Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Endometriosis

- Excessive heat

- Mental disorders

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Observatory

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment in WHO

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Fact sheets /

Hypertension

- An estimated 1.28 billion adults aged 30–79 years worldwide have hypertension, most (two-thirds) living in low- and middle-income countries

- An estimated 46% of adults with hypertension are unaware that they have the condition.

- Less than half of adults (42%) with hypertension are diagnosed and treated.

- Approximately 1 in 5 adults (21%) with hypertension have it under control.

- Hypertension is a major cause of premature death worldwide.

- One of the global targets for noncommunicable diseases is to reduce the prevalence of hypertension by 33% between 2010 and 2030.

Hypertension (high blood pressure) is when the pressure in your blood vessels is too high (140/90 mmHg or higher). It is common but can be serious if not treated.

People with high blood pressure may not feel symptoms. The only way to know is to get your blood pressure checked.

Things that increase the risk of having high blood pressure include:

- older age

- being overweight or obese

- not being physically active

- high-salt diet

- drinking too much alcohol

Lifestyle changes like eating a healthier diet, quitting tobacco and being more active can help lower blood pressure. Some people may still need to take medicines.

Blood pressure is written as two numbers. The first (systolic) number represents the pressure in blood vessels when the heart contracts or beats. The second (diastolic) number represents the pressure in the vessels when the heart rests between beats. Hypertension is diagnosed if, when it is measured on two different days, the systolic blood pressure readings on both days is ≥140 mmHg and/or the diastolic blood pressure readings on both days is ≥90 mmHg.

Risk factors

Modifiable risk factors include unhealthy diets (excessive salt consumption, a diet high in saturated fat and trans fats, low intake of fruits and vegetables), physical inactivity, consumption of tobacco and alcohol, and being overweight or obese. In addition, there are environmental risk factors for hypertension and associated diseases, where air pollution is the most significant. Non-modifiable risk factors include a family history of hypertension, age over 65 years and co-existing diseases such as diabetes or kidney disease.

Most people with hypertension don’t feel any symptoms. Very high blood pressures can cause headaches, blurred vision, chest pain and other symptoms.

Checking your blood pressure is the best way to know if you have high blood pressure. If hypertension isn’t treated, it can cause other health conditions like kidney disease, heart disease and stroke.

People with very high blood pressure (usually 180/120 or higher) can experience symptoms including:

- severe headaches

- difficulty breathing

- blurred vision or other vision changes

- buzzing in the ears

- abnormal heart rhythm

If you are experiencing any of these symptoms and a high blood pressure, seek care immediately.

The only way to detect hypertension is to have a health professional measure blood pressure. Having blood pressure measured is quick and painless. Although individuals can measure their own blood pressure using automated devices, an evaluation by a health professional is important for assessment of risk and associated conditions.

Lifestyle changes can help lower high blood pressure. These include:

- eating a healthy, low-salt diet

- losing weight

- being physically active

- quitting tobacco.

If you have high blood pressure, your doctor may recommend one or more medicines. Your recommended blood pressure goal may depend on what other health conditions you have.

Blood pressure goal is less than 130/80 if you have:

- cardiovascular disease (heart disease or stroke)

- diabetes (high blood sugar)

- chronic kidney disease

- high risk for cardiovascular disease.

For most people, the goal is to have a blood pressure less than 140/90.

There are several common blood pressure medicines:

- ACE inhibitors including enalapril and lisinopril relax blood vessels and prevent kidney damage.

- Angiotensin-2 receptor blockers (ARBs) including losartan and telmisartan relax blood vessels and prevent kidney damage.

- Calcium channel blockers including amlodipine and felodipine relax blood vessels.

- Diuretics including hydrochlorothiazide and chlorthalidone eliminate extra water from the body, lowering blood pressure.

Lifestyle changes can help lower high blood pressure and can help anyone with hypertension. Many who make these changes will still need to take medicine.

These lifestyle changes can help prevent and lower high blood pressure.

- Eat more vegetables and fruits.

- Get at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity or 75 minutes per week of vigorous aerobic activity.

- Do strength building exercises 2 or more days each week.

- Lose weight if you’re overweight or obese.

- Take medicines as prescribed by your health care professional.

- Keep appointments with your health care professional.

Don’t:

- eat too much salty food (try to stay under 2 grams per day)

- eat foods high in saturated or trans fats

- smoke or use tobacco

- drink too much alcohol (1 drink daily max for women, 2 for men)

- miss or share medication.

Reducing hypertension prevents heart attack, stroke and kidney damage, as well as other health problems.

Reduce the risks of hypertension by:

- reducing and managing stress

- regularly checking blood pressure

- treating high blood pressure

- managing other medical conditions

- reducing exposure to polluted air.

Complications of uncontrolled hypertension

Among other complications, hypertension can cause serious damage to the heart. Excessive pressure can harden arteries, decreasing the flow of blood and oxygen to the heart. This elevated pressure and reduced blood flow can cause:

- chest pain, also called angina;

- heart attack, which occurs when the blood supply to the heart is blocked and heart muscle cells die from lack of oxygen. The longer the blood flow is blocked, the greater the damage to the heart;

- heart failure, which occurs when the heart cannot pump enough blood and oxygen to other vital body organs; and

- irregular heart beat which can lead to a sudden death.

Hypertension can also burst or block arteries that supply blood and oxygen to the brain, causing a stroke.

In addition, hypertension can cause kidney damage, leading to kidney failure.

Hypertension in low- and middle-income countries

The prevalence of hypertension varies across regions and country income groups. The WHO African Region has the highest prevalence of hypertension (27%) while the WHO Region of the Americas has the lowest prevalence of hypertension (18%).

The number of adults with hypertension increased from 594 million in 1975 to 1.13 billion in 2015, with the increase seen largely in low- and middle-income countries. This increase is due mainly to a rise in hypertension risk factors in those populations.

WHO response

The World Health Organization (WHO) supports countries to reduce hypertension as a public health problem.

In 2021, WHO released a new guideline for on the pharmacological treatment of hypertension in adults. The publication provides evidence-based recommendations for the initiation of treatment of hypertension, and recommended intervals for follow-up. The document also includes target blood pressure to be achieved for control, and information on who, in the health-care system, can initiate treatment.

To support governments in strengthening the prevention and control of cardiovascular disease, WHO and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S. CDC) launched the Global Hearts Initiative in September 2016, which includes the HEARTS technical package. The six modules of the HEARTS technical package (Healthy-lifestyle counselling, Evidence-based treatment protocols, Access to essential medicines and technology, Risk-based management, Team-based care, and Systems for monitoring) provide a strategic approach to improve cardiovascular health in countries across the world.

In September 2017, WHO began a partnership with Resolve to Save Lives, an initiative of Vital Strategies, to support national governments to implement the Global Hearts Initiative. Other partners contributing to the Global Hearts Initiative are the CDC Foundation, the Global Health Advocacy Incubator, the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and the U.S. CDC. Since implementation of the programme in 2017 in 31 countries low- and middle-income countries, 7.5 million people have been put on protocol-based hypertension treatment through person-centred models of care. These programmes demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of standardized hypertension control programmes.

- More on hypertension

High blood pressure (hypertension)

On this page, alternative medicine, coping and support, preparing for your appointment.

- Hypertension FAQs

Hi. I'm Dr. Leslie Thomas, a nephrologist at Mayo Clinic. And I'm here to answer some of the important questions you might have about hypertension.

What is the best way to measure my blood pressure at home?

Measuring your blood pressure at home is a straightforward process. Many people have a slightly higher blood pressure in one arm versus the other. So it's important to measure the blood pressures in the arm with the higher readings. It's best to avoid caffeine, exercise and, if you smoke, smoking for at least 30 minutes. To prepare for the measurement, you should be relaxed with your feet on the floor and legs uncrossed, and your back supported for at least five minutes. Your arms should be supported on a flat surface. After resting for five minutes, at least two readings are taken one minute apart in the morning prior to medications and in the evening before the evening meal. Your blood pressure monitor should be checked for proper calibration every year.

