Work engagement and employee satisfaction in the practice of sustainable human resource management – based on the study of Polish employees

- Open access

- Published: 28 March 2023

- Volume 19 , pages 1069–1100, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Barbara Sypniewska ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8846-1183 1 ,

- Małgorzata Baran ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8081-9512 2 &

- Monika Kłos ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0663-0671 3

30k Accesses

15 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Sustainable human resource management (SHRM) views employees as a very important resource for the organisation, while paying close attention to their preferences, needs, and perspectives. The individual is an essential element of SHRM. The article focuses on analyzing selected SHRM issues related to the individual employee's level of job engagement and employee satisfaction. The main objective of our study was to identify individual-level correlations between factors affecting employee satisfaction, such as: workplace well-being, employee development, employee retention, job engagement, and employee satisfaction. Based on the results of a systematic literature review, we posed the following research question: is there any relation between factors affecting employee satisfaction (employee workplace well-being, employee development, employee retention, work engagement) and employee satisfaction in the SHRM context? To answer the research question, we have conducted a quantitative study on the sample of 1051 employees in companies in Poland and posed five hypotheses (H1-H5). The research findings illustrate that higher level of employee workplace well-being (H1), employee development, (H2), employee retention (H3) was related to higher level of employee engagement (H4), which in turn led to higher level of employee satisfaction. The results show the mediating role of employee engagement in the relationship between workplace well-being, employee development, employee retention, and employee satisfaction (H5). The presented results contribute to the development of research on work engagement and job satisfaction in the practice of SHRM. By examining the impact of individual-level factors on job satisfaction, we explain which workplace factors should be addressed to increase an employee satisfaction and work engagement. The set of practical implications for managers implementing SHRM in the organization is discussed at the end of the paper.

Similar content being viewed by others

Work–Life Balance: Definitions, Causes, and Consequences

Employee Engagement: Keys to Organizational Success

Effect of green human resource management practices on organizational sustainability: the mediating role of environmental and employee performance

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sustainable human resource management (SHRM) is of great importance for implementing sustainable development principles in an efficient and effective way. SHRM strategies lay the foundations to achieve it by raising employee awareness and forming desirable pro-social and environmental attitudes (Bombiak, 2020 ; Sharma et al., 2009 ).

The inclusion of the concept of sustainability in the management of organisations is a consequence of institutional pressures that have forced significant changes in this area as part of the drive for social acceptance (Lopez-Cabrales & Valle-Cabrera, 2020 , p.1; Meyer & Rowan, 1977 ).

The term sustainability has different meanings depending on the perspective from which it is examined. The Resource Based View (RBV) inscribes the term in the strategic analysis of business, in relation to competitiveness in economic terms, and from an ecological perspective, in the environmental impact of the activities of various institutions (Lopez-Cabrales & Valle-Cabrera, 2020 ). However, the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) gives a definition of sustainability that refers to an organisation's activities and development in such a way that, while meeting the needs of the present, they do not endanger the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (Lopez-Cabrales & Valle-Cabrera, 2020 , p.1; Ehnert, 2009 ; Barney, 1991 ).

From a strategic point of view, the human aspect is essential to build an effective and healthy organization (Siddiqui & Ijaz, 2022 ; Järlström et al., 2018 ; Cleveland & Cavanagh, 2015 ). Sustainable HRM views employees as a very important resource for the organisation, while paying close attention to their preferences, needs, and perspectives. SHRM activities are carried out with the aim of improving organisational performance by enabling the development of long-term relationships with employees. It follows that sustainable HRM demonstrates in companies a path of organisational development that is based on human development (Lestari et al., 2021 ; Indiparambil et al., 2019 , p. 67; Cleveland & Cavanagh, 2015 ;).

Companies that are committed to their employees receive their work engagement in return. Organisations where HRM takes care of employees and their health retain more engaged, satisfied, and productive employees, with good overall health and well-being (Siddiqui & Ijaz, 2022 ; Sheraz et al., 2021 ; Indiparambil et al., 2019 , p. 67;Cleveland & Cavanagh, 2015 ).

Many authors argue that HR sustainability requires a focus on positive human/social outcomes identified at the individual, organizational, and societal level (Browning & Delahaye, 2011 ; Donnelly & Proctor-Thomson, 2011 ; Ehnert, 2009 ; Wells, 2011 ). The sustainable HRM seeks to achieve positive human outcomes by implementing sustainable work systems. Thus, it facilitates employees’ work-life balance without compromising performance (Indiparambil, 2019 ; Järlström et al., 2018 ). The sustainable HRM organisational practice manifests itself in employee’s commitment, employee’s satisfaction, and engagement (Chen & Chen, 2022 ; Parakandi & Behery, 2015 ). It is emphasized that by attracting and retaining talent, developing employee skills, and maintaining a healthy and productive workforce, SHRM practices in an organisation also affect employee satisfaction (Macke & Genari, 2019 ; Ehnert, 2006 ).

The article focuses on analyzing selected SHRM issues related to the individual employee's level of job engagement and employee satisfaction.

The main objective of our study was to identify individual-level correlations between factors affecting employee satisfaction, such as workplace well-being, employee development, employee retention, job engagement, and employee satisfaction.

The existing state of knowledge in the field of SHRM in the context of the individual employee, examined through a systematic literature review, has shown that there are current cognitive research gaps:

The organizational perspective dominates the research of SHRM, while a research gap has emerged in terms of research at the individual level in the literature.

The employee satisfaction in the context of SHRM has not been sufficiently studied in the literature.

Little research has been devoted to humanity in a sustainable work environment.

In particular, there is a lack of research focused on the relationship between employee workplace well-being, employee development and retention, and all those related to employee satisfaction and engagement in a sustainable work environment.

There is no such research (examining SHRM from the perspective of employees) conducted in Poland.

Based on the results of a systematic literature review, we posed the following research question: is there any relation between factors affecting employee satisfaction (employee workplace well-being, employee development, employee retention, work engagement) and employee satisfaction in the SHRM context? To answer the research question, we have conducted a quantitative study on the sample of 1051 employees from companies in Poland. We formulated the following hypotheses:

H1: Employee workplace well-being positively correlates with employee satisfaction.

H2: Employee development positively correlates with employee satisfaction.

H3: Employee retention positively correlates with employee satisfaction.

H4: Employee engagement positively correlates with employee satisfaction.

H5: Employee engagement mediates the relationship between workplace well-being, employee development, employee retention, and employee satisfaction.

The article presents the theoretical framework of the SHRM concept along with the research model (theoretical chapters). Section 3 is devoted to the methodological approach description. Section 4 contains the research sample characteristic, procedures for data analysis description, and study results presentation. The end of the paper is focused on conclusions with a discussion of the implications that follow from the results and paper limitations with directions of further scientific research.

The presented research results contribute to the development of research on work engagement and job satisfaction in the practice of SHRM. Firstly, by examining the impact of individual-level factors on job satisfaction, we explain how to motivate employees and which factors at work to focus on in order to increase employee satisfaction and work engagement.

Another of our contributions is a deeper understanding of the mediating role that employee engagement plays in job satisfaction. Our results showed that engagement and its dimensions mediate the relationship between individual factors (employee development well-being, retention, overall commitment) and job satisfaction.

Finally, our contribution is the set of practical implications for managers implementing SHRM in the organization, discussed at the end of the paper.

Theoretical framework

The very term sustainable HRM has been used for more than a decade. The literature is fragmented, diverse, and fraught with difficulties (Ehnert, 2009 ). No precise definition of the term exists and it has been used in a variety of ways. A number of notions have been used to link sustainability and HRM activities (Kramar, 2014 ). These include sustainable work systems (Abid et al., 2020 ; Docherty et al., 2002 ; Docherty et al.,; 2009 ), HR sustainability (Gollan, 2000 ; Wirtenberg et al., 2007 ), sustainable HR management (Kramar, 2014 ; Ehnert, 2011 , 2006 ), sustainable leadership (Avery, 2005 ; Avery & Bergsteiner, 2010 ;) and sustainable HRM (Mariappanadar, 2012 , 2003 ), HR aspects of sustainable organization (Dunphy et al., 2007 ), sustainable HRM policies (Mariappanadar, 2012 , 2003 ; Avery & Bergsteiner, 2010 ; Stanton et al., 2010 ; Ehnert, 2009 ; Dunphy et al., 2007 ; Purcell & Hutchinson, 2007 ; Teo & Rodwell, 2007 ), sustainable HRM practices (Jackson et al., 2011 ), sustainable work environment (Dunphy et al., 2007 ). Table 1 summarises the different contexts of the definition of sustainable HRM.

Linking sustainability and HRM is related to constantly increasing challenges inside and outside the organization. The challenges directly or indirectly affect the quality and the quantity of human resources. Sustainability is chosen for HRM due to its potential to overcome troubles and develop, to regenerate and preserve human resources in the organization.

In conjunction with economic performance, SHRM intervenes to address issues of engagement with environmental and social impacts. Strategic HRM emphasises the monitoring of human capital through accessible HR practices, taking the economic performance of employees as a basis. Sustainable HRM focuses on the development of an innovative workplace that provides a basis for internal and external social engagement and allows for greater environmental awareness and responsibility. These activities translate into promoting organisational success in a competitive environment. The development of new human resource management strategies and practices leads to economic, social, and environmental progress (Giang & Dung, 2022 ; Podgorodnichenko et al., 2020 ; Chamsa & García-Blandónb, 2019 , p. 111; Indiparambil et al., 2019 , p. 68)

Based on the literature review, we identified three approaches of sustainable HRM (Poon & Law, 2022 ; Chamsa & García-Blandónb, 2019 ; Indiparambil et al., 2019 , p. 69)

A responsibility-oriented approach, namely, the well-being of employees, communities,and work-life balance,

Corporate objectives oriented towards efficiency and innovation, namely,the link between economic performance and sustainability expressed through environmental changes, quality of services and products, technological progress,

Resource-oriented approach, namely, responsible consumption.

