Discrimination and gender inequalities in Africa: what about equality between women and men?

Written by Louise Jousse

Translated by Charline Vandermuntert

On the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the creation of the Pan African Women Association (PAWA) on November 15, 2012, Irina Bokova, UNESCO Director-General from 2009 to 2017, declared: “Women are the driving force behind small changes of critical importance to their societies and communities: they are advancing the quality of education and access to health care; they are fighting for their rights and active participation [in political life]; and they are promoting peace, reconciliation and development [1] “.

Women are essential to a country’s development and functioning, yet they still face a great deal of discrimination and violence because of their gender. What of the situation on the African continent? Women are those who suffer the most from gender inequality and marginalization on the continent. What are the solutions to gender inequality and discrimination against women and girls? What actions are possible? Africa has made significant progress towards gender equality and women’s empowerment, yet inequalities reached a critical level in West Africa. It is, therefore, interesting to take stock of discrimination on the African continent (I), and then look at the different actions that can be taken to remedy gender inequalities (II).

A region strongly characterized by gender inequalities and discrimination

Equality of fundamental rights between women and men is not yet a reality, regardless of the region. Various African countries are no exception and are still largely affected by gender inequalities in the social, economic and political spheres.

- Social inequalities

Women experience different forms of violence because of their gender, especially in the social sphere. They are often subjected to domination by their spouses, as mentioned in Article 444 of the Congo Family Code: “The husband is the head of the household. He owes protection to his wife; his wife owes obedience to her husband [2] “. This makes marriage one of the most discriminatory practices against women. To mitigate this, Article 16 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) [3] requires States to set a minimum age for marriage. Nevertheless, Natacha Ordioni, a senior lecturer in sociology, reveals that in some twenty African countries, the civil code does not fulfill this obligation.

In West Africa, 44% of women aged 20 to 24 were married before the age of 15 [4] . According to UNICEF, approximately two out of three married girls were married to a partner at least ten years older in Gambia, Guinea, and Senegal [5] . The majority of underage marriages globally occur in West Africa. Niger and Mali are the most affected, with a prevalence of 77% and 61% respectively [6] . This difference can be explained by the importance of social norms and traditions, which influence the choice to marry one’s daughter. Having a child out of wedlock is perceived as a pure shame and the earlier a girl is married, the lower the risk of pregnancy outside marriage. These child marriages then create inequalities in schooling: out of 916 women married at an early age in Mali, 366 had to leave school and 294 others never went to school [7] . Whether at the primary or secondary level, girls have less access to education, with a 4-point difference in 2017 for secondary education compared to boys. This lack of access to education for girls has consequences for the country’s development. The 2018 World Bank report shows that there is a persistent literacy gap between young girls and boys in Africa: 72% of girls aged 15 to 24 are literate compared to 79% for boys, a difference of 7 points [8] . Inequalities are then flagrant in the provision of public services, such as education. For instance, it is estimated that 70% of the poorest girls in Niger have never attended elementary school. Niger has the lowest level of education in the world, with an average schooling duration of only 18 months [9] . These inequalities result in a relatively high loss of potential human development. Access to quality and inclusive education for girls becomes imperative to allow them to evolve in the economic and political spheres.

- Economic inequalities

Economically, women also face discrimination and are still far from empowerment. There are many obstacles to their participation in economic activities, mainly due to the disparities between women and men, both in terms of access to economic resources and in the various sectors of activity. Although they represent 70% of the active population in the agricultural sector [10] , women remain at the bottom of the ladder in this area and work in difficult conditions, with low incomes. The wage gap between women and men is about 30%: for every dollar earned by a man, a woman earns only seventy cents [11] . This difference can be explained by parameters such as age, type of job or level of education. The fact that women are not more integrated into the national economy represents a high economic cost for the countries concerned. According to the 2016 UNDP report, the total annual economic losses caused by gender gaps in sub-Saharan Africa reached US$95 billion between 2010 and 2014, peaking at US$105 billion in 2014 [12] . These results then demonstrate that Africa is missing out on its full growth potential because a considerable portion of its growth pool, namely women, is not being fully harnessed for state development. In addition, African women are more likely than men to be in vulnerable employment and work primarily in the informal sector. In 2010, 65.4% of non-agricultural jobs in the informal sector were held by women in Liberia and 62.2% in Uganda [13] . Women working in the informal sector de facto lack social protection, reinforcing their precariousness.

- Political inequalities

When it comes to political equality, the situation is more nuanced. In 2018, only 24% of seats in national parliaments were held by women [14] . However, this figure is slightly increasing, since it was 12% in 2000 and 19% in 2010 [15] . Women are largely underrepresented in ministries and other legislative and executive bodies. Nevertheless, despite this low percentage, some countries stand out, such as Rwanda: the first country in which women make up more than half of parliamentarians, representing 61.3% of parliamentarians in 2018 [16] . With these figures, Rwanda exceeds the expectations of the 1995 Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, since the Beijing World Conference on Women set a target of 30% of women in decision-making positions. Similarly, Ethiopia has seen the largest increase in women’s political representation in the executive branch, with 47.6% of women in mid-level positions in 2019, up from 10% in 2017 [17]< /sup> . Mozambique was also the first country in the region to appoint a woman as prime minister, Luisa Diogo in 2004. African women are slowly taking ownership of the political sphere and are gaining greater visibility, allowing them to push the political agenda in their countries. Cecilia Poggi, a French economist, and Juliette Waltmann, a researcher for the French Development Agency (AFD), explain that it is essential to consider women as full-fledged political actors and that they must be able to have the same representation and participation as men, and hence become female role models to inspire other young girls [18] . However, progress is measured in micro-advances and several African countries have less than 10% of women in mid-level positions, such as Morocco (5.6%), Nigeria (8%) or Sudan (9%) [19] , which is still far from the objective of 30% desired by the Beijing Platform for Action of 1995.

Fighting against social, economic and political inequalities demands a change of mentality. For this to happen, society as a whole must become aware of the importance of valuing the status of women and therefore question its practices, both for men and for women who have internalized and accepted the norms to which they are subjected. This reconsideration can have different faces.

