My Quarantine Experience Essay & Paragraphs For Students

The COVID-19 pandemic ushered in an era of quarantine and social distancing, profoundly impacting our daily lives. This essay will delve into my personal experience during quarantine, highlighting the challenges, adaptations, and insights gleaned from this unique period.

Table of Contents

Essay On My Quarantine Experience

To comprehend my quarantine experience fully, it is important to understand what quarantine entails. It is a preventive measure aimed at curbing the spread of infectious diseases by isolating individuals who have been exposed to the infection. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, quarantine involved staying at home, minimizing physical contact with others and practicing strict hygiene protocols.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); Initial Reactions: The Onset of Quarantine

The initial days of quarantine were marked by a mix of anxiety, uncertainty, and confusion as familiar routines were disrupted. This section will explore my initial reactions to the sudden shift in lifestyle, the challenges faced, and the coping mechanisms adopted.

Adapting to a New Normal: Life During Quarantine

Quarantine necessitated a significant adaptation to a “new normal”. From working from home to virtual social interactions, life underwent a dramatic transformation. This part will discuss the various adjustments made during quarantine, focusing on work, education, social interactions, and daily routines.

Discovering New Interests: The Silver Lining

Despite the challenges, quarantine also offered an opportunity to explore new interests and hobbies. With additional free time, I found myself engaging in activities like reading, cooking, online courses, and fitness routines at home. This section will delve into these newfound interests and their impact on my overall well-being.

Emotional Impact: Navigating Mental Health During Quarantine

Quarantine also had a significant impact on mental health. The isolation, coupled with the constant influx of pandemic-related news, led to feelings of stress and anxiety. This part will discuss the emotional impact of quarantine, the strategies employed to maintain mental health, and the significance of seeking help when required.

Lessons Learned: Insights from the Quarantine Experience

Quarantine, while challenging, also offered valuable insights into resilience, adaptability, and the importance of community. It highlighted the need for empathy, understanding, and collective responsibility during times of crisis. This section will reflect on these lessons and their implications for the future.

Conclusion: Reflecting on My Quarantine Experience

My quarantine experience was a journey of adaptation, self-discovery, and resilience. While it posed numerous challenges, it also offered an opportunity to slow down, introspect, and focus on personal growth. As I reflect on this period, I realize that despite the hardships, the experience has equipped me with a better understanding of myself, a greater appreciation for connection, and a renewed sense of resilience to navigate future challenges.

Hello! Welcome to my Blog StudyParagraphs.co. My name is Angelina. I am a college professor. I love reading writing for kids students. This blog is full with valuable knowledge for all class students. Thank you for reading my articles.

Related Posts:

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

COVID-19 Lockdown: My Experience

When the lockdown started, I was ecstatic. My final year of school had finished early, exams were cancelled, the sun was shining. I was happy, and confident I would be OK. After all, how hard could staying at home possibly be? After a while, the reality of the situation started to sink in.

The novelty of being at home wore off and I started to struggle. I suffered from regular panic attacks, frozen on the floor in my room, unable to move or speak. I had nightmares most nights, and struggled to sleep. It was as if I was stuck, trapped in my house and in my own head. I didn't know how to cope.

However, over time, I found ways to deal with the pressure. I realised that lockdown gave me more time to the things I loved, hobbies that had been previously swamped by schoolwork. I started baking, drawing and writing again, and felt free for the first time in months. I had forgotten how good it felt to be creative. I started spending more time with my family. I hadn't realised how much I had missed them.

Almost a month later, I feel so much better. I understand how difficult this must be, but it's important to remember that none of us is alone. No matter how scared, or trapped, or alone you feel, things can only get better. Take time to revisit the things you love, and remember that all of this will eventually pass. All we can do right now is stay at home, look after ourselves and our loved ones, and look forward to a better future.

View the discussion thread.

Related Stories

Looking back on lockdown days

Art class and self care during the pandemic

We'll Walk Together

A Race to What Finish Line

C 2019 Voices of Youth. All Rights Reserved.

The Benefits of Being Inside: My Experience of Quarantine

Therapist josh hogan shares his experience of quarantine after developing coronavirus symptoms, his period of self-isolation had ups and downs as he was both forced to, and made the effort to, look inwards, if you would like to talk to a therapist, start your search here.

I have seen a quote doing the rounds on social media that seems apposite during present events: “If you can’t go outside, go inside.” I cannot find the original author of the quote - perhaps it belongs to an ancient sage, or perhaps it was a random tweet that went viral in the last few weeks. Either way, for me it sums up a helpful way through the health crisis that we are facing.

Coping during lockdown

As I write, a third of the world’s population is on ‘lockdown’, meaning severely restricted movement outside of the home. In the UK, if you display any of the known symptoms of Covid-19 you are required to stay indoors for seven days, while members of your household are to stay in for fourteen. Everyone should be limiting their trips outside to the bare essentials. Workers not considered ‘essential’ to the national effort are asked not to go to work; social gatherings of more than two people are subject to a blanket ban. Everyone is affected by this, everyone’s way of life has changed dramatically in the last two weeks. Most of us will need to get used to spending a lot of time indoors, which is where that quote becomes relevant, as we close our doors and get better acquainted with our own interior lives.

For me, ‘going inside’ means sitting with myself and focusing on what is going on internally. Of course it might mean completely different things to different people. Having been forced to spend a significant amount of time indoors, I find myself increasingly drawn to the idea of exploring my internal reactions to what’s going on.

The coronavirus crisis is being called a once-in-a-century event, and it’s easy to concur with that description. The only similar event in living memory for us Brits will be the blackouts of the Second World War. Perhaps the most alarming thing about this experience is how out of the blue it was, as well as how quickly it escalated.

In January when I first heard about this mysterious virus that was claiming hundreds of lives in China, like most of us I couldn’t imagine the same thing ever happening here. Yet as I write today I sit at home in quarantine, having developed the symptoms of that very virus last week. It’s just been announced that the Prime Minister and the heir to the throne have the virus too. It seems no one will escape the fallout.

I wasn’t expecting self-isolation to be fun, and it hasn’t been. For a few days last week I was very unwell, suffering from the worst case of flu I’d ever had. This week I’ve experienced a slow but steady recovery. I gather from official government advice that I should have stopped being contagious a few days ago, and so I am once more able to venture to the shops to meet my basic needs. But I wouldn’t say I am 100% back to normal health. I am lucky to be relatively young and fit, so I’ve had nothing more than a bad case of the flu, where many others will endure far worse. My thoughts during this time have frequently turned to the countless people who won’t survive this awful illness, and to the brave healthcare workers who will look after them.

It has been a shock to the system, on both a personal and a national level. I rarely ever get ill, and I don’t like it when I do. Remaining indoors for seven days gets exhausting – having infinite choice when it comes to streamable films and TV shows is more of a curse than a blessing.

Finding some peace

Quite apart from the ongoing economic fallout, I’ve been stunned to observe the impact on the once busy streets of my home city, which for the first time in my life could be described as ‘quiet’. The significant fall in traffic is already being said to correlate with much cleaner air in our skies. Luckily my infrequent trips to the shop this week have been peaceful, my fellow shoppers always standing a polite two metres apart, smiling and nodding as I get in line behind them. The good will that we’re expressing towards our healthcare workers and towards each other is one of the heartening aspects of all of this.

Having to spend so much time inside has taught me that I need to find better solutions to boredom. Online TV bingeing has been my go to antidote to lethargy, and after a solid week of it I can confirm that it makes the problem worse.

