Much Ado About Teaching

How to craft a killer thesis statement.

Thesis statements are tricky. Maybe that’s because there’s so much pressure riding on them. How do you distill all of the ideas of an essay into one or two sentences? It has also been said that the thesis statement is a road map, marking the path of an essay and guiding the reader through the points of the body paragraphs.

I think that intimidates the heck out of students.

A Better Way to Approach Thesis Statements

A thesis statement, in its simplest terms, is a statement. That’s a nice starting point. Instead of conveying all the implications above, and scaring students, just start by saying, I want you to make a statement.

They can handle that.

They like to make statements with their clothes or their taste in music. In doing so, they express something about who they are and how they see things. This isn’t that much different. They are going to express something, an opinion.

That’s the next step… to have an opinion.

If our goal as writing instructors is to teach our students how to write, not what to write, then we must preach that they express their own ideas. And it all starts with the thesis. They must make a statement that comes from their own thinking and understanding. They must write for themselves. Unfortunately, most student write based on what they think their teacher wants to hear.

Years of experience back this up. Each spring I spend a week grading the AP Literature exam essays. Over the course of the seven days, I typically grade 1,100-1,300 essay. The ones that stand out check off the same boxes — insightful and original thesis, perceptive analysis, well-appointed textual support, and a strong and confident voice. The lower-half essays do just the opposite.

What a Thesis Should Do

A more advanced, but still not intimidating, way to think about the thesis is to view it as engine of the essay. That’s something that can all understand and relate to. After all, high school kids want to drive everywhere. With a car, the engine converts energy into power, making all the other parts move. The engine propels it forward. The same is true of a good thesis. It moves the argument or opinion forward. It makes all the other parts of the essay turn.

Our students have the keys to a powerful engine that will move the reader.

They are in control.

And they get to decide where the reader is going.

That’s different than a roadmap with landmarks and coordinates already plotted and submissively followed. An engine gives them the freedom to go where they want.

The Finer Qualities of a Thesis

- It moves from the general to the specific

- It has insight

- It is original

- It answers the prompt

An Example of a Rock-Solid Thesis

Here’s a prompt I gave my students this week:

Chapter 26 of How to Read Literature Like a Professor questions, “Is He Serious? And Other Ironies.” Using Foster’s text as a guide, analyze the use of irony in 1984 and connect its purpose to the meaning of the work as a whole.

A Sample Weak Thesis

Here is a formulaic, superficial thesis that our students need to avoid.

In George Orwell’s futuristic novel, 1984, irony plays a major part and affects many of the novel’s plot twists, contributing to the development of the story and the meaning of the work as a whole.

Let’s poke some holes for a second. There are two glaring weakness with this thesis statement:

1. It basically repeats the prompt, hiding the true voice of the writer.

2. There no insight, and perhaps worse, there is no demonstration that this writer has read 1984 .

A Stronger Thesis

In the novel 1984, Winston feels the incongruity between appearance and reality in this supposed utopia, but as he crusades against the psychological manipulations of the party he ultimately is doomed to conform to its power.

What makes this better?

- It start with general ideas — in the novel 1984 — but it quickly identifies specific elements by naming a character, mentioning the utopia, and identifying the goals of the party.

- It has insight because it argues that Winston is aware of the irony that exists between the party’s propaganda and reality, but it sets up the bigger irony of the crusader that is doomed to love Big Brother.

- It answers the prompt by identifying the irony — the supposed utopia — and connects that irony to the meaning of the work as a whole — psychological manipulation as a tool to maintain power.

Writing a Killer Thesis Statement

My class drafted that thesis statement during a mini lesson that connected 1984 and How to Read Literature Like a Professor.

Writing a good thesis statement is the result of two simple actions:

- understanding what the prompt is asking

- asking questions of yourself to develop insightful responses to the prompt

This prompt had two parts:

- The role of irony in 1984

- How that irony factors into the work as a whole

Here are the questions we asked in class during the mini lesson:

- What are some of the examples of irony in 1984? — The party slogans, the utopia/dystopia disconnect, the ministries, doublethink, the acts of betrayal.

- Are these examples limited or pervasive? They are pervasive

- Why has the party created a society in which these things are pervasive? Because it feeds their purpose, which is to have psychological control over its citizens. The more the party slogans are repeated and the more doublethink occurs, the more a person loses their humanity and becomes part of a herd mentality.

- Why does the party want to strip people’s humanity and exert psychological control? It is how they can maintain totalitarian power.

When you progress through a sequence of questions that feed upon each other, you arrive at insightful conclusions that can be pieced together to form an outstanding thesis.

Brian Sztabnik is just a man trying to do good in and out of the classroom. He was a 2018 finalist for NY Teacher of the Year, a former College Board advisor for AP Lit, and an award-winning basketball coach.

Teacher Spotlight – Naomi Pate

You May Also Like

ASK US ANYTHING — UNIT PLANS, SOPHISTICATION, LATE NIGHTS, AND MORE

You’re Not Alone

Teaching Frankenstein

Please go to the Instagram Feed settings page to create a feed.

Copyright © 2024 DAHZ All Rights Reserved. Much Ado About Teaching.

It's Lit Teaching

High School English and TPT Seller Resources

- Creative Writing

- Teachers Pay Teachers Tips

- Shop My Teaching Resources!

- Sell on TPT

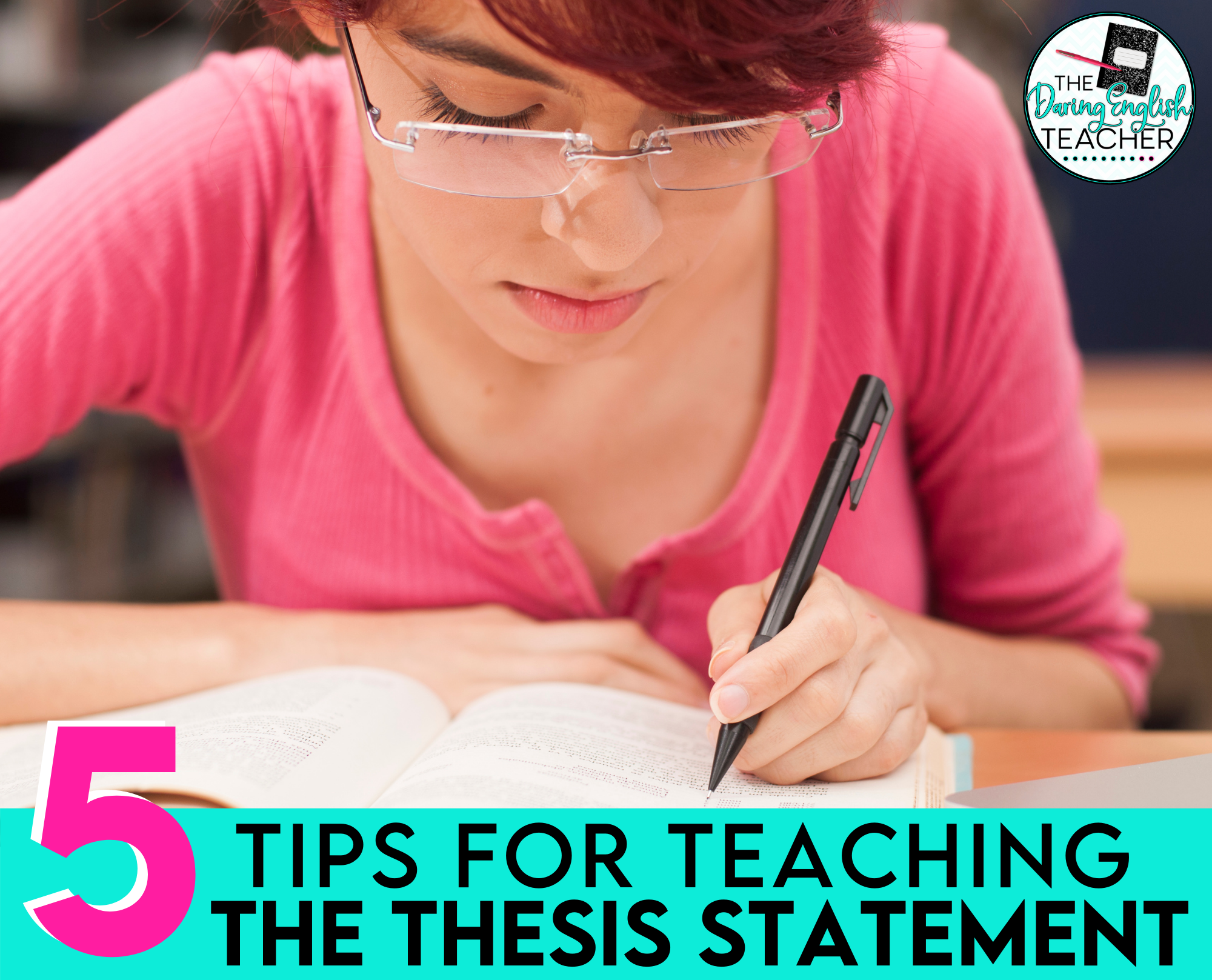

5 Tips for Teaching How to Write A Thesis Statement

The first time I had students write a thesis, I assumed they knew how to do it. After all, I learned all about the five-paragraph essay myself in middle school in the same school district. To my disappointment, not a single student knew how to write an adequate thesis statement. I realized it was a skill I was going to have to teach myself. After several papers and many years, here are my tips for teaching how to write a thesis statement.

