The Defense Acquisition Encyclopedia

Program Management

A Business Case Analysis (BCA) is a document that provides a best-value analysis that considers not only cost but other quantifiable and non-quantifiable factors supporting an investment decision. A BCA should aid the decision maker in making an informed product support strategy decision. It should be tailored to inform the Program Manager of the costs, benefits, and risk implications of the strategic alternatives being considered. It should reflect the appropriate level of analysis needed to provide a fair assessment of the proposed alternatives. This analysis can include but is not limited to performance, producibility, reliability, maintainability, and supportability enhancements.

Definition: A Business Case Analysis (BCA) is a s a structured methodology and document that aids decision-making by identifying and comparing alternatives by examining the mission and business impacts (both financial and non-financial), risks, and sensitivities. It is a Program Management tool used to evaluate potential business decisions for best-value determinations.

Purpose of a Business Case Analysis (BCA)

The purpose of a BCA is to provide decision-makers with the appropriate information to assess whether or not to make a decision. A BCA is a valuable tool that assists in refining the myriad of decisions to determine the best value strategy. It follows an iterative process, conducted and updated as needed throughout the life cycle as program plans evolve and react to changes in the business and mission environment.

Why Use a Business Case Analysis (BCA)

A BCA is a powerful tool for two crucial reasons. The first is that the person making the report has to think about all the costs, risks, and benefits of making a choice. When making a choice, it’s easy to only think about what you want to happen instead of looking at every possible event. When people are pushed to think about the worst possible outcomes, they are likelier to make the right choice. The second reason to use business case analysis is that it makes it easy for a subject-matter expert to give useful information to stakeholders and put it in context. Without a full report from the expert, stakeholders might not realize how vital some costs, risks, or rewards are.

Business Case Analysis (BCA) Use

A Business Case Analysis is used for the following:

- Is used in the initial decision to invest in a project.

- Guides the decision to select among alternative approaches.

- Is used to validate any proposed scope, schedule, or budget changes during the course of the project.

- Should also be used to identify the various budget accounts and amounts affected by the various product support strategies.

- Should be a living document ‘ as project or organization changes occur they should be reflected in updates to the business case.

- Should be used to validate that planned benefits are realized at the completion of the project.

- Makes the team consider all of the costs, risks, and benefits of making a decision

Business Case Analysis (BCA) Report Content

As a minimum, a BCA should include:

- Executive Summary: An overview of the BCA

- Introduction: An introduction that defines what the case is about (the subject) and why (its purpose) it is necessary. The introduction presents the objectives addressed by the subject of the case.

- Methods and Assumptions: state the analysis methods and rationale that fixes the boundaries of the case (whose costs and benefits are examined over what time period). This section outlines the rules for deciding what belongs in the case and what does not, along with the important assumptions.

- Impacts: The business impacts are the financial and non-financial business impacts expected in one or more scenarios.

- Risk assessment: show how results depend on important assumptions (‘what if’) and the likelihood for other results to surface.

- Conclusions and Recommendations: specific actions based on business objectives and the analysis results.

Business Case Analysis (BCA) References

Guide: dod product support business case analysis (bca) guidebook – 28 feb 2014.

- Template: DoD Business Case Analysis

Performance-Based Logistics (PBL) BCA

DoD has promulgated the Guiding Principles for conducting a Performance-Based Logistics (PBL) BCA in USD(AT&L) Memorandum, Performance-Based Logistics (PBL) Business Case Analysis (BCA), 23 January 2004. OSD has issued guidance emphasizing the use of the Business Case Analysis as a fundamental tool to support PBL support strategic decisions.

Difference Between a Business Case and Business Case Analysis

They are the same regarding results, but a business case normally refers to the report, and business case analysis refers to the analysis.

AcqNotes Tutorial

Lessons Learned in Developing a Business Case Analysis (BCA)

As a program manager who needs to make a business case study for top management, there are a few essential things to remember. Here are some of the most important lessons:

- Know the Goals: Before you start the business case analysis, make sure you understand the company’s strategic goals and the proposed project’s specific goals. This will help you ensure your analysis aligns with the results you want and show senior leadership the possible value.

- Get people involved early: Include key partners from the start of the process to get their feedback and ensure their points of view are considered. Engaging partners early on builds support and helps find key success factors, possible risks, and other important factors that should be analyzed.

- Get enough information: Do a lot of studies and gather accurate information to back up your analysis. This includes financial data, market studies, customer feedback, and other useful information. Ensuring your data is correct and reliable will give your business case more weight.

- Clearly define assumptions: If you made any assumptions during the research, say so and explain them. Assumptions are a key part of making predictions and figuring out costs and rewards. Being open about your assumptions helps the people in charge understand your analysis and decide if it is true.

- List and measure the benefits: List and measure both the visible and invisible benefits of the planned project. Tangible benefits can be measured in terms of money, like how much they save, make, or improve efficiency. Some examples of intangible benefits are happier customers, a better image for the brand, and happier employees. Your business case will be stronger if you show all of the perks.

- Evaluate risks and ways to deal with them: Find and evaluate any possible risks with the project. Explain how likely risks will happen and how they might affect the company. Also, develop suitable mitigation strategies to show that you are taking a proactive approach to risk management and reduce the likelihood of bad things happening.

- Think about other options: Look into other solutions or ways of doing things and rate their viability and possible benefits. By comparing different options, senior leaders can make well-informed decisions and ensure that the planned initiative is the most effective and efficient way to meet organizational goals.

- Communicate clearly and briefly: Give your analysis in a clear, brief, and convincing way. Use visual guides, executive summaries, and other tools to help people understand your findings. Adjust the level of detail to your audience and focus on the key information senior leadership needs to make an informed choice.

- Be ready for questions: Think about what questions and worries senior leadership might have and be ready to answer them. Understand the business case analysis and the concepts it is based on so you can answer with confidence and knowledge. This shows your knowledge and builds your trustworthiness.

- Ask for feedback and keep making changes: After presenting the business case analysis, ask top leadership and other stakeholders for feedback. Learn what they think and what worries them. Use this feedback as a chance to keep getting better, to improve your analysis, and to add useful information to future business cases.

AcqLinks and References:

- DoD Product Support Business Case Analysis (BCA) Guidebook – 28 Feb 2014

Updated: 4/1/2024

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Strategy Templates

Consulting Templates

- Market Analysis Templates

- Business Case

- Consulting Proposal

- Due Diligence Report

All Templates

How to write a solid business case (with examples and template).

Table of contents

What is a business case, business case vs. business plan, how to structure your business case, how to write a business case.

- Business Case PowerPoint template

ROI calculator template

- Key elements of a strong Business Case

Frequently asked questions

Nearly every new project requires approval—whether it's getting the green light from your team or securing support from executive stakeholders. While an informal email might suffice for smaller initiatives, significant business investments often require a well-crafted business case. This guide, written by former consultants from McKinsey and Bain, will help you write a compelling business case. It provides the steps and best practices to secure the necessary support and resources for a successful project.

A business case is a written document (often a PowerPoint presentation) that articulates the value of a specific business project or investment. It presents the rationale for the project, including the benefits, costs, risks, and impact. The main objective is to persuade internal stakeholders to endorse the project.

A business case answers the questions:

- Why should we do this?

- What is the best solution?

- What will happen if we proceed with this investment decision?

