TRY OUR FREE APP

Write your book in Reedsy Studio. Try the beloved writing app for free today.

Craft your masterpiece in Reedsy Studio

Plan, write, edit, and format your book in our free app made for authors.

Blog • Perfecting your Craft

Posted on Aug 15, 2018

What is an Unreliable Narrator: Definition and Examples

In literature, an unreliable narrator is a character who tells a story with a lack of credibility. There are different types of unreliable narrators (more on that later), and the presence of one can be revealed to readers in varying ways — sometimes immediately, sometimes gradually, and sometimes later in the story when a plot twist leaves us wondering if we’ve maybe been a little too trusting.

While the term “unreliable narrator” was first coined by literary critic Wayne C. Booth in his 1961 book, The Rhetoric of Fiction , it’s a literary device that writers have been putting to good use for much longer than the past 80 years. For example, "The Tell-Tale Heart" published by Edgar Allan Poe in 1843 utilizes this storytelling tool, as does Wuthering Heights , published in 1847.

But wait, is any narrator really reliable?

This discussion can lead us down a proverbial rabbit hole. In a sense, no, there aren’t any 100% completely reliable narrators. The “ Rashomon Effect ” tells us that our subjective perceptions prohibit us from ever having a totally clear memory of past events. If each person subjectively remembers something that happened, how do we know who is right? "Indeed, many writers have used the Rashomon Effect to tell stories from multiple first-person perspectives — leaving readers to determine whose record is most believable." (Check out As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner for an example).

For the purpose of this article, however, we will refer to narrators who are purposefully unreliable for a specific narrative function.

Literary function of an unreliable narrator

Fiction that makes us question our own perceptions can be powerful. An unreliable narrator can create a lot of grey areas and blur the lines of reality, allowing us to come to our own conclusions.

Fallible storytellers can also create tension by keeping readers on their toes — wondering if there’s more under the surface, and reading between the lines to decipher what that is. Unreliable narrators can make for intriguing, complex characters: depending on the narrator’s motivation for clouding the truth, readers may also feel more compelled to keep reading to figure out why the narrator is hiding things.

Finally, all unreliable narrators are first-person: they live in the world of the story and will have an inherent bias or perhaps even an agenda. While you may find an unreliable narrator who's written in the second-person or third-person point of view, this is generally rare.

PRO-TIP: If you'd like to see the different points of view in action, check out this post that has plenty of point of view examples .

Types of unreliable narrators

Just like trying to classify every type of character would be an endless pursuit, so is trying to list every type of unreliable narrator. That said, we've divided these questionable raconteurs into three general types to better understand how they work as a literary device.

1) Deliberately Unreliable: Narrators who are aware of their deception

This type of narrator is intentionally lying to the reader because, well, they can. They have your attention, the point of view is theirs, and they’ll choose what to do with it, regardless of any “responsibility” they might have to the reader.

A quick note about this kind of narrator: people want to read about characters they can connect with or relate to . This is one of the tricky parts of writing this kind of narrator: the character has to be compelling enough that we’ll keep connecting with them even if we suspect we’re being misled. We don’t have to necessarily like them, but we need to understand them. For instance, even Alex from A Clockwork Orange has an underlying humanity: his desire for individual freedom above all. His flagrant lies are therefore an exercise of his freedom.

2) Evasively Unreliable: Narrators who unconsciously alter the truth

The motivations for this kind of narrator are often quite muddy — sometimes it’s simple self-preservation, other times it’s slightly more manipulative. Sometimes the narrator isn’t even aware they are twisting the truth until later in the book. Their unreliability often stems from the need to tell the story in a way that justifies something, and their stories are often embellished or watered down.

These kinds of contradictory characters whose mindsets aren’t clear can keep readers anxiously waiting for the narrator’s moment of clarity — drawing their own conclusions all the while.

FREE COURSE

Understanding Point of View

Learn to master different POVs and choose the best for your story.

3) Naively Unreliable: Narrators who are honest but lack all the information

Unlike the previous two types, this type of narrator is not unreliable on purpose — they simply lack a traditional, “greater understanding.” This kind of unreliability can allow the reader to view your story with fresh eyes. The narrator’s “unorthodox” interpretations might only provide us with partial explanations of what’s going on, forcing us to dig a little deeper and connect the dots. These naive narrators can also encourage readers to take more significant notice of things we might’ve taken for granted.

Craft tip: Don’t cheat the reader. Great novels inspire readers to come back and find new meaning and elements they hadn’t yet discovered the first time. This can be especially true of stories told by unreliable narrators. If you employ this literary device gradually throughout the novel, ensure you leave clues for your readers along the way. Drop hints that make us question the validity of our source and have us eagerly reading to find the next clue that will act as another part of the story-puzzle. If you suddenly reveal out of nowhere that the narrator hasn’t been giving us all the facts in an abrupt twist, readers will feel they have been cheated.

Unreliable narrator examples

Once you’ve determined what your narrator’s motivation for being unreliable is — or isn’t! — you can start thinking about how you will use this literary device to achieve your narrative goal.

If you’re toying with the idea of writing a story that fills readers’ mind with question marks, here are a few examples of wavering yarn-spinners from literature to help you get started (spoilers ahead!).

Deliberately Unreliable

A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess The protagonist and narrator, Alex, is a notoriously brutal character who does not feel a sense of responsibility to anything or anyone other than himself. His lack of credibility feels deliberate and coy straight off the bat. He speaks ' Nadsat ,' a dialect that confounds other characters and keeps the reader on their back foot. He is also a skilled manipulator who excels in getting others to let their guards down.

Alex is presumably aware that the narrative audience will be repulsed by his accounts, yet he repeatedly refers to the audience as “brother” — a term that implies familiarity and camaraderie. Readers can never be quite certain if they’re being confided in or reeled in as another one of Alex’s deceitful games.

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd by Agatha Christie While some fallible storytellers may lack credibility because they deliver false or skewed information, others are untrustworthy because of the information that they omit. They leave out key pieces of information without which the reader is left in the dark. This is the case in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd , whose narrator — Dr. Sheppard — is one of the most classic unreliable examples.

Dr. Sheppard takes us through Poirot’s investigation into the murder of Roger Ackroyd. He is genial and rather neutral throughout the story, seeming to explain the events as they happened without bias. Only at the end is it revealed that this voice we have allowed to carry us through the novel is actually the voice of the murderer. Sheppard also reveals at the end that he started writing the manuscript with the intention of documenting Poirot’s failure. Therefore the entire manuscript was based on a detailed lie by omission. 100% deliberate deception!

PRO-TIP: To read more of the Queen of Mystery's works, go here for ten of Agatha Christie's best stories .

Evasively Unreliable

Life of Pi by Yann Martel At the end of the novel, when Pi wraps up his fantastical story of being stranded at sea with a group of animals, we hear another version of his story — where the animals are replaced by humans, and the events are much more tragic and disturbing. Pi never concretely confirms which story is true: is the first version simply a coping mechanism or is the second version simply to placate the unbelieving cops? Readers are faced with the choice to pick which story they believe, as the narrator does not make it clear — and even if he did specify which version is the true one, would we believe him?

We Need To Talk About Kevin by Lionel Shriver Narrated through Eva’s letters to her husband, We Need To Talk About Kevin takes place in the aftermath of her son committing a deadly attack at his high-school. It’s not easy to be totally honest with ourselves — especially when it comes to looking within and seeing where we might be at fault.

The only thing objective about Eva is that her accounts are subjective, and we are left to come to our own conclusions based on her descriptions. Was Kevin inherently sociopathic? Did Eva do her best as a mother or did she reject Kevin as an unwanted outcome? How much blame should Eva shoulder for Kevin's actions? We won’t find the answers in Eva’s letters, but they do prompt us to reflect on these questions in the first place.

