10 Situational Leadership Examples

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

The situational leadership style involves changing one’s leadership style to match the needs of the circumstances and the profiles of the team. It’s all about flexibility.

As circumstances change and the people on a team can be completely different, using one style of leadership is going to be ineffective, maybe even disastrous. Therefore, it is best to be flexible and modify one’s leadership style to match the project and people.

For example, projects can start out as complex and the team unconfident. So, a leader needs to be directive and a skilled motivator and trainer. However, as the project progresses and the team becomes more familiar with the tasks, the leader needs to change and become more hands-off.

Definition of Situational Leadership

According to Hersey and Blanchard (1969), there are four approaches that leaders should adopt based on the characteristics of the team and situational factors .

Each of the following examples can be used by a person with a situational leadership style:

- Telling Style: If the task is simple and routine, then the leader should implement a telling style of leadership. This means they provide a lot of direction and oversight.

- Coaching Style : The coaching style should be used when the team lacks skills and is motivated, so they need training most of all.

- Participating Style: The participating style is useful when the team is experienced and knows what they are doing, but perhaps they need some confidence building.

- Delegating Style: A delegating style is best suited for a team that is self-motivated and highly skilled. They need very little direction or inspiration.

Situational Leadership Examples

1. political campaigning.

Being able to adapt one’s leadership style is like being a bit of a chameleon . Every situation is different, so it is necessary to change one’s colors to match the environment.

In the arena of political campaigns, this usually means modifying political statements to match the voters being spoken to in that moment.

Working with the campaign staff brings another set of challenges. Those that work the phones need a direct, telling style of leadership. Those in charge of soliciting donations from the public may work more efficiently with a delegating approach. The personnel in charge of polling and public affairs may need to be watched more carefully, so implementing a participating style would be wise.

With so many demands needed to be juggled simultaneously, it is no wonder that campaigning is an exhaustive venture that only a few survive.

2. Pat Summitt

Pat Summitt was the women’s basketball coach at the University of Tennessee for 38 years.

During that time, she led her teams to 8 NCAA national championships and coached the US Olympic team in 1984, winning the gold medal.

Although she was known for her tough exterior and a cold stare that would send shivers down anyone’s spine, being able to motivate 10 athletes is no easy feat.

Each player is different and will respond to different approaches. Pat Summitt had a unique ability to modify her approach just enough so that it would produce impressive results.

In addition, a career spanning nearly 40 years means enduring many changes: changes in the game, the rules, player characteristics, the fanbase, and of course, university Athletic Directors and Presidents.

Being able to survive and excel during all of those changes required a style that was able to analyze and adjust on a continuous basis.

3. President of the University Alumni Foundation

The president of a university’s Alumni Foundation plays a multifaceted and hugely important role at any school.

The president needs to form relationships with all alumni, engage in key fundraising efforts, and solicit funding from community leaders and government agencies.

Then there’s also the university president and the Advancement Office. The personality profile of each and every individual that make up those separate groups can be vastly different.

Not only do they have distinct personality characteristics, but each group will also have a different set of priorities and agendas.

Balancing all of those demands requires someone that is an expert in applying a situational leadership style. The university president will respond to a participating style, while the Advancement Office may prefer a hands-off, delegating approach.

Community leaders and government agencies may be completely satisfied with just being told how the money will be spent, a telling style of leadership.

4. Colin Powell

The son of Jamaican immigrants, Colin Powell was a U.S. general in the military and a political statesman.

He served as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and Secretary of State, being the first African American to hold either position. His career was long and varied. He was known for his calm demeanor and moderate views, even when encircled by hard-liners and volatile personalities.

During his service he worked with a wide range of individuals, from soldiers, to commanders, to diplomats and the leaders of nations from all over the world. In his own words he characterizes his leadership as: “I am a situational leader, and I adjust my style, within limits, to the strengths and weaknesses of my subordinates.”

5. Primary School Principal

Managing a primary school can be both a joy and a pressure-packed occupation.

Teachers of first grade are quite different from those teaching six-graders. Similarly, biology teachers have completely different personalities from art and music teachers.

Balancing government requirements and educational standards, with the wants and needs of a large teaching staff is a continuous balancing act. Throw in the concerns of protective and demanding parents, and it is now wonder that principals need good medical insurance.

It is a job where the circumstances and people that must be dealt with can change on an hourly basis.

Some teachers may work best when the principal is a servant leader , while other teachers may actually prefer a more direct, telling autocratic leadership style . At the same time, most parents want to feel included, so the principal should exercise his participating style of leadership when meeting with them.

6. Phil Jackson, NBA Coach

Phil Jackson will go down in history as one of the greatest NBA coaches of all time and a truly transformational leader . He won a total of 11 national championships with two different teams.

During his many years, he coached some of the greatest basketball players in history: Michael Jordan, Dennis Rodman, Scottie Pippen, Kobe Bryant, and Shaquille O’Neal.

Each of those greats were about as different as you could possibly imagine. Their personalities, temperaments , and style of play were all distinct.

Yet, he managed to motivate each one. He turned each player into the best possible version of themselves by utilizing his unique ability to understand each one as an individual.

For one player, he utilized a telling style, while for another that he trusted thoroughly, he delegated. At the same time, maybe even in the same huddle, he would adopt a participatory leadership style and seek the input of his most experienced player.

7. Producing a Video Game

The video game industry is vast and involves huge profits for companies that can produce a great game that really strikes a chord with players.

Today’s games can be incredibly realistic and be played simultaneously by different people from around the world.

Producing a successful video game is not a matter of luck. It requires multiple teams of individuals with a wide range of skillsets.

Programmers, storyline creators, graphic designers and tech specialists are all very different types of people. Some will need to be dealt with in a coaching style, while others may need more of a delegating approach.

Customizing one’s approach to match the personalities and abilities of various members of the team takes a unique individual. The project manager will have to switch from a coaching style to a participating style, and then later to a delegating style as the project progresses.

8. Professional Development

Professional development helps employees build or refine job-specific skills that are relevant to their career or a particular project.

For example, if the situational leader has determined that his team is highly motivated, but lack the necessary skills to get the job done, they may see to it that the team receives the necessary training (e.g., a coaching style of leadership).

The training could be in the area of technology, communication skills, project management, creativity and innovative thinking, or how to utilize certain software programs.

By participating in the training program, the staff will be better able to carry-out the project successfully. The key idea is that it takes a situational leadership mindset to recognize the needs of the project and characteristics of the team to know what is require to complete a successful project.

9. Hospitality Management

Managing a five-star hotel seems like it would be one of the most wonderful jobs in the world.

The working environment is luxurious, the locations are exotic, the guests sophisticated, and the lunch breaks delicious.

But if we take a step back, we see an ecosystem that is quite complex. Head chefs are known to be demanding and meticulous, while the wait staff are people-oriented and accommodating.

The accountant that does the books is quiet and hard to read, while the band that plays nightly is a group of extroverted partiers prone to getting into trouble.

The people that work the reception all want your job, and another term for “sophisticated guests” is “unreasonably picky”. Since the hotel is in an exotic location, it means adjusting to a culture that may take years to understand.

Adjusting one’s leadership style is sometimes like playing a never-ending game of management Tetris.

10. Jack Stahl, CEO of Coca-Cola and Revlon

Jack Stahl has been CEO of the world’s most respected multinational corporations, at Coca-Cola (1978–2000) and Revlon (2002–2006). Those are two completely different companies with vastly different customer bases and product lines.

