Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 06 December 2017

Healthy food choices are happy food choices: Evidence from a real life sample using smartphone based assessments

- Deborah R. Wahl 1 na1 ,

- Karoline Villinger 1 na1 ,

- Laura M. König ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3655-8842 1 ,

- Katrin Ziesemer 1 ,

- Harald T. Schupp 1 &

- Britta Renner 1

Scientific Reports volume 7 , Article number: 17069 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

134k Accesses

55 Citations

260 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health sciences

- Human behaviour

Research suggests that “healthy” food choices such as eating fruits and vegetables have not only physical but also mental health benefits and might be a long-term investment in future well-being. This view contrasts with the belief that high-caloric foods taste better, make us happy, and alleviate a negative mood. To provide a more comprehensive assessment of food choice and well-being, we investigated in-the-moment eating happiness by assessing complete, real life dietary behaviour across eight days using smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment. Three main findings emerged: First, of 14 different main food categories, vegetables consumption contributed the largest share to eating happiness measured across eight days. Second, sweets on average provided comparable induced eating happiness to “healthy” food choices such as fruits or vegetables. Third, dinner elicited comparable eating happiness to snacking. These findings are discussed within the “food as health” and “food as well-being” perspectives on eating behaviour.

Similar content being viewed by others

Microdosing with psilocybin mushrooms: a double-blind placebo-controlled study

Adults who microdose psychedelics report health related motivations and lower levels of anxiety and depression compared to non-microdosers

Mendelian randomization evidence for the causal effect of mental well-being on healthy aging

Introduction.

When it comes to eating, researchers, the media, and policy makers mainly focus on negative aspects of eating behaviour, like restricting certain foods, counting calories, and dieting. Likewise, health intervention efforts, including primary prevention campaigns, typically encourage consumers to trade off the expected enjoyment of hedonic and comfort foods against health benefits 1 . However, research has shown that diets and restrained eating are often counterproductive and may even enhance the risk of long-term weight gain and eating disorders 2 , 3 . A promising new perspective entails a shift from food as pure nourishment towards a more positive and well-being centred perspective of human eating behaviour 1 , 4 , 5 . In this context, Block et al . 4 have advocated a paradigm shift from “food as health” to “food as well-being” (p. 848).

Supporting this perspective of “food as well-being”, recent research suggests that “healthy” food choices, such as eating more fruits and vegetables, have not only physical but also mental health benefits 6 , 7 and might be a long-term investment in future well-being 8 . For example, in a nationally representative panel survey of over 12,000 adults from Australia, Mujcic and Oswald 8 showed that fruit and vegetable consumption predicted increases in happiness, life satisfaction, and well-being over two years. Similarly, using lagged analyses, White and colleagues 9 showed that fruit and vegetable consumption predicted improvements in positive affect on the subsequent day but not vice versa. Also, cross-sectional evidence reported by Blanchflower et al . 10 shows that eating fruits and vegetables is positively associated with well-being after adjusting for demographic variables including age, sex, or race 11 . Of note, previous research includes a wide range of time lags between actual eating occasion and well-being assessment, ranging from 24 hours 9 , 12 to 14 days 6 , to 24 months 8 . Thus, the findings support the notion that fruit and vegetable consumption has beneficial effects on different indicators of well-being, such as happiness or general life satisfaction, across a broad range of time spans.

The contention that healthy food choices such as a higher fruit and vegetable consumption is associated with greater happiness and well-being clearly contrasts with the common belief that in particular high-fat, high-sugar, or high-caloric foods taste better and make us happy while we are eating them. When it comes to eating, people usually have a spontaneous “unhealthy = tasty” association 13 and assume that chocolate is a better mood booster than an apple. According to this in-the-moment well-being perspective, consumers have to trade off the expected enjoyment of eating against the health costs of eating unhealthy foods 1 , 4 .

A wealth of research shows that the experience of negative emotions and stress leads to increased consumption in a substantial number of individuals (“emotional eating”) of unhealthy food (“comfort food”) 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 . However, this research stream focuses on emotional eating to “smooth” unpleasant experiences in response to stress or negative mood states, and the mood-boosting effect of eating is typically not assessed 18 . One of the few studies testing the effectiveness of comfort food in improving mood showed that the consumption of “unhealthy” comfort food had a mood boosting effect after a negative mood induction but not to a greater extent than non-comfort or neutral food 19 . Hence, even though people may believe that snacking on “unhealthy” foods like ice cream or chocolate provides greater pleasure and psychological benefits, the consumption of “unhealthy” foods might not actually be more psychologically beneficial than other foods.

However, both streams of research have either focused on a single food category (fruit and vegetable consumption), a single type of meal (snacking), or a single eating occasion (after negative/neutral mood induction). Accordingly, it is unknown whether the boosting effect of eating is specific to certain types of food choices and categories or whether eating has a more general boosting effect that is observable after the consumption of both “healthy” and “unhealthy” foods and across eating occasions. Accordingly, in the present study, we investigated the psychological benefits of eating that varied by food categories and meal types by assessing complete dietary behaviour across eight days in real life.

Furthermore, previous research on the impact of eating on well-being tended to rely on retrospective assessments such as food frequency questionnaires 8 , 10 and written food diaries 9 . Such retrospective self-report methods rely on the challenging task of accurately estimating average intake or remembering individual eating episodes and may lead to under-reporting food intake, particularly unhealthy food choices such as snacks 7 , 20 . To avoid memory and bias problems in the present study we used ecological momentary assessment (EMA) 21 to obtain ecologically valid and comprehensive real life data on eating behaviour and happiness as experienced in-the-moment.

In the present study, we examined the eating happiness and satisfaction experienced in-the-moment, in real time and in real life, using a smartphone based EMA approach. Specifically, healthy participants were asked to record each eating occasion, including main meals and snacks, for eight consecutive days and rate how tasty their meal/snack was, how much they enjoyed it, and how pleased they were with their meal/snack immediately after each eating episode. This intense recording of every eating episode allows assessing eating behaviour on the level of different meal types and food categories to compare experienced eating happiness across meals and categories. Following the two different research streams, we expected on a food category level that not only “unhealthy” foods like sweets would be associated with high experienced eating happiness but also “healthy” food choices such as fruits and vegetables. On a meal type level, we hypothesised that the happiness of meals differs as a function of meal type. According to previous contention, snacking in particular should be accompanied by greater happiness.

Eating episodes

Overall, during the study period, a total of 1,044 completed eating episodes were reported (see also Table 1 ). On average, participants rated their eating happiness with M = 77.59 which suggests that overall eating occasions were generally positive. However, experienced eating happiness also varied considerably between eating occasions as indicated by a range from 7.00 to 100.00 and a standard deviation of SD = 16.41.

Food categories and experienced eating happiness

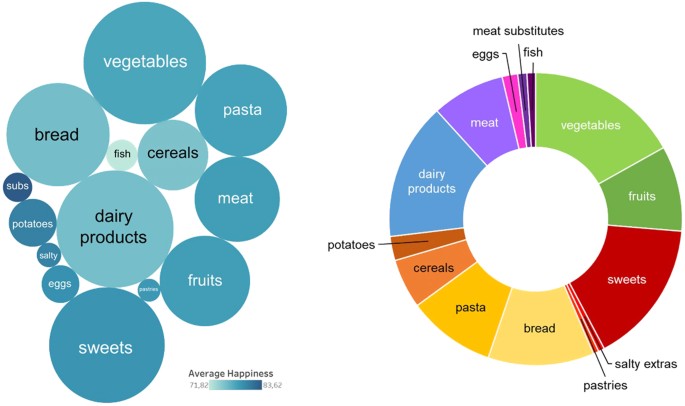

All eating episodes were categorised according to their food category based on the German Nutrient Database (German: Bundeslebensmittelschlüssel), which covers the average nutritional values of approximately 10,000 foods available on the German market and is a validated standard instrument for the assessment of nutritional surveys in Germany. As shown in Table 1 , eating happiness differed significantly across all 14 food categories, F (13, 2131) = 1.78, p = 0.04. On average, experienced eating happiness varied from 71.82 ( SD = 18.65) for fish to 83.62 ( SD = 11.61) for meat substitutes. Post hoc analysis, however, did not yield significant differences in experienced eating happiness between food categories, p ≥ 0.22. Hence, on average, “unhealthy” food choices such as sweets ( M = 78.93, SD = 15.27) did not differ in experienced happiness from “healthy” food choices such as fruits ( M = 78.29, SD = 16.13) or vegetables ( M = 77.57, SD = 17.17). In addition, an intraclass correlation (ICC) of ρ = 0.22 for happiness indicated that less than a quarter of the observed variation in experienced eating happiness was due to differences between food categories, while 78% of the variation was due to differences within food categories.