Business cases can serve many purposes, but here are a few common reasons for developing one:

- Implementation of a new IT system

- Launching a new product line

- Construction of a new manufacturing plant or data center

- Opening new retail locations or expanding into international markets

- Implementation of new compliance and risk management systems

- Acquiring a competitor or a complementary business

- Investing in building a new capability

- Obtaining additional resources for an ongoing initiative

- Deciding whether to outsource a function

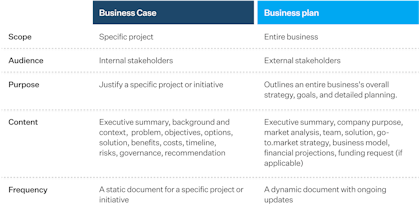

Simply put, a business case justifies a specific project or initiative, while a business plan outlines an entire business's overall strategy, goals, and detailed planning.

Investors use a business plan to make informed decisions about investing. It details the financial, strategic, and operational aspects of a business, helping investors assess the potential return on investment. In contrast, a business case is narrowly focused on a particular project or initiative. It helps stakeholders evaluate the potential impact of that specific project on the business. Both documents require thorough research, careful writing, and effective presentation. Here's an overview of their differences:

Before writing your business case

The fate of your project or initiative will usually lie with a small group of decision makers. The best way to increase your chances of getting a green light is to engage with stakeholders, gather their insights, and build support before writing the business case. Use their input to construct a rough draft and present this draft back to key stakeholders for feedback and approval. Only once you have understood their priorities and concerns should you proceed with writing the final business case.

To get buy-in from your stakeholders, you must tell your "story" so that it is easy to understand the need, the solution you're proposing, and the benefits to the company. Generally, decision-makers will care most about ROI and how your project aligns with the organization's strategic goals – so keep those issues front and center.

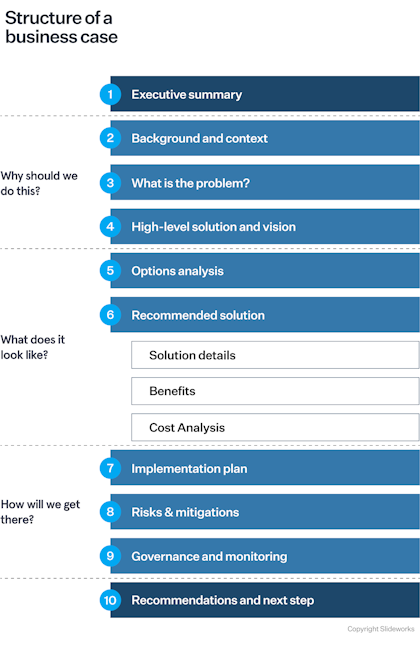

In our experience, the business case structure below is the most logical and effective, but you should generally use whatever format or template your company uses. If no templates exist, use the structure below and find a solid template (you'll find a link to a template later in this post).

Whatever structure or template you apply, remember that your story needs to be clear above all else.

Let's go through each of the 10 sections one-by-one:

1. Executive Summary

A one-page summary providing a concise overview of the business case.

Highlight the key points, including the problem or opportunity, proposed solution, and expected benefits.

We recommend structuring your summary using the Situation-Complication-Solution framework (See How to Write an Effective Executive Summary ) . The executive summary should be the final thing you write.

2. Background and context

Start with the why. Outline the situation and the business problem or opportunity your business case addresses. Clearly describe the problem's impact on the organization.

This section may include an overview of the macro environment and dynamics, key trends driving change, and potential threats or opportunities. Share data that conveys urgency . For example: Is customer satisfaction dropping because of a lack of product features? Is an outdated IT system causing delays in the sales process? Are you seeing growing competition from digital-first players in the market? Are you seeing an opportunity as a result of changing customer needs?

3. What is the problem?

This is a key part of your business case. Your business case is built from your analysis of the problem. If your stakeholders don't understand and agree with your articulation of the problem, they'll take issue with everything else in your business case.

Describe the underlying issues and their solutions using data. You might include customer data, input from end users, or other information from those most affected by the problem.

4. High-level solution and vision

Start with a high-level description of the solution. Clarify the specific, measurable objectives that the project aims to achieve. Ensure these objectives align with the organization's strategic goals.

5. Option analysis

You have now answered the question: Why should we do this project? - and you have outlined a compelling solution.

In this section, you identify and evaluate different options for addressing the problem. Include a "do nothing" option as a baseline for comparison. Assess the pros and cons of each option, considering factors like cost, feasibility, risk, and potential benefits.

See a more in-depth article on how to think about and present risks in our blog post " Mastering Risk Mitigation Slides: A Best Practice Guide with Examples ".

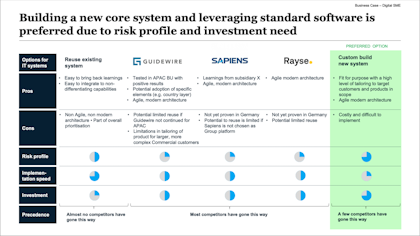

Slide summarizing various options for a new IT system. Example from Slideworks Business Case Template Slide

6. Recommended Solution

Solution Details Propose the preferred solution based on the options analysis. Describe the solution in detail, including scope, deliverables, and key components. Justify why this solution is the best choice.

Benefits Describe the benefits (e.g., cost savings, increased revenue, improved efficiency, competitive advantage). Include both tangible and intangible benefits, but focus on benefits you can quantify. Your stakeholders will want to know the financial impact.

Be very clear about where your numbers come from. Did you get them from colleagues in Marketing, Finance, HR, or Engineering? Stakeholders care about the sources for these assumptions and are more likely to trust your numbers if they come from (or are validated by) people they trust.

Cost Analysis In this section, you provide a detailed breakdown of the costs associated with the proposed solution. Include initial investment, ongoing operational costs, and any potential financial risks.

Compare the costs against the expected benefits to demonstrate return on investment (ROI).

7. Implementation plan

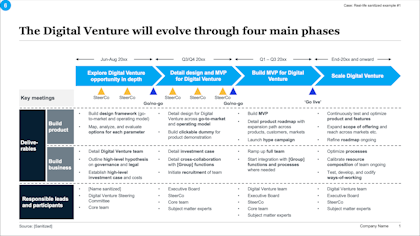

Outline a high-level plan for implementing the proposed solution . Include key milestones, timelines, and dependencies. Describe the resources required, including personnel, technology, and funding.

Roadmap example - New digital venture. Slideworks Business Case Template

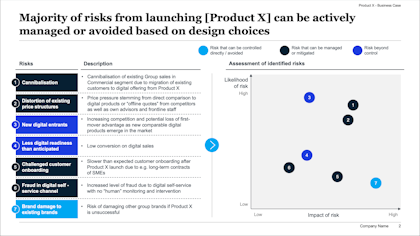

8. Risks and mitigations

In this section, you highlight potential risks and uncertainties associated with the project. Try to focus on the most important risks (you don't need to account for every potential scenario). These typically include those affecting cost, benefits, and schedule, but they can also include risks to the team, technology, scope, and performance.

Be realistic when you write this section. Transparency will gain the confidence of stakeholders and will demonstrate your foresight and capability.

Consider ranking your identified risk areas according to "likelihood of risk" and "impact of risk" (as shown in the example below). Then, propose mitigation strategies to manage and minimize risks.

Example of Risks Slide - Slideworks Business Case Template

Risks and mitigation slide - Slideworks Business Case Template

9. Governance and monitoring

Establishing a clear governance structure ensures that there is a defined hierarchy of authority, responsibilities, and accountability. A definition of the following groups and roles are often included:

- Steering Committee : A group of senior executives or stakeholders who provide overall strategic direction, make high-level decisions, and ensure that the project aligns with organizational goals.

- Project Sponsor : An individual or group with the authority to provide resources, make critical decisions, and support the project at the highest level. The sponsor is often a senior executive.

- Project Manager : The person responsible for day-to-day management of the project, ensuring that the project stays on track, within budget, and meets its objectives. The project manager reports to the steering committee and project sponsor.