What could be causing my blood pressure to be quite erratic?

This pattern of abrupt changes in blood pressure from normal to quite high is sometimes referred to as labile blood pressure. For those who develop labile blood pressure, heart problems, hormonal problems, neurological problems, or even psychological conditions might be present. Finding and treating the underlying cause of labile blood pressure can significantly improve the condition.

Should I restrict salt to reduce my blood pressure?

It's important to note that some people with high blood pressure already consume a diet significantly restricted in sodium. And those people further restriction of dietary sodium would not necessarily be helpful or even recommended. In many people, dietary sodium intake is though relatively high. Therefore, an effective target to consider for those people is less than 1500 milligrams per day. Many though, will benefit from a target of less than a 1000 milligrams per day. Following dietary sodium restriction, it may take some time, even weeks, for the blood pressure to improve and stabilize at a lower range. So it is critically important to both be consistent with decreased sodium intake and patient when assessing for improvement.

How can I lower my blood pressure without medication?

This is a very common question. A lot of people want to avoid medication if they can, when trying to reduce their blood pressure. A few ways have been shown scientifically to reduce blood pressure. The first, and perhaps most important, is to stay physically active. Losing weight also can be important in a lot of different people. Limiting alcohol, reducing sodium intake, and increasing dietary potassium intake can all help.

What is the best medication to take for hypertension?

There's not one best medication for the treatment of hypertension for everyone. Because an individual's historical and present medical conditions must be considered. Additionally, every person has a unique physiology. Assessing how certain physiological forces may be present to contribute to the hypertension in an individual allows for a rational approach to medication choice. Antihypertensive medications are grouped by class. Each class of medication differs from the other classes by the way it lowers blood pressure. For instance, diuretics, no matter the type, act to reduce the body's total content of salt and water. This leads to reduction in plasma volume within the blood vessels and consequently a lower blood pressure. Calcium channel blockers reduce the relative constriction of blood vessels. This reduced vasoconstriction also promotes a lower blood pressure. Other classes of antihypertensive medication act in their own ways. Considering your health conditions, physiology, and how each medication works, your doctor can advise the safest and most effective medication for you.

Are certain blood pressure medications harmful to my kidneys?

Following the correction of blood pressure or the institution of certain blood pressure medications, it's pretty common to see changes in the markers for kidney function on blood tests. However, small changes in these markers, which reflects small changes in kidney filtration performance shouldn't necessarily be interpreted as absolute evidence of kidney harm. Your doctor can interpret changes in laboratory tests following any change in medication.

How can I be the best partner to my medical team?

Keep an open dialogue with your medical team about your goals and personal preferences. Communication, trust and collaboration are key to long-term success managing your blood pressure. Never hesitate to ask your medical team any questions or concerns you have. Being informed makes all the difference. Thanks for your time and we wish you well.

To diagnose high blood pressure, your health care provider examines you and asks questions about your medical history and any symptoms. Your provider listens to your heart using a device called a stethoscope.

Your blood pressure is checked using a cuff, usually placed around your arm. It's important that the cuff fits. If it's too big or too small, blood pressure readings can vary. The cuff is inflated using a small hand pump or a machine.

Blood pressure measurement

A blood pressure reading measures the pressure in the arteries when the heart beats (top number, called systolic pressure) and between heartbeats (bottom number, called diastolic pressure). To measure blood pressure, an inflatable cuff is usually placed around the arm. A machine or small hand pump is used to inflate the cuff. In this image, a machine records the blood pressure reading. This is called an automated blood pressure measurement.

The first time your blood pressure is checked, it should be measured in both arms to see if there's a difference. After that, the arm with the higher reading should be used.

Blood pressure is measured in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg). A blood pressure reading has two numbers.

- Top number, called systolic pressure. The first, or upper, number measures the pressure in the arteries when the heart beats.

- Bottom number, called diastolic pressure. The second, or lower, number measures the pressure in the arteries between heartbeats.

High blood pressure (hypertension) is diagnosed if the blood pressure reading is equal to or greater than 130/80 millimeters of mercury (mm Hg). A diagnosis of high blood pressure is usually based on the average of two or more readings taken on separate occasions.

Blood pressure is grouped according to how high it is. This is called staging. Staging helps guide treatment.

- Stage 1 hypertension. The top number is between 130 and 139 mm Hg or the bottom number is between 80 and 89 mm Hg .

- Stage 2 hypertension. The top number is 140 mm Hg or higher or the bottom number is 90 mm Hg or higher.

Sometimes the bottom blood pressure reading is normal (less than 80 mm Hg ) but the top number is high. This is called isolated systolic hypertension. It's a common type of high blood pressure in people older than 65.

If you are diagnosed with high blood pressure, your provider may recommend tests to check for a cause.

- Ambulatory monitoring. A longer blood pressure monitoring test may be done to check blood pressure at regular times over six or 24 hours. This is called ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. However, the devices used for the test aren't available in all medical centers. Check with your insurer to see if ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is a covered service.

- Lab tests. Blood and urine tests are done to check for conditions that can cause or worsen high blood pressure. For example, tests are done to check your cholesterol and blood sugar levels. You may also have lab tests to check your kidney, liver and thyroid function.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG). This quick and painless test measures the heart's electrical activity. It can tell how fast or how slow the heart is beating. During an electrocardiogram (ECG), sensors called electrodes are attached to the chest and sometimes to the arms or legs. Wires connect the sensors to a machine, which prints or displays results.

- Echocardiogram. This noninvasive exam uses sound waves to create detailed images of the beating heart. It shows how blood moves through the heart and heart valves.

Taking your blood pressure at home

Your health care provider may ask you to regularly check your blood pressure at home. Home monitoring is a good way to keep track of your blood pressure. It helps your care providers know if your medicine is working or if your condition is getting worse.

Home blood pressure monitors are available at local stores and pharmacies.

For the most reliable blood pressure measurement, the American Heart Association recommends using a monitor with a cuff that goes around your upper arm, when available.

Devices that measure your blood pressure at your wrist or finger aren't recommended by the American Heart Association because they can provide less reliable results.

More Information

- Blood pressure chart

- Blood pressure test

Changing your lifestyle can help control and manage high blood pressure. Your health care provider may recommend that you make lifestyle changes including:

- Eating a heart-healthy diet with less salt

- Getting regular physical activity

- Maintaining a healthy weight or losing weight

- Limiting alcohol

- Not smoking

- Getting 7 to 9 hours of sleep daily

Sometimes lifestyle changes aren't enough to treat high blood pressure. If they don't help, your provider may recommend medicine to lower your blood pressure.

Medications

The type of medicine used to treat hypertension depends on your overall health and how high your blood pressure is. Two or more blood pressure drugs often work better than one. It can take some time to find the medicine or combination of medicines that works best for you.

When taking blood pressure medicine, it's important to know your goal blood pressure level. You should aim for a blood pressure treatment goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg if:

- You're a healthy adult age 65 or older

- You're a healthy adult younger than age 65 with a 10% or higher risk of developing cardiovascular disease in the next 10 years

- You have chronic kidney disease, diabetes or coronary artery disease

The ideal blood pressure goal can vary with age and health conditions, particularly if you're older than age 65.

Medicines used to treat high blood pressure include:

Water pills (diuretics). These drugs help remove sodium and water from the body. They are often the first medicines used to treat high blood pressure.

There are different classes of diuretics, including thiazide, loop and potassium sparing. Which one your provider recommends depends on your blood pressure measurements and other health conditions, such as kidney disease or heart failure. Diuretics commonly used to treat blood pressure include chlorthalidone, hydrochlorothiazide (Microzide) and others.

