An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Five decades of research on foreign direct investment by MNEs: An overview and research agenda

Justin paul, maría m feliciano-cestero.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2020 Feb 26; Revised 2020 Apr 4; Accepted 2020 Apr 6; Issue date 2021 Jan.

Since January 2020 Elsevier has created a COVID-19 resource centre with free information in English and Mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID-19. The COVID-19 resource centre is hosted on Elsevier Connect, the company's public news and information website. Elsevier hereby grants permission to make all its COVID-19-related research that is available on the COVID-19 resource centre - including this research content - immediately available in PubMed Central and other publicly funded repositories, such as the WHO COVID database with rights for unrestricted research re-use and analyses in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source. These permissions are granted for free by Elsevier for as long as the COVID-19 resource centre remains active.

Despite the significance attached to foreign direct investment (FDI) by Multinational enterprises (MNEs), there are is no comprehensive review of the FDI literature. Moreover, those that have been published, focus on subsets of FDI. This review systematically examines the empirical as well as theoretical research on FDI through an analysis of 500 articles published during the last five decades. Theoretical models, methods, context, and contributions to scholarship were reviewed. We strive to highlight the key theories, paradigms, and articles and provide directions for future research. We conclude that FDI has evolved as the most significant area of international business.

Keywords: Foreign direct investment, MNE, Foreign subsidiary, OFDI, IFDI

1. Introduction

Foreign direct investment (FDI) by multinational enterprises (MNEs) represents one of the most researched phenomena in international business ( Blonigen, 2005 , Werner, 2002 , Paul and Singh, 2017 ). However, most reviews of the FDI literature do typically focus on a specific subset of FDI only (e.g., Buckley and Casson, 2009 , Chan et al., 2006 , Meyer, 2003 , Blonigen, 2005 , Fetscherin et al., 2010 , Klier et al., 2017 , Paul and Benito, 2018 ). For instance, Meyer (2004) surveyed the research on FDI spillovers in the context of emerging market economies. Chan et al. (2006) examined the interdependencies between FDI and MNE foreign-market-entry strategies. Blonigen (2005) reviewed past research on host-country-specific determinants of FDI. Buckley and Casson (2009) analyzed the progress of FDI research and internalization theory. Fetscherin, Voss, and Gugler (2010) conducted an interdisciplinary literature review on FDI in China.

Prior research shows the linkage between different variables such as corporate governance factors, entry and establishment modes, subsidiary performance and location choices ( Dikova, 2009 , Dikova and Sahib, 2013 , Lien et al., 2005 , Filatotchev et al., 2007 , Ambos et al., 2006 , Dikova and Van Witteloostuijn, 2007 , Ambos et al., 2011 , Hertenstein et al., 2017 ). In this context, our goal is to come out with the most comprehensive review of the MNE-FDI literature. We focused on FDI that occurs when MNEs invest in assets in foreign countries and establish some form of a subsidiary to execute market-seeking, strategic asset-seeking and/or efficiency-seeking activities ( Dunning, 1993 , Dunning, 1998 ). With coverage of all topics under FDI, our review highlights specific gaps in the extant literature and offer directions for future research.

Over the past four decades, MNE-FDI research has evolved from the analysis of investment flows to finer-grained investigations. This review includes topics ranging from the macro-level studies dealing with Outward FDI (OFDI) and Inward FDI (IFDI) to micro-level antecedents (motives for undertaking FDI), characteristics (mode of entry and growth strategies), and performance outcome of foreign subsidiaries of MNEs and international joint ventures (IJVs). It is worth to mention that FDI has been a popular and widely researched subject among both business and economics scholars.

The remainder of this review is structured as follows: In the next section, the methodological approach is described. The findings of the analysis are reported in section three. Similarly, we discuss some of the key contributions to the FDI literature focusing on theories and variables. Dominant theories applied were identified -including the eclectic OLI (Ownership, Location, Internalization) paradigm and internalization theory, amongst others- and provide a path to contrast the more established theories with those more recently introduced such as Conservative, Predictable and Pacemaker (CPP) model. Further, we provide a citation analysis of the most impactful articles and authors in the last five decades of research. Next, we identify the most widely used variables in FDI research such as IFDI and OFDI, locations and determinants, economic growth, FDI spillover effects, entry modes, MNE strategy, etc. Afterward, we report dominant research methodologies including statistical approaches. Finally, we provide suggestions for future research regarding theories, content, and methodology. The value of this review lies in its breadth and the exhaustiveness of the literature identified. It complements the focused sub-analysis of the past and therefore represents a valuable base reference tool for future MNE-FDI research.

2. Methodology

Systematic literature review articles could be of different types, namely – structured review focusing on widely used methods, theories and constructs ( Rosado-Serrano et al., 2018 , Canabal and White, 2008 , Paul and Singh, 2017 , Kahiya, 2018 , Hao et al., 2019 ); Framework based ( Paul & Benito, 2018 ), hybrid (Narrative with a framework) for setting future research agenda ( Paul and Singh, 2017 , Kumar, 2019 ), theory-based review ( Gilal et al., 2019 , Paul, 2019 ), meta-analysis ( Knoll & Matthes, 2017 ), bibliometric review ( Randhawa et al, 2016 ), Review aiming for model/framework development ( Paul and Mas, 2019 , Paul, 2019 ).

We deployed the process of a structured systematic literature review followed in widely cited review articles ( Keupp and Gassmann, 2009 , Canabal and White, 2008 , Rosado-Serrano et al., 2018 ). Our starting point was a content analysis of prior reviews of the FDI literature on different sub-themes (i.e., Meyer, 2003 , Blonigen, 2005 , Buckley and Casson, 2009 , Chan et al., 2006 , Fetscherin et al., 2010 , Dikova and Brouthers, 2016 , Paul and Singh, 2017 ). Next, we performed a keyword search across selected online databases, including Business Source Premier, JSTOR, ScienceDirect, ProQuest, and Google Scholar for the articles on FDI published during the last five decades. Keywords included Foreign Direct Investment, FDI, Inward FDI, Outward FDI, Multinational Enterprise, MNE, and Foreign Subsidiary. In the first phase, we incorporated empirical papers that used at least one statistical technique based on primary or secondary data. However, based on feedback from experts, we then also included selected high-impact theoretical articles (based on citation counts- minimum 500 citations) to identify key contributions to theory.

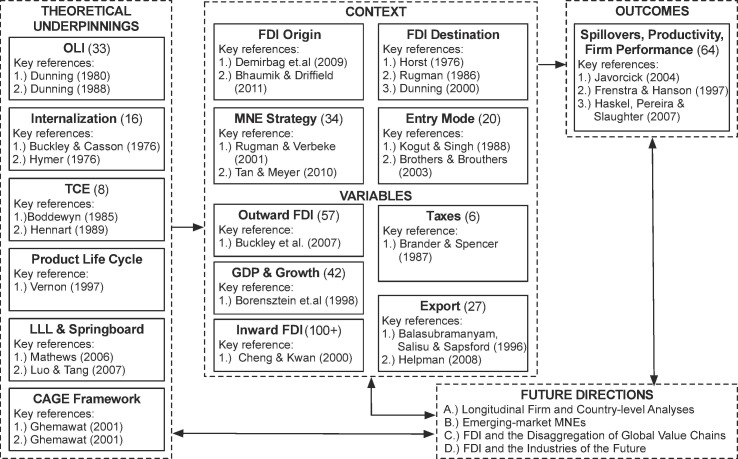

Furthermore, we checked journal websites independently to ensure that we had captured all published articles — a process that yielded over 600 articles. In the first round, we only include those studies that mentioned the terms “FDI” or “foreign direct investment” in the title, abstract, or keywords list. However, we included some other articles, looking at the relevant universe of articles subjectively, with a holistic approach (following Keupp and Gassmann, 2009 , Grant-Smith and McDonald, 2017 ), by analysing the insights and FDI-related content such as greenfield investment, acquisition, and subsidiary. Next, we reduced the total number of articles by excluding those that were not published in journals included in the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) completing our final sample with 500 articles. Additionally, we established a research agenda for the future, related to content (antecedents, characteristics, and outcomes of FDI) and methodology. Finally, we follow and expand on Keupp and Gassmann (2009) review method and create a structured catalog ( Appendix 1 ) of all reviewed FDI articles categorized by research topics, FDI characteristics, theories, and variables. Fig. 1 illustrates the organizing framework of this review.

Organizing framework.