- Project Team : A group of individuals with various skills and expertise necessary to carry out project tasks. The team may include internal staff and external consultants.

You might also define what monitoring and reporting mechanisms that will be used to track the project's progress, identify issues early, and ensure accountability. These mechanisms often include specific Project Management Tools, ongoing status reports, and meetings.

10. Recommendations and next steps

In this last section, you summarize the key points of the business case and make a final recommendation to the decision-makers . Remember to Include your ROI number(s) again and repeat how your project aligns with the organization's strategic goals.

Consider ending your business case with a final slide outlining the immediate actions required to move forward with the recommended solution.

Learn about how to fit in a business case in your commercial due diligence report in our article here .

Business Case PowerPoint template

An effective business case requires both the right content and structure. A strong template and a few best practice examples can ensure the right structure and speed up the process of designing individual slides.

The Slideworks Business Case Template for PowerPoint follows the methodology presented in this post and includes 300 PowerPoint slides, 3 Excel models, and three full-length, real-life case examples created by ex-McKinsey & BCG consultants.

Often, companies have a preferred method of calculating a project's ROI. If this is not the case, you should use the one most appropriate to your project—break-even analysis, payback period, NPV, or IRR.

Key elements of a strong Business Case

Involve subject-matter experts To develop a comprehensive business case, draw on insights from experts who understand the problem's intricacies and potential solutions. Involve colleagues from relevant departments such as R&D, sales, marketing, and finance to ensure all perspectives are considered.

Involve key stakeholders Get input from all relevant team members, including HR, finance, sales, and IT. This collaborative approach ensures the business case is built on verified expert knowledge. Encouraging teamwork and buy-in from internal stakeholders helps build a strong foundation of support.

Understand audience objectives Align your business case with the company’s strategic objectives and future plans. Clearly demonstrate how the project supports long-term company success. Consider the competition for resources and justify the investment by showing its relevance and importance.

Set a clear vision Communicate the purpose, goals, methods, and people involved in the initiative clearly. Detail what the project aims to solve or achieve and its impact on the organization. This clarity helps stakeholders understand the overall vision and direction of the project.

Be on point Be concise and provide only the necessary information needed for informed decision-making. Base your details on facts collected from team members and experts, avoiding assumptions. This precision ensures your business case is credible and actionable.

Check out our Go-To-Market Strategy post to take the next step on bringing your business idea to life.

What is the difference between a project business case and a project charter?

A project charter and a business case are distinct but complementary documents. The business case is created first and serves to justify the project's initiation by detailing its benefits, costs, risks, and alignment with organizational goals. It is used by decision-makers to approve or reject the project.

Once the project is approved, a project charter is often developed to formally authorize the project, outlining its objectives, scope, key stakeholders, and the project manager's authority. A summary of the business case is often included in the project charter.

How long should a business case be?

A comprehensive business case doesn't have a specific page count but should be detailed enough to clearly communicate the project's benefits, costs, risks, and alignment with organizational goals. For small projects, it may be a few pages; for larger or complex projects, it typically ranges from 10-20 word pages (30-50 slides), excluding appendices. Sources: Harvard Business Press - Developing a Business Case

Download our most popular templates

High-end PowerPoint templates and toolkits created by ex-McKinsey, BCG, and Bain consultants

Create a full business case incl. strategy, roadmap, financials and more.

- Market Analysis

Create a full market analysis report to effectively turn your market research into strategic insights

- Market Entry Analysis

Create a best-practice, well-structured market study for evaluating and comparing multiple markets.

Related articles

How to write a Next Steps slide (with Examples and Free Template)

In this blog post, we’ll dive into the Next Steps slide, why it’s important, and how to write one. We’ll also provide you with examples of Next Steps slides from McKinsey, BCG, and Bain, as well as a free template for you to create your own Next Steps slide.

Nov 1, 2024

Picking apart a McKinsey consulting proposal

In this blog post, we’ll break down a McKinsey consulting proposal, look at what works and why, and discuss how to write a winning consulting proposal.

Oct 12, 2024

20 PowerPoint shortcuts every consultant must know

We surveyed a group of top-tier consultants and identified their top PowerPoint shortcuts. This post explains how to use them efficiently.

Sep 23, 2024

- Consulting Toolkit

- Business Strategy

- Consulting Maps Bundle

- Mergers & Acquisitions

- Digital Transformation

- Product Strategy

- Go-To-Market Strategy

- Operational Excellence I

- Operational Excellence II

- Operational Excellence III

- Full Access Bundle

- Consulting PowerPoint Templates

- How it works

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

© 2024 Slideworks. All rights reserved

Denmark : Farvergade 10 4. 1463 Copenhagen K

US : 101 Avenue of the Americas, 9th Floor 10013, New York

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Creating Brand Value

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurial Marketing

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

5 Benefits of Learning Through the Case Study Method

- 28 Nov 2023

While several factors make HBS Online unique —including a global Community and real-world outcomes —active learning through the case study method rises to the top.

In a 2023 City Square Associates survey, 74 percent of HBS Online learners who also took a course from another provider said HBS Online’s case method and real-world examples were better by comparison.

Here’s a primer on the case method, five benefits you could gain, and how to experience it for yourself.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is the Harvard Business School Case Study Method?

The case study method , or case method , is a learning technique in which you’re presented with a real-world business challenge and asked how you’d solve it. After working through it yourself and with peers, you’re told how the scenario played out.

HBS pioneered the case method in 1922. Shortly before, in 1921, the first case was written.

“How do you go into an ambiguous situation and get to the bottom of it?” says HBS Professor Jan Rivkin, former senior associate dean and chair of HBS's master of business administration (MBA) program, in a video about the case method . “That skill—the skill of figuring out a course of inquiry to choose a course of action—that skill is as relevant today as it was in 1921.”

Originally developed for the in-person MBA classroom, HBS Online adapted the case method into an engaging, interactive online learning experience in 2014.

In HBS Online courses , you learn about each case from the business professional who experienced it. After reviewing their videos, you’re prompted to take their perspective and explain how you’d handle their situation.

You then get to read peers’ responses, “star” them, and comment to further the discussion. Afterward, you learn how the professional handled it and their key takeaways.

Learn more about HBS Online's approach to the case method in the video below, and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more.

HBS Online’s adaptation of the case method incorporates the famed HBS “cold call,” in which you’re called on at random to make a decision without time to prepare.

“Learning came to life!” said Sheneka Balogun , chief administration officer and chief of staff at LeMoyne-Owen College, of her experience taking the Credential of Readiness (CORe) program . “The videos from the professors, the interactive cold calls where you were randomly selected to participate, and the case studies that enhanced and often captured the essence of objectives and learning goals were all embedded in each module. This made learning fun, engaging, and student-friendly.”

If you’re considering taking a course that leverages the case study method, here are five benefits you could experience.

5 Benefits of Learning Through Case Studies

1. take new perspectives.

The case method prompts you to consider a scenario from another person’s perspective. To work through the situation and come up with a solution, you must consider their circumstances, limitations, risk tolerance, stakeholders, resources, and potential consequences to assess how to respond.

Taking on new perspectives not only can help you navigate your own challenges but also others’. Putting yourself in someone else’s situation to understand their motivations and needs can go a long way when collaborating with stakeholders.

2. Hone Your Decision-Making Skills

Another skill you can build is the ability to make decisions effectively . The case study method forces you to use limited information to decide how to handle a problem—just like in the real world.

Throughout your career, you’ll need to make difficult decisions with incomplete or imperfect information—and sometimes, you won’t feel qualified to do so. Learning through the case method allows you to practice this skill in a low-stakes environment. When facing a real challenge, you’ll be better prepared to think quickly, collaborate with others, and present and defend your solution.