As he explains in this interview with Strategy+Business , he has a very clear appreciation of situational leadership, stating that “… management is not a popularity contest…As a leader, once you see that people are doing that (focusing on details) successfully, then you pull back and worry about things from a more strategic perspective. ”

Stahl is a firm believer in situational leadership. He goes on to state that in his opinion, a solid leader needs to be “… able to step into any circumstance and recognize whether they need to engage at the strategy level or dive into the nitty-gritty ”.

Any great leader understands that most projects are complex and fluid. Circumstances change and the individuals on the team all have unique personalities and skillsets.

That is why Hersey and Blachard (1969) developed the situational leadership model, a leadership concept which postulates that there is no single best leadership style example . A good leader should adapt their style to the demands of the situation and people on their team.

Based on that analysis, one of four leadership styles should be exercised: telling, coaching, participating or delegating . Each of these four styles vary in terms of their task or people orientation.

Being flexible maximizes results and leads to success. That is why some of the most successful leaders in the world practice a situational leadership style.

Hersey, P., & Blanchard, K. H. (1969). Life cycle theory of leadership. Training & Development Journal, 23 (5), 26-34.

Prewitt, M. (2007, September). The situational leader. Strategy+Business. Retrieved from https://www.strategy-business.com/article/li00042

Rabarison, K., Ingram, R. C., & Holsinger, J. W., Jr (2013). Application of situational leadership to the national voluntary public health accreditation process. Frontiers in Public Health , 1 , 26. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2013.00026

Sims Jr., H. P., Faraj, S., & Yun, S. (2009). When Should a Leader Be Directive or Empowering? How to Develop Your Own Situational Theory of Leadership. Business Horizons, 52 , 149-158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2008.10.002

Vroom, V. H., & Jago, A. G. (2007). The role of the situation in leadership. The American Psychologist , 62 (1), 17–47. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.1.17

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 18 Adaptive Behavior Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

PERSPECTIVE article

Application of situational leadership to the national voluntary public health accreditation process.

- College of Public Health, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA

Successful navigation through the accreditation process developed by the Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB) requires strong and effective leadership. Situational leadership, a contingency theory of leadership, frequently taught in the public health classroom, has utility for leading a public health agency through this process. As a public health agency pursues accreditation, staff members progress from being uncertain and unfamiliar with the process to being knowledgeable and confident in their ability to fulfill the accreditation requirements. Situational leadership provides a framework that allows leaders to match their leadership styles to the needs of agency personnel. In this paper, the application of situational leadership to accreditation is demonstrated by tracking the process at a progressive Kentucky county public health agency that served as a PHAB beta test site.

Introduction

The mission of public health, as identified by the 1988 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, The Future of Public Health , is “assuring conditions in which people can be healthy” ( 1 ). A strong infrastructure is central to the mission of public health, since it supports the delivery of key public health services. The critical role infrastructure plays in assuring public health is underscored in a 2003 IOM follow up report that identified strengthening governmental public health institutions as an essential area of action for the twenty-first century. The 2003 report highlighted the key role that leadership plays in maintaining a strong public health system through the development of a competent public health workforce. It also identified the importance of leadership in such specific recommendations as making “leadership training, support, and development” a high priority for all governmental public health agencies, schools of public health, and the other entities within the public health system ( 2 ).

Successful leadership is contingent upon developing a clear mission and executing a vision to guide progress ( 3 ). Various frameworks have been developed to guide public health leaders in developing a mission and vision, including the three Core Functions of Public Health and the 10 Essential Public Health Services (EPHS) ( 4 ). While these frameworks are useful, they are macro-contextual, and may be disconnected from the day to day operations of a public health agency. The accreditation standards and measures developed by The Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB) provide specific benchmarks to be utilized by agencies as a framework to guide their activities. While PHAB’s standards and measures can be used to guide organizational leadership, the changes associated with accreditation require strong leadership and an immediate short-term strategic plan and long-term vision based on effectiveness, efficiency, and sustainability.

Academic public health programs, as part of their curricula, educate students in leadership theories and models, and often include skill training at both the masters and doctoral levels. Students of public health rarely are provided the opportunity to practice the leadership skills developed in the classroom or to test leadership theories in real world situations prior to degree completion. This article discusses one opportunity to transfer leadership theory and practice from the classroom to the practice setting. In this instance, practice based field experience provided a public health doctoral student the opportunity to utilize concepts learned in the classroom in a practice setting, and develop a case study, based on initial and follow up interviews with public health agency personnel, focused on leadership in the context of preparing for participation in a Beta Test of the PHAB pilot standards and measures.

Situational Leadership

Situational leadership theory suggests that leaders should adapt their leadership styles based on the readiness, current skills, and developmental level of team members ( 5 ). It provides the leader with the flexibility to assess the situation and adopt a leadership style that best fits the needs of the follower. It is particularly well suited to leading public health agencies through the accreditation process as will be demonstrated.

Utilizing Situational Leadership requires leaders to be aware of the perceptions of their followers. What leaders say they do is one thing; what followers say they want and how well their leaders meet their expectations is another ( 6 ). Given the novelty of accreditation, and the potential anxiety engendered during the different phases of the process, public health leaders need to be aware of and adapt their leadership styles to match the readiness, current skills, and developmental status of the team members engaged in accreditation, allowing the agency to successfully navigate this intricate process.