National and regional political actions

Equality between women and men and the empowerment of women and girls has become a priority on the African continent, aiming to ensure respect for women’s rights and put an end to gender discrimination. Women’s empowerment and sustainable development were highlighted at the 2015 African Union Summit of Heads of State and Government in the context of achieving Africa’s Agenda 2063. Agenda 2063 is built on seven commitments, namely:

- Achieving equitable people-centred growth and development

- Eradicating poverty

- Developing human capital, social goods, infrastructure and public goods

- Achieving sustainable peace and security

- Establishing effective and strong State development

- Promoting participatory and accountable institutions

- Empowering women and girls

The empowerment of women and girls and gender equality is becoming a very important objective for the member states of the African Union. As a result, girl-specific policies have led to significant improvements in access to education for girls in Benin, Botswana, Gambia, Guinea, Lesotho, Mauritania, and Namibia. Girls’ access to education has also increased thanks to awareness campaigns, but also thanks to policies to reduce school fees in public elementary schools in rural areas. In Benin, for example, the gender gap has decreased from 32% to 22% [20] .

African feminist movements: a way to fight against gender inequalities

Feminist movements have also emerged so that women can claim their rights. They also intend to denounce inequalities and discriminations linked to their gender that African women have gathered in groups. Fatou Sow, a Senegalese sociologist and researcher working mainly on gender issues in Africa, explains that the women’s movements known today are recent and refer to the colonial period [21] . However, the origin of these movements goes back well before this period. Associations have formed women’s networks of neighbourhood, solidarity and strengthening of social ties. These organizations “are the place for women to weave social links beyond the economic aspect [22] “. Lucia Bakulumpagi, the founder of the Bakulu Power company in Uganda, explains that women must get together (“it is urgent for women to network” [23] ) because they face problems that men do not, such as motherhood. This network allows them to reconcile both their private and professional lives, putting forward the concept of sisterhood.

In addition, the importance of feminist demonstrations and movements should not be overlooked. For several years, marches have been held in Pretoria, South Africa, to denounce sexual and gender-based violence. In South Africa, in 2019, the police register about 110 complaints of rape [24] daily, a figure that although significant, does not consider the unreported crimes, only showing the tip of the iceberg. We can therefore inflate this figure by imagining the unreported crimes. Demonstrations allow us to strengthen the voices of the victims, highlight problematic behaviours and thus seek an improvement in living conditions. With this in mind, the South African president, Cyril Ramaphosa, put in place an emergency plan in 2019 to combat violence against women in the country.

The involvement of international organizations in the fight against gender discrimination

The promotion of equality and human rights, as well as the elimination of discrimination and violence against women, are an integral part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations programs of recent decades [25] . As a result, many reports have emerged, such as the 2016 African Human Development Report [26] ,

which focuses on gender equality and examines the efforts of African countries to empower women, one of the main goals of the SDGs. To address these inequalities, the United Nations developed the concept of gender-responsive budgeting (GRB) in 1997, which involves a “gendered” analysis of budgetary allocations and a balancing of government funding.

In that respect, Robert B. Zoellick, President of the World Bank Group between 2007 and 2012, stated in 2011 that the World Bank had contributed $65 billion to promote girls’ education, women’s health and women’s access to credit, land, agricultural services, employment, and infrastructure. In line with this goal, in April 2019, the World Bank launched the Africa Human Capital Plan, which aims to improve human capital outcomes in the region, including $2.2 billion invested in women’s empowerment. The goal is to improve women’s access to education, access to quality health care and increase employment opportunities. To date, this action plan has provided vocational training to almost 100,000 women, and trained 6,600 midwives, according to the World Bank’s 2020 annual report [27] . Through the Human Capital Plan for Africa, more than 100,000 girls have also gone to school. However, international aid, particularly in the framework of feminist international aid policies, must be put into perspective, especially when the notion of empowerment is at stake. These public policies often come from Western countries towards African countries and disregarding the gap between the Western ideals and the context of the countries receiving the aid, making the latter null and void [28] .

Africa is a continent still strongly marked by gender inequalities in all areas, which has a strong impact on women, whether from a social, economic, or political point of view. Despite this alarming fact, for several decades, changes have taken place to overcome gender discrimination against women and girls. Now, the autonomy of women and girls as well as gender equality, standing as the fifth goal of the United Nations Development Goals, have become priorities for many countries, incl uding in Africa. Progress in this area is due to the implementation of programs and policies as well as to feminist associations that have been deconstructing patriarchal ideas for several decades. However, the health situation related to the coronavirus pandemic is having a negative impact on women’s rights: it will take another 36 years to reach gender equality, a total of 136 years. Saadia Zahidi, a member of the Davos Forum’s executive committee, explains that the pandemic has a strong impact on gender equality, both in the public and private spheres, particularly with an increase in sexual violence within the home [29] . The current pandemic accentuates gender inequalities and becomes a threat to women’s rights in the world and Africa.

References:

[1] “UNESCO and gender equality in Sub-Saharan Africa: innovative programmes, visible results”, UNESCO Report , 2017

[2] Congo (Democratic Republic of) Family Code, Book 3, title 1, chap. 5, sect. 2, art. 444.

[3] Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discriminations Against Women, article 16.2 “The betrothal and the marriage of a child shall have no legal effect, and all necessary action, including legislation, shall be taken to specify a minimum age for marriage and to make the registration of marriages in an official registry compulsory”. Online: https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/text/econvention.htm#article16

[4] Ordioni, Natacha. « Pauvreté et inégalités de droits en Afrique : une perspective “genrée” », Mondes en développement , vol. no 129, no. 1, 2005, pp. 93-106.