Naively Unreliable

Room by Emma Donoghue Five-year-old Jack is an often quoted example of an unknowingly unreliable narrator. Jack is not withholding information from the reader or providing false information. He simply reports the facts as he sees them — however, as a child, his accounts often lack insight into the implications of what is happening around him. Because of this, even though Jack’s voice is a poignantly honest one, his narration is not a source of information that can be taken at face value.

Forrest Gump by Winston Groom Forrest is another example of a narrator who’s not deliberately unreliable in order to pull the wool over the readers’ eyes or to “save face.” From the outset, we are aware that Forrest doesn’t comprehend things like the “average” person does, and we’re aware that we might not be able to take everything he says at face value. This is confirmed when Forrest begins detailing his life, which is peppered with stories about major events from history that he was apparently intimately involved in. We can’t be certain that he’s not telling the truth, but it would be quite the life if he is.

An unreliable narrator breaks the conventional relationship of trust between a reader and a storyteller. However, the key is that you don’t want to shatter that trust entirely, because you’re likely to lose the reader. Ensure your unreliable narrator has a clear purpose for being unreliable, employ just enough mist around the narrator’s accounts to put question marks in our minds, give us the underlying sense that there’s more to the story, and you’ll be able to foster a connection between the reader and narrator that has the pages of your book flipping.

Who are some of your favorite unreliable narrators from literature? Have you ever tried writing one yourself? Leave any thoughts or questions in the comments below!

2 responses

Hermione 11675 says:

08/05/2019 – 12:28

Who is the author of this article? I would like to cite it for a school paper if that's all right, but I need to know the author's name. -- California high school student

R. Raniere says:

26/10/2019 – 16:41

I disagree that all unreliable narrators are first-person narrators. Consider Lane Dean, Jr., the protagonist in David Foster Wallace's "Good People" in which the narrative voice is third-person limited. In this case the narrator is unreliable because the reader's understanding emerges from the thoughts and descriptions of Lane Dean alone, which are not entirely credible given his own lack of understanding of where he is vis-a-vis his Christian beliefs and values, and his leaning to see things as he would like, rather than as they may be. This leaves the reader to deal with a questionable resolution.

Comments are currently closed.

Continue reading

Recommended posts from the Reedsy Blog

What is Tone in Literature? Definition & Examples

We show you, with supporting examples, how tone in literature influences readers' emotions and perceptions of a text.

Writing Cozy Mysteries: 7 Essential Tips & Tropes

We show you how to write a compelling cozy mystery with advice from published authors and supporting examples from literature.

Man vs Nature: The Most Compelling Conflict in Writing

What is man vs nature? Learn all about this timeless conflict with examples of man vs nature in books, television, and film.

The Redemption Arc: Definition, Examples, and Writing Tips

Learn what it takes to redeem a character with these examples and writing tips.

How Many Sentences Are in a Paragraph?

From fiction to nonfiction works, the length of a paragraph varies depending on its purpose. Here's everything you need to know.

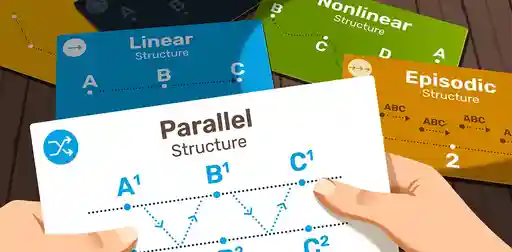

Narrative Structure: Definition, Examples, and Writing Tips

What's the difference between story structure and narrative structure? And how do you choose the right narrative structure for you novel?

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

How good are your theme-detecting skills?

Take our 1-minute quiz to find out.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

Unreliable Narrator: Mastering the 8 Layers of Deceptive Storytelling

Table of Contents

There’s nothing quite as exhilarating as realizing that the story you’re engrossed in has an unreliable narrator . This tantalizing narrative technique introduces an unexpected layer of complexity and intrigue to the plot, challenging the reader to untangle truth from deception. An unreliable narrator can transform a straightforward storyline into a labyrinth of mystery and suspense, where each revelation might just be another illusion. But what is an unreliable narrator, and why has this narrative tool become so popular in literature and film? In this exploration, we’ll delve into the world of unreliable narrators, highlighting its potential pitfalls and immense rewards, with a special nod to the ghostwriting domain.

What is an Unreliable Narrator?

At its core, an unreliable narrator is a character who tells a story but whose credibility is compromised. This could be due to a variety of reasons, ranging from deliberate deception or omission to a lack of self-awareness or even mental instability. The concept fundamentally challenges the notion of objective truth in storytelling, inviting readers or viewers to question the reality presented to them.

Such a character brings a unique dynamic to the narrative, as the audience is left to interpret and judge the story’s events. They must discern fact from fiction, often revisiting their initial perceptions as new information or perspectives are revealed. This complex relationship between the narrator, the narrative, and the audience creates a sense of engagement and intellectual stimulation that can make stories with unreliable narrators especially memorable.

Fundamentally, an unreliable narrator disrupts the comfortable, often passive experience of consuming a story. Instead, it prompts us to become active participants, constantly questioning, doubting, and reassessing what we think we know. This interaction generates a level of suspense and engagement that can elevate a story, making it resonate long after the last page is turned or the final credits roll.

Why Use an Unreliable Narrator?

So, why would a writer choose to use an unreliable narrator? What benefits can this narrative strategy offer? To answer these questions, we need to delve deeper into the elements that make a story engaging and impactful.

Unpredictability is a key factor that keeps audiences engaged in a narrative. When we can’t predict what will happen next, we become more invested in the story. The unreliable narrator is a master of unpredictability. With their distorted perception or dishonest narration, they can continuously surprise the audience, ensuring that the plot remains intriguing throughout.

Moreover, the unreliable narrator encourages active engagement. In a conventional narrative, audiences usually accept the narrated events at face value. However, when dealing with an unreliable narrator, audiences are prompted to think more critically about the events and characters. They must piece together the true narrative from the clues and contradictions presented, fostering a deeper connection with the story.

An unreliable narrator can also add depth to a character. Their unreliability often stems from personal issues like mental illness, trauma, or moral ambiguity. By giving audiences glimpses of these underlying issues, the writer can create a more rounded and intriguing character.

But perhaps most compelling is the way the unreliable narrator reflects the complexity of truth and perception. It prompts audiences to question their understanding of reality, echoing the subjective nature of our own experiences and perceptions. This deeper, more philosophical engagement can make stories with unreliable narrators more memorable and thought-provoking.

When is the Use of an Unreliable Narrator Appropriate and When is it Not?

Employing an unreliable narrator can significantly amplify the intrigue and depth of a story. However, this tool isn’t suitable for all narratives. Understanding when to use this device—and when not to—is crucial to delivering an impactful story.

In stories aiming to generate suspense, create surprise twists, or delve into the psyche of a complex character, an unreliable narrator can work wonders. These narratives thrive on uncertainty and reap the benefits of active audience engagement. Stories addressing subjective experiences, memory, or the nature of truth also benefit from this narrative style, as the unreliable narrator inherently challenges the concept of a singular, objective truth.

On the other hand, stories that require a clear, consistent perspective may not benefit from an unreliable narrator. For instance, narratives that aim to educate or inform, such as historical accounts or instructional texts, require a dependable voice. Similarly, stories focusing on external conflicts rather than internal dynamics might be better served by a reliable narrator. An unreliable narrator might also be inappropriate in narratives targeting audiences that prefer a more straightforward, less ambiguous storytelling style.

