Sample Header Text

Case studies for the treatment of autism spectrum disorder.

Ideal for preparing SLPs and other clinicians to make sound decisions, this casebook gives readers in-depth, real world demonstrations of today’s evidence-based interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Developed as a companion to the Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder textbook—but equally useful as a standalone casebook—this resource offers 14 realistic case studies that walk readers through common clinical challenges and help them hone their planning and problem-solving skills.

- Product Details

- Table of Contents

- Contributors

- A complete profile of the child’s strengths and needs , with a special focus on communication and social skills

- An overview of assessment practices that inform communication treatment planning

- A discussion of the clinical problem-solving processes used to identify treatment goals and strategies

- An intervention plan used to achieve the child’s goals, with details on implementation and modifications

- A report on the child’s outcomes

- A set of learning activities to help readers apply their knowledge

A one-of-a-kind practical resource developed by clinical experts, this casebook will help both current and future professionals understand today’s widely used autism interventions—and prepare to implement them effectively in their own practice.

GET THE BUNDLE: Buy this casebook as a bundle with its companion textbook, Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder, Second Edition . The new edition of this essential text gives SLPs the foundation they need to evaluate, select, and implement 14 of today’s widely used interventions.

- SLPPD 623 Communication Disorders in Autism

- SLHS 519 Language and Communicationin Austism Spectrum Disorders

- CSD 4900 Autism Spectrum Disorders

- 6230 Assessment & Intervention for Autism

You also may be interested in

You may also be interested in, brookes publishing.

- Screening & Assessments

- Resource Library

- Customer Support

- Permissions

- Newsletters

- Download Hub

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Autism Spectrum Disorder: A case study of Mikey

This paper describes Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) including diagnostic criteria, suspected causes, prevalence, comorbidities, and influences on client factors. A hypothetical case study is presented to give readers an illustration of what someone with ASD might look like. Possible treatment based on evidence and selected frame of references will be given for the hypothetical client. This paper is not all inclusive of the role of occupational therapy in the treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder, but gives an illustrative example.

Related Papers

Jennelyn Pondang

Autism Spectrum Disorder - Recent Advances

IOSR Journals

This article aims to observe all the manifestations of the behavior of a child with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), which shows deficits mainly in the communication sector. Also, the child shows repetitive and stereotypical behaviors throughout the lesson (Stasinos, 2016). Initially the paper describes the methodology followed. It then describes the child's cognitive profile and the deficits he presents. He then analyzes the intervention that was applied in order to improve the difficulties he faces and to further strengthen the skills he has already acquired. Finally, the paper presents the main conclusions as they emerged from the intervention.

Function and Disability Journal

Seyed Hassan Saneii

Melissa Vandiver Phelan

American Journal of Occupational Therapy

Renee Watling

Occupational therapy has much to offer to families of people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). However, people outside the profession may be unaware of occupational therapy’s breadth and scope. It is our responsibility and our duty to express the full range of occupational therapy services through research, clinical practice, advocacy, and consumer education. This special issue of the American Journal of Occupational Therapy, with its focus on autism, embarks on this endeavor by highlighting research and theoretical articles that address the various aspects of occupational therapy practice that can help to fully meet the needs of people with ASD and their families.

IP International Journal of Medical Paediatrics and Oncology

Autism spectrum disorder encompasses a wide range of neurodevelopment disabilities which affect children and their families across all sections of the society both in rural and urban settings. The prevalence of autism is rising irrespective of the socioeconomic background of the children. Hence every health worker has to be aware of ways to suspect and diagnose this condition and decide the appropriate treatment. Earliest intervention in autism spectrum disorder gives better results due to neuroplasticity. This article is targeted to help Medical officers, auxiliary nurse midwifes, anganwadi workers and other peripheral health workers by providing information on basics of ASD, normal speech development, simple ways for diagnosis and treatment for the same.

The American Journal of Occupational Therapy

Objective. The purpose of this study was to examine the current practice patterns of occupational therapists experienced in working with children with autism spectrum disorders. Method. Occupational therapists experienced in providing services to 2-year-old to 12-year-old children with autism completed a mail questionnaire describing practice patterns, theoretical approaches, intervention techniques, and preferred methods of preparation for work with children with autism. Results. Of those contacted, 72 occupational therapists met the study criteria and returned completed questionnaires. Practice patterns included frequent collaboration with other professionals during assessment and intervention. Intervention services were typically provided in a one-to-one format with the most common techniques being sensory integration (99%) and positive reinforcement (93%). Theoretical approaches included sensory integration (99%), developmental (88%), and behavioral (73%). Evaluations relied hea...

The American journal of occupational therapy : official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association

Kristie P Koenig

Evidence Connection articles provide a clinical application of systematic reviews developed in conjunction with the American Occupational Therapy Association's (AOTA's) Evidence-Based Practice Project. In this Evidence Connection article, we describe a case report of an adolescent with autism spectrum disorder. The occupational therapy assessment and treatment processes for school, home, community, and transition settings are described. Findings from the systematic reviews on this topic were published in the September/October 2015 issue of the American Journal of Occupational Therapy and in AOTA's Occupational Therapy Practice Guidelines for Individuals With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Each article in this series summarizes the evidence from the published reviews on a given topic and presents an application of the evidence to a related clinical case. Evidence Connection articles illustrate how the research evidence from the reviews can be used to inform and guide clinical ...

Javiera Poblete

Autism spectrum disorder is a term used to describe a constellation of early-appearing social communication deficits and repetitive sensory-motor behaviours associated with a strong genetic component as well as other causes. The outlook for many individuals with autism spectrum disorder today is brighter than it was 50 years ago; more people with the condition are able to speak, read, and live in the community rather than in institutions, and some will be largely free from symptoms of the disorder by adulthood. Nevertheless, most individuals will not work full-time or live independently. Genetics and neuroscience have identified intriguing patterns of risk, but without much practical benefit yet. Considerable work is still needed to understand how and when behavioural and medical treatments can be effective, and for which children, including those with substantial comorbidities. It is also important to implement what we already know and develop services for adults with autism spectrum disorder. Clinicians can make a difference by providing timely and individualised help to families navigating referrals and access to community support systems, by providing accurate information despite often unfiltered media input, and by anticipating transitions such as family changes and school entry and leaving.

RELATED PAPERS

AJS Review, 37 (2013), pp כט-נג.

Maoz Kahana

Revista Catarinense de Economia

Lauro Mattei

Community College Journal of Research and Practice

Victor Saenz

calvin mehl

The European Physical Journal C

Gustavo Martinez

French-Ukrainian Journal of Chemistry

Andrii Shevchenko

Adrián Pótári

vicente merchan

Analytica Chimica Acta

Forough Ghasemi

The Applied Computational Electromagnetics Society Journal (ACES)

Ahmed Attiya

滑铁卢大学毕业证文凭 购买加拿大Waterloo文凭学历

Diletta Guidi

Asti Jupita Sari

The Pan African Medical Journal

Helen Akhiwu

Michel Debacker

Annals of medical research

Servet Karagul

ajibola arewa

Translational Andrology and Urology

Laureano Rangel

Proceedings of the ITI 2012 34th International Conference on INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY INTERFACES

Joseph Valacich

Health Science Journal of Indonesia

Carmen siagian

Cirugía y Cirujanos

Omar Espinosa González

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Advertisement

Reading Comprehension and Autism Spectrum Disorder: a Systematic Review of Interventions Involving Single-Case Experimental Designs

- Original Article

- Published: 03 April 2020

- Volume 8 , pages 3–21, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Binita D. Singh 1 ,