[5] UNICEF, Adolescent girls in West and Central Africa: data brief : https://www.unicef.org/wca/media/3886/file/Les%20filles%20adolescentes%20en%20Afrique%20de%20l’Ouest%20et%20du%20Centre%20.pdf

[6] « Mariages d’enfants au Mali et au Niger : comment les comprendre ? » Le Monde , 29 novembre 2018 https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2018/11/29/mariages-d-enfants-au-mali-et-au-niger-comment-les-comprendre_5390415_3212.html

[8] Investing in opportunity , World Bank Annual Report, 2018

[9] Christian Hallum, Kwesi W. Obeng, The West Africa Inequality Crisis , OXFAM, July 2019, available at: https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/620837/bp-west-africa-inequality-crisis-090719-en.pdf

[10] Food and Agriculture Organisation, 2011

[11] United Nations Development Programme, Africa Human Development Report 2016. Accelerating Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in Africa, 2016

[13] Africa Human Development Report 2016 based on data extracted from Maternity and paternity at work: Law and practice across the world Report, WLO, Geneva, 2014

[14] United Nations Development Programme, Africa Human Development Report 2016. Accelerating Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in Africa, 2016, p.49

[16] « Women in national parliaments », update 1 February 2019. http://archive.ipu.org/wmn-e/classif.htm

[17] Zipporah Musau, “African Women in politics: Miles to go before parity is achieved”, United Nations, Africa Renewal, 8 April 2019. https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/april-2019-july-2019/african-women-politics-miles-go-parity-achieved

[18] Poggi, Cecilia, and Juliette Waltmann (dir.), « La (re)production des inégalités de genre dans le monde du travail: des discriminations légales à l’autonomisation », La (re)production des inégalités de genre dans le monde du travail: des discriminations légales à l’autonomisation, Agence française de développement, 2019, pp. 1-36.

[19] Zipporah Musau, “ African Women in politics: Miles to go before parity is achieved”, United Nations, Africa Renewal, 8 April 2019. https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/april-2019-july-2019/african-women-politics-miles-go-parity-achieved

[20] Gumisai Mutume, “African Women Battle for Equality” United Nations, Africa Renewal, 2005. https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/july-2005/african-women-battle-equality

[21] « Mouvements féministes en Afrique », Revue Tiers Monde , vol. 209, no. 1, 2012, pp. 145-160.

[22] Citation of Mbootay Adja Meissa de Saint-Louis in Guèye, Ndèye Sokhna Mouvements sociaux des femmes au Sénégal, UNESCO, 2013.

[23] Forson, Viviane, Le Point [en ligne] « Ouganda – Lucia Bakulumpagi : ‘Il est urgent que les femmes se mettent en réseau’ », 27 juin 2019. Available on: https://www.lepoint.fr/afrique/ouganda-lucia-bakulumpagi-il-est-urgent-que-les-femmes-se-mettent-en-reseau-27-06-2019-2321450_3826.php

[24] Rodier Simon, TV5 Monde [en ligne] « Afrique du Sud : Manifestations de femmes contre les violences », 3 janvier 2019. Available on: https://information.tv5monde.com/info/afrique-du-sud-manifestations-de-femmes-contre-les-violences-278117

[25] More information: Jeanne Prin, “Gender and Development: evolutions and debates around a concept now indicator of international development”, Gender Institute in Geopolitics, 29 June 2020

[26] United Nations Development Programme, Africa Human Development Report 2016. Accelerating Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in Africa . 2016

[27] “Supporting Countries in Unprecedented Times”, World Bank Annual Report 2020 .

[28] More information on feminist international aid policy: Romane Wohlschies, “La notion d’empowerment dans l’aide au développement, entre appropriation et instrumentalisation – cas d’illustration “La politique d’aide internationale féministe du Canada au Mali”, Institut de Genre en Géopolitique, February

[29] Aline Nanko Samaké, “COVID-19: A Threat to Women’s Rights Everywhere: How does the Pandemic Increase Gender Inequality?”, Gender in Geopolitics Institute, April 2020

To cite this article : Louise Jousse, “Discrimination and gender inequalities in Africa: what about equality between women and men?”, 05.31.2021, Gender in Geopolitics Institute

An Intersectional Analysis of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence in the Regional Conflict in the Great Lakes Region of Africa since 1994: The 1994 Genocide in Rwanda (1/2)

An intersectional analysis of sexual and gender-based violence in the regional conflict in the great lakes region of africa since 1994: the eastern democratic republic of congo (2/2), persecutions against trans individuals in peru: systemic violence fuelled by the state 1/3, the decriminalization of abortion in uruguay: partial acceptance in the light of an omnipresent and multidimensional anti-abortion threat, the global north/south limit: still a relevant sociopolitical border the case of women with disabilities migrating in europe, paris 2024 olympic games – the promotion of gender equality among athletes is far from depicting the reality in sports worldwide, old women in china: vulnerability, discrimination, and ignored needs, privacy overview.

The power of parity: Advancing women’s equality in Africa

Africa has so much promise. The continent is home to some of the world’s fastest growing economies and offers an exciting frontier for businesses looking for growth and new markets. And yet, persistent gender inequality is limiting its potential. Pockets of good news do exist, but they tend to be success stories for women at the top of the pyramid, but not for millions of ordinary African women. Because of the failure to embrace gender diversity, millions of women and Africa’s overall social and economic progress will not reach their full potential.

If Africa steps up its efforts now to close gender gaps, it can secure a substantial growth dividend in the process. Accelerating progress toward parity could boost African economies by the equivalent of 10 percent of their collective GDP by 2025, new research from the McKinsey Global Institute finds.

This report explores the “power of parity” for Africa, looking at the potential boost to economic growth that could come from accelerating progress toward gender equality. It builds on MGI’s global research on this topic since 2015 and further develops the thinking contained in McKinsey’s long-established research on women in leadership roles and, in particular, its report Women Matter Africa published in 2016.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Progress toward gender parity in africa has stalled—a missed growth opportunity, on gender equality in work, africa’s progress is similar to other regions, largely due to high women’s labor-market participation, africa lags behind other regions on progress toward gender equality in society, to achieve new impetus toward gender parity, all stakeholders need to act in five priority areas.

Although some African countries have made tremendous progress driving toward gender parity in some areas, gender inequality remains high across the continent. Women account for more than 50 percent of Africa’s combined population, but in 2018 generated only 33 percent of the continent’s collective GDP. This reinforces and fuels inequality and compromises Africa’s long-term economic health.

Overall, progress toward gender equality has stalled over the past four years. At the current rate of progress, it would take Africa more than 140 years to reach gender parity. On MGI’s Gender Parity Score or GPS—a measure of progress toward equality—Africa scores 0.58 in 2019, indicating high gender inequality across the 15 GPS indicators of gender equality in work and society.

At the current rate of progress, it would take Africa more than 140 years to reach gender parity.

The GPS weights each indicator equally and calculates an aggregate measure at the country level of how close women are to gender parity where a GPS of 1.00 indicates parity; a GPS of 0.95, as illustration, indicates that a country has 5 percent to go before attaining parity. For most indicators, low inequality is defined as being within 5 percent of parity, medium between 5 and 25 percent, high between 25 and 50 percent, and extremely high as greater than 50 percent from parity. Most indicators of gender inequality are measured as female-to-male ratios ranging from zero to 1. Data for 2015 are taken from end-2014 and data for 2019 are taken from end-2018.