3. Become More Open-Minded

As you collaborate with peers on responses, it becomes clear that not everyone solves problems the same way. Exposing yourself to various approaches and perspectives can help you become a more open-minded professional.

When you’re part of a diverse group of learners from around the world, your experiences, cultures, and backgrounds contribute to a range of opinions on each case.

On the HBS Online course platform, you’re prompted to view and comment on others’ responses, and discussion is encouraged. This practice of considering others’ perspectives can make you more receptive in your career.

“You’d be surprised at how much you can learn from your peers,” said Ratnaditya Jonnalagadda , a software engineer who took CORe.

In addition to interacting with peers in the course platform, Jonnalagadda was part of the HBS Online Community , where he networked with other professionals and continued discussions sparked by course content.

“You get to understand your peers better, and students share examples of businesses implementing a concept from a module you just learned,” Jonnalagadda said. “It’s a very good way to cement the concepts in one's mind.”

4. Enhance Your Curiosity

One byproduct of taking on different perspectives is that it enables you to picture yourself in various roles, industries, and business functions.

“Each case offers an opportunity for students to see what resonates with them, what excites them, what bores them, which role they could imagine inhabiting in their careers,” says former HBS Dean Nitin Nohria in the Harvard Business Review . “Cases stimulate curiosity about the range of opportunities in the world and the many ways that students can make a difference as leaders.”

Through the case method, you can “try on” roles you may not have considered and feel more prepared to change or advance your career .

5. Build Your Self-Confidence

Finally, learning through the case study method can build your confidence. Each time you assume a business leader’s perspective, aim to solve a new challenge, and express and defend your opinions and decisions to peers, you prepare to do the same in your career.

According to a 2022 City Square Associates survey , 84 percent of HBS Online learners report feeling more confident making business decisions after taking a course.

“Self-confidence is difficult to teach or coach, but the case study method seems to instill it in people,” Nohria says in the Harvard Business Review . “There may well be other ways of learning these meta-skills, such as the repeated experience gained through practice or guidance from a gifted coach. However, under the direction of a masterful teacher, the case method can engage students and help them develop powerful meta-skills like no other form of teaching.”

How to Experience the Case Study Method

If the case method seems like a good fit for your learning style, experience it for yourself by taking an HBS Online course. Offerings span eight subject areas, including:

- Business essentials

- Leadership and management

- Entrepreneurship and innovation

- Digital transformation

- Finance and accounting

- Business in society

No matter which course or credential program you choose, you’ll examine case studies from real business professionals, work through their challenges alongside peers, and gain valuable insights to apply to your career.

Are you interested in discovering how HBS Online can help advance your career? Explore our course catalog and download our free guide —complete with interactive workbook sections—to determine if online learning is right for you and which course to take.

About the Author

- What is PESTLE Analysis?

- Entrepreneurs

- Permissions

- Privacy Policy

What Is Business Case Analysis (BCA)?

Business case analysis is a decision-making tool. Find out why and when to use business case analysis in the corporate world.

Business case analysis is a tool used to evaluate potential business decisions. It's often used in the corporate world where project managers and other front-line employees need to convince company stakeholders for their support. The project manager , who is responsible for conducting the analysis, assesses the costs, risks, and benefits of a decision using their specialist knowledge. Then, company stakeholders review the analysis (in the form of a report) to determine whether or not they should approve the decision.

This valuable business analysis tool may sound daunting, but is surprisingly easy to use. In this article, we'll walk you through the basics of business case analysis, discussing its key features, potential uses, and much more.

Key Features of Business Case Analysis

The basic purpose of a business case analysis is to assess a decision or action. In business terms, the most important criteria for this purpose are costs, risks, and benefits. In other words, a business case analysis report should answer three basic questions:

- Costs: What are the costs of making this decision?

- Risks: What are the risks of making this decision?

- Benefits: What are the expected benefits of making this decision?

Ultimately, the goal of answering these questions is to assess whether or not to make the decision. If the expected benefits of the decision significantly outweigh the costs and risks, the decision should be made. If, however, the costs and risks outweigh the benefits, an alternative should be considered.

Business case analysis usually has a financial focus, whereby costs, risks, and benefits are compared in dollar terms. However, business case analysis can also use other quantitative or qualitative lenses . For example, the costs of a decision might be measured in time (instead of dollars). Similarly, the risks or benefits of a decision might be measured in changes to brand value, customer satisfaction, or even legal status. When business case analysis does not focus on financial impacts, it's important to look for objective ways to compare these upsides and downsides, so that stakeholders can make an informed choice.

Business Case Analysis vs Business Case

You may be wondering what the difference is between a business case analysis and a business case. The truth is that both of these terms refer to the same business analysis tool . The difference is that business case usually refers to the report itself, whereas business case analysis refers to the overall approach to analysis.

Why Use Business Case Analysis

There are two powerful reasons to use business case analysis. The first is that it forces the individual creating the report to consider all of the costs, risks, and benefits of making a decision. When making a decision, it's easy to focus on the desired results instead of realistically evaluating every possible outcome. When forced to think about exceptional or undesired outcomes, there's a greater chance the correct decision will be made.

The second reason to use business case analysis is that it allows a subject-matter expert (in most cases, the product manager) to easily transfer and contextualize relevant knowledge to stakeholders. Without a comprehensive report from the expert, stakeholders may not see the significance of certain costs, risks, or benefits.

When to Use Business Case Analysis

Business case analysis is most often used in large companies where the project manager needs approval from stakeholders. In small and medium-sized companies, the project manager is usually the primary stakeholder, so there is no need for external approval.

With that said, it can still be beneficial to conduct business case analysis even in smaller companies. This is because it forces the decision-maker to consider all possibilities, as mentioned above.

Business Case Analysis for Comparing Actions

So far, we've discussed using business case analysis to evaluate a single decision. However, business case analysis can also be an extremely effective way to compare two or more courses of action. Once again, this is partially because conducting business case analysis forces you to consider a number of possibilities. While two courses of action may have the same expected benefits, they may have different risks or costs, making it much easier to decide which one to pursue.

Structuring Your Business Case

Like most types of business analysis , business case analysis is usually presented in the form of a written report (the business case). While there are no set rules for this kind of report, here is a simple structure that includes the basic elements:

- Executive Summary: Like other corporate reports, a business case analysis report should begin with an executive summary. This section should summarize the results of the analysis and give appropriate recommendations regarding the decision in question.

- Introduction: The main purpose of the introduction is to provide context for the report. It should discuss what is being analyzed and why (in other words, the objectives of the analysis)

- Methods (Optional): Optionally, the report can include a section discussing methodology. If included, this section should discuss the approaches used to analyze the potential outcomes of the decision.

- Expected Outcomes: A crucial part of the report is the outcomes section. This section should discuss the expected outcomes — in particular, costs and benefits — of the business decision.

- Risk Assessment: Similarly important is the risk assessment section . Here, the report should discuss potential negative outcomes that may result if certain assumptions (leading to the expected outcomes) are not met.

- Conclusion: The report should close with a conclusion. This section should summarize the findings of the report and provide appropriate recommendations with those findings in mind.

Final Thoughts

Business case analysis is a decision-making tool whereby reports — called business cases — are created to discuss the costs, risks, and benefits of a given decision. Often employed in large companies, this type of analysis allows for knowledgeable project managers to evaluate decisions in a way that stakeholders can understand.

The business case itself should include an executive summary, introduction, expected outcomes, risks, and a conclusion. It may also include other sections, such as methodology. Most important, however, is an objective analysis of the positive and negative outcomes of the decision itself.

Image by rawpixel

Internal Factors That Affect a Business or Organization

SWOT Analysis of Artificial Intelligence

Learn to convert linkedin cold messages using these 14 proven prospecting messages.