An important factor to consider is that the use of an unreliable narrator requires skillful execution. Poorly handled, it can lead to reader or viewer frustration, confusion, and a sense of being “tricked” rather than engaged. Thus, it’s essential to consider whether the narrative and the writer are equipped to handle this intricate tool.

Unreliable Narrator in Movies

The use of an unreliable narrator isn’t confined to the written word. Many filmmakers have harnessed this technique to deliver unforgettable cinematic experiences. Below, we will delve into 10 movies that masterfully use unreliable narrators to create engaging, suspenseful narratives.

- “Fight Club” (1999): David Fincher’s cult classic employs an unreliable narrator to stunning effect. As the protagonist’s mental stability unravels, the audience grapples with a narrative filled with disorienting distortions and revelations.

- “The Sixth Sense” (1999): M. Night Shyamalan’s masterpiece takes advantage of the unreliable narrator to craft one of cinema’s most memorable twist endings. Throughout the film, we’re led to perceive the world from Dr. Malcolm Crowe’s perspective, only to be startled by the reality in the final scenes.

- “Gone Girl” (2014): This psychological thriller relies on two unreliable narrators to weave a complicated tale of deception and manipulation. The dueling narratives of Nick and Amy Dunne keep the audience questioning who to believe.

- “Memento” (2000): Christopher Nolan’s mind-bending thriller uses the unreliability of Leonard, who suffers from anterograde amnesia, to build an intricate narrative that unfolds in a non-linear fashion, leaving the audience piecing together fragments of truth.

- “Shutter Island” (2010): In this Martin Scorsese-directed mystery, the unreliable narration stems from the troubled mental state of the protagonist, leaving audiences constantly guessing about the truth of Ashecliffe Hospital.

- “American Psycho” (2000): The film dives deep into the disturbed mind of Patrick Bateman, whose narration is as unreliable as it is chilling. The line between reality and Bateman’s violent delusions is masterfully blurred, unsettling viewers and prompting debate about the film’s events.

- “Rashomon” (1950): This seminal film by Akira Kurosawa offers four conflicting accounts of the same event, pioneering the use of unreliable narrators in cinema and exploring the subjective nature of truth.

- “A Beautiful Mind” (2001): The story of brilliant mathematician John Nash grapples with his schizophrenia through the use of an unreliable narrator, with reality only unfolding as Nash comes to terms with his condition.

- “The Usual Suspects” (1995): In this neo-noir film, the enigmatic Verbal Kint spins a complex web of tales, leaving audiences questioning the truth behind the infamous Keyser Söze.

- “Primal Fear” (1996): The film employs an unreliable narrator to craft a shocking twist ending. The defendant Aaron, initially portrayed as innocent and naïve, leaves both the audience and his lawyer questioning what is real.

Using an unreliable narrator can create enthralling narratives that keep audiences guessing. However, like any narrative tool, its effectiveness is dependent on skillful execution. The films listed above exemplify the power of this narrative device when handled with finesse.

Unreliable Narrator in Books

Similarly, books have long embraced the use of unreliable narrators to create intricate, captivating narratives. The following are nine books that use this technique to great effect.

- “The Catcher in the Rye” by J.D. Salinger: The teenage protagonist, Holden Caulfield, is an emblem of adolescent rebellion and confusion. His account of events is colored by his strong emotions and immature perspective.

- “Gone Girl” by Gillian Flynn: In this psychological thriller, husband and wife, Nick and Amy, narrate alternating chapters, both proving to be unreliable as their marriage unravels.

- “Fight Club” by Chuck Palahniuk: As in the film, the novel uses the unreliability of the protagonist’s narration to draw readers into a chaotic world of anarchy and rebellion.

- “Life of Pi” by Yann Martel: The story, narrated by Pi Patel, includes wild, fantastical elements that lead readers to question the veracity of his tale.

- “The Girl on the Train” by Paula Hawkins: The novel’s main character, Rachel, is a severe alcoholic, and her blackouts lead to significant gaps in her narrative.

- “Atonement” by Ian McEwan: Narrator Briony Tallis, in her pursuit of atonement, crafts a story that may or may not reflect the real events, leaving readers questioning her account.

- “American Psycho” by Bret Easton Ellis: Like its film adaptation, the novel uses Patrick Bateman’s unstable mental state to blur the line between reality and hallucination.

- “The Tell-Tale Heart” by Edgar Allan Poe: This short story’s narrator, who is trying to convince the reader of his sanity, vividly describes a murder he committed, creating an unsettling reading experience.

- “Rebecca” by Daphne du Maurier: The nameless narrator’s account of life at Manderley is skewed by her feelings of inferiority and paranoia, which color her perception of Rebecca and Maxim de Winter.

The art of employing an unreliable narrator in literature provides readers with an interactive reading experience, causing them to question and actively engage with the text. However, like in film, this narrative tool must be carefully handled to prevent it from becoming a source of reader frustration.

Pros and Cons of Using Unreliable Narrators

Unreliable narrators can be a powerful literary and cinematic tool when employed correctly. However, they also come with a set of potential pitfalls.

- Reader Engagement: The use of an unreliable narrator can engage readers in the narrative as they are prompted to question and investigate the narrative presented to them. This increases their active participation in deciphering the plot and characters.

- Richness and Depth: Unreliable narrators allow for the creation of complex and multi-faceted characters. Their flaws, biases, and unique perspectives contribute to the depth and richness of the narrative.

- Plot Twists and Surprises: Unreliable narrators can be used to introduce plot twists, making for exciting, unpredictable storytelling. When the reliability of the narrator is brought into question, it opens up numerous possibilities for shocking reveals and twists.

- Reader Confusion and Frustration: If not handled carefully, an unreliable narrator can lead to confusion and frustration. Readers might feel misled or cheated if the unreliability is not signaled or managed properly.

- Complexity in Writing: Writing from the perspective of an unreliable narrator requires skill and delicacy. Balancing between maintaining reader trust and introducing doubt can be challenging.

- Lack of Closure: Stories with unreliable narrators might not have definitive conclusions, as the truth is often obscured or subjective. This can be unsatisfying for some readers who prefer a clear resolution.

Unreliable narrators indeed bring a unique dynamic to storytelling, enriching it with their personal biases, flawed perceptions, and occasionally, deliberate deceptions. However, their use comes with a set of challenges and potential pitfalls that writers must navigate carefully.

Wrapping Up the Unpredictability: The Unreliable Narrator

From the winding alleys of mysteries to the unsettling corners of psychological thrillers, from the surreal landscapes of magical realism to the gritty terrains of hard-boiled noir, the unreliable narrator is a versatile and powerful storytelling tool. Employed adeptly, it can lend a story layers of complexity, intrigue, and emotional depth.

The use of an unreliable narrator invites readers to step beyond the traditional role of a passive recipient of the story, compelling them to become active participants in the unfolding narrative. As they navigate the labyrinth of unreliable narration, readers must parse truth from falsehood, appearance from reality, and memory from fabrication. This engaged reading experience can make the narrative more memorable and impactful.

However, as with all powerful tools, the unreliable narrator comes with its challenges. Misused, it can breed confusion and frustration, alienate readers, and weaken the narrative structure. Therefore, it’s crucial for writers to strike a balance—enough uncertainty to stir intrigue, but not so much as to obscure the narrative.

In the hands of a skillful writer, an unreliable narrator is not merely a teller of tales but an enigma to be decoded, a mystery intertwined with the larger narrative mystery. This narrative strategy, while requiring careful handling, opens up a wealth of storytelling possibilities, breathing life into narratives and delivering reading experiences that resonate, surprise, and provoke thought.

