- Our Mission

Explaining the Symbiotic Relationship Between Reading and Writing

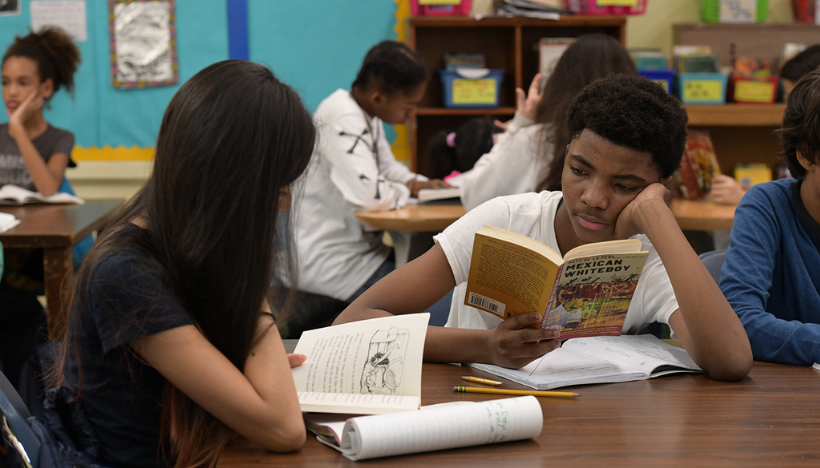

Students who understand how reading relates to writing and vice versa can develop into better writers.

For elementary school teachers, the saying is, students learn to read and then read to learn. At the middle and high school levels, teachers may experience the relationship of first writing to read, and then reading to write. Although this expression is not so common, there are resources that point to such a relationship, including ” Writing to Read: Evidence for How Writing Can Improve Reading ” or books such as The Write to Read .

While the relationship of “writing to read” and “reading to write” represents a symbiotic one, there is a distinct difference that may help us better understand what we are teaching students.

Writing to Read

When a student is writing to read, they are using writing as a tool to truly understand the reading. Writing to read is driven by the text the student is studying.

Examples of writing to read

- Write a high-level summary to remember and consolidate the content of the reading.

- Write a claim about the reading, and use three pieces of evidence to support it.

- Respond to open-ended questions about the reading as a way to connect to or analyze the text.

- Write an essay on a book to illuminate a particular theme or provide evidence to trace tonal shifts in the piece.

- Write about the content of a particular text or texts to understand, analyze, or evaluate the text(s) at a deeper level.

- Annotate during reading to capture important terms, ideas, or content.

- Fill in graphic organizers or take notes to track the reading.

- Write in response to a prompt.

- Write an essay about a particular literary device or critical feature of the text(s).

Reading to Write

When a student is reading to write, they are using reading as a tool to improve their writing. Reading to write occurs when students first learn how to imitate their favorite authors, historians, scientists, or researchers. This is the deliberate use of mentor texts to mold a student’s writing ability.

Examples of reading to write

- Read memoirs or personal essays to prepare to write a college essay.

- Read several articles from a particular journal or newspaper to increase knowledge of stylistic expectations in preparation to write a piece for publication.

- To help relieve writer’s block, use reading to think about different ways to write.

- Read widely on a topic to consider one’s own writing approach and background knowledge.

- Review multiple texts to write for a particular purpose or on a specific topic.

- Read a lot to write more by picking out the ideas that spark thinking.

- Maintain an annotated bibliography of mentor texts that serve as a writing coach.

Moving Toward Reading to Write

The developmental progression from reader to writer is specific to each student’s experience; however, we do know that in order to strengthen their ability to write, students must continue to read more.

Reading feeds writing. When writing dries up or stalls, the best way to revitalize it is to feed your brain with more reading. Reading may be compared to eating the nutrients we need for the energy to write. Reading feeds the writer with ideas for structure, rich language, literary moves, and compelling ways to illuminate a writer’s purpose.

After filling our brain with reading, turning back to writing typically gives one the energy needed to continue. This is one reason why writing to read is so important early on, then gradually becomes just as important as reading to write. As students develop confidence and competence as readers as the content and vocabulary become much more sophisticated, they build capacity to see the text as both a reader and a writer.

There are potential benefits of looking at the writing-to-read and reading-to-write relationship as teachers continue to challenge themselves with the best way to teach students how to write. Many times at the middle and high school levels, experience with writing to read is the dominant one. If this is the case, it might be a good time to rethink instructional goals and associated assessments.

Here are some practical suggestions for how to weave the two more seamlessly so that students grow into stronger writers.

Assignments that Weave in Reading to Write

After students complete a writing-to-read activity, have them complete a second activity that asks them to use the same text as a reading-to-write activity. (Models and research on how to use mentor texts can be found in books by Allison Marchetti and Rebekah O’Dell .) The second activity may be practice captured in the writer’s notebook for the student to use as a resource to support their writing throughout the year. Some examples of such activities may include the following:

- Write a high-level summary of the text, then pick sentences from the text that use punctuation or sentence structure in a way that is powerful.

- Write a claim along with supporting evidence, then look at the text to pick out the best use of transitions.

- Annotate a book to trace character development, then pull out parts of the book that were written with vivid, descriptive language.

- Write an essay on the theme of a book, then write a reflection on the author’s craft.

- Write a response to reading to analyze the author’s line of reasoning, then break down the formal structure of the argument.

After high school, students contribute even more to society, so they need to know how to cogently express their thinking to others. Empowering students as writers requires practice, and it’s important that students understand how writing to read and reading to write serve them in markedly different ways.

Reading Worksheets, Spelling, Grammar, Comprehension, Lesson Plans

The Relationship Between Reading and Writing

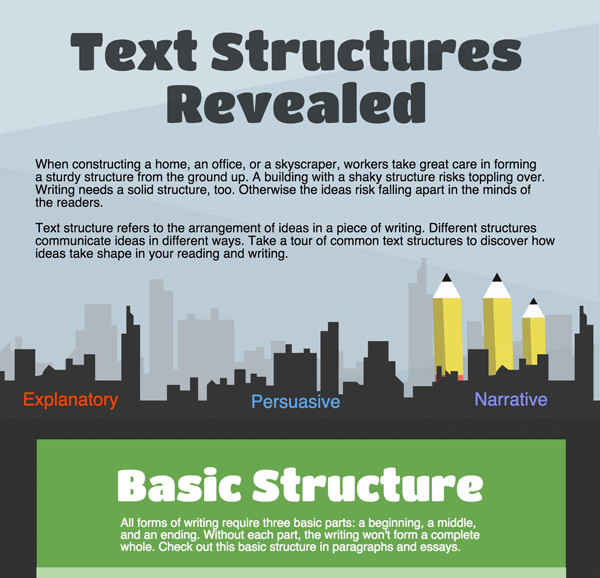

F or many years reading and writing were (and sometimes still are) taught separately. Though the two have almost always been taught by the same person (the English/Language Arts teacher) during the Language Arts period or block, educators rarely made explicit connections between the two for their students. Over the last ten years research has shown that reading and writing are more interdependent than we thought. The relationship between reading and writing is a bit like that of the chicken and egg. Which came first is not as important as the fact that without one the other cannot exist. A child’s literacy development is dependent on this interconnection between reading and writing.

