Empowering Informal Workers, Securing Informal Livelihoods

- Informal economy

- Occupational Groups

- Street Vendors

Street Vendors and Market Traders

Street vendors and COVID-19

Statistical Snapshot

Driving forces & working conditions, policies & programmes, organization & voice.

Worker stories from StreetNet: From fighting eviction and police harassment to building a better future through credit and microloans, organized street vendors improve their lives. Read the stories .

Vital Contributors to Urban Economies

Street vendors and market traders are an integral part of urban economies around the world, offering easy access to a wide range of affordable goods and services in public spaces. They sell everything from fresh vegetables to prepared foods, from building materials to garments and crafts, and from consumer electronics to auto repairs to haircuts.

E-BOOK: Street Vendors and Public Space: Essential insights on key trends and solutions (February 2020) – Through photography and text, this e-book offers an in-depth look at the important role street vendors play in cities, the challenges they face, and the solutions that can make cities more vibrant, secure, and affordable for all.

BLOG: Five Must-reads on Including Street Vendors in Public Spaces

TOOLKIT: Supporting Informal Livelihoods in Public Space: A Toolkit for Local Authorities

Contributions

WIEGO’s 2012 Informal Economy Monitoring Study ( IEMS ) revealed ways in which street vendors in five cities strengthen their communities:

- Most street vendors provide the main source of income for their households, bringing food to their families and paying school fees for their children.

- These informal workers have strong linkages to the formal economy. Over half of the interviewed workers said they source the goods they sell from formal enterprises. Many customers work in formal jobs.

- Many vendors try to keep the streets clean and safe for their customers and provide them with friendly personal service.

- Street vendors create jobs, not only for themselves but for porters, security guards, transport operators, storage providers, and others.

- Many generate revenue for cities through payments for licenses and permits, fees and fines, and certain kinds of taxes.

Street trade also adds vibrancy to urban life and in many places is considered a cornerstone of historical and cultural heritage.

Despite their contributions, street vendors face many challenges, are often overlooked as economic agents and unlike other businesses, are often hurt rather than helped by municipal policies and practices.

Street vendors sell goods and offer services in broadly defined public spaces, including open-air spaces, transport junctions and construction sites. Market traders sell goods or provide services in stalls or built markets on publicly or privately owned land ( WIEGO Statistical Brief 8 ).

Street vendors are a large and very visible workforce in cities, yet it is difficult to accurately estimate their numbers (see Challenges of Obtaining Statistics on Street Vendors ). The WIEGO Statistics Programme publishes data based on official statistics on both street vendors and market traders. In 2012, WIEGO published data on street trade in 11 cities in 10 countries ( WIEGO Working Paper no.9 ). Street vendors and market traders are two of the worker groups in the more recent WIEGO Statistical Brief series on informal workers. The briefs present statistics on the numbers, the working arrangements and the characteristics of these two groups based on official statistics at the national, urban and city levels.

Street vendors and market traders are a significant proportion of the urban labour force in developing countries.

- Ghana (2015): 39 per cent of women and 10 per cent of men employed in urban Ghana are market traders; 5 per cent of women and 1 per cent of men are street vendors. Together, street vendors and market traders are 29 per cent of total urban employment ( WIEGO Statistical Brief no.21 ).

- 8 Major South African Metro Areas (2018): 3 per cent of women and 2 per cent of men employed in these metro areas are street vendors; one per cent of both women and men are market traders. Together they comprise 2 per cent of employment in the areas ( WIEGO Statistical Brief no.19 ).

- India (2017/18): 3 per cent of women and 5 per cent of men in urban employment are street vendors and market traders comprising 4 per cent of total urban employment ( WIEGO Statistical Brief no.24 ); (2018/19): 4 per cent of women and 2 per cent of men in urban employment are street vendor and market traders, comprising around 4 per cent of total urban employment (see tables under ‘Additional Data for India’ here ).

- Thailand (2017): 4 per cent of women and 3 per cent of men in urban employment are market traders; 3 per cent of women and 2 per cent of men in urban employment are street vendors, comprising 6 per cent of total urban employment ( WIEGO Statistical Brief no.20 ).

- Mexico (2019): 3 per cent of women and 2 per cent of men in urban employment are market traders; 4 per cent of women and 3 per cent of men are street vendors. Together both comprise 6 per cent of urban employment ( WIEGO Statistical Brief no.22 ).

- Peru (2015): 10 per cent of women in non-agricultural employment in urban Peru (outside of Lima) and 4 per cent of men are street vendors; 6 per cent of women and 2 per cent of men are market traders. Together the groups jointly comprise 11 per cent of non-agricultural urban employment outside of Lima ( WIEGO Statistical Brief no.16 ).

Street Vending, Market Trade and Gender

The statistics above indicate that street and market trade are generally greater sources of employment for women than for men. Further, a higher share of women than men sell food and other perishable goods ( Roever 2014 ; WIEGO Statistical Brief no.16 ), which are more likely than other goods to spoil or to be confiscated. Research also shows that women street vendors typically earn less than men—and, in many countries, less than half as much as men ( Chen and Snodgrass 2001 ; WIEGO Statistical Brief no.16 ). The difference in earnings is not entirely explained by women working fewer hours than men. The Peru study found that although women market traders and street vendors worked fewer hours than men, the net hourly earnings of women were less than men’s for market traders and for street vendors in urban areas (other than Lima). Only women street vendors in Lima had slightly higher net hourly earnings than men ( WIEGO Statistical Brief no.16 ).

Low barriers to entry, limited start-up costs, and flexible hours are some of the factors that draw street vendors to the occupation. Many people enter street vending because they cannot find a job in the formal economy.

But surviving as a street vendor requires a certain amount of skill. Competition among vendors for space in the streets and access to customers is strong in many cities. And vendors must be able to negotiate effectively with wholesalers and customers.

Street trade can offer a viable livelihood, but earnings are low and risks are high for many vendors, especially those who sell fresh fruits and vegetables ( Roever 2014 ). Having an insecure place of work is a significant problem for those who work in the streets. Lack of storage, theft or damage to stock are common issues.

By-laws governing street trade can be confusing and licenses hard to get, leaving many street vendors vulnerable to harassment, confiscations and evictions. Learn more about Street Vendors and The Law .

Occupational Health and Safety

Working outside, street vendors and their goods are exposed to strong sun, heavy rains and extreme heat or cold. Unless they work in markets, most don’t have shelter or running water and toilets near their workplace. Inadequate access to clean water is a major concern of prepared food vendors.

Street vendors face other routine occupational hazards. Many lift and haul heavy loads of goods to and from their point of sale. Market vendors are exposed to physical risk due to a lack of proper fire safety equipment, and street vendors are exposed to injury from the improper regulation of traffic in commercial areas.

Insufficient waste removal and sanitation services result in unhygienic market conditions and undermine vendors’ sales as well as their health, and that of their customers.

Meet an indigenous caterer in a market in Accra, Ghana .

Vulnerability to Economic Downturns

The COVID-19 crisis has severely impacted vendors’ ability to earn a livelihood. Read more here .

COVID-19 was not the first crisis to hit street vendors hard. Economic downturns have a big impact on vendors’ earnings. In 2009, an Inclusive Cities research project found many street vendors reported a drop in consumer demand and an increase in competition as the newly unemployed turned to vending for income.

A second round of research, done in 2010, found demand had not recovered for most vendors, and many had to raise prices due to the higher cost of goods. Competition had increased further as large retailers aggressively tried to attract customers.

The 2012 Informal Economy Monitoring Study confirmed that rising prices and increased competition were still affecting street vendors in several cities. Vendors said their stock was more expensive, but they had difficulty passing on rising costs to consumers, who expect to negotiate low prices on the streets. More competition means vendors take home lower earnings.

Street vending generates enormous controversy in cities throughout the world. Key debates about street vending involve registration and taxation, individual vs. collective rights, health and safety regulations – especially where food is involved – and urban planning and governance.

An analysis by WIEGO's Urban Policies team found street vendors face increased hostility worldwide as they vie for access to public space.

Urban policies and local economic development strategies rarely prioritize livelihood security for informal workers. Urban renewal projects, infrastructure upgrades and mega events routinely displace street vendors from natural markets, leaving the most vulnerable without a workplace.

Good practice documentation shows vendors can help with urban management challenges like crime and cleaning. Also, basic infrastructure – shelters, toilets, electricity and water – can both improve vendor work environments and make public space safer, more comfortable and aesthetically pleasing.

Some cities are working with street vendors’ organizations to formulate innovative policies, programmes and practices that enable vendors to have a voice in making their cities more inclusive.

Bangkok was a leader when it came to selling goods and services in public spaces both day and night. Vending in Public Space: The Case of Bangkok (Yasmeen and Nirathron 2014) examines how this arose, especially given the country’s evolving political and economic agenda. However, since 2014 the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA), under a military junta, has evicted tens of thousands of Bangkok vendors . Resistance by street vendors has been intense.

Membership-based organizations help street vendors navigate their relationship with the authorities, build solidarity and solve problems with other vendors. Several have developed innovative ways to work with cities to keep the streets clean and safe while gaining a secure livelihood for vendors. Key demands of organized street vendors and market traders include the provision of infrastructure – including designated and appropriately designed trading and storage space, as well as toilets; access to affordable water and electricity to support economic activities; social protection coverage; an end to harmful city regulations and practices; and inclusion in all levels of decision-making on matters that affect them.

