- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Action Research: What it is, Stages & Examples

The best way to get things accomplished is to do it yourself. This statement is utilized in corporations, community projects, and national governments. These organizations are relying on action research to cope with their continuously changing and unstable environments as they function in a more interdependent world.

In practical educational contexts, this involves using systematic inquiry and reflective practice to address real-world challenges, improve teaching and learning, enhance student engagement, and drive positive changes within the educational system.

This post outlines the definition of action research, its stages, and some examples.

Content Index

What is action research?

Stages of action research, the steps to conducting action research, examples of action research, advantages and disadvantages of action research.

Action research is a strategy that tries to find realistic solutions to organizations’ difficulties and issues. It is similar to applied research.

Action research refers basically learning by doing. First, a problem is identified, then some actions are taken to address it, then how well the efforts worked are measured, and if the results are not satisfactory, the steps are applied again.

It can be put into three different groups:

- Positivist: This type of research is also called “classical action research.” It considers research a social experiment. This research is used to test theories in the actual world.

- Interpretive: This kind of research is called “contemporary action research.” It thinks that business reality is socially made, and when doing this research, it focuses on the details of local and organizational factors.

- Critical: This action research cycle takes a critical reflection approach to corporate systems and tries to enhance them.

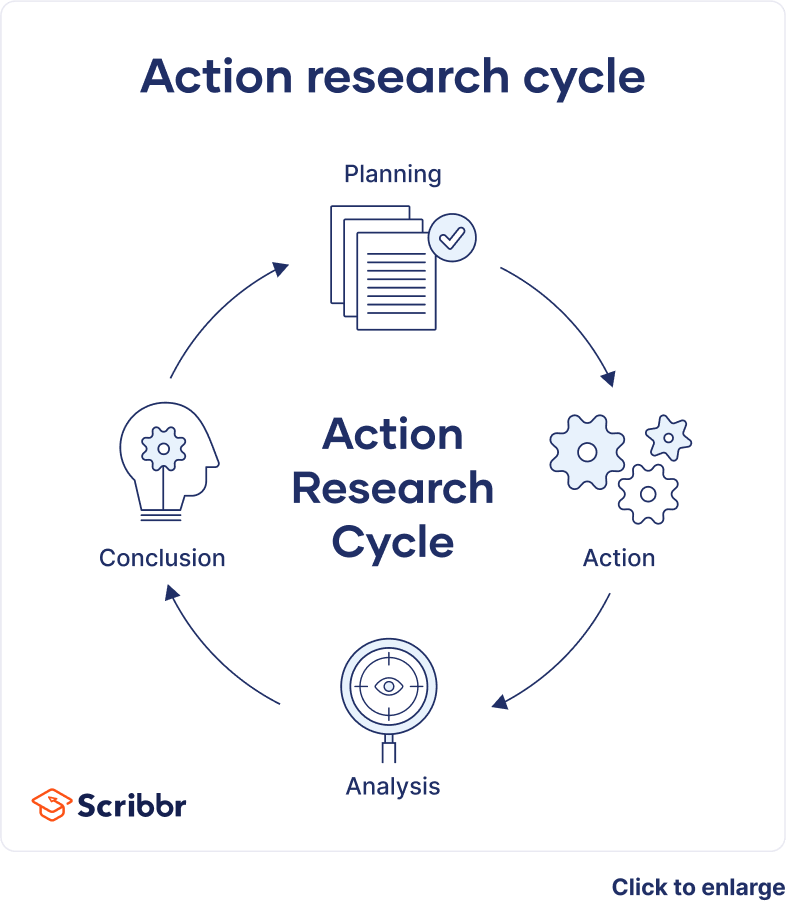

All research is about learning new things. Collaborative action research contributes knowledge based on investigations in particular and frequently useful circumstances. It starts with identifying a problem. After that, the research process is followed by the below stages:

Stage 1: Plan

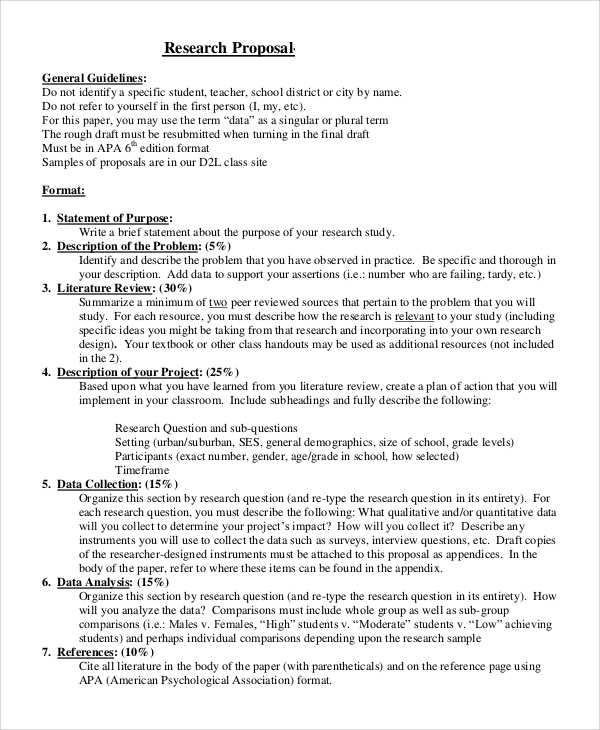

For an action research project to go well, the researcher needs to plan it well. After coming up with an educational research topic or question after a research study, the first step is to develop an action plan to guide the research process. The research design aims to address the study’s question. The research strategy outlines what to undertake, when, and how.

Stage 2: Act

The next step is implementing the plan and gathering data. At this point, the researcher must select how to collect and organize research data . The researcher also needs to examine all tools and equipment before collecting data to ensure they are relevant, valid, and comprehensive.

Stage 3: Observe

Data observation is vital to any investigation. The action researcher needs to review the project’s goals and expectations before data observation. This is the final step before drawing conclusions and taking action.

Different kinds of graphs, charts, and networks can be used to represent the data. It assists in making judgments or progressing to the next stage of observing.

Stage 4: Reflect

This step involves applying a prospective solution and observing the results. It’s essential to see if the possible solution found through research can really solve the problem being studied.

The researcher must explore alternative ideas when the action research project’s solutions fail to solve the problem.

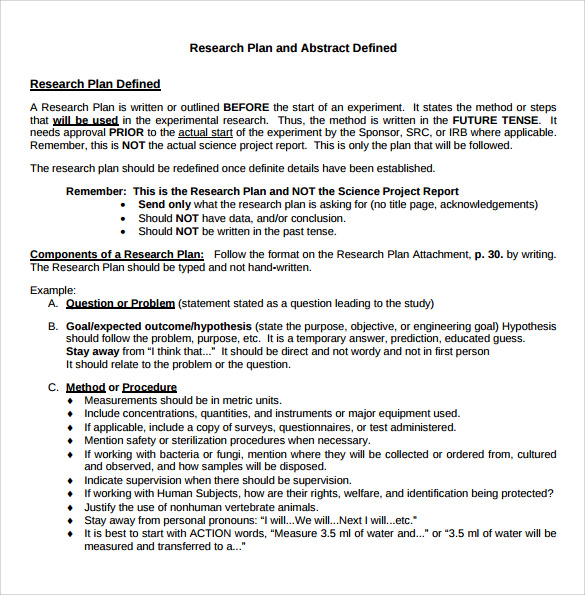

Action research is a systematic approach researchers, educators, and practitioners use to identify and address problems or challenges within a specific context. It involves a cyclical process of planning, implementing, reflecting, and adjusting actions based on the data collected. Here are the general steps involved in conducting an action research process:

Identify the action research question or problem

Clearly define the issue or problem you want to address through your research. It should be specific, actionable, and relevant to your working context.

Review existing knowledge

Conduct a literature review to understand what research has already been done on the topic. This will help you gain insights, identify gaps, and inform your research design.

Plan the research

Develop a research plan outlining your study’s objectives, methods, data collection tools, and timeline. Determine the scope of your research and the participants or stakeholders involved.

