How to write a case study — examples, templates, and tools

It’s a marketer’s job to communicate the effectiveness of a product or service to potential and current customers to convince them to buy and keep business moving. One of the best methods for doing this is to share success stories that are relatable to prospects and customers based on their pain points, experiences, and overall needs.

That’s where case studies come in. Case studies are an essential part of a content marketing plan. These in-depth stories of customer experiences are some of the most effective at demonstrating the value of a product or service. Yet many marketers don’t use them, whether because of their regimented formats or the process of customer involvement and approval.

A case study is a powerful tool for showcasing your hard work and the success your customer achieved. But writing a great case study can be difficult if you’ve never done it before or if it’s been a while. This guide will show you how to write an effective case study and provide real-world examples and templates that will keep readers engaged and support your business.

In this article, you’ll learn:

What is a case study?

How to write a case study, case study templates, case study examples, case study tools.

A case study is the detailed story of a customer’s experience with a product or service that demonstrates their success and often includes measurable outcomes. Case studies are used in a range of fields and for various reasons, from business to academic research. They’re especially impactful in marketing as brands work to convince and convert consumers with relatable, real-world stories of actual customer experiences.

The best case studies tell the story of a customer’s success, including the steps they took, the results they achieved, and the support they received from a brand along the way. To write a great case study, you need to:

- Celebrate the customer and make them — not a product or service — the star of the story.

- Craft the story with specific audiences or target segments in mind so that the story of one customer will be viewed as relatable and actionable for another customer.

- Write copy that is easy to read and engaging so that readers will gain the insights and messages intended.

- Follow a standardized format that includes all of the essentials a potential customer would find interesting and useful.

- Support all of the claims for success made in the story with data in the forms of hard numbers and customer statements.

Case studies are a type of review but more in depth, aiming to show — rather than just tell — the positive experiences that customers have with a brand. Notably, 89% of consumers read reviews before deciding to buy, and 79% view case study content as part of their purchasing process. When it comes to B2B sales, 52% of buyers rank case studies as an important part of their evaluation process.

Telling a brand story through the experience of a tried-and-true customer matters. The story is relatable to potential new customers as they imagine themselves in the shoes of the company or individual featured in the case study. Showcasing previous customers can help new ones see themselves engaging with your brand in the ways that are most meaningful to them.

Besides sharing the perspective of another customer, case studies stand out from other content marketing forms because they are based on evidence. Whether pulling from client testimonials or data-driven results, case studies tend to have more impact on new business because the story contains information that is both objective (data) and subjective (customer experience) — and the brand doesn’t sound too self-promotional.

Case studies are unique in that there’s a fairly standardized format for telling a customer’s story. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t room for creativity. It’s all about making sure that teams are clear on the goals for the case study — along with strategies for supporting content and channels — and understanding how the story fits within the framework of the company’s overall marketing goals.

Here are the basic steps to writing a good case study.

1. Identify your goal

Start by defining exactly who your case study will be designed to help. Case studies are about specific instances where a company works with a customer to achieve a goal. Identify which customers are likely to have these goals, as well as other needs the story should cover to appeal to them.

The answer is often found in one of the buyer personas that have been constructed as part of your larger marketing strategy. This can include anything from new leads generated by the marketing team to long-term customers that are being pressed for cross-sell opportunities. In all of these cases, demonstrating value through a relatable customer success story can be part of the solution to conversion.

2. Choose your client or subject

Who you highlight matters. Case studies tie brands together that might otherwise not cross paths. A writer will want to ensure that the highlighted customer aligns with their own company’s brand identity and offerings. Look for a customer with positive name recognition who has had great success with a product or service and is willing to be an advocate.

The client should also match up with the identified target audience. Whichever company or individual is selected should be a reflection of other potential customers who can see themselves in similar circumstances, having the same problems and possible solutions.

Some of the most compelling case studies feature customers who:

- Switch from one product or service to another while naming competitors that missed the mark.

- Experience measurable results that are relatable to others in a specific industry.

- Represent well-known brands and recognizable names that are likely to compel action.

- Advocate for a product or service as a champion and are well-versed in its advantages.

Whoever or whatever customer is selected, marketers must ensure they have the permission of the company involved before getting started. Some brands have strict review and approval procedures for any official marketing or promotional materials that include their name. Acquiring those approvals in advance will prevent any miscommunication or wasted effort if there is an issue with their legal or compliance teams.

3. Conduct research and compile data

Substantiating the claims made in a case study — either by the marketing team or customers themselves — adds validity to the story. To do this, include data and feedback from the client that defines what success looks like. This can be anything from demonstrating return on investment (ROI) to a specific metric the customer was striving to improve. Case studies should prove how an outcome was achieved and show tangible results that indicate to the customer that your solution is the right one.

This step could also include customer interviews. Make sure that the people being interviewed are key stakeholders in the purchase decision or deployment and use of the product or service that is being highlighted. Content writers should work off a set list of questions prepared in advance. It can be helpful to share these with the interviewees beforehand so they have time to consider and craft their responses. One of the best interview tactics to keep in mind is to ask questions where yes and no are not natural answers. This way, your subject will provide more open-ended responses that produce more meaningful content.

4. Choose the right format

There are a number of different ways to format a case study. Depending on what you hope to achieve, one style will be better than another. However, there are some common elements to include, such as:

- An engaging headline

- A subject and customer introduction

- The unique challenge or challenges the customer faced

- The solution the customer used to solve the problem

- The results achieved

- Data and statistics to back up claims of success

- A strong call to action (CTA) to engage with the vendor

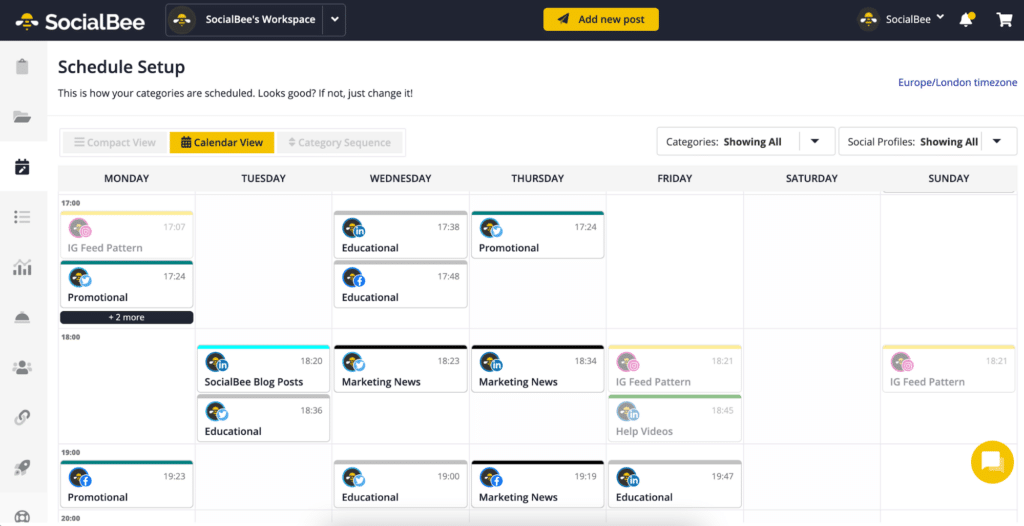

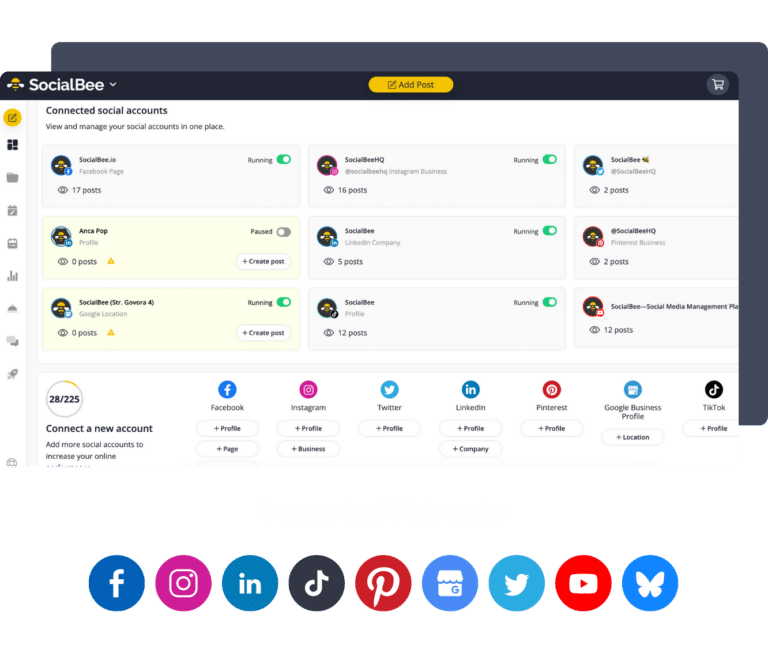

It’s also important to note that while case studies are traditionally written as stories, they don’t have to be in a written format. Some companies choose to get more creative with their case studies and produce multimedia content, depending on their audience and objectives. Case study formats can include traditional print stories, interactive web or social content, data-heavy infographics, professionally shot videos, podcasts, and more.

