Research Articles

.jnl-nr0sjg{display:inline-block;color:inherit;}.jnl-nr0sjg:hover{text-decoration:none;} gendered state: ‘governmentality’ and the labour migration policy of sri lanka.

Why a proactive research culture is necessary for advancing social sciences in Sri Lanka?

- Download links

Review Articles

Spiritual thirdspace and silent faith: reading the parallax between buddhism and christianity in the movie silence (2016).

Listening to the information needs of visually impaired users and implications for the libraries

Strategic human resource management challenges in graduate development officer recruitment in Sri Lanka

Common methods and outcomes of employee engagement: a systematic literature review towards identifying gaps in research

Electronic human resource management (e-HRM) adoption; a systematic literature review

Five years of RTI regime in Sri Lanka: factors causing low proactive disclosure of information and possible remedies

Impact of financial market development on economic growth: evidence from Sri Lanka

Job stress amongst female faculty members in higher education: an Indian experience from a feminist perspective

27 Apr 2023

Understanding social upheavals: beyond conspiracy theories

Assessing visitor preferences and willingness to pay for Marine National Park Hikkaduwa: application of choice experiment method

Thicker than blood: political parties, partisanship, and the indigenous identity movement in Nepal

Sri Lanka Journal of Social Sciences List of Referees - Volume 45 (2022)

Awareness and preventive practices related to COVID-19 pandemic among the Indian public

Mobile phone-enabled internet services and the technology readiness of the users

Food safety knowledge, attitude, and practices among school children: a cross-sectional study based in the Colombo educational zone, Sri Lanka

Early childhood language development: a case study of a Sri Lankan Tamil child’s progress in language acquisition

A cross-cultural approach to issues of male dominance and domestic violence

Nutritional and psychological interfaces in enhancing the quality of life

Book Reviews

International migration and development: survival or building up strategy by sarathchandra gamlath.

Influences on strategic functioning of the public universities of Sri Lanka: challenges and ground realities

Job seeker value proposition conceptualised from the perspective of the job choice theory

The tea dance: a choreographic representation of Tamil tea plantation workers within the modern Sri Lankan folk dance repertoire

14 Dec 2022

Patterns of romantic relationships and dating among youth in Sri Lanka

Lifestyle changes during the economic crisis: a Sri Lankans survey

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 31 July 2023

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Piumika Sooriyaarachchi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9570-2344 1 , 2 &

- Ranil Jayawardena ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7352-9365 3 , 4

3417 Accesses

Explore all metrics

The economic crisis in Sri Lanka has caused millions of people to descend into poverty, compromising their rights to health, education and standard of living. This study aimed to examine how the economic crisis has affected Sri Lankans’ lifestyles.

Subject and methods

An online cross-sectional survey was conducted in July 2022, using an e-questionnaire based on Google Forms. The questionnaire assessed respondents’ socio-demographics and lifestyle-related behaviours before and during the economic crisis. Descriptive statistics and multivariable logistic regression analysis were used.

A total of 1214 respondents, aged ≥ 18 years were included in this survey. During the crisis, there was a nearly 80% and 60% decline in alcohol consumption and smoking, respectively. Although many respondents (57.6%) used private vehicles as their primary mode of transportation before the crisis, this has decreased significantly (18.2%) during the crisis. Furthermore, 65.3% reported that their walking time has increased during this time. Respondents who lived in Colombo were significantly more likely to report increased walking time compared to people from other districts (OR 1.540; 95% CI, 1.081–2.193; P = 0.017). Also, those with the lowest monthly incomes reported a twofold increase in walking time during the crisis as those with the highest monthly incomes (OR = 2.224, 95% CI = 1.329–3.723, P = 0.002). Cooking methods used before and after the economic crisis differ significantly, with many respondents relying on gas (pre 92.8%; post 15.5%) as their primary cooking fuel before the crisis and now moving to firewood (pre 3.7%; post 46.5%). More than two-thirds (75.2%) of respondents were thinking of migrating to another country alone or with their families because of the country’s current situation.

The everyday activities of Sri Lankans have been significantly affected by the country’s economic crisis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on the dietary habits and lifestyle in a population in southern Spain: a cross-sectional questionnaire

Lifestyles of Older Adults in Castilla-La Mancha (Spain): Influence of Sex, Age, and Habitat

A cross-sectional assessment of food practices, physical activity levels, and stress levels in middle age and older adults’ during the COVID-19 pandemic

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sri Lanka is currently facing the worst economic crisis since its independence in 1948. According to reports, the crisis started in 2019 because of several interrelated, compounding events, including tax cuts, money creation, a national policy to switch to organic or biological farming, the 2019 Easter bombings, and the COVID-19 pandemic’s effects in Sri Lanka (Bhowmick 2022 ; Fowsar et al. 2021 ). Additionally, Russia was Sri Lanka’s second-largest tea export market; traditionally, Russians and Ukrainians have made up most of the nation’s non-South Asian visitors (Pereira et al. 2022).

The economic crisis in Sri Lanka is pushing millions of people into poverty and compromising their rights to health, education and quality of life. The country is currently experiencing a severe economic crisis, which has resulted in a shortage of commodities such as food, fuel, cooking gas, medicine (Jayawardena et al. 2023 ) and other necessities. People’s daily routines have been drastically altered because of the economic crisis, including changes to their eating, cooking and commuting habits, as well as other behaviours (Sooriyaarachchi & Jayawardena 2023 ). Food inflation (year on year) increased to 46.6% in April 2022 from 30.2% in March 2022, while non-food inflation (year on year) increased to 22.0% in April 2022 from 13.4% in March 2022 (Lanka 2022 ).

International literature has extensively addressed the effects of the financial crisis on social and economic life (Nolan 2014 ; Quail 2010 ). The reduction in income and the rise in unemployment are widely recognized as the basic and immediate consequence of the financial crisis, which is causing a significant portion of the population to live in extreme poverty (Zavras et al. 2013 ). Unemployment and reduced income are associated with mental disorders (Marmot and Bell 2009 ), addiction issues, substance abuse (Compton et al. 2014 ), smoking and alcohol use (de Goeij et al. 2015 ). Further, low socio-economic status often leads to the adoption of coping mechanisms such as the increased purchase of cheap food with low nutritional value (Brinkman et al. 2010 ) and poor disease management (Suhrcke et al. 2011 ). Furthermore, it is well-established that a lower socioeconomic position is linked to greater morbidity and mortality rates (Lund Jensen et al. 2017 ). A survey of older adults from 20 Mediterranean islands found that after the economic crisis started, there was a trend towards less healthful behaviours, including more depressive symptoms and unhealthier dietary habits (Foscolou et al. 2017 ). In contrast, research has demonstrated that in developed nations, economic downturns are linked to healthier lifestyle choices, such as a rise in physical activity, a rise in fruit and vegetable consumption, and a reduction in obesity (Ariizumi and Schirle 2012 ; Gerdtham and Ruhm 2006 ; Ruhm 2000 ). In addition, studies on the effect of economic crises on alcohol and cigarette use have yielded quite a range of outcomes (Ahmad and Franz 2008 ; Bruggink et al. 2016 ).

Food preparation methods have changed in response to previous economic downturns. For instance, during Russia’s economic collapse in 1998, low-income households increased the amount of food they produced at home with staple foods to lower the cost per calorie of food (Dore et al. 2003 ). According to a survey done in Greece, people’s transportation preferences have shifted in favour of sustainable transport forms of transportation during the country’s economic crisis (Papagiannakis et al. 2018 ). Owing to financial constraints, they preferred the use of public transportation, bicycle or walking instead of private vehicles (Galanis et al. 2017 ).

These altered lifestyle habits unintentionally provided by the economic crisis can result in more significant, long-lasting socio-cultural changes. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the changes in lifestyle behaviours among Sri Lankans during the economic crisis.

Methodology

Using Google Forms, a three-week countrywide online cross-sectional survey was conducted among adult Sri Lankan citizens in July 2022. Online social media channels were used to disseminate the link to the survey and volunteers were requested to take part. The specific recruitment strategy for the online survey is described in detail elsewhere. The survey was conducted in compliance with the guidelines outlined in the Helsinki Declaration (Association 2014 ). Ethical permission for the study was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee, Nawaloka Hospitals Research and Education Foundation, Colombo, Sri Lanka. The informed consent form was attached at the start of the electronic questionnaire, and participants completed it voluntarily and anonymously.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was made available in English, Sinhala and Tamil languages, and included both multiple-choice and open-ended questions. It consisted of two main sections with questions regarding (i) Socio-demographic and socio-economic background and (ii) changes in lifestyle behaviours during and before the economic crisis.

The first section included questions on respondents’ gender, age, district, residential area (inner city, suburban and rural), ethnicity (Sinhalese, Sri Lankan Tamil, Indian Tamil, Moors and Others), education status (secondary education or below, tertiary education, degree/diploma or above), number of family members, children (having children or no), employment status, monthly income and main source of monthly income.