In turn, Järlström et al. ( 2018 ) identify four dimensions of sustainable HRM, that is, fairness and equity, transparent HR practices, profitability, and employee well-being. The dimension of employee well-being promotes caring for and supporting employees with due respect. This shows that employees are not just a resource to be used, but an asset to be developed. Employee well-being here means well-being, health, protecting work relationships with others, and work-life balance. Moreover, in the individual sphere of employees, HRM promotes practices that foster mental and physical health, giving importance to the well-being of employees (Indiparambil et al., 2019 , p. 68; Järlström et al., 2018 ). Sustainable HRM increases employee productivity while improving organisational capabilities by offering innovative HR practices. The individual employee is an essential element of SHRM, as it maximises the integration of employee goals with those of the organisation. An enterprise is considered sustainable when the legitimate needs of the enterprise, that is, productive employees, as well as employees, i.e., fair treatment, remuneration, mentoring (Indiparambil et al., 2019 , p. 68; Cleveland & Cavanagh, 2015 ;) are met.

The use of sustainable HRM practices becomes particularly important to ensure the proper development and well-being of employees. Moreover, many authors indicate a link between specific HRM practices, high levels of employee well-being, and employment (Jaskeviciute et al., 2021 ; Strenitzerová & Achimský, 2019 , p. 3; Cooper et al., 2019 ; Stankeviciute & Savaneviciene, 2018 , p. 8; Guest, 2017 ). In this aspect, the following groups of well-being-oriented practices become the most relevant, namely: training and development; mentoring, career support; creating challenging and autonomous work; providing information and receiving feedback; positive social and physical environment; employee voice; and organisational support (Cooper et al., 2019 ; Guest, 2017 ; Jaskeviciute et al., 2021 ;).

Sustainable HRM contributes to attracting and retaining human resource over time (Lopez-Cabrales & Valle-Cabrera, 2020 ; Ehnert, 2009 , p. 180). Employee development, remaining in a competitive work environment, increasing efficiency, and employee work well-being can only be ensured by meeting the needs of employees and providing them with sustainable working environment (Ali et al., 2021 ; Cantele & Zardini, 2018 ; Chatzopoulou et al., 2015 ; Ehnert, 2009 , 2014 ; Guerci et al., 2014 ; Lorincova et al., 2018 ; Mariappanadar, 2014 ; Monusova, 2008 ; Raziq & Maulabakhsh, 2015 ).

At the same time, employee satisfaction itself becomes one of the fundamental aspects of overall well-being and employee sustainable development. Human resources bring talent and expertise to an organization, and these are developed over the course of a career. In the long run, employee development and organisational contributions can translate into higher employee satisfaction and hence organisational commitment (Jaskeviciute et al., 2021 , p. 120; Abid et al., 2020 ; Davidescu et al., 2020 ; Cannas et al., 2019 ; Indiparambil et al., 2019 , p. 69;).

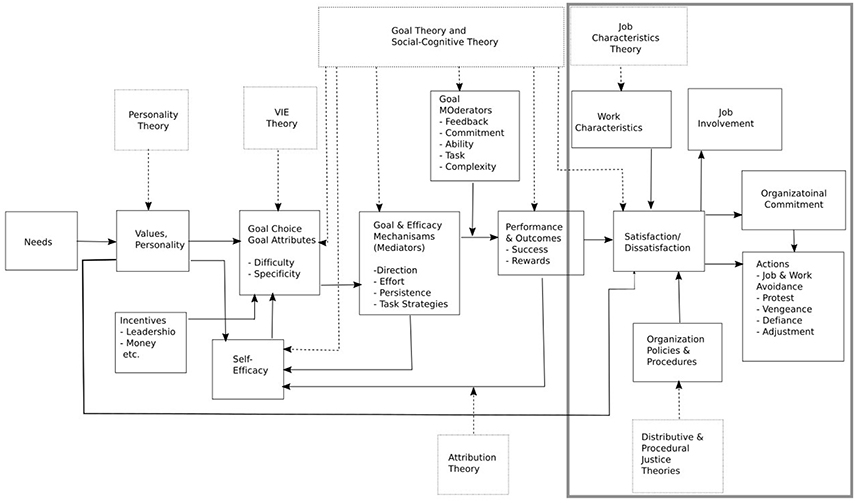

Job satisfaction is a complex and controversial construct, on which there is no single definition. Consensually, it is considered one of the most positive attitudes towards work itself. Currently, there is a predominance of a multidimensional approach that understands satisfaction as a tripartite psychological response composed of feelings, ideas, and intentions to act, by which people evaluate their work experiences in an emotional and/or cognitive way (Judge & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012 ). Specialists agree on the positive impact and beneficial consequences of satisfaction in the workplace. (Böckerman & Ilmakunnas, 2012 ).

Job satisfaction is defined as a positive or pleasant emotional state resulting from job evaluation (Locke, 1976 ) and acquired experiences on the job (Makin et al., 2000 , pp. 82–83). It is an expression of emotional attitude towards the job and the tasks performed, and an emotional response to the job (Spector, 1985 ). It is also an emotional response to the performance of tasks and roles, and in crisis situations, employees with higher job satisfaction will have more strength and energy (Rhéaume, 2021 ; Bańka, 1996 , p.69;).

A review of the literature shows that job satisfaction is also related to engagement (Chordiya et al., 2017 ), intentions to remain in the company (Zhang et al., 2016 ), and trust in the supervisor (Gockel et al., 2013 ).

There are two main approaches to measuring job satisfaction: an overall measure of satisfaction and one that relates to specific aspects of satisfaction. The literature recommends measuring not only overall job satisfaction, but also how its individual components are experienced by employees and affect overall satisfaction. Such multidimensional measures contribute more to a better and deeper understanding of the issue and highlight the importance of job satisfaction especially in the context of sustainable HRM.

It is recognized that job satisfaction is the degree to which employees feel that their needs and expectations are being met. Satisfaction develops through cognitive and emotional responses.

The person-environment fit theory can be a useful framework for understanding why some practices of SHRM have the ability to generate employee satisfaction. This theory holds that the degree of fit between employee needs and organizational supplies impacts employees’ attitudes. Hence, it is likely that positive job satisfaction arises when the degree of perceived fit between the person and the work environment is high, while negative attitudes would develop when the person-environment adjustment is perceived to be low (Salanova et al., 2012 ).

Ensuring that these practices are implemented results in positive outcomes for the individual and the organisation. As part of the successful application of sustainable HRM practices, great importance is placed on aspects related to employee individual development and employee well-being. These strongly influence employee satisfaction and engagement (Zaugg et al., 2001 , p. 3; Cleveland & Cavanagh, 2015 ).

In this article, we focus on job satisfaction, as it is seen as particularly important for the sustainability of workplaces and entire organizations.

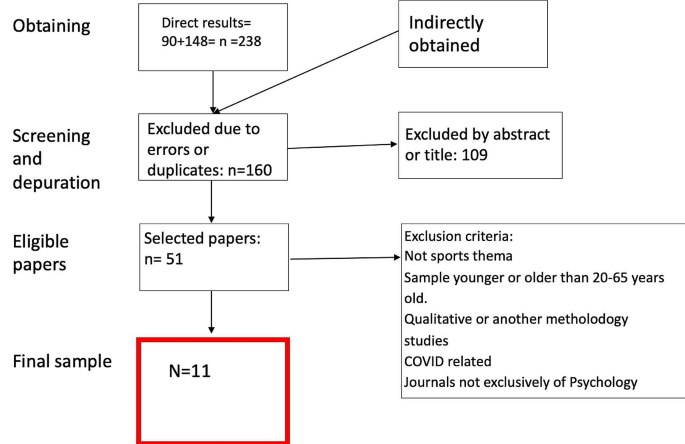

Research model

In order to build research conceptual model, we used a systematic literature review methodology (Czakon, 2011 ). According to the adopted methodology, we carried out the procedure in three stages. The first stage included: (a) definition of the database and the set of publications; (b) selection of publications; (c) elaboration of the final publication database; (d) bibliometric and content analysis of selected materials. Publications for analysis were collected from the EBSCO database. Scientific publications (articles, book chapters) that contained the phrases [sustainable* or sustainable HRM* humanity* job satisfaction* engagement*] were searched. Eligibility criteria were fixed so that studies published in peer-reviewed full-length articles, written in English, were selected for the review process. The search at this stage resulted in over 496 publications in total. In the second step, the we applied the following selection criteria: publications in the field of personnel management, HRM, job satisfaction. This allowed the number of publications to be narrowed down for in-depth substantive analysis, which was carried out in the third stage of the systematic literature review. An accumulated collection of 158 publications was used for this purpose.

The different approaches are not mutually exclusive. Despite their differences, they have one thing in common: understanding that sustainability refers to a long-term and sustainable outcome (Kramar, 2014 , p. 1076).

Based on the results of the literature review, we identified two levels of sustainable HRM contributions – organizational level and individual employee level. The summary is presented in the Table 2 .

The presented issues based on the systematic literature review, have become the basis for hypotheses The authors have focused on the individual employee level of analyses.