Africa’s GPS for 2019 is the same as four years previously. Across Africa, the only indicators on which there has been progress—in aggregate—are legal protection and political representation. All other indicators have stayed the same or even regressed in some countries.

The journey toward parity differs substantially among African countries. South Africa has the highest GPS at 0.76, indicating medium gender inequality. Mauritania, Mali, and Niger have the lowest scores at 0.46, 0.46, and 0.45, respectively (extremely high inequality).

Although the overall picture is one of stagnation or even reversals in the journey toward parity, some countries have shown remarkable improvement on some indicators. For instance, Rwanda and South Africa have increased women’s representation in middle-management roles by 27 percent and 15 percent, respectively. Algeria has cut maternal mortality rates by around 9 percent. Egypt has tripled its score, and Guinea and Liberia doubled their scores on legal protection of women. These examples of rapid progress should inspire others to forge ahead with actions to advance gender equality.

Advancing women’s equality can deliver a significant growth dividend. In a realistic “best-in-region” scenario in which the progress of each country in Africa matches the country in the region that has shown most progress toward gender parity, the continent could add $316 billion or 10 percent to GDP in the period to 2025 (Exhibit 1).

Africa’s overall progress toward gender equality at work is similar to that of other regions (Exhibit 2). This is largely because women’s labor-market participation is high in Africa. The GPS for women’s labor-force participation is 0.76—denoting medium gender inequality—whereas the global average is 0.64 or high gender inequality. Africa’s female participation is roughly on a par with that of China, Eastern Europe and Central Asia, North America and Oceania, and Western Europe. However, most African women work in low-paid, often subsistence, jobs in the informal economy.

In the formal economy, Africa has made notable advances on getting more women into executive committees and board positions. Africa has the highest female representation at the board level of any region at 25 percent against a global average of 17 percent and marginally higher than average representation on executive committees at 22 percent. Nevertheless, Africa’s GPS on women in leadership positions—which includes top and middle-management positions—is still only 0.33, a little below the global average of 0.37.

Since 2015, progress on increasing women’s presence in middle-management roles has gone backward—on average across Africa by around 1 percent a year.

Since 2015, progress on increasing women’s presence in middle-management roles has gone backward—on average across Africa by around 1 percent a year. In North Africa, only 9 percent of women attain middle-management roles despite the fact that they account for 53 percent of the population completing tertiary education. Too few African women make it into high-quality professional and technical jobs.

We analyzed the “funnel” toward senior leadership in business (this does not include women working in the home and in the informal economy) at five stages: education, tertiary education, formal jobs, middle-management roles, and top leadership roles. The results indicate that even for the small proportion of women in formal employment in Africa, there is a significant drop of nearly 50 percent of the share of women in entry-level positions to those in top leadership roles.

Africa lags behind other regions on progress toward gender equality in society. MGI looks at three elements: essential services and enablers of economic opportunity, legal protection and political voice, and physical security and autonomy (Exhibit 3).

Africa has the highest average maternal mortality rate of any region at four times the global average. In Burundi, Liberia, and Nigeria, the maternal mortality rate is seven times that average. Women’s education, and financial and digital inclusion are also below the world average, and have declined over the past four years. On education, Africa as a whole has a female-to-male ratio of 0.76 on the level of women’s education, the lowest GPS of any region in the world. One bright spot has been some progress on women’s political representation, but even here inequality remains extremely high. Violence against women is a global scourge, but Africa’s record is worse than the worldwide average.

In 34 of 91 countries MGI studied in 2015, women faced high to extremely high gender inequality on financial inclusion.

One key to unlocking economic opportunities for women is ensuring that they have access to finance. However, in 34 of 91 countries MGI studied in 2015, women faced high to extremely high gender inequality on financial inclusion, and Africa was one of the regions facing the biggest challenges on this front. Additionally, over the last four years, their access has declined.

Another increasingly important gateway to economic opportunity is access to digital technologies. Africa’s progress toward parity on digital inclusion is not far below the global average (0.81 female-to-male digital inclusion ratio vs. 0.86 globally), but that progress has stagnated. The continent still has the second largest gender gap in mobile ownership at 15 percent and only one woman out of three has access to the mobile internet in Sub-Saharan Africa compared with one man in two.

Some African countries have made some progress on getting women into parliamentary and ministerial roles in politics, but even here gender inequality remains extremely high as it is around the world.

The picture is not a uniform one. For instance, countries in Southern Africa perform relatively well on women’s education while West and Central African countries underperform. Southern and East African countries have low incidence of child marriage, but child marriage remains prevalent in West and Central Africa.

Africa needs new impetus in its journey toward gender parity. Making progress on any single indicator of gender inequality is likely to require systematic action on a range of indicators by governments, companies, communities, and individual men and women.

Successful programs have a number of common elements. First, they address deep-rooted attitudes about and behavior toward women. Second, programs are designed to achieve sustained impact. Third, they work with women as partners to identify issues and engage the most appropriate stakeholders who can be male or female but need to be effective agents of change. Finally, successful programs incorporate monitoring and evaluation to track progress and provide information that can drive accountability and commitment to goals.

Interventions in five priority areas could be the core of an effective agenda for change (Exhibit 4).

1. Invest in human capital

Human capital plays a vital role in driving sustained economic growth and boosting productivity, and it is imperative that countries invest sufficient resources to improve the skills, experience, resilience, and knowledge of their citizens. If there were to be more investment in women, they could make a higher contribution to Africa’s GDP. There are many dimensions to the development of human capital. We focus on four dimensions that are necessary to ensure that human capital is effective: educating the girl child by funding and creating an enabling environment; raising women’s skills for the future world of work; equipping women by enhancing their financial, digital, and legal literacy; and deploying funds effectively to build accessible, appropriate, and affordable healthcare systems.

2. Create economic opportunities

Creating pathways for African women—the vast majority who work informally—into better-paid and more fulfilling jobs is a major priority.

