Tovey’s Analyses

For many music scholars in the English-speaking world the writings of Donald Francis Tovey (1875–1940) remain a source of inspiration and insight. Tovey has something of interest to say about the majority of the most prominent composers in the tonal tradition, and his knack for finding metaphors to characterize salient musical events is widely acknowledged and celebrated. Though Tovey died over eighty years ago he remains, at some level, an intellectual presence in modern musicology, not least through later influential publications that have elaborated some of his ideas: Charles Rosen’s elucidation of the ‘classical style’, Joseph Kerman’s writings on the Beethoven string quartets, and James Webster’s analyses of sonata form in the music of Schubert and Brahms, to name but three. The term ‘purple patch’ as a means of describing chromatic passages within an otherwise stable diatonic context has become common parlance. Tovey’s critiques of textbook definitions, academic orthodoxies, and the ‘jelly-mould’ approach to musical form might still serve as useful provocations.

That Tovey is understood today predominantly as a music analyst is of course a testament to his achievements as a writer about music, but it also serves to construe his career in terms rather narrower than he himself might have recognized. The activity of analyzing music was clearly integral to Tovey’s existence: leafing through his personal scores that survive in the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Research Collections one senses that he was constitutionally unable to play, hear, or look at a piece of music without scribbling a few remarks about its aesthetic effect or the method of its construction. But Tovey was many other things as well as an analyst—a composer, a university professor, a conductor, and a highly regarded pianist who collaborated with leading musicians such as Joseph Joachim, Fritz and Adolf Busch, and Pablo Casals.

Tovey at his desk, photograph by Frederick Hollyer (ca 1900) University of Edinburgh Centre for Research Collections, CLX-A-359 (E.2001.37)

The reception of Tovey’s thought about music has been shaped in particular by the publication of his popular Essays in Musical Analysis by Oxford University Press in the late 1930s. Although the essays are most commonly read today in a university context, as has often been noted, their original function was to accompany concerts—and normally ones that featured Tovey himself as a performer. In these texts Tovey sought to guide an interested audience through familiar and new compositions and, as is clear from the work of Catherine Dale, Tovey’s essays can helpfully be situated in the tradition of analytical programme notes that became popular in Britain during the second half of the nineteenth century. Rather than being aimed at scholars, such writings contributed to the trend of what Christian Thorau has recently theorized as ‘touristic listening’—whereby audiences were led through a given work by an accompanying programme note that provided a sense of what ‘ought’ to be heard. While it was in writing about Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Brahms that Tovey contributed his most penetrating insights, the canon of works represented in these volumes is broader and more idiosyncratic than one might casually assume. Alongside such classics as Tovey’s analyses of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, Haydn’s Creation, and Brahms’s symphonies are essays on music by Weelkes, Wilbye and Palestrina, Sibelius, Röntgen, and Respighi, together with many of Tovey’s British contemporaries (Elgar, Holst, Smyth, and Vaughan Williams).

Despite the value of the Essays in Musical Analysis many of Tovey’s most significant scholarly contributions are to be found elsewhere, especially in texts gathered in the posthumous volume Essays and Lectures on Music . This includes his surveys of the chamber music of Haydn and Brahms, the essay on tonality in Schubert, and an article on Beethoven’s approach to musical form. Other notable publications are the analytical companion to the Art of Fugue and Tovey’s edition of this work (which contains his own hypothetical conclusion to Bach’s contrapuntal masterpiece), his précis of Beethoven’s piano sonatas, and an unfinished monograph on Beethoven that was issued in its fragmentary form by Oxford University Press in 1944. Tovey’s introductory notes for the individual preludes and fugues of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier appeared in an edition of the work published by the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music and were aimed first and foremost at performers, though they also contain a healthy seasoning of analytical observation. These short essays might be viewed as representative of the entanglement of Tovey’s varied musical interests: to be found here are aesthetic evaluations, source criticism, observations on historical keyboard instruments, and thoughts about Bach’s compositional technique.

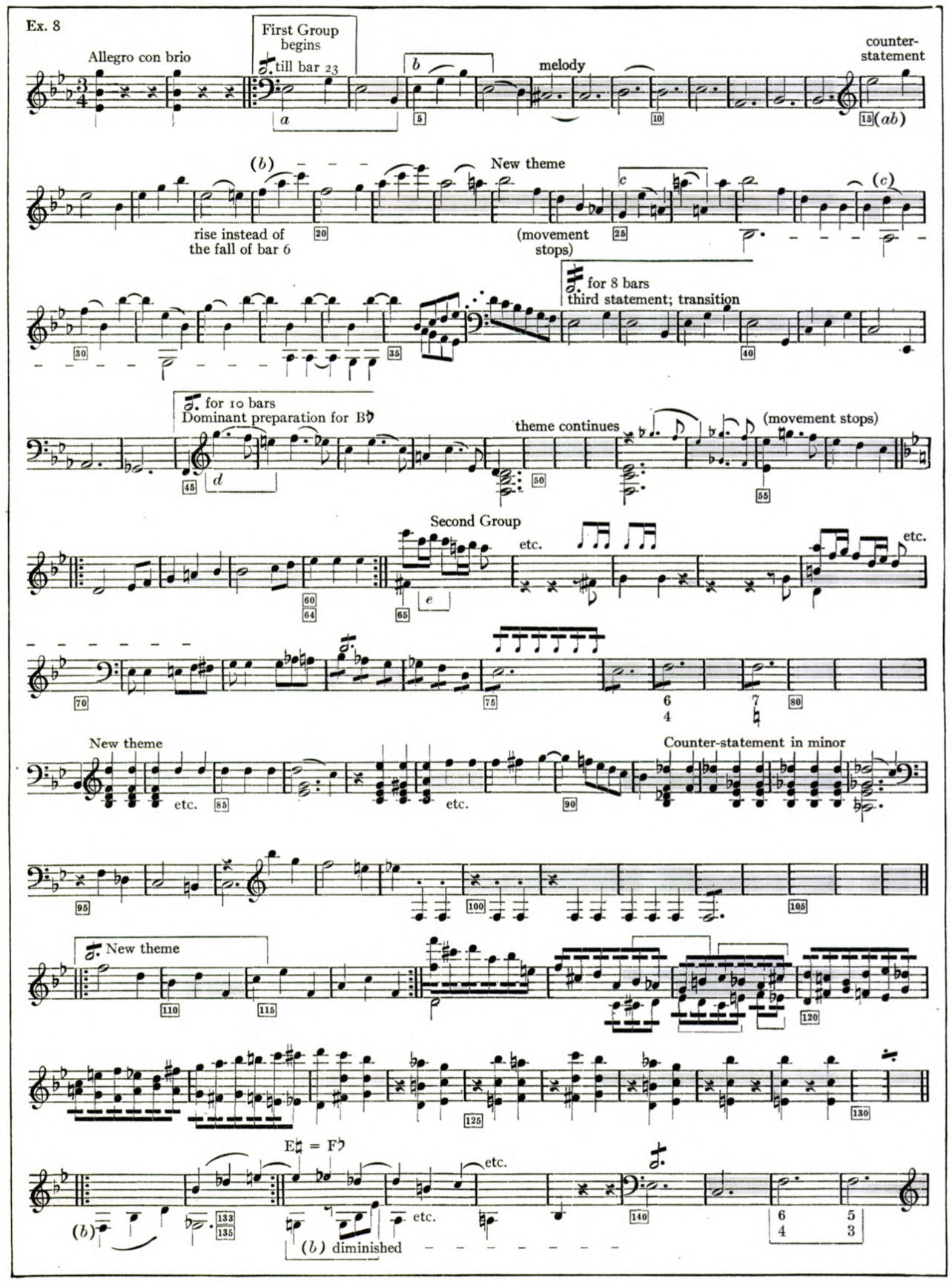

While Tovey is celebrated as one of the finest English-language writers about music it is worth noting that his gifts extended beyond being a prose stylist. In his companion to the Art of Fugue Tovey made good use of a system of symbols for fugal analysis that he adopted from Samuel Wesley and Charles Frederick Horn. To his frustration, the entries that Tovey contributed on musical subjects for the eleventh edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica appeared without musical examples. One of his planned, written out examples from Haydn’s Op. 9 quartets survives among his papers in Edinburgh and carries a characteristically acerbic annotation: ‘Intended for the Encyclopedia, but they won’t take musical illustrations; a pity, if you consider their treatment of Agriculture with full page photographs of prize sheep’. With the revised entries for the fourteenth edition Tovey had better luck and drew on a range of visually striking diagrams and concise musical illustrations. These are brilliantly chosen and exemplary for their communicative power. As observed by Scott Burnham, of particular note is the analytical reduction of the first movement of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony in Tovey’s entry on ‘sonata forms’. This gives a sense of the key events of the movement on a single musical staff (see example).

