- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Beccaria – “On Crimes And Punishments”

November 4, 2018 By Margit

Cesare Beccaria is seen by many people as the “father of criminology.” Here is a brief summary of his ideas and famous essay “On Crimes and Punishments,” both in video and text format.

Table of Contents

Discussions about Crime and Punishment

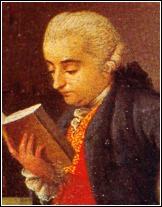

Cesare Beccaria is seen by many people as the “father of criminology” for his ideas about crime, punishment, and criminal justice procedures. He was an Italian born as an aristocrat in the year 1738 in Milan. At that time European thought about crime and punishment was still very much dominated by the old idea that crime was sin and that it was caused by the devil and by demons. And in part to punish the devil and the demons that were causing crime, very harsh punishments were used. At the time when Beccaria came along, the era of Enlightenment was in full swing, and scientists were starting to challenge the old views, but the people who had political power were not ready to leave those old ideas behind yet.

Beccaria didn’t start out as an intellectual. In fact, he wasn’t considered to be above average or interested really when it came to science or philosophy. But after he completed his law studies at the University of Pavia, he started to surround himself with a group of young men who were interested in all kinds of philosophical issues and social problems. And the intellectual discussions that Beccaria was able to have with these people led him to question many of the practices that were common in his time, including the way in which offenders were being punished for their crimes.

Publication of Beccaria’s “On Crimes and Punishments”

Beccaria’s famous work, “On Crimes and Punishments,” was published in 1764, when he was 26 years old. His essay called out the barbaric and arbitrary ways in which the criminal justice system operated. Sentences were very harsh, torture was common, there was a lot of corruption, there were secret accusations and secret trials, and there was a lot of arbitrariness in the way in which sentences were imposed. There was no such thing as equality before the law. And powerful people of high status were treated very differently from people who were poor and who did not have a lot of status.

Beccaria’s ideas clashed dramatically with these practices. And I’ll go through some of the central principles that his work is based on.

Only the Law Can Prescribe Punishment

According to Beccaria, only the law can prescribe punishment. It is up to the legislator to define crime and to prescribe which punishment should be imposed. It is not up to a magistrate or a judge to impose a penalty if the legislator has not prescribed it. And neither is it up to a judge to change what the law says about how a crime should be punished. The judge should do exactly what the law says.

The Law Applies Equally to All People

In addition, Beccaria said that the law applies equally to all people. And so punishment should be the same for all people, regardless of their power and status.

Making the Law and Law Enforcement Public

Beccaria also believed in the power of making the law and law enforcement public. More specifically, laws should be published so that people actually know about them, and trials should be public, too. Only then can onlookers judge if the trial is fair.

Beccaria: Punishments Should be Proportional, Certain, and Swift

Regarding severe punishment, Beccaria said that if severe punishments do not prevent crime, they should not be used. Instead, punishments should be proportional to the harm that the crime has caused. According to Beccaria, the aim of punishment is not to cause pain to the offender, but to prevent them from doing it again and to prevent other people from committing crime. In order to be able to do that, Beccaria believed that punishment should be certain and swift. He believed that if offenders were sure that they would be punished and if punishment would come as quickly as possible after the offense, that this would have the largest chance of preventing crime.

Beccaria Argued Against the Death Penalty

As another controversial issue, Beccaria argued against the death penalty. In his view, the state does not have the right to repay violence with more violence. And in addition to that, Beccaria believed that the death penalty was useless. The death penalty is momentary, it is not lasting and therefore the death penalty cannot be very successful in preventing crimes. Instead, lasting punishments, such as life imprisonment, would be more successful in preventing crimes, because potential offenders will find this a much more miserable condition than the death penalty.

No Right To Torture

Similarly, according to Cesare Beccaria, the state does not have the right to torture. Because no one is guilty until he or she is found guilty, no one has the right to punish a person by torturing him or her. Plus, people who are under torture will want the torture to stop and might therefore make false claims, including that they committed a crime they did not commit. So torture is also ineffective.

The Power of Education

Instead of torture and severe penalties, Beccaria believed that education is the most certain method of preventing crime.

