What is Human Rights Education?

Human Rights Education is all about equipping people with the knowledge, skills and values to recognize, claim and defend their rights. Various Human Rights organizations and representatives have defined human rights education in their own ways. Here are some of the most prominent definitions:

“ Education, training and information aimed at building a universal culture of human rights . A comprehensive education in human rights not only provides knowledge about human rights and the mechanisms that protect them, but also imparts the skills needed to promote, defend and apply human rights in daily life. Human rights education fosters the attitudes and behaviours needed to uphold human rights for all members of society. ” (United Nations World Programme)

“ Through human rights education you can empower yourself and others to develop the skills and attitudes that promote equality, dignity and respect in your community, society and worldwide. ” (Amnesty International)

“ Human rights education builds knowledge, skills and attitudes prompting behavior that upholds human rights. It is a process of empowerment which helps identify human rights problems and seek solutions in line with human rights principles. It is based on the understanding of our own responsibility to make human rights a reality in our community and society at large. ” (Navi Pillay, former United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights)

“ Human rights education means education, training, dissemination, information, practices and activities which aim, by equipping learners with knowledge, skills and understanding and moulding their attitudes and behaviour, to empower them to contribute to the building and defence of a universal culture of human rights in society, with a view to the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms. ” (Council of Europe)

Why is Human Rights Education Important?

Human Rights Education is important for many reasons. Below are some of the most frequently mentioned reasons why human rights education is important.

- Human Rights Education is crucial for building and advancing societies

- Human Rights Education empowers people to know, claim and defend their rights

- Human Rights Education promotes participation in decision making and the peaceful resolution of conflicts

- Human Rights Education encourages empathy, inclusion and non-discrimination

Often abbreviated as “HRE,” human rights education is also an essential tool for human rights awareness and empowerment. Many teachers don’t label their curriculum as “human rights education,” but they include features of HRE. Educational frameworks that consider non-discrimination, gender equality, anti-racism, and more help build an understanding and respect for human rights. Students learn about their rights, history, and their responsibility as citizens of the world.

In 2011, the General Assembly adopted the United Nations Declaration for Human Rights Education and Training . It called on countries to implement human rights education in every sector of society.

Here are ten more reasons why human rights education is important:

#1 It enables people to claim their rights

This is the most obvious benefit of HRE. In the “Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals, Groups, and Organs of Society to Promote and Protect Universally Recognized Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms,” Article 6 states that everyone has the right to know about their rights. By receiving that education, people can identify when rights are being violated and stand up to defend them.

#2 It teaches young people to respect diversity

When young people are exposed to human rights education, it teaches them to respect diversity from an early age. This is because no matter the differences between people – race, gender, wealth, ethnicity, language, religion, etc. – we all still deserve certain rights. Human rights also protect diversity. The earlier people learn about this, the better it is for society.

#3 It teaches history

Understanding history through a human rights lens is critical to a good education. If human rights weren’t included, lessons would be incomplete. Learning about human rights through history challenges simple and biased narratives. It teaches students the origins of human rights, different historical perspectives, and how they evolved to today. With this foundation in history, students better understand modern human rights.

#4 It teaches people to recognize the root causes of human rights issues

By recognizing the roots of problems, people are better equipped to change things. As an example, it isn’t enough to know that homelessness is a human rights issue. To effectively address it, people need to know what causes homelessness, like low-paying jobs and a lack of affordable housing. Studying history is an important part of identifying the roots of human rights issues.

#5 It fosters critical thinking and analytical skills

HRE doesn’t only provide information about human rights. It also trains people to use critical thinking and analyze information. Many human rights issues are complicated, so one of HRE’s goals is to teach people how to think. Students learn how to identify reliable sources, challenge biases, and build arguments. This makes human rights discussions more productive and meaningful. Critical thinking and analysis are important skills in every area of life, not just human rights.

#6 It encourages empathy and solidarity

An important piece of human rights education is recognizing that human rights are universal. When people realize that and then hear that rights are being violated elsewhere, they are more likely to feel empathy and solidarity. The violation of one person’s rights is a violation of everyone’s rights. This belief unites people – even those very different from each other – and provokes action.

#7 It encourages people to value human rights

When people receive human rights education, what they learn can shape their values. They will realize how important human rights are and that they are something worth defending. People who’ve received human rights education are more likely to stand up when they believe their rights (and the rights of others) are being threatened. They’ll act even when it’s risky.