Basically put: reading affects writing and writing affects reading. According to recommendations from the major English/Language Arts professional organizations, reading instruction is most effective when intertwined with writing instruction and vice versa. Research has found that when children read extensively they become better writers. Reading a variety of genres helps children learn text structures and language that they can then transfer to their own writing. In addition, reading provides young people with prior knowledge that they can use in their stories. One of the primary reasons that we read is to learn. Especially while we are still in school, a major portion of what we know comes from the texts we read. Since writing is the act of transmitting knowledge in print, we must have information to share before we can write it. Therefore reading plays a major role in writing.

At the same time practice in writing helps children build their reading skills. This is especially true for younger children who are working to develop phonemic awareness and phonics skills. Phonemic awareness (the understanding that words are developed from sound “chunks”) develops as children read and write new words. Similarly, phonics skills or the ability to link sounds together to construct words are reinforced when children read and write the same words. For older children practice in the process of writing their own texts helps them analyze the pieces that they read. They can apply their knowledge about the ways that they chose to use particular language, text structure or content to better understand a professional author’s construction of his or her texts.

Harnessing the Reading-Writing Relationship to Help Children Learn

Simply knowing that reading and writing are intimately connected processes isn’t enough. In order to help children develop these two essential skills, parents and teachers need to apply this knowledge when working with them. Here are a few strategies for using reading and writing to reinforce development of literacy skills.

Genre Study

One of the most effective ways to use the relationship between reading and writing to foster literacy development is by immersing children in a specific genre. Parents and teachers should identify a genre that is essential to a grade level’s curriculum or is of particular interest to a child or group of children. They should then study this genre with the child(ren) from the reading and writing perspectives. Children should read and discuss with adults high quality examples of works written in the genre focusing on its structure and language as well as other basic reading skills including phonics and comprehension. Once children have studied the genre to identify its essential elements, they should be given opportunities to write in the genre. As they are writing, adults should help them apply what they have learned from reading genre specific texts to guide their composition. This process should be recursive to allow children to repeatedly move between reading and writing in the genre. In the end children will not only have a solid and rich knowledge of the genre, but will also have strengthened their general reading and writing skills.

Reading to Develop Specific Writing Skills

Parents and teachers do not have to engage in an extensive genre study to foster their children’s reading and writing abilities. Texts can be used on limited basis to help children learn and strengthen specific writing skills. Parents and teachers should first identify writing skills that a particular child or group of children need support in developing. For example, many students in a seventh grade class might have difficulty writing attention getting introductions in their essays. One of the most effective ways to help children build specific writing skills is to show and discuss with them models that successfully demonstrate the skill. Adults should select a number of texts where the authors “nail” the area that they want to help their children grow in. For our sample seventh graders we’d want to find several pieces of writing with strong, engaging introductions and read and analyze these with the students. Once children have explored effective models of the skill, they should be given opportunities to practice it. They can either write new pieces or revise previous pieces of writing emulating the authors’ techniques.

Integrating “Sound” Instruction in Reading and Writing

Phonemic awareness and phonics are two of the pillars of reading. Without understanding the connection between sounds and letters, a person cannot read. The connection between reading and writing can help solidify these skills in young readers. Parents and teachers should help children “sound out” words in both their reading and writing. When a child comes to a word in their reading that is unfamiliar, the adult(s) working with her can model or guide her in sounding out the word using knowledge of phonemes (sound “chunks”). Similarly, if a child wants to write a new word the adult(s) can use the same technique to help her choose which letters to write. If the child is younger, accurate spelling is not as important as an understanding of the connection between particular sounds and letters. Therefore helping the child pick letters that approximate the spelling is more appropriate than providing him with the actual spelling. If the child is older and has an understanding of some of the unique variations in the English language (such as silent “e”), the parent or teacher should encourage him to use that knowledge to come up with the spelling of the word.

Choice in Reading and Writing

Another effective method for using the relationship between reading and writing to foster literacy development is simply giving children the choice in their reading and writing experiences. We learn best when we are motivated. If children are always told exactly what to read and what to write, they will eventually either come to see reading and writing as impersonal events or will “shut down”. Often in classrooms, teachers allow children to select their own books to read during independent reading time, but they rarely give them the opportunity to pick their own writing topics. In order to encourage ownership over their reading and writing, children should be given chances to read and write what is interesting and important to them.

Talk About It!

While it may seem like common sense to adults that reading and writing have a lot to do with each other, the connection is not always as apparent to young people. Parents and teachers should explain how the two skills reinforce and strengthen each other. Young people (especially adolescents) often ask their parents and teachers, “Why do I have to learn this?” Here is a perfect opportunity to show the relationship between two essential academic and life skills.

- Career Center

The Relationship Between Writing and Reading

Lisa Fink 12.17.17 Writing

Professional Knowledge for the Teaching of Writing , written by a committee of the NCTE Executive Committee, pinpoints 10 key issues in the effective teaching of writing. Over the next few weeks, we will unpack each one. This week, we will look at:

“Writing and reading are related.”

Research has shown that when students receive writing instruction, their reading fluency and comprehension improve. NCTE provides many resources that emphasize the reading and writing connection.

The NCTE Policy Brief on Reading and Writing across the Curriculum states that “discipline-based instruction in reading and writing enhances student achievement in all subjects … Without strategies for reading course material and opportunities to write thoughtfully about it, students have difficulty mastering concepts. These literacy practices are firmly linked with both thinking and learning.”

Katie Van Sluys, in her book Becoming Writers in the Elementary Classroom: Visions and Decisions , shares ways in which young people have the opportunity to become competent, constantly growing writers who use writing to think, communicate, and pose as well as solve problems.

Nancy Patterson, in a Voices from the Middle article raises the point, “If the whole idea behind English language arts classes is to foster a love of reading and a thirst for human experience and ideas represented through text, then we have to think critically about not only the kinds of reading our students do, but also the kinds of writing they do.” Read more in “ Form and Artistry: The Reading/Writing Connection .”

“ A Snapshot of Writing Instruction in Middle Schools and High Schools ” by Applebee and Langer provides a detailed look at schools and data, interviews with teachers and administrators, and a national survey of teachers on the changes in the teaching of writing.

Bob Fecho, author of Writing in the Dialogical Classroom: Students and Teachers Responding to the Texts of Their Lives , argues that teachers need to develop writing experiences that are reflective across time in order to foster even deeper explorations of subject matter. He creates an ongoing conversation between classroom practice, theory, and research to show how each informs the others.

Designing Writing Assignments by Traci Gardner offers practical ways for teachers to develop assignments that will allow students to express their creativity and grow as writers and thinkers while still addressing the many demands of resource-stretched classrooms.

In Everyday Genres: Writing Assignments across the Disciplines , the author, Mary Soliday, calls on genre theory to analyze the common assignments given to writing students in the college classroom, and to investigate how new writers and expert readers respond to a variety of types of coursework in different fields.

How do you use the NCTE Professional Knowledge for the Teaching of Writing in your classroom?

The Reading and Writing Connection

November 15, 2018.