A strategy pursued by street and market vendor organizations to achieve these demands is to insist that local authorities recognize them as bargaining partners, and agree on local negotiation forums. In support of this end WIEGO and StreetNet International produced a handbook on Collective Negotiations for Informal Workers as part of the Organizing in the Informal Economy: Resource Books for Organizers Series .

Examples of achievements include:

- The Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) and the National Association of Street Vendors of India (NASVI) were instrumental in making India’s National Law on Street Vending a reality. This national law recognizes, regulates and protects the livelihoods of street vendors.

- In Durban, South Africa, street vendor organizations came together (supported by Asiye eTafuleni , StreetNet International, unions and other civil society organizations) to fight the demolition of the Warwick Junction market to make way for a formal mall. However, these market vendors are continuously under new threats and must maintain resilience and solidarity .

In 2000, national street and market vendor organizations came together globally to form StreetNet International, as a means of amplifying the voice of street and market vendors internationally. WIEGO was fully in support of the formation of SNI, and continues to work closely with it, providing technical and organizational support.

Learn more about Organizing & Organizations .

WIEGO Specialist

Caroline Skinner Director Urban Policies Programme

Related Reading

- WIEGO Focal City Delhi and Social Design Collaborative. 2020. Street vending in times of COVID-19: GUIDELINES FOR STREET VENDORS . WIEGO

- Skinner, Caroline, Jenna Harvey, Sarah Orleans Reed. 2018. Supporting Informal Livelihoods in Public Space: A Toolkit for Local Authorities . WIEGO and Cities Alliance

- Roever, Sally. 2016. " Street Vendors and Cities ." Environment and Urbanization. Vol 28, No. 2.

- Roever, Sally. 2014. IEMS Sector Report: Street Vendors . WIEGO.

- Herrera, Javier, Mathias Kuépié, Christophe J. Nordman,Xavier Oudin and François Roubaud. 2012. Informal Sector and Informal Employment: Overview of Data for 11 Cities in 10 Developing Countries . WIEGO.

- Pamhidzai H. Bamu , 2019. Street Vendors and Legal Advocacy: Reflections from Ghana, India, Peru, South Africa and Thailand (Resource Document).

- Carré. 2014. Location, Location, Location: The Life of a Refugee Street Barber in Durban, South Africa .

- Kumar, Randhir. 2012. The Regularization of Street Vending in Bhubaneshwar, India: A Policy Model . WIEGO Policy Brief (Urban Policies) No. 7.

See all publications about Street Vending .

Top photo: Street vendor Faustina Kai Torgbe sells vegetables and other food in Accra, Ghana. Credit: Jonathan Torgovnik/Getty Images Reportage

Related blog posts.

- HomeNet Thailand

- WIEGO Individual Members

- Past Board of Directors

- WIEGO Board Biographies

- WIEGO Team Bios

- News & Events

- Our Manifesto

- General Assemblies

- Annual Reports

- Public Health and Tax Project Coordinator

- COVID-19 Crisis and the Informal Economy Study

- Support informal workers' campaigns

- Resources for Informal Workers

- Domestic Workers

- Home-Based Workers

- Waste Pickers

- Organization & Representation

- Administrative Justice for Informal Workers

- Home-based workers in Bulgaria: Using the ILO Reporting Mechanism to Work

- Law Programme Engagement in Global Agenda Setting Processes

- Social Protection Briefing Notes

- Urban Policies

- Delhi and the COVID-19 Epidemic COVID-19 and Delhi’s Waste Pickers

- Focal City Learning Meeting 2020

- Not just hunger but also safety: Relief for waste pickers during COVID-19

- Impact of COVID-19 on Street Vendors in India: Status and Steps for Advocacy

- New Year's Message

- Rebuilding Lives in Resettlements: The Story of Savita Ben

- Los Rifados de la Basura Campaign

- Exposure Dialogues

- Policy Dialogues

- Organizing & Organizations

- Working in Public Space: Resources

- Income Security for Older Workers

- Informal Economy Podcast

- Workers' Health

- Law & Informality

- Formalizing

- Women's Economic Empowerment

- History & Debates

- Statistical Picture

- Concepts, Definitions & Methods

- Development of Statistics on the Informal Economy

- "Making C189 Real": The Domestic Workers Project

- Waste Pickers Fighting Climate Change

- Hierarchies of Earnings and Poverty

- Links with Poverty: Data Sources

- Links with Poverty: Earlier Findings

- Links with Inequality

- Links with Growth

- Impact of the Global Recession on Members of SEWA in India

- Support to Informal Workers During & After Economic Crises

- Worker Stories

- Policy Framework

- WIEGO Working Papers

- WIEGO Briefs

- WIEGO Resource Documents

- Workers' Lives

- ILO-WIEGO Statistical Reports

- WIEGO Monitoring, Learning and Evaluation Toolkit

- Peer reviewed publications

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

The impact of urban culture on street vending: a path model analysis of the general public's perspective.

- 1 School of Business, Skyline University College, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

- 2 Faculty of Administrative Sciences, University of Al-Mashreq, Baghdad, Iraq

- 3 Department of Business Administration, Faculty of Economics and Administration, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- 4 Faculty of Finance, University of Maryland Global Campus, Adelphi, MD, United States

- 5 Faculty of Finance, University of Louisiana Monroe, Monroe, LA, United States

This study examined the relationship between urban culture and street vending. Prior research on this topic is limited and inconclusive. Therefore, we have proposed an integrated model to test the positive effect of urban culture on street vending using multiple mediations of consumption patterns, resistance, and microfinance. We tested a sample of 425 responses that reflect the public opinion in Baghdad, Iraq. These responses were collected between September and November 2018. A partial least squares–based structural equation modeling is employed to test the validity of measurement models and the significance of the entire structural model, predictive power, and mediation analysis. We found that resistance mediates the effect of urban culture on street vending; low-income consumption and resistance sequentially mediate the effect of urban culture on street vending, while resistance mediates the effect of a lack of microfinance on street vending. The direct impact of culture on street vending is not significant, and a lack of microfinance positively influences the pervasiveness of trading on streets. This study contributes to the extant literature as it proposed and tested a novel and comprehensive model to analyze the relationship between urban culture and street vending, simultaneously examining the effects of culture, consumption, resistance, and microfinance on street vending.

Introduction

Unlicensed street vendors occupy public spaces and traditional markets, creating problems for residents, pedestrians, formal retailers, and public authorities. They sometimes cause conflicts in society, potentially leading to violence ( Tonda and Kepe, 2016 ). Moreover, they often employ children, working individually or with their parents ( Estrada, 2016 ), and are frequently accused of drug trading and counterfeiting ( Ilahiane and Sherry, 2008 ). On the other hand, in many countries, the informal economy, which consists mainly of street vending, plays a crucial role in income generation, employment creation, and production ( Recchi, 2020 ).

There are no accurate data for street vending or for the informal economy in general due to the fact that street vending and/or informal sector are informal activities operating without registration and licenses. According to the conceptualization of the International Labor Organization (ILO), the formal economy consists of government entities in addition to registered private units with fixed premises, while the informal sector includes unregistered business units such as street vending, agricultural family production, daily construction work, and home-based enterprises ( OECD/ILO, 2019 ). An indicator of the scale of street vending is that informal employment accounts for 42% of total nonagricultural employment in Thailand (2010), 50% in Argentina (2009), 61% in Ecuador (2009), and 70% in Zambia (2008) as estimated by the ILO ( ILO, 2013 ). If we add the small family farms, the informal sector represents a huge part of the entire economy in most developing countries.

The study chose Baghdad, Iraq as a sample to analyze the relationship between culture and street vending for multiple reasons. First, street vending is a crucial part of the vibrancy of cities like Baghdad, Iraq's capital. Second, Iraqis often buy from and trust peddlers; most of the time, the public authorities ignore them. Third, the pervasiveness of street vending has increased dramatically over the last 15 years in the wake of political changes. Since the occupation of Iraq by the US-led alliance in 2003, the state and its major institutions have collapsed. Political and social stability has been severely damaged, and the state has mainly allocated its financial resources to fighting terrorism and resolving sectarian tensions. Moreover, the new regime has shifted to a free-enterprise market that has replaced the state as the major source of employment that it used to be during Saddam Hussein's dictatorial regime. As a result, the unemployment rate has increased, especially among young people, and one-fifth of the population has fallen below the poverty line, even though the country is ranked fifth in the world for oil exports. The number of street vendors has increased sharply, and the public authorities have been unable to formalize their status. Government attempts to evict street vendors or destroy their stalls sometimes trigger protests, such as the major demonstration at the beginning of October 2019 against corruption, unemployment, and poor public services. We have therefore chosen to investigate this widespread and problematic issue.

This study examines the relationship between urban culture and street vending, since the literature on this topic is quite sparse ( Tamilarai and Angayarkanni, 2016 ; Wibisono and Catrayasa, 2018 ). Scholarly research has focused on street vendors who choose their profession willingly for cultural reasons, and who have a spiritual motivation that gives them satisfaction, enabling them to provide high-quality services in the perception of their clients ( Wibisono and Catrayasa, 2018 ). Understanding of this relationship between culture and street vending needs to be enriched, since research has yielded contradictory statistical results ( Voiculescu, 2014 ; Tamilarai and Angayarkanni, 2016 ; Alvi and Mendoza, 2017 ; Wibisono and Catrayasa, 2018 ). Few studies have taken account of the fact that low-income customers prefer to shop in neighboring streets at low prices and to spend only a short time doing so ( Yatmo, 2009 ; Tamilarai and Angayarkanni, 2016 ). Therefore, when scholars consider low-income consumption as a dimension of urban culture, their statistical results are inconsistent ( Steel, 2012a ; Trupp, 2015 ; Tamilarai and Angayarkanni, 2016 ).