The second section consisted of questions on lifestyle habits. To study the changes in food consumption and food substitution, respondents were asked to list the foods they used to eat before the economic crisis but no longer do during the economic crisis. They were also asked to mention any food items they may have substituted for the main course during the economic downturn. Participants were asked to categorize their changes as (i) increase, (ii) decrease and (iii) no change to study how addictive behaviours, such as smoking and drinking alcohol, have changed over the crisis time. They were asked to choose their primary mode of transportation before and during the crisis from a given list of six answers to determine the changes in the mode of transportation: (i) walking, (ii) cycling, (iii) motorbike, (iv) private vehicle, (v) public transport and (vi) hired vehicles. To determine the change in walking time before and during, the participants were required to choose one from three options: (i) increase, (ii) decrease and (iii) no change. Further, the changes in cooking methods were investigated by asking the respondents about their most common mode of cooking before and during the economic crisis. The following options were offered to choose from: (i) using gas, (ii) hot plates and electric cookers, (iii) using firewood, (iv) kerosene oil stove and (v) other methods. Additionally, the respondents were also questioned regarding their plans to immigrate to another nation due to the nation’s current state. The following options were offered: (i) yes, only myself (ii) yes, with my family (iii) no.

Statistical analysis

The demographic characteristics of the study sample were investigated using descriptive statistics. For categorical variables, frequency and percentages were used to evaluate the general distribution, whereas continuous variables were evaluated using means and standard deviations. In addition, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were carried out to identify the sociodemographic variables that affected the change in lifestyle behaviours. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to express the findings of logistic regression analysis. Statistical significance was accepted as P < 0.05. The IBM SPSS statistics version 23.0 was used for all analyses (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

After removing incomplete and duplicate records, a total of 1214 valid respondents, aged ≥ 18 years were included in the final analysis. General characteristics of the population are reported in Table 1 . The survey population was primarily female (60%) and had a mean age (± SD) of 35.08 (± 9.54) years. Many participants were Sinhalese (93%) and represented the Colombo district (42.7%). When compared to inner-city and suburban regions, which each had 27.4% and 34.0% of responses, rural areas made up 38.6% of the total. Most participants (84.1%) had at least a professional degree and were either working permanently (67.3%) or temporarily (10.9%). Full-time students accounted for 8.6% of the sample, while unemployed and retired accounted for 10.7% and 2.6%, respectively. More than half of respondents (54.1%) had families of three to four members, with the average family size being 4.11 (± 1.29). Only 36.2% of respondents had children; of those, 58.6% had only one child and 32% had two children. Approximately 84% of respondents reported having a monthly income; of those, 22.5% made less than 50,000 LKR per month and 17% made more than 200,000 LKR per month. Most of the respondents mentioned government (34.3%) or public sector (37.2%) jobs as their main primary source of income.

Fish, cheese and bread were among the most often listed food items by respondents in response to the question concerning food products that were commonly used before the economic crisis but are no longer used during the economic crisis. In addition, the most prevalent food substitutes for main meals were boiled jack fruit, bread fruit, manioc and instant noodles.

Figure 1 shows the changes in smoking and alcohol use during the economic crisis. Alcohol use was reported by only 21.6% of the respondents. Among them, 79.4% reported that their drinking had decreased throughout the economic crisis, 19.5% reported no change in consumption, and only 1.1% reported higher consumption than before. In the population, there were extremely few respondents who reported smoking (5.8%). Out of them 64.3% and 27.1% reported that the smoking frequency was decreased and unchanged, respectively, while 8.6% declared their smoking has increased during this period.

Change in addictive behaviours during the economic crisis

There was a significant difference in the use of transportation methods before and during the economic crisis ( P < 0.001) (Fig. 2 ). Before the financial crisis, 57.6% of respondents indicated that private vehicles were the most popular form of transportation. However, during the economic crisis, only 18.2% of people were using their private vehicles. The majority of the respondents (49.6%) mentioned public transport as their main transportation method during the economic crisis. Although only 1.3% of respondents reported walking prior to the crisis, this number has increased to 12.7% during the crisis. In addition, 65.3% of respondents reported longer walking times during the crisis, and only 24.3% and 10.4% reported no change or longer walking times, respectively.

Modes of transportation before and during the economic crisis

Table 2 demonstrates the results of univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis for an increased walking time by socio-demographic variables. According to the univariate analysis, the respondent’s age and average monthly income were significantly associated with increased walking times. In the multinomial regression models adjusted for all the variables, the respondents from the Colombo district reported significantly increased walking time compared to respondents from other districts (OR = 1.540; 95% CI = 1.081–2.193; P = 0.017). Additionally, compared to those who made more than 200,000 LKR per month, those who earned less than 50,000 LKR per month reported a more than twofold increase in their walking time (OR = 2.224; 95% CI = 1.329–3.723; P = 0.002).

Furthermore, before the economic crisis, 92.8% of the respondents used gas for preparing their meals. The use of firewood, electric cookers and others before the crisis was 3.7%, 3.2% and 0.2%, respectively. However, during the economic crisis, the use of gas for cooking has drastically reduced to 15.5%. There was a significant increase in the use of firewood and electric cookers during the crisis period which was reported by 46.5% and 31.2% of respondents, respectively. Additionally, 6.8% reported use of various other methods for cooking.

When asked about their desire to immigrate, 55% of the respondents stated that they had made the decision to immigrate with their families, while 20.3% had thought about immigrating alone. In addition, 24.8% of respondents stated that they have not considered moving abroad because of other obligations.

This population-based study provides an overview of how the living habits of Sri Lankan citizens have altered during the ongoing economic crisis. According to our understanding, this study was one of the first to look at how the economic crisis affected Sri Lankans’ lifestyles. Although the survey questionnaire was shared across the country regardless of the geographic area via social media, Colombo has the highest representation. This distribution pattern could be due to several reasons such as communication facilities as well as the interest to participate. Similar representation patterns have been observed in the online surveys conducted in Sri Lanka during the COVID-19 lockdown period (Sooriyaarachchi et al. 2022 , 2021 ). Also, more than 80% of the respondents had a degree or higher-level educational qualifications. The results of surveys can always be related to respondents’ educational backgrounds. The greater response rate could be attributed to educated respondents’ interest in this topic.

Public health issues such as smoking, alcohol consumption and alcohol-related illnesses can be influenced either favourably or unfavourably by economic crises. Smoking and alcohol use were both extremely rare in the current survey population, with prevalence rates of 5.8% and 21.6%, respectively. This might be a result of the sample consisting of 60% female responders who do not smoke or drink. In Sri Lanka it was reported that the current prevalence of smoking and alcohol intake among females over the age of 18 is 0.1% and 1.2%, respectively (Katulanda et al. 2014 , 2011 ). It has also been noticed that drinking is positively associated with a lower level of education and an older age, although this survey sample was primarily made up of relatively young and educated persons (Katulanda et al. 2014 ). However, as per the results, both alcohol consumption and smoking rates have drastically reduced during the economic crisis. There is conflicting scientific research regarding how economic crises affect alcohol intake and alcohol-related health issues. Following the beginning of the economic and social change in Russia and other Eastern European nations in the early 1990s, alcohol use surged, and this was accompanied by an increase in mortality and accidents (Baker et al. 2011 ; Men et al. 2003 ). Contrary to the transition in Eastern Europe, Finland’s economic crisis during this period resulted in mass unemployment, but it also coincided with a decline in alcohol intake and alcohol-related mortality (Herttua et al. 2007 ; Valkonen et al. 2000 ). According to a Brazilian study, all age groups exhibited a decline in smoking rates during the economic crisis, though with varying patterns (Souza et al. 2021 ). Numerous factors, including tighter financial restrictions brought on by income decrease during a recession or price increases for tobacco or alcoholic beverages, could account for the decreased use among the respondents.

There was a significant increase in demand for public transportation during the economic crisis, even though many of the respondents had previously utilized private vehicles for transportation. The government’s lack of foreign exchange to import fuel created severe fuel and energy shortages making long queues at petrol stations and also a black market for fuel, putting more pressure on people (Shehan et al. 2022 ). Essential services, including buses, trains and even medical vehicles, have been put on hold because of fuel scarcity. To conserve the remaining fuel, the government had to take harsh steps, such as closing schools and offices, implementing work-from-home policies, and temporarily banning the sale of gasoline and diesel for non-essential vehicles (Shehan et al. 2022 ). The shortfall has also caused prices to increase sharply. These could be the reasons for most of the respondents to switch to public transport during the economic crisis.

Additionally, an increase in cycling and walking was noted. A similar finding was observed in a study conducted in the city of Volos, Greece (Galanis et al. 2017 ). According to their findings, Greek citizens have switched to sustainable mobility options during the country’s years of economic hardship. People preferred using public transportation, bicycles or walking for their commutes rather than driving their cars because of the rising unemployment rate and the decline in personal income (Galanis et al. 2017 ). According to the regression analysis, respondents from the Colombo area and those with lower monthly incomes were significantly more likely to report increased walking. More people will choose walking over other forms of transportation, especially for short distances within cities, the safer and more convenient the walking environment becomes. Additionally, residents with lower salaries might have decided to walk to balance their expenses.