To borrow a quote from the book “The Things They Carried” by Tim O’Brien, an excellent example of the unreliable narrator, “A thing may happen and be a total lie; another thing may not happen and be truer than the truth.” Indeed, the unreliable narrator blurs the line between fact and fiction, challenging us to question, seek, and understand – a testament to the transformative power of storytelling.

“Life of Pi” by Yann Martel and “Gone Girl” by Gillian Flynn are other masterpieces in the realm of literature that utilize the concept of an unreliable narrator masterfully. These are must-reads for anyone interested in understanding this narrative technique better.

So, the next time you encounter an unreliable narrator, remember to enjoy the journey through the labyrinth of their narrative, and appreciate the layers of complexity they add to the story. After all, isn’t life itself a tale told by an unreliable narrator?

Click here to contact The Writing King to discuss your project today!

- Recent Posts

- 12 Reasons Why TikTok Sucks: A Critical Analysis - May 11, 2024

- Writing a How to Book: 10 Powerful Tips - May 11, 2024

- How to be a Book Writer: 8 Powerful Steps - May 10, 2024

16 thoughts on “ Unreliable Narrator: Mastering the 8 Layers of Deceptive Storytelling ”

Thank you for helping me understand this kind of narrator. Thanks a lot for sharing.

When a storyteller can hook the readers, that is an amazing talent. something not easy to accomplish but very good. Interesting post and love that its also informative.

Its crazy where my head went when I first heard unreliable writer. Now it’s the only thing I want to be as a writer lol.

It is truly amazing how storytelling has the power to transform a narrative and engage readers. The technique adds layers of complexity that intrigue readers and make the story more interesting. However, using an unreliable narrator can be challenging. When handled with care, it can still be a powerful tool for writers.

Ah, this is so insightful! It takes a really clever writer to craft an unreliable narrator, and ti make it truly believable.

Shutter Island is a great example of an unreliable narrator! Especially with that shocker ending.

We had to read the Tell-tale Heart in high school, and then we went to see a theater production of it. The use of an unreliable narrator makes for a memorable story. The only other movies and books that you mention that I am familiar with include A Beautiful Mind, and Life of Pi. I would say that perhaps this isn’t my favorite form of storytelling, but now that I know what an unreliable narrator is, thanks to this article, I will be more willing seek out these types of stories.

Unreliable narrators add a captivating twist to storytelling! Mastering the art of deceptive storytelling with 8 layers opens up a world of intrigue and suspense.

I loved this article because I have always had questions about an unreliable narrator. First, I was trying to think of movies that had unreliable narrators, and I thought of Memento as an example. Oddly, I have not read very many books with unreliable narrators, but yes, Rebecca was a fine example for me. I was so young when I read The Catcher In The Rye and The Tell-Tale Heart, and my teachers never introduced us to the convention of the unreliable narrator, so I don’t remember thinking about that when I read them both. Now I especially need to go back and reread The Tell-Tale Heart and check it out! Thank you for this!

I love a good unreliable narrator, and I particularly enjoyed reading Rebecca. Your straightforward explanation is going to help me explain this craft to my students, thank you!

Great insight on unreliable narrators! Loved your exploration of its use in literature and film. Can’t wait for more thought-provoking analyses!

Reading this post has highlighted to me the differences between the different types of narrators. It’s very interesting how you have explained it and demonstrated how it’s used in different types of books and films.

I would definitely say that having an unreliable narrator is a unique spin. I never really thought about that before!

I have never read a book with an unreliable narrator and I am glad to learn more about them. Thank you!

Ooohhhh….thank you for educating me on this kind of narrator. It will be so cool to deploy them in dialogues, of my writing.

I’m very intrigued by this kind of story. I’ve never read a book with an unreliable narrator before, and I think it sounds pretty darn great.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst

- < Previous

Home > ETDS > Masters Theses > 463

Masters Theses

Off-campus UMass Amherst users: To download campus access dissertations, please use the following link to log into our proxy server with your UMass Amherst user name and password.

Non-UMass Amherst users: Please talk to your librarian about requesting this dissertation through interlibrary loan.

Dissertations that have an embargo placed on them will not be available to anyone until the embargo expires.

The Unreliable Narrator: Simplifying the Device and Exploring its Role in Autobiography

James Ferry , University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow

Access Type

Open Access Thesis

Document Type

Degree program, degree type.

Master of Arts (M.A.)

Year Degree Awarded

Month degree awarded.

The primary goal of this paper is to gain a better understanding of the unreliable narrator as a literary device. Furthermore, I argue that the distance between an author and narrator in realist fiction can be simulated in autobiographical prose. While previous studies have focused mainly on extra- and intertextual incongruities (factual inaccuracies; disparities between two nonfiction texts), the present study attempts to demonstrate that the memoirist can employ unreliable narration intratexually as a rhetorical tool. The paper begins with some examples of how the unreliable narrator is used, interpreted, misused and misinterpreted. The device’s troubled history is examined—Wayne Booth and James Phelan have argued for an encoded strategy on the part of the (implied) author while Tamar Yacobi and Ansgar Nünning have embraced a reader-oriented model—as well as the recent (and in my opinion, inevitable) convergence of the rhetorical and cognitive/constructivist models. Aside from “What is the unreliable narrator,” two questions underlie the present study: 1) Does a fiction writer using homodiegetic narration have an obligation to adhere to formal mimeticism (do we believe it)? 2) Being that unreliable narrators are so prevalent in everyday life, why is the device, in nonfiction, considered almost verboten? Two texts are analyzed for the first question: Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby is argued to be a mimetically successful fictive “memoir” penned by a disillusioned, albeit reliable, narrator. Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day is presented as a synthetically flawless example of unreliable narration, but alas, a mimetic failure. Likewise, two texts are analyzed for the second question: Nick Flynn’s Another Bullshit Night in Suck City is viewed through the lens of overt fiction as a means of depicting uncertainty in autobiography. Similarly, Richard’s Wright’s Black Boy , with its overarching themes of survival and deception, is examined for the narrator’s use of “tall tales.” The critical and commercial success of both books suggests that the unreliable narrator does indeed have a place in autobiography—provided that the device is employed in service of a greater truth.

https://doi.org/10.7275/9500156

First Advisor

David Fleming

Second Advisor

Nicholas Bromell

Third Advisor

Janis Greve

Recommended Citation

Ferry, James, "The Unreliable Narrator: Simplifying the Device and Exploring its Role in Autobiography" (2017). Masters Theses . 463. https://doi.org/10.7275/9500156 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/463

Since March 24, 2017

Included in

English Language and Literature Commons

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Disciplines

Author Corner

- Submission Guidelines

- Login for Faculty Authors

- Faculty Author Gallery

- Submit Thesis

- University Libraries

- UMass Amherst

This page is sponsored by the University Libraries.

© 2009 University of Massachusetts Amherst • Site Policies

Privacy Copyright

Vous l’avez sans doute déjà repéré : sur la plateforme OpenEdition Books, une nouvelle interface vient d’être mise en ligne. En cas d’anomalies au cours de votre navigation, vous pouvez nous les signaler par mail à l’adresse feedback[at]openedition[point]org.

Français FR

Ressources numériques en sciences humaines et sociales

Nos plateformes

Bibliothèques

Suivez-nous

Redirection vers OpenEdition Search.

- Presses universitaires François-Rabelai... ›

- Recent Trends in Narratological Researc... ›

- Reconceptualizing the Theory and Generi...

- Presses universitaires François-Rabelai...