However, as Figure 1 (left side) depicts, consumption frequency differed greatly across food categories. Frequently consumed food categories encompassed vegetables which were consumed at 38% of all eating occasions ( n = 400), followed by dairy products with 35% ( n = 366), and sweets with 34% ( n = 356). Conversely, rarely consumed food categories included meat substitutes, which were consumed in 2.2% of all eating occasions ( n = 23), salty extras (1.5%, n = 16), and pastries (1.3%, n = 14).

Left side: Average experienced eating happiness (colour intensity: darker colours indicate greater happiness) and consumption frequency (size of the cycle) for the 14 food categories. Right side: Absolute share of the 14 food categories in total experienced eating happiness.

Amount of experienced eating happiness by food category

To account for the frequency of consumption, we calculated and scaled the absolute experienced eating happiness according to the total sum score. As shown in Figure 1 (right side), vegetables contributed the biggest share to the total happiness followed by sweets, dairy products, and bread. Clustering food categories shows that fruits and vegetables accounted for nearly one quarter of total eating happiness score and thus, contributed to a large part of eating related happiness. Grain products such as bread, pasta, and cereals, which are main sources of carbohydrates including starch and fibre, were the second main source for eating happiness. However, “unhealthy” snacks including sweets, salty extras, and pastries represented the third biggest source of eating related happiness.

Experienced eating happiness by meal type

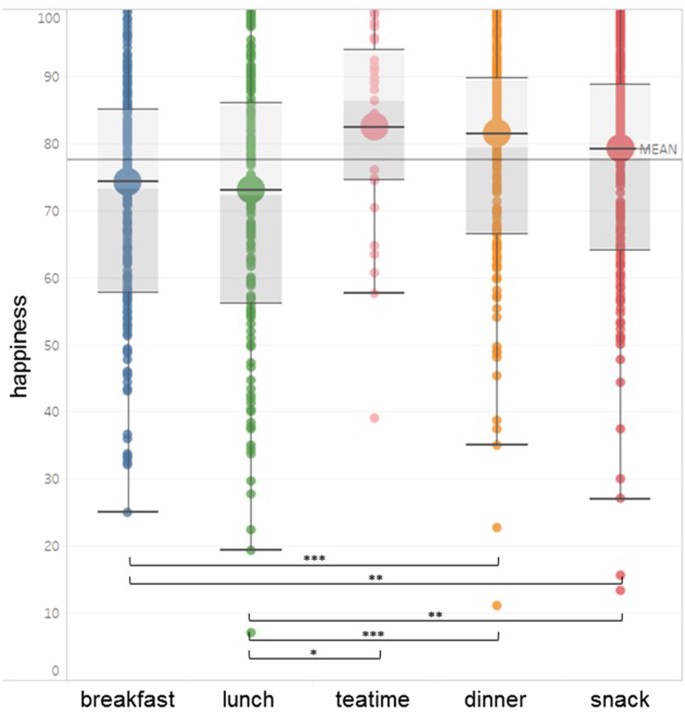

To further elucidate the contribution of snacks to eating happiness, analysis on the meal type level was conducted. Experienced in-the-moment eating happiness significantly varied by meal type consumed, F (4, 1039) = 11.75, p < 0.001. Frequencies of meal type consumption ranged from snacks being the most frequently logged meal type ( n = 332; see also Table 1 ) to afternoon tea being the least logged meal type ( n = 27). Figure 2 illustrates the wide dispersion within as well as between different meal types. Afternoon tea ( M = 82.41, SD = 15.26), dinner ( M = 81.47, SD = 14.73), and snacks ( M = 79.45, SD = 14.94) showed eating happiness values above the grand mean, whereas breakfast ( M = 74.28, SD = 16.35) and lunch ( M = 73.09, SD = 18.99) were below the eating happiness mean. Comparisons between meal types showed that eating happiness for snacks was significantly higher than for lunch t (533) = −4.44, p = 0.001, d = −0.38 and breakfast, t (567) = −3.78, p = 0.001, d = −0.33. However, this was also true for dinner, which induced greater eating happiness than lunch t (446) = −5.48, p < 0.001, d = −0.50 and breakfast, t (480) = −4.90, p < 0.001, d = −0.46. Finally, eating happiness for afternoon tea was greater than for lunch t (228) = −2.83, p = 0.047, d = −0.50. All other comparisons did not reach significance, t ≤ 2.49, p ≥ 0.093.

Experienced eating happiness per meal type. Small dots represent single eating events, big circles indicate average eating happiness, and the horizontal line indicates the grand mean. Boxes indicate the middle 50% (interquartile range) and median (darker/lighter shade). The whiskers above and below represent 1.5 of the interquartile range.

Control Analyses

In order to test for a potential confounding effect between experienced eating happiness, food categories, and meal type, additional control analyses within meal types were conducted. Comparing experienced eating happiness for dinner and lunch suggested that dinner did not trigger a happiness spill-over effect specific to vegetables since the foods consumed at dinner were generally associated with greater happiness than those consumed at other eating occasions (Supplementary Table S1 ). Moreover, the relative frequency of vegetables consumed at dinner (73%, n = 180 out of 245) and at lunch were comparable (69%, n = 140 out of 203), indicating that the observed happiness-vegetables link does not seem to be mainly a meal type confounding effect.

Since the present study focuses on “food effects” (Level 1) rather than “person effects” (Level 2), we analysed the data at the food item level. However, participants who were generally overall happier with their eating could have inflated the observed happiness scores for certain food categories. In order to account for person-level effects, happiness scores were person-mean centred and thereby adjusted for mean level differences in happiness. The person-mean centred happiness scores ( M cwc ) represent the difference between the individual’s average happiness score (across all single in-the-moment happiness scores per food category) and the single happiness scores of the individual within the respective food category. The centred scores indicate whether the single in-the-moment happiness score was above (indicated by positive values) or below (indicated by negative values) the individual person-mean. As Table 1 depicts, the control analyses with centred values yielded highly similar results. Vegetables were again associated on average with more happiness than other food categories (although people might differ in their general eating happiness). An additional conducted ANOVA with person-centred happiness values as dependent variables and food categories as independent variables provided also a highly similar pattern of results. Replicating the previously reported analysis, eating happiness differed significantly across all 14 food categories, F (13, 2129) = 1.94, p = 0.023, and post hoc analysis did not yield significant differences in experienced eating happiness between food categories, p ≥ 0.14. Moreover, fruits and vegetables were associated with high happiness values, and “unhealthy” food choices such as sweets did not differ in experienced happiness from “healthy” food choices such as fruits or vegetables. The only difference between the previous and control analysis was that vegetables ( M cwc = 1.16, SD = 15.14) gained slightly in importance for eating-related happiness, whereas fruits ( M cwc = −0.65, SD = 13.21), salty extras ( M cwc = −0.07, SD = 8.01), and pastries ( M cwc = −2.39, SD = 18.26) became slightly less important.

This study is the first, to our knowledge, that investigated in-the-moment experienced eating happiness in real time and real life using EMA based self-report and imagery covering the complete diversity of food intake. The present results add to and extend previous findings by suggesting that fruit and vegetable consumption has immediate beneficial psychological effects. Overall, of 14 different main food categories, vegetables consumption contributed the largest share to eating happiness measured across eight days. Thus, in addition to the investment in future well-being indicated by previous research 8 , “healthy” food choices seem to be an investment in the in-the moment well-being.