Tips for Teaching How to Write a Thesis Statement #1: Teach Directly

You need a whole lesson around the thesis statement.

It can be ten minutes or a whole class period with note-taking and an activity.

But you have to spend some time directly teaching the thesis statement. You can’t expect students–even seniors in high school–to know what a thesis statement is, its purpose, or where it’s supposed to go.

If you’re teaching an essay writing unit, go ahead and explain the whole essay structure. But make sure you plan some time to specifically touch on the thesis statement and its role.

Don’t have a thesis-specific lesson? Check out my five-paragraph essay mini-lessons here , which include some thesis-specific slides.

Tips for Teaching How to Write a Thesis Statement #2: Explain The Role of a Thesis

I think it’s easy for students to grasp the concept of a thesis. It states what the essay is going to be about. They can get that.

But I think it’s much harder for students to understand how the thesis also guides and outlines the rest of the essay.

By the time they’re writing the conclusion statements for their body paragraphs, they’ve forgotten their own thesis and rarely reference it. Instead of letting their thesis dictate the topic of their body paragraphs, they get stuck trying to come up with something new.

Don’t just tell students what a thesis is. Spend some time showing them how the thesis continues to be referenced in every following paragraph. Show them how the ideas presented in their thesis statement will guide the following paragraphs.

Not sure how? This Unscramble the 5-Paragraph Essay Activity is a great start . Students will have to put the sentences in an essay in order, which can lead to some great discussions about how a strong thesis statement adds clarity to the rest of the essay’s structure.

Tips for Teaching How to Write a Thesis Statement #3: Give Students A Framework

If your students are struggling with writing strong thesis statements, give them a framework.

I know as teachers, it can get really boring to read “W is true because X, Y, Z.” But the structure does work, and it’s a great place for struggling writers to start.

If you’ve used other writing frameworks in class (such as claim, evidence, and reasoning or C-E-R ), your students will be familiar with having a structure for their writing. They’ll be familiar with the concept already and a lot more confident producing their own thesis statements.

Engage your students in more creative writing!

Sign up and get five FREE Creative Writing journal prompts to use with your students!

Opt in to receive news and updates.

Keep an eye on your inbox for your FREE journal prompts!

Tips for Teaching How to Write a Thesis Statement #4: Provide Lots of Examples

As with teaching all new skills, you can never have enough examples.

If your students are writing essays, provide them with examples for the topic they’re covering. But also provide lots of examples for other essay topics.

Give them examples that are both strong and weak, and let them discuss why each is which.

Let them peer-edit one another’s thesis statements.

You can do this in a note-taking style lesson, sit and get discussions, or, my personal favorite, a gallery walk.

If this last idea is interesting to you, check out my Writing Strong Thesis Statements Activity . You’ll place examples of both strong and weak thesis statements around the room. Then, students will have to walk around the room, identifying which statements are strong and which are weak. It’s a great jumping off point for deeper discussions around effective theses.

Tips for Teaching How to Write a Thesis Statement #5: Give Sentence Starters for More Scaffolding

If your students are still struggling, give them sentence starters.

Provide students with the thesis statement itself. Leave a blank for their overall argument and their three supporting reasons (if that’s the structure you expect from them).

Even if your students do alright with writing thesis statements, it might be nice to offer a variety of sentence starters to encourage them to try a new structure for their thesis.

Bonus Tip: Teach the Plural Form

This is a little silly, but I thought I would add it. Teach students that the plural of “thesis” is “theses.”

Every time I use the word “theses” in my classroom, students are tickled by it. I’m not sure why they find the plural version so odd, but it’s an interesting tidbit you can casually share with your students during one of your essay-writing lessons.

Like all good teaching, taking it slow and offering multiple forms of scaffolding is the key to teaching how to write a thesis statement.

If you’re looking for thesis or general essay-writing resources, check out my 5-Paragraph Essay Writing Resources Bundle!

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Activities to Teach How to Write A Thesis Statement

Research Writing , Secondary Literacy , Writing

If there’s any literacy skill you would want your English Language Arts students to master, it would probably be how to write a thesis statement . If you want to teach your students how to write powerful, eloquent, and exceptionally captivating thesis statements, then you’ll love the activities in this article.

The key to any good essay is a strong thesis statement. A strong thesis statement sets the tone and clarifies the author’s purpose : it tells you the writer’s opinion, along with the level of thought and criticism that has gone into formulating it.

A strong thesis statement also creates an alluring introduction paragraph. This makes each paper in your grading pile a lot more inviting.

How do you teach students to write a thesis statement to make their audience continue reading? This blog post explores six activities to teach how to write a thesis statement.

1. Differentiate Between Strong and Weak Thesis Statements

Writing a thesis statement might be a new skill for your students. Thesis statements are often taught as a topic sentence or the “whole essay boiled down into one sentence.” This can be a challenging concept for your students to grasp.

To teach how to write a thesis statement, have a discussion about what makes a strong thesis statement. You can turn this into a collaborative lesson by brainstorming clarifying statements ; these statements dictate what a thesis is and is not.

For example: “ A proper thesis statement is written in one sentence ,” or “ a proper thesis statement is directly related to the rest of the essay .” This is a great opportunity to teach students the difference between concepts like a “topic sentence” or a “hook.”

Your students can use this free bookmark to differentiate between a strong thesis statement and a weak one. This slideshow lesson also explores clarifying statements with detailed examples.

2. Evaluate Thesis Statement Examples

Now that students have plenty of guidelines, challenge their understanding by evaluating thesis statement examples . You can use thesis statement examples from past students’ essays. You can even write your own examples based on the clarifying statements you create with your class.

If you’re open to your students receiving constructive, anonymous criticism , you can even have them write a thesis statement and evaluate each one as a class. I’ve had success with providing students with a thesis statement topic and having them write a thesis statement. Then, I prompt them to swap with their elbow partner to offer feedback.

If you’d rather provide a comprehensive list of thesis statements that reflect the common errors you would typically see in students’ essays, there are several student examples in this introductory lesson on how to write a thesis statement – this is one of my favourite activities for teaching thesis statement writing!

3. Provide a Thesis Statement Template

One of the easiest ways to teach how to write a thesis statement is to offer a thesis statement template . There are a variety of thesis statement templates that students can use as a framework for their essays. I start with a basic template that involves the three parts of a thesis statement: a topic, position, and evidence . I then demonstrate to students how they can create variations of this template, depending on which order they introduce each part. You can find examples for each template in these thesis statement handouts .

You can also introduce a few sentence styles to your students. These styles scaffold eloquent thesis statements. They also offer students the space to articulate their thoughts without exceeding the one-sentence limit.

Sentence Styles for the Three Parts of a Thesis Statement

Here are a few sentence styles that incorporate the three parts of a thesis statement. Each style also includes an example written by a real student:

- Style A : “Noun phrase; Noun phrase; Noun phrase – Independent Clause” Example: “The promotion of hygiene; the presence of medical professionals; the prevention of death – these are all reasons why supervised injection services are an important facet of public health.”

- Style B : If (subject + verb + object phrase), if (subject + verb + object phrase ), if (subject + verb + object phrase ), then (independent clause) Example: “If taxpayers do not wish to have their money allocated to cruelty, if more than 100 million animals die from animal testing a year, if alternatives to animal testing exist, then governments should ban the practice of testing on animals.”