Collect data

Implement your research plan by collecting relevant data. This can involve various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, document analysis, or focus groups. Ensure that your data collection methods align with your research objectives and allow you to gather the necessary information.

Analyze the data

Once you have collected the data, analyze it using appropriate qualitative or quantitative techniques. Look for patterns, themes, or trends in the data that can help you understand the problem better.

Reflect on the findings

Reflect on the analyzed data and interpret the results in the context of your research question. Consider the implications and possible solutions that emerge from the data analysis. This reflection phase is crucial for generating insights and understanding the underlying factors contributing to the problem.

Develop an action plan

Based on your analysis and reflection, develop an action plan that outlines the steps you will take to address the identified problem. The plan should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART goals). Consider involving relevant stakeholders in planning to ensure their buy-in and support.

Implement the action plan

Put your action plan into practice by implementing the identified strategies or interventions. This may involve making changes to existing practices, introducing new approaches, or testing alternative solutions. Document the implementation process and any modifications made along the way.

Evaluate and monitor progress

Continuously monitor and evaluate the impact of your actions. Collect additional data, assess the effectiveness of the interventions, and measure progress towards your goals. This evaluation will help you determine if your actions have the desired effects and inform any necessary adjustments.

Reflect and iterate

Reflect on the outcomes of your actions and the evaluation results. Consider what worked well, what did not, and why. Use this information to refine your approach, make necessary adjustments, and plan for the next cycle of action research if needed.

Remember that participatory action research is an iterative process, and multiple cycles may be required to achieve significant improvements or solutions to the identified problem. Each cycle builds on the insights gained from the previous one, fostering continuous learning and improvement.

Explore Insightfully Contextual Inquiry in Qualitative Research

Here are two real-life examples of action research.

Action research initiatives are frequently situation-specific. Still, other researchers can adapt the techniques. The example is from a researcher’s (Franklin, 1994) report about a project encouraging nature tourism in the Caribbean.

In 1991, this was launched to study how nature tourism may be implemented on the four Windward Islands in the Caribbean: St. Lucia, Grenada, Dominica, and St. Vincent.

For environmental protection, a government-led action study determined that the consultation process needs to involve numerous stakeholders, including commercial enterprises.

First, two researchers undertook the study and held search conferences on each island. The search conferences resulted in suggestions and action plans for local community nature tourism sub-projects.

Several islands formed advisory groups and launched national awareness and community projects. Regional project meetings were held to discuss experiences, self-evaluations, and strategies. Creating a documentary about a local initiative helped build community. And the study was a success, leading to a number of changes in the area.

Lau and Hayward (1997) employed action research to analyze Internet-based collaborative work groups.

Over two years, the researchers facilitated three action research problem -solving cycles with 15 teachers, project personnel, and 25 health practitioners from diverse areas. The goal was to see how Internet-based communications might affect their virtual workgroup.

First, expectations were defined, technology was provided, and a bespoke workgroup system was developed. Participants suggested shorter, more dispersed training sessions with project-specific instructions.

The second phase saw the system’s complete deployment. The final cycle witnessed system stability and virtual group formation. The key lesson was that the learning curve was poorly misjudged, with frustrations only marginally met by phone-based technical help. According to the researchers, the absence of high-quality online material about community healthcare was harmful.

Role clarity, connection building, knowledge sharing, resource assistance, and experiential learning are vital for virtual group growth. More study is required on how group support systems might assist groups in engaging with their external environment and boost group members’ learning.

Action research has both good and bad points.

- It is very flexible, so researchers can change their analyses to fit their needs and make individual changes.

- It offers a quick and easy way to solve problems that have been going on for a long time instead of complicated, long-term solutions based on complex facts.

- If It is done right, it can be very powerful because it can lead to social change and give people the tools to make that change in ways that are important to their communities.

Disadvantages

- These studies have a hard time being generalized and are hard to repeat because they are so flexible. Because the researcher has the power to draw conclusions, they are often not thought to be theoretically sound.

- Setting up an action study in an ethical way can be hard. People may feel like they have to take part or take part in a certain way.

- It is prone to research errors like selection bias , social desirability bias, and other cognitive biases.

LEARN ABOUT: Self-Selection Bias

This post discusses how action research generates knowledge, its steps, and real-life examples. It is very applicable to the field of research and has a high level of relevance. We can only state that the purpose of this research is to comprehend an issue and find a solution to it.

At QuestionPro, we give researchers tools for collecting data, like our survey software, and a library of insights for any long-term study. Go to the Insight Hub if you want to see a demo or learn more about it.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

Frequently Asked Questions(FAQ’s)

Action research is a systematic approach to inquiry that involves identifying a problem or challenge in a practical context, implementing interventions or changes, collecting and analyzing data, and using the findings to inform decision-making and drive positive change.

Action research can be conducted by various individuals or groups, including teachers, administrators, researchers, and educational practitioners. It is often carried out by those directly involved in the educational setting where the research takes place.

The steps of action research typically include identifying a problem, reviewing relevant literature, designing interventions or changes, collecting and analyzing data, reflecting on findings, and implementing improvements based on the results.

MORE LIKE THIS

Why Multilingual 360 Feedback Surveys Provide Better Insights

Jun 3, 2024

Raked Weighting: A Key Tool for Accurate Survey Results

May 31, 2024

Top 8 Data Trends to Understand the Future of Data

May 30, 2024

Top 12 Interactive Presentation Software to Engage Your User

May 29, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Action Research: Steps, Benefits, and Tips

Introduction

History of action research, what is the definition of action research, types of action research, conducting action research.

Action research stands as a unique approach in the realm of qualitative inquiry in social science research. Rooted in real-world problems, it seeks not just to understand but also to act, bringing about positive change in specific contexts. Often distinguished by its collaborative nature, the action research process goes beyond traditional research paradigms by emphasizing the involvement of those being studied in resolving social conflicts and effecting positive change.

The value of action research lies not just in its outcomes, but also in the process itself, where stakeholders become active participants rather than mere subjects. In this article, we'll examine action research in depth, shedding light on its history, principles, and types of action research.

Tracing its roots back to the mid-20th century, Kurt Lewin developed classical action research as a response to traditional research methods in the social sciences that often sidelined the very communities they studied. Proponents of action research championed the idea that research should not just be an observational exercise but an actionable one that involves devising practical solutions. Advocates believed in the idea of research leading to immediate social action, emphasizing the importance of involving the community in the process.

Applications for action research

Over the years, action research has evolved and diversified. From its early applications in social psychology and organizational development, it has branched out into various fields such as education, healthcare, and community development, informing questions around improving schools, minority problems, and more. This growth wasn't just in application, but also in its methodologies.

How is action research different?

Like all research methodologies, effective action research generates knowledge. However, action research stands apart in its commitment to instigate tangible change. Traditional research often places emphasis on passive observation , employing data collection methods primarily to contribute to broader theoretical frameworks . In contrast, action research is inherently proactive, intertwining the acts of observing and acting.

The primary goal isn't just to understand a problem but to solve or alleviate it. Action researchers partner closely with communities, ensuring that the research process directly benefits those involved. This collaboration often leads to immediate interventions, tweaks, or solutions applied in real-time, marking a departure from other forms of research that might wait until the end of a study to make recommendations.

This proactive, change-driven nature makes action research particularly impactful in settings where immediate change is not just beneficial but essential.

Action research is best understood as a systematic approach to cooperative inquiry. Unlike traditional research methodologies that might primarily focus on generating knowledge, action research emphasizes producing actionable solutions for pressing real-world challenges.

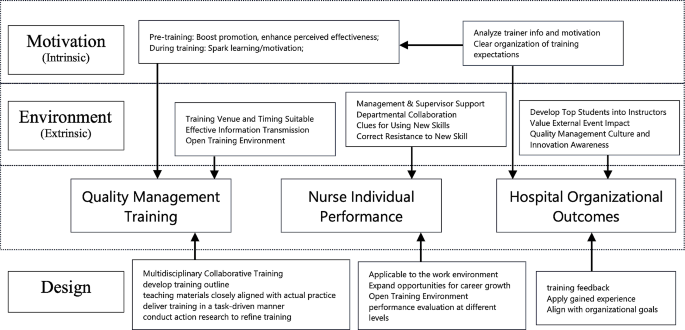

This form of research undertakes a cyclic and reflective journey, typically cycling through stages of planning , acting, observing, and reflecting. A defining characteristic of action research is the collaborative spirit it embodies, often dissolving the rigid distinction between the researcher and the researched, leading to mutual learning and shared outcomes.

