A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Guidelines and Guidance Library

- Core Practices

- Isolation Precautions Guideline

- Disinfection and Sterilization Guideline

- Environmental Infection Control Guidelines

- Hand Hygiene Guidelines

- Multidrug-resistant Organisms (MDRO) Management Guidelines

- Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections (CAUTI) Prevention Guideline

- Tools and resources

- Evaluating Environmental Cleaning

- Show All Home

CDC's Core Infection Prevention and Control Practices for Safe Healthcare Delivery in All Settings

At a glance.

Core Infection Prevention and Control Practices for Healthcare

Introduction

Adherence to infection prevention and control practices is essential to providing safe and high quality patient care across all settings where healthcare is delivered

This document concisely describes a core set of infection prevention and control practices that are required in all healthcare settings, regardless of the type of healthcare provided. The practices were selected from among existing CDC recommendations and are the subset that represent fundamental standards of care that are not expected to change based on emerging evidence or to be regularly altered by changes in technology or practices, and are applicable across the continuum of healthcare settings. The practices outlined in this document are intended to serve as a standard reference and reduce the need to repeatedly evaluate practices that are considered basic and accepted as standards of medical care. Readers should consult the full texts of CDC healthcare infection control guidelines for background, rationale, and related infection prevention recommendations for more comprehensive information.

The core practices in this document should be implemented in all settings where healthcare is delivered. These venues include both inpatient settings (e.g., acute, long-term care) and outpatient settings (e.g., clinics, urgent care, ambulatory surgical centers, imaging centers, dialysis centers, physical therapy and rehabilitation centers, alternative medicine clinics). In addition, these practices apply to healthcare delivered in settings other than traditional healthcare facilities, such as homes, assisted living communities, pharmacies, and health fairs.

Healthcare personnel (HCP) referred to in this document include all paid and unpaid persons serving in healthcare settings who have the potential for direct or indirect exposure to patients or infectious materials, including body substances, contaminated medical supplies, devices, and equipment; contaminated environmental surfaces; or contaminated air.

CDC healthcare infection control guidelines 1-17 were reviewed, and recommendations included in more than one guideline were grouped into core infection prevention practice domains (e.g., education and training of HCP on infection prevention, injection and medication safety). Additional CDC materials aimed at providing general infection prevention guidance outside of the acute care setting 18-20 were also reviewed. HICPAC formed a workgroup led by HICPAC members and including representatives of professional organizations (see Contributors in archives for full list). The workgroup reviewed and discussed all of the practices, further refined the selection and description of the core practices and presented drafts to HICPAC at public meeting and recommendations were approved by the full Committee in July 2014. In October 2022, the Core Practices were reviewed and updated by subject matter experts within the Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion at CDC. The addition of new practices followed the same methodology employed by the Core Practices Workgroup but also included review of pathogen-specific guidance documents 21-22 that were created or updated after July 2014. These additions were presented to HICPAC at the November 3, 2022 meeting. Future updates to the Core Practices will be guided by the publication of new or updated CDC infection prevention and control guidelines.

Core Practices Table

Infection control.

CDC provides information on infection control and clinical safety to help reduce the risk of infections among healthcare workers, patients, and visitors.

For Everyone

Health care providers, public health.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices

Infection prevention and control refers to practices that can prevent or reduce the risk of transmission of microorganisms. Evidence-based best practices for infection prevention and control provide guidelines to healthcare providers to ensure safe, quality care is provided to clients, visitors, healthcare providers, and the healthcare environment.

When infection prevention and control practices are used consistently, the transfer of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) can be prevented in healthcare settings. HAIs are infections that occur when a person is infected with a pathogen during their care in a healthcare setting. A survey conducted by the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program (2020) found that participating Canadian hospitals estimated that 7.9% of clients had at least one HAI. Hand hygiene is considered the most important and effective measure to prevent HAIs. HAIs will be discussed further in Chapter 3 .

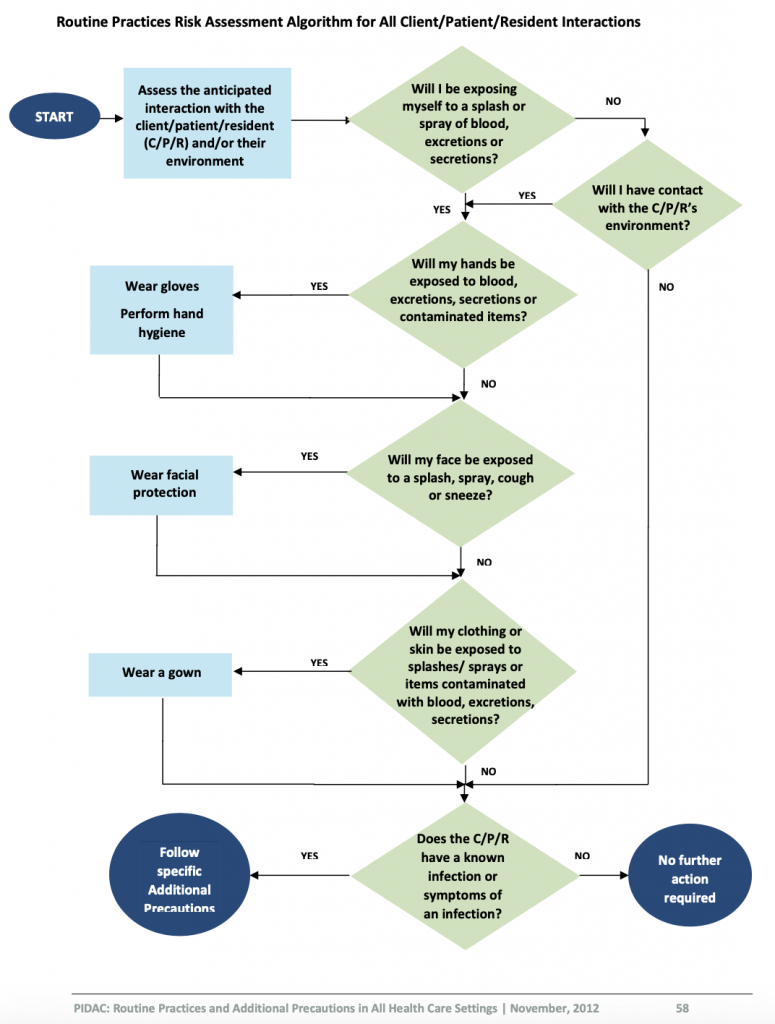

Prior to providing care, healthcare providers must perform a point-of-care risk assessment of the environment before every interaction with clients to ensure safe care and determine the potential risk for exposure to infections. Risks include exposure to blood, body fluids, mucous membranes, non-intact skin, contaminated surfaces or soiled items, and even airborne particles. Once you have completed a risk assessment, you need to assess how to decrease your risk of exposure, determine the infection prevention and control practices required to minimize your risk (e.g., hand hygiene, required PPE) and how to prevent the risk transmission to others (Provincial Infectious Diseases Advisory Committee [PIDAC], 2012).

Performing a risk assessment is foundational in the prevention of infection transmission. Public Health Ontario outlines how to perform a risk assessment related to routine practices and additional precautions ( https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/r/2012/rpap-risk-assessment.pdf?la=en ).

When performing the risk assessment, you need to ask yourself a series of questions prior to providing care for every client. The answers from the risk assessment will help you to identify and determine which infection prevention and control strategies you need to implement to reduce the risk of transmission of microorganisms.

Performing a Risk Assessment

Review Public Health Ontario (2012) decision trees Performing a Risk Assessment related to Routine Practices and Additional Precautions to determine the steps required by healthcare providers to assess their risk.

Digital Story with Czarielle Dela Cruz

Test your Knowledge on Performing a Risk Assessment

Medical and sterile asepsis.

Sterile asepsis, or sterile technique, is a strict technique to eliminate all microorganisms from an area (Potter et al., 2019). Examples include using steam, hydrogen peroxide, or other sterilizing agents to clean surgical tools.

Routine Practices

Routine practices include performing a point-of-care risk assessment, hand hygiene, wearing the appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) when needed, respiratory etiquette, safe handling of sharps, controlling the surrounding environment, using avoidance procedures and actions, and following environmental cleaning and disinfecting protocols. To decrease the risk of infections, it is your responsibility to ensure that you understand and consistently follow routine practices with all clients, with every interaction, and in every healthcare setting to prevent and control the transmission of microorganisms (PIDAC, 2012). The principles of routine practices are based on the assumption that all clients are potentially infectious, even when asymptomatic. Infection prevention and control routine practices should be used to prevent exposure to blood, body fluids, secretions, excretions, mucous membranes, non-intact skin, or soiled items (PIDAC, 2012).

All clients can potentially be infectious; thus, it is important to consider which routine practices to follow and why. Routine practices refer to minimum practices that should be used with all clients. Routine practices will prevent transmission of microorganisms from client to client, client to healthcare provider, healthcare provider to client, and healthcare provider to healthcare provider.

Routine Practices include:

Additional precautions.

Certain types of infectious microorganisms require additional precautions in addition to routine practices. Additional precautions include contact, droplet, and airborne precautions or a combination of these precautions. The mode of transmission of the infectious agent will determine which additional precautions are required. The client may have a suspected infection according to their clinical signs and symptoms, or could have an infection confirmed with a test result. Healthcare providers must follow the additional precaution guidelines according to the healthcare setting policies.

Additional precautions can include PPE, specialized equipment (e.g., N95 respirator), specialized accommodation and signage, client-dedicated equipment, advanced cleaning protocols, limited movement of the client and specific environmental protocols (e.g., client placement, negative-pressure-engineered rooms). Additional precautions will be discussed further in Chapter 6 .

Routine Practices and Additional Precautions

Test your knowledge.