Reading and writing skills are the cornerstones of academic proficiency, and there are many cognitive processes that must be coordinated in order for students to access content and demonstrate mastery. Literacy experts believe that reading is developed through a series of skills that help us connect our speech sounds to letters, those letters to words, words to sentences and eventually paragraphs, essays, and whole books. These skills, according to Jean Chall’s long-standing theory, develop in a hierarchy. Writing development involves just as many coordinating skills. It requires students to use fine motor skills, basic and advanced reading skills, and study skills with the integration of many of the executive functions.

Literacy experts and relevant research suggest that reading and writing need to be taught simultaneously as there are many overlapping skills. According to Timothy Shanahan (2017), “about 70% of the variation in reading and writing abilities are shared.” Spelling and single-word reading rely on the same underlying knowledge, so instruction and practice in one should aid the development of the other. For instance, the ability to link sounds together to construct words is reinforced when students read and write the same words. Furthermore, writing instruction improves reading comprehension, and the teaching of writing skills, such as grammar and spelling lessons, reinforces reading skills. If educators teach and practice reading and writing skills in conjunction with one another, they provide students with increased meaningful exposure to language and literacy. This double instruction ensures automatization of targeted skills through practice and review, which is one of Landmark’s Six Teaching Principles .

Chall, J. S. (1983). Stages of reading development. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

How writing develops. Reading Rockets. (2013, November 7). Retrieved March 31, 2022, from https://www.readingrockets.org/article/how-writing-develops#:~:text=Young%20children%20move%20through%20a,become%20a%20reader%20and%20writer .

Shanahan, T. (2020, May 27). How should we combine reading and writing? Reading Rockets. Retrieved March 31, 2022, from https://www.readingrockets.org/blogs/shanahan-literacy/how-should-we-combine-reading-and-writing

Additional Resources

Resources Ehri, Linnea C. (1992). Reconceptualizing the development of sight word reading and its relationship to reading. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Graham, S. and Hebert, M.A. (2010). Writing to Read: Evidence for how writing can improve reading. A Carnegie Corporation Time to Act Report. Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education.

IDA. (2015). Starting with the Test: Teaching Writing to Enhance Reading Comprehension.

K12 Reader: Reading Instruction Resources. (2018). “The Relationship Between Reading and Writing.” Retrieved from: https://www.k12reader.com/the-relationship-between-reading-and-writing/

Matulis, Bev. (2007). Writing Intention: Prompting Professional Learning through Student work: Dancing with the Authors. p. 36-40.

Shanahan, Timothy. (2017). “How Should We Combine Reading and Writing?” Reading Rockets. Retrieved from: http://www.readingrockets.org/blogs/shanahan-literacy/how-should-we-combine-reading-and-writing

Woodson, Linda. (October 1979). A Handbook of Modern Rhetorical Terms. National Council of Teachers.

Strategies to Download

Recommended for you.

Nov 18, 2021

Supporting Students in Developing Automatic Word Recognition

Sep 1, 2023

Poetry in the Age of Science of Reading

Sep 8, 2021

Using a Decoding Toolkit to Develop a Common Language

Check out our blog.

Learn about our new updated blog format that will combine our monthly newsletter and Free Teaching Strategies into one resource!

- Career Center

- Digital Events

- Member Benefits

- Membership Types

- My Account & Profile

- Chapters & Affiliates

- Awards & Recognition

- Write or Review for ILA

- Volunteer & Lead

- Children's Rights to Read

- Position Statements

- Literacy Glossary

- Literacy Today Magazine

- Literacy Now Blog

- Resource Collections

- Resources by Topic

- School-Based Solutions

- ILA Digital Events

- In-Person Events

- Our Mission

- Our Leadership

- Press & Media

Literacy Now

- ILA Network

- Conferences & Events

- Literacy Leadership

- Teaching With Tech

- Purposeful Tech

- Book Reviews

- 5 Questions With...

- Anita's Picks

- Check It Out

- Teaching Tips

- In Other Words

- Putting Books to Work

- Tales Out of School

- Scintillating Studies

Writing to Read: Evidence for How Writing Can Improve Reading

Graham, S., and Hebert, M. A. (2010). Writing to read: Evidence for how writing can improve reading. A Carnegie Corporation Time to Act Report. Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education.

“The evidence is clear: writing can be a vehicle for improving reading” (p. 6).

Ten years ago The National Commission on Writing in America’s Schools and Colleges deemed writing the “neglected ‘R’” and called for a “writing revolution” that included doubling the amount of time students spend writing. In the years following, extensive reports such as Reading Next (Biancarosa & Snow, 2006) and Writing Next (Graham & Perin, 2007) supported the idea that writing is a powerful tool for improving reading, thinking, and learning. Now as much of the country implements the Common Core State Standards, there is a renewed push for more and better writing. As educators try to determine how to improve student learning and include more writing within the same time limits, it is important to revisit Steve Graham and Michael Hebert’s (2010) Writing to Read , which gives strong evidence that writing, an essential skill itself, also improves reading comprehension.

For decades researchers have emphasized the strong connection between reading and writing, both in theory and in practice. Multiple studies have demonstrated that writing can improve comprehension. What has been less clear is what particular writing practices research supports as being effective at improving students’ reading. To determine those practices, Graham and Hebert (2010) undertook an in-depth meta-analysis of experimental and quasi-experimental studies that examined the effectiveness of writing practices on improving students’ reading in grades 1 -12. They acknowledge the limitations of excluding other forms of research and recognize the significant contributions of that research; at the same time, they share that completing this sort of meta-analysis allowed them to focus on studies where cause-and-effect could be inferred and effect sizes calculated. Their meta-analysis generated three recommendations:

- Have students write about the texts they read. “Writing about a text proved to be better than just reading it, reading and rereading it, reading and studying it, reading and discussing it, and receiving reading instruction” (p. 14). Specific types of writing about reading that had statistically significant effect sizes included responding to a text through writing personal reactions or analyses/interpretations of the text, writing summaries of a text, taking notes on a text, and creating and/or answering questions about a text in writing. The benefits of these types of writing were stronger, particularly for lower-achieving students, when they were tied with explicit instruction on how to write.

- Teach students the writing skills and processes that go into creating texts. Teaching students about writing process, text structures, paragraph or sentence construction, and other writing skills improves reading comprehension; teaching spelling and sentence construction skills improve fluency; and teaching spelling skills improves word reading skills.

- Increase how much students write. An increase in how often students write improves students’ reading comprehension. Graham and Hebert recommend more writing across the curriculum, as well as at home to achieve more time spent writing.

What may be most important in all of Graham and Hebert’s findings is that infrequent writing and lack of explicit writing instruction minimize any sort of effect on reading from the writing practices they recommend. Their report also supports earlier calls for emphasizing writing in the classroom and across content areas. Writing is a critical skill, important in its own right; given the evidence that consistent writing time and instruction not only improves writing but also reading, gives us an even more compelling case for finding time in our school day for more writing.

Additional References

Biancarosa, G., & Snow, C. E. (2006). Reading next: A vision for action and research in middle and high school literacy -- A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education.

Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). Writing next: Effective strategies to improve writing of adolescents in middle and high schools -- A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York . Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education.