Extract from Tovey’s analytical reduction of the first movement of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony, ‘Sonata Forms’, Encyclopedia Britannica , 14th edition, vol. 20, 1929 p. 982.

Tovey might be felt as an awkward presence in the modern institutionalized world of music analysis and will no doubt puzzle some scholars through his bluster and seeming lack of interest in laying out new theoretical systems. There is nevertheless something instructive in Tovey’s example, both in terms of the depth of his knowledge about a treasured body musical works, and in his commitment to the idea that an interest in analytical engagement with music might be of fascination to a community of music lovers that extends beyond professional analysts.

Dr Reuben Phillips British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow Faculty of Music, University of Oxford

Tovey’s Writings

A Companion to ‘The Art of Fugue’ (London, 1931) A Companion to Beethoven’s Pianoforte Sonatas (London, 1931) Essays in Musical Analysis , 6 vols. (London, 1935–9) Essays in Musical Analysis: Chamber Music (London, 1944) Beethoven (London, 1944) Musical Articles from the Encyclopedia Britannica (London, 1944) Essays and Lectures on Music (US: The Main Stream of Music and other Essays ) (London, 1949) The Classics of Music: Talks, Essays, and other Writings previously uncollected , ed. Michael Tilmouth, David Kimbell and Roger Savage (Oxford, 2001)

Secondary Sources

Burnham, Scott. ‘Form.’ The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory , Thomas Christensen ed. Cambridge, 2002, pp. 880–906. Dale, Catherine. Music Analysis in Britain in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries . Aldershot, 2003. Kerman, Joseph. ‘Tovey’s Beethoven.’ Beethoven Studies 2, Alan Tyson ed. London, 1977, pp. 171–91. Monelle, Raymond. ‘Tovey’s Marginalia.’ The Musical Times 131 (1990), pp. 351–54. Rosen, Charles. The Classical Style . London, 1971. Spitzer, Michael. ‘Tovey’s Evolutionary Metaphors.’ Music Analysis 24 (2005), pp. 437–69. Thorau, Christian. ‘“What Ought to Be Heard”: Touristic Listening and the Guided Ear.’ The Oxford Handbook of Music Listening in the 19th and 20th Centuries , Christian Thorau and Hansjakob Ziemer ed. Oxford, 2019, pp. 207–27. Webster, James. ‘Schubert’s Sonata Form and Brahms’s First Maturity. 19th-Century Music 2, 3 (1978, 1979), pp. 18–35, 52–71.

Article Contents

A musical copernicus, reconciling the sonata structure, acknowledgement.

- < Previous

Tovey’s Idealism

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Craig Comen, Tovey’s Idealism, Music and Letters , Volume 100, Issue 1, February 2019, Pages 99–126, https://doi.org/10.1093/ml/gcy121

- Permissions Icon Permissions

While the writings of Donald Francis Tovey have been celebrated for their sensitive treatment of the music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, their methodology has evaded systematic reconstruction. This study argues that at the heart of Tovey’s critical oeuvre there lies a coherent framework, one indebted to the philosophy of German idealism. First, Tovey embeds himself in its aesthetic tradition by articulating a claim about what it means for music to be modern, most evident in his essay ‘Haydn’s Chamber Music’, where he presents the composer as responsible for initiating what he calls the ‘Copernican revolution’ of the ‘sonata style’. Second, Tovey’s analytical approaches rely on Hegelian dialectical thinking. A prime example is found in his early essay on Haydn’s E flat keyboard sonata, in which he elaborates his conception of the sonata style and presents a sophisticated method to analyse the music of Haydn and his successors.

Donald Francis Tovey begins his magisterial study ‘Haydn’s Chamber Music’ with an ambitious claim. He writes: ‘In the history of music no chapter is more important than that filled by the life-work of Joseph Haydn. He effected a revolution in musical thought … ’. 1 Tovey, commonly embraced for his arch-empiricist approach, as a paragon of British common sense, seems caught in a moment of flamboyance. Casting the weighty statement aside, he proceeds to discuss the age of Palestrina and then to outline the challenges of modern chamber music in the wake of the bygone continuo tradition. Still, a few pages later, the thought resurfaces: ‘Haydn’s life-work was to effect a Copernican revolution in musical form … ’. 2 It is a striking idea, for it harks back to Immanuel Kant, who famously claimed that his critical project accomplished a paradigm shift in philosophy equivalent to that of Copernicus in astronomy centuries before him. At first glance, Tovey’s claim makes no obvious sense, evoking one of the greatest modern philosophers in order to compare Haydn to a scientific discovery that transformed human history. Upon closer examination, however, the ideas behind Tovey’s claim wind up reaching to the core of his critical programme.

To read Tovey in any sort of systematic way admittedly requires patience. He frequently digresses, and he rarely summarizes himself once he gets back to the main path. His tone can be sarcastic, his references oblique, and his presentation revelling in contradiction. Tovey also draws on a diverse intellectual tradition. As Michael Spitzer has shown, he was exposed to a variety of influences from the late Victorian age, ranging from the art criticism of John Ruskin, Walter Pater, and Matthew Arnold to the post-Darwinian psychological writings of Herbert Spencer and William James, and even to the neo-Hegelian philosophical movement at Oxford. 3 Pulled in many directions, Tovey exhibits an array of competing intellectual commitments with a temperamental writing style to match. Spitzer holds: ‘ Although he wrote for the ordinary listener, the accessibility of Tovey’s writings is a myth.’ 4 Tovey, then, is at once inviting and opaque. Scholars have generally avoided excavating a deeper logic from beneath his characteristically jaunty demeanour and evocative descriptions, leaving his critical oeuvre—produced at a time when the boundary between specialized and popular audiences, for both music and writings on music, was not as clearly defined as it is today—to drift in a space between serious scholarship and scattered musings. 5

In this article I argue that at the basis of Tovey’s writings there is a systematic aspect indebted to the philosophy of German idealism. Often neglected in order to emphasize his empirical leanings, it nonetheless left a significant mark. Tovey’s claim of a Copernican turn constitutes a musical account of what it means to be modern in the aesthetic tradition formulated a century earlier. In ‘Haydn’s Chamber Music’, Tovey outlines a coherent theory of what would later be called the ‘Classical style’, or what he terms the ‘sonata style’, the musical embodiment of aesthetic modernity. Tovey bears the legacy of Hegelian thought with his claim that art is socially meaningful, built into his conception of the sonata style and its relation to convention. He is also indebted to dialectical thinking, a prime example of which is found in his early essay on Haydn’s Keyboard Sonata in E flat, H. XVI/52, which shapes both his ideas about the sonata style’s historical development and the analytical methods he employs for the music of Haydn and the composer’s successors. 6

In some ways Tovey requires little introduction. His writings were immensely popular among generations of music scholars and amateurs throughout the twentieth century. One of his most prominent champions was Joseph Kerman, who in 1978 confidently declared Tovey to be ‘brilliant, contentious, garrulous, sometimes elliptical, but also resolutely common-sensical, a sort of good-old-boy of music theory who has to be handled gingerly even now’. 7 In recent years, however, Tovey’s influence in the professional fields of musicology and music theory has waned, if not dissipated entirely. Occasionally, and no longer with the gingerly handling observed by Kerman, he bubbles up in contemporary scholarship to be portrayed as an analyst with obsolete tools, a gifted writer whose time has passed. 8 Yet if publisher reprints serve as any evidence, he retains a legion of admirers grateful for his poetic description in his Essays in Musical Analysis or his theoretical precision in his A Companion to Beethoven’s Pianoforte Sonatas . 9 And, while Tovey has received some recent attention as a figure of historical interest, his contribution to the discourse of musical thought—exemplified in his enduring analytical writings—has continued to elude our grasp. 10

Tovey’s narrative of Haydn as the initiator of the sonata style deserves to be taken seriously, as it reveals a foundational component of his critical programme. Tovey received his education at Oxford at the height of the intellectual movement of British idealism and developed his musical ideas in the light of his university training. If, in Spitzer’s words, ‘Tovey’s eclectic world-view was shaped by the cross-currents of British empiricism and German idealism in Victorian intellectual culture’, then it was his engagement with the latter that brings into focus his notions of musical style and analytical methods for the works of Haydn onwards. 11 His conception of modern musical form resonates with the aesthetic theories formulated by a group of German philosophers and literary critics around the turn of the nineteenth century, who provide intellectual context for Tovey’s dense and digressive essays on Haydn. 12 In addition, I consider passages from his other writings in order to clarify his arguments, and at a crucial moment I must pit Tovey against himself. What emerges in his project is a bold claim about the nature of the modern musical work and a sophisticated agenda for its analysis. To Tovey, the sonata style conveys its works to the listener as broken forms, each consisting of an assemblage of parts in a fraught relationship with an overarching whole, and his analytical methods ultimately aspire to reconcile the two.