Advantages of action research

One of the foremost benefits of action research is the immediacy of its application. Since the research is embedded within real-world issues, any findings or solutions derived can often be integrated straightaway, catalyzing prompt improvements within the concerned community or organization. This immediacy is coupled with the empowering nature of the methodology. Participants aren't mere subjects; they actively shape the research process, giving them a tangible sense of ownership over both the research journey and its eventual outcomes.

Moreover, the inherent adaptability of action research allows researchers to tweak their approaches responsively based on live feedback. This ensures the research remains rooted in the evolving context, capturing the nuances of the situation and making any necessary adjustments. Lastly, this form of research tends to offer a comprehensive understanding of the issue at hand, harmonizing socially constructed theoretical knowledge with hands-on insights, leading to a richer, more textured understanding.

Disadvantages of action research

Like any methodology, action research isn't devoid of challenges. Its iterative nature, while beneficial, can extend timelines. Researchers might find themselves engaged in multiple cycles of observation, reflection, and action before arriving at a satisfactory conclusion. The intimate involvement of the researcher with the research participants, although crucial for collaboration, opens doors to potential conflicts. Through collaborative problem solving, disagreements can lead to richer and more nuanced solutions, but it can take considerable time and effort.

Another limitation stems from its focus on a specific context: results derived from a particular action research project might not always resonate or be applicable in a different context or with a different group. Lastly, the depth of collaboration this methodology demands means all stakeholders need to be deeply invested, and such a level of commitment might not always be feasible.

Examples of action research

To illustrate, let's consider a few scenarios. Imagine a classroom where a teacher observes dwindling student participation. Instead of sticking to conventional methods, the teacher experiments with introducing group-based activities. As the outcomes unfold, the teacher continually refines the approach based on student feedback, eventually leading to a teaching strategy that rejuvenates student engagement.

In a healthcare context, hospital staff who recognize growing patient anxiety related to certain procedures might innovate by introducing a new patient-informing protocol. As they study the effects of this change, they could, through iterations, sculpt a procedure that diminishes patient anxiety.

Similarly, in the realm of community development, a community grappling with the absence of child-friendly public spaces might collaborate with local authorities to conceptualize a park. As they monitor its utilization and societal impact, continual feedback could refine the park's infrastructure and design.

Contemporary action research, while grounded in the core principles of collaboration, reflection, and change, has seen various adaptations tailored to the specific needs of different contexts and fields. These adaptations have led to the emergence of distinct types of action research, each with its unique emphasis and approach.

Collaborative action research

Collaborative action research emphasizes the joint efforts of professionals, often from the same field, working together to address common concerns or challenges. In this approach, there's a strong emphasis on shared responsibility, mutual respect, and co-learning. For example, a group of classroom teachers might collaboratively investigate methods to improve student literacy, pooling their expertise and resources to devise, implement, and refine strategies for improving teaching.

Participatory action research

Participatory action research (PAR) goes a step further in dissolving the barriers between the researcher and the researched. It actively involves community members or stakeholders not just as participants, but as equal partners in the entire research process. PAR is deeply democratic and seeks to empower participants, fostering a sense of agency and ownership. For instance, a participatory research project might involve local residents in studying and addressing community health concerns, ensuring that the research process and outcomes are both informed by and beneficial to the community itself.

Educational action research

Educational action research is tailored specifically to practical educational contexts. Here, educators take on the dual role of teacher and researcher, seeking to improve teaching practices, curricula, classroom dynamics, or educational evaluation. This type of research is cyclical, with educators implementing changes, observing outcomes, and reflecting on results to continually enhance the educational experience. An example might be a teacher studying the impact of technology integration in her classroom, adjusting strategies based on student feedback and learning outcomes.

Community-based action research

Another noteworthy type is community-based action research, which focuses primarily on community development and well-being. Rooted in the principles of social justice, this approach emphasizes the collective power of community members to identify, study, and address their challenges. It's particularly powerful in grassroots movements and local development projects where community insights and collaboration drive meaningful, sustainable change.

Key insights and critical reflection through research with ATLAS.ti

Organize all your data analysis and insights with our powerful interface. Download a free trial today.

Engaging in action research is both an enlightening and transformative journey, rooted in practicality yet deeply connected to theory. For those embarking on this path, understanding the essentials of an action research study and the significance of a research cycle is paramount.

Understanding the action research cycle

At the heart of action research is its cycle, a structured yet adaptable framework guiding the research. This cycle embodies the iterative nature of action research, emphasizing that learning and change evolve through repetition and reflection.

The typical stages include:

- Identifying a problem : This is the starting point where the action researcher pinpoints a pressing issue or challenge that demands attention.

- Planning : Here, the researcher devises an action research strategy aimed at addressing the identified problem. In action research, network resources, participant consultation, and the literature review are core components in planning.

- Action : The planned strategies are then implemented in this stage. This 'action' phase is where theoretical knowledge meets practical application.

- Observation : Post-implementation, the researcher observes the outcomes and effects of the action. This stage ensures that the research remains grounded in the real-world context.

- Critical reflection : This part of the cycle involves analyzing the observed results to draw conclusions about their effectiveness and identify areas for improvement.

- Revision : Based on the insights from reflection, the initial plan is revised, marking the beginning of another cycle.

Rigorous research and iteration

It's essential to understand that while action research is deeply practical, it doesn't sacrifice rigor . The cyclical process ensures that the research remains thorough and robust. Each iteration of the cycle in an action research project refines the approach, drawing it closer to an effective solution.

The role of the action researcher

The action researcher stands at the nexus of theory and practice. Not just an observer, the researcher actively engages with the study's participants, collaboratively navigating through the research cycle by conducting interviews, participant observations, and member checking . This close involvement ensures that the study remains relevant, timely, and responsive.

Drawing conclusions and informing theory

As the research progresses through multiple iterations of data collection and data analysis , drawing conclusions becomes an integral aspect. These conclusions, while immediately beneficial in addressing the practical issue at hand, also serve a broader purpose. They inform theory, enriching the academic discourse and providing valuable insights for future research.

Identifying actionable insights

Keep in mind that action research should facilitate implications for professional practice as well as space for systematic inquiry. As you draw conclusions about the knowledge generated from action research, consider how this knowledge can create new forms of solutions to the pressing concern you set out to address.

Collecting data and analyzing data starts with ATLAS.ti

Download a free trial of our intuitive software to make the most of your research.

- Section 2: Home

- Developing the Quantitative Research Design

- Qualitative Descriptive Design

- Design and Development Research (DDR) For Instructional Design

- Qualitative Narrative Inquiry Research

- Action Research Resource

What is Action Research?

Considerations, creating a plan of action.

- Case Study Design in an Applied Doctorate

- SAGE Research Methods

- Research Examples (SAGE) This link opens in a new window

- Dataset Examples (SAGE) This link opens in a new window

- IRB Resource Center This link opens in a new window

Action research is a qualitative method that focuses on solving problems in social systems, such as schools and other organizations. The emphasis is on solving the presenting problem by generating knowledge and taking action within the social system in which the problem is located. The goal is to generate shared knowledge of how to address the problem by bridging the theory-practice gap (Bourner & Brook, 2019). A general definition of action research is the following: “Action research brings together action and reflection, as well as theory and practice, in participation with others, in the pursuit of practical solutions to issues of pressing concern” (Bradbury, 2015, p. 1). Johnson (2019) defines action research in the field of education as “the process of studying a school, classroom, or teacher-learning situation with the purpose of understanding and improving the quality of actions or instruction” (p.255).

Origins of Action Research

Kurt Lewin is typically credited with being the primary developer of Action Research in the 1940s. Lewin stated that action research can “transform…unrelated individuals, frequently opposed in their outlook and their interests, into cooperative teams, not on the basis of sweetness but on the basis of readiness to face difficulties realistically, to apply honest fact-finding, and to work together to overcome them” (1946, p.211).