Some researchers have suggested a direct effect of resistance on the pervasiveness of street vending, noting that street vendors, in order to survive, adopt a strategy of resistance, despite restrictive policies ( Hanser, 2016 ; Boonjubun, 2017 ). Here, we argue that resistance as a mediator is able to explain the relationship between culture (or low-income consumption) and street vending, given that urban culture (or low-income consumption) may not affect street vending directly. For this reason, we propose a mediation model that can be examined theoretically and empirically. The model posits that urban culture positively impacts street vending through low-income consumption and resistance and the mediating effect of resistance on the relationship between a lack of microfinance and street vending.

This study relies on the cultural approach, which argues that street vendors choose their endeavor for cultural reasons rather than on the basis of rational decisions. They establish relationships with their friends and the community on the basis of solidarity and reciprocity, and they successfully build relationships with customers on the basis of trust. They also enjoy freedom and flexibility that allow them to have control over their lives. For their part, customers support street vendors who offer the goods and the services they need at affordable prices ( Williams and Gurtoo, 2012 ; Williams and Youssef, 2014 ). In this context, the present study examines whether culture impacts street vending directly or indirectly through consumption and resistance.

The model is tested empirically, using a survey of the general public's attitudes toward street vending and corresponding factors in the context of Baghdad. Researchers have reviewed public policies on street vending on the basis of national data ( Ilahiane and Sherry, 2008 ; Lyons, 2013 ) and have interviewed street vendors to identify their characteristics ( Reid et al., 2010 ; Tengeh and Lapah, 2013 ; Wibisono and Catrayasa, 2018 ). However, there remains a need to understand public opinions on street vending before reviewing public policies on this activity ( Chai et al., 2011 ). The current study formulates a public perspective on this widespread problem in cities, which is a necessary step in developing appropriate legislation.

The study makes significant contributions to the literature on street vending. First, it tests the cultural approach by investigating the direct and indirect effects of culture on street vending. Second, it introduces a distinctive model using sequential mediation analysis. Third, the model is expanded by the addition of the mediating effect of resistance on the relationship between microfinance and street vending. Finally, the results can be used to rank the factors that drive the pervasiveness of street vending in order of importance, with managerial implications for dealing fairly with this problematic issue in the cities of developing countries.

Section Conceptual Framework and Hypothesis Development introduces the conceptual framework and develops the hypotheses on the basis of a thorough review of the literature. Section Methodology sets out the sampling and data collection procedure, derives measurement items for the constructs of the model, and provides a rationale for using a partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) approach to analyze the data. Section Results tests the model and hypotheses and reports the results. Section Discussion and Conclusion discusses the theoretical and managerial implications of the findings, and then considers the limitations of the study and future research directions.

Conceptual Framework and Hypothesis Development

Scholars often consider the informal economy as an indicator of economic underdevelopment or as an obstacle to economic development. However, in developing and low-income countries, the informal sector increasingly contributes to the elimination of unemployment and poverty ( Ilahiane and Sherry, 2008 ; Lyons, 2013 ). Street vendors (hawkers or peddlers), as a main element in the informal economy, have existed for decades ( Nani, 2016 ). They are continually at risk of eviction from sidewalks and crowded markets ( Recio and Gomez, 2013 ) because public officials tend not to appreciate the role of hawkers, although their businesses play a major role in the informal economy, contribute to the vibrancy of cities, and form an obvious part of the general economy ( Khan and Quaddus, 2020 ).

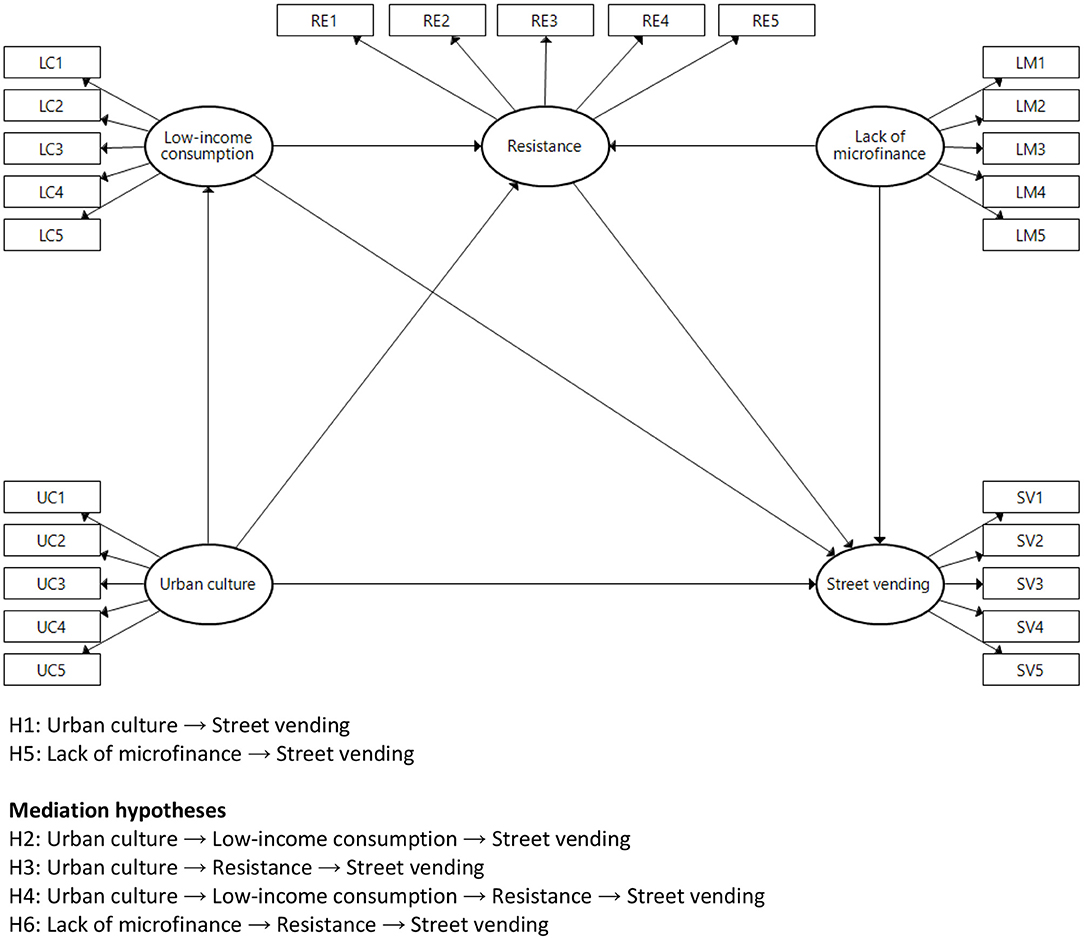

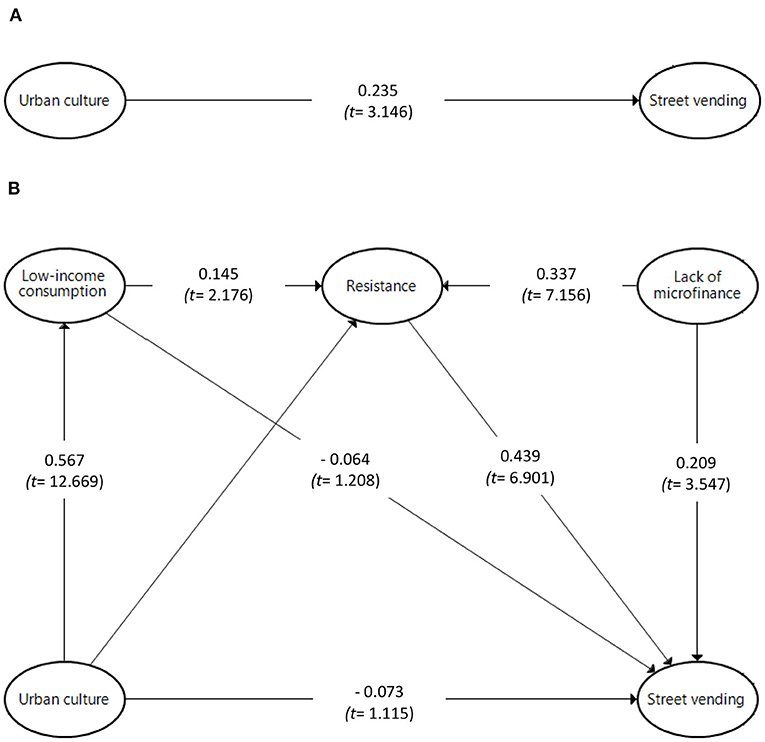

Street vendors earn a low level of income and must compete with formal sellers ( Agadjanian, 2002 ). It is worth noting that there are often too many vegetable sellers competing with each other in overcrowded areas. In this connection, we should differentiate between licensed and unlicensed street vendors. While licensed sellers enjoy a formal relationship with municipal authorities and public officials, unlicensed vendors work under precarious conditions, struggling to avoid eviction from the public streets ( Cuvi, 2016 ). Our study analyzes the impact of urban culture on the pervasiveness of unlicensed street vending via consumption patterns and resistance, in addition to the impact of a lack of microfinance on street vending via resistance. The conceptual research model ( Figure 1 ) and its hypotheses are rooted in the literature, as the following subsections demonstrate.

Figure 1 . Conceptual research model.