3. Findings and discussion

Overall, we found that MNE-FDI research has not only been steady but that it has accelerated in-depth and breadth over the decades with a noticeable surge in publications in the last 15 years. It is observed that there is room for conceptual renewal within the field.

Altogether, 52 articles included in our sample were published between 1980 and 1999, 145 were published between 2000 and 2006, and 303 were published between 2007 and 2020. We suggest that one of the reasons for the surge in FDI research is the evolving nature of MNE internationalization characteristics, improvements in data availability from online sources after 1999, and advances in empirical techniques that lead to finer-grained analyses. The time period was divided with a break in 1999 because several agencies made the online data available for researchers by the late 1990s. This classification of time period helps us to understand the impact of such availability of data on the number of publications. In the following section, we will provide an overview of the key theoretical lenses that dominate MNE-FDI research. The goal is to identify seminal works, new theoretical developments, and interesting research ideas.

3.1. Review of theories

It was found that the most prevalent theoretical lenses applied in MNE-FDI research have been: (1) Internalization theory, (2) The eclectic OLI paradigm, (3) Product life-cycle (PLC) theory, (4) Institutional Theory, and (5) Resource Based View. Besides, theoretical models or frameworks such as (i) the Linkage, Leverage, Learning (LLL) model, (ii) the Springboard Perspective, and (iii) the CAGE Distance Framework, which were developed during the last decade, have been also used in FDI research. Those recent models deal particularly in the context of the rise of emerging market MNEs (EMNEs) and OFDI from developing countries. We discuss the scope of these theories/models critically in this section by classifying them as “widely-used theories/models” and “new theories/models”. Theories, models, and frameworks developed during the last two decades are included under the title “new theories/models”.

3.1.1. Widely used theories/models/paradigms

3.1.1.1. internalization theory.

Hymer (1976) contributed significantly to the development of this theory. Rugman (1980) provided an integrative framework for the existence of the MNE by integrating internationalization and internalization logic. Internalization ( Buckley and Casson, 1976 , Buckley and Casson, 2009 ) explains the motivation for firms to engage in FDI by exploring home-country (country of origin) internal firm-specific advantages (resources and/or capabilities) instead of relying on local factor endowments in individual foreign product markets ( Verbeke & Kano, 2016 ). Hennart, 1986 , Hertenstein et al., 2017 developed the internalization model further by extending it along with vertical and horizontal integration of MNE-FDI activities. This has spurred recent studies to draw on internalization theory to explain FDI in the context of regionalization and global value chain disaggregation ( Rugman and Verbeke, 2003 , Pak and Park, 2004 , Rugman, 2010 , Verbeke and Kano, 2016 ).

3.1.1.2. OLI paradigm

Dunning’s OLI paradigm (e.g., 1988, 2000) has been the most widely used lens in MNE-FDI research. This paradigm explains the way firms leverage resources - namely ownership advantages (O), location advantages (L), and internalization advantages (I) to compete in foreign locations ( Dunning, 2001 ). The use of the OLI paradigm remains in effect in contemporary FDI research. Over 30 studies in our sample were framed either along all three OLI dimensions or were focused on one of the dimensions in finer-grained approaches. For instance, Delevic and Heim (2017) stated that home market deficiencies are compensated by the host country's location advantages, and Cook, Pandit, Loof, and Johansson (2012) , using a geographical clustering approach for global cities, built on the L-advantages notion and found that more experienced MNEs and those with stronger home-country resource positions are more likely to engage in OFDI. One reason for the prevalence of the OLI paradigm might be that it forms a grounded starting point for developing other theories/frameworks that explain the evolving MNE-FDI phenomenon. Also, the OLI paradigm even if not represent a theory but allows linking international business phenomena with other theories – such as including transaction cost economics and the resource-based view - and also with other fields like economic geography. Despite the relevance of the OLI paradigm and its refinements, Dunning (2006) admitted that the unique context of OFDI from EMNEs could require a revision of some of its premises. Barkema, Chen, George, Luo, and Tsui (2015) pointed towards the difficulty of testing Western theories with Eastern constructs by discussing the properties of equivalence, salience, and infusion, and provided directions for creating new theories and paradigms. In addition, the OLI paradigm might not be suitable for explaining FDI patterns of new-generation firms (e.g., Cannon and Summers, 2014 , Ross, 2016 ) such as Google, Uber, Airbnb, and Bitcoin, which are asset-light and often virtual in their internationalization approach.

3.1.1.3. Product lifecycle (PLC) theory

PLC theory represents the focal theoretical lens in several FDI studies, though it has not received the same level of attention as the OLI paradigm in recent years. Vernon (1966) developed the theory based on FDI from U.S.-based MNEs in Western Europe after World War II — specifically, those in the manufacturing sector. Vernon identified four stages of production which he believed formed a continuous cycle: innovation, growth, maturity, and decline. As per this theory, firms undertake exports before thinking about production abroad in the form of FDI. The PLC theory suggests that capital-intensive and technologically sophisticated innovations are typically developed for the domestic market and progress through various stages in which production shifts to other (mainly) developed countries and, finally, to developing countries; such as Contractor, Dangol, Nuruzzaman, and Raghunath (2019, p.2) that indicate that “multinational companies are willing to take the risk by investing in a country with a lower institutional quality at one stage of the investment’s life-cycle in exchange for a more developed institutions, or easier regulations, at another stage of the life cycle”. The scope of PLC theory is not limited to FDI research. It is being applied in other fields as well, such as marketing, where PLC theory was particularly popular in the 1980s and 1990s ( Calvet, 1981 , Boddewyn, 1983 , Kim and Lyn, 1987 , Treviño and Daniels, 1995 ).

3.1.1.4. Institutional theory

Other theories used in FDI research include the institutional theory and the dynamic capabilities theory. According to institutional theory, organizational structures and behavior are to a large extent determined and legitimated by the surrounding environment (e.g., Eisenhardt, 1988 , Child, 1997 ). Several studies have applied institutional theory while focusing on the choice of appropriate organizational forms such as IJVs versus wholly-owned subsidiaries for foreign market entry (e.g. Li and Meyer, 2009 , Roy and Oliver, 2009 , Peng, 2003 , Yiu and Makino, 2002 , Lu et al., 2018 ). Meyer (2004) highlighted the relevance of institutional theory when considering and deciding on the suitability of different market-entry modes for EMNEs from emerging countries. Some researchers ( Cui and Jiang, 2012 , Deng, 2013 , Delevic and Heim, 2017 ) have used institutional theory to explain that EMNEs are subject to institutional constraints such as state interference.

3.1.1.5. Resource-based view (RBV)

RBV has been used in FDI research mainly in the context of OFDI from developing countries. RBV is an approach used to explain how firms achieve competitive advantage while going international. RBV gained popularity in the 1980s and 1990s, after the major works published by Wernerfelt, 1984 , Barney, 1991 . Ghoshal (1987) was one of the pioneers in applying RBV to international business. The proponents of the RBV argue that firms should look internally to find the sources of competitive advantage instead of searching for it in the external competitive environment. In this approach, resources are classified as either tangible or intangible. One of the key factors is that intangible resources (such as intellectual property rights and brand equity) are the main sources of sustainable competitive advantage ( Wernerfelt, 1984 , Barney, 1991 ). Some researchers have applied RBV in the context of OFDI from EMNEs ( Cui and Jiang, 2009 , Cook et al., 2012 , Lin, 2016 , Gaur et al., 2018 ).

3.1.2. Recent models/frameworks

In this sub-section, we briefly discussed the recently developed models/frameworks used/ could be used in future research in the context of MNE-FDI Research.

3.1.2.1. Linkage, leverage, learning (LLL) model

In recent years, the LLL model and the Springboard Framework (discussed below) have gained immense popularity because of their utility in explaining the specific determinants, motivations, and processes of outward OFDI from EMNEs. With the LLL framework, Meier, 1984 , Meyer, 2003 extended the OLI framework to EMNEs with strategic asset-seeking FDI. The LLL framework explains the way EMNEs from peripheral countries in the Asia-Pacific region established themselves successfully in more developed countries. Mathews (2002) suggested that FDI, in pursuit of new capabilities, requires a different perspective than FDI meant to exploit existing capabilities. EMNEs can develop capabilities to the maximum, such that they can globalize ( Hobdari, Gammeltoft, Li, & Meyer, 2017 ) and, also, EMNEs engaged in OFDI from emerging countries, often, enter late to already developed markets and thus principally exhibit catch-up strategies. EMNEs frequently exhibit accelerated or even leapfrogging internationalization patterns. Most researchers have used the LLL model in the context of the internationalization of Asian firms - particularly Chinese firms. For instance, Ge and Ding (2009) applied the LLL model to demonstrate how Chinese firms, such as Galanz Group, developed unique competitive strategies that helped them succeed in foreign markets. On the other hand, Narula (2006) argued that the tenets of the LLL model are interesting, but it proposed modifications, in comparison to the OLI paradigm, seem less than convincing.