Attribution

This page was remixed with our own original content and adapted from:

Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care — Thompson Rivers University Edition by Renée Anderson, Glynda Rees Doyle, and Jodie Anita McCutcheon is used under a CC BY 4.0 Licence . This book is an adaptation of Clinical Procedures of Safer Patient Care by Glynda Rees Doyle and Jodie Anita McCutcheon, which is under a CC BY 4.0 Licence . A full list of changes and additions made by Renée Anderson can be found in the About the Book section.

Physical Examination Techniques: A Nurse’s Guide by Jennifer Lapum, Michelle Hughes, Oona St-Amant, Wendy Garcia, Margaret Verkuyl, Paul Petrie, Frances Dimaranan, Mahidhar Pemasani, and Nada Savicevic is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner Copyright © by Michelle Hughes; Audrey Kenmir; Oona St-Amant; Caitlin Cosgrove; and Grace Sharpe is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Infection control.

Yacob Habboush ; Siva Naga S. Yarrarapu ; Nilmarie Guzman .

Affiliations

Last Update: September 4, 2023 .

- Continuing Education Activity

Infection control refers to the policy and procedures implemented to control and minimize the dissemination of infections in hospitals and other healthcare settings with the main purpose of reducing infection rates. Infection control as a formal entity was established in the early 1950s in the United States. By the late 1950s and 1960s, a small number of hospitals began to recognize healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and implemented some of the infection control concepts. This activity reviews the types of infection control methods and their indications and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in following principles of infection control to improve outcomes.

- Identify the single most effective and least expensive way for providers to prevent the spread of infection.

- Summarize standard precautions, contact precautions, droplet precautions, and airborne precautions.

- Review the types of precautions required for a patient with tuberculosis versus a patient with Clostridium difficile.

- Outline interprofessional team strategies for ensuring proper infection control measures are being followed to prevent the spread of infection in healthcare institutions.

- Introduction

Infection control refers to the policy and procedures implemented to control and minimize the dissemination of infections in hospitals and other healthcare settings with the main purpose of reducing infection rates. Infection control as a formal entity was established in the early 1950s in the United States. By the late 1950s and 1960s, a small number of hospitals began to recognize healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and implemented some of the infection control concepts. The primary purpose of infection control programs was to focus on the surveillance for HAIs and in-cooperate the basic understandings of epidemiology to elucidate risk factors for HAIs [1] . However, most of the infection control programs were organized and managed by large academic centers rather than public health agencies which lead to sporadic efficiency and suboptimal outcomes. It was not until the late 19th and early 20th century when the new era in infection control was started through three pivotal events. These events included the Institute of Medicine’s 1999 report on errors in health care [2] , the 2002 Chicago Tribune representation on HAIs [3] , and the 2004/2006 publications of the significant reductions in bloodstream infection rate through the standardization of central venous catheter insertion process [4] . This new era in healthcare epidemiology is characterized by consumer demands for more transparency and accountability, increasing scrutiny and regulation, and expectations for rapid reductions in HAIs rates [5] . The role of infection control is to prevent and reduce the risk for hospital-acquired infections. This can be achieved by implementing infection control programs in the forms of surveillance, isolation, outbreak management, environmental hygiene, employee health, education, and infections prevention policies and management.

- Indications

Infection control program has the main purpose of preventing and stopping the transmission of infections. Specific precautions are needed to prevent infection transmission depending on the microorganism.

The following are examples of indications for transmission-based precautions:

- Standard precautions: Used for all patient care. It includes hand hygiene, personal protective equipment, appropriate patient placement, clean and disinfects patient care equipment, textiles and laundry management, safe injection practices, proper disposal of needles and other sharp objects.

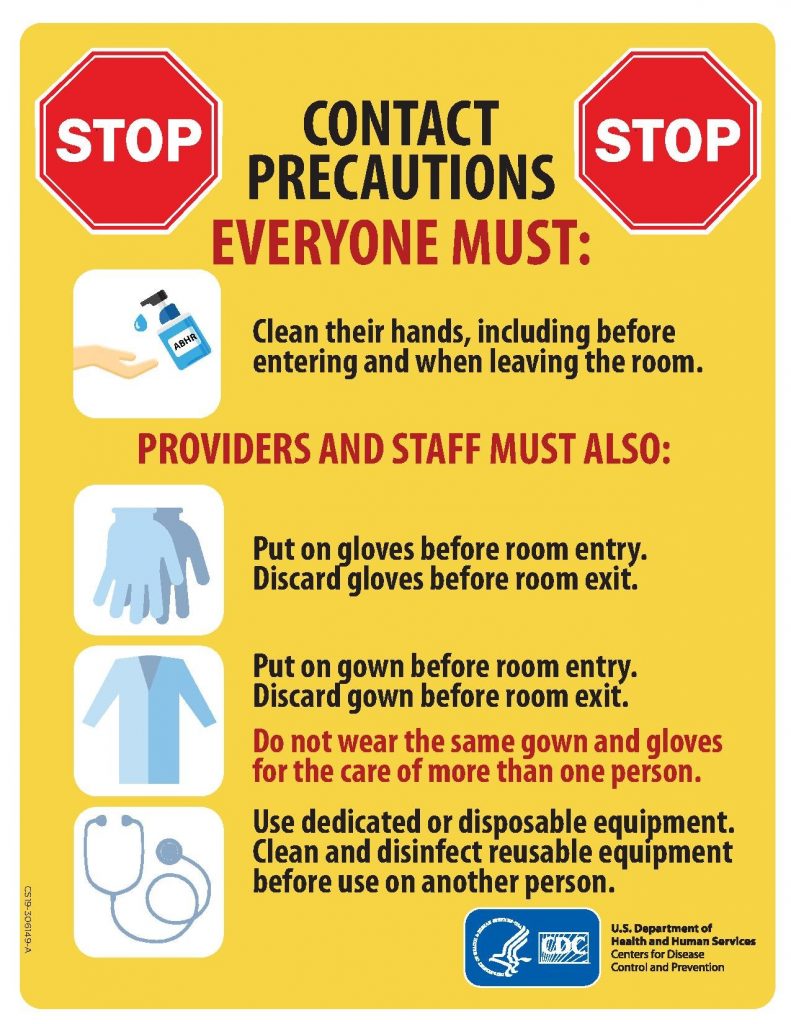

- Contact precaution: Used for patients with known or suspected infections that can be transmitted through contact. For those patients, standard precautions are needed, plus limit transport and movement of patients, use disposable patient care equipment, and thorough cleaning and disinfection strategies. Patients with acute infectious diarrhea such as Clostridium difficile , vesicular rash, respiratory tract infection with a multidrug-resistant organism, abscess or draining wound that cannot be covered need to be under contact precautions.

- Droplet precautions: Used for patients with known or suspected infections that can transmit by air droplets through the mechanism of a cough, sneeze, or by talking. In such cases, it is vital to control the source by placing a mask on the patient, use standard precautions plus limitation on transport and movement. Patients with respiratory tract infection in infants and young children, petechial or ecchymotic rash with fever, and meningitis are placed under droplet precautions.

- Airborne precautions: Use for patients with known or suspected infections that can be transmitted by the airborne route. Those patients require to be in an airborne infection isolation room with all the previously mentioned protections. The most important pathogens that need airborne precautions are tuberculosis, measles, chickenpox, and disseminated herpes zoster. Patients with suspected vesicular rash, cough/fever with pulmonary infiltrate, maculopapular rash with cough/coryza/fever need to be under airborne precaution.

Multiple of those indications might require more than one precaution to ensure efficient standard and transmission-based precautions. For example, patients with suspected C. difficile need to be under contract and standard precautions, tuberculosis need to be under airborne, contact, and standard precautions.

Healthcare facilities must have the necessary equipment to implement the standard precautions for all patient. The most significant precaution that is effective in preventing infection transmission is hand hygiene. This is achieved by washing hands with soap and warm water and/or by hand rubbing with alcohol or nonalcohol based hand sanitizer. Gloves can also be used as a standard precaution, new gloves have to be used for each patient and must be disposed of after each patient interaction. Other personal protective equipment includes facial protection (procedure/surgical masks, goggles, face shield) and gown before entering the patient's room. Infection control equipment also includes the housekeeping tools where adequate and routine disinfection of surfaces and floors are implemented. Also, linens have to be handled and transported in a manner which prevents skin and mucous exposure by using the appropriate personal protective equipment.

Hospitals need to attain hospital epidemiologists, infection preventionists, and an infection control committee to organize a well-structured and implemented infection control program. The hospital epidemiologist is required to interface with many of the hospital departments and administrators to discuss their responsibilities, expectations, and available resources. The epidemiologist generally oversees the infection prevention program and in some cases the quality improvement program. A physician with a subspecialty in infectious disease usually holds the position [6] . A registered nurse with a background in clinical practice, epidemiology, and basic microbiology typically hold the infection preventionist title. Hospitals can have multiple infection preventionists depending on the number of beds available, mix of patients, and the Center for Disease Contol and Prevention (CDC) recommendations [7] . The last aspect of a functioning infection control program is the infection control committee, which consists of an interprofessional group of clinicians, nurses, administrators, epidemiologist, infection preventionists and other representatives from the laboratory, pharmacy, operating rooms, and central services. The responsibilities of this committee are to generate, implement, and maintain policies related to infection control [7] .

- Technique or Treatment

To achieve a successful and functioning infection control program, a hospital can implement the following measures:

Surveillance: The primary aim of surveillance programs is to assess the rate of infections and endemic likelihood. Generally, hospitals target surveillance for HAIs in areas where the highest rate of infection is, including intensive care units (ICUs), hematology/oncology, and surgery units. However, surveillance has expanded in the recent years to include a hospital-wide based surveillance as it is becoming a mandatory requirement by the public health authorities in multiple states [8] . This change has also been empowered by the wide implementation of the electronic health records in most hospitals in the United States, and now it is easy for any medical provider to access the electronic records at patients’ bedside and assess risks and surveillance data for each patient. Most hospitals have developed sophisticated algorithms in their electronic health systems that could streamline surveillance and identify patients at highest risk for HAIs. Hence, a hospital-wide surveillance targeting a specific infection could be implemented relatively easily. Public health agencies require that hospitals report some specific infections to strengthen the public health surveillance system [9] .