#8 It fuels social justice activities

If people didn’t know anything about human rights, positive change would be rare. When people are educated and equipped with the necessary skills, they will work for social justice in their communities. This includes raising awareness for the most vulnerable members of society and establishing/supporting organizations that serve basic needs. With HRE, people feel a stronger sense of responsibility to care for each other. Believing in social justice and equality is an important first step, but it often doesn’t move far beyond a desire. HRE provides the knowledge and tools necessary for real change.

#9 It helps people support organizations that uphold human rights

Knowing more about human rights and activism helps people identify organizations that stand up for human rights. It also helps them avoid organizations (e.g. corrupt corporations) that directly or indirectly disrespect rights. These organizations are then forced to change their practices to survive.

#10 It keeps governments accountable

Human rights education doesn’t only encourage people to hold organizations accountable. It encourages them to hold governments accountable, as well. Human rights experts say that HRE is critical to government accountability. Armed with knowledge, skills, and passion, citizens have the power to challenge their governments on issues and demand change. HRE also helps provide activists with resources and connections to the global human rights community.

You may also like

15 Inspiring Quotes for Black History Month

10 Inspiring Ways Women Are Fighting for Equality

15 Trusted Charities Fighting for Clean Water

15 Trusted Charities Supporting Trans People

15 Political Issues We Must Address

15 Trusted Charities Fighting for LGBTQ+ Rights

16 Inspiring Civil Rights Leaders You Should Know

15 Trusted Charities Fighting for Housing Rights

15 Examples of Gender Inequality in Everyday Life

11 Approaches to Alleviate World Hunger

15 Facts About Malala Yousafzai

12 Ways Poverty Affects Society

About the author, emmaline soken-huberty.

Emmaline Soken-Huberty is a freelance writer based in Portland, Oregon. She started to become interested in human rights while attending college, eventually getting a concentration in human rights and humanitarianism. LGBTQ+ rights, women’s rights, and climate change are of special concern to her. In her spare time, she can be found reading or enjoying Oregon’s natural beauty with her husband and dog.

COMPASS Manual for Human Rights Education with Young people

Introducing human rights education.

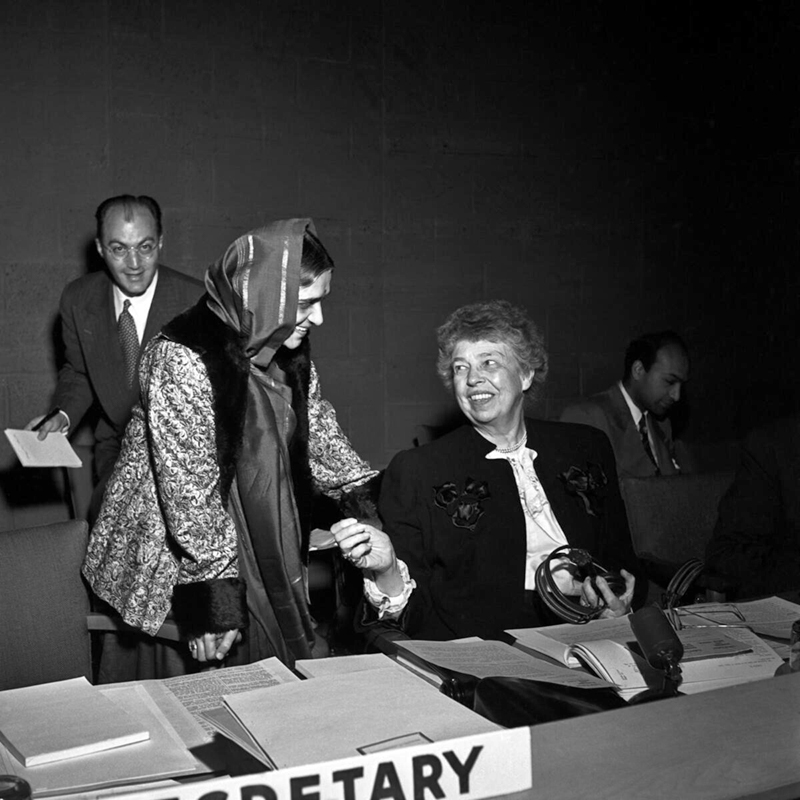

"Every individual and every organ of society … shall strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms." Preamble to The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948.

"Teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms" is the foundation of human rights education (HRE). However, before looking at what human rights education is and how it is practised, it is necessary to clarify what "these rights and freedoms" are that HRE is concerned with. We begin, therefore, with a short introduction to human rights.

- What are human rights?

How can people use and defend human rights if they have never learned about them?

Throughout history every society has developed systems to ensure social cohesion by codifying the rights and responsibilities of its citizens. It was finally in 1948 that the international community came together to agree on a code of rights that would be binding on all states; this was the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Since 1948 other human rights documents have been agreed, including for instance the European Convention on Human Rights in 1950 and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) in 1990.

Human rights reflect basic human needs; they establish the basic standards without which people cannot live in dignity. Human rights are about equality, dignity, respect, freedom and justice. Examples of rights include freedom from discrimination, the right to life, freedom of speech, the right to marriage and family and the right to education. (There is a summary and the full text of the UDHR in the appendices).

Human rights are held by all persons equally, universally and for ever. Human rights are universal, that is, they are the same for all human beings in every country. They are inalienable, indivisible and interdependent, that is, they cannot be taken away – ever; all rights are equally important and they are complementary, for instance the right to participate in government and in free elections depends on freedom of speech.

How can people use and defend human rights, and use and defend them if they have never learned about them? The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) acknowledges this in its preamble, and in Article 26 it gives everyone the right to education that should "strengthen respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms". The aim of human rights education is to create a world with a culture of human rights. This is a culture where everyone's rights are respected and rights themselves are respected; a culture where people understand their rights and responsibilities, recognise human rights violations and take action to protect the rights of others. It is a culture where human rights are as much a part of the lives of individuals as language, customs, the arts and ties to place are.

- Defining human rights education

Since 1948 a huge quantity and variety of work has been – and is being – done in the interests of human rights education. That there are many ways of doing HRE is as it should be because individuals view the world differently, educators work in different situations and different organisations and public bodies have differing concerns; thus, while the principles are the same, the practice may vary. In order to get a picture of the variety of teaching and activities that are being delivered, it is instructive to look at the roles and interests of the various "individuals and organs of society" in order to see how these inform the focus and scope of their interest in HRE.

In 1993 the World Conference on Human Rights declared human rights education as "essential for the promotion and achievement of stable and harmonious relations among communities and for fostering mutual understanding, tolerance and peace". In 1994 the General Assembly of the United Nations declared the UN Decade of Human Rights Education (1995-2004) and urged all UN member states to promote "training dissemination and information aimed at the building of a universal culture of human rights". As a result, governments have been putting more efforts into promoting HRE, mainly through state education programmes. Because governments have concern for international relations, maintaining law and order and the general functioning of society, they tend to see HRE as a means to promote peace, democracy and social order.

Educational programmes and activities that focus on promoting equality in human dignity

The purpose of the Council of Europe is to create a common democratic and legal area throughout the whole of the European continent, ensuring respect for its fundamental values: human rights, democracy and the rule of law. This focus on values is reflected in all its definitions of HRE. For example, with reference to its commitment to securing the active participation of young people in decisions and actions at local and regional level, the Human Rights Education Youth Programme of the Council of Europe defines HRE as "...educational programmes and activities that focus on promoting equality in human dignity 1 , in conjunction with other programmes such as those promoting intercultural learning, participation and empowerment of minorities."

The Council of Europe Charter on Education for Democratic Citizenship and Human Rights Education (2010) 2 defines HRE as education, training, awareness raising, information, practices and activities which aim, by equipping learners with knowledge, skills and understanding and developing their attitudes and behaviour, to empower learners to contribute to the building and defence of a universal culture of human rights in society, with a view to the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms.

There are other definitions of human rights education, such as the one of Amnesty International: HRE is a process whereby people learn about their rights and the rights of others, within a framework of participatory and interactive learning.

The Asia-Pacific Regional Resource Centre for Human Rights Education makes particular reference to the relation between human rights and the lives of the people involved in HRE: HRE is a participative process which contains deliberately designed sets of learning activities using human rights knowledge, values, and skills as content aimed at the general public to enable them to understand their experiences and take control of their lives.

The United Nations World Programme for Human Rights Education defines HRE as: Education, training and information aimed at building a universal culture of human rights. A comprehensive education in human rights not only provides knowledge about human rights and the mechanisms that protect them, but also imparts the skills needed to promote, defend and apply human rights in daily life. Human rights education fosters the attitudes and behaviours needed to uphold human rights for all members of society.