It should be noted that despite the extensive discussion in the literature on both the individual and organizational level of SHRM, the research is dominated by the organizational perspective. SHRM is a phenomenon dependent not only on internal organizational conditions, but also on certain characteristics of individual employees. The literature does not provide an answer to the question about the relationship between SHRM on the individual level in the context of employee satisfaction. Moreover, the literature does not explain why higher well-being at work, workforce training, or efforts to retain employees on the part of the company can lead to greater workforce satisfaction.

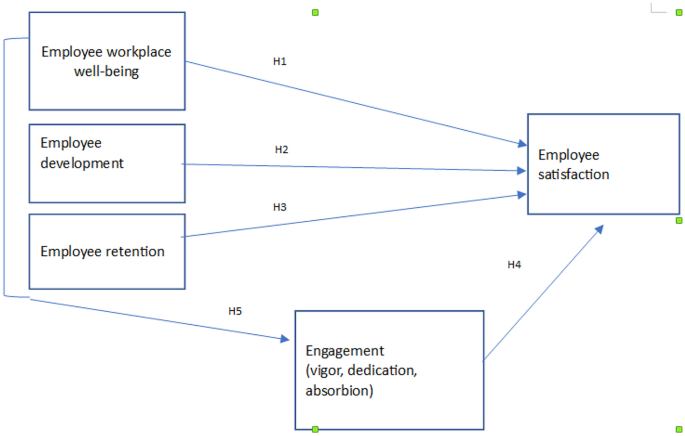

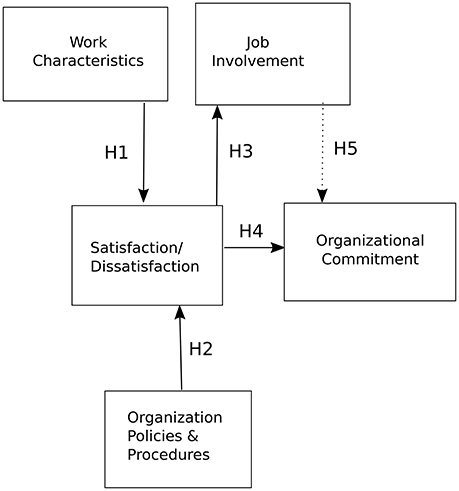

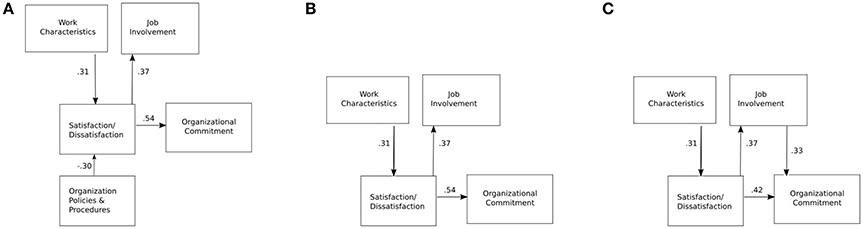

This results in the main research objective of the article, which is recognition of correlations between factors affecting employee satisfaction (employee workplace well-being, employee development, employee retention, work engagement) and employee satisfaction, from the perspective of employee in the sustainable HRM context. Considering the results of systematic literature review, the research model was built to determine the relationships between identified variables (Fig. 1 ).

Source: own elaboration

Research model.

The existing state of knowledge in the field of SHRM in the individual employee context, examined through a systematic literature review has shown that there are current cognitive research gaps. For example, few studies have been devoted to humanity in a sustainable work environment. In particular, there is a lack of research focused on the relationship between employee workplace well-being, employee development and retention, and all these (relationships) related to the employee satisfaction and employee engagement in a sustainable work environment. Therefore, as far as the authors are concerned, there is no such research (from the perspective of employees) conducted in Poland.

The following research hypotheses were formulated:

H1: Employee workplace well-being (EWW) positively correlates with employee satisfaction.

H2: Employee development (ED) positively correlates with employee satisfaction.

H3: Employee retention (ER) positively correlates with employee satisfaction.

H4: Employee engagement (EG) positively correlates with employee satisfaction.

H5: Employee engagement (EG) mediates relationships between employee workplace well-being (EWW), employee development (ED), employee retention (ER) and employee satisfaction.

Based on a review of the well-being literature, Page and Vella-Brodrick ( 2009 ) have argued that employee well-being (EWB) should be measured in terms of social well-being (SWB), psychological well-being (PWB), and work-related affect, that is, workplace well-being (WWB). The last is related to work satisfaction and work-related affect. Employees reporting positive well-being tend to demonstrate higher job satisfaction and job performance as compared to those reporting low levels of well-being (Wright et al., 2007 ).

Raising perceptions of organizational support involves developing leaders and policies that convey consideration for employees' needs, well-being, challenges, and concerns (Eisenberger et al., 1997 ). Workplace well-being is a pleasant or positive emotional state resulting from job evaluation or work experiences (Locke, 1970 ). Bakker and Leiter ( 2010 ) argue that an employee's sense of well-being occurs when they find their job satisfying and when emotions such as joy and happiness prevail. This is supported by studies of the relationship between well-being and job satisfaction, which show that increased well-being accompanies higher job satisfaction (Browne, 2021 ; Machin-Rincon et al., 2020 ; Rhéaume, 2021 ; Wu et al., 2021 ).

A popular analysis of employee well-being includes a concept known as the Vitamin Model of Employee Well-Being by Warr ( 1994 ). The author singles out characteristics of work in the organizational environment that in varying degrees of intensity affect employee well-being (Warr & Clapperton, 2010 ). The model uses comparing work characteristics to vitamins in the human body, which depending on the intensity can positively or negatively affect it. In this case, there is a relationship between their intensity, and job satisfaction. This model focuses on the relationship between job characteristics and mental health of individuals. Employee satisfaction which comes through many ways and one of them is workplace well-being. Employee satisfaction appears in many ways, in various studies. One of them is well-being in the workplace (Siddiqui & Ijaz, 2022 ). Employees in companies implementing wellness programs reported higher work satisfaction rates than those in companies without wellness programs, thereby suggesting that these wellness programs may positively affect job satisfaction for employees (Pawar & Kunte, 2022 ).

Accordingly, we hypothesized that employee workplace well-being positively correlates with employee satisfaction (H1).

Employee-oriented HRM denote the organization’s investment in its human resources, especially in what concerns its growth and professional development.

In organizations characterized by employee centered HRM, given the importance of welfare and development (Clarke & Hill, 2012 ), it would be expected to find higher levels of job satisfaction among its members. Evidence (Hantula, 2015 ) indicates that the most satisfied employees are those who work in positions that offer them freedom, independence, and discretion to schedule work and decide on procedures; autonomy for decision making, as well as opportunities to apply and develop personal skills and competences.

Current changes in the workplace are causing some researchers to take a holistic view of HR culture in an organization to study its impact on employee job satisfaction, and have revealed that there is a correlation between career development and other variables, namely, employee motivation and job satisfaction (Akdere & Egan, 2020 ; Lestari et al., 2021 ; Sheraz et al., 2021 ).

The employees and the management work on the same page and achieve the desired goals. According to Järlström et al. ( 2018 ), sustainable HRM builds a positive path and valuable strategies to maintain progress and employee development. It means a company must be conscious regarding developing their entrepreneurial HR development-based policies and strategies within a workplace.

Development opportunities are a form of recognition for employees' work, which in turn translates into career advancement. Understanding the competencies that will be needed in the future contributes to the design of development plans. Future promotion, which is associated with higher pay, depends on the skills possessed, so allowing employees to develop them can increase employee satisfaction. Increased knowledge and skills can translate into increased satisfaction, due to the achievement of professional goals (satisfaction with one's career) and personal goals (feeling of professional success).

Based on a study conducted by Nguyen and Duong ( 2020 ), it shows that there was a strong positive relationship between training and development element on employee satisfaction.

Opportunity for personal growth is one important factor that has a significant impact on job satisfaction. With the passage of time in employment, if an employee does not have the opportunity for development, the level of satisfaction decreases and discouragement and passivity towards responsibilities increases.

Accordingly, we hypothesized that employee development positively correlates with employee satisfaction (H2).

An important way in which HRM practitioners can increase the satisfaction of employees is through the retention of employees, especially during times of economic challenge. Research demonstrates the powerful negative psychological effects of termination and unemployment on the unemployed (Paul & Moser, 2009 ), and the negative impact on work attitudes by so-called survivors (i.e., employees who remain after downsizing; Datta et al., 2010 ).

There are several motivational theories (Rousseau, 1989 ; Vroom, 1964 ; Adams, 1963 ) that suggest that organizational commitment to employees during difficult times should result in employee commitment to the organization when labor market conditions change in the employees' favor.

Today, in an economy of technological advances, organizations are constantly competing to retain their key employees and avoid high turnover rates by caring about employee satisfaction (Khan et al., 2021 ; Kim et al., 2020 ).

It is difficult for employees to be successful and productive at work if they are distracted and anxious about personal and financial problems (e.g., Bakker & Demerouti, 2007 ; Kahn, 1990 ). Thus, a critical advocacy role for HRM practitioners is to ensure that employees receive a livable pay, benefits, and a secure retirement, which ultimately contributes to their ability to develop and stay at work. These types of incentives are associated with higher employee organizational commitment and job satisfaction (Hulin & Hanisch, 1991 ), and can be powerful in the recruitment process, ensuring that firms are competitive in obtaining the best talent (Siddiqui & Ijaz, 2020 ; Chapman et al., 2005 ).