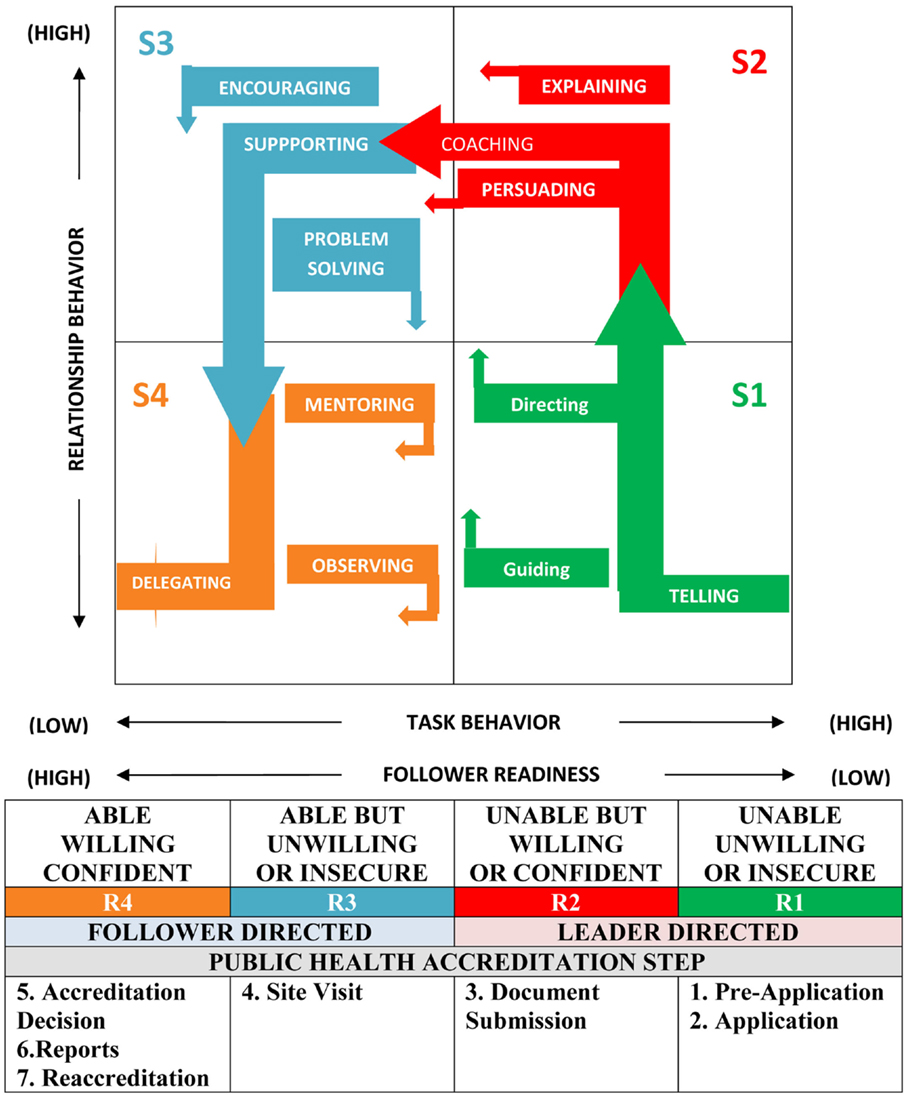

Situational leadership is based on two behavioral categories: task behavior and relational behavior. Task behavior is “the extent to which the leader engages in spelling out the duties and responsibilities of an individual or group” ( 7 ). Relational behavior is “the extent to which the leader engages in two-way or multi-way communication if there is more than one person” ( 7 ). Thus, situational leadership provides a balance between (1) guidance and direction (task behavior), (2) socio-emotional support (relational behavior), and (3) the readiness level followers exhibit for a specific task ( 5 ). The leadership styles of situational leadership include:

1. Style 1 (S1) “Directing” characterized by “high task and low relationship” behaviors;

2. Style 2 (S2) “Coaching” characterized by “high task and high relationship” behaviors;

3. Style 3 (S3) “Participating” characterized by “high relationship and low task” behaviors;

4. Style 4 (S4) “Delegating” characterized by “low relationship and low task” behavior ( 5 ) (see Figure 1 ).

Figure 1. Situational leadership and public health accreditation . Adapted from Ref. ( 5 ).

In situational leadership, readiness is defined as “the extent to which a follower demonstrates the ability and willingness to accomplish a specific task” ( 5 ). The major components of readiness are ability defined as “the knowledge, experience, and skill that an individual or a group brings to a particular task or activity,” and willingness is defined as “the extent to which an individual or a group has the confidence, commitment, and motivation to accomplish a specific task” ( 5 ). As seen in Figure 1 , follower readiness is a continuum from low to high as followers develop ability and willingness. Leaders match their leadership style to the readiness level of their followers as follows:

1. Level 1 (R1) occurs when the follower is “unable and unwilling” to perform the task and lacks confidence, motivation, and commitment;

2. Level 2 (R2) occurs when the follower is “unable but willing” to perform the task and requires some guidance;

3. Level 3 (R3) occurs when the follower is “able but unwilling” to complete the task, possibly because of insecurity; and

4. Level 4 (R4) occurs when the follower is “willing and able” to accomplish the task with confidence ( 5 ) (see Figure 1 ).

Situational Leadership and Public Health Accreditation: A Local Health Agency Case Study

While accreditation is not a new concept in the American health sector [initiatives such as The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) have been a part of the health care system for decades], it is a new phenomenon in public health practice in the United States. Informal discussions concerning the accreditation of public health agencies have occurred for some time; however, accreditation received a significant boost from The Future of the Public’s Health in the Twenty-First Century , which stated that “despite the controversies concerning accreditation, greater accountability is needed on the part of state and local health agencies with regard to the performance of the core public health functions of assessment, assurance, and policy development and the EPHS” ( 8 ). This report led to the creation of the Exploring Accreditation project in 2004, the creation of PHAB in 2007, and ultimately the release of PHAB’s standards and measures for voluntary national accreditation in 2011.

Accreditation is a useful tool for improving the quality of services provided to the public by setting standards and evaluating performance against those standards, and has been shown to be associated with higher performing health systems. In a working paper for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), Mays demonstrated that clinical quality measures for care of myocardial infarctions were lower and mortality rates higher in hospitals not participating in JCAHO accreditation when compared to JCAHO accredited healthcare facilities ( 9 ). It may be postulated that accreditation of public health agencies will have a similar effect. PHAB states that its program is intended to develop and maintain “a high-performing governmental public health system that will make us the healthiest nation.” Thus, PHAB “is dedicated to promote, improve, and protect the health of the public by advancing the quality and performance of state, local, tribal, and territorial public health departments in the United States” ( 10 ).

The PHAB accreditation process has seven steps; Pre-application, Application, Documentation Selection and Submission, Site Visit, Accreditation Decision, Reports, and Reaccreditation; and was developed after extensive review and revision, including a beta test of the process, which included 30 state, tribal, and local public health agencies ( 10 , 11 ). Following an interview with the director of a local public health agency regarding the agency’s experience as a beta test site, the authors noted that the agency’s accreditation experience closely matched the four situational leadership styles in relationship to the stages of follower readiness displayed in Figure 1 . As a result, a follow up interview was completed to confirm these findings, and to further discuss the application of situational leadership to the accreditation process.

The agency was well prepared for accreditation given its previous commitment to continuous quality improvement, as evidenced by its application to be a beta test site. In addition, the agency director was a member of the Kentucky Department of Public Health Quality Improvement Team prior to accepting her current position ( 12 ). This agency is also committed to performance measurement and management, having completed in 2008 a local public health system performance assessment that demonstrated a relatively high (69%) score in the overall performance of the EPHS ( 12 ).

During the initial interview with the agency director, it was apparent that leadership was viewed as a key element to accreditation success. Fostering complete organizational commitment to the process was of particular importance, including high commitment from contract and part time employes, as well as members of the local board of health.

Early in the accreditation process, particularly during the pre-application and application stages, and partially during document submission, the agency staff was relatively unfamiliar with the accreditation process (R1 follower readiness level as depicted in Figure 1 ), necessitating that the agency director engage in leader directed activities, primarily those shown in the S1 area in Figure 1 . Such actions involved informing the agency staff of the requirements and processes of accreditation and directing them through the process with high task behaviors answering the question: what is public health accreditation? She utilized a directing style of leadership dealing with questions such as who, what, when, where, and how.

As agency staff members developed an understanding of the value of accreditation and gained some confidence through identifying their roles in the process and the documents necessary for review, they transitioned to an R2 stage of follower readiness as depicted in Figure 1 , resulting in the director continuing highly directive behavior while adding high relationship behavior as well. A coaching, persuading, and/or explaining leadership style (S2 quadrant of the diagram) became important. While the leadership style was still high task, moving from direction to explanation occurred in order to answer the question, “Why is accreditation important to our agency?”.

By the time the agency was ready for document submission its personnel had sufficient confidence to transition fully to the R2 stage of readiness. There were still gaps in knowledge and ability related to the accreditation process, thus necessitating a continuation of the S2 leadership style, including coaching, explaining, and continuously persuading public health agency staff members of the value of accreditation and the importance of each individual’s role in the agency’s effort.

By the time the agency reached the PHAB’s beta test site visit phase, it had reached an R3 stage of readiness as depicted in Figure 1 . As a result, leadership style was based on high relationship, low task behaviors characterized by quadrant S3. These follower-directed behaviors revolved primarily around encouraging and championing the efforts of a highly participatory agency staff, with agency leaders assuming the role of problem solvers instead of being more highly task oriented.

By the conclusion of the PHAB beta test experience, when mock accreditation feedback was provided, the agency staff members had developed to an R4 stage of readiness. The agency staff was able, willing, and confident with respect to accreditation. As a result, the leader’s style had shifted to a low task and low relational behavior approach as described by quadrant S4. The director successfully delegated the accreditation coordination task to an accreditation coordinator, thus serving as an engaged mentor.

