- Subscribe to journal Subscribe

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

- Become an ACOEM Member

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Factors Associated With Work-Life Balance and Productivity Before and During Work From Home

Tejero, Lourdes Marie S. PhD; Seva, Rosemary R. PhD; Fadrilan-Camacho, Vivien Fe F. MD, MPH

Technology Transfer and Business Development Office, University of the Philippines Manila (UPM) (Dr Tejero); UPM College of Nursing (Dr Tejero); Industrial and Systems Engineering, Gokongwei College of Engineering, De La Salle University (Dr Seva); Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, College of Public Health (Dr Fadrilan-Camacho), University of the Philippines Manila, Manila, Philippines.

Address correspondence to: Lourdes Marie S. Tejero, PhD, College of Nursing, University of the Philippines Manila, Pedro Gil Street, Manila, Philippines ( [email protected] ).

Funding sources: None.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Ethical consideration: This research protocol was approved in 2020 by the De La Salle University Research Ethics Review Committee (REO protocol code: FAF.007.2019-2020.T2.GCOE).

Clinical Significance: Working from home (WFH) is a prevailing condition globally due to the pandemic. Workers are exposed to job-related and psychosocial factors that can lead to adverse health effects. Such factors should be identified to facilitate targeted preventive actions for promoting work-life balance and productivity while working from home.

Objectives:

Considering the prevailing work from home (WFH) arrangement globally due to COVID-19, this paper aims to compare job-related and psychosocial factors before and during WFH setup; and to determine the relationship of these factors to work-life balance (WLB) and productivity.

Methods:

A total 503 employees from 46 institutions answered the online questionnaire, 318 of whom met the inclusion criteria. Paired t test and structural equation modeling (SEM) with multigroup analysis were used for the statistical analyses.

Results:

Psychological detachment (PD), sleep, stress, social support (SS), WLB, and productivity declined during WFH. SEM showed that PD significantly influenced stress and sleep, subsequently affecting productivity. SS significantly helped the participants maintain WLB.

Conclusion:

The key to increasing productivity and WLB during WFH is to foster PD and SS among employees.

One of the occurrences emanating from the COVID-19 pandemic is the work-from-home (WFH) arrangement on an unprecedented global scale. WFH scheme has revolutionized the way we do our work to achieve the same outcomes that are comparable if not better than previous arrangements. It provided workers with opportunities to manage their time and allocate their resources to achieve organizational objectives. Moreover, WFH reshapes the psycho-social and environmental aspects surrounding one's work, more specifically those in the home setting, which are intimately related to the person.

While WFH arrangement was gaining popularity in the Philippines even before the pandemic, there is limited local data on it as an alternative work arrangement and its impact on health and productivity. During the pandemic, community quarantine measures are enforced that have led to restrictions on business operations to prevent the further spread of COVID-19 in the country. Employers albeit not ready are forced to transition and adapt to the new normal way of operating their businesses. They have adopted WFH arrangements to help minimize the impact of the pandemic on their businesses and employees.

Work-life balance (WLB) is a focal aspect of interest in several research studies about work even before the pandemic forced employees to WFH. Poor WLB is associated to self-reported poor health for both men and women. 1,2 With the advent of WFH schemes dominating the work arrangements worldwide, WLB takes on a different dimension with various factors affecting it, especially in the home setting where the delineation between work and home becomes blurred. Another area of concern in the WFH setting is the issue of productivity. The COVID-19 pandemic forced entire families to stay at home, so the situation and the workplace may not be very conducive to work. The lack of space at home and appropriate office furniture and equipment can also influence the efficiency and safety of employees doing computer-related tasks.

At the beginning of the pandemic, employees were not able to divide their time well because they were used to fixed working hours and specific routines. 3 Workers with families had to take care of children and household chores that may conflict with work-related tasks, thereby reducing the amount of time for productive work. This is especially true for women who have to juggle their time between the demands of their careers and parenting. 4

Literature Review

With most of their employees remotely working at home, companies are interested to know its impact on productivity. 5 Employers are blind to the activities of their employees and rely on information obtained from digital communication and online meetings. Productivity studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic had inconsistent results. Productivity of Chinese employees suffered during the COVID-19 pandemic due to self-regulation issues and problems with technology. 6 Evidently, not all people have the discipline to work without supervision. Interference from family and bouts of loneliness can affect the performance of tasks during WFH. Most researchers in Hungary working from home spent more time at work but were less efficient because of their inability to collaborate with their colleagues. 7 Although technology can support virtual meetings the need for immediate consultation and feedback is not possible in the WFH setting. However, knowledge workers in Europe found that WFH is more efficient because it minimizes unproductive time on meaningless tasks at work and allows them to focus on their job. These differences support further investigation of factors affecting productivity in the WFH environment.

Although productivity may suffer during WFH, it can potentially help promote work-life balance (WLB). Working at home allows parents to spend more time with their children and the high job autonomy (JA) and scheduling flexibility can help minimize work–family conflict. 8 Greater autonomy in determining working hours and managing tasks improved the productivity of employees that worked from home due to COVID-19. 6 JA is defined as “the extent to which work can provide great freedom, independence and discretion of the individual in work scheduling and determine the procedures to be used in implementing them.” 9 Mache et al, 10 found that the freedom to choose working hours minimizes the perception that the job is mentally demanding. However, autonomy has negative effects on people that do not have a high level of discipline. It caused them to slow down and not achieve their goals.

Not all employees that WFH achieve WLB because it depends on the atmosphere at home and the support provided by family members. 11 During the COVID-19 pandemic, workload affected work–home balance among Chinese employees that worked from home during its early stages. 12 Professional women with children may find working at home more challenging because of the greater demand for caring. Women are expected to take care of children with little help from the husband. 13 Young internet on-line workers, on the other hand, reported a significantly lower satisfaction with WLB and a higher negative work–home interaction because they spent more time at work. 14 The competing demands of work and family life can create stress and anxiety for some workers. Working from home blurs the boundaries between work and personal time. Employees that are not able to establish boundaries from work to non-work have poor psychological detachment (PD). 15

PD implies not thinking about work or doing work-related duties at home. 16 It is one of the significant predictors of well-being because some work situations can be unsettling and worrisome. It was found to have a significant negative effect on stress among employees working from home due to COVID19. 17 PD is related to employee engagement at work. Highly engaged employees find it difficult to distance themselves from their work. Sonnentag et al, 18 discovered that striking a balance between work and leisure is crucial in promoting employees’ well-being. The use of information and communication technology (ICT) while working from home can affect PD because it was found to be disruptive to sleep. Boundary crossing between work and family does not necessarily affect sleep quality or consistency unless there is a problem with PD. 19

Work-related difficulty in sleeping has been related to inability to detach from work. For WFH employees, the use of electronic devices is a job requirement to facilitate communication. Employees with high work-related smartphone use experience ego depletion when dealing with self-control demands at work. Sleep quality, however, attenuates this interaction. In cases of high sleep quality, next-day self-control processes at work are no longer affected by work-related smartphone use. 20 Sleep pattern is also related to productivity at work. Productivity of Korean nurses was adversely affected by poor sleep quality due to shiftwork. 21 Although shiftwork may not apply to people working from home, the disruption of schedule and working hours extending until late at night can also lead to poor sleep quality.