5. Write your case study

We’ll go into more detail later about how exactly to write a case study, including templates and examples. Generally speaking, though, there are a few things to keep in mind when writing your case study.

- Be clear and concise. Readers want to get to the point of the story quickly and easily, and they’ll be looking to see themselves reflected in the story right from the start.

- Provide a big picture. Always make sure to explain who the client is, their goals, and how they achieved success in a short introduction to engage the reader.

- Construct a clear narrative. Stick to the story from the perspective of the customer and what they needed to solve instead of just listing product features or benefits.

- Leverage graphics. Incorporating infographics, charts, and sidebars can be a more engaging and eye-catching way to share key statistics and data in readable ways.

- Offer the right amount of detail. Most case studies are one or two pages with clear sections that a reader can skim to find the information most important to them.

- Include data to support claims. Show real results — both facts and figures and customer quotes — to demonstrate credibility and prove the solution works.

6. Promote your story

Marketers have a number of options for distribution of a freshly minted case study. Many brands choose to publish case studies on their website and post them on social media. This can help support SEO and organic content strategies while also boosting company credibility and trust as visitors see that other businesses have used the product or service.

Marketers are always looking for quality content they can use for lead generation. Consider offering a case study as gated content behind a form on a landing page or as an offer in an email message. One great way to do this is to summarize the content and tease the full story available for download after the user takes an action.

Sales teams can also leverage case studies, so be sure they are aware that the assets exist once they’re published. Especially when it comes to larger B2B sales, companies often ask for examples of similar customer challenges that have been solved.

Now that you’ve learned a bit about case studies and what they should include, you may be wondering how to start creating great customer story content. Here are a couple of templates you can use to structure your case study.

Template 1 — Challenge-solution-result format

- Start with an engaging title. This should be fewer than 70 characters long for SEO best practices. One of the best ways to approach the title is to include the customer’s name and a hint at the challenge they overcame in the end.

- Create an introduction. Lead with an explanation as to who the customer is, the need they had, and the opportunity they found with a specific product or solution. Writers can also suggest the success the customer experienced with the solution they chose.

- Present the challenge. This should be several paragraphs long and explain the problem the customer faced and the issues they were trying to solve. Details should tie into the company’s products and services naturally. This section needs to be the most relatable to the reader so they can picture themselves in a similar situation.

- Share the solution. Explain which product or service offered was the ideal fit for the customer and why. Feel free to delve into their experience setting up, purchasing, and onboarding the solution.

- Explain the results. Demonstrate the impact of the solution they chose by backing up their positive experience with data. Fill in with customer quotes and tangible, measurable results that show the effect of their choice.

- Ask for action. Include a CTA at the end of the case study that invites readers to reach out for more information, try a demo, or learn more — to nurture them further in the marketing pipeline. What you ask of the reader should tie directly into the goals that were established for the case study in the first place.

Template 2 — Data-driven format

- Start with an engaging title. Be sure to include a statistic or data point in the first 70 characters. Again, it’s best to include the customer’s name as part of the title.

- Create an overview. Share the customer’s background and a short version of the challenge they faced. Present the reason a particular product or service was chosen, and feel free to include quotes from the customer about their selection process.

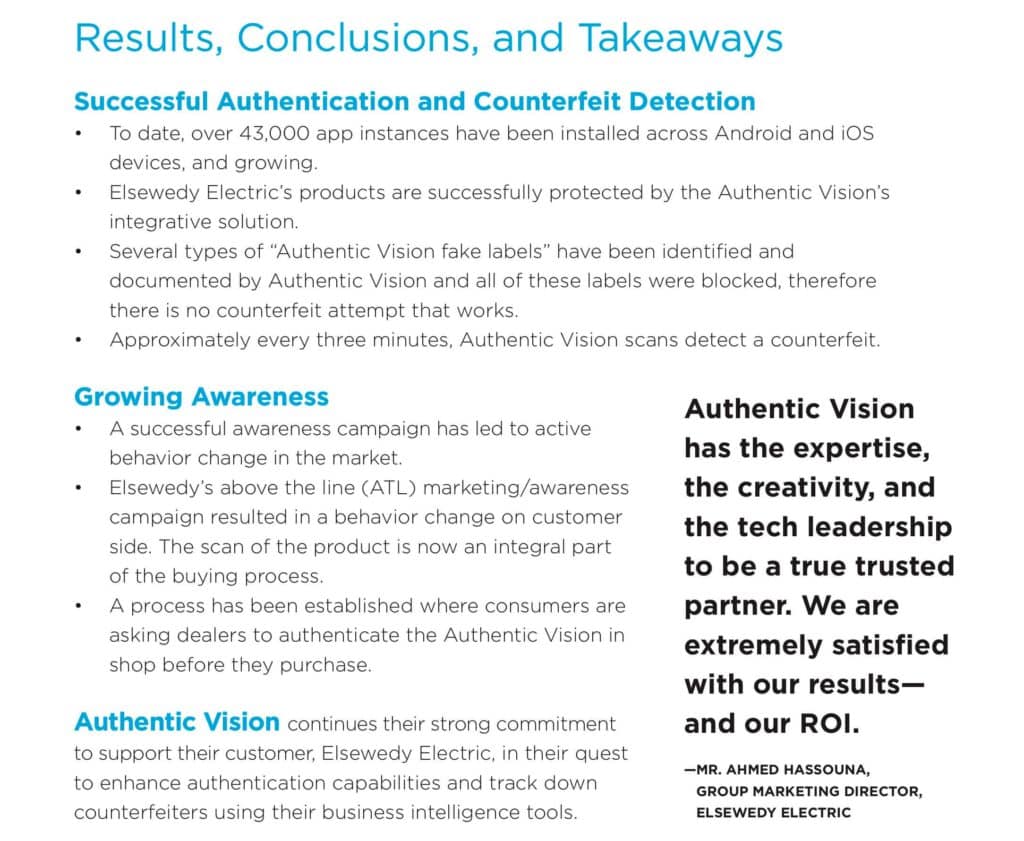

- Present data point 1. Isolate the first metric that the customer used to define success and explain how the product or solution helped to achieve this goal. Provide data points and quotes to substantiate the claim that success was achieved.

- Present data point 2. Isolate the second metric that the customer used to define success and explain what the product or solution did to achieve this goal. Provide data points and quotes to substantiate the claim that success was achieved.

- Present data point 3. Isolate the final metric that the customer used to define success and explain what the product or solution did to achieve this goal. Provide data points and quotes to substantiate the claim that success was achieved.

- Summarize the results. Reiterate the fact that the customer was able to achieve success thanks to a specific product or service. Include quotes and statements that reflect customer satisfaction and suggest they plan to continue using the solution.

- Ask for action. Include a CTA at the end of the case study that asks readers to reach out for more information, try a demo, or learn more — to further nurture them in the marketing pipeline. Again, remember that this is where marketers can look to convert their content into action with the customer.

While templates are helpful, seeing a case study in action can also be a great way to learn. Here are some examples of how Adobe customers have experienced success.