Women need economic opportunities if countries are to realize the full potential of their human capital. Creating pathways for African women—the vast majority of whom work informally—into better-paid and more fulfilling jobs is a major priority. This outcome could be achieved by improving the quality of jobs in the informal sector or by enabling women to leave informal work and find improved working prospects in the formal sector. We focus on interventions in the formal sector; company’s leaders propelling change from the top with a clear strategy and targets; putting in place a positive, inclusive, and supportive environment; unlocking opportunities for women-owned businesses; and developing public and household infrastructure.

3. Leverage technology

Digital and internet technology is spreading throughout Africa and can be the lever that opens many doors to women, helping to overcome current challenges on a number of indicators of gender equality. Many applications of these technologies apply to both men and women, but the onus is on providers to ensure that they are designed with a gender lens so that women can take full advantage of them. Priorities include creating women-friendly products to drive digital inclusion; and spreading the use of digital to raise financial inclusion and empower female entrepreneurs.

Download The power of parity: Advancing women’s equality in Africa , the full report on which this article is based (PDF–1MB).

4. shape attitudes.

Arguably any drive toward gender parity in Africa starts with efforts to change entrenched and widespread attitudes about women’s role in society, an extremely difficult and complex challenge that will require all stakeholders to play a part that is sustained over the long term. Even if women are enabled to undertake paid work through, for instance, the provision of flexible working practices and governmental policies in favor of maternity and paternity leave, women will continue to undertake the largest share of unpaid care work in the home if societal views don’t shift. The same is true for violence against women—without a change of attitudes, it will remain a scourge in Africa and in countries around the world. Campaigns that raise awareness and advocacy are key components of efforts to shift societal attitudes. In all cases, these efforts need to be supported by effective monitoring and evaluation. Enlisting male champions is another priority.

5. Enforce laws, policies, and regulations

Africa needs to ensure that—across the continent—women’s rights are enshrined in law and enforced by authorities. Many African countries sign up to international or regional treaties, but do not implement them. Governments need to institute and enforce legal rights, and put in place enabling policies and regulations that drive progress toward gender equality.

Africa needs new impetus in its journey toward gender parity requiring systematic action by governments, companies, communities, and individual men and women.

Download The power of parity: Advancing women’s equality in Africa , the full report on which this article is based (PDF–1MB).

Lohini Moodley is a partner in McKinsey’s Addis Ababa office; Mayowa Kuyoro and Folakemi Akintayo are consultants in the Lagos office; Tania Holt is a partner in the London office; Acha Leke is a McKinsey senior partner in Johannesburg, chairman of McKinsey’s Africa region, and a member of the McKinsey Global Institute Council; and Anu Madgavkar is a partner of the McKinsey Global Institute, where Mekala Krishnan is a senior fellow.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

The future of women at work: Transitions in the age of automation

The power of parity: Advancing women’s equality in Asia Pacific

Realizing gender equality’s $12 trillion economic opportunity

- UN Women HQ

What does gender equality look like today?

Date: Wednesday, 6 October 2021

Progress towards gender equality is looking bleak. But it doesn’t need to.

A new global analysis of progress on gender equality and women’s rights shows women and girls remain disproportionately affected by the socioeconomic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, struggling with disproportionately high job and livelihood losses, education disruptions and increased burdens of unpaid care work. Women’s health services, poorly funded even before the pandemic, faced major disruptions, undermining women’s sexual and reproductive health. And despite women’s central role in responding to COVID-19, including as front-line health workers, they are still largely bypassed for leadership positions they deserve.

UN Women’s latest report, together with UN DESA, Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals: The Gender Snapshot 2021 presents the latest data on gender equality across all 17 Sustainable Development Goals. The report highlights the progress made since 2015 but also the continued alarm over the COVID-19 pandemic, its immediate effect on women’s well-being and the threat it poses to future generations.

We’re breaking down some of the findings from the report, and calling for the action needed to accelerate progress.

The pandemic is making matters worse

One and a half years since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, the toll on the poorest and most vulnerable people remains devastating and disproportionate. The combined impact of conflict, extreme weather events and COVID-19 has deprived women and girls of even basic needs such as food security. Without urgent action to stem rising poverty, hunger and inequality, especially in countries affected by conflict and other acute forms of crisis, millions will continue to suffer.

A global goal by global goal reality check:

Goal 1. Poverty

In 2021, extreme poverty is on the rise and progress towards its elimination has reversed. An estimated 435 million women and girls globally are living in extreme poverty.

And yet we can change this .

Over 150 million women and girls could emerge from poverty by 2030 if governments implement a comprehensive strategy to improve access to education and family planning, achieve equal wages and extend social transfers.

Goal 2. Zero hunger

The global gender gap in food security has risen dramatically during the pandemic, with more women and girls going hungry. Women’s food insecurity levels were 10 per cent higher than men’s in 2020, compared with 6 per cent higher in 2019.

This trend can be reversed , including by supporting women small-scale producers, who typically earn far less than men, through increased funding, training and land rights reforms.

Goal 3. Good health and well-being

Disruptions in essential health services due to COVID-19 are taking a tragic toll on women and girls. In the first year of the pandemic, there were an estimated 1.4 million additional unintended pregnancies in lower and middle-income countries.

We need to do better .

Response to the pandemic must include prioritizing sexual and reproductive health services, ensuring they continue to operate safely now and after the pandemic is long over. In addition, more support is needed to ensure life-saving personal protection equipment, tests, oxygen and especially vaccines are available in rich and poor countries alike as well as to vulnerable population within countries.

Goal 4. Quality education

A year and a half into the pandemic, schools remain partially or fully closed in 42 per cent of the world’s countries and territories. School closures spell lost opportunities for girls and an increased risk of violence, exploitation and early marriage .

Governments can do more to protect girls education .

Measures focused specifically on supporting girls returning to school are urgently needed, including measures focused on girls from marginalized communities who are most at risk.

Goal 5. Gender equality

The pandemic has tested and even reversed progress in expanding women’s rights and opportunities. Reports of violence against women and girls, a “shadow” pandemic to COVID-19, are increasing in many parts of the world. COVID-19 is also intensifying women’s workload at home, forcing many to leave the labour force altogether.

Building forward differently and better will hinge on placing women and girls at the centre of all aspects of response and recovery, including through gender-responsive laws, policies and budgeting.

Goal 6. Clean water and sanitation

In 2018, nearly 2.3 billion people lived in water-stressed countries. Without safe drinking water, adequate sanitation and menstrual hygiene facilities, women and girls find it harder to lead safe, productive and healthy lives.