Sleep disorder and stress are very common work-related health problems. 22 Job stress is defined as something in the work environment that is perceived as threatening or something in the workplace which gives an individual an experience of discomfort. 23 It is the psychological and physical state that results when the resources of the individual are not sufficient to cope with the demands and pressures of work situations or family affairs or both. Studies showed that it is a significant determinant of employee productivity and performance. 24–26 It is a major problem for such employees that fail to balance the competing demands of work and family. It significantly influenced the productivity of employees without spouses and young employees that WFH. 17 Social support provided by family members and superiors, however, dampens the effect of stress and promotes quality of work life. 26,27 Employees that receive adequate support also showed high levels of productivity. 28 Social support (SS) of supervisors and colleagues minimizes the strain among employees because it cushions the effect of work–family conflict. 29 Work from home employees during the COVID-19 pandemic cited SS as a means to overcome loneliness and feelings of isolation. 12 It is associated with job satisfaction, work–family enrichment and mediates the relationship between stress and job satisfaction. 30 Low supervisor and coworker support had been associated with tiredness and sleeping difficulties. 31

Keeping employees productive and healthy are important concerns of companies that allowed their employees to work from home due to the COVID19 pandemic. There is a dearth of literature on the level of employee productivity before and during the pandemic. Since all family members were forced to work at home to prevent the spread of the virus, the current situation cannot be compared with earlier studies of productivity on employees working from home. All family members had to share the space at home so work distraction is inevitable. Productivity and WLB is affected by factors related to the conflicting demand between work and family and the support system available to the employee. Thus, this paper aims to compare job-related and psychosocial factors before and during WFH setup and determine the relationship of job-related and psychosocial factors to WLB and productivity. The hypothesized relationships among the variables are shown in Fig. 1 . This research query helps delineate the drivers to productivity and WLB while WFH. In doing so, employees as well as employers are guided which aspects to focus on towards the attainment of higher productivity while maintaining a healthy WLB, thereby harnessing employees’ full potential. Comparing the WFH set up with the prior arrangement, that is, working in the office, establishes a baseline comparator to evaluate the WFH productivity and WLB. Thus, this gives more credence in determining the desirability of WFH scheme and how to make the most out of it especially during the pandemic.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Participants and data collection tool.

The study utilized convenience sampling of employees from various institutions belonging to different industries in the Philippines. Study participants were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) used computer while working from home (2) worked from home for at least 2 months.

The authors identified institutions that are part of their network representing various industries. They wrote to the administrators of these institutions to invite their employees to participate in the online survey, not only for research purposes but also to promote health, safety, and productivity while on WFH through a webinar conducted for them at the end of the data gathering. The self-administered online questionnaire utilized in the study was pretested among 10 employees from various business establishments. The questionnaire was revised according to the assessment findings of the pre-test. The first part of the questionnaire is on sociodemographic data while the succeeding parts are questions pertaining to the measures of interest in this study before and during WFH. The authors sent the online questionnaire with a corresponding cover letter to the administrators and employees of participating institutions.

Anonymity and confidentiality were ensured in the administration and handling of the data. The study was given ethics approval in 2020 by the De La Salle University Research Ethics Review Committee (REO protocol code: FAF.007.2019-2020.T2.GCOE).

The three items on PD were taken from the Recovery Experience Questionnaire. 16 The scale used showed good psychometric properties. 32 The items included were “I forget about work after working hours,” “I don’t think about work at all outside working hours,” and “I distance myself from work.” Scale ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating higher PD.

The question to evaluate sleep quality (SQ) was “How do you evaluate this night's sleep?” It was taken from Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index 33 and was rated on a 5-point rating scale ranging from 1 (very bad) to 5 (very good). 34

Social support (SS) was assessed with three questions taken from the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQII) using a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always): “How often do you get help and support from your colleagues?”; “How often are your colleagues willing to listen to your work -related problems at work?”; and “How often do your colleagues talk with you about how well you carry out your work?”

JA was measured in terms of decision-making autonomy using a 5-point likert scale 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The three questions were based on the Work Design Questionnaire 35 : “The job gives me a chance to use my personal initiative or judgment in carrying out the work”; “The job allows me to make a lot of decisions on my own”; and “The job provides me with significant autonomy in making decisions.”

Workload perception (WLD) was measured with three items from the Kurz-fragebogen zur Arbeitsanalyse (KFZA) instrument 36 using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (seldom or 1% to 25% of the time) to 5 (always or 76% to 100% of the time). The questions included were “Do you have to do overtime?”; “Is your workload unevenly distributed so it piles up?”; and “How often do you exceed required work hours?”

The three questions for stress (STR) were taken from the subscale in the second version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire-COPSOQ II. 37 Problems in relaxing, irritability, and tension are the aspects of STR that were asked. Items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (seldom or 1% to 25% of the time) to 5 (always or 76% to 100% of the time). Research supports the psychometric qualities of the scale. 32

The scale to evaluate work-life balance (WLB) was based on three items from the work-life conflict scale. 38 The first one considers the effect of work on personal life. The second item pertains to personal matters which make work challenging. Lastly, the third question is how personal life can drain a person's energy. The respondents scored questions on WLB from 1 (seldom or 1% to 25% of the time) to 5 (always or 76% to 100% of the time).

An item on self-reported productivity (PROD) was scored from 1 (strongly Disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The item was adapted from a web-based survey determining the characteristics and outcomes of telework. 39

STATA 15.0 (StataCorp SE, College Station, TX) was used for descriptive data analysis. Categorical variables were summarized using frequency and proportion. The normality distribution of continuous variables was determined using Shapiro-Wilk test. Mean and standard deviation (SD) were used to summarize continuous quantitative data that met the normality assumption while median and range were used for continuous data that were not normally distributed.

Paired t tests to compare means before and during WFH were done using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS). Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to determine the relationships among the factors affecting work-life balance and productivity. Results with P -value of <0.05 are considered statistically significant. Multigroup analysis was done to assess relationships among variables before and during WFH. Since PD, SS, JA, WLB, WLD, and STR were not directly measurable, these were estimated using various indicators classifying these as latent variables. Relationships between the latent variables and the relationships of other observed variables were assessed using SEM.

The SEM model was assessed using several goodness-of-fit statistics such as root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and comparative fit index (CFI). Model fit was considered to be good if: RMSEA less than 0.05, TLI and CFI more than or equal to 0.90. Data preparation and all statistical analyses for the SEM were done with SPSS 21.0 (IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY) and AMOS 21.0 (IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY).

The management of a total of 46 business establishments, academic institutions, and government agencies agreed to have their employees participate in this study. Based on the inclusion criteria, 318 responses were included in the analysis from a total of 503 study participants that answered the online survey. Of the 503 participants, 26 did not WFH, 18 were not computer-users, 59 started WFH even before the pandemic, 48 only answered the section on sociodemographic profile, and 34 did not accomplish the section pertaining to their working conditions prior to the pandemic.

T1 shows the sociodemographic profile of the study participants including their occupational level and the type of industry where they belong. The median age of the study participants is 33.5 years, ranging from 21 to 64 years. Majority of the participants are women (61.64%) and single (58.49%).

| Demographic Characteristic | % | |

| Age, yrs | Median: 33.5; range: 21–64 | |

| 21–30 | 123 | 38.68% |

| 31–40 | 84 | 26.42% |

| >40 | 111 | 34.91% |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 122 | 38.36% |

| Female | 196 | 61.64% |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 186 | 58.49% |

| Married | 123 | 38.68% |

| Separated/Divorced | 6 | 1.89% |

| Widowed | 3 | 0.94% |

| Length of working from home, months | Median: 7; range: 2–10 | |

| Less than 6 months | 62 | 19.50% |

| At least 6 months | 256 | 80.50% |

| Number of people in the household | Median: 5; range: 1–18 | |

| 1–5 | 213 | 66.98% |

| 6–10 | 97 | 30.50% |

| >10 | 8 | 2.52% |

| Number of children less than 18 in the household | Median: 1; range: 0–7 | |

| 0 | 147 | 46.52% |

| 1–3 | 161 | 50.95% |

| 4–7 | 8 | 2.53% |

| Living with a partner/spouse | 148 | 46.54% |

| Smoker | 23 | 7.23% |

| Has any diagnosed illness | 69 | 21.70% |

| Works for the government | 78 | 24.53% |

| Industry | ||

| Education | 122 | 38.36% |

| Government Administration/Relations | 35 | 11.00% |

| Information Technology | 28 | 8.81% |

| Human Resource | 23 | 7.23% |

| Banking and Finance | 13 | 4.09% |

| Manufacturing | 12 | 3.77% |

| Health and Fitness | 10 | 3.14% |

| Marketing and Sales | 7 | 2.20% |

| Intellectual Property | 7 | 2.20% |

| Business Process Outsourcing | 6 | 1.89% |

| Research | 6 | 1.89% |

| Others | 49 | 15.41% |

| Occupational level | ||

| Top management | 7 | 2.20% |

| Upper middle management | 33 | 10.38% |

| Lower middle management | 68 | 21.38% |

| Semi-managerial | 41 | 12.89% |

| Non-managerial | 169 | 53.14% |

Results also show that 7 months is the median duration of working from home among the study participants. Five is the median number of people in the household, up to a maximum of 18. While one child is the median number of children less than 18 years old with a maximum of seven children. Almost half (46.54%) of the participants are living with a partner or spouse. There are 21.70% who have comorbidities while 7.23% of the participants are smokers.