Urban Culture

Urban or street culture refers to values and practices shared by the residents of cities. Street vending is a core part of this culture. As we have observed in Baghdad, customers visit nearby traditional markets not only to make purchases but also to spend time communicating with each other, meeting their friends, walking, and looking at the attractive offerings of street vendors. Meanwhile, street vendors are reluctant to move into the formal sector, preferring the hazardous conditions of the informal sector to the relative safety of formal activities ( Alvi and Mendoza, 2017 ). It is this preference that enables them to tolerate the difficulties they encounter ( Tamilarai and Angayarkanni, 2016 ). Some vendors love the flexible spaces and movement; they are voyagers who carry their emotions and dreams with them as they explore new landscapes ( Voiculescu, 2014 ). They enter the informal economy for cultural reasons, such as continuing a traditional family activity, and for social or lifestyle reasons ( Williams and Gurtoo, 2012 ). The urban culture of a city also determines the traditional recipes and eating habits that match the food offered by street vendors ( Wardrop, 2006 ), and the public streets where readers and sellers of newspapers come together represent shared cultural interests ( Reuveni, 2002 ). Thus, we hypothesize:

H1 . Urban culture positively impacts street vending.

Low-Income Consumption

Street vendors cannot compete with retail shops in terms of quality, brand name, or variety of products; instead, they attract customers who intend to spend only a short period of time shopping and buy at low prices ( Tamilarai and Angayarkanni, 2016 ). Traditional markets combine both retail shops and street vendors who intentionally locate their business in crowded areas. For instance, low-income customers who cannot afford to go to restaurants buy cooked food from sellers on the streets. Even though their business is somewhat threatened by the formal food retail industry, those sellers continue to provide food to those consumers. Generally, the vendors themselves try to understand changes in customers' needs and to select appropriate public places to reach certain groups of customers, such as tourists ( Steel, 2012a ). For example, souvenir vendors have become a core part of the tourism economy in countries such as Thailand ( Trupp, 2015 ). Nowadays, vendors increasingly use social media platforms to disseminate information about their business, communicate with nearby customers, and persuade them. Then, customers often respond positively to purchasing from those vendors ( Wang et al., 2021b ).

Customers enjoy purchasing the products offered in the public streets and traditional markets, since this consumption pattern reflects their values and beliefs. For example, food consumption habits and styles are determined by geographical location, climate, and what foodstuffs can be produced locally, with the result that consumption patterns pass from one generation to the next. Specifically, meat consumption is affected by religion, history, and urban culture ( Nam et al., 2010 ). In short, the culture teaches vendors to produce traditional food or drink that appeals to customers. For their part, the customers, again as part of the culture, enjoy buying such food on the public streets and can identify trusted sellers. Therefore, urban culture establishes a pattern of low-income consumption that creates a real demand for the products offered by street vendors. Thus, we hypothesize:

H2 . Low-income consumption mediates the effect of urban culture on street vending.

Depending on their social networks, street vendors occupy certain traditional markets or sidewalks ( Tengeh and Lapah, 2013 ); that is, they belong to specific tribes or cities, which gives them a degree of power against residents and authorities. Itinerant vendors, for instance, resist in order to be allowed to remain on the sidewalks and in the markets, taking individual and collective action and sometimes organizing protests ( Steel, 2012b ). Vendors have neither safety nor security, because they face harassment from the local authorities and often have to pay bribes to sustain themselves on the streets ( Saha, 2011 ). When the authorities demolish their stalls, they find ways to return to their sites with a higher level of resistance ( Musoni, 2010 ). Governmental organizations can reduce the level of resistance by introducing justice practices among peddlers by offering sort of support to them such as building infrastructure in order to formalize their business ( Rehman et al., 2021 ).

Informal workers generally do not group themselves into organizations. Thus, they do not have the collective power to negotiate with governmental organizations, such as the police and municipal authorities, or to collaborate to improve their working conditions ( Hummel, 2017 ). Nevertheless, although city authorities have legal powers, street vendors tend to develop a set of strategies for acquiring formal and informal power ( Boonjubun, 2017 ; Forkuor et al., 2017 ; Hummel, 2017 ; Te-Lintelo, 2017 ). Thus, resistance gives vendors the ability to stay on the sidewalks and in the markets despite the objections of city officials and residents ( Zhong and Di, 2017 ).

People who suffer from poverty and unemployment develop their own subculture to resist oppression (T. A. Martinez, 1997 ). Street vendors who are poor or unemployed find ways to resist and continue their businesses on the public streets so that they can survive; they do so regardless of the concerns of the official authorities. Researchers have argued that certain groups in a society develop their own oppositional cultures that empower them to resist public trends ( Ainsworth-Darnell and Downey, 1998 ). These vendors believe that they have the right to survive in their neighborhood, and that the authorities do not have the right to evict them unless officials arrange alternative employment for them. Consequently, the culture generates values and beliefs in favor of peddlers staying on the public streets, with the approval of customers, and resistance supports them in doing this. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3 . Resistance mediates the effect of urban culture on street vending.

Urban culture creates a consumption pattern, especially for low-income customers. This pattern represents real demand for products offered in public spaces and on sidewalks, and street vendors find their businesses profitable because of the willingness of customers to deal with them. The resulting consumption pattern consolidates the persistence of street vendors working in the informal trading sector. For instance, Khan (2017) found that street vendors are distinguished by cheaper pricing and quicker delivery, and that their customers see street vending as conveniently located, with flexible times and rich customization. Since urban culture generates low-income consumption, the real demand for products offered on public streets establishes resistance among vendors, thereby facilitating the survival of their livelihood and justifying their pervasiveness. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4 . Low-income consumption and resistance sequentially mediate the effect of urban culture on street vending.

Lack of Microfinance

The pervasiveness of street vending can also be explained by a lack of microfinance. Husain et al. (2015) found that personal savings constitute the most considerable source of financing for peddlers. Lyons (2013) found that when peddlers find it difficult to secure formal credit facilities from commercial banks and financial funds, they sell their assets or borrow from cooperative organizations. To finance their economic activities and social security, street vendors sometimes borrow money at exorbitant rates of interest ( Saha, 2011 ; Martinez and Rivera-Acevedo, 2018 ). Therefore, governments should set up specialized organizations to provide financial support to microbusinesses. Likewise, commercial banks should be encouraged to lend to very small businesses, and the loans should be based on knowledge of the market rather than on technical evaluation of the risks; in this context, an intuitive approach to lending will lead to better results than quantitative methods ( Malôa, 2013 ).

Informal sellers are among the poorest people in society. They cannot afford to rent a retail outlet, expand their business, or shift to the formal sector ( Tamilarai and Angayarkanni, 2016 ). Moreover, they do not meet the minimum requirements to apply for a loan, and banks are reluctant to be involved in microfinance. In short, an acute lack of microfinance results in poor and uneducated people trading on the streets, in contrast to a mature and developed financial system, which would create easier channels for financing microbusinesses and give unemployed people the opportunity to set up small formal businesses ( Esubalew and Raghurama, 2020 ). Since most unemployed and poor people have no access to the financial system to obtain loans, they become resistant. Thus, the strong resistance of street vendors can be explained in part by a lack of microfinance, which leads them to stay on the public streets. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H5 . A lack of microfinance positively impacts street vending.

H6 . Resistance mediates the effect of a lack of microfinance on street vending.

Methodology

Sampling and data collection.