What the Case Study Method Really Teaches

by Nitin Nohria

Summary .

During my decade as dean of Harvard Business School, I spent hundreds of hours talking with our alumni. To enliven these conversations, I relied on a favorite question: “What was the most important thing you learned from your time in our MBA program?”

Partner Center

What is the Case Study Method?

Simply put, the case method is a discussion of real-life situations that business executives have faced.

On average, you'll attend three to four different classes a day, for a total of about six hours of class time (schedules vary). To prepare, you'll work through problems with your peers.

How the Case Method Creates Value

Often, executives are surprised to discover that the objective of the case study is not to reach consensus, but to understand how different people use the same information to arrive at diverse conclusions. When you begin to understand the context, you can appreciate the reasons why those decisions were made. You can prepare for case discussions in several ways.

Case Discussion Preparation Details

In self-reflection.

The time you spend here is deeply introspective. You're not only working with case materials and assignments, but also taking on the role of the case protagonist—the person who's supposed to make those tough decisions. How would you react in those situations? We put people in a variety of contexts, and they start by addressing that specific problem.

In a small group setting

The discussion group is a critical component of the HBS experience. You're working in close quarters with a group of seven or eight very accomplished peers in diverse functions, industries, and geographies. Because they bring unique experience to play you begin to see that there are many different ways to wrestle with a problem—and that’s very enriching.

In the classroom

The faculty guides you in examining and resolving the issues—but the beauty here is that they don't provide you with the answers. You're interacting in the classroom with other executives—debating the issue, presenting new viewpoints, countering positions, and building on one another's ideas. And that leads to the next stage of learning.

Beyond the classroom

Once you leave the classroom, the learning continues and amplifies as you get to know people in different settings—over meals, at social gatherings, in the fitness center, or as you are walking to class. You begin to distill the takeaways that you want to bring back and apply in your organization to ensure that the decisions you make will create more value for your firm.

How Cases Unfold In the Classroom

Pioneered by HBS faculty, the case method puts you in the role of the chief decision maker as you explore the challenges facing leading companies across the globe. Learning to think fast on your feet with limited information sharpens your analytical skills and empowers you to make critical decisions in real time.

To get the most out of each case, it's important to read and reflect, and then meet with your discussion group to share your insights. You and your peers will explore the underlying issues, compare alternatives, and suggest various ways of resolving the problem.

How to Prepare for Case Discussions

There's more than one way to prepare for a case discussion, but these general guidelines can help you develop a method that works for you.

Preparation Guidelines

Read the professor's assignment or discussion questions.

The assignment and discussion questions help you focus on the key aspects of the case. Ask yourself: What are the most important issues being raised?

Read the first few paragraphs and then skim the case

Each case begins with a text description followed by exhibits. Ask yourself: What is the case generally about, and what information do I need to analyze?

Reread the case, underline text, and make margin notes

Put yourself in the shoes of the case protagonist, and own that person's problems. Ask yourself: What basic problem is this executive trying to resolve?

Note the key problems on a pad of paper and go through the case again

Sort out relevant considerations and do the quantitative or qualitative analysis. Ask yourself: What recommendations should I make based on my case data analysis?

Case Study Best Practices

The key to being an active listener and participant in case discussions—and to getting the most out of the learning experience—is thorough individual preparation.

We've set aside formal time for you to discuss the case with your group. These sessions will help you to become more confident about sharing your views in the classroom discussion.

Participate

Actively express your views and challenge others. Don't be afraid to share related "war stories" that will heighten the relevance and enrich the discussion.

If the content doesn't seem to relate to your business, don't tune out. You can learn a lot about marketing insurance from a case on marketing razor blades!

Actively apply what you're learning to your own specific management situations, both past and future. This will magnify the relevance to your business.

People with diverse backgrounds, experiences, skills, and styles will take away different things. Be sure to note what resonates with you, not your peers.

Being exposed to so many different approaches to a given situation will put you in a better position to enhance your management style.

Frequently Asked Questions

What can i expect on the first day, what happens in class if nobody talks, does everyone take part in "role-playing".

- Contact sales

Start free trial

How to Write a Business Case (Template Included)

Table of Contents

What is a business case, business case template, how to write a business case, key elements of a business case, how projectmanager helps with your business case, watch our business case training video.

A business case is a project management document that explains how the benefits of a project outweigh its costs and why it should be executed. Business cases are prepared during the project initiation phase and their purpose is to include all the project’s objectives, costs and benefits to convince stakeholders of its value.

A business case is an important project document to prove to your client, customer or stakeholder that the project proposal you’re pitching is a sound investment. Below, we illustrate the steps to writing one that will sway them.

The need for a business case is that it collects the financial appraisal, proposal, strategy and marketing plan in one document and offers a full look at how the project will benefit the organization. Once your business case is approved by the project stakeholders, you can begin the project planning phase.

When Should You Write a Business Case?

Around 70 percent of businesses that survive longer than five years follow a strategic business plan. And every project an organization undertakes should demonstrate real business value via a business case. A business case is created during the initiation phase of a project. At this point, the project is being conceptualized and evaluated on what the potential return on investment could be. The business case document helps determine the project’s needs and allows decision-makers to determine if the project aligns with the organization’s strategic goals.

For example, a business case may be used when there’s a new project proposal, when entering into a new market, when upgrading software solutions or when there’s a major capital expenditure. Once the business case has been approved, the project will move to the planning phase.

Why Is It Important to Write a Business Case Document?

A business case document benefits projects for several reasons.

- Justifies why a project is needed, outlining costs, benefits and risks

- Engages stakeholders and gets their buy-in and support

- Allows decision-makers to assess feasibility and make choices based on data

- Provides estimates for costs, resources and timelines to improve resource allocation

- Helps hold teams accountable for delivering on commitments

Overall, it helps guide the project initiation and execution to result in thoughtful and strategic decisions.

Our business case template for Word is the perfect tool to start writing a business case. It has 9 key business case areas you can customize as needed. Download the template for free and follow the steps below to create a great business case for all your projects.

Projects fail without having a solid business case to rest on, as this project document is the base for the project charter and project plan. But if a project business case is not anchored to reality, and doesn’t address a need that aligns with the larger business objectives of the organization, then it is irrelevant.

The research you’ll need to create a strong business case is the why, what, how and who of your project. This must be clearly communicated. The elements of your business case will address the why but in greater detail. Think of the business case as a document that is created during the project initiation phase but will be used as a reference throughout the project life cycle.

Whether you’re starting a new project or mid-way through one, take time to write up a business case to justify the project expenditure by identifying the business benefits your project will deliver and that your stakeholders are most interested in reaping from the work. The following four steps will show you how to write a business case.

Step 1: Identify the Business Problem

Projects aren’t created for projects’ sake. They should always be aligned with business goals . Usually, they’re initiated to solve a specific business problem or create a business opportunity.

You should “Lead with the need.” Your first job is to figure out what that problem or opportunity is, describe it, find out where it comes from and then address the time frame needed to deal with it.

This can be a simple statement but is best articulated with some research into the economic climate and the competitive landscape to justify the timing of the project.

Step 2: Identify the Alternative Solutions

How do you know whether the project you’re undertaking is the best possible solution to the problem defined above? Naturally, prioritizing projects is hard, and the path to success is not paved with unfounded assumptions.

One way to narrow down the focus to make the right solution clear is to follow these six steps (after the relevant research, of course):

- Note the alternative solutions.

- For each solution, quantify its benefits.

- Also, forecast the costs involved in each solution.

- Then figure out its feasibility .

- Discern the risks and issues associated with each solution.

- Finally, document all this in your business case.