- Style C : Independent clause: subject + verb, subject + verb, subject + verb Example: “College education should be entirely funded by the government: student debt would be eliminated, education would not be commodified, and access to education would not be exclusive to privileged people.”

All of these sentence styles are outlined in these practice worksheets for how to write a thesis statement, with writing prompts to reinforce each thesis statement template through repeated practice.

4. Daily Practice Activities to Teach How to Write a Thesis Statement

One of the most effective ways to teach how to write a thesis statement is through repeated practice. You can do this by incorporating daily bell ringers into your persuasive writing unit. To assign this activity, I provide students with three topics to choose from. I then prompt them to develop an opinion and write a thesis statement for one.

I’ll also include bell ringers that provide a thesis statement that students need to evaluate. Students really enjoy these drills! They get the opportunity to develop opinions on interesting topics, and many of them choose to explore these ideas as the subject of their final research paper.

If you’re looking for pre-made worksheets with thesis statement activities, these daily thesis statement bell ringers include one month’s worth of thesis statement prompts, graphic organizers, and templates in both digital and ready-to-print format.

5. Use a Self-Assessment Thesis Statement Anchor Chart

You can provide students with a thesis statement anchor chart to reference the guidelines and rules they’ve learned. A personalized anchor chart is best – like this free thesis statement bookmark – so that students can have it on hand while they are reading and writing.

You can distribute the anchor chart at the beginning of your research paper unit. Students can refer to it while evaluating thesis statement examples or completing daily practice activities. A thesis statement anchor chart has been a complete game-changer in my classroom, and I’m pleased to learn that many of my students have held on to these after completing my course.

6. Provide Engaging Thesis Statement Topics

You can collaborate with your students to generate an engaging list of good topics for thesis statements. Start by writing down every topic that your students suggest. Then, you can narrow this list down to avoid broad, far-reaching thesis statements that lead to a watered-down essay. When I make this list with my students, we end up with topics that are truly engaging for them. I also have the opportunity to clarify which topics might be a little too vague or broad for an exceptional essay.

For example, students often suggest topics like “racism” or “the problem with school.” These are learning opportunities to demonstrate to students that a great thesis statement is the essential starting point for an even greater essay.

To elaborate, a topic like racism has different implications all over the world. It is far too complex to explore in a single, 750-word essay. Instead, we work together to narrow this topic down to something like “racism in the media,” or even better, “representation in Hollywood.”

Additionally, a topic like “the problem with school” is more of a conclusion. To solve this, we work backward to identify some of the aspects of our school that make it an obstacle . This can include uniforms, early starts, or cell phone policies. This process leads students to a more concise topic, like “cell phone policies in twenty-first-century schools.”

If you’re looking for engaging thesis statement topics to inspire your students, I’ve included a list of 75 argumentative essay topics in this practice unit for how to write a thesis statement .

Tying it All Together

There are plenty of fun thesis statement activities and practice lessons that you can incorporate into your curriculum. Give thesis statements the love and attention they deserve in the classroom – after all, they truly are the most important part of a research essay.

All of the worksheets, lessons, and activities explored in this blog post are included in Mondays Made Easy’s unit for teaching how to write a thesis statement . This bundle has everything you need to teach your students how to master their thesis statements and apply these essential literacy skills to their writing.

- Skip to right header navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Mastering How to Write Thesis Statements Once and For All

June 15, 2020 // by Lindsay Ann // 1 Comment

Sharing is caring!

Let’s face it…teaching students how to write thesis statements is not always easy. In fact, it can be downright frustrating sometimes, leaving you wishing you knew some fun ways to teach thesis statements

Thinking is messy. Students (and sometimes teachers, too) want to know exactly what to do, what to write, how to write good thesis statements to round off their intro paragraph .

Welcome to how to teach thesis statements 101. You’re in the right place if:

- You’ve ever felt like your students are robot zombies, spitting out formula thesis statements like Old Faithful.

- You’re tired of feeling like there could be a better way to teach thesis statement writing.

- You are fueled by coffee and a desire to help your students succeed.

Thesis Statement Structure

First off, a thesis statements should meet the following criteria:

- Opinion statement

- One sentence

- Offers unique insight

Within the one-sentence opinion statement that offers unique insight about a text, issue, or society, students should use clear and concise writing to make their focus known to the reader.

And, if you plan to give students a specific prompt, teach them to unpack the prompt to determine how they will respond.

Thesis Statements for Literary Analysis

9th grade English teachers at my school have developed the strategy of teaching students to think critically about texts’ messages about society and human nature through alien visitation. Talk about fun ways to teach thesis statement!!

They begin the school year by having an “alien” visit the classroom. Each class has to name its alien visitor who is there to observe human behavior. One year my officemate’s class named its alien “fre sha voca do” and I was amazed at how quickly her freshmen, who previously did not know how to write thesis statements, started thinking about “we as humans” messages.

As a sophomore teacher, all I have to do is say “we as humans” and students know exactly what I mean.

Now, what does this have to do with thesis statements?

💡 Well, if students are in the habit of thinking about what messages texts send about “we as humans,” they are primed for thesis statement writing.

Thesis Statements Template

It’s nice to have a pattern to teach students. As all patterns, once students learn it, they can break it, but I have found that this pattern does help them to clarify and focus their thinking. Yes, these patterns are one of the fun ways to teach thesis statements…because they provide structure which leads to success.

The basic literary analysis pattern for how to write thesis statements is as follows:

Genre + Title + Author + (optional literary element) + Action Verb + WAH phrase (or a specific human sub-group, i.e. children) + Claim + Why or How.

Let’s take a look at an example:

In his poem The Road Less Traveled, Robert Frost uses irony to suggest that we as humans lie to ourselves, creating a false sense of confidence in our own choices.

Genre = poem Title = The Road Less Traveled Author = Robert Frost Optional Literary Element = irony Action Verb = suggest WAH Phrase + Claim = we as humans lie to ourselves How = creating a false sense of confidence in our own choices

Here’s another example:

Let’s pretend that your students have just finished reading Born a Crime. Maybe you have asked them to compare and contrast Trevor Noah’s portrayal of apartheid to Alan Paton’s portrayal in Cry the Beloved Country.

Well, a good thesis statement for this prompt has to capture comparison between two texts.

Alan Paton’s novel Cry, the Beloved Country contrasts with Trevor Noah’s autobiography Born a Crime stylistically, though it touches on similar topics of racism and violence that plague post-apartheid South Africa; consequently, both texts reveal that we as humans must cling to hope and resilience even in the toughest of circumstances as the antidote to suffering.

Genres = novel, autobiography Titles = Cry, the Beloved Country, Born a Crime Authors = Alan Paton, Trevor Noah Optional Literary Element = (loosely mentioned) author’s style Action Verb = reveal WAH Phrase + Claim = we as humans must cling to hope and resilience even in the toughest of circumstances Why = hope / resilience are the antidote to suffering

Phew, that thesis statement had to cover a lot of ground. Notice the use of the subordinating conjunction consequently as a joiner word, making a one-sentence thesis statement possible.

How to Write Thesis Statements FAQ

Q: Do students have to follow the pattern exactly ? A: No. Like ice cream, students can feel free to add some toppings.

Q: Do students have to say “we as humans” every time? A: No. You can simply state the claim. The WAH statement is a frame to help students focus their thinking.

👍 Are there questions that you have that I haven’t thought of here? Please leave a comment on the post and I may add your question here!

Can Thesis Statements be Questions?

I’ve heard students ask if thesis statements in essays can be a question.

To understand why the answer is “no,” students need to understand that there is such a thing as inductive vs. deductive essay organization.

Students are familiar with deductive essay organization. This type of organization front-loads the thesis statement as a road map for the essay, using each paragraph to prove the main claim. This is like having a fully-completed puzzle and then examining different pieces of it.

Inductive organization, on the other hand, lacks a directly stated thesis in the beginning of the essay. Instead, the thesis comes at the end and the writer weaves together different points, often using questioning to move toward a final conclusion. This is like taking the puzzle pieces out of the box and completing the puzzle only to realize the fully-completed picture in the end.

So, students may see question-asking as a thesis writing technique, but not understand that it is an inductive organization technique leading to a larger implied or directly stated thesis.