- Dennis W. Moore 1 ,

- Brett E. Furlonger 1 ,

- Angelika Anderson 2 ,

- Rebecca Fall 3 &

- Sarah Howorth 4

2785 Accesses

12 Citations

Explore all metrics

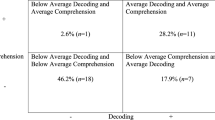

Research was reviewed that focussed on the reading comprehension abilities of students with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD). Although single-case experimental design (SCD) is an accepted and widely used way in which to evaluate an evidence-based practice, very few studies met the What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) standards for evidence-based SCD research. These studies were then grouped into six non-exclusionary intervention categories (a) visually-cued instruction, (b) collaborative strategies, (c) metacognitive strategy instruction, (d) technology-assisted instruction, (e) adapted text, and (f) behavioural strategies. Effect size calculations indicated that visually-cued instruction, metacognitive strategy instruction, and adapted text were highly effective, while collaborative strategies and technology-assisted instruction were moderately effective. While effective interventions were identified, the need for replications that met WWC standards was noted.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

A Synthesis of Reading Comprehension Interventions and Measures for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Intensive Support Needs

Reading Instruction for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Comparing Observations of Instruction to Student Reading Profiles

Technology Impact on Reading and writing skills of children with autism: a systematic literature review

Accardo, A. L. (2015). Research synthesis: Effective practices for improving the reading comprehension of students with autism spectrum disorder. DADD Online Journal, 2 (1), 7–20. Retrieved from https://rdw.rowan.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1005&context=education_facpub .

Alison, C., Root, J. R., Browder, D. M., & Wood, L. (2017). Technology-based shared story reading for students with autism who are English-language learners. Journal of Special Education Technology, 32 (2), 91–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162643417690606 .

Article Google Scholar

Allison, D. B., & Gorman, B. S. (1993). Calculating effect sizes for meta-analysis: The case of the single case. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 31 (6), 621–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(93)90115-b .

Atherton, G., Lummis, B., Day, S. X., & Cross, L. (2018). What am I thinking? Perspective-taking from the perspective of adolescents with autism. Autism, 23 (5), 1186–1200. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318793409 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Atkinson, L., Slade, L., Powell, D., & Levy, J. P. (2017). Theory of mind in emerging reading comprehension: A longitudinal study of early indirect and direct effects. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 164 , 225–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2017.04.007 .

Barlow, D. H., Nock, M., & Hersen, M. (2009). Single case experimental designs: Strategies for studying behavior for change (3rd ed.). Boston: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon.

Baron-Cohen, S., Leslie, A. M., & Frith, U. (1985). Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind”? Cognition, 21 (1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(85)90022-8 .

Bethune, K. S., & Wood, C. L. (2013). Effects of wh-question graphic organizers on reading comprehension skills of students with autism spectrum disorders. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 48 (2), 236–244. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/23880642 .

Boetsch, E. A., Green, P. A., & Pennington, B. F. (1996). Psychosocial correlates of dyslexia across the life span. Development and Psychopathology, 8 (3), 539–562. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579400007264 .

Bos, C. S., & Vaughn, S. (2002). Strategies for teaching students with learning and behaviour problems . Boston: Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.

Google Scholar

Brossart, D. F., Laird, V. C., & Armstrong, T. W. (2018). Interpreting Kendall’s Tau and Tau- U for single-case experimental designs. Cogent Psychology, 5 (1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2018.1518687 .

Busacca, M., Anderson, A., & Moore, D. W. (2015). Self-management for primary school students demonstrating problem behavior in regular classrooms: Evidence review of single-case design research. Journal of Behavioral Education, 24 (4), 373–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-015-9230-3 .

Cain, K., Oakhill, J., & Bryant, P. (2004a). Children’s reading comprehension ability: Concurrent prediction by working memory, verbal ability, and component skills. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96 (1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.1.31 .

Cain, K., Oakhill, J., & Lemmon, K. (2004b). Individual differences in the inference of word meanings from context: The influence of reading comprehension, vocabulary knowledge, and memory capacity. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96 (4), 671–681. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.4.671 .

Cakiroglu, O. (2012). Single subject research: Applications to special education. British Journal of Special Education, 39 (1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8578.2012.00530.x .

Carnahan, C., Musti-Rao, S., & Bailey, J. (2009). Promoting active engagement in small group learning experiences for students with autism and significant learning needs. Education and Treatment of Children, 32 (1), 37–61. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.0.0047 .

Carnahan, C. R., & Williamson, P. S. (2013). Does compare-contrast text structure help students with autism spectrum disorder comprehend science text ? Exceptional Children, 79 (3), 347–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291307900302 .

Carnahan, C. R., Williamson, P., Birri, N., Swoboda, C., & Snyder, K. K. (2016). Increasing comprehension of expository science text for students with autism spectrum disorder. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 31 (3), 208–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357615610539 .

Carnahan, C. R., Williamson, P. S., & Christman, J. (2011). Linking cognition and literacy in students with autism spectrum disorder. Teaching Exceptional Children, 43 (6), 54–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/004005991104300606 .

Catts, H. W., Adlof, S. M., & Weismer, S. E. (2006). Language deficits in poor comprehenders: A case for the simple view of reading. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49 (2), 278–293. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2006/023) .

Cawley, J. F., Kahn, H., & Tedesco, A. (1989). Vocational education and students with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 22 (10), 630–634. https://doi.org/10.1177/002221948902201008 .

Chiang, H.-M., & Lin, Y.-H. (2007). Reading comprehension instruction for students with autism spectrum disorders: A review of the literature. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 22 (4), 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/10883576070220040801 .

Colle, L., Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., & van der Lely, H. K. J. (2008). Narrative discourse in adults with high-functioning autism or Asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38 (1), 28–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0357-5 .

Cook, B. G., Tankersley, M., & Landrum, T. J. (2013). Evidence-based practices in learning and behavioral disabilities: The search for effective instruction. In B. G. Cook, M. Tankersley, & T. J. Landrum (Eds.), Advances in learning and behavioral disabilities . Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2007). Applied behavior analysis (2nd ed.). New Jersey: Pearson Merrill Prentice Hall.

Council for Exceptional Children: Standards for evidence-based practices in special education. (2014). Teaching Exceptional Children, 46 (6), 206–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0040059914531389 .

Cutting, L. E., & Scarborough, H. S. (2006). Prediction of reading comprehension: Relative contributions of word recognition, language proficiency, and other cognitive skills can depend on how comprehension is measured. Scientific Studies of Reading, 10 (3), 277–299. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532799xssr1003_5 .

Dib, N., & Sturmey, P. (2012). Behavioral skills training and skill learning. In N. M. Seel (Ed.), Encyclopaedia of the sciences of learning (pp. 437–438). Boston: Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Diehl, J. J., Bennetto, L., & Young, E. C. (2006). Story recall and narrative coherence of high-functioning children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34 (1), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-005-9003-x .

Dole, J. A., Nokes, J. D., & Drits, D. (2009). Cognitive strategy instruction. In G. G. Duffy & S. E. Israel (Eds.), Handbook of research on reading comprehension (pp. 347–372). New York: Routledge.

Dyson, L. (2015). The literacy competence of children with autism spectrum syndrome: A systematic review of three decades of research. International Journal of Literacies, 21 (3-4), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.18848/2327-0136/cgp/v21i3-4/48836 .

El Zein, F., Gevarter, C., Bryant, B., Son, S. H., Bryant, D., Kim, M., & Solis, M. (2016). A comparison between iPad-assisted and teacher-directed reading instruction for students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 28 (2), 195–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-015-9458-9 .

El Zein, F., Solis, M., Vaughn, S., & McCulley, L. (2014). Reading comprehension interventions for students with autism spectrum disorders: A synthesis of research. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 44 (6), 1303–1322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1989-2 .

Finnegan, E., & Mazin, A. L. (2016). Strategies for increasing reading comprehension skills in students with autism spectrum disorder: A review of the literature. Education and Treatment of Children, 39 (2), 187–219. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2016.0007 .