Step 3: Recommend a Preferred Solution

You’ll next need to rank the solutions, but before doing that it’s best to set up criteria, maybe have a scoring mechanism such as a decision matrix to help you prioritize the solutions to best choose the right one.

Some methodologies you can apply include:

- Depending on the solution’s cost and benefit , give it a score of 1-10.

- Base your score on what’s important to you.

- Add more complexity to your ranking to cover all bases.

Regardless of your approach, once you’ve added up your numbers, the best solution to your problem will become evident. Again, you’ll want to have this process also documented in your business case.

Get your free

Use this free Business Case Template for Word to manage your projects better.

Step 4: Describe the Implementation Approach

So, you’ve identified your business problem or opportunity and how to reach it, now you have to convince your stakeholders that you’re right and have the best way to implement a process to achieve your goals. That’s why documentation is so important; it offers a practical path to solve the core problem you identified.

Now, it’s not just an exercise to appease senior leadership. Who knows what you might uncover in the research you put into exploring the underlying problem and determining alternative solutions? You might save the organization millions with an alternate solution than the one initially proposed. When you put in the work on a strong business case, you’re able to get your sponsors or organizational leadership on board with you and have a clear vision as to how to ensure the delivery of the business benefits they expect.

One of the key steps to starting a business case is to have a business case checklist. The following is a detailed outline to follow when developing your business case. You can choose which of these elements are the most relevant to your project stakeholders and add them to our business case template. Then once your business case is approved, start managing your projects with a robust project management software such as ProjectManager.

1. Executive Summary

The executive summary is a short version of each section of your business case. It’s used to give stakeholders a quick overview of your project to help them understand the project’s purpose, benefits and implications. Some components of an executive summary include the project overview, business need, proposed solution to the need, cost estimate, return on investment, risks, timeline and a call to action.

2. Project Definition

This section is meant to provide general information about your projects, such as the business objectives that will be achieved and the project plan outline. It offers a comprehensive overview of the project including its objectives and scope. Here, include details such as the objectives, stakeholders, scope, expected outcomes and constraints.

3. Vision, Goals and Objectives

First, you have to figure out what you’re trying to do and what is the problem you want to solve. You’ll need to define your project vision, goals and objectives. This will help you shape your project scope and identify project deliverables.

4. Project Scope

The project scope determines all the tasks and deliverables that will be executed in your project to reach your business objectives. Think of it as establishing the project’s boundaries to help stakeholders better understand what to expect. A well-defined scope can also improve resource allocation and project planning, two key factors of the project’s long-term success.

5. Background Information

Here you can provide a context for your project, explaining the problem that it’s meant to solve, and how it aligns with your organization’s vision and strategic plan.

6. Success Criteria and Stakeholder Requirements

Depending on what kind of project you’re working on, the quality requirements will differ, but they are critical to the project’s success. Collect all of them, figure out what determines if you’ve successfully met them and report on the results .

7. Project Plan

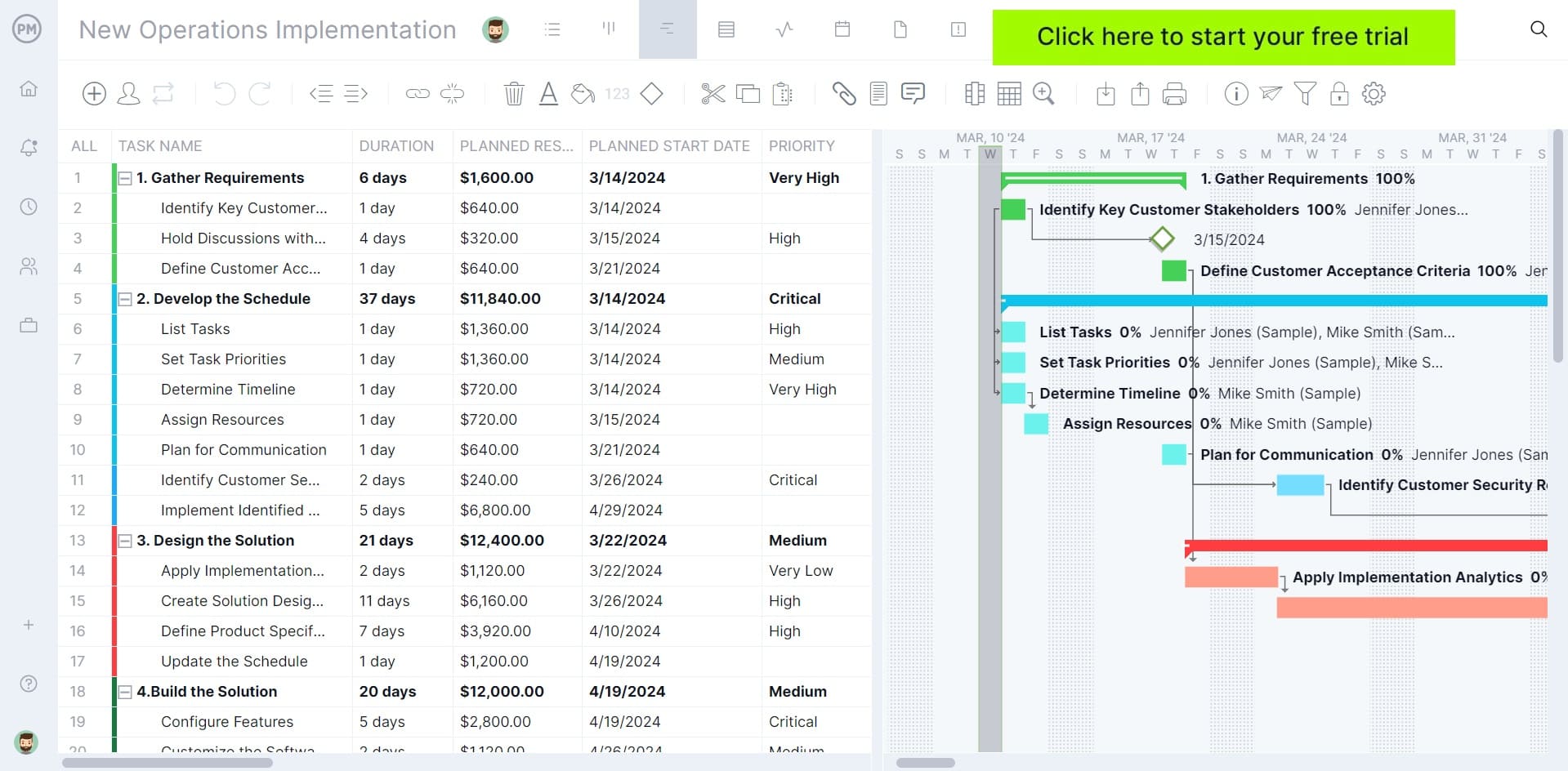

It’s time to create the project plan. Figure out the tasks you’ll have to take to get the project done. You can use a work breakdown structure template to make sure you are through. Once you have all the tasks collected, estimate how long it will take to complete each one.

Project management software makes creating a project plan significantly easier. ProjectManager can upload your work breakdown structure template and all your tasks are populated in our tool. You can organize them according to your production cycle with our kanban board view, or use our Gantt chart view to create a project schedule.

8. Project Budget

Your budget is an estimate of everything in your project plan and what it will cost to complete the project over the scheduled time allotted. It outlines the financial resources such as personnel costs, software or hardware costs, consulting fees, training costs and contingency funds. It also provides the return on investment information and shows how the benefits will outweigh the costs.

9. Project Schedule

Make a timeline for the project by estimating how long it will take to get each task completed. For a more impactful project schedule , use a tool to make a Gantt chart, and print it out. This will provide that extra flourish of data visualization and skill that Excel sheets lack.

