- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Cultural Revolution

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 3, 2020 | Original: November 9, 2009

The Cultural Revolution was launched in China in 1966 by Communist leader Mao Zedong in order to reassert his authority over the Chinese government. Believing that current Communist leaders were taking the party, and China itself, in the wrong direction, Mao called on the nation’s youth to purge the “impure” elements of Chinese society and revive the revolutionary spirit that had led to victory in the civil war 20 years earlier and the formation of the People’s Republic of China. The Cultural Revolution continued in various phases until Mao’s death in 1976, and its tormented and violent legacy would resonate in Chinese politics and society for decades to come.

The Cultural Revolution Begins

In the 1960s, Chinese Communist Party leader Mao Zedong came to feel that the current party leadership in China, as in the Soviet Union , was moving too far in a revisionist direction, with an emphasis on expertise rather than on ideological purity. Mao’s own position in government had weakened after the failure of his “ Great Leap Forward ” (1958-60) and the economic crisis that followed. Chairman Mao Zedong gathered a group of radicals, including his wife Jiang Qing and defense minister Lin Biao, to help him attack current party leadership and reassert his authority.

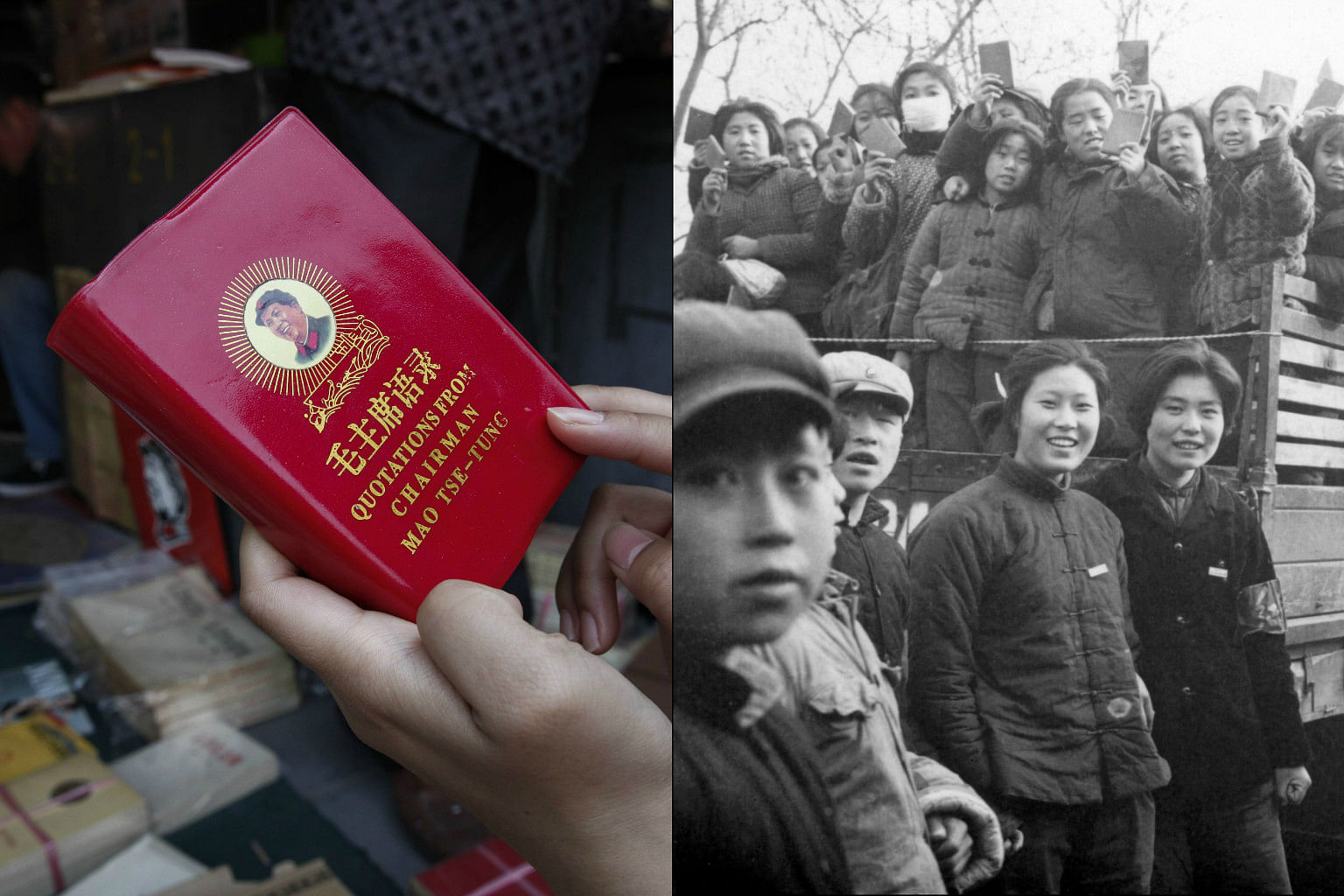

Did you know? To encourage the personality cult that sprang up around Mao Zedong during the first phase of the Cultural Revolution, Defense Minister Lin Biao saw that the now-famous "Little Red Book" of Mao's quotations was printed and distributed by the millions throughout China.

Mao launched the so-called Cultural Revolution (known in full as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution) in August 1966, at a meeting of the Plenum of the Central Committee. He shut down the nation’s schools, calling for a massive youth mobilization to take current party leaders to task for their embrace of bourgeois values and lack of revolutionary spirit. In the months that followed, the movement escalated quickly as the students formed paramilitary groups called the Red Guards and attacked and harassed members of China’s elderly and intellectual population. A personality cult quickly sprang up around Mao, similar to that which existed for Josef Stalin , with different factions of the movement claiming the true interpretation of Maoist thought. The population was urged to rid itself of the “Four Olds”: Old customs, old culture, old habits, and old ideas.

Lin Biao's Role in the Cultural Revolution

During this early phase of the Cultural Revolution (1966-68), President Liu Shaoqi and other Communist leaders were removed from power. (Beaten and imprisoned, Liu died in prison in 1969.) With different factions of the Red Guard movement battling for dominance, many Chinese cities reached the brink of anarchy by September 1967, when Mao had Lin send army troops in to restore order. The army soon forced many urban members of the Red Guards into rural areas, where the movement declined. Amid the chaos, the Chinese economy plummeted, with industrial production for 1968 dropping 12 percent below that of 1966.

In 1969, Lin was officially designated Mao’s successor. He soon used the excuse of border clashes with Soviet troops to institute martial law. Disturbed by Lin’s premature power grab, Mao began to maneuver against him with the help of Zhou Enlai, China’s premier, splitting the ranks of power atop the Chinese government. In September 1971, Lin died in an airplane crash in Mongolia, apparently while attempting to escape to the Soviet Union. Members of his high military command were subsequently purged, and Zhou took over greater control of the government. Lin’s brutal end led many Chinese citizens to feel disillusioned over the course of Mao’s high-minded “revolution,” which seemed to have dissolved in favor of ordinary power struggles.

Cultural Revolution Comes to an End

Zhou acted to stabilize China by reviving educational system and restoring numerous former officials to power. In 1972, however, Mao suffered a stroke; in the same year, Zhou learned he had cancer. The two leaders threw their support to Deng Xiaoping (who had been purged during the first phase of the Cultural Revolution), a development opposed by the more radical Jiang and her allies, who became known as the Gang of Four. In the next several years, Chinese politics teetered between the two sides. The radicals finally convinced Mao to purge Deng in April 1976, a few months after Zhou’s death, but after Mao died that September, a civil, police and military coalition pushed the Gang of Four out. Deng regained power in 1977 and would maintain control over Chinese government for the next 20 years.

Long-Term Effects of the Cultural Revolution

Some 1.5 million people were killed during the Cultural Revolution, and millions of others suffered imprisonment, seizure of property, torture or general humiliation. The Cultural Revolution’s short-term effects may have been felt mainly in China’s cities, but its long-term effects would impact the entire country for decades to come. Mao’s large-scale attack on the party and system he had created would eventually produce a result opposite to what he intended, leading many Chinese to lose faith in their government altogether.

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

China Transformed By Elimination of ‘Four Olds.’ New York Times .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

The early period (1966–68)

- Rise and fall of Lin Biao (1969–71)

- Final years (1972–76)

What were the goals of the Cultural Revolution?

- Who was Mao Zedong?

- What is Maoism?

- How has China changed since Mao Zedong’s death?

- What is Mao Zedong's legacy?

Cultural Revolution

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- CCU Digital Commons - Mao Zedong and the Cultural Revolution: In Theory and Impact

- The Gospel Coalition - 9 Things You Should Know About China’s Cultural Revolution

- Alpha History - Historiography of the Cultural Revolution

- Khan Academy - Chinese Communist Revolution

- The Guardian - The Cultural Revolution: all you need to know about China's political convulsion

- Stanford University - Stanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education - Introduction to the Cultural Revolution

- History Learning Site - The Cultural Revolution

- CNN - How the Cultural Revolution changed China forever

- University of Washington - Cultural Revolution

- Spartacus Educational - Cultural Revolution

- Cultural Revolution - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Cultural Revolution - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

What was the Cultural Revolution?

The Cultural Revolution was an upheaval launched by Chinese Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong during his last decade in power (1966–1976) to renew the spirit of the Chinese Revolution.

Why was the Cultural Revolution launched?

Mao Zedong launched the Cultural Revolution because he feared that China would develop along the lines of the Soviet model, which he did not approve of, and because he was concerned about his own place in history.