In terms of occupational level, most of the participants belong to the non-managerial level (53.14%) while the least belong to the top management (2.20%) level. The top three industries where the study participants are employed are education (38.36%), government administration (11.00%), and information technology (8.81%).

T2 presents the mean differences of the variables while on WFH set-up during the pandemic compared with before WFH, that is, while working in the office or institution. All the three measures for PD show that participants are less able to detach themselves from work while WFH. Results also show that the participants’ quality of sleep is worse during WFH. Findings for stress indicate that participants have more problems in terms of relaxation, irritability, and tension while WFH. The same trend is observed with WLB and PRO wherein the measures for these two factors indicate worse conditions where the study participants have poor WLB and low productivity during WFH. For the job-related factors, social support from coworkers is significantly less on all measures during WFH set-up. Conversely, there is no significant difference for job autonomy on all measures before and during WFH. As for workload perception, only measures on overtime and exceeding required work hours are significantly increased on WFH.

| Before | During | Paired Differences | ||||||

| Variables | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Value | |

| Psychological detachment | ||||||||

| I forget about work after working hours. | 3.15 | 1.12 | 2.49 | 1.15 | –0.65 | 1.38 | –8.44 | <0.001 |

| I don’t think about work at all outside working hours. | 3.08 | 1.10 | 2.33 | 1.10 | –0.75 | 1.22 | –10.86 | <0.001 |

| I distance myself from work. | 3.21 | 1.11 | 2.52 | 1.04 | –0.70 | 1.18 | –10.48 | <0.001 |

| Sleep | ||||||||

| How do you evaluate the quality of your sleep when you are working from home? | 3.49 | 0.91 | 3.33 | 1.09 | –0.16 | 1.40 | –2.01 | 0.05 |

| Social support | ||||||||

| How often do you get help and support from your colleagues? | 3.84 | 0.92 | 3.42 | 1.01 | –0.42 | 0.92 | –8.09 | <0.001 |

| How often are your colleagues willing to listen to your work-related problems at work? | 3.88 | 0.87 | 3.70 | 0.97 | –0.18 | 0.77 | –4.21 | <0.001 |

| How often do your colleagues talk with you about how well you carry out your work? | 3.70 | 0.97 | 3.37 | 1.00 | –0.33 | 0.88 | –6.65 | <0.001 |

| Job autonomy | ||||||||

| The job gives me a chance to use my personal initiative or judgment in carrying out the work. | 3.90 | 0.66 | 3.92 | 0.76 | 0.03 | 0.71 | 0.64 | 0.53 |

| The job allows me to make a lot of decisions on my own. | 3.76 | 0.71 | 3.75 | 0.84 | –0.02 | 0.73 | –0.39 | 0.7 |

| The job provides me with significant autonomy in making decisions. | 3.69 | 0.73 | 3.62 | 0.85 | –0.07 | 0.68 | –1.91 | 0.06 |

| Workload perception | ||||||||

| Is your workload unevenly distributed so it piles up? | 3.01 | 1.00 | 2.97 | 1.02 | –0.04 | 0.87 | –0.84 | 0.40 |

| Do you have to do overtime? | 2.90 | 1.11 | 3.06 | 1.21 | 0.16 | 1.15 | 2.45 | 0.02 |

| How often do you exceed required work hours? | 2.99 | 1.07 | 3.24 | 1.16 | 0.26 | 1.09 | 4.16 | <0.001 |

| Stress | ||||||||

| How often have you had problems relaxing? | 2.91 | 0.87 | 3.23 | 0.90 | 0.32 | 1.05 | 5.45 | <0.001 |

| How often have you been irritable? | 2.76 | 0.79 | 3.02 | 0.89 | 0.26 | 0.93 | 4.94 | <0.001 |

| How often have you been tense? | 2.88 | 0.89 | 3.12 | 0.96 | 0.24 | 1.02 | 4.24 | <0.001 |

| Work–life balance | ||||||||

| I miss personal activities because of work. | 2.54 | 1.08 | 2.82 | 1.20 | 0.29 | 1.14 | 4.54 | <0.001 |

| I find it hard to work because of personal matters. | 2.15 | 0.90 | 2.47 | 1.00 | 0.31 | 0.95 | 5.88 | <0.001 |

| My personal life drains me of energy for work. | 2.15 | 0.87 | 2.33 | 1.02 | 0.18 | 0.86 | 3.79 | <0.001 |

| Productivity | ||||||||

| I feel productive in doing my work | 4.15 | 0.81 | 3.86 | 0.80 | –0.30 | 1.07 | –4.98 | <0.001 |

Structural Equation Modeling

The relationships of the factors in the model were analyzed using SEM. The composite reliabilities of the constructs are PD = 0.65, SS = 0.73, JA = 0.75, WLB = 0.60, and STR = 0.60. The multivariate normality of data was also established.

Data obtained from the survey included ratings before and during the WFH set-ups, thus, 2 groups of data were included in the analysis of the structural model using multigroup analysis. The overall model fit statistics indicate a good fit to the data (chi-square/d.f. = 3.41; RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.90; TLI = 0.88).

T3 summarizes the maximum likelihood estimates of path coefficients, standard error, and P values calculated before and during WFH. Relationships between variables in the model were shown by the path coefficients. The results indicated that PD significantly influences STR and SQ. Employees who are not able to forget and distance themselves from work experience higher STR and poor SQ both before and during WFH. SS significantly helps the participants maintain WLB, especially colleagues’ willingness to listen to work-related problems. However, SS only affects stress during WFH. Employees who have low social support are more stressed in a WFH set-up. JA does not affect STR or WLB but significantly affects PRO while working from home. Those who experience high job autonomy are more productive during WFH. SQ also has a significant effect on PRO for both situations while SS only affects PRO before WFH where employees who have social support felt productive before WFH. STR has no significant effect on PRO both before and while WFH.

| Before WFH | During WFH | |||||||

| Path | S.E. | S.E. | ||||||

| STR | <--- | PD | −0.20 | 0.04 | −0.20 | 0.04 | ||

| STR | <--- | SS | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.60 | −0.12 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| STR | <--- | JA | −0.07 | 0.06 | 0.24 | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.63 |

| SQ | <--- | PD | 0.23 | 0.07 | 0.39 | 0.07 | ||

| WLB | <--- | SS | −0.12 | 0.06 | 0.03 | −0.22 | 0.07 | |

| WLB | <--- | JA | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.56 | −0.12 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| SQ | <--- | STR | −0.52 | 0.11 | −0.82 | 0.13 | ||

| PRO | <--- | SQ | 0.28 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.02 | |

| PRO | <--- | SS | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.71 |

| PRO | <--- | JA | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.27 | 0.08 | |

| PRO | <--- | STR | −0.01 | 0.11 | 0.92 | −0.13 | 0.13 | 0.31 |

Several factors affect productivity while working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Perceived workstation suitability helps improve productivity whereas stress adversely affects it among younger people and those without spouses. On the other hand, workstation ergonomic suitability and musculoskeletal symptoms have no significant effect on productivity. 17

Comparing WFH versus pre-pandemic office work set-up, WFH is shown to pose more challenges as indicated by the respondents. PD is more difficult to attain while on WFH since there is no physical distinction between work and home obligations. Traveling to and from the office acts as a natural boundary between work and home which disappeared in WFH. Boundary setting is a helpful mechanism in attaining PD 40 but is challenging to establish in WFH where family obligations may get intertwined with one's work. When one is unable to psychologically detach oneself from work, one experiences a higher stress level. 41 This is supported by the results of this study where there is increased stress level with decreased PD.