10. Project Governance

Project governance refers to all the project management rules and procedures that apply to your project. For example, it defines the roles and responsibilities of the project team members and the framework for decision-making.

11. Communication Plan

Have milestones for check-ins and status updates, as well as determine how stakeholders will stay aware of the progress over the project life cycle. The communication plan can help foster an atmosphere of transparency and engagement among stakeholders. The plan outlines how, when and what will be communicated so that everyone is informed and on the same page.

12. Progress Reports

Have a plan in place to monitor and track your progress during the project to compare planned to actual progress. There are project tracking tools that can help you monitor progress and performance.

Again, using a project management tool improves your ability to see what’s happening in your project. ProjectManager has tracking tools like dashboards and status reports that give you a high-level view and more detail, respectively. Unlike light-weight apps that make you set up a dashboard, ours is embedded in the tool. Better still, our cloud-based software gives you real-time data for more insightful decision-making. Also, get reports on more than just status updates, but timesheets, workload, portfolio status and much more, all with just one click. Then filter the reports and share them with stakeholders to keep them updated.

13. Financial Appraisal

This is a very important section of your business case because this is where you explain how the financial benefits outweigh the project costs . Compare the financial costs and benefits of your project. You can do this by doing a sensitivity analysis and a cost-benefit analysis.

14. Market Assessment

Research your market, competitors and industry, to find opportunities and threats. The market assessment can also help outline the overall market condition and how that could impact the project. For example, what are the current market needs and trends? Are there any barriers to entry that could impact the project such as strong competition or high capital requirements? Note all of this information in this section of the business case.

15. Competitor Analysis

Identify direct and indirect competitors and do an assessment of their products, strengths, competitive advantages and their business strategy. For example, how does each competitor position itself in the market? What pricing strategy do they implement and where is there room for differentiation? Then, use this information to help guide future decisions.

16. SWOT Analysis

A SWOT analysis helps you identify your organization’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. The strengths and weaknesses are internal, while the opportunities and threats are external. This is a structured approach to help stakeholders make more informed decisions and outlines how to better leverage internal and external resources. The SWOT analysis helps ensure that the project aligns with organizational goals and market conditions.

17. Marketing Strategy

Describe your product, distribution channels, pricing, target customers among other aspects of your marketing plan or strategy.

18. Risk Assessment

There are many risk categories that can impact your project. The first step to mitigating them is to identify and analyze the risks associated with your project activities. From there, you can assess the likelihood and impact of each and rank them based on this information. The risk assessment makes it easier to focus on the most pressing risks and includes a mitigation strategy to reduce the impact in case the risk comes to fruition.

ProjectManager , an award-winning project management software, can collect and assemble all the various data you’ll be collecting, and then easily share it both with your team and project sponsors.

Once you have a spreadsheet with all your tasks listed, you can import it into our software. Then it’s instantly populated into a Gantt chart . Simply set the duration for each of the tasks, add any dependencies, and your project is now spread across a timeline. You can set milestones, but there is so much more you can do.

You have a project plan now, and from the online Gantt chart, you can assign team members to tasks. Then they can comment directly on the tasks they’re working on, adding as many documents and images as needed, fostering a collaborative environment. You can track their progress and change task durations as needed by dragging and dropping the start and end dates.

But that’s only a taste of what ProjectManager offers. We have kanban boards that visualize your workflow and a real-time dashboard that tracks six project metrics for the most accurate view of your project possible.

Try ProjectManager and see for yourself with this 30-day free trial .

If you want more business case advice, take a moment to watch Jennifer Bridges, PMP, in this short training video. She explains the steps you have to take in order to write a good business case.

Here’s a screenshot for your reference.

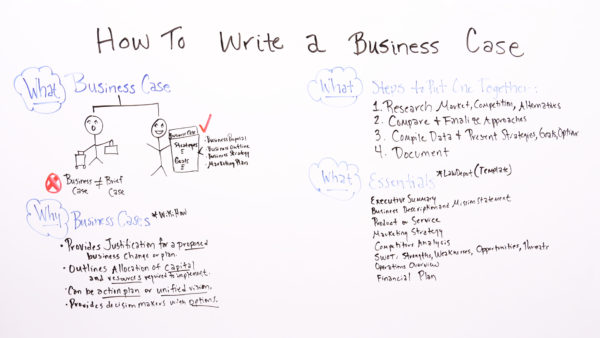

Transcription:

Today we’re talking about how to write a business case. Well, over the past few years, we’ve seen the market, or maybe organizations, companies or even projects, move away from doing business cases. But, these days, companies, organizations, and those same projects are scrutinizing the investments and they’re really seeking a rate of return.

So now, think of the business case as your opportunity to package your project, your idea, your opportunity, and show what it means and what the benefits are and how other people can benefit.

We want to take a look today to see what’s in the business case and how to write one. I want to be clear that when you look for information on a business case, it’s not a briefcase.

Someone called the other day and they were confused because they were looking for something, and they kept pulling up briefcases. That’s not what we’re talking about today. What we’re talking about are business cases, and they include information about your strategies, about your goals. It is your business proposal. It has your business outline, your business strategy, and even your marketing plan.

Why Do You Need a Business Case?

And so, why is that so important today? Again, companies are seeking not only their project managers but their team members to have a better understanding of business and more of an idea business acumen. So this business case provides the justification for the proposed business change or plan. It outlines the allocation of capital that you may be seeking and the resources required to implement it. Then, it can be an action plan . It may just serve as a unified vision. And then it also provides the decision-makers with different options.

So let’s look more at the steps required to put these business cases together. There are four main steps. One, you want to research your market. Really look at what’s out there, where are the needs, where are the gaps that you can serve? Look at your competition. How are they approaching this, and how can you maybe provide some other alternatives?

You want to compare and finalize different approaches that you can use to go to market. Then you compile that data and you present strategies, your goals and other options to be considered.

And then you literally document it.

So what does the document look like? Well, there are templates out there today. The components vary, but these are the common ones. And then these are what I consider essential. So there’s the executive summary. This is just a summary of your company, what your management team may look like, a summary of your product and service and your market.

The business description gives a little bit more history about your company and the mission statement and really what your company is about and how this product or service fits in.

Then, you outline the details of the product or service that you’re looking to either expand or roll out or implement. You may even include in their patents may be that you have pending or other trademarks.

Then, you want to identify and lay out your marketing strategy. Like, how are you gonna take this to your customers? Are you going to have a brick-and-mortar store? Are you gonna do this online? And, what are your plans to take it to market?

You also want to include detailed information about your competitor analysis. How are they doing things? And, how are you planning on, I guess, beating your competition?

You also want to look at and identify your SWOT. And the SWOT is your strength. What are the strengths that you have in going to market? And where are the weaknesses? Maybe some of your gaps. And further, where are your opportunities and maybe threats that you need to plan for? Then the overview of the operation includes operational information like your production, even human resources, information about the day-to-day operations of your company.

And then, your financial plan includes your profit statement, your profit and loss, any of your financials, any collateral that you may have, and any kind of investments that you may be seeking.

Related Project Planning Content

- Project Documentation: 15 Essential Project Documents

- How to Create a Project Execution Plan (PEP)

- How to Write a Scope of Work

So these are the components of your business case. This is why it’s so important. And if you need a tool that can help you manage and track this process, then sign up for our software now at ProjectManager .

Deliver your projects on time and on budget

Start planning your projects.

- Harvard Business School →

- Christensen Center →

Teaching by the Case Method

- Preparing to Teach

- Leading in the Classroom

- Providing Assessment & Feedback

- Sample Class

Case Method in Practice

Chris Christensen described case method teaching as "the art of managing uncertainty"—a process in which the instructor serves as "planner, host, moderator, devil's advocate, fellow-student, and judge," all in search of solutions to real-world problems and challenges.