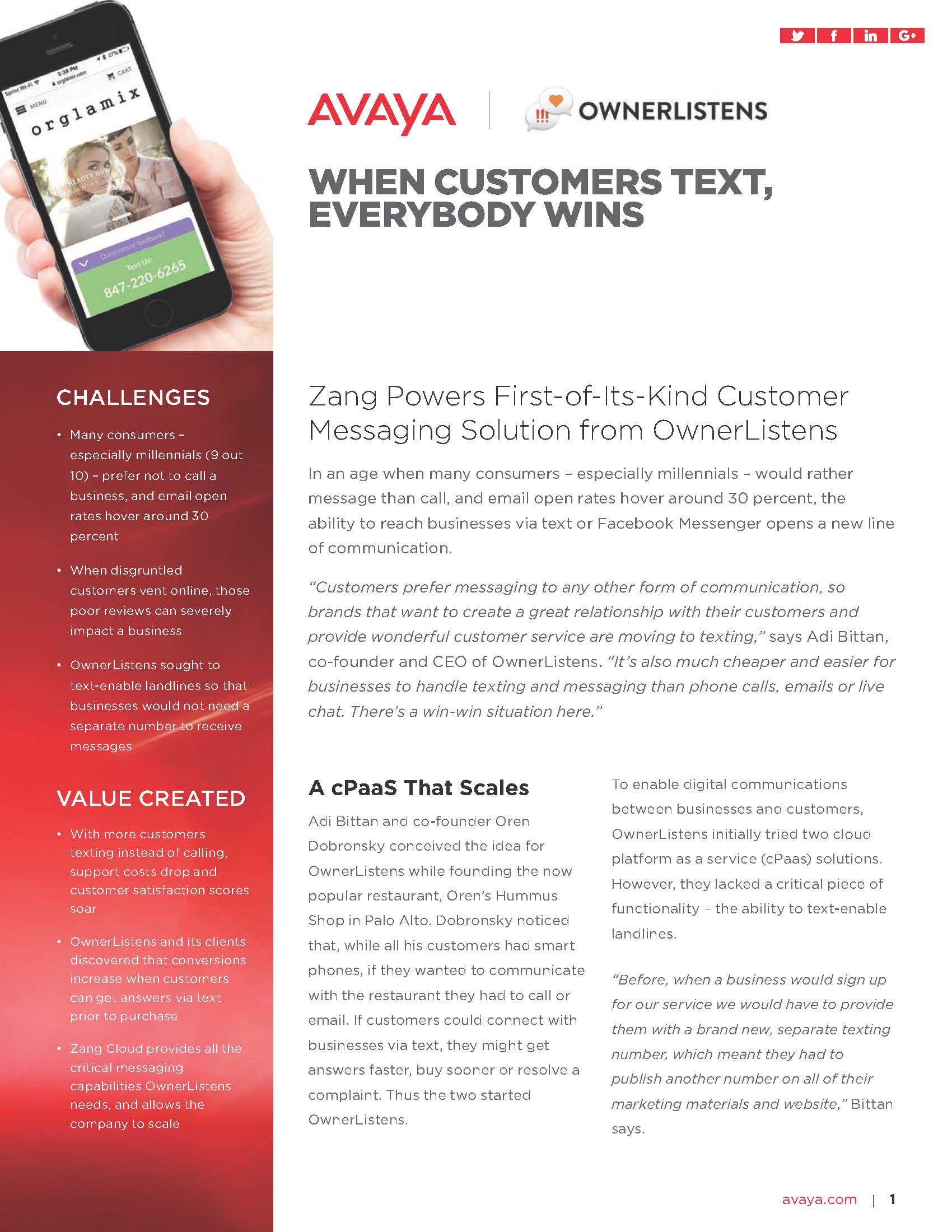

Juniper Networks

One example is the Adobe and Juniper Networks case study , which puts the reader in the customer’s shoes. The beginning of the story quickly orients the reader so that they know exactly who the article is about and what they were trying to achieve. Solutions are outlined in a way that shows Adobe Experience Manager is the best choice and a natural fit for the customer. Along the way, quotes from the client are incorporated to help add validity to the statements. The results in the case study are conveyed with clear evidence of scale and volume using tangible data.

The story of Lenovo’s journey with Adobe is one that spans years of planning, implementation, and rollout. The Lenovo case study does a great job of consolidating all of this into a relatable journey that other enterprise organizations can see themselves taking, despite the project size. This case study also features descriptive headers and compelling visual elements that engage the reader and strengthen the content.

Tata Consulting

When it comes to using data to show customer results, this case study does an excellent job of conveying details and numbers in an easy-to-digest manner. Bullet points at the start break up the content while also helping the reader understand exactly what the case study will be about. Tata Consulting used Adobe to deliver elevated, engaging content experiences for a large telecommunications client of its own — an objective that’s relatable for a lot of companies.

Case studies are a vital tool for any marketing team as they enable you to demonstrate the value of your company’s products and services to others. They help marketers do their job and add credibility to a brand trying to promote its solutions by using the experiences and stories of real customers.

When you’re ready to get started with a case study:

- Think about a few goals you’d like to accomplish with your content.

- Make a list of successful clients that would be strong candidates for a case study.

- Reach out to the client to get their approval and conduct an interview.

- Gather the data to present an engaging and effective customer story.

Adobe can help

There are several Adobe products that can help you craft compelling case studies. Adobe Experience Platform helps you collect data and deliver great customer experiences across every channel. Once you’ve created your case studies, Experience Platform will help you deliver the right information to the right customer at the right time for maximum impact.

To learn more, watch the Adobe Experience Platform story .

Keep in mind that the best case studies are backed by data. That’s where Adobe Real-Time Customer Data Platform and Adobe Analytics come into play. With Real-Time CDP, you can gather the data you need to build a great case study and target specific customers to deliver the content to the right audience at the perfect moment.

Watch the Real-Time CDP overview video to learn more.

Finally, Adobe Analytics turns real-time data into real-time insights. It helps your business collect and synthesize data from multiple platforms to make more informed decisions and create the best case study possible.

Request a demo to learn more about Adobe Analytics.

https://business.adobe.com/blog/perspectives/b2b-ecommerce-10-case-studies-inspire-you

https://business.adobe.com/blog/basics/business-case

https://business.adobe.com/blog/basics/what-is-real-time-analytics

- Fun Writing Niches That Pay Well What can you get paid to write about? The answer is easy: Almost anything! And you could even start landing paid writing gigs this month. Learn how here!

- LAST CHANCE: Become a Barefoot Writer and Save 77% Today! Freedom, fun, and financial security await you when you make up your mind to go after the writer’s life. Here’s the resource that helps make it possible.

- We’ve Chosen You For This Now and again we invite a small handful of our most active and “eager-to-succeed” members to be personally mentored and guided through all aspects of their copywriting career… From choosing the ideal writing niche… To laying out a step-by-step plan for your success... To landing top clients... getting paid... expanding your business and expertise… and much, much more.

- Read More News …

How to Write a Case Study with Examples By John Wood for AWAI

The 9-step formula detailed below will teach you how to write a winning business case study. And we’ll walk through the process using real case study examples. You'll find all the information you need to write a polished case study that will generate leads and help close sales.

- Email a Friend

When you can write an effective case study, you’re creating a powerful sales tool for your business or client. That’s because a case study is a compelling, real-world, “before and after” story that shows how a customer solved a problem by using a company’s product or service.

The customer (not the company’s sales team) is the credible source telling a story that’s relevant and valuable to the prospect.

Businesses love case studies, because they’re a huge step beyond a simple testimonial. They help give a prospect an understanding of how a customer accomplished their goals by using their product.

In a competitive marketplace, case studies are an effective way for businesses to differentiate themselves from their competitors.

If you’re in business, starting a business, or writing for a business … knowing how to write a case study is a valuable skill that will help you generate a pipeline of leads and close sales. And if you’re a marketer, it’s another profitable skill to have in your marketing arsenal.

Let’s look at the specific steps for writing an effective case study, along with a few other tips that will help make your case study a success.

How to write a case study in 9 easy steps

Writing a case study is quite simple, as long as you know the proven formula business writers generally follow. The nine main components of writing a case study are …

A news-like headline — The most effective case study headlines focus on one idea that communicates relevant benefits to your target audience in a compelling way. You don’t need to be clever or adopt a sales tone with your headline. Your goal is to be objective and straightforward. For your headline to have the most impact, you should include tangible figures.

Here are a couple of examples:

The Wilson Group Increases Throughput by 312% Using Mason Douglas

Noble Corporation Helps ABC Medical Increase Production Output by 37% in Six Months

The above examples are focused on one idea only and state the main benefit or result received. You could also tack on how the result was achieved using a “cause and effect” headline format, like this:

The Wilson Group Increases Throughput by 312% by Streamlining Their Assembly Line with Mason Douglas

The cause is the streamlining of the assembly line; the effect is the 312% increase in throughput.

Headline Tips:

- Focus on one big idea.

- State it almost like a newspaper headline and make sure it will appeal to the prospect and what they’re trying to solve or achieve.

Customer background — In this section, you’ll describe the business customer in three to six sentences. This should total 50 to 100 words. Here is some of the customer-related information you may want to include:

- Where the customer’s business is headquartered

- What the company manufactures or sells or delivers

- What types of customers they target

- How long they’ve been around or when they were founded

- The number of employees

- Their number of locations

- Their main product lines or service offerings

- What makes the company and their products or services different

It may be difficult to include all seven of these points within the targeted word count. Your mission is to pick the most relevant information based on your target audience and the story you’re telling in your case study.

Two places to look for information about the customer’s company are in the “About Us” section of a recent press release and the “About Us” page of their website. You can also fill in any information missing from your research during the interview with the customer.

The challenges — Here you want to introduce and expand on the main challenges the customer was facing as related to the product or service featured in your case study.

The key here is to create a compelling story. Don’t just list the challenges; go a little deeper into the impact the challenges were having on their overall business.

Explain why it was important to solve them, why and how they were impacting the customer, and to what degree. Do this with two or three key challenges, as long as they tell a specific story related to the solution.

Your goal is to make your reader feel these challenges are too important and too meaningful to be ignored, and that a solution must be found to overcome them. Remember, the prospect is likely facing the same challenges as the customer in your case study, so the more descriptive you are, the better.

- The journey — In this section, document the journey to the solution and the results. You’ll talk about the research the customer did in search of a solution. You’ll outline the pros and cons of the options they considered and why they ultimately chose to go with the featured company’s product or service. This section adds depth and credibility to your story, as a prospect considering the same solution usually goes through a similar process.

- The solution — This is where you showcase the product or service as the answer to the customer’s challenges. Your goal here is to introduce the product or service in an educational, non-salesy way.

The implementation — Next, explain how the product or service was implemented. The key to this section is to paint an accurate picture.

It’s rare for an implementation to go 100% perfectly. So, to boost the authenticity of this section, document how the implementation went — warts and all — and then how the company overcame it. This will make your story more believable and compelling.