Change is possible .

Involve those most impacted in water management processes, including women. Women’s voices are often missing in water management processes.

Goal 7. Affordable and clean energy

Increased demand for clean energy and low-carbon solutions is driving an unprecedented transformation of the energy sector. But women are being left out. Women hold only 32 per cent of renewable energy jobs.

We can do better .

Expose girls early on to STEM education, provide training and support to women entering the energy field, close the pay gap and increase women’s leadership in the energy sector.

Goal 8. Decent work and economic growth

The number of employed women declined by 54 million in 2020 and 45 million women left the labour market altogether. Women have suffered steeper job losses than men, along with increased unpaid care burdens at home.

We must do more to support women in the workforce .

Guarantee decent work for all, introduce labour laws/reforms, removing legal barriers for married women entering the workforce, support access to affordable/quality childcare.

Goal 9. Industry, innovation and infrastructure

The COVID-19 crisis has spurred striking achievements in medical research and innovation. Women’s contribution has been profound. But still only a little over a third of graduates in the science, technology, engineering and mathematics field are female.

We can take action today.

Quotas mandating that a proportion of research grants are awarded to women-led teams or teams that include women is one concrete way to support women researchers.

Goal 10. Reduced inequalities

Limited progress for women is being eroded by the pandemic. Women facing multiple forms of discrimination, including women and girls with disabilities, migrant women, women discriminated against because of their race/ethnicity are especially affected.

Commit to end racism and discrimination in all its forms, invest in inclusive, universal, gender responsive social protection systems that support all women.

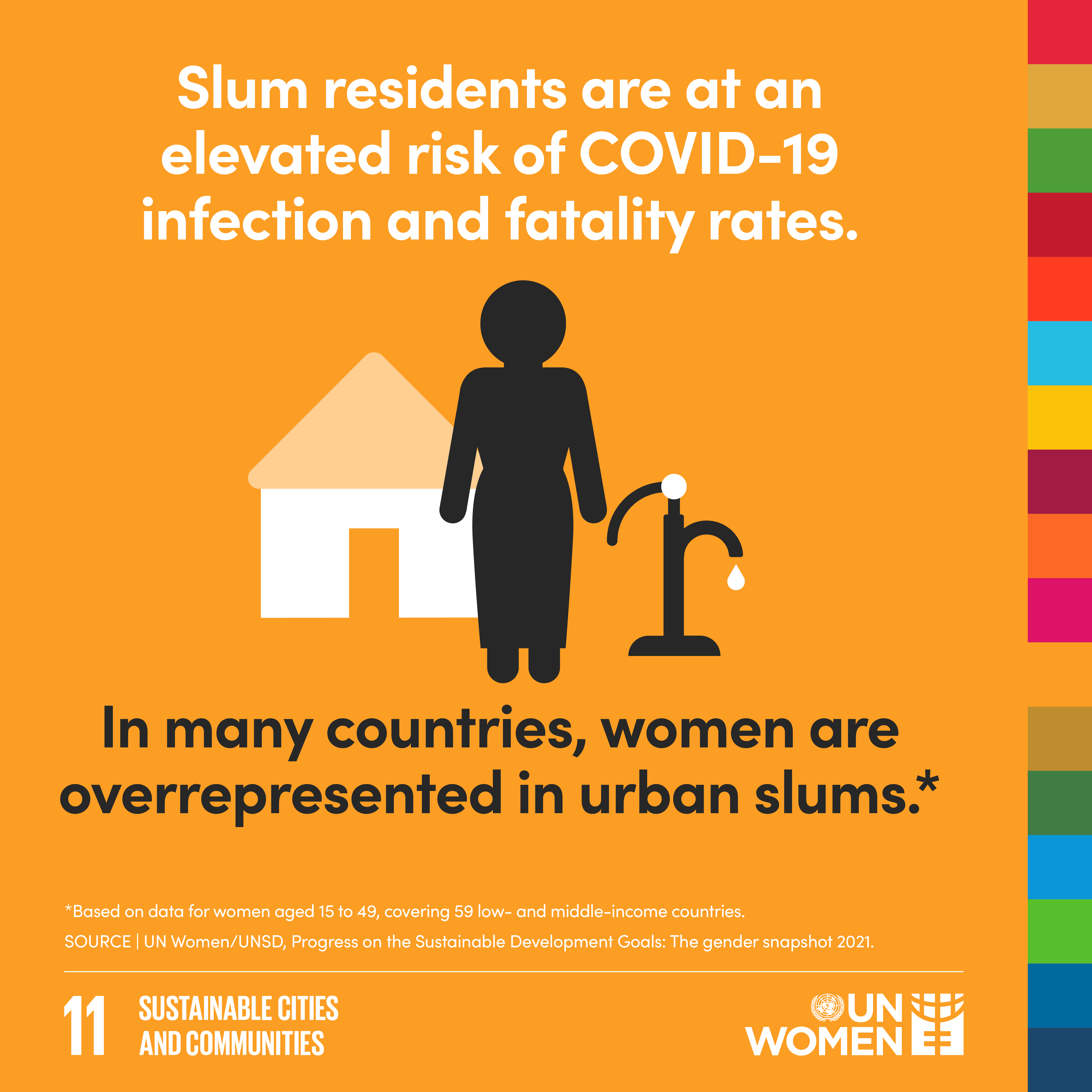

Goal 11. Sustainable cities and communities

Globally, more than 1 billion people live in informal settlements and slums. Women and girls, often overrepresented in these densely populated areas, suffer from lack of access to basic water and sanitation, health care and transportation.

The needs of urban poor women must be prioritized .

Increase the provision of durable and adequate housing and equitable access to land; included women in urban planning and development processes.