Reader response is welcomed. Email your comments to LRP@/

- Conferences & Events

- Anita's Picks

Recent Posts

- Going Beyond Appreciation This Teacher Appreciation Week: Celebrating Empathy, Gratitude, and Inspiration

- The Double Helix of Reading and Writing: Fostering Integrated Literacy

- Uplifting Student Voices: Reflections on the AERA/ILA Writing Project

- ILA & AERA Amplify Student Voices on Equity

- Member Spotlight: Tihesha Morgan Porter

- For Network Leaders

- For Advertisers

- Privacy & Security

- Terms of Use

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.1: The Reading-Writing Connection

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 56156

- Athena Kashyap & Erika Dyquisto

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Importance of Reading

Reading stands at the heart of the process of writing academic essays. No matter what kinds of sources and methods you use, you are always reading and interpreting text. Most of us are used to hearing the word “reading” in relation to secondary sources, such as books, journals, magazines, websites, etc. But even if you are using other research methods and sources, such as interviewing someone or surveying a group of people, you are reading. You are 'reading' the subjects’ ideas and views on the topic you are investigating. When you study photographs, cultural artifacts, and other non-verbal research sources, you are 'reading' them by trying to connect them to their cultural and social contexts and to understand their multiple meanings. Principles of critical reading, which we are about to discuss in this chapter, apply to those research situations as well.

The Reading-Writing Connection

Creating new meanings.

Reading and writing are not two separate activities, but two tightly connected parts of the same whole. That whole is the process of learning and the creation of new meaning. It may seem that reading and writing are complete opposites of one another. According to the popular view, when we read, we “consume” texts, and when we write, we “produce” texts. But this view of reading and writing is true only if you see reading as a passive process of taking in information from the text, and not as an active and energetic process of making new meanings and new knowledge. Similarly, good writing does not originate in a vacuum, but is usually based upon, or at least influenced by, other ideas, theories, and stories that come from reading. So if, as a college student, you have ever wondered why your writing teachers have asked you to read books and articles and write responses to them, it is because writers who do not read and do not actively engage with their reading, have little to say to others.

Engaging in a Dialog

As rhetorical processes, reading and writing cannot exist without the other. The goal of a good writer is to engage the readers into a dialog presented in their writing. Similarly, the goal of a critical and active reader is to participate in that dialog and to have something to say back to the writer and to others. Writing leads to reading, and reading leads to writing. We write because we have something to say, and we read because we are interested in what others have to say.

Reading what others have to say and responding to them helps us make that all-important transition from simply having opinions about something, to having ideas. Opinions are often over-simplified and fixed. They are not very useful because, if different people have different opinions that they are not willing to change or adjust, such people cannot work or think together. Ideas, on the other hand, are ever evolving, fluid, and flexible. Our ideas are informed and shaped by our interactions with others, both in person and through written texts. In a world where thought and action count, it is not enough to simply “agree to disagree.” Reading and writing, used together, allow us to discuss complex and difficult issues with others, to persuade and be persuaded, and, most importantly, to act.

Active Reading

Successful students approach reading with a strategy that helps them get the most out of their reading. These students read actively. They look for the main idea of the material, its themes, and for words they do not understand. The opposite of reading actively is reading passively. Passive readers simply skip over things they do not understand and have difficulty understanding the material as a result. In this course, we are going to practice active reading. You will find that active reading is more enjoyable, lets you understand more of what you have read, and leads to better test scores.

The first part of active reading is to read through the material once while making notes about anything you find interesting or important. It is okay to not understand everything the first time through. Make a note next to any words you may need to look up later. When you finish, stop for a few minutes and think about what you just read. What is your first impression? Did you enjoy it? Why or why not? What was the most memorable part of the reading? Did something in it surprise you? Take a few minutes to add these thoughts to the notes you took while reading.

Now, take a break and go do something else. Go for a walk, run an errand, or take care of some chores. Allow yourself to absorb what you read without thinking too much about it or worrying about what you did not understand. When you come back, use a dictionary to look up the definitions of the words you marked earlier because you were not sure what they meant. Look at any sections you did not understand the first time through and see if they make more sense now. If something is still unclear, review your notes and briefly read the material a second time. Any confusing parts will likely be much clearer now, and if they are not, talk to your teacher or a tutor about them.

Exercise 1 \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Video: 10 Active Reading Strategies//Study Smart Study Less by Ana Mascara. All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

- As you watch the video, make brief notes of key ideas, as well as any words or concepts you don't understand well.

- Next, take a few moments to reflect on the video. Consider questions like: What was the most memorable part of the video? What is one new piece of information you learned? What questions do you have about the video?

- Review your notes. If you do not understand all of the main points, watch the video a second time. You don't have to watch the whole thing again – it's okay to just review sections that address the specific questions you have.

- Finally, add to or revise your initial notes. Were you able to answer your unresolved questions? Can you list the most important "take-aways" from the video? In other words, what are two or thre things from this video that you want to remember?

Print vs. Online Reading

In an online educational environment, you're probably going to do more reading than listening. You may do some of your reading in printed form – say, an assigned novel or textbook – but some of it might also be online in the form of a webpage and forums. Reading online isn't the same as reading in print, so you should practice some strategies that will improve your online reading comprehension and speed. And some of the tactics you learn about here will help you with any kind of reading you might do, not just the stuff that's online.

So what do we mean when we say that reading print is different from reading online?

- First, when you read something – let's say, a book – that's been printed by a reputable publishing house, you can assume that the work is authoritative. The author had to be vetted by a publishing house and multiple editors, right? But when you read something online, it may have been written or posted by anybody. This means that you have to seriously evaluate the authority of the information you're reading. Pay attention to who was writing what you're reading – can you identify the author? What are their credentials?

- Second, in the print world, texts may include pictures, graphics, or other visual elements to supplement the author's writing. But in the digital realm, this supplementary material might also include hyperlinks, audio, and video, as well. This will fundamentally change the reading experience for you because online reading can be interactive in a way that a print book can't. An online environment allows you to work and play with content rather than passively absorb it.

- Finally, when you read in print, you generally read sequentially, from the first word to the last. Maybe you'll flip to an index or refer to a footnote, but otherwise the way you read is fairly consistent and straightforward. Online, however, you can be led quickly into an entirely new area of reading by clicking on links or related content. Have you ever been studying for class and fall down a Wikipedia rabbit hole while looking for unfamiliar terms? You might have started by investigating the French Revolution, but half an hour later you find yourself reading about the experimental jazz scene in 1970s New York. You can't really do that with a book.

The Why, What, How of Reading Comprehension

Now that you've heard about how reading online differs from reading print, you should know that this has some really practical consequences for reading comprehension – how to understand and apply what you're reading. Improving your online reading comprehension will save you time and frustration when you work on your assignments. You'll be able to understand your course subject matter better, and your performance on your quizzes and exams will improve.

Consider the "why, what, and how" of reading comprehension:

- Why? Why am I being asked to read this passage? In other words, what are the instructions my professor has given me?

- What? What am I supposed to get out of this passage? That is, what are the main concerns, questions, and points of the text? What do you need to remember for class?

- How? How will I remember what I just read? In most cases, this means taking notes and defining key terms.

When you keep the "why, what and how" of reading comprehension in the forefront of your mind while reading, your understanding of the material will improve drastically. It will only take a few minutes but it will not only help you remember what you've read, but it will also help you structure any notes that you might want to take.