Importantly, although many cultures convey the belief that eating certain foods has a greater hedonic and mood boosting effect, the present results suggest that this might not reflect actual in-the-moment experiences accurately. Even though people often have a spontaneous “unhealthy = tasty” intuition 13 , thus indicating that a stronger happiness boosting effect of “unhealthy” food is to be expected, the induced eating happiness of sweets did not differ on average from “healthy” food choices such as fruits or vegetables. This was also true for other stereotypically “unhealthy” foods such as pastries and salty extras, which did not show the expected greater boosting effect on happiness. Moreover, analyses on the meal type level support this notion, since snacks, despite their overall positive effect, were not the most psychologically beneficial meal type, i.e., dinner had a comparable “happiness” signature to snacking. Taken together, “healthy choices” seem to be also “happy choices” and at least comparable to or even higher in their hedonic value as compared to stereotypical “unhealthy” food choices.

In general, eating happiness was high, which concurs with previous research from field studies with generally healthy participants. De Castro, Bellisle, and Dalix 22 examined weekly food diaries from 54 French subjects and found that most of the meals were rated as appealing. Also, the observed differences in average eating happiness for the 14 different food categories, albeit statistically significant, were comparable small. One could argue that this simply indicates that participants avoided selecting bad food 22 . Alternatively, this might suggest that the type of food or food categories are less decisive for experienced eating happiness than often assumed. This relates to recent findings in the field of comfort and emotional eating. Many people believe that specific types of food have greater comforting value. Also in research, the foods eaten as response to negative emotional strain, are typically characterised as being high-caloric because such foods are assumed to provide immediate psycho-physical benefits 18 . However, comparing different food types did not provide evidence for the notion that they differed in their provided comfort; rather, eating in general led to significant improvements in mood 19 . This is mirrored in the present findings. Comparing the eating happiness of “healthy” food choices such as fruits and vegetables to that of “unhealthy” food choices such as sweets shows remarkably similar patterns as, on average, they were associated with high eating happiness and their range of experiences ranged from very negative to very positive.

This raises the question of why the idea that we can eat indulgent food to compensate for life’s mishaps is so prevailing. In an innovative experimental study, Adriaanse, Prinsen, de Witt Huberts, de Ridder, and Evers 23 led participants believe that they overate. Those who characterised themselves as emotional eaters falsely attributed their over-consumption to negative emotions, demonstrating a “confabulation”-effect. This indicates that people might have restricted self-knowledge and that recalled eating episodes suffer from systematic recall biases 24 . Moreover, Boelsma, Brink, Stafleu, and Hendriks 25 examined postprandial subjective wellness and objective parameters (e.g., ghrelin, insulin, glucose) after standardised breakfast intakes and did not find direct correlations. This suggests that the impact of different food categories on wellness might not be directly related to biological effects but rather due to conditioning as food is often paired with other positive experienced situations (e.g., social interactions) or to placebo effects 18 . Moreover, experimental and field studies indicate that not only negative, but also positive, emotions trigger eating 15 , 26 . One may speculate that selective attention might contribute to the “myth” of comfort food 19 in that people attend to the consumption effect of “comfort” food in negative situation but neglect the effect in positive ones.

The present data also show that eating behaviour in the real world is a complex behaviour with many different aspects. People make more than 200 food decisions a day 27 which poses a great challenge for the measurement of eating behaviour. Studies often assess specific food categories such as fruit and vegetable consumption using Food Frequency Questionnaires, which has clear advantages in terms of cost-effectiveness. However, focusing on selective aspects of eating and food choices might provide only a selective part of the picture 15 , 17 , 22 . It is important to note that focusing solely on the “unhealthy” food choices such as sweets would have led to the conclusion that they have a high “indulgent” value. To be able to draw conclusions about which foods make people happy, the relation of different food categories needs to be considered. The more comprehensive view, considering the whole dietary behaviour across eating occasions, reveals that “healthy” food choices actually contributed the biggest share to the total experienced eating happiness. Thus, for a more comprehensive understanding of how eating behaviours are regulated, more complete and sensitive measures of the behaviour are necessary. Developments in mobile technologies hold great promise for feasible dietary assessment based on image-assisted methods 28 .

As fruits and vegetables evoked high in-the-moment happiness experiences, one could speculate that these cumulate and have spill-over effects on subsequent general well-being, including life satisfaction across time. Combing in-the-moment measures with longitudinal perspectives might be a promising avenue for future studies for understanding the pathways from eating certain food types to subjective well-being. In the literature different pathways are discussed, including physiological and biochemical aspects of specific food elements or nutrients 7 .

The present EMA based data also revealed that eating happiness varied greatly within the 14 food categories and meal types. As within food category variance represented more than two third of the total observed variance, happiness varied according to nutritional characteristics and meal type; however, a myriad of factors present in the natural environment can affect each and every meal. Thus, widening the “nourishment” perspective by including how much, when, where, how long, and with whom people eat might tell us more about experienced eating happiness. Again, mobile, in-the-moment assessment opens the possibility of assessing the behavioural signature of eating in real life. Moreover, individual factors such as eating motives, habitual eating styles, convenience, and social norms are likely to contribute to eating happiness variance 5 , 29 .

A key strength of this study is that it was the first to examine experienced eating happiness in non-clinical participants using EMA technology and imagery to assess food intake. Despite this strength, there are some limitations to this study that affect the interpretation of the results. In the present study, eating happiness was examined on a food based level. This neglects differences on the individual level and might be examined in future multilevel studies. Furthermore, as a main aim of this study was to assess real life eating behaviour, the “natural” observation level is the meal, the psychological/ecological unit of eating 30 , rather than food categories or nutrients. Therefore, we cannot exclude that specific food categories may have had a comparably higher impact on the experienced happiness of the whole meal. Sample size and therefore Type I and Type II error rates are of concern. Although the total number of observations was higher than in previous studies (see for example, Boushey et al . 28 for a review), the number of participants was small but comparable to previous studies in this field 20 , 31 , 32 , 33 . Small sample sizes can increase error rates because the number of persons is more decisive than the number of nested observations 34 . Specially, nested data can seriously increase Type I error rates, which is rather unlikely to be the case in the present study. Concerning Type II error rates, Aarts et al . 35 illustrated for lower ICCs that adding extra observations per participant also increases power, particularly in the lower observation range. Considering the ICC and the number of observations per participant, one could argue that the power in the present study is likely to be sufficient to render the observed null-differences meaningful. Finally, the predominately white and well-educated sample does limit the degree to which the results can be generalised to the wider community; these results warrant replication with a more representative sample.

Despite these limitations, we think that our study has implications for both theory and practice. The cumulative evidence of psychological benefits from healthy food choices might offer new perspectives for health promotion and public-policy programs 8 . Making people aware of the “healthy = happy” association supported by empirical evidence provides a distinct and novel perspective to the prevailing “unhealthy = tasty” folk intuition and could foster eating choices that increase both in-the-moment happiness and future well-being. Furthermore, the present research lends support to the advocated paradigm shift from “food as health” to “food as well-being” which entails a supporting and encouraging rather constraining and limiting view on eating behaviour.

The study conformed with the Declaration of Helsinki. All study protocols were approved by University of Konstanz’s Institutional Review Board and were conducted in accordance with guidelines and regulations. Upon arrival, all participants signed a written informed consent.

Participants

Thirty-eight participants (28 females: average age = 24.47, SD = 5.88, range = 18–48 years) from the University of Konstanz assessed their eating behaviour in close to real time and in their natural environment using an event-based ambulatory assessment method (EMA). No participant dropped out or had to be excluded. Thirty-three participants were students, with 52.6% studying psychology. As compensation, participants could choose between taking part in a lottery (4 × 25€) or receiving course credits (2 hours).

Participants were recruited through leaflets distributed at the university and postings on Facebook groups. Prior to participation, all participants gave written informed consent. Participants were invited to the laboratory for individual introductory sessions. During this first session, participants installed the application movisensXS (version 0.8.4203) on their own smartphones and downloaded the study survey (movisensXS Library v4065). In addition, they completed a short baseline questionnaire, including demographic variables like age, gender, education, and eating principles. Participants were instructed to log every eating occasion immediately before eating by using the smartphone to indicate the type of meal, take pictures of the food, and describe its main components using a free input field. Fluid intake was not assessed. Participants were asked to record their food intake on eight consecutive days. After finishing the study, participants were invited back to the laboratory for individual final interviews.