Fun Ways to Teach Thesis Statements

Instruction for how to write thesis statements is pretty straightforward. I would suggest having students train their brains by practicing thesis statement writing individually and with peers.

➡️ This might be a quick GimKit or Quizziz game.

➡️ It might mean a round of “minute to win it” thesis statement writing so that students can practice turning thematic ideas into claims.

➡️ My students love using ultra clean erasable markers or whiteboard markers to write on their tables. I love that I am able to walk around and quickly redirect, cross out and make suggestions on the spot so that students can revise.

➡️ For digital learning situations, you could utilize Padlet to collect possible thesis statements and have students vote for their favorites that best follow the thesis statement pattern.

And maybe you want to get yourself an alien classroom pet. If students are struggling to write thesis statements, ask them what the alien would observe about humans after reading the text(s).

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to have some fre sha voca do.

Hey, if you loved this post, I want to be sure you’ve had the chance to grab a FREE copy of my guide to streamlined grading . I know how hard it is to do all the things as an English teacher, so I’m over the moon to be able to share with you some of my best strategies for reducing the grading overwhelm.

Click on the link above or the image below to get started!

About Lindsay Ann

Lindsay has been teaching high school English in the burbs of Chicago for 19 years. She is passionate about helping English teachers find balance in their lives and teaching practice through practical feedback strategies and student-led learning strategies. She also geeks out about literary analysis, inquiry-based learning, and classroom technology integration. When Lindsay is not teaching, she enjoys playing with her two kids, running, and getting lost in a good book.

Related Posts

You may be interested in these posts from the same category.

Incorporating Media Analysis in English Language Arts Instruction

How to Write a Descriptive Essay: Creating a Vivid Picture with Words

The Power of Book Tasting in the Classroom

20 Short Stories Students Will Read Gladly

6 Fun Book Project Ideas

Tailoring Your English Curriculum to Diverse Learning Styles

Teacher Toolbox: Creative & Effective Measures of Academic Progress for the Classroom

10 Most Effective Teaching Strategies for English Teachers

Beyond Persuasion: Unlocking the Nuances of the AP Lang Argument Essay

Book List: Nonfiction Texts to Engage High School Students

12 Tips for Generating Writing Prompts for Writing Using AI

31 Informational Texts for High School Students

Reader Interactions

[…] it’s even more complex to put it all down in writing: thesis statements and topic sentences, using evidence to prove a claim, paragraph structure, and idea […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to Write a Thesis Statement | 4 Steps & Examples

How to Write a Thesis Statement | 4 Steps & Examples

Published on January 11, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on August 15, 2023 by Eoghan Ryan.

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . It usually comes near the end of your introduction .

Your thesis will look a bit different depending on the type of essay you’re writing. But the thesis statement should always clearly state the main idea you want to get across. Everything else in your essay should relate back to this idea.

You can write your thesis statement by following four simple steps:

- Start with a question

- Write your initial answer

- Develop your answer

- Refine your thesis statement

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is a thesis statement, placement of the thesis statement, step 1: start with a question, step 2: write your initial answer, step 3: develop your answer, step 4: refine your thesis statement, types of thesis statements, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about thesis statements.

A thesis statement summarizes the central points of your essay. It is a signpost telling the reader what the essay will argue and why.

The best thesis statements are:

- Concise: A good thesis statement is short and sweet—don’t use more words than necessary. State your point clearly and directly in one or two sentences.

- Contentious: Your thesis shouldn’t be a simple statement of fact that everyone already knows. A good thesis statement is a claim that requires further evidence or analysis to back it up.

- Coherent: Everything mentioned in your thesis statement must be supported and explained in the rest of your paper.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

The thesis statement generally appears at the end of your essay introduction or research paper introduction .

The spread of the internet has had a world-changing effect, not least on the world of education. The use of the internet in academic contexts and among young people more generally is hotly debated. For many who did not grow up with this technology, its effects seem alarming and potentially harmful. This concern, while understandable, is misguided. The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its many benefits for education: the internet facilitates easier access to information, exposure to different perspectives, and a flexible learning environment for both students and teachers.

You should come up with an initial thesis, sometimes called a working thesis , early in the writing process . As soon as you’ve decided on your essay topic , you need to work out what you want to say about it—a clear thesis will give your essay direction and structure.

You might already have a question in your assignment, but if not, try to come up with your own. What would you like to find out or decide about your topic?

For example, you might ask:

After some initial research, you can formulate a tentative answer to this question. At this stage it can be simple, and it should guide the research process and writing process .

Now you need to consider why this is your answer and how you will convince your reader to agree with you. As you read more about your topic and begin writing, your answer should get more detailed.

In your essay about the internet and education, the thesis states your position and sketches out the key arguments you’ll use to support it.

The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its many benefits for education because it facilitates easier access to information.

In your essay about braille, the thesis statement summarizes the key historical development that you’ll explain.

The invention of braille in the 19th century transformed the lives of blind people, allowing them to participate more actively in public life.

A strong thesis statement should tell the reader:

- Why you hold this position

- What they’ll learn from your essay

- The key points of your argument or narrative

The final thesis statement doesn’t just state your position, but summarizes your overall argument or the entire topic you’re going to explain. To strengthen a weak thesis statement, it can help to consider the broader context of your topic.

These examples are more specific and show that you’ll explore your topic in depth.

Your thesis statement should match the goals of your essay, which vary depending on the type of essay you’re writing:

- In an argumentative essay , your thesis statement should take a strong position. Your aim in the essay is to convince your reader of this thesis based on evidence and logical reasoning.

- In an expository essay , you’ll aim to explain the facts of a topic or process. Your thesis statement doesn’t have to include a strong opinion in this case, but it should clearly state the central point you want to make, and mention the key elements you’ll explain.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . Everything else you write should relate to this key idea.

The thesis statement is essential in any academic essay or research paper for two main reasons:

- It gives your writing direction and focus.

- It gives the reader a concise summary of your main point.

Without a clear thesis statement, an essay can end up rambling and unfocused, leaving your reader unsure of exactly what you want to say.

Follow these four steps to come up with a thesis statement :

- Ask a question about your topic .

- Write your initial answer.

- Develop your answer by including reasons.

- Refine your answer, adding more detail and nuance.

The thesis statement should be placed at the end of your essay introduction .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, August 15). How to Write a Thesis Statement | 4 Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 25, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/thesis-statement/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write an essay introduction | 4 steps & examples, how to write topic sentences | 4 steps, examples & purpose, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

McGraw Center for Teaching and Learning

Preparing to write a teaching statement.

As you prepare to write your statement, reflect on your goals for teaching in your discipline or area of expertise. In determining your goals, consider not only your content objectives but also the ways of thinking or the intellectual skills you want your students to learn. (In fact, students learn facts and arguments by using or reasoning about them, integrating them into larger structures of knowledge.) You may also want to acknowledge the expansive habits of mind or being you want them to adopt.

In his guide to writing a teaching statement, Lee Haugan advises writers to consider their methods for meeting those objectives. How do you run your classes? What variety of in-class activities and assignments do you design and what do they ask students to do? Haugan also advises writers to consider their effectiveness as teachers. What evidence do you have of your students learning from their work?

As you respond to these questions, we encourage you not to lose sight of the disciplinary context of your teaching. This may mean illustrating your statement with specific examples, or even a critical incident, from your teaching. You want to take into account pedagogical debates about what and how to teach in your field. You may also want to think about the following questions, prompted by the research on what facilitates and impedes learning:

- What conceptions or misconceptions about concepts or inquiry in your field do students bring to your classroom? How do you build on, unsettle, or correct those beliefs?

- How do you get your students interested in or intellectually engaged with your field? What kinds of questions do you ask or problems do you pose to your students?

- How do you develop your students' interpretive frameworks, or how do you teach them to approach the objects of analysis in your field? What questions do you teach them to ask, and how do you teach them how to answer them?

- How do you explain or otherwise help students understand difficult ideas or concepts (hydrogen bonding, false consciousness)?

- How do you balance your objectives for your students with their own?

- What particular offering does your discipline make to a student's liberal arts education? How do you help students understand the implications or significance of what they're learning or learning how to do in your classes?

Formatting the Statement

Teaching statements are normally 1-2 page narratives written in the first-person, present-tense. Thus they're not comprehensive documents. But they can serve as the basis -- the thesis statement, if you will -- of a longer teaching or course portfolio. We'd be happy to guide you in the preparing of such a portfolio.