A common side effect of diuretics is increased urination. Urinating a lot can reduce potassium levels. A good balance of potassium is necessary to help the heart beat correctly. If you have low potassium (hypokalemia), your provider may recommend a potassium-sparing diuretic that contains triamterene.

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. These drugs help relax blood vessels. They block the formation of a natural chemical that narrows blood vessels. Examples include lisinopril (Prinivil, Zestril), benazepril (Lotensin), captopril and others.

- Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs). These drugs also relax blood vessels. They block the action, not the formation, of a natural chemical that narrows blood vessels. angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) include candesartan (Atacand), losartan (Cozaar) and others.

Calcium channel blockers. These drugs help relax the muscles of the blood vessels. Some slow your heart rate. They include amlodipine (Norvasc), diltiazem (Cardizem, Tiazac, others) and others. Calcium channel blockers may work better for older people and Black people than do angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors alone.

Don't eat or drink grapefruit products when taking calcium channel blockers. Grapefruit increases blood levels of certain calcium channel blockers, which can be dangerous. Talk to your provider or pharmacist if you're concerned about interactions.

Other medicines sometimes used to treat high blood pressure

If you're having trouble reaching your blood pressure goal with combinations of the above medicines, your provider may prescribe:

- Alpha blockers. These medicines reduce nerve signals to blood vessels. They help lower the effects of natural chemicals that narrow blood vessels. Alpha blockers include doxazosin (Cardura), prazosin (Minipress) and others.

- Alpha-beta blockers. Alpha-beta blockers block nerve signals to blood vessels and slow the heartbeat. They reduce the amount of blood that must be pumped through the vessels. Alpha-beta blockers include carvedilol (Coreg) and labetalol (Trandate).

Beta blockers. These medicines reduce the workload on the heart and widen the blood vessels. This helps the heart beat slower and with less force. Beta blockers include atenolol (Tenormin), metoprolol (Lopressor, Toprol-XL, Kapspargo sprinkle) and others.

Beta blockers aren't usually recommended as the only medicine prescribed. They may work best when combined with other blood pressure drugs.

- Aldosterone antagonists. These drugs may be used to treat resistant hypertension. They block the effect of a natural chemical that can lead to salt and fluid buildup in the body. Examples are spironolactone (Aldactone) and eplerenone (Inspra).

Renin inhibitors. Aliskiren (Tekturna) slows the production of renin, an enzyme produced by the kidneys that starts a chain of chemical steps that increases blood pressure.

Due to a risk of serious complications, including stroke, you shouldn't take aliskiren with ACE inhibitors or ARBs .

- Vasodilators. These medicines stop the muscles in the artery walls from tightening. This prevents the arteries from narrowing. Examples include hydralazine and minoxidil.

- Central-acting agents. These medicines prevent the brain from telling the nervous system to increase the heart rate and narrow the blood vessels. Examples include clonidine (Catapres, Kapvay), guanfacine (Intuniv) and methyldopa.

Always take blood pressure medicines as prescribed. Never skip a dose or abruptly stop taking blood pressure medicines. Suddenly stopping certain ones, such as beta blockers, can cause a sharp increase in blood pressure called rebound hypertension.

If you skip doses because of cost, side effects or forgetfulness, talk to your care provider about solutions. Don't change your treatment without your provider's guidance.

Treating resistant hypertension

You may have resistant hypertension if:

- You take at least three different blood pressure drugs, including a diuretic. But your blood pressure remains stubbornly high.

- You're taking four different medicines to control high blood pressure. Your care provider should check for a possible second cause of the high blood pressure.

Having resistant hypertension doesn't mean your blood pressure will never get lower. If you and your provider can determine the cause, a more effective treatment plan can be created.

Treating resistant hypertension may involve many steps, including:

- Changing blood pressure medicines to find the best combination and dosage.

- Reviewing all your medicines, including those bought without a prescription.

- Checking blood pressure at home to see if medical appointments cause high blood pressure. This is called white coat hypertension.

- Eating healthy, managing weight and making other recommended lifestyle changes.

High blood pressure during pregnancy

If you have high blood pressure and are pregnant, discuss with your care providers how to control blood pressure during your pregnancy.

Potential future treatments

Researchers have been studying the use of heat to destroy specific nerves in the kidney that may play a role in resistant hypertension. The method is called renal denervation. Early studies showed some benefit. But more-robust studies found that it doesn't significantly lower blood pressure in people with resistant hypertension. More research is underway to determine what role, if any, this therapy may have in treating hypertension.

- Alpha blockers

- Angiotensin II receptor blockers

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors

- Beta blockers

- Calcium channel blockers

- Central-acting agents

- Choosing blood pressure medicines

- Vasodilators

- Beta blockers: Do they cause weight gain?

- Beta blockers: How do they affect exercise?

- Blood pressure medications: Can they raise my triglycerides?

- Calcium supplements: Do they interfere with blood pressure drugs?

- Diuretics: A cause of low potassium?

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Clinical trials.

Explore Mayo Clinic studies testing new treatments, interventions and tests as a means to prevent, detect, treat or manage this condition.

A commitment to a healthy lifestyle can help prevent and manage high blood pressure. Try these heart-healthy strategies:

- Eat healthy foods. Eat a healthy diet. Try the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. Choose fruits, vegetables, whole grains, poultry, fish and low-fat dairy foods. Get plenty of potassium from natural sources, which can help lower blood pressure. Eat less saturated fat and trans fat.

- Use less salt. Processed meats, canned foods, commercial soups, frozen dinners and certain breads can be hidden sources of salt. Check food labels for the sodium content. Limit foods and beverages that are high in sodium. A sodium intake of 1,500 mg a day or less is considered ideal for most adults. But ask your provider what's best for you.

- Limit alcohol. Even if you're healthy, alcohol can raise your blood pressure. If you choose to drink alcohol, do so in moderation. For healthy adults, that means up to one drink a day for women, and up to two drinks a day for men. One drink equals 12 ounces of beer, 5 ounces of wine or 1.5 ounces of 80-proof liquor.

- Don't smoke. Tobacco injures blood vessel walls and speeds up the process of hardening of the arteries. If you smoke, ask your care provider for strategies to help you quit.

- Maintain a healthy weight. If you're overweight or have obesity, losing weight can help control blood pressure and lower the risk of complications. Ask your health care provider what weight is best for you. In general, blood pressure drops by about 1 mm Hg with every 2.2 pounds (1 kilogram) of weight lost. In people with high blood pressure, the drop in blood pressure may be even more significant per kilogram of weight lost.

Get more exercise. Regular exercise keeps the body healthy. It can lower blood pressure, ease stress, manage weight and reduce the risk of chronic health conditions. Aim to get at least 150 minutes a week of moderate aerobic activity or 75 minutes a week of vigorous aerobic activity, or a combination of the two.

If you have high blood pressure, consistent moderate- to high-intensity workouts can lower your top blood pressure reading by about 11 mm Hg and the bottom number by about 5 mm Hg .

- Practice good sleep habits. Poor sleep may increase the risk of heart disease and other chronic conditions. Adults should aim to get 7 to 9 hours of sleep daily. Kids often need more. Go to bed and wake at the same time every day, including on weekends. If you have trouble sleeping, talk to your provider about strategies that might help.

- Manage stress. Find ways to help reduce emotional stress. Getting more exercise, practicing mindfulness and connecting with others in support groups are some ways to reduce stress.

- Try slow, deep breathing. Practice taking deep, slow breaths to help relax. Some research shows that slow, paced breathing (5 to 7 deep breaths per minute) combined with mindfulness techniques can reduce blood pressure. There are devices available to promote slow, deep breathing. According to the American Heart Association, device-guided breathing may be a reasonable nondrug option for lowering blood pressure. It may be a good option if you have anxiety with high blood pressure or can't tolerate standard treatments.

