Essay on Smoking

500 words essay on smoking.

One of the most common problems we are facing in today’s world which is killing people is smoking. A lot of people pick up this habit because of stress , personal issues and more. In fact, some even begin showing it off. When someone smokes a cigarette, they not only hurt themselves but everyone around them. It has many ill-effects on the human body which we will go through in the essay on smoking.

Ill-Effects of Smoking

Tobacco can have a disastrous impact on our health. Nonetheless, people consume it daily for a long period of time till it’s too late. Nearly one billion people in the whole world smoke. It is a shocking figure as that 1 billion puts millions of people at risk along with themselves.

Cigarettes have a major impact on the lungs. Around a third of all cancer cases happen due to smoking. For instance, it can affect breathing and causes shortness of breath and coughing. Further, it also increases the risk of respiratory tract infection which ultimately reduces the quality of life.

In addition to these serious health consequences, smoking impacts the well-being of a person as well. It alters the sense of smell and taste. Further, it also reduces the ability to perform physical exercises.

It also hampers your physical appearances like giving yellow teeth and aged skin. You also get a greater risk of depression or anxiety . Smoking also affects our relationship with our family, friends and colleagues.

Most importantly, it is also an expensive habit. In other words, it entails heavy financial costs. Even though some people don’t have money to get by, they waste it on cigarettes because of their addiction.

How to Quit Smoking?

There are many ways through which one can quit smoking. The first one is preparing for the day when you will quit. It is not easy to quit a habit abruptly, so set a date to give yourself time to prepare mentally.

Further, you can also use NRTs for your nicotine dependence. They can reduce your craving and withdrawal symptoms. NRTs like skin patches, chewing gums, lozenges, nasal spray and inhalers can help greatly.

Moreover, you can also consider non-nicotine medications. They require a prescription so it is essential to talk to your doctor to get access to it. Most importantly, seek behavioural support. To tackle your dependence on nicotine, it is essential to get counselling services, self-materials or more to get through this phase.

One can also try alternative therapies if they want to try them. There is no harm in trying as long as you are determined to quit smoking. For instance, filters, smoking deterrents, e-cigarettes, acupuncture, cold laser therapy, yoga and more can work for some people.

Always remember that you cannot quit smoking instantly as it will be bad for you as well. Try cutting down on it and then slowly and steadily give it up altogether.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Conclusion of the Essay on Smoking

Thus, if anyone is a slave to cigarettes, it is essential for them to understand that it is never too late to stop smoking. With the help and a good action plan, anyone can quit it for good. Moreover, the benefits will be evident within a few days of quitting.

FAQ of Essay on Smoking

Question 1: What are the effects of smoking?

Answer 1: Smoking has major effects like cancer, heart disease, stroke, lung diseases, diabetes, and more. It also increases the risk for tuberculosis, certain eye diseases, and problems with the immune system .

Question 2: Why should we avoid smoking?

Answer 2: We must avoid smoking as it can lengthen your life expectancy. Moreover, by not smoking, you decrease your risk of disease which includes lung cancer, throat cancer, heart disease, high blood pressure, and more.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 24 March 2022

Tobacco and nicotine use

- Bernard Le Foll 1 , 2 ,

- Megan E. Piper 3 , 4 ,

- Christie D. Fowler 5 ,

- Serena Tonstad 6 ,

- Laura Bierut 7 ,

- Lin Lu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0742-9072 8 , 9 ,

- Prabhat Jha 10 &

- Wayne D. Hall 11 , 12

Nature Reviews Disease Primers volume 8 , Article number: 19 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

35k Accesses

70 Citations

104 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Disease genetics

- Experimental models of disease

- Preventive medicine

Tobacco smoking is a major determinant of preventable morbidity and mortality worldwide. More than a billion people smoke, and without major increases in cessation, at least half will die prematurely from tobacco-related complications. In addition, people who smoke have a significant reduction in their quality of life. Neurobiological findings have identified the mechanisms by which nicotine in tobacco affects the brain reward system and causes addiction. These brain changes contribute to the maintenance of nicotine or tobacco use despite knowledge of its negative consequences, a hallmark of addiction. Effective approaches to screen, prevent and treat tobacco use can be widely implemented to limit tobacco’s effect on individuals and society. The effectiveness of psychosocial and pharmacological interventions in helping people quit smoking has been demonstrated. As the majority of people who smoke ultimately relapse, it is important to enhance the reach of available interventions and to continue to develop novel interventions. These efforts associated with innovative policy regulations (aimed at reducing nicotine content or eliminating tobacco products) have the potential to reduce the prevalence of tobacco and nicotine use and their enormous adverse impact on population health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Distinct µ-opioid ensembles trigger positive and negative fentanyl reinforcement

Adults who microdose psychedelics report health related motivations and lower levels of anxiety and depression compared to non-microdosers

Psilocybin microdosers demonstrate greater observed improvements in mood and mental health at one month relative to non-microdosing controls

Introduction.

Tobacco is the second most commonly used psychoactive substance worldwide, with more than one billion smokers globally 1 . Although smoking prevalence has reduced in many high-income countries (HICs), tobacco use is still very prevalent in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs). The majority of smokers are addicted to nicotine delivered by cigarettes (defined as tobacco dependence in the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) or tobacco use disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5)). As a result of the neuro-adaptations and psychological mechanisms caused by repeated exposure to nicotine delivered rapidly by cigarettes, cessation can also lead to a well-characterized withdrawal syndrome, typically manifesting as irritability, anxiety, low mood, difficulty concentrating, increased appetite, insomnia and restlessness, that contributes to the difficulty in quitting tobacco use 2 , 3 , 4 .

Historically, tobacco was used in some cultures as part of traditional ceremonies, but its use was infrequent and not widely disseminated in the population. However, since the early twentieth century, the use of commercial cigarettes has increased dramatically 5 because of automated manufacturing practices that enable large-scale production of inexpensive products that are heavily promoted by media and advertising. Tobacco use became highly prevalent in the past century and was followed by substantial increases in the prevalence of tobacco-induced diseases decades later 5 . It took decades to establish the relationship between tobacco use and associated health effects 6 , 7 and to discover the addictive role of nicotine in maintaining tobacco smoking 8 , 9 , and also to educate people about these effects. It should be noted that the tobacco industry disputed this evidence to allow continuing tobacco sales 10 . The expansion of public health campaigns to reduce smoking has gradually decreased the use of tobacco in HICs, with marked increases in adult cessation, but less progress has been achieved in LMICs 1 .

Nicotine is the addictive compound in tobacco and is responsible for continued use of tobacco despite harms and a desire to quit, but nicotine is not directly responsible for the harmful effects of using tobacco products (Box 1 ). Other components in tobacco may modulate the addictive potential of tobacco (for example, flavours and non-nicotine compounds) 11 . The major harms related to tobacco use, which are well covered elsewhere 5 , are linked to a multitude of compounds present in tobacco smoke (such as carcinogens, toxicants, particulate matter and carbon monoxide). In adults, adverse health outcomes of tobacco use include cancer in virtually all peripheral organs exposed to tobacco smoke and chronic diseases such as eye disease, periodontal disease, cardiovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis and disorders affecting immune function 5 . Moreover, smoking during pregnancy can increase the risk of adverse reproductive effects, such as ectopic pregnancy, low birthweight and preterm birth 5 . Exposure to secondhand cigarette smoke in children has been linked to sudden infant death syndrome, impaired lung function and respiratory illnesses, in addition to cognitive and behavioural impairments 5 . The long-term developmental effects of nicotine are probably due to structural and functional changes in the brain during this early developmental period 12 , 13 .

Nicotine administered alone in various nicotine replacement formulations (such as patches, gum and lozenges) is safe and effective as an evidence-based smoking cessation aid. Novel forms of nicotine delivery systems have also emerged (called electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) or e-cigarettes), which can potentially reduce the harmful effects of tobacco smoking for those who switch completely from combustible to e-cigarettes 14 , 15 .

This Primer focuses on the determinants of nicotine and tobacco use, and reviews the neurobiology of nicotine effects on the brain reward circuitry and the functioning of brain networks in ways that contribute to the difficulty in stopping smoking. This Primer also discusses how to prevent tobacco use, screen for smoking, and offer people who smoke tobacco psychosocial and pharmacological interventions to assist in quitting. Moreover, this Primer presents emerging pharmacological and novel brain interventions that could improve rates of successful smoking cessation, in addition to public health approaches that could be beneficial.

Box 1 Tobacco products

Conventional tobacco products include combustible products that produce inhaled smoke (most commonly cigarettes, bidis (small domestically manufactured cigarettes used in South Asia) or cigars) and those that deliver nicotine without using combustion (chewing or dipping tobacco and snuff). Newer alternative products that do not involve combustion include nicotine-containing e-cigarettes and heat-not-burn tobacco devices. Although non-combustion and alternative products may constitute a lesser risk than burned ones 14 , 15 , 194 , no form of tobacco is entirely risk-free.

Epidemiology

Prevalence and burden of disease.

The Global Burden of Disease Project (GBDP) estimated that around 1.14 billion people smoked in 2019, worldwide, increasing from just under a billion in 1990 (ref. 1 ). Of note, the prevalence of smoking decreased significantly between 1990 and 2019, but increases in the adult population meant that the total number of global smokers increased. One smoking-associated death occurs for approximately every 0.8–1.1 million cigarettes smoked 16 , suggesting that the estimated worldwide consumption of about 7.4 trillion cigarettes in 2019 has led to around 7 million deaths 1 .