Recent Trends in Narratological Research

Ce livre est recensé par

Reconceptualizing the Theory and Generic Scope of Unreliable Narration *

The paper argues that the concept "unreliable narrator" needs to be radically rethought because, as currently defined, it is terminologically imprecise and theoretically inadequate. The first part of the article is devoted to giving an assessment and critique of the standard notions of the unreliable narrator, arguing that the postulation of essentialized and anthropomorphized entities designated "unreliable narrator" and "implied author" ignore the complexity of the phenomena involved and stands in the way of a systematic exploration of the cognitive processes which result in the projection of unreliable narrators in the first place. The second part outlines a radical reconceptualization of unreliable narration. It is proposed that it would be more sensible to conceptualize the relevant phenomena in the context of frame theory as a projection by the reader who tries to resolve ambiguities and textual inconsistencies by attributing them to the narrator's "unreliability." In the context of frame theory, the reader's projection of "unreliable narrators" can be understood as an interpretive strategy or a cognitive process of the sort that has come to be known as "naturalization" (cf. Culler 1975; Fludernik 1993, 1996). A number of empirical frames of reference and literary models can be seen as standard modes of naturalization by means of which readers account for contradictions both within texts and between the world-model of texts and their empirical world-models. The final section gives a brief outline of the generic scope of unreliable narration, arguing that it is unjustifiable and counterproductive to limit the study of this phenomenon to narrative fiction

Plan détaillé

Texte intégral.

1 Ever since Wayne C. Booth first proposed the unreliable narrator as a concept, it has been considered to be among the basic and indispensable categories of textual analysis. Hardly anyone to date has modified or challenged Booth's well-known formulation, which has become the canonized definition of the term: "I have called a narrator reliable when he speaks for or acts in accordance with the norms of the work (which is to say the implied author's norms), unreliable when he does not" (1961, 158-59). According to Booth, the distinction between reliable and unreliable narrators is based on "the degree and kind of distance" (155) that separates a given narrator from the implied author of a work. A comparison of the definitions provided in standard narratological works, in scholarly articles, and in glossaries of literary terms shows that the great majority of narratologists have followed Booth, providing almost identical definitions of the unreliable narrator.

2 What most critics seem to have forgotten, however, is that Booth himself freely admitted that the terminology for "this kind of distance in narrators is almost hopelessly inadequate" (1961, 158). There is indeed a peculiar discrepancy between the importance generally attributed to the question of reliability in narrative and the unresolved issues surrounding the concept of the unreliable narrator: "There can be little doubt about the importance of the problem of reliability in narrative and in literature as a whole.... [But] the problem is (predictably) as complex and (unfortunately) as ill-defined as it is important" (Yacobi, 1981, 113). Booth's canonical definition does not really make for clarity but rather sets the fox to keep the geese, as it were, since it falls back on the ill-defined and elusive notion of the implied author, which hardly provides a reliable basis for determining a narrator's unreliability.

3 The thesis of this article is that the concept of the unreliable narrator needs to be radically rethought because, as currently defined, it is terminologically imprecise and theoretically inadequate. The postulation of essentialized and anthropomorphized entities designated "unreliable narrator" and "implied author" ignores the complexity of the phenomena involved and stands in the way of a systematic exploration of the cognitive processes which result in the projection of unreliable narrators in the first place. It would arguably be more adequate to conceptualize unreliable narration in the context of frame theory as a projection by the reader who tries to resolve ambiguities and textual inconsistencies by attributing them to the narrator's "unreliability". In the context of frame theory, the invention of "unreliable narrators" can be understood as an interpretative strategy or cognitive process of the sort that has come to be known as "naturalization." 1 Paraphrasing one of Malcolm Bradbury's observations in Mensonge, his hilarious satire on deconstruction, I would like to suggest that it is high time to dismantle many of the premises of realist theories of unreliable narration, and to convert the foundations of some others.

4 The first part of the article is devoted to giving an assessment and critique of the standard notions of the unreliable narrator. The second part outlines a radical reconceptualization of unreliable narration. It is argued that a number of empirical frames of reference and literary models serve as the modes of naturalization by means of which readers (like critics and most theorists of unreliable narration) account for contradictions both within texts and between the world-model of texts and their empirical world-models. The third part gives a brief outline of the generic scope of unreliable narration, arguing that it is unjustifiable and counter-productive to limit the study of this phenomenon to narrative fiction. The final section will then provide a brief summary and suggest that much more work needs to be done in this particular field of narratology.

I. A critique of conventional theories of unreliable narration

5 A brief look at conventional accounts of the concept "unreliable narrator" may be in order so as to distinguish the approach argued for in this essay from the general approach in narratology. Let us begin by asking just what it is that we know about the mysterious unreliable narrator and by presenting a critique of traditional theories of unreliable narration against the background of five hypotheses.

6 The definition provided by Gerald Prince in his Dictionary of Narratology will suffice to indicate what is usually meant by the term "unreliable narrator": "A narrator whose norms and behavior are not in accordance with the implied author's norms; a narrator whose values (tastes, judgments, moral sense) diverge from those of the implied author's; a narrator the reliability of whose account is undermined by various features of that account" (Prince, 1987, 101). Despite the good job Prince does in summarizing the communis opinio on the subject, this definition of the concept comprises an unholy mixture of vagueness and tautology. Nonetheless, most theorists and critics who have written on the unreliable narrator take the implied author both for granted and for the only standard according to which unreliability can be determined.

7 One of the central problems in defining unreliable narration is the unresolved question of what standards allow the critic to recognize an unreliable narrator. The usual answer to the question "Unreliable, compared to what?" is woefully inadequate and untenable, because it specifies just one basis for recognizing the narrrator's unreliability, namely the ill-defined concept of the implied author. The trouble with all of the definitions that are based on the implied author is that they try to define unreliability by relating it to a concept that is itself ill-defined and paradoxical. Curiously enough, however, even the most sophisticated recent articles retain the notion of the implied author. In what are arguably the best critiques of orthodox theories of unreliable narration to date, the articles of Tamar Yacobi (1981, 1987) and Kathleen Wall (1994), the authors hold on to the implied author as though he, or rather it, was the only possible way of accounting for unreliable narration.

8 Critics who argue that a narrator's unreliability is to be gauged in comparison to the norms of the implied author just shift the burden of determination onto a critical catch-all term that is itself notoriously ill-defined. The tenacity with which narratologists have clung to the implied author in their attempts at defining unreliability suggests, as Mieke Bal (1981b, 209) observes, that the implied author is "a remainder category, a kind of passepartout that serves to clear away all the problematic remainders of a theory." Introducing the implied author has certainly not managed to clear away the problems of defining unreliable narration.

9 Some narratologists have pointed out that the concept of the implied author does not provide a reliable basis for determining a narrator's unreliability. Not only are "the values (or 'norms') of the implied author... notoriously difficult to arrive at," as Rimmon-Kenan (1983, 101) observes, but the implied author is itself a very elusive and opaque notion. One might go much further than Rimmon-Kenan and suggest that the implied author's norms are impossible to establish and that the concept of the implied author is dispensable.

10 From a theoretical point of view, the concept of the implied author is also problematic because it creates the illusion that it is a matter of a purely textual phenomenon. But it is obvious from many of the definitions that the implied author is a construct established by the reader on the basis of the whole structure of a text. When Chatman (1990, 77) writes that "we might better speak of the 'inferred' than of the 'implied' author," he implicitly concedes that one is dealing with something that has to be worked out by the reader. Being a structural phenomenon that is voiceless, the implied author must be seen "as a construct inferred and assembled by the reader from all the components of the text" (Rimmon-Kenan, 1983, 87). Toolan has made the sensible suggestion that one should look at the implied author not as a speaker but as a component of the reception process, as the reader's idea of the author: "The implied author is a real position in narrative processing, a receptor's construct, but it is not a real role in narrative transmission. It is a projection back from the decoding side, not a real projecting stage on the encoding side" (1988, 78).