Further, there was a significant increase in the use of firewood and electric cookers during the economic crisis due to the scarcity of cooking gas. Some people attempted to switch to kerosene oil cookers, but the government lacked the funds to import it in addition to the scarce fuel and diesel. Moreover, those who purchased electric cookers were in for an unpleasant awakening when the government imposed lengthy power failures due to a lack of funds to buy fuel for generators.

According to study results, more than two-thirds of respondents have considered moving to another country either with their families or on their own. According to the International Red Cross, Sri Lanka’s economic crisis has led to an increase in cross-border migration activity through both regular and irregular channels (Societies 2022 ). Many Sri Lankans use unauthorized modes of transportation to travel to neighbouring nations such as India and Australia, which puts them in danger of being trafficked and detained. In addition, as people look for jobs abroad, there has been a rise in labour migration to the Middle East and Gulf nations. The Department of Immigration and Emigration reports that over 300,000 Sri Lankan passports were issued in the first half of 2022, compared to a total of 382,000 passports granted in the entire year of 2021 ( Department of Immigration and Emigration Sri Lanka ).

The primary drawback of the current study is the use of a self-reported questionnaire, which could result in actual data misreporting. Also, certain population categories have been overrepresented because of the online survey method. Owing to a higher proportion of survey respondents having a higher level of education, it is important to acknowledge that the study sample may not fully represent the general population. The significant percentage of participants with advanced education suggests that individuals with higher educational qualifications may hold distinct perspectives or have different experiences compared to those with lower educational backgrounds. Our online survey, however, was identical to others that have commonly been used. The fact that the survey was carried out at the peak time of the economic crisis was a strength of our study.

In general, the current economic crisis has altered the lifestyle behaviours of citizens. There was a reduction in alcohol intake and smoking during the crisis by nearly 80% and 60%, respectively. Prior to the crisis, many people travelled by private vehicles, although demand for public transportation and environmentally friendly modes of mobility such as walking and cycling increased throughout the crisis. Interestingly, compared to those residing in other districts and earning higher incomes, those with lower incomes and those who reside in the Colombo district reported longer walking times. Additionally, due to a lack of cooking gas, a significant increase in the use of electric and firewood stoves has been observed. The ongoing economic crisis has caused more than one-third of the population to consider moving.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ahmad S, Franz GA (2008) Raising taxes to reduce smoking prevalence in the US: a simulation of the anticipated health and economic impacts. Public Health 122:3–10

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ariizumi H, Schirle T (2012) Are recessions really good for your health? Evidence from Canada. Soc Sci Med 74:1224–1231

Baker TD, Baker SP, Haack SA (2011) Trauma in the Russian Federation: then and now. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 70:991–995

Article Google Scholar

Bhowmick S (2022) Understanding the economic issues in Sri Lanka’s current debacle. In: Understanding the economic issues in Sri Lanka’s current debacle: Bhowmick, Soumya. New Delhi, India: ORF, Observer Research Foundation. https://hdl.handle.net/11159/12457

Brinkman H-J, De Pee S, Sanogo I, Subran L, Bloem MW (2010) High food prices and the global financial crisis have reduced access to nutritious food and worsened nutritional status and health. J Nutr 140:153S-161S

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Bruggink J-W, de Goeij MC, Otten F, Kunst AE (2016) Changes between pre-crisis and crisis period in socioeconomic inequalities in health and stimulant use in Netherlands. Eur J Public Health 26:772–777

Central Bank of Sri Lanka (2022) On year-on-year basis, CCPI based headline inflation continuously increased to 29.8% in April 2022. Retrieved from https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/en/news/ccpi-based-inflation-in-april-2022 . Accessed 11 Nov 2022

Compton WM, Gfroerer J, Conway KP, Finger MS (2014) Unemployment and substance outcomes in the United States 2002–2010. Drug Alcohol Depend 142:350–353

de Goeij MCM, Suhrcke M, Toffolutti V, van de Mheen D, Schoenmakers TM, Kunst AE (2015) How economic crises affect alcohol consumption and alcohol-related health problems: a realist systematic review. Soc Sci Med 131:131–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.025

Department of Immigration and Emigration Sri Lanka. Retrieved 30th November from https://www.immigration.gov.lk/web/index.php?option=com_content&view=frontpage&lang=en&Itemid= . Accessed 30 Nov 2022

Dore AR, Adair LS, Popkin BM (2003) Low income Russian families adopt effective behavioral strategies to maintain dietary stability in times of economic crisis. J Nutr 133:3469–3475

Foscolou A, Tyrovolas S, Soulis G, Mariolis A, Piscopo S, Valacchi G, Anastasiou F, Lionis C, Zeimbekis A, Tur JA, Bountziouka V, Tyrovola D, Gotsis E, Metallinos G, Matalas AL, Polychronopoulos E, Sidossis L, Panagiotakos DB (2017) the impact of the financial crisis on lifestyle health determinants among older adults living in the mediterranean region: the multinational medis study (2005–2015). J Prev Med Public Health 50:1–9. https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.16.101

Fowsar MA, Raja NK, Rameez MA (2021) COVID-19 pandemic crisis management in Sri Lanka. slipping away from success. In Times of Uncertainty 401-422. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG

Galanis A, Botzoris G, Siapos A, Eliou N, Profillidis V (2017) Economic crisis and promotion of sustainable transportation: a case survey in the city of Volos, Greece. Transp Res Proc 24:241–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2017.05.114

Gerdtham U-G, Ruhm CJ (2006) Deaths rise in good economic times: evidence from the OECD. Econ Hum Biol 4:298–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2006.04.001

Herttua K, Mäkelä P, Martikainen P (2007) Differential trends in alcohol-related mortality: a register-based follow-up study in Finland in 1987–2003. Alcohol Alcohol 42:456–464

Jayawardena R, Kodithuwakku W, Sooriyaarachchi P (2023) The impact of the Sri Lankan economic crisis on medication adherence: an online cross-sectional survey. Dialogues Health 2:100137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dialog.2023.100137

Katulanda P, Wickramasinghe K, Mahesh JG, Rathnapala A, Constantine GR, Sheriff R, Matthews DR, Fernando SS (2011) Prevalence and correlates of tobacco smoking in Sri Lanka. Asia Pac J Public Health 23:861–869

Katulanda P, Ranasinghe C, Rathnapala A, Karunaratne N, Sheriff R, Matthews D (2014) Prevalence, patterns and correlates of alcohol consumption and its’ association with tobacco smoking among Sri Lankan adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 14:612. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-612

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lund Jensen N, Pedersen HS, Vestergaard M, Mercer SW, Glümer C, Prior A (2017) The impact of socioeconomic status and multimorbidity on mortality: a population-based cohort study. Clin Epidemiol 9:279–289. https://doi.org/10.2147/clep.S129415

Marmot MG, Bell R (2009) How will the financial crisis affect health? BMJ 338:b1314. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b1314

Men T, Brennan P, Boffetta P, Zaridze D (2003) Russian mortality trends for 1991–2001: analysis by cause and region. BMJ 327:964

Nolan A (2014) Economic and social rights after the global financial crisis. Cambridge University Press

Book Google Scholar

Papagiannakis A, Baraklianos I, Spyridonidou A (2018) Urban travel behaviour and household income in times of economic crisis: Challenges and perspectives for sustainable mobility. Transp Policy 65:51–60

Pereira P, Zhao W, Symochko L, Inacio M, Bogunovic I, Barcelo D (2022) The Russian-Ukrainian armed conflict will push back the sustainable development goals. Geogr Sustain 3:277–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geosus.2022.09.003

Quail R (Ed.) (2010) Lessons from the financial crisis: causes, consequences, and our economic future (Vol. 12). John Wiley & Sons

Ruhm CJ (2000) Are Recessions Good for Your Health?*. Q J Econ 115:617–650. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355300554872

Shehan S, Jayasinghe H, Dilshan B, Pieris T, De Silva D, Vidhanaarachchi S (2022) An efficient fuel management system to address the ongoing fuel crisis in Sri Lanka. Int J Eng Manag Res 12:259–266

Google Scholar

Societies (2022) Sri Lanka Emergency - Operation Update #1, DREF n° MDRLK014. https://reliefweb.int/attachments/6c3cb3a9-f90a-4c3e-8b77-29368a9ed000/MDRLK014OU1.pdf . Accessed 11 Nov 2022

Sooriyaarachchi P, Jayawardena R (2023) Impact of the economic crisis on food consumption of Sri Lankans: an online cross-sectional survey. Diabetes Metab Syndr 17:102786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2023.102786

Sooriyaarachchi P, Francis TV, King N, Jayawardena R (2021) Increased physical inactivity and weight gain during the COVID-19 pandemic in Sri Lanka: an online cross-sectional survey. Diabetes Metab Syndr 15:102185

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sooriyaarachchi P, Francis TV, Jayawardena R (2022) Fruit and vegetable consumption during the COVID-19 lockdown in Sri Lanka: an online survey. Nutrire 47:1–9