This leads us to our final hypothesis that employee retention positively correlates with employee satisfaction (H3).

An engaged workforce feels competent, finds meaning in work, and finds growth psychologically through work. Organizations benefit from striving to create an engaged workforce (Byrne et al., 2011 ). By creating opportunities, organizations foster engaged employees who are mentally and physically healthy (Attridge, 2009 ; Schaufeli et al., 2008 ).

Engaged employees tend to be more productive than disengaged employees, resulting in higher employee satisfaction (Harter et al., 2002 ). There is a positive impact of employee engagement to effect of job satisfaction and a current understanding of the dynamics between living wage, job satisfaction, and employee engagement (Hendriks et al., 2022 ; Maleka et al., 2021 ; Sahrish et al., 2021 ; Ngwenya & Pelser, 2020 ).

Organizational psychologists have long seen the potential for work to satisfy belongingness, esteem, and self-actualization needs (Alderfer, 1969 ; Maslow, 1943 ), as well as suggested designing jobs that offer the opportunity to use diverse skills and provide meaning and autonomy to employees (Hackman & Oldham, 1976 ; Herzberg et al., 1959 ). Designing jobs to be meaningful and developmental increases job satisfaction, which in turn has positive effects on organizational outcomes, such as increased productivity and decreased turnover (Champoux, 1991 ; Fried & Ferris, 1987 ). Accordingly, we hypothesized that e mployee engagement (EG) positively correlates with employee satisfaction (H4).

However, in light of the available evidence, it can be hypothesized that employee engagement will mediate the relationship between individual workplace factors (employee workplace well-being, employee development, employee retention) and employee satisfaction.

Although, there is strong empirical evidence of the mediation role played by engagement (Schaufeli & Taris, 2013 ), most research is cross-sectional in nature, and furthermore, the consequences of engagement have been less empirically studied (Halbesleben, 2010 ). Concerning the relationship between work engagement and job satisfaction, empirical research has found a moderate correlation among constructs (Zhang et al., 2022 ; Simbula & Guglielmi, 2013 ; Schaufeli et al., 2008 ).

Work engagement is the linking between the employees’ selves to their work roles where they express themselves as physical, cognitive, and emotional (Kahn, 1990 ). This psychological state (May et al., 2004 ) may be defined as a “positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption” (Schaufeli et al., 2002 , p. 74). Vigor represents high levels of energy, the willingness to put effort in the job, and to persist when confronted with difficulties; dedication means the senses of significance, pride, and enthusiasm; and absorption refers to being fully concentrated and focused on the job. Absorption refers to the feeling of full concentration and immersion in work, accompanied by the experience of unnatural lapse of time, difficulty in detaching from work (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004 ).

In essence, work engagement refers to a persistent and pervasive state that connotes involvement, commitment, enthusiasm, focused effort, and energy (Macey & Schneider, 2008 ; Schaufeli et al., 2002 ).

The literature highlights that organizations benefit from striving to create an engaged workforce (Byrne et al., 2011 ). By creating opportunities, organizations support engaged employees who are mentally and physically healthy (Attridge, 2009 ; Schaufeli & Salanova, 2007 ; Schaufeli et al., 2008 ). Engaged employees tend to perform better than unengaged employees, resulting in higher employee satisfaction (Harter et al., 2002 ). When workers perceive that their organization believes in engagement-oriented policies then it leads toward workplace well-being (Oliveira et al., 2020 ).

Given these relationships, in our analysis we want to give answers to the research hypothesis (H5): employee engagement (EG) mediates relationships between employee workplace well-being (EWW), employee development (ED), employee retention (ER), and employee satisfaction ().

Research has identified four reasons why engaged workers perform better than nonengaged workers and are more satisfied: (a) they often experience positive emotions such as joy, enthusiasm, and happiness; (b) they experience better health conditions; (c) they develop their own job and personal resources; and (d) their engagement is contagious to others (Bakker & Demerouti, 2008 ).

Methodology

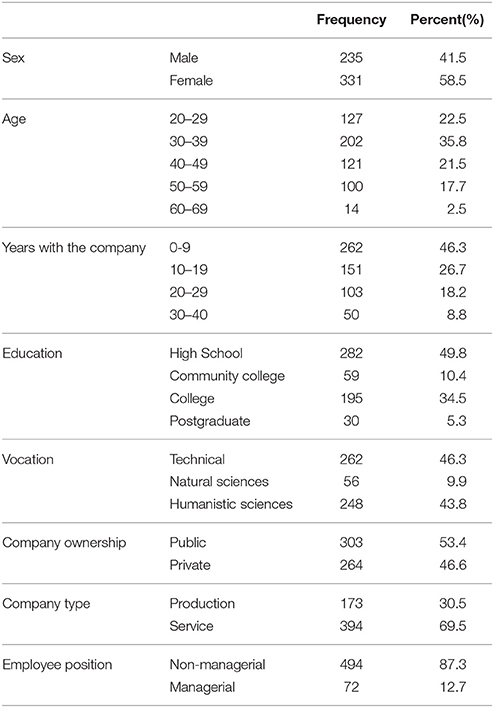

A quantitative questionnaire survey was conducted on a sample of 1051 people in 2019. The respondents were selected through non-random sampling. The criterion for selection of respondents was determined by the size of firms according to the criterion of number of employees (micro, small, medium, and large enterprises. As a criterion the authors adopted the structure of companies in the population of enterprises in Poland, that operate according to sustainable development policies (procedures). Employees of companies that took part in the study constitute a group of 1051 people.

Work engagement was measured accordingly with the theoretical concept of Schaufeli and Bakker ( 2003 ), who define work engagement as a positive, fulfilling feeling towards work, which relates to the state of mind comprised of three dimensions: the sense of vigour experienced by an employee, dedication to work, and absorption. The authors of the above concept define these dimensions as:

Vigour – experiencing a high level of energy and mental endurance at work, willingness to go the extra mile, resilience, especially in the face of adversities;

Dedication – working with enthusiasm, with the sense that one’s work is important, taking pride in being able to do one’s job, being enthusiastic, and welcoming challenges;

Absorption – the sense of full concentration on and involvement in work accompanied by experiencing unnatural passing of the time and with difficulty to stop working. Work Engagement was operationalized with the Polish version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) containing nine statements.

The dimensions of employee workplace well-being, employee development, and employee retention were examined using a proprietary questionnaire consisting of 26 questions. The selection of dimensions was based on the literature review related to sustainable HRM.

Job satisfaction was measured using the Job Satisfaction Scale (Zalewska, 2003 ), consisting of 5 statements regarding the evaluation of the work sphere. A 7-point scale was used in the questionnaire: 1-strongly disagree, 2-disagree, 3-totally disagree, 4-hard to say, 5-rather agree, 6-agree, 7-strongly agree. All statements are elements of one dimension and show high internal consistency in the heterogeneous sample and in individual occupational groups, which confirms that the scale is a reliable, valuable, and accurate tool for measuring overall job satisfaction.

A total of 1,051 people participated in the survey, of which 68.2% were female and 31.8% were male. Most respondents were aged 20–29 years (64.4%), those aged 30–39 years were 18.6%, and those aged 40–49 years were 14.5%. However, those over 50 years of age comprised 2.6% of the sample. Most (43.3%) of the respondents were employed in large enterprises (over 250 employees). Medium enterprises (50–249 employees) accounted for 21.2%, and small enterprises (10–49 employees) accounted for 22.3% of the respondents. The smallest group (12,7%) were respondents representing micro enterprises (up to 9 employees). Missing data represented 0.6%. Most of the respondents were from companies with Polish capital (68.3%), and the least from companies with mixed capital (15%). However, 16.1% of respondents were from foreign capital companies. Lack of data was 0.6%.

Research results

In the preliminary analysis descriptive statistics were calculated. The verification of hypotheses H1 to H4 was based on correlation analysis. Hypothesis H5 regarding mediation was verified with the use of mediation analysis based on macro–Hayes Process ( 2018 ).

The study decided to use correlation analysis to examine the linear relationship between the variables. The purpose of this analysis was to examine the strength of the relationship between the variables. As a result of this analysis, it can be determined whether a particular factor, a particular variable, has an impact on job satisfaction.

Another analysis was a mediation analysis based on the macro-Hayes process. Mediation analysis has been used for many years by researchers (Baron & Kenny, 1986 ; MacKinnon, 2008 ;).

The purpose of the analysis in our study was to test the mediating role of commitment with its dimensions (vigor, dedication, absorption) in the relationship between well-being, employee development, retention, and job satisfaction.