3.1.2.2. Springboard perspective/theory

Luo and Tung (2007) Springboard Perspective explains why and how EMNEs will systematically and recursively use international expansion as a springboard to acquire critical resources for competition in their home markets with foreign MNEs from developed markets. This is a very useful tool for researchers, particularly those who examine different aspects of OFDI from EMNEs - which still lacks widespread attention. The authors have developed a general theory of springboard MNEs based on amalgamation, ambidexterity, and adaptation advantages that differentiate springboard EMNEs from more established MNEs from developed countries ( Luo & Tung, 2018 ).

3.1.2.3. CAGE distance framework

Ghemawat, 2001 , Ghemawat, 2003 CAGE (Cultural, Administrative, Geographic, Economic) Distance Framework, while being applicable to both developed and emerging country contexts, seems especially useful to understanding the internationalization processes of EMNEs. It is surprising that the CAGE framework is widely recognized but not yet widely applied. One reason for this could be that the original article did not offer easy-to-use measures. However, some researchers have used the CAGE framework in their studies to analyze distance factors and MNEs’ FDI ( Goodall and Roberts, 2003 , Juasrikul et al., 2018 , Mudambi, 2008 , Malhotra et al., 2009 , Rugman & Verbeke, 2004 ). The CAGE distance calculator has introduced a decade ago ( Ghemawat, 2007; Rugman & Verbeke, 2004 ), and we expect more researchers to use this measure in the future.

3.1.2.4. CPP model

Paul and Sanchez-Morcillo (2019) introduced the Conservative, Predictable and Pacemaker (CPP) model, for analysing the internationalization of firms. This model could be used as a classic theoretical lens in research dealing with FDI. Researchers can undertake studies exploring the destination and pattern of FDI classifying the markets as Predictables and Pacemakers. Global competitiveness measurement is also possible using the ratio mentioned in the CPP Model propositions. Industry-wise FDI flows can also be analysed using the CPP model in either single-country context or using cross-country data.

3.2. Citation analysis

To identify the most influential articles on FDI, we conducted a citation analysis. We registered the total number of citations ( C total ) and computed the average weighted citation scores C total ¯ = C total # o f y e a r s a f t e r a r t i c l e p u b l i c a t i o n . The most cited articles identified were Borensztein, Gregorio, and Lee (1998) , with 8279 citations, Dunning (1988) , with 6057 citations, Dunning (1980), with 4263 citations, and Smarzynska Javorcik (2004) , with 3923 citations (See Table 1 ). The most cited articles were published in the Journal of International Economics , Journal of International Business Studies , and American Economic Review ; thus, these articles were not strictly confined to business journals. Empirical articles with more than 2000 citations (as of January 30, 2020) include Feenstra and Hanson, 1997 , Balasubramanyam et al., 1996 , Markusen and Venables, 1999 , Dunning, 2000 , Helpman, 2006 , Cheng and Kwan, 2000 .

Most cited articles & authors on FDI (as of January 30, 2020).

We also examined the citations of the conceptual articles on FDI, of which two recent ones have received the bulk of citations. Mathews (2006) “Dragon multinationals: New players in 21st-century globalization” have been cited over 2000 times and Luo and Tung (2007) “International expansion of emerging market enterprises: A springboard perspective” has generated over 2500 citations, as on January 30, 2020. While it was found that most of the extant empirical FDI research has relied conceptually on the work of Dunning, 1981 , Dunning, 2000 & 2006 ), Mathews (2006) , and Luo and Tung (2007) works have gained attention in the recent years. This could be partly because of the rising research interest in EMNEs.

Unsurprisingly, review articles have generated a relatively higher weighted annual average citation scores. For example, Blonigen (2005) gained 1777 citations with a high average weighted citation score of 118 per year. This could, possibly, be because of two reasons: (i) Review articles are frequently used as foundation papers by doctoral students and early career researchers in economics as well as international business areas, and (ii) traditional FDI theories are rooted in economic theories and international economics is regarded as the mother discipline of international business.

3.3. Context

A key reason for increased interest in EMNE-FDI research might be that while developed-country MNE-FDI outflows have dominated the global share of FDI activities until recently, the share of FDI from EMNEs has increased sharply over the past 15 years ( Luo and Tung, 2007 , Demirbag et al., 2009 , Paul and Benito, 2018 ). EMNE-OFDI now accounts for more than one-third of the global FDI outflows ( UNCTAD, 2015 ). “EMNE-FDI to other developing countries grew by two-thirds from $1.7 trillion in 2009 to $2.9 trillion in 2013” ( UNCTAD, 2015, p. 8 ).

Despite its long tradition, FDI research that investigates the relationships between FDI and FDI-receiving-country determinants remains buoyant (e.g., Horst, 1976 , Bergsten et al., 1978 , Ruigrok et al., 2007 , Rutherford et al., 2018 , Dunning, 2000 , Mudambi and Mudambi, 2002 , Anwar and Nguyen, 2011 ). Enderwick (2005) found that the benefits derived from MNE activities for FDI-receiving countries depend on quality rather than quantity. Higher-quality FDI includes investments focused on technology or research and development (R&D) that can lead to, for example, knowledge spillovers to other firms in FDI-receiving locations. Alfaro et al., 2004 , Durham, 2004 found that the realization of these benefits is dependent on the absorptive capacity of local firms in FDI-receiving countries. While the general understanding of host-country determinants (e.g., regulatory, political, economic, and cultural institutions) that stimulate FDI has progressed considerably, findings concerning the effects of FDI on receiving countries remain mixed. FDI host-country effects range from positive to insignificant, to negative - depending on the conceptual lens or the contextual setting deployed in a specific research project (e.g. Alvarez and Marin, 2013 , Asiedu et al., 2009 ).

With the large scale emergence of EMNEs, research has gathered momentum in this area. For example, Kedia, Gaffney, and Clampit (2012) posited that an EMNE strategic orientation predicts its propensity to engage in knowledge-seeking FDI and that the type of knowledge sought predicts location choice and entry mode. In recent years, OFDI characteristics related to MNE home countries have attracted increasing attention amongst scholars ( Sauvant, 2005 , Kedia et al., 2012 ). Here, research on EMNEs is experiencing a particularly strong surge (e.g. Filatotchev et al., 2007 , Bhaumik and Driffield, 2011 , Cui and Jiang, 2009 , Cui and Jiang, 2012 ). Several focused journal issues and summary papers have now begun to discuss the characteristics of EMNE internationalization processes - shedding more light on the subject (e.g., Kearney, 2012 , Gray et al., 2014 , Cuervo-Cazurra et al., 2014 ).

The ratio of developing countries in global OFDI to both developed as well as other developing countries has increased considerably since 2000 ( UNCTAD, 2015 ). Outward investments by EMNEs based in developing Asia increased every year during the last 10 years. This growth was widespread, encompassing all the major Asian economies, which made developing Asia the world’s largest outward investor region. EMNEs have undertaken international expansion through greenfield investments as well as cross-border acquisitions.

However, it is worth noting that MNEs from the United States (US) have remained dominant in generating FDI outflows on a home-country basis ( UNCTAD, 2015 ), which is also reflected in the number of research studies that draw on U.S. -based MNE-FDI data. Furthermore, the US, China, and Japan have been most often studied in the context of outward MNE FDI ( see Table 2 ). The reasons for this might lie in (a) the magnitude of outward MNE FDI from these three countries and/or (b) the fact that data from these countries are more easily obtainable and that they thus provide better opportunities for quantitative analyses. Only a handful of studies have so far examined outward MNE-FDI from other countries such as India, Turkey, etc. (e.g., Bhaumik and Driffield, 2011 , Narayanan and Bhat, 2011 , Demirbag et al., 2009 ).

Primary home and host countries/regions studied in FDI research.