11 The most controversial aspect of the concept of the implied author is that it carries far-reaching, though largely unacknowledged theoretical implications. First, the concept of the implied author reintroduces the notion of authorial intention, though through the backdoor. As Chatman (1990, 77) has pointed out, "the concept of implied authorship arose in the debate about the relevance of authorial intention to interpretation." Providing "a new link to the sphere of the actual author and authorial values" (York, 1987, 166; cf. Yacobi, 1987), the implied author turns out to be little more than a terminologically presentable way of making it possible to talk again about the author's intention: "The concept of 'the implied author', with its air of being an inference from the work and thus as it were, like plot, an objective feature of the work, enables Booth to talk about the author under the guise of still appearing to talk about the work" (Baker, 1972/73, 204f.; cf. also Juhl, 1980, 203). Second, representing the work's norms and values, the implied author is intended to serve both as a yardstick for a moralistic kind of criticism and as a check on the potentially boundless relativism of interpretation. Third, the use of the definite article and the singular misleadingly suggest that there is only one correct interpretation: "The very fact that Booth and Chatman speak of the implied author already implies, suggests the existence of one ideal interpretation of the narrative text" (Berendsen, 1984, 148). In short, the concept of the implied author appears to provide the critic again with a basis for judging both the acceptability of an author's "moral position," about which, according to Booth, a writer "has an obligation to be as clear [...] as he possibly can be" (1961, 389), and the correctness of an interpretation.

12 The lack of terminological clarity and the problematic theoretical implications associated with the notion of the implied author have led some narratologists to argue that the concept should be abandoned. 2 Some theorists have recognized that it has not fulfilled the promise "to account for the ideology of the text" (Bal, 1981a, 42) and is not capable of doing what it was supposed to do: "It not only adds another narrating subject to the heap but it fails to resolve what it sets out to bridge: the author-narrator relationship" (Lanser, 1981, 49f.).

13 Whether or not narratolgy is really well served with such a problematic concept as the implied author, be it of the personalized and anthropomorphicized or the depersonified variety, is an open question. Recently, some prominent narratologists have again emphatically come out in favour of the implied author, while others have argued just as strongly against the concept. 3 But given the fact that phenomena like norms and values, structure, and meaning are central problems in literary criticism and will continue to occupy the attention of theorists and critics alike, they probably should not be allowed to disappear behind a concept like the implied author, which is ill-defined and potentially misleading. As I hope to show below, the implied author is neither a necessary nor a sufficient standard by which to determine a narrator's putative unreliability.

14 Despite what common sense would appear to tell us, definition is a problem with the unreliable narrator because most theories leave unclear what unreliability is and whether it involves moral or epistemological shortcomings. Most definitions in the wake of Booth have emphasized that unreliability consists of a moral distance between the norms of the implied or real author and those articulated by the narrator while other theorists have pointed out that what is at stake is not a question of moral norms but of the veracity of the account a narrator gives (cf. Toolan, 1988, 88).

15 In most work on the unreliable narrator, it is also unclear whether unreliability is primarily meant to designate a matter of misrepresenting the events of the story or whether it consists of the narrator's dubious judgments or interpretations. Rimmon-Kenan's (1983, 100) definition is a case in point. She simply leaves open whether unreliability is to be gauged in comparison to the accuracy of the narrator's account of the story or to his or her commentary and judgments: "An unreliable narrator... is one whose rendering of the story and/or commentary on it the reader has reasons to suspect." The "and/or"-construction sounds very open and flexible, but this is a bit too nonchalant. Most would agree that it does make a difference whether we have an deviant narrator who provides a sober and factually veracious account of the most egregious or horrible events, which, from his point of view, are hardly noteworthy, or a normal narrator who is just a bit slow on the uptake and whose flawed interpretations of what is going on revéal that he is a benighted fool. 4 Lanser (1981, 170ff.) provides an answer to the question of how we may classify narrators "with respect to 'reliability'" by positing three axes between the poles "dissimulation vs. honesty", "unreliability vs. reliability" and "narrative incompetence vs. narrative skill."

16 Conventional theories of unreliable narration are methodologically unsatisfactory as well because they either leave unclear how the narrator's unreliability is apprehended in the reading process or they provide only highly metaphorical and vague explanations of it. The metaphors that Chatman uses in order to explain how the reader detects the narrator's unreliability are a case in point. He resorts to what is arguably one of the two most popular metaphors in this context — that of "reading between the lines." Chatman (1978, 233) argues that readers "conclude, by 'reading out,' between the lines, that the events and existente could not have been 'like that,' and so we hold the narrator suspect." Leaving aside for the moment that the repeated use of inverted commas in definitions is not particularly reassuring, I just wish to suggest that such observations fail to shed much light on how a narrator's unreliability is apprehended in the reading process.

17 The second metaphor that critics and theorists continually employ in order to account for unreliable narration is that something is going on "behind the narrator's back" (cf. Riggan, 1981, 13; Yacobi, 1981, 125). Chatman (1978, 233), for instance, suggests that the implied author establishes "a secret communication with the implied reader. Riggan (1981, 13) not only uses almost exactly the same phrase, but he also states quite unequivocally that "the presence of the implied author's hand is always discernible behind the narrator's back" (77). He does not, however, bother to enlighten the uninitiated as to how the hand of the omnipresent implied author behind the narrator's back may in fact be discerned. Such metaphors, though vivid, provide only very opaque explanations of unreliable narration. From a methodological and theoretical point of view, they amount to nothing more than a declaration of bankruptcy. With regard to the question of how readers know an unreliable narrator when they see one, these metaphors are unenlightening.

18 To explain the mechanisms that stand behind the impression that a narrator is unreliable, it is not necessary to postulate an implied author but simply to have recourse to the concept of structural or dramatic irony (cf. Booth 1961, 255). The structure of unreliable narration can be explained in terms of dramatic irony and discrepant awareness because it involves a contrast between a narrator's view of the fictional world and the contrary state of affairs which the reader can grasp. The reader interprets what the narrator says in two quite different contexts. On the one hand, the reader is exposed to what the narrator wants and means to say. On the other hand, the statements of the narrator take on additional meaning for the reader, meaning that the narrator is not conscious of and does not intend to convey. Without being aware of it, unreliable narrators continually give the reader indirect information about their idiosyncrasies and states of mind. The peculiar effects of unreliable narration result from the conflict between the narrator s report of the facts" on the level of the story and his own interpretations. The narrative not only informs the reader of the narrator s version of events, it also provides him or her with indirect information about what presumably "really happened" and about the narrator's frame of mind.

19 If one gives up the notion of the implied author, then it is necessary to modify Booth's (1961, 74) explanations of the unreliable narrator in such a way as is already suggested by his definition of the implied author as "the core of norms and choices." Unreliable narrators are those whose perspective is in contradiction with the value and norm system of the whole text or with that of the reader. The phenomenon of unreliable narration can be seen as the result of discrepant awareness and dramatic irony.

20 The general effect of what is called unreliable narration consists of redirecting the reader's attention from the level of the story to the speaker and of foregrounding peculiarities of the narrator's psychology. Wall (1994, 23) argues very convincingly that unreliable narration "refocuses the reader's attention on the narrator's mental processes." What is needed therefore is a more systematic exploration of the relation between unreliability and characterization. In the only available article on the subject, Dan Shen (1989, 309) has shown that "deviations in terms of reliability may have a significant role to play in revealing or reinforcing narratorial stance" and "in characterizing a particular consciousness." In unreliable narration it is often very difficult to determine whether what the narrator says provides facts about the fictional world or only clues to his distorted and evaluating consciousness. Consequently, the answer to the question "reliable, compared to what?" may vary dramatically depending on whether the standard according to which we gauge the potential unreliability of the narrator involves the events or the narrator's subjective view of them.