Flores, M. M., & Ganz, J. B. (2007). Effectiveness of direct instruction for teaching statement inference, use of facts, and analogies to students with developmental disabilities and reading delays. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 22 (4), 244–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/10883576070220040601 .

Flores, M., Musgrove, K., Renner, S., Hinton, V., Strozier, S., Franklin, S., & Hil, D. (2012). A comparison of communication using the apple iPad and a picture-based system. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 28 (2), 74–84. https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2011.644579 .

Frith, U., & Snowling, M. (1983). Reading for meaning and reading for sound in autistic and dyslexic children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 1 (4), 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-835X.1983.tb00906.x .

Furlonger, B., Holmes, V. M., & Rickards, F. W. (2014). Phonological awareness and reading proficiency in adults with profound deafness. Reading Psychology, 35 (4), 357–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2012.726944 .

Gajria, M., Jitendra, A. K., Sood, S., & Sacks, G. (2007). Improving comprehension of expository text in students with LD: A research synthesis. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 40 (3), 210–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222194070400030301 .

Gast, D. L. (2010). Single subject research methodology in behavioral sciences . New York: Routledge.

Gast, D., Lloyd, B., & Ledford, J. (2014). Multiple baseline and multiple probe designs. In D. Gast & J. Ledford (Eds.), Single case research methodology: Applications in special education and behavioral science . New York: Routledge.

Gately, S. E. (2008). Facilitating reading comprehension for students on the autism spectrum. Teaching Exceptional Children, 40 (3), 40–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/004005990804000304 .

Gersten, R., Fuchs, L. S., Williams, J. P., & Baker, S. (2001). Teaching reading comprehension strategies to students with learning disabilities: A review of research. Review of Educational Research, 71 (2), 279–320. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543071002279 .

Goodman, G., & Williams, C. M. (2007). Interventions for increasing the academic engagement of students with autism spectrum disorders in inclusive classrooms. Teaching Exceptional Children, 39 (6), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/004005990703900608 .

Gough, P. B., & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7 (1), 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193258600700104 .

Happé, F. (1995). The role of age and verbal ability in the theory of mind task performance of subjects with autism. Child Development, 66 (3), 843. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131954 .

Happé, F., & Frith, U. (2006). The weak coherence account: detail-focused cognitive style in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36 (1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-005-0039-0 .

Heflin, L. J., & Alberto, P. A. (2001). Establishing a behavioural context for learning for students with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 16 (2), 93–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/108835760101600205 .

Higgins, K., & Boone, R. (1996). Creating individualized computer-assisted instruction for students with autism using multimedia authoring software. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 11 (2), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/108835769601100202 .

Hoover, W. A., & Gough, P. B. (1990). The simple view of reading. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 2 , 127–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00401799 .

Horner, R. H., Carr, E. G., Halle, J., McGee, G., Odom, S., & Wolery, M. (2005). The use of single-subject research to identify evidence-based practice in special education. Exceptional Children, 71 (2), 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290507100203 .

Howorth, S., Lopata, C., Thomeer, M., & Rodgers, J. (2016). Effects of the TWA strategy on expository reading comprehension of students with autism. British Journal of Special Education, 43 (1), 39–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12122 .

Huemer, S. V., & Mann, V. (2010). A comprehensive profile of decoding and comprehension in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40 (4), 485–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0892-3 .

Jitendra, A. K., Burgess, C., & Gajria, M. (2011). Cognitive strategy instruction for improving expository text comprehension of students with learning disabilities: the quality of evidence. Exceptional Children, 77 (2), 135–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291107700201 .

Johnson, D., & Johnson, R. (2002). Learning together and alone: overview and meta-analysis. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 22 (1), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/0218879020220110 .

Kagohara, D., van der Meer, L., Ramdoss, S., O’Reilly, M. F., Lancioni, G. E., Davis, T. N., & Sigafoos, J. (2013). Using iPods and iPads in teaching programs for individuals with developmental disabilities: a systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34 (1), 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2012.07.027 .

Kamps, D. M., Barbetta, P. M., Leonard, B. R., & Delquadri, J. (1994). Classwide peer tutoring: an integration strategy to improve reading skills and promote peer interactions among students with autism and general education peers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27 (1), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1994.27-49 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kennedy, C. (2005). Single-case designs for educational research . Boston: Pearson/A & B.

Khowaja, K., & Salim, S. S. (2013). A systematic review of strategies and computer-based intervention (CBI) for reading comprehension of children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7 (9), 1111–1121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2013.05.009 .

Kim, A.-H., Vaughn, S., Wanzek, J., & Wei, S. (2004). Graphic organizers and their effects on the reading comprehension of students with LD. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 37 (2), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222194040370020201 .

Kimhi, Y. (2014). Theory of mind abilities and deficits in autism spectrum disorders. Topics in Language Disorders, 34 (4), 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1097/tld.0000000000000033 .

Knight, V., McKissick, B. R., & Saunders, A. (2013). A review of technology-based interventions to teach academic skills to students with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43 (11), 2628–2648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1814-y .

Knight, V. F., & Sartini, E. (2015). A comprehensive literature review of comprehension strategies in core content areas for students with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45 (5), 1213–1229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2280-x .

Loukusa, S., & Moilanen, I. (2009). Pragmatic inference abilities in individuals with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism: a review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3 (4), 890–904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2009.05.002 .

Loveland, K., & Tunali, B. (1993). Narrative language in autism and the theory of mind hypothesis: a wider perspective. In S. Baron-Cohen, H. Tager-Flusberg, & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Understanding other minds: Perspectives from autism (pp. 267–291). Oxford, London: Oxford University Press.

Ma, H. H. (2006). An alternative method for quantitative synthesis of single-subject researches: Percentage of data points exceeding the median. Behavior Modification, 30 (5), 598–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445504272974 .

Maggin, D. M., Briesch, A. M., Chafouleas, S. M., Ferguson, T. D., & Clark, C. (2013). A comparison of rubrics for identifying empirically supported practices with single-case research. Journal of Behavioral Education, 23 (2), 287–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-013-9187-z .

Manolov, R., Solanas, A., & Leiva, D. (2010). Comparing “visual” effect size indices for single-case designs. Methodology, 6 (2), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-2241/a000006 .

Mayton, M. R., Wheeler, J. J., Menendez, A. L., & Zhang, J. (2010). An analysis of evidence-based practices in the education and treatment of learners with autism spectrum disorders. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 45 (4), 539–551. Retrieved from http://daddcec.org/Portals/0/CEC/Autism_Disabilities/Research/Publications/Education_Training_Development_Disabilities/2010v45_Journals/ETDD_201012v45n4p539-551_Analysis_Evidence-Based_Practices_Education_Treatment_Learners.pdf .

McGee, G. G., Krantz, P. J., & McClannahan, L. E. (1986). An extension of incidental teaching procedures to reading instruction for autistic children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 19 (2), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1986.19-147 .

Mucchetti, C. A. (2013). Adapted shared reading at school for minimally verbal students with autism. Autism, 17 (3), 358–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361312470495 .

Nation, K., & Norbury, C. F. (2005). Why reading comprehension fails: Insights from developmental disorders. Topics in Language Disorders, 25 (1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/00011363-200501000-00004 .

Nation, K., & Snowling, M. (1997). Assessing reading difficulties: The validity and utility of current measures of reading skill. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 67 (3), 359–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1997.tb01250.x .

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Neely, L., Rispoli, M., Camargo, S., Davis, H., & Boles, M. (2013). The effect of instructional use of an iPad® on challenging behavior and academic engagement for two students with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7 (4), 509–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2012.12.004 .

Neuman, S. B., & McCormick, S. (1995). Single-subject experimental research: applications for literacy . Newark: International Reading Association.