Beccaria: Controversy and Success

Beccaria’s ideas are hardly controversial today, but they caused a lot of controversy at the time, because they were an attack on the entire criminal justice system. Beccaria initially published his essay anonymously, because he didn’t necessarily consider it to be a great idea to publish such radical ideas. And this idea was partly confirmed when the book was put on the black list of the Catholic Church for a full 200 years.

But even though his ideas were controversial back then, his essay became an immediate success. In fact, Cesare Beccaria’s ideas became the basis for all modern criminal justice systems and there is some evidence that his essay influenced the American and French revolutions which happened not long after the publication of the essay. His ideas were not original, because others had also proposed them, but Beccaria was the first one to present them in a consistent way. Many people were ready for the changes that he proposed, which is why his essay was such a success.

Beccaria ends his essay with what can be seen as a kind of summary of his view:

“So that any punishment be not an act of violence of one or of many against another, it is essential that it be public, prompt, necessary, minimal in severity as possible under given circumstances, proportional to the crime, and prescribed by the laws.”

You can find Cesare Beccaria’s full essay “On Crimes and Punishments” here .

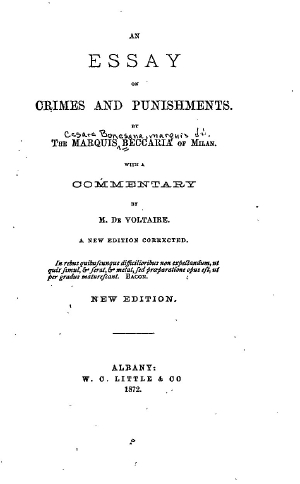

An Essay on Crimes and Punishments

- Cesare Bonesana di Beccaria (author)

- Voltaire (author)

An extremely influential Enlightenment treatise on legal reform in which Beccaria advocates the ending of torture and the death penalty. The book also contains a lengthy commentary by Voltaire which is an indication of high highly French enlightened thinkers regarded the work.

- EBook PDF This text-based PDF or EBook was created from the HTML version of this book and is part of the Portable Library of Liberty.

- ePub ePub standard file for your iPad or any e-reader compatible with that format

- Facsimile PDF This is a facsimile or image-based PDF made from scans of the original book.

- Kindle This is an E-book formatted for Amazon Kindle devices.

An Essay on Crimes and Punishments. By the Marquis Beccaria of Milan. With a Commentary by M. de Voltaire. A New Edition Corrected. (Albany: W.C. Little & Co., 1872).

The text is in the public domain.

- United States

Related Collections:

Detail from The Good Government (1338-9), by Ambrogio Lorenzetti. To the right: Magnanimity, Temperance and Justice seated above prisoners. From a fresco at the Palazzo Pubblico, Siena, Italy. Photo by Getty Images

The first socialist

Well before bentham, cesare beccaria radically questioned the right of the state to imprison and execute its citizens.

by Lorenzo Zucca + BIO

On 12 April 1764, the citizens of Milan witnessed the brutal killing of Bartolomeo Luisetti. He had been condemned to death after being accused of sodomy. Luisetti was killed by asphyxiation and then burnt at the stake in front of the crowd. Throughout Europe, ruling elites believed that criminal justice had to be done and be seen to be done; and that criminal punishment had to be cruel so as to instil the fear of God in the people watching the horrific spectacle.

Cesare Beccaria witnessed the scene with horror. It was hard to believe that such cruelty could be regarded as a rational response. At the time of the event, Beccaria was only in his mid-20s, but already had strong political and philosophical views. Born in 1738, the first son of a prominent Milanese aristocrat, he was educated in a stifling Jesuit school in Parma. After studying law in Pavia, he returned to Milan where his eyes were opened by Montesquieu’s Lettres persanes (1721), or Persian Letters, an epistolary novel giving an outsider’s critical angle on Parisian customs. Beccaria entered the world of Enlightenment philosophy without hesitation; his lodestars were French and British intellectuals, and he was inspired in particular by reading Claude Adrien Helvétius, Denis Diderot, David Hume and John Locke.