Immediately before eating participants were asked to indicate the type of meal with the following five options: breakfast, lunch, afternoon tea, dinner, snack. In Germany, “afternoon tea” is called “Kaffee & Kuchen” which directly translates as “coffee & cake”. It is similar to the idea of a traditional “afternoon tea” meal in UK. Specifically, in Germany, people have “Kaffee & Kuchen” in the afternoon (between 4–5 pm) and typically coffee (or tea) is served with some cake or cookies. Dinner in Germany is a main meal with mainly savoury food.

After each meal, participants were asked to rate their meal on three dimensions. They rated (1) how much they enjoyed the meal, (2) how pleased they were with their meal, and (3) how tasty their meal was. Ratings were given on a scale of one to 100. For reliability analysis, Cronbach’s Alpha was calculated to assess the internal consistency of the three items. Overall Cronbach’s alpha was calculated with α = 0.87. In addition, the average of the 38 Cronbach’s alpha scores calculated at the person level also yielded a satisfactory value with α = 0.83 ( SD = 0.24). Thirty-two of 38 participants showed a Cronbach’s alpha value above 0.70 (range = 0.42–0.97). An overall score of experienced happiness of eating was computed using the average of the three questions concerning the meals’ enjoyment, pleasure, and tastiness.

Analytical procedure

The food pictures and descriptions of their main components provided by the participants were subsequently coded by independent and trained raters. Following a standardised manual, additional components displayed in the picture were added to the description by the raters. All consumed foods were categorised into 14 different food categories (see Table 1 ) derived from the food classification system designed by the German Nutrition Society (DGE) and based on the existing food categories of the German Nutrient Database (Max Rubner Institut). Liquid intake and preparation method were not assessed. Therefore, fats and additional recipe ingredients were not included in further analyses, because they do not represent main elements of food intake. Further, salty extras were added to the categorisation.

No participant dropped out or had to be excluded due to high missing rates. Missing values were below 5% for all variables. The compliance rate at the meal level cannot be directly assessed since the numbers of meals and snacks can vary between as well as within persons (between days). As a rough compliance estimate, the numbers of meals that are expected from a “normative” perspective during the eight observation days can be used as a comparison standard (8 x breakfast, 8 × lunch, 8 × dinner = 24 meals). On average, the participants reported M = 6.3 breakfasts ( SD = 2.3), M = 5.3 lunches ( SD = 1.8), and M = 6.5 dinners ( SD = 2.0). In comparison to the “normative” expected 24 meals, these numbers indicate a good compliance (approx. 75%) with a tendency to miss six meals during the study period (approx. 25%). However, the “normative” expected 24 meals for the study period might be too high since participants might also have skipped meals (e.g. breakfast). Also, the present compliance rates are comparable to other studies. For example, Elliston et al . 36 recorded 3.3 meal/snack reports per day in an Australian adult sample and Casperson et al . 37 recorded 2.2 meal reports per day in a sample of adolescents. In the present study, on average, M = 3.4 ( SD = 1.35) meals or snacks were reported per day. These data indicate overall a satisfactory compliance rate and did not indicate selective reporting of certain food items.

To graphically visualise data, Tableau (version 10.1) was used and for further statistical analyses, IBM SPSS Statistics (version 24 for Windows).

Data availability

The dataset generated and analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Cornil, Y. & Chandon, P. Pleasure as an ally of healthy eating? Contrasting visceral and epicurean eating pleasure and their association with portion size preferences and wellbeing. Appetite 104 , 52–59 (2016).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Mann, T. et al . Medicare’s search for effective obesity treatments: Diets are not the answer. American Psychologist 62 , 220–233 (2007).

van Strien, T., Herman, C. P. & Verheijden, M. W. Dietary restraint and body mass change. A 3-year follow up study in a representative Dutch sample. Appetite 76 , 44–49 (2014).

Block, L. G. et al . From nutrients to nurturance: A conceptual introduction to food well-being. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 30 , 5–13 (2011).

Article Google Scholar

Renner, B., Sproesser, G., Strohbach, S. & Schupp, H. T. Why we eat what we eat. The eating motivation survey (TEMS). Appetite 59 , 117–128 (2012).

Conner, T. S., Brookie, K. L., Carr, A. C., Mainvil, L. A. & Vissers, M. C. Let them eat fruit! The effect of fruit and vegetable consumption on psychological well-being in young adults: A randomized controlled trial. PloS one 12 , e0171206 (2017).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rooney, C., McKinley, M. C. & Woodside, J. V. The potential role of fruit and vegetables in aspects of psychological well-being: a review of the literature and future directions. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 72 , 420–432 (2013).

Mujcic, R. & Oswald, A. J. Evolution of well-being and happiness after increases in consumption of fruit and vegetables. American Journal of Public Health 106 , 1504–1510 (2016).

White, B. A., Horwath, C. C. & Conner, T. S. Many apples a day keep the blues away – Daily experiences of negative and positive affect and food consumption in young adults. British Journal of Health Psychology 18 , 782–798 (2013).

Blanchflower, D. G., Oswald, A. J. & Stewart-Brown, S. Is psychological well-being linked to the consumption of fruit and vegetables? Social Indicators Research 114 , 785–801 (2013).

Grant, N., Wardle, J. & Steptoe, A. The relationship between life satisfaction and health behavior: A Cross-cultural analysis of young adults. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 16 , 259–268 (2009).

Conner, T. S., Brookie, K. L., Richardson, A. C. & Polak, M. A. On carrots and curiosity: Eating fruit and vegetables is associated with greater flourishing in daily life. British Journal of Health Psychology 20 , 413–427 (2015).

Raghunathan, R., Naylor, R. W. & Hoyer, W. D. The unhealthy = tasty intuition and its effects on taste inferences, enjoyment, and choice of food products. Journal of Marketing 70 , 170–184 (2006).

Evers, C., Stok, F. M. & de Ridder, D. T. Feeding your feelings: Emotion regulation strategies and emotional eating. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 36 , 792–804 (2010).

Sproesser, G., Schupp, H. T. & Renner, B. The bright side of stress-induced eating: eating more when stressed but less when pleased. Psychological Science 25 , 58–65 (2013).

Wansink, B., Cheney, M. M. & Chan, N. Exploring comfort food preferences across age and gender. Physiology & Behavior 79 , 739–747 (2003).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Taut, D., Renner, B. & Baban, A. Reappraise the situation but express your emotions: impact of emotion regulation strategies on ad libitum food intake. Frontiers in Psychology 3 , 359 (2012).

Tomiyama, J. A., Finch, L. E. & Cummings, J. R. Did that brownie do its job? Stress, eating, and the biobehavioral effects of comfort food. Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary, Searchable, and Linkable Resource (2015).

Wagner, H. S., Ahlstrom, B., Redden, J. P., Vickers, Z. & Mann, T. The myth of comfort food. Health Psychology 33 , 1552–1557 (2014).

Schüz, B., Bower, J. & Ferguson, S. G. Stimulus control and affect in dietary behaviours. An intensive longitudinal study. Appetite 87 , 310–317 (2015).

Shiffman, S. Conceptualizing analyses of ecological momentary assessment data. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 16 , S76–S87 (2014).

de Castro, J. M., Bellisle, F. & Dalix, A.-M. Palatability and intake relationships in free-living humans: measurement and characterization in the French. Physiology & Behavior 68 , 271–277 (2000).

Adriaanse, M. A., Prinsen, S., de Witt Huberts, J. C., de Ridder, D. T. & Evers, C. ‘I ate too much so I must have been sad’: Emotions as a confabulated reason for overeating. Appetite 103 , 318–323 (2016).

Robinson, E. Relationships between expected, online and remembered enjoyment for food products. Appetite 74 , 55–60 (2014).

Boelsma, E., Brink, E. J., Stafleu, A. & Hendriks, H. F. Measures of postprandial wellness after single intake of two protein–carbohydrate meals. Appetite 54 , 456–464 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Boh, B. et al . Indulgent thinking? Ecological momentary assessment of overweight and healthy-weight participants’ cognitions and emotions. Behaviour Research and Therapy 87 , 196–206 (2016).