Olive, M. L., & Franco, J. H. (2008). (Effect) size matters: And so does the calculation. The Behavior Analyst Today, 9 (1), 5–10. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0100642 .

Ozonoff, S., Pennington, B. F., & Rogers, S. J. (1991). Executive function deficits in high-functioning autistic individuals: Relationship to theory of mind. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 32 (7), 1081–1105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb00351.x .

Parker, R. I., & Hagan-Burke, S. (2007). Median-based overlap analysis for single case data: A second study. Behavior Modification, 31 (6), 919–936. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445507303452 .

Pellicano, E. (2012). The development of executive function in autism. Autism Research and Treatment, 2012 , 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/146132 .

Perner, J., Frith, U., Leslie, A. M., & Leekam, S. R. (1989). Exploration of the autistic child's theory of mind: Knowledge, belief, and communication. Child Development, 60 (3), 689–700. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130734 .

Plavnick, J. B., & Ferreri, S. J. (2013). Single-case experimental designs in educational research: A methodology for causal analyses in teaching and learning. Educational Psychology Review, 25 (4), 549–569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-013-9230-6 .

Randi, J., Newman, T., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2010). Teaching children with autism to read for meaning: Challenges and possibilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40 (7), 890–902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-0938-6 .

Reason, R., & Morfidi, E. (2001). Literacy difficulties and single-case experimental design. Educational Psychology in Practice, 17 (3), 227–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667360123833 .

Reichow, B., Volkmar, F. R., & Cicchetti, D. V. (2008). Development of the evaluative method for evaluating and determining evidence-based practices in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38 (7), 1311–1319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0517-7 .

Reutebuch, C. K., El Zein, F., Kim, M. K., Weinberg, A. N., & Vaughn, S. (2015). Investigating a reading comprehension intervention for high school students with autism spectrum disorder: A pilot study. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 9 , 96–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.10.002 .

Ricketts, J., Jones, C. R., Happé, F., & Charman, T. (2013). Reading comprehension in autism spectrum disorders: The role of oral language and social functioning. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43 (4), 807–816. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1619-4 .

Roberts, E. (2013). Autism and reading comprehension: Bridging theory, research and practice (doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (UMI no. 638917).

Roth, D. A., Muchnik, C., Shabtai, E., Hildesheimer, M., & Henkin, Y. (2012). Evidence for atypical auditory brainstem responses in young children with suspected autism spectrum disorders. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 54 (1), 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04149.x .

Rumsey, J. M. (1992). Neuropsychological studies of high-level autism. In E. Scholpler & G. B. Mesibov (Eds.), High-functioning individuals with autism (pp. 41–64). New York: Plenum.

Scheeren, A. M., de Rosnay, M., Koot, H. M., & Begeer, S. (2013). Rethinking theory of mind in high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54 (6), 628–635. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12007 .

Seethaler, P. M., & Fuchs, L. S. (2005). A drop in the bucket: randomized controlled trials testing reading and math interventions. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 20 (2), 98–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5826.2005.00125.x .

Senokossoff, G. W. (2016). Developing reading comprehension skills in high-functioning children with autism spectrum disorder: A review of the research, 1990-2012. Reading & Writing Quarterly: Overcoming Learning Difficulties, 32 (3), 223–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2014.936574 .

Singh, B. D., Moore, D. W., Furlonger, B. E., Anderson, A., Busacca, M. L., & English, D. L. (2017). Teaching reading comprehension skills to a child with autism using behaviour skills training. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47 (10), 3049–3058. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3229-7 .

Slavin, R. (1989). Cooperative learning and student achievement. In R. Slavin (Ed.), School and classroom organization (pp. 129–156). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Slavin, R. (2013). Effective programmes in reading and mathematics: Evidence from the best evidence Encyclopaedia. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 24 (4), 383–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2013.797913 .

Snyder, S. M., Knight, V. F., Ayres, K. M., Mims, P. J., & Sartini, E. C. (2017). Single-case design elements in text comprehension research for students with developmental disabilities. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 52 (4), 405–421. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1967051454/ .

Solis, M., El Zein, F., Vaughn, S., McCulley, L. V., & Falcomata, T. S. (2016). Reading comprehension interventions for students with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 31 (4), 284–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357615583464 .

Stringfield, S. G., Luscre, D., & Gast, D. L. (2011). Effects of a story map on accelerated reader postreading test scores in students with high-functioning autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 26 (4), 218–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357611423543 .

Tarlow, K. R. (2016). An improved rank correlation effect size statistic for single-case designs: Baseline corrected tau. Behavior Modification, 41 (4), 427–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445516676750 .

Taylor, B., Harris, L., & Pearson, P. D. (1988). Reading difficulties: instruction and assessment . New York: Random House.

Turner, H., Remington, A., & Hill, V. (2017). Developing an intervention to improve reading comprehension for children and young people with autism Spectrum disorders. Educational and Child Psychology, 34 (2). Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317175967_Developing_an_intervention_to_improve_reading_comprehension_for_children_and_young_people_with_autism_spectrum_disorders .

Van Dijk, T. A., & Kintsch, W. (1983). Strategies of discourse comprehension . New York: Academic Press.

Wahlberg, T., & Magliano, J. P. (2004). The ability of high function individuals with autism to comprehend written discourse. Discourse Processes, 38 (1), 119–144. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326950dp3801_5 .

Wendt, O., & Miller, B. (2012). Quality appraisal of single-subject experimental designs: An overview and comparison of different appraisal tools. Education and Treatment of Children, 35 (2), 235–268. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2012.0010 .

Whalon, K. J., Al Otaiba, S., & Delano, M. E. (2008). Evidence-based reading instruction for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24 (1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357608328515 .

Whalon, K., Hanline, M. F., & Davis, J. (2016). Parent implementation of RECALL: A systematic case study. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 51 (2), 211-220. Retrieved from http://daddcec.org/Portals/0/CEC/Autism_Disabilities/Research/Publications/Education_Training_Development_Disabilities/Full_Journals/ETADD51(2)_211_Whalon.pdf .

What Works Clearinghouse (WWC). (2014). Pilot single-case design standards. In What works clearinghouse procedures and standards handbook, Version 3.0 (pp. E.1–E.15). Retrieved from: https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/Docs/referenceresources/wwc_procedures_v3_0_standards_handbook.pdf .

Whitehouse, A. J. O., Granich, J., Alvares, G., Busacca, M., Cooper, M. N., Dass, A., et al. (2017). A randomised-controlled trial of an iPad-based application to complement early behavioural intervention in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58 (9), 1042–1052. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12752 .

Wilcox, R. R. (2010). Fundamentals of modern statistical methods: substantially improving power and accuracy . New York: Springer.

Book Google Scholar

Williamson, P., Carnahan, C. R., Birri, N., & Swoboda, C. (2015). Improving comprehension of narrative using character event maps for high school students with autism spectrum disorder. The Journal of Special Education, 49 (1), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466914521301 .

Wolery, M., Busick, M., Reichow, B., & Barton, E. E. (2010). Comparison of overlap methods for quantitatively synthesizing single-subject data. The Journal of Special Education, 44 (1), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466908328009 .