Tovey’s affinity for Haydn has long been acknowledged, and scholars have given him much credit for his influence on the composer’s Anglophone reception. According to Brian Proksch: ‘Instead of crediting Tovey with initiating the Haydn revival, it would be more accurate to approach his writing as the culmination of earlier events, the final toppling of nineteenth century clichés and assumptions.’ 13 In the eyes of Rosemary Hughes, ‘Tovey had cut away the tangle of preconceptions about the tidy symmetry of Haydn’s forms’. 14 Lawrence Kramer goes as far as to claim that Tovey was primarily responsible for establishing the composer’s image as ‘the first to understand the very essence of modern musical logic, the Haydn who grasped the infinite possibilities of tonal, motivic, and contrapuntal development and found the techniques required to release them and bring them dramatically to life’. 15 Tovey has emerged as Haydn’s veritable English champion.

As for his intellectual world-view, Tovey is often represented as a no-nonsense empiricist, a bias exemplified by Kerman and one that has served to foil the abstruse and quasi-spiritual theoretical system of his German contemporary Heinrich Schenker. 16 Scholars have also historicized Tovey to uncover what lies beneath his critical agenda. For instance, Kramer places Tovey in his Victorian milieu in order to claim that the writer was predisposed to characterizing Haydn as ‘not bound by social constraint yet neither outside the social fabric nor hostile to it’, a composer who ‘challenges the pieties of order without fomenting disorder’ and above all the embodiment of ‘the creative genius as model citizen’. 17 While studies such as Kerman’s and Kramer’s have unearthed Tovey’s ideological assumptions, they occasionally lean on a portrayal of Tovey as a sharp intellect encumbered by a naive programme of democratizing classical music for the masses, an obsolete movement of social Darwinism, or other failed projects of the late Victorian age. 18 Helpful as they are for understanding Tovey’s environment, these accounts inevitably obscure the idealist foundations of his critical programme.

Essential to understanding Tovey’s intellectual framework is the conception of aesthetic modernity he explicates with his Copernican metaphor. Tovey’s reference descends from a famous remark by Kant, embedded in one of most influential, ambitious, and dense texts of the eighteenth century, the philosopher’s ground-breaking 1781 Critique of Pure Reason . The reference occurs in the preface to the second edition from 1787, where Kant famously claims:

Hitherto it has been assumed that all our knowledge must conform to objects. But all attempts to extend our knowledge of objects by establishing something in regard to them a priori , by means of concepts, have, on this assumption, ended in failure. We must therefore make trial whether we may not have more success in the tasks of metaphysics, if we suppose that objects must conform to our knowledge. This would agree better with what is desired, namely, that it should be possible to have knowledge of objects a priori , determining something in regard to them prior to their being given. We should then be proceeding precisely along the lines of Copernicus’ primary hypothesis. 19

As Henry Allison notes, Kant called his philosophical Copernican revolution a ‘change in the way of thinking’, constituting a challenge to the prevailing Enlightenment-era doctrine that cognitive thought is conditioned by worldly objects. 20 Instead he flips the terms around, leading to the Copernicus metaphor: just as the sun, and not the earth, was at the centre of the universe, then philosophy should consider objects themselves to be conditioned by thought. Kant’s system establishes, in Allison’s words, ‘the human mind as the source of the rules or conditions through which and under which it can alone represent to itself an objective world’. 21 With monumental aspirations, Kant fashioned his philosophical system as a turn away from the tenets of rationalist and empiricist philosophical discourse. 22

Fortuitously enough, eight years after ‘Haydn’s Chamber Music’, Tovey also speaks of a musical ‘Copernican revolution’. Of course, chronology does not necessarily help with substantiating Tovey’s thoughts. As Kerman notes, from the start of his academic career to the end, his essays differ little in style or tone, content, or quality, leading to a stark conclusion: ‘In dealing with Tovey, then, we are dealing with a mind that was entirely formed—that was made up—in the nineteenth century.’ 23 Even more bluntly, in an early review of The Main Stream of Music and referring to Tovey’s indifference to the music of his own time, Kerman writes, ‘Tovey effectively died as a critic in 1905’. 24 His essays also rarely build on each other, particularly since his preferred writing formats—programme notes, articles, and encyclopedia entries—restricted him to small-scale self-standing projects. Still, in his account ‘The Main Stream of Music’, while utilizing the metaphor of waterways to narrate the history of music, Tovey describes a turning point in the eighteenth century as such:

The tributaries which were drifting towards a confluence beside and above the deep current of Bach’s art united in a new stream which seems at first to be almost as incompatible with Bach as the music before Bach was incompatible with Palestrina. The result was indeed akin to what Kant would have called a Copernican revolution in the whole orientation of music …

Oddly, Tovey does not mention Haydn’s name. Instead, Mozart, Clementi, and Beethoven rise up as the agents who ‘assiduously pumped the whole contents of that dew-pond [of Domenico Scarlatti] into their own main stream’. 25 Tovey considers Haydn, alongside Mozart, a few paragraphs later; yet the idea that he singularly effected the revolution is notably absent.

Tovey’s reference to Kant nevertheless suggests an approach for understanding what he actually means by a musical Copernican turn. It is likely he was reaching back to his undergraduate studies at Oxford in the 1890s with Edward Caird, the Master of Balliol, a Scottish philosopher who specialized in the German idealist tradition of Kant and G. W. F. Hegel. 26 Caird and his contemporaries, particularly T. H. Green and F. H. Bradley, were the main contributors to the philosophical movement of British idealism in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Centred at Oxford, it was an intellectual tradition that emerged at a critical moment when the works of Kant and Hegel gained some traction in Britain in response to the native empiricist tradition of Jeremy Bentham and J. S. Mill, as well as the Scottish School of Common Sense initiated by Thomas Reid. The movement was predominant in the academy and, according to Anthony Quinton, ‘exercised its full intellectual authority in Britain in the three decades between 1874 and 1903’. 27 Tovey’s university training fell squarely within the most influential phase of British idealism at its institutional source.

In ‘Haydn’s Chamber Music’, extending the Copernican metaphor from philosophy to music, Tovey places Haydn in a position no less monumental than Kant claims for himself. 28 At stake in his comparison between Haydn and Bach is the development of the former’s ‘sonata style’ in response to the latter’s ‘architectural’ one. Tovey takes great pains here to differentiate the two styles, first clarifying the sonata style by what it is not: ‘But the development of Haydn’s sonata style is a matter neither of length nor of diversity of theme; and its dramatic tendency asserted itself in his earliest works.’ 29 Haydn’s sonata style, then, constitutes a Copernican turn because it is dramatic . Tovey writes elsewhere: ‘Now it is one of the first principles of sonata style that it is dominated by an active rather than by a passive sense of movement. All kinds of movement may, indeed must, be there, but sonata style is neither architectural nor cosmically epic, but thoroughly dramatic.’ 30 Tovey uses the word ‘drama’ across much of his critical output, yet it is usually only hazily defined. Within the context of recent scholarship that has clarified the role of agency in analytical discourse and traced its history, Tovey belongs to a long-standing tradition that continues to the present. According to Fred Maus: ‘The related notions of action behavior, intention, agent, and so on, figure in a scheme of explanation or interpretation that applies to human beings. … The scheme works by identifying certain events as actions and offering a distinctive kind of explanation for these events.’ 31 In a sense, Tovey adopts the practice of dramatic description exemplified by the programme notes of George Grove, among others, embracing evocative portrayals to render musical ‘events’ accessible to the average concertgoer. 32 Tovey invokes the metaphor of human action in order to make sense of musical structure, and in line with his own agenda he uses ‘drama’ to rationalize musical form as a coherent series of discrete elements that assemble into a convincing whole. Music’s drama is the glue that holds each structural element together within a work.

By comparing the first movement of Haydn’s String Quartet in B flat, Op. 1 No. 1, H. III/1, to the gigue finale of Bach’s Cello Suite No. 3 in C, BWV 1009, Tovey unveils his conception of a paradigm-shifting dramatic sonata style. Tovey tries to level the playing field, as it were, by choosing a Bach piece without a polyphonic texture and a Haydn piece without clearly defined thematic groups. 33 Of the quartet as a whole, Tovey states:

As to themes, it has either none, or as many as it has two-bar phrases, omitting repetitions; the second part contains no more development than the second part of Bach’s gigue; and though the substance that was in the dominant at the end of the first part is faithfully recapitulated in the tonic at the end of the second part, the formal effect is less enjoyable than in Bach’s gigue in proportion to the insignificance of the material.