If you’re including your teaching statement in your dossier, keep in mind that the usual guidelines for job materials apply. Demonstrate knowledge without relying on jargon. Be persuasive but not dogmatic. Be sincere. You may want to ask your adviser or mentor to read your statement not only to verify disciplinary conventions but also, perhaps, to initiate a conversation about teaching and learning.

Gail Goodyear and Douglass Allchin assert that a teaching statement can help provide a guide or focus for your teaching. When shared with colleagues -- or potential colleagues -- "the statement can serve as an occasion for professional dialogue, growth, and development.” Thus it may also contribute to the valuation of teaching as a scholarly activity: public and available for review.

References and Resources:

Bain, Ken. What the Best College Teachers Do. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1994.

Bransford, John D. et al. How People Learn. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2000.

Goodyear, Gail and Douglass Allchin. “Statements of Teaching Philosophy.” The Center for Effective Teaching and Learning at the University of Texas at El Paso.

Haugan, Lee. “ Writing a Teaching Philosophy Statement. ” Center for Teaching Excellence, Iowa State University. March 1998.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Tips for Writing Your Thesis Statement

1. Determine what kind of paper you are writing:

- An analytical paper breaks down an issue or an idea into its component parts, evaluates the issue or idea, and presents this breakdown and evaluation to the audience.

- An expository (explanatory) paper explains something to the audience.

- An argumentative paper makes a claim about a topic and justifies this claim with specific evidence. The claim could be an opinion, a policy proposal, an evaluation, a cause-and-effect statement, or an interpretation. The goal of the argumentative paper is to convince the audience that the claim is true based on the evidence provided.

If you are writing a text that does not fall under these three categories (e.g., a narrative), a thesis statement somewhere in the first paragraph could still be helpful to your reader.

2. Your thesis statement should be specific—it should cover only what you will discuss in your paper and should be supported with specific evidence.

3. The thesis statement usually appears at the end of the first paragraph of a paper.

4. Your topic may change as you write, so you may need to revise your thesis statement to reflect exactly what you have discussed in the paper.

Thesis Statement Examples

Example of an analytical thesis statement:

The paper that follows should:

- Explain the analysis of the college admission process

- Explain the challenge facing admissions counselors

Example of an expository (explanatory) thesis statement:

- Explain how students spend their time studying, attending class, and socializing with peers

Example of an argumentative thesis statement:

- Present an argument and give evidence to support the claim that students should pursue community projects before entering college

English Teaching Toolkit

Adult ESL teaching resources to enhance your teaching and save you time

How to Write a Thesis Statement: Tips for Teaching

- December 7, 2023

- Adult ESL , Classroom Activities , Lesson Planning , Teaching Writing

Teaching academic writing can be challenging, especially when it comes to teaching students how to write a thesis statement. The thesis statement plays a central role in an essay, so it is worthwhile to spend a significant amount of time teaching this concept. Know that it will take time to refine and revise thesis statements for beginner writers.

What is a Thesis Statement?

A thesis statement:

- – is sometimes called a claim .

- – controls where the central ideas of an essay go.

- – is at the end of an introduction paragraph.

- – answers a prompt (a writing topic) or a question

- – expresses a viewpoint (a claim) or argues for an idea that the audience may not have considered (it does not state the obvious).

- – is concise, to-the-point, and 1-2 sentences long.

- – creates an argument that matches the required length of the essay.

- – is clearly and entirely explained and supported in the rest of an essay.

Teaching Thesis Statements

Before students begin writing a thesis statement, they need to analyze and discuss example thesis statements. Show students several examples of different types of thesis statements and how they directly answer the essay question/prompt. Break down example thesis statements. Analyze the different parts of the thesis and discuss their purposes. For example:

Give students step-by-step instructions for writing a thesis statement. Here are my five steps:

- 1. Understand the prompt.

- 2. Brainstorm and then select the best 2-3 ideas from that brainstorm.

- 3. Write a statement that expresses a viewpoint. Make sure it answers the prompt.

- 4. List reasons that support that viewpoint.

- 5. Combine your viewpoint statement and the reasons for that viewpoint.

Writing clear, concise thesis statements takes time. Encourage students to keep practicing, and incorporate explicit instruction in your class. Doing simple thesis analysis activities on a regular basis will help students get the hang of it.

Below is my best-selling Thesis Statement Guide ! This is a complete guide for beginning writers that includes thesis analysis activities and step-by-step instructions for how to write a thesis statement with a graphic organizer. I also have a Literary Analysis Essay Guide that takes students through the whole essay-writing process. These are perfect for middle school, high school, or ESL students who are ready for academic writing.

I hope these tips will make teaching writing easier for you, and that your students will grow into confident and skilled writers! Check out this related post on The Writing Process Steps and Why They Matter .

If you are starting out with writing paragraphs, check out this Paragraph Writing Bundle from my store!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

25 Thesis Statement Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

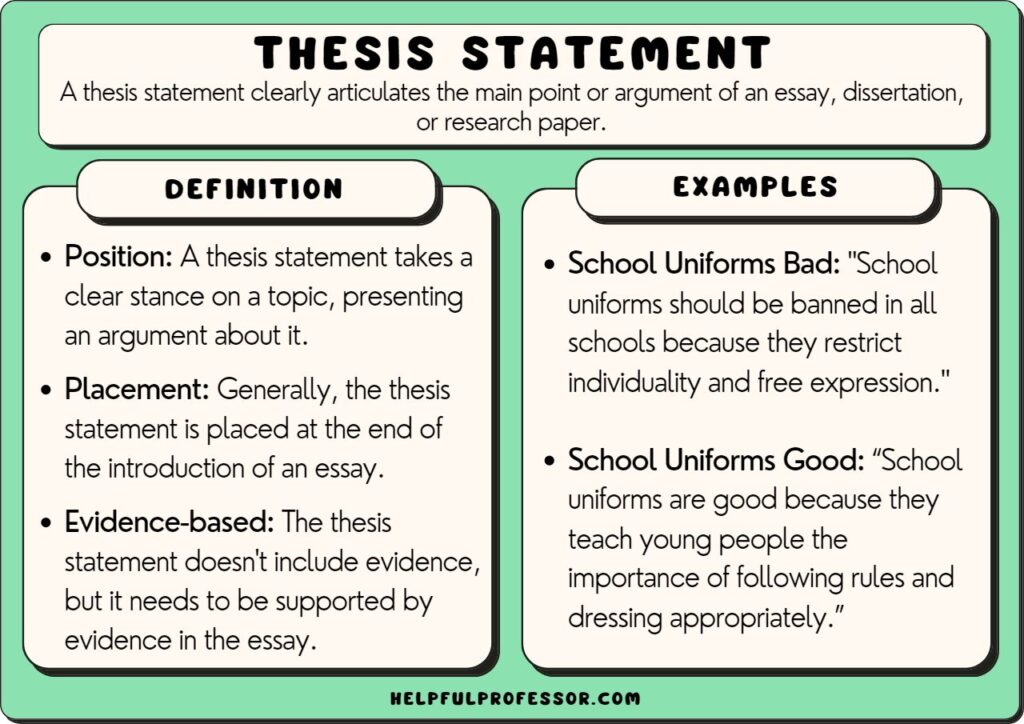

A thesis statement is needed in an essay or dissertation . There are multiple types of thesis statements – but generally we can divide them into expository and argumentative. An expository statement is a statement of fact (common in expository essays and process essays) while an argumentative statement is a statement of opinion (common in argumentative essays and dissertations). Below are examples of each.

Strong Thesis Statement Examples

1. School Uniforms

“Mandatory school uniforms should be implemented in educational institutions as they promote a sense of equality, reduce distractions, and foster a focused and professional learning environment.”

Best For: Argumentative Essay or Debate

Read More: School Uniforms Pros and Cons

2. Nature vs Nurture

“This essay will explore how both genetic inheritance and environmental factors equally contribute to shaping human behavior and personality.”

Best For: Compare and Contrast Essay

Read More: Nature vs Nurture Debate

3. American Dream

“The American Dream, a symbol of opportunity and success, is increasingly elusive in today’s socio-economic landscape, revealing deeper inequalities in society.”

Best For: Persuasive Essay

Read More: What is the American Dream?