Sample Action Research Topics

Some sample action research topics might be the following:

- Examining how classroom teachers perceive and implement new strategies in the classroom--How is the strategy being used? How do students respond to the strategy? How does the strategy inform and change classroom practices? Does the new skill improve test scores? Do classroom teachers perceive the strategy as effective for student learning?

- Examining how students are learning a particular content or objectives--What seems to be effective in enhancing student learning? What skills need to be reinforced? How do students respond to the new content? What is the ability of students to understand the new content?

- Examining how education stakeholders (administrator, parents, teachers, students, etc.) make decisions as members of the school’s improvement team--How are different stakeholders encouraged to participate? How is power distributed? How is equity demonstrated? How is each voice valued? How are priorities and initiatives determined? How does the team evaluate its processes to determine effectiveness?

- Examining the actions that school staff take to create an inclusive and welcoming school climate--Who makes and implements the actions taken to create the school climate? Do members of the school community (teachers, staff, students) view the school climate as inclusive? Do members of the school community feel welcome in the school? How are members of the school community encouraged to become involved in school activities? What actions can school staff take to help others feel a part of the school community?

- Examining the perceptions of teachers with regard to the learning strategies that are more effective with special populations, such as special education students, English Language Learners, etc.—What strategies are perceived to be more effective? How do teachers plan instructionally for unique learners such as special education students or English Language Learners? How do teachers deal with the challenges presented by unique learners such as special education students or English Language Learners? What supports do teachers need (e.g., professional development, training, coaching) to more effectively deliver instruction to unique learners such as special education students or English Language Learners?

Remember—The goal of action research is to find out how individuals perceive and act in a situation so the researcher can develop a plan of action to improve the educational organization. While these topics listed here can be explored using other research designs, action research is the design to use if the outcome is to develop a plan of action for addressing and improving upon a situation in the educational organization.

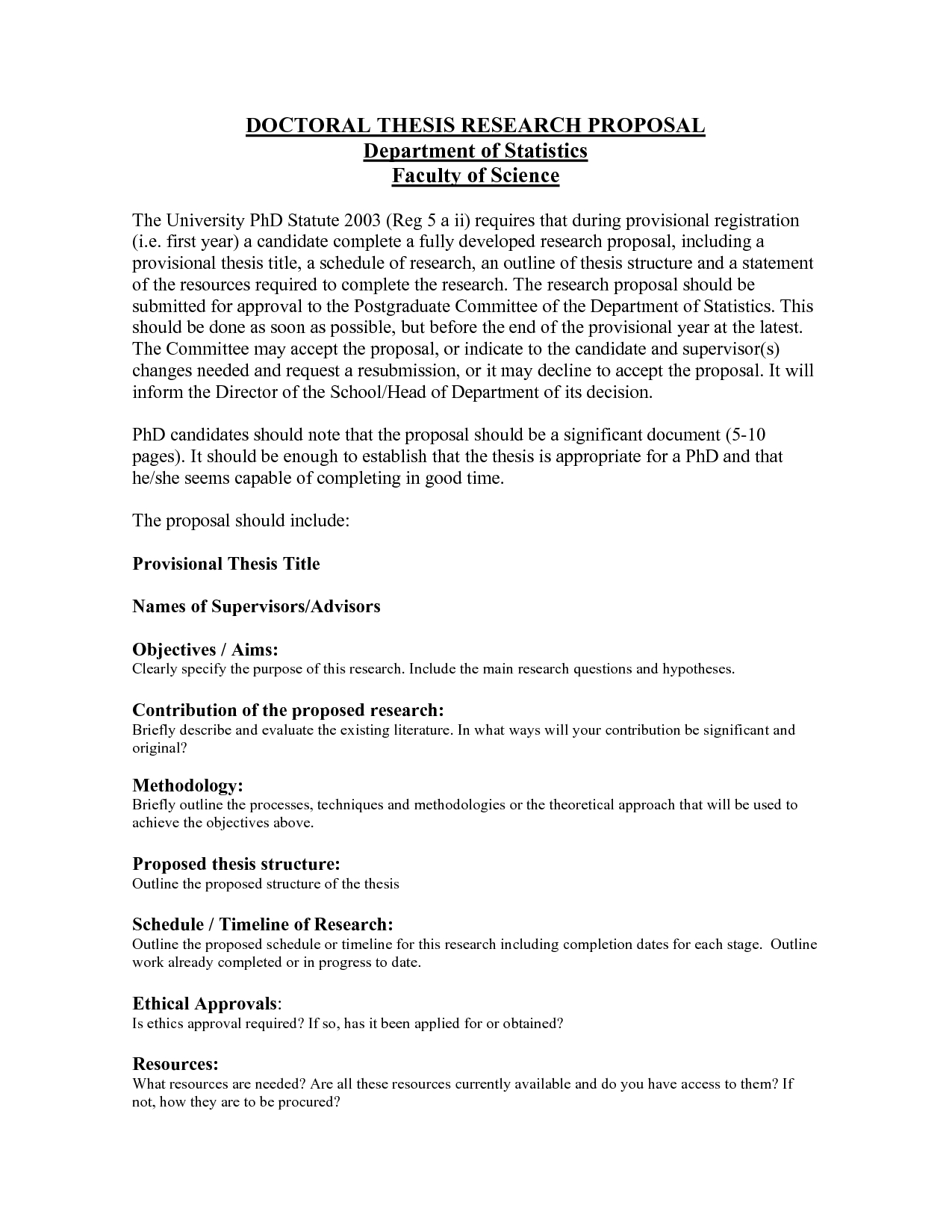

Considerations for Determining Whether to Use Action Research in an Applied Dissertation

- When considering action research, first determine the problem and the change that needs to occur as a result of addressing the problem (i.e., research problem and research purpose). Remember, the goal of action research is to change how individuals address a particular problem or situation in a way that results in improved practices.

- If the study will be conducted at a school site or educational organization, you may need site permission. Determine whether site permission will be given to conduct the study.

- Consider the individuals who will be part of the data collection (e.g., teachers, administrators, parents, other school staff, etc.). Will there be a representative sample willing to participate in the research?

- If students will be part of the study, does parent consent and student assent need to be obtained?

- As you develop your data collection plan, also consider the timeline for data collection. Is it feasible? For example, if you will be collecting data in a school, consider winter and summer breaks, school events, testing schedules, etc.

- As you develop your data collection plan, consult with your dissertation chair, Subject Matter Expert, NU Academic Success Center, and the NU IRB for resources and guidance.

- Action research is not an experimental design, so you are not trying to accept or reject a hypothesis. There are no independent or dependent variables. It is not generalizable to a larger setting. The goal is to understand what is occurring in the educational setting so that a plan of action can be developed for improved practices.

Considerations for Action Research

Below are some things to consider when developing your applied dissertation proposal using Action Research (adapted from Johnson, 2019):

- Research Topic and Research Problem -- Decide the topic to be studied and then identify the problem by defining the issue in the learning environment. Use references from current peer-reviewed literature for support.

- Purpose of the Study —What need to be different or improved as a result of the study?

- Research Questions —The questions developed should focus on “how” or “what” and explore individuals’ experiences, beliefs, and perceptions.

- Theoretical Framework -- What are the existing theories (theoretical framework) or concepts (conceptual framework) that can be used to support the research. How does existing theory link to what is happening in the educational environment with regard to the topic? What theories have been used to support similar topics in previous research?

- Literature Review -- Examine the literature, focusing on peer-reviewed studies published in journal within the last five years, with the exception of seminal works. What about the topic has already been explored and examined? What were the findings, implications, and limitations of previous research? What is missing from the literature on the topic? How will your proposed research address the gap in the literature?

- Data Collection —Who will be part of the sample for data collection? What data will be collected from the individuals in the study (e.g., semi-structured interviews, surveys, etc.)? What are the educational artifacts and documents that need to be collected (e.g., teacher less plans, student portfolios, student grades, etc.)? How will they be collected and during what timeframe? (Note--A list of sample data collection methods appears under the heading of “Sample Instrumentation.”)