Isolation: The main purpose of isolation is to prevent the transmission of microorganisms from infected patients to others. Isolation is an expensive and time-consuming process, therefore, should only be utilized if necessary. On the other hand, if isolation is not implemented then we risk the increase in morbidity and mortality, henceforth, increasing overall healthcare cost. Hospitals that operate based on single-patient per room can implement isolation efficiently, however, significant facilities still have a substantial number of double-patient rooms which is challenging for isolation. [10] . The CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practice Advisory Committee have issued a guideline to outline the approaches to enhance isolation. These guidelines are based on standard and transmission-based precautions. The standard precaution refers to the assumption that all patients are possibly colonized or infected with microorganisms, therefore, precautions are applied to all patients, at all times and all departments. The main elements for standard precautions include hand hygiene (before and after patient contact), personal protective equipment (for contact with any body fluid, mucous membrane, or nonintact skin), and safe needle practices (use one needle per single dose medication per single time, then dispose of it is a safe container) [11] . Other countries such as the United Kingdom have also adopted the bare below the elbows initiative that requires all healthcare providers to wear short-sleeved garments with no accessories including rings, bracelets, and wrist watches. As for the transmission-based precautions, a cohort of patients is selected based on their clinical presentations, diagnostic criteria, or confirmatory tests with specific indication of infection or colonization of microorganisms to be isolated. In these cases, a requirement for airborne/droplet/contact precautions is necessary. These precautions are designed to prevent the transmission of disease based on the type of microorganism [12] .

Outbreak Investigation and Management: Microorganisms outbreaks can be identified through the surveillance system. Once a particular infection monthly rate crosses the 95% confidence interval threshold, an investigation is warranted for a possible outbreak. Also, clusters of infections can be reported by the healthcare providers of laboratory staff which should be followed by an initial investigation to assess if this cluster is indeed an outbreak. Usually, clusters of infections involve a common microorganism which can be identified by using the pulsed-field gel electrophoresis or the whole-genome sequencing which provides a more detailed tracking of the microorganism. Most outbreaks are a result of direct or indirect contact involving multidrug-resistant organism. Infected patients have to be separated, isolated if needed, and implementation of the necessary contact precautions, depending on what the suspected cause of infection is, have to be enforced to control such outbreaks [13] .

Education: Healthcare professionals need to be educated and periodically reinforce their knowledge through seminars and workshops to ensure high understanding of how to prevent communicable diseases transmission. The hospital might develop infection prevention liaison program by appointing a healthcare professional who could reach out and disseminate the infection prevention information to all members of the hospital.

Employee Health: It is essential for the infection control program to work closely with employee health service. Both teams need to address important topics related to the well-being of employees and infection prevention, including management of exposure to bloodborne communicable diseases and other communicable infections. Generally, all new employees undergo a screening by the employee health service to ensure that they are up-to-date with their vaccinations and have adequate immunity against some of the common communicable infections such as hepatitis B, rubella, mumps, measles, tetanus, pertussis, and varicella. Moreover, healthcare employees should always be encouraged to take the annual influenza vaccination. Also, periodic test for latent tuberculosis should be performed assess for any new exposure. Employ health service should develop proactive campaigns and policies to engage employees in their wellbeing and prevent infections.

Antimicrobial Stewardship: Antimicrobials are widely used in the inpatient and outpatient settings. Antimicrobial usage widely varies between hospitals, commonly, a high percentage of patients admitted to hospitals are administered with antibiotics. Increasingly, hospitals are adapting antimicrobial stewardship programs to control antimicrobial resistance, improve outcomes, and reduce healthcare costs. Antimicrobial stewardship should be programmed to monitor antimicrobial susceptibility profiles to anticipate and assess any new antimicrobial resistance patterns. These trends need to be correlated with the antimicrobial agents used to evaluate susceptibility [14] . Antimicrobial stewardship programs can be designed to be active and/or passive and can target pre-prescription or post-prescription periods. In the pre-prescription period, an active program includes prescriptions restrictions and preauthorization, while passive initiative includes education, guidelines, and antimicrobial susceptibility reports. On the other hand, an active post-prescription program would focus on a real-time feedback provision to physicians regarding antibiotic usage, dose, bioavailability, and susceptibility with automatic conversion of intravenous to oral formulations, while passive post-prescription involves the integration of the electronic medical records to generate alerts for prolonged prescriptions and antibiotic-microorganism mismatch [15] .

Policy and Interventions: The main purpose of the infection control program is to develop, implement, and evaluate policies and interventions to minimize the risk for HAIs. Policies are usually developed by the hospital’s infections control committee to enforce procedures that are generalizable to the hospital or certain departments. These policies are developed based on the hospital’s needs and evidence-based practice. Interventions that impact infection control can be categorized into two categories; vertical and horizontal interventions. The vertical intervention involves the reduction of risk from a single pathogen. For example, the surveillance cultures and subsequent isolation of patients infected with Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Whereas, horizontal intervention targets multiple different pathogens that are transmitted in the same mechanism such as the handwashing hygiene, where clinicians are required to wash their hands before and after any patient contact which will prevent the transmission of multiple different pathogens. Vertical and horizontal interventions can be implemented simultaneously and are not mutually exclusive. However, vertical interventions might be more expensive and would not impact the other drug-resistant pathogens, while horizontal intervention might be a more affordable option with more impactful results if implemented appropriately [16] .

Environmental Hygiene: As the inpatient population becomes more susceptible to infections the emphasize on environmental hygiene has increased. Hospital decontamination through the traditional cleaning methods is notoriously inefficient. Newer methods including steam, antimicrobial surfaces, automated dispersal systems, sterilization techniques and disinfectants have a better effect in limiting transmission of pathogens through the surrounding environment [17] . The CDC has published guidelines that emphasize the collaboration between federal agencies and hospital engineers, architectures, public health and medical professionals to manage a safe and clean environment within hospitals which include air handling, water supply, and construction [18] .

- Clinical Significance

Infection control clinically translates to identifying and containing infections to minimize its dissemination. Clinicians play a significant role in infection control by identifying patients' signs and symptoms suspicious for a transmissible infection such as tuberculosis. Precaution orders have to be placed and implemented even before a confirmatory diagnosis is reached to avoid the possible transmission of the infectious pathogen. Clinically, an efficient infection control program results into fewer infection rates and lower risk for the development of multidrug-resistant pathogens. Hospital-acquired infections are one of the most common healthcare complications. Therefore simple standard precautions such as hand hygiene can prove to be highly effective. In fact, the most effective and least expensive way for clinicians to also apply infection control principles is by washing hands before and after any patient interaction [19] . Hence, hospitals need to promote and enable handwashing by providing reminders at all bedsides and having sinks or hand sanitizer stations available at the entrance to each room in the hospital. Another simple measure can be to educate patient always to try to use their forearm to block their cough or sneeze to avoid the transmission of droplets and the direct contamination of their hands by which pathogens can be transferred to other surfaces.

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Infection control has many challenges especially with the increasing number of hospitalized patients, a greater prevalence of invasive technologies, and a higher prevalence of immunocompromised patients [20] . Poor infection control programs lead to increased rates of infections, increase the likelihood of multidrug-resistant bacterias, and increases the risk of outbreaks in specific departments that might disseminate to the entire hospital and community. Resources are one of the major limitations in achieving an optimal infection control program; hospital epidemiologists should consider the balance between cost, clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, and economic impact when considering new interventions. Hospital epidemiologists also need to assess the latest evidence-based literature to make certain that all infection control policies are up-to-date and to monitor the newly emerging multidrug-resistant pathogens. The major direct complication of an inappropriately managed infection control program is infection risk for the patient. Patients might be at risk for bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic infection. If the infection is severe, it can spread to the bloodstream leading to sepsis and possible septic shock which are life-threatening. All healthcare workers have a duty to prevent infection and maintain an aseptic environment when possible. Nursing is on the front lines of this issue, since they routinely have the highest level of contact with the patient, and have access to all aspects of the facility; their observations and recommendations should be taken seriously by all members of the interprofessional healthcare team. The most basic preventive method is by washing hands.

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Disclosure: Yacob Habboush declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Siva Naga Yarrarapu declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Nilmarie Guzman declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Habboush Y, Yarrarapu SNS, Guzman N. Infection Control. [Updated 2023 Sep 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- New York State Infection Control. [StatPearls. 2024] New York State Infection Control. Habboush Y, Benham MD, Louie T, Noor A, Sprague RM. StatPearls. 2024 Jan

- Medical Error Reduction and Prevention. [StatPearls. 2024] Medical Error Reduction and Prevention. Rodziewicz TL, Houseman B, Vaqar S, Hipskind JE. StatPearls. 2024 Jan

- Review Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies (Vol. 6: Prevention of Healthcare–Associated Infections) [ 2007] Review Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies (Vol. 6: Prevention of Healthcare–Associated Infections) Ranji SR, Shetty K, Posley KA, Lewis R, Sundaram V, Galvin CM, Winston LG. 2007 Jan

- Prospective surveillance of device-associated health care-associated infection in an intensive care unit of a tertiary care hospital in New Delhi, India. [Am J Infect Control. 2018] Prospective surveillance of device-associated health care-associated infection in an intensive care unit of a tertiary care hospital in New Delhi, India. Kumar S, Sen P, Gaind R, Verma PK, Gupta P, Suri PR, Nagpal S, Rai AK. Am J Infect Control. 2018 Feb; 46(2):202-206. Epub 2017 Oct 16.

- Review Hospital Infection Prevention: How Much Can We Prevent and How Hard Should We Try? [Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2019] Review Hospital Infection Prevention: How Much Can We Prevent and How Hard Should We Try? Bearman G, Doll M, Cooper K, Stevens MP. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2019 Feb 2; 21(1):2. Epub 2019 Feb 2.