China and the US are the most researched FDI-receiving countries, with the former recording the highest FDI inflows for 2013 as well as 2014. Also, the US is the most commonly host-country, followed by all developing countries as a group, such as the United Kingdom, Germany, and the Central & Eastern European countries. Table 2 rank-orders the most frequently researched home and host countries in FDI studies.

3.4. Constructs and variables

In this section, we identify the widely investigated constructs and variables, including, IFDI, OFDI, gross domestic product (GDP)/economic growth, exports and FDI, uncertainty and risk, FDI, entry and establishment modes, spillovers, technology, productivity, and firm performance, MNE strategy, and taxes. Table 3 categorizes the most frequently used dependent and independent variables.

Main variables studied in FDI research.

3.4.1. Inward FDI (IFDI)

The most commonly used construct in FDI studies is IFDI, with over 100 appearances. IFDI research has been mainly concerned with various host-country determinants that are associated with attracting firms to specific locations (e.g., Balasubramanyam et al., 1996 , Balasubramanyam et al., 1999 , Borensztein et al., 1998 , Alguacil et al., 2002 , Chakraborty and Basu, 2002 , Liu et al., 2002 , Buckley et al., 2006 , Baharumshah and Thanoon, 2006 , Delevic and Heim, 2017 ). The most frequently investigated determinants include market size, government policies (including entry barriers, cost of production, and wage rate), infrastructure, etc. (e.g., Kobrin, 1976 , Rolfe et al., 1993 , Loree and Guisinger, 1995 , Luo and Tan, 1997 , Reiljan, 2003 , Ramamurti and Doh, 2004 , Blonigen, 2005 , Galan and Gonzalez-Benito, 2006 , Blonigen and Piger, 2014 ). Ramamurti and Doh (2004) found that the 1990s witnessed a boom in FDI flow in developing countries (particularly in infrastructure sectors) that were characterized by weak institutions and political instability. Meyer and Nguyen (2005) offered a theoretical framework to analyze how institutions in an emerging economy influence MNEs’ entry strategy decisions on where and how to set up operations. They found that sub-national institutional variables influence significantly location and entry mode. Similarly, Feils and Rahman (2011) revealed that after regional integration exists an increase in IFDI into neighboring countries. On the other hand, Jin, García, and Salomon (2018) observed that IFDI affects more innovative firms than straggling ones. Table 4 lists some of the notable recent papers on IFDI, their principal conceptual arguments and findings, and empirical approaches.

Inward FDI.

3.4.2. Outward FDI (OFDI)

The second most used construct in FDI research is OFDI, with over 50 appearances. Studies concerned with OFDI seek to explain FDI motives, FDI determinants, and characteristics of MNEs regarding their particular home countries (e.g., Stevens and Lipsey, 1992 , Desai et al., 2005 ). Some researchers in the recent past have investigated how to encourage or even participate in corporate OFDI to facilitate the internationalization of private as well as state-owned firms from emerging countries ( Kearney, 2012 , Gray et al., 2014 , Cuervo-Cazurra et al., 2014 ). Although the emerging market MNE internationalization phenomenon is not new, its rapid increase in scale only started in the early 2000s ( Ramamurti and Singh, 2009 , Luo et al., 2010 ). A key part of this development is arguably due to the rise of Chinese (see, for example, Buckley et al., 2006 , on the determinants of OFDI from China) and Indian MNEs ( Rienda, Claver, & Quer, 2013 ) - have become major sources of OFDI. In emerging countries, the pattern of OFDI is shaped by local firms’ idiosyncratic contexts such as business groups (a dominant organizational form in emerging countries) and the resources that those firms developed to fit the contexts ( Tan and Meyer, 2010 , Lin, 2016 ). Chari (2013) found a positive relationship between business group affiliation and OFDI overall, in the case of firms from developing countries using Indian data as well as between business group affiliation and OFDI into advanced countries. Ali, Shan, Wang, and Amin (2018) results showed that positive or negative changes in outward FDI trigger meaningfully economic growth in China, demonstrating asymmetry between OFDI and economic growth relationship. Table 5 lists recent papers on OFDI.

Outward FDI.

In this context, it is worth noting that Paul and Benito (2018) developed a framework (Antecedents, Decision characteristics and Outcome – ADO) to explain and analyze the OFDI by MNEs from emerging countries including China. Considering the increased volume of OFDI from emerging countries, they argue that studying antecedents (A) is prudent because such works would give a clear idea about key motives of companies for undertaking international expansion from emerging countries while understanding Decision (D) characteristics provides a strategic platform to examine the dimensions such as entry and establishment modes, location, size and volume and timing of OFDI. Studies on Outcomes (O) usually seek to discuss variables such as performance after innovation, technology and knowledge transfers including reverse transfers and goes beyond financial results to encompass strategic outcomes such as survival or success of the firms involved in FDI.

3.4.3. GDP and FDI

Host-country GDP has been used most often in FDI research, both as an independent and a dependent variable. However, research investigating the relationship between GDP and MNE-FDI is characterized by somewhat diverging findings. For example, Angresano, Bo, and Muhan (2002) found that real GDP has a considerable positive effect and that GDP growth has a minor positive effect on FDI inflows. Hsiao and Shen (2003) identified a reciprocal relationship between FDI and GDP growth. However, by drawing on data from 28 developing countries, they found that FDI has neither consistent long-term nor short-term effects on GDP growth. Findlay (1978) investigated the role of FDI as a carrier of foreign technology, claiming that it could increase economic growth. Using simultaneous equation methods, Ruxanda and Muraru (2010) obtained evidence of a circular self-reinforcing relationship between FDI and economic growth, meaning that incoming FDI stimulates economic growth and that, in turn, a growing level of GDP attracts new FDI. Anwar and Nguyen (2010) found similar results. Table 6 lists recent papers that investigate the relationships between GDP, economic growth, and FDI.

GDP, economic growth, and FDI.

3.4.4. Exports and FDI

Exports were used as a variable in 30 FDI studies that have investigated the effects of international trade and FDI. This research stream often takes an evolutionary perspective on the MNE and host-country development. Economic theorists have focused on the complementary versus substitute relationship of exports and FDI (e.g., Bhasin and Paul, 2016 , Marin, 1992 , Meier, 1984 ), culminating in the export-led growth thesis. Conversely, some recent studies have analyzed the relationship between FDI and exports further by taking a unified approach which postulates the simultaneous determination of the two MNE activities in developed countries ( Markusen & Maskus, 2002 ). Alternatively, Aurangzeb and Stengos (2014, p. 141) performed an empirical study and concluded: “that countries with higher levels of FDI inflows have higher factor-productivity in the exports sector”. Table 7 lists recent papers that integrate and/or contrast research on exports and FDI.

Exports and FDI.

3.4.5. Uncertainty and risk

Uncertainty and risk have been used as focal constructs in 43 FDI studies. Cushman (1985) examined how uncertainty acted as a determinant of FDI location. There is evidence that the high risks associated with some FDI destinations ( Gatignon and Anderson, 1988 , Miller, 1992 ) discourage FDI. Ly, Esperança, and Davcik (2018) examined the effect of information on FDI, taking into account the country of origin's effect on the FDI’s pattern, multinational companies' attitudes toward risk and institutional factors. Schotter and Beamish (2013) suggested that besides traditional location choice criteria — including geographic distance, psychic and cultural distances, and market attractiveness — MNEs should consider managerial preferences. They found that managers influence FDI decisions based on travel inconveniences experienced with FDI locations and called this phenomenon the “Hassle Factor.” Hajzler (2014) explored the effects of different types of FDI incentives on magnitude and output performance and found that incentives are effective.

3.4.6. Entry modes

We found 24 studies in our sample focusing on FDI equity-based entry modes such as wholly-owned subsidiaries and equity joint ventures using firm-level data from MNEs ( see Table 15 in Appendix ). Most of these studies focused on entry modes, entry barriers, and mode switching. Brouthers and Brouthers (2003) found that the investment-intensive nature of manufacturing, environmental uncertainties, and risk propensity influence manufacturers’ entry-mode choices, while behavioral uncertainties, trust propensity, and asset specificity influence service providers’ entry-mode choices. Meyer, Ding, Li, and Zhang (2014) analyzed equity stake decisions, that drive MNEs to choose between two establishment mode routes: greenfield or acquisition. Delios and Beamish (2001) examined the influences that a firm’s intangible assets and its experience have on foreign subsidiary survival and profitability using a sample of 3080 subsidiaries of 641 Japanese firms. They show that survival and profitability have different antecedents. Host country experience has a direct effect on survival but a contingent relationship with profitability; this relationship is moderated by the entry mode. Luo (2001) found that entry-mode selection in an emerging economy is influenced by situational contingencies at four levels: nation, industry, firm, and project. He suggested that the joint venture’s mode is preferred in China when perceived governmental intervention is high or host-country experience is low. Chung, Xiao, Lee, and Kang (2016) showed that institutional pressures exerted by the home-country government have a significant effect on the OFDI mode decisions of Chinese firms. Those Chinese MNEs facing greater institutional pressures from their own government are more inclined to choose joint ventures over wholly-owned foreign subsidiaries when investing abroad.