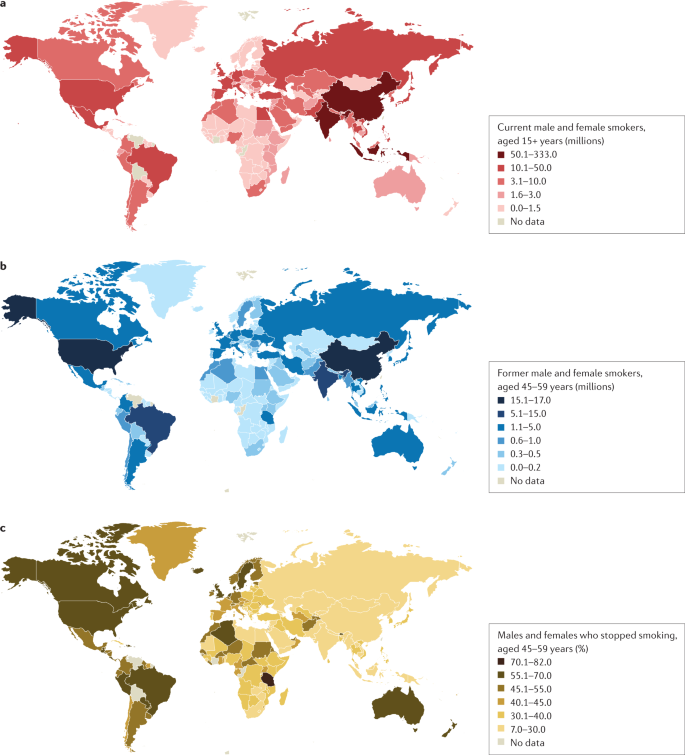

In most populations, smoking prevalence is much higher among groups with lower levels of education or income 17 and among those with mental health disorders and other co-addictions 18 , 19 . Smoking is also more frequent among men than women (Figs 1 – 3 ). Sexual and/or gender minority individuals have disproportionately high rates of smoking and other addictions 17 , 20 . In addition, the prevalence of smoking varies substantially between regions and ethnicities; smoking rates are high in some regions of Asia, such as China and India, but are lower in North America and Australia. Of note, the prevalence of mental health disorders and other co-addictions is higher in individuals who smoke compared with non-smokers 18 , 19 , 21 . For example, the odds of smoking in people with any substance use disorder is more than five times higher than the odds in people without a substance use disorder 19 . Similarly, the odds of smoking in people with any psychiatric disorder is more than three times higher than the odds of smoking in those without a psychiatric diagnosis 22 . In a study in the USA, compared with a population of smokers with no psychiatric diagnosis, subjects with anxiety, depression and phobia showed an approximately twofold higher prevalence of smoking, and subjects with agoraphobia, mania or hypomania, psychosis and antisocial personality or conduct disorders showed at least a threefold higher prevalence of smoking 22 . Comorbid disorders are also associated with higher rates of smoking 22 , 23 .

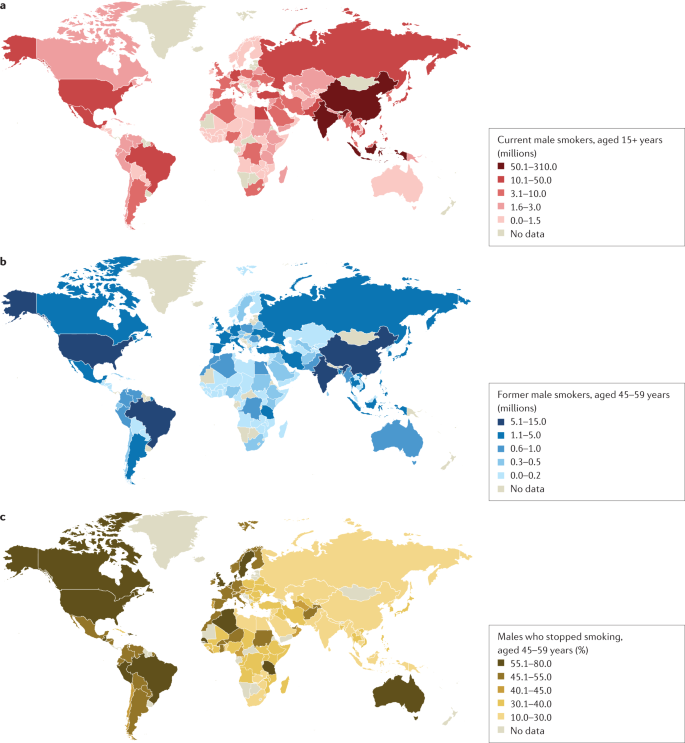

a | Number of current male smokers aged 15 years or older per country expressed in millions. b | Former male smokers aged 45–59 years per country expressed in millions. c | Former male smokers aged 45–59 years per country expressed as the percentage of smokers who stopped. The data shown are for male smokers for the period 2015–2019 from countries with direct smoking surveys. The prevalence of smoking among males is less variable than among females. Data from ref. 1 .

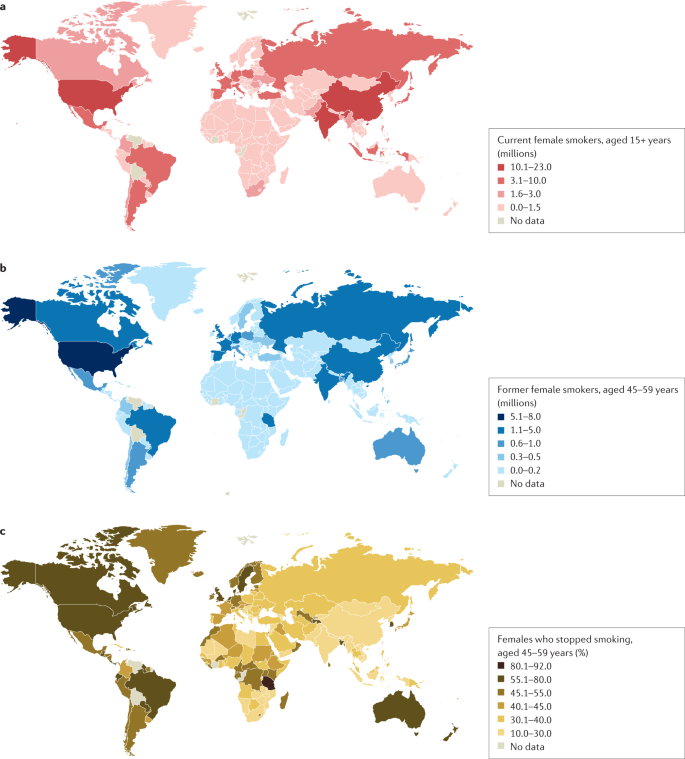

a | Number of current female smokers aged 15 years or older per country expressed in millions. b | Former female smokers aged 45–59 years per country expressed in millions. c | Former female smokers aged 45–59 years per country expressed as the percentage of smokers who stopped. The data shown are for female smokers for the period 2015–2019 from countries with direct smoking surveys. The prevalence of smoking among females is much lower in East and South Asia than in Latin America or Eastern Europe. Data from ref. 1 .

a | Number of current male and female smokers aged 15 years or older per country expressed in millions. b | Former male and female smokers aged 45–59 years per country expressed in millions. c | Former male and female smokers aged 45–59 years per country expressed as the percentage of smokers who stopped. The data shown are for the period 2015–2019 from countries with direct smoking surveys. Cessation rates are higher in high-income countries, but also notably high in Brazil. Cessation is far less common in South and East Asia and Russia and other Eastern European countries, and also low in South Africa. Data from ref. 1 .

Age at onset

Most smokers start smoking during adolescence, with almost 90% of smokers beginning between 15 and 25 years of age 24 . The prevalence of tobacco smoking among youths substantially declined in multiple HICs between 1990 and 2019 (ref. 25 ). More recently, the widespread uptake of ENDS in some regions such as Canada and the USA has raised concerns about the long-term effects of prolonged nicotine use among adolescents, including the possible notion that ENDS will increase the use of combustible smoking products 25 , 26 (although some studies have not found much aggregate effect at the population level) 27 .

Smoking that commences in early adolescence or young adulthood and persists throughout life has a more severe effect on health than smoking that starts later in life and/or that is not persistent 16 , 28 , 29 . Over 640 million adults under 30 years of age smoke in 22 jurisdictions alone (including 27 countries in the European Union where central efforts to reduce tobacco dependence might be possible) 30 . In those younger than 30 years of age, at least 320 million smoking-related deaths will occur unless they quit smoking 31 . The actual number of smoking-related deaths might be greater than one in two, and perhaps as high as two in three, long-term smokers 5 , 16 , 29 , 32 , 33 . At least half of these deaths are likely to occur in middle age (30–69 years) 16 , 29 , leading to a loss of two or more decades of life. People who smoke can expect to lose an average of at least a decade of life versus otherwise similar non-smokers 16 , 28 , 29 .