Souza LE de, Rasella D, Barros R, Lisboa E, Malta D, Mckee M (2021) Smoking prevalence and economic crisis in Brazil. Revista De Saúde Pública 55:3. https://doi.org/10.11606/s1518-8787.2021055002768

Suhrcke M, Stuckler D, Suk JE, Desai M, Senek M, McKee M, Tsolova S, Basu S, Abubakar I, Hunter P (2011) The impact of economic crises on communicable disease transmission and control: a systematic review of the evidence. PLoS One 6:e20724

Valkonen T, Martikainen P, Jalovaara M, Koskinen S, Martelin T, Mäkelä P (2000) Changes in socioeconomic inequalities in mortality during an economic boom and recession among middle-aged men and women in Finland. Eur J Public Health 10:274–280

World Medical Association (2014) World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. J Am Coll Dent 81:14–18

Zavras D, Tsiantou V, Pavi E, Mylona K, Kyriopoulos J (2013) Impact of economic crisis and other demographic and socio-economic factors on self-rated health in Greece. Eur J Public Health 23:206–210. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cks143

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all who supported in distributing the questionnaire. We also express our heartiest gratitude to all the participants for their contribution to this study during this difficult time.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions The authors declare that they received no funding for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Health and Wellness Unit, Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo, Colombo, Sri Lanka

Piumika Sooriyaarachchi

Faculty of Health, School of Exercise and Nutrition Sciences, Queensland University of Technology (QUT), Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo, Colombo, Sri Lanka

Ranil Jayawardena

Nawaloka Hospital Research and Education Foundation, Nawaloka Hospitals PLC, Colombo, Sri Lanka

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

PS and RJ conceived and designed the online survey questionnaire; distributed the questionnaire; PS analysed and interpreted the data; PS drafted the manuscript; RJ revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Piumika Sooriyaarachchi .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee, Nawaloka Hospitals Research and Education Foundation, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Consent to participate

Informed written consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Sooriyaarachchi, P., Jayawardena, R. Lifestyle changes during the economic crisis: a Sri Lankans survey. J Public Health (Berl.) (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-023-02030-z

Download citation

Received : 15 February 2023

Accepted : 09 July 2023

Published : 31 July 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-023-02030-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Economic crisis

- Transportation

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Review article

- Open access

- Published: 04 December 2020

Indigenous and traditional foods of Sri Lanka

- Sachithra Mihiranie 1 ,

- Jagath K. Jayasinghe 1 ,

- Chamila V. L. Jayasinghe 2 &

- Janitha P. D. Wanasundara ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7491-8867 3

Journal of Ethnic Foods volume 7 , Article number: 42 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

51k Accesses

16 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Indigenous and traditional foods of Sri Lanka inherit a long history and unique traditions continued from several thousands of years. Sri Lankan food tradition is strongly inter-wound with the nutritional, health-related, and therapeutic reasoning of the food ingredients and the methods of preparation. The diverse culinary traditions and preparations reflect multipurpose objectives combining in-depth knowledge of flora and fauna in relation to human well-being and therapeutic health benefits. Trans-generational knowledge dissemination related to indigenous and traditional food is now limited due to changing lifestyles, dwindling number of knowledge holders, and shrinking floral and faunal resources. Awareness on the relationship between non-communicable diseases and the diet has garnered the focus on traditional ingredients and foods by the consumers and major food producers in Sri Lanka. This review presents concise details on the indigenous and traditional foods of Sri Lanka, with scientific analysis when possible.

Introduction

Indigenous and traditional foods of Sri Lanka present a perfect blend of cultural diversity with human wisdom that has been evolved through generations in establishing a cultural heritage and an identity. In the Sri Lankan culture, food is treated with the highest gratitude, respect, and generosity, expressed by sharing and offering to fellow humans, animals as well as the divine powers. Sri Lankans love to share foods with neighbors, family, and friends; house visits are always accompanied with bundles of food items. Some foods and the preparation know-how are specialties of the locality. Trans-generational knowledge transmission of food and food ingredients is inter-woven with regular maintenance of healthy life, cultural legacy, and religious concepts of the ethnicities of the land and have been the key to sustain a traditional food culture in Sri Lanka; evidence are found in written literal work and archeological sources as well as folklore.

Archeological findings, ancient travelers’ records, and early world maps are living evidence for the significance of this island in geo-politics and sea trade since ancient times. Elements of Afro-Arabic, Central Asian, European, South-east Asian, and Oriental food cultures that followed with the trade activities, royal marriages, and invasions have been customized to align with the habits, the culture, and the palate of island inhabitants while keeping the indigenous and traditional food culture in a nutshell. A significant geographic differentiation can be seen in traditional foods aligning with the eco- and biodiversity of the island. Indigenous and Ayurveda medicine holds a strong base and provides recommendations with clear and defined identity on the ingredients, preparation methods, and consumption in order to maintain a healthy life while preventing and treating major diseases and minor ailments. Traditionally, the primary knowledge holders are the community elders (both male and female) and indigenous medical practitioners who are well versed about the local flora and fauna, their medicinal values, and the ingredients and preparations.

The present review describes the essentials of indigenous and traditional foods of Sri Lanka, for the first time, providing a perspective analysis in science, technology, and nutrition of food and preparations when possible. Ancient texts and books written on Sri Lanka by various authors and other published media and discussions with different individuals holding traditional knowledge were consulted in generating this condensed review.

Geographical and climatic perspective

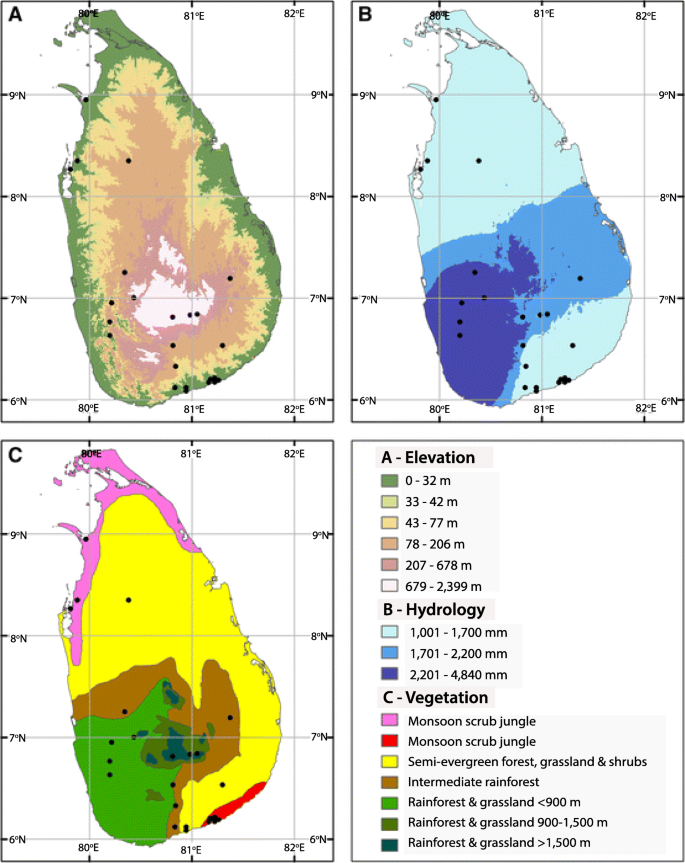

Geo-positioning and climate of the country are highly relevant to the available food sources and existence of various food traditions. Sri Lanka is a tropical island positioned between 5° 55' and 9° 51' North latitudes and 79° 42' and 81° 53' East longitudes in the south of the Indian peninsula. The island and area of 65,610 km 2 bears distinguishable elevation (Fig. 1 a; central highlands, plains, and the coastal belt), rainfall (Fig. 1 b; wet, intermediate, and dry zones), and vegetation (Fig. 1 c; closed rainforest, more open intermediate tropical forest, and open grassland) zones [ 1 ]. The terrain of the island is mostly low, flat to rolling plains with mountains in the South-central area. The island coastline is 1,340 km long and inland water bodies cover 2,905 km 2 . Several offshore islands account for 342 km 2 area. The island receives monsoonal, convectional, and depressional rains annually, with < 900 mm in the driest areas (North-western and South-eastern regions) to > 5000 mm in the wettest areas (Western slopes and Central highlands). Mean annual temperature (MAT) varies between 26.5 °C and 28.5 °C, with the altitudes > 1800 m marking MAT of 15.9 °C, and the coldest temperatures in January and the warmest temperatures in April and August [ 2 ]. Of the total land area, ~ 19% is arable, and agriculture accounts for ~ 44% of the workforce and 12% of the GDP [ 3 ].