The results — This is where you detail how well the product or service solved the customer’s challenges. Focus on results metrics (tables, charts, increases in production, efficiency, revenue, etc.) that are both specific and relevant to the target audience. Tell them what was achieved and how.

Explain why the results are important to the customer and the impact they’ve had, both specific to the department the results were achieved in and the impact on the overall business.

Tip : BE SPECIFIC! Include facts, numbers, and charts. Use tangible and detailed figures. For instance, “increased sales by 17.5%” is much better than just “increased sales.”

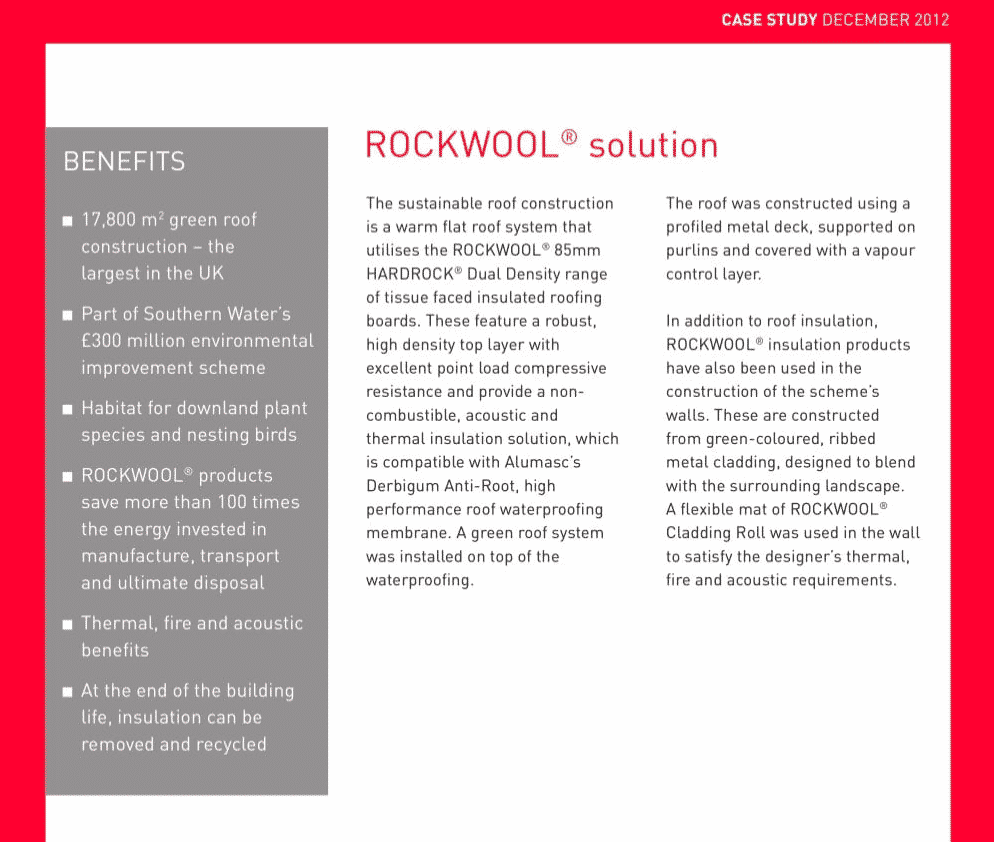

- Sidebar with summary points — To help busy executives who want to get the gist of the story without reading the entire case study, include a sidebar with a summary of the story and its main points. Write these so compellingly they instantly grab your reader’s attention.

- Pull-out quotes — You’ll want to pick one or two strong, relatively short customer quotes about solving the problem to use as a pull-out or featured quote. These quotes will add visual interest to your case study and will grab the attention of people who are simply scanning the content.

If you’ve been wondering how to write a case study, you can’t go wrong with the above formula. It’s been proven to work and is an extremely safe bet.

Case study examples

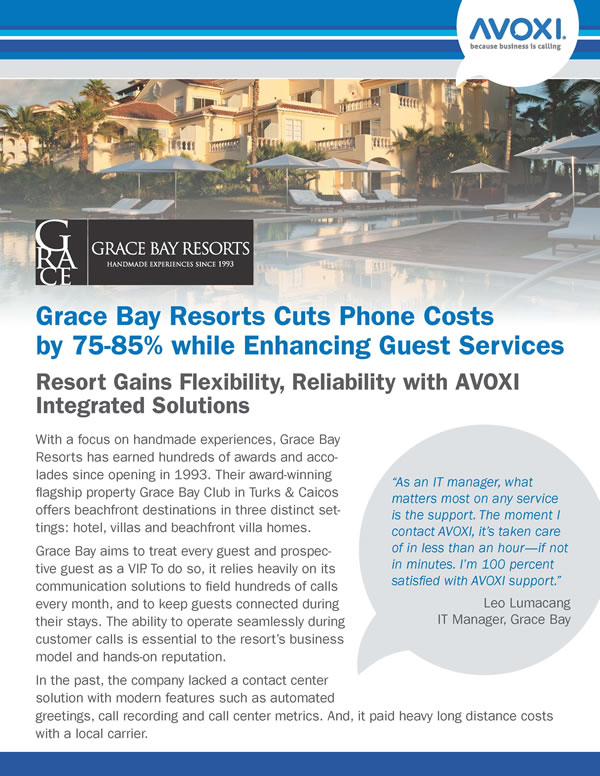

Case study example #1 — avoxi integrated solutions.

The first case study example is a business-to-business (B2B) case study showcasing AVOXI Integrated Solutions and their client, Grace Bay Resorts

A News-like headline (#1)

Grace Bay Resorts Cuts Phone Costs by 75-85% while Enhancing Guest Services.

This headline tells the reader what potential benefits they’ll experience, a reduction in costs and an improved guest experience. The writer increases the headline’s impact by making it very specific (75-85% cost reduction).

The subhead, Resort Gains Flexibility, Reliability with AVOXI Integrated Solutions , adds two more benefits and then names the solution.

The Customer Background (#2)

The first paragraph (44 words) gives a quick overview of the company:

With a focus on handmade experiences, Grace Bay Resorts has earned hundreds of awards and accolades since opening in 1993. Their award-winning flagship property Grace Bay Club in Turks & Caicos offers beachfront destinations in three distinct settings: hotel, villas and beachfront villa homes.

It answers three more questions potential buyers have: When they opened, where they are located, and what they offer.

The Challenges (#3)

In the second paragraph, the writer transitions into challenges Grace Bay faced. He starts by stressing how vital effective communication services are to Grace Bay’s results. The challenge is finding a provider who offers the latest technology at an affordable cost:

Grace Bay aims to treat every guest and prospective guest as a VIP. To do so, it relies heavily on its communication solutions to field hundreds of calls every month, and to keep guests connected during their stays. The ability to operate seamlessly during customer calls is essential to the resort’s business model and hands-on reputation.

In the past, the company lacked a contact center solution with modern features such as automated greetings, call recording and call center metrics. And, it paid heavy long-distance costs with a local carrier.

The Journey (#4)

In this case study, the copy describing the journey is short and concise. The IT Manager was sold on the AVOXI solution instantly when he heard about it:

When Leo Lumacang heard about AVOXI cloud solutions, the business case was clear. “When I presented to management that we would save thousands and thousands of dollars by switching to AVOXI, it was an easy sell,” says Lumacang, IT Manager at Grace Bay. “We cut out costs by probably 75-85 percent immediately.”

The Solution (#5)

The majority of the 2 nd page of the case study focuses on the solution including this excerpt that lists the AVOXI solutions that were implemented.

Grace Bay deployed a set of integrated cloud solutions from AVOXI, including a cloud-based phone system, virtual contact center software, a VoIP gateway and international toll-free numbers—all solutions that enhance the guest experience, and reduce costs and management hassles for the resort.

They go on to describe the features of the virtual contact center software and how it was used by the reservation center to improve their service levels.

The Implementation (#6)

The implementation phase of the product or service is a section that is not always documented in case studies. The reason for this is simple. There is nothing notable that came out of the implementation. In this case study, the writer focuses more on what was implemented (the solution) than on how it was implemented.

The Results (#7)

The results are detailed in the last three sections. The AVOXI solution resulted in significant improvements in Grace Bay’s reservation center operations. It also helped improve the guest experience by allowing the resort to provide free international toll-free calls. And finally, they highlight the reliability of the system and the efficiency and effectiveness of AVOXI’s customer support.

A Sidebar with summary points (#8)

In the left column on the second page, the writer adds a brief summary of the case study, listing the four components that make up the solution and three bullet points of the results experienced.

Pull-out quote (#9)

Pull-out quotes are used on pages 1 and 3 and focus on the improvements in service levels, one of the biggest concerns for the customer.

Case Study Example #2 — AWAI

The second case study example is a business-to-consumer (B2C) case study showcasing American Writers & Artists (AWAI) and one of their customers, Candice Lazar.

Florida Attorney Finds Fulfillment — and Financial Gain — in Copywriting Career Shift.

The headline is straightforward and reads very much like a news headline. The message of a successful career change to copywriting is aimed at prospects who may have similar goals.