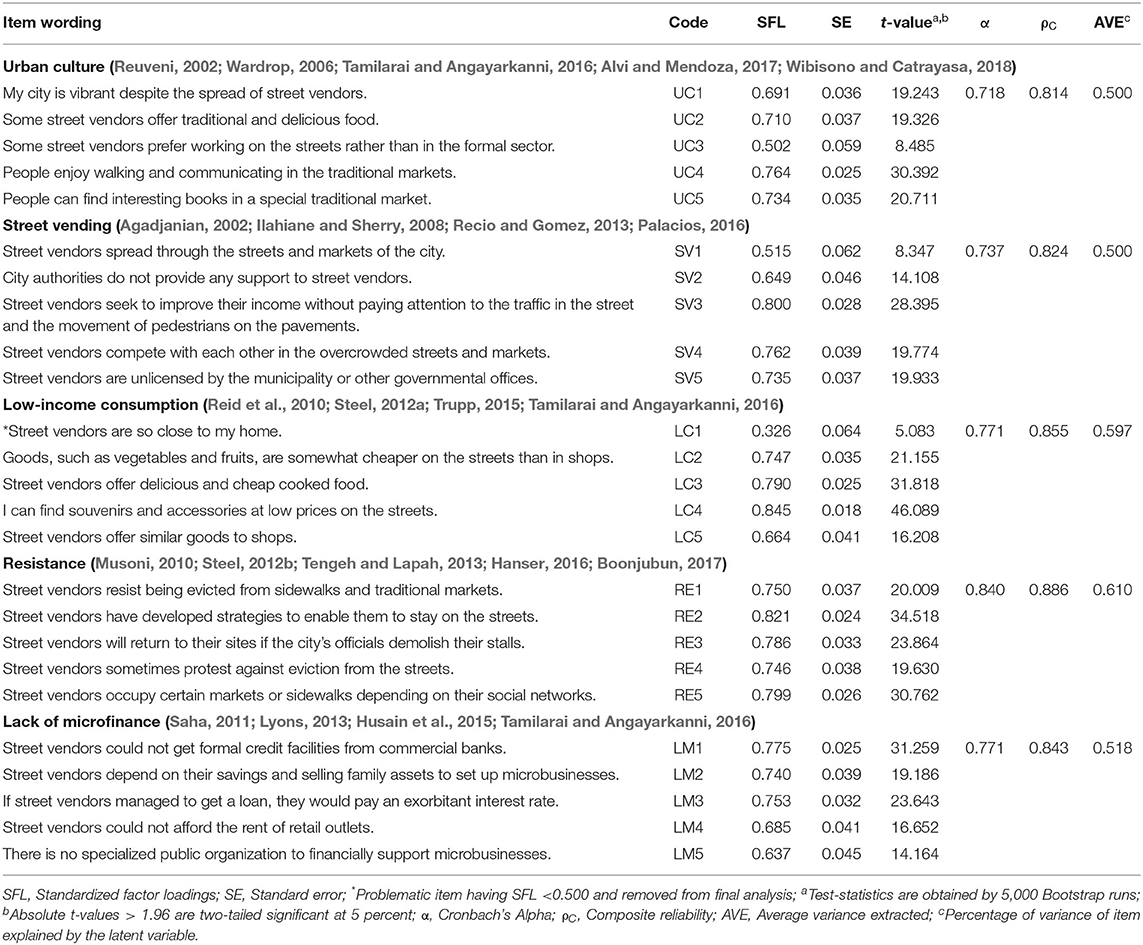

The measurement items for the constructs in this study, displayed in Table 1 , were translated into Arabic, a language that the majority of Iraqis speak. To check the suitability of the items for the Iraqi cultural context, the questionnaire was discussed with five colleagues at the Middle Technical University, Baghdad, and an initial sample of 25 responses was analyzed. The results confirmed that most of the street vendors are Iraqis and that public officials mostly ignore them, although the authorities sometimes evict them from public streets and traditional markets. The results also indicated that most of the street vendors are uneducated, but that some have secondary school certificates, a diploma, or even a bachelor's degree, because unemployment has spread among young people and graduates. We modified the questionnaire in light of these findings, and the results are shown in Table 1 in an English version.

Table 1 . Measurement model assessment.

Some researchers have interviewed street vendors in order to understand their characteristics and the factors that affect their livelihoods ( Reid et al., 2010 ; Tengeh and Lapah, 2013 ; Wibisono and Catrayasa, 2018 ). The current study instead adopts the approach recommended by Chai et al. (2011) , with the aim of tracking the attitudes of the general public on the problematic issue of street vending. Their approach is appropriate because the problem affects the social and economic daily life of cities in two opposing ways. On the one hand, it has negative impacts in terms of traffic, competition with the modern retail industry, and violence. On the other hand, it reduces poverty and unemployment. Obtaining a clear understanding of public opinion on the issue is, therefore, a necessary step in reviewing public policies on how to deal fairly with street vendors.

Google Forms were used to administer the electronic survey, which was distributed via a hyperlink sent to participants by e-mail, WhatsApp, or Facebook. We began by inviting students, administrative staff, and faculty members at Middle Technical University, Baghdad to take part. Then, we encouraged our students to ask their friends and relatives outside the university to participate, and we also involved digital friends contacted via social networks. Our aim was to include 600 participants from a range of social classes. In the end, because of limitations of time and resources, we collected 463 responses. We excluded 38 of these on the grounds that the respondents had given the same answer to all the questions. The final sample, therefore, consisted of 425 complete and usable responses collected between September and November 2018. The raw data were deposited at Mendeley and can be viewed at Al-Jundi (2019) .

The study adopted a sampling method introduced by Krejcie and Morgan (1970) in order to determine the minimum size of the sample required for a given population. A total number of 384 participants will be required to gain a 95% confidence interval for a population that exceeds one million persons with a marginal error of ±5%. We managed to collect 425 reliable responses that are acceptable, taking into consideration the limitations of this paper (see section Limitations and Recommendations for Further Research). The study, therefore, uses nonprobabilistic sampling with an unlimited population.

Of the participants, 67% were men and 33% were women. In terms of education, 25% had not completed secondary schooling, 41% (most of whom were university students) had a secondary school certificate, 20% had a diploma or a bachelor's degree, and 14% (mainly faculty members) were postgraduates. With regard to monthly household income, 41% earned less than $400, 37% earned $400–999, 12% earned $1,000–1,499, and 10% earned more than $1,500. Participants under the age of 25 accounted for 35% of the sample, while 44% were aged 25–40, and 21% were 41 or older. Thus, the participants come from different educational backgrounds and social classes, which make our sample fairly representative of the general public in the capital city of Baghdad.

Measurement Variables

In order to test the conceptual research model using PLS-SEM, we constructed measurable (observed) variables that reflect constructs drawn from the literature. All the indicator variables were measured using a seven-point Likert-type scale, shown in Table 1 (1 strongly disagree, 2 disagree, 3 somewhat disagree, 4 neither agree nor disagree, 5 somewhat agree, 6 agree, and 7 strongly agree).

The review of the literature served to identify five items that reflect each construct. The measurement items for the pervasiveness of street vending were drawn from work by Agadjanian (2002) , Ilahiane and Sherry (2008) , Recio and Gomez (2013) , and Palacios (2016) , while the observed variables for urban culture were derived from the work of Reuveni (2002) , Wardrop (2006) , Tamilarai and Angayarkanni (2016) , Alvi and Mendoza (2017) , and Wibisono and Catrayasa (2018) . The items for consumption patterns were derived from Reid et al. (2010) , Steel (2012a) , Trupp (2015) , and Tamilarai and Angayarkanni (2016) , and resistance was tracked using indicators proposed by Musoni (2010) , Steel (2012b) , Tengeh and Lapah (2013) , Hanser (2016) , and Boonjubun (2017) . Finally, the lack of microfinance was measured using indicators introduced by Husain et al. (2015) , Lyons (2013) , Saha (2011) , and Tamilarai and Angayarkanni (2016) .

Statistical Procedures

To validate our proposed model, we adopted a structural equation modeling (SEM) approach for a number of reasons. First, SEM is well recognized among researchers, as many of the concepts of social science are latent variables that can only be measured via observed indicators ( Hair et al., 2017 , 2019 ; Latan and Noonan, 2017 ). Second, SEM is more powerful than factor analysis, path analysis, or multiple linear regression and has already been used in similar studies ( Al-Jundi et al., 2019 , 2020 ; Shujahat et al., 2020 ; Ali, 2021 ; Ali et al., 2021a , b ; Wang et al., 2021a ). Third, SEM takes into consideration measurement error in the observed variables involved in a corresponding model ( Fornell and Larcker, 1981 ). Fourth, PLS-SEM allows the examination of causal relationships among many latent variables simultaneously, as well as the calculation of direct and indirect effects of a complex model. Finally, SEM gives a complete picture of the entire model, regardless of the complexity of the relationships among the constructs and observed variables.

There are two approaches to estimating such a model: a covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM) approach and a partial least squares SEM (PLS-SEM) approach. CB-SEM presumes a multivariate normal distribution and seeks to identify the model parameters that minimize the discrepancy between the estimated and sample covariance matrices. PLS-SEM attempts to maximize the explained variance of the endogenous constructs ( Hair et al., 2017 ). The current paper uses the PLS-SEM technique for four reasons. First, PLS-SEM estimates a complex model with many constructs, observed variables, and path model relationships to guarantee convergence regardless of sample size and distribution assumptions ( Gefen and Straub, 2005 ). Second, PLS-SEM focuses on prediction, which allows the derivation of managerial implications. Third, PLS-SEM is suitable for developing a theory ( Hair et al., 2017 , 2019 ). Finally, PLS-SEM is recommended for the estimation of mediation models, including sequential mediation analysis ( Sarstedt et al., 2020 ).

Assessment of the Measurement Model

In the initial step of the factor analysis, item loadings above 0.700 were retained and those below 0.40 were deleted (as recommended by Hair et al., 2017 ). All standardized factor loadings were higher than the cut-off value of 0.707. We found that the item loading for LC1 was below 0.40, and we therefore deleted it. Table 1 shows the outer loadings of all the constructs in the study.

To examine internal consistency reliability, we used Cronbach's alpha (α) and composite reliability (ρ C ) for all the constructs. The rule of thumb indicates that α and ρ C should be above 0.700. As Table 1 shows, these requirements were met for all the constructs.

To assess convergent validity (construct communality), we used average variance extracted (AVE), which is calculated as the mean value of the squared outer loadings associated with each construct ( Gefen and Straub, 2005 ; Hair et al., 2017 ). As Table 1 shows, the AVE for all constructs exceeds the critical cut-off point of 0.500 ( Latan and Noonan, 2017 ), thus ensuring convergent validity.

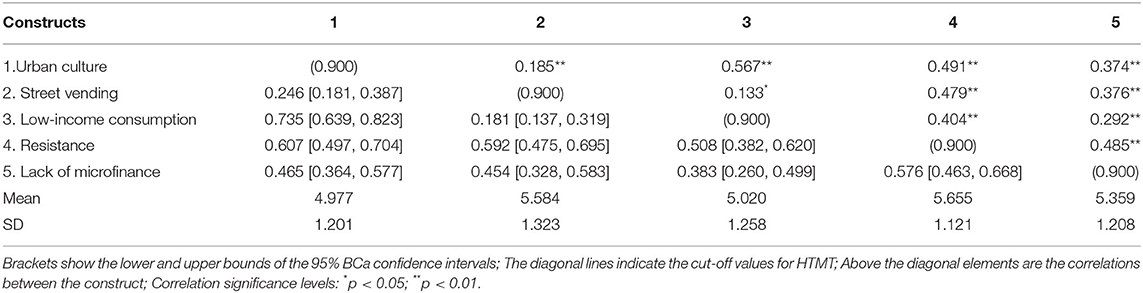

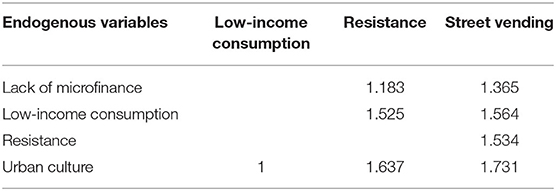

To establish discriminant validity, the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) was used. If the value of HTMT is lower than the threshold value of HTMT 0.85 (the conservative cut-off point) or HTMT 0.90 (the liberal cut-off point), discriminant validity is established ( Henseler et al., 2014 ). Table 2 shows that the HTMT ratios among the constructs are all below the cut-off point of HTMT 0.85 , and discriminant validity is thus established.