Download references

This research was supported in part by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship and a Monash International Tuition Scholarship (MITS).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Krongold Centre, Faculty of Education, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Binita D. Singh, Dennis W. Moore & Brett E. Furlonger

School of Psychology, The University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand

Angelika Anderson

Faculty of Health Sciences, Australian Catholic University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Rebecca Fall

School of Learning and Teaching, The University of Maine, Orono, ME, USA

Sarah Howorth

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

BS conducted the literature search, reviewed all articles, undertook data analysis, and drafted the manuscript; DM and BF conceived of the review, assisted with determining the inclusion criteria, reviewed articles meeting the inclusion criteria, and helped draft the manuscript; AA helped draft the manuscript; RF assisted in conducting the literature search and reviewing the articles; SH also helped draft the manuscript. All authors provided feedback on the manuscript drafts and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Binita D. Singh .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Singh, B.D., Moore, D.W., Furlonger, B.E. et al. Reading Comprehension and Autism Spectrum Disorder: a Systematic Review of Interventions Involving Single-Case Experimental Designs. Rev J Autism Dev Disord 8 , 3–21 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-020-00200-3

Download citation

Received : 01 April 2019

Accepted : 05 March 2020

Published : 03 April 2020

Issue Date : March 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-020-00200-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Reading comprehension

- Singe-case design

- What Works Clearinghouse

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- World J Psychiatry

- v.13(6); 2023 Jun 19

- PMC10294139

Pharmacotherapy in autism spectrum disorders, including promising older drugs warranting trials

Jessica hellings.

Department of Psychiatry, University of Missouri-Kansas City, Lee's Summit, MO 64063, United States. [email protected]

Corresponding author: Jessica Hellings, MB.BCh., MMed, Professor, Department of Psychiatry, University of Missouri-Kansas City, 300 SE Second St, Lee's Summit, MO 64063, United States. [email protected]

Available pharmacotherapies for autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are reviewed based on clinical and research experience, highlighting some older drugs with emerging evidence. Several medications show efficacy in ASD, though controlled studies in ASD are largely lacking. Only risperidone and aripiprazole have Federal Drug Administration approval in the United States. Methylphenidate (MPH) studies showed lower efficacy and tolerability for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) than in the typically developing (TD) population; atomoxetine demonstrated lower efficacy but comparable tolerability to TD outcomes. Guanfacine improved hyperactivity in ASD comparably to TD. Dex-troamphetamine promises greater efficacy than MPH in ASD. ADHD medications reduce impulsive aggression in youth, and may also be key for this in adults. Controlled trials of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors citalopram and fluoxetine demonstrated poor tolerability and lack of efficacy for repetitive behaviors. Trials of antiseizure medications in ASD remain inconclusive, however clinical trials may be warranted in severely disabled individuals showing bizarre behaviors. No identified drugs treat ASD core symptoms; oxytocin lacked efficacy. Amitriptyline and loxapine however, show promise. Loxapine at 5-10 mg daily resembled an atypical antipsychotic in positron emission tomography studies, but may be weight-sparing. Amitriptyline at approximately 1 mg/ kg/day used cautiously, shows efficacy for sleep, anxiety, impulsivity and ADHD, repetitive behaviors, and enuresis. Both drugs have promising neurotrophic properties.

Core Tip: Most prescribing in autism spectrum disorders (ASD) is off-label; only risperidone and aripiprazole are Federal Drug Administration-approved in ASD, for irritability. Atypical antipsychotics are associated with metabolic side effects. Loxapine at 5-10 mg/day resembled an atypical antipsychotic in positron emission tomography studies; preliminary studies and clinical experience in ASD suggest efficacy and a promising metabolic profile. Controlled attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medication trials in ASD youth include methylphenidate, atomoxetine and guanfacine. The author recommends dextroamphetamine as an important treatment option for ADHD in ASD. Amitriptyline often improves impulsive aggression, self-injury, sleep, anxiety and enuresis. This article recommends additional older drug trials in ASD: Detroamphetamine, amitriptyline, loxapine, and lamotrigine for likely seizures.

INTRODUCTION

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is diagnosed using criteria of significant deficits in social communication and interaction, together with at least two types of restricted and repetitive interests and behaviors (RRBs)[ 1 ]. ASD develops prenatally and during early childhood. There is no longer an age cut-off for diagnosis, though it is often evident by age 1-3 years. The prevalence of ASD has risen globally since 2000. Two separate United States studies using the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health reported ASD prevalence of 1 in 40 children[ 2 , 3 ]. After decades there is still no definitive medication treatment for the core features of autism likely due to the heterogeneity of ASD, including various genetic causes. Recent studies with negative findings for core symptoms include oxytocin, bumetanide and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) fluoxetine and citalopram for RRBs[ 4 ]. A meta-analysis confirmed there are still no treatments with efficacy for RRBs[ 5 ].

In addition to core ASD disabilities, the majority of these individuals have other serious challenges affecting them. Approximately 30%-50% also have intellectual disability (ID)[ 6 ]. Those more severely affected for example by birth injuries may have hydrocephalus and cerebral palsy, along with varying degrees of motor paralysis. Although there is a tendency worldwide to diagnose ASD in high-functioning, milder cases, an estimated quarter of individuals with ASD have less than 20 words of expressive language and are thus minimally verbal[ 7 ]. Approximately 20%-40% of those with ASD also have epilepsy, with greater rates in the more severely affected[ 8 ], which includes minimally verbal individuals.

In addition, psychiatric illness occurs several times more commonly in those with ASD than in the general population[ 9 , 10 ]. Common presenting problems include hyperactivity, impulsive aggression, property destruction and self-injury, which are not Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-fifth edition-Text Revised (DSM-5-TR) diagnoses. A study of 1380 youth with ASD found that over two thirds (68%) manifested aggression towards a caregiver, and almost half (49%) showed aggression towards non-caregivers[ 11 ]. Psychiatrist training in the field of developmental disabilities is seriously lacking in most universities worldwide, and has marginally improved in the United States in the past 5 years[ 12 , 13 ]. Individuals with ASD and their caregivers have great difficulty identifying a provider in their geographical area who will treat them. The field still suffers from a serious lack of clinical trials to guide treatment of psychiatric comorbidity. Those providers who treat such patients must rely on the few ASD clinical trials published, experience gained by different medication trials, and extrapolation from studies in typically developing (TD) individuals.

An analysis of 33565 children with ASD, found that 35% received 2 or more psychotropic medications, while 15% received 3 or more[ 14 ]. Polypharmacy especially with antipsychotics is even greater in adults, when many non-psychiatric medications are also prescribed apart from psychotropic medications[ 15 ]. The lack of evidence base results inevitably in exposure of these individuals to repeated medication trials, an unnecessary burden of side effects, and attrition from care[ 16 ]. Individuals with ASD often have one or more comorbid DSM-5-TR diagnoses. Working DSM-5-TR diagnoses are important guides for selecting classes of medications. Diagnostic symptoms of DSM-5-TR diagnoses may be more difficult to recognize in those more severely affected, including the minimally verbal. The Diagnostic Manual of Intellectual Disabilities-2 (DM-ID2)[ 17 ] is a useful crosswalk for applying DSM-5 criteria to individuals with intellectual and developmental disorders and/or ASD. Clearly the verbal criteria for diagnoses are not used in the minimally verbal.

Only risperidone and aripiprazole are Federal Drug Administration (FDA)-approved in the United States for individuals with ASD and irritability. The few other drugs prospectively studied in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in ASD include methylphenidate (MPH), atomoxetine (ATX), guanfacine, the SSRIs fluoxetine and citalopram, and valproic acid[ 18 ]. Metformin, arbaclofen, lovastatin, trifinetide, 5-hydroxytryptamine7 (5-HT7) agonist ligands, flavonoids, and the dietary supplement sulfurophane amongst others, are still being studied[ 4 ]. More RCTs are urgently needed for individuals with ASD/ID. While studies continue to test possible treatments for the core symptoms of ASD, even experts frequently run out of options for the many comorbidities, after many medication trials including clozapine have failed. It may also turn out that no one drug will target and treat the core symptoms in ASD, given the vast heterogeneity of genetic and other causes.

Behavior analysis and psychosocial treatments play a key role in any overall management plan, since problems due to environmental factors or maladaptive learning will not respond to medication treatments. This article highlights several available older medications, with decades of community use in the general population, that show promise in ASD. Emerging evidence about them includes preliminary observed efficacy, neurotrophic effects and apparent tolerability in low dose.