Wansink, B. & Sobal, J. Mindless eating: The 200 daily food decisions we overlook. Environment and Behavior 39 , 106–123 (2007).

Boushey, C., Spoden, M., Zhu, F., Delp, E. & Kerr, D. New mobile methods for dietary assessment: review of image-assisted and image-based dietary assessment methods. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society , 1–12 (2016).

Stok, F. M. et al . The DONE framework: Creation, evaluation, and updating of an interdisciplinary, dynamic framework 2.0 of determinants of nutrition and eating. PLoS ONE 12 , e0171077 (2017).

Pliner, P. & Rozin, P. In Dimensions of the meal: The science, culture, business, and art of eating (ed H Meiselman) 19–46 (Aspen Publishers, 2000).

Inauen, J., Shrout, P. E., Bolger, N., Stadler, G. & Scholz, U. Mind the gap? Anintensive longitudinal study of between-person and within-person intention-behaviorrelations. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 50 , 516–522 (2016).

Zepeda, L. & Deal, D. Think before you eat: photographic food diaries asintervention tools to change dietary decision making and attitudes. InternationalJournal of Consumer Studies 32 , 692–698 (2008).

Stein, K. F. & Corte, C. M. Ecologic momentary assessment of eating‐disordered behaviors. International Journal of Eating Disorders 34 , 349–360 (2003).

Bolger, N., Stadler, G. & Laurenceau, J. P. Power analysis for intensive longitudinal studies in Handbook of research methods for studying daily life (ed . Mehl, M. R. & Conner, T. S.) 285–301 (New York: The Guilford Press, 2012).

Aarts, E., Verhage, M., Veenvliet, J. V., Dolan, C. V. & Van Der Sluis, S. A solutionto dependency: using multilevel analysis to accommodate nested data. Natureneuroscience 17 , 491–496 (2014).

Elliston, K. G., Ferguson, S. G., Schüz, N. & Schüz, B. Situational cues andmomentary food environment predict everyday eating behavior in adults withoverweight and obesity. Health Psychology 36 , 337–345 (2017).

Casperson, S. L. et al . A mobile phone food record app to digitally capture dietary intake for adolescents in afree-living environment: usability study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 3 , e30 (2015).

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research within the project SmartAct (Grant 01EL1420A, granted to B.R. & H.S.). The funding source had no involvement in the study’s design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; or the decision to submit this article for publication. We thank Gudrun Sproesser, Helge Giese, and Angela Whale for their valuable support.

Author information

Deborah R. Wahl and Karoline Villinger contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

Department of Psychology, University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany

Deborah R. Wahl, Karoline Villinger, Laura M. König, Katrin Ziesemer, Harald T. Schupp & Britta Renner

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

B.R. & H.S. developed the study concept. All authors participated in the generation of the study design. D.W., K.V., L.K. & K.Z. conducted the study, including participant recruitment and data collection, under the supervision of B.R. & H.S.; D.W. & K.V. conducted data analyses. D.W. & K.V. prepared the first manuscript draft, and B.R. & H.S. provided critical revisions. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Deborah R. Wahl or Britta Renner .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary table s1, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wahl, D.R., Villinger, K., König, L.M. et al. Healthy food choices are happy food choices: Evidence from a real life sample using smartphone based assessments. Sci Rep 7 , 17069 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17262-9

Download citation

Received : 05 June 2017

Accepted : 23 November 2017

Published : 06 December 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17262-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Financial satisfaction, food security, and shared meals are foundations of happiness among older persons in thailand.

- Sirinya Phulkerd

- Rossarin Soottipong Gray

- Sasinee Thapsuwan

BMC Geriatrics (2023)

Enrichment and Conflict Between Work and Health Behaviors: New Scales for Assessing How Work Relates to Physical Exercise and Healthy Eating

- Sabine Sonnentag

- Maria U. Kottwitz

- Jette Völker

Occupational Health Science (2023)

The value of Bayesian predictive projection for variable selection: an example of selecting lifestyle predictors of young adult well-being

- A. Bartonicek

- S. R. Wickham

- T. S. Conner

BMC Public Health (2021)

Smartphone-Based Ecological Momentary Assessment of Well-Being: A Systematic Review and Recommendations for Future Studies

- Lianne P. de Vries

- Bart M. L. Baselmans

- Meike Bartels

Journal of Happiness Studies (2021)

Exploration of nutritional, antioxidative, antibacterial and anticancer status of Russula alatoreticula: towards valorization of a traditionally preferred unique myco-food

- Somanjana Khatua

- Surashree Sen Gupta

- Krishnendu Acharya

Journal of Food Science and Technology (2021)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Will Healthy Eating Make You Happier? A Research Synthesis Using an Online Findings Archive

- Open access

- Published: 14 August 2019

- Volume 16 , pages 221–240, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Ruut Veenhoven ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5159-393X 1 , 2

29k Accesses

10 Citations

127 Altmetric

13 Mentions

Explore all metrics

Healthy eating adds to health and thereby contributes to a longer life, but will it also add to a happier life? Some people do not like healthy food, and since we spend a considerable amount of our life eating, healthy eating could make their life less enjoyable. Is there such a trade-off between healthy eating and happiness? Or instead a trade-on , healthy eating adding to happiness? Or do the positive and negative effects balance? If there is an effect of healthy eating on happiness, is that effect similar for everybody? If not, what kind of people profit from healthy eating happiness wise and what kind of people do not? If healthy eating does add to happiness, does it add linearly or is there some optimum for healthy ingredients in one’s diet? I considered the results published in 20 research reports on the relation between nutrition and happiness, which together yielded 47 findings. I reviewed these findings, using a new technique. The findings were entered in an online ‘findings archive’, the World Database of Happiness, each described in a standardized format on a separate ‘findings page’ with a unique internet address. In this paper, I use links to these finding pages and this allows us to summarize the main trends in the findings in a few tabular schemes. Together, the findings provide strong evidence of a causal effect of healthy eating on happiness. Surprisingly, this effect is not fully mediated by better health. This pattern seems to be universal, the available studies show only minor variations across people, times and places. More than three portions of fruits and vegetables per day goes with the most happiness, how many more for what kind of persons is not yet established.

Similar content being viewed by others

How the Exposure to Beauty Ideals on Social Networking Sites Influences Body Image: A Systematic Review of Experimental Studies

Timing Matters: A Longitudinal Study Examining the Effects of Physical Activity Intensity and Timing on Adolescents’ Mental Health Outcomes

An update on the prevalence of eating disorders in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Healthy eating, in particular a diet rich in fruit and vegetables (FV) adds to our health; primarily because it reduces our chances of contracting a number of eating related diseases (Oyebode et al. 2014 ; Bazzano et al. 2002 ; Liu et al. 2000 ). Since good health adds to happiness, it is likely that healthy diets will also add to happiness, but a firm connection has not been established.

In recent years, the relationship between obesity and mental states has begun to attract serious research interest (Becker et al. 2001 ; Rooney et al. 2013 ), as has the relationship between specific micro-nutrients and psychological health (Stough et al. 2011 ). As yet, there is little research on the relationship between nutrition and happiness.

It is worth knowing to what extent our eating habits affect our happiness. One reason is that most people are concerned about their happiness and look for ways to increase it. Most determinants of happiness are beyond our control, but what we eat is largely in our own hands. In this context, we would like to know whether there is a trade-off between healthy eating and happy living. Gains in length of life due to healthy eating may be counterbalanced by loss of satisfaction with life, as is argued in the debate on the benefits of drinking alcohol (Baum-Baicker 1985 ). If so, healthy eating may mean that we live longer, but not happier.

Empirical assessment of the effects of healthy eating on happiness is fraught with complications. One complication is that the effect of nutrition is probably not the same for everybody. Hence, we must identify what food pattern is optimal for what kind of person. A second problem is that happiness can influence nutrition behaviour, for example unhappiness can lead to the consumption of unhealthy comfort foods. Cause and effect must be disentangled. If a healthy diet does appear to add to happiness, then a third question arises: Is eating more healthy food always better or is there an optimum amount one should eat? For instance, is one apple a day enough to make us feel happy? Or will we feel better with four daily portions of fruit? How about small sins, such as a bar of chocolate or a daily glass of wine?