Purpose Of Academic Reading

Casual reading across genres, from books and magazines to newspapers and blogs, is something students should be encouraged to do in their free time because it can be both educational and fun. In college, however, instructors generally expect students to read resources that have particular value in the context of a course. Why is academic reading beneficial?

- Information comes from reputable sources : Web sites and blogs can be a source of insight and information, but not all are useful as academic resources. They may be written by people or companies whose main purpose is to share an opinion or sell you something. Academic sources such as textbooks and scholarly journal articles, on the other hand, are usually written by experts in the field and have to pass stringent peer review requirements in order to get published.

- Learn how to form arguments : In most college classes except for creating writing, when instructors ask you to write a paper, they expect it to be argumentative in style. This means that the goal of the paper is to research a topic and develop an argument about it using evidence and facts to support your position. Since many college reading assignments (especially journal articles) are written in a similar style, you’ll gain experience studying their strategies and learning to emulate them.

- Exposure to different viewpoints : One purpose of assigned academic readings is to give students exposure to different viewpoints and ideas. For example, in an ethics class, you might be asked to read a series of articles written by medical professionals and religious leaders who are pro-life or pro-choice and consider the validity of their arguments. Such experience can help you wrestle with ideas and beliefs in new ways and develop a better understanding of how others’ views differ from your own.

Active Learning When Reading

Many instructors conduct their classes mainly through lectures. The lecture remains the most pervasive teaching format across the field of higher education. One reason is that the lecture is an efficient way for the instructor to control the content, organization, and pace of a presentation, particularly in a large group. However, there are drawbacks to this “information-transfer” approach, where the instructor does all the talking and the students quietly listen: student have a hard time paying attention from start to finish; the mind wanders. Also, current cognitive science research shows that adult learners need an opportunity to practice newfound skills and newly introduced content. Lectures can set the stage for that interaction or practice, but lectures alone don’t foster student mastery. While instructors typically speak 100–200 words per minute, students hear only 50–100 of them. Moreover, studies show that students retain 70 percent of what they hear during the first ten minutes of class and only 20 percent of what they hear during the last ten minutes of class.

Thus it is especially important for students in lecture-based courses to engage in active learning outside of the classroom. But it’s also true for other kinds of college courses—including the ones that have active learning opportunities in class. Why? Because college students spend more time working (and learning) independently and less time in the classroom with the instructor and peers. Also, much of one’s coursework consists of reading and writing assignments. How can these learning activities be active? The following are very effective strategies to help you be more engaged with, and get more out of, the learning you do outside the classroom:

- Write in your books : You can underline and circle key terms, or write questions and comments in the margins of your books. The writing serves as a visual aid for studying and makes it easier for you to remember what you’ve read or what you’d like to discuss in class. If you are borrowing a book or want to keep it unmarked so you can resell it later, try writing key words and notes on Post-its and sticking them on the relevant pages.

- Annotate a text : Annotations typically mean writing a brief summary of a text and recording the works-cited information (title, author, publisher, etc.). This is a great way to “digest” and evaluate the sources you’re collecting for a research paper, but it’s also invaluable for shorter assignments and texts, since it requires you to actively think and write about what you read. The activity, below, will give you practice annotating texts.

- Create mind maps : Mind maps are effective visual tools for students, as they highlight the main points of readings or lessons. Think of a mind map as an outline with more graphics than words. For example, if a student were reading an article about America’s First Ladies, she might write, “First Ladies” in a large circle in the center of a piece of paper. Connected to the middle circle would be lines or arrows leading to smaller circles with visual representations of the women discussed in the article. Then, these circles might branch out to even smaller circles containing the attributes of each of these women.

The following video discusses the process of creating mind maps further and shows how they can be a helpful strategy for active reading engagement:

Video: How to Use a Mind Map by Two-Point-Four. Rights Reserved. Standard YouTube license.

In addition to the strategies described above, the following are additional ways to engage in active reading and learning:

- Work when you are fully awake, and give yourself enough time to read a text more than once.

- Read with a pen or highlighter in hand, and underline or highlight significant ideas as you read (but only the significant ideas--overhighlighting can be counter-productive).

- Interact with the ideas in the margins (summarize ideas; ask questions; paraphrase difficult sentences; make personal connections; answer questions asked earlier; challenge the author; etc.).

- What is the CONTEXT in which this text was written? (This writing contributes to what topic, discussion, or controversy? Context is bigger than this one written text.)

- Who is the intended AUDIENCE ? (There’s often more than one intended audience.)

- What is the author’s PURPOSE ? To entertain? To explain? To persuade? (There’s usually more than one purpose, and essays almost always have an element of persuasion.)

- How is this writing ORGANIZED ? Compare and contrast? Classification? Chronological? Cause and effect? (There’s often more than one organizational form.)

- What is the author’s TONE ? (What are the emotions behind the words? Are there places where the tone changes or shifts?)

- What TOOLS does the author use to accomplish her/his purpose? Facts and figures? Direct quotations? Fallacies in logic? Personal experience? Repetition? Sarcasm? Humor? Brevity?

- What is the author’s THESIS— the main argument or idea, condensed into one or two sentences?

- Foster an attitude of intellectual curiosity. You might not love all of the writing you’re asked to read and analyze, but you should have something interesting to say about it, even if that “something” is critical.

Planning and Managing Your Reading for Optimal Comprehension

Your college courses will sharpen both your reading and your writing skills. Most of your writing assignments—from brief response papers to in-depth research projects—will depend on your understanding of course reading assignments or related readings you do on your own. And it is difficult, if not impossible, to write effectively about a text that you have not understood. Even when you do understand the reading, it can be hard to write about it if you do not feel personally engaged with the ideas discussed.

This section discusses strategies you can use to get the most out of your college reading assignments. These strategies fall into three broad categories:

- Planning strategies to help you manage your reading assignments.

- Comprehension strategies to help you understand the material.

- Active reading strategies to take your understanding to a higher and deeper level.

Planning Your Reading

Have you ever stayed up all night cramming just before an exam? Or found yourself skimming through a detailed memo from your boss five minutes before a crucial meeting? The first step in handling college reading successfully is planning. This involves both managing your time, and setting a clear purpose for your reading.

Managing Your Reading Time

You will learn more detailed strategies for time management in Section 1.4, but for now, focus on setting aside enough time for reading and breaking your assignments into manageable chunks. If you are assigned a seventy-page chapter to read for next week’s class, try not to wait until the night before to get started. Give yourself at least a few days and tackle one section at a time.

Your method for breaking up the assignment will depend on the type of reading. If the text is very dense and packed with unfamiliar terms and concepts, you may need to read no more than five or ten pages in one sitting so that you can truly understand and process the information. With more user-friendly texts, you will be able to handle longer sections—twenty to forty pages, for instance. And if you have a highly engaging reading assignment, such as a novel you cannot put down, you may be able to read lengthy passages in one sitting.

As the semester progresses, you will develop a better sense of how much time you need to allow for the reading assignments in different subjects. It also makes sense to preview each assignment well in advance to assess its difficulty level and to determine how much reading time to set aside.