Mao Zedong had four goals for the Cultural Revolution: to replace his designated successors with leaders more faithful to his current thinking; to rectify the Chinese Communist Party; to provide China’s youths with a revolutionary experience; and to achieve policy changes so as to make the educational, health care, and cultural systems less elitist.

When did the Cultural Revolution occur?

The Cultural Revolution took place from August 1966 to the autumn of 1976. It was officially ended by the Eleventh Party Congress in August 1977.

Cultural Revolution , upheaval launched by Chinese Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong during his last decade in power (1966–76) to renew the spirit of the Chinese Revolution . Fearing that China would develop along the lines of the Soviet model and concerned about his own place in history, Mao threw China’s cities into turmoil in a monumental effort to reverse the historic processes underway.

During the early 1960s, tensions with the Soviet Union convinced Mao that the Russian Revolution had gone astray, which in turn made him fear that China would follow the same path. Programs carried out by his colleagues to bring China out of the economic depression caused by the Great Leap Forward made Mao doubt their revolutionary commitment and also resent his own diminished role. He especially feared urban social stratification in a society as traditionally elitist as China. Mao thus ultimately adopted four goals for the Cultural Revolution: to replace his designated successors with leaders more faithful to his current thinking; to rectify the Chinese Communist Party; to provide China’s youths with a revolutionary experience; and to achieve some specific policy changes so as to make the educational, health care, and cultural systems less elitist. He initially pursued these goals through a massive mobilization of the country’s urban youths. They were organized into groups called the Red Guards , and led by students such as Song Binbin . Mao ordered the party and the army not to suppress the movement.

Mao also put together a coalition of associates to help him carry out the Cultural Revolution. His wife, Jiang Qing , brought in a group of radical intellectuals to rule the cultural realm. Defense Minister Lin Biao made certain that the military remained Maoist. Mao’s longtime assistant, Chen Boda , worked with security men Kang Sheng and Wang Dongxing to carry out Mao’s directives concerning ideology and security. Premier Zhou Enlai played an essential role in keeping the country running, even during periods of extraordinary chaos . Yet there were conflicts among these associates, and the history of the Cultural Revolution reflects these conflicts almost as much as it reflects Mao’s own initiatives .

Mao’s concerns about “bourgeois” infiltrators in his party and government—those not sharing his vision of communism—were outlined in a Chinese Communist Party Central Committee document issued on May 16, 1966; this is considered by many historians to be the start of the Cultural Revolution, although Mao did not formally launch the Cultural Revolution until August 1966, at the Eleventh Plenum of the Eighth Central Committee. He shut down China’s schools, and during the following months he encouraged Red Guards to attack all traditional values and “bourgeois” things and to test party officials by publicly criticizing them. Mao believed that this measure would be beneficial both for the young people and for the party cadres that they attacked.

The movement quickly escalated; many elderly people and intellectuals not only were verbally attacked but were physically abused. Many died. The Red Guards splintered into zealous rival factions, each purporting to be the true representative of Maoist thought. Mao’s own personality cult , encouraged so as to provide momentum to the movement, assumed religious proportions. The resulting anarchy , terror, and paralysis completely disrupted the urban economy. Industrial production for 1968 dipped 12 percent below that of 1966.

During the earliest part of the Red Guard phase, key Politburo leaders were removed from power—most notably President Liu Shaoqi , Mao’s designated successor until that time, and Party General Secretary Deng Xiaoping . In January 1967 the movement began to produce the actual overthrow of provincial party committees and the first attempts to construct new political bodies to replace them. In February 1967 many remaining top party leaders called for a halt to the Cultural Revolution, but Mao and his more radical partisans prevailed, and the movement escalated yet again. Indeed, by the summer of 1967, disorder was widespread; large armed clashes between factions of Red Guards were occurring throughout urban China.

During 1967 Mao called on the army under Lin Biao to step in on behalf of the Red Guards. Instead of producing unified support for the radical youths, this political-military action resulted in more divisions within the military. The tensions inherent in the situation surfaced vividly when Chen Zaidao, a military commander in the city of Wuhan during the summer of 1967, arrested two key radical party leaders.

In 1968, after the country had been subject to several cycles of radicalism alternating with relative moderation, Mao decided to rebuild the Communist Party to gain greater control. The military dispatched officers and soldiers to take over schools, factories, and government agencies. The army simultaneously forced millions of urban Red Guards to move to the rural hinterland to live, thus scattering their forces and bringing some order to the cities. This particular action reflected Mao’s disillusionment with the Red Guards because of their inability to overcome their factional differences. Mao’s efforts to end the chaos were given added impetus by the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, which greatly heightened China’s sense of insecurity.

Two months later, the Twelfth Plenum of the Eighth Central Committee met to call for the convening of a party congress and the rebuilding of the party apparatus. From that point, the issue of who would inherit political power as the Cultural Revolution wound down became the central question of Chinese politics.

Chinese Revolution

The cultural revolution begins.

The Cultural Revolution (1966-76) was a mass campaign that transformed government and society in the People’s Republic of China. According to its leader and figurehead Mao Zedong , the Cultural Revolution aimed to restore socialism by cleansing the state, the party and society of bourgeois and reactionary elements. To achieve this, Mao mobilised and agitated thousands of students from the schools and universities of Beijing. These students were intensely loyal to Mao, their fanaticism exceeding anything seen in revolutionary Paris or Nazi Germany. The Red Guards , as they became known, were hostile to anyone or anything that opposed the Chairman or impeded his vision for a socialist China. Working in numbers, the Red Guards used pressure, coercion and violence to force obedience to Mao’s will. Through the actions and propaganda of the Red Guards, Mao’s political power and prestige were restored. For millions of ordinary Chinese, the Cultural Revolution was a period of restricted freedom, intimidation, social upheaval and economic disruption.

The context for the Cultural Revolution was Mao Zedong’s loss of power after the disaster of the Great Leap Forward . Mao surrendered the national presidency to Liu Shaoqi (April 1959), though he remained chairman of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Still greatly respected, Mao continued to exert considerable influence over the party and government policy, though he was not the dominant figure of the 1950s. Control of economic policy was picked up by Liu Shaoqi, Deng Xiaoping , Chen Yun and others. From 1960 on, this group wound aspects of the Great Leap Forward, bringing an end to the Great Famine and overseeing China’s economic recovery. They implemented their reforms cautiously, avoiding direct criticisms of Mao, who still retained enormous public support and veneration. Meanwhile, Mao fumed about the economic reforms of the early 1960s. He considered these reforms an abandonment of socialist economic principles and a betrayal of his revolutionary vision. The party, the government and the revolution had been hijacked, Mao claimed, by “those who have taken the capitalist road”.

Finding the precise origin of the Cultural Revolution is difficult. Many historians trace the Cultural Revolution to a play called Hai Rui Dismissed from Office . Written by Wu Han, a Beijing historian, it dramatised the career and downfall of Hai Rui, a 16th century official who dared to voice criticisms of the Jiajing Emperor. Hai Rui was removed from office and sentenced to death, though his sentence was commuted when the emperor died first. When Hai Rui Dismissed from Office was performed in 1961, many interpreted it as an allegory about the downfall of Peng Dehuai. Like Hai Rui, Peng had dared to criticise the emperor (Mao) and had paid for it with his career and his reputation. Mao’s defenders interpreted it this way too and reacted strongly. In late 1965 Yao Wenyuan , a future member of the Gang of Four, penned a lengthy essay condemning the play as political slander. “ Hai Rui Dismissed is not a fragrant flower but a poisonous weed,” Yao said. “If we do not clean it up, it will be harmful to the affairs of the people”.

Mao had long been concerned about art and literature and the dangers they posed to his regime. “Writing novels is popular these days, isn’t it”, he mused in 1962. “The use of novels for anti-party activity is a great invention. Anyone wanting to overthrow a political regime must create public opinion and do some preparatory ideological work.” By the start of 1965, Mao was urging a ‘cultural revolution’. In January the Politburo, responding to Mao’s demands, set up a ‘Five Man Group’ to review anti-socialist attitudes in fields like history, philosophy, literature, law and dramatics. The Five Man Group, led by Peng Zhen , interpreted Mao’s concerns as an academic debate, not a serious political issue. Peng saw no need for state intervention in fields like literature or the arts, nor did he believe culture should be forced to follow party lines. The group’s inaction infuriated Mao, who was insistent that anti-socialist cultural expressions be identified and criticised.

“There is no master script [for the Cultural Revolution]… no blueprint, no scenario, no game plan. All there is are random, scattered remarks – some spontaneous, others carefully hedged; some just possibly meant to be taken at face value, others almost certainly intended to obscure rather than elucidate… We have no firm answers.” Michael Schoenhals, historian

By the second half of 1965, Mao had decided to take action himself. Yao Wenyuan’s essay attacking Hai Rui Dismissed provided a logical starting point. In November, Mao ordered state newspapers to publish Yao’s essay in its entirety. Peng Zhen, believing this risked turning an academic debate into a political confrontation, attempted to block the publication of Yao’s essay but was overruled by Zhou Enlai. Mao’s supporters began to produce a wave of similar essays and articles, each critical of anti-socialist ideas in cultural pieces. Peng’s Five Man Group moved to block these as well. In early 1966 it released a document, the ‘February Outline’, which acknowledged the existence of bourgeois or reactionary sentiments in culture. The solution, it said, was to “seek truth from facts”, to fight bourgeois ideas with better socialist ideas. The February Outline also harked back to an earlier campaign , urging the party to “let one hundred schools of thought contend”.