At the start of all this, naturally I pledged to be good and accomplish all the things I wouldn’t normally have time to do, such as daily meditating. As the lockdown continues I find these tasks to be more and more vital to my wellbeing. While I can’t go outside I really have no option other than to ‘go inside’, where I stand a chance of assuaging my innate anxiety. At first, having all this time to meditate makes me oddly resistant to it, which tells me that I must persevere. When I focus on my breathing and on what’s going on in my body at the present moment, I can’t get caught up in worrying about the future and what’s going to happen with this virus. Unlike Netflix and the 24 hour news channels, practising mindfulness doesn’t leave me feeling frustrated or triggered or fatigued. It is a source of replenishment that sees me through to the next day.

Josh Hogan is a verified welldoing.org therapist who works in London and online

Further reading

Welldoing.org's 8 coronavirus mental health tips, unexpected endings: support for young people after school closures, using exercise and cbt techniques to combat lockdown anxiety, 6 youtube videos for mindfulness meditation, self-care tips from an introvert: how to make the most of isolation, find welldoing therapists near you, related articles, recent posts.

Stigma and Synaesthesia: My Experience of Bipolar Disorder

The Burnout Danger Zone and How to Prevent It Happening

Meet the Therapist: Jenny Hunter-Phillips

Johann Hari Explores the Benefits and Risks of New Weight Loss Drugs

Dream Circle for Welldoing Therapist Members

Dear Therapist..."Social Situations Are Draining"

ABMT Event To Support People With Medically Unexplained Symptoms

Can Wild Swimming Ease Anxiety, Depression and Stress?

Meet the Therapist: Bettina Falkenberg

Psychotherapist Louis Weinstock: "The Children's Mental Health Crisis Should Be a Wake Up Call"

Find counsellors and therapists in London

Find counsellors and therapists in your region, join over 23,000 others on our newsletter.

- Current Issue

- Journal Archive

- Current Call

Search form

Coronavirus: My Experience During the Pandemic

Anastasiya Kandratsenka George Washington High School, Class of 2021

At this point in time there shouldn't be a single person who doesn't know about the coronavirus, or as they call it, COVID-19. The coronavirus is a virus that originated in China, reached the U.S. and eventually spread all over the world by January of 2020. The common symptoms of the virus include shortness of breath, chills, sore throat, headache, loss of taste and smell, runny nose, vomiting and nausea. As it has been established, it might take up to 14 days for the symptoms to show. On top of that, the virus is also highly contagious putting all age groups at risk. The elderly and individuals with chronic diseases such as pneumonia or heart disease are in the top risk as the virus attacks the immune system.

The virus first appeared on the news and media platforms in the month of January of this year. The United States and many other countries all over the globe saw no reason to panic as it seemed that the virus presented no possible threat. Throughout the next upcoming months, the virus began to spread very quickly, alerting health officials not only in the U.S., but all over the world. As people started digging into the origin of the virus, it became clear that it originated in China. Based on everything scientists have looked at, the virus came from a bat that later infected other animals, making it way to humans. As it goes for the United States, the numbers started rising quickly, resulting in the cancellation of sports events, concerts, large gatherings and then later on schools.

As it goes personally for me, my school was shut down on March 13th. The original plan was to put us on a two weeks leave, returning on March 30th but, as the virus spread rapidly and things began escalating out of control very quickly, President Trump announced a state of emergency and the whole country was put on quarantine until April 30th. At that point, schools were officially shut down for the rest of the school year. Distanced learning was introduced, online classes were established, a new norm was put in place. As for the School District of Philadelphia distanced learning and online classes began on May 4th. From that point on I would have classes four times a week, from 8AM till 3PM. Virtual learning was something that I never had to experience and encounter before. It was all new and different for me, just as it was for millions of students all over the United States. We were forced to transfer from physically attending school, interacting with our peers and teachers, participating in fun school events and just being in a classroom setting, to just looking at each other through a computer screen in a number of days. That is something that we all could have never seen coming, it was all so sudden and new.

My experience with distanced learning was not very great. I get distracted very easily and find it hard to concentrate, especially when it comes to school. In a classroom I was able to give my full attention to what was being taught, I was all there. However, when we had the online classes, I could not focus and listen to what my teachers were trying to get across. I got distracted very easily, missing out on important information that was being presented. My entire family which consists of five members, were all home during the quarantine. I have two little siblings who are very loud and demanding, so I’m sure it can be imagined how hard it was for me to concentrate on school and do what was asked of me when I had these two running around the house. On top of school, I also had to find a job and work 35 hours a week to support my family during the pandemic. My mother lost her job for the time being and my father was only able to work from home. As we have a big family, the income of my father was not enough. I made it my duty to help out and support our family as much as I could: I got a job at a local supermarket and worked there as a cashier for over two months.

While I worked at the supermarket, I was exposed to dozens of people every day and with all the protection that was implemented to protect the customers and the workers, I was lucky enough to not get the virus. As I say that, my grandparents who do not even live in the U.S. were not so lucky. They got the virus and spent over a month isolated, in a hospital bed, with no one by their side. Our only way of communicating was through the phone and if lucky, we got to talk once a week. Speaking for my family, that was the worst and scariest part of the whole situation. Luckily for us, they were both able to recover completely.

As the pandemic is somewhat under control, the spread of the virus has slowed down. We’re now living in the new norm. We no longer view things the same, the way we did before. Large gatherings and activities that require large groups to come together are now unimaginable! Distanced learning is what we know, not to mention the importance of social distancing and having to wear masks anywhere and everywhere we go. This is the new norm now and who knows when and if ever we’ll be able go back to what we knew before. This whole experience has made me realize that we, as humans, tend to take things for granted and don’t value what we have until it is taken away from us.