Research Questions

Is there a trade-of or between healthy eating and happiness? Or rather a trade-on , healthy eating adding to happiness? Or do the positive and negative effects balance?

Is this effect of healthy eating on happiness similar for everybody? If not, what kind of people profit from healthy eating and what kind of people do not?

Is the shape of the relationship between healthy eating and happiness linear? The healthier one’s diet, the happier one is? Or is there an optimum?

I explored answers to these three questions in the available research literature and took stock of the findings obtained in quantitative studies on the relation between healthy eating and happiness. I applied a new technique for research reviewing, that takes advantage of an on-line findings archive, the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven 2018a ), which allows us to present a lot of findings in a few easy to oversee tabular schemes.

To my knowledge, the research literature on this subject has not been reviewed as yet. One review has considered the observed effect of eating fruit and vegetables on psychological well-being (Rooney et al. 2013 ), however, this review does not really deal with happiness, as will be defined in “ Happiness ” section, but is about mental disorders, such as depression and anxiety.

Structure of the Paper

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. I define the key concepts in “ Concepts and Measures ” section; healthy eating and happiness and give a short account of happiness research. Next, I describe the new review technique in more detail: how the available research findings were gathered and how these are presented in an easy to overview way ( Methods section). Then I discuss what answers the available findings have provided for our research questions ( Results section). I found a clear answer to the first research question, but no clear answers to the second and third question. I discuss these findings in “ Discussion ” section and draw conclusions in “ Conclusions ” section.

Concepts and Measures

There are different view on what constitutes ‘healthy eating’ and ‘happiness’; for this reason, a delineation of these notions is required.

Healthy Eating

I follow the WHO ( 2018 ) characterization of a ‘healthy diet’ as involving’: 1) a varied diet, 2) rich in fruit and vegetables 3) a moderate amount of fats and oil and 4) less salt and sugar than usual these days. The typical Mediterranean diet is considered to fit these demands well. Unhealthy foods are considered to be rich in sugar and fat, such as processed meat, fast foods, sweets, cakes, sodas, deserts, alcohol and other foods high in calories, but low in nutritional content.

Throughout history, the word happiness has been used to denote different concepts that are loosely connected. Philosophers typically used the word to denote living a good life and often emphasize moral behaviour. ‘Happiness’ has also been used to denote good living conditions and associated with material affluence and physical safety. Today, many social scientists use the word to denote subjective satisfaction with life , which is also referred to as subjective well-being (SWB).

Definition of Happiness

In that latter line, I defined happiness as the degree to which an individual judge the overall quality of his/her life-as-a-whole favourably Footnote 1 (Veenhoven 1984 ) and in a later paper distinguished this definition of happiness from other notions of the good life (Veenhoven 2000 ). In this paper, I follow this conceptualization as it is also the focus of the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven 2018a ) from which the data reported in this paper are drawn.

Components of Happiness

Our overall evaluation of life draws on two sources of information: a) how well one feels most of the time and b) to what extent one perceives one is getting from life what one wants from it. I refer to these sub-assessments as ‘components’ of happiness, called respectively ‘hedonic level of affect’ and ‘contentment’ (Veenhoven 1984 ). The affective component tends to dominate in the overall evaluation of life (Kainulainen et al. 2018 ).

The affective component is also known as ‘affect balance’, which is the degree to which positive affective (PA) experiences outweigh negative affective (NA) experiences Positive experience typically signals that we are doing well and encourages functioning in several ways (Fredrickson 2004 ) and protects health (Veenhoven 2008 ). As such, this aspect of happiness was particularly interesting for this review of effects of healthy eating.

Difference with Wider Notions of Wellbeing

Happiness in the sense of the ‘subjective enjoyment of one’s life-as-a-whole’, should not be equated with satisfaction with domains of life, such as satisfaction with one’s life-style, one’s diet in particular. Likewise, happiness in the sense of the ‘subjective enjoyment of one’s life’ should not be equated with ‘objective’ notions of what is a good life, which are sometimes denoted using the same term. Though strongly related to happiness, mental health is not the same; one can be pathologically happy or be happy in spite of a mental condition.

Differences in wider notions of well-being are discussed in more detail in Veenhoven (15).

Measurement of Happiness

Since happiness is defined as something that is on our mind, it can be measured using questioning. Various ways of questioning have been used, direct questions as well as indirect questions, open questions and closed questions and one-time retrospective questions and repeated questions on happiness in the moment.

Not all questions used fit the above definition of happiness adequately, e.g. not the question whether one thinks one is happier than most people of one’s age, which is an item in the Subjective Happiness Scale (Lyobomirsky and Lepper 1999 ). Findings obtained using such invalid measures are not included in the World Database of Happiness and hence were not considered in this research synthesis. Further detail on the validity assessment of questions on happiness is available in the introductory text to the collection Measures of Happiness of the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven 2018b ) chapter 4. Some illustrative questions deemed valid for archiving in the WDH are presented below.

Question on overall happiness:

Taking all together, how happy would you say you are these days?

Questions on hedonic level of affect:

Would you say that you are usually cheerful or dejected?

How is your mood today? (Repeated several days).

Question on contentment:

How important are each of these goals for you?

How successful have you been in the pursuit of these goals?

Happiness Research

Over the ages, happiness has been a subject of philosophical speculation and in the second half of the twentieth century it also became the subject of empirical research. In the 1960’s, happiness appeared as a side-subject in research on successful aging (Neugarten et al. 1961 ) and mental health (Gurin et al. 1960 ). In the 1970’s happiness became a topic in social indicators research (Veenhoven 2017 ) and in the 1980s in medical quality of life research (e.g. Calman 1984 ). Since the 2000’s, happiness has become a main subject in the fields of ‘Positive psychology’ (Lyubomirsky et al. 2005 ) and ‘Happiness Economics’ (Bruni and Porta 2005 ). All this has resulted in a spectacular rise in the number of scholarly publications on happiness and in the past year (2017) some 500 new research reports have been published. To date (May 2018), the Bibliography of Happiness list 6451 reports of empirical studies in which a valid measure of happiness has been used (Veenhoven 2018c ).

Findings Archive: The World Database of Happiness

This flow of research findings on happiness has grown too big to oversee, even for specialists. For this reason, a findings archive has been established, in which quantitative outcomes are presented in a uniform format and are sorted by subject. This ‘World Database of Happiness’ is freely available on the internet at https://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl

Its structure is shown on Fig. 1 and a recent description of this novel technique for the accumulation of research findings can be found with Veenhoven ( 2019 ).

Start page of the World Database of Happiness, showing the structure of this findings archive

One of the subject categories in the collection of correlational findings is ‘Happiness and Nutrition’ (Veenhoven 2018c ). I draw on that source for this paper.

A first step in this review was to gather the available quantitative research findings on the relationship between happiness and healthy eating. The second step was to present these findings in an uncomplicated form.

Gathering of Research Findings

In order to identify relevant papers for this synthesis, I inspected which publications on the subject of healthy eating were already included of the Bibliography of World Database of Happiness, in the subject sections ‘ Health behaviour’ and consumption of ‘ Food ’. Then to further complete the collection of studies, various databases were searched such as Google Scholar, EBSCO, ScienceDirect, PsycINFO, PubMed/Medline, using terms such as ‘ happiness ’, ‘ life satisfaction ’, ‘ subjective well-being ’, ‘ well-being ’, ‘ daily affect ’, ‘ positive affect ’, ‘ negative affect ’ in connection with terms such as ‘ food ’, ‘ healthy food ’, ‘ fruit and vegetables ’, ‘ fast food ‘and ‘ soft drinks ’ in different sequences.

All reviewed studies had to meet the following criteria:

A report on the study should be available in English, French, German or Spanish.

The study should concern happiness in the sense of life-satisfaction (cf. Healthy Eating section). I excluded studies on related matters, such as on mental health or wider notions of ‘flourishing’.

The study should involve a valid measure of happiness (cf. Happiness section). I excluded scales that involved questions on different matters, such as the much-used Satisfaction With Life Scale (Diener et al. 1985 ).

The study results had to be expressed using some type of quantitative analysis.

Studies Found

Together, I found 20 reports of an empirical investigation that had examined the relationship between healthy eating and happiness, of which two were working papers and one dissertation. None of these publication s reported more than one study . Together, the studies yielded 47 findings.