Direct epidemiological studies in several countries paired with model-based estimates have estimated that smoking tobacco accounted for 7.7 million deaths globally in 2020, of which 80% were in men and 87% were current smokers 1 . In HICs, the major causes of tobacco deaths are lung cancer, emphysema, heart attack, stroke, cancer of the upper aerodigestive areas and bladder cancer 28 , 29 . In some lower income countries, tuberculosis is an additional important cause of tobacco-related death 29 , 34 , which could be related to, for example, increased prevalence of infection, more severe tuberculosis/mortality and higher prevalence of treatment-resistant tuberculosis in smokers than in non-smokers in low-income countries 35 , 36 .

Despite substantial reductions in the prevalence of smoking, there were 34 million smokers in the USA, 7 million in the UK and 5 million in Canada in 2017 (ref. 16 ), and cigarette smoking remains the largest cause of premature death before 70 years of age in much of Europe and North America 1 , 16 , 28 , 29 . Smoking-associated diseases accounted for around 41 million deaths in the USA, UK and Canada from 1960 to 2020 (ref. 16 ). Moreover, as smoking-associated diseases are more prevalent among groups with lower levels of education and income, smoking accounts for at least half of the difference in overall mortality between these social groups 37 . Any reduction in smoking prevalence reduces the absolute mortality gap between these groups 38 .

Smoking cessation has become common in HICs with good tobacco control interventions. For example, in France, the number of ex-smokers is four times the number of current smokers among those aged 50 years or more 30 . By contrast, smoking cessation in LMICs remains uncommon before smokers develop tobacco-related diseases 39 . Smoking cessation greatly reduces the risks of smoking-related diseases. Indeed, smokers who quit smoking before 40 years of age avoid nearly all the increased mortality risks 31 , 33 . Moreover, individuals who quit smoking by 50 years of age reduce the risk of death from lung cancer by about two-thirds 40 . More modest hazards persist for deaths from lung cancer and emphysema 16 , 28 ; however, the risks among former smokers are an order of magnitude lower than among those who continue to smoke 33 .

Mechanisms/pathophysiology

Nicotine is the main psychoactive agent in tobacco and e-cigarettes. Nicotine acts as an agonist at nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), which are localized throughout the brain and peripheral nervous system 41 . nAChRs are pentameric ion channels that consist of varying combinations of α 2 –α 7 and β 2 –β 4 subunits, and for which acetylcholine (ACh) is the endogenous ligand 42 , 43 , 44 . When activated by nicotine binding, nAChR undergoes a conformational change that opens the internal pore, allowing an influx of sodium and calcium ions 45 . At postsynaptic membranes, nAChR activation can lead to action potential firing and downstream modulation of gene expression through calcium-mediated second messenger systems 46 . nAChRs are also localized to presynaptic membranes, where they modulate neurotransmitter release 47 . nAChRs become desensitized after activation, during which ligand binding will not open the channel 45 .

nAChRs with varying combinations of α-subunits and β-subunits have differences in nicotine binding affinity, efficacy and desensitization rate, and have differential expression depending on the brain region and cell type 48 , 49 , 50 . For instance, at nicotine concentrations found in human smokers, β 2 -containing nAChRs desensitize relatively quickly after activation, whereas α 7 -containing nAChRs have a slower desensitization profile 48 . Chronic nicotine exposure in experimental animal models or in humans induces an increase in cortical expression of α 4 β 2 -containing nAChRs 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , but also increases the expression of β 3 and β 4 nAChR subunits in the medial habenula (MHb)–interpeduncular nucleus (IPN) pathway 56 , 57 . It is clear that both the brain localization and the type of nAChR are critical elements in mediating the various effects of nicotine, but other factors such as rate of nicotine delivery may also modulate addictive effects of nicotine 58 .

Neurocircuitry of nicotine addiction

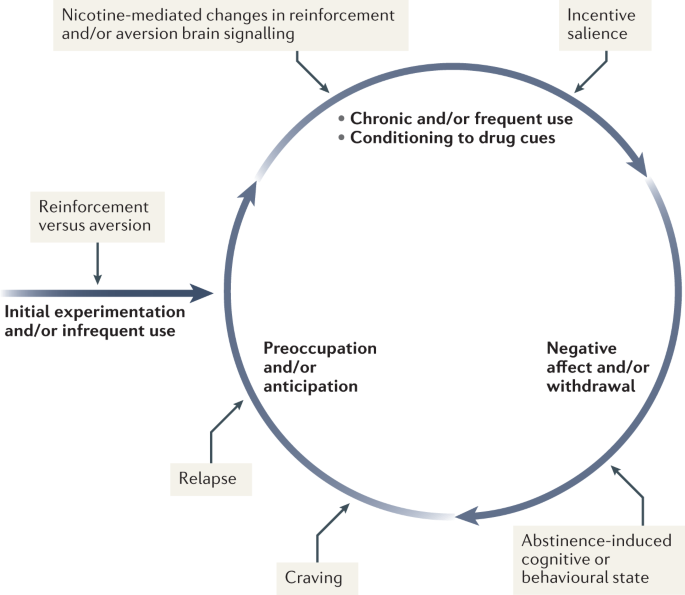

Nicotine has both rewarding effects (such as a ‘buzz’ or ‘high’) and aversive effects (such as nausea and dizziness), with the net outcome dependent on dose and others factors such as interindividual sensitivity and presence of tolerance 59 . Thus, the addictive properties of nicotine involve integration of contrasting signals from multiple brain regions that process reward and aversion (Fig. 4 ).

During initial use, nicotine exerts both reinforcing and aversive effects, which together determine the likelihood of continued use. As the individual transitions to more frequent patterns of chronic use, nicotine induces pharmacodynamic changes in brain circuits, which is thought to lead to a reduction in sensitivity to the aversive properties of the drug. Nicotine is also a powerful reinforcer that leads to the conditioning of secondary cues associated with the drug-taking experience (such as cigarette pack, sensory properties of cigarette smoke and feel of the cigarette in the hand or mouth), which serves to enhance the incentive salience of these environmental factors and drive further drug intake. When the individual enters into states of abstinence (such as daily during sleep at night or during quit attempts), withdrawal symptomology is experienced, which may include irritability, restlessness, learning or memory deficits, difficulty concentrating, anxiety and hunger. These negative affective and cognitive symptoms lead to an intensification of the individual’s preoccupation to obtain and use the tobacco/nicotine product, and subsequently such intense craving can lead to relapse.

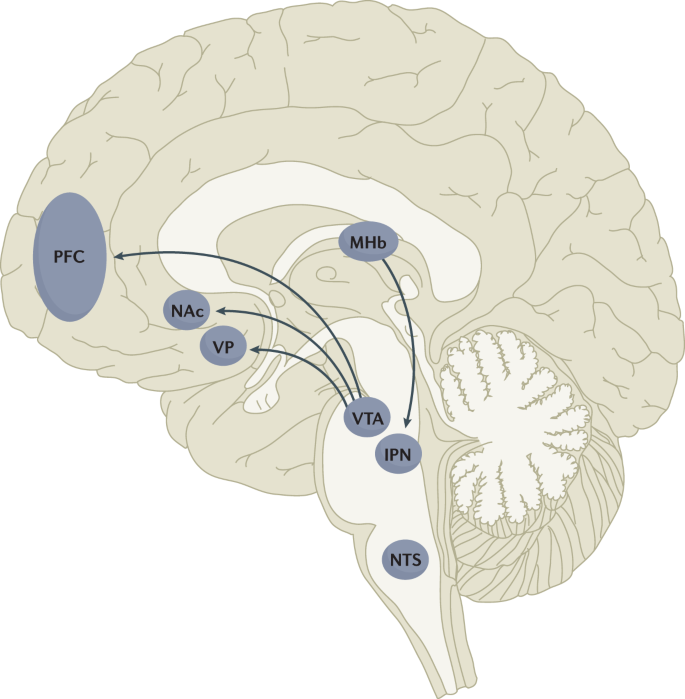

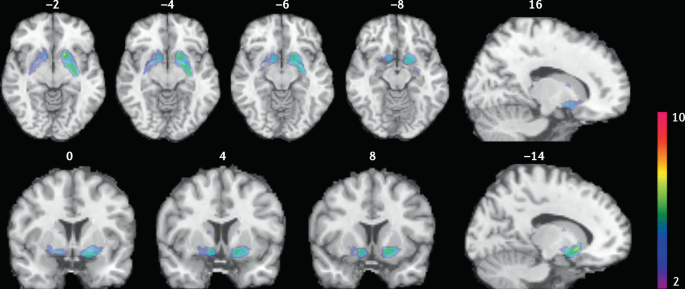

The rewarding actions of nicotine have largely been attributed to the mesolimbic pathway, which consists of dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) that project to the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex 60 , 61 , 62 (Fig. 5 ). VTA integrating circuits and projection regions express several nAChR subtypes on dopaminergic, GABAergic, and glutamatergic neurons 63 , 64 . Ultimately, administration of nicotine increases dopamine levels through increased dopaminergic neuron firing in striatal and extrastriatal areas (such as the ventral pallidum) 65 (Fig. 6 ). This effect is involved in reward and is believed to be primarily mediated by the action of nicotine on α 4 -containing and β 2 -containing nAChRs in the VTA 66 , 67 .

