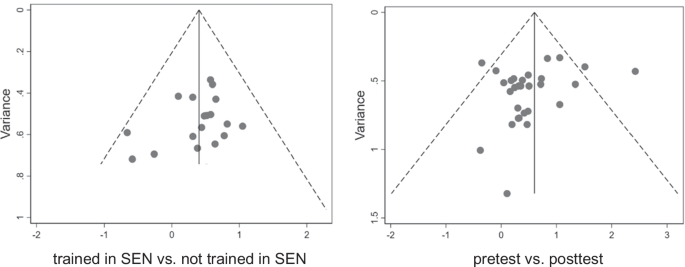

RQ 2 Do special and regular education teachers’ belief systems about inclusive education differ?

In the second step, we investigated the differences in belief systems about inclusive education among special and regular education teachers given that these two types of teachers have different training and subsequent experience in the classroom. Quite a few of the retrieved studies ( m = 18) provided data that directly compared the beliefs of special and regular education teachers, thus creating an opportunity to conduct a separate meta-analysis with these 18 studies to compare differences in beliefs by teacher type. Based on the assumption that initial teacher preparation has an impact on teachers’ formation of their belief systems, we expected special education teachers to hold more affirmative cognitive appraisals (Lee et al., 2015 ), more confident emotional appraisals (Schields, 2020), and higher self-efficacy beliefs about teaching inclusive classrooms (Desombre et al., 2019; Leyser et al., 2011 ) than regular education teachers.

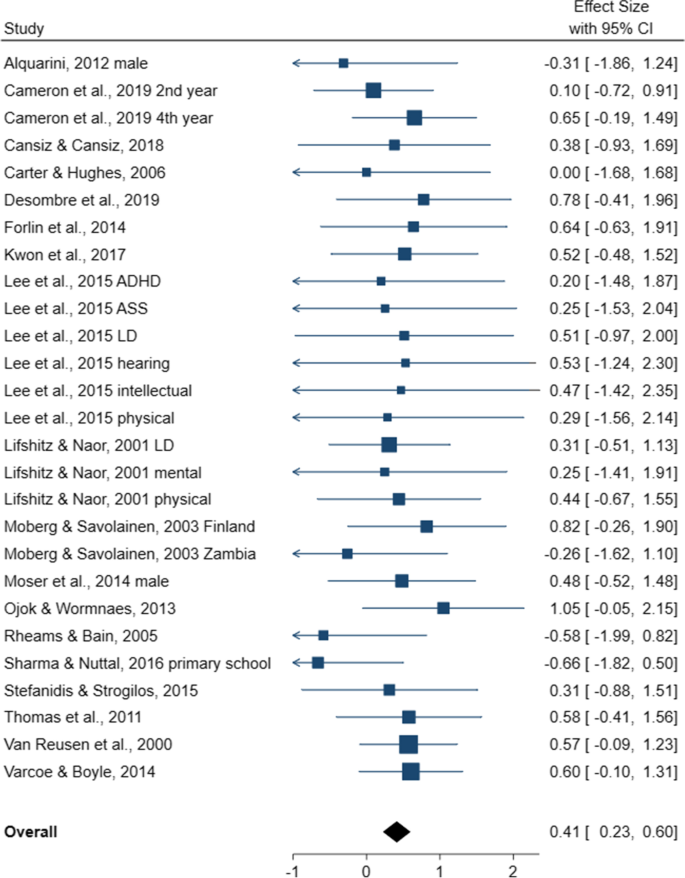

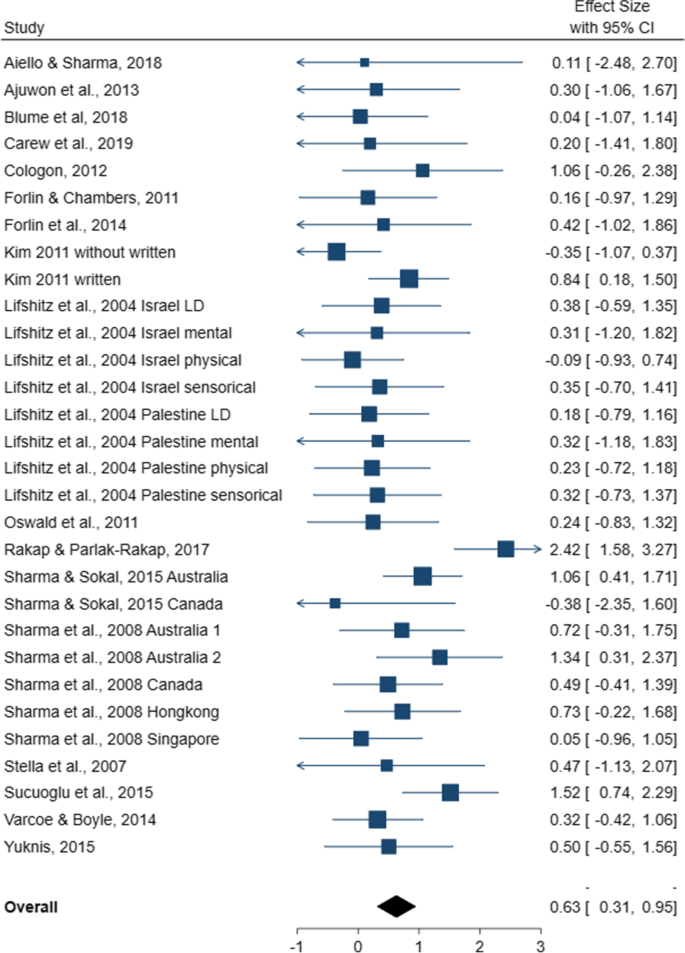

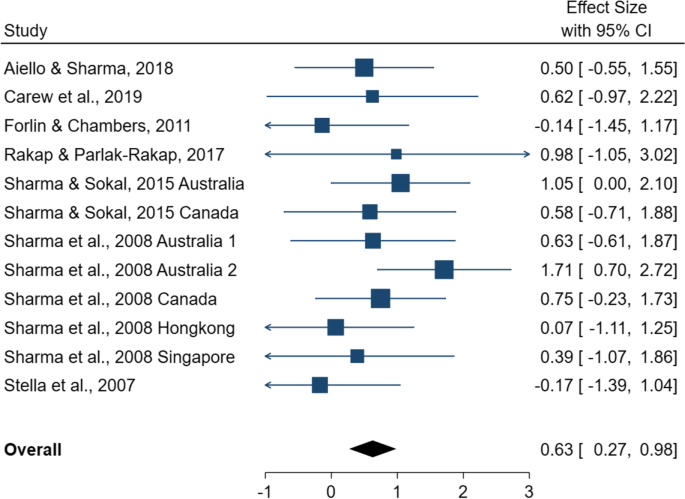

RQ 3 How malleable are beliefs about inclusive education following intervention (i.e., training, teacher preparation, professional development)?