The February Outline led to an undeclared war between the Five Man Group and Mao and his supporters. Mao emerged victorious on May 16th, when the CCP’s Central Committee voted to disband the Five Man Group and replace it with “a new Cultural Revolution Group”. The committee’s May 16th circular condemned Peng Zhen in the strongest terms and demanded a reorientation of the Cultural Revolution on Mao’s own terms. Peng and three other members of the Five-Man Group were charged with counter-revolutionary sympathies, booted from office and purged from the CCP. The new Cultural Revolution Group was populated with supporters of Mao, including Zhou Enlai , Mao’s wife Jiang Qing , his secretary Chen Boda , security chief Kang Sheng and Yao Wenyuan himself. The Central Committee’s May 16th circular called on loyal party members to “thoroughly criticise and repudiate reactionary bourgeois ideas in the sphere of academic work, education, journalism, literature, art and publishing”, urging them to “seize the leadership in these cultural spheres”.

Mao’s challenge was taken up by young students in high schools and universities, later to become the Red Guards . On May 25th a dazibao (‘big character poster’) appeared on the walls at Tsinghua University in Beijing, urging students to rebel against their teachers and lecturers. They responded enthusiastically and the Reds Guards movement took shape over the following weeks. On July 16th Mao ended a period of public seclusion with his famous ‘good swim’ in the Yangtze River. Despite his age (72) and his portly frame, Mao spent more than an hour floating down the Yangtze. The ‘good swim’ demonstrated to the public that Mao was in good health and ready to retake control of the government. By the end of July, the Red Guards boasted more than one million members in Beijing alone. They looked to Mao for inspiration and direction. On August 1st he penned a letter to the Red Guards at Tsinghua University, offering them his approval and support. Five days later Mao published his famous directive to “Bombard the Headquarters!” and expel the “bourgeois dictatorship” which had “imposed a white terror”.

On August 18th the Chairman appeared before a rally of Red Guards in Tiananmen Square. Mao’s choice of dress – an olive green military uniform – was chosen to replicate theirs. Mao donned the armband worn by the Red Guards and stood for six hours, listening to speeches from Lin Biao , Chen Boda and various Red Guard leaders. Mao attended several similar rallies over the coming weeks. At each rally, the Red Guards were encouraged to attack the ‘Four Olds’: old customs, old culture, old habits and old ideas. Having formed enthusiastically but without much purpose or direction, the Red Guards were given free rein to attack the enemies of Maoist socialism. The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was thus born. What began with some mild allegorical criticism of Mao Zedong in a 1961 play became a sweeping movement that would transform and disrupt China for years to come.

1. Mao Zedong had long wanted a campaign against anti-socialist and anti-CCP criticisms in art and literature. In 1965 he convinced the Politburo to set up a Five Man Group to examine instances of this. 2. In 1961 a play called Hai Rui Dismissed from Office was interpreted as an allegorical criticism of Mao and his purging of Peng Dehuai in 1959. This play was attacked in a November 1965 essay by Yao Wenyuan. 3. The Five Man Group tried to block publication of Yao’s essay and other similar pieces, infuriating Mao. In May 1966 the group was replaced by a clique of Mao loyalists: the Cultural Revolution Group. 4. In May to August 1966, Mao used rhetoric and propaganda to urge militant students to assemble and “bombard the headquarters” and force reactionary and bourgeois figures from positions of authority. 5. As the Red Guards swelled in number, Mao appeared before a series of rallies in August to October, wearing their uniform and symbols and urging them to destroy the ‘Four Olds’.

© Alpha History 2018-23. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use . This page was written by Glenn Kucha and Jennifer Llewellyn. To reference this page, use the following citation: G. Kucha & J. Llewellyn, “The Cultural Revolution begins”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/chineserevolution/cultural-revolution-begins/. This website uses pinyin romanisations of Chinese words and names. Please refer to this page for more information.

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University website

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

"Mao's Last Revolution": China's Cultural Transformation

- Denise Y. Ho

The beginning of China’s Cultural Revolution in 1966 heralded a decade-long period of political turmoil that included attacks on alleged class enemies, the toppling of Party officials high and low, and the reinstatement of political control via revolutionary committees supported by the military. The Cultural Revolution was simultaneously a political and a cultural movement, aiming not only at political upheaval but also the transformation of social and cultural life through Mao Zedong Thought.

An exhibition of Mao badges at the Jianchuan Museum Cluster in Anren, Sichuan Province, a private collection of Mao-era artifacts. Photo by the author.

Historians refer to China’s Mao years as the period from the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 until his death in 1976. The Cultural Revolution decade that concluded the Mao years has been called “Mao’s Last Revolution,” the peak of high socialism. In 1981, the Chinese Communist Party offered its verdict of this era, but both popular memory and recent scholarship challenge the official interpretation.

The Cultural Revolution as Anniversary

What was the official beginning of the Cultural Revolution?

The scholars Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhals call Mao’s attacks on the historian Wu Han in early 1966 the Cultural Revolution’s “first salvos.” This year journalists and others—including the Chinese Communist Party’s official newspaper, the People’s Daily —chose May 16 as the date when Mao Zedong articulated the justification for Cultural Revolution.

This article uses August 8 as the date when the central leadership adopted a decision on the Cultural Revolution, one that was published in the newspaper the following day.

The convention for marking the end of the Cultural Revolution is less ambiguous; most link it to Mao’s death in September of 1976, or to the subsequent arrest and trial of the Gang of Four , a group of political allies that included Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing.

By the Communist Party’s own official verdict in 1981, known as the “Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party,” the Cultural Revolution lasted from May 1966 to October 1976. The resolution acknowledged the period’s tragedies and called them mistakes, laying blame at the feet of the Gang of Four and others, including Mao himself.

However, it was also a document of affirmation, one that—in condemning the Cultural Revolution’s excesses as leftist mistakes—underscored the priorities of socialism, the leadership of the Party, and Mao’s revolutionary legacy. Thirty-five years later this official pronouncement remains the accepted interpretation. Writing on the fiftieth anniversary this May, the People’s Daily reiterated that the resolution “gave correct conclusions on a succession of major historical issues,” and that these conclusions “possess unshakable scientific truth and authority.”

But the very need to state that the official historical interpretation is true belies a uniform and authoritative understanding. The Cultural Revolution, on the contrary, remains a period for historical debate. Just as we might debate what date marked its beginnings, we might also debate what the Cultural Revolution was. New accounts, both popular and scholarly, reveal multiple understandings of the Cultural Revolution: what it was, what it was to whom, and why it mattered.

The Cultural Revolution as High Politics

In its beginnings, the Cultural Revolution was viewed from the lens of high politics. The journalists who observed as it unfolded made note of hierarchies of power, and the political scientists who wrote its first histories used the sources then accessible, official news reports and speeches that were shaped and given by those in political control.

The Cultural Revolution as high politics is the story of Mao and his inner circle, of the Central Cultural Revolution Group, of loyalty and betrayal. The milestones of this narrative include the attack on and fall of Liu Shaoqi , the Chinese head of state, and later the alleged planned coup and mysterious death of Lin Biao , Mao’s right hand man.

“The Chinese People's Liberation Army is the great school of Mao Zedong Thought,” a propaganda poster from the Cultural Revolution featuring Mao, 1969.

The 1981 resolution is in large part a story of high politics; it exonerates Liu and excoriates Lin Biao and the Gang of Four. Though the resolution makes brief mention of the “masses” and the “people” as workers, peasants, soldiers, intellectuals, youth, and officials, they are a faceless and nameless backdrop to the drama of central power.

And yet we know that the Cultural Revolution as a political movement was far more than high politics. As ordinary people experienced it, the Cultural Revolution was decidedly local, whether it became factional fighting within one’s school or work unit, or attacks on local powerholders and the creation of new revolutionary committees, or punishment and violence meted on class enemies old and new.

In a recent book, historians Jeremy Brown and Matthew Johnson highlight the difficulty of trying to separate out state officials from others in society. They call instead for a focus on everyday life at the grassroots because this was a time when state and society at the local level shared the same face. To look beyond high politics is also to acknowledge that there were many Cultural Revolutions.

The Cultural Revolution as Red Guards

Use the word “Cultural Revolution” and people think immediately of the iconic Red Guards . There is good reason for this: Mao himself celebrated youth, young people were truly inspired to make revolution, the Red Guards were—through their actions and their portrayal—made a symbol of the Cultural Revolution.