The PHAB beta test experience allowed the agency to further develop its quality improvement, performance measurement, and management infrastructure. The agency had successfully completed the three prerequisites of PHAB accreditation by developing a community health assessment, a community health improvement plan, and a refined strategic plan with clear mission and vision statements that were ready to be adopted. In addition, a 12 member accreditation team had been formed, being led by the full time accreditation coordinator.

As a result of the commitment and intense preparation exhibited by the staff, on February 28, 2013, the agency was awarded 5-year accreditation status by PHAB. 1 Accreditation of the agency was a direct result of the leadership exhibited by the agency’s senior leadership. The accreditation result was based on the development of a high-performing team founded on full collaboration between staff members and leaders. The use of a situational leadership approach contributed to team development. Conflict resolution was more readily accomplished by the leaders’ understanding of the needs of the staff members and the leaders’ ability to utilize an appropriate leadership style to meet the staff members’ needs. Due to the nature of the PHAB accrediting process, no ethical issues were raised by staff members during the beta test experience.

Situational leadership theory and skills learned in the classroom were effective in understanding the leadership required to effectively guide a public health agency through the process of preparing for PHAB accreditation. This theory of leadership is an appropriate approach for leading the accreditation process due to its flexibility as a follower driven model of leadership. Given the novelty and the complexity of the accreditation process, a highly functioning team is required and situational leadership provides a framework for public health agency leaders to successfully guide their teams through the process. Use of situational leadership will ensure that public health agencies successfully develop an ongoing quality improvement and performance standards plan throughout the accreditation process. Thus, a classroom leadership theory was found to be useful as an approach to being faithful to public health’s mission to “assure conditions in which people can be healthy” ( 1 ).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

- ^ http://www.phaboard.org/news-room/accredited-health-departments

1. Institute of Medicine Committee on the Study for the Future of Public Health. The Future of Public Health . Washington, DC: National Academy Press (1988).

2. Institute of Medicine Committee on Assuring the Health of the Public in the 21st Century. The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century . Washington, DC: National Academies Press (2003).

3. Jaques E. Requisite Organization: A Total System for Effective Managerial Organization and Managerial Leadership for the 21st Century . Arlington, VA: Cason Hall (1998).

4. The Core Public Health Functions Steering Committee. 10 Essential Public Health Services. (1994). Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nphpsp/essentialservices.html

5. Hersey P, Blanchard KH, Johnson DE. Management of Organizationl Behavior – Leading Human Resources. 9th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall (2008).

6. Kouzes JM, Posner BZ. Follower-oriented leadership. In: Goethals GR, Sorenson GJ, Burns JM, editors. Encyclopedia of Leadership . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications (2004). p. 494–8.

7. Hersey P. The Situational Leader – The Other 59 Minutes . New York: Warner Books (1984).

8. Mays GP. Can accreditation work in public health? Lessons from other service industries. Working Paper Prepared for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation ; 2004 Nov 30. New Jersey: Princeton (2004).

9. Public Health Accreditation Board. Public Health Board Guide to National Accreditation Public Health Accreditation Board – Version 1.0 . Alexandria, VA: PHAB (2011). Available from: http://dl.dropbox.com/u/12758866/PHAB%20Guide%20to%20National%20Public% 20Health%20Department%20Accreditation%20Version%201.0.pdf.

10. Public Health Accreditation Board. Evaluation of the Public Health Accreditation Board Beta Test . Alexandria, VA: PHAB (2011). Available from: http://www.phaboard.org/wp-content/uploads/EvaluationofthePHABBetaTestBriefReportAugust2011.pdf

11. Rabarison K. Conversation with Health Director . Frankfort, KY: Franklin County Health Department (2011).

12. Franklin County Health Department. Local Public Health System Performance Assessment – Report of Results . Frankfort, KY: Franklin County Health Department (2008). Available from: http://www.fchd.org/Portals/60/NPHPSP%20results%20.pdf

Keywords: situational leadership, public health accreditation, accreditation, leadership, student training

Citation: Rabarison K, Ingram RC and Holsinger JW Jr (2013) Application of situational leadership to the national voluntary public health accreditation process. Front. Public Health 1 :26. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2013.00026

Received: 05 June 2013; Accepted: 31 July 2013; Published online: 12 August 2013.

Reviewed by:

Copyright: © 2013 Rabarison, Ingram and Holsinger. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: James W. Holsinger Jr, College of Public Health, University of Kentucky, 111 Washington Avenue, Lexington, KY 40536-0003, USA e-mail: jwh@uky.edu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, situational leadership during the post-pandemic crisis: a case of amanah institute.

Publication date: 15 April 2024

Teaching notes

Learning outcomes.

After completion of the case study, students will be able to learn, understand, examine and customize leadership styles per organizational culture; understand the conflict management styles of a female leader; and comprehend the organizational change process to devise an effective communication strategy.

Case overview/synopsis

Ever-changing business demands managers adopt organizational change in leadership styles, business processes, updated skill sets and minds. One must be ready to understand influential nurtured corporate culture and human resource resistance towards the inevitable change. This case study attempted to discuss the female protagonist dealing with an organizational conflict. The case study introduces one such protagonist from a century-old woman’s educational institution. Subsequently, this case study presents organizational change under the leadership of a female protagonist. This teaching case study gives the reader an insight into situational leadership, conflict management styles and the corporate change process by implementing an appropriate communication strategy. This case study describes the change process through the various decision-making scenarios that an academic institute over a century old faced during the post-pandemic crisis after adding a crucial protagonist. The employee union, followed by students and administrative employees, has challenged the dominating leadership position held by the college principal. Protests occurred due to the college administrator’s refusal to adjust her approach to leadership. This teaching case then provided different leadership styles of the current and old leaders. Finally, the case study lists the challenges a leader faces during turbulent times and the lessons a leader should learn from such situations while transforming the institute.

Complexity academic level

The teaching case benefits undergraduate students in business management subjects such as conflict management, leadership and organizational behaviour. Nevertheless, trainers can use this case study to teach seasoned managers and emerging leaders the significance of adopting and implementing change while understanding situational leadership.

Supplementary materials

Teaching notes are available for educators only.

Subject code

CSS 10: Public Sector Management.

- Employee communications

- Corporate culture

Acknowledgements

Disclaimer. This case is intended to be used as the basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a management situation. The case was compiled from published sources.

Saleem, I. , Ashfaq, M. and Ul-Durar, S. (2024), "Situational leadership during the post-pandemic crisis: a case of Amanah Institute", , Vol. 14 No. 2. https://doi.org/10.1108/EEMCS-07-2023-0267

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2024, Emerald Publishing Limited

You do not currently have access to these teaching notes. Teaching notes are available for teaching faculty at subscribing institutions. Teaching notes accompany case studies with suggested learning objectives, classroom methods and potential assignment questions. They support dynamic classroom discussion to help develop student's analytical skills.

Related articles

All feedback is valuable.

Please share your general feedback

Report an issue or find answers to frequently asked questions

Contact Customer Support

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Situational Leadership Theory

Verywell / Nez Riaz

Situational Leadership II

Elements of situational leadership theory, frequently asked questions.

Situational leadership theory suggests that no single leadership style is best. Instead, it depends on which type of leadership and strategies are best suited to the task.

According to this theory, the most effective leaders are those that are able to adapt their style to the situation and look at cues such as the type of task, the nature of the group, and other factors that might contribute to getting the job done.