3.4.7. FDI, spillover effects, performance, and strategy

The spillover effects of FDI, on technology transfer, firm-level productivity, and performance of subsidiaries, was seen in over 60 studies examined. (Ex, Ambos et al., 2006 , Ambos and Birkinshaw, 2010 ; see Table 17, Appendix 1 ). Subsidiary performance improves with (i) the integration of a parent firm's technological and marketing knowledge resources, (ii) high technological (market) relatedness between a parent firm and subsidiaries for transfer of parent technological (market) knowledge, and (iii) the co-presence of high technological and market relatedness ( Fang, Wade, Delios, & Beamish, 2013 ). Furthermore, Piperopoulos, Wu, and Wang (2018) suggest that spillovers can boost learning and enhance innovation in emerging market enterprises subsidiaries. On the other hand, Luo (2005) explains why competition occurs and in what areas foreign sub-units of a geographically dispersed MNE co-operate and compete. This augments a typology that classifies sub-units along with the various levels of simultaneous cooperation and competition (aggressive demander, silent implementer, ardent contributor, and network captain).

Jeon, Park, and Ghauri (2013) tested whether horizontal and vertical FDI spillover effects are different among various industries in China and found that foreign investments in the same industry are more likely to engender negative influences on local firms. China’s outward foreign direct investment promotes “the development of the home country through various channels of spillovers as well as the backward linkage of MNEs with parent companies” ( Ali et al., 2018, pp. 710–711). Lee and Rugman (2012) examined two types of firm-specific advantages (FSAs) — innovation capabilities measured by R&D intensity and marketing capabilities measured by selling, general, and administrative intensity. The results showed that both FSAs affect MNE performance in a non-linear, U-shaped fashion and that the investing MNE’s home region moderates the curvilinear relationship between the two constructs into an inverted U-shaped one. Sánchez-Sellero, Rosell-Martínez, and García-Vázquez (2013) investigated the determinants of absorptive capacity from FDI spillovers and found that firm behavior, capabilities, and structure drive absorptive capacity such as R&D activities and expenditures, R&D results, internal organization of innovation, external relationships of innovation, human-capital quality, family management, business complexity, and market concentration. Their results complement previous evidence of absorptive capacity, particularly with different approaches to innovation activities as mediators of the capability.

The results of the empirical tests linking the relationship between internationalization and MNE performance vary significantly and reflect the diversity of research (for example, Chen and Tan, 2012 , Ruigrok et al., 2007 , Prange and Verdier, 2011 ). It is worth noting that Bausch and Krist (2007) address the question of if and how internationalization relates to firm performance by integrating findings from 36 studies using meta-analysis. They found empirical support for a significant positive relationship at the aggregate level. Similarly, Chen and Tan (2012) examined the relationship between internationalization and firm performance using the data of 887 publicly listed Chinese firms (and the geographic region to which they internationalize) by classifying the regions as Greater China, Asia and outside Asia. While they found a positive and significant relationship between internationalization (within Greater China) and performance, their results varied between internationalization outside Asia and within Asia.

It was found that 8 studies in our sample investigated taxation in the context of FDI ( see Table 16, Appendix 1 ). Hajkova, Nicoletti, Vartia, and Yoo (2006) explored the impact of taxation on FDI while controlling several, policy and non-policy, factors. They found that taxation and the business environment are the main drivers of FDI in OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries. De Mooij and Ederveen (2003) found that most studies were reporting a negative relationship between taxation and FDI, but that there was a wide range of estimates of the tax elasticity of FDI. Also, Mutti and Grubert (2004) investigated empirical asymmetries associated with the effects of taxation on foreign operations by U.S. MNEs; and Shirodkar and Konara (2017, p. 117) confirmed that “the tax rate in the host country can have a negative effect on subsidiary profit”.

3.5. Data and methods

In this section, an overview of the methodologies used in existing FDI research, including datasets and statistical approaches is provided.

3.5.1. Data

Over 80 percent of all studies in our sample used publicly available secondary data. This could very well be due to relatively easy access to secondary data through sources such as the UNCTAD or due to the difficulty of collecting primary data. The most commonly used datasets include the Kaigai Shinshutsu Kigyou Souran Kuni-Betsu dataset on Japanese overseas investments, published by Toyo Keizai Inc. ( Toyo Keizai, 2014 ), various United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) statistics, the International Monetary Fund’s financial statistics, the World Bank database, Compustat data, and various other hand collected statistics from China. The popularity of the Kaigai Shinshutsu Kigyou Souran Kuni-Betsu dataset can be attributed to the richness and granularity of firm-level and subsidiary characteristics. This dataset represents a near population size, longitudinal record of Japanese MNE-FDI ( Schotter & Beamish, 2013 ). More than 120 research papers (not all on FDI) have been published based on various iterations of this dataset alone.

3.5.2. Statistical methods

We found that the most commonly used statistical method in FDI research was ordinary least squares (OLS) regression (127 studies). Other widely used statistical methods included the Granger causality test, co-integration analysis, vector autoregression (VAR), and cross-sectional analysis. Table 8 lists the main statistical empirical methods used in FDI research.

Main statistical methods used in FDI research (1980–2015).

4. Future research agenda

It was found that the extant FDI literature is diverse but on the other hand still relies on a limited number of theoretical lenses. One of the limitations of this review is the possible exclusion of some articles on FDI as it covers so many concepts such as greenfield investment and acquisition. Nevertheless, an attempt has been made to cover maximum articles. Merely 10 percent of the reviewed articles explicitly sought to extend or develop new theories. Going forward, new theory development should be at the core of future FDI research, to recognize the changes and developments in the phenomenon and taking into account potential, path, process, pattern, process and problems associated with the MNEs and FDI. These changes are driven by developments at the country level, inter-country level and, most importantly, MNE level. This seems particularly necessary, considering that prior empirical FDI research suffered to a significant extent from statistical robustness issues of the main variables. In this section, we offer directions on how to complement the dominant theoretical logics following Barkema et al. (2015) example.

4.1. Future directions for theory development

Although FDI researchers have introduced some new frameworks and constructs, it appears that Dunning’s (1980) OLI paradigm still represents the most dominant theoretical starting point for new MNE FDI research. It has been used repeatedly in FDI research in a recycled way. While we do not challenge such an approach, we find that it has limited, to a certain extent, new theory development. Therefore, we call for new and novel theories to use in this area of research. We suggest that with the rise of EMNEs and the emergence of new industries ( Cannon and Summers, 2014 , Ross, 2016 ) and new corporate firms like Google, Uber, and Bitcoin, recently developed theories/models such as CPP (Conservative, Predictable & Pacemaker markets and firms), Model for firm internationalization ( Paul & Sanchez-Morcillo, 2019 ) or 7-P framework ( Paul & Mas, 2019 ), based on Potential, Path, Process, Pace, Pattern, Problems and Performance, can be used as a theoretical lens in future. Although 7-P framework was originally developed for international marketing, its use can be extended in the area of FDI research as almost all the P-variables would serve as platform for future research.

New theories could be developed for analyzing the new forms of FDI. Dunning’s work and Vernon’s PLC theory were developed based on OFDI by MNEs from the developed world and mostly from traditional (and often manufacturing) industries, which creates only limited relevance for the aforementioned emerging phenomena. Further, research on EMNE-OFDI has so far looked at a limited number of determinants and is based on EMNE data from a very limited number of home countries (mainly China). We suggest that for EMNE research, in particular, the LLL ( Mathews, 2006 ), Springboard Perspective ( Luo & Tung, 2007 ) and ADO framework (2018) provide potentially better fitting and organized starting point for research on EMNEs. Similarly, it would be insightful if researchers use frameworks such as (i) Luo (2005) typological framework (aggressive demander, silent implementer, ardent contributor, and network captain) to analyze the simultaneous cooperation and competition between geographically dispersed sub-units of MNEs (ii) Paul and Sachez-Morcillo (2019)’s CPP, model to explore the direction and pattern of FDI. We also argue for developing new theoretical models, methods, measures, and frameworks to analyze, explain and discuss different aspects of FDI to make sure that researchers do not run short of new research agenda and to avoid recycled and repeat type research.