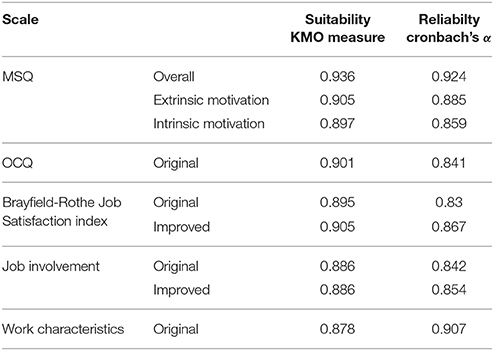

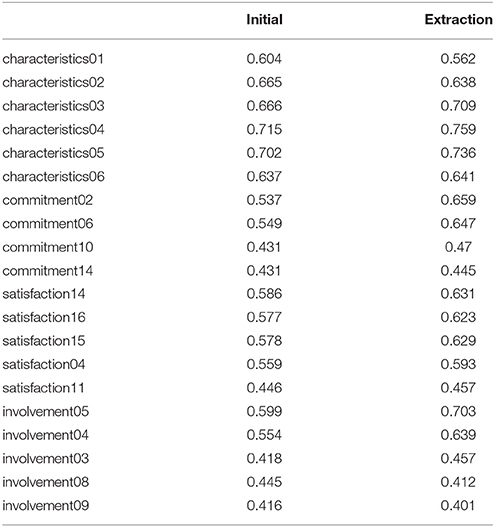

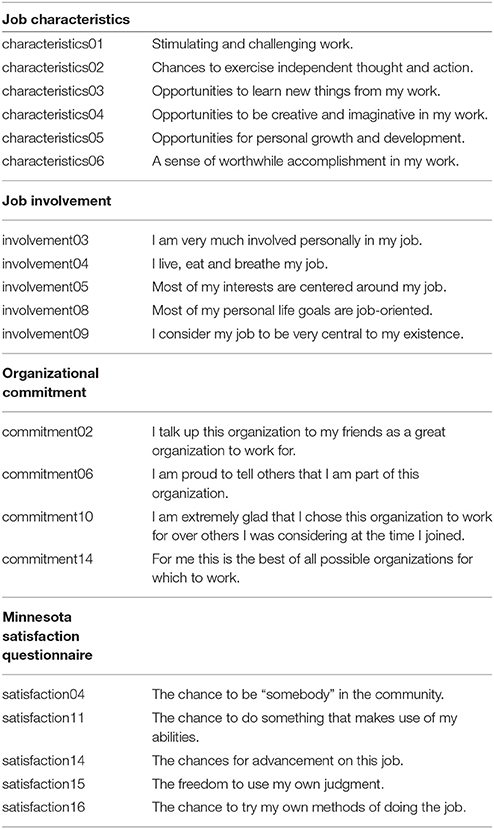

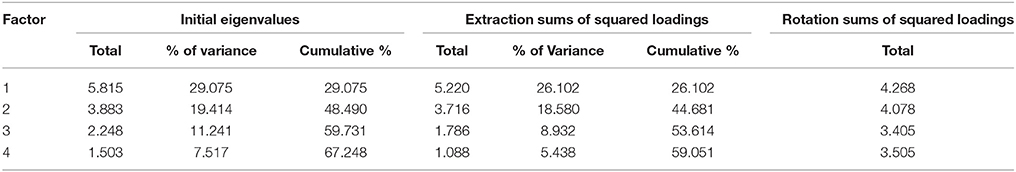

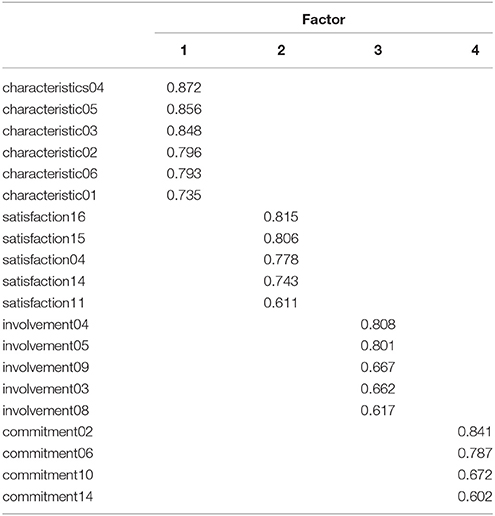

Table 3 presents descriptive statistics for analysed variables, namely, mean values, standard deviations, minimum and maximum values, measures of skewness and kurtosis, and Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients.

The values of skewness and kurtosis did not exceed the range from -1.0 to 1.0. Therefore, parametric statistical tests were used in the subsequent analysis.

Reliability α—Cronbach's is at a high level in all variables studied. For WWB it is 0.93, ED 0.80, ER 0.77, while the overall score for employee engagement is 0.91 and employee satisfaction 0.91.

Correlation analysis

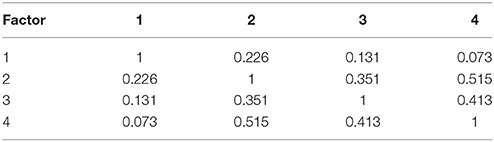

Table 4 values of Pearson correlation coefficients between analysed variables.

Employee workplace well-being correlated positively with employee satisfaction, which supports hypothesis H1. Employee development correlated positively with employee satisfaction, which supports hypothesis H2. Employee retention correlated positively with employee satisfaction, which supports hypothesis H3.

Vigor, dedication, absorption, and total employee engagement also positively correlated with employee satisfaction, which supports hypothesis H4.

The results of the correlation analysis indicate that all the variables adopted in the study are significant and influence job satisfaction. Therefore, it can be concluded that employee well-being, employee development, retention and engagement determine in an employee satisfaction with the work he does for his organization. This result has practical implications for the organization, as will be discussed later.

Mediation analysis

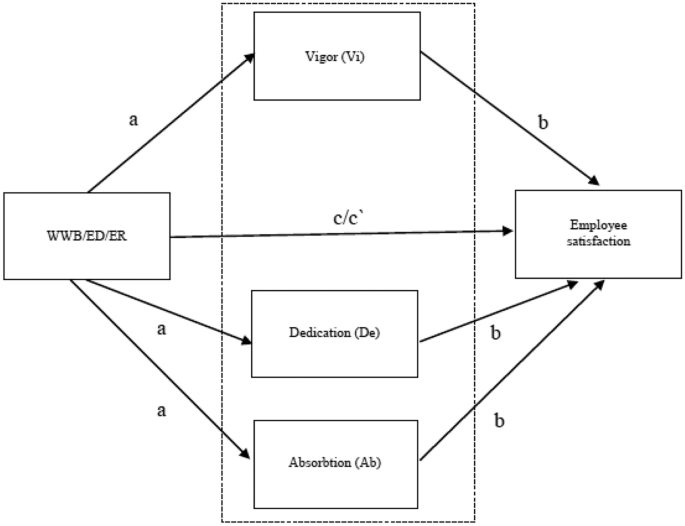

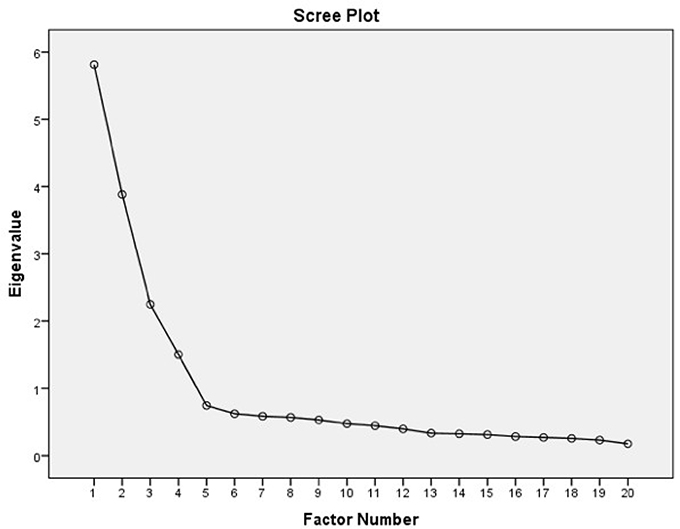

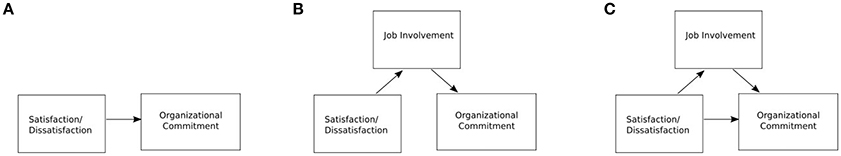

Employee engagement and its components, vigor, dedication, and absorption, were analysed as mediators of the relationship between employee workplace well-being, employee development, employee retention and employee satisfaction. The analysis was performed with the use of Hayess Process macro ( 2018 ) and based on the model no. 4. Figure 2 depicts analysed relationships between analysed variables. Employee workplace well-being, employee development, employee retention and employee satisfaction were analysed in separate statistical models. Vigor, dedication, and absorption were analysed as three parallel mediators. Total employee engagement was analysed as a mediator in a separate statistical model.

Model of analysed relationships between analysed variables.

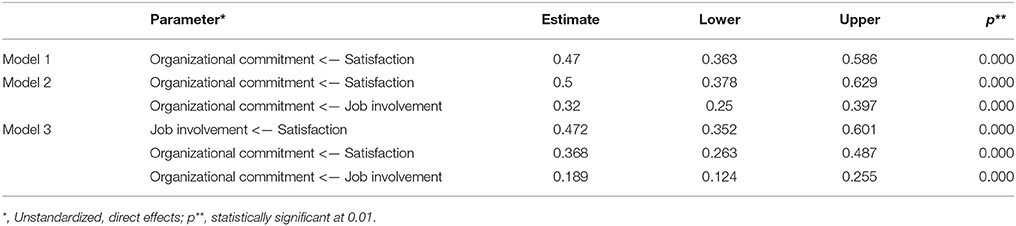

Table 5 presents results of mediation analysis. 95% confidence intervals were based on the bootstrap method with 1.000 consecutive drawings.

The acquired results support hypothesis H5. Depending on the explained variable analysed statistical models explained from 52 to 67% of employee satisfaction variance. Interpreting the results, we can consider that total employee engagement, vigor (Vi) and dedication (De) were statistically significant mediators between employee workplace well-being (WWB), employee development (ED), employee retention (ER), and employee satisfaction.