College instructors often set aside reserve readings for a particular course. These consist of articles, book chapters, or other texts that are not part of the primary course textbook. Copies of reserve readings are available through the university library, in print, or online. When you are assigned a reserve reading, download it ahead of time (and let your instructor know if you have trouble accessing it). Skim through it to get a rough idea of how much time you will need to read the assignment in full.

Setting a Purpose

The other key component of planning is setting a purpose. Knowing what you want to get out of a reading assignment helps you determine how to approach it and how much time to spend on it. This helps you stay focused, especially when you are tired and would rather relax.

Sometimes your purpose is simple. You might just need to understand the reading material well enough to discuss it intelligently in class the next day. However, your purpose will often go beyond that. For instance, you might also read to compare two texts, to formulate a personal response to a text, or to gather ideas for future research. Here are some questions to ask to help determine your purpose:

- Read Chapter 2 and come to class prepared to discuss current teaching practices in elementary math.

- Read these two articles and compare Smith’s and Jones’s perspectives on the 2010 health care reform bill.

- Read Chapter 5 and think about how you could apply these guidelines to running your own business.

- How deeply do I need to understand the reading? If you are majoring in computer science and you are assigned to read Chapter 1, “Introduction to Computer Science,” it is safe to assume the chapter presents fundamental concepts that you will be expected to master. However, for some reading assignments, you may be expected to form a general understanding but not necessarily master the content. Again, pay attention to how your instructor presents the assignment.

- How does this assignment relate to other course readings or to concepts discussed in class? Your instructor may make some of these connections explicitly, but if not, try to draw connections on your own. (Needless to say, it helps to take detailed notes-- when in class and when you read.)

- How might I use this text again in the future? If you are assigned to read about a topic that has always interested you, your reading assignment might help you develop ideas for a future research paper. Some reading assignments provide valuable tips or summaries worth bookmarking for future reference. Think about what you can take from the reading that will stay with you.

Improving Your Comprehension

You have blocked out time for your reading assignments and set a purpose for reading. Now comes the challenge: making sure you actually understand all the information you are expected to process. Some of your reading assignments will be fairly straightforward. Others, however, will be longer or more complex, so you will need to plan how to handle them.

For any expository writing—that is, nonfiction, informational writing—your first comprehension goal is to identify the main points and relate any details to these main points. Because college-level texts can be challenging, you will also need to monitor your reading comprehension. That is, you will need to stop periodically and assess how well you understand what you are reading. Finally, you can improve your comprehension by determining which strategies work best for you and putting those strategies into practice.

Responding, Not Reacting, to Texts

As stated earlier in this chapter, actively responding to difficult texts, posing questions, and analyzing ideas presented in them is the key to successful reading. The goal of an active reader is to engage in a conversation with the text that he or she is reading. In order to fulfill this goal, it is important to understand the difference between reacting to the text and responding to it.

Reacting to a text is often done on an emotional—rather than on an intellectual—level. It is often quick and shallow. For example, if we encounter a text that advances arguments with which we strongly disagree, it is natural to dismiss those ideas out of hand as flawed and unworthy of our attention. Doing so would be reacting to the text based only on emotions and on our pre-determined opinions about its arguments. It is easy to see that reacting in this way does not take the reader any closer to understanding the text. A wall of disagreement that existed between the reader and the text before the reading continues to exist after the reading.

Responding to a text, on the other hand, requires a careful study of the ideas presented and the arguments advanced in it. Critical readers who possess this skill are not willing to simply reject or accept the arguments presented in the text after the first reading right away. To continue with our example from the preceding paragraph, a reader who responds to a controversial text rather than reacting to it might apply several of the following strategies before forming and expressing an opinion about that text.

Writing in the Reading Process

If you want to become a critical reader, you need to get into the habit of writing as you read. You also need to understand that complex texts often require multiple close readings. During the second and any subsequent readings, however, you will need to write, and write a lot. The following are some critical reading and writing techniques which active readers employ as they work to create meanings from texts they read.

Overall Strategies

- Read the text several times, taking notes, asking questions, and underlining key places. Look for “starring sentences,” or those phrases or passages that use language in creative, memorable ways to underline key points.

- Study why the author of the text advances ideas, arguments, and convictions, so different from the reader’s own. For example, is the text’s author advancing an agenda of some social, political, religious, or economic group of which he or she is a member?

- Study the purpose and the intended audience of the text.

- Study the history of the argument presented in the text as much as possible. For example, modern texts on highly controversial issues such as the death penalty, abortion, or euthanasia often use past events, court cases, and other evidence to advance their claims. Knowing the history of the problem will help you to construct a more comprehensive meaning of a difficult text.

- Study the social, political, and intellectual context in which the text was written. Good writers use social conditions to advance controversial ideas. Compare the context in which the text was written to the one in which it is read. For example, have social conditions changed, thus invalidating the argument or making it stronger?

- Consider the author’s (and your own) previous knowledge of the issue at the center of the text and your experiences with it. How might such knowledge or experience have influenced your reception of the argument?

Taking all these steps will help you to move away from simply reacting to a text and towards constructing an informed and critical response to it

Reading Responses

Writing students are often asked to write one or two page exploratory responses to readings, but they are not always clear on the purpose of these responses and on how to approach writing them. By writing reading responses, you are continuing the important work of critical reading, which you began when you underlined interesting passages and took notes on the margins. You are extending the meaning of the text by creating your own commentary to it and perhaps even branching off into creating your own argument inspired by your reading. Your teacher may give you a writing prompt or ask you to come up with your own topic for a response. In either case, realize that reading responses are supposed to be exploratory, designed to help you delve deeper into the text you are reading than note-taking, or underlining, will allow. When writing extended responses to the reading, it is important to keep one thing in mind, and that is the purpose of writing a response. The purpose of these exploratory responses, which are often rather informal, is not to produce a complete argument, (with an introduction, thesis, body, and conclusion). It is not to impress your classmates and your teacher with “big” words and complex sentences. On the contrary, it is to help you understand the text you are working with, at a deeper level. The verb “explore” means to investigate something by looking at it more closely. Investigators get leads, some of which are fruitful and useful and some of which are dead-ends. As you investigate and create the meaning of the text you are working with, do not be afraid to take different directions with your reading response. In fact, it is important to resist the urge to make conclusions or think that you have found out everything about your reading. When it comes to exploratory reading responses, a lack of closure and the presence of more leads at the end of the piece is usually a good thing. Remember to always check with your teacher for standards and the format of reading responses. Try the following guidelines to write a successful response to a reading:

- Remember your goal—exploration. The purpose of writing a response is to construct the meaning of a difficult text. It is not to get the job done as quickly as possible and in as few words as possible.

- As you write, “talk back to the text.” Make comments, ask questions, and elaborate on complex thoughts. This part of the writing becomes much easier if, prior to writing your response, you had read the assignment with a pen in hand and marked important places in the reading.

- If your teacher provides a response prompt, make sure you understand it. Then try to answer the questions in the prompt to the best of your ability. While you are doing that, do not be afraid of bringing in related texts, examples, or experiences. Active reading is about making connections, which will help the reader understand the text better.

- While your primary goal is exploration and questioning, make sure that others can understand your response. While it is OK to be informal in your response, make every effort to write in clear, error-free language.