Another interesting outcome from this review is that only a limited number of studies (e.g., Andersson, Forsgren, & Holm, 2002 ) have investigated how entry modes influence the evolution of post-FDI strategy. We suggest that utilizing contingency models from the strategy domain might create an opportunity to more accurately connect country-level and firm-level FDI research with the literature on MNE strategy. Another area of opportunity lies in comparative analyses in the context of FDI from developed countries and developing countries while drawing on existing models, including the CAGE framework ( Ghemawat, 2001 , Ghemawat, 2003 ). Previous theory development has been based on the notion that most MNE-FDI is directed toward predictable markets (markets with similar features in terms of cultural, administrative, geographical, and economic distance). This notion is likely a result of firms avoiding dealing with any liability of foreignness issues, problems arising from cognitive biases, and resource constraints. Today’s level of economic development of emerging markets and the level of developed market-bound investments by EMNEs ( Mathews, 2006 , Luo and Tung, 2007 , Demirbag et al., 2009 ) should provide ample opportunities for such research. It is also worth extending the institutional theory and RBV in such studies. For instance, there are opportunities to develop theories and frameworks and extend the available theories to explain the FDI phenomenon of emerging market firms - in particular, Asian firms. This is true especially considering that Asia has emerged as a strategically important region. There are opportunities to develop separate frameworks to analyze the path, process, pace, pattern, problems, and potential of MNE investment concerning the past, present and future all within the context of strategy. For example, there is scope for developing theories that explain the pace of internationalization regarding entry mode switch from exporting to FDI.

4.2. Future directions on FDI antecedents, characteristics, and outcomes

FDI research has advanced our knowledge of the antecedents, characteristics, and outcomes of entry modes. However, the extant research base is diverse and somewhat fragmented. In this section, we highlight opportunities for future research.

Many studies focus on FDI antecedents, including firm-level investment motives and a broad range of home-country and host-country determinants. However, although the number of existing studies gives the impression of being large, the existing literature appears fragmented and often the focus on certain antecedents seems somewhat arbitrary. This provides an opportunity for future research to integrate FDI antecedent research methodologically and conceptually. For the methodological research, we suggest that primary data be collected from the senior managers of MNEs to understand and explain the path, process, and pace of FDI they have undertaken. This includes analysis of motives and determinants of International Joint Ventures (IJV): foreign subsidiaries of MNEs.

Research on FDI characteristics (location, entry modes, etc.) is relevant for examining how FDI evolves over time and across different industries and countries. Current FDI research is largely cross-sectional, in nature. We suggest investigating longitudinal FDI patterns using firm-level data for different industries and countries. We believe that characteristics-based studies offer ample potential for future research. In this regard, we feel that it would be interesting to examine the linkage between business groups and the mode of entry into foreign countries. For example, research on the pertinent question — do the firms supported by business groups follow the same pattern and entry mode while going international in the form of FDI? This phenomenon can be examined in the context of both developed as well as developing countries. Further, we believe that a fruitful area of investigation is entry and establishment modes based research ( Dikova & Brouthers, 2016 ) at either the firm level or industry level, particularly for high-value, knowledge-intensive industries. Here, the emerging research on global value chain disaggregation (e.g., Mudambi & Puck, 2016 ) could benefit strongly from such an approach.

FDI research on outcomes has focused most often on firm-level financial performance and economic growth at the country level, but there are gaps in the extant literature. While FDI research on country-level outcomes is abundant in literature, research studies dealing with firm-level outcomes are not as many as the country-level studies. We believe that this provides a promising opportunity for future research. For example, Yang, Martins, and Driffield (2013) found a significant relationship between the breadth of a firm’s FDI and performance. They showed that the return on FDI over time in developing countries represents a U-shaped relationship, indicating that multinationals are likely to face losses in the early stage of their investment in developing countries before positive returns are realized. We suggest that researchers test the FDI–profit relationship hypothesis further with reference to wholly-owned subsidiaries and joint ventures and find evidence from different countries. While a substantial amount of research provides insights into antecedents and characteristics of acquisitions or greenfield FDI, the outcome of such investments at the firm and industry levels is very limited. Similarly, research on the outcomes of technology transfer for FDI intensity should be particularly fruitful.

It was found that the literature on MNE-FDI would benefit from a combined methodological and conceptual renewal. This implies the scope for developing new frameworks, paradigms, and theoretical models to explain different dimensions of MNE-FDI such as key motivates (antecedents), entry /and establishment mode decisions and characteristics or outcomes as suggested by Paul and Benito (2018) . There are immense possibilities to develop typologies for discussing one or more of the dimensions of FDI such as - Potential, Path, Process, Pace (ex, switching entry mode), Problems or/and Performance. Although the methods used in FDI research have grown to be more sophisticated, there are opportunities to develop integrative approaches by studying the antecedents, characteristics, and outcomes of FDI simultaneously. On the other hand, most studies build models in single countries only. It would be very useful if researchers conduct comparative analyses either for a group of countries or for two countries with similar or dissimilar features.

Empirically, there is a need for analyzing the impact of OFDI on performance at home. Here, propensity score matching that is similar to what was done by Hayakawa, Matsuura, Motohashi, and Obashi (2013) could provide interesting results. Such a novel approach would be valuable, as plenty of studies have already been published on FDI using multiple regressions with control variables. Recent advances in structural equation modelling techniques could also be deployed. Another important aspect is that researchers in this area should specify carefully the degree to which their insights are likely to generalize in different settings. One suggestion is to collect primary data from at least three firms/MNEs as there is less number of studies using such data, in comparison to the number of studies using secondary data. Nevertheless, it is important to understand that secondary data may provide useful benchmarks.

Additionally, there are opportunities for conducting research studies that address one or more of the issues and topics outlined below. Researchers may use the following as their research questions in their future studies using data.

What are the motives that drive the FDI of small, medium and large enterprises from emerging economies and what factors are involved in positive outcomes for these firms? Are there similarities in the decision characteristics of FDI, such as entry modes from emerging as well as developing countries? Do regulatory and cultural factors influence the path, process, and pace of FDI?

How do the micro and macro environments in both the home and host countries influence the MNEs from emerging economies? What are the challenges firms from countries such as China and India will face during the post-COVID-19 era?

What strategies (organic growth strategy such as greenfield investment versus inorganic growth strategy such as acquisition) are implemented by MNEs while going global? What are the paradigm shifts MNEs will undergo during the post-COVID-19 period, compared to the pre-COVID-19 period (till 2019)?

What are the problems and challenges faced by firms from emerging countries in Asia while going global? Would they confine to Predictable markets ( Paul & Sanchz-Morcillo, 2019 ) in the post-COVID-19 period?

5. Conclusion

The literature on MNE-FDI is quite substantial, though arguably heterogeneous, in nature. In an attempt to review 50 years of MNE-FDI research, we have provided a near-exhaustive catalog of the extant literature (See Tables 10 onwards given as online supplement ). We systematically reviewed 500+ journal articles, which as a whole can be considered representative of the present body of knowledge on MNE-FDI. The review summarizes past and contemporary FDI research in the context of developed as well as developing countries. Such a large-scale approach is justified, and necessary, as existing reviews have only provided subsets without integrating the overall body of research.

We identified the most commonly used theories, variables, statistical methods employed, home/host countries, and primary outlets for FDI research. We have also listed different approaches and variables used in FDI research to show their impacts on home/host countries. The most insightful and most-cited studies have developed either hypotheses or propositions about only one or two critical dimensions of FDI. These dimensions include antecedents, characteristics, and outcomes of FDI undertaken by MNEs. They also focus on the following aspects of FDI: FDI potential, path, process, pace, problems, and performance. Most authors of these most influential studies deployed advanced approaches to test hypotheses. However, the ever-greater availability of micro-level data should help future research move beyond our current state of knowledge.

Overall, we found that, despite the long history of FDI research, there has been a considerable rise in academic interest and publications since 2000. This validates the notion that globalization has increased not only in momentum but also in its characteristics during the last two decades. Thus, continued pursuit of FDI research could generate meaningful contributions to scholarship, practice, and policy.