- High blood pressure and exercise

- Medication-free hypertension control

- Stress and high blood pressure

- Blood pressure medication: Still necessary if I lose weight?

- Can whole-grain foods lower blood pressure?

- High blood pressure and cold remedies: Which are safe?

- Resperate: Can it help reduce blood pressure?

- How to measure blood pressure using a manual monitor

- How to measure blood pressure using an automatic monitor

- Picnic Problems: High Sodium

- What is blood pressure?

Diet and exercise are the best ways to lower blood pressure. But some supplements are promoted as heart healthy. These supplements include:

- Fiber, such as blond psyllium and wheat bran

- Minerals, such as magnesium, calcium and potassium

- Supplements or products that increase nitric oxide or widen blood vessels — called vasodilators — such as cocoa, coenzyme Q10, L-arginine and garlic

- Omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish, high-dose fish oil supplements and flaxseed

Researchers are also studying whether vitamin D can reduce blood pressure, but evidence is conflicting. More research is needed.

Talk to your care provider before adding any supplements to your blood pressure treatment. Some can interact with medicines, causing harmful side effects that could be life-threatening.

Deep breathing or mindfulness are alternative medicine techniques that can help you relax. These practices may temporarily reduce blood pressure.

- L-arginine: Does it lower blood pressure?

High blood pressure isn't something that you can treat and then ignore. It's a condition that requires regular health checkups. Some things you can do to help manage the condition are:

- Take medicines as directed. If side effects or costs pose problems, ask your provider about other options. Don't stop taking your medicines without first talking to a care provider.

- Schedule regular health checkups. It takes a team effort to treat high blood pressure successfully. Work with your provider to bring your blood pressure to a safe level and keep it there. Know your goal blood pressure level.

- Choose healthy habits. Eat healthy foods, lose excess weight and get regular physical activity. Limit alcohol. If you smoke, quit.

- Manage stress. Say no to extra tasks, release negative thoughts, and remain patient and optimistic.

- Ask for help. Sticking to lifestyle changes can be difficult, especially if you don't see or feel any symptoms of high blood pressure. It may help to ask your friends and family to help you meet your goals.

- Join a support group. You may find that talking about any concerns with others in similar situations can help.

If you think you may have high blood pressure, make an appointment with your health care provider for a blood pressure test. You might want to wear a short-sleeved shirt to your appointment so it's easier to place the blood pressure cuff around your arm.

No special preparations are necessary for a blood pressure test. To get an accurate reading, avoid caffeine, exercise and tobacco for at least 30 minutes before the test.

Because some medicines can raise blood pressure, bring a list of all medicines, vitamins and other supplements you take and their doses to your medical appointment. Don't stop taking any medicines without your provider's advice.

Appointments can be brief. Because there's often a lot to discuss, it's a good idea to be prepared for your appointment. Here's some information to help you get ready.

What you can do

- Write down any symptoms that you're having. High blood pressure rarely has symptoms, but it's a risk factor for heart disease. Let your care provider know if you have symptoms such as chest pains or shortness of breath. Doing so can help your provider decide how aggressively to treat your high blood pressure.

- Write down important medical information, including a family history of high blood pressure, high cholesterol, heart disease, stroke, kidney disease or diabetes, and any major stresses or recent life changes.

- Make a list of all medicines, vitamins or supplements that you're taking. Include dosages.

- Take a family member or friend along, if possible. Sometimes it can be difficult to remember all the information provided to you during an appointment. Someone who accompanies you may remember something that you missed or forgot.

- Be prepared to discuss your diet and exercise habits. If you don't already follow a diet or exercise routine, be ready to talk to your care provider about any challenges you might face in getting started.

- Write down questions to ask your provider.

Preparing a list of questions can help you and your provider make the most of your time together. List your questions from most important to least important in case time runs out. For high blood pressure, some basic questions to ask your provider include:

- What kinds of tests will I need?

- What is my blood pressure goal?

- Do I need any medicines?

- Is there a generic alternative to the medicine you're prescribing for me?

- What foods should I eat or avoid?

- What's an appropriate level of physical activity?

- How often do I need to schedule appointments to check my blood pressure?

- Should I monitor my blood pressure at home?

- I have other health conditions. How can I best manage them together?

- Are there brochures or other printed material that I can have? What websites do you recommend?

Don't hesitate to ask any other questions that you might have.

What to expect from your doctor

Your health care provider is likely to ask you questions. Being ready to answer them may reserve time to go over any points you want to spend more time on. Your provider may ask:

- Do you have a family history of high cholesterol, high blood pressure or heart disease?

- What are your diet and exercise habits like?

- Do you drink alcohol? How many drinks do you have in a week?

- Do you smoke?

- When did you last have your blood pressure checked? What was the result?

What you can do in the meantime

It's never too early to make healthy lifestyle changes, such as quitting smoking, eating healthy foods and getting more exercise. These are the main ways to protect yourself against high blood pressure and its complications, including heart attack and stroke.

Feb 29, 2024

- High blood pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/high-blood-pressure. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- Flynn JT, et al. Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017; doi:10.1542/peds.2017-1904.

- Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2nd ed. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/our-work/physical-activity/current-guidelines. Accessed June 15, 2022.

- Hypertension in adults: Screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hypertension-in-adults-screening. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- Thomas G, et al. Blood pressure measurement in the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension in adults. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- Muntner P, et al. Measurement of blood pressure in humans: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2019; doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000087.

- Basile J, et al. Overview of hypertension in adults. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed July 22, 2022.

- Know your risk factors for high blood pressure. American Heart Association. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/why-high-blood-pressure-is-a-silent-killer/know-your-risk-factors-for-high-blood-pressure. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- Rethinking drinking. Alcohol and your health. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. https://www.rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov/Default.aspx. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- Libby P, et al., eds. Systemic hypertension: Mechanisms, diagnosis, and treatment. In: Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 12th ed. Elsevier; 2022. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- AskMayoExpert. Hypertension (adult). Mayo Clinic; 2021.

- About metabolic syndrome. American Heart Association. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/metabolic-syndrome/about-metabolic-syndrome. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- Understanding blood pressure readings. American Heart Association. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/understanding-blood-pressure-readings. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- Whelton PK, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018; doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065.

- Monitoring your blood pressure at home. American Heart Association. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/understanding-blood-pressure-readings/monitoring-your-blood-pressure-at-home. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- Mann JF. Choice of drug therapy in primary (essential) hypertension. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- Agasthi P, et al. Renal denervation for resistant hypertension in the contemporary era: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports. 2019; doi:10.1038/s41598-019-42695-9.

- Chernova I, et al. Resistant hypertension updated guidelines. Current Cardiology Reports. 2019; doi:10.1007/s11886-019-1209-6.

- Forman JP, et al. Diet in the treatment and prevention of hypertension. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- Goldman L, et al., eds. Cognitive impairment and dementia. In: Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Elsevier; 2020. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- Managing stress to control high blood pressure. American Heart Association. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/changes-you-can-make-to-manage-high-blood-pressure/managing-stress-to-control-high-blood-pressure. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- Brenner J, et al. Mindfulness with paced breathing reduces blood pressure. Medical Hypothesis. 2020; doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109780.

- Grundy SM, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019; doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625.

- Monitoring your blood pressure at home. American Heart Association. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/understanding-blood-pressure-readings/monitoring-your-blood-pressure-at-home. Accessed July 22, 2022.

- Natural medicines in the clinical management of hypertension. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed Dec. 20, 2020.

- Saper RB, et al. Overview of herbal medicine and dietary supplements. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- Lopez-Jimenez F (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. Aug. 19, 2022.