In 1759, Beccaria became a member of the so-called ‘ academy of fisticuffs ’, a group of young Milanese aristocrats who rebelled against the oppression of the local elite, including their own families: the conflict was social and intergenerational. As they saw it, the interests of the few systematically trumped the interests of the many, and the laws were designed to increase the power of the privileged class. Their collaboration gave birth to a magazine called Il Caffé, a vehicle for reformist ideas. In 1762, Rousseau published The Social Contract, which provided Beccaria with an ideological framework: his treatise On Crimes and Punishments (1764) was published two years later, and 25 years before the French Revolution. Beccaria’s manifesto against cruel punishment spread swiftly through Europe, igniting radical reforms of repressive and coercive institutions throughout the continent.

Europe was at that time a profoundly hierarchical society, where a few privileged people ruled over the entire population with an arbitrary and unaccountable authority. Enlightenment philosophers took inequality to be the germ of social injustice. Beccaria had the ambition to radically reform his society, the institutions and the laws. It was an ambition shared by all Enlightenment thinkers in Europe, although the means to achieve that reform differed. France took the revolutionary path, while Milan engaged in steady reforms from within; Beccaria and the other pugilists were to play an important part in the administration of the city state.

European radical thinkers agreed that the Church was one of the strongest enforcers of inequality and subjection. Indeed, Italian political minds never ceased to be inspired by Niccolò Machiavelli’s central idea that Christian morality is incompatible with the morality of Civic Republicanism. The former is passive, and requires obedience to the established authority; the latter is active, and demands participation in the political affairs of the city. Only when the city was put first would institutions and laws reflect the interests of the whole society, and not just the vested interests of a few privileged ones.

Mindful of the interest of the many, Beccaria formulated a motto: la massima felicità divisa nel maggior numero (the greatest happiness shared among the greater number), which was subsequently adopted by the English utilitarian thinker Jeremy Bentham. Beccaria saw this maxim as a fundamental tenet of a new science, whose object was human society and whose name was ‘the science of man’, echoing Hume’s project in that phrase. Beccaria’s keen interest in mathematics and the sciences was channelled into the development of political economy and, soon afterwards, Beccaria was made chair of political economy in Milan, his first civic appointment.

Political economy for Beccaria was not just a tool with which to administer the state more efficiently; it was a Copernican revolution that explained the place of man in society, and the importance of reconceiving politics to serve the interests of any particular society. Political economy was intended to be the science of happiness, and aimed to replace religion as the guiding light of human behaviour. Beccaria was aware that great progress had been achieved in public matters through political economic reforms: trade replaced wars, print spread new ideas, and the relation between sovereign and subjects had been reconceived. But he also noted that little had been said and done about the cruelty and arbitrariness of criminal laws, the most immediate and visible display of brute force that had not yet been subject to rational analysis. He knew that it was not uncommon in those years to see people condemned to death and brutally ravaged in the public square with the intent of educating the citizenry.

On Crimes and Punishments was the first attempt to apply principles of political economy to the practice of punishment so as to humanise and rationalise the use of coercion by the state. After all, arbitrary and cruel punishment was the most immediate instrument that the state had to terrorise the people into submission, so as to avoid rebellion against the hierarchical structure of the society. The problem that Beccaria faced, then, was the simple fact that the elite had complete control of the law, which was a family business and a highly esoteric language that only the initiated could master. The path leading to the rational reform of penal law required a fundamental philosophical rethinking of the role and place of law in society.

B eccaria’s project was to dismantle the edifice of Roman law, which he mockingly referred to as ‘a few odd remnants of the laws of an ancient conquering race codified 1,200 years ago by a prince ruling at Constantinople’. The law was an arcane language of power, he felt; its content was unclear and imprecise as it was made of the odd admixture of Roman law, local customs, and it was ‘bundled up in the rambling volumes of obscure academic interpreters’. The opacity of the law was deliberate and instrumental to the control of the people.

Beccaria was a trained lawyer as well as a published mathematician, but philosophy was the key to his mission of reform. On Crimes and Punishments was the first glaring model of an excoriating work of censorial jurisprudence. As the English philosopher H L A Hart pointed out in 1982:

Bentham admired Beccaria not only because he agreed with his ideas and was stimulated by them but also because of Beccaria’s clear-headed conception of the kind of task on which he was engaged. According to Bentham, Beccaria was the first to embark on the criticism of law and the advocacy of reform without confusing this task with the description of the law that actually existed.