Situational leadership theory is often referred to as the Hersey-Blanchard Situational Leadership Theory, after its developers, Dr. Paul Hersey, author of "The Situational Leader," and Kenneth Blanchard, author of "One-Minute Manager."

Leadership Styles

Hersey and Blanchard suggested that there are four primary leadership styles:

- Telling (S1) : In this leadership style, the leader tells people what to do and how to do it.

- Selling (S2) : This style involves more back-and-forth between leaders and followers . Leaders "sell" their ideas and message to get group members to buy into the process.

- Participating (S3) : In this approach, the leader offers less direction and allows members of the group to take a more active role in coming up with ideas and making decisions.

- Delegating (S4) : This style is characterized by a less involved, hands-off approach to leadership . Group members tend to make most of the decisions and take most of the responsibility for what happens.

Maturity Levels

The right style of leadership depends greatly on the maturity level (i.e., the level of knowledge and competence) of the individuals or group.

Hersey and Blanchard's theory identifies four different levels of maturity, including:

- M1 : Group members lack the knowledge, skills, and willingness to complete the task.

- M2 : Group members are willing and enthusiastic, but lack the ability.

- M3 : Group members have the skills and capability to complete the task, but are unwilling to take responsibility.

- M4 : Group members are highly skilled and willing to complete the task.

Matching Styles and Levels

Leadership styles may be matched with maturity levels. The Hersey-Blanchard model suggests that the following leadership styles are the most appropriate for these maturity levels:

- Low Maturity (M1)—Telling (S1)

- Medium Maturity (M2)—Selling (S2)

- Medium Maturity (M3)—Participating (S3)

- High Maturity (M4)—Delegating (S4)

How It Works

A more "telling" style may be necessary at the beginning of a project when followers lack the responsibility or knowledge to work on their own. As subordinates become more experienced and knowledgeable, however, the leader may want to shift into a more delegating approach.

This situational model of leadership focuses on flexibility so that leaders are able to adapt according to the needs of their followers and the demands of the situation.

The situational approach to leadership also avoids the pitfalls of the single-style approach by recognizing that there are many different ways of dealing with a problem and that leaders need to be able to assess a situation and the maturity levels of subordinates in order to determine what approach will be the most effective at any given moment.

Situational theories , therefore, give greater consideration to the complexity of dynamic social situations and the many individuals acting in different roles who will ultimately contribute to the outcome.

The Situational Leadership II (or SLII model) was developed by Kenneth Blanchard and builds on Blanchard and Hersey's original theory. According to the revised version of the theory, effective leaders must base their behavior on the developmental level of group members for specific tasks.

Competence and Commitment

The developmental level is determined by each individual's level of competence and commitment. These levels include:

- Enthusiastic beginner (D1) : High commitment, low competence

- Disillusioned learner (D2) : Some competence, but setbacks have led to low commitment

- Capable but cautious performer (D3) : Competence is growing, but the level of commitment varies

- Self-reliant achiever (D4) : High competence and commitment

SLII Leadership Styles

SLII also suggests that effective leadership is dependent on two key behaviors: supporting and directing. Directing behaviors include giving specific directions and instructions and attempting to control the behavior of group members. Supporting behaviors include actions such as encouraging subordinates, listening, and offering recognition and feedback.

The theory identifies four situational leadership styles:

- Directing (S1) : High on directing behaviors, low on supporting behaviors

- Coaching (S2) : High on both directing and supporting behaviors

- Supporting (S3) : Low on directing behavior and high on supporting behaviors

- Delegating (S4) : Low on both directing and supporting behaviors

The main point of SLII theory is that not one of these four leadership styles is best. Instead, an effective leader will match their behavior to the developmental skill of each subordinate for the task at hand.

Experts suggest that there are four key contextual factors that leaders must be aware of when making an assessment of the situation.

Consider the Relationship

Leaders need to consider the relationship between the leaders and the members of the group. Social and interpersonal factors can play a role in determining which approach is best.

For example, a group that lacks efficiency and productivity might benefit from a style that emphasizes order, rules, and clearly defined roles. A productive group of highly skilled workers, on the other hand, might benefit from a more democratic style that allows group members to work independently and have input in organizational decisions.

Consider the Task

The leader needs to consider the task itself. Tasks can range from simple to complex, but the leader needs to have a clear idea of exactly what the task entails in order to determine if it has been successfully and competently accomplished.

Consider the Level of Authority

The level of authority the leader has over group members should also be considered. Some leaders have power conferred by the position itself, such as the capacity to fire, hire, reward, or reprimand subordinates.

Other leaders gain power through relationships with employees, often by gaining respect from them, offering support to them, and helping them feel included in the decision-making process .

Consider the Level of Maturity

As the Hersey-Blanchard model suggests, leaders need to consider the level of maturity of each individual group member. The maturity level is a measure of an individual's ability to complete a task, as well as their willingness to complete the task . Assigning a job to a member who is willing but lacks the ability is a recipe for failure.

Being able to pinpoint each employee's level of maturity allows the leader to choose the best leadership approach to help employees accomplish their goals.

An example of situational leadership would be a leader adapting their approach based on the needs of their team members. One team member might be less experienced and require more oversight, while another might be more knowledgable and capable of working independently.

In order to lead effectively, the three skills needed to utilize situational leadership are diagnosis, flexibility, and communication. Leaders must be able to evaluate the situation, adapt as needed, and communicate their expectations with members of the group.

Important elements of situational leadership theory are the styles of leadership that are used, the developmental level of team members, the adaptability of the leader, communication with group members, and the attainment of the group's goals.

- DuBrin AJ. Leadership: Research, Findings, Practice, and Skills. Mason, OH: South-Western, Cengage Learning; 2013.

- Gill R. Theory and Practice of Leadership. London: Sage Publications; 2011.

- Hersey P, Blanchard KH. Management of Organizational Behavior — Utilizing Human Resources . New Jersey/Prentice Hall; 1969.

- Hersey P, Blanchard KH. Life Cycle Theory of Leadership. Training and Development Journal. 1969;23(5):26–34.

- Nevarez C, Wood JL, Penrose R. Leadership Theory and the Community College: Applying Theory to Practice. Sterling, Virginia: Stylus Publishing; 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Advising Jay: A Case Study Using a Situational Leadership Approach

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Alan C. Lerstrom; Advising Jay: A Case Study Using a Situational Leadership Approach. NACADA Journal 1 September 2008; 28 (2): 21–27. doi: https://doi.org/10.12930/0271-9517-28.2.21

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Through a case study, I address the position that academic advising can be viewed as a developmental process. I present my specific experiences in applying Hersey and Blanchard's model of situational leadership (1969) during academic advising sessions. The model demonstrates that effective leadership is based on the appropriate balance of a leader's task and relationship behaviors. The leader's emphasis of either the task or the relationship behavior depends on the maturity or readiness of the follower.

Relative Emphasis: theory, practice, research

Author notes

Alan C. Lerstrom (PhD from the University of Kansas) is an associate professor in the Communication Studies Department at Luther College. E-Mail: [email protected] .

Citing articles via

Get email alerts, affiliations.

- eISSN 2330-3840

- ISSN 0271-9517

- Privacy Policy

- Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

New Normal: Emergence of Situational Leadership During COVID-19 and Its Impact on Work Motivation and Job Satisfaction

Sarfraz aslam.