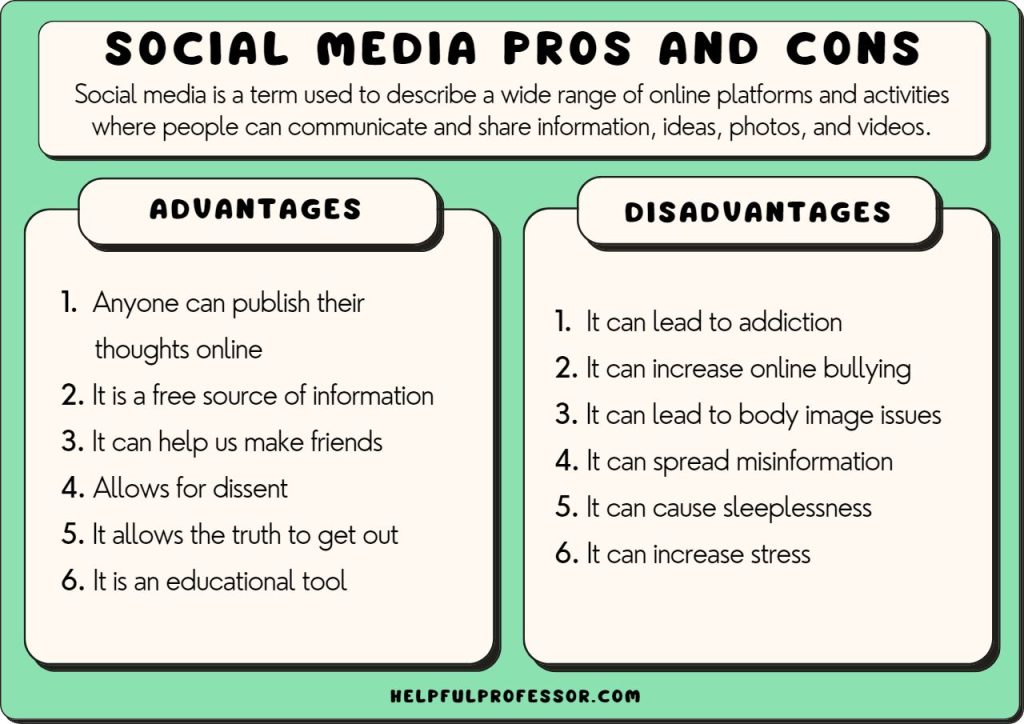

4. Social Media

“Social media has revolutionized communication and societal interactions, but it also presents significant challenges related to privacy, mental health, and misinformation.”

Best For: Expository Essay

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Social Media

5. Globalization

“Globalization has created a world more interconnected than ever before, yet it also amplifies economic disparities and cultural homogenization.”

Read More: Globalization Pros and Cons

6. Urbanization

“Urbanization drives economic growth and social development, but it also poses unique challenges in sustainability and quality of life.”

Read More: Learn about Urbanization

7. Immigration

“Immigration enriches receiving countries culturally and economically, outweighing any perceived social or economic burdens.”

Read More: Immigration Pros and Cons

8. Cultural Identity

“In a globalized world, maintaining distinct cultural identities is crucial for preserving cultural diversity and fostering global understanding, despite the challenges of assimilation and homogenization.”

Best For: Argumentative Essay

Read More: Learn about Cultural Identity

9. Technology

“Medical technologies in care institutions in Toronto has increased subjcetive outcomes for patients with chronic pain.”

Best For: Research Paper

10. Capitalism vs Socialism

“The debate between capitalism and socialism centers on balancing economic freedom and inequality, each presenting distinct approaches to resource distribution and social welfare.”

11. Cultural Heritage

“The preservation of cultural heritage is essential, not only for cultural identity but also for educating future generations, outweighing the arguments for modernization and commercialization.”

12. Pseudoscience

“Pseudoscience, characterized by a lack of empirical support, continues to influence public perception and decision-making, often at the expense of scientific credibility.”

Read More: Examples of Pseudoscience

13. Free Will

“The concept of free will is largely an illusion, with human behavior and decisions predominantly determined by biological and environmental factors.”

Read More: Do we have Free Will?

14. Gender Roles

“Traditional gender roles are outdated and harmful, restricting individual freedoms and perpetuating gender inequalities in modern society.”

Read More: What are Traditional Gender Roles?

15. Work-Life Ballance

“The trend to online and distance work in the 2020s led to improved subjective feelings of work-life balance but simultaneously increased self-reported loneliness.”

Read More: Work-Life Balance Examples

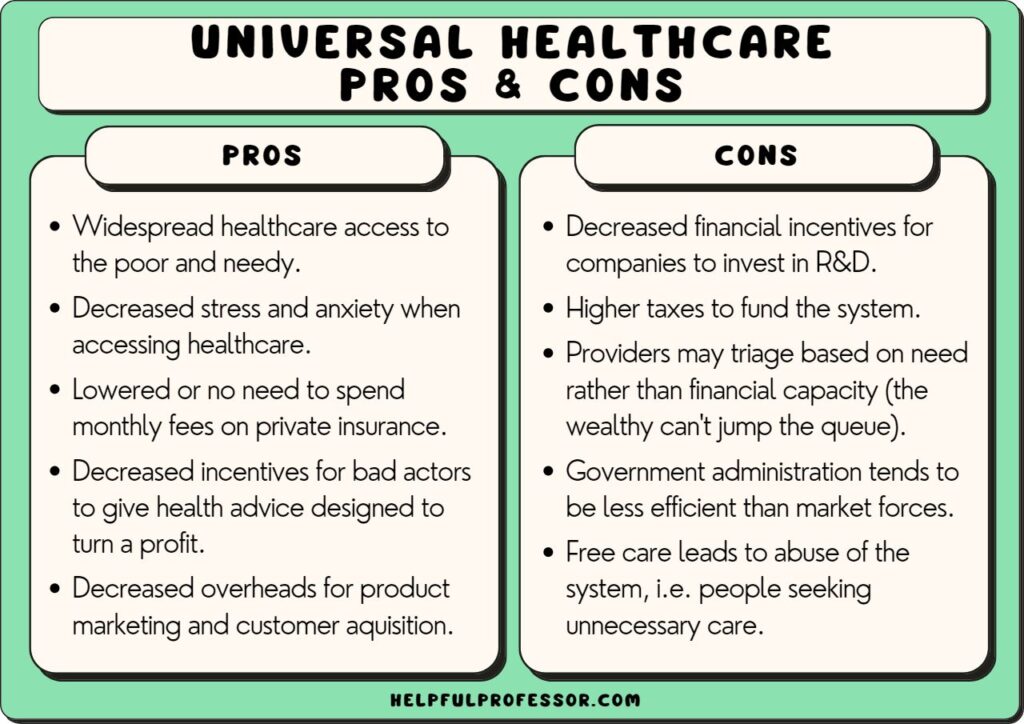

16. Universal Healthcare

“Universal healthcare is a fundamental human right and the most effective system for ensuring health equity and societal well-being, outweighing concerns about government involvement and costs.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Universal Healthcare

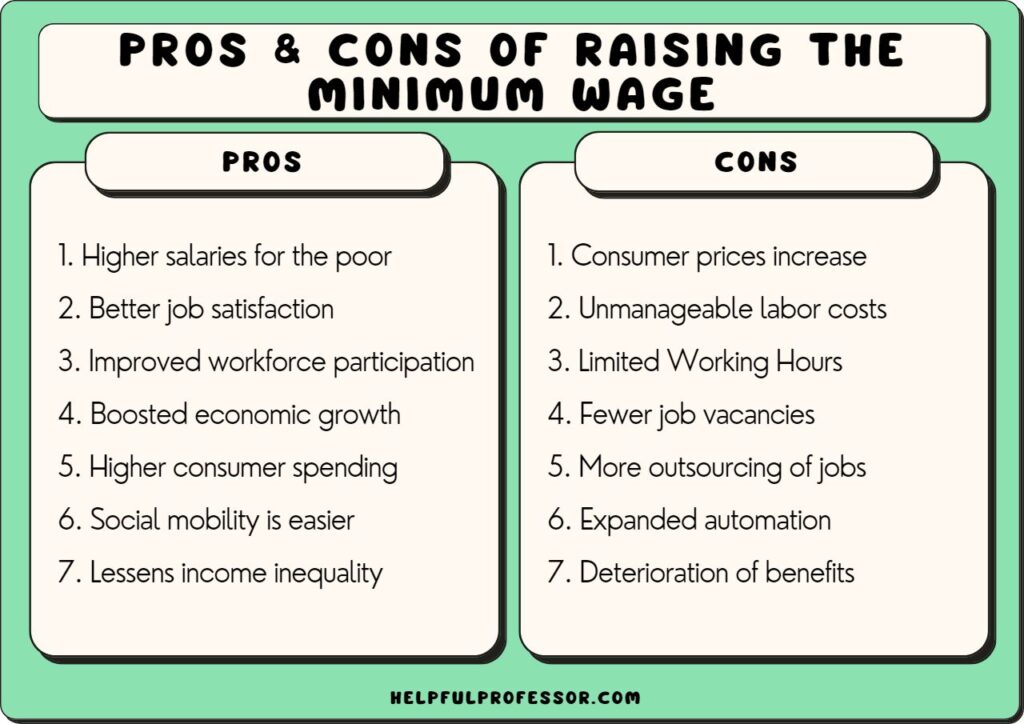

17. Minimum Wage

“The implementation of a fair minimum wage is vital for reducing economic inequality, yet it is often contentious due to its potential impact on businesses and employment rates.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Raising the Minimum Wage