PD has the largest effect on STR in the structural model before and during WFH. With work being done at home without the clearly defined work hours, job-related concerns constantly recur in the mind from rising to bedtime, thus increasing the stress level. As for the respondents’ workload, they work beyond their working hours and often go on overtime while on WFH. Workload contributes to stress and affects job performance. 42 Furthermore, PD was shown to moderate the effects of job demands on burnout and depression. 43 Without the defined boundaries between work and home, one easily drifts to one's job while at home. Company superiors, expecting employees to be at home, schedule meetings even late at night. Work can also pile up for employees that are not disciplined enough to work during normal working hours and work until late hours at night. Chinese employees working at home from various industries during the COVID-19 outbreak experienced many work interruptions at home that negatively affect their work effectiveness. 6

Another difference between WFH and working in the office is the SS which is markedly reduced on WFH as shown in this study. In the structural equation model, SS affected STR but only during WFH. Being physically present in the office facilitates communication among colleagues ranging from official meetings to casual dealings with officemates during work hours and breaktimes. Often, the latter dealings are avenues to listen and show support, give feedback, and align expectations. Perceived social support was shown to affect WLB while working in the office. 44 On WFH, such dealings are difficult to attain, save a call or message. Online meetings focus on business related discussions. Psychological needs are not met due to the isolation brought about by working from home. 6 This is felt more acutely in cultures where people are used to social gatherings and interactions that characterize most of the respondents in this study. This reduced SS further contributes to increasing STR. With increased STR, SQ suffers 45 as shown in this study. A person gets preoccupied with anxious thoughts while under STR, thereby overwhelming the mind with concerns, depriving it of the needed sleep. This study showed that PD and STR have significant influence on SQ before and during WFH. The path coefficients show that the effect on SQ is more pronounced during WFH which may be attributed to prolonged preoccupation about job concerns until the night especially for those who are unable to establish boundaries between work and personal life during WFH.

There are many factors affecting PRO, but we only considered the effects of SQ, SS, JA and STR in the structural equation model. Of all these factors, SQ is the only one that has a significant effect to PRO before and during WFH. A person who does not get enough sleep experiences fatigue and impairments in performance manifested by decreased attention and memory function. 46 It is interesting to note that the impact of SQ to PRO is greater prior to WFH as shown in the SEM results. Moreover, in the comparison of means, participants reported better sleep before WFH. Since our participants are not shiftworkers, work time did not affect their SQ prior to WFH. They follow the usual routine of working in the morning and sleeping at night. However, during the pandemic, this routine was disrupted as employees were given the flexibility to work at their own time. This has led to extending working hours at night 6 which is congruent with their reported increase in work hours and overtime during WFH. Catching sleep in the morning may be difficult especially for married employees and those with children that are also confined at home.

JA only affected PRO significantly during WFH. The flexibility given to employees in carrying out their tasks at home influences their feeling of being productive. The WFH situation forced many process changes to continue business operations. The autonomy given to employees to customize their methods to suit the situation positively contributes to their PRO. Although ratings of PRO are lower during WFH than prior, JA proved to be a crucial means of allowing the respondents to cope with the new setup. This is consistent with other research findings where job autonomy and self-leadership are correlated with productivity during WFH. 47 Considering the various factors present in the home environment affecting productivity that are totally different from those in the office, job autonomy fosters initiative in exploring ways to enhance productivity in a different or even unfavorable setting. Unlike JA, SS only affected PRO significantly before WFH. Face to face interactions prior to WFH allows employees to quickly resolve work-related issues because they are all in one place and it is easy to seek help from colleagues. This may not be the case during WFH where it is difficult to ask help due to scheduling of meetings and technology problems. SS also significantly influenced WLB before and during WFH. Although there is limited SS in the WFH setting, it still influenced WLB. This is consistent with a study of academics in Malaysia that showed that support from coworkers and supervisors predict work-life balance. 48 The assistance provided by colleagues at work, with all the constraints imposed by WFH, seemed to help maintain WLB of employees.

WLB suffers during WFH. With difficulties distancing oneself from work, increased stress, reduced social support, more overtime, etc, there is hardly quality time for personal life. Moreover, productivity is likewise reduced in WFH, despite more hours put into one's work. The cyclical effect of stress 49 is supported in this study.

Several limitations of the study are identified. External validity should be treated with caution since we have a small sample of heterogenous group of participants with varying demographic characteristics. Moreover, productivity was measured using only one question and as reported by the respondents which are subjective to the respondents’ contexts. Also, WLB and STR have low composite reliabilities which may be due to the variation in the context on how the questions on the said variables are interpreted by the respondents.

CONCLUSIONS

This study has shown that job-related and psychosocial factors declined significantly during WFH compared with working in the office previously. WLB and PRO suffered during WFH. Among the factors affecting PRO, SQ registered the highest impact which in turn was greatly affected by STR. Among the factors affecting STR, PD had the highest effect. Moreover, the path PD-SQ-PRO is significant, making SQ the mediating variable between PD and PRO. Hence, the key to increasing PRO during WFH is to foster PD among employees. Setting boundaries facilitate PD which is established by the employees themselves and from employers or supervisors by ensuring protected time for work as well as for personal life. Moreover, SS significantly affected WLB both before and during WFH. Hence, fostering SS among employees is highly beneficial. Data on job-related and psychosocial factors will aid policy-makers and employers to plan and implement targeted interventions that will promote work-life balance and productivity among employees while working from home.

Acknowledgments

Appreciation and gratitude to the 46 institutions that participated in this research.

- Cited Here |

- Google Scholar

COVID-19; productivity; social support; structural equation modeling; work from home; work load; work-life balance

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

Association of sleep, work environment, and work–life balance with work..., working from home during the covid-19 pandemic: the association with work..., work from home during the covid-19 outbreak: the impact on employees’ remote....

Advertisement

Work from home - A new virtual reality

- Published: 29 January 2022

- Volume 42 , pages 30665–30677, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Neha Tunk 1 &

- A. Arun Kumar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4048-6389 2

10k Accesses

12 Citations

Explore all metrics

The present study aims to contribute to the research of future possibility of Work from Home (WFH) during the pandemic times of Covid 19 and its different antecedents such as job performance, work dependence, work life balance, social interaction, supervisor’s role and work environment. A structured questionnaire was adopted comprising of 19 questions with six questions pertaining to work related infrastructure at home. Data was collected from 138 full time employees working from home which revealed the influence of work dependence, work environment and work life balance which were hypothesized to be directly related to the willingness to work from home in future if given an opportunity. Qualitative analysis revealed that job performance, social interaction and supervisor’s role related hypothesis are refuted. The study tries to bridge the gap between the existing research done in past during normal course of time and current pandemic. The current research of WFH during the Covid 19 in employees working from home in India is an attempt to assess the antecedents in current situation. These results have important theoretical and practical implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Virtuality in Non-governmental Organizations: An Analysis from Working Conditions

Work from Home and its Impact on Lifestyle of Humanoid in the Context of COVID-19

The Impact of Work from Home (WFH) on Workload and Productivity in Terms of Different Tasks and Occupations

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The threat of a Covid 19 cataclysm has greatly increased over the past few months. The recent Covid 19 outbreak has brought the world to a standstill. Soon after the emergency was declared by the World Health Organization (WHO), all the nations including India began to enforce stringent rules of lockdown in order to curtail the spread of the deadly virus. All the offices, schools, manufacturing units, organizations, shopping malls, markets except healthcare and essential services were shutdown with a view to break the chain of spread. World is reeling in the midst of the novel corona-virus (COVID-19) pandemic with fear of rising death toll due to the deadly virus. Soon after WHO declared the COVID 19 as a pandemic, the Government of India has announced a complete lockdown. In this pandemic situation people from all over the world are facing difficulty to do work in the work place. It has advised companies to implement work from home policy for their staff as part of encouraging social distancing to curb spread of novel corona virus infection.