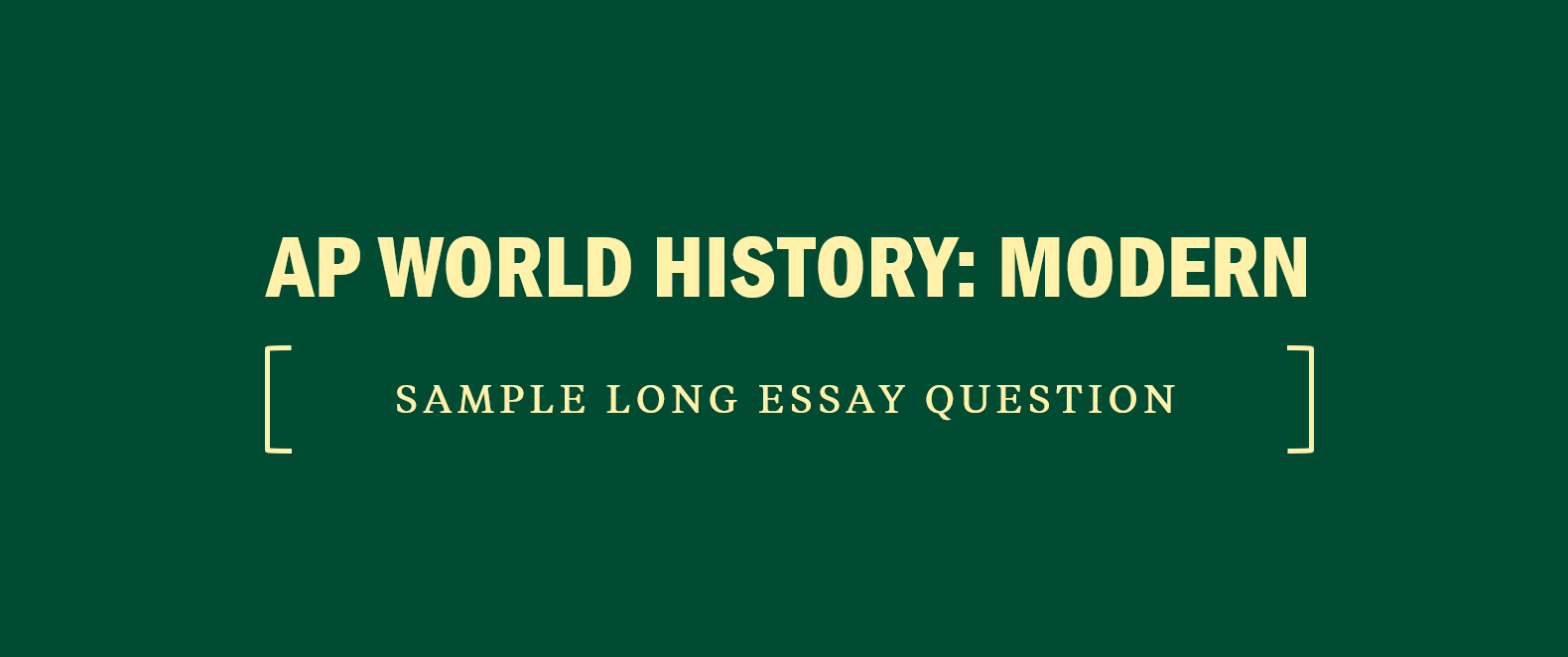

They flooded the streets in military uniforms to destroy the “old world,” they gathered by the million in rallies on Tian’anmen Square , and they went on epic journeys to reenact the Red Army’s historic Long March and to “exchange revolutionary experience.” Red Guards were both the sources of terror and the subjects of propaganda, Chairman Mao’s “revolutionary successors.” They were demobilized and sent to the country by 1968, becoming the generation of the “sent-down youth” and coming of age in exile.

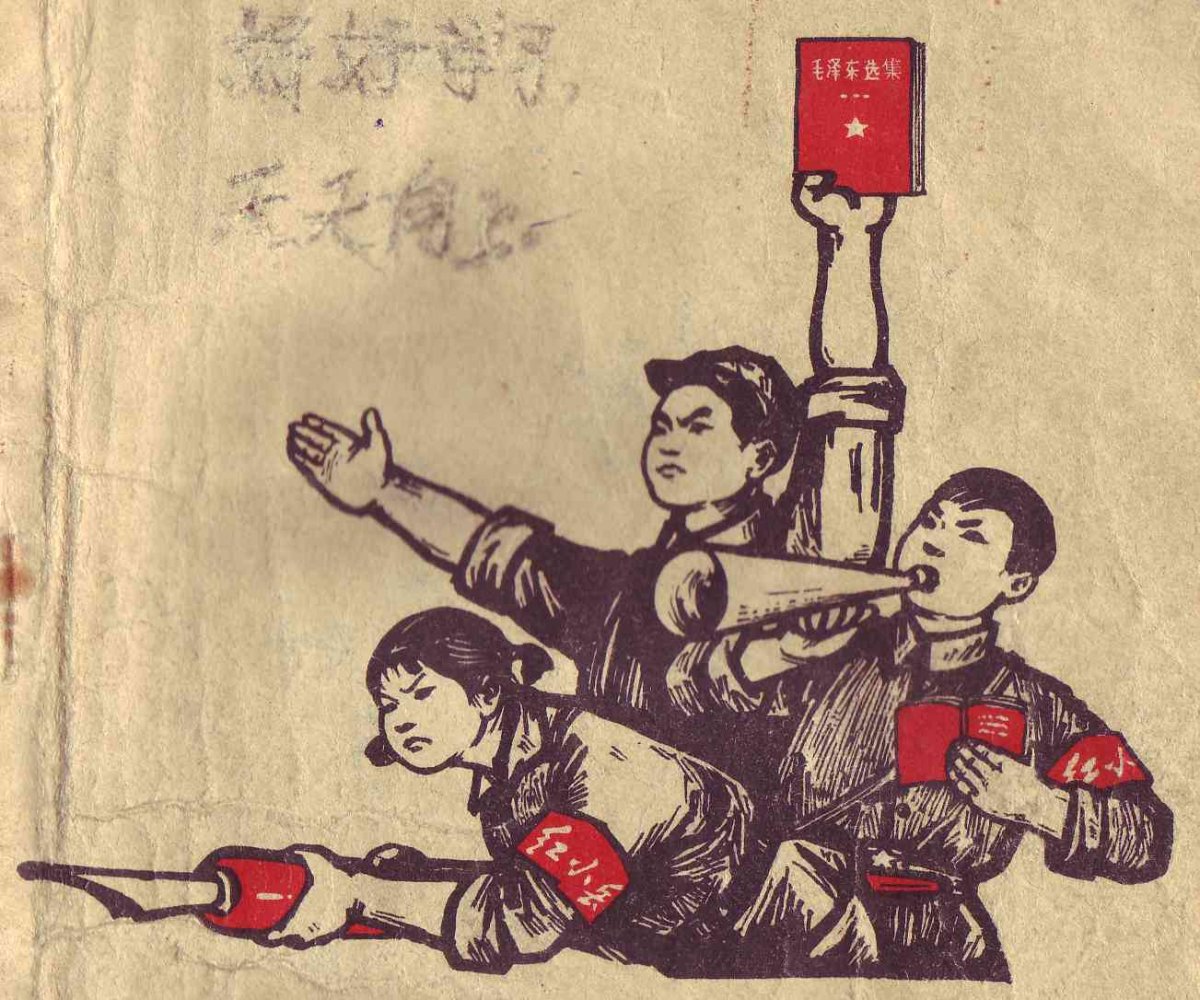

Holding a copy of ”Selected Works of Mao Zedong," Red Guards are featured on the cover of a Guangxi elementary school textbook, 1971.

For young people the Cultural Revolution had its own chronology: the heady days of 1966, their rustification (moving from urban areas to the countryside) in 1968, and then long years of waiting before opportunities to go home were even possible.

But if Red Guards were the most visible—and today most remembered—group of participants, they were by no means the only one. Many young people did not participate in the Red Guard movement, and for them these years were marked by political apathy or other kinds of intellectual searching. Unmoored by the strictures of school and adult authority, they wandered and read forbidden books.

And of course, our focus on young people who would have been at school is to privilege a certain group. In Shanghai, for example, the Cultural Revolution’s participants included the industrial city’s workers, many of whom were discontent with stagnant economic conditions and systemic and rigid class structures. Other cities were engulfed with such factional violence to such an extent that order was restored only through military takeover.

However, it is the Red Guards who come to mind first, for a number of reasons—they were and are an icon that inspired others in the Global 1960s, and the youth of this generation became today’s leadership. In the Red Guards rest two central tropes of the Cultural Revolution: the utopianism of youth and the danger of chaos. The hot blood of youth is easier to forgive than the machine of the state, and chaos is easier to blame than power.

The Cultural Revolution as Urban and Intellectual

Scholars of the Mao period often make the point that we know much more of the Cultural Revolution, with its estimated over one million deaths, than we know of the Great Leap Forward movement and its subsequent rural famine (1958-1961), which claimed an estimated thirty million deaths. This is partly because many of those who suffered in the Cultural Revolution were intellectuals, but this is also because intellectuals are people who write, and after the Cultural Revolution these victims’ memoirs, literature, and essays were ways in which people could make sense of its suffering.

When people refer to a Cultural Revolution’s “lost generation,” they usually mean the young people who were sent to the countryside and who received limited schooling. But another way to think of a “lost generation” is to think of the elder generations who were silenced by previous political campaigns, who spent the decade imprisoned in so-called “ox pens” and assigned to menial labor, and who lost the opportunity to build “New China,” a chance some even returned from abroad to pursue. And of course many did not live to see the Cultural Revolution’s conclusion nor their names rehabilitated.

Without denying the tragedy of urban intellectuals, new scholarship has turned to the countryside to uncover different narratives. Some scholars, comparing the Mao years to the post-Mao years of reform , argue that some Cultural Revolution policies had a leveling effect that brought positive benefits to the countryside, including educational opportunities at all levels. Others have found the emergence of economic strategies that went against the planned economy, suggesting that reform-era policies built on a previous record of success.

But the countryside also had its tragedies. The sociologist Yang Su, for example, has shown how episodes of collective killings unfolded in the countryside in Guangdong and Guangxi Provinces, the distance from a center of power creating the conditions for violence against supposed class enemies. Systemic and targeted violence continued to unfold in later Cultural Revolution campaigns; unlike the Red Guard movement, this violence took place away from the public eye. We are only starting to explore the Cultural Revolution experience of those doubly marginalized: in rural areas and of ethnic minority status.