Multiple lines of research have demonstrated that nicotine reinforcement is mainly controlled by two brain pathways, which relay predominantly reward-related or aversion-related signals. The rewarding properties of nicotine that promote drug intake involve the mesolimbic dopamine projection from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the nucleus accumbens (NAc). By contrast, the aversive properties of nicotine that limit drug intake and mitigate withdrawal symptoms involve the fasciculus retroflexus projection from the medial habenula (MHb) to the interpeduncular nucleus (IPN). Additional brain regions have also been implicated in various aspects of nicotine dependence, such as the prefrontal cortex (PFC), ventral pallidum (VP), nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) and insula (not shown here for clarity). All of these brain regions are directly or indirectly interconnected as integrative circuits to drive drug-seeking and drug-taking behaviours.

Smokers received brain PET scans with [ 11 C]PHNO, a dopamine D 2/3 PET tracer that has high sensitivity in detecting fluctuations of dopamine. PET scans were performed during abstinence or after smoking a cigarette. Reduced binding potential (BP ND ) was observed after smoking, indicating increased dopamine levels in the ventral striatum and in the area that corresponds to the ventral pallidum. The images show clusters with statistically significant decreases of [ 11 C]PHNO BP ND after smoking a cigarette versus abstinence condition. Those clusters have been superimposed on structural T1 MRI images of the brain. Reprinted from ref. 65 , Springer Nature Limited.

The aversive properties of nicotine are mediated by neurons in the MHb, which project to the IPN. Studies in rodents using genetic knockdown and knockout strategies demonstrated that the α 5 -containing, α 3 -containing and β 4 -containing nAChRs in the MHb–IPN pathway mediate the aversive properties of nicotine that limit drug intake, especially when animals are given the opportunity to consume higher nicotine doses 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 . In addition to nAChRs, other signalling factors acting on the MHb terminals in the IPN also regulate the actions of nicotine. For instance, under conditions of chronic nicotine exposure or with optogenetic activation of IPN neurons, a subtype of IPN neurons co-expressing Chrna5 (encoding the α 5 nAChR subunit) and Amigo1 (encoding adhesion molecule with immunoglobulin-like domain 1) release nitric oxide from the cell body that retrogradely inhibits MHb axon terminals 70 . In addition, nicotine activates α 5 -containing nAChR-expressing neurons that project from the nucleus tractus solitarius to the IPN, leading to release of glucagon-like peptide-1 that binds to GLP receptors on habenular axon terminals, which subsequently increases IPN neuron activation and decreases nicotine self-administration 73 . Taken together, these findings suggest a dynamic signalling process at MHb axonal terminals in the IPN, which regulates the addictive properties of nicotine and determines the amount of nicotine that is self-administered.

Nicotine withdrawal in animal models can be assessed by examining somatic signs (such as shaking, scratching, head nods and chewing) and affective signs (such as increased anxiety-related behaviours and conditioned place aversion). Interestingly, few nicotine withdrawal somatic signs are found in mice with genetic knockout of the α 2 , α 5 or β 4 nAChR subunits 74 , 75 . By contrast, β 2 nAChR-knockout mice have fewer anxiety-related behaviours during nicotine withdrawal, with no differences in somatic symptoms compared with wild-type mice 74 , 76 .

In addition to the VTA (mediating reward) and the MHb–IPN pathway (mediating aversion), other brain areas are involved in nicotine addiction (Fig. 5 ). In animals, the insular cortex controls nicotine taking and nicotine seeking 77 . Moreover, humans with lesions of the insular cortex can quit smoking easily without relapse 78 . This finding led to the development of a novel therapeutic intervention modulating insula function (see Management, below) 79 , 80 . Various brain areas (shell of nucleus accumbens, basolateral amygdala and prelimbic cortex) expressing cannabinoid CB 1 receptors are also critical in controlling rewarding effects and relapse 81 , 82 . The α 1 -adrenergic receptor expressed in the cortex also control these effects, probably through glutamatergic afferents to the nucleus accumbens 83 .

Individual differences in nicotine addiction risk

Vulnerability to nicotine dependence varies between individuals, and the reasons for these differences are multidimensional. Many social factors (such as education level and income) play a role 84 . Broad psychological and social factors also modulate this risk. For example, peer smoking status, knowledge on effect of tobacco, expectation on social acceptance, exposure to passive smoking modulate the risk of initiating tobacco use 85 , 86 .

Genetic factors have a role in smoking initiation, the development of nicotine addiction and the likelihood of smoking cessation. Indeed, heritability has been estimated to contribute to approximatively half of the variability in nicotine dependence 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 . Important advances in our understanding of such genetic contributions have evolved with large-scale genome-wide association studies of smokers and non-smokers. One of the most striking findings has been that allelic variation in the CHRNA5 – CHRNA3 – CHRNB4 gene cluster, which encodes α 5 , α 3 and β 4 nAChR subunits, correlates with an increased vulnerability for nicotine addiction, indicated by a higher likelihood of becoming dependent on nicotine and smoking a greater number of cigarettes per day 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 . The most significant effect has been found for a single-nucleotide polymorphism in CHRNA5 (rs16969968), which results in an amino acid change and reduced function of α 5 -containing nAChRs 92 .

Allelic variation in CYP2A6 (encoding the CYP2A6 enzyme, which metabolizes nicotine) has also been associated with differential vulnerability to nicotine dependence 96 , 97 , 98 . CYP2A6 is highly polymorphic, resulting in variable enzymatic activity 96 , 99 , 100 . Individuals with allelic variation that results in slow nicotine metabolism consume less nicotine per day, experience less-severe withdrawal symptoms and are more successful at quitting smoking than individuals with normal or fast metabolism 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 . Moreover, individuals with slow nicotine metabolism have lower dopaminergic receptor expression in the dopamine D2 regions of the associative striatum and sensorimotor striatum in PET studies 105 and take fewer puffs of nicotine-containing cigarettes (compared with de-nicotinized cigarettes) in a forced choice task 106 . Slower nicotine metabolism is thought to increase the duration of action of nicotine, allowing nicotine levels to accumulate over time, therefore enabling lower levels of intake to sustain activation of nAChRs 107 .

Large-scale genetic studies have identified hundreds of other genetic loci that influence smoking initiation, age of smoking initiation, cigarettes smoked per day and successful smoking cessation 108 . The strongest genetic contributions to smoking through the nicotinic receptors and nicotine metabolism are among the strongest genetic contributors to lung cancer 109 . Other genetic variations (such as those related to cannabinoid, dopamine receptors or other neurotransmitters) may affect certain phenotypes related to smoking (such as nicotine preference and cue-reactivity) 110 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 .

Diagnosis, screening and prevention

Screening for cigarette smoking.

Screening for cigarette smoking should happen at every doctor’s visit 116 . In this regard, a simple and direct question about a person’s tobacco use can provide an opportunity to offer information about its potential risks and treatments to assist in quitting. All smokers should be offered assistance in quitting because even low levels of smoking present a significant health risk 33 , 117 , 118 . Smoking status can be assessed by self-categorization or self-reported assessment of smoking behaviour (Table 1 ). In people who smoke, smoking frequency can be assessed 119 and a combined quantity frequency measure such as pack-year history (that is, average number of cigarettes smoked per day multiplied by the number of years, divided by 20), can be used to estimate cumulative risk of adverse health outcomes. The Association for the Treatment of Tobacco Use and Dependence recommends that all electronic health records should document smoking status using the self-report categories listed in Table 1 .

Owing to the advent of e-cigarettes and heat-not-burn products, and the popularity of little cigars in the US that mimic combustible cigarettes, people who use tobacco may use multiple products concurrently 120 , 121 . Thus, screening for other nicotine and tobacco product use is important in clinical practice. The self-categorization approach can also be used to describe the use of these other products.

Traditionally tobacco use has been classified according to whether the smoker meets criteria for nicotine dependence in one of the two main diagnostic classifications: the DSM 122 (tobacco use disorder) and the ICD (tobacco dependence) 123 . The diagnosis of tobacco use disorder according to DSM-5 criteria requires the presence of at least 2 of 11 symptoms that have produced marked clinical impairment or distress within a 12-month period (Box 2 ). Of note, these symptoms are similar for all substance use disorder diagnoses and may not all be relevant to tobacco use disorder (such as failure to complete life roles). In the ICD-10, codes allow the identification of specific tobacco products used (cigarettes, chewing tobacco and other tobacco products).

Dependence can also be assessed as a continuous construct associated with higher levels of use, greater withdrawal and reduced likelihood of quitting. The level of dependence can be assessed with the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, a short questionnaire comprising six questions 124 (Box 2 ). A score of ≥4 indicates moderate to high dependence. As very limited time may be available in clinical consultations, the Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI) was developed, which comprises two questions on the number of cigarettes smoked per day and how soon after waking the first cigarette is smoked 125 . The HSI can guide dosing for nicotine replacement therapy (NRT).

Other measures of cigarette dependence have been developed but are not used in the clinical setting, such as the Cigarette Dependence Scale 126 , Hooked on Nicotine Checklist 127 , Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale 128 , the Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (Brief) 129 and the Penn State Cigarette Dependence Index 130 . However, in practice, these are not often used, as the most important aspect is to screen for smoking and encourage all smokers to quit smoking regardless of their dependence status.

Box 2 DSM-5 criteria for tobacco use disorder and items of the Fagerström Test for nicotine dependence

DSM-5 (ref. 122 )

Taxonomic and diagnostic tool for tobacco use disorder published by the American Psychiatric Association.

A problematic pattern of tobacco use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress as manifested by at least two of the following, occurring within a 12-month period.