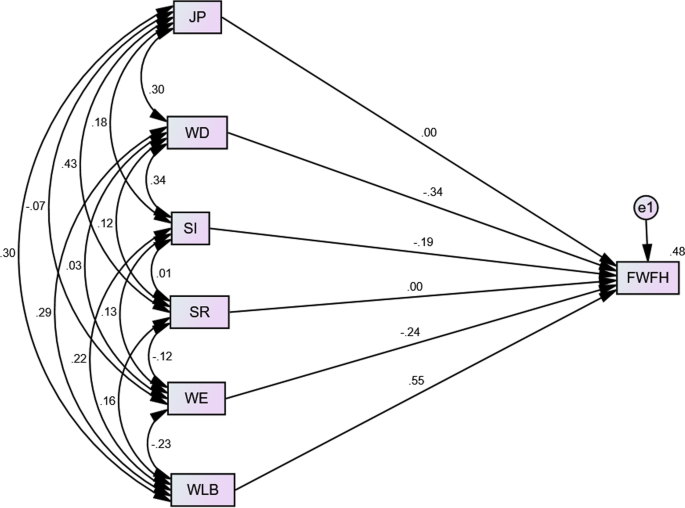

Hypothesis testing results with SEM

Six factor model of work from home

Due to the unprecedented circumstances, the employees from all the sectors have been impacted significantly. The social distancing and the self-isolation measures imposed by the Government has brought basic structural changes in the way employees work in organizations. Work from home these days has become the need of the hour for most of the working population in the contemporary way of work life and has become common for many employees around the globe (Vilhelmson & Thulin, 2016 ). The office workspace is now combined with the personal space. This has brought a mammoth change in the way employees work. The digital transformation and the virtual workspace have made the employees work together despite located in distinct places. The research conducted by Windeler et al. (Windeler et al., 2017 ) shows that maintaining a certain level of social interaction is important for employees’ functioning when they work from home. Extensive research has been done earlier which centred on the influence of work from home on employee performance (Allen et al., 2015 ; Bailey & Kurland, 2002 ; De Menezes & Kelliher, 2011 ; Gajendran & Harrison, 2007 ; Martínez Sánchez et al., 2007 ). Whereas some studies have also shown that working from home leads to better performance (Allen et al., 2015 ; Vega et al., 2014 ), others warn that working from home leads to social and professional isolation that confines knowledge sharing (Crandall & Gao, 2005 ; Arun Kumar & Shekhar, 2020 ) and leads to the intensification of labour (Felstead & Henseke, 2017 ; Kelliher & Anderson, 2009 ).

Previous researchers focused on working from home (Baker et al., 2007 ). Due to strong surge in employment of women and growing dual earners, flexible working has become important for balanced work and personal life (Russell et al., 2009 ). In modern times, employees have started to adopt various technologies to interconnect devices at home. The influence of technology on the routine home life is studied in earlier research (Grinter et al., 2005 ). Innovative technology and telecommunication have increased the possibility of working from the home. Work from home settings for the employee’s quality of working life were discussed in the earlier studies (Shamir & Salomon, 1985 ). The extensive review of literature has revealed that home office has positive influence and traditional office has negative influence on work life balance when job related factors and family related factors in three work settings namely traditional office, virtual office and home office was studied (Hill et al., 2003 ). Research of work from home during pandemic or emergency is limited due to the sudden upheaval it has created in the recent times.

In this paper an attempt is made to study the various factors related to willingness to work from home in future and its impact on performance, supervision, social interactions with teams. This study also attempts to study the relationship between various factors relating to WFH during the pandemic. It even attempts to study the effect of isolation from the physical workspace and the challenges encountered by the employees working in virtual workspace during the pandemic.

The corona virus pandemic popularly known as Covid 19 has left many employees confined to their homes. The present study focuses on the need arising due to corona pandemic across the world which has further restricted movement across different places during the lockdown. During this period the employees were asked to work from home without affecting organization’s productivity at the same time ensuring social distancing measures which were followed during the lockdown. The present study is trying to access the willingness and the future possibility of WFH as a post pandemic measure. This study shows our preparedness for the next level of new normalcy of virtual workspace. As a precautionary measure if there is an additional requirement to further curtail the movement of people or in order to cut down certain costs without effecting the productivity, the organizations may prefer employees to continue work from home. This study helps the organizations to understand the challenges and the preparedness of future contingencies.

Methodology

Respondents and research approach.

In this cross-sectional study, people from India were requested to participate in the study. Respondents were contacted and requested to fill the questionnaire online through google forms in WhatsApp. The participants were assured of anonymity and confidentiality of data. Their prior consent and willingness to participate in survey was taken. Both female and male respondents were included in the study. The study aimed to examine educated and qualified young professionals within the working age group working from home during the Covid 19 crisis. The convenient sampling technique was implied for collecting the data. Respondents were included in this study only if they were willing to respond. In total, more than 200 questionnaires were distributed. 138 of the total respondents accepted to participate in the study. The response rate for the study was calculated to be 70% which is sufficient to conduct the further analysis. All the participants who filled the form were employees working from home due to lockdown restrictions imposed by the nation, in order to break the chain of transmission of novel corona virus (Covid 19). The field work of the study was conducted during June to December 2020. Each section had several questions related to a particular construct. The first section in the questionnaire consisted of the basic demographic information of the participants, which includes age, gender, marital status, children, educational level and whether they were willing and able (whether they had the infrastructure) to work from home.

To provide the current status of WFH during lockdown comprehensively, the respondents were asked to answer the questions divided into 7 parts which are work related infrastructure at home, job performance, work dependence, work life balance, social interactions, supervisor’s role, work environment and willingness to work from home in future (Shown in Appendix Table 1 ).

Work from home practices in pandemic COVID-19 situation demonstrates multifaceted phenomena. The aim of this paper is to gain deeper insight of willingness to work from home post COVID-19. This paper is based on primary data as well as secondary data. The survey method was adopted to conduct the study. Based on the review of literature and the researcher’s understanding of the concept, a structured questionnaire was adopted.

The questionnaire consisted of 6 demographic questions, 6 pertaining to work infrastructure and 19 questions related to the core essence of the study (See Appendix Table 1 ). Questions on work related infrastructure at home was borrowed from the study done by Garg & van der Rijst, 2015 with slight modifications. The reliability of the questionnaire was checked by calculating the Cronbach’s Coefficient Alpha value (See Table 2 ). This value depicts the reliability of a single uni-dimensional latent construct. The Cronbach’s Coefficient Alpha of the overall scale for this study was calculated to be 0.708. A Cronbach’s coefficient alpha value of 0.60 was suggested as threshold for the Cronbach’s alpha reliability and acceptability (Pallant, 2013 ). This confirmed the internal consistency of the current study.

Job Performance

Job Performance was measured using three item scale used by Raghuram et al. ( 2001 ); Sims et al. ( 1976 ). This scale was also used by Garg and van der Rijst ( 2015 ). The sample question for job performance is “The measures of my job performance are clear.” One question pertaining to this has been added by the authors though not in scale as it is relevant for analysis “Employee engagement is more during the lock down”. Each item was measured using 5-point Likert scale with 1 as strongly disagree and 5 as strongly agree. The Cronbach alpha value for Job Performance is 0.75.

Work Dependence

Work dependence was measured using three item scale used in study done by Sims et al. ( 1976 ). The sample item is “My performance does not depend on working with others.” The scale items are anchored with strongly disagree as 1 and strongly agree as 5. The Cronbach alpha value for Work dependence is 0.84.

Work Life Balance

Work life balance during lockdown was measured using three item scale developed for the purpose of study. The sample questions are “Overall I am comfortable” (not considered due to model fit issues), “I am able to balance both work and household during the lock down” and “I feel it is difficult to maintain work life balance as I have to remain available all the time”. Each item was measured using 5-point Likert scale with 1 as strongly disagree and 5 as strongly agree. The Cronbach’s alpha value for this factor is 0.75.