ATTENTION DEFICIT HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER: EXISTING STUDIES AND EMERGING EVIDENCE ON OTHER OLD MEDICATIONS

Symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) include inattention, distractibility, hyperactivity and impulsivity. ADHD in ASD is often associated with dangerous behaviors including impulsive aggression and self-injury[ 19 ]. Prior to DSM-5, ADHD was not recognized as a separate diagnosis for individuals with ASD. Since it does not manifest in all individuals with ASD but does so in a large proportion, notably 28%-68%[ 20 ] it is now included as a separate diagnosis. ADHD is increasingly identified and treated in adults with ASD; a recent study found high rates of ADHD in 63 tertiary-referred adults with ASD screened for psychiatric comorbidity, notably 68% for lifetime prevalence of ADHD[ 9 ]. Additionally, ADHD is less likely to improve after adolescence in youth with ASD than in the general population with ADHD. In the community, inattentive-type ADHD is the most common subtype found in ASD/ID, however it is often untreated.

The hyperactive-impulsive subtype of ADHD has poorer outcomes in individuals with ASD, related to the more disruptive nature of hyperactivity as well as a greater likelihood of impulsive aggression, self-injury and property destruction[ 19 ]. Affect dysregulation, the inability to properly regulate and modulate emotions, was not included in DSM-5 as a diagnostic feature of ADHD, but is emphasized in DM-ID2 as an important feature in individuals with developmental disabilities including ASD. The authors of the DSM-5 ADHD criteria later published an article emphasizing affect dysregulation as an important part of ADHD[ 21 ]. ADHD-associated mood fluctuations present an important source of impairment especially in those with developmental disabilities and ADHD. Especially in adults with ASD, the ADHD diagnosis may be overlooked, resulting in a bipolar or borderline personality disorder misdiagnosis.

ADHD medications are important for improving learning, speech and language, and executive functions including inhibitory self- control. These medications improve affect dysregulation in ASD, which often manifests as impulsive aggression when the person is frustrated. Response inhibition of affective fluctuations such as laughing or crying is impaired in ADHD, related to executive function deficits. A meta-analysis of executive function in ASD found that broad executive function deficits remain stable and do not improve across development in such individuals[ 22 ]. Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) is very commonly associated as well in ASD, and could complicate treatment of ADHD with stimulants since the latter may increase anxiety in a dose-related manner[ 23 ]. On the other hand, non-stimulant ADHD medications may help reduce OCD and repetitive behaviors in ASD, although studies are still needed. Medications for ADHD can be divided into stimulant and non-stimulant drug categories.

When to try stimulants in ASD?

Stimulants are more likely to show efficacy and tolerability in higher-functioning individuals with ASD who have predominantly ADHD symptoms in contrast to cases with OCD symptoms, prominent repetitive behaviors or self-injury. In the latter group, non-stimulant medications may be a more tolerable choice. Young children with ASD often begin their first ADHD medication trials when their disruptive behavior interferes with education of themselves and others in the classroom. As with TD young children with ADHD, the first drug tried is usually the stimulant MPH, in divided doses three times a day, up to 1 mg/kg/day or less; individual responses vary.

Dextroamphetamine (DEX) immediate release (ir) merits study in ASD, according to the author’s decades-long experience. DEX has double the potency and duration of action as MPH, notably 4 to 6 h. A meta-analysis comparing efficacy of stimulants in 23 controlled studies for ADHD found a modest advantage of amphetamines over MPH for treating ADHD in pediatric patients[ 24 ]. Divided doses given morning, lunch time, and a half-dose at 4 pm if needed, totaling approximately 0.5 mg/kg/day or less give good coverage, better than MPH. Overall, DEX ir produces less lunch-time appetite suppression, less anxiety and irritability than long-acting stimulants according to author experience. Despite the current low level of evidence for DEX in ASD, clinical trials are warranted, and patient trials in the office may be beneficial.

However, MPH is the only stimulant studied so far in ASD, with findings of lower tolerability and lower efficacy than in TD youth. Large studies include a multisite study by the group Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology (RUPP)[ 25 ], and a Cochrane database systematic review[ 26 ]. The RUPP study of 72 children with ASD, aged 5 to 13 years, found all low doses studied were superior to placebo for hyperactivity and impulsivity. Subjects were pre-selected for ability to tolerate a test dose of MPH for a week. Total doses, each given for a week, were 0.125 mg/kg, 0.25 mg/kg, and 0.5 mg/kg and were deliberately low in order to minimize side effects. However only 49% were responders, a rate much lower than the 75% response rate in TD children. Even the greatest effect size of 0.54 was significantly lower than that for ADHD response in TD children. Side effect rates were approximately double those found in TD children, and 18% exited the study early due to intolerable side effects. These included irritability, decreased appetite, and insomnia. Parent-rated lethargy, social withdrawal, and inappropriate speech increased significantly. There are also two small RCT studies and one multisite study of MPH for ADHD in ASD. Two small RCT studies of MPH for aggression in ASD found benefit over placebo on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist-Irritability (ABC-I) subscale[ 27 - 29 ]. Intolerable side effects were common in the latter study also, including mood changes, agitation and abnormal movements.

The Cochrane systematic review[ 26 ] of MPH in children and adolescents with ASD included 4 crossover studies, totaling 113 children ages 5 to 13 years; most (83%) were boys. There was a significant benefit on teacher-rated inattention but insufficient data to perform an impulsivity-outcome meta-analysis. Treatment duration for each dose of MPH was 1 wk. High-dose MPH significantly improved hyperactivity as rated by teachers in 4 studies, 73 subjects, ( P < 0.001) low quality evidence, and parents in 2 studies, 71 subjects ( P = 0.02), low quality evidence. Ratings were on the hyperactivity subscale of the ABC. MPH clinical usefulness is also limited by its short half-life of 2-4 h.

Of the long-acting stimulants in ASD, only one small study has been published. This small study of 24 children, mean age 8.8 years, found significant benefit of MPH-extended release in ASD[ 30 ]. However this was not a representative ASD sample, since the participants’ mean IQ was 85.0 (SD = 16.8). MPH-ER may be useful and more tolerable for example in high-functioning individuals with ASD. Comparative studies of long-acting stimulants are lacking in ASD, including for irritability[ 31 ]. Long-acting stimulants were designed to take effect and wear off gradually, and to reduce side effects and rebound effects in the general population with ADHD. However, clinical observations suggest that in ASD, long-acting stimulants may have even greater side effects than immediate-release preparations, including worsened anxiety, appetite suppression, self-injury, lip-licking, nail-picking, trichotillomania, and compulsive behaviors, in a dose-dependent manner. The more severe the ASD, the more of a problem such side effects present, although studies are needed. Therefore, non-stimulant ADHD medications may be preferable in these individuals.

When to try non-stimulant ADHD medications in ASD?

As stated, non-stimulant ADHD medications are preferable to stimulants for individuals who have more severe ASD, and those who also have prominent OCD, RRBs and self-injury. These include ATX, alpha agonists and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). Clinical experience in ASD suggests that these medications can be added to low-dose stimulants that are partially helpful if the person is unable to tolerate stimulant dose increases due to side effects. Several clinical trials in TD individuals have found efficacy and tolerability of ATX in combination with stimulants, although such combinations are not FDA-approved[ 32 ]. A recent review compared responses between MPH, ATX and guanfacine in 9 controlled studies of 430 children with ASD[ 33 ]. MPH and ATX were superior to placebo for ADHD. Poorer response was found in more cognitively disabled individuals.