- Data Analysis —Determine how the data will be analyzed. Some types of analyses that are frequently used for action research include thematic analysis and content analysis.

- Implications —What conclusions can be drawn based upon the findings? How do the findings relate to the existing literature and inform theory in the field of education?

- Recommendations for Practice--Create a Plan of Action— This is a critical step in action research. A plan of action is created based upon the data analysis, findings, and implications. In the Applied Dissertation, this Plan of Action is included with the Recommendations for Practice. The includes specific steps that individuals should take to change practices; recommendations for how those changes will occur (e.g., professional development, training, school improvement planning, committees to develop guidelines and policies, curriculum review committee, etc.); and methods to evaluate the plan’s effectiveness.

- Recommendations for Research —What should future research focus on? What type of studies need to be conducted to build upon or further explore your findings.

- Professional Presentation or Defense —This is where the findings will be presented in a professional presentation or defense as the culmination of your research.

Adapted from Johnson (2019).

Considerations for Sampling and Data Collection

Below are some tips for sampling, sample size, data collection, and instrumentation for Action Research:

Sampling and Sample Size

Action research uses non-probability sampling. This is most commonly means a purposive sampling method that includes specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. However, convenience sampling can also be used (e.g., a teacher’s classroom).

Critical Concepts in Data Collection

Triangulation- - Dosemagen and Schwalbach (2019) discussed the importance of triangulation in Action Research which enhances the trustworthiness by providing multiple sources of data to analyze and confirm evidence for findings.

Trustworthiness —Trustworthiness assures that research findings are fulfill four critical elements—credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability. Reflect on the following: Are there multiple sources of data? How have you ensured credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability? Have the assumptions, limitations, and delimitations of the study been identified and explained? Was the sample a representative sample for the study? Did any individuals leave the study before it ended? How have you controlled researcher biases and beliefs? Are you drawing conclusions that are not supported by data? Have all possible themes been considered? Have you identified other studies with similar results?

Sample Instrumentation

Below are some of the possible methods for collecting action research data:

- Pre- and Post-Surveys for students and/or staff

- Staff Perception Surveys and Questionnaires

- Semi-Structured Interviews

- Focus Groups

- Observations

- Document analysis

- Student work samples

- Classroom artifacts, such as teacher lesson plans, rubrics, checklists, etc.

- Attendance records

- Discipline data

- Journals from students and/or staff

- Portfolios from students and/or staff

A benefit of Action Research is its potential to influence educational practice. Many educators are, by nature of the profession, reflective, inquisitive, and action-oriented. The ultimate outcome of Action Research is to create a plan of action using the research findings to inform future educational practice. A Plan of Action is not meant to be a one-size fits all plan. Instead, it is mean to include specific data-driven and research-based recommendations that result from a detailed analysis of the data, the study findings, and implications of the Action Research study. An effective Plan of Action includes an evaluation component and opportunities for professional educator reflection that allows for authentic discussion aimed at continuous improvement.

When developing a Plan of Action, the following should be considered:

- How can this situation be approached differently in the future?

- What should change in terms of practice?

- What are the specific steps that individuals should take to change practices?

- What is needed to implement the changes being recommended (professional development, training, materials, resources, planning committees, school improvement planning, etc.)?

- How will the effectiveness of the implemented changes be evaluated?

- How will opportunities for professional educator reflection be built into the Action Plan?

Sample Action Research Studies

Anderson, A. J. (2020). A qualitative systematic review of youth participatory action research implementation in U.S. high schools. A merican Journal of Community Psychology, 65 (1/2), 242–257. https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.proxy1.ncu.edu/doi/epdf/10.1002/ajcp.12389

Ayvaz, Ü., & Durmuş, S.(2021). Fostering mathematical creativity with problem posing activities: An action research with gifted students. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 40. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselp&AN=S1871187121000614&site=eds-live

Bellino, M. J. (2018). Closing information gaps in Kakuma Refugee Camp: A youth participatory action research study. American Journal of Community Psychology, 62 (3/4), 492–507. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ofs&AN=133626988&site=eds-live

Beneyto, M., Castillo, J., Collet-Sabé, J., & Tort, A. (2019). Can schools become an inclusive space shared by all families? Learnings and debates from an action research project in Catalonia. Educational Action Research, 27 (2), 210–226. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=135671904&site=eds-live

Bilican, K., Senler, B., & Karısan, D. (2021). Fostering teacher educators’ professional development through collaborative action research. International Journal of Progressive Education, 17 (2), 459–472. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=149828364&site=eds-live

Black, G. L. (2021). Implementing action research in a teacher preparation program: Opportunities and limitations. Canadian Journal of Action Research, 21 (2), 47–71. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=149682611&site=eds-live

Bozkuş, K., & Bayrak, C. (2019). The Application of the dynamic teacher professional development through experimental action research. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 11 (4), 335–352. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=135580911&site=eds-live

Christ, T. W. (2018). Mixed methods action research in special education: An overview of a grant-funded model demonstration project. Research in the Schools, 25( 2), 77–88. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=135047248&site=eds-live

Jakhelln, R., & Pörn, M. (2019). Challenges in supporting and assessing bachelor’s theses based on action research in initial teacher education. Educational Action Research, 27 (5), 726–741. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=140234116&site=eds-live

Klima Ronen, I. (2020). Action research as a methodology for professional development in leading an educational process. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 64 . https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselp&AN=S0191491X19302159&site=eds-live

Messiou, K. (2019). Collaborative action research: facilitating inclusion in schools. Educational Action Research, 27 (2), 197–209. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=135671898&site=eds-live

Mitchell, D. E. (2018). Say it loud: An action research project examining the afrivisual and africology, Looking for alternative African American community college teaching strategies. Journal of Pan African Studies, 12 (4), 364–487. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ofs&AN=133155045&site=eds-live

Pentón Herrera, L. J. (2018). Action research as a tool for professional development in the K-12 ELT classroom. TESL Canada Journal, 35 (2), 128–139. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ofs&AN=135033158&site=eds-live

Rodriguez, R., Macias, R. L., Perez-Garcia, R., Landeros, G., & Martinez, A. (2018). Action research at the intersection of structural and family violence in an immigrant Latino community: a youth-led study. Journal of Family Violence, 33 (8), 587–596. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ccm&AN=132323375&site=eds-live

Vaughan, M., Boerum, C., & Whitehead, L. (2019). Action research in doctoral coursework: Perceptions of independent research experiences. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 13 . https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsdoj&AN=edsdoj.17aa0c2976c44a0991e69b2a7b4f321&site=eds-live

Sample Journals for Action Research

Educational Action Research

Canadian Journal of Action Research

Sample Resource Videos

Call-Cummings, M. (2017). Researching racism in schools using participatory action research [Video]. Sage Research Methods http://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?URL=https://methods.sagepub.com/video/researching-racism-in-schools-using-participatory-action-research

Fine, M. (2016). Michelle Fine discusses community based participatory action research [Video]. Sage Knowledge. http://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?URL=https://sk-sagepub-com.proxy1.ncu.edu/video/michelle-fine-discusses-community-based-participatory-action-research

Getz, C., Yamamura, E., & Tillapaugh. (2017). Action Research in Education. [Video]. You Tube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X2tso4klYu8

Bradbury, H. (Ed.). (2015). The handbook of action research (3rd edition). Sage.

Bradbury, H., Lewis, R. & Embury, D.C. (2019). Education action research: With and for the next generation. In C.A. Mertler (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of action research in education (1st edition). John Wiley and Sons. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nu/reader.action?docID=5683581&ppg=205

Bourner, T., & Brook, C. (2019). Comparing and contrasting action research and action learning. In C.A. Mertler (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of action research in education (1st edition). John Wiley and Sons. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nu/reader.action?docID=5683581&ppg=205

Bradbury, H. (2015). The Sage handbook of action research . Sage. https://www-doi-org.proxy1.ncu.edu/10.4135/9781473921290

Dosemagen, D.M. & Schwalback, E.M. (2019). Legitimacy of and value in action research. In C.A. Mertler (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of action research in education (1st edition). John Wiley and Sons. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nu/reader.action?docID=5683581&ppg=205

Johnson, A. (2019). Action research for teacher professional development. In C.A. Mertler (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of action research in education (1st edition). John Wiley and Sons. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nu/reader.action?docID=5683581&ppg=205

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. In G.W. Lewin (Ed.), Resolving social conflicts: Selected papers on group dynamics (compiled in 1948). Harper and Row.