- 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- Börjesson M, et al. Physical activity and exercise lower blood pressure in individuals with hypertension: Narrative review of 27 RCTs. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2016; doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095786.

- Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Life's essential 8: Updating and enhancing the American Heart Association's construct of cardiovascular health: A presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022; doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001078.

- American Heart Association adds sleep to cardiovascular health checklist. American Heart Association. https://newsroom.heart.org/news/american-heart-association-adds-sleep-to-cardiovascular-health-checklist. Accessed July 15, 2022.

- Symptoms & causes

- Doctors & departments

- Diseases & Conditions

- High blood pressure (hypertension) diagnosis & treatment

News from Mayo Clinic

- Alcohol: Does it affect blood pressure?

- Anxiety: A cause of high blood pressure?

- Blood pressure cuff: Does size matter?

- Blood pressure readings: Why higher at home?

- Blood pressure: Can it be higher in one arm?

- Blood pressure: Does it have a daily pattern?

- Blood pressure: Is it affected by cold weather?

- Caffeine and hypertension

- Can having vitamin D deficiency cause high blood pressure?

- Free blood pressure machines: Are they accurate?

- High blood pressure and sex

- High blood pressure dangers

- Home blood pressure monitoring

- Hypertensive crisis: What are the symptoms?

- Isolated systolic hypertension: A health concern?

- Medications and supplements that can raise your blood pressure

- Menopause and high blood pressure: What's the connection?

- Pulse pressure: An indicator of heart health?

- Sleep deprivation: A cause of high blood pressure?

- What is hypertension? A Mayo Clinic expert explains.

- White coat hypertension

- Wrist blood pressure monitors: Are they accurate?

Associated Procedures

Products & services.

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on High Blood Pressure

- Blood Pressure Monitors at Mayo Clinic Store

- The Mayo Clinic Diet Online

CON-XXXXXXXX

5X Challenge

Thanks to generous benefactors, your gift today can have 5X the impact to advance AI innovation at Mayo Clinic.

- Hypertension

- Author: Mackenzie Samson, MD; Chief Editor: Eric H Yang, MD more...

- Sections Hypertension

- Practice Essentials

- Pathophysiology

- Epidemiology

- Patient Education

- Physical Examination

- Hypertension and Cerebrovascular Disease

- Hypertensive Emergencies

- Hypertensive Heart Disease

- Hypertension in Pediatric Patients

- Hypertension in Pregnancy

- Primary Aldosteronism

- Approach Considerations

- Baseline Laboratory Evaluation

- Radiologic Studies

- Nonpharmacologic Therapy

- Pharmacologic Therapy

- Management of Diabetes and Hypertension

- Management of Hypertensive Emergencies

- Management of Hypertension in Pregnancy

- Management of Hypertension in Pediatric Patients

- Management of Hypertension in the Elderly

- Management of Hypertension in Black Patients

- Management of Ocular Hypertension

- Management of Renovascular Hypertension

- Management of Resistant Hypertension

- Management of Pseudohypertension

- Management of Pheochromocytoma

- Management of Primary Hyperaldosteronism

- Interventions for Improving Blood Pressure Control

- Medication Summary

- Diuretics, Thiazide

- Diuretic, Potassium-Sparing

- Diuretics, Loop

- Beta-Blockers, Beta-1 Selective

- Beta-Blockers, Alpha Activity

- Beta-Blockers, Intrinsic Sympathomimetic

- Vasodilators

- Calcium Channel Blockers

- Aldosterone Antagonists, Selective

- Alpha2-agonists, Central-acting

- Renin Inhibitors/Combos

- Alpha-Blockers, Antihypertensives

- Antihypertensives, Other

- Antihypertensive Combinations

- Endothelin Antagonists

- Questions & Answers

- Media Gallery

High blood pressure (BP), or hypertension, is defined by two levels by the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines [ 1 , 2 ] : (1) elevated BP, with a systolic pressure (SBP) between 120 and 129 mm Hg and diastolic pressure (DBP) less than 80 mm Hg, and (2) stage 1 hypertension, with an SBP of 130 to 139 mm Hg or a DBP of 80 to 89 mm Hg.

Hypertension is the most common primary diagnosis in the United States. [ 3 ] It affects approximately 86 million adults (≥20 years) in the United States [ 4 ] and is a major risk factor for stroke, myocardial infarction, vascular disease, and chronic kidney disease.

Signs and symptoms of hypertension

The 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines provide the following definitions and classifications of elevated BP and stages of hypertension [ 1 , 2 ] :

Elevated BP with a systolic pressure between 120 and 129 mm Hg and diastolic pressure less than 80 mm Hg

Stage 1 hypertension, with a systolic pressure of 130 to 139 mm Hg or a diastolic pressure of 80 to 89 mm Hg

- Stage 2 hypertension, with a systolic pressure of 140 mm Hg or greater or a diastolic pressure of 90 mm Hg or greater

Of note, the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) have a higher BP threshold, defining hypertension as an SBP of 140 mm Hg or greater and/or a DBP of 90 mm Hg or above. [ 5 , 6 ]

Hypertension may be primary, which may develop as a result of a variety of environmental or genetic causes, or it may be secondary to renal, vascular, and endocrine causes. Primary or essential hypertension accounts for 90-95% of adult cases, and secondary hypertension accounts for 2-10% of adult cases.

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis of hypertension

The evaluation of hypertension involves accurately measuring the patient’s BP, performing a focused medical history and physical examination, and obtaining results of routine laboratory studies. [ 7 , 8 ] A 12-lead electrocardiogram should also be obtained. These steps can help determine the following [ 7 , 8 , 9 ] :

Presence of end-organ disease

Possible causes of hypertension

Cardiovascular risk factors

Baseline values for judging biochemical effects of therapy

Other studies may be obtained on the basis of clinical findings or in individuals with suspected secondary hypertension and/or evidence of target-organ disease, such as complete blood cell (CBC) count, basic metabolic panel; chest radiograph, transthoracic echocardiogram; and urine microalbumin. [ 7 ]

See Workup for more detail.

Management of hypertension

Many guidelines exist for the management of hypertension. Most groups, including the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood (JNC), the American Diabetes Associate (ADA), and the ACC/AHA recommend lifestyle modification as the first step in managing hypertension.

Lifestyle modifications

JNC 7 recommendations to lower BP and decrease cardiovascular disease risk include the following, with greater results achieved when two or more lifestyle modifications are combined [ 7 ] :

Weight loss (range of approximate SBP reduction, 5-20 mm Hg per 10 kg)

Limit alcohol intake to no more than 1 oz (30 mL) of ethanol per day for men or 0.5 oz (15 mL) of ethanol per day for women and people of lighter weight (range of approximate SBP reduction, 2-4 mm Hg)

Reduce sodium intake to no more than 100 mmol/day (2.4 g sodium or 6 g sodium chloride; range of approximate SBP reduction, 2-8 mm Hg) [ 10 ]

Maintain adequate intake of dietary potassium (approximately 90 mmol/day)

Maintain adequate intake of dietary calcium and magnesium for general health

Stop smoking and reduce intake of dietary saturated fat and cholesterol for overall cardiovascular health

Engage in aerobic exercise at least 30 minutes daily for most days (range of approximate SBP reduction, 4-9 mm Hg)

The ACC/AHA recommends a diet that is low in sodium, is high in potassium, and promotes the consumption of fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products for reducing BP and lowering the risk of cardiovascular events. Other recommendations include increasing physical activity (30 minutes or more of moderate intensity activity on a daily basis) and losing weight (persons with overweight and obesity). [ 1 ]

The 2018 ESC and the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) guidelines recommend a low-sodium diet (limited to 2 g per day) as well as reducing body-mass index (BMI) to 20-25 kg/m 2 and waist circumference (to < 94 cm in men and < 80 cm in women). [ 11 ] The 2023 ESH guidelines for managing arterial hypertension indicates a linear reduction in BP with sodium intake limited to as low as 800 mg/day; when dietary sodium intake fell from about 3.6 g/day to around 2.7 g/day, there was an associated 18-26% fall in cardiovascular disease. [ 6 ]

Pharmacologic therapy

If lifestyle modifications are insufficient to achieve the goal BP, there are several drug options for treating and managing hypertension. Thiazide diuretics, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI)/angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), or calcium channel blocker (CCB) are the preferred first-line agents. [ 1 ] Often, patients require several antihypertensive agents to achieve adequate BP control.