All the papers were fairly recent, having been published between 2005 and 2017. Most of the papers (44.4%) were published in Medical Journals, including the International Journal of Behavioural Medicine, Journal of Health Psychology, The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, The Journal of Psychosomatic Research, The International Journal of Public Health, and Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology.

People Investigated

Together, the studies covered 149.880 respondents and 27 different countries. The publics investigated in these studies, included the general population in countries and particular groups such as students, children, veterans and medical patients. The majority of respondents belonged to a general public group (50%), students made up 27.8%, with children and veterans each forming 11.1%.

Research Methods Used

Most of the studies were cross-sectional 64.4%, longitudinal and daily food diaries accounted for 22% and 10.2% of the total number of studies respectively, and one experimental study accounted for 3.4%.

I present an overview of all the included studies, including information about population, methods and publication in Table 1 .

Format of this Research Synthesis

As announced, I applied a new technique of research reviewing, taking advantage of two technical innovations: a) The availability of an on-line findings-archive (the World Database of Happiness) that holds descriptions of research findings in a standard format and terminology, presented on separate finding pages with a unique internet address. b) The change in academic publishing from print on paper to electronic text read on screen, in which links to that online information can be inserted.

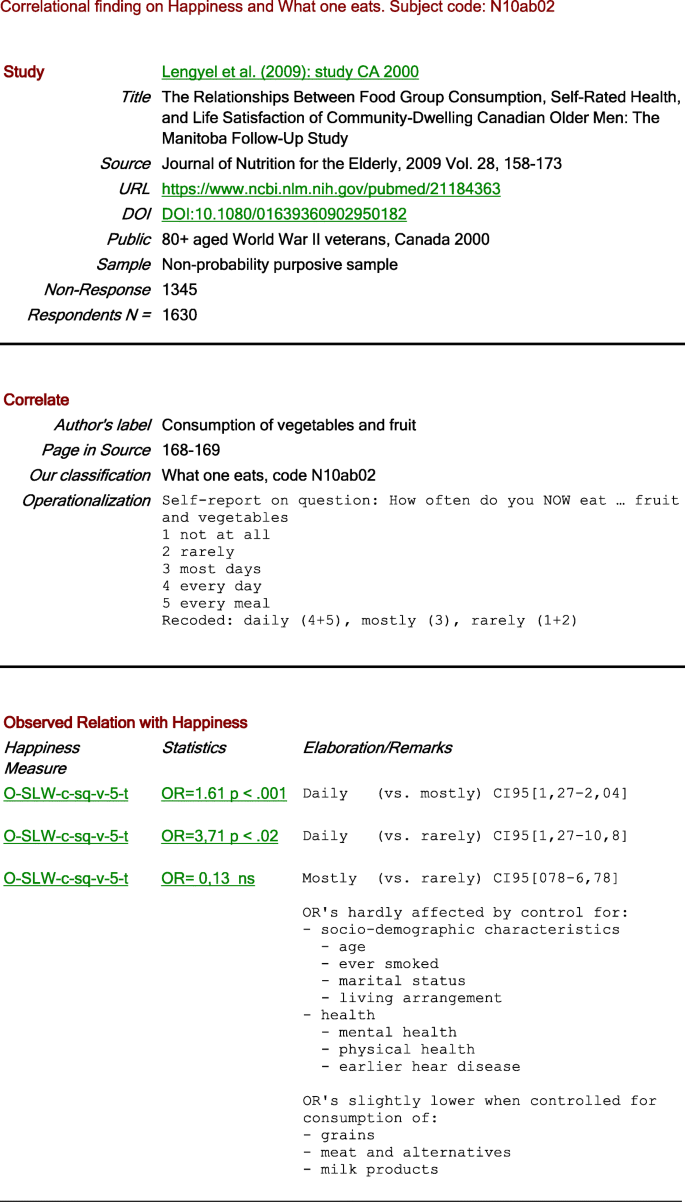

Links to Online Detail

In this review, I summarize the observed statistical relationships as +, − or 0 signs. Footnote 2 These signs link to finding pages in the World Database of Happiness, which serves as an online appendix in this article. If you click on a sign, one such a finding page will open, on which you can see full details of the observed relationship; of the people investigated, sampling, the measurement of both variables and the statistical analysis. An example of such an electronic finding page is presented in Fig. 2 . This technique allows me to present the main trends in the findings, without burdening the reader with all the details, while keeping the paper to a controllable size, at the same time allowing the reader to check in depth any detail they wish.

Example of an online findings page

Organization of the Findings

I first sorted the findings by the research method used and these are presented in three separate tables. I distinguished a) cross-sectional studies, assessing same-time relationships between diet and happiness (Table 2 ), b) longitudinal studies, assessing change in happiness following changes in diet (Table 3 ), and c) experimental studies, assessing the effect of induced changes in diet on happiness (Table 4 ).

In the tables, I distinguish between studies at the micro level, in which the relation between diet and happiness of individuals was assessed and studies at the macro level, in which average diet in nations is linked to average happiness of citizens.

I present kinds of foods consumed vertically and horizontally two kinds of happiness: overall happiness (life-satisfaction) and hedonic level of affect.

Presentation of the Findings

The observed quantitative relationships between diet and happiness are summarized using 3 possible signs: + for a positive relationship, − for a negative relationship and 0 for a non-relationship. Statistical significance is indicated by printing the sign in bold . See Appendix . Each sign contains a link to a particular finding page in the World Database of Happiness, where you can find more detail on the checked finding.

Some of these findings appear in more than one cell of the tables. This is the case for pages on which a ‘raw’ (zero-order) correlation is reported next to a ‘partial’ correlation in which the effect of the control variables is removed. Likewise, you will find links to the same findings page at the micro level and the macro level in Table 2 ; on this page there is a time-graph of sequential studies in Russia from which both micro and macro findings can be read.

Several cells in the tables remain empty and denote blanks in our knowledge.

Advantages and Disadvantages of this Review Technique

There are pros and cons to the use of a findings-archive such as the World Database of Happiness and plusses and minuses to the use of links to an on-line source in a text like this one.

Use of a Findings-Archive

Advantages are: a) efficient gathering of research on a particular topic, happiness in this case, b) sharp conceptual focus and selection of studies on that basis, c) uniform description of research findings on electronic finding pages, using a standard format and a technical terminology, d) storage of these finding pages in a well searchable database, e) which is available on-line and f) to which links can be made from texts. The technique is particular useful for ongoing harvesting of research findings on a particular subject.

Disadvantages are: a) the sharp conceptual focus cannot easily be changed, b) considerable investment is required to develop explicit criteria for inclusion, definition of technical terms and software, Footnote 3 c) which pays only when a lot of research is processed on a continuous basis.

Use of Links in a Review Paper

The use of links to an on-line source allows us to provide extremely short summaries of research findings, in this text by using +, − and 0 signs in bold or not, while allowing the reader access to the full details of the research. This technique was used in an earlier research synthesis on wealth and happiness (Jantsch and Veenhoven 2019 ) and is described in more detail in Veenhoven ( 2019 ). Advantages of such representation are: a) an easy overview of the main trend in the findings, in this case many + signs for healthy foods, b) access to the full details behind the links, c) an easy overview of the white spots in the empty cells in the tables, and d) easy updates, by entering new sign in the tables, possibly marked with a colour.

The disadvantages are: a) much of the detailed information is not directly visible in the + and – signs, b) in particular not the effect size and control variables used, and c) the links work only for electronic texts.

Differences with Traditional Reviewing

Usual review articles cannot report much detail about the studies considered and rely heavily on references to the research reports read by the reviewer, which typically figure on a long list at the end of the review paper that the reader can hardly check. As a result, such reviews are vulnerable to interpretations made by the reviewer and methodological variation can escape the eye.

Another difference is that the conceptual focus of many traditional reviews in this field is often loose, covering fuzzy notions of ‘well-being’ rather than a well-defined concept of ‘happiness’ as used here. This blurs the view on what the data tell and involves a risk of ‘cherry picking’ by reviewers. A related difference is that traditional reviews of happiness research often assume that the name of a questionnaire corresponds with its conceptual contents. Yet, several ‘happiness scales’ measure different things than happiness as defined in “ Healthy Eating ” section, e.g. much used Life Satisfaction Scale (Neugarten et al. 1961 ), which measures social functioning.