Recent Activity

- Infection Control - StatPearls Infection Control - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- Discussions

- Certificates

- Collab Space

- Course Details

- Announcements

Infection prevention and control (IPC) is an essential component of healthcare quality and patient safety. In this module you will learn how and why healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) occur and how IPC reduces their risk and spread.

Course contents

Introduction to ipc:, enroll me for this course, certificate requirements.

- Gain a Record of Achievement by earning at least 70% of the maximum number of points from all graded assignments.

Safety and Infection Control NCLEX Practice Quiz (75 Questions)

Welcome to your NCLEX practice quiz on Safety and Infection Control. According to the NCLEX-RN test plan , about 9 to 15% of questions will come from this subcategory that includes content about the “ nurse ‘s ability required to protect clients, families, and healthcare personnel from health and environmental hazards.” Good luck, and hope you will learn a lot from this quiz.

Safety and Infection Control Nursing Test Banks

For this nursing test bank , we have included 75 NCLEX practice questions related to the Safety and Infection Control subcategory divided into three sets. Patient safety and infection control are essential and vital components of quality nursing care. A nurse’s ability to think critically and use this knowledge in the delivery of nursing care is essential to the well-being of the patients.

Quiz Guidelines

Before you start, here are some examination guidelines and reminders you must read:

- Practice Exams : Engage with our Practice Exams to hone your skills in a supportive, low-pressure environment. These exams provide immediate feedback and explanations, helping you grasp core concepts, identify improvement areas, and build confidence in your knowledge and abilities.

- You’re given 2 minutes per item.

- For Challenge Exams, click on the “Start Quiz” button to start the quiz.

- Complete the quiz : Ensure that you answer the entire quiz. Only after you’ve answered every item will the score and rationales be shown.

- Learn from the rationales : After each quiz, click on the “View Questions” button to understand the explanation for each answer.

- Free access : Guess what? Our test banks are 100% FREE. Skip the hassle – no sign-ups or registrations here. A sincere promise from Nurseslabs: we have not and won’t ever request your credit card details or personal info for our practice questions. We’re dedicated to keeping this service accessible and cost-free, especially for our amazing students and nurses. So, take the leap and elevate your career hassle-free!

- Share your thoughts : We’d love your feedback, scores, and questions! Please share them in the comments below.

Quizzes included in this guide are:

Recommended Resources

Recommended books and resources for your NCLEX success:

Disclosure: Included below are affiliate links from Amazon at no additional cost from you. We may earn a small commission from your purchase. For more information, check out our privacy policy .

Saunders Comprehensive Review for the NCLEX-RN Saunders Comprehensive Review for the NCLEX-RN Examination is often referred to as the best nursing exam review book ever. More than 5,700 practice questions are available in the text. Detailed test-taking strategies are provided for each question, with hints for analyzing and uncovering the correct answer option.

Strategies for Student Success on the Next Generation NCLEX® (NGN) Test Items Next Generation NCLEX®-style practice questions of all types are illustrated through stand-alone case studies and unfolding case studies. NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model (NCJMM) is included throughout with case scenarios that integrate the six clinical judgment cognitive skills.

Saunders Q & A Review for the NCLEX-RN® Examination This edition contains over 6,000 practice questions with each question containing a test-taking strategy and justifications for correct and incorrect answers to enhance review. Questions are organized according to the most recent NCLEX-RN test blueprint Client Needs and Integrated Processes. Questions are written at higher cognitive levels (applying, analyzing, synthesizing, evaluating, and creating) than those on the test itself.

NCLEX-RN Prep Plus by Kaplan The NCLEX-RN Prep Plus from Kaplan employs expert critical thinking techniques and targeted sample questions. This edition identifies seven types of NGN questions and explains in detail how to approach and answer each type. In addition, it provides 10 critical thinking pathways for analyzing exam questions.

Illustrated Study Guide for the NCLEX-RN® Exam The 10th edition of the Illustrated Study Guide for the NCLEX-RN Exam, 10th Edition. This study guide gives you a robust, visual, less-intimidating way to remember key facts. 2,500 review questions are now included on the Evolve companion website. 25 additional illustrations and mnemonics make the book more appealing than ever.

NCLEX RN Examination Prep Flashcards (2023 Edition) NCLEX RN Exam Review FlashCards Study Guide with Practice Test Questions [Full-Color Cards] from Test Prep Books. These flashcards are ready for use, allowing you to begin studying immediately. Each flash card is color-coded for easy subject identification.

Recommended Links

An investment in knowledge pays the best interest. Keep up the pace and continue learning with these practice quizzes:

- Nursing Test Bank: Free Practice Questions UPDATED ! Our most comprehenisve and updated nursing test bank that includes over 3,500 practice questions covering a wide range of nursing topics that are absolutely free!

- NCLEX Questions Nursing Test Bank and Review UPDATED! Over 1,000+ comprehensive NCLEX practice questions covering different nursing topics. We’ve made a significant effort to provide you with the most challenging questions along with insightful rationales for each question to reinforce learning.

11 thoughts on “Safety and Infection Control NCLEX Practice Quiz (75 Questions)”

In # 5 the correct answer should be letter B right?

Please review question #5 in Safety and Infection Control NCLEX Practice Exam (Set 2: 25 Questions) I chose the correct answer which was cool air dryer and it was marked wrong. But in the rationales it had it correct. Thank you

Corrected! Thank you for letting us know.

in the first set of questions #16 about doing CPR. your rational for the answer being what it is states “The nurse should use the heel of one hand at the center of the chest, then place the heel of the other hand on top of the first hand and lace fingers together and give 30 compressions that are about 1” to 1½” deep.”

this is actually incorrect. per the American Heart Association, depth of compression on children is about 2 inches. answer C is more correct than D. just think the answers should be worded better and rationale should be corrected in the depth.

Question 19 regarding the child in foster care. Foster Parents do not have permission to sign informed consent on invasive procedures and need Social Worker permission. Most often the hospital/clinic will request a signature from Social Worker. The child is in the CUSTODY of the state and the CARE of the foster parent.

Thank you very much. It is a great site, very helpful. Please kindly review the answers of the following: Safety and Infection Control NCLEX Practice Exam | Quiz #2: Question 25 The posted answers were not correspond to the Question #25. Thanks again.

Thanks Kumari, this has been fixed! :)

For Q#25 for Safety and Infection Control NCLEX Practice Exam Quiz #2, the rationale given does not match the question & its answer choices. Can you fix this, please?

Fixed. Thanks for letting us know! :)

the test was completed how i can get the certificate or anything elses to be done

Hello Piyanee, Thanks for completing the test! Just to let you know, currently, we don’t offer certificates for the quizzes on our platform. They’re mainly designed for self-assessment and practice. However, you’re welcome to try out other quizzes we have available to further strengthen your knowledge. It’s a great way to keep testing your skills and learning! If you have any other questions or need guidance on specific topics, feel free to reach out.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9.6 Preventing Infection

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

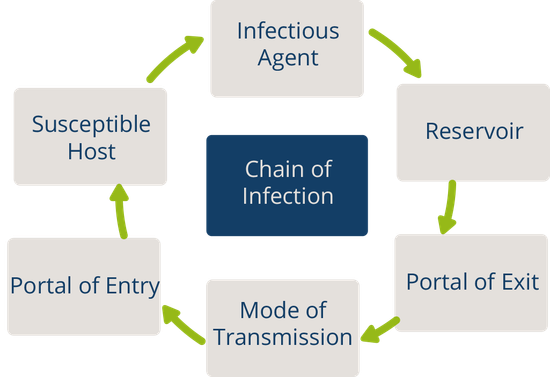

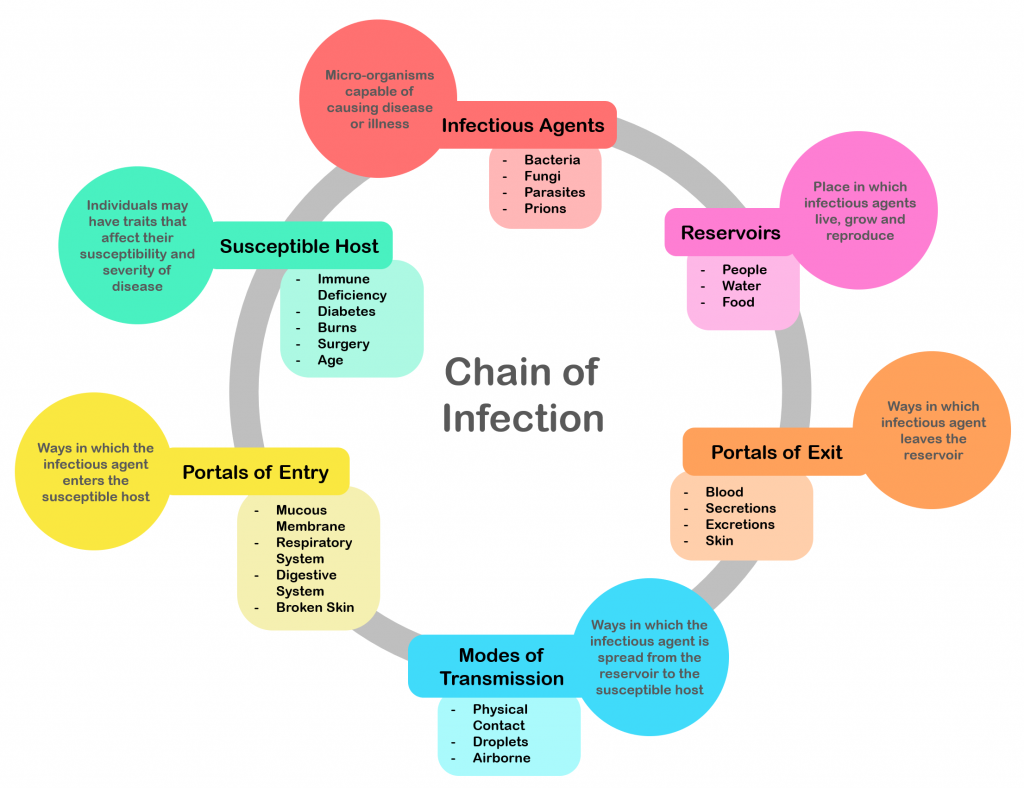

In addition to recognizing signs of infection and educating patients about the treatment of their infection, nurses also play an important role in preventing the spread of infection. A cyclic process known as the chain of infection describes the transmission of an infection. By implementing interventions to break one or more links in the chain of infection, the spread of infection can be stopped. See Figure 9.16 [1] for an illustration of the links within the chain of infection. These links are described as the following:

- Infectious Agent: A causative organism, such as bacteria, virus, fungi, parasite.