Maps of Sri Lanka showing a Elevation map based on Digital Elevation Model, b Precipitation map showing Wet Zone, Intermediate Zone, and Dry Zone, and c Vegetation map ([ 1 ], with permission). Black circles in the maps indicate archeological and paleo-environmental sites of the island covered in the studies of reference [ 1 ]. Sri Lanka, formerly known as Ceylon is an island in the Indian Ocean, South-east of Indian subcontinent. Island terrain is primarily low, flat to rolling plain with mountains in the South-central interior. Island’s climate is tropical monsoon. The mountains and the South-western part of the country (wet zone) receive annual average rainfall of 2500 mm and the South-east, East and Northern parts of the country (dry zone) receive between 1200 and 1900 mm of rain annually. The arid North-west and South-east coasts receive the least amount of rain, 600 to 1200 mm per year. There is strong evidence of prehistoric settlements in Sri Lanka that goes back to ~ 125,000 BP

Crucial positioning in the middle of the Indian Ocean and to the extreme south of the Indian Peninsula together with the protective natural harbors and, floral and faunal richness have been the key elements that attracted many global travelers, explorers, and trading nations to this island. Ancient maps and manuscripts account the importance of harbor towns and cities of the island. The map by Claudius Ptolemy (second century CE) was the first to provide absolute co-ordinates of specific locations of the island. Many names referred by various nations identify this island: Taprobane (Greek), Serendib (Persian, Arabic), Simhaladvipah (Sanskrit), Ceilão (Portuguese), Ceylon (English), Thambapanni (Mahavamsa) and since 1972 the country declared Sri Lanka (Sinhala) or Ilankei (Tamil).

Food consumption patterns of pre- and proto-historic humans of Sri Lanka

The pre-historic man of Sri Lanka is known as the Balangoda Man ( Homo sapiens balangodensis ) belonging to the Pleistocene/Holocene epoch boundary in the geo-chronological scale [ 4 ], in which the Mesolithic period of archeological timescale coincides. The oldest human fossil evidence in South Asia (~ 45,000 to 38,000 calibrated years before present) were found in the rock shelters and caves scattered in all ecoregions of the island (Fig. 1 a, b, and c) [ 1 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. The archeo-zoological and archeo-botanical evidence along with the microlithic and osseous tools and other artifacts found in these rock shelters indicate that the nutritional needs of these early human inhabitants have been supported by a number of sources [ 1 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. These include a variety of small and large animals and plant sources found above and below ground, and in the aquatic environments. Material evidence dating back to 2700 BCE support the involvement of pre-historic inhabitants in plant material processing, plant domestication, and pottery manufacturing, and the transition from forager, hunter-gatherer to agricultural, a more sedentary lifestyle [ 1 , 5 , 8 , 9 ].

Foods of indigenous people

The Veddā (a.k.a. Aadi Vaasin , Wanniyala-eththo ) is a group of people with indigenous ancestry, ~ 10,000 in number now, and confined to inland isolated pockets extending from the Eastern and North-eastern slopes of the hill country and the Eastern and North-central parts of the country [ 10 ]. They inherit an ancient culture that values the interdependency of social, economic, environmental, and spiritual systems. The Great Genealogy/Dynasty or Mahāvaṃsa , an ancient non-canonical text written in the fifth century CE on the Kings of Sri Lanka (the first version covers from 543 BCE to 304 CE) records Veddā ’s origin dating back to the fifth to the sixth century BCE. Recent studies show that Veddā is genetically distinct from other populations in Sri Lanka [ 11 , 12 , 13 ] and most likely descends from early Homo sapiens who roamed the island. Hunting has been the mainstay of this group and skills still remain, using bow and arrows to hunt forest animals [ 14 ] and aquatic fish species that satisfy the animal protein supply. The hunter-gatherer lifestyle that Veddā subsisted on has now partly been replaced; they engage in crop cultivation to supplement grains and vegetables for food.

Traditionally, the Veddā group prepares meat and fish by direct roasting over wood fire, covering with hot ashes or smoking, and drying on a wooden rack [ 15 , 16 ]. Excess hunt is sun-dried or smoked to preserve for rainy seasons. Harvesting honey of various forest insects is a regular task and a group activity. Honey is for direct consumption and for meat preservation [ 17 ]. A sausage-like product, “ Perume ,” is an energy- and nutrient-dense preserved form of meat. Alternative layers of meat and fat consist this product with variations depending on the animal type (deer, venison) and parts (monitor lizard tail stuffed with fat from the sides of the animal, or clotted blood). Boneless game meat, roasted rice ( Oryza sativa ) flour, green chili ( Capsicum annuum ), cumin ( Cuminum cyminum ), coriander ( Coriandrum sativum ), and leaves of Asamodagam ( Trachyspermum roxburghianum) are formed into balls, batter coated with rice flour and deep fried in Bassia longifolia seed oil to make “ Mas guli ” or “ Kurakkal .” Present-day Veddā ’s food reflects the use of condiments, spices, herbs, salt, and lime juice similar to making curries. Changing laws in the country that ensures conservation and sustainability of wildlife has limited the hunting lifestyle and the food sources of Veddā group.

Tubers and yams of forest origin mainly Dioscorea species ( D. spicata , D. pentaphylla , and D. oppositifolia ) and less often Aracea plants (e.g., Arisaema leschenaultii ) roasted over direct fire is a carbohydrate source of the Veddā’s diet. Cultivated cereals such as rice, finger millet ( Eleusine coracana ), and maize ( Zea mays ) made into flour is for unleavened flatbread ( Roti ) or thick boiled flour paste ( Thalapa ) that accompany cooked smoked meat with gravy ( Ānama ) [ 18 , 19 ]. When available, cereal flours are supplemented with cycad ( Cycas circinalis) seed flour (sliced, dried, and ground) or Bassia longifolia flowers (dried and ground) for Roti and Thalapa . Various herbs, leafy vegetables, and unripe fruits of gourds and melons having medicinal and therapeutic properties are part of the regular diet. Among these, leaves of Cassia tora , Ipomoea cymosa , and Memecyclon umbellatum ; ripe wild tree fruits and berries such as Mangifera zeylanica , Nephelium longana , Hemicyclia sepiaria , Manikkara hexandra , Terminalia belerica , and Dialium ovoideum ; and wild mushrooms are integral. Transgenerational knowledge transfer on traditional systems for sourcing and sustainable harvesting practices of food, converting into safer ingredients (e.g., ways to reduce toxins and undesirable compounds while improving palatability, digestion, and safety), and effective preservation technologies has enabled harmonic balance between human-forest environment while sustaining nutrition and health status of the Veddā group.

History-related influences

Sri Lanka has a continuous written history. Stone scripts as early as ~ 250 BCE, ancient texts together with remaining palm ( Ōla ) leaf texts evidence the knowledge on sophisticated agricultural practices and food preparations that appreciate intricacies of health and nutrition basis of foods. Archeological and documentary evidence found in Sri Lanka support continuous inward migration and convergence of various foreign nations ensuring trade, governing power, and diplomatic relations resulting in multiethnic nature of the foods and food traditions of the island.

The first recorded food-related hospitality is described in Mahāvaṃsa (Chapter VII), about a special incidence happened in fifth century BCE, between the noblewoman Kuweni and Indian prince Vijaya and crew. This Aryan language–speaking group of 700 from Northern India landed in the north-west coast of the island (coinciding with the passing away of lord Gautama Buddha ) was served with special rice preparations, sweets made from rice, rice flour, jaggery (a traditional sweetener [ 20 ]), honey, and a variety of local fruits [ 21 , 22 , 23 ]. Reintroduction of Buddhism in third century BCE (250 to 207 BCE) and subsequent invasions, occupancies, royal marriages between foreign nations had a profound impact and significant contribution to the island food culture. Several nations including, Arabic, Roman, Oriental, Central Asian, and Indian in the early centuries for internal and foreign trade, and the domination of three European nations (Portuguese, Dutch, and English) in the island governance since 1505 AD had profound influence on Sri Lankan culinary tradition and style. Buddhism and Hinduism that existed since ancient times with the later introduction of Islam and Christianity influenced the religious aspects of food culture, traditions, and taboos. Low consumption of meat, particularly beef, even today may have a religious influence. Similar to the cultural practices and languages, all these foreign influences enriched Sri Lankan food culture than taking presidency over in converting to a microcosm of another culture or a nation.

Food and traditional medical systems

Ingredients and preparation processes of traditional Sri Lankan foods have a strong relationship with maintenance of general health and prevention of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) of the consumer in addition to providing required nutrition. Today, the deeply rooted indigenous medical system ( Hela Wedakam since the time of multi-talented local ruler Rāvana , time unknown) co-exists with the Ayurvedic since pre-Aryan civilization ( Siddha and Unani ) and the Western medical system introduced during the colonial era. Although taste and appeal are the key, the indigenous medical system emphasizes the use of ingredients and preparations that suit general wellbeing, physiological condition, involved activities, and disease conditions of the consumer, and the environment and climate of the consuming location as primary considerations. Indigenous medicine–based healing system focuses on mental and physical fitness simultaneously, bearing some similarities with Ayurveda but diverges in practice and constituents. Maintaining harmony between the human being and nature and integration of foods that nature provides in keeping the balance of bodily systems are the fundamentals of the indigenous medical system. Avoidance of extremes and selective use of opposites of “hot/heaty” and “cold/cooling” foods is embedded in indigenous and Ayurveda systems [ 24 ].