21 In sum, the link that theorists have forged between the unreliable narrator and the implied author deprives narratology of the possibility of accounting for the pragmatic effects subsumed under the term of unreliable narration. The critic accounts for whatever incongruousness s/he may have detected by reading the text as an instance of dramatic irony and by projecting an unreliable narrator as an integrative hermeneutic device. Culler (1975, 157) has clarified what is involved here: "At the moment when we propose that a text means something other than what it appears to say we introduce, as hermeneutic devices which are supposed to lead us to the truth of the text, models which are based on our expectations about the text and the world." This, of course, raises the questions of what kind of models are involved in the cognitive processes that lead to the projection of an unreliable narrator.

II. Reconceptualizing conventional theories of unreliable narration

22 Heeding Harker's (1989) call for a radical reorientation, I will try to outline a model-oriented approach to how texts that display features of unreliable narration are read. 5 I will contend that we can define unreliable narration neither as a structural nor as a semantic aspect of the textbase alone, but only by taking into account the conceptual frameworks that readers bring to the text. If we are to make sense of unreliable narration at all, it would be wise to begin by looking at the standards according to which critics think they recognize an unreliable narrator when they see one.

23 Determining whether a narrator is unreliable is not just an innocent descriptive statement but a subjectively tinged value-judgment or projection governed by the normative presuppositions and moral convictions of the critic, which as a rule remain unacknowledged. Critics concerned with unreliable narrators recuperate textual inconsistencies by relating them to accepted cultural models. Recent work on unreliable narration confirms Culler's hypothesis about the impact of realist and referential notions for the generation of literary effects. Culler (1975, 144) argues that "most literary effects, particularly in narrative prose, depend on the fact that readers will try to relate what the text tells them to a level of ordinary human concerns, to the actions and reactions of characters constructed in accordance with models of integrity and coherence."

24 Riggan's monograph on the unreliable first-person narrator provides a case in point. Despite its insights into a broad range of texts, it suffers from all of the theoretical shortcomings outlined above. A look at Riggan's typology of unreliable narrators provides insight into the basic mechanisms that are involved in the projection of an unreliable narrator. Riggan distinguishes four types of such narrators, which he designates as "picaros," "madmen," "naïfs," and "clowns."

25 These typological distinctions can best be understood as a way of relating the text to accepted cultural models or to literary conventions. What critics like Riggan are doing is integrating previously held world-knowledge with textual data or even imposing preexisting conceptual models on the text. The models used to account for unreliable narration provide a context which resolves textual inconsistencies and makes the respective novels intelligible in terms of culturally prevalent frames.

26 It is these models which determine the perception of narrators designated as "unreliable," and not the other way round. The information on which the projection of an unreliable narrator is based derives at least as much from within the mind of the beholder as from textual data. In other words: whether a narrator is called unreliable or not does not depend on the distance between the norms and values of the narrator and those of the implied author, but between the distance that separates the narrator's view of the world from the reader's or critic's world-model and standards of normalcy, which are themselves, of course, open to challenge. It is thus necessary to make explicit that customary presuppositional framework on which theories of unreliable narration have hitherto been based.

27 An analysis of the presuppositional framework on which most theories of unreliable narration rest is overdue, since research into unreliable narration has been based on a number of highly questionable conceptual presuppositions, which as a rule remain implicit and unacknowledged. The general notion of unreliability presupposes some sort of standard for establishing whether or not the facts or interpretations provided by a narrator may be held suspect. The violations of norms which interest critics and theorists "are only made possible by norms which," as Culler (1975, 160) wittily observes, "they have been too impatient to investigate in detail." These presuppositions about unreliable narration need to be made explicit and clarified because they provide the key for reconceptualizing unreliability.

28 Among these underlying (and unwarranted) presuppositions on which the concept of unreliable narration relies, one might distinguish between epistemological and ontological premises, assumptions that are rooted in a liberal humanist view of literature, and psychological, moral, and linguistic norms — all of which are based on stylistic and other deviational models. An analysis of the presuppositional framework on which most theories of unreliable narration are based reveals that the orthodox concept of the unreliable narrator is a curious amalgam of a realist epistemology and a mimetic view of literature.

29 The epistemological and ontological premises consist of realist and by now doubtful notions of objectivity and truth. More specifically, the notion of unreliability presupposes that an objective view of the world, of others, and of oneself can be attained. In contrast to the ideal of objective self-obervation, it needs to be emphasized that "a maximally objective view of oneself can be attained only by others" (Fludernik, 1993, 53). The concept of unreliable narration also implies that human beings are principally taken to be capable of providing veracious accounts of events, proceeding from the assumption that "an authoritative version of events" (Wall, 1994, 37) can in principle be established or retrieved.

30 Theories of narrational unreliability also tend to rely on realist and mimetic notions of literature. The concept of the unreliable narrator is based on what Yacobi (1981, 119) has aptly called "a quasi-human model of a narrator" and, one might add, on an equally anthropomorphized model of the implied author. Amoros (1991, 42) has provided a convincing critique of this general tendency of allocating human features to the narrative agent.

31 In addition, theories of narrational unreliability are also heavily imbued with a wide range of unacknowledged notions that are based on stylistic deviation models or on more general notions of deviation from some norm or other. The notion of unreliability presupposes some default value which is taken to be unmarked "reliability." This is usually left undefined and merely taken for granted. Most critics agree, however, that reliability is indeed the default value (cf. Martinez-Bonati, 1981). Lanser (1981, 171), for instance, argues that "the conventional degrees zero [are] rather close to the poles of authority," and Riggan (1981, 19) observes that "our natural tendency is to grant our speaker the full credibility possible within the limitations of human memory and capability." To my knowledge, Wall is the first theorist of unreliable narration who sheds some light on the presuppositions on which this "reliable counterpart" of the unreliable narrator rests when she argues that the reliable narrator "is the 'rational, self-present subject of humanism,' who occupies a world in which language is a transparent medium that is capable of reflecting a 'real' world."

32 Vague and ill-defined though this norm of reliability may be, it supplies the standard according to which narrational unreliability is gauged. If one takes a close look at the presuppositional framework on which theories of unreliable narration are based, one can further elucidate the assumption that an unreliable narrator departs from certain norms. What is involved here are various sets of ill-defined and usually unacknowledged norms, which can, however, theoretically be distinguished.

33 One of these sets of norms includes all those notions that are usually referred to as "common sense." Another set encompasses those standards that a given culture holds to be constitutive of normal psychological behaviour. Thirdly, the habit of discussing the stylistic peculiarities of unreliable narrators shows that linguistic norms also play a role in determining how far a given narrator deviates from some implied default. Finally, many critics seem to think that there are agreed-upon moral and ethical standards that are often used as frames of reference when the question of the possible unreliability of a narrator is raised.

34 One of the main problems with all of these tacit presuppositions based on unacknowledged norms and notions of deviation is that the establishment of norms is much more difficult than critics want to make us believe. Fludernik (1993, 349), for instance, argues that the "explicatory power of stylistic deviation breaks down at the point where one can no longer establish a norm, or where deviations from the norm are no longer empirically perceptible."

35 In both critical practice and theoretical work on unreliable narration, however, these different sets of norms are usually not explicitly set out but merely introduced in passing, and they seldom if ever receive any theoretical examination. Let me give one typical example: in what is the only book-length study of the unreliable first-person narrator, Riggan (1981, 36), for instance, suggests that the narrator's unreliability may be revealed by the "unacceptability of his [moral] philosophy in terms of normal moral standards or of basic common sense and human decency." By saying this, he lets the cat out of the bag in a way that is very illuminating indeed.