Beccaria’s work was entirely censorial; he was the first legal philosopher to maintain a very firm distinction between evaluation and description of the law.

Philosophy was the critical tool that Beccaria used to revolutionise the way in which European societies thought about the law. He was not interested in what the law said: the rule of law was, at the time of his writing, a chimera, since the law obeyed the rule of lawyers and catered for the interests of the few. Beccaria’s censorial approach focused on the law as a social institution that had always been taken for granted as a benevolent instrument of social order. Beccaria’s contribution to the philosophical methodology was monumental, but we should not forget that this philosophical turn had an underlying ambition of substantial social, political and institutional reform.

Beccaria was accused of being a ‘socialist’, in this term’s earliest known vernacular appearance. The charge came from two opposite directions: Padre Facchinei, a theologian who dreaded the rise of political economy as an immanent replacement for religion, used it first. Then came French economists, the so-called Physiocrats and other freemarketeers, who criticised Beccaria for the demanding role he gave the state in the economy, a stance that pointed the way to redistribution and social justice. Both Facchinei and the Physiocrats, along with Adam Smith, believed that the market was a spontaneous order guided by an invisible hand , possibly that of God. Beccaria disagreed: political institutions had a significant interventionist role to play in bridging the gap between the rich and the poor, which he plausibly regarded as the prime cause of crime.

Whether or not Beccaria was a socialist in a way we would recognise today is debatable. He certainly was, however, a secular political thinker whose main aim was to promote a free and equal society, and his main focus was on political justice as opposed to divine justice. Political justice, he believed, exists only because of the creation of a political society, which is a free association of men through the social contract. Thus, crime is defined as a breach of the social contract and not as a sin.

His originality lies in the way he arrives at a compromise between freedom and utility in the name of justice

Under the social contract, people agree to pool together a minimum portion of their freedom so as to guarantee its protection under the unified power of an authority: they swap their natural freedom in the state of nature for political freedom in the civil order of the state. The social contract is not a moment of celebration. People grudgingly agree to sign a pact with each other, and they are frequently tempted to break that pact to pursue their own advantage. What moves them to stick to the pact is the feeling of uncertainty, which makes it impossible to enjoy their natural freedom to act according to their immediate passions. The uncertainty as to how to exercise natural freedom leads everyone to accept a basic necessity: something has to be given away in order for everyone to enjoy genuine political freedom. Everyone’s minimum portion of natural freedom constitutes the public deposit of sovereignty which is the basis for the right to punish those actions that are injurious to the human society. The right to punish is a necessary evil that is exercised by the sovereign in order to respond to the radical uncertainty created by the unfettered exercise of natural freedom.

Political freedom is a psychological, qualitative state and not something that can be measured or quantified by the law. However, the law can help by giving clear and predictable guidance as to what counts as socially harmful behaviour, which will in turn result in the feeling of security. Criminal law’s aim is to guarantee political freedom. Beccaria’s insistence on the rule of law as the guarantor of individual liberty was later on enshrined in Article 4 of the French Declaration of the Rights of the Man and the Citizen (1789):

Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one else; hence the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits except those which assure to the other members of the society the enjoyment of the same rights. These limits can only be determined by law.

Yet Beccaria’s originality does not lie in developing innovative interpretations of utility, political freedom or the social contract. His originality lies in the way he combines them to arrive at a compromise between freedom and utility in the name of justice. As far as criminal justice is concerned, the right to punish must be as narrow as possible if it is to be considered legitimate. The conclusion of On Crimes and Punishments could not be clearer:

In order that punishment should not be an act of violence perpetrated by one or many upon a private citizen, it is essential that it should be public, speedy, necessary, the minimum possible in the given circumstances, and determined by the law.