The results of the study show that the direct relationships between employee workplace well-being (WWB), employee development (ED), employee retention (ER) and employee satisfaction were also statistically significant. Interpreting the results, it can be concluded that total employee engagement, vigor, and dedication were partial mediators.

In contrast, there was no statistically significant mediation effect for absorption (Ab).

We referred to this result in the discussion section of the article, pointing out the dangerous phenomenon with which absorption is associated. The phenomenon concerns losing track of time, immersing oneself in work, and having issues with detaching from it.

In addition, the results showed that higher levels of employee well-being in the workplace (WWB), employee development (ED), employee retention (ER) was related to higher level of vigor, higher level of dedication and higher total level of employee engagement, which in turn led to higher level of employee satisfaction.

The results of the mediation analysis indicate the mediating role of vigor and dedication increasing job satisfaction considering the relationship of well-being, employee development, retention with job satisfaction.

Discussion and conclusion

It is shown that the sustainable HRM is a developmental approach for employees. Within sustainable HRM practice employees are not just resources but assets. Sustainable HRM ensures leveraging capabilities of employees guaranteeing the sustenance of this ‘human capital’ as a source of competitive advantage. Sustainable HRM considers employees' satisfaction, engagement, and well-being. It finally endorses that ultimately successful individuals become the foundation stones for effective and successful organizations (Indiparambil, 2019 ; Parakandi & Behery, 2015 ).

The main objective of our study was to identify individual-level correlations between factors affecting employee satisfaction, such as workplace well-being, employee development, employee retention, job engagement and employee satisfaction. As the literature review shows, this goal is extremely legitimate because of the practical implications for both organizations, employees, and science.

Overall, our results indicate that workplace well-being, employee development, employee retention, and employee engagement positively correlate with employee satisfaction. In addition, the results show the mediating role of employee engagement in the relationship between workplace well-being, employee development, employee retention, and employee satisfaction. This means that the higher the level of these variables, the higher the level of commitment and this in turn leads to higher levels of satisfaction.

We studied engagement based on 3 dimensions: vigor, dedication, absorption. As the results show, the absorption dimension has no effect on the level of job satisfaction. This means that what is important is the level of energy put into the work, mental stamina, readiness to make an effort, doing the work with enthusiasm, pride, a sense of its importance, willingness to accept challenges. All this, while avoiding excessive work, inability to stop working, and losing track of time. In our opinion, a high level of absorption can often lead to workaholism, which can act adversely to the well-being of employees.

In our theoretical framework, we argued that job satisfaction is a complex theoretical construct that, when studied empirically, takes into account many different factors that influence it. Thus, it is up to researchers to determine which factors are empirically studied. Our review of the literature indicated that there are studies that have considered factors in terms of organization, interpersonal relationships, activities, and tasks, and working conditions (Sypniewska, 2014 ; Sarmiento et al., 2004 , 134–143;; Zalewska, 2001 ). These factors relate simultaneously to the organizational and individual levels.

We considered it necessary to delineate factors in our study by considering the individual level due to the employee's perspective in the context of sustainable HRM. A condition that is theoretically important and recommended in the literature, according to us, has been fulfilled, which means, according to many authors, that the level of satisfaction increases or decreases depending on the individual respondents' evaluation of the variables studied (Meneghel et al., 2016 ; Nemani & Diala, 2011 ).

Given the above, our findings show confirmation of the hypotheses posed prior to the study, which relate to factors such as workplace well-being, employee development, retention, and engagement.

Analyzing the first hypothesis, concerning the correlation of well-being and satisfaction, it turned out that the two variables correlate positively with each other (this confirms the posited H1).

This means that people who experience well-being in the workplace simultaneously experience job satisfaction. Considering the theoretical framework, we see that some researchers of job satisfaction describe it as a motivational factor related to engagement and as a measure of the quality of human capital management and a determinant of the quality of relational capital (Chrupała-Pniak, 2012 ; Juchnowicz, 2014 ). In contrast, psychologists drawing from cognitive and humanistic psychology treat job satisfaction by referring to the concept of quality of life and human well-being in organizations, where it is an end in itself, rather than as a tool for increasing efficiency (Czerw, 2016 ; Łaguna, 2012 ; Dobrowolska, 2010 ; Ratajczak, 2007 ; Bańka, 2002 ).

What then is well-being? "The well-being of an individual is related to the fact of employment, in which there is hope, optimism, peace" (Dobrowolska, 2010 ). In our view, an organization can influence the overall and partial level of job satisfaction by contributing to the overall well-being of employees in the workplace and to overall job satisfaction by creating appropriate working conditions for employees, including attention to the atmosphere at work. Thus, it can also be considered that an employee's sense of well-being occurs when they find their job satisfying and when emotions such as joy and happiness dominate.

Our results also show that employee development positively correlates with job satisfaction (H2), which is theoretically and practically justified. We recognize that every employee strives for his own professional development. It matters to him not so much to do a job in a particular organization, but let this development be an added value for him in the future. Given the current technological changes and high competition, the demand for employee training is growing. So effective employee development initiatives offer benefits not only to employees, but also to organizations.

The incurred contribution to employee development by the organization pays off in the near term through increased employee productivity, engagement, and openness to new ideas. As previously mentioned for employees, development improves their chances in the competitive labor market, especially during times of economic recession, for example (Millman & Latham, 2001 ). It should also be noted that some employees seek self-improvement within the profession. Successful, relevant, and effective training experiences can also serve as an indication that an organization is willing to invest in human capital and notices and meets the development needs of its employees. Such feelings can increase attachment to the organization, which in turn can translate into job satisfaction and enjoyment of being in that organization.

Our findings also show a positive correlation regarding employee retention with job satisfaction (H3). As mentioned earlier, satisfaction is a combination of what an employee feels (emotions) and what they think about various aspects of the job (cognition) (Rich et al., 2010 ; Organ & Near, 1985 ; Locke, 1969 ). It includes values, willingness to put effort into work, commitment, and a strong desire to stay with the organization (Schultz & Schultz, 2002 ). It is important for a company to promote values in common with those of its employees, this affects positive brand perception and effective work. Activities aimed at identifying employees with the company's values, as well as ways of managing and/or motivating them, influence positive perceptions of the organization and significantly affect job satisfaction. All this influences the desire to stay with the organization or leave it. So, when the right conditions are met, an employee does not look for another job, another organization. He feels fulfilled in the one where he works and does not decide to leave it, which of course is of great value to the organization even due to the huge costs associated with the search for new employees.

Our next findings concerned the correlation of engagement with employee satisfaction. It turned out that this hypothesis (H4) was positively verified. Undoubtedly, when employees' expectations and needs are met, they are more engaged in their tasks. This fulfillment of expectations and needs by the organization in turn translates into their satisfaction not only with their jobs, but also with being in an organization that cares about them (Qing et al., 2020 ). For many years, organizational psychologists have recognized the potential of work to meet the needs of belonging, esteem, and self-actualization (Alderfer, 1969 ; Maslow, 1943 ), as well as to design workplaces that provide opportunities to use a variety of skills and provide employees with meaning and autonomy (Hackman & Oldham, 1976 ; Herzberg et al., 1959 ).

In our study, we demonstrated the mediating role of engagement in the relationship between employee well-being in the workplace, employee development, employee retention and employee satisfaction (H5). Thus, our study demonstrated engagement at work as a mediator. The relationship showed statistical significance for all these factors with the engagement dimension: vigor and dedication, but no significance with the absorption dimension. This means that in people who show an experience of high levels of energy and mental toughness at work, a willingness to put effort into work, and are resilient and resilient in the face of adversity, the sense of job satisfaction is enhanced. Such enhancement is also found in people who perform work with enthusiasm, experience a sense of meaning and importance, feel pride in their work, and view work as a challenge and inspiration.

The lack of statistical significance for the absorption dimension does not necessarily mean that people do their work without being immersed in it and forgetting about the passage of time or the difficulty in detaching from it. In fact, research shows that people who score low on the absorption dimension do not have difficulty detaching themselves from it and forgetting everything going on around them, including time (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2003 ). As noted earlier, a state of excessive concentration on work, excessive losing oneself in work while feeling the passage of time unnaturally and finding it difficult to detach oneself from work can lead to workaholism, which in turn affects the well-being of the employee. There must be moderation in everything, and it is the role of the organization to create such working conditions and delegate such tasks that the employee does not work beyond his or her strength and does not lose himself or herself in work while feeling immense time pressure. Positive emotions, well-being, a sense of self-efficacy, energy translate into factors that make up the sense of job satisfaction internally, individually, but it does not have to be characterized by difficulties in dedicating oneself to work or even in interrupting a task, as in the case of workaholism.

As highlighted earlier, the perception of job satisfaction is a subjective feeling. What is important, however, is that this subjectivity of perceived satisfaction makes it impossible to design measures aimed at increasing job satisfaction that are the same for all employees, measures aimed at increasing positive feelings (Fiech & Mudyń, 2011 ). Being happy and fulfilled at work is a function of the multiplicity of work experiences in an organization. (Crede et al., 2007 ).

Our literature review showed that when employees have meaningful and meaningful work, they tend to be more enthusiastic about developing pro-sustainability activities and practices (Xanthopoulou et al., 2009 ); however, when they perceive that such practices do not align with the organization's values, their willingness to experience engagement at work decreases (Colvin & Boswell, 2007 ; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004 ;), and their performance becomes lower than it potentially could be (Bakker et al., 2004 ).