Table 2 . Assessment of discriminant validity using HTMT.

Predictive Relevance of the Model

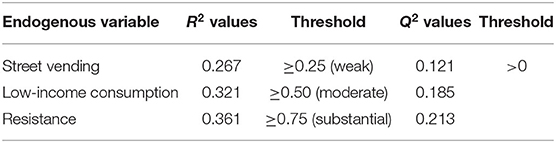

To analyze the model's predictive relevance, we distinguished between in-sample prediction (explanatory power) and out-of-sample prediction (predictive power). Explanatory power can be evaluated using the coefficient of determination ( R 2 ), which indicates the predictive accuracy. As a rule of thumb, R 2 values below 0.25 are considered weak. Table 3 shows that the R 2 values for street vending (0.267), low-income consumption (0.321), and resistance (0.361) can be considered moderate; that is, more than 25% of the amount of variance in all the endogenous constructs is explained by the corresponding exogenous constructs. These results are acceptable in the context of research in the behavioral and social sciences ( Hair et al., 2017 ).

Table 3 . Determination coefficients ( R 2 ) and predictive relevance (Q 2 ) of endogenous (omission distance = 7).

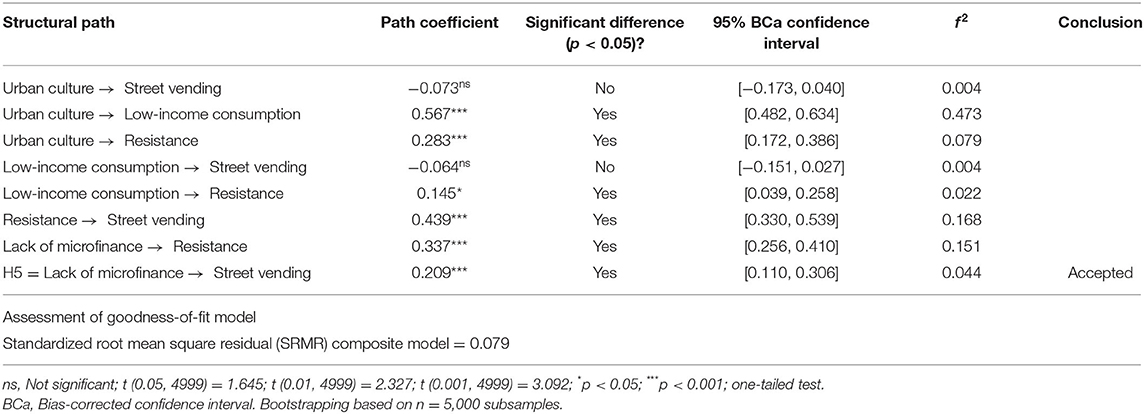

The effect size f 2 assesses how strongly an exogenous variable participates in explaining a target endogenous variable in terms of R 2 . As a rule of thumb, f 2 values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 are weak, moderate, and large, respectively ( Hair et al., 2017 ). Table 5 shows that urban culture has a strong effect size in explaining low-income consumption. Lack of microfinance has a moderate effect on resistance, which is similar to the effect of resistance on street vending. Microfinance, consumption, and culture have weak effects on their target constructs, whereas urban culture and consumption pattern have no effect on street vending.

Even though the data collected reflect the general public's perspective from the capital city of Iraq, the quality of predictive power of the proposed model helps to generalize conclusions and drive managerial implications. To test the predictive relevance of the endogenous variables, we used a blindfolding procedure. Table 3 gives the Q2 values for our endogenous latent constructs. Applying the same rule of thumb used for effect size, we find that street vending has weak predictive power and that the power of low-income consumption and resistance is moderate. All the endogenous variables have Q2 values greater than 0, which provides evidence of the model's predictive relevance ( Geisser, 1974 ; Stone, 1974 ; Hair et al., 2019 ). Accordingly, we can safely generalize the conclusions derived from this study, taking into consideration the limitations raised in section 5.4.

Structural Model Assessment

As an initial step, we used the variance inflation factor (VIF) as an indicator of collinearity in the structural model. Table 4 shows that all the VIF values are below the cut-off value of 3.00. Thus, there are no collinearity issues in the structural model.

Table 4 . Variance inflation factors (VIF) as an indicator of collinearity.

To test the significance of the path coefficients, we ran bootstrapping of 5,000 iterations (subsamples) at 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals. The empirical results for all the direct paths in Table 5 , Figure 2B , are significant, with the exception of the direct effect of urban culture on street vending and low-income consumption on street vending. The former finding suggests that H1 is not supported. The empirical results also show that a lack of microfinance has a positive and significant effect on street vending, which provides support for H5.

Table 5 . Construct effects on endogenous variables.

Figure 2 . Structural model results. (A) Model with total effect. (B) Model with double mediations.

Mediation Analysis

This study followed the updated procedure in Nitzl et al. (2016) to test the mediation hypotheses. Again, the bootstrapping of 5,000 iterations at 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals allowed the indirect effects to be tested. As Figure 2A , Table 6 (A) show, urban culture has a significant total effect on street vending (β = 0.235; t = 3.146). However, when low-income consumption and resistance are introduced as mediators, urban culture no longer has a significant direct effect on street vending (β = −0.073, t = 1.115), as shown in Figure 2B , Table 6 (B). This suggests that H1 is not supported.

Table 6 . Summary of mediating analyses.

The indirect effect of urban culture on street vending via low-income consumption is also not significant (β = −0.036, t = 1.183) as shown in Table 6 (C), and this indicates that H2 is not supported.

As Table 6 (C) shows, the indirect effect of urban culture on street vending via resistance is significant (β = 0.124, t = 3.686). This indicates that resistance fully mediates the relationship between urban culture and street vending, and H3 is therefore supported.

The empirical results in Table 6 (D) suggest that urban culture is positively associated with low-income consumption, that low-income consumption is positively associated with resistance, and that resistance is related to higher levels of street vending. These results suggest that low-income consumption and resistance are two sequential mediators that fully and jointly mediate the influence of urban culture on street vending. Therefore, H4 is supported.

Table 6 (C) shows that the indirect effect of lack of microfinance on street vending via resistance is significant (β = 0.148, t = 4.816). This result suggests that resistance partially mediates the relationship between lack of microfinance and street vending, and H6 is therefore supported.

Discussion and Conclusion

Discussion of the results.

Surprisingly, the results of this study indicate that urban culture does not have a significant direct effect on street vending (H1). Moreover, the indirect effect of urban culture on street vending via low-income consumption (H2) is not significant. Thus, it seems that culture does not impact street vending. These results contradict previous research ( Voiculescu, 2014 ; Tamilarai and Angayarkanni, 2016 ; Alvi and Mendoza, 2017 ; Wibisono and Catrayasa, 2018 ) and the cultural approach ( Williams and Gurtoo, 2012 ; Ladan and Williams, 2019 ). Furthermore, the low-income consumption pattern, which can be considered another dimension of culture, does not impact street vending ( Table 5 ), which again contradicts previous research ( Steel, 2012a ; Trupp, 2015 ; Tamilarai and Angayarkanni, 2016 ).

Nevertheless, we find that urban culture has a significant and positive impact on street vending via resistance (H3). This is a case of full mediation, since there is an indirect effect only. Furthermore, urban culture impacts street vending via serial mediation of low-income consumption and resistance (H4), with no direct effect of urban culture on street vending. In short, urban culture has a significant and positive impact on street vending through sequential mediators and is fully mediated.

We also confirm the direct effect of microfinance on street vending (H5) and the indirect effect through resistance (H6). This is a case of complementary partial mediation, since the direct and indirect effects are both positive and significant. Researchers agree that a lack of microfinance has an impact on the pervasiveness of street vending ( Saha, 2011 ; Lyons, 2013 ; Husain et al., 2015 ). Even though resistance has a direct effect on street vending ( Table 5 ), as previously established ( Musoni, 2010 ; Tengeh and Lapah, 2013 ; Hanser, 2016 ; Boonjubun, 2017 ), the mediating effect of resistance is more important than the direct effect in explaining the pervasiveness of street vending.

Lastly, the results shown in Tables 5 , 6 help to rank the paths in order of importance. First comes the direct effect of resistance on street vending, followed by the total effects of urban culture on street vending, the direct effect of a lack of microfinance on street vending, the indirect effect of microfinance on street vending through resistance, and the indirect effect of urban culture on street vending through resistance, in that order.

Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, it proposes and tests a new and comprehensive model to analyze the relationship between urban culture and street vending, simultaneously examining the effects of culture, consumption, resistance, and microfinance on street vending. Second, it investigates the general public's perceptions of the issue of street vending as a problem facing cities in developing countries, which is a necessary step in reviewing public policies and determining how to deal fairly with street vendors. Third, it develops measurement variables for the constructs in question, some of which are used for the first time, and confirms that they are reliable and valid. Fourth, the statistical analysis contradicts the findings of previous studies and sheds light on the cultural approach by showing that urban culture and low-income consumption (as another dimension of urban culture) have no significant direct effect on street vending. Finally, the study offers three novel and important findings: (1) Urban culture positively influences street vending via resistance; (2) Urban culture impacts street vending via serial mediation of low-income consumption and resistance; (3) Microfinance positively impacts street vending directly or through resistance. These findings are the main contributions of this study, and they will enrich the cultural approach. In short, urban culture (in the form of consumption patterns) impacts the pervasiveness of street vending if we take into consideration the mediator of resistance.

Managerial Implications

Because the predictive relevance of the model has been established, we can safely derive the following managerial implications. The results described in the previous section are of direct relevance to both public entities and scholarly researchers, as they allow the driving factors of the pervasiveness of street vending to be ranked in order of importance: first, resistance; second, urban culture; and third, lack of microfinance (see Tables 5 , 6 ). Resistance is formed by three important observed indicators in sequence, as the standardized factor loadings in Table 1 indicate. First, street vendors develop strategies to enable them to stay on the streets; second, they depend on their social networks; and third, they return to their sites following the demolition of their stalls. Public policy must therefore recognize that the eviction of street vendors from public spaces is not a solution ( Batréau and Bonnet, 2016 ), and policymakers should seek other ways of formalizing street vending.

There are two main factors that shape urban culture: people enjoy walking and communicating in the traditional markets, and they can find interesting items, such as books, in specialized markets. These cultural factors give sellers two sets of incentives to continue trading informally on sidewalks. First, the societal culture, represented by urban culture and patterns of consumption, creates a real demand for the goods and services offered in public spaces, and this encourages sellers to continue trading on the public streets. Second, because they cannot find jobs in the formal sector, street vendors have only one way to earn income, namely by working hard on the streets ( Onodugo et al., 2016 ). In other words, street vendors fulfill their own and their customers' needs, and the culture cannot be changed in the short term.

In terms of lack of microfinance, the most significant factor is that vendors have no access to formal credit facilities. To address this problem, municipal authorities should build infrastructure that is specifically designed to formalize street vendors; for example, they can construct special areas for vendors ( Te-Lintelo, 2017 ) and legalize trading between the informal and formal sectors. The banking sector should be encouraged to adopt a new approach to risk that would enable them to offer loans to microbusinesses ( Malôa, 2013 ), and the public authorities should provide financial support so that poor and unemployed people can set up formal microbusinesses.

We have learned from this research that street vendors are part of the vibrancy of many cities in developing countries. They play an important role in society by providing a range of products to low-income customers. They also help to eliminate poverty and unemployment, enabling people to depend on their own resources when governments fail to tackle those problems ( Onodugo et al., 2016 ). Furthermore, Street vendors cause many problems to traffic flows and suffer from the harmful environment when doing their business such as noise and air pollution. The phenomenon cannot be avoided even the government would evict them from streets and public spaces. The unemployment and poverty immediately pushed them to return. The problem is pervasiveness because at least it has roots in urban culture, consumption patterns, resistance, and lack of microfinance. The best solution to this problematic issue is that the government should invest to formalize the informality of street vending. Therefore, we can increase their contribution to the economic advances and decrease their negative impact on cities.

Limitations and Recommendations for Further Research

Although the path coefficients of the relationship between constructs and the predictive relevance of the entire model are statistically significant, the results of this study are subject to a number of limitations. First, the study uses non-probabilistic sampling with an unlimited population, and the sample of 425 responses can be considered small in the context of the total population of Baghdad. The results would be more accurate if we could increase the sample so that it is more representative of the population as a whole. Second, because we collected the raw data via the Internet and social media, we cannot guarantee the full engagement of the participants. Third, the study relates specifically to the context of Iraq, a country that has suffered recent political instability. Thus, it is important to apply the model to data drawn from other cities and countries with different political circumstances.

Fourth, the model is limited to examination of the impact of culture on street vending. Future research should examine the multivariate impact of other important antecedents of street vending, such as poverty ( Estrada and Hondagneu-Sotelo, 2011 ; Saha, 2011 ), unemployment ( Truong, 2018 ), education ( Williams and Gurtoo, 2012 ; Husain et al., 2015 ), and immigration ( Lapah and Tengeh, 2013 ). The inclusion of the moderating effects of gender, income, and educational background would improve the model conceptually and statistically. Scholars should also revisit the cultural approach and other theories that address street vending and the informal economy ( Williams and Gurtoo, 2012 ; Ladan and Williams, 2019 ). Lastly, the current study is limited to one period. Future studies should, therefore, test the model using data collected at different intervals.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://doi.org/10.17632/dh3cv5p7rv.1 .

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR), King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under grant No. (DF-689-120-1441). The authors, therefore, gratefully acknowledge DSR technical and financial support.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Agadjanian, V. (2002). Competition and cooperation among working women in the context of structural adjustment: the case of street vendors in La Paz-El Alto, Bolivia. J. Dev. Soc. 18, 259–285. doi: 10.1177/0169796X0201800211

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ainsworth-Darnell, J. W., and Downey, D. B. (1998). Assessing the oppositional culture explanation for racial/ethnic differences in school performance. Am. Sociol. Rev. 63, 536–553. doi: 10.2307/2657266

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ali, M. (2021). Imitation or innovation: To what extent do exploitative learning and exploratory learning foster imitation strategy and innovation strategy for sustained competitive advantage??. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 165:120527. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120527

Ali, M., Ali, I., Albort-Morant, G., and Leal-Rodríguez, A. L. (2021a). How do job insecurity and perceived well-being affect expatriate employees' willingness to share or hide knowledge? Int. Entrepreneurship Manag. J. 17, 185–210. doi: 10.1007/s11365-020-00638-1

Ali, M., Ali, I., Badghish, S., and Soomro, Y. A. (2021b). Determinants of financial empowerment among women in Saudi Arabia. Front. Psychol. 12:747255. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.747255

Al-Jundi, S. A., Ali, M., Latan, H., and Al-Janabi, H. A. (2020). The effect of poverty on street vending through sequential mediations of education, immigration, and unemployment. Sustain. Cities Soc. 62, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102316

Al-Jundi, S. A., Shuhaiber, A., and Al-Emara, S. S. (2019). The effect of culture and organisational culture on administrative corruption. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Res. 18, 436–451. doi: 10.1504/IJEBR.2019.103096

Al-Jundi, S. A. (2019). Street vending dataset. Mendeley Data v 1. doi: 10.17632/dh3cv5p7rv.1

Alvi, F. H., and Mendoza, J. A. (2017). Mexico City street vendors and the stickiness of institutional contexts: implications for strategy in emerging markets. Crit. Perspect. Int. Bus. 13, 119–135. doi: 10.1108/cpoib-05-2015-0017

Batréau, Q., and Bonnet, F. (2016). Managed informality: regulating street vendors in Bangkok. City Commun. 15, 29–43. doi: 10.1111/cico.12150

Boonjubun, C. (2017). Conflicts over streets: the eviction of Bangkok street vendors. Cities 70, 22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2017.06.007

Chai, X., Qin, Z., Pan, K., Deng, X., and Zhou, Y. (2011). Research on the management of urban unlicensed mobile street vendors—taking public satisfied degree as value orientation. Asian Soc. Sci. 7, 163–167. doi: 10.5539/ass.v7n12p163

Cuvi, J. (2016). The politics of field destruction and the survival of são paulo's street vendors. Soc. Probl. 63, 395–412. doi: 10.1093/socpro/spw013

Estrada, E. (2016). Economic empathy in family entrepreneurship: Mexican-origin street vendor children and their parents. Ethn. Racial Stud. 39, 1657–1675. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2016.1159709

Estrada, E., and Hondagneu-Sotelo, P. (2011). Intersectional dignities: latino immigrant street vendor youth in Los Angeles. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 40, 102–131. doi: 10.1177/0891241610387926

Esubalew, A. A., and Raghurama, A. (2020). The mediating effect of entrepreneurs' competency on the relationship between Bank finance and performance of micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs). Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 26, 87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.iedeen.2020.03.001

Forkuor, J. B., Akuoko, K. O., and Yeboah, E. H. (2017). Negotiation and management strategies of street vendors in developing countries: a narrative review. SAGE Open 7, 1–13. doi: 10.1177/2158244017691563

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 18, 382–388. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800313

Gefen, D., and Straub, D. (2005). A practical guide to factorial validity using PLS-Graph: tutorial and annotated example. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 16, 91–109. doi: 10.17705/1CAIS.01605

Geisser, S. (1974). A predictive approach to the random effect model. Biometrika , 61, 101–107. doi: 10.1093/biomet/61.1.101

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2017). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.) . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Google Scholar

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., and Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 31, 2–24. doi: 10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Hanser, A. (2016). Street politics: street vendors and urban governance in China. China Q. 226, 363–382. doi: 10.1017/S0305741016000278

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2014). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 43, 115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hummel, C. (2017). Disobedient markets: street vendors, enforcement, and state intervention in collective action. Comp. Polit. Stud. 50, 1524–1555. doi: 10.1177/0010414016679177

Husain, S., Yasmin, S., and Islam, M. S. (2015). Assessment of the socioeconomic aspects of street vendors in Dhaka city: evidence from Bangladesh. Asian Soc. Sci. 11, 1–10. doi: 10.5539/ass.v11n26p1

Ilahiane, H., and Sherry, J. (2008). Joutia: Street vendor entrepreneurship and the informal economy of information and communication technologies in Morocco. J. North Afr. Stud. 13, 243–255. doi: 10.1080/13629380801996570

ILO (2013). The Informal Economy and Decent Work: A Policy Resource Guide Supporting Transitions to Formality . Geneva: International Labour Office, Employment Policy Department.