The Cultural Revolution as Social Transformation

The Cultural Revolution was the culmination of Mao’s efforts to transform Chinese society. This was manifest not only in slogans to “bombard the headquarters” and “overturn heaven-and-earth,” but also in the movement’s very premise. If others in the Communist Party leadership had believed that transforming society’s economic structure would ultimately lead to cultural transformation, Mao suggested otherwise: cultural transformation would herald the victory of China’s revolution.

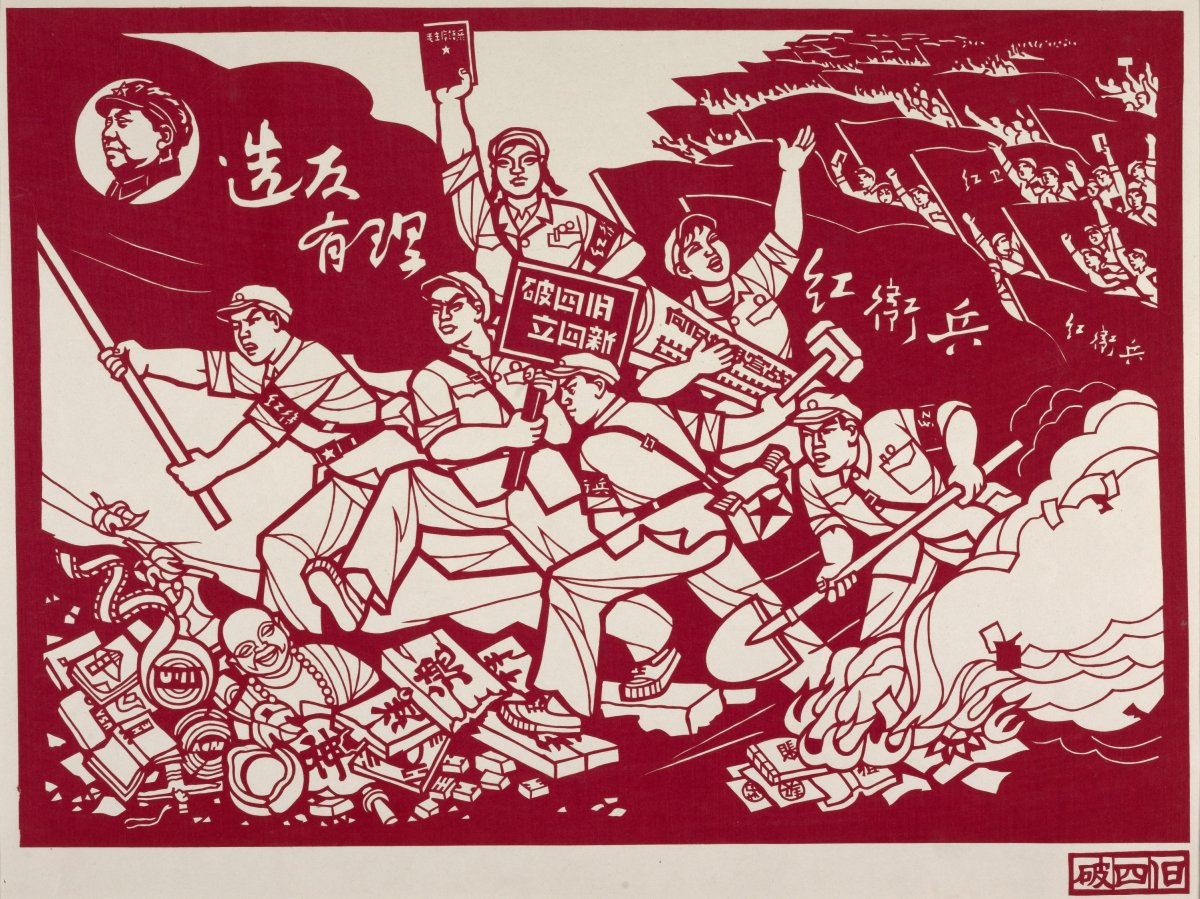

"Eliminate the Four Olds and Establish the Four News," 1967 propaganda poster.

To be sure, the Cultural Revolution—and the Mao years at large—did change Chinese society: it overturned traditional family relationships, it called knowledge into question (substituting “red” for “expert”), it discredited authority political and intellectual, and it defined class not just in terms of property but also through history, standpoint, and behavior. Some critics of the Cultural Revolution today regard it as period in which traditional Chinese society was destroyed, with deep repercussions in our present.

Yet there is another way of framing the narrative of social transformation, one that takes Cultural Revolution rhetoric at face value. That is, that the Cultural Revolution was truly—in its origins—an attempt to prevent revisionism from taking hold in China’s Communist Revolution, that it was an attack on the class privilege that arose from socialist China’s bureaucratic system, and that it was an argument that class behavior should matter more than class background.

Studying bottom-up responses, what he calls “the Cultural Revolution at the margins,” anthropologist Yiching Wu makes the case that some individuals did take all of Mao’s claims seriously, but in their—sometimes brutal—silencing, the state foreclosed discussion of both these critiques and their alternate utopian visions. This version of the Cultural Revolution story is a foundation narrative for today’s authoritarianism.

The Cultural Revolution as History

Can the Cultural Revolution be history?

For the Chinese Communist Party, the Cultural Revolution is history in the sense that it is past. There was a verdict in 1981, and an historical accounting that rendered Mao Zedong seventy percent good and thirty percent bad. If the 1981 resolution concluded by discussing economic gains—among others—achieved during the ten years of turmoil, today’s Chinese regime under Xi Jinping claims that the same document has “withstood the test of experience, the test of the people, and the test of history.”

What the People’s Daily means by “the test of the people” is unclear, but by “the test of history” the editorialist argues that the post-Mao era of reform was successful because it negated the Cultural Revolution. He also criticizes “meddling from the left and the right that focuses on the problems of the Cultural Revolution,” suggesting that somehow any investigation that does not accord with official interpretation might lead China on a backward slide to 1966.

On the side of the former home of the landlord Liu Wencai in Anren, Sichuan Province, remnants of a Mao Zedong quotation linger from the Cultural Revolution. Photo by the author.

But if “being history” is to be examined, researched, analyzed, critiqued, and debated, then the official history of the Cultural Revolution is not history. In China today, many individuals—from amateur historians who seek their family history to academics who must publish in limited ways or abroad—are doing history, even if they cannot do so openly.

Some of these scholars are doing the work of preservation, hoping that future generations may be able to write a people’s history of the Cultural Revolution. Outside of China more can be published, but these scholars also work with limited sources and restricted access. The Cultural Revolution will become history when all of these historians can submit to “the test of history,” to see if the images we make are indeed an accurate mirror.

The Cultural Revolution will be history when it belongs to the public, when it allows for grassroots accounts, access to sources, social reckoning, and the right to memorialize. In China today there is but one officially designed Cultural Revolution historic site, a graveyard in the city of Chongqing where Red Guards who died in factional fighting are buried—but it is locked, off-limits to all but descendants.

On university campuses, one can see busts and statues of individuals whose dates reveal that they died in the ten years of turmoil—but such monuments are celebrations of lives rather than investigations into their endings. There are few other traces, save glimpses of faded slogans on old buildings—but these markings are an idle curiosity, often slated for demolition (see photo above). Only when ordinary citizens can choose how to mourn, what to remember, and which traces to preserve can historical event face “the test of the people.”

Find anything you save across the site in your account

What Are the Cultural Revolution’s Lessons for Our Current Moment?

By Pankaj Mishra

On September 24, 1970, the Rolling Stones interrupted their concert at the Palais des Sports in Paris to invite a French Maoist called Serge July onstage. News of an earthshaking event called the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution had been trickling out of China since 1966. Information was scarce, but many writers and activists in the West who were opposed to the United States and its war in Vietnam were becoming fascinated with Mao Zedong , their earlier infatuation with Soviet-style Marxism having soured. Jean-Paul Sartre hawked copies of a banned Maoist newspaper in Paris, and Michel Foucault was among those who turned to China for political inspiration, in what Sartre called “new forms of class struggle in a period of organized capitalism.”

Editors at the influential French periodical Tel Quel learned Chinese in order to translate Mao’s poetry. One of them was the feminist critic Julia Kristeva , who later travelled to China with Roland Barthes . Women’s-liberation movements in the West embraced Mao’s slogan “Women hold up half the sky.” In 1967, the Black Panther leaders Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale financed the purchase of guns by selling copies of Mao’s Little Red Book. In 1971, John Lennon said that he now wore a Mao badge and distanced himself from the 1968 Beatles song “Revolution,” which claimed, “If you go carrying pictures of Chairman Mao / You ain’t going to make it with anyone anyhow.” But the Rolling Stones’ Paris concert was Maoism’s biggest popular outing. July, who, with Sartre, later co-founded the newspaper Libération , asked the throng to support French fellow-Maoists facing imprisonment for their beliefs. There was a standing ovation, and then Mick Jagger launched into “Sympathy for the Devil.”

Western intellectuals and artists would have felt much less sympathy for the Devil had they heard about the ordeals of their counterparts in China, as described in “ The World Turned Upside Down ” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), a thick catalogue of gruesome atrocities, blunders, bedlam, and ideological dissimulation, by the Chinese journalist Yang Jisheng. Yang mentions a group of elderly writers in Beijing who, in August, 1966, three months after Mao formally launched the Cultural Revolution, were denounced as “ox demons and snake spirits” (Mao’s preferred term for class enemies) and flogged with belt buckles and bamboo sticks by teen-age girls. Among the writers subjected to this early “struggle session” was the novelist Lao She, the world-famous author of “ Rickshaw Boy .” He killed himself the following day.