Practical, organizational, and scientific implications

In addition to our contribution to the mainstream of research on job engagement and job satisfaction in the practice of SHRM, we enrich the literature on human capital by studying the impact of factors at the individual level on job satisfaction. In a similar way, we contribute to the perspective of managing people in an organization, explaining how to motivate employees, what factors at work to pay attention to in order to increase their satisfaction and engagement which translates into the success of the organization itself. Of course, it is clear that the factors we study are not the only factors. Therefore, we point out that it is important to expand the research to include still other factors of importance for greater satisfaction and engagement. While the literature to date has pointed to other factors, our study was by design to take a sustainability approach.

Another of our contributions is a deeper understanding of the mediating role that employee engagement, including its dimensions, plays on job satisfaction. Our results showed that engagement and its dimensions mediate the relationship between individual factors (employee development well-being, retention, overall engagement) and job satisfaction. Another of our contributions is the measurement of empirical relationships between the factors studied and job satisfaction. The size of our research sample may indicate some generalization (but not generalization) of our results at the individual level with boundary conditions defined by multilevel interactions taking into account other factors.

Our analysis is particularly valuable to decision-makers because it can inform them about the conditions to be created for employees and how to motivate them from a sustainability perspective. The implications for decision-makers also translate into implications for the organization itself. Organizations should strive to apply/implement SHRM practices. Organizations should focus on individual SHRM levels that translate into employee job satisfaction as an indicator of success in creating workplaces that foster well-being, employee well-being, employee retention, engagement, and productivity. If work is unsatisfactory, employees may feel tension, refrain from contributing more, or quit. Therefore, periodic job satisfaction surveys are extremely important to help identify negative and positive feelings.

It is worth noting the findings of other researchers on job satisfaction, in which satisfaction was a motivating factor in entrepreneurial activities (Blaese et al., 2021 ). Other studies have highlighted the role of conflict in perceived job satisfaction, which is related to employees' feelings of well-being (Schoss et al., 2022 ).

Another implication for practice from the presented study is the creation of SHRM policies for employee development, as this is one of the factors that has a significant impact on job satisfaction and engagement. Successful employee development initiatives benefit not only employees, but also the organization. It is therefore important to include training programs that, among other things, promote employee self-actualization and team building, a work atmosphere that promotes employee well-being.

Intuitive methods to motivate employees to work more efficiently used by decision-makers seem to be insufficient. Therefore, our study can make an important contribution to expanding knowledge about ways to increase job satisfaction and engagement. The organization's policies in terms of ways to motivate employees translate into the employees themselves, especially their willingness to stay or leave the organization. An employee who feels that the organization cares about the development of employees, their mental state and perceived emotions, their well-being is less likely to decide to leave. After all, as mentioned earlier, high employee turnover is associated with huge recruitment costs. It is not just financial costs, but also the cost of recruiter time or the cost of adapting a new employee.

Limitations and direction for future research

The studied sample, although quite numerous, cannot be considered representative of the general population of Polish employees. Therefore, the generalizability of the findings obtained is not without questions. It should be noted that the questionnaire was not oriented towards employees of organizations which report to have sustainability strategies.

A potential limitation is related to our measure of WWB, ED, ER. Although the current research provides evidence that these factors are related to job satisfaction, additional research is needed to further examine the form and function of these factors. Future studies could use objective measures to evaluate those factors.

Among the limitations, it should be noted that, since all the variables were measured in the same questionnaire, the results could have been affected by biases due to the variance of the common method. With a view to overcoming this problem (Podsakoff et al., 2012 ), future research should/could include other sources of exploration, such as supervisors’ opinions, as well as systematic observations.

The authors are aware that the article does not exhaust the research problem research problem and is only an impulse for further research on the complex issue of SHR practices and their relationship to engagement and satisfaction in the workplace. There are few humanity direction studies in SRHM, also this is a gap that needs to be filled in the future.

It would also be useful to examine the impact of various sustainable HRM practices to see which ones have the greatest impact on work engagement.

Future research may also consider other individual and individual-level factors that could potentially moderate this relationship between human resources and engagement, such as leader-team member relationship, collectivism/individualism orientation, organization support, and employee type.

The present study could be capitalized for the inauguration of new lines of research in the area. The suggestions, without being exhaustive, are oriented to the following disseminate and foster SHRM practices that are positively associated with job satisfaction.

Looking ahead, an interesting research direction would be to conduct a longitudinal study analyzing the relationships studied in different phases of the organization's life cycle. In our opinion, it could contribute to defining the currently studied variables (factors) in retrospect, whether they are still important to employees or have lost their importance.

Abid, G., Ahmed, S., Elahi, N. S., & Ilyas, S. (2020). Antecedents and mechanism of employee well-being for social sustainability: A sequential mediation. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 24 , 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2020.06.011

Article Google Scholar

Adams, J. S. (1963). Toward an understanding of inequity. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67 (5), 422–436. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040968

Akdere, M., & Egan, T. (2020). Transformational leadership and human resource development: Linking employee learning, job satisfaction, and organizational performance. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 31 (4), 393–421.

Alderfer, C. P. (1969). An empirical test of a new theory of human needs. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 4 (2), 142–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(69)90004-X

Ali, M., Ali, I., Albort-Morant, G., & Leal-Rodríguez, A. L. (2021). How do job insecurity and perceived well-being affect expatriate employees’ willingness to share or hide knowledge? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 17 (1), 185–210.

Attridge, M. (2009). Measuring and managing employee work engagement: A review of the research and business literature. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 24 (4), 383–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/15555240903188398

Avery, G. (2005). Leadership for sustainable futures: Achieving success in a competitive world . Edward Elgar Publishing.

Book Google Scholar

Avery, G. C., & Bergsteiner, H. (2010). Honeybees & locusts: The business case for sustainable leadership . Allen & Unwin.

Google Scholar

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands–resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22 , 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2008). Towards a model of work engagement. Career Development International, 13 (3), 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430810870476

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Verbeke, W. (2004). Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Human Resource Management, 43 (1), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20004

Bakker, A. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2010). Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research . Psychology Press.

Bańka A. (1996). Psychopatologia pracy [Workplace psychopathology]. Gemini.

Bańka, A. (2002). Psychologia organizacji [Organizational psychology]. In J. Strelau (Ed.), Psychologia. Podręcznik akademicki (pp. 321–350). GWP.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17 (1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51 (6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Becke, G. (2014). Human-resources mindfulness. In I. Ehnert, W. Harry, & K. Zink (Eds.), Sustainability and human resource management (pp. 83–103). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-37524-8_4

Chapter Google Scholar

Blaese, R., Noemi, S., & Brigitte, R. (2021). Should I stay, or should I go? Job Satisfaction as a moderating factor between outcome expectations and entrepreneurial intention among academics. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 17 (3), 1357–1386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-021-00744-8

Böckerman, P., & Ilmakunnas, P. (2012). The job satisfaction-productivity nexus: A study using matched survey and register data. ILR Review, 65 (2), 244–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979391206500203

Bombiak, E. (2020). Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 7 (3), 1667–1687. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2020.7.3(16)

Boudreau, J. W., & Ramstad, P. M. (2005). Talentship, talent segmentation, and sustainability: A new HR decision science paradigm for a new strategy definition. Human Resource Management, 44 (2), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20054

Browne, I. (2021). Exploring reverse mentoring: “Win-win” relationships in the multi-generational workplace. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 15 , 246–259. https://doi.org/10.24384/jkc9-2r51

Browning, V., & Delahaye, B. (2011). Enhancing workplace learning through collaborative HRD. In M. Clarke (Ed.), Readings in HRM and sustainability (pp. 36–50). Australia: Tilde University Press.

Byrne, Z. S., Palmer, C. E., Smith, C. L., & Weidert, J. M. (2011). The engaged employee face of organizations. In M. A. Sarlak (Ed.), The new faces of organizations in the 21st century (pp. 93–135). NAISIT Publishers.

Cannas, M., Sergi, B. S., Sironi, E., & Mentel, U. (2019). Job satisfaction and subjective well-being in Europe. Economics and Sociology, 12 (4), 183–196. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2019/12-4/11

Cantele, S., & Zardini, A. (2018). Is sustainability a competitive advantage for small businesses? An empirical analysis of possible mediators in the sustainability–financial performance relationship. Journal of Cleaner Production, 182 , 166–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.016

Champoux, J. E. (1991). A multivariate test of the job characteristics theory of work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 12 (5), 431–446. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030120507

Chamsa, N., & García-Blandónb, J. (2019). On the importance of sustainable human resource management for the adoption of sustainable development goals. Resources, Conservation & Recycling, 141 , 109–122.