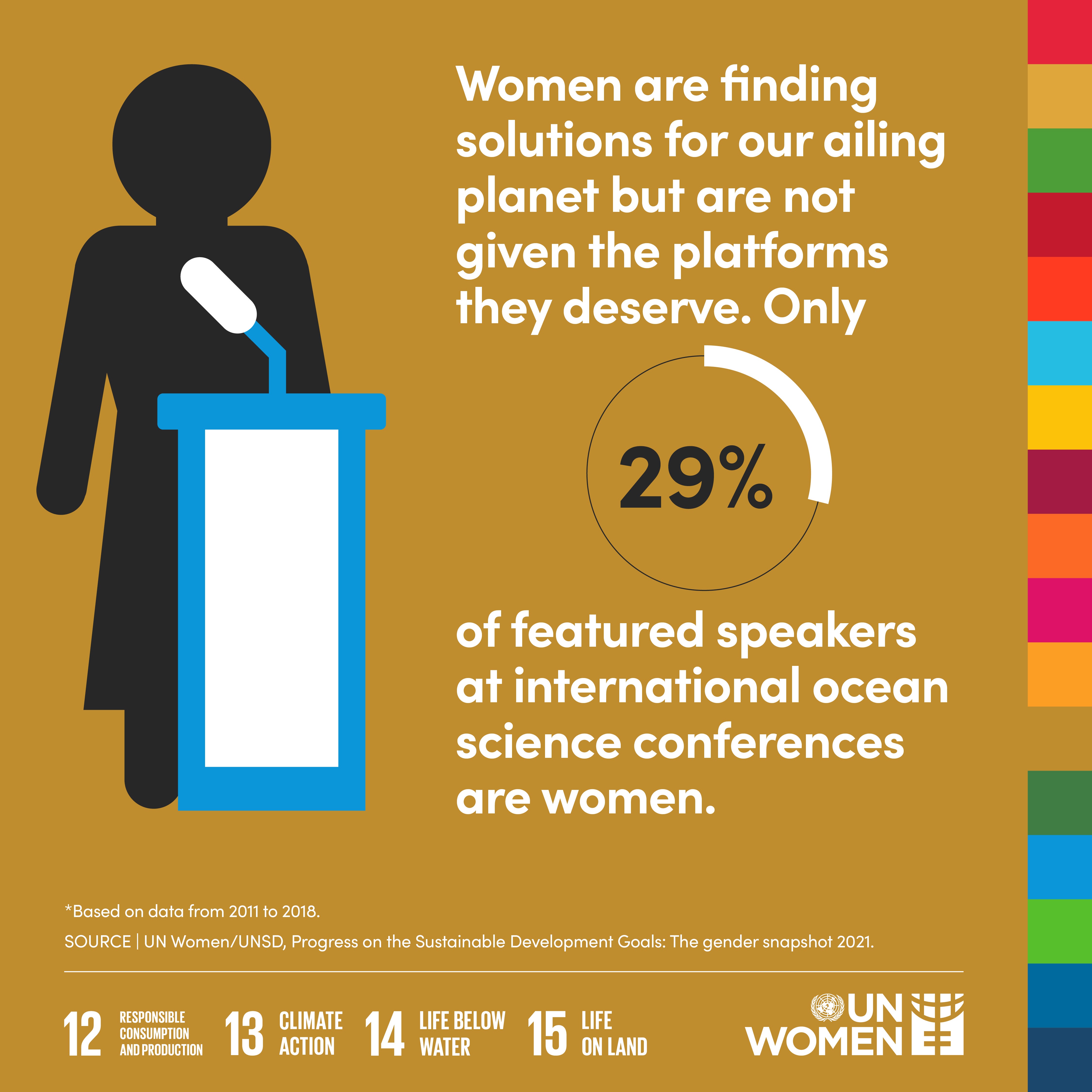

Goal 12. Sustainable consumption and production; Goal 13. Climate action; Goal 14. Life below water; and Goal 15. Life on land

Women activists, scientists and researchers are working hard to solve the climate crisis but often without the same platforms as men to share their knowledge and skills. Only 29 per cent of featured speakers at international ocean science conferences are women.

And yet we can change this .

Ensure women activists, scientists and researchers have equal voice, representation and access to forums where these issues are being discussed and debated.

Goal 16. Peace, justice and strong institutions

The lack of women in decision-making limits the reach and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and other emergency recovery efforts. In conflict-affected countries, 18.9 per cent of parliamentary seats are held by women, much lower than the global average of 25.6 per cent.

This is unacceptable .

It's time for women to have an equal share of power and decision-making at all levels.