The Customer background (#2)

The first few paragraphs give information about the Candice’s background by talking about her experiences and attitude towards risk-taking.

Her main challenge is revealed under the sub-head “A Simple, Self-Starting Business.” She “felt something was missing” in her job as an attorney. According to a recent Gallup study, 51 percent of Americans aren’t engaged in their work and another 16 percent are “actively disengaged,” so it’s an issue many people relate to.

Her journey starts when a former boss tells her he needs copywriting help. She spots a banner from AWAI which gets her thinking that writing might be a good career for her as it’s something she’s always enjoyed.

Candice’s goal is to learn as much about copywriting as she can. The solution is a variety of AWAI products.

Candice first joins the Barefoot Writer Club, she consumes The Accelerated Program for Six-Figure Copywriting. She also takes How to Make Money as a Social Media Marketing Expert and takes part in Joshua Boswell’s How to Launch Your Writer’s Life in a Day .

Under the subhead “Candice’s Niche Switch” it talks about how Candice originally chose small hotels and hotel chains as her copywriting focus. She soon realized that they don’t require a lot of marketing material. Acknowledging a setback or addressing a challenge is important because it adds to the credibility of Candace’s story.

The third page of the case study talks about Candice’s copywriting successes including the growth of her business which has allowed her to cut back to part time hours on her less fulfilling legal work.

There is a sidebar that gives basic information about Candice and the AWAI products that helped her launch her writing career.

Pull-out quotes (#9)

The first page contains a pull-out quote from Candice that focuses on her results … a copywriting business that is more than just a source of income. It's enjoyable and rewarding work.

The “feature article” case study format

The main difference between the traditional case study format and the feature article format is how the case study starts. The traditional format starts out with some basic information about the customer. The feature article format starts out with an interesting, engaging lead that usually talks about the challenge the customer was facing.

Then it goes to the information about the customer, followed by more information about the customer’s challenge.

After that, it follows the same format as outlined above for a traditional case study.

The other difference is that a feature article uses more descriptive subheads to draw the reader in, versus the traditional format’s somewhat straightforward subheads (Customer Background, The Challenges, etc.).

The feature article format works well when you want to make the story engaging right from the start. Plus, it tends to be better suited for people who want to understand the gist of the case study quickly by merely skimming the pages.

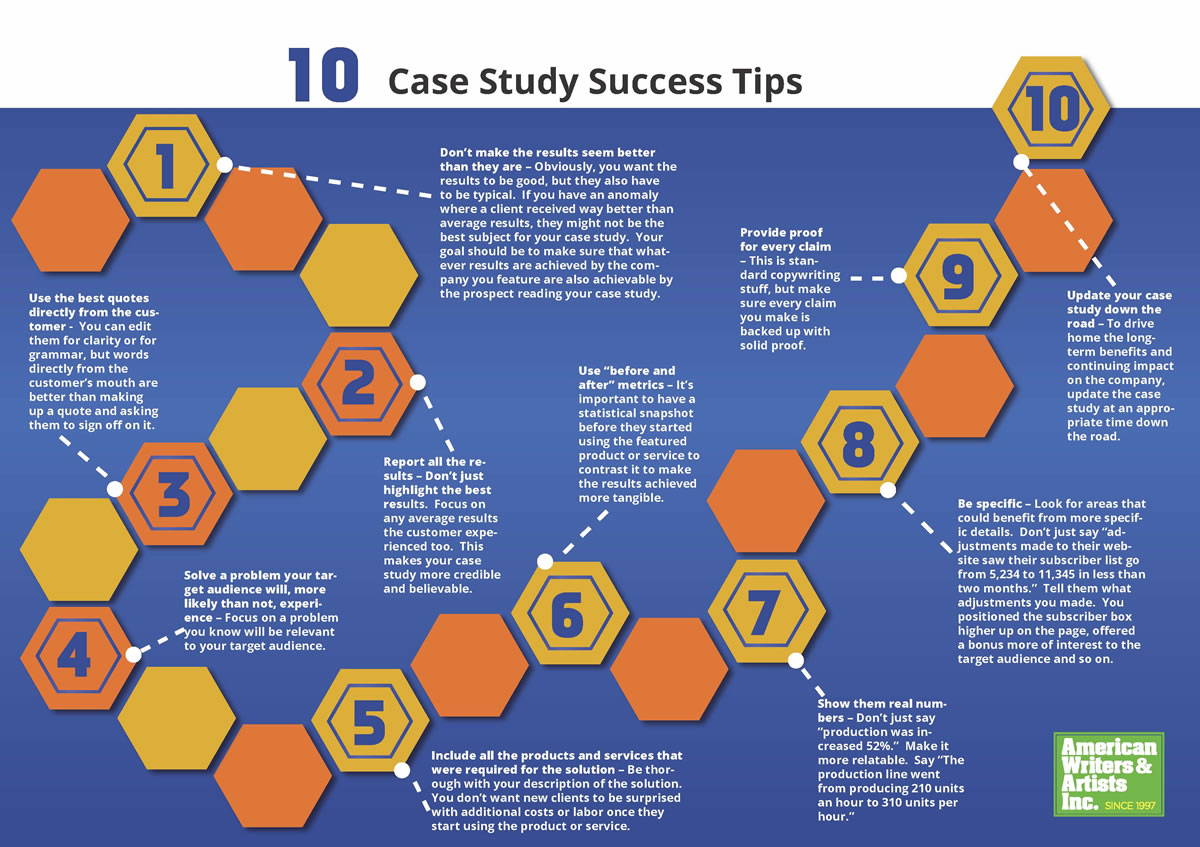

Case study success tips

Use this as a handy checklist when writing your next case study.

- Don’t make the results seem better than they are. Obviously, you want the results to be good, but they also have to be typical. If you have an anomaly, where a customer received much better than average results, they might not be the best subject for your case study. Your goal should be to make sure whatever results are achieved by the customer you feature are also achievable by the prospect reading your case study.

- Report all the results. Don’t just highlight the best results. Focus on any average results the customer experienced, too. This makes your case study more credible and believable.

- Use the best quotes directly from the customer. You can edit them for clarity or for grammar, but words directly from the customer’s mouth are better than making up a quote and asking them to sign off on it.

- Solve a problem your target audience will, more likely than not, experience. Focus on a problem you know will be relevant to your target audience.

- Include all the products and services that were required for the solution. Be thorough with your description of the solution. You don’t want new customers to be surprised with additional costs or labor fees, once they start using the product or service.

- Use “before and after” metrics. It’s important to have a statistical snapshot of the customer’s situation before they started using the featured product or service, and then contrast it to the results achieved after using it. This will make the results more tangible.

- Show them real numbers. Don’t just say, “Production was increased 48%.” Make it more relatable. Say, “The production line went from producing 210 units an hour to 310 units per hour.”

- Be specific. Look for areas that could benefit from more specific details. Don’t just say, “Adjustments made to their website saw their subscriber list go from 5,234 to 11,345 in less than two months.” Tell them what adjustments you made. You positioned the subscriber box higher up on the page, offered a bonus more of interest to the target audience, and so on.

- Provide proof for every claim. This is standard copywriting stuff, but make sure every claim you make is backed up with solid proof.

- Update your case study down the road. To drive home the long-term benefits and continuing impact on the featured customer, update the case study at an appropriate time down the road.

- Use the “Power of One.” One of the most powerful copywriting principles is the “Power of One,” which is to focus on one story in the case study — one challenge, one solution, one “big wow” impact on how it made a difference.

Ed Gandia , author of Writing Case Studies , says it’s important to keep the “Power of One” top of mind when writing your case study …

Ed Gandia “The plot of a good success story often has multiple themes or ideas. When writing a case study, it’s very tempting to highlight all of them in order to dramatize the story. Doing so, however, can confuse the reader and rob the story of its one key theme. So, stick to one theme — one big idea. Your draft will be much stronger as a result.”

Read Mark Ford’s article, “The Power of One — One Big Idea” for more information about this important copywriting principle.

BONUS: How to promote your case study

A great case study can be the foundation for additional content-marketing opportunities. Try the following clever ways to promote your case study and generate loads of leads for your business:

- Newsletter — Write a story that covers the key details of the case study and include it in your newsletter with a link to access it.

- Webinar — Present a webinar that focuses only on the case study or features it as proof of the claims made about a product or service.

- White paper — Present a case study in a sidebar of a white paper or feature it as part of the narrative within the body copy.

- Sales presentation — Feature a case study in a sales presentation to add credibility to the benefits promised.

- Article or blog post — The problem/solution story that’s at the heart of your case study makes an interesting and informative article topic or blog post.

- Event handout — A case study is an ideal handout at an industry event or a speaking engagement.

- Email signature — Add a sentence or two to your email signature, such as, “Click here to see how company ABC improved their profits by X% in less than six months.”

- Press release — Announce to the world that one of your customers or clients has solved a problem or is operating more efficiently, thanks to one of your products or services.

- LinkedIn — Promote your case study on LinkedIn by posting an article and linking it to a blog post or article. Plus, join groups made up of your target audience and subtly promote your case study within the group.