From the point of view of scholarship, comparative research should identify new generalizable patterns across firms, industries, or countries: leading to the development of robust new theories. In practice, FDI research can provide better insights for decision-makers. For instance, research using firm-level data and information would help managers to make intelligent decisions on entry modes such as equity joint ventures or subsidiaries, or on formulating their strategic choice between greenfield investments or acquisitions. For policymakers, findings in new research at the country level and industry level may help in identifying the best and most appropriate policies in support of IFDI or OFDI, as well as how to cope with the increasingly difficult management of MNEs that are less home-country centric but truly transnational.

Acknowledgement

Authors are thankful to Professor Andreas Schotter, Ivey Business School, Canada. Alex Beamish, Ivey-Canada helped us in proof reading the manuscript. Comments and help from Jonathan Doh and Gurmeet Singh are also acknowledged.

Biographies

Dr Justin Paul serves as Editor-in-Chief, International Journal of Consumer Studies, (A Grade, Australian Business Deans Council) and a tenured full professor with the Graduate School of Business, University of Puerto Rico, PR, USA. He holds a title Distinguished Scholar, Indian Institute of Management (IIM-K), Kerala, He is known as an author/co-author of text books such as Business Environment (4th ed), International Marketing, Export-Import Management (2nd edition) by McGraw-Hill & Oxford University Press respectively. Over 100,000 copies of his books have been sold and his articles have been downloaded over 500,000 times. He has served as a full-time faculty member with premier institutions such as the University of Washington, Nagoya University, Japan and Rollins College-Florida. Dr. Paul has served as Senior/Guest/Associate Editor with the International Business Review , Journal of Retailing & Consumer Services, Small Bus Economics, European Management Journal, The Services Industries Journal and Journal of Strategic Marketing, Journal of Promotion Management & International Journal of Emerging Markets. In addition, he has taught full courses at Aarhus University- Denmark, Grenoble Eco le de Management-France, Universite De Versailles -France, ISM University-Lithuania, Warsaw School of Economics-Poland and has conducted research paper development workshops in countries such as Austria, USA, Croatia, China. He has been an invited speaker at several institutions such as University of Chicago, Fudan & UIBE-China, Barcelona and Madrid and has published over 50 research papers and bestselling case studies with Ivey & Harvard. Dr. Paul introduced Masstige model and Masstige Mean score scale as an alternative measure for brand equity measurement, CPP Model for internationalization of firms and 7-P Framework for Internationalization.

María M. Feliciano-Cestero has more than 15 years of work experience as a Mathematics Professor before joining for Ph.D. in Business Administration.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.04.017 .

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

- Agrawal G., Khan M.A. Impact of FDI on GDP: A comparative study of China and India. International Journal of Business and Management. 2011;6(10):71. [ Google Scholar ]

- Alfaro L., Chanda A., Kalemli S., Sayek S. FDI and economic growth: The role of local financial markets. Journal of International Economics. 2004;64(1):89–112. [ Google Scholar ]

- Alguacil M., Cuadros A., Orts V. Foreign direct investment, exports, and domestic performance in Mexico: A causality analysis. Economic Letters. 2002;77(1):371–376. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ali U., Shan W., Wang J.J., Amin A. Outward foreign direct investment and economic growth in China: Evidence from asymmetric ARDL approach. Journal of Business Economics and Management. 2018;19(5):706–721. [ Google Scholar ]

- Alvarez I., Marin R. FDI and technology as levering factors of competitiveness in developing countries. Journal of International Management. 2013;19(3):232–246. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ambos T.C., Ambos B., Schlegelmilch B.B. Learning from foreign subsidiaries: An empirical investigation of headquarters' benefits from reverse knowledge transfers. International Business Review. 2006;15(3):294–312. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ambos T., Asakawa C.K., Ambos B. A dynamic perspective on Subsidiary Autonomy. Global Strategy Journal. 2011;1(3–4):301–306. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ambos T.C., Birkinshaw J. Headquarters attention and its effect on subsidiary performance. Management International Review. 2010;50(4):449–469. [ Google Scholar ]

- Andersson U., Forsgren M., Holm U. The strategic impact of external networks: Subsidiary performance and competence development in the multinational corporation. Strategic Management Journal. 2002;23(11):979–996. [ Google Scholar ]

- Angresano J., Bo Z., Muhan Z. China’s rapid transformation: The role of FDI. Global Business and Economics Review. 2002;4(2):223–242. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anwar S., Nguyen L.P. Foreign direct investment and export spillovers: Evidence from Vietnam. International Business Review. 2011;20(2):177–193. [ Google Scholar ]

- Asiedu E., Jin Y., Nandwa B. Does foreign aid mitigate the adverse effect of expropriation risk on foreign direct investment? Journal of International Economics. 2009;78(2):268–275. [ Google Scholar ]

- Aurangzeb Z., Stengos T. The role of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in a dualistic growth framework: A smooth coefficient semi-parametric approach. Borsa Istanbul Review. 2014;14(3):133–144. [ Google Scholar ]

- Baharumshah A.Z., Thanoon M.A. Foreign capital flows and economic growth in East Asian countries. China Economic Review. 2006;17(1):70–83. [ Google Scholar ]

- Balasubramanyam V.N., Salisu M., Sapsford D. Foreign direct investment and growth in EP and IS countries. Economic Journal. 1996;106(1):92–105. [ Google Scholar ]

- Balasubramanyam V.N., Salisu M., Sapsford D. Foreign direct investment as an engine of growth. Journal of International Trade and Economic Development. 1999;8(1):27–40. [ Google Scholar ]

- Barkema H.G., Chen X.P., George G., Luo Y., Tsui A.S. West meets East: New concepts and theories. Academy of Management Journal. 2015;58(2):460–479. [ Google Scholar ]

- Barney J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management. 1991;17(1):99–120. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bausch A., Krist M. The effect of context-related moderators on the internationalization-performance relationship: Evidence from meta-analysis. Management International Review. 2007;47(3):319–347. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bergsten C.F., Horst T., Moran T. Brookings Institution; Washington, D.C.: 1978. American multinationals and American interests. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bhasin N., Paul J. Exports and outward FDI: Are they complements or substitutes? Evidence from Asia. Multinational Business Review. 2016 [ Google Scholar ]

- Bhaumik S.K., Driffield N. Direction of outward FDI of EMNEs: Evidence from the Indian pharmaceutical sector. Thunderbird International Business Review. 2011;53(5):615–628. [ Google Scholar ]

- Blonigen B.A. A review of the empirical determinants of FDI. Atlantic Economic Journal. 2005;33(1):383–403. [ Google Scholar ]

- Blonigen B.A., Piger J. Determinants of foreign direct investment. Canadian Journal of Economics. 2014;47(3):775–812. [ Google Scholar ]

- Boddewyn J.J. Foreign direct divestment theory: Is it the reverse of FDI theory? Review of World Economics. 1983;119(2):345–355. [ Google Scholar ]

- Borensztein E., Gregorio J.D., Lee J.W. How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth? Journal of International Economics. 1998;45(1):115–135. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brouthers K.D., Brouthers L.E. Why service and manufacturing entry mode choices differ: The influence of transaction cost factors, risk, and trust. Journal of Management Studies. 2003;40(5):1179–1204. [ Google Scholar ]

- Buckley P.J., Casson M.C. Vol. 1. Macmillan; London: 1976. (The future of the multinational enterprise). [ Google Scholar ]

- Buckley P.J., Casson M.C. The internalization theory of the multinational enterprise: A review of the progress and a research agenda after 30 years. Journal of International Business Studies. 2009;40(9):1563–1580. [ Google Scholar ]

- Buckley P.J., Clegg J., Wang C. Inward FDI and host country productivity: Evidence from China’s electronics industry. Transnational Corporations. 2006;15(1):13–37. [ Google Scholar ]

- Calvet A.L. A synthesis of FDI theories and theories of the multinational firm. Journal of International Business Studies. 1981;12(1):43–59. [ Google Scholar ]