36 Phrases like these unwittingly reveal the real standards according to which critics decide whether a narrator may be unreliable: It is not the norms and values of the implied author, whoever or wherever that phantom may be, that provide the critic with the yardstick for determining how abnormal, indecent, immoral or perverse a given narrator is, but "normal moral standards," "basic common sense" and "human decency" — in other words: unreliable, not in comparison to the implied author, but unreliable in comparison to what the critic takes to be "normal moral standards" and "common sense."

37 The trouble with seemingly self-explanatory yardsticks like "normal moral standards" and "basic common sense" is that no generally accepted standard of normality exists which can serve as the basis for impartial judgments. In a pluralist, postmodernist, and multicultural age like ours it has become more difficult than ever before to determine what may count as "normal moral standards" and "human decency." In other words: a narrator may be perfectly reliable compared to one critic's notions of moral normality but quite unreliable in comparison to those held other people. To put it quite bluntly: a pederast would not find anything wrong with Lolita; a male chauvinist fetishist who gets his kicks out of making love to dummies is unlikely to detect any distance between his norms and those of the mad monologuist in Ian McEwan's "Dead As They Come"; and someone used to watching his beloved mother disposing of unwelcome babies would not even find the stories collected in Ambrose Bierce's "The Parenticide Club" in any way objectionable.

38 There are a number of definable textual clues to unreliability, and what is needed is a more subtle and systematic account of these signals. 6 Unreliable narrators tend to be marked by a number of textual inconsistencies. These may range from internal contradictions within their discourse over discrepancies between their utterances and actions (cf. Riggan, 1981, 36, who calls this "a gaping discrepancy between his conduct and the moral views he propounds"), to those inconsistencies that result from multiperspectival accounts of the same event (cf. Rimmon-Kenan, 1983, 101; Toolan, 1988, 88).

39 The range of clues to unreliability that Wall (1994, 19) simply refers to as "verbal tics" or "verbal habits of the narrator" (20) can and should be further differentiated by specifying the linguistic expressions of subjectivity. Due to the close link between subjectivity, on the one hand, and the effect called unreliability, on the other, the virtually exhaustive account of categories of expressivity and subjectivity that Fludernik (1993, 227-279) has provided are also extremely useful for drawing up a list of grammatical signals of unreliability, which can be further differentiated in terms of the linguistic expressions of subjectivity. The "establishment" of a reading in terms of "unreliable narration" frequently depends on the linguistic and stylistic evocation of a narrator's subjectivity or cognitive limitations (cf. Fludernik, 1993, 280).

40 Despite the above list of textual clues to unreliability, it needs to be emphasized that the problem of unreliable narration cannot be resolved on the basis of textual data alone. In addition to these intratextual signals, the reader also draws on extratextual frames of reference in his or her attempt to gauge the narrator's potential degree of unreliability. The term "unreliable narrator" does not designate a structural or semantic feature of texts, but a pragmatic phenomenon that cannot be fully grasped without taking into account the conceptual premises that readers and critics bring to texts. Consequently, it seems doubtful whether the term unreliable narrator can be defined, as Zimmermann (1995, 61) has recently maintained, solely on the basis of what she calls "intratextual dissonances."

41 What is needed instead is a pragmatic and cognitive framework that takes into consideration the world-model or conceptual information previously existing in the mind of reader or critic. It is necessary to take into consideration both the world-model and norms in the mind of the reader and the interplay between textual and extratextual information. Coming to grips with narrational unreliability is impossible if one conceives reading as being a mere "'bottom-up' or data-driven process" just as if one conceives it as being nothing but "a 'top-down' or conceptually driven process" (Harker, 1989, 471).

42 Developing a viable theory of unreliable narration that accounts for the complex meaning effects subsumed under the concept of unreliable narration presupposes an "interactive model of the reading process" (Harker, 1989, 471) and a reader-oriented pragmatic or cognitive framework (cf. Fludernik, 1993, 51). It is only within an interactive model of the reading process that an adequate theory of unreliable narration can be elaborated. Fludernik's (1993, 353) explanation of irony illuminates how this might be conceptualized: "textual contradictions and inconsistencies alongside semantic infelicities, or discrepancies between utterances and action (in the case of hypocrisy), merely signal the interpretational incompatability... which then requires a recuperatory move on the reader's part — aligning the discrepancy with an intended higher-level significance: irony."

43 An interactive model of the reading process alerts theorists of unreliable narration that the projection of an unreliable narrator depends upon both textual information and extratextual conceptual information located in the reader's mind (cf. Harker, 1989, 476). Detaching the text from the reader and ignoring the world-models in the reader's mind has resulted in the aporias outlined above. On the other hand, one should beware of throwing the baby out with the bathwater by rejecting textual data as a legitimate basis for explaining unreliable narration.

44 Pragmatics and frame theory present a possible way out of the methodological and theoretical problems that most theories of unreliable narration suffer from because cognitive theories can shed light on the way in which readers naturalize texts that are taken to display features of narrational unreliability. To offer a reading of a narrative text in terms of unreliable narration can be thought of as a way of naturalizing textual inconsistencies by giving them a function in some larger pattern supplied by accepted cultural models. Culler (1975, 138) clarifies what "naturalization" means in this context: "to naturalize a text is to bring it into relation with a type of discourse or model which is already, in some sense, natural or legible." The concept of unreliable narration, for instance, provides the reader with a general framework which allows him or her to "treat anything anomalous as the effect of the narrator's vision or cast of mind" (Culler, 1975, 200). To my knowledge, Wall (1994, 30) is the only theorist to date who has at least briefly discussed the relation between naturalization and unreliable narration: "Part of the way in which we arrive at suspicions that the narrator is unreliable, then, is through the process of naturalizing the text, using what we know about human psychology and history to evaluate the probable accuracy of, or motives for, a narrator's assertions." She is certainly also right when she suggests that this kind of naturalization "is so much a part of our reading strategy with respect to both characters and narrators that, in all probability, we do not notice it."

45 Noticing and clarifying those unacknowledged frames of reference provides the clue to reconceptualizing the whole notion of unreliable narration. The question of whether a narrator is described as unreliable or not needs to be gauged in relation to various frames of reference. More particularly, one might distinguish between schemata derived from everyday experience and those that result from knowledge of literary conventions. 7

46 A first referential framework should be based on the readers 'empirical experience and criteria of verisimilitude. These frames depend on the referentiality of the text, the assumption that the text refers to or is at least compatible with the so-called real world. Whether a narrator is taken to be reliable or not depends, among other things, on such referential frameworks as the reader's or critic's

- general world-knowledge,

- historical world-model or cultural codes, 8

- explicit theories of personality or implicit models of psychological coherence and human behaviour, 9

- knowledge of the social, moral or linguistic norms relevant for the period in which a text was written and published (cf. Yacobi, 1987),

- the reader's or critic's psychological disposition, and system of norms and values.

47 Whether a narrator is taken to be reliable or not depends, among other things, on such referential frameworks as the reader's general world-knowledge. Deviations from what is usually referred to as "common sense" or general world-knowledge may indicate that the narrator is unreliable. Secondly, narrators who violate the standards that a given culture holds to be constitutive of normal psychological behaviour are generally taken to be unreliable. What is involved here is psychological theories of personality or implicit models of normal human behaviour. In order to gauge the potential unreliablity of the fictitious child-molester Humbert Humbert, the narrator of Nabokov's Lolita (1955), it does not suffice to look at textual data alone, because the process of character constitution during the reading process is inevitably influenced by the reader's implied personality theory, as Grabes (1996) has convincingly demonstrated. Thirdly, generally agreed-upon moral and ethical standards are often used as frames of reference when the question of the possible unreliability of a narrator is raised.