This theorem set in motion a cultural revolution. Beccaria’s little tract is the symbol of a philosophical movement that was bent on replacing entrenched forms of knowledge that were used by elites to preserve their privileges. The traditional understanding of the law was arcane and inaccessible. Beccaria wanted to replace it with a demystified conception of the law as the product of social fact, whose sole source would be legislation. He also knew that religion was still a potent form of social control; for that reason, he enthusiastically embraced the turn to political economy as a source of knowledge that government could use to ground its policies on reason. It is important to stress, however, that his philosophical method was the driving force of his ideas. He used philosophy to undermine the grounds of ancient law, and to carve out an immanent domain of politics, free from traditionalist and moralist understandings of justice.

T o justify punishment using reason meant to reduce – even to minimise – the quantity and quality of violence within the society. Not only the violence attached to crimes, but also the violence entailed by the reaction to crimes by private parties and by public authorities. Beccaria’s goal was to regulate the right to punish, and eradicate from its practice all forms of vengeance and religious beliefs. This idea of rational punishment has its advocates and its detractors, of course. Advocates understand that cruel and arbitrary punishment does not build a robust sense of trust in the public authority; they also believe that punishment might be a necessary deterrent against the use of private and public violence, so they accept punishment as expressing society’s commitment against violence. On the other hand, detractors believe that rationalising punishment amounts to giving the state a more efficient instrument with which to control and discipline us. Both views are important, but for Beccaria the project of rationalising punishment had a deep reformist meaning. It meant moving from a society that wielded punishment as a weapon of mass control to a society in which punishment would only be the last resort, and proportional to the crime.

Minimum Criminal Law is an apt formula to describe Beccaria’s critique of the practice of punishment. It refers to the specific nature of Beccaria’s social contract, which stipulates only a minimum transfer of natural freedom. In return, the contract will justify only a minimum restriction on natural freedom and suffering. The principle of minimum evil is deduced from the sacrificial nature of the contract: the minimum transfer of natural freedom for the maximum gain of political freedom.

Because the intervention of criminal law is limited by necessity, the state can use criminal law only as a final resort. If there are other means to prevent crimes, they should be used. This part of Beccaria’s thought is often ignored by those who consider him the forefather of utilitarianism in England or the ancestor of law and economics in the United States. This is so because Beccaria asks for the least penal intervention, and for the maximum provision of social services as part of the same package. It is criminal law that must be kept to a minimum, not the state. Beccaria requires a robust intervention of the state to redress inequality and to prevent crimes by educating and assisting people, not by repressing them.

Should we invest in tracking petty thieves, or should the system focus its attention on grand-scale criminality?

Beccaria’s views conquered Europe’s enlightened circles. He was received in Paris as a hero by the philosophes : Diderot annotated his little tract, and Voltaire wrote a review claiming that the reform of criminal law along Beccaria’s ideas ought to become one of the centrepieces of the Enlightenment’s reforms. Thomas Jefferson, who resided at the time in Paris, read the book in Italian, and sent copious notes back to the American founding fathers. Catherine II of Russia even invited Beccaria to lead the drafting of the Russian penal code and the reform of criminal justice. Beccaria’s tract became so popular that in 1866 Fyodor Dostoyevsky borrowed its title for one of his major works. In less than a century, Europe had started to implement his ideas: torture began to disappear, and the death penalty was abolished in a growing number of states. To celebrate the 100th anniversary of On Crimes and Punishments , the Italian Parliament voted in 1865 to abolish the death penalty in the kingdom and to erect a statue of Beccaria in his native Milan.

Quietly ignored for a century or more, Beccaria’s little book is being rediscovered today. Why? I suspect that his radical, reformist spirit hits a deep chord with many people. Inequality is again on the rise. In most countries, criminalisation is also on the rise: criminal law attempts to micromanage the behaviour of the many, while giving a blank cheque to wealthy billionaires whose tax-dodging and exploitative behaviour go unpunished.

We have once more reached a point where we need to reconsider the whole system of criminal justice. It is not about tinkering with what we have; it is about reforming criminal law radically. What hurts our society more? Should we invest endless amounts of resources tracking petty thieves and minor infringements, or should the system focus its attention on grand-scale criminality?

Beccaria denounced the inequality between the ruling class and the masses: he insisted that disproportionate inequality is bound to increase the crime rate because of poverty and injustice. In turn, that predicament is likely to bring only more social conflict and less certainty about security in society. Penal practices are likely to worsen as a result of this; and criminal law might well become once more a force serving the strong against the most vulnerable. In our societies, which are deeply polarised and unequal, Beccaria’s thought still rings true: we need more social justice and less criminal punishment. To have seen this already in the 18th century was remarkable.