- Reservoir: A place where the organism grows, such as in blood, food, or a wound.

- Portal of Exit: The method by which the organism leaves the reservoir, such as through respiratory secretions, blood, urine, breast milk, or feces.

- Mode of Transmission: The vehicle by which the organism is transferred such as physical contact, inhalation, or injection. The most common vehicles are respiratory secretions spread by a cough, sneeze, or on the hands. A single sneeze can send thousands of virus particles into the air.

- Portal of Entry: The method by which the organism enters a new host, such as through mucous membranes or nonintact skin.

- Susceptible Host: The susceptible individual the organism has invaded. [2]

For a pathogen to continue to exist, it must put itself in a position to be transmitted to a new host, leaving the infected host through a portal of exit. Similar to portals of entry, the most common portals of exit include the skin and the respiratory, urogenital, and gastrointestinal tracts. Coughing and sneezing can expel thousands of pathogens from the respiratory tract into the environment. Other pathogens are expelled through feces, urine, semen, and vaginal secretions. Pathogens that rely on insects for transmission exit the body in the blood extracted by a biting insect. [3]

The pathogen enters a new individual via a portal of entry, such as mucous membranes or nonintact skin. If the individual has a weakened immune system or their natural defenses cannot fend off the pathogen, they become infected.

Interventions to Break the Chain of Infection

Infections can be stopped from spreading by interrupting this chain at any link. Chain links can be broken by disinfecting the environment, sterilizing medical instruments and equipment, covering coughs and sneezes, using good hand hygiene, implementing standard and transmission-based precautions, appropriately using personal protective equipment, encouraging patients to stay up-to-date on vaccines (including the flu shot), following safe injection practices, and promoting the optimal functioning of the natural immune system with good nutrition, rest, exercise, and stress management.

Disinfection and Sterilization

Disinfection and sterilization are used to kill microorganisms and remove harmful pathogens from the environment and equipment to decrease the chance of spreading infection. Disinfection is the removal of microorganisms. However, disinfection does not destroy all spores and viruses. Sterilization is a process used on equipment and the environment to destroy all pathogens, including spores and viruses. Sterilization methods include steam, boiling water, dry heat, radiation, and chemicals. Because of the harshness of these sterilization methods, skin can only be disinfected and not sterilized. [4]

Standard and Transmission-Based Precautions

To protect patients and health care workers from the spread of pathogens, the CDC has developed precautions to use during patient care that address portals of exit, methods of transmission, and portals of entry. These precautions include standard precautions and transmission-based precautions.

Standard Precautions

Standard precautions are used when caring for all patients to prevent healthcare-associated infections. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), standard precautions are the minimum infection prevention practices that apply to all patient care, regardless of suspected or confirmed infection status of the patient, in any setting where health care is delivered. These precautions are based on the principle that all blood, body fluids (except sweat), nonintact skin, and mucous membranes may contain transmissible infectious agents. These standards reduce the risk of exposure for the health care worker and protect the patient from potential transmission of infectious organisms. [5] See Figure 9.17 [6] for an image of some of the components of standard precautions.

Current standard precautions according to the CDC include the following:

- Appropriate hand hygiene

- Use of personal protective equipment (e.g., gloves, gowns, masks, eyewear) whenever infectious material exposure may occur

- Appropriate patient placement and care using transmission-based precautions when indicated

- Respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette

- Proper handling and cleaning of environment, equipment, and devices

- Safe handling of laundry

- Sharps safety (i.e., engineering and work practice controls)

- Aseptic technique for invasive nursing procedures such as parenteral medication administration [7]

![]“hand-disinfection-4954840_960_720.jpg” by KlausHausmann is licensed under CC0 Image showing hand sanitizer, gloves, and a surgical mask](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/31/2021/02/hand-sanitizer-1024x685.png)

Hand Hygiene

Hand hygiene, although simple, is still the best and most effective way to prevent the spread of infection. The 2021 National Patient Safety Goals from The Joint Commission encourages infection prevention strategy practices such as implementing the hand hygiene guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control. [8] Accepted methods for hand hygiene include using either soap and water or alcohol-based hand sanitizer. It is essential for all health care workers to use proper hand hygiene at the appropriate times, such as the following:

- Immediately before touching a patient

- Before performing an aseptic task or handling invasive devices

- Before moving from a soiled body site to a clean body site on a patient

- After touching a patient or their immediate environment

- After contact with blood, body fluids, or contaminated surfaces (with or without glove use)

- Immediately after glove removal [9]

Hand hygiene also includes health care workers keeping their nails short with tips less than 0.5 inches and no nail polish. Nails should be natural, and artificial nails or tips should not be worn. Artificial nails and chipped nail polish have been associated with a higher level of pathogens carried on the hands of the nurse despite hand hygiene. [10]

Respiratory Hygiene/Cough Etiquette

Respiratory hygiene is targeted at patients, accompanying family members and friends, and staff members with undiagnosed transmissible respiratory infections. It applies to any person with signs of illness, including cough, congestion, or increased production of respiratory secretions when entering a health care facility. The elements of respiratory hygiene include the following:

- Education of health care facility staff, patients, and visitors

- Posted signs, in language(s) appropriate to the population served, with instructions to patients and accompanying family members or friends

- Source control measures for a coughing person (e.g., covering the mouth/nose with a tissue when coughing and prompt disposal of used tissues, or applying surgical masks on the coughing person to contain secretions)

- Hand hygiene after contact with one’s respiratory secretions

- Spatial separation, ideally greater than 3 feet, of persons with respiratory infections in common waiting areas when possible [11]

Health care personnel are advised to wear a mask and use frequent hand hygiene when examining and caring for patients with signs and symptoms of a respiratory infection. Health care personnel who have a respiratory infection are advised to stay home or avoid direct patient contact, especially with high-risk patients. If this is not possible, then a mask should be worn while providing patient care. [12]

Personal Protective Equipment

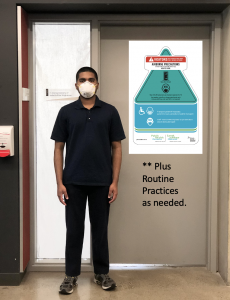

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) includes gloves, gowns, face shields, goggles, and masks used to prevent the spread of infection to and from patients and health care providers. See Figure 9.18 [13] for an image of a nurse wearing PPE. Depending upon the anticipated exposure and type of pathogen, PPE may include the use of gloves, a fluid-resistant gown, goggles or a face shield, and a mask or respirator. When used while caring for a patient with transmission-based precautions, PPE supplies are typically stored in an isolation cart next to the patient’s room.

Transmission-Based Precautions

In addition to standard precautions, transmission-based precautions are used for patients with documented or suspected infection of highly-transmissible pathogens, such as C. difficile (C-diff), Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), measles, and tuberculosis (TB). For patients with these types of pathogens, standard precautions are used along with specific transmission-based precautions. [14]

There are three categories of transmission-based precautions: contact precautions, droplet precautions, and airborne precautions. Transmission-based precautions are used when the route(s) of transmission of a specific disease are not completely interrupted using standard precautions alone.

Some diseases, such as tuberculosis, have multiple routes of transmission so more than one transmission-based precaution category must be implemented. See Table 9.6 outlining the categories of transmission precautions with associated PPE and other precautions. When possible, patients with transmission-based precautions should be placed in a single occupancy room with dedicated patient care equipment (e.g., blood pressure cuffs, stethoscope, and thermometer stay in the patient’s room). A card is posted outside the door alerting staff and visitors to required precautions before entering the room. See Figure 9.19 [15] for an example of signage used for a patient with contact precautions. Transport of the patient and unnecessary movement outside the patient room should be limited. When transmission-based precautions are implemented, it is also important for the nurse to make efforts to counteract possible adverse effects of these precautions on patients, such as anxiety, depression, perceptions of stigma, and reduced contact with clinical staff. [16]

Table 9.6 Transmission-Based Precautions [17]

Patient Transport

Several principles are used to guide transport of patients requiring transmission-based precautions. In the inpatient and residential settings, these principles include the following:

- Limit transport for essential purposes only, such as diagnostic and therapeutic procedures that cannot be performed in the patient’s room

- When transporting, use appropriate barriers on the patient consistent with the route and risk of transmission (e.g., mask, gown, covering the affected areas when infectious skin lesions or drainage is present)

- Notify health care personnel in the receiving area of the impending arrival of the patient and of the precautions necessary to prevent transmission [18]

Enteric Precautions

Enteric precautions are used when there is the presence, or suspected presence, of gastrointestinal pathogens such as Clostridium difficile (C-diff) or norovirus. These pathogens are present in feces, so health care workers should always wear a gown in the patient room to prevent inadvertent fecal contamination of their clothing from contact with contaminated surfaces.

In addition to contact precautions, enteric precautions include the following:

- Using only soap and water for hand hygiene. Do not use hand sanitizer because it is not effective against C-diff.

- Using a special disinfecting process. Special disinfecting should be used after patient discharge and includes disinfection of the mattress.