- Canabal A., White G.O., III Entry mode research: Past and future. International Business Review. 2008;17(3):267–284. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cannon S., Summers L.H. How Uber and the sharing economy can win over regulators. Harvard Business Review. 2014;13(10):24–28. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chakraborty C., Basu P. Foreign direct investment and growth in India: A co-integration approach. Applied Economics. 2002;34(1):1061–1073. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chan C.M., Makino S., Isobe T. Interdependent behavior in foreign direct investment: The multi-level effects of prior entry and prior exit on foreign market entry. Journal of International Business Studies. 2006;37(5):642–665. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chari M.D. Business groups and foreign direct investments by developing country firms: An empirical test in India. Journal of World Business. 2013;48(3):349–359. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen S., Tan H. Region effects in the internationalization–performance relationship in Chinese firms. Journal of World Business. 2012;47(1):73–80. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cheng L.K., Kwan Y.K. What are the determinants of the location of foreign direct investment? The Chinese experience. Journal of International Economics. 2000;51(2):379–400. [ Google Scholar ]

- Child J. Strategic choice in the analysis of action, structure, organizations, and environment: Retrospect and prospect. Organization Studies. 1997;18(1):43–76. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chung C.C., Xiao S.S., Lee J.Y., Kang J. The interplay of top-down institutional pressures and bottom-up responses of transition economy firms on FDI entry mode choices. Management International Review. 2016;56(5):699–732. [ Google Scholar ]

- Contractor F.J., Dangol R., Nuruzzaman N., Raghunath S. How do country regulations and business environment impact foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows? International Business Review. 2019;29(2):101640. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cook G.A.S., Pandit N.R., Loof H., Johansson B. Geographic clustering and outward foreign direct investment. International Business Review. 2012;21(6):1112–1121. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cuervo-Cazurra A., Inkpen A., Musacchio A., Ramaswamy K. Governments as owners: State-owned multinational companies. Journal of International Business Studies. 2014;45(8):919–942. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cui L., Jiang F. Ownership decisions in Chinese outward FDI: An integrated conceptual framework and research agenda. Asian Business & Management. 2009;8(3):301–324. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cui L., Jiang F. State ownership effect on firms' FDI ownership decisions under institutional pressure: A study of Chinese outward-investing firms. Journal of International Business Studies. 2012;43(3):264–284. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cushman D.O. Real exchange rate risk, expectations, and the level of direct investment. Review of Economics and Statistics. 1985;67(2):297–308. [ Google Scholar ]

- De Mooij R.A., Ederveen S. Taxation and foreign direct investment: A synthesis of empirical research. International Tax and Public Finance. 2003;10(6):673–693. [ Google Scholar ]

- Delevic U., Heim I. Institutions in transition: Is the EU integration process relevant for inward FDI in transition European economies? Eurasian Journal of Economics and Finance. 2017;5(1):16–32. [ Google Scholar ]

- Delios A., Beamish P. Survival and profitability. The role of experience and intangible assets in foreign subsidiary performance. Academy of Management Journal. 2001;44(5):1028–1038. [ Google Scholar ]

- Demirbag M., Tatoglu E., Glaister K.W. Equity-based entry modes of emerging country multinationals: Lessons from Turkey. Journal of World Business. 2009;44(4):445–462. [ Google Scholar ]

- Deng P. Chinese outward direct investment research: Theoretical integration and recommendations. Management and Organization Review. 2013;9(3):573–1539. [ Google Scholar ]

- Desai M.A., Foley F., Hines J.R. Foreign direct investment and the domestic capital stock. American Economic Review. 2005;95(2):33–38. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dikova D. Performance of foreign subsidiaries: Does psychic distance matter? International Business Review. 2009;18(1):38–49. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dikova D., Brouthers K. International establishment mode choice: Past, present, and future. Management International Review. 2016;56(4):489–530. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dikova D., Sahib P.R. Is cultural distance a bane or a boon for cross-border acquisition performance? Journal of World Business. 2013;48(1):77–86. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dikova D., Van Witteloostuijn A. Foreign direct investment mode choice: Entry and establishment modes in transition economies. Journal of International Business Studies. 2007;38(6):1013–1033. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dritsaki M., Dritsaki C., Adamopoulos A. A causal relationship between trade, foreign direct investment and economic growth for Greece. American Journal of Applied Sciences. 2004;1(3):230–235. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dunning J.H. Toward an eclectic theory of international production: Some empirical tests. Journal of International Business Studies. 1980;11(1):9–31. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dunning J.H. Explaining the international direct investment position of countries: Towards a dynamic or developmental approach. Review of World Economics. 1981;117(1):30–64. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dunning J.H. The eclectic paradigm of international production: A restatement and some possible extensions. Journal of International Business Studies. 1988;19(1):1–31. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dunning J.H. Addison-Wesley; Wokingham: 1993. Multinational enterprises and the global economy. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dunning J.H. Location and the multinational enterprise: A neglected factor? Journal of International Business Studies. 1998;29(1):45–66. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dunning J.H. The eclectic paradigm as an envelope for economic and business theories of MNE activity. International Business Review. 2000;9(2):163–190. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dunning J.H. In: The Oxford handbook of international business. Rugman A., Brewer T.L., editors. Oxford University Press; New York: 2001. The key literature on IB activities: 1960–2000; pp. 36–68. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dunning J.H. European Union and the race for foreign direct investment in Europe. Journal of International Business Studies. 2006;37(1):569–571. [ Google Scholar ]

- Durham J.B. Absorptive capacity and the effects of foreign direct investment and equity foreign portfolio investment on economic growth. European Economic Review. 2004;48(2):285–306. [ Google Scholar ]

- Eisenhardt K.M. Agency- and institutional-theory explanations: The case of retail sales compensation. Academy of Management Journal. 1988;31(3):488–511. [ Google Scholar ]

- Enderwick P. Attracting “desirable” FDI: Theory and evidence. Transnational Corporations. 2005;14(5):93–119. [ Google Scholar ]

- Eryiğit M. The long-run relationship between foreign direct investments, exports, and gross domestic product: Panel data implications. Theoretical and Applied Economics. 2012;19(10):71–82. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fang Y., Wade M., Delios A., Beamish P.W. An exploration of multinational enterprise knowledge resources and foreign subsidiary performance. Journal of World Business. 2013;48(1):30–38. [ Google Scholar ]

- Feenstra R.C., Hanson G.H. Foreign direct investment and relative wages: Evidence from Mexico’s maquiladoras. Journal of International Economics. 1997;42(3):371–393. [ Google Scholar ]

- Feils D., Rahman M. The impact of regional integration on insider and outsider FDI. Management International Review. 2011;51(1):41–63. [ Google Scholar ]

- Feridun M., Sissoko Y. Impact of FDI on economic development: A causality analysis for Singapore, 1976–2002. International Journal of Economic Sciences & Applied Research. 2011;4(1) [ Google Scholar ]

- Fetscherin M., Voss H., Gugler P. 30 years of foreign direct investment to China: An interdisciplinary literature review. International Business Review. 2010;19(3):235–246. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fidrmuc J., Martin R. FDI, trade and growth in CESEE countries. Focus on European Economic Integration Q. 2011;1:70–113. [ Google Scholar ]

- Filatotchev I., Strange R., Piesse J., Lien Y. FDI by firms from newly industrialized economies in emerging markets: Corporate governance, entry mode, and location. Journal of International Business Studies. 2007;38(1):556–572. [ Google Scholar ]

- Findlay R. Relative backwardness, direct foreign investment, and the transfer of technology: A simple dynamic model. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1978;92(1):1–16. [ Google Scholar ]

- Franco C. Exports and FDI motivations: empirical evidence from US foreign subsidiaries. International Business Review. 2013;22(1):47–62. [ Google Scholar ]

- Galan J.I., Gonzalez-Benito J. Distinctive determinant factors of Spanish foreign direct investment in Latin America. Journal of World Business. 2006;41(2):171–189. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gao L., Liu X., Zou H. The role of human mobility in promoting Chinese outward FDI: A neglected factor? International Business Review. 2013;22(2):437–449. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gatignon H., Anderson E. The multinational corporation’s degree of control over foreign subsidiaries: An empirical test of a transaction cost explanation. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization. 1988;4(2):305–336. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gaur A.S., Ma X., Ding Z. Home country supportiveness/unfavorableness and outward foreign direct investment from China. Journal of International Business Studies. 2018;49(3):324–345. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ge G.L., Ding D.Z. China Rules. Palgrave Macmillan; London: 2009. The effects of the institutional environment on the internationalization of Chinese firms; pp. 46–68. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ghemawat P. Distance still matters. Harvard Business Review. 2001;79(8):137–147. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ghemawat P. Semiglobalization and international business strategy. Journal of International Business Studies. 2003;34(2):138–152. [ Google Scholar ]