1 School of Foreign Languages, Yulin University, Yulin, China

Atif Saleem

2 College of Teacher Education, College of Education and Human Development, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua, China

Tribhuwan Kumar

3 Department of English Language and Literature, College of Science and Humanities at Sulail, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Al Kharj, Saudi Arabia

Khalida Parveen

4 Faculty of Education, Southwest University, Chongqing, China

Introduction

Globally, COVID-19 has caused rapid changes in the workplace (Kirby, 2020 ). COVID-19 has disrupted the standard working order of all organizations, including educational, health, business, etc. This has affected workers' motivation and job satisfaction. Suffering and challenges reduce workers' happiness and productivity (Singh and Mishra, 2020 ). Motivation at work is an essential criterion for a healthy organization, particularly in an epidemic context (Wang et al., 2021 ). We need to employ new leadership behaviors that harness uncertainty to improve employee motivation and job satisfaction. This article provides theoretical support and practical reference for organizations to cultivate situational leadership and eliminate employees' exhaustion to improve work motivation and job satisfaction.

COVID-19 and Leadership

COVID-19 has affected governments globally, and societies are experiencing an odd situation; after the global pandemic, this situation led to a global crisis that touched the aspect of our lives, including family, education, health, work, and the relationship between leaders and followers in our society (Hinojosa et al., 2020 ; Aslam et al., 2021 ; Parveen et al., 2022a ). Organization leaders play a critical role in framing employee experiences at the workplace during and after the pandemic as they adapt to work on new realities (Ngoma et al., 2021 ). The managerial level of communication of those who lead still has a substantial impact on their followers' performance, behavior, and mental health (Wu and Parker, 2017 ; Saleem et al., 2020 ; Parveen et al., 2022b ).

“New Normal” has been used since the end of World War II (Francisco and Nuqui, 2020 ). An indispensable leader knows how to do ordinary things well; an unafraid leader acts regardless of criticism and never backs down (Honore and Robinson, 2012 ). Nevertheless, the new normal in 2020 is different since the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the world's economy and education. This is an uphill battle in which education and money are at stake in a situation where people find it challenging to adjust. This shift in working and learning space is defined as the New Normal in working organizations (Mollenkopf et al., 2020 ). It is moving from a public to a private space, shifting from one-size-fits-all methods to individualized and differentiated learning, shifting responsibility. Active participation of household members is required for this learning process and for evaluating learning shifts (Francisco and Nuqui, 2020 ).

Herein, in this study, we examine: how organizations attain excellent performance in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic through a situational leadership approach?

The human resource department is one of the most important aspects of any organization. Organizations, irrespective of their form and goals, are based on various visions for the benefit of humans. Additionally, the process is by implementing its mission and is handled by humans. To achieve performance superiority, any organization should concentrate on brilliant employees. The impact of globalization on knowledge and technology progress in many different areas is incomprehensible. It is indispensable for the management of human resources to be among the most critical organizational assets since it plays a significant role in developing and achieving organization objectives (Syaifuddin and Sidu, 2019 ).

Social Exchange Theory (SET)

Organizational behavior theories such as SET (Blau, 1964 ) are the most influential approach (Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005 ). According to SET (Gouldner, 1960 ), a good deed performed by a leader engenders positive behaviors by the opposite party (a subordinate). Leaders who serve as role models are likely to feel obligated to their duties and show greater interest in their assigned tasks (Liborius, 2014 ). Using the social exchange perspective, employees whose leaders encourage them through participative leadership behaviors, such as participation in decision-making and increased responsibility, may thrive more and offer helpful behavior toward coworkers due to this increased autonomy (Usman et al., 2021 ).

Nature of Situational Leadership

Leadership style is a person's approach to influencing others through their behavior pattern. The directive, as well as supportive behavior, compose this leadership style. A directive behavior encourages group members to achieve goals by providing direction, setting goals and providing evaluation methods, defining roles, assigning deadlines, showing how they will accomplish the objectives, and establishing timelines, which are spelled out, often through one-way communication. Group members who exhibit supportive behaviors are more likely to feel comfortable in their group, coworkers, and situation. Social and emotional support is demonstrated through supportive behaviors; supportive behaviors demand two-way communication (Northouse, 2021 ). Providing direction, implementing and monitoring plans, and motivating team members are aspects of a leadership style (Hourston, 2013 ). An organization administrator capable of adapting to the current circumstances is situational leadership.

Through a situational approach, followers advance and regress in a developmental continuum that measures the relative competence and commitment of the followers. Leaders must determine where followers are on the developmental continuum to adapt their leadership style accordingly (Northouse, 2021 ). Situational leadership is characterized by the relation between the task behavior (giving instructions, directing, guiding, and valuing) and the listening, supporting, and valuing aspects of the engagement. Combined strategies that consider individuals and the environment are advantageous for this style. Consequently, workers can maximize their learning experiences and satisfaction (Walls, 2019 ). In following a situational leader, it is not as necessary to have a charismatic leader with large numbers of followers as it is to have rational comprehension of the situation and appropriate response (Grint, 2011 ). Situational leadership requires individuals to be flexible and use their behavior according to their situation without following a set formula (Walls, 2019 ).

Work Motivation

Motivation determines what individuals do and how they do it based on what they are motivated to do (Meyer et al., 2004 ). Motivating someone to act to achieve his or her goals is a condition or circumstance that encourages and stimulates a person. As a result of solid motivation, an individual may possess energy, power, or a complex condition and the ability to move toward a particular goal, whether or not it is achieved. The motivation will be driven by both the individual (intrinsic) and his surroundings (extrinsic). According to Herzberg's theory, a motivational factor would be achievement, recognition, responsibility, progress, the work itself, and the opportunity to develop. Work motivation factors include achievement, recognition, and advancement (Syaifuddin and Sidu, 2019 ).

Job Satisfaction

The sense of comfort and pride employees experience in doing their jobs is called job satisfaction; job satisfaction is achieved by employees who feel their job is valuable and essential (Mustofa and Muafi, 2021 ). The belief in the amount of pay employees must get for the differences in rewards becomes a general attitude toward their work assessment (Castle et al., 2007 ). Besides, job satisfaction is related to what they get and expect (Dartey-Baah and Ampofo, 2016 ). Then, it will be represented by positive or negative behavior that employees showed in the workplace (Adiguzel et al., 2020 ). Several factors have influenced job satisfaction, including working hours, working conditions, payment, work design, promotions, demographic features, human resource development, leadership style, and stress level (Bhardwaj et al., 2021 ). There is a direct correlation between job satisfaction and an organization's leadership style that provides advice, praise, and assistance to employees when they face problems at work (Sapada et al., 2017 ; Phuc et al., 2021 ). Employees who are highly satisfied with their job can contribute to the organization's performance (Takdir et al., 2020 ). Employees often focus less on the duties and responsibilities of an employee than on perceived job satisfaction that encourages them to perform at their best (Aprilda et al., 2019 ).

Relationship of Situational Leadership With Work Motivation and Job Satisfaction

There is a positive correlation between work motivation and job satisfaction, and intrinsic motivation is positively correlated with job satisfaction (Alnlaclk and Alnlaclk, 2012 ). In research, it was discovered that intrinsic motivation was positively related to job satisfaction (Arasli et al., 2014 ).

Leadership and work motivation provide a positive and significant effect on job satisfaction (Pancasila et al., 2020 ). Leadership motivates and satisfies followers by helping them in a friendly way (Haq et al., 2022 ). According to several studies, situational leadership leads to increased motivation (Fikri et al., 2021 ). Situational leadership can positively and significantly affect job satisfaction and trust, respect, and pride among subordinates. Incorporating these characteristics can assist leaders in building employee commitment, raising risk awareness, articulating a shared vision, and reinforcing the importance of the vision (Al-edenat, 2018 ). The result is also in line with that of Li and Yuan ( 2017 ), who demonstrated that a leader's impact on job satisfaction is both positive and significant. According to Saleem ( 2015 ), leadership creates a significant positive impact on job satisfaction. Situational leadership is positively associated with job satisfaction (Fonda, 2015 ). In conclusion, leadership is crucial in determining work motivation and job satisfaction (Mustofa and Muafi, 2021 ).