Foods and food preparation

Being a predominantly agrarian society, food culture and traditions in Sri Lanka have evolved with the cultivated crops, daily activities, beliefs and the seasonal nature of food sources. A typical traditional meal comprises a carbohydrate source/s (grains or grain products, tubers, or starchy fruit) and accompaniments providing protein, lipids, fiber, and micronutrients. Protein sources are animal or plant (e.g., cashew nut, Anacadia occidentalis ) based and lipids are mainly from plants, especially from coconut ( Cocos nucifera ) or sesame ( Sesamum indicum ). A variety of fruits, pods, seeds, leaves, tubers, stems, and flowers of native plants are included in the meal as various preparations. Ripe local fruits, buffalo milk curd with a sweetener, and simple sweetmeats are the common dessert options. A “Chew of Betel” comprised of betel leaves ( Piper betle ) and arica nuts ( Areca catechu ) with tropical aromatic spices such as cardamom ( Elettaria cardamomum ) finishes the traditional meal. The diverse nature of sources and preparations makes the plate of a Sri Lankan meal comprised of a range of colors, tastes, and flavors. When eating food, usually fingers are used, particularly the right hand. Each bite of food is a mix of all food items in the plate that is squeezed well and mixed with fingers to combine all flavors and tastes.

Grains and grain products

Rice and rice-based products.

Rice is the staple and the main carbohydrate source of Sri Lankan diet since ancient days. Cultivation of paddy and production of rice has been central to societal, cultural, religious, and economic activities of the island [ 17 , 25 ]. The Cascade Tank-Village System of Sri Lanka is a recognized Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System that provides water needs for water-intensive rice cultivation securing food supply and creating a resilient ecosystem while preserving biodiversity and associated traditional knowledge [ 18 , 26 ].

The indica varieties of rice are the primarily cultivated types in Sri Lanka. Among the traditional rice varieties, eating quality traits and grain milling characteristics, e.g., small round grains, thin long grains, pigmented (red-brown), fragrant, etc. are equally important considerations as agronomic performances. The low-protein levels (average value of 7.7% compared with 12.4% in traditional rice varieties) and high glycemic index (GI) [ 27 ] of modern rice varieties is a concern because of the considerable daily intake. In 2016, the per capita consumption of rice including rice-based products was ~ 114 kg per year providing 45% total caloric and 40% total protein requirement of a Sri Lankan [ 28 ]. Increasing science-based evidence and awareness of health benefits of the major and minor nutrients of traditional rice varieties have boosted production of indigenous varieties making them available for the average consumer [ 27 , 29 ].

Traditional rice preparations

Processing of paddy into edible rice grains, once a household task, is now an industrial operation. Unpolished rice and red-pigmented rice are considered superior in health benefits since ancient times. Parboiling has been in practice since time unknown and can be done for indica varieties. Boiling in water allowing grains to absorb all or rarely draining excess water out makes rice ready for consumption. Simple additives besides salt, vegetable oil, and ghee, turmeric ( Curcuma longa ), curry leaves ( Murraya koenigii ), rampe leaves ( Pandanus amaryllifolius ), cardamom, and/or nutmeg ( Myristica fragrans ) are cooked with rice depending on the choice of the consumer. These additives bring color, aroma, and flavor to rice while impregnating with water-soluble components having antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. Complex rice preparations include incorporation of different fat types, dairy products, coconut milk, honey, vegetables, and fruits. These practices essentially enhance nutrient density, flavor, and taste of cooked rice; such are central in festivities, religious, and spiritual offerings. A meal portion of warm cooked rice with the accompanying curries, salads, and chutneys when wrapped in mildly withered (on direct heat to be pliable) banana ( Musa spp.) leaves infuses leafy aroma to the content. This traditional meal presentation is common for packing meals and adorned by all regardless of age or social status.

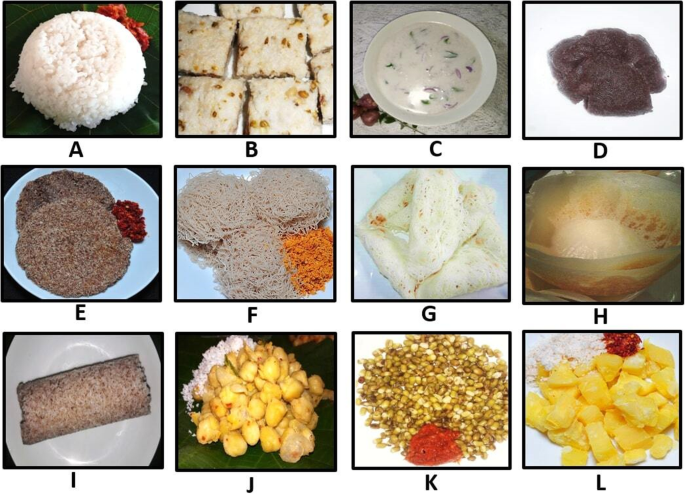

Milk rice is a specialty in Sri Lankan food culture (Table 1 , Fig. 2 a). This preparation of non-parboiled rice cooked with coconut milk (rarely with dairy) can be a regular meal item adored by consumers of all ages and social levels. Milk rice of various forms takes a central place in the traditional ceremonies, devotions, and festivities. Elaborative milk rice preparations include the addition of mung bean or green gram ( Vigna radiata ) (Fig. 2 b; cereal-pulse blends complement in improving essential amino acid profile and recommended by the FAO), sugarcane ( Saccharum officinarum ) jaggery , or grated coconut infused with concentrated sap of palm inflorescence (treacle) [ 22 , 30 ].

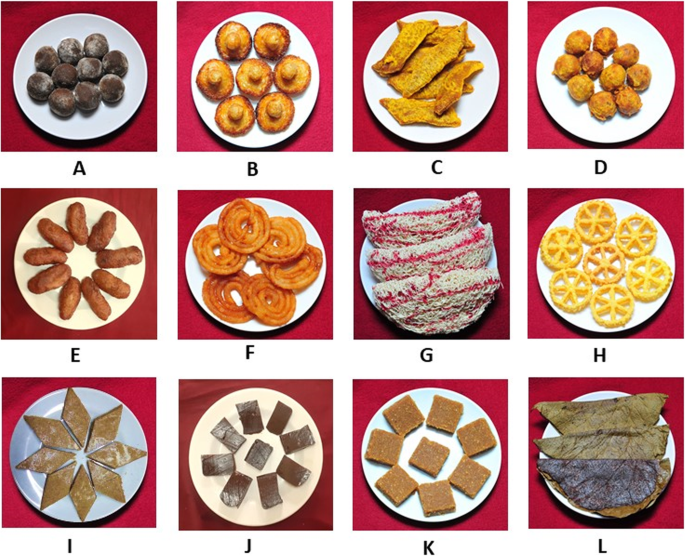

Starchy staples of traditional Sri Lankan food items and meals are based on cereals, pulses and/or tubers. Some of the preparations do not show locality dependence but alternative cereals to rice is used according to abundance of the growing areas. A meal is comprised of a main food item and accompaniments which are usually paired with the food product. Accompaniments could be hot-savory and/or sweet. Fresh coconut kernel is used in a variety of ways mixed with cereal flour or in preparation of the accompaniments. a Milk rice with accompanying Lunumiris , b Milk rice with mung bean accompanied with Lunumiris , c Diyabath preparation, d Thalapa made of finger millet flour, e Roti made of rice and finger millet flour with Lunumiris , f String hoppers or Indiáppa with Sambōla , g Laveriya - sweetened string hoppers, h Plain Hoppers or Āppa , i Pittu made of red rice flour, j Boiled chickpea with fresh scraped coconut, k Boiled mung bean with Lunumiris , l Boiled cassava roots with fresh scraped coconut and Lunumiris

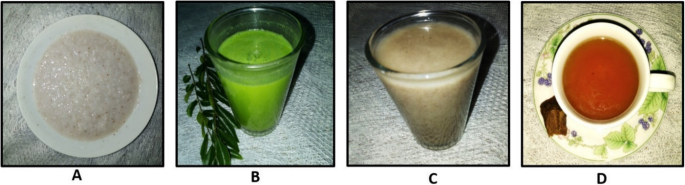

Certain rice preparations are household remedies for various ailments. Leftover cooked rice of the previous night (no refrigeration) without reheating is a highly favored breakfast item that delays hunger. Diyabath made with leftover cooked rice (Table 1 , Fig. 2 c) can lower gastric acidity [ 31 ]. Mixing fresh cow’s milk or curdled water buffalo milk with cooked rice enhances medicinal value and consumed by the locals where such milk products are abundant. A porridge-style or gruel preparation of roasted, non-parboiled rice is an easily digestible, energy-dense food for individuals recovering from any sickness (Fig. 3 a). Although indica rice varieties have high amylose content (23–31%) in starch that resists digestion and pose low GI, longer cooking time, and excess water in porridge preparation can result in a high degree of starch gelatinization that increases digestibility [ 32 ]. Rice porridge can be enriched with protein and fat of coconut milk, sweetened with palm jaggery or treacle, or spiced with onion ( Allium cepa ), ginger ( Zingiber officinale Roscoe), and garlic ( Allium sativum ), with or without various pulverized/juiced green leaves having medicinal value (Fig. 3 b). Even today, the green leaves popular for porridges are Aerva lantana , Asparagus racemosus , Cardiospermum halicacabum , Centella asiatica , and Vernonia cineria which are known for their medicinal and therapeutic value in providing blood sugar controlling, anti-inflammatory, and/or blood-purifying effects according to indigenous and Ayurveda medical systems.