Compelling indications for specific agents include comorbidities such as heart failure, ischemic heart disease, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes. Drug intolerability or contraindications may also be factors. [ 7 ]

The following are drug class recommendations for compelling indications based on various clinical trials [ 7 ] :

Heart failure: Diuretic, beta-blocker, ACE inhibitor/ARB/ARNI, aldosterone antagonist

Following myocardial infarction: Beta-blocker, ACE inhibitor

Diabetes: ACE inhibitor/ARB

Chronic kidney disease: ACE inhibitor/ARB

Although the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines favor CCBs or thiazide diuretics in the absence of other indications as first-line medications in Black hypertensive populations, [ 1 ] reports in relatively recent years have raised questions on the benefits of race or ethnicity-based medication prescribing. [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ]

See Treatment and Medication for more details.

Hypertension is the most common primary diagnosis in the United States, [ 3 ] and it is one of the most common worldwide diseases afflicting humans. It is a major risk factor for stroke, myocardial infarction, vascular disease, and chronic kidney disease. Despite extensive research over the past several decades, the etiology of most cases of adult hypertension is still unknown, and control of blood pressure (BP) is suboptimal in the general population. Due to the associated morbidity and mortality and cost to society, preventing and treating hypertension is an important public health challenge. Fortunately, relatively recent advances and trials in hypertension research are leading to an increased understanding of the pathophysiology of hypertension and the promise for novel pharmacologic and interventional treatments for this widespread disease.

According to the American Heart Association (AHA), approximately 86 million adults (34%) in the United States are affected by hypertension, which is defined as a systolic BP (SBP) of 130 mm Hg or more or a diastolic BP (DBP) of 80 mm Hg or more, taking antihypertensive medication, or having been told by clinicians on at least two occasions as having hypertension. [ 1 ] Substantial efforts have been made to enhance awareness and treatment of hypertension. However, a National Health Examination Survey (NHANES) spanning 2011-2014 revealed that 34% of US adults aged 20 years and older are hypertensive and NHANES 2013-2014 data showed that 15.9% of these hypertensive adults are unaware they are hypertensive; these data have increased from NHANES 2005-2006 data that showed 29% of US adults aged 18 years and older were hypertensive and that 7% of these hypertensive adults had never been told that they had hypertension. [ 4 ]

Of those with elevated BP, 78% were aware they were hypertensive, 68% were being treated with antihypertensive agents, and only 64% of treated individuals had controlled hypertension. [ 4 ] In addition, previous data from NHANES estimated that 52.6% (NHANES 2009-2010) to 55.8% (NHANES 1999-2000) of adults aged 20 years and older have elevated BP or stage 1 hypertension, defined as an untreated SBP of 120-139 mm Hg or untreated DBP of 80-89 mm Hg. [ 4 ] (See Epidemiology .)

Hypertension is the most important modifiable risk factor for coronary heart disease (the leading cause of death in North America), stroke (the third leading cause), congestive heart failure, end-stage renal disease, and peripheral vascular disease. Therefore, healthcare professionals must not only identify and treat patients with hypertension but also promote a healthy lifestyle and preventive strategies to decrease the prevalence of hypertension in the general population. (See Treatment .)

Definition and classification

The definition of abnormally high blood pressure (BP) has varied among guidelines. Nevertheless, the relationship between systemic arterial pressure and morbidity appears to be quantitative rather than qualitative. A level for high BP must be agreed upon in clinical practice for screening patients with hypertension and for instituting diagnostic evaluation and initiating therapy. Because the risk to an individual patient may correlate with the severity of hypertension, a classification system is essential for making decisions about aggressiveness of treatment or therapeutic interventions. (See Presentation .)

Based on recommendations of the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines, the classification of BP (expressed in mm Hg) for adults aged 18 years or older is as follows [ 1 , 2 ] :

Normal: Systolic lower than 120 mm Hg and diastolic lower than 80 mm Hg

Elevated: Systolic 120-129 mm Hg and diastolic lower than 80 mm Hg

Stage 1: Systolic 130-139 mm Hg or diastolic 80-89 mm Hg

Stage 2: Systolic 140 mm Hg or greater or diastolic 90 mm Hg or greater

The classification above is based on the average of two or more readings taken at each of two or more visits after the initial screening. [ 1 ] Normal BP with respect to cardiovascular risk is less than 120/80 mm Hg. However, unusually low readings should be evaluated for clinical significance.

From another perspective, hypertension may be categorized as either primary or secondary. Primary (essential) hypertension is diagnosed in the absence of an identifiable secondary cause. Approximately 90-95% of adults with hypertension have primary hypertension, whereas secondary hypertension accounts for about 5-10% of the cases. [ 21 ] However, secondary forms of hypertension, such as primary hyperaldosteronism, account for as much as 30% of resistant hypertension (hypertension in which BP is >140/90 mm Hg despite the use of medications from three or more drug classes, one of which is a thiazide diuretic).

Especially severe cases of hypertension, or hypertensive crises, are defined as a BP of more than 180/120 mm Hg and may be further categorized as hypertensive emergencies or urgencies. Hypertensive emergencies are characterized by evidence of impending or progressive target organ dysfunction, whereas hypertensive urgencies are those situations without target organ dysfunction. [ 7 ]

Acute end-organ damage in the setting of a hypertensive emergency may include the following [ 22 ] :

Neurologic: hypertensive encephalopathy, cerebral vascular accident/cerebral infarction, subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracranial hemorrhage

Cardiovascular: myocardial ischemia/infarction, acute left ventricular dysfunction, acute pulmonary edema, aortic dissection, unstable angina pectoris

Other: acute renal failure/insufficiency, retinopathy, eclampsia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia

With the advent of antihypertensives, the incidence of hypertensive emergencies has declined from 7% to approximately 1%. [ 23 ] In addition, the 1-year survival rate associated with this condition has increased from only 20% (prior to 1950) to more than 90% with appropriate medical treatment. [ 24 ] (See Medication .)

The pathogenesis of primary hypertension is multifactorial and complex. [ 25 ] Multiple factors modulate the blood pressure (BP) including humoral mediators, vascular reactivity, circulating blood volume, vascular caliber, blood viscosity, cardiac output, blood vessel elasticity, and neural stimulation. The pathogenesis of primary hypertension involves multiple factors, including genetic predisposition, excess dietary salt intake, adrenergic tone, and renal sodium and water handling that interact to produce BP elevations. Although genetics contribute, with rare exceptions this condition is polygenic. Emerging evidence suggests a role for immune cell activation and the microbiome in the pathogenesis of hypertension. [ 26 ]

The natural history of primary hypertension evolves from occasional to established hypertension. After a long asymptomatic period, persistent hypertension develops into complicated hypertension, in which end-organ damage to the aorta and small arteries, heart, kidneys, retina, and central nervous system is evident.