Mertler, C. A. (Ed.). (2019). The Wiley handbook of action research in education. John Wiley and Sons. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nu/detail.action?docID=5683581

- << Previous: Qualitative Narrative Inquiry Research

- Next: Case Study Design in an Applied Doctorate >>

- Last Updated: Jul 28, 2023 8:05 AM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/c.php?g=1013605

© Copyright 2024 National University. All Rights Reserved.

Privacy Policy | Consumer Information

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

The Action Research Process

Module 1: Action Research

There are various models of the action research process. Some models are simple in their design while others appear relatively complex. Essentially, most of the models share similar elements with small variations.

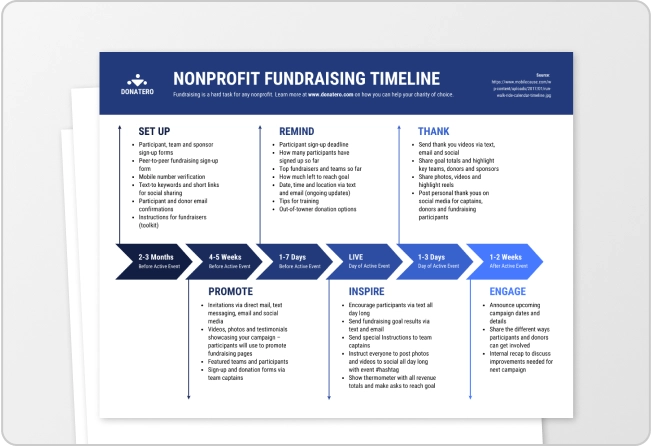

Action research models begin with the central problem or topic. They involve some observation or monitoring of current practice, followed by the collection and synthesis of information and data. Finally, some sort of action is taken, which then serves as a basis for the next stage of action research (Mills 2011).

- Central Problem / Topic

- Observation / Monitoring

- Collection of Data

- Action Taken

In this course, we will define the action research process as composed of four stages and nine steps:

Image Hotspots

Action Research Process

Click each + icon to expand the steps of the stage:

It is important to note that action research is a flexible, iterative process of continuous improvement, emphasizing adaptability and responsiveness to findings at each cycle.

Kurt Lewin’s approach to action research involves a cyclical, spiral process consisting of several stages, each comprising planning, action, and reviewing the results of the action. This method is aligned with Dewey’s concept of experiential learning and is particularly suited to solving problems in social and organizational contexts.

Action Research Handbook Copyright © by Dr. Zabedia Nazim and Dr. Sowmya Venkat-Kishore is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Introduction: What Is Action Research?

- First Online: 07 June 2023

Cite this chapter

- Martin Dege 3

Part of the book series: Theory and History in the Human and Social Sciences ((THHSS))

230 Accesses

Gives a brief overview of the concepts, traditions, and theoretical underpinnings of action research. Provides first attempts at defining the field and shows conceptual problems and pitfalls within the action research traditions. Shows how Critical Psychology intercepts with Action Research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Fals Borda, O., & Rahman, M. A. (Eds.). (1991). Action and knowledge: Breaking the monopoly with participatory action research . Apex.

Google Scholar

Greenwood, D., & Levin, M. (2007). Introduction to action research: Social research for social change (2nd ed.). Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Gustavsen, B. (1992). Dialogue and development: Theory of communication, action research and the restructuring of working life . Van Gorcum.

Habermas, J. (1978). Einige Schwierigkeiten beim Versuch, Theorie und Praxis zu vermitteln. In Theorie und Praxis: Sozialphilosophische Studien (pp. 9–47). Suhrkamp.

Johansson, A. W., & Lindhult, E. (2008). Emancipation or workability?: Critical versus pragmatic scientific orientation in action research. Action Research, 6 (1), 95–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750307083713

Article Google Scholar

Kapoor, I. (2002). The devil’s in the theory: A critical assessment of Robert Chambers’ work on participatory development. Third World Quarterly, 23 (1), 101–117. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=5801768&site=ehost-live

Markard, M. (1991). Methodik subjektwissenschaftlicher Forschung: Jenseits des Streits um quantitative und qualitative Verfahren . Argument Verlag.

Markard, M. (2009). Einführung in die Kritische Psychologie: Grundlagen, Methoden und Problemfelder marxistischer Subjektwissenschaft . Argument Verlag.

Marx, K., Engels, F., & Harvey, D. (2008). The communist manifesto (S. Moore, Trans.). Pluto Press. (Original work published in 1848).

Moser, H. (1978). Einige Aspekte der Aktionsforschung im internationalen Vergleich. In H. Moser & H. Ornauer (Eds.), Internationale Aspekte der Aktionsforschung (pp. 173–189). Kösel.

Tolman, C. W. (1994). Psychology, society, and subjectivity: An introduction to German critical psychology . Routledge.

Whyte, W.F. (1991). Participatory action research . Sage.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Social Science and Cultural Studies, Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, NY, USA

Martin Dege

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Dege, M. (2023). Introduction: What Is Action Research?. In: Action Research and Critical Psychology. Theory and History in the Human and Social Sciences. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31197-0_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31197-0_1

Published : 07 June 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-31196-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-31197-0

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

education, community-building and change

What is action research and how do we do it?

In this article, we explore the development of some different traditions of action research and provide an introductory guide to the literature.

Contents : what is action research · origins · the decline and rediscovery of action research · undertaking action research · conclusion · further reading · how to cite this article . see, also: research for practice ., what is action research.

In the literature, discussion of action research tends to fall into two distinctive camps. The British tradition – especially that linked to education – tends to view action research as research-oriented toward the enhancement of direct practice. For example, Carr and Kemmis provide a classic definition:

Action research is simply a form of self-reflective enquiry undertaken by participants in social situations in order to improve the rationality and justice of their own practices, their understanding of these practices, and the situations in which the practices are carried out (Carr and Kemmis 1986: 162).

Many people are drawn to this understanding of action research because it is firmly located in the realm of the practitioner – it is tied to self-reflection. As a way of working it is very close to the notion of reflective practice coined by Donald Schön (1983).

The second tradition, perhaps more widely approached within the social welfare field – and most certainly the broader understanding in the USA is of action research as ‘the systematic collection of information that is designed to bring about social change’ (Bogdan and Biklen 1992: 223). Bogdan and Biklen continue by saying that its practitioners marshal evidence or data to expose unjust practices or environmental dangers and recommend actions for change. In many respects, for them, it is linked into traditions of citizen’s action and community organizing. The practitioner is actively involved in the cause for which the research is conducted. For others, it is such commitment is a necessary part of being a practitioner or member of a community of practice. Thus, various projects designed to enhance practice within youth work, for example, such as the detached work reported on by Goetschius and Tash (1967) could be talked of as action research.

Kurt Lewin is generally credited as the person who coined the term ‘action research’:

The research needed for social practice can best be characterized as research for social management or social engineering. It is a type of action-research, a comparative research on the conditions and effects of various forms of social action, and research leading to social action. Research that produces nothing but books will not suffice (Lewin 1946, reproduced in Lewin 1948: 202-3)

His approach involves a spiral of steps, ‘each of which is composed of a circle of planning, action and fact-finding about the result of the action’ ( ibid. : 206). The basic cycle involves the following:

This is how Lewin describes the initial cycle:

The first step then is to examine the idea carefully in the light of the means available. Frequently more fact-finding about the situation is required. If this first period of planning is successful, two items emerge: namely, “an overall plan” of how to reach the objective and secondly, a decision in regard to the first step of action. Usually this planning has also somewhat modified the original idea. ( ibid. : 205)

The next step is ‘composed of a circle of planning, executing, and reconnaissance or fact-finding for the purpose of evaluating the results of the second step, and preparing the rational basis for planning the third step, and for perhaps modifying again the overall plan’ ( ibid. : 206). What we can see here is an approach to research that is oriented to problem-solving in social and organizational settings, and that has a form that parallels Dewey’s conception of learning from experience.