Beverages based on leaves, flowers, stems, bark or root of plants and trees that are known for various health benefits are part of traditional foods of Sri Lanka. A creamy, smooth porridge-style beverage is prepared with cooked cereals or cereal flours and with fresh coconut milk and pulverized plant materials or their water extract. Herbal teas are prepared as water infusion or by boiling with water. Usually, herbal beverages are accompanied with palm jaggery . Herbal beverages prepared with cereals could be a breakfast meal due to their caloric-richness. Water infusions and extracts are consumed as herbal teas in any time of the day. a Plain rice porridge, b Rice porridge made with extract of plant leaves or Kola Kenda , c Porridge made with finger millet flour, d Herbal tea made with flowers of bael fruit

The recipes and notes maintained by chef clans for royal families of pre-colonial era show the use of various vegetable oils and animal fats in rice preparations. The sacred food offering to the Temple of Tooth Relic in Sri Lanka includes a wide range of traditional food items about 32 in number at a time, which is an honorable task these chef clans performed and still maintained [ 33 ]. Present-day rice preparations in Sri Lanka reflect the influence of several ethnic cultures. Mixing cooked rice with tempered vegetables, especially carrots, leeks, and green peas, and garnishes such as cashew, raisins, meat, and egg in making fried rice could be a convergence of British and Oriental food preferences. Biriyani -style rice of Northern or Central Asian culinary tradition remains with a selection of spices and oil (vegetable oil replaces ghee) that are preferable to the local palate. The Lamprais is rice cooked with flavored oil and lumped together with shellfish-based fried chutney, curried plantains, and meat (poultry, beef, or mutton) and has Dutch influence.

Rice flour-based preparations

Traditionally, rice flour is prepared either by pounding grains (dehusked grains soaked and drained) in a wooden or stone mortar with a wooden pestle or grinding between two flat stone slabs which is now replaced by commercial-scale flour mills or home-scale electric grinders. Flour particle size is controlled by sieving with different mesh sizes.

Gruels ( Thalapa , Kanji ; Fig. 2 d), unleavened flatbreads ( Roti ; Fig. 2 e), string hoppers ( Indiāppa ; Fig. 2 f), hoppers ( Āppa ; Fig. 2 h), and Pittu (Fig. 2 i) that are made primarily from rice flour comprise the main meal item in the traditional diet and consumed with suitable accompaniments (Table 1 ). Flours of other grains and plant materials are combined depending on the product. Some of these food products are found in the South Indian food traditions. Mild fermentation, heat denaturation, and/or gelatinization of starch and protein of grain flours [ 34 , 35 ] during steaming (moist–heat treatment) of the wet pastes or roasting of flour slurries create the unique structures, textures, and tastes of these products.

Other cereals and pulses

Various grains requiring far less water than rice to grow are common in low-rainfall seasons and non-irrigating areas and replace rice in the meals.

Grains of finger- ( Eleusine coracana ), proso- ( Panicum miliaceum ), foxtail- ( Setaria italica ), and kodo- ( Papsalum scorbiculatum ) millets and maize are primarily converted into flour for various products (Figs. 2 b, d, e, j, k and 3 c, Table 1 ). Boiled maize cob is a popular snacking item and now a street food. Incorporation of wheat flour to the Sri Lankan food culture may be since the Portuguese invasion, now a sought-after ingredient for many flour-based foods [ 19 ]. Depending on the availability, flours of cycad seeds or Bassia longifolia dry flower supplement the grain flour. Hypocholesterolemic and hypoglycemic effects of cycad seed flour have been reported [ 36 ]. Water lily ( Nymphaea pubescens ) seeds harvested from large water bodies where they grow naturally are prepared similar to rice and prescribed for diabetic patients [ 37 ].

Pulses and legumes

Mung bean and black gram ( Vigna mungo ) are common in rain-fed Chena cultivation (slash-and-burn cultivation method) and contribute to traditional diet and food products. Cowpea or black-eyed peas ( Vigna unguiculata L. Walp), white or red skin, was popularized during the Green Revolution for intercropping. Horse gram ( Macrotyloma uniflorum ) has well-recognized medicinal properties [ 38 ] and included in meals in various ways. Pigeon pea ( Cajanus cajan ) whole or split (dhal) is for curries and fried/roasted snacks. Chick pea ( Cicer arietinum , both Kabuli and Desi) and lentil ( Lens culinaris , red and green, Mysoor dhal) have been introduced after 1977 through the trade relationships with India [ 39 ]. Boiled whole grain pulses garnished with salt, coconut pieces, red chilies, and/or onion makes a simple meal (Fig. 2 j, k). Curried red lentil has become a necessity in present-day Sri Lankan meals without limits of consumer income, type of occasion, or the social class. In 2011, lentil comprised > 70% of the average monthly per capita consumption of pulses amounting to 671 g/person/month [ 40 ].

Accompaniments

Various preparations of animal and plant sources accompany the carbohydrate staple of the traditional meal. These accompaniments are prepared as a thin gravy ( Hodda ), sour curry ( Ambula ), thick gravy ( Niyambalāwa ), mildly cooked salad ( Malluma ), deep fried ( Thel Beduma ), or dry roasted ( Kabale Beduma ). Coconut milk, grated coconut, coconut (or sesame) oil, and a variety of herbs and spices are essential ingredients in these preparations [ 17 ]. Some of these accompaniments are paired with main meal items. For example, milk rice goes well with Lunumiris , and Sambōla with boiled tubers or jack fruit. Similarly, some of the food items have preferred meal of the day, and physiology or health condition of the consumer depending on the health attributes of the source material, e.g . , mung bean usually does not accompany the nighttime meal or a person suffering from the common cold.

Herbs and spices

Various herbs and spices add flavor while prolonging product shelf life. Almost all the herbs and spices used in traditional Sri Lankan cooking have reported antifungal, antimicrobial, bacteriostatic, fungicidal and/or fungistatic properties, or pH-lowering ability and medicinal value such as anti-inflammatory and anti-diabetic [ 41 , 42 ].

Turmeric, the rhizome of Curcuma longa L. is an essential ingredient that gives unique yellow color and subtle flavor to Sri Lankan curries and rice preparations. Heat-blanched turmeric rhizome is dried and used as a powder or a paste. The main active ingredient, curcuminoids possess cardioprotective, hypo-lipidemic, antibacterial, anti-HIV, anti-tumor, anti-carcinogenic, and anti-arthritic activities [ 43 ].

The hot pungent taste and flavor of traditional dishes are primarily from ginger and black pepper ( Piper nigrum L.) besides several hot chili pepper varieties. Oriental/brown ( Brassica juncea ) and black mustard ( B. nigra ), fenugreek ( Trigonella foenum-graecum ), cardamom, nutmeg, cloves ( Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & L.M. Perry) provide a range of flavors and aroma in the traditional dishes. The dried husk of Garcinia gummi-gutta (L.) Roxb. (Gambooge, formerly G. cambogia ), and the flesh of ripe tamarind ( Tamarindus indica (L.) pods give a tarty note and increase the viscosity of the medium. The lemons ( Citrus limon ), limes ( Citrus aurantiifolia ), and fruits of Averrhoa bilimbi (Oxilidacea; Bilin ) are used for sour, tangy taste notes. The bark of cinnamon ( Cinnamomum zeylanicum ), Moringa ( Moringa oleifera ), and Terminalia arjuna are used in various preparations. Dry spices are used as whole, pieces, powder, or a wet paste. The traditional spice base ( Thuna-Paha ) is quite distinct in flavor and comprises either three ( Thuna ) seeds (coriander, fennel, and cumin) or five ( Paha ) aromatic spices (cinnamon, cardamom, turmeric, cumin, and curry leaves) together. Combinations and pre-treatments such as dry roasting create variations in the appearance and taste in the final spice preparation.