Articles in this Volume

[tid]: dedication, [tid]: new tools for a new house: transformations for justice and peace in and beyond covid-19, [tid]: black lives matter, intersectionality, and lgbtq rights now, [tid]: the voice of asian american youth: what goes untold, [tid]: beyond words: reimagining education through art and activism, [tid]: voice(s) of a black man, [tid]: embodied learning and community resilience, [tid]: re-imagining professional learning in a time of social isolation: storytelling as a tool for healing and professional growth, [tid]: reckoning: what does it mean to look forward and back together as critical educators, [tid]: leader to leaders: an indigenous school leader’s advice through storytelling about grief and covid-19, [tid]: finding hope, healing and liberation beyond covid-19 within a context of captivity and carcerality, [tid]: flux leadership: leading for justice and peace in & beyond covid-19, [tid]: flux leadership: insights from the (virtual) field, [tid]: hard pivot: compulsory crisis leadership emerges from a space of doubt, [tid]: and how are the children, [tid]: real talk: teaching and leading while bipoc, [tid]: systems of emotional support for educators in crisis, [tid]: listening leadership: the student voices project, [tid]: global engagement, perspective-sharing, & future-seeing in & beyond a global crisis, [tid]: teaching and leadership during covid-19: lessons from lived experiences, [tid]: crisis leadership in independent schools - styles & literacies, [tid]: rituals, routines and relationships: high school athletes and coaches in flux, [tid]: superintendent back-to-school welcome 2020, [tid]: mitigating summer learning loss in philadelphia during covid-19: humble attempts from the field, [tid]: untitled, [tid]: the revolution will not be on linkedin: student activism and neoliberalism, [tid]: why radical self-care cannot wait: strategies for black women leaders now, [tid]: from emergency response to critical transformation: online learning in a time of flux, [tid]: illness methodology for and beyond the covid era, [tid]: surviving black girl magic, the work, and the dissertation, [tid]: cancelled: the old student experience, [tid]: lessons from liberia: integrating theatre for development and youth development in uncertain times, [tid]: designing a more accessible future: learning from covid-19, [tid]: the construct of standards-based education, [tid]: teachers leading teachers to prepare for back to school during covid, [tid]: using empathy to cross the sea of humanity, [tid]: (un)doing college, community, and relationships in the time of coronavirus, [tid]: have we learned nothing, [tid]: choosing growth amidst chaos, [tid]: living freire in pandemic….participatory action research and democratizing knowledge at knowledgedemocracy.org, [tid]: philly students speak: voices of learning in pandemics, [tid]: the power of will: a letter to my descendant, [tid]: photo essays with students, [tid]: unity during a global pandemic: how the fight for racial justice made us unite against two diseases, [tid]: educational changes caused by the pandemic and other related social issues, [tid]: online learning during difficult times, [tid]: fighting crisis: a student perspective, [tid]: the destruction of soil rooted with culture, [tid]: a demand for change, [tid]: education through experience in and beyond the pandemics, [tid]: the pandemic diaries, [tid]: all for one and 4 for $4, [tid]: tiktok activism, [tid]: why digital learning may be the best option for next year, [tid]: my 2020 teen experience, [tid]: living between two pandemics, [tid]: journaling during isolation: the gold standard of coronavirus, [tid]: sailing through uncertainty, [tid]: what i wish my teachers knew, [tid]: youthing in pandemic while black, [tid]: the pain inflicted by indifference, [tid]: education during the pandemic, [tid]: the good, the bad, and the year 2020, [tid]: racism fueled pandemic, [tid]: coronavirus: my experience during the pandemic, [tid]: the desensitization of a doomed generation, [tid]: a philadelphia war-zone, [tid]: the attack of the covid monster, [tid]: back-to-school: covid-19 edition, [tid]: the unexpected war, [tid]: learning outside of the classroom, [tid]: why we should learn about college financial aid in school: a student perspective, [tid]: flying the plane as we go: building the future through a haze, [tid]: my covid experience in the age of technology, [tid]: we, i, and they, [tid]: learning your a, b, cs during a pandemic, [tid]: quarantine: a musical, [tid]: what it’s like being a high school student in 2020, [tid]: everything happens for a reason, [tid]: blacks live matter – a sobering and empowering reality among my peers, [tid]: the mental health of a junior during covid-19 outbreaks, [tid]: a year of change, [tid]: covid-19 and school, [tid]: the virtues and vices of virtual learning, [tid]: college decisions and the year 2020: a virtual rollercoaster, [tid]: quarantine thoughts, [tid]: quarantine through generation z, [tid]: attending online school during a pandemic.

Report accessibility issues and request help

Copyright 2024 The University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education's Online Urban Education Journal

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- Home Planet

- 2024 election

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

Artists, novelists, critics, and essayists are writing the first draft of history.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66606035/1207638131.jpg.0.jpg)

The world is grappling with an invisible, deadly enemy, trying to understand how to live with the threat posed by a virus . For some writers, the only way forward is to put pen to paper, trying to conceptualize and document what it feels like to continue living as countries are under lockdown and regular life seems to have ground to a halt.

So as the coronavirus pandemic has stretched around the world, it’s sparked a crop of diary entries and essays that describe how life has changed. Novelists, critics, artists, and journalists have put words to the feelings many are experiencing. The result is a first draft of how we’ll someday remember this time, filled with uncertainty and pain and fear as well as small moments of hope and humanity.

At the New York Review of Books, Ali Bhutto writes that in Karachi, Pakistan, the government-imposed curfew due to the virus is “eerily reminiscent of past military clampdowns”:

Beneath the quiet calm lies a sense that society has been unhinged and that the usual rules no longer apply. Small groups of pedestrians look on from the shadows, like an audience watching a spectacle slowly unfolding. People pause on street corners and in the shade of trees, under the watchful gaze of the paramilitary forces and the police.

His essay concludes with the sobering note that “in the minds of many, Covid-19 is just another life-threatening hazard in a city that stumbles from one crisis to another.”

Writing from Chattanooga, novelist Jamie Quatro documents the mixed ways her neighbors have been responding to the threat, and the frustration of conflicting direction, or no direction at all, from local, state, and federal leaders:

Whiplash, trying to keep up with who’s ordering what. We’re already experiencing enough chaos without this back-and-forth. Why didn’t the federal government issue a nationwide shelter-in-place at the get-go, the way other countries did? What happens when one state’s shelter-in-place ends, while others continue? Do states still under quarantine close their borders? We are still one nation, not fifty individual countries. Right?

Award-winning photojournalist Alessio Mamo, quarantined with his partner Marta in Sicily after she tested positive for the virus, accompanies his photographs in the Guardian of their confinement with a reflection on being confined :

The doctors asked me to take a second test, but again I tested negative. Perhaps I’m immune? The days dragged on in my apartment, in black and white, like my photos. Sometimes we tried to smile, imagining that I was asymptomatic, because I was the virus. Our smiles seemed to bring good news. My mother left hospital, but I won’t be able to see her for weeks. Marta started breathing well again, and so did I. I would have liked to photograph my country in the midst of this emergency, the battles that the doctors wage on the frontline, the hospitals pushed to their limits, Italy on its knees fighting an invisible enemy. That enemy, a day in March, knocked on my door instead.

In the New York Times Magazine, deputy editor Jessica Lustig writes with devastating clarity about her family’s life in Brooklyn while her husband battled the virus, weeks before most people began taking the threat seriously:

At the door of the clinic, we stand looking out at two older women chatting outside the doorway, oblivious. Do I wave them away? Call out that they should get far away, go home, wash their hands, stay inside? Instead we just stand there, awkwardly, until they move on. Only then do we step outside to begin the long three-block walk home. I point out the early magnolia, the forsythia. T says he is cold. The untrimmed hairs on his neck, under his beard, are white. The few people walking past us on the sidewalk don’t know that we are visitors from the future. A vision, a premonition, a walking visitation. This will be them: Either T, in the mask, or — if they’re lucky — me, tending to him.

Essayist Leslie Jamison writes in the New York Review of Books about being shut away alone in her New York City apartment with her 2-year-old daughter since she became sick:

The virus. Its sinewy, intimate name. What does it feel like in my body today? Shivering under blankets. A hot itch behind the eyes. Three sweatshirts in the middle of the day. My daughter trying to pull another blanket over my body with her tiny arms. An ache in the muscles that somehow makes it hard to lie still. This loss of taste has become a kind of sensory quarantine. It’s as if the quarantine keeps inching closer and closer to my insides. First I lost the touch of other bodies; then I lost the air; now I’ve lost the taste of bananas. Nothing about any of these losses is particularly unique. I’ve made a schedule so I won’t go insane with the toddler. Five days ago, I wrote Walk/Adventure! on it, next to a cut-out illustration of a tiger—as if we’d see tigers on our walks. It was good to keep possibility alive.

At Literary Hub, novelist Heidi Pitlor writes about the elastic nature of time during her family’s quarantine in Massachusetts:

During a shutdown, the things that mark our days—commuting to work, sending our kids to school, having a drink with friends—vanish and time takes on a flat, seamless quality. Without some self-imposed structure, it’s easy to feel a little untethered. A friend recently posted on Facebook: “For those who have lost track, today is Blursday the fortyteenth of Maprilay.” ... Giving shape to time is especially important now, when the future is so shapeless. We do not know whether the virus will continue to rage for weeks or months or, lord help us, on and off for years. We do not know when we will feel safe again. And so many of us, minus those who are gifted at compartmentalization or denial, remain largely captive to fear. We may stay this way if we do not create at least the illusion of movement in our lives, our long days spent with ourselves or partners or families.