Tobacco often used in larger amounts or over a longer period of time than intended

A persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to reduce or control tobacco use

A great deal of time spent in activities necessary to obtain or use tobacco

Craving, or a strong desire or urge to use tobacco

Recurrent tobacco use resulting in a failure to fulfil major role obligations at work, school or home

Continued tobacco use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of tobacco (for example, arguments with others about tobacco use)

Important social, occupational or recreational activities given up or reduced because of tobacco use

Recurrent tobacco use in hazardous situations (such as smoking in bed)

Tobacco use continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by tobacco use

Tolerance, defined by either of the following.

A need for markedly increased amounts of tobacco to achieve the desired effect

A markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of tobacco

Withdrawal, manifesting as either of the following.

Withdrawal syndrome for tobacco

Tobacco (or a closely related substance, such as nicotine) taken to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms

Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence 124

A standard instrument for assessing the intensity of physical addiction to nicotine.

How soon after you wake up do you smoke your first cigarette?

Within 5 min (scores 3 points)

5 to 30 min (scores 2 points)

31 to 60 min (scores 1 point)

After 60 min (scores 0 points)

Do you find it difficult not to smoke in places where you should not, such as in church or school, in a movie, at the library, on a bus, in court or in a hospital?

Yes (scores 1 point)

No (scores 0 points)

Which cigarette would you most hate to give up; which cigarette do you treasure the most?

The first one in the morning (scores 1 point)

Any other one (scores 0 points)

How many cigarettes do you smoke each day?

10 or fewer (scores 0 points)

11 to 20 (scores 1 point)

21 to 30 (scores 2 points)

31 or more (scores 3 points)

Do you smoke more during the first few hours after waking up than during the rest of the day?

Do you still smoke if you are so sick that you are in bed most of the day or if you have a cold or the flu and have trouble breathing?

A score of 7–10 points is classified as highly dependent; 4–6 points is classified as moderately dependent; <4 points is classified as minimally dependent.

DSM-5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition.

Young people who do not start smoking cigarettes between 15 and 25 years of age have a very low risk of ever smoking 24 , 131 , 132 . This age group provides a critical opportunity to prevent cigarette smoking using effective, evidence-based strategies to prevent smoking initiation and reduce escalation from experimentation to regular use 131 , 132 , 133 , 134 , 135 .

Effective prevention of cigarette uptake requires a comprehensive package of cost-effective policies 134 , 136 , 137 to synergistically reduce the population prevalence of cigarette smoking 131 , 135 . These policies include high rates of tobacco taxation 30 , 134 , 137 , 138 , widespread and rigorously enforced smoke-free policies 139 , bans on tobacco advertising and promotions 140 , use of plain packaging and graphic warnings about the health risks of smoking 135 , 141 , mass media and peer-based education programmes to discourage smoking, and enforcement of laws against the sale of cigarettes to young people below the minimum legal purchase age 131 , 135 . These policies make cigarettes less available and affordable to young people. Moreover, these policies make it more difficult for young people to purchase cigarettes and make smoking a much less socially acceptable practice. Of note, these policies are typically mostly enacted in HICs, which may be related to the declining prevalence of smoking in these countries, compared with the prevalence in LMICs.

Pharmacotherapy

Three evidence-based classes of pharmacotherapy are available for smoking cessation: NRT (using nicotine-based patches, gum, lozenges, mini-lozenges, nasal sprays and inhalers), varenicline (a nAChR partial agonist), and bupropion (a noradrenaline/dopamine reuptake inhibitor that also inhibits nAChR function and is also used as an antidepressant). These FDA-approved and EMA-approved pharmacotherapies are cost-effective smoking cessation treatments that double or triple successful abstinence rates compared with no treatment or placebo controls 116 , 142 .

Combinations of pharmacotherapies are also effective for smoking cessation 116 , 142 . For example, combining NRTs (such as the steady-state nicotine patch and as-needed NRT such as gum or mini-lozenge) is more effective than a single form of NRT 116 , 142 , 143 . Combining NRT and varenicline is the most effective smoking cessation pharmacotherapy 116 , 142 , 143 . Combining FDA-approved pharmacotherapy with behavioural counselling further increases the likelihood of successful cessation 142 . Second-line pharmacotherapies (for example, nortriptyline) have some potential for smoking cessation, but their use is limited due to their tolerability profile.

All smokers should receive pharmacotherapy to help them quit smoking, except those in whom pharmacotherapy has insufficient evidence of effectiveness (among adolescents, smokeless tobacco users, pregnant women or light smokers) or those in whom pharmacotherapy is medically contraindicated 144 . Table 2 provides specific information regarding dosing and duration for each FDA-approved pharmacotherapy. Extended use of pharmacotherapy beyond the standard 12-week regimen after cessation is effective and should be considered 116 . Moreover, preloading pharmacotherapy (that is, initiating cessation medication in advance of a quit attempt), especially with the nicotine patch, is a promising treatment, although further studies are required to confirm efficacy.

Cytisine has been used for smoking cessation in Eastern Europe for a long time and is available in some countries (such as Canada) without prescription 145 . Cytisine is a partial agonist of nAChRs and its structure was the precursor for the development of varenicline 145 . Cytisine is at least as effective as some approved pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation, such as NRT 146 , 147 , 148 , and the role of cytisine in smoking cessation is likely to expand in the future, notably owing to its much lower cost than traditional pharmacotherapies. E-cigarettes also have the potential to be useful as smoking cessation devices 149 , 150 . The 2020 US Surgeon General’s Report concluded that there was insufficient evidence to promote cytisine or e-cigarettes as effective smoking cessation treatments, but in the UK its use is recommended for smoking cessation (see ref. 15 for regularly updated review).

Counselling and behavioural treatments

Psychosocial counselling significantly increases the likelihood of successful cessation, especially when combined with pharmacotherapy. Even a counselling session lasting only 3 minutes can help smokers quit 116 , although the 2008 US Public Health Service guidelines and the Preventive Services Task Force 151 each concluded that more intensive counselling (≥20 min per session) is more effective than less intensive counselling (<20 min per session). Higher smoking cessation rates are obtained by using behavioural change techniques that target associative and self-regulatory processes 152 . In addition, behavioural change techniques that will favour commitment, social reward and identity associated with changed behaviour seems associated with higher success rates 152 . Evidence-based counselling focuses on providing social support during treatment, building skills to cope with withdrawal and cessation, and problem-solving in challenging situations 116 , 153 . Effective counselling can be delivered by diverse providers (such as physicians, nurses, pharmacists, social workers, psychologists and certified tobacco treatment specialists) 116 .

Counselling can be delivered in a variety of modalities. In-person individual and group counselling are effective, as is telephone counselling (quit lines) 142 . Internet and text-based intervention seem to be effective in smoking cessation, especially when they are interactive and tailored to a smoker’s specific circumstances 142 . Over the past several years, the number of smoking cessation smartphone apps has increased, but there the evidence that the use of these apps significantly increases smoking cessation rates is not sufficient.

Contingency management (providing financial incentives for abstinence or engagement in treatment) has shown promising results 154 , 155 but its effects are not sustained once the contingencies are removed 155 , 156 . Other treatments such as hypnosis, acupuncture and laser treatment have not been shown to improve smoking cessation rates compared with placebo treatments 116 . Moreover, no solid evidence supports the use of conventional transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for long-term smoking cessation 157 , 158 .

Although a variety of empirically supported smoking cessation interventions are available, more than two-thirds of adult smokers who made quit attempts in the USA during the past year did not use an evidence-based treatment and the rate is likely to be lower in many other countries 142 . This speaks to the need to increase awareness of, and access to, effective cessation aids among all smokers.

Brain stimulation

The insula (part of the frontal cortex) is a critical brain structure involved in cigarette craving and relapse 78 , 79 . The activity of the insula can be modulated using an innovative approach called deep insula/prefrontal cortex TMS (deep TMS), which is effective in helping people quit smoking 80 , 159 . This approach has now been approved by the FDA as an effective smoking cessation intervention 80 . However, although this intervention was developed and is effective for smoking cessation, the number of people with access to it is limited owing to the limited number of sites equipped and with trained personnel, and the cost of this intervention.

Quality of life

Generic instruments (such as the Short-Form (SF-36) Health Survey) can be used to evaluate quality of life (QOL) in smokers. People who smoke rate their QOL lower than people who do not smoke both before and after they become smokers 160 , 161 . QOL improves when smokers quit 162 . Mental health may also improve on quitting smoking 163 . Moreover, QOL is much poorer in smokers with tobacco-related diseases, such as chronic respiratory diseases and cancers, than in individuals without tobacco-related diseases 161 , 164 . The dimensions of QOL that show the largest decrements in people who smoke are those related to physical health, day-to-day activities and mental health such as depression 160 . Smoking also increases the risk of diabetes mellitus 165 , 166 , which is a major determinant of poor QOL for a wide range of conditions.

The high toll of premature death from cigarette smoking can obscure the fact that many of the diseases that cause these deaths also produce substantial disability in the years before death 1 . Indeed, death in smokers is typically preceded by several years of living with the serious disability and impairment of everyday activities caused by chronic respiratory disease, heart disease and cancer 2 . Smokers’ QOL in these years may also be adversely affected by the adverse effects of the medical treatments that they receive for these smoking-related diseases (such as major surgery and radiotherapy).