The approach, as presented, does take a fairly sequential form – and it is open to a literal interpretation. Following it can lead to practice that is ‘correct’ rather than ‘good’ – as we will see. It can also be argued that the model itself places insufficient emphasis on analysis at key points. Elliott (1991: 70), for example, believed that the basic model allows those who use it to assume that the ‘general idea’ can be fixed in advance, ‘that “reconnaissance” is merely fact-finding, and that “implementation” is a fairly straightforward process’. As might be expected there was some questioning as to whether this was ‘real’ research. There were questions around action research’s partisan nature – the fact that it served particular causes.

The decline and rediscovery of action research

Action research did suffer a decline in favour during the 1960s because of its association with radical political activism (Stringer 2007: 9). There were, and are, questions concerning its rigour, and the training of those undertaking it. However, as Bogdan and Biklen (1992: 223) point out, research is a frame of mind – ‘a perspective that people take toward objects and activities’. Once we have satisfied ourselves that the collection of information is systematic and that any interpretations made have a proper regard for satisfying truth claims, then much of the critique aimed at action research disappears. In some of Lewin’s earlier work on action research (e.g. Lewin and Grabbe 1945), there was a tension between providing a rational basis for change through research, and the recognition that individuals are constrained in their ability to change by their cultural and social perceptions, and the systems of which they are a part. Having ‘correct knowledge’ does not of itself lead to change, attention also needs to be paid to the ‘matrix of cultural and psychic forces’ through which the subject is constituted (Winter 1987: 48).

Subsequently, action research has gained a significant foothold both within the realm of community-based, and participatory action research; and as a form of practice-oriented to the improvement of educative encounters (e.g. Carr and Kemmis 1986).

Exhibit 1: Stringer on community-based action research

A fundamental premise of community-based action research is that it commences with an interest in the problems of a group, a community, or an organization. Its purpose is to assist people in extending their understanding of their situation and thus resolving problems that confront them….

Community-based action research is always enacted through an explicit set of social values. In modern, democratic social contexts, it is seen as a process of inquiry that has the following characteristics:

• It is democratic , enabling the participation of all people.

• It is equitable , acknowledging people’s equality of worth.

• It is liberating , providing freedom from oppressive, debilitating conditions.

• It is life enhancing , enabling the expression of people’s full human potential.

(Stringer 1999: 9-10)

Undertaking action research

As Thomas (2017: 154) put it, the central aim is change, ‘and the emphasis is on problem-solving in whatever way is appropriate’. It can be seen as a conversation rather more than a technique (McNiff et. al. ). It is about people ‘thinking for themselves and making their own choices, asking themselves what they should do and accepting the consequences of their own actions’ (Thomas 2009: 113).

The action research process works through three basic phases:

Look -building a picture and gathering information. When evaluating we define and describe the problem to be investigated and the context in which it is set. We also describe what all the participants (educators, group members, managers etc.) have been doing.

Think – interpreting and explaining. When evaluating we analyse and interpret the situation. We reflect on what participants have been doing. We look at areas of success and any deficiencies, issues or problems.

Act – resolving issues and problems. In evaluation we judge the worth, effectiveness, appropriateness, and outcomes of those activities. We act to formulate solutions to any problems. (Stringer 1999: 18; 43-44;160)

The use of action research to deepen and develop classroom practice has grown into a strong tradition of practice (one of the first examples being the work of Stephen Corey in 1949). For some, there is an insistence that action research must be collaborative and entail groupwork.

Action research is a form of collective self-reflective enquiry undertaken by participants in social situations in order to improve the rationality and justice of their own social or educational practices, as well as their understanding of those practices and the situations in which the practices are carried out… The approach is only action research when it is collaborative, though it is important to realise that action research of the group is achieved through the critically examined action of individual group members. (Kemmis and McTaggart 1988: 5-6)

Just why it must be collective is open to some question and debate (Webb 1996), but there is an important point here concerning the commitments and orientations of those involved in action research.

One of the legacies Kurt Lewin left us is the ‘action research spiral’ – and with it there is the danger that action research becomes little more than a procedure. It is a mistake, according to McTaggart (1996: 248) to think that following the action research spiral constitutes ‘doing action research’. He continues, ‘Action research is not a ‘method’ or a ‘procedure’ for research but a series of commitments to observe and problematize through practice a series of principles for conducting social enquiry’. It is his argument that Lewin has been misunderstood or, rather, misused. When set in historical context, while Lewin does talk about action research as a method, he is stressing a contrast between this form of interpretative practice and more traditional empirical-analytic research. The notion of a spiral may be a useful teaching device – but it is all too easy to slip into using it as the template for practice (McTaggart 1996: 249).

Further reading

This select, annotated bibliography has been designed to give a flavour of the possibilities of action research and includes some useful guides to practice. As ever, if you have suggestions about areas or specific texts for inclusion, I’d like to hear from you.

Explorations of action research

Atweh, B., Kemmis, S. and Weeks, P. (eds.) (1998) Action Research in Practice: Partnership for Social Justice in Education, London: Routledge. Presents a collection of stories from action research projects in schools and a university. The book begins with theme chapters discussing action research, social justice and partnerships in research. The case study chapters cover topics such as: school environment – how to make a school a healthier place to be; parents – how to involve them more in decision-making; students as action researchers; gender – how to promote gender equity in schools; writing up action research projects.

Carr, W. and Kemmis, S. (1986) Becoming Critical. Education, knowledge and action research , Lewes: Falmer. Influential book that provides a good account of ‘action research’ in education. Chapters on teachers, researchers and curriculum; the natural scientific view of educational theory and practice; the interpretative view of educational theory and practice; theory and practice – redefining the problem; a critical approach to theory and practice; towards a critical educational science; action research as critical education science; educational research, educational reform and the role of the profession.

Carson, T. R. and Sumara, D. J. (ed.) (1997) Action Research as a Living Practice , New York: Peter Lang. 140 pages. Book draws on a wide range of sources to develop an understanding of action research. Explores action research as a lived practice, ‘that asks the researcher to not only investigate the subject at hand but, as well, to provide some account of the way in which the investigation both shapes and is shaped by the investigator.

Dadds, M. (1995) Passionate Enquiry and School Development. A story about action research , London: Falmer. 192 + ix pages. Examines three action research studies undertaken by a teacher and how they related to work in school – how she did the research, the problems she experienced, her feelings, the impact on her feelings and ideas, and some of the outcomes. In his introduction, John Elliot comments that the book is ‘the most readable, thoughtful, and detailed study of the potential of action-research in professional education that I have read’.

Ghaye, T. and Wakefield, P. (eds.) CARN Critical Conversations. Book one: the role of the self in action , Bournemouth: Hyde Publications. 146 + xiii pages. Collection of five pieces from the Classroom Action Research Network. Chapters on: dialectical forms; graduate medical education – research’s outer limits; democratic education; managing action research; writing up.

McNiff, J. (1993) Teaching as Learning: An Action Research Approach , London: Routledge. Argues that educational knowledge is created by individual teachers as they attempt to express their own values in their professional lives. Sets out familiar action research model: identifying a problem, devising, implementing and evaluating a solution and modifying practice. Includes advice on how working in this way can aid the professional development of action researcher and practitioner.

Quigley, B. A. and Kuhne, G. W. (eds.) (1997) Creating Practical Knowledge Through Action Research, San Fransisco: Jossey Bass. Guide to action research that outlines the action research process, provides a project planner, and presents examples to show how action research can yield improvements in six different settings, including a hospital, a university and a literacy education program.

Plummer, G. and Edwards, G. (eds.) CARN Critical Conversations. Book two: dimensions of action research – people, practice and power , Bournemouth: Hyde Publications. 142 + xvii pages. Collection of five pieces from the Classroom Action Research Network. Chapters on: exchanging letters and collaborative research; diary writing; personal and professional learning – on teaching and self-knowledge; anti-racist approaches; psychodynamic group theory in action research.