Khan, E. A. (2017). An investigation of marketing capabilities of informal microenterprises: A study of street food vending in Thailand. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 37, 186–202. doi: 10.1108/IJSSP-09-2015-0094

Khan, E. A., and Quaddus, M. (2020). E-rickshaws on urban streets: sustainability issues and policies. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 41, 930–948. doi: 10.1108/IJSSP-07-2020-0315

Krejcie, R. V., and Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 30, 607–610. doi: 10.1177/001316447003000308

Ladan, U., and Williams, C. C. (2019). Evaluating theorizations of informal sector entrepreneurship: some lessons from Zamfara, Nigeria. J. Dev. Entrepreneurship 24, 1–18. doi: 10.1142/S1084946719500225

Lapah, C. Y., and Tengeh, R. K. (2013). The migratory trajectories of the post 1994 generation of African immigrants to South Africa: an empirical study of street vendors in the Cape Town Metropolitan area. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 4, 181–195. doi: 10.5901/mjss.2013.v4n4p181

Latan, H., and Noonan, R. (eds.). (2017). Partial Least Squares Path Modeling: Basic Concepts, Methodological Issues and Applications . Cham: Springer.

Lyons, M. (2013). Pro-poor business law? On MKURABITA and the legal empowerment of Tanzania's street vendors. Hague J. Rule Law 5, 74–95. doi: 10.1017/S1876404512001030

Malôa, J. C. (2013). Microfinance approach to risk assessment of market and street vendors in Mozambique. Enterprise Dev. Microfinance 24, 40–54. doi: 10.3362/1755-1986.2013.005

Martinez, L., and Rivera-Acevedo, J. D. (2018). Debt portfolios of the poor: the case of street vendors in Cali, Colombia. Sustain. Cities Soc. 41, 120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2018.04.037

Martinez, T. A. (1997). Popular culture as oppositional culture: rap as resistance. Sociol. Perspect. 40, 265–286. doi: 10.2307/1389525

Musoni, F. (2010). Operation murambatsvina and the politics of street vendors in Zimbabwe. J. South. Afr. Stud. 36, 301–317. doi: 10.1080/03057070.2010.485786

Nam, K.-C., Jo, C., and Lee, M. (2010). Meat products and consumption culture in the East. Meat Sci. 86, 95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.04.026

Nani, G. V. (2016). A synthesis of changing patterns in the demographic profiles of urban street vendors in Botswana, South Africa and Zimbabwe. Problems Perspect. Manag. 14, 549–555. doi: 10.21511/ppm.14(3-2).2016.11

Nitzl, C., Roldan, J. L., and Cepeda, G. (2016). Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modelling, Helping researchers discuss more sophisticated models. Indus. Manag. Data Syst. 116, 1849–1864. doi: 10.1108/IMDS-07-2015-0302

OECD/ILO (2019). Tackling Vulnerability in the Informal Economy . Paris: Development Centre Studies, OECD Publishing.

Onodugo, V. A., Ezeadichie, N. H., Onwuneme, C. A., and Anosike, A. E. (2016). The dilemma of managing the challenges of street vending in public spaces: the case of Enugu City, Nigeria. Cities 59, 95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2016.06.001

Palacios, R. (2016). The new identities of street vendors in Santiago, Chile. Space Culture 19, 421–434. doi: 10.1177/1206331216643778

Recchi, S. (2020). Informal street vending: a comparative literature review. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 41, 805–825. doi: 10.1108/IJSSP-07-2020-0285

Recio, R. B., and Gomez, J. E. A. (2013). Street vendors, their contested spaces, and the policy environment: a view from caloócan, Metro Manila. Environ. Urban. ASIA 4, 173–190. doi: 10.1177/0975425313477760

Rehman, N., Mahmood, A., Ibtasam, M., Murtaza, S. A., Iqbal, N., and Molnár, E. (2021). The psychology of resistance to change: the antidotal effect of organizational justice, support and leader-member exchange. Front. Psychol. 12:678952. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.678952

Reid, D. M., Fram, E. H., and Guotai, C. (2010). A study of Chinese street vendors: how they operate. J. Asia Pac. Bus. 11, 244–257. doi: 10.1080/10599231.2010.520640

Reuveni, G. (2002). Reading sites as sights for reading. The sale of newspapers in germany before 1933: bookshops in railway stations, kiosks and street vendors. Soc. History 27, 273–287. doi: 10.1080/03071020210159676

Saha, D. (2011). Working life of street vendors in Mumbai. Indian J. Labour Econ. 54, 301–326.

Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Nitzl, C., Ringle, C. M., and Howard, M. C. (2020). Beyond a tandem analysis of SEM and PROCESS: use of PLS-SEM for mediation analyses! Int. J. Mark. Res. 62, 288–299. doi: 10.1177/1470785320915686

Shujahat, M., Wang, M., Ali, M., Bibi, A., Razzaq, S., and Durst, S. (2020). Idiosyncratic job-design practices for cultivating personal knowledge management among knowledge workers in organizations. J. Knowl. Manag. 25, 770–795. doi: 10.1108/JKM-03-2020-0232

Steel, G. (2012a). Local encounters with globetrotters. Tourism's Potential for Street Vendors in Cusco, Peru. Ann. Tour. Res. 39, 601–619. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2011.08.002

Steel, G. (2012b). Whose Paradise? Itinerant Street Vendors' Individual and Collective Practices of Political Agency in the Tourist Streets of Cusco, Peru. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 36, 1007–1021. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2012.01153.x

Stone, M. (1974). Cross validation and multinomial prediction. Biometrika , 61, 509–515. doi: 10.2307/2334733

Tamilarai, S., and Angayarkanni, R. (2016). Exploring the work life balance of street vendors with reference to tambaram: a township area in Chennai metropolitan city. Int. J. Econ. Res. 13, 1679–1688.

Te-Lintelo, D. J. H. (2017). Enrolling a goddess for Delhi's street vendors: the micro-politics of policy implementation shaping urban (in)formality. Geoforum 84, 77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.06.005

Tengeh, R. K., and Lapah, C. Y. (2013). The socio-economic trajectories of migrant street vendors in Urban South Africa. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 4, 109–128. doi: 10.5901/mjss.2013.v4n2p109

Tonda, N., and Kepe, T. (2016). Spaces of Contention: tension around street vendors' struggle for livelihoods and spatial justice in Lilongwe, Malawi. Urban For. 27, 297–309. doi: 10.1007/s12132-016-9291-y

Truong, V. D. (2018). Tourism, poverty alleviation, and the informal economy: the street vendors of Hanoi, Vietnam. Tour. Recreat. Res. 43, 52–67. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2017.1370568

Trupp, A. (2015). Agency, social capital, and mixed embeddedness among Akha ethnic minority street vendors in Thailand's tourist areas. Sojourn 30, 780–818. doi: 10.1355/sj30-3f

Voiculescu, C. (2014). Voyagers of the smooth space. Navigating emotional landscapes: Roma street vendors in Scotland: “Every story is a travel story–A spatial practice” (De Certeau). Emot. Space Soc. 13, 24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2014.05.003

Wang, L., Ali, M., Kim, H. J., Lee, S., and Hernández Perlines, F. (2021a). Individual entrepreneurial orientation, value congruence, and individual outcomes: Does the institutional entrepreneurial environment matter? Bus. Strategy Environ. 30, 2293–2312. doi: 10.1002/bse.2747

Wang, Y., Dai, Y., Li, H., and Song, L. (2021b). Social media and attitude change: information booming promote or resist persuasion? Front. Psychol. 12:596071. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.596071

Wardrop, J. (2006). Private cooking, public eating: women street vendors in South Durban. Gender Place Cult. 13, 677–683. doi: 10.1080/09663690601019927

Wibisono, C., and Catrayasa, I. W. (2018). Spiritual motivation, work culture and work ethos as predictors on merchant satisfaction through service quality of street vendors in Badung market, Bali, Indonesia. Manag. Sci. Lett. 8, 359–370. doi: 10.5267/j.msl.2018.4.010

Williams, C. C., and Gurtoo, A. (2012). Evaluating competing theories of street entrepreneurship: Some lessons from a study of street vendors in Bangalore, India. Int. Entrepreneurship Manag. J. 8, 391–409. doi: 10.1007/s11365-012-0227-2

Williams, C. C., and Youssef, Y. (2014). Is Informal Sector Entrepreneurship necessity- or opportunity-driven? some lessons from urban Brazil. Bus. Manag. Res. 3, 41–53. doi: 10.5430/bmr.v3n1p41

Yatmo, Y. A. (2009). Perception of street vendors as “out of place” urban elements at day time and night time. J. Environ. Psychol. 29, 467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.08.001

Zhong, S., and Di, H. (2017). Struggles with changing politics: street vendor livelihoods in contemporary China. Res. Econ. Anthropol. 37, 179–204. doi: 10.1108/S0190-128120170000037009

Keywords: street vending, urban culture, consumption, resistance, microfinance, mediation, PLS-SEM

Citation: Al-Jundi SA, Al-Janabi HA, Salam MA, Bajaba S and Ullah S (2022) The Impact of Urban Culture on Street Vending: A Path Model Analysis of the General Public's Perspective. Front. Psychol. 12:831014. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.831014

Received: 07 December 2021; Accepted: 29 December 2021; Published: 14 February 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Al-Jundi, Al-Janabi, Salam, Bajaba and Ullah. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.