Expanding cessation worldwide

The major global challenge is to consider individual and population-based strategies that could increase the substantially low rates of adult cessation in most LMICs and indeed strategies to ensure that even in HICs, cessation continues to increase. In general, the most effective tools recommended by WHO to expand cessation are the same tools that can prevent smoking initiation, notably higher tobacco taxes, bans on advertising and promotion, prominent warning labels or plain packaging, bans on public smoking, and mass media and educational efforts 29 , 167 . The effective use of these policies, particularly taxation, lags behind in most LMICs compared with most HICs, with important exceptions such as Brazil 167 . Access to effective pharmacotherapies and counselling as well as support for co-existing mental health conditions would also be required to accelerate cessation in LMICs. This is particularly important as smokers living in LMICs often have no access to the full range of effective treatment options.

Regulating access to e-cigarettes

How e-cigarettes should be used is debated within the tobacco control field. In some countries (for example, the UK), the use of e-cigarettes as a cigarette smoking cessation aid and as a harm reduction strategy is supported, based on the idea that e-cigarette use will lead to much less exposure to toxic compounds than tobacco use, therefore reducing global harm. In other countries (for example, the USA), there is more concern with preventing the increased use of e-cigarettes by youths that may subsequently lead to smoking 25 , 26 . Regulating e-cigarettes in nuanced ways that enable smokers to access those products whilst preventing their uptake among youths is critical.

Regulating nicotine content in tobacco products

Reducing the nicotine content of cigarettes could potentially produce less addictive products that would allow a gradual reduction in the population prevalence of smoking. Some clinical studies have found no compensatory increase in smoking whilst providing access to low nicotine tobacco 168 . Future regulation may be implemented to gradually decrease the nicotine content of combustible tobacco and other nicotine products 169 , 170 , 171 .

Tobacco end games

Some individuals have proposed getting rid of commercial tobacco products this century or using the major economic disruption arising from the COVID-19 pandemic to accelerate the demise of the tobacco industry 172 , 173 . Some tobacco producers have even proposed this strategy as an internal goal, with the idea of switching to nicotine delivery systems that are less harmful ( Philip Morris International ). Some countries are moving towards such an objective; for example, in New Zealand, the goal that fewer than 5% of New Zealanders will be smokers in 2025 has been set (ref. 174 ). The tobacco end-game approach would overall be the best approach to reduce the burden of tobacco use on society, but it would require coordination of multiple countries and strong public and private consensus on the strategy to avoid a major expansion of the existing illicit market in tobacco products in some countries.

Innovative interventions

The COVID-19 pandemic has shown that large-scale investment in research can lead to rapid development of successful therapeutic interventions. By contrast, smoking cessation has been underfunded compared with the contribution that it makes to the global burden of disease. In addition, there is limited coordination between research teams and most studies are small-scale and often underpowered 79 . It is time to fund an ambitious, coordinated programme of research to test the most promising therapies based on an increased understanding of the neurobiological basis of smoking and nicotine addiction (Table 3 ). Many of those ideas have not yet been tested properly and this could be carried out by a coordinated programme of research at the international level.

GBD 2019 Tobacco Collaborators. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 397 , 2337–2360 (2021). This study summarizes the burden of disease induced by tobacco worldwide .

Google Scholar

West, R. Tobacco smoking: health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychol. Health 32 , 1018–1036 (2017).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

West, R. The multiple facets of cigarette addiction and what they mean for encouraging and helping smokers to stop. COPD 6 , 277–283 (2009).

PubMed Google Scholar

Fagerström, K. Determinants of tobacco use and renaming the FTND to the Fagerström test for cigarette dependence. Nicotine Tob. Res. 14 , 75–78 (2012).

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. The Health Consequences of Smoking: 50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014).

Doll, R. & Hill, A. B. Smoking and carcinoma of the lung; preliminary report. Br. Med. J. 2 , 739–748 (1950).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Royal College of Physicians. Smoking and health. Summary of a report of the Royal College of Physicians of London on smoking in relation to cancer of the lung and other diseases (Pitman Medical Publishing, 1962).

Henningfield, J. E., Smith, T. T., Kleykamp, B. A., Fant, R. V. & Donny, E. C. Nicotine self-administration research: the legacy of Steven R. Goldberg and implications for regulation, health policy, and research. Psychopharmacology 233 , 3829–3848 (2016).

Le Foll, B. & Goldberg, S. R. Effects of nicotine in experimental animals and humans: an update on addictive properties. Hand. Exp. Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-69248-5_12 (2009).

Article Google Scholar

Proctor, R. N. The history of the discovery of the cigarette–lung cancer link: evidentiary traditions, corporate denial, global toll. Tob. Control. 21 , 87–91 (2012).

Hall, B. J. et al. Differential effects of non-nicotine tobacco constituent compounds on nicotine self-administration in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 120 , 103–108 (2014).

Musso, F. et al. Smoking impacts on prefrontal attentional network function in young adult brains. Psychopharmacology 191 , 159–169 (2007).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Goriounova, N. A. & Mansvelder, H. D. Short- and long-term consequences of nicotine exposure during adolescence for prefrontal cortex neuronal network function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2 , a012120 (2012).

Fagerström, K. O. & Bridgman, K. Tobacco harm reduction: the need for new products that can compete with cigarettes. Addictive Behav. 39 , 507–511 (2014).

Hartmann-Boyce, J. et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9 , CD010216 (2021).

Jha, P. The hazards of smoking and the benefits of cessation: a critical summation of the epidemiological evidence in high-income countries. eLife https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49979 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Palipudi, K. M. et al. Social determinants of health and tobacco use in thirteen low and middle income countries: evidence from Global Adult Tobacco Survey. PLoS ONE 7 , e33466 (2012).

Goodwin, R. D., Pagura, J., Spiwak, R., Lemeshow, A. R. & Sareen, J. Predictors of persistent nicotine dependence among adults in the United States. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 118 , 127–133 (2011).

Weinberger, A. H. et al. Cigarette use is increasing among people with illicit substance use disorders in the United States, 2002-14: emerging disparities in vulnerable populations. Addiction 113 , 719–728 (2018).

Evans-Polce, R. J., Kcomt, L., Veliz, P. T., Boyd, C. J. & McCabe, S. E. Alcohol, tobacco, and comorbid psychiatric disorders and associations with sexual identity and stress-related correlates. Am. J. Psychiatry 177 , 1073–1081 (2020).

Hassan, A. N. & Le Foll, B. Survival probabilities and predictors of major depressive episode incidence among individuals with various types of substance use disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.20m13637 (2021).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Smith, P. H., Mazure, C. M. & McKee, S. A. Smoking and mental illness in the U.S. population. Tob. Control. 23 , e147–e153 (2014).

Bourgault, Z., Rubin-Kahana, D. S., Hassan, A. N., Sanches, M. & Le Foll, B. Multiple substance use disorders and self-reported cognitive function in U.S. adults: associations and sex-differences in a nationally representative sample. Front. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.797578 (2022).

Reitsma, M. B. et al. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and initiation among young people in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019. Lancet Public Health 6 , e472–e481 (2021).

Warner, K. E. How to think–not feel–about tobacco harm reduction. Nicotine Tob. Res. 21 , 1299–1309 (2019).

Soneji, S. et al. Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 171 , 788–797 (2017).

Levy, D. T. et al. Examining the relationship of vaping to smoking initiation among US youth and young adults: a reality check. Tob. Control. 28 , 629–635 (2019).

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. The health consequences of smoking — 50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014).

Jha, P. & Peto, R. Global effects of smoking, of quitting, and of taxing tobacco. N. Engl. J. Med. 370 , 60–68 (2014). This review covers the impact of tobacco, of quitting smoking and the importance of taxation to impact prevalence of smoking .

Jha, P. & Peto., R. in Tobacco Tax Reform: At the Crossroads of Health and Development . (eds Marquez, P. V. & Moreno-Dodson, B.) 55–72 (World Bank Group, 2017).

Jha, P. et al. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 368 , 341–350 (2013).

Banks, E. et al. Tobacco smoking and all-cause mortality in a large Australian cohort study: findings from a mature epidemic with current low smoking prevalence. BMC Med. 13 , 38 (2015).

Pirie, K. et al. The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: a prospective study of one million women in the UK. Lancet 381 , 133–141 (2013).

Jha, P. et al. A nationally representative case-control study of smoking and death in India. N. Engl. J. Med. 358 , 1137–1147 (2008).

Chan, E. D. et al. Tobacco exposure and susceptibility to tuberculosis: is there a smoking gun? Tuberculosis 94 , 544–550 (2014).

Wang, M. G. et al. Association between tobacco smoking and drug-resistant tuberculosis. Infect. Drug Resist. 11 , 873–887 (2018).

Jha, P. et al. Social inequalities in male mortality, and in male mortality from smoking: indirect estimation from national death rates in England and Wales, Poland, and North America. Lancet 368 , 367–370 (2006).

Jha, P., Gelband, H, Irving, H. & Mishra, S. in Reducing Social Inequalities in Cancer: Evidence and Priorities for Research (eds Vaccarella, S et al.) 161–166 (IARC, 2018).

Jha, P. Expanding smoking cessation world-wide. Addiction 113 , 1392–1393 (2018).

Jha, P. Avoidable global cancer deaths and total deaths from smoking. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9 , 655–664 (2009).

Wittenberg, R. E., Wolfman, S. L., De Biasi, M. & Dani, J. A. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotine addiction: a brief introduction. Neuropharmacology 177 , 108256 (2020).