Social Interaction

Social interaction was measured using three item scale used by Raghuram et al. ( 2001 ). This scale was also used by Garg and van der Rijst ( 2015 ). The sample item is “The work-related meetings in my office are adequate to build good working relationships”. The scale is anchored with 1 as strongly disagree and 5 as strongly agree. The Cronbach’s alpha value for this factor is 0.642.

Supervisors Role

Supervisor’s role was measured using three item scale developed for the purpose of study. The sample question is “My superior is very supportive in addressing problems during the lock down”. Each item was measured using 5-point Likert scale with 1 as strongly disagree and 5 as strongly agree. The Cronbach’s alpha value for this factor is 0.781.

Work Environment

Work environment was measured using three item scale used by Fonner and Roloff ( 2010 ). This scale was also used by Garg and van der Rijst ( 2015 ). The sample item is “I am distracted by other things going on in my work environment, such as background noise?”. The scale is anchored with 1 as strongly disagree and 5 as strongly agree. The Cronbach’s alpha value for this factor is 0.66.

Willingness to Work from Home in Future

The dependent variable willingness to work from home in future (FWFH) post covid crisis was measured using single item “I feel post pandemic also work from home permits should be given”. This was measured using 5-point Likert scale with 1 as strongly disagree and 5 as strongly agree.

Data Synthesis

To test the hypothesized model, a Structural Equation Model (SEM) was used. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 28) and Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS 28) was used for the study. The research analysis was conducted using two-step approach. Measurement model and Structural models were tested. The measurement model was checked for validity, internal consistency and reliability. To test the scale items Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was used. Present study reported Comparative Fit index (CFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Root Mean Residuals (RMR). The six latent constructs of the measurement model are tested to check if all the coefficients indicate FWFH. The coefficient values show that work dependence, work life balance and work environment are significant determinants of FWFH.

Extensive literature review has revealed the existing models developed by various researches. The Model framework proposed by Nordin et al., 2016 is as under. Previous research findings and the model framework set by Nordin et al., 2016 was studied. The change in the circumstances advocate the need for supplementary variables to the existing model. We would like to study the moderating effect of pandemic lockdown on employee preference to WFH post pandemic.

H1: There is a positive influence of job performance on employee’s willingness to FWFH

As it is identified by many researchers and evident from the previous literature that job performance is one of the essential components in the study of work from home. The authors Garg and van der Rijst ( 2015 ) have studied the relationship between the job performance and professional isolation. Job performance and work from home are related and are inter dependent. When there is clear understanding of job performance and when the job indicators are quantifiable, work from home possibility is more even after pandemic. Therefore, it is hypothesized as there is a positive influence of job performance on work from home in future.

H2: There is a negative influence of work dependence on employee’s willingness to FWFH

In past research was directed towards the importance of telecommuting and increasing work dependence (Vana et al., 2008 ). The study made by Garg and van der Rijst ( 2015 ) found that work dependence had a weak positive relation to experience with virtual work. The focus of present study is to assess the willingness of employees to work from home post pandemic. The present study is during the peculiar times of Covid 19 which makes the concept of WFH a unique one.

H3: There is a negative influence of social interaction on employee’s willingness to FWFH

Another important component of factors influencing willingness to work from home in future (FWFH) is Social Interaction. Previous studies (Baumeister & Leary, 1995 ) have highlighted that work from home with less social interaction in employees will make them aggravated due to isolation. Mintz-Binder & Allen, 2019 observed the factor social contact in terms of virtual meetings and online interactions. Many researchers in the past have focussed on the need to maintain firm and well-built interpersonal social relationships. There exists a negative influence of social interaction on work from home in near future.

H4: There is a positive influence of supervisor’s role on employee’s willingness to FWFH

Raghuram and Fang ( 2014 ) have studied the role of the supervisor in controlling the employees working from home. Previously Lautsch et al. ( 2009 ) have studied the general perceptions regarding supportiveness of supervisors. Madlock ( 2012 ) has studied the leadership styles and their results suggested that supervisors occupied in work oriented more than relational oriented leadership style in the virtual workplace.

H5: There is a negative influence of work environment on employee’s willingness to FWFH

According to Wheatley ( 2012 ), work from home eliminates the workplace related distractions and allows to work productively without interruptions. The results of the present study are in agreement with the study conducted by Golden ( 2007 ) which pointed out that the virtual technology like e-mail and online-conferences to interact with other employees lack the warmth and social presence of face-to-face interaction.

H6: There is a positive influence of work life balance on employee’s willingness to FWFH

Study conducted by Venkatraman et al. ( 1999 ) emphasised that working overtime informally without any extra payment affects the personal life of the employees. The study conducted by Tietze and Musson ( 2010 ) elicits that balance between work and home is essential to understand the relationship between household and professional life. The results of the present study agreed with a balanced work and family life will have greater willingness to work from home. Thus, the proposed hypothesis is that there is a positive influence of work life balance on the employee’s willingness to work from home in future (FWFH).

Demographic Profile of Respondents

The study consisted of 138 participants working from home during the lockdown. 21% of respondents were female whereas 79% were male. The largest group 58% fall in the age group of 18–25 years, 34% of respondents were in 26–35 years of age group and 36–45 years of the age group is represented by 8% in the current study. The largest group 50% are Professionals (None of them are front end medical workers), 24% are IT software employees and others represent 26% (Design engineers, BPO employees and backend support). In terms of the highest educational qualification, 45% of participants were degree/diploma holders, 40% were postgraduates and 16% were holding a professional qualification. None of them were below graduation level, the group is mature.

Data Screening

The responses were complete in all aspects. There is no missing data in the columns. Also, observed quite normally distributed data of our latent factors and other variables like job performance, work dependence, social interaction, supervisor’s role, work environment and work life balance. To measure the multivariate normality, kurtosis and skewness measures were used which was generated using AMOS 26. The data exhibited normal distribution which ranged from −1.3 to 2.04. The threshold value for Kurtosis and Skewness is −2 to +2 (Byrne, 2010 ). However, the value of 2.04 does not violate the normality. The threshold is 3.3 according to Skarpness, 1983 . This number indicates a good fit. Multivariate Analysis was suggested by Hu & Bentler, 1998 as an indication of goodness of fit. The multivariate measure in the study is 15.472 at critical ratio 1.298. The data is perfectly well behaved.