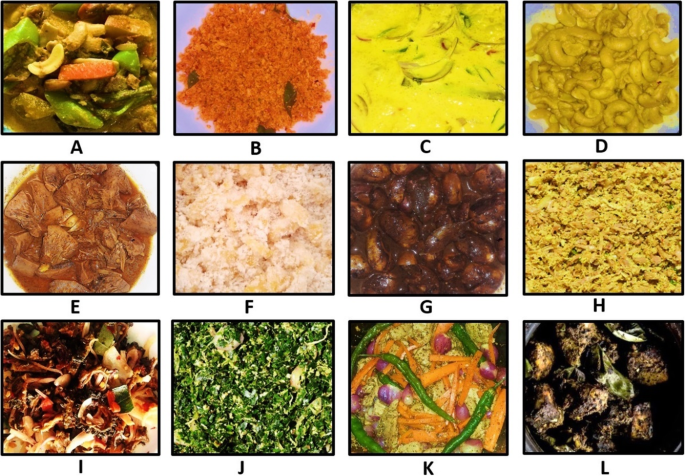

Preparation types

The variations of curries could be with a thin or thick gravy, moist without a gravy, white/yellow, red, black, sour, sweet, bitter, or hot-pungent. White curries are made pungent with immature green chili, garlic, ginger, or ground black pepper. Red curries contain a considerable amount of red chili paste/powder with a few other spices. Black curries are prepared with dark roasted spices, especially coriander, fennel, and cumin [ 44 ]. Dry gambooge gives dark, brown-black color to the final preparation. Coconut milk, buffalo milk, or water is the base for gravy while roasted rice flour (bland, roasted), soaked and ground mustard (pungent), and ripe tamarind pulp (sour) are the primary thickeners. A thin spiced gravy made with ground coriander, cumin, black pepper, red chili, curry leaves, and garlic is Kāyan hodda or Thambum hodi ; an appetizer and a remedy for various ailments including stomach disorders, reducing blood cholesterol, and for post-confinement mothers. Seven different plant items curried together ( Hath Māluwa , Fig. 4 a) is a must in the traditional New Year (based on the movement of sun and constellations, and the arrival of spring in April) menu that accompanies milk rice and also for specific spiritual devotions. It is a macro- and micro-nutrient-dense plant-based dish made of fruits (e.g., squash), flowers (e.g., pumpkin Cucurbita maxima ), green leaves, nuts (cashew, immature coconut), pods (e.g., long bean Vigna unguiculata or winged bean Psophocarpus tetragonolobus ), seeds (e.g. pulses, jackfruit seeds), and tubers that can accompany any meal. Ingredient choices depend on local availability. Dried fish is optional [ 21 ].

Accompaniments are essential in the typical Sri Lankan meal plate. They are prepared with animal or plant sources and complete the main meal with starchy staple such as rice and rice flour-based food products. Accompaniments are prepared in various ways and consistencies. These accompaniments add protein, fats, dietary fiber and micronutrients and complete the nutrient package that the meal provide. Condiments and spices that are added and the way of preparation give a range of colors, flavors and taste while improving the eating satisfaction of the food. a Hath Maluwa made with seven ingredients, b Sambōla , c Kiri Hodi , d Curried cashew, e Curried immature jackfruit, f Boiled mature jackfruit perianth with scraped coconut, g Curried jackfruit seeds, h Bread fruit Malluma , i Fried bitter melon salad, j Green leaf Malluma , k Traditional Sri Lankan pickle, l Dry sour fish curry ( Ambulthiyal )

Oilseeds, nuts, and other seeds

Plant oils are preferred over animal fats in regular food preparations. The use of clarified butter ( ghee ) is limited to infuse flavor and in devotion preparations. Coconut, the most sought-after oil-rich seed, is integral to the island’s food culture since time unknown. Virtually, almost all parts of the mature coconut tree are utilized in a range of products for sustaining human life providing food, medicine, construction materials, decoration pieces, animal feed, and fuel. Coconut kernel fresh or dried, the water of the fruit, and inflorescence sap are all direct foods or food ingredients. The liquid inside the immature coconut drupe is rich in electrolytes and sugars and considered the most natural drink after water. Fresh coconut kernel, finely grated, is an accompaniment to starchy staples. A spicy salad ( Sambōla , Fig. 4 b) is made with fresh scraped coconut, onion, chili, lemon, and salt. Such spicy coconut salad with thinly cut green leaves, starchy items such as pulses, tubers, breadfruit ( Artocarpus altilis ; Del ) or jackfruit ( Artocarpus heterophyllus ; Kos ) cooked together makes Malluma , a macro- and micronutrient-rich food. The water extract of mature coconut kernel or “coconut milk” is rich in protein and oil, an essential ingredient in Sri Lankan curries and gravies. Mildly cooked (near boiling) coconut milk with salt, turmeric, green chili, shallots, curry leaves, pandanus leaves, and lime juice makes Kiri Hodi (Fig. 4 c) a versatile accompaniment for any meal. Mechanical pressing of dry mature coconut kernel produces oil for cooking or for lighting fuel. The pleasant nutty aroma and almost bland flavor of coconut oil make it a sought-after oil for deep frying. Oil extracted from fibrous residue is a filler in certain sweets or for animal feed.

Sesame oil obtained from mechanical pressing is valued for its medicinal properties and a popular food oil among the Tamil ethnic group. Whole seed is adorned in traditional sweetmeats and vegetable preparations [ 33 ]. Groundnut/peanut ( Arachis hypogaea ) oil is not traditional in Sri Lankan food but the whole seed is a cheaper alternative to cashew in sweetmeats. Roasted or oil tempered mature groundnut and boiled immature groundnut are popular snacks. Cashew takes a special place in Sri Lankan food culture. Mature cashew is a popular snack and tender or mature nut is used in various preparations. Curried mature/tender cashew (Fig. 4 d) is an energy-dense (48.3% lipids, 20.5% protein, ~ 4% dietary fiber and free sugars) vegan dish [ 45 , 46 ] and essential ingredient for the Hath Māluwa .

Tubers, roots, and their products

Various tubers and roots (yams) satisfy carbohydrates in the Sri Lankan diet. The edible species of Dioscorea and Colocasia are the most popular. Tubers of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (elephant-foot yam), Dioscorea alata , Dioscorea bulbifera , Dioscorea sativa , and Typhonium trilobatum (Bengal arum) are consumed since historical times [ 30 ]. Arrowroot ( Maranta arundinacea ), cassava/tapioca ( Manihot esculenta Crantz), sweet potato ( Ipomoea batatas ), and red-colored Canna discolor may be introductions by the Portuguese [ 47 ]. Potato ( Solanum tuberosum ), a popular root vegetable, has been introduced by the British ~ 1850 [ 48 ].

Yams boiled in water with or without salt accompanied by grated fresh coconut and Lunumiris or Sambōla makes a meal (Fig. 2 l). Whole yams are stored in dry conditions such as sand pits for off-seasons. Thinly sliced yams are sundried and make into flours for supplementing roti and gruels.

Fruits and vegetables and their preparations

The traditional meals comprise a wide range of plant materials of different species prepared in a variety of ways. Pre-treatments such as steaming, sun drying, and soaking in salt or acidified water are practiced for some plant items as they contain potentially harmful compounds and/or enzymes that can release toxic compounds; e.g., alkaloids, cyanogenic glycosides that release hydrocyanic acid [ 17 ].

Two Moraceae trees, jackfruit, and breadfruit found ubiquitously in the island provide many edible components. Jackfruit, a multiple fruit that grows in the tree trunk, is the largest fruit known; the achenes with fleshy perianth covering the seed comprise a fruit. Both perianth and seed are edible and record significant nutritional, phytochemical, and medicinal value [ 49 , 50 , 51 ]. All developing stages and components of the multiple fruit are edible, e.g., inflorescence, young fruit, mature starch-rich fleshy perianth, starch-rich seed, and perianth of the ripe fruit. The young fruit ( Polos ) is considerably high in phenolic compounds and dietary fiber and processed as a vegetable that provides several health benefits (Fig. 4 e). These various jackfruit components and preparations are enjoyed regardless of age, social status, or physiological condition of the consumer. The starchy perianth (~ 25% carbohydrates) of one jackfruit provides a meal for several individuals. The simplest preparation is the small cut pieces of mature perianth boiled in water with salt until soft. Popular accompaniments are curried meat, fish or dry fish, and grated coconut kernel or Sambōla (Fig. 4 f). Low GI (< 55%), and high levels of dietary fiber and slowly available glucose (30%) have been reported for such meals [ 51 ] . Starch-rich jackfruit seed is a good source of fiber, protein and vitamins [ 52 ], makes an appetizing food when boiled, roasted, or curried (Fig. 4 g). When ripe, the starchy perianth becomes a fragrant, sweet-tasting dessert fruit either with soft, melting pulp ( Wela ) or firm, fleshy pulp ( Waraka ).

The mature breadfruit is rich in starch and considered a “heaty food.” The food preparations are more or less similar to jackfruit and the curried or Mallun preparations accompany rice (Fig. 4 h). The reduction in glucose absorption upon breadfruit consumption is linked to its fiber components [ 53 ].

Various types of gourds (snake, ridge, bitter, bottle), squashes, melons, beans (long, French, winged, broad) are popular traditional vegetables. Health benefits and medicinal properties of the edible plant parts are serious considerations when incorporating in a meal than their taste. For example, although tastes bitter, the bitter melon/gourd ( Momordica charantia , Fig. 4 i) is a very popular vegetable for curries and salads. The ability of M. charantia to control blood glucose levels in type 1 and type 2 human diabetes is supported by traditional medicine and scientific research [ 54 , 55 ].