Haydn’s movement appears to be little different in terms of thematic formulae or recapitulatory manoeuvres. If anything, Bach’s music is better crafted: ‘ Artistically Bach’s gigue is obviously of the highest order, while Haydn’s present effort is negligible.’ Tovey nonetheless sees the start of the first quartet of Haydn’s first publication as something revolutionary: ‘Yet within the first four bars Haydn shows that his work is of a new epoch.’ There is something fundamentally different about the two pieces. To Tovey, Bach’s gigue owes its construction to a particular set of constraints foreign to Haydn. He claims: ‘Its limits are those of an idealized dance tune, which actually does nothing which would throw a troupe of dancers out of step. Within such limits Bach’s art depends on the distinction of his melodic invention.’ 34 The work’s structure appears wholly governed by the conventions of a dance genre embedded within Bach’s own society.

The first few bars of the quartet do something else (see Ex. 1 ). According to Tovey, ‘to Haydn it is permissible to use the merest fanfare for his first theme, because his essential idea is to alternate the fanfare with a figure equally commonplace but of contrasted texture, throwing the four instruments at once into dialogue, p , after the f opening’. The material does not seem to be organized by the codes of, say, a Baroque dance, but instead arranges itself dramatically —it constitutes a series of phrases and techniques that seem to be arranged as a procession of actions, each incrementally contributing to the work’s grand narrative. Tovey describes the subsequent material at bars 9 ff. as such: ‘ As soon as it has made its point, other changes of texture appear; and the phrases, apart from their texture, soon show an irregularity which in these earliest works appears like an expression of class prejudice against the imperturbable aristocratic symmetry of older music.’ 35 Here Tovey echoes Matthew Arnold’s call for culture to dissolve class divisions: in the spirit of a modern proletarian’s anti-elitism, the sonata style repudiates the customs of music’s previous epoch and democratizes its structural elements. 36

Haydn, String Quartet in B flat, Op. 1 No. 1, H. III/1, mvt. 1, bb. 1–16

Tovey’s concerns about convention form the basis of his periodization of pre-modern Baroque and modern sonata music, an interpretative manoeuvre that tapped into a strand of aesthetic discourse which flourished over a century before him and which culminated in the philosophy of Hegel. 37 Following Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s idealization of ancient Greek art in his History of the Art of Antiquity of 1764, both Friedrich Schiller and Friedrich Schlegel wrote about the harmonious nature of pre-modern art and the instability of modern art, with Schiller calling his modern version ‘sentimental’ and Schlegel ‘romantic’. 38 Hegel himself labelled pre-modern art ‘classical’ and modern art ‘romantic’, a distinction that carried with it weighty social claims in his aesthetic theory. 39 To Hegel, art’s purpose was to be, not a beautiful abstraction, but instead an embodiment of the character of the social spheres of life. Classical art was harmonious as it was in an ancient world whose political institutions appeared secure, and romantic art was unstable as it was in a modern society whose subjects were alienated and whose social spheres were splintered. 40 Tovey’s shift from Baroque to sonata styles embodies the Hegelian shift from Classical to Romantic, and Hegel’s philosophy provides the sociological context to support Tovey’s claim about musical custom in Bach’s age versus that of Haydn.

If Tovey implicitly relies on Hegel’s social conditions for modern aesthetic convention, then he also follows their implications with regards to aesthetic form. In Hegel’s theory, with modern life came the modern burden of art to express the fractured world. Hegel again follows Schiller and Schlegel, each espousing a conception of the modern art work as a constellation of atomized techniques. For instance, in a series of letters to Gottfried Körner, Schiller writes: ‘ A form appears as free as soon as we are neither able nor inclined to search for its ground outside it. … A form is beautiful, one might say, if it demands no explanation, or if it explains itself without a concept.’ 41 The form’s features stood apart from each other and, according to Schiller: ‘Freedom comes about because each [technique] restricts its inner freedom such as to allow every other to express its freedom.’ 42 The features of a modern art work appeared self-determining, not beholden to any of their uses in earlier works—to tradition.

One of the most famous examples from German literary discourse is Schlegel’s call for ‘Romantic poetry’, a type of art that freely mixed different techniques and genres without recourse to prior conventions, held together instead by some higher spiritual thread. Recognizing these qualities in Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre of 1795, Schlegel claims:

This book is absolutely new and unique. We can learn to understand it only on its own terms. To judge it according to an idea of genre drawn from custom and belief, accidental experiences and arbitrary demands, is as if a child tried to clutch the stars and the moon in his hand and pack them in his satchel. 43

What makes art modern is its distance from conventions of the past—now the artist must experiment with them. Robert Pippin summarizes the point as it is presented in Hegel’s aesthetic theory:

The situation of the modern artist … has liberated the artist from the burden of any dependence on a received national or artistic tradition. There is nothing any longer in either sense that the artist is bound to take up, on pain of falling outside what is recognized as conforming to the norm, art. As Hegel says frequently … for the contemporary artist, anything from the past is available, any style, tradition, technique, any theme or topic. 44

Instead of depending on custom, the art work held itself together based on its own inner logic, a spiritual thread that had to be unearthed in order for the work to be fully appreciated.

The demands the early Romantics and the German idealists placed on the aesthetic domain were fashioned in response to a variety of social upheavals and intellectual crises of their time, all centred around the alienation of the subject at the turn of the nineteenth century and the apparent social irrelevance of art in everyday life. Hegel responded with a solution of sorts, articulating a homology between art forms and political ones, claiming that a fractured modern work mirrored a fractured world. As will be taken up in the next section, these concerns reappear transformed in the movement of British idealism and resonate with Tovey’s analytical methods. With his theorization of an aesthetic modernity, Tovey also contributes to a Hegelian tradition carried well into the twentieth century by Theodor Adorno, Martin Heidegger, and Georg Lukács, among others. 45 Returning to ‘Haydn’s Chamber Music’, Tovey’s scope is much narrower, and he is primarily interested in exploring the implications of a modern fractured musical form. Bach seemed bound to produce a gigue in a form faithful to the conventions of the dance, while Haydn instead floated above convention, free to play with musical materials and to juxtapose them in ways that exemplified their status as composerly fodder. Bach’s music was intimately tied to the social structures of dance, while Haydn’s music was itself a commentary on music. As such, Haydn constituted music’s modern turn away from convention and embraced modern artistic experimentation.

Tovey’s idea about the ‘dramatic fitness’ of the sonata style serves as his musically specific articulation that the modern art work must hold itself together by means of a logic unique to itself, by means of a dramatic form. Scholars have recognized Tovey’s notion of a modern musical work, as well as his predilection for claiming Haydn as its initiator. James Webster observes that Tovey’s view forms the basis of Charles Rosen’s own understanding of Haydn’s music as presented in his 1971 monograph, The Classical Style , wherein Rosen often sounds like he is parroting Tovey, such as when he states: ‘Haydn developed a style in which the most dramatic effects were essential to form—that is, justified the form and were justified (prepared and resolved) by it.’ 46 Webster claims that Rosen’s ‘modernist Haydn’ embraces ‘the autonomous character and self-generating procedures of high art’. 47 To show Tovey’s influence on Rosen, a writer who was rarely explicit about his intellectual forebears, Webster invokes a line from ‘Haydn’s Chamber Music’, where Tovey suggestively states: ‘[Haydn’s] art of composition is a general power which creates art-forms, not a routine derived from the practice of a priori schemes.’ 48 A work of Haydn’s was a unique, self-contained system.

Time and time again, Tovey shows interest in the idea of convention which serves to elaborate his conception of the sonata style. In his substantial essay ‘The Classical Concerto’, while presenting his ‘Concerto Principle’ concept, Tovey inserts a digression that clarifies his aesthetic views on convention. He writes:

The real meaning of ‘conventionality’ is either an almost technical, quite blameless, and profoundly interesting aesthetic fact, more often met with where art aspires beyond the bounds of human expression than elsewhere; or else the meaning is that a device has been used unintelligently and without definite purpose. And it makes not an atom of difference whether this use is early or late: thus the device of the canon is, more often than not, vilely conventional in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, and extremely beautiful wherever it occurs in Schumann and Brahms. So long as a thing remains the right thing in the right place, custom has simply nothing to do with it. 49

Here one needs to embrace Tovey’s musical Copernican turn—the moment of aesthetic modernity when art is no longer bound to custom—to understand the passage’s meaning. Everything for Tovey is retrospective. A conventional technique from early music, such as a canon, can conceivably be found in Schumann or Brahms, yet its modern usage cannot be explained simply by the fact that it is customary device. It must be ‘the right thing in the right place’. Echoing Schiller, Tovey claims here that only the work itself can authorize the canon’s seeming necessity, without any recourse to the idea that canons ought to be used in a certain way as established by all their prior uses. To Tovey’s ears, the canons of early music seem to be used so gratuitously that they now draw attention to themselves as a trite convention, whereas in Schumann and Brahms they compellingly arise out of the work as a ‘natural’ development. Said differently, Schumann and Brahms were now charged with incorporating a canon in such a way that an early music composer was not.