- Involve your audience in the discussion of the reading by asking questions, expressing opinions, and connecting to responses made by others.

Talk about the Text

In addition to talking about the readings in class, talk with classmates, or a tutor, outside of class. This can help you clarify and deepen your understanding of the text.

Get into the habit of composing extended responses to readings. Writing students are often asked to write one or two-page exploratory responses to readings, but they are not always clear on the purpose of these responses and on how to approach writing them. By writing reading responses, you are continuing the important activities of critical reading, which you began when you compiled notes on the salient points of the text you are analyzing. You are extending the meaning of the text by creating your own commentary to it and perhaps even branching off into creating your own argument inspired by your reading. Your teacher may give you a writing prompt, or ask you to come up with your own topic for a response. In either case, realize that reading responses are supposed to be exploratory; they are designed to help you delve deeper into the text you are reading than mere note-taking or underlining will allow. Sometimes, parts of your reading responses may wind up in an essay you write.

Monitoring Your Comprehension

Finding the main idea and paying attention to text features as you read will help you figure out what you know. Just as important, however, is being able to figure out what you do not know and developing a strategy to deal with it.

Textbooks often include comprehension questions in the margins or at the end of a section or chapter. As you read, stop occasionally to answer these questions, on paper or, in your head. Use the questions and your answers to identify sections you may need to reread, read more carefully, or ask your instructor about later.

Even when a text does not have built-in comprehension features, you can actively monitor your own comprehension. Try these strategies, adapting them as needed to suit different kinds of texts:

- Summarize. At the end of each section, pause to summarize -- in your own words -- the main points in a few sentences. If you have trouble doing so, revisit that section.

- Ask and answer questions. When you begin reading a section, try to identify two to three questions you should be able to answer after you finish it. Write down your questions and use them to test yourself on the reading. If you cannot answer a question, try to determine why. Is the answer buried in that section of reading but just not coming across to you? Or do you expect to find the answer in another part of the reading?

- Do not read in a vacuum. Look for opportunities to discuss the reading with your classmates. Many instructors set up online discussion forums or blogs specifically for that purpose. Participating in these discussions can help you determine whether your understanding of the main points is the same as your peers’.

These discussions can also serve as a reality check. If everyone in the class struggled with the reading, it may be exceptionally challenging. If it was a breeze for everyone but you, you could seek out your instructor for help.

Choose any text that that you have been assigned to read for one of your college courses. In your notes, complete the following tasks:

- Summarize the main points of the text in two/ three sentences.

- Write down two or three questions about the text that you can bring up during class discussion.

Students are often reluctant to seek help. They sometimes feel that doing that marks them as slow, weak, or demanding. The truth is, every learner occasionally struggles. If you are sincerely trying to keep up with the course reading but feel like you are in over your head, seek out help. Speak up in class, schedule a meeting with your instructor, or visit your university learning center for assistance.

Deal with the problem as early in the semester as you can. Instructors respect students who are proactive about their own learning. Most instructors will work hard to help students who make the effort to help themselves.

Contributors

- Adapted from EDUC 1300: Effective Learning Strategies . Provided by: Lumen Learning. Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Adapted from Writing for Success . Provided by: The Saylor Foundation. L CC-NC-SA 3.0 .

This page most recently updated on June 5, 2020.

The Connections Between Reading and Writing Expository Essay

Introduction, strategies and activities.

Reading and writing are the abilities of a child to acquire knowledge through an extensive process of learning that normally goes on during the entire life and is done unconsciously. However, significant percent of children do not acquire these abilities in spite of going through the same learning processes as their peers and having a normal intellectual capacity in all other aspects (Chamot, 2001).

Question generating is the strategy that encourages children to ask and answer questions after reading. The questions act as reference points that were not understood. In addition, the teacher should be evaluating teaching skills according to what they have learnt.

Inference is another method that involves teaching children to make their own conclusions after reading. This enables them to understand and think critically. This gives them invaluable insight regarding effective reading and writing skills.

Another way to learn children to read and write well is to read to them because pupils should be able to recognize written words accurately and fluently. This is done when the teacher uses a strategy of reading, so they can understand pronunciations.

Taking notes is another strategy for learning reading and writing. Taking notes helps children to remember sections of the readings. Thus, they develop a better understanding of a subject. The notes also help the teacher to monitor their reading and writing progress, which is a reflection of effective teaching skills.

Another method is rereading. By reading once, the text may not be understood well, thus children should reread it until they understand everything quite well.

Sustained silent reading helps to increase reading speed, thus students should be trained on silent reading. This will improve understanding of text including long sentences. Other children, as a form of compensatory strategy, manage to deduce the content of a sentence based on the rest words which the text contains even when individual words are read (Reid, 2000).

Uninterrupted Reading is an integral part of reading and writing strategy that improves a child’s reading ability and should be personal tailored to each child’s developmental needs and provided regularly. The teacher should be engaged in creating a reading-friendly environment for pupils to be able read without interruptions.

Language Experience is an important condition of successful learning. Teacher should teach in a language he/she understands well. This will enable them to build on a three step process of understanding how child learns, discovering the child’s lingual weaknesses by careful observation, and utilizing the language to patch up communication difficulties.

Responsive Writing is crucial for the teaching process to be successful because the rapport between teacher and learner is very important. People have various learning needs that are affected by factors that facilitate and inhibit learning such as motivation, readiness, involvement, feedback, repetition, as well as timing, environment, emotions, physiologic events and cultural barriers

In creating a visual aim for some particular group of learners, it is very important to take into account the development of cognitive learning.

Written Conversation technique is very important. The ability to process information when text read is used as such, there is the need to explore the cognitive learning.

Children should be encouraged to retell what they have read to others and the teacher should correct the mistake.

Pupils should use line markers to underline the most important information of the text they read. The teacher should check the underlined parts to see whether they are important.

The next condition is the fact that children should be able to preview the text they are to read.

This will help teachers in perceiving students as information processors enabling them to develop more effective and innovative teaching ideas. This will help the children to acquire and develop learning language (Reichl, 2009).

Chamot, A. U. (2001). Scott Foresman ESL.: Accelerating English language learning, Volume 1. New York: Pearson Education, Limited.

Reichl, S. (2009). Cognitive Principles, Critical Practice: Reading Literature at University. Göttingen: V&R Unipress GmbH.

Reid, J. M. (2000). The Learning Style Preferences of ESL Students. Tesol Quarterly , 21 (2), 87-110.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, October 19). The Connections Between Reading and Writing. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-connections-between-reading-and-writing/

"The Connections Between Reading and Writing." IvyPanda , 19 Oct. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/the-connections-between-reading-and-writing/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'The Connections Between Reading and Writing'. 19 October.

IvyPanda . 2018. "The Connections Between Reading and Writing." October 19, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-connections-between-reading-and-writing/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Connections Between Reading and Writing." October 19, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-connections-between-reading-and-writing/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Connections Between Reading and Writing." October 19, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-connections-between-reading-and-writing/.

- Learning To Read With Rubrics. Assisting Kindergarten Learners To Improve Reading Skills

- Critique of English Lesson Plan

- Silent Spring and Environmental Issues

- Importance of Educational Management Essay

- Affecting of Curfews on Teens

- Single-Gender Education in Saudi Arabia

- Is a Gap Year Necessary for High School Graduates?