Thinkers and theories

Paper trails

Husserl’s well-tended archive has given him a rich afterlife, while Nietzsche’s was distorted by his axe-grinding sister

Peter Salmon

Philosophy of mind

The problem of erring animals

Three medieval thinkers struggled to explain how animals could make mistakes – and uncovered the nature of nonhuman minds

Moral progress is annoying

You might feel you can trust your gut to tell right from wrong, but the friction of social change shows that you can’t

Daniel Kelly & Evan Westra

The disruption nexus

Moments of crisis, such as our own, are great opportunities for historic change, but only under highly specific conditions

Roman Krznaric

What is intelligent life?

Our human minds hold us back from truly understanding the many brilliant ways that other creatures solve their problems

Abigail Desmond & Michael Haslam

History of ideas

Chaos and cause

Can a butterfly’s wings trigger a distant hurricane? The answer depends on the perspective you take: physics or human agency

Erik Van Aken

An Essay on Crimes and Punishments

Anonymous 1767 English translation of Dei delitti e delle pene (1764). Foundational text of modern criminology. Famous for the Marquis Beccaria's arguments against torture and capital punishment. Warning: template has been deprecated.

PUNISHMENTS,

TRANSLATED FROM THE ITALIAN;

COMMENTARY,

ATTRIBUTED TO

Mons. De VOLTAIRE,

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH.

THE FOURTH EDITION

Printed for F. Newbery, at the Corner of St. Paul's Church-Yard.

- Preface of the Translator

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Cesare Bonesana di Beccaria, An Essay on Crimes and Punishments [1764] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of

Publication of Beccaria's "On Crimes and Punishments". Beccaria's famous work, "On Crimes and Punishments," was published in 1764, when he was 26 years old. His essay called out the barbaric and arbitrary ways in which the criminal justice system operated. Sentences were very harsh, torture was common, there was a lot of corruption ...

An Essay on Crimes and Punishments. Cesare Bonesana di Beccaria (author) Voltaire (author) An extremely influential Enlightenment treatise on legal reform in which Beccaria advocates the ending of torture and the death penalty. The book also contains a lengthy commentary by Voltaire which is an indication of high highly French enlightened ...

2,900 words. Syndicate this essay. On 12 April 1764, the citizens of Milan witnessed the brutal killing of Bartolomeo Luisetti. He had been condemned to death after being accused of sodomy. Luisetti was killed by asphyxiation and then burnt at the stake in front of the crowd. Throughout Europe, ruling elites believed that criminal justice had ...

An essay on crimes and punishments ... An essay on crimes and punishments by Beccaria, Cesare, marchese di, 1738-1794; Voltaire, 1694-1778. Publication date 1778 Topics Criminal law, Crime, Criminals, Punishment, Capital punishment, Torture, Law reform Publisher Edinburgh, Printed for Alexander Donaldson Collection smithsonian Contributor

An essay on crimes and punishments ... An essay on crimes and punishments by Beccaria, Cesare, marchese di, 1738-1794. ... Law reform, Capital punishment, Criminal Law, Crime, Punishment, Capital punishment, Crime, Criminal law, Criminals, Law reform, Punishment Publisher London : Printed for F. Newbery at the corner of St. Paul's Church-yard

An Essay on Crimes and Punishments. information about this edition. sister projects: Wikidata item. Anonymous 1767 English translation of Dei delitti e delle pene (1764). Foundational text of modern criminology. Famous for the Marquis Beccaria's arguments against torture and capital punishment. Mons.

Book digitized by Google from the library of Oxford University and uploaded to the Internet Archive by user tpb.