Novelist Lauren Groff writes at the New York Review of Books about trying to escape the prison of her fears while sequestered at home in Gainesville, Florida:

Some people have imaginations sparked only by what they can see; I blame this blinkered empiricism for the parks overwhelmed with people, the bars, until a few nights ago, thickly thronged. My imagination is the opposite. I fear everything invisible to me. From the enclosure of my house, I am afraid of the suffering that isn’t present before me, the people running out of money and food or drowning in the fluid in their lungs, the deaths of health-care workers now growing ill while performing their duties. I fear the federal government, which the right wing has so—intentionally—weakened that not only is it insufficient to help its people, it is actively standing in help’s way. I fear we won’t sufficiently punish the right. I fear leaving the house and spreading the disease. I fear what this time of fear is doing to my children, their imaginations, and their souls.

At ArtForum , Berlin-based critic and writer Kristian Vistrup Madsen reflects on martinis, melancholia, and Finnish artist Jaakko Pallasvuo’s 2018 graphic novel Retreat , in which three young people exile themselves in the woods:

In melancholia, the shape of what is ending, and its temporality, is sprawling and incomprehensible. The ambivalence makes it hard to bear. The world of Retreat is rendered in lush pink and purple watercolors, which dissolve into wild and messy abstractions. In apocalypse, the divisions established in genesis bleed back out. My own Corona-retreat is similarly soft, color-field like, each day a blurred succession of quarantinis, YouTube–yoga, and televized press conferences. As restrictions mount, so does abstraction. For now, I’m still rooting for love to save the world.

At the Paris Review , Matt Levin writes about reading Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves during quarantine:

A retreat, a quarantine, a sickness—they simultaneously distort and clarify, curtail and expand. It is an ideal state in which to read literature with a reputation for difficulty and inaccessibility, those hermetic books shorn of the handholds of conventional plot or characterization or description. A novel like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is perfect for the state of interiority induced by quarantine—a story of three men and three women, meeting after the death of a mutual friend, told entirely in the overlapping internal monologues of the six, interspersed only with sections of pure, achingly beautiful descriptions of the natural world, a day’s procession and recession of light and waves. The novel is, in my mind’s eye, a perfectly spherical object. It is translucent and shimmering and infinitely fragile, prone to shatter at the slightest disturbance. It is not a book that can be read in snatches on the subway—it demands total absorption. Though it revels in a stark emotional nakedness, the book remains aloof, remote in its own deep self-absorption.

In an essay for the Financial Times, novelist Arundhati Roy writes with anger about Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s anemic response to the threat, but also offers a glimmer of hope for the future:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

From Boston, Nora Caplan-Bricker writes in The Point about the strange contraction of space under quarantine, in which a friend in Beirut is as close as the one around the corner in the same city:

It’s a nice illusion—nice to feel like we’re in it together, even if my real world has shrunk to one person, my husband, who sits with his laptop in the other room. It’s nice in the same way as reading those essays that reframe social distancing as solidarity. “We must begin to see the negative space as clearly as the positive, to know what we don’t do is also brilliant and full of love,” the poet Anne Boyer wrote on March 10th, the day that Massachusetts declared a state of emergency. If you squint, you could almost make sense of this quarantine as an effort to flatten, along with the curve, the distinctions we make between our bonds with others. Right now, I care for my neighbor in the same way I demonstrate love for my mother: in all instances, I stay away. And in moments this month, I have loved strangers with an intensity that is new to me. On March 14th, the Saturday night after the end of life as we knew it, I went out with my dog and found the street silent: no lines for restaurants, no children on bicycles, no couples strolling with little cups of ice cream. It had taken the combined will of thousands of people to deliver such a sudden and complete emptiness. I felt so grateful, and so bereft.

And on his own website, musician and artist David Byrne writes about rediscovering the value of working for collective good , saying that “what is happening now is an opportunity to learn how to change our behavior”:

In emergencies, citizens can suddenly cooperate and collaborate. Change can happen. We’re going to need to work together as the effects of climate change ramp up. In order for capitalism to survive in any form, we will have to be a little more socialist. Here is an opportunity for us to see things differently — to see that we really are all connected — and adjust our behavior accordingly. Are we willing to do this? Is this moment an opportunity to see how truly interdependent we all are? To live in a world that is different and better than the one we live in now? We might be too far down the road to test every asymptomatic person, but a change in our mindsets, in how we view our neighbors, could lay the groundwork for the collective action we’ll need to deal with other global crises. The time to see how connected we all are is now.

The portrait these writers paint of a world under quarantine is multifaceted. Our worlds have contracted to the confines of our homes, and yet in some ways we’re more connected than ever to one another. We feel fear and boredom, anger and gratitude, frustration and strange peace. Uncertainty drives us to find metaphors and images that will let us wrap our minds around what is happening.

Yet there’s no single “what” that is happening. Everyone is contending with the pandemic and its effects from different places and in different ways. Reading others’ experiences — even the most frightening ones — can help alleviate the loneliness and dread, a little, and remind us that what we’re going through is both unique and shared by all.

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In Culture

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Blood, flames, and horror movies: The evocative imagery of King Charles’s portrait

Why the US built a pier to get aid into Gaza

The controversy over Gaza’s death toll, explained

Why a GOP governor’s pardon of a far-right murderer is so chilling

The video where Diddy appears to attack Cassie — and the allegations against him — explained

ChatGPT can talk, but OpenAI employees sure can’t

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

‘I haven’t really had a proper weekend in a long time’

Party like it’s 2020

Study of Psychedelics in Society and Culture announces funding recipients

‘the full covid-19 experience’.

A science and medical reporter offers an intimate look at the pandemic’s personal impact

Alvin Powell and his mother, Alynne Martelle, who passed away from COVID-19 in April 2020.

Photos courtesy of Alvin Powell

Portraits of Loss

Alvin powell.

A collection of stories and essays that illustrate the indelible mark left on our community by a pandemic that touched all our lives.

I remember thinking, “I guess I’m having the full COVID-19 experience,” though I knew immediately it wasn’t true. Having the full experience would mean switching places with the frail woman before me. It would mean my eyes were the ones that were closed, my breath silent and shallow.

But I also knew she wouldn’t want it that way. My mother, Alynne Martelle, was protective like that.

It was April 2020, and I was sitting in a Connecticut nursing home across the bed from my sister Kelly San Martin. I wasn’t thinking about how outlandishly I was dressed, but each glance across the bed provided a reminder. We were both wearing thin, disposable yellow gowns and too-big rubber gloves, with surgical masks covering our noses and mouths. We were each hoping the protection would be enough, but at that point in the pandemic’s first spring surge, nothing seemed certain.

Earlier that day — a Friday — I had been working from home and heard from my sister that my mom, 80 and diagnosed with COVID-19, had taken a turn for the worse. I called the nursing home where she’d lived for nearly five years, and the nurse said to come right away. So I told my editors at the Gazette what was going on, got in the car, and headed down the Pike.

I had a couple of hours to think during the drive. As a science writer for the Gazette, I routinely monitor disease outbreaks around the world — SARS, H1N1, seasonal flu — and discuss them with experts at the University. My hope is to lend perspective for readers on news that can seem too distant to be threatening — yet to which they might want to pay attention— or things that seem threateningly close, but in fact are rare enough that the screaming headlines may not be warranted.