- Video — Some prospects prefer watching a video over reading two to four pages of copy. If it’s in the budget, create a video based on your case study.

- Social media — Tweet about it, post pictures related to it on Pinterest, or post a video/webinar on YouTube.

- Dedicated case study page — Provide a summary of the case study (Customer’s Company Name, Headline, Problem, Solution, Results) and a link for readers to download the complete case study as a PDF.

- Your homepage — If the case study is hot off the press, a great way to attract attention to it is to mention it on your homepage.

- Product or service sales page — A real-life customer experience just might be the push a prospect needs to become a customer.

- SlideShare presentation — Turn your case study into a detailed presentation, post it on LinkedIn’s SlideShare website, and take advantage of their 60-million-strong audience.

Tip: Several of the above marketing options also give a business an opportunity to capture a prospect’s email address in exchange for giving them access to the case study.

Want to dive deeper into learning how to write case studies?

If you enjoy writing stories, prefer shorter projects over longer assignments, and love the challenge of taking a straightforward story and finding the “hook” or “angle” that will make it more compelling to bring in business leads and sales … writing case studies might be of interest to you.

Ed’s program, Writing Case Studies , may be the fastest, easiest way to get started writing case studies that will “wow” your clients. Here’s what you’ll discover…

- An overview of case studies — What they are, what they’re used for, who reads them, and why they’re effective.

- How to write an effective case study — What elements to include and what purpose each element serves. You’ll know the exact formula to follow to write an effective and compelling case study.

- The planning of your case study — From the initial discovery call to obtaining a personal commitment from the customer (the interviewee), you’ll know the necessary steps to take to ensure your case study project goes smoothly.

- How to conduct a tightly focused interview — If done right, you should be able to get all the information you need in about 30 minutes. Ed details how to get the information you need to write the most powerful story possible.

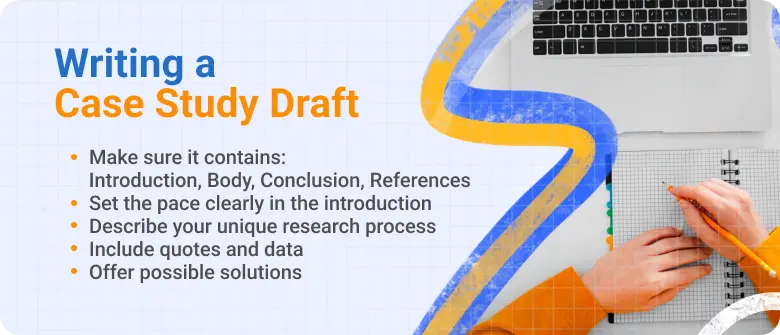

- How to write your case study draft — The actual step-by-step process you should use to get your draft down in a document and what you can do to make the flow of copy as effective and persuasive as possible.

- Everything you need to know about how to market yourself as a case study writer — What questions to ask before you provide a quote … how to price your projects profitably … and how to increase your chances of landing the work.

- And, much more …

To find out more information about how to become an expert case study writer, click here.

Share this Page:

Facebook Twitter Pinterest LinkedIn Email

13 Responses to “How to Write a Case Study with Examples - AWAI’s 9-Step Process”

This is just So Great... I love AWAI. Thank you. But If I submmit a Written Case study today, how long will it take me to get a feedback from AWAI? Thank You.

Guest (Abraham) – over a year ago

This was great! All the information was well presented. I'm sure to use this in the field.

Corance – over a year ago

I want to practice, so I will do one on Barefoot, and others. Can I turn these in for comments?

Musick – over a year ago

Excellent article and how to, what to include and what to expect on writing Case Studies. This is one of my niches and I have several companies in the town I live in that I can approach on the successful implementation of their products to solve problems. Thanks.

Guest (Scott T) – over a year ago

Very well written post. It will be useful to anybody who uses it, as well as myself. Keep doing what you are doing – looking forward to more posts.

Guest (Kunal Vaghasiya) – over a year ago

Thanks a lot! I have read out a number of website but could not get complete information only and only this website is complete how to write a proper blog post.

Guest (Willie Rodger) – over a year ago

I want to learn how to do case studies.

Ola – over a year ago

I greatly appreciated this article on Case Studies. I had to write my first one today. I wasn’t going to tell the client I hadn’t written one before, because I knew exactly where I could go to find out everything I would need to know (AWAI archives and resources!). After reading it I felt confident in producing the project. Thank you for the thorough explanation and examples, as well as the “extras” that will definitely put my piece a cut above in the client’s eyes. So grateful for AWAI. Thank you for your wealth of information and education. It’s all useful and relevant!

Kelli B – over a year ago

The Case Study I have found to develop sharp decision making skills - My former roles as a BRAND MANAGER - WITH UNILEVER all the team members - were MBA's from the best Universities of the U.S. our curiculas of Case Studies - was the building block and Common Denominator to build profitable brands from every division.

AAALLWOOD - 32216 – over a year ago

Great post! I feel like I have a solid foundation to at least get started with writing case studies now. Thank you!

Guest (Jason K) – over a year ago

Awesome post, great information, hoping to do case studies on legal documents. Great start to my career as a copywriter. Can't wait to get started. Thank you!

Writing for A Purpose – over a year ago

John Wood's article is very informative and Ed Gandia's video provided a great example that he deftly broke down for a beginner. I got what I was looking for out of them both!

AWAI always provides the answers to my questions and shows me the way to build my writing skills! Thanks!

the writers block – over a year ago

Not only did the article whet my appetite for writing case studies, it was packed with information to help me understand how case studies are written. So that my now diamond in the rough knowledge of case studies is further polished and shiny, I'll take the course. Thanks for the very informative article!

Guest (Erika) – over a year ago

Guest, Add a Comment Please Note: Your comments will be seen by all visitors.

You are commenting as a guest. If you’re an AWAI Member, Login to myAWAI for easier commenting, email alerts, and more!

(If you don’t yet have an AWAI Member account, you can create one for free .)

Display Name * : This name will appear next to your comment.

Email Address * : Your email is required but will not be displayed.

Comment * : Text only. Your comment may be trimmed if it exceeds 500 characters.

Type the word above * : Hint: The letters above appear as shadows and spell a real word. If you have trouble reading it, you can use the links to view a new image or listen to the letters being spoken.

Submit Comment ( * all fields required)

How to Write a Case Study: The Compelling Step-by-Step Guide

Is there a poignant pain point that needs to be addressed in your company or industry? Do you have a possible solution but want to test your theory? Why not turn this drive into a transformative learning experience and an opportunity to produce a high-quality business case study? However, before that occurs, you may wonder how to write a case study.

You may also be thinking about why you should produce one at all. Did you know that case studies are impactful and the fifth most used type of content in marketing , despite being more resource-intensive to produce?

Below, we’ll delve into what a case study is, its benefits, and how to approach business case study writing:

Definition of a Written case study and its Purpose

A case study is a research method that involves a detailed and comprehensive examination of a specific real-life situation. It’s often used in various fields, including business, education, economics, and sociology, to understand a complex issue better.

It typically includes an in-depth analysis of the subject and an examination of its context and background information, incorporating data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and existing literature.

The ultimate aim is to provide a rich and detailed account of a situation to identify patterns and relationships, generate new insights and understanding, illustrate theories, or test hypotheses.

Importance of Business Case Study Writing

As such an in-depth exploration into a subject with potentially far-reaching consequences, a case study has benefits to offer various stakeholders in the organisation leading it.

- Business Founders: Use business case study writing to highlight real-life examples of companies or individuals who have benefited from their products or services, providing potential customers with a tangible demonstration of the value their business can bring. It can be effective for attracting new clients or investors by showcasing thought leadership and building trust and credibility.

- Marketers through case studies and encourage them to take action: Marketers use a case studies writer to showcase the success of a particular product, service, or marketing campaign. They can use persuasive storytelling to engage the reader, whether it’s consumers, clients, or potential partners.

- Researchers: They allow researchers to gain insight into real-world scenarios, explore a variety of perspectives, and develop a nuanced understanding of the factors that contribute to success or failure. Additionally, case studies provide practical business recommendations and help build a body of knowledge in a particular field.

How to Write a Case Study – The Key Elements

Considering how to write a case study can seem overwhelming at first. However, looking at it in terms of its constituent parts will help you to get started, focus on the key issue(s), and execute it efficiently and effectively.

Problem or Challenge Statement

A problem statement concisely describes a specific issue or problem that a written case study aims to address. It sets the stage for the rest of the case study and provides context for the reader.

Here are some steps to help you write a case study problem statement:

- Identify the problem or issue that the case study will focus on.

- Research the problem to better understand its context, causes, and effects.

- Define the problem clearly and concisely. Be specific and avoid generalisations.

- State the significance of the problem: Explain why the issue is worth solving. Consider the impact it has on the individual, organisation, or industry.

- Provide background information that will help the reader understand the context of the problem.

- Keep it concise: A problem statement should be brief and to the point. Avoid going into too much detail – leave this for the body of the case study!