Returning to ‘Haydn’s Chamber Music’, when Tovey considers the irregular phrase structure of the finale of Haydn’s first quartet (see Ex. 2 ), he again demonstrates how convention is essential for an understanding of modern music. Haydn’s introductory six-bar phrase prompts Tovey to clarify that the music is decidedly not like the contemporary style of the Neapolitan school, which depended on a routine repetition of four- and two-bar phrases. Of the construction, he states: ‘It is a cliché for producing irregular rhythm without accepting the responsibility of making the music genuinely dramatic; and its presence in anything of Haydn’s is a mark of early date.’ 50 To Tovey’s ears, Haydn nonetheless manages to make the technique truly dramatic in the finale of Op. 1 No. 1:

Its six-bar opening would already sound irregular, even if it played out the sixth bar instead of stopping in the middle. And there is no intention of making this opening a pattern for the rest. The hearer’s sense of design must be satisfied with its return in the recapitulatory part of the movement, with all or most of the other bits of coloured glass in Haydn’s kaleidoscope; the only pattern and the only congruity lies in the whole. 51

Haydn does not make a conventional pattern out of the phrase structure—instead he deploys a number of different elements to convince the listener that such a structure belongs in the totality of the movement.

Haydn, String Quartet in B flat, Op. 1 No. 1, H. III/1, mvt. 4, bb. 1–17

Tovey’s conception of Haydn’s compositional style, as exemplified here, casts a very long but unacknowledged shadow. For example, Naomi Waltham-Smith has recently brought attention to an essay of Alain Badiou, the twentieth-century philosopher of French deconstruction, that characterizes Haydn as a musical revolutionary. At the beginning of Op. 33 No. 5, H. III/41, Waltham-Smith writes: ‘Haydn must first assemble the elements of the first two measures under the concept of the opening gesture and then count those same elements again as a closing gesture. By staging this appropriating “count”, this moment shows that musical material may or may not belong to a given situation.’ In terms of Badiou’s philosophy, she remarks, ‘The Haydn-event consists here, via the separation of material and use, in music’s subtraction from the necessity of belonging. Musical belonging reveals its contingency.’ 52 While Waltham-Smith accounts for Badiou’s indebtedness to Rosen’s The Classical Style , all rely on a conception of Haydn initially outlined by Tovey. His sonata style effectively describes the moment when music’s ‘materials’ and ‘use’ are no longer united, when the composer is now free from or, from another perspective, burdened with assembling musical materials bereft of their former regulative authority. Tovey’s Haydn faced an innumerable amount of options for the deployment of a technique, and its compellingly dramatic presence was entirely contingent upon its function within the unique totality of a work.

Tovey’s perspective on the sonata style also resonates with recently developed analytical methods in the field of eighteenth-century music. Highlighting the education of galant court composers through partimenti —manuals that supplied conventional bass-line patterns to be realized—schema theory holds that much of the music of Haydn’s time by lesser-known mid-century court composers was essentially modular in structure. Pre-existing models of a few bars in length became essential building blocks for everyday compositional practice. According to Robert Gjerdingen: ‘ A hallmark of the galant style was a particular repertory of stock musical phrases employed in conventional sequences.’ 53 Gjerdingen shows that even Haydn is indebted to the schemata tradition, tracing the composer’s unique spin on several galant schema archetypes as well as their deployments. 54 Topic theory also offers another perspective for understanding the structure of Haydn’s style, revealing a profoundly cultural element to his instrumental music. The theory shows many passages of Haydn and Mozart to be an interplay of socially meaningful musical markers, such as dances, marches, and horn calls, which index class, civic venue, or militaristic conquest, among other things, calling attention to the influence of the opera buffa tradition in the composers’ instrumental compositions. 55 As Danuta Mirka notes, topics are ‘musical styles taken out of their proper context and used in another one’, and so topic theory presupposes a divide between how a ‘style’ was conventionally used and how the group of generic markers had the potential to be abstracted and placed in a passage of a sonata or symphony. 56 From a Toveyan perspective, schemata and topics constitute part of Haydn’s toolbox of musical techniques, ready at hand for the composer to drop into a work.

Tovey takes pains to argue that Haydn’s Copernican turn was not fully accomplished in the composer’s earliest works. After outlining some elements of the first and last movements of the first quartet, he states: ‘In virtue of this it is still felt that the dramatic style has not exceeded the limits of melodic form; the listener has merely enjoyed a certain bulk of lyric melody distributed in witty dialogue and stated more in terms of fiddles and fingers than of song.’ 57 Tovey is typically reticent about which other elements from Haydn's earlier works, besides melody, would lead to a fully mature sonata style, but there is little doubt which point in the composer’s career Tovey sees as the moment when all the stars align. As scholars have recognized, he claims the Op. 20 quartets to be ‘a sunrise over the domain of sonata style as well as of quartets in particular’. While others like Rosen have claimed Op. 33 as the moment of Haydn’s maturity and the fruition of the Classical style, Tovey’s Copernican turn occurred with the publication of the 1772 Op. 20 string quartet cycle. 58 Tovey follows his celestial metaphor with an effusive explanation: ‘Every page of the six quartets of op. 20 is of historic and aesthetic importance; and though the total results still leave Haydn with a long road to travel, there is perhaps no single or sextuple opus in the history of instrumental music which has achieved so much or achieved it so quietly.’ 59 According to Tovey, the rest of the composer’s oeuvre served merely to elaborate the new style: ‘With op. 20 the historical development of Haydn’s quartets reaches its goal; and further progress is not progress in any historical sense, but simply the difference between one masterpiece and the next.’ 60

Tovey was not the first to claim Haydn’s career constituted the dawn of a new musical age. A century before, music critics were already periodizing what they saw as new music and declaring Haydn as a transitional figure. 61 As Leon Botstein shows, throughout the nineteenth century, Haydn was often claimed to be the founder of a new musical idiom, but typically marginalized as a predecessor or a ‘father’ of a style that Mozart and Beethoven would subsequently master, less so a figure of intrinsic interest. Botstein claims: ‘Haydn was an example of how historical necessity worked through an individual. He emancipated musical art from tradition and authority.’ 62 Furthermore, as Webster observes, traditional musicological portrayals of the composer stress a narrative beginning with an ‘immaturity’ that eventually transitions to a full-fledged mastery of the craft. 63 What Tovey establishes, in the face of tradition, is the idea that Haydn’s compositions are stand-alone works, analysable on their own terms. He has a rigorous impulse to trace the components of the sonata style directly within Haydn’s music, delving right into the score to show that the first notes of Haydn’s first publication are essentially modern, to demonstrate their dramatic fitness, and to reveal their profoundly experimental nature. He aims to show that Haydn’s works are not merely documents to shed light on Mozart’s and Beethoven’s accomplishments, but as entities worthy of careful analysis in and of themselves.