“I suspect that a nursing home isn’t part of anyone’s plan for their final years, and it certainly wasn’t for my mother.“ Alvin Powell

There were two times during my coverage of the pandemic that I felt an almost physical sensation — that pit-of-the-stomach feeling of shock or fear. The first was when Marc Lipsitch, an epidemiologist and head of the Harvard Chan School’s Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics, said early on that, unlike its recent predecessors SARS and MERS, which got people very sick, this virus also caused a lot of mild or asymptomatic cases. As that news sank in, I realized how difficult the future might become: How can you stop something before you know it’s there?

The second time I had that feeling was just a few weeks later. Through February 2020, the number of cases in the U.S. and globally had continued to grow, and it became clear that a major public health emergency was underway. Harvard’s experts, among many others, were offering a way forward, and I was writing regularly about the pandemic, about the new-to-me concept of “social distancing” and the importance of using masks to reduce spread — even as faculty members at our hospitals were also warning of shortages of personal protective equipment, or PPE — another term now embedded in our daily language. That was when President Donald Trump used the word “hoax” in discussing the pandemic. When I read that I thought, “This could get a lot worse.”

More in this series

A table set for two

A teacher for 40 years and a neighborhood ‘den mother’

Pandemic from the rear-view mirror of an ambulance

My grandpa’s 100 hats

By the third week in April, it had. Then, of course, the winter’s much larger surge was still just a vague threat and 100,000 deaths nationally from COVID-19 would soon warrant front-page treatment in The New York Times. Nursing homes — which concentrated society’s frail and elderly — had been hit hard early, as protective measures were being worked out and individual habits — life-saving ones — were still being ingrained.

I suspect that a nursing home isn’t part of anyone’s plan for their final years, and it certainly wasn’t for my mother. She was born in Hartford, poor and proudly Irish. She was artistic, eccentric, and joked later in life that if she hyphenated all her last names, she’d be Alynne Cummings-Powell-Martelle-Martelle-Herzberger-Harripersaud. Though she was tough on her husbands, she was easy on her kids. Despite the roiling of her married life, our home in the Hartford suburbs was mostly stable. That was largely due to the stick-to-it-iveness of my stepfather Sal — the two Martelles in there — and the fact that her four kids never doubted that she loved them.

She traveled even more than she married, preferring out-of-the-way places and bringing home images of the people who lived there. Among her destinations, she spent a summer in Calcutta volunteering at one of Mother Teresa’s orphanages and, on her return, she struck up a correspondence with the future saint.

Alynne Martell (center) surrounded by her children, Laura Lynne Powell (clockwise from left), Kelly San Martin, Alvin Powell, and Joseph Martelle. They are pictured at Hawks Nest Beach in Old Lyme, Conn., where they’ve gone for a week each summer for more than 45 years. Powell and his mother on a family kayak trip on the Black Hall River in Old Lyme.

Mom’s later years were difficult. Her mental decline had her moving from independent to assisted living and then to round-the-clock care. In the last year, her physical health and mobility had declined as well. When my mother spiked a fever in April, my siblings and I assumed it was COVID. It took the doctors some time to work through the possibilities, but they eventually got there, too. They and the nurses reminded us that it was not universally fatal, but nonetheless asked whether she had a living will. She did, and wanted no extraordinary measures taken.

Though many hospitals and nursing homes weren’t allowing visitors, the home where my mother stayed would let us in. Several family members had converged on the parking lot there, and we had a robust discussion of how safe it would be to go inside. My mother’s room was on the first floor, and some family members peered through its sliding glass door. My sister and I decided it was worth the risk to sit with Mom during her final hours, as she would have if indeed our places had been reversed.

On that Friday when Kelly and I entered the lobby, the facility appeared to be taking necessary precautions. In addition to providing PPE, they questioned us about our health and took our temperatures before letting us farther into the building. The main thing I was uneasy about was the use of surgical masks rather than N95 respirators. The N95s, I thought, would provide a level of protection commensurate with sitting in a place where we knew the virus was circulating.

On the second day, two friends teamed up to get us the N95s one had stockpiled during the 2009 H1N1 epidemic. We met in the parking lot for the handover — accomplished with profuse thanks and at a safe distance. The masks eased my mind. The key to weathering the pandemic came not from hiding away, but from a clear-eyed assessment of risks and having a plan to manage them. I had also learned during months of covering the pandemic that even measures inadequate on their own could be powerful when layered over one another. So, though it now seems like overkill, after doffing all the protective gear on the way out, we also changed into clean clothes in the chilly April parking lot, our modesty shielded by open car doors. We stowed the dirty clothes in plastic bags in the trunk and made liberal use of the giant bottle of hand sanitizer Kelly had brought.

“My mom had a metal sculpture of herself made by artist Karen Rossi. Her four kids are hanging off her feet in mobile-style,” writes Alvin Powell.

The result was that my sister and I were able to sit with my mom for several hours over the weekend. She was mostly asleep or unconscious but roused herself, seeming to rise from a place deep inside, to rasp out that she loved us. Then she retreated inward again.

Mom died the following Monday, and I went into home quarantine for two weeks, breaking it once to head back down the Pike to make arrangements with a completely overwhelmed funeral home. She had wanted to be cremated, but the crematorium was also backed up, so they refrigerated her body for several days until they could get to her. Afterward, my brother, Joe Martelle, picked up her remains and brought her home to await her burial.

But we delayed too. We put off her funeral until the family could gather for the bash she wanted as a farewell — she’d picked out the music and assigned tasks to different family members — Joe and I were to build the wooden box for interment. “August,” I initially thought. Then “October.” I was sure about October. My sister in Sacramento, Laura Lynne Powell, had suggested early on we might have to wait for the April anniversary of her death, which at the time seemed ridiculously distant since the pandemic surely would be controlled by then. Now, of course, April’s here and it is still too early for a big gathering.

In the year since my mother died, I’ve been back at work and have continued to learn as much as I can in order to convey our shifting — yet advancing — knowledge to readers. I’ve been repeatedly reminded how far I still am from “the full COVID experience” because the virus seems insatiable and just keeps on taking.

I don’t for a minute think my family is unique in its impacts, but many of those around me have experienced some ugly aspect of it. My son was laid off; my daughter’s 18th birthday, high school graduation, and freshman year in college have been canceled, delayed, or distorted beyond recognition. Two daughters and four grandchildren have been diagnosed with COVID and recovered. In February, four family friends in my Massachusetts town saw the contagion flare through their households, while my own family in Connecticut watched with concern as a loved one became severely ill, later rejoicing at her recovery after treatment with remdesivir.

The pandemic picture seems to have become even muddier lately, devolving into a foot race between vaccines and variants. Through much of March, vaccines seemed sure to win, but warnings from public health officials have become dire of late, warning of too-soon reopenings and the potential for a fourth surge. My stepfather Sal has gotten his second vaccine dose though, so hopefully he, at least, is out of harm’s way. I’m also hearing of friends and family whose first dose appointments are looming. That gives me hope and serves as a reminder that there is one part of “the full COVID experience” I’m looking forward to: its end.

Alvin Powell is the Harvard Gazette’s senior science writer.

Share this article

You might like.