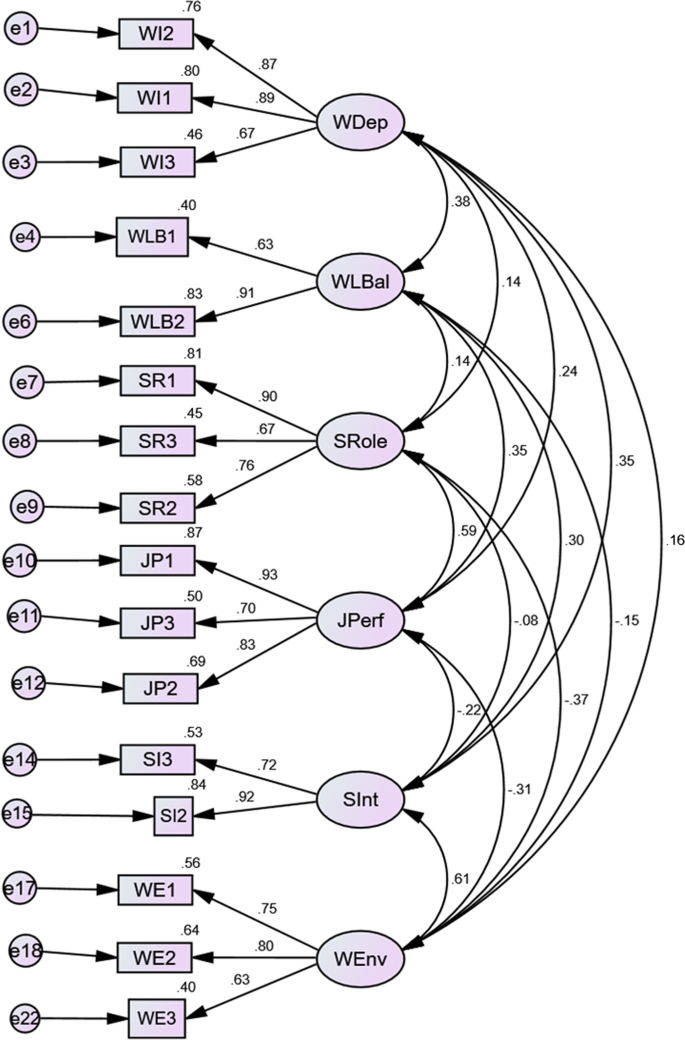

The present study has attempted to explore the structural relationship between the multiple factors relating to Work from Home. Questions were measuring the variables on five point Likert scale. This was run in SPSS 28 using Varimax with Normalization method for rotation. The rotation and iteration were run until the ultimate clear pattern matrix arrived. The factor patterns arrived under each column were thoroughly diagnosed to understand the plausible cross-loadings of factors and elimination of redundant variables (Brown & Moore, 2012 ). Six factors were identified under different heads like job performance (JP), work dependence (WD), work life balance (WLB), social interaction (SI), supervisor’s role (SR) and work environment (WE). These six factors explained were calculated from the sum of squared loadings from the structure matrix. The total accumulated variance explained is 71.709% for work from home during pandemic. The total variance explained by first factor job performance is 13.65%, the second factor work dependence is 13.656%, work life balance is 12.965, social interaction is 12.450, supervisor’s role is 10.392 and work environment is 8.998. Absolute values below 0.5 were eliminated. During the principal axis factoring, few items cross loaded on another component and few items in scale were deleted due to low factor loadings. An item in the job performance scale “There are objective criteria by which my performance can be evaluated” was cross loaded on supervisor’s role component during factor analysis. Third item in work life balance was deleted due to poor loading. The rotation converged in 7 iterations. Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant at 000 indicating the result was acceptably valid. In addition to this, the model fit indices were verified for the proposed factor structure. The CFA result yielded an adequate fit. The CMIN = 164.268, CMIN/df = 1.711, CFI = 0.922, RMSEA = 0.08, RMR = 1.55 (See Appendix Table 3 ). The overall model exhibited a good fit. The Harman single factor test was used for examining if the problem of common method variance (CMV) exists or not. All the factors have not significantly loaded on a single factor. This test confirms that CMV is not a significant problem in this study.

The job performance scaled on three measures. It is easy to measure and quantify employee performance (with path coefficients = 0.932), the measures of employee job performance are clear (with path coefficients = 0.829), the feeling that employee engagement is more during the lockdown (with path coefficients = 0.704). The hypotheses that there exists a positive influence of job performance on employee’s willingness to WFH in future is refuted with estimate of 0.003 at p value greater than 0.05. There is a negative influence of work dependence on employee’s willingness to WFH in future. In this factor three aspects of work dependence are measured, the extent to which the employee performance depends on working with others (with path coefficients 0.892), the need to work independently for performing the best (with path coefficients 0.872), the nature of work in terms of independent task or projects (with path coefficients 0.675). All three are significant with p value less than 0.05. However, the study has revealed the negative influence of Work Dependence on employee’s willingness to work from home in future post pandemic situation. It may be inferred that the higher degree of WFH is associated with weakened work dependence. This is due to the inter-dependence of departments for work completion. Like for example, the dependence on IT department for setting up remote access to all the employees for completion of work during the sudden lockdown. Next, social interaction was measured. The first item, social interactions are more in the current lock down situation (deleted due to low loadings), The work-related meetings in my office are adequate to build good working relationships (with path coefficient 0.915), the social events in virtual office are adequate to build a sense of community (with path coefficient 0.725). The research hypotheses relating to negative influence of social interaction on employee’s willingness to WFH in future is refuted in the current study. The relationship between social interaction and willingness to WFH in future is −0.193 at p value greater than 0.05. Thus, we refute the hypothesis.

The results of the present study hypothesize that there is a positive influence of supervisor’s role on employee’s willingness to WFH in future has been refuted. In the present study focused on three aspects of supervisory role. The first being close supervision of work during the lockdown (with path coefficients 0.902). Secondly, employees understanding on the criteria for evaluating the performance was studied (with path coefficients 0.760). Lastly, the support extended by the superior in addressing problems during the lockdown (with path coefficients 0.673) was studied. The supervisor’s role estimated −0.002 at p value more than 0.05. Thus, hypothesis is rejected under study that there is a positive influence of supervisor’s role on employee willingness to WFH in future.

Hypothesis results have revealed that there is a significant negative influence of work environment on employee’s willingness to WFH in future (with path coefficients −0.245). In this factor, three aspects of work environment were measured, the interruption caused when colleagues talk in virtual meetings (with path coefficients 0.746) and the distraction caused by other things going on in the work environment, such as background noise (with path coefficients 0.802) and feeling of pressure because meetings take away from work (with path coefficients 0.632) are measured under this head. Moreover, it consumes lot of productive time to effecting work particularly for the complex type of tasks. It may be inferred that the higher degree of willingness to WFH is associated with weakened work environment.

Work life balance is measured using three items. Overall comfort working from home (with path coefficient 0.630), employee’s ability to balance both work and household during the lock down (with path coefficient 0.909) and feeling of difficulty in maintaining work life balance due to the pressure of remaining available all the time (deleted due to low loadings). There is a positive influence of work life balance on employees willingness to WFH in future with regression estimate of 0.546 at p value less than 0.05. It may be inferred that higher degree of work life balance has an incremental effect on willingness to WFH.

Assessment of Reflective Model

Reliability analysis.

Cronbach Alpha was used to assess the inter item consistency between measurement variables. Cronbach’s Alpha for all the factors put together was 0.708. Post factorization, the Cronbach’s Alpha for job performance was 0.750, work dependence was 0.844, work life balance was 0.75, social interaction was 0.64, superior’s role was 0.781 and work environment was 0.66. All these values are above 0.6 indicating acceptable internal consistency (Nunnally, 1978 ). Next, Composite Reliability (CR) was assessed. CR values ranged from 0.753 to 0.865 higher than minimum requirement of 0.7 (see Appendix Table 4 ).

Convergent Validity

Convergent validity was assessed using Average Variance Explained (AVE). The AVE values ranged from 0.533 to 0.684 higher than 0.5 threshold. The factor loadings exceeded 0.5 minimum requirement (Fornell & Larcker, 1981 ). Thus, Convergent Validity was assured.

Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity is assured by comparing the square root of AVE and inter-correlations between other constructs as exhibited in Appendix Table 5 . The diagonal bold numbers in the table indicate square root of AVE and the non-diagonal numbers are the correlations between constructs signifying discriminant validity.

Content Validity

It is very important to take utmost care while designing the questionnaire. The questionnaire was simple in its structure and the language used was easy to understand. This was principally designed to get better content validity.

Structural Model Testing

Hypothesis testing.

In the structural model analysis, multi-dimensional model was hypothesised and tested for significance. While testing the objectives under the study, it was encountered that three out of six path coefficients were considered statistically significant. Work dependence (with path coefficients −0.345), work environment (with path coefficients −0.245), work life balance (with path coefficients 0.546) are significantly related to employee willingness to WFH in future post pandemic. While job performance, social interaction and supervisor’s role are not statistically significant (See Appendix Table 6 ).

As predicted in Hypothesis 2, work dependence is negatively associated with FWFH (β = −0.345, p < 0.05). Hypothesis 5, work environment is negatively associated with FWFH (β = −0.245, p < 0.05). Hypothesis 6, work life balance is negatively associated with FWFH (β = 0.546, p < 0.05). Hypothesis 2, 5 and 6 are supported.