Summary and Conclusions

Situational leadership has a positive influence on work motivation and job satisfaction ( Figure 1 ). It encourages employees to finish their jobs enthusiastically and spurs their devotion to their roles for successful job completion. This leadership style is easy to comprehend, intuitively sensible, and adaptable to various situations (Northouse, 2021 ).

Conceptual model.

Situational leadership significantly impacts job satisfaction (Shyji and Santhiyavalli, 2014 ). Assuring employee job satisfaction is a vital role of a leader in achieving organizational goals. Job satisfaction levels may vary between employees, places, jobs, and organizations (Ridlwan et al., 2021 ; Saleem et al., 2021 ). In addition to promoting exemplary employees, effective leadership promotes job satisfaction (Setyorini et al., 2018 ). Employee job satisfaction directly impacts job performance in an organization (Hutabarat, 2015 ). Employee performance is positively correlated with job satisfaction (Sidabutar et al., 2020 ). This situational approach has a prescriptive component, whereas many leadership theories are descriptive. Situational leadership, for instance, prescribes a directing style for you, the leader, if your followers are of very low competence. The situational approach suggests that you follow a supportive leadership style if your followers appear competent but lack confidence. These prescriptions, in general, provide all leaders with a set of guidelines that are extremely helpful for aiding and enhancing effective and efficient leadership (Northouse, 2021 ).

Leaders should be aware of how they lead and use appropriate styles to develop the skills of their staff while promoting satisfaction with their jobs (Carlos do Rego Furtado et al., 2011 ).

In sum, situational leadership motivates employees and improves employee satisfaction at work (Schweikle, 2014 ). The situational approach applies to virtually any organization and at nearly any level for almost any goal. There are many possible applications for it (Northouse, 2021 ). Higher productivity resulted from better leadership. In this way, job satisfaction contributes to employee performance ultimately. That means the higher job satisfaction leads to the better the employee performance (Jalagat, 2016 ). Effective leadership can result in more satisfied employees, more motivation at work, and more satisfaction with the workplace. It is worth mentioning that the theoretical understandings gained through this research will encourage future scholars to investigate how situational leaders can improve the performance of employees. An extensive empirical study is needed to understand the role of the situational leadership approach in the current pandemic circumstances. Moreover, the biggest challenge facing leadership studies right now is the lack of knowledge about the topic.

Author Contributions

SA presented the main idea and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AS contributed to revising and proofreading the manuscript. After review, TK and KP helped us finalize the revisions and proofreading. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Adiguzel Z., Ozcinar M. F., Karadal H. (2020). Does servant leadership moderate the link between strategic human resource management on rule breaking and job satisfaction? Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 26 , 103–110. 10.1016/j.iedeen.2020.04.002 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Al-edenat M. (2018). Reinforcing innovation through transformational leadership: mediating role of job satisfaction . J. Org. Change Manag. 31 , 810–838. 10.1108/JOCM-05-2017-0181 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alnlaclk U., Alnlaclk E. (2012). Relationships between career motivation, affective commitment and job satisfiaction . Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 58 , 355–362. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.1011 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aprilda R. S., Purwandari D. A., Syah T. Y. R. (2019). Servant leadership, organization commitment and job satisfaction on organizational citizenship behaviour . J. Multidiscip. Acad. 3 , 57–64. Available online at: http://www.kemalapublisher.com/index.php/JoMA/article/view/388/386 [ Google Scholar ]

- Arasli H., Daşkin M., Saydam S. (2014). Polychronicity and intrinsic motivation as dispositional determinants on hotel frontline employees' job satisfaction: do control variables make a difference? Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 109 , 1395–1405. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.643 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aslam S., Akram H., Saleem A., Zhang B. (2021). Experiences of international medical students enrolled in Chinese medical institutions towards online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic . PeerJ. 9 , e12061. 10.7717/peerj.12061 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bhardwaj A., Mishra S., Jain T. K. (2021). An analysis to understanding the job satisfaction of employees in banking industry . Mater. Today Proc. 37 , 170–174. 10.1016/j.matpr.2020.04.783 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Blau P. M. (1964). Justice in social exchange . Sociol. Inq. 34 , 193–206. 10.1111/j.1475-682X.1964.tb00583.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carlos do Rego Furtado L., da Graça Câmara Batista M., José Ferreira Silva F. (2011). Leadership and job satisfaction among Azorean hospital nurses: an application of the situational leadership model . J. Nurs. Manag. 19 , 1047–1057. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01281.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Castle N. G., Engberg J., Anderson R. A. (2007). Job satisfaction of nursing home administrators and turnover . Med. Care Res. Rev. 64 , 191–211. 10.1177/1077558706298291 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cropanzano R., Mitchell M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: an interdisciplinary review . J. Manag. 31 , 874–900. 10.1177/0149206305279602 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dartey-Baah K., Ampofo E. (2016). “Carrot and stick” leadership style: Can it predict employees' job satisfaction in a contemporary business organization? Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 7 , 328–345. 10.1108/AJEMS-04-2014-0029 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fikri M. A. A., Amri L. H. A., Nadeak M., Novitasari D., Asbari M. (2021). Urgensi menumbuhkan motivasi pelayanan publik pegawai puskesmas: analisis servant leadership dan mediasi basic need satisfaction . Edukatif: Jurnal Ilmu Pendidikan 3 , 4172–4185. 10.31004/edukatif.v3i6.1421 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fonda B. (2015). Pengaruh Gaya Kepemimpinan Situasional terhadap Budaya Organisasi dan Kepuasan Kerja Karyawan . Jurnal Administrasi Bisnis (JAB) 25 , 1–8. Available online at: https://media.neliti.com/media/publications/86100-ID-pengaruh-gaya-kepemimpinan-situasional-t.pdf [ Google Scholar ]

- Francisco C. D., Nuqui A. V. (2020). Emergence of a situational leadership during COVID-19 pandemic called new normal leadership . Int. J. Acad. Multidiscip. Res. 4 , 15–19. Available online at: http://ijeais.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/IJAMR201005.pdf [ Google Scholar ]

- Gouldner A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: a preliminary statement . Am. Soc. Rev. 161–178. 10.2307/2092623 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Grint K. (2011). “A history of leadership,” in The SAGE Handbook of Leadership , eds A. Bryman, D. Collinson, K. Grint, B. Jackson, and M. Uhl-Bien (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; ), 3–14. [ Google Scholar ]

- Haq S., Asbari M., Novitasari D., Abadiyah S. (2022). The homeschooling head performance: how the role of transformational leadership, motivation, and self-efficacy? Int. J. Soc. Manag. Stud. 3 , 167–179. 10.5555/ijosmas.v3i1.96 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hinojosa A. S., Shaine M. J. D., McCauley K. D. (2020). A strange situation indeed: Fostering leader–follower attachment security during unprecedented crisis . Manag. Dec. 58 , 2099–2115. 10.1108/MD-08-2020-1142 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Honore R. L., Robinson J. (2012). Leadership in the New Normal: A Short Course . Louisiana: Acadian House Pub. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hourston R. (2013). Spotlight on leadership styles. Leadership Development How to Develop Leadership Skills The Institute of Leadership & Mgt . Available online at: https://www.institutelm.com/learning/leadership-framework/authenticity/self-awareness/spotlight-on-leadership-styles.html

- Hutabarat W. (2015). Investigation of teacher job-performance model: Organizational culture, work motivation and job-satisfaction . J. Asian Soc. Sci. 11 , 295–304. 10.5539/ass.v11n18p295 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jalagat R. (2016). Job performance, job satisfaction, and motivation: a critical review of their relationship . Int. J. Adv. Manag. Econ. 5 , 36–42. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kirby S. (2020). 5 ways COVID-19 has changed workforce management . World Economic Forum . Available online at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/06/covid-homeworking-symptom-of-changing-face-of-workforce-management/ (accessed April 29, 2022).