Boulter, J. et al. Functional expression of two neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors from cDNA clones identifies a gene family. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 84 , 7763–7767 (1987).

Couturier, S. et al. A neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit (α7) is developmentally regulated and forms a homo-oligomeric channel blocked by α-BTX. Neuron 5 , 847–856 (1990).

Picciotto, M. R., Addy, N. A., Mineur, Y. S. & Brunzell, D. H. It is not “either/or”: activation and desensitization of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors both contribute to behaviors related to nicotine addiction and mood. Prog. Neurobiol. 84 , 329–342 (2008).

Changeux, J. P. Structural identification of the nicotinic receptor ion channel. Trends Neurosci. 41 , 67–70 (2018).

McKay, B. E., Placzek, A. N. & Dani, J. A. Regulation of synaptic transmission and plasticity by neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 74 , 1120–1133 (2007).

Wonnacott, S. Presynaptic nicotinic ACh receptors. Trends Neurosci. 20 , 92–98 (1997).

Wooltorton, J. R., Pidoplichko, V. I., Broide, R. S. & Dani, J. A. Differential desensitization and distribution of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes in midbrain dopamine areas. J. Neurosci. 23 , 3176–3185 (2003).

Gipson, C. D. & Fowler, C. D. Nicotinic receptors underlying nicotine dependence: evidence from transgenic mouse models. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 45 , 101–121 (2020).

Hamouda, A. K. et al. Potentiation of (α4)2(β2)3, but not (α4)3(β2)2, nicotinic acetylcholine receptors reduces nicotine self-administration and withdrawal symptoms. Neuropharmacology 190 , 108568 (2021).

Lallai, V. et al. Nicotine acts on cholinergic signaling mechanisms to directly modulate choroid plexus function. eNeuro https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0051-19.2019 (2019).

Benwell, M. E., Balfour, D. J. & Anderson, J. M. Evidence that tobacco smoking increases the density of (-)-[3H]nicotine binding sites in human brain. J. Neurochem. 50 , 1243–1247 (1988).

Perry, D. C., Davila-Garcia, M. I., Stockmeier, C. A. & Kellar, K. J. Increased nicotinic receptors in brains from smokers: membrane binding and autoradiography studies. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 289 , 1545–1552 (1999).

Marks, M. J. et al. Nicotine binding and nicotinic receptor subunit RNA after chronic nicotine treatment. J. Neurosci. 12 , 2765–2784 (1992).

Le Foll, B. et al. Impact of short access nicotine self-administration on expression of α4β2* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in non-human primates. Psychopharmacology 233 , 1829–1835 (2016).

Meyers, E. E., Loetz, E. C. & Marks, M. J. Differential expression of the beta4 neuronal nicotinic receptor subunit affects tolerance development and nicotinic binding sites following chronic nicotine treatment. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 130 , 1–8 (2015).

Zhao-Shea, R., Liu, L., Pang, X., Gardner, P. D. & Tapper, A. R. Activation of GABAergic neurons in the interpeduncular nucleus triggers physical nicotine withdrawal symptoms. Curr. Biol. 23 , 2327–2335 (2013).

Jensen, K. P., Valentine, G., Gueorguieva, R. & Sofuoglu, M. Differential effects of nicotine delivery rate on subjective drug effects, urges to smoke, heart rate and blood pressure in tobacco smokers. Psychopharmacology 237 , 1359–1369 (2020).

Villanueva, H. F., James, J. R. & Rosecrans, J. A. Evidence of pharmacological tolerance to nicotine. NIDA Res. Monogr. 95 , 349–350 (1989).

Corrigall, W. A., Coen, K. M. & Adamson, K. L. Self-administered nicotine activates the mesolimbic dopamine system through the ventral tegmental area. Brain Res. 653 , 278–284 (1994).

Nisell, M., Nomikos, G. G., Hertel, P., Panagis, G. & Svensson, T. H. Condition-independent sensitization of locomotor stimulation and mesocortical dopamine release following chronic nicotine treatment in the rat. Synapse 22 , 369–381 (1996).

Rice, M. E. & Cragg, S. J. Nicotine amplifies reward-related dopamine signals in striatum. Nat. Neurosci. 7 , 583–584 (2004).

Mameli-Engvall, M. et al. Hierarchical control of dopamine neuron-firing patterns by nicotinic receptors. Neuron 50 , 911–921 (2006).

Picciotto, M. R., Higley, M. J. & Mineur, Y. S. Acetylcholine as a neuromodulator: cholinergic signaling shapes nervous system function and behavior. Neuron 76 , 116–129 (2012).

Le Foll, B. et al. Elevation of dopamine induced by cigarette smoking: novel insights from a [11C]-+-PHNO PET study in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 39 , 415–424 (2014). This brain imaging study identified the brain areas in which smoking elevates dopamine levels .

Maskos, U. et al. Nicotine reinforcement and cognition restored by targeted expression of nicotinic receptors. Nature 436 , 103–107 (2005). This article discusses the implication of the β 2 - containing nAChRs in the VTA in mammalian cognitive function .

Picciotto, M. R. et al. Acetylcholine receptors containing the beta2 subunit are involved in the reinforcing properties of nicotine. Nature 391 , 173–177 (1998). This article discusses the implication of the β 2 - containing nAChRs in addictive effects of nicotine .

Fowler, C. D., Lu, Q., Johnson, P. M., Marks, M. J. & Kenny, P. J. Habenular alpha5 nicotinic receptor subunit signalling controls nicotine intake. Nature 471 , 597–601 (2011). This article discusses the implication of the α5 nicotinic receptor located in the MHb in a mechanism mediating the aversive effects of nicotine .

Elayouby, K. S. et al. α3* Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the habenula-interpeduncular nucleus circuit regulate nicotine intake. J. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0127-19.2020 (2020).

Ables, J. L. et al. Retrograde inhibition by a specific subset of interpeduncular α5 nicotinic neurons regulates nicotine preference. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114 , 13012–13017 (2017).

Frahm, S. et al. Aversion to nicotine is regulated by the balanced activity of β4 and α5 nicotinic receptor subunits in the medial habenula. Neuron 70 , 522–535 (2011).

Jackson, K. J. et al. Role of α5 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in pharmacological and behavioral effects of nicotine in mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 334 , 137–146 (2010).

Tuesta, L. M. et al. GLP-1 acts on habenular avoidance circuits to control nicotine intake. Nat. Neurosci. 20 , 708–716 (2017).

Salas, R., Pieri, F. & De Biasi, M. Decreased signs of nicotine withdrawal in mice null for the β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit. J. Neurosci. 24 , 10035–10039 (2004).

Salas, R., Sturm, R., Boulter, J. & De Biasi, M. Nicotinic receptors in the habenulo-interpeduncular system are necessary for nicotine withdrawal in mice. J. Neurosci. 29 , 3014–3018 (2009).

Jackson, K. J., Martin, B. R., Changeux, J. P. & Damaj, M. I. Differential role of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits in physical and affective nicotine withdrawal signs. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 325 , 302–312 (2008).

Le Foll, B. et al. Translational strategies for therapeutic development in nicotine addiction: rethinking the conventional bench to bedside approach. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 52 , 86–93 (2014).

Naqvi, N. H., Rudrauf, D., Damasio, H. & Bechara, A. Damage to the insula disrupts addiction to cigarette smoking. Science 315 , 531–534 (2007). This article discusses the implication of the insular cortex in tobacco addiction .

Ibrahim, C. et al. The insula: a brain stimulation target for the treatment of addiction. Front. Pharmacol. 10 , 720 (2019).

Zangen, A. et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for smoking cessation: a pivotal multicenter double-blind randomized controlled trial. World Psychiatry 20 , 397–404 (2021). This study validated the utility of deep insula/prefrontal cortex rTMS for smoking cessation .

Le Foll, B., Forget, B., Aubin, H. J. & Goldberg, S. R. Blocking cannabinoid CB1 receptors for the treatment of nicotine dependence: insights from pre-clinical and clinical studies. Addict. Biol. 13 , 239–252 (2008).

Kodas, E., Cohen, C., Louis, C. & Griebel, G. Cortico-limbic circuitry for conditioned nicotine-seeking behavior in rats involves endocannabinoid signaling. Psychopharmacology 194 , 161–171 (2007).

Forget, B. et al. Noradrenergic α1 receptors as a novel target for the treatment of nicotine addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 35 , 1751–1760 (2010).

Garrett, B. E., Dube, S. R., Babb, S. & McAfee, T. Addressing the social determinants of health to reduce tobacco-related disparities. Nicotine Tob. Res. 17 , 892–897 (2015).

Polanska, K., Znyk, M. & Kaleta, D. Susceptibility to tobacco use and associated factors among youth in five central and eastern European countries. BMC Public Health 22 , 72 (2022).

Volkow, N. D. Personalizing the treatment of substance use disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 177 , 113–116 (2020).

Li, M. D., Cheng, R., Ma, J. Z. & Swan, G. E. A meta-analysis of estimated genetic and environmental effects on smoking behavior in male and female adult twins. Addiction 98 , 23–31 (2003).

Carmelli, D., Swan, G. E., Robinette, D. & Fabsitz, R. Genetic influence on smoking–a study of male twins. N. Engl. J. Med. 327 , 829–833 (1992).