A general progression of primary hypertension is as follows:

Prehypertension in persons aged 10-30 years (by increased cardiac output)

Early hypertension in persons aged 20-40 years (in which increased peripheral resistance is prominent)

Established hypertension in persons aged 30-50 years

Complicated hypertension in persons aged 40-60 years

As evident from the above, younger individuals may present with hypertension associated with an elevated cardiac output (high-output hypertension). High-output hypertension results from volume and sodium retention by the kidney, leading to increased stroke volume and, often, with cardiac stimulation by adrenergic hyperactivity. Systemic vascular resistance is generally not increased at such earlier stages of hypertension. As hypertension is sustained, however, vascular adaptations including remodeling, vasoconstriction, and vascular rarefaction occur, leading to increased systemic vascular resistance. In this situation, cardiac output is generally normal or slightly reduced, and circulating blood volume is normal.

Cortisol reactivity, an index of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function, may be another mechanism by which psychosocial stress is associated with future hypertension. [ 27 ] In a prospective sub-study of the Whitehall II cohort, with 3 years follow-up of an occupational cohort in previously healthy patients, investigators reported 15.9% of the patient group developed hypertension in response to laboratory-induced mental stressors, and there was an association between cortisol stress reactivity and incident hypertension. [ 27 ]

Investigations into the pathophysiology of hypertension, both in animals and humans, have revealed that hypertension may have an immunologic basis. Studies have revealed that hypertension is associated with renal infiltration of immune cells and that pharmacologic immunosuppression (such as with the drug mycophenolate mofetil) or pathologic immunosuppression (such as occurs with human immunovirus [HIV] deficiency) results in reduced BP in animals and humans. Evidence suggests that T lymphocytes and T-cell derived cytokines (eg, interleukin 17, tumor necrosis factor alpha) play an important role in hypertension. [ 28 , 29 ]

One hypothesis is that prehypertension results in oxidation of lipids such as arachidonic acid that leads to the formation of isoketals or isolevuglandins, which function as neoantigens, which are then presented to T cells, leading to T-cell activation and infiltration of critical organs (eg, kidney, vasculature). [ 30 ] This results in persistent or severe hypertension and end-organ damage. Sympathetic nervous system activation and noradrenergic stimuli have also been shown to promote T-lymphocyte activation and infiltration, and contribute to the pathophysiology of hypertension. [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]

Hypertension can be primary, which may develop as a result of environmental or genetic causes, or secondary, which has multiple etiologies, including renal, vascular, and endocrine causes. Primary or essential hypertension accounts for 90-95% of adult cases, and a small percentage of patients (2-10%) have a secondary cause. Hypertensive emergencies are most often precipitated by inadequate medication or poor adherence.

Environmental and genetic/epigenetic causes

Hypertension develops secondary to environmental factors, as well as multiple genes, whose inheritance appears to be complex. [ 24 , 34 ] Furthermore, obesity, diabetes, and heart disease also have genetic components and contribute to hypertension. Epidemiologic studies using twin data and data from Framingham Heart Study families reveal that blood pressure (BP) has a substantial heritable component, ranging from 33% to 57%. [ 35 , 36 , 37 ]

In an attempt to elucidate the genetic components of hypertension, multiple genome wide association studies (GWAS) have been conducted, revealing multiple gene loci in known pathways of hypertension as well as some novel genes with no known link to hypertension as of yet. [ 38 ] Further research into these novel genes, some of which are immune-related, will likely increase the understanding of the pathophysiology of hypertension, allowing for increased risk stratification and individualized treatment.

Epigenetic phenomena, such as DNA methylation and histone modification, have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of hypertension. For example, a high-salt diet appears to unmask nephron development caused by methylation. Maternal water deprivation and protein restriction during pregnancy increase renin-angiotensin expression in the fetus. Mental stress induces a DNA methylase, which enhances autonomic responsiveness. The pattern of serine protease inhibitor gene methylation predicts preeclampsia in pregnant women. [ 39 ]

Despite these genetic findings, targeted genetic therapy seems to have little impact on hypertension. In the general population, not only does it appear that individual and joint genetic mutations have very small effects on BP levels, but it has not been shown that any of these genetic abnormalities are responsible for any applicable percentage of cases of hypertension in the general population. [ 40 ]

Secondary causes of hypertension related to single genes are very rare. They include Liddle syndrome, glucocorticoid-remediable hyperaldosteronism, 11 beta-hydroxylase and 17 alpha-hydroxylase deficiencies, syndrome of apparent mineralocorticoid excess, and pseudohypoaldosteronism type II. [ 7 ]

Causes of secondary hypertension

Renal causes (2.5-6%) of hypertension include the renal parenchymal diseases and renal vascular diseases, as follows:

Polycystic kidney disease

Chronic kidney disease

Urinary tract obstruction

Renin-producing tumor

Liddle syndrome

- Nephritic syndrome/glomerulonephritis

Renovascular hypertension (RVHT) causes 0.2-4% of cases of hypertension. Since the 1934 seminal experiment by Goldblatt et al, [ 41 ] RVHT has become increasingly recognized as an important cause of clinically atypical hypertension and chronic kidney disease—the latter by virtue of renal ischemia. The coexistence of renal arterial vascular (ie, renovascular) disease and hypertension roughly defines this type of secondary hypertension. More specific diagnoses are made retrospectively when hypertension is improved after intravascular intervention.

Vascular causes include the following:

Coarctation of the aorta

Collagen vascular disease

Endocrine causes may account for the largest proportion of secondary hypertension (10-20%) and include exogenous or endogenous hormonal imbalances. Exogenous causes include administration of steroids. Primary hyperaldosteronism is the most common endogenous hormone abnormality causing hypertension. Approximately 20% of cases of confirmed resistant hypertension are due to primary hyperaldosteronism. Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas are rare, chromaffin cell tumors, that produce catecholamines. The prevalence of these tumors is 0.01-0.2% in the hypertensive population, but up to 4% in the resistant hypertension population. Cushing syndrome is caused by excess glucocorticoids and can present in a variety of ways, including weight gain, menstrual irregularities, mood disorders, muscle weakness, abdominal striae, and enlargement of the pad fat on the dorsal neck. Small cohort studies suggest a high prevalence of hypertension in patients with Cushing syndrome; further studies are needed for accurate correlation. [ 42 ]

Another common endocrine cause of hypertension is oral contraceptive use, likely due to activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). This is caused by increased hepatic synthesis of angiotensinogen in response to the estrogen component of oral contraceptives. Approximately 5% of women taking oral contraceptives may develop hypertension, which abates within 6 months after discontinuation. The risk factors for oral contraceptive–associated hypertension include coexistent renal disease, familial history of primary hypertension, age older than 35 years, and obesity.

Exogenous administration of steroids used for therapeutic purposes also increases BP, especially in susceptible individuals, mainly by volume expansion. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may also have adverse effects on BP. NSAIDs block both cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and COX-2 enzymes. The inhibition of COX-2 can inhibit its natriuretic effect, which, in turn, increases sodium retention. NSAIDs also inhibit the vasodilating effects of prostaglandins and the production of vasoconstricting factors—namely, endothelin-1. These effects can contribute to the induction of hypertension in a normotensive or controlled hypertensive patient.

Endogenous hormonal causes include the following:

Primary hyperaldosteronism

Cushing syndrome

Pheochromocytoma

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia

Neurogenic causes include the following:

Brain tumor

Autonomic dysfunction

Sleep apnea

Intracranial hypertension

Drugs and toxins that cause hypertension include the following:

Cyclosporine, tacrolimus

Erythropoietin

Adrenergic medications

Decongestants containing ephedrine

Herbal remedies and candy that contain licorice (including licorice root) or ephedrine (and ephedra)

Other causes include the following:

Hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism

Hypercalcemia

Hyperparathyroidism

Obstructive sleep apnea

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common but frequently undiagnosed sleep-related breathing disorder defined as an average of at least five apneic and hypopneic episodes per sleep hour, with associated symptoms, including excessive daytime sleepiness. [ 43 ] Multiple studies have shown OSA to be an independent risk factor for the development of primary hypertension, even after adjusting for age, sex, and degree of obesity.