There were other events that month—“bloody August,” as it came to be called—that might have made Foucault reconsider his view of Maoism as anti-authoritarian praxis. At a prestigious secondary school in Beijing, attended by the daughters of both Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping , students savagely beat a teacher named Bian Zhongyun and left her dying in a handcart. As detailed in a large-character poster that was adopted by cultural revolutionaries across China, one of the indictments against Bian was her inadequate esteem for Mao. While taking her students through an earthquake drill, she had failed to stress the importance of rescuing the Chairman’s portrait.

Red Guards—a pseudo-military designation adopted by secondary-school and university students who saw themselves as the Chairman’s sentinels—soon appeared all over China, charging people with manifestly ridiculous crimes and physically assaulting them before jeering crowds. Much murderous insanity erupted after 1966, but the Cultural Revolution’s most iconic images remain those of the struggle sessions: victims with bowed heads in dunce caps, the outlandish accusations against them scrawled on heavy signboards hanging from their necks. Such pictures, and others, in “ Forbidden Memory ” (Potomac), by the Tibetan activist and poet Tsering Woeser, show that even Tibet, the far-flung region that China had occupied since 1950, did not escape the turmoil. Woeser describes the devastation wrought on Tibet’s Buddhist traditions by a campaign to humiliate the elderly and to obliterate what were known as the Four Olds—“old thinking, old culture, old customs, and old habits of the exploiting classes.” The photographs in Woeser’s book were taken by her father, a soldier in the Chinese military, and found by her after he died. There are vandalized monasteries and bonfires of books and manuscripts—a rare pictorial record of a tragedy in which ideological delirium turned ordinary people into monsters who devoured their own. (Notably, almost all the persecutors in the photographs are Tibetan, not Han Chinese.) In one revealing photo, Tibet’s most famous female lama, once hailed as a true patriot for spurning the Dalai Lama, cowers before a young Tibetan woman who has her fists raised.

Closer to the center of things, in Xi’an, the Red Guards paraded Xi Zhongxun, a stalwart of the Chinese Communist Revolution who had fallen out with Mao, around on a truck and then beat him. His wife, in Beijing, was forced to publicly denounce their son— Xi Jinping , China’s current President. Xi Jinping’s half sister was, according to official accounts, “persecuted to death”; most probably, like many people tortured by the Red Guards, she committed suicide. Xi spent years living in a cave dwelling, one of sixteen million youths exiled to the countryside by Mao.

Link copied

According to estimates quoted by Yang, as many as a million and a half people were killed, thirty-six million persecuted, and a hundred million altogether affected in a countrywide upheaval that lasted, with varying intensity, for a decade—from 1966 to 1976, when Mao died. Mao’s decrees, faithfully amplified by the People’s Daily , which exhorted readers to “sweep away the monsters and demons,” gave people license to unleash their id. In Guangxi Province, where the number of confirmed murder victims reached nearly ninety thousand, some killers consumed the flesh of their victims. In Hunan Province, members of two rival factions filled a river with bloated corpses. A dam downstream became clogged, its reservoir shimmering red.

In 1981, the Chinese Communist Party described the Cultural Revolution as an error. It trod carefully around Mao’s role, instead blaming the excesses on his wife, Jiang Qing, and three other ultra-Maoists—collectively known, and feared, as the Gang of Four. Deng Xiaoping, the Chinese leader supervising this pseudo-autopsy, had been maltreated during the Cultural Revolution, but he had also abetted it, and was eager to indefinitely postpone close scrutiny. He urged the Chinese to “unite and look forward” ( tuanjie yizhi xiang qian kan ). As class struggle gave way to a scramble for upward mobility, the sheer expediency of this repudiation of the past was captured in a popular pun on Deng’s slogan: “look for money” ( xiang qian kan ).

In the four decades since, China has moved from being the headquarters of world revolution to being the epicenter of global capitalism. Its leaders can plausibly claim to have engineered the swiftest economic reversal in history: the redemption from extreme poverty of hundreds of millions of people in less than three decades, and the construction of modern infrastructure. Some great enigmas, however, remain unsolved: How did a well-organized, disciplined, and successful political party disembowel itself? How did a tightly centralized state unravel so quickly? How could siblings, neighbors, colleagues, and classmates turn on one another so viciously? And how did victims and persecutors—the roles changing with bewildering speed—live with each other afterward? Full explanations are missing not only because archives are mostly inaccessible to scholars but also because the Cultural Revolution was fundamentally a civil war, implicating almost all of China’s leaders. Discussion of it is so fraught with taboo in China that Yang does not even mention Xi Jinping, surely the most prominent and consequential survivor today of Mao’s “chaos under heaven.”

Notwithstanding this strategic omission, Yang’s book offers the most comprehensive journalistic account yet of contemporary China’s foundational trauma. Memoirs of the Cultural Revolution, first appearing in the nineteen-eighties, belong by now to a distinct nonfiction genre—from confessions by repentant former Red Guards (Jung Chang’s “ Wild Swans ,” Ma Bo’s “ Blood Red Sunset ”) to searing accounts by victims (Ji Xianlin’s “ The Cowshed ”) to family sagas (Aiping Mu’s “ The Vermilion Gate ”). The period’s outrages animate the work of many of China’s prominent novelists, such as Wang Anyi, Mo Yan , Su Tong, and, most conspicuously, Yu Hua , whose two-volume novel “ Brothers ” includes an extended description of a lynching, with details that seem implausible but that are amply verified by eyewitness testimony.

Yang provides the larger political backdrop to these granular accounts of cruelty and suffering. At the outset of the Cultural Revolution, he was studying engineering at Beijing’s prestigious Tsinghua University, and he was one of the many students who travelled around the country to promote the cause. In 1968, he became a reporter for Xinhua News Agency, a position that gave him access to many otherwise unreachable sources. This vantage enabled him to write “ Tombstone ” (2012), a well-regarded history of the Great Famine, caused by Mao’s Great Leap Forward. The new book is almost a sequel, and Mao remains the central figure: China’s unchallenged leader, as determined as ever to fast-forward the country into genuine Communism. With the Great Leap Forward, Mao had hoped to industrialize China by encouraging household steel production. With the Cultural Revolution, he seemed to sideline economic development in favor of a large-scale engineering of human souls and minds. Social equality, in this view, would come about by plunging the Chinese into “continuous revolution,” a fierce class struggle that would permanently inflame the political consciousness of the masses.

Yang describes the background to Mao’s change of direction. The spectacle of Khrushchev denouncing Stalin, in 1956, only to be himself removed and disgraced, in 1964, made Mao increasingly prone to see “revisionists” at every turn. He feared that the Chinese Revolution, achieved at tremendous cost, risked decaying into a self-aggrandizing, Soviet-style bureaucracy, remote from ordinary people. Mao was also smarting from the obvious failure of his economic policies, and from implicit criticism by colleagues such as Liu Shaoqi, China’s de-jure head of state from 1959 onward. Yang describes, in often overwhelming detail, the intricate internal power struggle that eventually erupted into the Cultural Revolution—with Mao variously consulting and shunning a small group of confidants, including his wife, a former actress; China’s long-standing Premier, Zhou Enlai; and the military hero Lin Biao, who had replaced Peng Dehuai, a strong critic of Mao, as the Minister of Defense in 1959, and proceeded to turn the People’s Liberation Army into a pro-Mao redoubt.

Sensing political opposition in his own party, Mao reached beyond it, to people previously not active in politics, for allies. He tapped into widespread grievance among peasants and workers who felt that the Chinese Revolution was not working out for them. In particular, the Red Guards gave Mao a way of bypassing the Party and securing the personal fealty of the fervent rank and file. As the newly empowered students formed ad-hoc organizations, and assaulted institutions and figures of authority, Mao proclaimed that “to rebel is justified,” and that students should not hesitate to “bombard the headquarters.” In 1966, he frequently appeared in Tiananmen Square, wearing a red armband, with hundreds of thousands of Red Guards waving flags and books. Many of his fans avoided washing their hands after shaking his. Mao’s own hands were once so damaged by all the pressing of callow flesh that he was unable to write for days afterward. Predictably, though, he soon lost control of the world he had turned upside down.

Late in 1966, the younger Red Guards were challenged by an older cohort, who formed competing Red Guard units; they, in turn, were challenged by heavily armed “rebel forces.” All factions claimed recognition as the true voice of the Chairman. By early 1967, workers had joined the fray, most significantly in Shanghai, where they surpassed Red Guards in revolutionary fervor. Mao became nervous about the “people’s commune” they established, though he and his followers had often upheld the Paris Commune, from 1871, as a model of mass democracy. So ferocious was one military mutiny, in Wuhan, that Mao, who had arrived in the city to mediate between rival groups, had to flee in a military jet, amid rumors that a swimmer with a knife in his mouth had been spotted in the lake by Mao’s villa. “Which direction are we going?” the pilot asked Mao as he boarded the plane. “Just take off first,” Mao replied.