Broms, U., Silventoinen, K., Madden, P. A. F., Heath, A. C. & Kaprio, J. Genetic architecture of smoking behavior: a study of Finnish adult twins. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 9 , 64–72 (2006).

Kendler, K. S., Thornton, L. M. & Pedersen, N. L. Tobacco consumption in Swedish twins reared apart and reared together. Arch. Gen. Psychiat 57 , 886–892 (2000).

Saccone, N. L. et al. The CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4 nicotinic receptor subunit gene cluster affects risk for nicotine dependence in African-Americans and in European-Americans. Cancer Res. 69 , 6848–6856 (2009).

Bierut, L. J. et al. Variants in nicotinic receptors and risk for nicotine dependence. Am. J. Psychiatry 165 , 1163–1171 (2008). This study demonstrates that nAChR gene variants are important in nicotine addiction .

Bierut, L. J. et al. Novel genes identified in a high-density genome wide association study for nicotine dependence. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16 , 24–35 (2007).

Berrettini, W. et al. α-5/α-3 nicotinic receptor subunit alleles increase risk for heavy smoking. Mol. Psychiatry 13 , 368–373 (2008).

Sherva, R. et al. Association of a single nucleotide polymorphism in neuronal acetylcholine receptor subunit alpha 5 (CHRNA5) with smoking status and with ‘pleasurable buzz’ during early experimentation with smoking. Addiction 103 , 1544–1552 (2008).

Thorgeirsson, T. E. et al. Sequence variants at CHRNB3-CHRNA6 and CYP2A6 affect smoking behavior. Nat. Genet. 42 , 448–453 (2010).

Ray, R., Tyndale, R. F. & Lerman, C. Nicotine dependence pharmacogenetics: role of genetic variation in nicotine-metabolizing enzymes. J. Neurogenet. 23 , 252–261 (2009).

Bergen, A. W. et al. Drug metabolizing enzyme and transporter gene variation, nicotine metabolism, prospective abstinence, and cigarette consumption. PLoS ONE 10 , e0126113 (2015).

Mwenifumbo, J. C. et al. Identification of novel CYP2A6*1B variants: the CYP2A6*1B allele is associated with faster in vivo nicotine metabolism. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 83 , 115–121 (2008).

Raunio, H. & Rahnasto-Rilla, M. CYP2A6: genetics, structure, regulation, and function. Drug Metab. Drug Interact. 27 , 73–88 (2012).

CAS Google Scholar

Patterson, F. et al. Toward personalized therapy for smoking cessation: a randomized placebo-controlled trial of bupropion. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 84 , 320–325 (2008).

Rodriguez, S. et al. Combined analysis of CHRNA5, CHRNA3 and CYP2A6 in relation to adolescent smoking behaviour. J. Psychopharmacol. 25 , 915–923 (2011).

Strasser, A. A., Malaiyandi, V., Hoffmann, E., Tyndale, R. F. & Lerman, C. An association of CYP2A6 genotype and smoking topography. Nicotine Tob. Res. 9 , 511–518 (2007).

Liakoni, E. et al. Effects of nicotine metabolic rate on withdrawal symptoms and response to cigarette smoking after abstinence. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 105 , 641–651 (2019).

Di Ciano, P. et al. Influence of nicotine metabolism ratio on [11C]-(+)-PHNO PET binding in tobacco smokers. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 21 , 503–512 (2018).

Butler, K. et al. Impact of Cyp2a6 activity on nicotine reinforcement and cue-reactivity in daily smokers. Nicotine Tob. Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntab064 (2021).

Benowitz, N. L., Swan, G. E., Jacob, P. 3rd, Lessov-Schlaggar, C. N. & Tyndale, R. F. CYP2A6 genotype and the metabolism and disposition kinetics of nicotine. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 80 , 457–467 (2006).

Liu, M. et al. Association studies of up to 1.2 million individuals yield new insights into the genetic etiology of tobacco and alcohol use. Nat. Genet. 51 , 237–244 (2019).

McKay, J. D. et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies new lung cancer susceptibility loci and heterogeneity in genetic susceptibility across histological subtypes. Nat. Genet. 49 , 1126–1132 (2017).

Chukwueke, C. C. et al. The CB1R rs2023239 receptor gene variant significantly affects the reinforcing effects of nicotine, but not cue reactivity, in human smokers. Brain Behav. 11 , e01982 (2021).

Ahrens, S. et al. Modulation of nicotine effects on selective attention by DRD2 and CHRNA4 gene polymorphisms. Psychopharmacology 232 , 2323–2331 (2015).

Harrell, P. T. et al. Dopaminergic genetic variation moderates the effect of nicotine on cigarette reward. Psychopharmacology 233 , 351–360 (2016).

Lerman, C. et al. Role of functional genetic variation in the dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) in response to bupropion and nicotine replacement therapy for tobacco dependence: results of two randomized clinical trials. Neuropsychopharmacology 31 , 231–242 (2006).

Le Foll, B., Gallo, A., Le Strat, Y., Lu, L. & Gorwood, P. Genetics of dopamine receptors and drug addiction: a comprehensive review. Behav. Pharmacol. 20 , 1–17 (2009).

Chukwueke, C. C. et al. Exploring the role of the Ser9Gly (rs6280) dopamine D3 receptor polymorphism in nicotine reinforcement and cue-elicited craving. Sci. Rep. 10 , 4085 (2020).

The Clinical Practice Guideline Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence 2008 Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update: a U.S. Public Health Service report. Am. J. Prev. Med. 35 , 158–176 (2008).

Hackshaw, A., Morris, J. K., Boniface, S., Tang, J. L. & Milenković, D. Low cigarette consumption and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: meta-analysis of 141 cohort studies in 55 study reports. BMJ 360 , j5855 (2018).

Qin, W. et al. Light cigarette smoking increases risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality: findings from the NHIS cohort study. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145122 (2020).

Rodu, B. & Plurphanswat, N. Mortality among male smokers and smokeless tobacco users in the USA. Harm Reduct. J. 16 , 50 (2019).

Kasza, K. A. et al. Tobacco-product use by adults and youths in the United States in 2013 and 2014. N. Engl. J. Med. 376 , 342–353 (2017).

Richardson, A., Xiao, H. & Vallone, D. M. Primary and dual users of cigars and cigarettes: profiles, tobacco use patterns and relevance to policy. Nicotine Tob. Res. 14 , 927–932 (2012).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders 5th edn (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

World Health Organization. Tobacco fact sheet. WHO https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco (2021).

Heatherton, T. F., Kozlowski, L. T., Frecker, R. C. & Fagerström, K. O. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström tolerance questionnaire. Br. J. Addict. 86 , 1119–1127 (1991).

Heatherton, T. F., Kozlowski, L. T., Frecker, R. C., Rickert, W. & Robinson, J. Measuring the heaviness of smoking: using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. Br. J. Addict. 84 , 791–799 (1989).

Etter, J. F., Le Houezec, J. & Perneger, T. V. A self-administered questionnaire to measure dependence on cigarettes: the cigarette dependence scale. Neuropsychopharmacology 28 , 359–370 (2003).

DiFranza, J. R. et al. Measuring the loss of autonomy over nicotine use in adolescents: the DANDY (Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youths) study. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 156 , 397–403 (2002).

Shiffman, S., Waters, A. & Hickcox, M. The Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale: a multidimensional measure of nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob. Res. 6 , 327–348 (2004).

Smith, S. S. et al. Development of the Brief Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives. Nicotine Tob. Res. 12 , 489–499 (2010).

Foulds, J. et al. Development of a questionnaire for assessing dependence on electronic cigarettes among a large sample of ex-smoking E-cigarette users. Nicotine Tob. Res. 17 , 186–192 (2015).

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: a report of the Surgeon General (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012).

World Health Organization. Tobacco control to improve child health and development. Thematic brief (WHO, 2021).

Lantz, P. M. et al. Investing in youth tobacco control: a review of smoking prevention and control strategies. Tob. Control. 9 , 47–63 (2000).

Leão, T., Kunst, A. E. & Perelman, J. Cost-effectiveness of tobacco control policies and programmes targeting adolescents: a systematic review. Eur. J. Public Health 28 , 39–43 (2018).

Royal College of Physicians. Smoking and health 2021: a coming of age for tobacco control? (RCP, 2021).

Higashi, H. et al. Cost effectiveness of tobacco control policies in Vietnam: the case of population-level interventions. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 9 , 183–196 (2011).

Ranson, M. K., Jha, P., Chaloupka, F. J. & Nguyen, S. N. Global and regional estimates of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of price increases and other tobacco control policies. Nicotine Tob. Res. 4 , 311–319 (2002).

International Agency for Research on Cancer. I ARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention: Tobacco control Vol. 14 (IARC, 2011).

Frazer, K. et al. Legislative smoking bans for reducing harms from secondhand smoke exposure, smoking prevalence and tobacco consumption. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2 , CD005992 (2016).

Hoffman, S. J. & Tan, C. Overview of systematic reviews on the health-related effects of government tobacco control policies. BMC Public Health 15 , 744 (2015).

McNeill, A. et al. Tobacco packaging design for reducing tobacco use. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 4 , CD011244 (2017).

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. Smoking cessation: a report of the Surgeon General (Department of Health and Human Services, 2020).

Lindson, N. et al. Different doses, durations and modes of delivery of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 4 , CD013308 (2019).

Krist, A. H. et al. Interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 325 , 265–279 (2021).