18. Homework

“The homework provided throughout this semester has enabled me to achieve greater self-reflection, identify gaps in my knowledge, and reinforce those gaps through spaced repetition.”

Best For: Reflective Essay

Read More: Reasons Homework Should be Banned

19. Charter Schools

“Charter schools offer alternatives to traditional public education, promising innovation and choice but also raising questions about accountability and educational equity.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Charter Schools

20. Effects of the Internet

“The Internet has drastically reshaped human communication, access to information, and societal dynamics, generally with a net positive effect on society.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of the Internet

21. Affirmative Action

“Affirmative action is essential for rectifying historical injustices and achieving true meritocracy in education and employment, contrary to claims of reverse discrimination.”

Best For: Essay

Read More: Affirmative Action Pros and Cons

22. Soft Skills

“Soft skills, such as communication and empathy, are increasingly recognized as essential for success in the modern workforce, and therefore should be a strong focus at school and university level.”

Read More: Soft Skills Examples

23. Moral Panic

“Moral panic, often fueled by media and cultural anxieties, can lead to exaggerated societal responses that sometimes overlook rational analysis and evidence.”

Read More: Moral Panic Examples

24. Freedom of the Press

“Freedom of the press is critical for democracy and informed citizenship, yet it faces challenges from censorship, media bias, and the proliferation of misinformation.”

Read More: Freedom of the Press Examples

25. Mass Media

“Mass media shapes public opinion and cultural norms, but its concentration of ownership and commercial interests raise concerns about bias and the quality of information.”

Best For: Critical Analysis

Read More: Mass Media Examples

Checklist: How to use your Thesis Statement

✅ Position: If your statement is for an argumentative or persuasive essay, or a dissertation, ensure it takes a clear stance on the topic. ✅ Specificity: It addresses a specific aspect of the topic, providing focus for the essay. ✅ Conciseness: Typically, a thesis statement is one to two sentences long. It should be concise, clear, and easily identifiable. ✅ Direction: The thesis statement guides the direction of the essay, providing a roadmap for the argument, narrative, or explanation. ✅ Evidence-based: While the thesis statement itself doesn’t include evidence, it sets up an argument that can be supported with evidence in the body of the essay. ✅ Placement: Generally, the thesis statement is placed at the end of the introduction of an essay.

Try These AI Prompts – Thesis Statement Generator!

One way to brainstorm thesis statements is to get AI to brainstorm some for you! Try this AI prompt:

💡 AI PROMPT FOR EXPOSITORY THESIS STATEMENT I am writing an essay on [TOPIC] and these are the instructions my teacher gave me: [INSTUCTIONS]. I want you to create an expository thesis statement that doesn’t argue a position, but demonstrates depth of knowledge about the topic.

💡 AI PROMPT FOR ARGUMENTATIVE THESIS STATEMENT I am writing an essay on [TOPIC] and these are the instructions my teacher gave me: [INSTRUCTIONS]. I want you to create an argumentative thesis statement that clearly takes a position on this issue.

💡 AI PROMPT FOR COMPARE AND CONTRAST THESIS STATEMENT I am writing a compare and contrast essay that compares [Concept 1] and [Concept2]. Give me 5 potential single-sentence thesis statements that remain objective.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 19 Top Cognitive Psychology Theories (Explained)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 119 Bloom’s Taxonomy Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ All 6 Levels of Understanding (on Bloom’s Taxonomy)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Self-Actualization Examples (Maslow's Hierarchy)

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Understanding questions and writing thesis statements

I can understand the expectations of an essay question and write an effective thesis statement.

Lesson details

Key learning points.

- Annotating an essay question is a good way to understand the focus.

- A thesis is a clear overarching argument supported by the whole text.

- An effective thesis statement will focus on the big ideas and make reference to the whole text.

- Topic sentences start each paragraph and will focus on a specific character or moment in the text.

Common misconception

That planning is not something that needs to be practiced.

What are the benefits of practising planning over writing whole essay responses? Not only is planning a very important part of the writing process, but an efficient way to practise essay writing.

Idealistic - viewing something as perfect even if the reality suggests something different

Thesis - the overarching argument to an essay supported by the entire text

Topic sentence - the first sentence of a paragraph; it states the paragraph’s main idea

Aspiration - a hope or ambition of achieving something

Content guidance

- Contains depictions of discriminatory behaviour.

Supervision

Adult supervision suggested.

This content is © Oak National Academy Limited ( 2024 ), licensed on Open Government Licence version 3.0 except where otherwise stated. See Oak's terms & conditions (Collection 2).

Starter quiz

6 questions.

Analyse Edmundson’s use of language and structure

Edmundson -

What are the writer’s intention?

Power and identity -

What ideas are there around these concepts in Act 1?

Thesis statement -

Overarching argument, supported by the whole text.

Topic sentence -

It states the paragraph’s main idea.

Supporting detail -

References to the text which support your topic sentence.

Main quotations -

Quotations which support argument and require analysis.

Concluding sentence -

The final sentence of a paragraph.

Conclusion -

Sums up your essay’s overall thesis.

Developing a Thesis Statement

Many papers you write require developing a thesis statement. In this section you’ll learn what a thesis statement is and how to write one.

Keep in mind that not all papers require thesis statements . If in doubt, please consult your instructor for assistance.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement . . .

- Makes an argumentative assertion about a topic; it states the conclusions that you have reached about your topic.

- Makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of your paper.

- Is focused and specific enough to be “proven” within the boundaries of your paper.

- Is generally located near the end of the introduction ; sometimes, in a long paper, the thesis will be expressed in several sentences or in an entire paragraph.

- Identifies the relationships between the pieces of evidence that you are using to support your argument.

Not all papers require thesis statements! Ask your instructor if you’re in doubt whether you need one.

Identify a topic

Your topic is the subject about which you will write. Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic; or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper.

Consider what your assignment asks you to do

Inform yourself about your topic, focus on one aspect of your topic, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts, generate a topic from an assignment.

Below are some possible topics based on sample assignments.

Sample assignment 1

Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II.

Identified topic

Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis

This topic avoids generalities such as “Spain” and “World War II,” addressing instead on Franco’s role (a specific aspect of “Spain”) and the diplomatic relations between the Allies and Axis (a specific aspect of World War II).

Sample assignment 2

Analyze one of Homer’s epic similes in the Iliad.

The relationship between the portrayal of warfare and the epic simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64.

This topic focuses on a single simile and relates it to a single aspect of the Iliad ( warfare being a major theme in that work).

Developing a Thesis Statement–Additional information

Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic, or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper. You’ll want to read your assignment carefully, looking for key terms that you can use to focus your topic.

Sample assignment: Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II Key terms: analyze, Spain’s neutrality, World War II

After you’ve identified the key words in your topic, the next step is to read about them in several sources, or generate as much information as possible through an analysis of your topic. Obviously, the more material or knowledge you have, the more possibilities will be available for a strong argument. For the sample assignment above, you’ll want to look at books and articles on World War II in general, and Spain’s neutrality in particular.

As you consider your options, you must decide to focus on one aspect of your topic. This means that you cannot include everything you’ve learned about your topic, nor should you go off in several directions. If you end up covering too many different aspects of a topic, your paper will sprawl and be unconvincing in its argument, and it most likely will not fulfull the assignment requirements.