Reverse Isolation

Reverse isolation, also called neutropenic precautions, is used for patients who have compromised immune systems and low neutrophil levels. This type of isolation protects the patient from pathogens in their environment. In addition to using contact precautions to protect the patient, reverse isolation precautions include the following:

- Meticulous hand hygiene by all visitors, staff, and the patient

- Frequently monitoring for signs and symptoms of infection and sepsis

- Not allowing live plants, fresh flowers, fresh raw fruits or vegetables, sushi, deli foods, or cheese into the room due to bacteria and fungi

- Placement in a private room or a positive pressure room

- Limited transport and movement of the patient outside of the room

- Masking of the patient for transport with a surgical mask [19]

Psychological Effects of Isolation

Although the use of transmission-based precautions is needed to prevent the spread of infection, it is important for nurses to be aware of the potential psychological impact on the patient. Research has shown that isolation can cause negative impact on patient mental well-being and behavior, including higher scores for depression, anxiety, and anger among isolated patients. It has also been found that health care workers spend less time with patients in isolation, resulting in a negative impact on patient safety. [20]

Patient and family education at the time of instituting transmission-based precautions is a critical component of the process to reduce anxiety and distress. Patients often feel stigmatized when placed in isolation, so it is important for them to understand the rationale of the precautions to keep themselves and others free from the spread of disease. Preparing patients emotionally will also help decrease their anxiety and help them cope with isolation. [21] It is also important to provide distractions from boredom, such as music, television, video games, magazines, or books, as appropriate.

Aseptic and Sterile Techniques

In addition to using standard precautions and transmission-based precautions, aseptic technique (also called medical asepsis) is used to prevent the transfer of microorganisms from one person or object to another during a medical procedure. For example, a nurse administering parenteral medication or performing urinary catheterization uses aseptic technique. When performed properly, aseptic technique prevents contamination and transfer of pathogens to the patient from caregiver hands, surfaces, and equipment during routine care or procedures. It is important to remember that potentially infectious microorganisms can be present in the environment, on instruments, in liquids, on skin surfaces, or within a wound. [22]

There is often misunderstanding between the terms aseptic technique and sterile technique in the health care setting. Both asepsis and sterility are closely related with the shared concept being the removal of harmful microorganisms that can cause infection. In the most simplistic terms, aseptic technique involves creating a protective barrier to prevent the spread of pathogens, whereas sterile technique is a purposeful attack on microorganisms. Sterile technique (also called surgical asepsis) seeks to eliminate every potential microorganism in and around a sterile field while also maintaining objects as free from microorganisms as possible. Sterile fields are implemented during surgery, as well as during nursing procedures such as the insertion of a urinary catheter, changing dressings on open wounds, and performing central line care. See Figure 9.20 [23] for an image of a sterile field during surgery. Sterile technique requires a combination of meticulous hand washing, creating and maintaining a sterile field, using long-lasting antimicrobial cleansing agents such as Betadine, donning sterile gloves, and using sterile devices and instruments. [24]

Read additional information about aseptic and sterile technique in the “ Aseptic Technique ” in Open RN Nursing Skills .

Read a continuing education article about Sterile Technique and surgical scrubbing.

Other Hygienic Patient Care Interventions

In addition to implementing standard and transmission-based precautions and utilizing aseptic and sterile technique when performing procedures, nurses implement many interventions to place a patient in the best health possible to prevent an infection or treat infection. These interventions include actions like encouraging rest and good nutrition, teaching stress management, providing good oral care, encouraging daily bathing, and changing linens. It is also important to consider how gripper socks, mobile devices, and improper glove usage can contribute to the transmission of pathogens.

Patient hygiene is important in the prevention and spread of infection. Although oral care may be given a low priority, research has found that poor oral care is associated with the spread of infection, poor health outcomes, and poor nutrition. Oral care should be performed in the morning, after meals, and before bed. [25]

Daily Bathing

Daily bathing is another intervention that may be viewed as time-consuming and receive low priority, but it can have a powerful impact on decreasing the spread of infection. Studies have shown a significant decrease in healthcare-associated infections with daily bathing using chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) wipes or solution. The use of traditional soap and water baths do not reduce infection rates as significantly as CHG products, and wash basins have also been shown to be a reservoir for pathogens. [26]

Changing bed linens, towels, and a gown regularly eliminates potential reservoirs of bacteria. Fresh linens also promote patient comfort.

Gripper Socks

Have you ever thought about what happens to the bed linens when a patient returns from a walk in the hallway with gripper socks and gets back into bed with these socks? Research demonstrates that pathogens from the floor are transferred to the patient bed linens from the gripper socks. Nurses should remove gripper socks that were used for walking before patients climb into bed. They should also throw the socks away when the patient is discharged instead of sending them home. [27]

Cellular Phones and Mobile Devices

Research has shown that cell phones and mobile devices carry many pathogens and are dirtier than a toilet seat or the bottom of a shoe. Patients, staff, and visitors routinely bring these mobile devices into health care facilities, which can cause the spread of disease. Nurses should frequently wipe mobile devices with disinfectant. They should encourage patients and visitors to disinfect phones frequently and avoid touching the face after having touched a mobile device. [28]

Although gloves are used to prevent the spread of infection, they can also contribute to the spread of infection if used improperly. For example, research has shown that hand hygiene opportunities are being missed because of the overuse of gloves. For example, a nurse may don gloves to suction a patient but neglect to remove them and perform hand hygiene before performing the next procedure on the same patient. This can potentially cause the spread of secondary infection. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that gloves should be worn when there is an expected risk of exposure to blood or body fluids or to protect the hands from chemicals and hazardous drugs, but hand hygiene is the best method of disease prevention and is preferred over wearing gloves when the exposure risk is minimal. Nurses have the perception that wearing gloves provides extra protection and cleanliness. However, the opposite is true. Nonsterile gloves have a high incidence of contamination with a range of bacteria, which means that a gloved hand is dirtier than a washed hand. Research has shown that nearly 40% of the times that gloves are used in patient care, there is cross contamination. The most striking example of cross contamination includes situations when gloves are used for toileting a patient and not being removed before touching other surfaces or the patient. [29] , [30] , [31]

Glove-related contact dermatitis has also become an important issue in recent years as more and more nurses are experiencing damage to the hands. Contact dermatitis can develop from repeated use of gloves and develops as dry, itchy, irritated areas on the skin of the hands. See Figure 9.21 [32] for an image of contact dermatitis from gloves. Because the skin is the first line of defense in preventing pathogens from entering the body, maintaining intact skin is very important to prevent nurses from exposure to pathogens.

- “ Chain_of_Infection.png ” by Genieieiop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012, May 18). Lesson 1: Introduction to epidemiology. https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dsepd/ss1978/lesson1/section10.html ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, May 24). Disinfection and sterilization . https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/disinfection/index.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, January 26). Standard precautions for all patient care . https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/standard-precautions.html ↵

- “ hand-disinfection-4954840_960_720.jpg ” by KlausHausmann is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, April 29). Hand hygiene in healthcare settings . https://www.cdc.gov/handhygiene/ ↵

- Blackburn, L., Acree, K., Bartley, J., DiGiannantoni, E., Renner, E., & Sinnott, L. T. (2020). Microbial growth on the nails of direct patient care nurses wearing nail polish. Nursing Oncology Forum, 47 (2), 155-164. https://doi.org/10.1188/20.onf.155-164 ↵

- “ U.S. Navy Doctors, Nurses and Corpsmen Treat COVID Patients in the ICU Aboard USNS Comfort (49825651378).jpg ” by Navy Medicine is licensed under CC0 . ↵

- Siegel, J. D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L., & Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. (2019, July 22). 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings . https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/isolation/index.html ↵

- “ Contact_Precautions_poster.pdf ” by U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the Public Domain ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). What you need to know: Neutropenia and risk for infection. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/preventinfections/pdf/neutropenia.pdf ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020, January 15). Health care-associated infections. https://health.gov/our-work/health-care-quality/health-care-associated-infections ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, August 10). Glossary of terms for infection prevention and control in dental settings. https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/glossary.htm ↵

- " 226589236-huge.jpg " by TORWAISTUDIO is used under license from Shutterstock.com ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Tennant and Rivers and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . ↵

- Ackley, B., Ladwig, G., Makic, M. B., Martinez-Kratz, M., & Zanotti, M. (2020). Nursing diagnosis handbook: An evidence-based guide to planning care (12th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 546-552, 828-832. ↵

- Salamone, K., Yacoub, E., Mahoney, A. M., & Edward, K. L. (2013). Oral care of hospitalised older patients in the acute medical setting. Nursing Research and Practice, 2013 , 827670. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/827670 ↵

- Welle, M. K., Bliha, M., DeLuca, J., Frauhiger, A., & Lamichhane-Khadka, R. Bacteria on the soles of patient-issued nonskid slipper socks: An overlooked pathogen spread threat? Orthopedic Nursing, 38 (1), 33-40. https://doi.org/10.1097/nor.0000000000000516 ↵

- Morubagal, R. R., Shivappa, S. G., Mahale, R. P., & Neelambike, S. M. (2017). Study of bacterial flora associated with mobile phones of healthcare workers and non-healthcare workers. Iranian Journal of Microbiology, 9 (3), 143–151. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5719508/ ↵

- Burdsall, D. P., Gardner, S. E., Cox, T., Schweizer, M., Culp, K. R., Steelman, V. M., & Herwaldt, L. A. (2017). Exploring inappropriate certified nursing assistant glove use in long-term care. American Journal of Infection Control, 45 (9), 940-945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2017.02.017 ↵

- Jain, S., Clezy, K., & McLaws, M. L. Glove: Use for safety or overuse? American Journal of Infection Control, 45 (12), 1407-1410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2017.08.029 ↵

- “ Dermatitis2015.jpg ” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

Removal of organisms from inanimate objects and surfaces.

A process used to destroy all pathogens from inanimate objects, including spores and viruses.

The minimum infection prevention practices that apply to all patient care, regardless of suspected or confirmed infection status of the patient, in any setting where healthcare is delivered.

Gloves, gowns, face shields, goggles, and masks used to prevent the spread of infection to and from patients and health care providers.