Growing alarmed by the sight of continuous revolution, Mao tried to restore order in the cities, exiling millions of young urban men and women to the countryside to “learn from the peasants.” He purged Liu Shaoqi, who died shortly thereafter, and Deng Xiaoping was sent to work in a tractor-repair factory in a remote rural province. Mao increasingly turned to the People’s Liberation Army to establish control. He replaced broken structures of government with “revolutionary committees.” These committees, dominated by Army commanders, were effectively a form of military dictatorship in many parts of China. Partly in order to keep the military on his side, Mao named his Defense Minister, Lin Biao, as his official successor, in October, 1968. But a border conflict with the Soviet Union the following year further expanded the military’s power, and a paranoid Mao, soon regretting his move, sought to isolate Lin. In an extraordinary turn of events, in 1971, Lin died in a plane crash in Mongolia with several of his family members; allegedly, he was fleeing China after failing to assassinate Mao.

Prompted, even forced, by internal crises and external challenges, Mao opened China’s doors to the United States and, in early 1972, received Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger in Beijing, much to the bewilderment of those in the West who had seen China as leading a global resistance to American imperialism. (When Kissinger flattered Mao, saying that students at Harvard University had pored over his collected works, he demurely replied, “There is nothing instructive in what I wrote.”) The following year, Mao brought back Deng Xiaoping, entrusting him with China’s ailing economy. Then he changed his mind again, once it became apparent that the lingering malevolence of the Gang of Four was causing people to rally behind Deng. Mao had just re-purged Deng and launched a new campaign against Deng’s “capitalist roading” when, in September, 1976, he died. Within a month, the Gang of Four was in prison. (Jiang Qing, given a life sentence, spent her time in jail making dolls for export, until authorities noticed that she embroidered her name on all of them; she killed herself in 1991.) The Cultural Revolution was over, and Deng was soon ushering China into an era of willed amnesia and “looking for money.”

The surreal events of the Cultural Revolution seem far removed from a country that today has, by some estimates, the world’s largest concentration of billionaires. Yet Xi Jinping’s policies, which prioritize stability and economic growth above all, serve as a reminder of how fundamentally the Cultural Revolution reordered Chinese politics and society. Yang, although obliged to omit Xi’s personal trajectory—from son of Mao’s comrade to China’s supreme leader—nonetheless leaves his readers in no doubt about the “ultimate victor” of the Cultural Revolution: what he calls the “bureaucratic clique,” and the children of the privileged. Senior Party cadres and officials, once restored to their positions, were able to usher their offspring into the best universities. In the system Deng built after the Cultural Revolution, a much bigger bureaucracy was conceived to “manage society.” Deeply networked within China’s wealthy classes, the bureaucratic clique came to control “all the country’s resources and the direction of reform,” deciding “who would pay the costs of reforms and how the benefits of reform would be distributed.” Andrew Walder, who has published several authoritative books on Maoist China, puts it bluntly: “China today is the very definition of what the Cultural Revolution was intended to forestall”—namely, a “capitalist oligarchy with unprecedented levels of corruption and inequality.”

Yang stresses the need for a political system in China that both restricts arbitrary power and cages the “rapaciousness” of capital. But the Cultural Revolution has instilled in many Chinese people a politically paralyzing lesson—that attempts to achieve social equality can go calamitously wrong. The Chinese critic Wang Hui has pointed out that criticisms of China’s many problems are often met with a potent accusation: “So, do you want to return to the days of the Cultural Revolution?” As Xi Jinping turns the world’s largest revolutionary party into the world’s most successful conservative institution, he is undoubtedly helped by this deeply ingrained fear of anarchy.

Outside China, the legacy of the Cultural Revolution is even more complex. Julia Lovell, in her recent study, “ Maoism: A Global History ,” demonstrates how ill-informed Western fervor for Mao eventually helped discredit and divide the left in Europe and in America, enabling the political right to claim a moral high ground. Many zealous adepts of Maoism in the West turned to highlighting the evils of ideological and religious extremism. Sympathy for nonwhite victims of imperialism and slavery, and struggling postcolonial peoples in general, came to be stigmatized as a sign of excessive sentimentality and guilt. This journey from Third Worldism to Western supremacism can be traced in the titles of three books from the past four decades by Pascal Bruckner, one of the French dabblers in Maoism—“The Tears of the White Man: Compassion as Contempt” (1983), “The Tyranny of Guilt: An Essay on Western Masochism” (2006), and “An Imaginary Racism: Islamophobia and Guilt” (2017).

Misperceptions of China abound in this sectarian discourse. As the Soviet Union imploded after a failed experiment with political and economic reform, China, the last surviving Communist superpower, was presumed to have no option but to embrace Western-style multiparty democracy as well as capitalism. But China has managed to postpone the end of history—largely thanks to the Cultural Revolution. In the Soviet Union, when Mikhail Gorbachev introduced his hopeful plans for perestroika and glasnost, the Communist Party and the military had faced little domestic challenge to their authority since the death of Stalin; along with bureaucratic cliques that had serenely fattened themselves during decades of economic and political stagnation, they were able to contest, and finally thwart, Gorbachev’s vision. In China, by contrast, such institutions had been greatly damaged by the Cultural Revolution, with the result that Deng, setting out to rebuild them in his image, faced much less opposition. Class struggle during the Cultural Revolution had left the old power holders as well as the revolutionary masses utterly exhausted, desperate for stability and peace. Deng shored up his authority and appeal by reinstating purged and disgraced officials and by rehabilitating many victims of the Red Guards, including, posthumously, the novelist Lao She.

During the worst years of the Cultural Revolution, Mao had rejected all emendations to his economic playbook. Even when China seemed on the verge of economic collapse, he railed against “capitalist roading.” Deng not only accelerated the marketization of the Chinese economy but also strengthened the party that Mao had done so much to undermine, promoting faceless officials known for their administrative and technical competence to senior positions. China’s unique “model”—a market economy supervised by a technocratic party-state—could only have been erected on ground brutally levelled by Mao’s Cultural Revolution.

“History,” E. M. Cioran once wrote, “is irony on the move .” Bearing out this maxim, cultural revolutions have now erupted right in the heart of Western democracies. Chaos-loving leaders have grasped power by promising to return sovereignty to the people and by denouncing political-party apparatuses. Mao, who was convinced that “anyone who wants to overturn a regime needs to first create public opinion,” wouldn’t have failed to recognize that the phenomenon commonly termed “populism” has exposed some old and insoluble conundrums: Who or what does a political party represent? How can political representation work in a society consisting of manifold socioeconomic groups with clashing interests?

The appeal of Maoism for many Western activists in the nineteen-sixties and seventies came from its promise of spontaneous direct democracy—political engagement outside the conventional framework of elections and parties. This seemed a way out of a crisis caused by calcified party bureaucracies, self-serving élites, and their seemingly uncontrollable disasters, such as the endless war in Vietnam. That breakdown of political representation, which provoked uprisings on the left, has now occurred on an enlarged scale in the West, and it is aggravated by attempts, this time by an insurgent ultra-right, to forge popular sovereignty, overthrow the old ruling class, and smash its most sacred norms. The great question of China’s Maoist experiment looms over the United States as Donald Trump vacates the White House: Why did a rich and powerful society suddenly start destroying itself?

The Trumpian assault on the West’s “olds” has long been in the making, and it is, at least partly, a consequence of political decay and intellectual ossification—akin to what Mao diagnosed in his own party. Beginning in the nineteen-eighties, a consensus about the virtues of deregulation, financialization, privatization, and international trade bound Democrats to Republicans (and Tories to New Labour in Britain). Political parties steadily lost their old and distinctive identities as representatives of particular classes and groups; they were no longer political antagonists working to leverage their basic principles—social welfare for the liberal left, stability and continuity for the conservative right—into policies. Instead, they became bureaucratic machines, working primarily to advance the interests of a few politicians and their sponsors.

In 2010, Tony Judt warned, not long before his death, that the traditional way of doing politics in the West—through “mass movements, communities organized around an ideology, even religious or political ideas, trade unions and political parties”—had become dangerously extinct. There were, Judt wrote, “no external inputs, no new kinds of people, only the political class breeding itself.” Trump emerged six years later, channelling an iconoclastic fury at this inbred ruling class and its cherished monuments.

Trump failed to purge all the old élites, largely because he was forced to depend on them, and the Proud Boys never came close to matching the ferocity and reach of the Red Guards. Nevertheless, Trump’s most devoted followers, whether assaulting his opponents or bombarding the headquarters in Washington, D.C., took their society to the brink of civil war while their chairman openly delighted in chaos under heaven. Order appears to have been temporarily restored (in part by Big Tech, one of Trump’s enablers). But the problem of political representation in a polarized, unequal, and now economically debilitated society remains treacherously unresolved. Four traumatic years of Trump are passing into history, but the United States seems to have completed only the first phase of its own cultural revolution. ♦

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Adam Gopnik

By Daniel Immerwahr

The Chinese Cultural Revolution and Traditional Leadership Style Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Bibliography

In the year 1966, Mao Zedong felt that the leaders of the communist party in china were leading not only the party but the entire country in the wrong direction. 1 He, therefore, decided to initiate a revolution that would lead the country back to its traditional leadership style, where power is not with the bourgeoisie but with the people. His call was for the youth to eliminate all the foreign and new elements in Chinese society and bring back the spirit that had won them the civil war decades before. 2 With the help of other radical leaders such as Lin Biao, he mobilized the youths to form paramilitary groups, which they called the Red Guards, to fight against the bourgeoisie mentality perpetrated by the then leaders of the CCP, Liu Shaoqi, and Deng Xiaoping. 3

The Red Guards formed by the youths later disintegrated into different factions, all of which fighting for supremacy. This forced Mao to bring in the army to help in restoring order in the country. The army pushed all the youth paramilitary groups to the rural areas, subduing the movement. 4 Out of these groups, there emerged a radical group that envisioned a new thought of the revolution. They called themselves Shengwulian and were based in Hunan Province. 5 They were opposed to both the ideologies of Mao and the other leaders of the party. According to them, the revolution was about one class overthrowing the other. 6 They also added that “the revolution had turned the relationship between the people and party leaders from that of leaders and the led to that of rulers and the ruled and between exploiters and the exploited.” 7

I think Mao’s intentions were good but his approach was dictatorial. He envisioned a nation where all the citizens are equal. He detested the leadership that was in power at the time for their bourgeoisie spirit and wanted all the citizens to live as one equal community. However, his use of the military in the suppression of the Red Guards was uncalled for. That was very autocratic.