- Multicultural Education: Cohesion and Understanding of the Learning Environment

Reading & Writing Purposes

Introduction: critical thinking, reading, & writing, critical thinking.

The phrase “critical thinking” is often misunderstood. “Critical” in this case does not mean finding fault with an action or idea. Instead, it refers to the ability to understand an action or idea through reasoning. According to the website SkillsYouNeed [1]:

Critical thinking might be described as the ability to engage in reflective and independent thinking.

In essence, critical thinking requires you to use your ability to reason. It is about being an active learner rather than a passive recipient of information.

Critical thinkers rigorously question ideas and assumptions rather than accepting them at face value. They will always seek to determine whether the ideas, arguments, and findings represent the entire picture and are open to finding that they do not.

Critical thinkers will identify, analyze, and solve problems systematically rather than by intuition or instinct.

Someone with critical thinking skills can:

- Understand the links between ideas.

- Determine the importance and relevance of arguments and ideas.

- Recognize, build, and appraise arguments.

- Identify inconsistencies and errors in reasoning.

- Approach problems in a consistent and systematic way.

- Reflect on the justification of their own assumptions, beliefs and values.

Read more at: https://www.skillsyouneed.com/learn/critical-thinking.html

Critical thinking—the ability to develop your own insights and meaning—is a basic college learning goal. Critical reading and writing strategies foster critical thinking, and critical thinking underlies critical reading and writing.

Critical Reading

Critical reading builds on the basic reading skills expected for college.

College Readers’ Characteristics

- College readers are willing to spend time reflecting on the ideas presented in their reading assignments. They know the time is well-spent to enhance their understanding.

- College readers are able to raise questions while reading. They evaluate and solve problems rather than merely compile a set of facts to be memorized.

- College readers can think logically. They are fact-oriented and can review the facts dispassionately. They base their judgments on ideas and evidence.

- College readers can recognize error in thought and persuasion as well as recognize good arguments.

- College readers are skeptical. They understand that not everything in print is correct. They are diligent in seeking out the truth.

Critical Readers’ Characteristics

- Critical readers are open-minded. They seek alternative views and are open to new ideas that may not necessarily agree with their previous thoughts on a topic. They are willing to reassess their views when new or discordant evidence is introduced and evaluated.

- Critical readers are in touch with their own personal thoughts and ideas about a topic. Excited about learning, they are eager to express their thoughts and opinions.

- Critical readers are able to identify arguments and issues. They are able to ask penetrating and thought-provoking questions to evaluate ideas.

- Critical readers are creative. They see connections between topics and use knowledge from other disciplines to enhance their reading and learning experiences.

- Critical readers develop their own ideas on issues, based on careful analysis and response to others’ ideas.

The video below, although geared toward students studying for the SAT exam (Scholastic Aptitude Test used for many colleges’ admissions), offers a good, quick overview of the concept and practice of critical reading.

Critical Reading & Writing

College reading and writing assignments often ask you to react to, apply, analyze, and synthesize information. In other words, your own informed and reasoned ideas about a subject take on more importance than someone else’s ideas, since the purpose of college reading and writing is to think critically about information.

Critical thinking involves questioning. You ask and answer questions to pursue the “careful and exact evaluation and judgment” that the word “critical” invokes (definition from The American Heritage Dictionary ). The questions simply change depending on your critical purpose. Different critical purposes are detailed in the next pages of this text.

However, here’s a brief preview of the different types of questions you’ll ask and answer in relation to different critical reading and writing purposes.

When you react to a text you ask:

- “What do I think?” and

- “Why do I think this way?”

e.g., If I asked and answered these “reaction” questions about the topic assimilation of immigrants to the U.S. , I might create the following main idea statement, which I could then develop in an essay: I think that assimilation has both positive and negative effects because, while it makes life easier within the dominant culture, it also implies that the original culture is of lesser value.

When you apply text information you ask:

- “How does this information relate to the real world?”

e.g., If I asked and answered this “application” question about the topic assimilation , I might create the following main idea statement, which I could then develop in an essay: During the past ten years, a group of recent emigrants has assimilated into the local culture; the process of their assimilation followed certain specific stages.

When you analyze text information you ask:

- “What is the main idea?”

- “What do I want to ‘test’ in the text to see if the main idea is justified?” (supporting ideas, type of information, language), and

- “What pieces of the text relate to my ‘test?'”

e.g., If I asked and answered these “analysis” questions about the topic immigrants to the United States , I might create the following main idea statement, which I could then develop in an essay: Although Lee (2009) states that “segmented assimilation theory asserts that immigrant groups may assimilate into one of many social sectors available in American society, instead of restricting all immigrant groups to adapting into one uniform host society,” other theorists have shown this not to be the case with recent immigrants in certain geographic areas.

When you synthesize information from many texts you ask:

- “What information is similar and different in these texts?,” and

- “What pieces of information fit together to create or support a main idea?”

e.g., If I asked and answered these “synthesis” questions about the topic immigrants to the U.S. , I might create the following main idea statement, which I could then develop by using examples and information from many text articles as evidence to support my idea: Immigrants who came to the United States during the immigration waves in the early to mid 20th century traditionally learned English as the first step toward assimilation, a process that was supported by educators. Now, both immigrant groups and educators are more focused on cultural pluralism than assimilation, as can be seen in educators’ support of bilingual education. However, although bilingual education heightens the child’s reasoning and ability to learn, it may ultimately hinder the child’s sense of security within the dominant culture if that culture does not value cultural pluralism as a whole.

Critical reading involves asking and answering these types of questions in order to find out how the information “works” as opposed to just accepting and presenting the information that you read in a text. Critical writing involves recording your insights into these questions and offering your own interpretation of a concept or issue, based on the meaning you create from those insights.

- Crtical Thinking, Reading, & Writing. Authored by : Susan Oaks, includes material adapted from TheSkillsYouNeed and Reading 100; attributions below. Project : Introduction to College Reading & Writing. License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- Critical Thinking. Provided by : TheSkillsYouNeed. Located at : https://www.skillsyouneed.com/ . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright . License Terms : Quoted from website: The use of material found at skillsyouneed.com is free provided that copyright is acknowledged and a reference or link is included to the page/s where the information was found. Read more at: https://www.skillsyouneed.com/

- The Reading Process. Authored by : Scottsdale Community College Reading Faculty. Provided by : Maricopa Community College. Located at : https://learn.maricopa.edu/courses/904536/files/32966438?module_item_id=7198326 . Project : Reading 100. License : CC BY: Attribution

- image of person thinking with light bulbs saying -idea- around her head. Authored by : Gerd Altmann. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/light-bulb-idea-think-education-3704027/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- video What is Critical Reading? SAT Critical Reading Bootcamp #4. Provided by : Reason Prep. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Hc3hmwnymw . License : Other . License Terms : YouTube video

- image of man smiling and holding a lightbulb. Authored by : africaniscool. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/man-african-laughing-idea-319282/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy

- Academic Skills

- Reading, writing and referencing

- Writing effectively

Connecting ideas

How to connect ideas at the sentence and paragraph level in academic writing.

What is cohesion?