The purposeful reduction of pathogens to prevent the transfer of microorganisms from one person or object to another during a medical procedure.

A process, also called surgical asepsis, used to eliminate every potential microorganism in and around a sterile field while also maintaining objects as free from microorganisms as possible.

Nursing Fundamentals Copyright © by Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the hospitals and research participants involved in this learning report and the research team: Professor Alison Holmes, Professor Mary Dixon-Woods, Dr Raheelah Ahmad, Dr Elizabeth Brewster, Dr Enrique Castro-Sánchez, Dr Federica Secci and Dr Walter Zingg. With input from Susan Burnett, Professor Ewan Ferlie, Tracey Galletly, Fran Husson, Claire Kilpatrick, Dr Reda Lebcir and the Patients Association.

Alison Holmes Professor of Infectious Diseases, Imperial College London [email protected]

It is with pleasure that I write the foreword for this concise learning report on infection prevention and control (IPC), which builds on the large body of work conducted by researchers at Imperial College London and the University of Leicester. The Health Foundation has brought together a strong multidisciplinary team to review activity and interventions to reduce health care associated infections (HCAI) in English acute care organisations over the last 15 years with the aim of ensuring that key learning can be collectively reflected upon and to shape further national and local activity.

Continuous learning is a key Health Foundation principle and is particularly supported by one of the overriding lessons highlighted in this report: namely, the importance of ensuring that any major interventions, such as local antimicrobial resistance (AMR) action plans, are supported by a planned analysis which should examine impact and implementation as well as cost-effectiveness. Such an understanding would form a solid basis for informing further interventions. There has been much interest internationally in some of the UK’s significant successes in HCAI reduction, but there is little material available for shared learning in the absence of adequate studies on national interventions.

The key lessons in this report are being well heeded and are being discussed with relevant partners to ensure actions are put in place to address them. These actions should build upon this learning report, recognising that whilst IPC behaviours of those working at the front line are critical, they must also be actively supported and positively reinforced by a hospital environment that supports best IPC practice and minimises risk. Several of the findings and key lessons particularly in relation to the need to address AMR are also reinforced by the Chief Medical Officer’s report UK 5-year Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Strategy (2013–2018). I am also pleased to acknowledge that the Health Foundation is becoming involved in improving antibiotic prescribing behaviours, which is a key aspect of IPC.

I am delighted that the views and input from our patients and the public have been particularly invited and explored in this report and that there will be ongoing work to better understand public and patient engagement and involvement.

Even though the scope of this commissioned report was confined to acute care and to HCAI prevention, the authors make two fundamental recommendations that should be considered by policymakers. These are, firstly, that addressing the threat of AMR must be more effectively integrated with the delivery of strong IPC and, secondly, that tackling any transmissible organism must be addressed comprehensively across the whole patient journey. Organisms do not respect boundaries between community, primary and secondary care, so a whole health care economy approach is vital.

As Chair of the Department of Health advisory committee on antimicrobial resistance and healthcare associated infection (ARHAI), I fully endorse the lessons within this learning report. I am delighted that ARHAI will discuss actions to address the report’s findings with the Health Foundation in the coming year.

Professor Mike Sharland

Chair of the Department of Health advisory committee on antimicrobial resistance and healthcare associated infection (ARHAI)

Glossary of common abbreviations

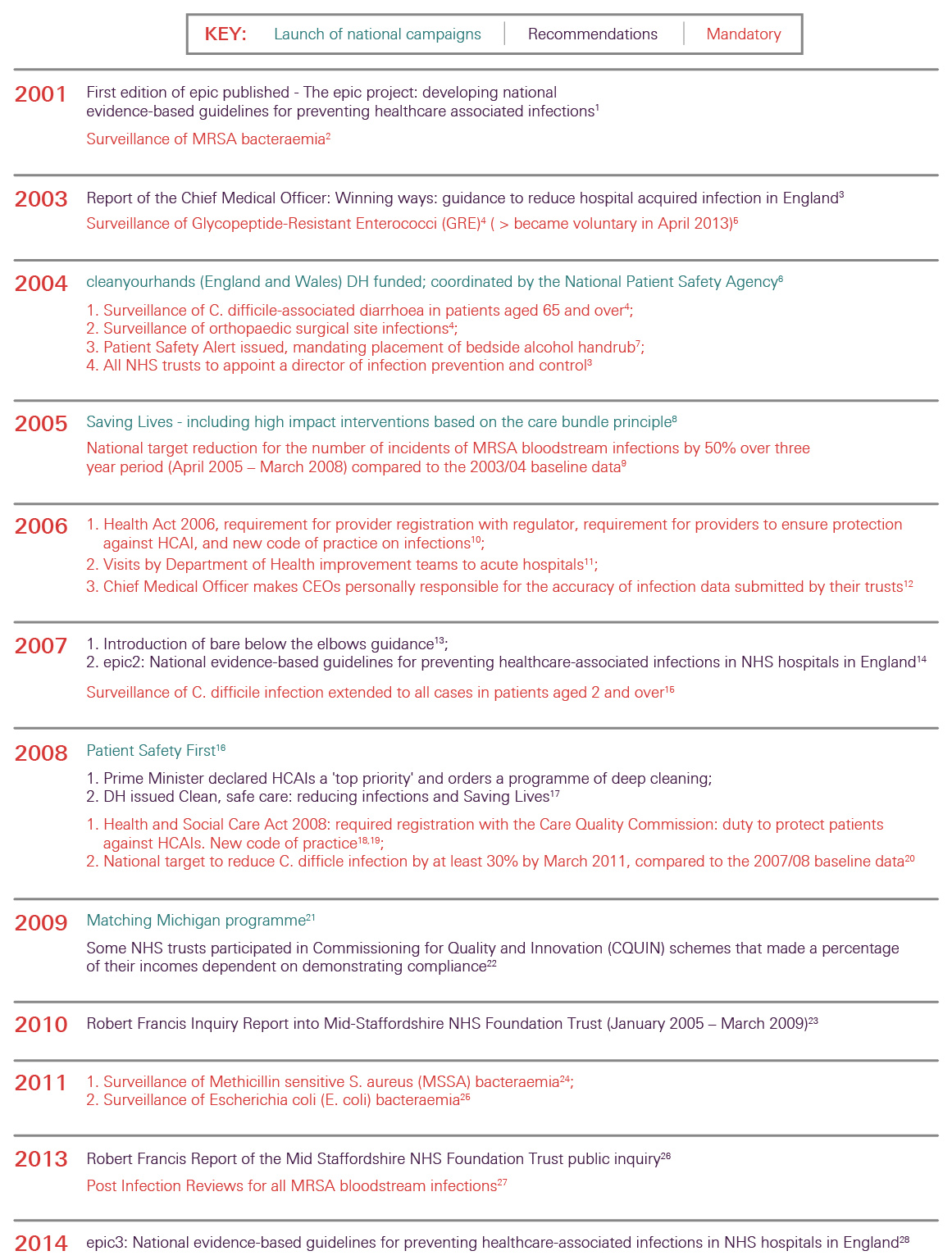

Introduction.