- Li J., Yuan B. (2017). Both angel and devil: the suppressing effect of transformational leadership on proactive employee's career satisfaction . Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 65 , 59–70. 10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.06.008 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liborius P. (2014). Who is worthy of being followed? The impact of leaders' character and the moderating role of followers' personality . J. Psychol. 148 , 347–385. 10.1080/00223980.2013.801335 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Meyer J. P., Becker T. E., Vandenberghe C. (2004). Employee commitment and motivation: a conceptual analysis and integrative model . J. Appl. Psychol. 89 , 991. 10.1037/0021-9010.89.6.991 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mollenkopf D., Gaskill M., Nelson R., Diaz C. (2020). Navigating a “new normal” during the COVID-19 pandemic: college student perspectives of the shift to remote learning . Revue internationale des technologies en pédagogie universitaire/Int. J. Technol. High. Educ. 17 , 67–79. 10.18162/ritpu-2020-v17n2-08 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mustofa A., Muafi M. (2021). The influence of situational leadership on employee performance mediated by job satisfaction and Islamic organizational citizenship behavior . Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 10 , 95–106. 10.20525/ijrbs.v10i1.1019 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ngoma M., Namono R., Nangoli S., Bashir H., Nakyeyune S. (2021). Towards fighting COVID-19: Can servant leadership behaviour enhance commitment of medical knowledge-workers . Contin. Resil. Rev. 3 , 49–63. 10.1108/CRR-05-2020-0018 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Northouse P. G. (2021). Leadership: Theory and Practice . California: Sage Publications. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pancasila I., Haryono S., Sulistyo B. A. (2020). Effects of work motivation and leadership toward work satisfaction and employee performance: evidence from Indonesia . J. Asian Finance Econ. Bus. 7 , 387–397. 10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no6.387 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Parveen K., Tran P. Q. B., Alghamdi A. A., Namaziandost E., Aslam S., Xiaowei T. (2022a). Identifying the Leadership Challenges of K-12 Public Schools During COVID-19 disruption: a systematic literature review . Front. Psychol. 13 , 875646. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.875646 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Parveen K., Tran P. Q. B., Kumar T., Shah A. H. (2022b). Impact of principal leadership styles on teacher job performance: An empirical investigation . Front. Educ . 7, 814159. 10.3389/feduc.2022.814159 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Phuc T. Q. B., Parveen K., Tran D. T. T., Nguyen D. T. A. (2021). The linkage between ethical leadership and lecturer job satisfaction at a private higher education institution in Vietnam . J. Soc. Sci. Adv. 2 , 39–50. 10.52223/JSSA21-020202-12 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ridlwan M., Purwandari D. A., Syah T. Y. R. (2021). The effect of situational leadership and organizational culture on employee performance through job satisfaction . Int. J. Multic. Multirelig. Underst. 8 , 73–87. 10.18415/ijmmu.v8i3.2378 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Saleem A., Aslam S., Yin H., Rao C. (2020). Principal leadership styles and teacher job performance: viewpoint of middle management . Sustainability 12 , 3390. 10.3390/su12083390 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Saleem A., Wu L., Aslam S., Zhang T. (2021). Spotlight on leadership path-goal theory silos in practice to improve and sustain job-oriented development: evidence from education sector . Sustainability 13 , 12324. 10.3390/su132112324 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Saleem H. (2015). The impact of leadership styles on job satisfaction and mediating role of perceived organizational politics . Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 172 , 563–569. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.403 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schweikle N. (2014). Situational leadership: How to effectively lead and motivate employees through each development stage (Master's thesis). Degree Program in Business Management, Centria University of Applied Sciences, Kokkola, Finland . Available online at: https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/82414/schweikle_nataly.pdf?%20sequence=1%3E

- Setyorini R. W., Yuesti A., Landra N. (2018). The effect of situational leadership style and compensation to employee performance with job satisfaction as intervening variable at PT Bank Rakyat Indonesia (Persero), Tbk Denpasar Branch . Int. J. Contemp. Res. Rev. 9 , 20974–20985. 10.15520/ijcrr/2018/9/08/570 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shyji P. D., Santhiyavalli G. (2014). Impact of leadership styles on job satisfaction in higher education institutions . Int. J. Leadersh. 2, 29. Available online at: http://ijeais.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/IJAMR201005.pdf

- Sidabutar E., Syah T. Y. R., Anindita R. (2020). The impact of compensation, motivation, and job satisfaction on employee performance . J. Multidiscip. Acad. 4 , 1–5. [ Google Scholar ]

- Singh P., Mishra S. (2020). Ensuring employee safety and happiness in times of COVID-19 crisis . SGVU Int. J. Econ. Manag. 8. [ Google Scholar ]

- Spada A. F., Modding H. B., Gani A., Nujum S. (2017). The effect of organizational culture and work ethics on job satisfaction and employees performance . Int. J. Engg. Sci . 6 , 28–36. 10.31227/osf.io/gcep4 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Syaifuddin D. T., Sidu D. (2019). Effects of situational leadership, work motivation and cohesiveness on work satisfaction and employment performance . Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 10 , 7. [ Google Scholar ]

- Takdir S., Syah T. Y. R., Anindita R. (2020). Cultural intelligence effect on job satisfaction over employee performance . J. Multidiscip. Acad. 4 , 28–33. [ Google Scholar ]

- Usman M., Ghani U., Cheng J., Farid T., Iqbal S. (2021). Does participative leadership matters in employees' outcomes during COVID-19? Role of leader behavioral integrity . Front. Psychol. 12 , 1585. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646442 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Walls E. (2019). The value of situational leadership . Community Pract. 92 , 31–33. Available online at: https://www.communitypractitioner.co.uk/features/2019/03/value-situational-leadership [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang B., Liu Y., Qian J., Parker S. K. (2021). Achieving effective remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic: a work design perspective . Appl. Psychol. 70 , 16–59. 10.1111/apps.12290 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wu C. H., Parker S. K. (2017). The role of leader support in facilitating proactive work behavior: a perspective from attachment theory . J. Manag. 43 , 1025–1049. 10.1177/0149206314544745 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Applying the Situational Leadership ® framework to the whole person through conversations.

Build leadership competencies to overcome critical business challenges

Modern learning that teaches participants the Performance Ownership Process TM

A modern learning experience that teaches managers the Situational Leadership ® Model

At The Center for Leadership Studies, we are committed to helping you transform potential into meaningful action for your organization.

For more than 50 years, The Center for Leadership Studies (CLS) has been at the forefront of leadership training and organizational development. CLS is the global home of the original Situational Leadership ® Model —the most successful and widely adopted leadership training model available. Grounded in research and application, our award-winning solutions enable leaders to engage in effective performance conversations that build trust, increase productivity and drive behavior change.

Around the Globe

Fortune 500 Companies

Managers Trained

Grounded in Behavioral Science

Situational Leadership ® is a Timeless, Repeatable Framework for Effective Influence