Atomoxetine (ATX)

ATX is a noradrenergic reuptake inhibitor shown to produce improvements in inhibitory control as part of executive functions. Importantly, acute ATX administration increased behavioral inhibition as measured by a stop-signal task in adult ADHD not accompanied by ASD[ 34 ] as well as in normal adults without either ADHD or ASD[ 35 ]. Author experience confirms that ATX may be a good choice for impulsive aggression in ASD including in adults and minimally verbal individuals, and for poor focus and disorganization in higher-functioning individuals. A randomized, multisite 10-wk double-blind placebo-controlled trial of ATX, with or without parent training, was performed for ADHD in 128 children aged 5 to 14 years with ASD. ATX showed greatest efficacy together with parent- training, but also the drug alone was superior to placebo[ 36 ]. Overall, tolerability was good, to a maximum dose of 1.8 mg/kg/day; mean dose was 1.4 mg/kg/day. Dosing was divided into twice-daily doses, to reduce side effects. The most common side effects were nausea, decreased appetite, early morning wakening and fatigue. Suicidal ideation and QTc changes were not found, in contrast to findings in children without ASD[ 37 ]. In addition, another acute RCT study of 97 youths with ASD treated with ATX, including open long-term follow-up, showed moderately improved ADHD symptoms and side effects similar to those found in studies of ATX in youth with ADHD but no ASD[ 38 , 39 ].

ATX trials are warranted in ADHD in adults with ASD, especially for impulsive aggression, based on author experience. The strategy is to “start low and go slow” while response is observed for, using divided doses of twice a day to improve tolerability and coverage. A recent retrospective study disputes the need for extra caution however and found similar responses to ADHD treatments in adults with ADHD and ASD to those found in a comparison group with ADHD but no ASD[ 40 ]. The therapeutic window may be narrower in minimally verbal and lower-functioning individuals with more severe degrees of ASD, according to clinical experience. Should behavioral worsening occur after an ATX dose increase, the beneficial response is usually recaptured by dose reduction.

Amitriptyline

Amitriptyline in low doses may be especially useful if used with caution, in comparison with other available non-stimulant medications, despite a lack of comparative studies. TCAs including amitriptyline are second only to stimulants in ADHD efficacy, although most evidence for their use in ADHD is from studies of the second generation TCA desipramine in youth without ASD. An advantage over stimulants according to this author’s experience is that amitriptyline may benefit ADHD, anxiety, OCD, gastrointestinal pain, headaches, enuresis and insomnia[ 15 ]. Though currently there is a low level of published evidence, prospective studies are warranted, in the author’s opinion. A retrospective chart review on amitriptyline[ 41 ] published by the author’s group examined 50 tertiary-referred children and adolescents with ASD, ADHD and high rates of aggression and self-injury, who received low dose AMI (mean dose 1.3 ± 0.6 mg/kg/day) with mean trough blood level of 114.1 ± 50.5 ng/mL. Response occurred clinically in 60% of patients at the final visit, and in 82% of patients for at least 50% of follow-up visits. Importantly, 30% had failed ATX, and 40% had failed 3 or more other ADHD medication trials. Amtriptyline was used in combination with stimulants, most often low dose DEX ir, and also low dose risperidone or aripiprazole. In the low doses used amitriptyline did not cause complaints of constipation or urinary retention. Side effects included QTc increase on routine electrocardiogram, which did not halt treatment except in 3 cases with QTc > 440, behavioral activation and worsening of aggression. Prospective, randomized controlled studies of amitriptyline in ASD are warranted.

While a 2014 Cochrane review[ 42 ] of TCAs in TD youth showed no serious adverse events associated with taking TCAs, mild increases in pulse rates and diastolic blood pressure occurred. Of note is that the overdose risk with TCAs is lower in individuals with ASD since most individuals including adults with ASD do not self-administer their medications. TCAs should not be prescribed for use in chaotic households or those with a risk of overdose by a family member.

Alpha agonists

The class of alpha-agonist drugs is FDA-approved for ADHD in TD children but not in ASD. Since these drugs may benefit tics and Tourette disorder, they are usually a first-line treatment choice in such individuals. This drug class includes guanfacine, clonidine, long-acting guanfacine (Intuniv TM) and long-acting clonidine XR (Kapvay TM). An 8-wk multisite study of extended-release guanfacine in 62 children with ASD and ADHD, mean age 8.5 years, found a significant improvement in comparison with placebo. Modal guanfacine ER dose was 3 mg/day (range 1-4 mg/day)[ 43 ]. The most common side effects were fatigue, drowsiness and decreased appetite. For subjects on guanfacine, blood pressure dropped in the initial 4 wk, but returned almost to baseline by week 8. Pulse rate also dropped but remained lower than baseline at week 8. A small study of clonidine[ 44 ] examined response of 8 male children with autistic disorder in a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover design for ADHD symptoms. While parent-rated Conner’s questionnaire ADHD ratings improved significantly during clonidine treatment, teacher ratings were not significantly improved except for oppositional behavior. Side effects included drowsiness and decreased activity. Due to their short half-lives, the immediate-release preparations of clonidine and guanfacine should be dosed 3 times a day. Dosing is built up gradually while monitoring for dizziness, hypotension and bradycardia. Other side effects include weight gain, sedation and irritability.

Although alpha agonists improve attention, studies in otherwise TD youth with ADHD have shown their combination use with a stimulant medication produces greater attentional improvement than does either alone. Combination treatments of alpha agonists and stimulants are FDA-approved for ADHD in the non-ASD population, but not in ASD. Clinical experience suggests however that alpha agonists may be less helpful for ADHD symptoms in adults with ASD.

Thus in the author’s opinion, DEX, ATX and amitriptyline may be useful additions to treatment options for ADHD comorbid with ASD, including in adults.

EXISTING ANTIPSYCHOTIC STUDIES, AND EMERGING EVIDENCE FOR OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS

Antipsychotics are used to treat psychosis as well as irritability in ASD, and are classified into two classes: Atypical/novel antipsychotics and typical/classical antipsychotics. ASD core symptoms including odd, stereotyped talk on unusual restricted topics of interest are still often misdiagnosed as schizophrenia symptoms in everyday practice. Psychosis can also be confused with bizarre behavior related to subclinical seizures, in which case antiseizure medications may help. Psychotic disorders can be comorbid with ASD, including schizophrenia, delusional disorder, unspecified psychosis, or as a component of a major mood disorder such as bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder or schizoaffective disorder[ 45 ].

Typical antipsychotics

Typical antipsychotics block dopamine D2 receptors to alleviate psychosis or mania, but produce motor side effects including acute dystonias, extrapyramidal side effects (EPS), tardive dyskinesia and more rarely, neuroleptic malignant syndrome which can be fatal. Haloperidol was studied in early trials by Campbell and colleagues, in young children, but found to produce tardive withdrawal movements[ 46 , 47 ] and further studies were halted. According to clinical experience, typical antipsychotics often have a lag time to onset of response in individuals with ASD, and increasing the dose early in treatment especially of high potency antipsychotics like haloperidol may result in extremely severe EPS and dysphagia after a while, especially more severely disabled individuals, with resulting joint contractures[ 16 ]. Low potency typical antipsychotics including chlorpromazine produce hypotension, slowing, cognitive dulling and weight gain in those with developmental disabilities as well as in the general population. Thioridazine produced QTc prolongation and is no longer marketed.

The medium-potency, typical antipsychotic loxapine blocks serotonin as well as dopamine, and in low doses resembles an atypical antipsychotic in positron emission tomography (PET) studies, but with less or no weight gain[ 48 - 50 ] which will be discussed in more detail below. Atypical antipsychotics were designed to overcome these motor side effects of typical antipsychotics by a different mechanism of action, notably by blocking serotonin as well as dopamine receptors, amongst others. However an unanticipated side effect of the atypical antipsychotics turned out to be weight gain, Type II diabetes and multiple other medical side effects[ 51 ], which are more severe in those with developmental disabilities. Atypical antipsychotics also produce possible motor side effects including neuroleptic malignant syndrome and tardive dyskinesia in the general population but also in ASD.