Home » Books » An essay on crimes and punishments » An essay on crimes and punishments Beccaria, Cesare, marchese di ; Voltaire Printed for Alexander Donaldson, and sold at his shops in London and Edinburgh, 1778

An Essay on Crimes and Punishments Cesare Beccaria Beccaria's book, An Essay on Crimes and Punishments, presents the first of the modern or scientific theories of crime. The book, first pub lished in 1764, became the foundation for the classical theory of criminology, which dominated

Cesare Bonesana di Beccaria, marquis of Gualdasco and Villaregio (1738-94), was the author of On Crimes and Punishments (1764). Inspired by the discussion of criminal law in Montesquieu's Spirit of the Laws, this Milanese wrote a systematic treatise on the subject that was almost immediately translated into English and French.In it, he argued that the sole purpose of punishment is deterrence ...

Cesare Bonesana, Marchese Beccaria, 1738-1794. Originally published in Italian in 1764. Dei delitti e delle pene. English: An essay on crimes and punishments. Written by the Marquis Beccaria, of Milan. With a commentary attributed to Monsieur de Voltaire. Philadelphia: Printed and sold by R. Bell, next door to St. Paul's Church, in Third-Street.

On Crimes and Punishments. Frontpage of the original Italian edition Dei delitti e delle pene. On Crimes and Punishments ( Italian: Dei delitti e delle pene [dei deˈlitti e ddelle ˈpeːne]) is a treatise written by Cesare Beccaria in 1764. The treatise condemned torture and the death penalty and was a founding work in the field of penology .

Other articles where An Essay On Crimes and Punishment is discussed: penology: …of Cesare Beccaria's pamphlet on Crimes and Punishments in 1764. This represented a school of doctrine, born of the new humanitarian impulse of the 18th century, with which Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Voltaire, and Montesquieu in France and Jeremy Bentham in England were associated.

Appears in 14 books from 1768-2004. Page 158 - To show mankind, that crimes are sometimes pardoned, and that punishment is not the necessary consequence, is to nourish the flattering hope of impunity, and is the cause of their considering every punishment inflicted as an act of injustice and oppression. Appears in 31 books from 1800-2004.

Beccaria's On Crimes and Punishments. Cesare Beccaria's views on crime and punishment first took form with a close examination of the law and justice system. The Age of Enlightenment swept through ...

Cesare Beccaria: Essay on Crimes and Punishments . ... The punishment of death is pernicious to society, from the example of barbarity it affords. If the passions, or the necessity of war, have taught men to shed the blood of their fellow creatures, the laws, which are intended to moderate the ferocity of mankind, should not increase it by ...

This essay about Cesare Beccaria's "On Crimes and Punishments" examines the significant impact of the 1764 treatise on the development of modern legal systems. Beccaria's work was groundbreaking in advocating for the principles of just punishment, deterrence over retribution, and the abolition of capital punishment.

Book digitized by Google from the library of the New York Public Library and uploaded to the Internet Archive by user tpb.

An essay on crimes and punishments: Author: Beccaria, Cesare, marchese di, 1738-1794: Author: Voltaire, 1694-1778: Note: Printed for J. Almon, opposite Burlington-House, Piccadilly, 1767 : Link: page images at HathiTrust: No stable link: This is an uncurated book entry from our extended bookshelves, readable online now but without a stable link ...

Here, Beccaria gives voice to a certain rationalistic Enlightenment mentality, writing: "For every crime that comes before him, a judge is required to complete a perfect syllogism in which the major premise must be the general law; the minor, the action that conforms or does not conform to the law; and the conclusion, acquittal or punishment ...

An essay on crimes and punishments translated from the Italian of Cæsar Bonesana, marquis Beccaria by Beccaria, Cesare, marchese di, 1738-1794; Voltaire, 1694 ... Publication date 1819 Topics Crime, Capital punishment, Torture, Punishment, Law reform Publisher Philadelphia : Published by Philip H. Nicklin, No. 175, Chesnut St., A. Walker ...

He perceived a punishment should be: secure, swift and fittingly harsh. By Beccaria being interested in the prevention side of crime, his issue was to get rid of torture by having laws put down in writing and all offences and punishments. Free Essay: Cesare Beccaria was an Italian philosopher who lived throughout the 18th century (1738—1794).

Beccaria's very influential "Dei Delitti e delle Pene" was first published in Livorno in 1764, and the first English translation followed in 1767. Beccaria's book brought into the language the phrase "the greatest happiness of the greatest number" and his arguments about crime and punishment, revolutionary in their time, are part and parcel of ...