While ‘Haydn’s Chamber Music’ touches on the tenets of the modern dramatic sonata style, it only hints at how the style manifests in a work as a whole, rarely probing more than a few bars of a movement. Tovey’s essay on Haydn’s Keyboard Sonata in E flat, H. XVI/52, offers his most comprehensive attempt at explicating the foundations of the sonata style by means of analysing a movement (and indeed a work) in its entirety. It was written in 1900, a few decades prior to ‘Haydn’s Chamber Music’. Tovey was in a different stage of his life, fresh out of Oxford and touring as a concert pianist. In a bold stroke, he provided his audiences with extended essays on the works he was to perform. As Michael Tilmouth notes, ‘These were written for his London recitals of 1900–1 and published for him (“on a soft, rough paper that turns noiselessly”) by Joseph Williams. The intention was that they should be read prior to the concert, having been published about a week beforehand—a provision that was rarely met.’ 64 Following in the footsteps of Grove, Joseph Bennett, and George Macfarren, among others, Tovey embraced programme notes for his recitals with an extensive number of music examples, a feature he would embrace for the ones published decades later, collectively known today as his Essays in Musical Analysis . 65

There is scant evidence that Tovey developed his conceptual framework for criticism or analysis later in life, leading to Kerman’s claim that Tovey was firmly set in his Victorian ways. His earliest writings around 1900, particularly those represented in his Chamber Music: Essays in Musical Analysis and selections in The Classics of Music: Talks, Essays, and Other Writings Previously Uncollected , show Tovey at his most philosophically inclined and ambitious. Perhaps his intellectual aspirations from just a few years before were fresh in his mind. According to Tilmouth: ‘In the 1890s [Tovey] conceived a plan to write The Language of Music , a mighty treatise to end all treatises; and it was the early stages of his work on this that provided him with a systematic philosophical base which was to underlie all his later writings.’ His performance career subsequently blossomed, however, and his intellectual ambitions were side-tracked, in a pattern familiar for the rest of his life: ‘By the spring of 1899 the treatise had acquired a Book II and was “tumbling slowly into shape and terseness”; but the huge essays associated with his London concerts in 1900 intervened.’ 66 Tovey’s ‘huge essays’ from the early 1900s might in fact best be seen as applications or syntheses of his musical aesthetic theory project hatched during his undergraduate training, before his career as a pianist or as professor and conductor at the University of Edinburgh. 67

Tovey is at his most dialectical in these writings as well, which Spitzer recognizes as exhibiting a ‘Hegelian circularity’ and which Tovey himself casually references in an aside in a late broadcast talk entitled ‘Music and the Ordinary Listener’. He states:

When your arguments not only depend upon each other but comprise the universe, it is perfectly legitimate to argue in the circle that they depend upon each other because they make up the uniformity of nature, and that they prove the uniformity of nature because they all depend upon each other. This I learned taking essays to the Master of Balliol in 1896. 68

Here Tovey exemplifies his own Hegelian leanings as he fondly recalls his university training from decades before with Caird, a consummate Hegelian and central figure of the British idealism movement. 69 While Spitzer characterizes Tovey’s intellectual outlook as a negotiation between idealist and empiricist tendencies, his early essays are more indebted to the former than the latter. 70 In addition, taken literally, Tovey’s occasional ‘positivist’ claims—such as ‘The whole thing will explain itself, and we have nothing to do but to get accustomed to the style’ or ‘I have not yet tried to define tonality any more than I have attempted to define the taste of a peach’—fly in the face of the pages and pages he dedicates to explaining the inner structure of countless musical works or defining a theory of tonality in the music of Beethoven and Schubert, among others. 71 Brought into contact with German intellectual life a century prior, these outbursts are paradigmatic of Romantic irony, acknowledging the need to construct a totalizing philosophical system while simultaneously recognizing the impossibility of its attainment. 72

While Tovey’s account of dialectics is not the most descriptive, Hegel’s characteristic method is notoriously difficult to define. It challenges the classic philosophical approach to reduce concepts into their simplest unproblematic forms, to elemental first principles. Adorno—a perennial Hegel commentator who published a series of studies on the elder philosopher—summarizes: ‘Hegel shows that the fundamental ontological contents that traditional philosophy hoped to distill are not ideas discretely set off from one another; rather, each of them requires its opposite, and the relationship of all of them to one another is one of process.’ 73 Even in its ‘simplest’ form, a concept cannot be abstracted from the realm of action or removed from its social or historical context: it occupies a practical space of conflict and contradiction, dependent on a web of ideas surrounding it. Even a negation of an idea becomes something fundamentally constitutive of that idea. Hegel writes:

Negation is equally positive … what is self-contradictory does not resolve itself into a nullity, into abstract nothingness, but essentially only into the negation of its particular content … the result, the negation, is determinate negation, it has a content . It is a new concept but one higher and richer than the preceding—richer because it negates or opposes the preceding and therefore contains it, and it contains even more than that, for it is the unity of itself and its opposite. 74

An idea with its contradiction does not wipe the slate clean, as it were. Instead the interaction of the two can form the basis of a higher conception of reality that incorporates the conditions for the possibility of both. Dialectics offers a way, a process, to move beyond a strict dichotomy. 75 In Tovey’s analysis of Haydn’s E flat sonata, the problem that will plague him most of all—one which he will approach dialectically—is the dichotomy well known to any idealist, that of particular and universal, or part and whole.

In the shadow of the abandoned The Language of Music project, Tovey’s essay on Haydn’s E flat sonata presents a method for performing music analysis, addressing difficult questions about the nature of the sonata style and supplementing Tovey’s agenda to grasp the structure of modern music. The original title for the essay, ‘ A Great Sonata, by Haydn: and its Bearing on Modern Criticism’, hints at Tovey’s ambitions. 76 He initially approaches the movement by recognizing three distinct thematic units at the start (see Ex. 3 ), spending some time on the first one (bb. 1–2) to explain its significance in pianistic terms: ‘the heavy opening chords imply something unusually grand and broad’. 77 While his consideration for the conventions of piano technique initially seems like a typical Toveyan digression, it will eventually return in a significant way. Next Tovey explains that the second idea (bb. 3–4) grows from the first, ‘which, after repetition, descends in a long scale down to a third idea, a broad cantabile phrase on an easily swinging accompaniment’. Tovey hears each idea as a discrete building block, collectively establishing the material for the rest of the movement. Back to the local level, Tovey considers the material that follows: ‘Having stated these three independent items, Haydn welds them together by a counterstatement.’ 78 And so the introductory bits no longer sound very bit-like, leaving Tovey to claim this effect is akin to beginning the sonata in medias res . To a modern analyst attuned to the discourse of topic theory, Haydn’s opening bars might evoke the grand introductory gestures of a French overture, albeit sped up. Yet to Tovey’s ears, things unfold all too rapidly to settle into an initial groove: the listener is already thrown into the business of balancing phrases, immediately receiving dramatic context for the material at the start. The music refuses to begin in the manner of a beginning.

Haydn, Keyboard Sonata in E flat, H. XVI/52, mvt. 1, bb. 1–13

Next Tovey clarifies that Haydn’s style is less concerned with spinning out a gorgeous, singable melody (in the forgettable style of Spohr or Hummel, he snarkily adds) than with juxtaposing contrasting elements. The discussion foreshadows Tovey’s treatment of the first bars of Haydn’s first published string quartet a few decades later in ‘Haydn’s Chamber Music’, where he claims that the composer plays around with seemingly atomized technical elements. When Haydn does have use for ‘broad melodies’, however, Tovey explains that their necessity lies not in their intrinsic beauty, but rather in their dramatic context: ‘their position makes them more telling than even their obvious breadth and simplicity would lead one to conceive possible’. 79 Floating above convention, Haydn utilizes broad melodies in order to call attention to their very breadth.

To conclude the counterstatement, Haydn writes in a rapidly descending scale in bars 9–10. This presents an immediate challenge to Tovey, ever committed to showing that all of Haydn’s techniques belong not because of their conventional status, but because they are at home in the work’s dramatic narrative. He writes:

It is necessary for the organization of quick movements in terms of this classical art, that there should be as much contrast in rhythmic motion as can be managed without radical changes of time. Hence brilliant running passages are certain to occur as essential parts of the design, and it becomes an interesting problem in criticism to distinguish the cases where such passages are conventional or diffuse from those where they are really mature and natural; for their outward appearance and their turns of phrase are in all cases alike. Here Haydn has settled the question at once by this impulsive descending scale, thrown in with an apparent recklessness that gives a new and youthful aspect to his dignified theme. But from this moment onwards every demisemiquaver passage will inevitably appear to have originated in this incident. 80

The scale is ‘impulsive’, serving a function that changes the listener’s conception of the thematic structure thus far. It appears necessary because Tovey sees it as connecting to what came before it and ultimately imbuing the totality with its own characteristic recklessness. Echoing Tovey, Rosen also recognizes that Haydn and Mozart deploy conventional material or ‘filling’—particularly arpeggios and scales—in a way that it appears both pre-fabricated and belonging to a given work, ultimately serving to amplify the force of cadences and, by extension, key areas. 81 Haydn’s rapidly descending scale here exemplifies Rosen’s claim, leading to an emphatic low E♭ that fortifies the tonic right before the transition begins.