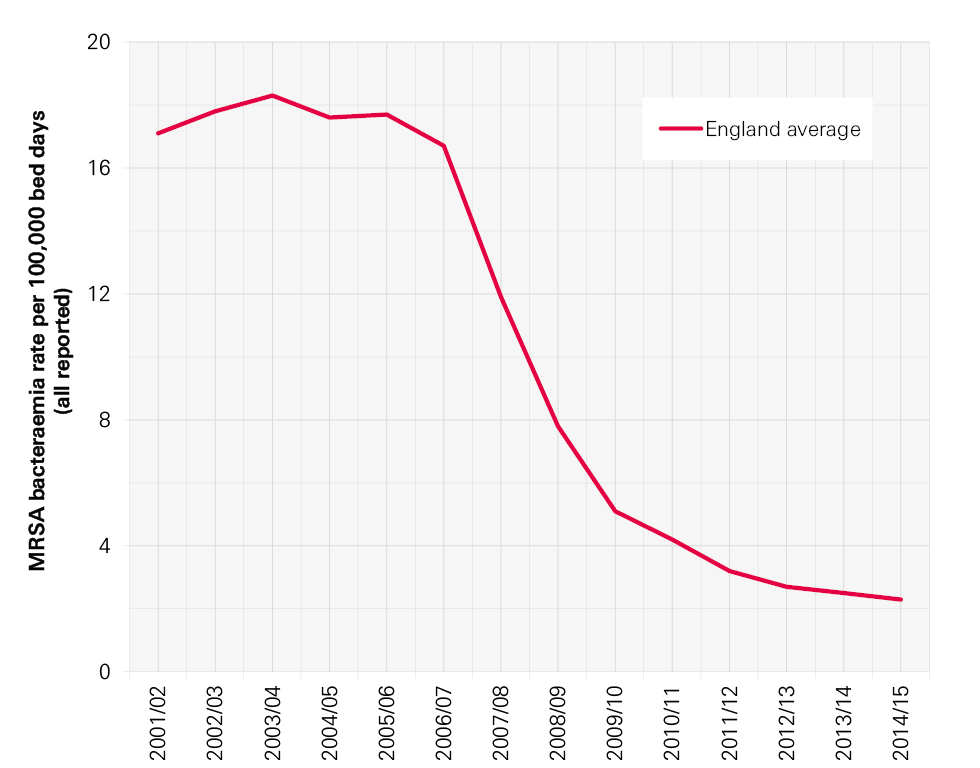

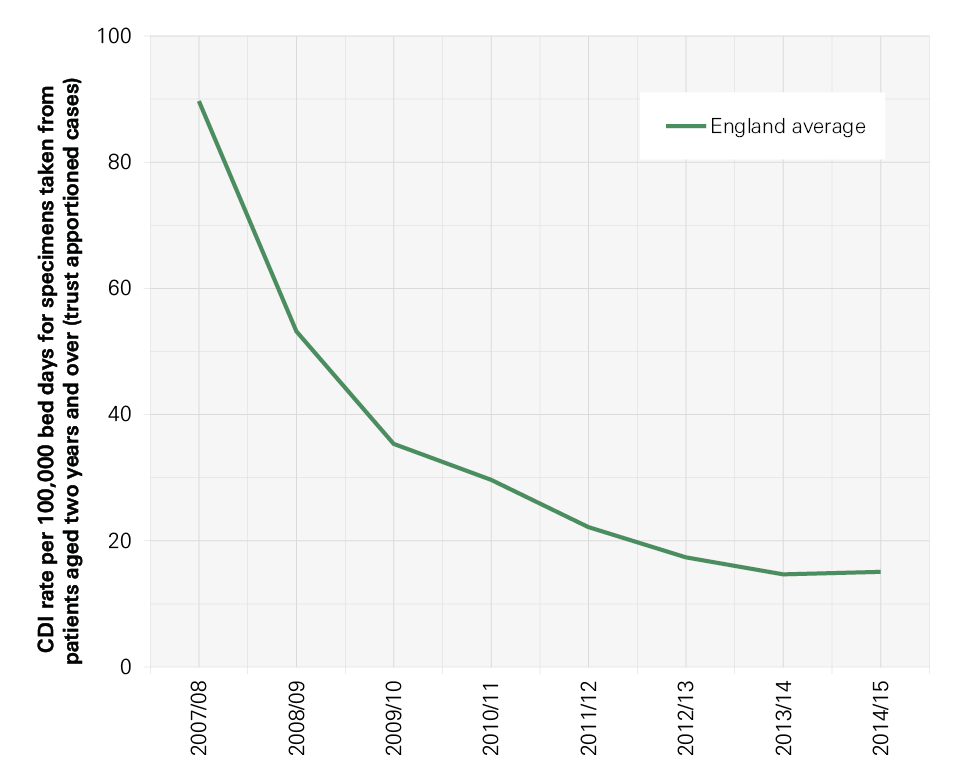

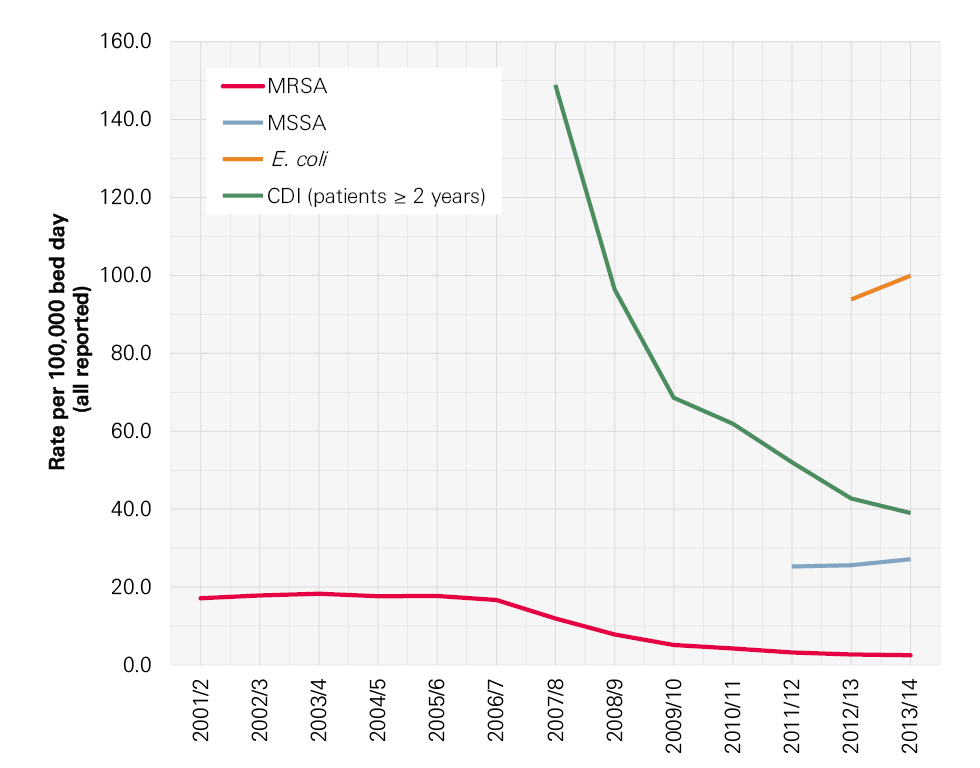

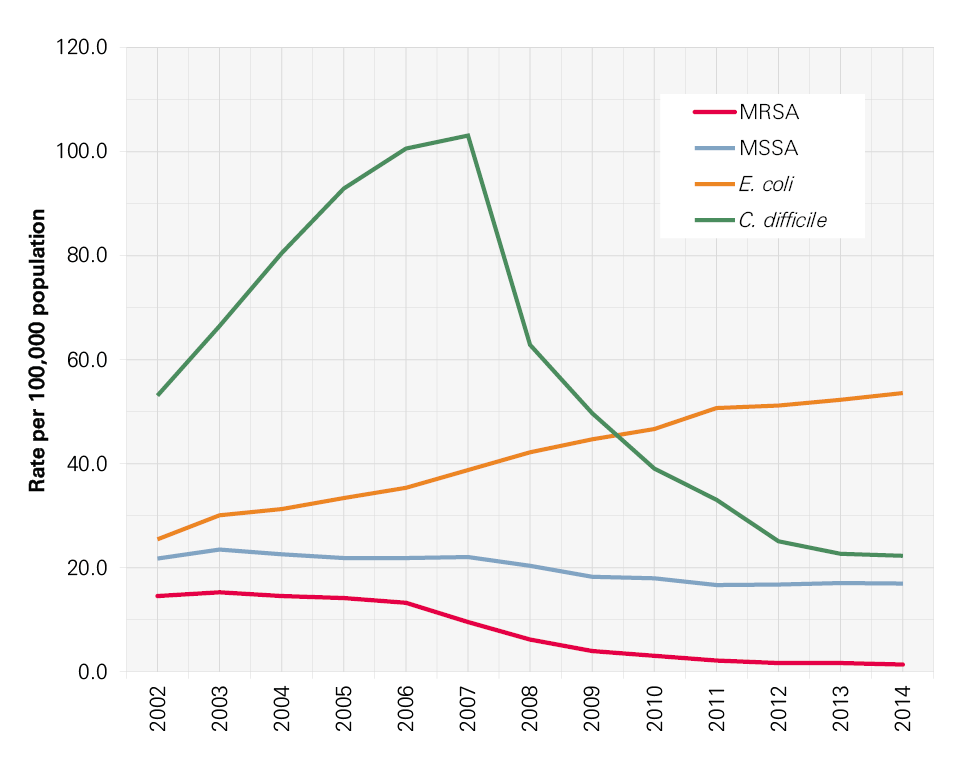

Infection control has been high on the political agenda and on the agenda of the NHS in England for the last 15 years. During this time there have been many successes, not least the reduction in MRSA bloodstream infections (BSIs) and cases of Clostridium difficile infection. Though these successes should be celebrated, it is important not to become complacent. Other health care associated infections (HCAIs) that have not been monitored as rigorously are growing in incidence. New infections, including the growing number of more resistant strains of bacteria, are in danger of spreading. As a result, infection control needs to remain central to the work of the NHS and it is essential to continue building on the achievements of recent years to reduce mortality, morbidity and health care costs.

This report considers what has been learned from the infection prevention and control (IPC) work carried out over the last 15 years in hospitals in England and looks at how these lessons should be applied in future. Should the NHS continue to respond in the same way to infection threats or should new approaches be adopted? Of all the interventions made during this period, what has worked best? Is it even possible to tell? How have all the infection control procedures and practices impacted on the front line in clinical care and on service users?

The lessons the report sets out are drawn from the findings of a large research study that identified and consolidated published evidence from the UK about national IPC initiatives and interventions and synthesised this with findings from qualitative case studies in two large NHS hospitals, including the perspectives of service users recorded during consultation events.

The report begins with an overview of HCAIs, especially those linked to hospitals. With this background, the landscape of infection control in English hospitals is set out, including recent successes and the challenges ahead. The report goes on to draw out lessons to help inform future work to maintain hospitals as safe places.

What are health care associated infections?

Health care associated infections are infections that develop as a direct result of medical or surgical treatment or contact in a health care setting. , They can occur in hospitals and in health or social care settings in the community and can affect both patients and health care workers. An infection occurs when a germ (an organism such as a bacterium, virus or fungus) enters the body and attacks or causes damage to it. Every individual is covered with bacteria on their body and also carries trillions of them in their gut. Any medical or surgical procedure that breaks the skin or any mucous membrane, introduces any foreign material or reduces immunity creates a risk of infection. Some infections can enter the bloodstream and become generalised throughout the body. This is known as a bacteraemia or bloodstream infection (BSI).

In this report we focus particularly on those infections that arise during hospital care. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) BSIs and C. difficile associated diarrhoea ( C. difficile infection) are two well-known HCAIs that have been the focus of attention in England, but there are many more. MRSA BSIs are particularly associated with intravenous devices (eg central lines) and C. difficile with antibiotic exposure. Hand hygiene, environmental hygiene, the capacity to isolate patients and assuring optimal antibiotic prescribing are all critical aspects of prevention of both.

Other HCAIs include BSIs caused by other organisms, urinary tract infections related to urinary catheters (CAUTIs), respiratory tract infections such as pneumonia related to being ventilated (VAP), or wound or surgical site infections (SSIs). Microorganisms come from droplets that are sneezed or coughed (eg flu), from air (eg tuberculosis), or from water (eg legionnaires’ disease); they are passed within the hospital or they can come in from the community (eg norovirus). Germs causing HCAIs may have different modes of transmission and different sources, and patients may have different profiles of risk factors making them more vulnerable to an HCAI, but some core infection prevention principles remain the same.