For the sample assignment above, both Spain’s neutrality and World War II are topics far too broad to explore in a paper. You may instead decide to focus on Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis , which narrows down what aspects of Spain’s neutrality and World War II you want to discuss, as well as establishes a specific link between those two aspects.

Before you go too far, however, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts. Try to avoid topics that already have too much written about them (i.e., “eating disorders and body image among adolescent women”) or that simply are not important (i.e. “why I like ice cream”). These topics may lead to a thesis that is either dry fact or a weird claim that cannot be supported. A good thesis falls somewhere between the two extremes. To arrive at this point, ask yourself what is new, interesting, contestable, or controversial about your topic.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times . Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Derive a main point from topic

Once you have a topic, you will have to decide what the main point of your paper will be. This point, the “controlling idea,” becomes the core of your argument (thesis statement) and it is the unifying idea to which you will relate all your sub-theses. You can then turn this “controlling idea” into a purpose statement about what you intend to do in your paper.

Look for patterns in your evidence

Compose a purpose statement.

Consult the examples below for suggestions on how to look for patterns in your evidence and construct a purpose statement.

- Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis

- Franco turned to the Allies when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from the Axis

Possible conclusion:

Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: Franco’s desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power.

Purpose statement

This paper will analyze Franco’s diplomacy during World War II to see how it contributed to Spain’s neutrality.

- The simile compares Simoisius to a tree, which is a peaceful, natural image.

- The tree in the simile is chopped down to make wheels for a chariot, which is an object used in warfare.

At first, the simile seems to take the reader away from the world of warfare, but we end up back in that world by the end.

This paper will analyze the way the simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64 moves in and out of the world of warfare.

Derive purpose statement from topic

To find out what your “controlling idea” is, you have to examine and evaluate your evidence . As you consider your evidence, you may notice patterns emerging, data repeated in more than one source, or facts that favor one view more than another. These patterns or data may then lead you to some conclusions about your topic and suggest that you can successfully argue for one idea better than another.

For instance, you might find out that Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis, but when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from them, he turned to the Allies. As you read more about Franco’s decisions, you may conclude that Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: his desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power. Based on this conclusion, you can then write a trial thesis statement to help you decide what material belongs in your paper.

Sometimes you won’t be able to find a focus or identify your “spin” or specific argument immediately. Like some writers, you might begin with a purpose statement just to get yourself going. A purpose statement is one or more sentences that announce your topic and indicate the structure of the paper but do not state the conclusions you have drawn . Thus, you might begin with something like this:

- This paper will look at modern language to see if it reflects male dominance or female oppression.

- I plan to analyze anger and derision in offensive language to see if they represent a challenge of society’s authority.

At some point, you can turn a purpose statement into a thesis statement. As you think and write about your topic, you can restrict, clarify, and refine your argument, crafting your thesis statement to reflect your thinking.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Compose a draft thesis statement

If you are writing a paper that will have an argumentative thesis and are having trouble getting started, the techniques in the table below may help you develop a temporary or “working” thesis statement.

Begin with a purpose statement that you will later turn into a thesis statement.

Assignment: Discuss the history of the Reform Party and explain its influence on the 1990 presidential and Congressional election.

Purpose Statement: This paper briefly sketches the history of the grassroots, conservative, Perot-led Reform Party and analyzes how it influenced the economic and social ideologies of the two mainstream parties.

Question-to-Assertion

If your assignment asks a specific question(s), turn the question(s) into an assertion and give reasons why it is true or reasons for your opinion.

Assignment : What do Aylmer and Rappaccini have to be proud of? Why aren’t they satisfied with these things? How does pride, as demonstrated in “The Birthmark” and “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” lead to unexpected problems?

Beginning thesis statement: Alymer and Rappaccinni are proud of their great knowledge; however, they are also very greedy and are driven to use their knowledge to alter some aspect of nature as a test of their ability. Evil results when they try to “play God.”

Write a sentence that summarizes the main idea of the essay you plan to write.

Main idea: The reason some toys succeed in the market is that they appeal to the consumers’ sense of the ridiculous and their basic desire to laugh at themselves.

Make a list of the ideas that you want to include; consider the ideas and try to group them.

- nature = peaceful

- war matériel = violent (competes with 1?)

- need for time and space to mourn the dead

- war is inescapable (competes with 3?)

Use a formula to arrive at a working thesis statement (you will revise this later).

- although most readers of _______ have argued that _______, closer examination shows that _______.

- _______ uses _______ and _____ to prove that ________.

- phenomenon x is a result of the combination of __________, __________, and _________.

What to keep in mind as you draft an initial thesis statement

Beginning statements obtained through the methods illustrated above can serve as a framework for planning or drafting your paper, but remember they’re not yet the specific, argumentative thesis you want for the final version of your paper. In fact, in its first stages, a thesis statement usually is ill-formed or rough and serves only as a planning tool.

As you write, you may discover evidence that does not fit your temporary or “working” thesis. Or you may reach deeper insights about your topic as you do more research, and you will find that your thesis statement has to be more complicated to match the evidence that you want to use.

You must be willing to reject or omit some evidence in order to keep your paper cohesive and your reader focused. Or you may have to revise your thesis to match the evidence and insights that you want to discuss. Read your draft carefully, noting the conclusions you have drawn and the major ideas which support or prove those conclusions. These will be the elements of your final thesis statement.

Sometimes you will not be able to identify these elements in your early drafts, but as you consider how your argument is developing and how your evidence supports your main idea, ask yourself, “ What is the main point that I want to prove/discuss? ” and “ How will I convince the reader that this is true? ” When you can answer these questions, then you can begin to refine the thesis statement.

Refine and polish the thesis statement

To get to your final thesis, you’ll need to refine your draft thesis so that it’s specific and arguable.

- Ask if your draft thesis addresses the assignment

- Question each part of your draft thesis

- Clarify vague phrases and assertions

- Investigate alternatives to your draft thesis

Consult the example below for suggestions on how to refine your draft thesis statement.

Sample Assignment

Choose an activity and define it as a symbol of American culture. Your essay should cause the reader to think critically about the society which produces and enjoys that activity.

- Ask The phenomenon of drive-in facilities is an interesting symbol of american culture, and these facilities demonstrate significant characteristics of our society.This statement does not fulfill the assignment because it does not require the reader to think critically about society.

Drive-ins are an interesting symbol of American culture because they represent Americans’ significant creativity and business ingenuity.

Among the types of drive-in facilities familiar during the twentieth century, drive-in movie theaters best represent American creativity, not merely because they were the forerunner of later drive-ins and drive-throughs, but because of their impact on our culture: they changed our relationship to the automobile, changed the way people experienced movies, and changed movie-going into a family activity.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast-food establishments, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize America’s economic ingenuity, they also have affected our personal standards.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast- food restaurants, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize (1) Americans’ business ingenuity, they also have contributed (2) to an increasing homogenization of our culture, (3) a willingness to depersonalize relationships with others, and (4) a tendency to sacrifice quality for convenience.

This statement is now specific and fulfills all parts of the assignment. This version, like any good thesis, is not self-evident; its points, 1-4, will have to be proven with evidence in the body of the paper. The numbers in this statement indicate the order in which the points will be presented. Depending on the length of the paper, there could be one paragraph for each numbered item or there could be blocks of paragraph for even pages for each one.

Complete the final thesis statement

The bottom line.

As you move through the process of crafting a thesis, you’ll need to remember four things:

- Context matters! Think about your course materials and lectures. Try to relate your thesis to the ideas your instructor is discussing.

- As you go through the process described in this section, always keep your assignment in mind . You will be more successful when your thesis (and paper) responds to the assignment than if it argues a semi-related idea.

- Your thesis statement should be precise, focused, and contestable ; it should predict the sub-theses or blocks of information that you will use to prove your argument.

- Make sure that you keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Change your thesis as your paper evolves, because you do not want your thesis to promise more than your paper actually delivers.

In the beginning, the thesis statement was a tool to help you sharpen your focus, limit material and establish the paper’s purpose. When your paper is finished, however, the thesis statement becomes a tool for your reader. It tells the reader what you have learned about your topic and what evidence led you to your conclusion. It keeps the reader on track–well able to understand and appreciate your argument.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.