Tovey subsequently recognizes that Haydn continues his ‘counterstatement’ with an inversion of the material in bars 6–7 in a higher octave at bars 10 ff., leading yet again to a substantial aside, this time about texture’s role in the formation of the sonata style. According to Tovey: ‘The forms of the classical sonata are not prima facie contrapuntal, like the forms in which Bach wrote; indeed a study of the transition from Bach’s art to the maturity of Haydn and Mozart shows that in its early stages modern musical form was almost incompatible with counterpoint.’ After music was shorn of the customs which provided Bach with his compositional rationale, it could not appropriate counterpoint very easily since, on the one hand, the rules of voice-leading appeared beholden to tradition and not dramatic in themselves and, on the other, the punctuated periodic structure essential to the sonata style did not readily accommodate the continuous voice-leading on which counterpoint predicates itself. It was only Haydn and Mozart’s experimentation that led the sonata style to ‘a steady progress in inner contrapuntal life together with extremely sharply cut form’. 82 From the start, then, the sonata style unfolded historically as a process of assimilating disparate elements.

As he often does elsewhere, Tovey presents an ambitious thesis on a tangential topic over the course of a few paragraphs, never to return to the point again. Here he hints at a story of polyphony’s gradual reincorporation into the sonata style after music’s Copernican turn. Next Tovey brings instrumental style back into his narrative: ‘In the case of pianoforte solos the antithesis between counterpoint and form evidently gave Mozart and Haydn great trouble, since in their time the most obvious capabilities of the pianoforte were such as to distract the composer’s and listener’s attention from all polyphonic texture and even from ordinary clear part-writing.’ With the advent of the sonata style composers were faced with an antithesis between form and counterpoint, particularly with keyboard works, as the hammered, quickly decaying notes were not conducive to voice-leading. As well, there was a struggle between constructing a dramatic series of actions that exploited music’s distancing from convention and the techniques of fugal writing that were predicated on those very conventions. In line with his agenda to raise Haydn at the expense of his lesser-known contemporaries, Tovey reaches to Clementi as an instructive counter-example, claiming that the composer unconvincingly resolved this antithesis merely by inserting contrapuntal sections into his sonatas ‘as a matter of duty’, without any dramatic basis whatsoever, leading him to state: ‘they always disorganize his form, and sound thin without successfully contrasting with his normal weightier pianoforte-writing’. 83 To Tovey, Clementi’s canonic passages do indeed contrast with his typical sonata style, yet not in a compelling way—they stick out as something undramatic, not arising out of the work itself, but rather as moments that amount to little more than pedagogical exercises.

Finally Tovey returns to Haydn’s sonata with a grand summation of his solution to the problem of the antithesis between form and counterpoint in the sonata style: ‘Here form, counterpoint, and pianoforte style are one. The form already solves the contrapuntal part of the problem, because the phrases are so short that there is no time for a simple accompaniment to pall.’ Haydn’s quick succession of different pianistic textures and thematic materials prevents the threat of a stale accompaniment that would call attention to a humdrum homophonic texture. Tovey continues:

In the same way the form, by thus determining what shall be acceptable as accompaniment and inner parts, solves all difficulties as to pianoforte style. We might equally well argue conversely; the pianoforte style and the organization of the inner parts might be said to determine the form. Aesthetically, in the highest art, such as we have here, nothing is logically prior to anything else; the parts determine the whole no less than the whole determines the parts. Technically and historically, no doubt this is not so; in Haydn’s case the problem … was to make his form determine his texture; just as in Bach’s case it would have been exactly the converse. 84

This is a particularly weighty passage unceremoniously inserted in an ambitious essay masquerading as programme notes. It presents the dialectical core of Tovey’s analytical method, complete with a pithy summation at the end that obscures more than clarifies.

At the start of the passage, tracing Haydn’s work moment to moment, Tovey warns against the analytical trap of overdetermination from the three perspectives he has chosen for his analysis, what I term regulative analytical domains . The form—by which he means here the thematic content and periodic structure—might help to explain why a passage belongs where it does, but such an explanation cannot lord over the passage, lest the passage become a cog in the mechanistic system of phrase-balancing without any sort of appeal by itself. Also, the techniques idiomatic of piano writing may help to explain the style of a passage, but they cannot be the sole reason for its inclusion, lest the passage merely become an étude. Finally, textural contrast might explain Haydn’s twist at a particular moment, but if the passage were solely written in order to carry out a contrapuntal invention, then the moment of interest owes nothing except to the rules of counterpoint. The regulative analytical domains of form, instrumental technique, and texture each provide explanatory power for elucidating the relationship between a specific part of a work and the whole, but none offers a satisfactory explanation by itself. 85

Tovey concludes the paragraph by presenting a form–texture dichotomy that, coincidentally, offers an attractive synthesis of the musical Copernican turn: Bach’s texture legislated his form while Haydn inverts their relationship, with his form legislating his texture. Yet this is confounding, since Tovey has just made the point that form and texture are both distinct domains for providing explanatory support for a passage of a Haydn composition and that each is fundamentally antagonistic to the other—they stand in dialectical tension. Neither domain can solely legislate the relationship between a work’s parts and whole. A more accurate summation would be that Tovey’s musical Copernican turn constitutes the splintering of these domains. In Bach’s works, there was no meaningful distinction between texture and form, as writing in strict counterpoint also meant writing a compelling melodic progression. In Haydn’s case, texture could not generate form because the melodic content could not be held together by the rules of counterpoint; instead musical bits were juxtaposed dramatically , without recourse to convention. Approaching the problem from the other side, form cannot generate texture or else any moment of textural interest within a work would merely be in the service of thematic events—accompaniments would indeed ‘pall’. Any part of a work whose inclusion can be explained within a certain domain must have a residual component that reveals it to hold some appeal by itself.

It would also be a mistake to claim that Tovey is merely calling for a catholic or ‘multivalent’ approach to analysis. In the process of considering each of his regulative analytical domains for a particular bit, Tovey presents a fraught relationship between part and whole that he addresses both in the passage quoted above and indirectly throughout the essay. In the telling example concerning bars 9–10, Tovey intends to reconcile the function of the ‘impulsive’ descending scalar run in Haydn’s counterstatement within the totality of the work. He places its ‘recklessness’ in the dramatic unfolding of the whole, inserting it within a series of actions in the domain of form in order to figure out how it seems to belong. In other words, he provides context for the passage. But this critical manoeuvre in turn threatens the autonomy of the passage itself. There must be an equal and opposite critical manoeuvre, one that instead submits the whole to the part. Tovey attempts this when he claims that the passage alters the dignity of the theme and imbues the entire work with a youthful element. On a fundamental level, Tovey’s epigram ‘Nothing is logically prior to anything else’ means that there must be a relationship of equality between part and whole, whereby the two acknowledge each other without total domination or submission. Tovey attempts to carve a space for the sonic immediacy of the part, avoiding the characterization of a legislating whole, aspiring to an understanding of the work that reaches a balance between the two.

Tovey’s relationship of equality between part and whole represents a middle-road response to other contemporary approaches to musical form that privileged one over the other. One of the most prominent calls to the musical surface—to the privileging of parts—comes from Edmund Gurney, whose 1880 study The Power of Sound outlines a conceptualization of form that stresses the immediacy of the moment. Exemplifying this agenda, Gurney defines unity in two ways: ‘that which is involved in the arrangement of independently impressive or expressive parts, and that which is involved in each of these parts on its own account’. 86 The work’s comprehensibility must occur on the local level. Describing Gurney’s world-view, Jerrold Levinson notes: ‘The value of a piece … is solely a function of the satisfyingness, to the purely intuitive musical faculty, of its individual bits and the cogency of sequence at transitions between bits.’ 87 From the other side, Hubert Parry focuses more on the forest than the trees. At the start of his influential ‘Form’ entry in the first edition of Grove’s A Dictionary of Music and Musicians from 1879, Parry embraces the totality of form, claiming ‘the whole must be so contrived that the impression upon the most cultivated hearer shall be one of unity and consistency’. The part becomes a pawn, if it is even considered at all: ‘But in instrumental music there has been a steady and perceptible growth of certain fundamental principles by a process that is wonderfully like evolution, from the simplest couplings of repeated ideas by a short link of some sort, up to the complex but consistent completeness of the great instrumental works of Beethoven.’ 88 In Tovey’s system, such privileging risked an overreliance on fragmentation or totalization, and his analytical methods instead attempt to account for both Gurney’s trees and Parry’s forest.