Unlike lectures, case method classes unfold without a detailed script. Successful instructors simultaneously manage content and process, and they must prepare rigorously for both. Case method teachers learn to balance planning and spontaneity. In practice, they pursue opportunities and "teachable moments" that emerge throughout the discussion, and deftly guide students toward discovery and learning on multiple levels. The principles and techniques are developed, Christensen says, "through collaboration and cooperation with friends and colleagues, and through self-observation and reflection."

This section of the Christensen Center website explores the Case Method in Practice along the following dimensions:

- Providing Assessment and Feedback

Each subsection provides perspectives and guidance through a written overview, supplemented by video commentary from experienced case method instructors. Where relevant, links are included to downloadable documents produced by the Christensen Center or Harvard Business School Publishing. References for further reading are provided as well.

An additional subsection, entitled Resources, appears at the end. It combines references from throughout the Case Method in Practice section with additional information on published materials and websites that may be of interest to prospective, new, and experienced case method instructors.

Note: We would like to thank Harvard Business School Publishing for permission to incorporate the video clips that appear in the Case Method in Practice section of our website. The clips are drawn from video excerpts included in Participant-Centered Learning and the Case Method: A DVD Case Teaching Tool (HBSP, 2003).

Christensen Center Tip Sheets

- Characteristics of Effective Case Method Teaching

- Elements of Effective Class Preparation

- Guidelines for Effective Observation of Case Instructors

- In-Class Assessment of Discussion-Based Teaching

- Questions for Class Discussions

- Teaching Quantitative Material

- Strategies and Tactics for Sensitive Topics

Curriculum Innovation

The case method has evolved so students may act as decision-makers in new engaging formats:

Game Simulations

Multimedia cases, ideo: human-centered service design.

- > Master in Management (MiM)

- > Master in Research in Management (MRM)

- > PhD in Management

- > Executive MBA

- > Global Executive MBA

- > Executives

- > Organizations

- > Founders (School of Founders)

- > Certificate in AI & Digital Transformation

- > Programa de Desarrollo Directivo Flexible (PDD Flex)

- > Sustainability & ESG

- CHOOSE YOUR MBA

- IESE PORTFOLIO

- PROGRAM FINDER

- > Faculty Directory

- > Academic Departments

- > Initiatives

- > Competitive Projects

- > Academic Events

- > Behavioral Lab

- > Limitless Learning

- > Learning Methodologies

- > The Case Method

- > Lifelong Learning

- > IESE Insight: Research-Based Ideas

- > IESE Business School Insight Magazine

- > StandOut: Career Inspiration

- > Professors' Blogs

- > IESE Publishing

- SEARCH PUBLICATIONS

- IESE NEWSLETTERS

- > Our Mission, Vision and Values

- > Our History

- > Our Governance

- > Our Alliances

- > Our Impact

- > Diversity at IESE

- > Sustainability at IESE

- > Accreditations

- > Annual Report

- > Roadmap for 2023-25

- > Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- > Barcelona

- > São Paulo

- > Security & Campus Access

- > Loans and Scholarships

- > Chaplaincy

- > IESE Shop

- > Jobs @IESE

- > Compliance Channel

- > Contact Us

- GIVING TO IESE

- WORK WITH US

The case method

The case method is the principal learning methodology that we use in IESE programs.

Unlike lectures in which students passively receive knowledge taught by their professors, at IESE, it’s mainly the students who contribute ideas in dynamic learning classes. We firmly believe that the best way to learn to make professional business decisions is by making them in a safe, academic environment.

Real problems faced by companies in different sectors

Cross-sectional view of general management

Practical learning applied to theory

Through the analysis of real cases, the case method connects theory to practice . It also favors the development of managerial capacities such as analyzing business problems, balancing different perspectives, presenting viable solutions and deriving power from conviction.

Furthermore, as there is often no single solution to a problem, this system allows you to enrich yourself with multiple ideas , experiences and points of view.

How the case method works

The case method is a learning methodology built on learning by doing and which aims to prepare students for strategic decision-making in companies through the practice of real situations .

Individual study and analysis of the case

Small group discussion of the case

Classroom discussion

Conclusions and lessons learned as distilled by professor

After students in groups study and prepare the case , and tackle the problem to be solved, the professor facilitates and guides the classroom debate. Addressing the prognosis prepared by the participants, the professor encourages participation from the entire class in order to deepen the discussion with different points of view stemming from diverse experiences and cultural backgrounds.

Benefits of the case method

This method was first used at Harvard in the early 20th century and has since become hugely popular thanks to its effectiveness in developing knowledge, skills and attitudes among experienced students. These are the benefits:

1. Shape new perspectives through active listening with classmates and teachers.

2 Improve critical judgment through discussion. Expand the capacity for diagnosis and reflection.

3. While making decisions within the case method, learn how to make decisions you can apply to your company.

4. Develop a cross-sectional view of general management to face any business decision.

5. Apply ethical management values and organizational purpose toward making decisions with people at the center.

Case study method: The art of discussion

Real companies, practical dilemmas

In order for this active learning to be vigorously carried out, it’s essential that the cases analyzed be of top quality. At IESE, we work with real companies such as Apple, Amazon, Adidas and Unilever , to name a few, always bearing in mind that the data analyzed:

- Present serious dilemmas.

- Are of general interest and attractiveness. In other words, they can be used anywhere in the world and not in a single culture or country.

- Are aligned with the general management of the company.

- Allow to discuss certain ideas or business models in class.

These are some of the questions that professors tend to ask in class when they use the case method that encourage students to propose clear solutions to complex and real problems:

- How can sales improve in this case?

- How can a company increase its revenue stream taking into account its new competitive environment?

- What incentive policies can work in a sector with high turnover?

Examples of the case study

These are just a few examples used in IESE classes of real cases on leading companies:

Marvel Case

Netflix Case

Spotify Case

Amazon Case

Google Case

Adidas Case

Improve your management skills at IESE with the case method.

Do Your Students Know How to Analyze a Case—Really?

Explore more.

- Case Teaching

- Student Engagement

J ust as actors, athletes, and musicians spend thousands of hours practicing their craft, business students benefit from practicing their critical-thinking and decision-making skills. Students, however, often have limited exposure to real-world problem-solving scenarios; they need more opportunities to practice tackling tough business problems and deciding on—and executing—the best solutions.

To ensure students have ample opportunity to develop these critical-thinking and decision-making skills, we believe business faculty should shift from teaching mostly principles and ideas to mostly applications and practices. And in doing so, they should emphasize the case method, which simulates real-world management challenges and opportunities for students.

To help educators facilitate this shift and help students get the most out of case-based learning, we have developed a framework for analyzing cases. We call it PACADI (Problem, Alternatives, Criteria, Analysis, Decision, Implementation); it can improve learning outcomes by helping students better solve and analyze business problems, make decisions, and develop and implement strategy. Here, we’ll explain why we developed this framework, how it works, and what makes it an effective learning tool.

The Case for Cases: Helping Students Think Critically

Business students must develop critical-thinking and analytical skills, which are essential to their ability to make good decisions in functional areas such as marketing, finance, operations, and information technology, as well as to understand the relationships among these functions. For example, the decisions a marketing manager must make include strategic planning (segments, products, and channels); execution (digital messaging, media, branding, budgets, and pricing); and operations (integrated communications and technologies), as well as how to implement decisions across functional areas.

Faculty can use many types of cases to help students develop these skills. These include the prototypical “paper cases”; live cases , which feature guest lecturers such as entrepreneurs or corporate leaders and on-site visits; and multimedia cases , which immerse students into real situations. Most cases feature an explicit or implicit decision that a protagonist—whether it is an individual, a group, or an organization—must make.