Still another difference is that traditional narrative reviews focus on interpretations advanced by authors of research reports, while in this quantitative research synthesis I focus on the data actually presented. An example of such a difference in this review, is the publication by Connor & Brookie (Conner et al. 2015 ) who report no effect of healthier eating on mood in the experimental group, while their data show a small but significant gain in positive affect and a small but insignificant reduction of negative effect (Table 3 ), which together denote a positive effect on affect balance.

Difference with Traditional Meta-Analysis

Though this research synthesis is a kind of meta-analysis, it differs from common meta-analytic studies in several ways. One difference is the above- mentioned conceptual rigor; like narrative reviews many meta-analyses take the names given to variables for their content thus adding apples and oranges. Another difference is the direct online access to full detail about the research findings considered, presented in a standard format and terminology, while traditional meta-analytic studies just provide a reference to research reports from which the data were taken. A last difference is that most traditional meta-analytic studies aim at summarizing the research findings in numbers, such as an average effect size. Such quantification is not well possible for the data at hand here and not required for answering our research questions. My presentation of the separate findings in tabular schemers provides more information, both of the general tendency and of the details.

Let us now revert to the research questions ( Structure of the Paper section) and answer these one by one.

Is there a Trade-Of between Healthy Eating and Happiness?

Or does healthy eating rather add to happiness or do the positive and negative effects balance.

This question was addressed using different methods, a) same-time comparison of diet and happiness (cross-sectional analysis) b) follow-up of change in happiness following change in diet (longitudinal) and c) assessing the effect on happiness of induced change in diet (experimental). The results are summarized in, respectively, Tables 2 , 3 and 4 .

Cross-Sectional Findings

Together I found 42 correlational findings, which are presented in Table 2 . Of these findings 14 concerned raw correlations, while 28 reflected the results of a multivariate analysis. In Table 2 I see only micro level studies.

There were 16 + signs, which indicates that people who eat healthy tend to be happier than people who do not. A few (3) – signs were linked to unhealthy eating habits, i.e. fast food, soft drinks and sweets, and as such support this pattern.

Not all the findings supported the view that healthy eating goes with greater happiness. Consumption of soft-drinks was positively related to overall happiness, though not significantly, while the correlation with affect balance was significantly negative. A high intake of high caloric protein and fat is generally deemed to be unhealthy but appeared in one case to go with greater overall happiness, a study among medical patients in Arkhangelsk in Russia, where the medical conditions and cold climate may have require a higher intake of such foods.

The findings were mixed with respect to the relation of happiness with consumption of animal products, dairy and meat. For these foods a positive relation with overall happiness was found and a negative relation with affect level, in the case of milk products both relations were insignificant.

Several studies report both raw correlations and partial ones for the same population. Controls reduced the effect size somewhat but did not change the direction of the correlation. Importantly, the control for health and other health behaviours in 8 studies Footnote 4 did not change the direction of the correlation.

Longitudinal Findings

The findings of two studies that assessed the change in happiness following change in diet are presented in Table 3 , one study at the micro level among students and another study at the macro-level among the general population in Russia. Both studies found positive correlations, indicating that healthier eating adds to one’s happiness. The effects of greater consumption of meat and milk were not significant. No control variables were used in these studies. The relationship between healthy eating and affect level was not investigated longitudinally.

Experimental Study

To date, there is only one study on the effect of induced change to a healthier diet on an individual’s happiness. In this study people were randomly assigned to an experimental group and stimulated in various ways to consume more fruit and vegetables (FV), among other things by providing vouchers for health foods and sending e-mail reminders. After 2 weeks of increased FV consumption, the participant’s mood level had increased more than those of the control group.

Together, these findings provide a clear answer to our first research question. The net effect of healthy eating on happiness tends to be positive. If there is any trade-off at all, this is apparently more than compensated by the trade-on . The positive relationship is robust across research methods and measures of happiness.

Is this Effect of Healthy Eating on Happiness Similar for Everybody?

If not, what kind of people profit from healthy eating and what kind of people do not.

The 19 studies reported here cover a wide range of populations, the general public in several parts of the world, children, students, church members, medical patients and elderly war veterans. No great differences in the correlation between diet and happiness appear in these findings, though children seem to be happier when allowed to consume sweets and soft drinks. The cross-national study by Grant et al. ( 2009 ) observed some differences in strength of the correlation between healthy eating and happiness across part of the world, but no difference in direction of the correlation. The micro-level studies by Pettay ( 2008 ) and Warner et al. ( 2017 ) found no differences between males and females, while Ford et al. ( 2013 ) found a slightly bigger negative effect of unhealthy eating among women than among men.

The observed positive effect of healthy eating on happiness seems to be universal. Possible differences in what diet provides the most happiness for whom have not (yet) been identified.

Is the Shape of The Relationship Linear; the Healthier One’s Diet, the Happier One Is?

Or is there an optimum, if so what is optimal for whom.

Two studies find a linear relation between happiness and the number of portions fruits and vegetables per day, Lesani et al. ( 2016 ) among students in Iran and Blanchflower et al. ( 2013 ) among the general public in the UK, the latter study up to 7–8 portion a day. Another study observed an optimum at the lower level of 3–4 portions a day among female Iranian students (Fararouei et al. 2013 ). These thee studies suggest that the optimum is at least beyond three portions a day. As yet the focus of research has been on particular kinds of food, while the relationship between happiness and total diet composition has not been investigated.

Together, our findings leave no doubt that healthy eating ads to happiness, frequent consumption of fruit and vegetables in particular.

Causal Effect

Though happiness may influence nutrition behaviour, happier people being more inclined to follow a healthy diet, there is strong evidence for a causal effect of healthy eating on happiness. Spurious correlation is unlikely to exist, since correlations remain positive after controlling for many different variables. Causality is strongly suggested by 3 out of the 4 longitudinal findings and the experimental study.

This is not to say that healthy eating will always add to the happiness of everybody, but the trend is sufficiently universal and strong to be used in policies that aim at greater happiness for a greater number of people, such as in happiness education.

Causal Paths

Healthy eating will add to good health and good health will add to happiness. An unexpected finding is that the effect of healthy eating on happiness is not fully mediated by better health. As mentioned in “ Is there a Trade-Of between Healthy Eating and Happiness? ” section, significant positive correlations remain when health is controlled. This means that healthy eating also affects happiness in other ways. As yet I can only speculate about what these ways are. Possibly effects are that healthy eaters attract nicer people or that intake of fruit and vegetables has a direct effect on mood.

Limitations

This first synthesis of the research on happiness and healthy eating draws on 20 empirical studies, which together yielded 47 findings. Though these results provide strong indications of a positive effect of healthy eating on happiness, we need more research to be sure. This research synthesis limits to happiness defined as the subjective enjoyment of one’s life as a whole and measure that matter adequately. This conceptual focus has a piece, we came to know more about less. The available research findings do not allow a traditional meta-analysis, both because of the limited numbers and their heterogeneity. Hence, we cannot yet compute effect sizes or test statistical significance of differences.

Topics for Further Research

Although we now know that healthy eating tends to make one’s life more satisfying, we do not know in much detail what particular diets are the most conducive to the happiness of what kinds of people. We are also largely in the dark about the causal mechanisms involved. The focus of current research is very much on particular food items, consumption of fruit and vegetables in particular. Future research should pay more attention to the effect of total diets on happiness.

Conclusions

Healthy eating adds to happiness, not just by protecting one’s health but also in other, as yet unidentified, ways. This finding deserves to be drawn to the public’s attention. People should know that changing to a healthier diet will not be at the cost of their happiness but will add to it. Faulty beliefs and misleading advertisements should be counter-balanced by this established fact.

Likewise, Diener (26) defined ‘life satisfaction’ as an overall judgement of one’s life.

The technique also allows summarization in a number, which can be presented in a stem-leaf diagram, or in short verbal. Statements, such as ‘U shaped relationship’

The archive can be easily adjusted for other subjects. The software is Open Source