Tovey’s balancing act of reconciling part and whole—a concern central to German idealism—resonated with the figures of British idealism, and his ambition to have a harmonious reconciliation of the two in a musical form mirrors what the leaders of the movement aspired for in modern society between individual and state. As Sandra M. den Otter observes, the British idealists tapped into the widespread preoccupation with ‘community’ in late nineteenth-century Victorian England, one emerging in response to anxieties about social disorder and fragility from urbanization, industrialization, and their discontents. To Henry George, ‘Not merely have destructive powers vastly increased, but the whole social organisation has become vastly more delicate. … . Let jar or shock dislocate the complex and delicate organisation … and the fountains of the great deep are opened, and quicker than ever before chaos comes again.’ 89 Many who were concerned with the instability of modern life sought solutions in the form of social reintegration. As den Otter writes: ‘ Attempts to restore the attachments of community characterized fin de siècle social and political debate.’ In the discourse of philosophy specifically, British idealists became increasingly dissatisfied with the predominant political theories of Mill, rejecting his conception of the modern subject as splintered from the world, alienated from the social totality, and they ultimately found it antagonistic towards a sustainable way of living. There was an urgency in their quest to achieve a semblance of legitimately communal relations, one that inevitably ran into challenges. According to den Otter: ‘They sought to ensure the unity, connection, and integration of the modern social organism. But idealist attempts to restore community were fraught with many of the difficulties which still accompany communitarian challenges.’ 90 In essence, the British idealists aspired to mend fundamental fissures they saw endemic to a modern industrial society.

Fashioned in response to similar social concerns, Hegel’s system offered a solution or, at least, presented the atomization of the subject as a fundamental problem of modern life to be solved. And while Kant served as a spiritual ancestor of British idealism, the movement itself was essentially Hegelian. 91 One of the major goals of Hegel’s philosophical system, as scholars today often recognize, was to reconcile the autonomous modern subject with society, to bring about an authentic mode of community. 92 Tovey’s attempts to interpret the atomized pieces of a Haydn sonata movement as existing both for themselves and for the whole in a sense constitute the Hegelian manoeuvre to effect a harmonious union of a fractured totality. To use a Hegelian phrase, Tovey aspired for the part and the whole of a musical work to engage in the activity of mutual recognition . 93 Something about Haydn’s modern sonata style left the work sundered, as ‘bits of coloured glass in Haydn’s kaleidoscope’, calling on the critic to carry out an analysis of reconciliation. In this light, Waltham-Smith’s claim that the works of the Classical style ‘shape, challenge, forge, and affirm modes of listening and relationality’ that complement recent philosophical concerns from Italian political theory and French deconstruction is one that resonates with Tovey’s writings a century earlier. 94

To return to the essay on Haydn’s E flat sonata, after five dense pages that stretch any conventional notions of the programme note to their limits, Tovey presents quite the understatement: ‘This may seem like a formidable analysis of the first twelve bars of a Haydn sonata.’ He proceeds to inform his reader that he will henceforth primarily look at matters of key relation for the rest of the movement, since he has already traced the ‘problems’ Haydn was trying to solve through the unification of piano technique, counterpoint, and phrase structure. It is also a distinctly Toveyan tenet that the analyst ought to approach the work as if the composer were solving some sort of problem. Coming up on the second group, he states an early version of what will become a classic formulation of his theory of sonata form:

Here we expect the ‘second subject’; but it is a fact which is not as universally understood as one might expect, that with Haydn the first-movement form depends far more on balance of key than on fixed principles of alternation of themes. Haydn in the great majority of cases makes his ‘second subject’ consist almost wholly of restatements and amplifications of his first, and if he does use a definite contrasted theme there is no foreseeing what he will do with it on recapitulation. His work is on so small a scale that variety, clearness of articulation in phrase, and nobility of proportion will suffice to make it organically complete without the appeals to memory and the more rigid symmetry that are essential to the beauty of later and larger works … 95

Ever ambitious, Tovey suggests a narrative for the development of the sonata style from Haydn to Mozart and Beethoven, all over the course of a few sentences. It comes down to a matter of scope: Haydn’s forms were compact enough to utilize smaller bits while Mozart, and eventually Beethoven, were to experiment with larger themes and more clear-cut theme-defining sections. Tovey proceeds with his analysis of the second group by considering all three domains of form, pianism, and texture. With regard to the first, a very interesting thing happens at bar 27 (see Ex. 4 ): ‘he gives us a new theme, and … it is rather productive of a pleasing surprise at the enlarging of design than a thing expected as a matter of form. As the design enlarges, so does the humour. There is not the least doubt that this is the most hilarious tune in the world.’ 96 Haydn’s ‘hilarious tune’ is of course an effect of drama, a minor shock to the listener who was expecting a fairly economic use of thematic material already presented in the exposition. It is hilarious since the material, composed of a banal-sounding melody and texture, serves the structurally vital role of expanding the exposition. In terms of Sonata Theory, the ‘most hilarious tune in the world’ follows the first perfect authentic cadence within the dominant key area in the second group (V:PAC in S-space), constituting the essential expositional closure (EEC). The designation could be thrown into question, however, once the listener encounters the diverse array of material leading to the next likely contender for the EEC at the subsequent PAC at bar 40. In effect, the material is mocking its own role, deferring the all-important closure of the exposition all while hardly sounding important itself.

Haydn, Keyboard Sonata in E flat, H. XVI/52, mvt. 1, bb. 25–30

Tovey’s discussion of the development retraces Haydn’s steps, coming to a significant moment at Haydn’s surprising return of ‘the most hilarious tune in the world’ at bar 68. Just before it, the music approaches an ‘emphatic pause’ on the dominant of C minor following ‘the longest rapid passage in the whole movement’, which toggles between tonic and dominant (see Ex. 5 ). With vivid prose, Tovey describes the dramatic goings-on of the charged passage:

Is the development over? And is Haydn going to follow this chord (the dominant of the relative minor) by the tonic E♭ as first note of the opening theme, thereby using the harmonic effect so constantly found in old contrapuntal sonatas and concertos whenever a finale follows without break or a slow movement in the relative minor? If this were Haydn’s intention, the length and range of his development would have been exactly what every listener would have expected; but Haydn intends this sonata to surprise us at every point by its largeness and the nobility of its proportions. Instead of returning to E♭ he moves in precisely the opposite direction, to the extremely distant key of E♮. Once more the most hilarious tune in the world mocks us in this remote region where we have been led by what has all the appearance of caprice and recklessness. 97

The series of bits offers no shortage of drama, with the music seeming to prepare the return of the main theme and then swerving towards a distant key with the distinctive ‘most hilarious tune in the world’. Tovey continues his sensitive approach to reconcile part with whole. From the domain of form, the tune functions as an extension of the development, serving to showcase the scope and length of the movement. But the tune also ‘mocks’ us, combining a shocking new tonal destination with an affect so ‘hilarious’ that, to Tovey, it completely negates the intended course of the preceding developmental material through a moment of sheer impetuosity. By negating what came before it, the tune reveals Haydn’s craft to be floating above convention. The development might go as it ‘ought’ to—as the listener might expect—but it could also be thwarted, and here Haydn’s dramatic sonata style showcases that music now predicated itself on the possibility of being able to pursue either option.

Haydn, Keyboard Sonata in E flat, H. XVI/52, mvt. 1, bb. 63–9

Eventually Haydn reaches the retransition, but his method of arriving on the dominant strikes Tovey as one that calls attention to the juxtaposition of key areas as a compositional device. After the ‘hilarious tune’ returns in a most dramatic way, the music travels from E major to A major and then to B minor, finally shifting down a semitone to reach the dominant of E flat (see Ex. 6 ). Tovey describes the moment as such: ‘The passage lasts just long enough to awaken our expectations of the establishment of this new distant key, B minor, when suddenly a magical “enharmonic modulation” bring us back to the tonic E♭ with an abruptness that produces in us a truly amazed realization of the distance we have travelled in this development.’ 98 A musical work of the sonata style did not necessarily modulate seamlessly from one key to another—it could instead call attention to the very process of modulating, thereby becoming a commentary on the conventional tonal wanderings of a development.

Haydn, Keyboard Sonata in E flat, H. XVI/52, mvt. 1, bb. 72–80

Tovey goes on to claim that Haydn’s deployment of key relations seems to treat foreign keys as ‘mysterious phenomena’ which serves in the E flat sonata to give the ‘impression of unfathomable spaciousness’. It is crucial to Tovey’s conception of the sonata style that methods of key relations do not remain stagnant from Haydn to Brahms, observing that Beethoven began to rationalize foreign keys so that their relations become ‘firmly systematised’. Avoiding the characterization that Haydn’s key relations are irrational or underdeveloped by comparison, Tovey instead claims that their underlying logic requires that they seem mystifying:

[Haydn’s] task is to see that the keys he uses are intelligibly related; but, this done, he needs only to assert them, and it would by no means suit his purpose to demonstrate or even to express their relationship. Let them startle the listener by their capricious and mysterious appearances, and let him feel that they are realities and not accidents, but let them remain mysterious and capricious.