Whyte, W. F. (ed.) (1991) Participatory Action Research , Newbury Park: Sage. 247 pages. Chapters explore the development of participatory action research and its relation with action science and examine its usages in various agricultural and industrial settings

Zuber-Skerritt, O. (ed.) (1996) New Directions in Action Research , London; Falmer Press. 266 + xii pages. A useful collection that explores principles and procedures for critical action research; problems and suggested solutions; and postmodernism and critical action research.

Action research guides

Coghlan, D. and Brannick, D. (2000) Doing Action Research in your own Organization, London: Sage. 128 pages. Popular introduction. Part one covers the basics of action research including the action research cycle, the role of the ‘insider’ action researcher and the complexities of undertaking action research within your own organisation. Part two looks at the implementation of the action research project (including managing internal politics and the ethics and politics of action research). New edition due late 2004.

Elliot, J. (1991) Action Research for Educational Change , Buckingham: Open University Press. 163 + x pages Collection of various articles written by Elliot in which he develops his own particular interpretation of action research as a form of teacher professional development. In some ways close to a form of ‘reflective practice’. Chapter 6, ‘A practical guide to action research’ – builds a staged model on Lewin’s work and on developments by writers such as Kemmis.

Johnson, A. P. (2007) A short guide to action research 3e. Allyn and Bacon. Popular step by step guide for master’s work.

Macintyre, C. (2002) The Art of the Action Research in the Classroom , London: David Fulton. 138 pages. Includes sections on action research, the role of literature, formulating a research question, gathering data, analysing data and writing a dissertation. Useful and readable guide for students.

McNiff, J., Whitehead, J., Lomax, P. (2003) You and Your Action Research Project , London: Routledge. Practical guidance on doing an action research project.Takes the practitioner-researcher through the various stages of a project. Each section of the book is supported by case studies

Stringer, E. T. (2007) Action Research: A handbook for practitioners 3e , Newbury Park, ca.: Sage. 304 pages. Sets community-based action research in context and develops a model. Chapters on information gathering, interpretation, resolving issues; legitimacy etc. See, also Stringer’s (2003) Action Research in Education , Prentice-Hall.

Winter, R. (1989) Learning From Experience. Principles and practice in action research , Lewes: Falmer Press. 200 + 10 pages. Introduces the idea of action research; the basic process; theoretical issues; and provides six principles for the conduct of action research. Includes examples of action research. Further chapters on from principles to practice; the learner’s experience; and research topics and personal interests.

Action research in informal education

Usher, R., Bryant, I. and Johnston, R. (1997) Adult Education and the Postmodern Challenge. Learning beyond the limits , London: Routledge. 248 + xvi pages. Has some interesting chapters that relate to action research: on reflective practice; changing paradigms and traditions of research; new approaches to research; writing and learning about research.

Other references

Bogdan, R. and Biklen, S. K. (1992) Qualitative Research For Education , Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Goetschius, G. and Tash, J. (1967) Working with the Unattached , London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

McTaggart, R. (1996) ‘Issues for participatory action researchers’ in O. Zuber-Skerritt (ed.) New Directions in Action Research , London: Falmer Press.

McNiff, J., Lomax, P. and Whitehead, J. (2003) You and Your Action Research Project 2e. London: Routledge.

Thomas, G. (2017). How to do your Research Project. A guide for students in education and applied social sciences . 3e. London: Sage.

Acknowledgements : spiral by Michèle C. | flickr ccbyncnd2 licence

How to cite this article : Smith, M. K. (1996; 2001, 2007, 2017) What is action research and how do we do it?’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [ https://infed.org/mobi/action-research/ . Retrieved: insert date] .

© Mark K. Smith 1996; 2001, 2007, 2017

Last Updated on December 7, 2020 by infed.org

- Reviews / Why join our community?

- For companies

- Frequently asked questions

Action Research

What is action research.

Action research is a methodology that emphasizes collaboration between researchers and participants to identify problems, develop solutions and implement changes. Designers plan, act, observe and reflect, and aim to drive positive change in a specific context. Action research prioritizes practical solutions and improvement of practice, unlike knowledge generation, which is the priority of traditional methods.

© New Mexico State University, Fair Use

Why is Action Research Important in UX Design?

Action research stands out as a unique approach in user experience design (UX design), among other types of research methodologies and fields. It has a hands-on, practical focus, so UX designers and researchers who engage in it devise and execute research that not only gathers data but also leads to actionable insights and solid real-world solutions.

The concept of action research dates back to the 1940s, with its roots in the work of social psychologist Kurt Lewin. Lewin emphasized the importance of action in understanding and improving human systems. The approach rapidly gained popularity across various fields, including education, healthcare, social work and community development.

Kurt Lewin, the Founder of social psychology.

© Wikimedia Commons, Fair Use

In UX design, the incorporation of action research appeared with the rise of human-centered design principles. As UX design started to focus more on users' needs and experiences, the participatory and problem-solving nature of action research became increasingly significant. Action research bridges the gap between theory and practice in UX design. It enables designers to move beyond hypothetical assumptions and base their design decisions on concrete, real-world data. This not only enhances the effectiveness of the design but also boosts its credibility and acceptance among users—vital bonuses for product designers and service designers.

At its core, action research is a systematic, participatory and collaborative approach to research . It emphasizes direct engagement with specific issues or problems and aims to bring about positive change within a particular context. Traditional research methodologies tend to focus solely on the generation of theoretical knowledge. Meanwhile, action research aims to solve real-world problems and generate knowledge simultaneously .

Action research helps designers and design teams gather first-hand insights so they can deeply understand their users' needs, preferences and behaviors. With it, they can devise solutions that genuinely address their users’ problems—and so design products or services that will resonate with their target audiences. As designers actively involve users in the research process, they can gather authentic insights and co-create solutions that are both effective and user-centric.

Moreover, the iterative nature of action research aligns perfectly with the UX design process. It allows designers to continuously learn from users' feedback, adapt their designs accordingly, and test their effectiveness in real-world contexts. This iterative loop of planning, acting, observing and reflecting ensures that the final design solution is user-centric. However, it also ensures that actual user behavior and feedback validates the solution that a design team produces, which helps to make action research studies particularly rewarding for some brands.

Designers can continuously learn from users’ feedback in action research and iterate accordingly.

© Fauxels, Fair Use

What is The Action Research Process?

Action research in UX design involves several stages. Each stage contributes to the ultimate goal: to create effective and user-centric design solutions. Here is a step-by-step breakdown of the process:

1. Identify the Problem

This could be a particular pain point users are facing, a gap in the current UX design, or an opportunity for improvement.

2. Plan the Action

Designers might need to devise new design features, modify existing ones or implement new user interaction strategies.

3. Implement the Action

Designers put their planned actions into practice. They might prototype the new design, implement the new features or test the new user interaction strategies.

4. Observe and Collect Data

As designers implement the action they’ve decided upon, it's crucial to observe its effects and collect data. This could mean that designers track user behaviors, collect user feedback, conduct usability tests or use other data collection methods.

5. Reflect on the Results

From the collected data, designers reflect on the results, analyze the effectiveness of the action and draw insights. If the action has led to positive outcomes, they can further refine it and integrate it into the final design. If not, they can go back to plan new actions and repeat the process.

An action research example could be where designers do the following:

Identification : Designers observe a high abandonment rate during a checkout process for an e-commerce website.

Planning : They analyze the checkout flow to identify potential friction points.

Action : They isolate these points, streamline the checkout process, introduce guest checkout and optimize form fields.

Observation : They monitor changes in abandonment rates and collect user feedback.

Reflection : They assess the effectiveness of the changes as these reduce checkout abandonment.

Outcome : The design team notices a significant decrease in checkout abandonment, which leads to higher conversion rates as more users successfully purchase goods.

What Types of Action Research are there?

Action research splits into three main types: technical, collaborative and critical reflection.

1. Technical Action Research

Technical action research focuses on improving the efficiency and effectiveness of a system or process. Designers often use it in organizational contexts to address specific issues or enhance operations. This could be where designers improve the usability of a website, optimize the load time of an application or enhance the accessibility of a digital product.

- Transcript loading…

2. Collaborative Action Research