Approximately half of individuals with hypertension have OSA, and approximately half with OSA have hypertension. Ambulatory BP monitoring normally reveals a "dip" in BP of at least 10% during sleep. However, if a patient is a "nondipper," the chances that the patient has OSA is increased. Nondipping is thought to be caused by frequent apneic/hypopneic episodes that end with arousals associated with marked spikes in BP that last for several seconds. Apneic episodes are associated with striking increases in sympathetic nerve activity and enormous elevations of BP. Individuals with sleep apnea have increased cardiovascular mortality, in part likely related to the high incidence of hypertension.

Although treatment of sleep apnea with continuous airway positive pressure (CPAP) would logically seem to improve cardiovascular outcomes and hypertension, studies evaluating this mode of therapy have been disappointing. A 2016 review of several studies indicated that CPAP either had no effect or a modest BP-lowering effect. [ 44 ] Findings from the SAVE (Sleep Apnea Cardiovascular Endpoints) study showed no effect of CPAP therapy on BP above usual care. [ 45 ] It is likely that patients with sleep apnea have other etiologies of hypertension, including obesity, hyperaldosteronism, increased sympathetic drive, and activation of the renin/angiotensin system that contribute to their hypertension. Although CPAP remains an effective therapy for other aspects of sleep apnea, it should not be expected to normalize BP in the majority of patients.

Causes of hypertensive emergencies

The most common hypertensive emergency is a rapid unexplained rise in BP in patients with chronic essential hypertension. Most patients who develop hypertensive emergencies have a history of inadequate hypertensive treatment or an abrupt discontinuation of their medications. [ 46 , 47 ]

Other causes of hypertensive emergencies include the use of recreational drugs, abrupt clonidine withdrawal, post pheochromocytoma removal, and systemic sclerosis, as well as the following:

Renal parenchymal disease: chronic pyelonephritis, primary glomerulonephritis, tubulointerstitial nephritis (accounts for 80% of all secondary causes)

Systemic disorders with renal involvement: systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, vasculitis

Renovascular disease: atherosclerotic disease, fibromuscular dysplasia, polyarteritis nodosa

Endocrine disease: pheochromocytoma, Cushing syndrome, primary hyperaldosteronism

Drugs: cocaine, [ 48 ] amphetamines, cyclosporine, clonidine (withdrawal), phencyclidine, diet pills, oral contraceptive pills

Drug interactions: monoamine oxidase inhibitors with tricyclic antidepressants, antihistamines, or tyramine-containing food

Central nervous system (CNS) factors: CNS trauma or spinal cord disorders, such as Guillain-Barré syndrome

Preeclampsia/eclampsia

Postoperative hypertension

Hypertension is a worldwide epidemic; accordingly, its epidemiology has been well studied. Data from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) spanning 2011-2014 found that of those in the population aged 20 years or older, an estimated 86 million adults had hypertension, with a prevalence of 34%. [ 4 ]

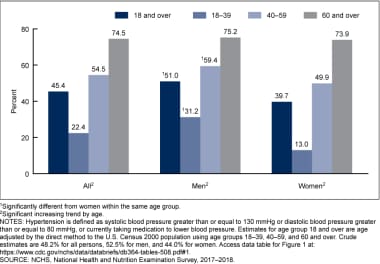

More recently, 2020 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) spanning 2017-2018 show a 45.4% prevalence of hypertension among those aged 18 and older (see the following image; prevalence by sex and age). [ 49 ] Of the US adult population diagnosed with hypertension, a higher prevalence exists in males (51%) relative to females (39.7%).

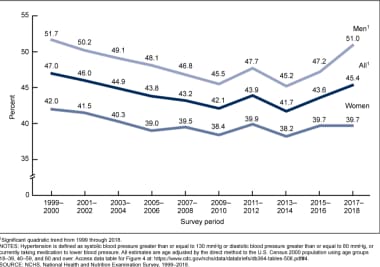

There has been an interesting trend in the prevalence of hypertension, which fell in the early 2000s but began trending upward in 2014 (see the image below, which shows the prevalence of hypertension by year and sex). [ 49 ] The prevalence of hypertension declined during the first decade of this century, but it has since increased, particularly in men.

Globally, an estimated 26% of the world’s population (972 million people) has hypertension, and the prevalence is expected to increase to 29% by 2025, driven largely by increases in economically developing nations. [ 50 ] The high prevalence of hypertension exacts a tremendous public health burden. For example, as a primary contributor to heart disease and stroke, the first and third leading causes of death worldwide, respectively, high BP was the top modifiable risk factor for disability adjusted life-years lost worldwide in 2013. [ 51 , 52 ]

Hypertension and sex- and age-related statistics

Females have a lower prevalence of hypertension until the fifth decade of life. Afterward, the prevalence of hypertension is increased in females compared to males. [ 1 ]

Hypertension and race and ethnicity

Black adults have among the highest rates of hypertension, with an increasing prevalence, in the United States and globally. [ 17 , 18 , 19 , 53 ] Although White adults also have an increasing incidence of high BP, they develop this condition later in life than Black adults and have much lower average BPs. In fact, compared to hypertensive White persons, hypertensive Black individuals have a 1.3-fold higher rate of nonfatal stroke, a 1.8-fold higher rate of fatal stroke, a 1.5-fold higher mortality rate due to heart disease, and a 4.2-fold higher rate of end-stage renal disease (ESRD). [ 54 ]

Table 2, below, summarizes age-adjusted prevalence estimates from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) and the NCHS according to racial/ethnic groups and diagnosed conditions in individuals aged 18 years and older.

Table 2. NHIS/NCHS Age-Adjusted Prevalence Estimates in Individuals Aged 18 Years and Older in 2015. (Open Table in a new window)

Race/Ethnic Group | Have Hypertension, % | Have Heart Disease, % | Have Coronary Heart Disease, % | Have Had a Stroke, % |

White only | 23.8 | 11.3 | 5.6 | 2.4 |

Black/African American | 34.4 | 9.5 | 5.4 | 3.7 |

Hispanic/Latino | 23.0 | 8.2 | 5.1 | 2.4 |

Asian | 20.6 | 7.1 | 3.7 | 1.4 |

American Indian/Alaska Native | 28.4 | 13.7 | 9.3 | 2.2 (this number is considered unreliable) |

Source: Summary health statistics: National Health Interview Survey, 2015. Available at: . Accessed: November 14, 2016. NCHS = National Center for Health Statistics; NHIS = National Health Interview Survey. | ||||

Most individuals diagnosed with hypertension will have increasing blood pressure (BP) as they age. Untreated hypertension is notorious for raising the mortality risk and is often described as a silent killer. Mild to moderate hypertension, if left untreated, may be associated with a risk of atherosclerotic disease in 30% of people and of organ damage in 50% of persons within 8-10 years after onset. Patients with resistant hypertension are also at higher risk for poor outcomes, particularly those with certain comorbidities (eg, chronic kidney disease, ischemic heart disease). [ 55 ] Patients with resistant hypertension who have lower BP appear to have a reduced risk for some cardiovascular events (eg, incident stroke, coronary heart disease, or heart failure). [ 55 ]

Death from ischemic heart disease or stroke increases progressively as BP increases. For every 20 mm Hg systolic or 10 mm Hg diastolic increase in BP above 115/75 mm Hg, mortality doubles for both ischemic heart disease and stroke. [ 7 ]

Hypertensive retinopathy was associated with an increased long-term risk of stroke, even in patients with well-controlled BP, in a report of 2907 adults with hypertension participating in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. [ 56 , 57 ] Increasing severity of hypertensive retinopathy was associated with an increased risk of stroke; the stroke risk was 1.35 in the mild retinopathy group and 2.37 in the moderate/severe group.