Atypical antipsychotics

Only two antipsychotics are FDA-approved in ASD, for children ages 6 years and older with irritability, notably risperidone and aripiprazole. The RUPP multisite 8-wk risperidone RCT study of 101 children and adolescents, mean age 8.8 years, found significant efficacy of risperidone vs placebo for irritability on the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement subscale[ 52 ], and the ABC-I subscale[ 29 ] at a mean dose of 1.8 mg/day. Effect size was 1.2. Side effects included significant weight gain, appetite increase in 73%, fatigue in 59%, and drowsiness in 49%, as well as prolactin elevation. The greatest benefits reported by parents were for self-injury and aggression. Another larger multisite RCT study of risperidone and parent training in 124 children and adolescents ages 4 through 13 found that parent training could lessen the dose of risperidone needed[ 53 ]. Risperidone doses were a mean of 2.26 mg/day or 0.071 mg/ kg in the risperidone-only group, vs 1.98 mg/day or 0.066 mg/kg ( P = 0.04, two-sided test) in the combination group of risperidone plus parent training.

Weight gain associated with risperidone treatment was marked, especially in some individuals in a double-blind crossover study performed by the author’s group, of risperidone vs placebo for challenging behaviors in participants aged 6 to 65 with ID and ASD[ 54 ]. In a subset of 19 subjects over approximately a year, weight gain was as follows: Children ( n = 5) ages 8 to 12 years gained 8.2 kg on average, adolescents ( n = 6) aged 13 to 16 years gained 8.4 kg on average, and adults gained 5.4 kg on average[ 55 ]. Prolactin elevation is greater with risperidone than with other atypical antipsychotics. Breast development, galactorrhea and amenorrhea should be monitored[ 56 ]. It is important to monitor for weight gain and metabolic syndrome abnormalities, notably hypertension, glucose elevation, midline obesity, and triglyceride elevations. These are important predisposing factors for diabetes, stroke, myocardial infarction, and cognitive dysfunction and brain abnormalities[ 55 ]. In the author’s experience, keeping risperidone doses low at or below 2 mg/day total, and splitting dosing to three times a day can help minimize weight gain. Importantly, clinical experience suggests that risperidone may be the most effective antipsychotic for self-injurious behavior.

A multisite RCT of aripiprazole in 218 children and adolescents with ASD, aged 6-17 years, mean age 9.3 years, found significant improvement in irritability in the aripiprazole vs the placebo group. Doses were 5, 10 or 15 mg/day in this 8-wk, parallel groups study. However, there was no protection against long-term relapse, the author agrees with this finding based on clinical practice, meaning that the efficacy may decrease over time, and increasing the dose may not recapture the initial good response. Side effects included sedation, the most common side effect leading to discontinuation, and significant weight gain[ 57 ]. Mean weight increases at week 8 were 0.3 kg for placebo, 1.3 kg for 5 mg/day, 1.3 kg for 10 mg/day and 1.5 kg for 15 mg/day groups, all P < 0.05 vs placebo. Importantly, aripiprazole in a low dose of 1 mg/day normalizes prolactin for example in an individual responding to risperidone who has elevated prolactin producing gynecomastia[ 58 ]. One small open pilot study compared olanzapine with haloperidol in children with autistic disorder[ 59 ] and one studied ziprasidone vs placebo[ 60 ] in ASD. Metformin for weight gain treatment with atypical antipsychotics was studied in a 16-wk, 4-center multisite RCT of 60 children. Metformin was associated with reductions in future weight gain, notably body mass index (BMI) z-scores decreased significantly more from baseline to week 16 than in the placebo group ( P = 0.003). However metformin did not alter lipid abnormalities, and gastrointestinal side effects identified included abdominal discomfort, abdominal pains and diarrhea[ 61 ] (in contrast to loxapine substitution discussed below).

Loxapine resembles an atypical antipsychotic at 5-10 mg/day

Loxapine shows promise clinically in adolescents and adults with ASD according to preliminary studies, and RCTs are warranted. This antipsychotic is a dibenzoxazepine tricyclic structure classified in the medium potency group of the typical antipsychotic class. Loxapine was designed in the 1980s to resemble clozapine but without the clozapine molecular component causing agranulocytosis. Loxapine has a history of extensive use in schizophrenia, usually at 40 to 80 mg/day (maximum dose of 200 mg/day) and may lack the marked weight gain and metabolic side effects of clozapine and other atypical antipsychotics[ 62 ]. A case report of a 10 year old female with autistic disorder who responded to loxapine 15 mg/day described its efficacy for treatment-resistant aggression and self-injurious behavior[ 63 ]. In low doses of 5 to 10 mg/day, loxapine resembles an atypical antipsychotic on PET brain studies, but lacks the weight gain and metabolic side effects[ 64 , 65 ]. A prospective 12-wk open trial of loxapine for irritability and aggression in 16 adolescents and adults with ASD[ 48 ], demonstrated that loxapine in low doses of 5 to 10 mg per day significantly improved irritability ratings on the ABC-I, with large pre- to post- treatment effect sizes on 4 subscales, d = 1.0-1.1. Fourteen of 16 subjects completed the study, all of whom had Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement scale ratings of Very Much Improved or Much Improved at week 12. Larger clinical trials are warranted.

A retrospective loxapine chart review, also by the author’s group, of 15 outpatient adolescents and adults with ASD and irritability, illustrates the strategy of adding loxapine 5-10 mg/day, followed by extremely gradual taper of offending antipsychotics, which reversed weight gain, metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance including diabetes[ 49 ]. All those in the series had gained weight and manifested at least one other metabolic abnormality since starting on the baseline antipsychotic. Fourteen of the subjects were being treated with atypical antipsychotics and one received chlorpromazine, prior to addition of loxapine 5 to 10 mg daily, followed by behavioral improvement and then taper of the offending antipsychotic. Final loxapine dose in 12 subjects was 5 mg/day, and 10 mg/day in 2 subjects. At the time of chart review, all but one subject (93%) were Very Much Improved or Much Improved on CGI-I. Mean weight loss after an average of 17 mo (range 7 to 26 mo) on loxapine was -5.7 kg, with BMI reduction averaging -1.9. Mean reduction in triglycerides was -33.7 mg/dL ( P = 0.03). Two subjects were tapered off metformin by their endocrinologists, and one person’s insulin for Type II diabetes was discontinued. Weight loss did not differ in those already receiving metformin at the time of loxapine add-on ( n = 4) though the numbers are small and the reader is therefore cautioned.

In a long-term outcomes chart review study, of 34 children, adolescents and adults with ASD, mean age 23.4 years (range 8 to 32 years), long-term low-dose loxapine at a mean dose of 8.9 mg/day (range 5 to 30 mg) was associated with lower rates of tardive dyskinesia and EPS than expected for a typical antipsychotic, mean treatment duration was 4.2 years[ 50 ]. Stahl[ 62 ] describes the addition of low doses of a classical antipsychotic to an atypical antipsychotic to “lead in” or “top up” the effect. Using loxapine add-on at 5-10 mg/day, the author has been able to minimize risperidone dose increases above 1.5-2 mg a day total of risperidone and this strategy appears weight-sparing.

Dysphagia and bowel obstruction associated with antipsychotics

A clinical word of caution is important regarding minimally verbal and neurologically impaired individuals treated with antipsychotics. Dysphagia is a common but often overlooked side effect of antipsychotics, predisposing to aspiration pneumonia and initiation of parenteral feeding after surgical insertion of gastrostomy tubes, which may then be life-long if the antipsychotic medications are not changed. Aspiration pneumonia is more common in those with severe developmental disabilities and minimally verbal individuals and those with cerebral palsy or quadriplegia treated with even moderate doses of antipsychotics, especially if the individual also receives concomitant cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6)-inhibiting SSRIs[ 66 ].