Here is an example of a problem statement for a case study:

“ The XYZ Company is facing a problem with declining sales and increasing customer complaints. Despite improving the customer experience, the company has yet to reverse the trend . This case study will examine the causes of the problem and propose solutions to improve sales and customer satisfaction. “

Solutions and interventions

Business case study writing provides a solution or intervention that identifies the best course of action to address the problem or issue described in the problem statement.

Here are some steps to help you write a case study solution or intervention:

- Identify the objective , which should be directly related to the problem statement.

- Analyse the data, which could include data from interviews, observations, and existing literature.

- Evaluate alternatives that have been proposed or implemented in similar situations, considering their strengths, weaknesses, and impact.

- Choose the best solution based on the objective and data analysis. Remember to consider factors such as feasibility, cost, and potential impact.

- Justify the solution by explaining how it addresses the problem and why it’s the best solution with supportive evidence.

- Provide a detailed, step-by-step plan of action that considers the resources required, timeline, and expected outcomes.

Example of a solution or intervention for a case study:

“ To address the problem of declining sales and increasing customer complaints at the XYZ Company, we propose a comprehensive customer experience improvement program. “

“ This program will involve the following steps:

- Conducting customer surveys to gather feedback and identify areas for improvement

- Implementing training programs for employees to improve customer service skills

- Revising the company’s product offerings to meet customer needs better

- Implementing a customer loyalty program to encourage repeat business “

“ These steps will improve customer satisfaction and increase sales. We expect a 10% increase in sales within the first year of implementation, based on similar programs implemented by other companies in the industry. “

Possible Results and outcomes

Writing case study results and outcomes involves presenting the impact of the proposed solution or intervention.

Here are some steps to help you write case study results and outcomes:

- Evaluate the solution by measuring its effectiveness in addressing the problem statement. That could involve collecting data, conducting surveys, or monitoring key performance indicators.

- Present the results clearly and concisely, using graphs, charts, and tables to represent the data where applicable visually. Be sure to include both quantitative and qualitative results.

- Compare the results to the expectations set in the solution or intervention section. Explain any discrepancies and why they occurred.

- Discuss the outcomes and impact of the solution, considering the benefits and drawbacks and what lessons can be learned.

- Provide recommendations for future action based on the results. For example, what changes should be made to improve the solution, or what additional steps should be taken?

Example of results and outcomes for a case study:

“ The customer experience improvement program implemented at the XYZ Company was successful. We found significant improvement in employee health and productivity. The program, which included on-site exercise classes and healthy food options, led to a 25% decrease in employee absenteeism and a 15% increase in productivity . “

“ Employee satisfaction with the program was high, with 90% reporting an improved work-life balance. Despite initial costs, the program proved to be cost-effective in the long run, with decreased healthcare costs and increased employee retention. The company plans to continue the program and explore expanding it to other offices .”

Case Study Key takeaways

Key takeaways are the most important and relevant insights and lessons that can be drawn from a case study. Key takeaways can help readers understand the most significant outcomes and impacts of the solution or intervention.

Here are some steps to help you write case study key takeaways:

- Summarise the problem that was addressed and the solution that was proposed.

- Highlight the most significant results from the case study.

- Identify the key insights and lessons , including what makes the case study unique and relevant to others.

- Consider the broader implications of the outcomes for the industry or field.

- Present the key takeaways clearly and concisely , using bullet points or a list format to make the information easy to understand.

Example of key takeaways for a case study:

- The customer experience improvement program at XYZ Company successfully increased customer satisfaction and sales.

- Employee training and product development were critical components of the program’s success.

- The program resulted in a 20% increase in repeat business, demonstrating the value of a customer loyalty program.

- Despite some initial challenges, the program proved cost-effective in the long run.

- The case study results demonstrate the importance of investing in customer experience to improve business outcomes.

Steps for a Case Study Writer to Follow

If you still feel lost, the good news is as a case studies writer; there is a blueprint you can follow to complete your work. It may be helpful at first to proceed step-by-step and let your research and analysis guide the process:

- Select a suitable case study subject: Ask yourself what the purpose of the business case study is. Is it to illustrate a specific problem and solution, showcase a success story, or demonstrate best practices in a particular field? Based on this, you can select a suitable subject by researching and evaluating various options.

- Research and gather information: We have already covered this in detail above. However, always ensure all data is relevant, valid, and comes from credible sources. Research is the crux of your written case study, and you can’t compromise on its quality.

- Develop a clear and concise problem statement: Follow the guide above, and don’t rush to finalise it. It will set the tone and lay the foundation for the entire study.

- Detail the solution or intervention: Follow the steps above to detail your proposed solution or intervention.

- Present the results and outcomes: Remember that a case study is an unbiased test of how effectively a particular solution addresses an issue. Not all case studies are meant to end in a resounding success. You can often learn more from a loss than a win.

- Include key takeaways and conclusions: Follow the steps above to detail your proposed business case study solution or intervention.

Tips for How to Write a Case Study

Here are some bonus tips for how to write a case study. These tips will help improve the quality of your work and the impact it will have on readers:

- Use a storytelling format: Just because a case study is research-based doesn’t mean it has to be boring and detached. Telling a story will engage readers and help them better identify with the problem statement and see the value in the outcomes. Framing it as a narrative in a real-world context will make it more relatable and memorable.

- Include quotes and testimonials from stakeholders: This will add credibility and depth to your written case study. It also helps improve engagement and will give your written work an emotional impact.

- Use visuals and graphics to support your narrative: Humans are better at processing visually presented data than endless walls of black-on-white text. Visual aids will make it easier to grasp key concepts and make your case study more engaging and enjoyable. It breaks up the text and allows readers to identify key findings and highlights quickly.

- Edit and revise your case study for clarity and impact: As a long and involved project, it can be easy to lose your narrative while in the midst of it. Multiple rounds of editing are vital to ensure your narrative holds, that your message gets across, and that your spelling and grammar are correct, of course!

Our Final Thoughts

A written case study can be a powerful tool in your writing arsenal. It’s a great way to showcase your knowledge in a particular business vertical, industry, or situation. Not only is it an effective way to build authority and engage an audience, but also to explore an important problem and the possible solutions to it. It’s a win-win, even if the proposed solution doesn’t have the outcome you expect. So now that you know more about how to write a case study, try it or talk to us for further guidance.

Are you ready to write your own case study?

Begin by bookmarking this article, so you can come back to it. And for more writing advice and support, read our resource guides and blog content . If you are unsure, please reach out with questions, and we will provide the answers or assistance you need.

Categorised in: Resources

This post was written by Premier Prose

© 2024 Copyright Premier Prose. Website Designed by Ubie

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

- Cookie Policy

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

More information about our Cookie Policy

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

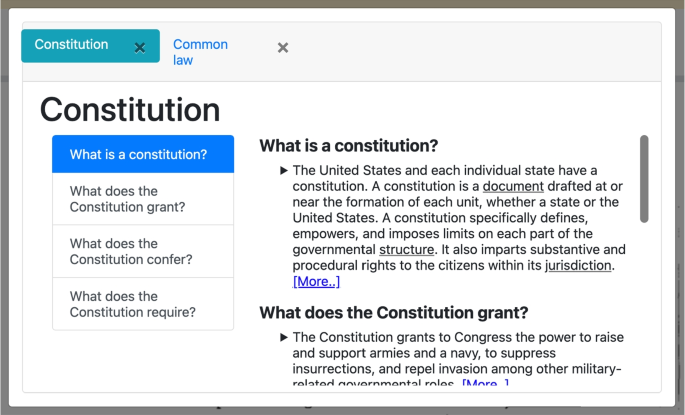

A case study research paper examines a person, place, event, condition, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis in order to extrapolate key themes and results that help predict future trends, illuminate previously hidden issues that can be applied to practice, and/or provide a means for understanding an important research problem with greater clarity. A case study research paper usually examines a single subject of analysis, but case study papers can also be designed as a comparative investigation that shows relationships between two or more subjects. The methods used to study a case can rest within a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method investigative paradigm.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010 ; “What is a Case Study?” In Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London: SAGE, 2010.

How to Approach Writing a Case Study Research Paper

General information about how to choose a topic to investigate can be found under the " Choosing a Research Problem " tab in the Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper writing guide. Review this page because it may help you identify a subject of analysis that can be investigated using a case study design.

However, identifying a case to investigate involves more than choosing the research problem . A case study encompasses a problem contextualized around the application of in-depth analysis, interpretation, and discussion, often resulting in specific recommendations for action or for improving existing conditions. As Seawright and Gerring note, practical considerations such as time and access to information can influence case selection, but these issues should not be the sole factors used in describing the methodological justification for identifying a particular case to study. Given this, selecting a case includes considering the following:

- The case represents an unusual or atypical example of a research problem that requires more in-depth analysis? Cases often represent a topic that rests on the fringes of prior investigations because the case may provide new ways of understanding the research problem. For example, if the research problem is to identify strategies to improve policies that support girl's access to secondary education in predominantly Muslim nations, you could consider using Azerbaijan as a case study rather than selecting a more obvious nation in the Middle East. Doing so may reveal important new insights into recommending how governments in other predominantly Muslim nations can formulate policies that support improved access to education for girls.