Unexpectedly, Hypothesis 1 that states that there exists a positive influence of job performance on FWFH was not supported. Hypothesis 3, that there is a negative influence of social interaction on FWFH was also not supported. Finally, Hypothesis 4, that there is a positive influence of supervisor’s role on FWFH was also not statistically significant (See Fig. 1 )

Number of variables relating to work infrastructure at home, work dependence, virtual meetings, supervision, performance, social interactions with co-workers, challenges encountered and work life balance were measured in this study (See Fig. 2 ). Based on the availability of work related infrastructure at home during lock down, this part of the survey tries to access the willingness and the future possibility of WFH if required. 82% of respondents confirmed that they are ready to work from home if they are given an opportunity and if such situations demand in future. Moreover, 82% had confirmed that they have internet connection at home, 50% of total respondents confirmed that they have air-conditioning at home, 60% respondents confirmed that they have separate space to work from home, 79% of participants opined that their home office were silent. 87% had computer/laptop/headphones and other accessories required for WFH. This indicates that most of them have access to basic work related infrastructure. It also indicates the future possibility of work from home. 79% of respondents agree that they felt there is a close supervision of work during the lockdown out of which 29% of respondents strongly agreed. This indicates that the amount of supervision over their work has increased comparatively. 76% agreed that they felt that employee engagement is more during the lock down out of which 26% of them strongly agreed. None of them strongly disagreed that employee engagement is more during lockdown.

In perceived organizational support, the survey made an attempt to study the superior’s support towards the team members in addressing various work related problems during the remote working scenario. It has been observed that superiors strongly support their teams when they confront any problems relating to work. Majority of them 83% agreed that they have a very supportive work environment out of which 23% of participants strongly agreed. Moreover, 71% agreed that social interactions were must, whereas 7% denied its importance. However, 21% were neutral.

The social events in virtual offices needs to be adequate to build a sense of community and break the social isolation among the teams. 61% agreed that they had adequate social events with co-workers in virtual office whereas 29% of them were neutral and only 10% of participants complained of not having adequate social events.

With respect to the adequacy of work related meetings, 68% of the participants agreed that the work-related meetings in the virtual office were adequate. This indicates that most of the employees working from home are closely connected through work related meetings. This is a good indicator of building a work relationship even during the lockdown in-spite of physical isolation. Only 5% feel that there are not much adequate interactions in terms of work related team meets as before.

Team meetings are a great way to come together with the colleagues and clients both inside and outside of the organization. The online platforms which are being commonly used in Indian scenario are zoom, google meet, webex, microsoft teams, go to meeting, kaizala and skype other service providers which they agreed to be very effective tools for managing virtual teams. However, it is also observed that certain problems and challenges with respect to internet connectivity, server issues, call drops, hacking and data insecurity during the lockdown were encountered. The study found that 55% of respondents agreed that messaging and chat has improved the team effectiveness. This study has revealed the role of technology in building the virtual workspace. Another problem which has surfaced during the study is the fact that the pressure to be available online all the time has affected the work life balance. 63% of participants agreed that post pandemic also work from home permits should be given. Thus, 63% of employees are comfortable with work from home.

The evidence conferred suggests that WFH is on the whole beneficial to both organizations and its employees. Majority of the respondents agreed to WFH post pandemic with clarity on their performance indicators and enhanced productivity, it can be concluded that WFH during the pandemic is an overall WIN-WIN situation for the employees and the corporate (Garg & van der Rijst, 2015 ). However, home space has become the work area affecting the overall work life balance with long working hours, pressure to be available all the time. In conclusion, the tech problems associated with remote working due to unpreparedness with respect to COVID 19 cataclysm has contributed to the existing challenges of the employees and organizations. It has also been observed that remote working has built a pressure on the home networks which led to frequent interruption in the regular working. Moreover, hacking and data security threats have added to the existing problems. Poor network quality coupled up with frequent call drops, server and connectivity problems are few more issues noticed.

With this, it can be concluded that despite all these challenges faced by the employees the exemplary attitude of employees towards WFH is commendable. It has been observed that majority of respondents have agreed to WFH post lockdown which truly exhibits the spirit to cooperate and abide by the nations call towards adhering to the timely health guidelines without affecting the productivity.

The current seismic circumstances are directing organizations and its employees into a new era of WFH. Employee engagement and supervision coupled alongside supervisor’s support is the only way ahead. Catching up formally and informally through conference calls is the only mode to build teams effectiveness and team inclusion without compromising the productivity and the work enthusiasm is the new reality.

Implications of the Study

The change in the place of working calls for the attention of the labour laws. The Government needs to redefine the existing labour laws in the country. The traditional laws related to workplace requires to be replaced with the changing needs of WFH. This calls for framing of new HR policies in organisations in order to ensure perfect work life balance.

Limitations of Study and Scope for Further Research

Nevertheless, the present study has limitations. The study is limited to a small group of participants of private organizations including young educated working professionals, IT software employees, design engineers, BPO employees and backend support employees working from home. In this study, employees working in essential services and health care were excluded. The recommended future direction for research would be to study using a feasibly larger sample of survey and test the validity. The study is social desirability response bias. Although the anonymity was assured to the respondents there could be a possibility of bias in participation. Social desirability response bias in self report research as pointed out by authors Van de Mortel ( 2008 ) may have transpired. The present study calls for the attention of researchers towards WFH in educational sector and challenges of smart teaching and learning. The impact of WFH and professional isolation on physical and mental well-being should also be further investigated in order to develop preparedness of management during contingencies.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Allen, T. D., Golden, T. D., & Shockley, K. M. (2015). How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Association for Psychological Science, 16 , 40–68.

Google Scholar

Bailey, D. E., & Kurland, N. B. (2002). A review of telework research: Findings, New Directions, and Lessons for the Study of Modern Work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23 , 383–400.

Article Google Scholar

Baker, E., Avery, G. C., & Crawford, J. (2007). Satisfaction and perceived productivity when professionals work from home. Research and Practice in Human Resource Management, 15 (1), 37–62.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin . https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Brown, T. A., & Moore, M. T. (2012). Confirmatory factor analysis. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of structural equation modeling, 361–379. The Guilford Press.

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (multivariate applications series) . Taylor & Francis Group.

Crandall, W. R., & Gao, L. (2005). ‘An update on telecommuting: Review and prospects for emerging issues’, S.A.M. Advanced Management Journal, 70 , 30–37.

De Menezes, L. M., & Kelliher, C. (2011). Flexible working and performance: A systematic review of the evidence for a business case. International Journal of Management Reviews, 13 , 452–474.

Felstead, A., & Henseke, G. (2017). Assessing the growth of remote working and its consequences for effort, Well-being and Work-life Balance. New Technology, Work and Employment, 32 , 195–212.

Fonner, K. L., & Roloff, M. E. (2010). Why teleworkers are more satisfied with their jobs than are office-based workers: When less contact is beneficial. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 38 (4), 336–361.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error . Algebra and statistics.

Gajendran, R., & Harrison, D. (2007). The good, the bad and the unknown about telecommuting: Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92 (6), 1524–1541.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Garg, A. K., & van der Rijst, J. (2015). The benefits and pitfalls of employees working from home: Study of a private company in South Africa. Corporate Board: Role, Duties and Composition . https://doi.org/10.22495/cbv11i2art3

Golden, T. (2007). Co-workers who telework and the impact on those in the office: Understanding the implications of virtual work for co-worker satisfaction and turnover intentions. Human Relations . https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726707084303

Grinter, R. E., Edwards, W. K., Newman, M. W., & Ducheneaut, N. (2005). The work to make a home network work. ECSCW 2005 - Proceedings of the 9th European Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work.

Hill, E. J., Ferris, M., & Märtinson, V. (2003). Does it matter where you work? A comparison of how three work venues (traditional office, virtual office, and home office) influence aspects of work and personal/family life. Journal of Vocational Behavior . https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(03)00042-3

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to Underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods . https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424

Kelliher, C., & Anderson, D. (2009). Doing more with less? Flexible working practices and the intensification of work. Human Relations, 63 , 83–106.

Kumar, A. A., & Shekhar, V. (2020). SCL of knowledge in Indian universities. Journal of the Knowlege Economy, 11 , 1043–1058. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-019-00592-6

Lautsch, B. A., Kossek, E. E., & Eaton, S. C. (2009). Supervisory approaches and paradoxes in managing telecommuting implementation. Human Relations . https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709104543

Madlock, P. E. (1970). The Influence of Supervisors' Leadership Style On Telecommuters. Journal of Business Strategies, 29 (1), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.54155/jbs.29.1.1-24 .