Longtime supporter of grads Kathy Hanley caps 13-year quest with a Commencement of her own

Class of ’24 gets a do-over on high school prom that pandemic took away

Three major events, including Psychedelics Bootcamp 2024, to be hosted over summer

Epic science inside a cubic millimeter of brain

Researchers publish largest-ever dataset of neural connections

Pop star on one continent, college student on another

Model and musician Kazuma Mitchell managed to (mostly) avoid the spotlight while at Harvard

Finding right mix on campus speech policies

Legal, political scholars discuss balancing personal safety, constitutional rights, academic freedom amid roiling protests, cultural shifts

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 27 January 2021

The effects of social isolation on well-being and life satisfaction during pandemic

- Ruta Clair ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9828-9911 1 ,

- Maya Gordon 1 ,

- Matthew Kroon 1 &

- Carolyn Reilly 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 28 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

98k Accesses

148 Citations

161 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health humanities

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic placed many locations under ‘stay at home” orders and adults simultaneously underwent a form of social isolation that is unprecedented in the modern world. Perceived social isolation can have a significant effect on health and well-being. Further, one can live with others and still experience perceived social isolation. However, there is limited research on psychological well-being during a pandemic. In addition, much of the research is limited to older adult samples. This study examined the effects of perceived social isolation in adults across the age span. Specifically, this study documented the prevalence of social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the various factors that contribute to individuals of all ages feeling more or less isolated while they are required to maintain physical distancing for an extended period of time. Survey data was collected from 309 adults who ranged in age from 18 to 84. The measure consisted of a 42 item survey from the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale, Measures of Social Isolation (Zavaleta et al., 2017 ), and items specifically about the pandemic and demographics. Items included both Likert scale items and open-ended questions. A “snowball” data collection process was used to build the sample. While the entire sample reported at least some perceived social isolation, young adults reported the highest levels of isolation, χ 2 (2) = 27.36, p < 0.001. Perceived social isolation was associated with poor life satisfaction across all domains, as well as work-related stress, and lower trust of institutions. Higher levels of substance use as a coping strategy was also related to higher perceived social isolation. Respondents reporting higher levels of subjective personal risk for COVID-19 also reported higher perceived social isolation. The experience of perceived social isolation has significant negative consequences related to psychological well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

Adults who microdose psychedelics report health related motivations and lower levels of anxiety and depression compared to non-microdosers

Mechanisms linking social media use to adolescent mental health vulnerability

Introduction.

In March 2020, the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic, prompting most governors in the United States to issue stay-at-home orders in an effort to minimize the spread of COVID-19. This was after several months of similar quarantine orders in countries throughout Asia and Europe. As a result, a unique situation arose, in which most of the world’s population was confined to their homes, with only medical staff and other essential workers being allowed to leave their homes on a regular basis. Several studies of previous quarantine episodes have shown that psychological stress reactions may emerge from the experience of physical and social isolation (Brooks et al., 2020 ). In addition to the stress that might arise with social isolation or being restricted to your home, there is also the stress of worrying about contracting COVID-19 and losing loved ones to the disease (Brooks et al., 2020 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ). For many families, this stress is compounded by the challenge of working from home while also caring for children whose schools had been closed in an effort to slow the spread of the disease. While the effects of social isolation has been reported in the literature, little is known about the effects of social isolation during a global pandemic (Galea et al., 2020 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ; Usher et al., 2020 ).

Social isolation is a multi-dimensional construct that can be defined as the inadequate quantity and/or quality of interactions with other people, including those interactions that occur at the individual, group, and/or community level (Nicholson, 2012 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ; Umberson and Karas Montez, 2010 ; Zavaleta et al., 2017 ). Some measures of social isolation focus on external isolation which refers to the frequency of contact or interactions with other people. Other measures focus on internal or perceived social isolation which refers to the person’s perceptions of loneliness, trust, and satisfaction with their relationships. This distinction is important because a person can have the subjective experience of being isolated even when they have frequent contact with other people and conversely they may not feel isolated even when their contact with others is limited (Hughes et al., 2004 ).

When considering the effects of social isolation, it is important to note that the majority of the existing research has focused on the elderly population (Nyqvist et al., 2016 ). This is likely because older adulthood is a time when external isolation is more likely due to various circumstances such as retirement, and limited physical mobility (Umberson and Karas Montez, 2010 ). During the COVID-19 pandemic the need for physical distancing due to virus mitigation efforts has exacerbated the isolation of many older adults (Berg-Weger and Morley, 2020 ; Smith et al., 2020 ) and has exposed younger adults to a similar experience (Brooks et al., 2020 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ). Notably, a few studies have found that young adults report higher levels of loneliness (perceived social isolation) even though their social networks are larger (Child and Lawton, 2019 ; Nyqvist et al., 2016 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ); thus indicating that age may be an important factor to consider in determining how long-term distancing due to COVID-19 will influence people’s perceptions of being socially isolated.

The general pattern in this research is that increased social isolation is associated with decreased life satisfaction, higher levels of depression, and lower levels of psychological well-being (Cacioppo and Cacioppo, 2014 ; Coutin and Knapp, 2017 ; Dahlberg and McKee, 2018 ; Harasemiw et al., 2018 ; Lee and Cagle, 2018 ; Usher et al., 2020 ). Individuals who experience high levels of social isolation may engage in self-protective thinking that can lead to a negative outlook impacting the way individuals interact with others (Cacioppo and Cacioppo, 2014 ). Further, restricting social networks and experiencing elevated levels of social isolation act as mediators that result in elevated negative mood and lower satisfaction with life factors (Harasemiw et al., 2018 ; Zheng et al., 2020 ). The relationship between well-being and feelings of control and satisfaction with one’s environment are related to psychological health (Zheng et al., 2020 ). Dissatisfaction with one’s home, resource scarcity such as food and self-care products, and job instability contribute to social isolation and poor well-being (Zavaleta et al., 2017 ).

Although there are fewer studies with young and middle aged adults, there is some evidence of a similar pattern of greater isolation being associated with negative psychological outcomes for this population (Bergin and Pakenham, 2015 ; Elphinstone, 2018 ; Liu et al., 2019 ; Nicholson, 2012 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ; Usher et al., 2020 ). There is also considerable evidence that social isolation can have a detrimental impact on physical health (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010 ; Steptoe et al., 2013 ). In a meta-analysis of 148 studies examining connections between social relationships and risk of mortality, Holt-Lunstad et al. ( 2010 ) concluded that the influence of social relationships on the risk for death is comparable to the risk caused by other factors like smoking and alcohol use, and greater than the risk associated with obesity and lack of exercise. Likewise, other researchers have highlighted the detrimental impact of social isolation and loneliness on various illnesses, including cardiovascular, inflammatory, neuroendocrine, and cognitive disorders (Bhatti and Haq, 2017 ; Xia and Li, 2018 ). Understanding behavioral factors related to positive and negative copings is essential in providing health guidance to adult populations.

Feelings of belonging and social connection are related to life satisfaction in older adults (Hawton et al., 2011 ; Mellor et al., 2008 ; Nicholson, 2012 ; Victor et al., 2000 ; Xia and Li, 2018 ). While physical distancing initiatives were implemented to save lives by reducing the spread of COVID-19, these results suggest that social isolation can have a negative impact on both mental and physical health that may linger beyond the mitigation orders (Berg-Weger and Morley, 2020 ; Brooks et al., 2020 ; Cava et al., 2005 ; Smith et al., 2020 ; Usher et al., 2020 ). It is therefore important that we document the prevalence of social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the various factors that contribute to individuals of all ages feeling more or less isolated, while they are required to maintain physical distancing for an extended period of time. It was hypothesized that perceived social isolation would not be limited to an older adult population. Further, it was hypothesized that perceived social isolation would be related to individual’s coping with the pandemic. Finally, it was hypothesized that the experience of social isolation would act as a mediator to life satisfaction and basic trust in institutions for individuals across the adult lifespan. The current study was designed to examine the following research questions:

Are there age differences in participants’ perceived social isolation?

Do factors like time spent under required distancing and worry about personal risk for illness have an association with perceived social isolation?