- The case provides important insight or illuminate a previously hidden problem? In-depth analysis of a case can be based on the hypothesis that the case study will reveal trends or issues that have not been exposed in prior research or will reveal new and important implications for practice. For example, anecdotal evidence may suggest drug use among homeless veterans is related to their patterns of travel throughout the day. Assuming prior studies have not looked at individual travel choices as a way to study access to illicit drug use, a case study that observes a homeless veteran could reveal how issues of personal mobility choices facilitate regular access to illicit drugs. Note that it is important to conduct a thorough literature review to ensure that your assumption about the need to reveal new insights or previously hidden problems is valid and evidence-based.

- The case challenges and offers a counter-point to prevailing assumptions? Over time, research on any given topic can fall into a trap of developing assumptions based on outdated studies that are still applied to new or changing conditions or the idea that something should simply be accepted as "common sense," even though the issue has not been thoroughly tested in current practice. A case study analysis may offer an opportunity to gather evidence that challenges prevailing assumptions about a research problem and provide a new set of recommendations applied to practice that have not been tested previously. For example, perhaps there has been a long practice among scholars to apply a particular theory in explaining the relationship between two subjects of analysis. Your case could challenge this assumption by applying an innovative theoretical framework [perhaps borrowed from another discipline] to explore whether this approach offers new ways of understanding the research problem. Taking a contrarian stance is one of the most important ways that new knowledge and understanding develops from existing literature.

- The case provides an opportunity to pursue action leading to the resolution of a problem? Another way to think about choosing a case to study is to consider how the results from investigating a particular case may result in findings that reveal ways in which to resolve an existing or emerging problem. For example, studying the case of an unforeseen incident, such as a fatal accident at a railroad crossing, can reveal hidden issues that could be applied to preventative measures that contribute to reducing the chance of accidents in the future. In this example, a case study investigating the accident could lead to a better understanding of where to strategically locate additional signals at other railroad crossings so as to better warn drivers of an approaching train, particularly when visibility is hindered by heavy rain, fog, or at night.

- The case offers a new direction in future research? A case study can be used as a tool for an exploratory investigation that highlights the need for further research about the problem. A case can be used when there are few studies that help predict an outcome or that establish a clear understanding about how best to proceed in addressing a problem. For example, after conducting a thorough literature review [very important!], you discover that little research exists showing the ways in which women contribute to promoting water conservation in rural communities of east central Africa. A case study of how women contribute to saving water in a rural village of Uganda can lay the foundation for understanding the need for more thorough research that documents how women in their roles as cooks and family caregivers think about water as a valuable resource within their community. This example of a case study could also point to the need for scholars to build new theoretical frameworks around the topic [e.g., applying feminist theories of work and family to the issue of water conservation].

Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14 (October 1989): 532-550; Emmel, Nick. Sampling and Choosing Cases in Qualitative Research: A Realist Approach . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2013; Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98 (May 2004): 341-354; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Seawright, Jason and John Gerring. "Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research." Political Research Quarterly 61 (June 2008): 294-308.

Structure and Writing Style

The purpose of a paper in the social sciences designed around a case study is to thoroughly investigate a subject of analysis in order to reveal a new understanding about the research problem and, in so doing, contributing new knowledge to what is already known from previous studies. In applied social sciences disciplines [e.g., education, social work, public administration, etc.], case studies may also be used to reveal best practices, highlight key programs, or investigate interesting aspects of professional work.

In general, the structure of a case study research paper is not all that different from a standard college-level research paper. However, there are subtle differences you should be aware of. Here are the key elements to organizing and writing a case study research paper.

I. Introduction

As with any research paper, your introduction should serve as a roadmap for your readers to ascertain the scope and purpose of your study . The introduction to a case study research paper, however, should not only describe the research problem and its significance, but you should also succinctly describe why the case is being used and how it relates to addressing the problem. The two elements should be linked. With this in mind, a good introduction answers these four questions:

- What is being studied? Describe the research problem and describe the subject of analysis [the case] you have chosen to address the problem. Explain how they are linked and what elements of the case will help to expand knowledge and understanding about the problem.

- Why is this topic important to investigate? Describe the significance of the research problem and state why a case study design and the subject of analysis that the paper is designed around is appropriate in addressing the problem.

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study? Provide background that helps lead the reader into the more in-depth literature review to follow. If applicable, summarize prior case study research applied to the research problem and why it fails to adequately address the problem. Describe why your case will be useful. If no prior case studies have been used to address the research problem, explain why you have selected this subject of analysis.

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding? Explain why your case study will be suitable in helping to expand knowledge and understanding about the research problem.

Each of these questions should be addressed in no more than a few paragraphs. Exceptions to this can be when you are addressing a complex research problem or subject of analysis that requires more in-depth background information.

II. Literature Review

The literature review for a case study research paper is generally structured the same as it is for any college-level research paper. The difference, however, is that the literature review is focused on providing background information and enabling historical interpretation of the subject of analysis in relation to the research problem the case is intended to address . This includes synthesizing studies that help to:

- Place relevant works in the context of their contribution to understanding the case study being investigated . This would involve summarizing studies that have used a similar subject of analysis to investigate the research problem. If there is literature using the same or a very similar case to study, you need to explain why duplicating past research is important [e.g., conditions have changed; prior studies were conducted long ago, etc.].

- Describe the relationship each work has to the others under consideration that informs the reader why this case is applicable . Your literature review should include a description of any works that support using the case to investigate the research problem and the underlying research questions.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research using the case study . If applicable, review any research that has examined the research problem using a different research design. Explain how your use of a case study design may reveal new knowledge or a new perspective or that can redirect research in an important new direction.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies . This refers to synthesizing any literature that points to unresolved issues of concern about the research problem and describing how the subject of analysis that forms the case study can help resolve these existing contradictions.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research . Your review should examine any literature that lays a foundation for understanding why your case study design and the subject of analysis around which you have designed your study may reveal a new way of approaching the research problem or offer a perspective that points to the need for additional research.

- Expose any gaps that exist in the literature that the case study could help to fill . Summarize any literature that not only shows how your subject of analysis contributes to understanding the research problem, but how your case contributes to a new way of understanding the problem that prior research has failed to do.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important!] . Collectively, your literature review should always place your case study within the larger domain of prior research about the problem. The overarching purpose of reviewing pertinent literature in a case study paper is to demonstrate that you have thoroughly identified and synthesized prior studies in relation to explaining the relevance of the case in addressing the research problem.

III. Method

In this section, you explain why you selected a particular case [i.e., subject of analysis] and the strategy you used to identify and ultimately decide that your case was appropriate in addressing the research problem. The way you describe the methods used varies depending on the type of subject of analysis that constitutes your case study.

If your subject of analysis is an incident or event . In the social and behavioral sciences, the event or incident that represents the case to be studied is usually bounded by time and place, with a clear beginning and end and with an identifiable location or position relative to its surroundings. The subject of analysis can be a rare or critical event or it can focus on a typical or regular event. The purpose of studying a rare event is to illuminate new ways of thinking about the broader research problem or to test a hypothesis. Critical incident case studies must describe the method by which you identified the event and explain the process by which you determined the validity of this case to inform broader perspectives about the research problem or to reveal new findings. However, the event does not have to be a rare or uniquely significant to support new thinking about the research problem or to challenge an existing hypothesis. For example, Walo, Bull, and Breen conducted a case study to identify and evaluate the direct and indirect economic benefits and costs of a local sports event in the City of Lismore, New South Wales, Australia. The purpose of their study was to provide new insights from measuring the impact of a typical local sports event that prior studies could not measure well because they focused on large "mega-events." Whether the event is rare or not, the methods section should include an explanation of the following characteristics of the event: a) when did it take place; b) what were the underlying circumstances leading to the event; and, c) what were the consequences of the event in relation to the research problem.

If your subject of analysis is a person. Explain why you selected this particular individual to be studied and describe what experiences they have had that provide an opportunity to advance new understandings about the research problem. Mention any background about this person which might help the reader understand the significance of their experiences that make them worthy of study. This includes describing the relationships this person has had with other people, institutions, and/or events that support using them as the subject for a case study research paper. It is particularly important to differentiate the person as the subject of analysis from others and to succinctly explain how the person relates to examining the research problem [e.g., why is one politician in a particular local election used to show an increase in voter turnout from any other candidate running in the election]. Note that these issues apply to a specific group of people used as a case study unit of analysis [e.g., a classroom of students].

If your subject of analysis is a place. In general, a case study that investigates a place suggests a subject of analysis that is unique or special in some way and that this uniqueness can be used to build new understanding or knowledge about the research problem. A case study of a place must not only describe its various attributes relevant to the research problem [e.g., physical, social, historical, cultural, economic, political], but you must state the method by which you determined that this place will illuminate new understandings about the research problem. It is also important to articulate why a particular place as the case for study is being used if similar places also exist [i.e., if you are studying patterns of homeless encampments of veterans in open spaces, explain why you are studying Echo Park in Los Angeles rather than Griffith Park?]. If applicable, describe what type of human activity involving this place makes it a good choice to study [e.g., prior research suggests Echo Park has more homeless veterans].