Chapman, D. S., Uggerslev, K. L., Carroll, S. A., Piasentin, K. A., & Jones, D. A. (2005). Applicant attraction to organizations and job choice: A meta-analytic review of the correlates of recruiting outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90 (5), 928–944. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.928

Chatzopoulou, M., Vlachvei, A., & Monovasilis, T. (2015). Employee’s motivation and satisfaction in light of economic recession: Evidence of Grevena Prefecture-Greece. Procedia Economics and Finance, 24 , 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00633-4

Chen, K., & Chen, Ch. (2022). Effects of university teachers’ emotional labor on their well-being and job satisfaction. Revista de Cercetare si Interventie Sociala, 76 , 123–132. https://doi.org/10.33788/rcis.78.8

Chordiya, R., Sabharwal, M., & Doug, G. (2017). Affective organizational commitment and job satisfaction: A cross-national comparative study. Public Administration, 95 (1), 178–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12306

Chrupała-Pniak, M. (2012). Satysfakcja zawodowa - artefakt czy funkcjonalny wymiar kapitału intelektualnego: Przegląd koncepcji teoretycznych i podejść badawczych [Job satisfaction - a relic or functional dimension of intellectual capital: A review of theoretical concepts and research approaches]. Edukacja Ekonomistów i Menedżerów, 2 (24), 13–28. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0009.5785

Clarke, M., & Hill, S. (2012). Promoting employee wellbeing and quality service outcomes: The role of HRM practices. Journal of Management & Organization, 18 (5), 702–713. https://doi.org/10.5172/jmo.2012.18.5.702

Cleveland, J. N., & Cavanagh, T. M. (2015). The future of HR is RH: Respect for humanity at work. Human Resource Management Review, 25 (2), 146–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2015.01.005

Colbert, B. A., & Kurucz, E. C. (2007). Three conceptions of triple bottom line business sustainability and the role for HRM. People and Strategy, 30 (1), 21.

Colvin, A. J. S., & Boswell, W. R. (2007). The problem of action and interest alignment: Beyond job requirements and incentive compensation. Human Resource Management Review, 17 (1), 38–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2006.11.003

Cooper, B., Wang, J., Bartram, T., & Cooke, F. L. (2019). Well-being-oriented human resource management practices and employee performance in the Chinese banking sector: The role of social climate and resilience. Human Resource Management, 58 (1), 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21934

Crede, M., Chernyshenko, O. S., Stark, S., Dalal, R. S., & Bashshur, M. (2007). Job satisfaction as a mediator: An assessment of job satisfaction’s position within the nomological network. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 80 , 515–538. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317906X136180

Czakon, W. (2011). Metodyka systematycznego przeglądu literatury [Methodology of systematic literature review]. Przegląd Organizacji, 3 , 57–61.

Czerw, A. (2016). Psychologiczny model dobrostanu w pracy: Wartość i sens pracy [A psychological model of well-being at work: The value and meaning of work]. PWN.

Datta, D. K., Guthrie, J. P., Basuil, D., & Pandey, A. (2010). Causes and effects of employee downsizing: A review and synthesis. Journal of Management, 36 , 281–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309346735

Davidescu, A. A., Apostu, S. A., Paul, A., & Casuneanu, I. (2020). Work flexibility, job satisfaction, and job performance among Romanian employees – Implications for sustainable human resource management. Sustainability, 12 (15), 6086. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156086

De Prins, P., De Vos, A., Van Beirendonck, L., & Segers, J. (2014). Sustainable HRM: Bridging theory and practice through the ‘Respect Openness Continuity (ROC)’-model. Management Revue, 25 (4), 263–284. https://doi.org/10.5771/0935-9915-2014-4-263

De Prins, P., De Vos, A., Van Beirendonck, L., & Segers, J. (2015). Sustainable HRM for sustainable careers: Introducing the Respect Openness Continuity (ROC) model. In A. De Vos, & I. J. M. Beatrice (Eds.), Handbook of research on sustainable careers (pp. 319–334). https://doi.org/10.4337/9781782547037.00026

de Souza Freitas, W. R., Jabbour, C. J. C., & Santos, F. C. A. (2011). Continuing the evolution: Towards sustainable HRM and sustainable organizations. Business Strategy Series, 12 (5), 226–234. https://doi.org/10.1108/17515631111166861

Debroux, P. (2014). Sustainable HRM in east and Southeast Asia. In I. Ehnert, W. Harry, & K. Zink (Eds.), Sustainability and human resource management (pp. 315–337). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-37524-8_14

Dobrowolska, M. (2010). Związek satysfakcji z pracy i kosztów psychologicznych pracowników tymczasowo zatrudnionych [Relationship of job satisfaction and psychological costs of temporarily employed workers]. In B. Kożusznik, & M. Chrupała-Pniak (Eds.), Zastosowania psychologii w zarządzaniu (pp. 229–248) . Wydawnictwo UŚ. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12128/1523

Docherty, P., Forslin, J., Shani, A. B., & Kira, M. (2002). Emerging work systems. In P. Docherty, J. Forslin, & A. B. Shani (Eds.), Creating sustainable work systems (pp. 3–14). Routledge.

Docherty, P., Kira, M., & Shani, A. B. (2009). What the world needs now is sustainable work systems. In P. Docherty, M. Kira, & A. B. Shani (Eds.), Creating sustainable work systems. developing social sustainability (pp. 1–21). Routledge.

Donnelly, N., & Proctor-Thomson, S. (2011). Workplace sustainability and employee voice. In M. Clarke (Ed.), Readings in HRM and sustainability (pp. 117–132). Tilde University Press.

Dorenbosch, L. (2014). Striking a balance between work effort and resource regeneration vitality as a sustainable performance concept . Springer.

Dunphy, D., Griffiths, A., & Benn, S. (2007). Organization change for corporate sustainability (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Ehnert, I. (2006). Sustainability issues in human resource management: Linkages, theoretical approaches, and outlines for an emerging field [Conference presentation]. 21st EIASM SHRM Workshop, Aston, Birmingham.

Ehnert, I. (2009). Sustainable human resource management . Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-7908-2188-8

Ehnert, I. (2011). Sustainability and human resource management. In A. Wilkinson & K. Townsend (Eds.), The future of employment relations (pp. 215–237). Palgrave Macmillan.

Ehnert, I. (2014). Paradox as a lens for theorizing sustainable HRM. In I. Ehnert, W. Harry, & K. J. Zink (Eds.), Sustainability and human resource management (pp. 247–271). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-37524-8_11

Ehnert, I., & Harry, W. (2012). Recent developments and future prospects on sustainable human resource management: Introduction to the special issue. Management Revue, 23 (3), 221–238. https://doi.org/10.2307/41783719

Ehnert, I., Parsa, S., Roper, I., Wagner, M., & Muller-Camen, M. (2016). Reporting on sustainability and HRM: A comparative study of sustainability reporting practices by the world’s largest companies. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27 (1), 88–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1024157

Eisenberger, R., Cummings, J., Armeli, S., & Lynch, P. (1997). Perceived organizational support, discretionary treatment, and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82 (5), 812–820. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.82.5.812

Fiech, M., & Mudyń, K. (2011). Pomijanie działań kształtujących poziom zadowolenia zawodowego pracowników jako przejaw dysfunkcji w procesie zarządzania zasobami ludzkimi [Omission of activities shaping the level of professional satisfaction of employees as a manifestation of dysfunction in the process of human resource management]. Problemy Zarządzania, 9 (4/34), 147–161.

Fried, Y., & Ferris, G. R. (1987). The validity of the job characteristics model: A review and meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 40 (2), 287–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1987.tb00605.x

Giang, H. T. T., & Dung, L. T. (2022). The effect of internal corporate social responsibility practices on firm performance: The mediating role of employee intrapreneurial behaviour. Review of Managerial Science, 16 (4), 1035–1061.

Gockel, C., Robertson, R., & Brauner, E. (2013). Trust your teammates or bosses? Differential effects of trust on transative memory, job satisfaction, and performance. Employee Relations, 35 (2), 222–242. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425451311287880

Gollan, P. (2000). Human resources, capabilities and sustainability. In D. Dunphy, J. Beneviste, A. Griffiths, & P. Sutton (Eds.), Sustainability: The corporate challenge of the twenty first century (pp. 55–77). Allen & Unwin.

Gollan, P. J., & Xu, Y. (2014). Fostering corporate sustainability: Integrative and dynamic approaches to sustainable HRM. In I. Ehnert, W. Harry, & K. J. Zink (Eds.), Sustainability and human resource management: Developing sustainable business organizations (pp. 225–245). Springer.

Guerci, M., & Vinante, M. (2011). Training evaluation: An analysis of the stakeholders’ evaluation needs. Journal of European Industrial Training, 35 (4), 385–410. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090591111128342

Guerci, M., Shani, A. B. R., & Solari, L. (2014). A stakeholder perspective for sustainable HRM. In I. Ehnert, W. Harry, & K. J. Zink (Eds.), Sustainability and human resource management: Developing sustainable business organizations (pp. 205–223). Springer.

Guest, D. E. (2017). Human resource management and employee well-being: Towards a new analytic framework. Human Resource Management Journal, 27 (1), 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12139

Hackman, J., & Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16 (2), 250–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(76)90016-7

Halbesleben, J. R. (2010). A meta-analysis of work engagement: Relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences. In A. B. Bakker & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research (pp. 102–117). Psychology Press.

Hantula, D. A. (2015). Job satisfaction: The management tool and leadership responsibility. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 35 , 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/01608061.2015.1031430

Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., & Hayes, T. L. (2002). Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87 , 268–279. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.268

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Hendriks, M., Burger, M., & Commandeur, H. (2022). The influence of CEO compensation on employee engagement. Review of Managerial Science, 17 , 607–633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-022-00538-4

Herzberg, F., Mausner, B., & Snyderman, B. B. (1959). The motivation to work . John Wiley.

Hirsig, N., Rogovsky, N., & Elkin, M. (2014). Enterprise sustainability and HRM in small and medium-sized enterprises. In I. Ehnert, W. Harry, & K. Zink (Eds.), Sustainability and human resource management (pp. 127–152). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-37524-8_6

Hoeppe, J. C. (2014). Practitioner’s view on sustainability and HRM. In I. Ehnert, W. Harry, & K. Zink (Eds.), Sustainability and human resource management (pp. 273–294). Springer.