Is perceived social isolation due to quarantine and pandemic mitigation efforts related to life satisfaction?

Is there an association between perceived social isolation and trust of institutions?

Is there a difference in basic stressors and coping during the pandemic for individuals experiencing varying levels of perceived social isolation?

Participants

Participants were adults age 18 years and above. Individuals younger than 18 years were not eligible to participate in the study. There were no limitations on occupation, education, or time under mandatory “stay at home” orders. The researchers sought a sample of adults that was diverse by age, occupation, and ethnicity. The researchers sought a broad sample that would allow researchers to conduct a descriptive quantitative survey study examining factors related to perceived social isolation during the first months of the COVID-19 mitigation efforts.

Participants were asked to complete a 42-item electronic survey that consisted of both Likert-type items and open-ended questions. There were 20 Likert scale items, 3 items on a 3-point scale (1 = Hardly ever to 3 = Often) and 17 items on a 5-point scale (1 = Not at all satisfied to 4 = very satisfied, 0 = I don’t know), 11 multiple choice items, one of which had an available short response answer, and 11 short answer items.

Items were selected from Measures of Social Isolation (Zavaleta et al., 2017 ) that included 27 items to measure feelings of social isolation through the proxy variables of stress, trust, and life satisfaction. Trust was measured for government, business, and media. Life satisfaction examined overall feelings of satisfaction as well as satisfaction with resources such as food, housing, work, and relationships. Three items related to social isolation were chosen from the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale. Hughes et al. ( 2004 ) reported that these three items showed good psychometric validity and reliability for the construct of Loneliness.

There were a further 12 items from the authors specifically about circumstances regarding COVID-19 at the time of the survey. Participants answered questions about the length of time spent distancing from others, level of compliance with local regulations, primary news sources, whether physical distancing was voluntary or mandatory, how many people are in their household, work availability, methods of communication, feelings of personal risk of contracting COVID-19, possible changes in behavior, coping methods, stressors, and whether there are children over the age of 18 staying in the home.

This study was submitted to the Cabrini University Institutional Review Board and approval was obtained in March 2020. Researchers recruited a sample of people that varied by age, gender, and ethnicity by identifying potential participants across academic and non-academic settings using professional contact lists. A “snowball” approach to data gathering was used. The researchers sent the survey to a broad group of adults and requested that the participants send the survey to others they felt would be interested in taking part in research. Recipients received an email that contained a description of the purpose of the study and how the data would be used. Included at the end of the email was a link to the online survey that first presented the study’s consent form. Participants acknowledged informed consent and agreed to participate by opening and completing the survey.

At the end of the survey, participants were given the opportunity to supply an email to participate in a longitudinal study which consists of completing surveys at later dates. In addition, the sample was asked to forward the survey to their contacts who might be interested. Overall, the study took ~10 min to complete.

Demographics

Participants were 309 adults who ranged in age from 18 to 84 ( M = 38.54, s = 18.27). Data was collected beginning in 2020 from late March until early April. At the time of data collection distancing mandates were in place for 64.7% and voluntary for 34.6% of the sample, while 0.6% lived in places which had not yet outlined any pandemic mitigation policies. The average length of time distancing was slightly more than 2 weeks ( M = 14.91 days, s = 4.5) with 30 days as the longest reported time.

The sample identified mostly as female (80.3%), with males (17.8%) and those who preferred not to answer (1.9%) representing smaller numbers. The majority of the sample identified as Caucasian (71.5%). Other ethnic identities reported by participants included Hispanic/Latinx, African-American/Black, Asian/East Asian, Jewish/Jewish White-Passing, Multiracial/Multiethnic, and Country of Origin (Table 1 ). Individuals resided in the United States and Europe.

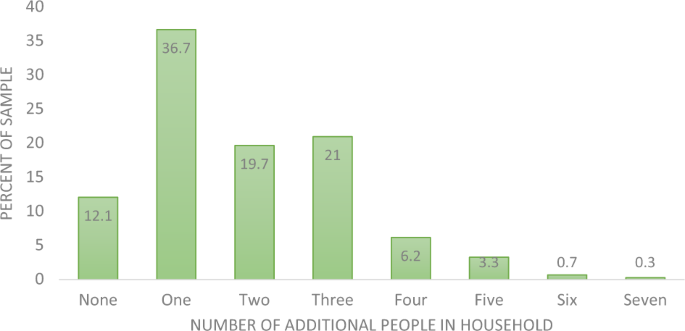

The majority of the sample lived in households with others (Fig. 1 ). More than one-third (36.7%) lived with one other person, 19.7% lived with two others, and 21% lived with three other people. People living alone comprised 12.1% of the sample. When asked about the presence of children under 18 years of age in the home, 20.5% answered yes.

Figure shows how many additional individuals live in the participant’s household in March 2020.

The highest level of education attained ranged from completion of lower secondary school (0.3%) to doctoral level (6.8%). Two thirds of the sample consisted of individuals with a Bachelor’s degree or above (Table 2 ).

Participants were asked to provide their occupation. The largest group identified themselves as professionals (26.5%), while 38.6% reported their field of work (Table 3 ). Students comprised 23.1% of the sample, while 11.1% reported that they were retired. Some of the occupations reported by the sample included nurses and physicians, lawyers, psychologists, teachers, mental health professionals, retail sales, government work, homemakers, artists across types of media, financial analysts, hairdresser, and veterinary support personnel. One person indicated that they were unemployed prior to the pandemic.

Social isolation and demographics

Spearman’s rank-order correlations were used to examine relationships between the three Likert scale items from the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale that measure social isolation. Feeling isolated from others was significantly correlated with lacking companionship ( r s = 0.45, p < 0.001) and feeling left out ( r s = 0.43, p < 0.001). The items related to lacking companionship and feeling left out were also significantly correlated ( r s = 0.39, p < 0.001).

Kruskal–Wallis tests were conducted to determine if the variables of time in required distancing and age were each related to the three levels of social isolation (hardly, sometimes, often). There were no significant findings between perceived social isolation and length of time in required distancing, χ 2 (2) = 0.024, p = 0.98.

A significant relationship was found between perceived social isolation and age, χ 2 (2) = 27.36, p < 0.001). Subsequently, pairwise comparisons were performed using Dunn’s procedure with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Adjusted p values are presented. Post hoc analysis revealed statistically significant differences in age between those with high levels of social isolation (Mdn = 25) and some social isolation (Mdn = 31) ( p = <0.001) and low isolation (Mdn = 46) ( p = 0.002). Higher levels of social isolation were associated with younger age.

Age was then grouped (18–29, 30–49, 50–69, 70+) and a significant relationship was found between social isolation and age, χ 2 (3) = 13.78, p = 0.003). Post hoc analysis revealed statistically significant differences in perceived social isolation across age groups. The youngest adults (age 18–29) reported significantly higher social isolation (Mdn = 2.4) than the two oldest groups (50–69 year olds: Mdn = 1.6, p = 004); age 70 and above: Mdn = 1.57), p = 0.01). The difference between the youngest adults and the next youngest (30–49) was not significant ( p = 0.09).

When asked if participants feel personally at risk for contracting SARS-CoV-2 61.2% reported that they feel at risk. A Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to compare social isolation experienced by those who reported feeling at risk and those who did not feel at risk. Individuals who feel at risk for infection reported more social isolation (Mdn = 2.0) than those that do not feel at risk (Mdn = 1.75), U = 9377, z = −2.43, p = 0.015.

Social isolation and life satisfaction

The relationship between level of social isolation and overall life satisfaction were examined using Kruskal–Wallis tests as the measure consisted of Likert-type items (Table 4 ).