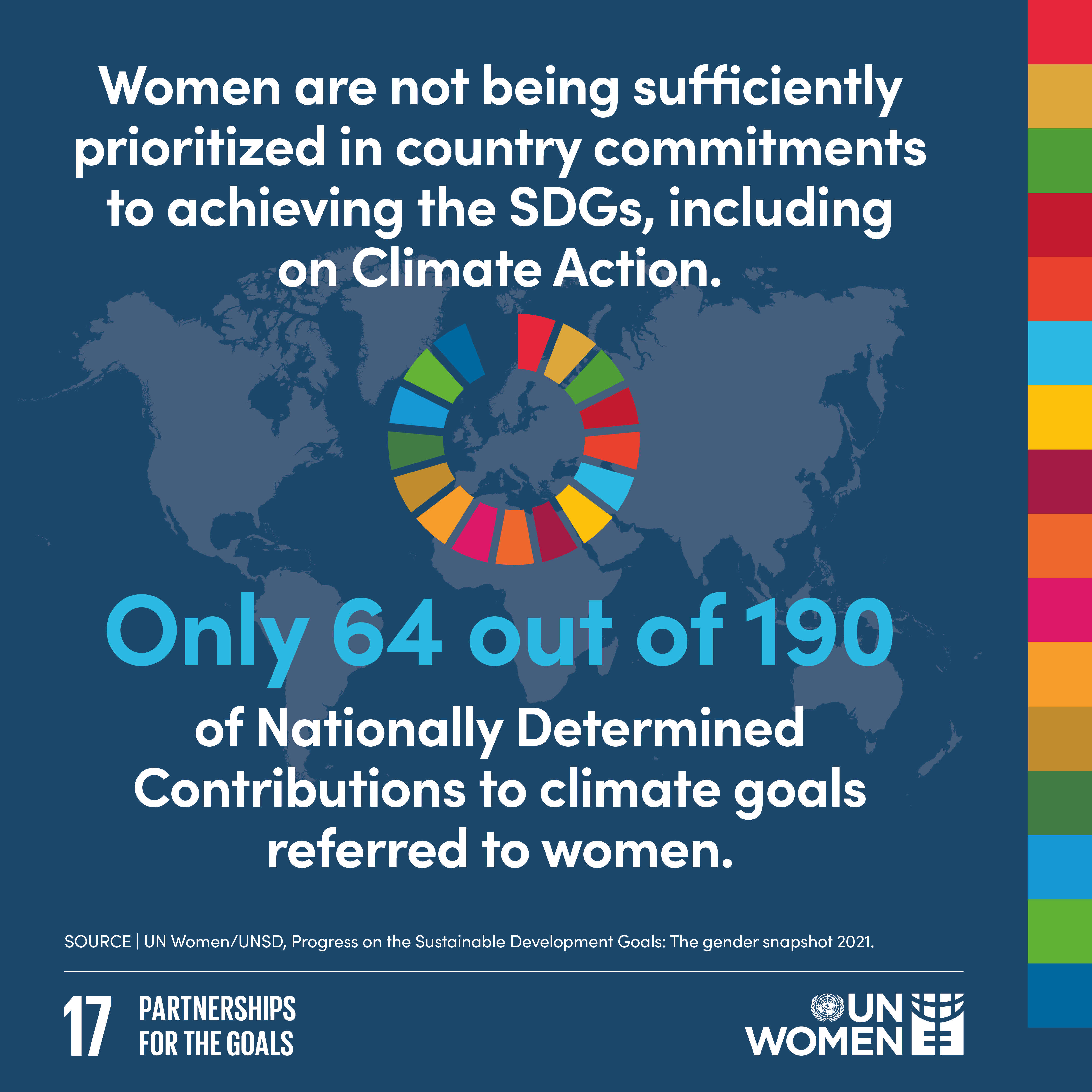

Goal 17. Global partnerships for the goals

There are just 9 years left to achieve the Global Goals by 2030, and gender equality cuts across all 17 of them. With COVID-19 slowing progress on women's rights, the time to act is now.

Looking ahead

As it stands today, only one indicator under the global goal for gender equality (SDG5) is ‘close to target’: proportion of seats held by women in local government. In other areas critical to women’s empowerment, equality in time spent on unpaid care and domestic work and decision making regarding sexual and reproductive health the world is far from target. Without a bold commitment to accelerate progress, the global community will fail to achieve gender equality. Building forward differently and better will require placing women and girls at the centre of all aspects of response and recovery, including through gender-responsive laws, policies and budgeting.

- About UN Women

- Executive Director

- Regional Director for East and Southern Africa

- Regional Director for West and Central Africa

- Announcements

- Guiding documents

- Report wrongdoing

- Procurement

- Regional and country offices

- Gender Data Repository

- UN Women in Action

- Enabling Environment

- Production of Quality Gender Data

- Uptake and Use

- Leadership and political participation

- Climate-Smart Agriculture

- Empowering Women in Trade

- Recognising, Reducing and Redistributing Unpaid Care Work in Senegal

- Regional Sharefair on the Care Economy

- The Gender Pay Gap Report

- Women in the green economy

- Intergovernmental support

- Africa Shared Research Agenda

- UN system coordination

- Peace and security

- Governance and national planning

- Policy and advisory support

- Youth Engagement

- Women’s Leadership, Access, Empowerment and Protection (LEAP)

- Programme implementation

- Representative

- South Sudan

- UN Women Representative In Sudan

- African Girls Can Code Initiative (AGCCI)

- African Women Leaders Network (AWLN)

- Spotlight Initiative

- Special Representative to the AU and UNECA

- Partnerships

- Côte d’Ivoire

- Democratic Republic of Congo

- Guinea Bissau

- Republic of Guinea

- Siera Leone

- In focus: International Women's Day 2024

- 16 Days of Activism Against Gender Based Violence Campaign 2023

- UN Women at Women Deliver 2023

- In focus: 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence 2022

- In Focus: World Humanitarian Day

- International Day of Rural Women 2022

- International Youth Day 2022

- International Women’s Day 2023

- International Day of Rural Women

- 76th Session of the UN General Assembly

- Generation Equality Forum in Paris

- Gender equality matters in COVID-19 response

- International Youth Day

- Media contacts

- Publications

- Beijing+30 Review

- Gender Journalism Awards

- About Generation Equality

- Generation Equality Forum

- Action packs

- 16 Days of Activism against Gender-based Violence

- Where We Work

Improving Gender Equality in Africa

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Africa is a continent still strongly marked by gender inequalities in all areas, which has a strong impact on women, whether from a social, economic, or political point of view. Despite this alarming fact, for several decades, changes have taken place to overcome gender discrimination against women and girls.

Women account for more than 50 percent of Africa’s combined population, but in 2018 generated only 33 percent of the continent’s collective GDP. This reinforces and fuels inequality and compromises Africa’s long-term economic health. Overall, progress toward gender equality has stalled over the past four years.

Reduced inequalities Limited progress for women is being eroded by the pandemic. Women facing multiple forms of discrimination, including women and girls with disabilities, migrant women, women discriminated against because of their race/ethnicity are especially affected.

Gender gaps favoring males|in education, health, personal autonomy, and more|are systematically larger in poor countries than in rich countries. This article explores the root causes of gender inequality in poor countries. Is the higher level of gender inequality explained by underdevelopment itself? Or do the countries that are poor today have ...

Recent shocks have worsened gender inequality in Africa. It is therefore important now, more than ever, to invest in strengthening fiscal systems to help women and men recover, withstand...

PDF | Gender denotes the social prescriptions associated with biological sex in regard to roles, behavior, appearance, cognition, emotions, and so on.... | Find, read and cite all the research...

Why addressing gender inequality is central to tackling today’s polycrises. Strengthening fiscal policy for gender equality systems. VIEWPO INT. Closing the gender gap through digital and...

Gender equality is a fundamental development objective, and is essential to enabling women and men to participate equally in society and in the economy. The World Bank’s Africa Region is dedicated to improving the lives of women and men by supporting government partners with knowledge and finance.

ThE STATE OF GENDER EQUALITy IN AFRICA: Trends, Challenges and Opportunities. Quality Assurance and Results Department, Gender and Social Development Monitoring Division of the African Development Bank. Summary.

Inequality, Gender Gaps and Economic Growth: Comparative Evidence for Sub-Saharan Africa; by Dalia Hakura, Mumtaz Hussain, Monique Newiak, Vimal Thakoor, and Fan Yang; IMF Working Paper 16/111; June 2016. 3. Table of Contents.