He should have listened to all their grievances and consolidated them into a philosophy that would help him lead them as a united group. Worse still, his betrayal of a former ally, Liu Biao, portrayed him as a very selfish individual whose only interest was power. He interpreted Liu’s actions as a way of usurping his position. As a result, he decided to go after him, causing his death. Liu was involved in a fatal plane crash while fleeing from Mao.

Mao’s course was both ill and well-intentioned. His good intentions are seen in his struggle to rid the country of capitalistic and bourgeoisie mentality. According to him, the country was better off with communism, where they lived as one community with no superior and inferior citizen, and not with a set up where leaders want to get rich at the expense of the majority of the citizens.

He wanted the change to happen in the shortest time possible. Hence, he had to use radical means to ensure that this happened as fast as he wanted it. However, a critical view of the revolution shows that he might have used the revolution as an avenue to restore his power and influence, having lost it six years earlier. 8 Besides, the use of the army in suppressing the Red Guards and his former ally, Liu, shows that his interests were not in the equality he claimed to stand for, but in getting power.

Blum, Susan Debra, and Lionel M Jensen. China off Center . Honolulu: University of Hawai Press, 2006.

Wu, Yiching. The Cultural Revolution at the Margins, London: Harvard University Press, 2014.

- Yichang Wu. The Cultural Revolution at the Margins, London: Harvard University Press, 2014, 146.

- Ibid., 147.

- Ibid., 148.

- Ibid., 149.

- Ibid., 152.

- Ibid., 166.

- Susan Debra Blum and Lionel M Jensen. China off Center . Honolulu: University of Hawai Press, 2006, 120.

- Ibid., 125.

- Chinese Cultural Revolution and Committees

- Hung Liu Artistic Work and its Contribution to Human Life

- Mao Zedong: A Blessing or Curse for the Chinese People

- The Communist Manifesto and Japan in 20th Century

- Hashima Islands as a World Heritage Site

- The Article "Letter to Jen An" by Ssu-ma Ch'ien's

- The Cultural Revolution at the Margins Chinese Socialism

- The Balfour Declaration: Israel Creation and Palestinian Conflict

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, July 25). The Chinese Cultural Revolution and Traditional Leadership Style. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-chinese-cultural-revolution/

"The Chinese Cultural Revolution and Traditional Leadership Style." IvyPanda , 25 July 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/the-chinese-cultural-revolution/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'The Chinese Cultural Revolution and Traditional Leadership Style'. 25 July.

IvyPanda . 2020. "The Chinese Cultural Revolution and Traditional Leadership Style." July 25, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-chinese-cultural-revolution/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Chinese Cultural Revolution and Traditional Leadership Style." July 25, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-chinese-cultural-revolution/.

IvyPanda . "The Chinese Cultural Revolution and Traditional Leadership Style." July 25, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-chinese-cultural-revolution/.

The Straits Times

- International

- Print Edition

- news with benefits

- SPH Rewards

- STClassifieds

- Berita Harian

- Hardwarezone

- Shin Min Daily News

- Tamil Murasu

- The Business Times

- The New Paper

- Lianhe Zaobao

- Advertise with us

- Cultural Revolution

7 questions about China's Cultural Revolution answered

May 16 marks 50 years of China's Cultural Revolution. Here's what you should know about the political movement.

1. What is the Cultural Revolution and its goal?

The Cultural Revolution (May 1966 - October 1976) was a political movement launched by Chinese leader Mao Zedong, with the express purpose of eradicating "the bourgeois headquarters" and seizing power from capitalist roaders, or people accused of favouring capitalism, according to the official Chinese narrative.

It plunged the country into chaos, with the economy paralysed and millions of Chinese persecuted in violent struggles.

Mao consolidated power after purging officials he deemed to be political rivals, notably State President Liu Shaoqi. The paramount leader rose to a god-like status amid a series of propaganda campaigns.

2. Who were the Red Guards?

The Red Guards often refer to the fanatical armband-wearing students who pledged allegiance to Mao and vowed to act in line with his instructions during the Cultural Revolution. As the political movement gained momentum, young workers and peasants also joined the Red Guards.

Mao gave the Red Guards free rein to confiscate private property, destroy national treasures and torture whoever they labelled "counter-revolutionaries". Official record shows they murdered 1,772 people in Beijing alone in August and September 1966.

The violence soon spun out of control after the Red Guards started to storm government and party buildings. The group was also plagued by factionalism that led to armed clashes.

The central government decided to restore order from early 1967, with the People's Liberation Army deployed to crack down on armed factions. Members of the main Red Guard units were subsequently dispersed after Mao launched the "Up To the Mountain, Down To the Village" movement, which saw millions of jobless youth sent to villages for re-education.

3. What were the Four Olds?

The Four Olds - a concept proposed in 1966 by Marshal Lin Biao, Mao's then heir apparent - referred to the "old ideas, culture, customs and habit of the exploiting classes" that need to be destroyed.

Lin did not elaborate on the definitions, so the Red Guards took it upon themselves to smash things and torture people they thought are representative of the Four Olds.

The radicals started a reign of red terror by confiscating private property belonging to teachers and former businessmen. They evicted some 77,000 "monsters and freaks" from Beijing, and publicly humiliated and attacked "counter-revolutionaries" including officials, intellectuals and monks in the so-called struggle sessions.

Also, the Red Guards desecrated thousands of historical sites in Beijing. In what may be the worst case of destruction, they smashed 6,618 registered cultural artefacts in the Confucius Temple in Shangdong province.

They also renamed people, streets and schools to remove "feudal" overtones. Personal names like Wei Dong (Protect Mao) and Xiang Hong (Follow Red) gained popularity. In Beijing, the Chang'an Avenue, named after the capital of the Han and Tang dynasties, was changed to "East is Red Avenue". Some even proposed to rename Beijing the "East is Red City", but it was rejected by Premier Zhou Enlai.

4. What is the Little Red Book?

The Little Red Book, or Quotations from Chairman Mao, was the bible of the Red Guards, who often waved it while chanting the quotes as part of the ritual to show loyalty. Some people even started their daily conversations with a Mao-quote.

The book, first launched in 1964, came with different editions, but the compact ones that could fit into a pocket were the most popular. Billions of copies were believed to have been printed during the Cultural Revolution.

Marshal Lin promoted the book to the Red Guards during Mao's first rally with the students in 1966. He reportedly called on the students to "say Long Live in your months, hold the Quotations in your hands".

Here are some oft-used quotes from the Little Red Book:

Study well, and make progress every day. A revolution is not a dinner party. Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun. We should support whatever our enemies oppose and oppose whatever our enemies support. All reactionaries are paper tigers.

5. Who were the sent-down youth?

The sent-down youth, also known as "educated youth", were the young people who left cities to work and live in the rural areas between 1950s and 1970s. Many of them lost the opportunity to go to university.

The authorities began to glorify labour in the countryside as early as 1953, but mass migration of the young started in late 1960s when Chairman Mao launched the "Up To the Mountain, Down To the Village" movement.

More than 16 million people, mostly students, were sent to the countryside between 1967 and 1976 for re-education, which historians say was a means to disperse the Red Guards. Another reason for the movement could be a lack of urban employment opportunities, with more than four million idle high school graduates in 1968.

6. How many people died as a result of the Cultural Revolution?

China did not release official data on the number of victims, but various estimates put the death toll at between hundreds of thousands and several million.

An article published in 2003 by The China Quarterly claims that between 750,000 and 1.5 million of people died in the countryside, with a similar number permanently injured. About 36 million suffered some form of political persecution, the article adds.

Professor John Fairbank, a prominent American historian of China, says the number of victims "hover around a million".

Hong Kong's Cheng Ming magazine, citing China's undisclosed "internal investigation", says 1.72 million people suffered from unnatural death, and another 237,000 died in "armed struggle".

7. How did the Cultural Revolution end?

The capture of the Gang of Four on Oct 6, 1976, is often seen as marking the end of the Cultural Revolution.

As Mao's health declined in the later stages of the Cultural Revolution, the clique wielded tremendous power and took aim at moderates like Premier Zhou, raising the ire of the party's influential elders.

Shortly after Mao's death, his designated political heir Hua Guofeng won the support of the army and party elders, and staged a coup against the Gang of Four. Hua later said crushing the clique symbolises the end of the Cultural Revolution.

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

- ST explainers

Read 3 articles and stand to win rewards

Spin the wheel now

Stanford University

SPICE is a program of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies.

Introduction to the Cultural Revolution

The “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution,” usually known simply as the Cultural Revolution (or the Great Cultural Revolution), was a “complex social upheaval that began as a struggle between Mao Zedong and other top party leaders for dominance of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and went on to affect all of China with its call for “continuing revolution.” 1 This social upheaval lasted from 1966 to 1976 and left deep scars upon Chinese society.