Overall life satisfaction was significantly lower for those who reported greater social isolation ( χ 2 (2) = 50.56, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed statistically significant differences in life satisfaction scores between those with high levels of social isolation (Mdn = 2.82) and some social isolation (Mdn = 3.04) ( p ≤ 0.001) and between high and low isolation (Mdn = 3.47) ( p ≤ 0.001), but not between high levels of social isolation and some social isolation ( p = 0.09).

The pandemic added concern about access to resources such as food and 68% of the sample reported stress related to availability of resources. A significant relationship was found between social isolation and satisfaction with access to food, χ 2 (2) = 21.92, p < 0.001). Individuals reporting high levels of social isolation were the least satisfied with their food situation. Statistical difference were evident between high social isolation (Mdn = 3.28) and some social isolation (Mdn = 3.46) ( p = 0.003) and between high and low isolation (Mdn = 3.69) ( p < 0.001). Reporting higher levels of social isolation is associated with lower satisfaction with food.

As a result of stay at home orders, many participants were spending more time in their residences than prior to the pandemic. A significant relationship was found between social isolation and housing satisfaction, χ 2 (2) = 10.33, p = 0.006). Post hoc analysis revealed statistically a significant difference in housing satisfaction between those with high levels of social isolation (Mdn = 3.49) and low social isolation (Mdn = 3.75) ( p = 0.006). Higher levels of social isolation is associated with lower levels of satisfaction with housing.

Work life changed for many participants and 22% of participants reported job loss as a result of the pandemic. A significant relationship was found between social isolation and work satisfaction, χ 2 (2) = 21.40, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed individuals reporting high social isolation reported much lower satisfaction with work (Mdn = 2.53) than did those reporting low social isolation (Mdn = 3.27) ( p < 0.001) and moderate social isolation (Mdn = 3.03) ( p = 0.003).

Social isolation and trust of institutions

The relationship between social isolation and connection to community was measured using a Kruskal–Wallis test. A significant relationship was found between feelings of social isolation and connection to community ( χ 2 (2) = 13.97, p = 0.001. Post hoc analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in connection to community such that the group reporting higher social isolation (Mdn = 2.27, p = 0.001) reports less connection to their community than the group reporting low social isolation (Mdn = 2.93).

A significant relationship was found between social isolation and trust of central government institutions, χ 2 (2) = 10.46, p = 0.005). Post hoc analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in trust of central government between individuals reporting low social isolation (Mdn = 2.91) and those reporting high social isolation (Mdn = 2.32) ( p = 0.008) and moderate social isolation (Mdn = 2.48) ( p = 0.03). There was less trust of central government for the group reporting high social isolation. However, distrust of central government did not extend to local government institutions. There was no significant difference in trust of local government for low, moderate, and high social isolation groups, χ 2 (2) = 5.92, p = 0.052.

Trust levels of business was significantly different between groups that differed in feelings of social isolation, χ 2 (2) = 9.58, p = 0.008). Post hoc analysis revealed more trust of business institutions for the low social isolation group (Mdn = 3.10) compared to the group reporting high social isolation (Mdn = 2.62) ( p = 0.007).

Sixty-seven participants reported loss of a job as a result of COVID-19. A Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to compare social isolation experienced by those who had lost their job to those who had not. Individuals who experienced job loss reported more social isolation (Mdn = 2.26) than those that did not lose their job (Mdn = 1.80), U = 5819.5, z = −3.66 , p < 0.001.

Stress related to caring for an elderly family member was identified by 12% of the sample. A Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to compare social isolation experienced by those who reported that caring for an elderly family member is a stressor to those who had not. There was no significant finding, U = 4483, z = −1.28, p = 0.20. Similarly, there was no significant effect for caring for a child, U = 3568.5, z = −0.48, p = 0.63.

Coping strategies

Participants were asked to check off whether they were using virtual communication, exercise, going outdoors, and/or substances in order to cope with the challenges of distancing during pandemic. A Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to compare social isolation experienced by those who used substances as a coping strategy and those that did not. Individuals who reported substance use reported more social isolation (Mdn = 2.12) than those that did not (Mdn = 1.80), U = 6724, z = −2.01, p = 0.04.

There was no significant difference on Mann–Whitney U test for social isolation between those individuals who went outdoors to cope with pandemic versus those that did not, U = 5416, z = −0.72, p = 0.47. Similarly, there was no difference in social isolation between those individuals who used exercise as a coping tool and those that did not. Finally, there was no difference in social isolation between those that used virtual communication tools and those that did not, U = 7839.5, z = −0.56, p = 0.58. The only coping strategy which was significantly associated with social isolation was substance use.

While research has explored the subjective experience of social isolation, the novel experience of mass physical distancing as a result of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic suggests that social isolation is a significant factor in the public health crisis. The experience of social isolation has been examined in older populations but less often in middle-age and younger adults (Brooks et al., 2020 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ). Perceived social isolation is related to numerous negative outcomes related to both physical and mental health (Bhatti and Haq, 2017 ; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010 , Victor et al., 2000 ; Xia and Li, 2018 ). Our findings indicate that younger adults in their 20s reported more social isolation than did those individuals aged 50 and older during physical distancing. This supports the findings of Nyqvist et al. ( 2016 ) that found teenagers and young adults in Finland reported greater loneliness than did older adults.

The experience of social isolation is related to a reduction in life satisfaction. Previous research has shown that feelings of social connection are related to general life satisfaction in older adults (Hawton et al., 2011 , Hughes et al., 2004 , Mellor et al., 2008 ; Victor et al., 2000 , Xia and Li, 2018 ). These findings indicate that perceived social isolation can be a significant mediator in life satisfaction and well-being across the adult lifespan during a global health crisis. Individuals reporting higher levels of social isolation experience less satisfaction with the conditions in their home.

During mandated “stay-at-home” conditions, the experience of work changed for many people. For many adults work is an essential aspect of identity and life satisfaction. The experience of individuals reporting elevated social isolation was also related to lower satisfaction with work. This study included a wide span of occupations involving both individuals required to work from home and essential workers continuing to work outside the home. Further, ~22% of the sample ( n = 67) reported job loss as a stressor related to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and reported elevated social isolation. As institutions and businesses consider whether remote work is an economically viable alternative to face-to-face offices once physical distancing mandates are ended, the needs of workers for social interaction should be considered.

Further, individuals reporting higher social isolation also indicated less connection to their community and lower satisfaction with environmental factors such as housing and food. Findings indicate that higher perceived social isolation is associated with broad dissatisfaction across social and life domains and perceptions of personal risk from COVID-19. This supports research that identified a relationship between social isolation and health-related quality of life outcomes (Hawton et al., 2011 , Victor et al., 2000 ). Perceptions of elevated social isolation are related to lower life satisfaction in functional and social domains.

Perceived social isolation is likewise related to trust of some institutions. While there was no effect for local government, individuals with higher perceived social isolation reported less trust of central government and of business. There is an association between higher levels of perceived social isolation and less connection to the community, lower life satisfaction, and less trust of large-scale institutions such as central government and businesses. As a result, the individuals who need the most support may be the most suspicious of the effectiveness of those institutions.

Coping strategies related to exercise, time spent outdoors, and virtual communication were not related to social isolation. However, individuals who reported using substances as a coping strategy reported significantly higher social isolation than did the group who did not indicate substance use as a coping strategy. Perceived social isolation was associated with negative coping rather than positive coping. This study shows that clinicians and health care providers should ask about coping strategies in order to provide effective supports for individuals.