A culture where human rights are learned, lived and “acted” for.

The People's Movement for Human Rights Learning prefers human rights learning to human rights education and places a special focus on human rights as way of life . The emphasis on learning, instead of education, is also meant to draw on the individual process of discovery of human rights and apply them to the person's everyday life.

Other organs of society include NGOs and grassroots organisations which generally work to support vulnerable groups, to protect the environment, monitor governments, businesses and institutions and promote social change. Each NGO brings its own perspective to HRE. Thus, for example, Amnesty International believes that "human rights education is fundamental for addressing the underlying causes of human rights violations, preventing human rights abuses, combating discrimination, promoting equality, and enhancing people's participation in democratic decision-making processes". 3

HRE must mainstream gender awareness and include an intercultural learning dimension.

At the Forum on Human Rights Education with and by Young People, Living, Learning, Acting for Human Rights, held in Budapest in October 2009, the situation of young people in Europe was presented today as one of "precariousness and instability, which seriously hampers equality of opportunities for many young people to play a meaningful part in society [...] human rights, especially social rights and freedom from discrimination, sound like empty words, if not false promises. Persisting situations of discrimination and social exclusion are not acceptable and cannot be tolerated". Thus, the forum participants, concerned with equality of opportunity and discrimination, agreed that, "Human rights education must systematically mainstream gender awareness and gender equality perspectives. Additionally, it must include an intercultural learning dimension; [...] We expect the Council of Europe to […] mainstream minority issues throughout its human rights education programmes, including gender, ethnicity, religion or belief, ability and sexual-orientation issues".

Governments and NGOs tend to view HRE in terms of outcomes in the form of desired rights and freedoms, whereas educational academics, in comparison, tend to focus on values, principles and moral choices. Betty Reardon in Educating for Human Dignity, 1995 states that, "The human rights education framework is intended as social education based on principles and standards [...] to cultivate the capacities to make moral choices, take principled positions on issues – in other words, to develop moral and intellectual integrity". 4 Trainers, facilitators, teachers and other HRE practitioners who work directly with young people tend to think in terms of competences and methodology.

Human rights education is about learning human rights

We hope we have made it clear that different organisations, educational providers and actors in human rights education use different definitions according to their philosophy, purpose, target groups or membership. There is, nonetheless, an obvious consensus that human rights education involves three dimensions:

- Learning about human rights, knowledge about human rights, what they are, and how they are safeguarded or protected;

- Learning through human rights, recognising that the context and the way human rights learning is organised and imparted has to be consistent with human rights values (e.g. participation, freedom of thought and expression, etc.) and that in human rights education the process of learning is as important as the content of the learning;

- Learning for human rights, by developing skills, attitudes and values for the learners to apply human rights values in their lives and to take action, alone or with others, for promoting and defending human rights.

It follows that when we come to think about how to deliver HRE, about how to help people acquire the necessary knowledge, skills and attitudes so they can play their parts within a culture of human rights, we see that we cannot "teach" HRE, but that it has to be learned through experience. Thus HRE is also education through being exposed to human rights in practice. This means that the how and the where HRE is taking place must reflect human rights values (learning in human rights); the context and the activities have to be such that dignity and equality are an inherent part of practice.

In Compass, we have taken special care to make sure that no matter how interesting and playful the methods and activities may be, a reference to human rights is essential for learning about human rights to be credible. There are also various suggestions for taking action.

Human rights education is a fundamental human right

Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights. UDHR, article 26

Human rights are important because no individual can survive alone and injustices diminish the quality of life at a personal, local and global level. What we do in Europe has an effect on what happens elsewhere in the world. For example, the clothes we wear may be made by means of child labour in Asia, while the legacies of European colonial history contribute to the political and religious turmoil in Iraq, Somalia and Afghanistan, which send desperate asylum seekers knocking on our doors. Similarly, millions of people in Africa and Asia are being displaced due to the consequences of climate change caused largely by the activities of the industrialised nations. However, it is not just because human rights violations in other parts of the world rebound on us; the duty to care for others is a fundamental morality found across all cultures and religions. Human rights violations happen everywhere, not only in other countries but also at home, which is why HRE is important. Only with full awareness, understanding and respect for human rights can we hope to develop a culture where they are respected rather than violated. The right to human rights education is therefore increasingly recognised as a human right in itself.

HRE is not only a moral right, but also a legal right under international law. Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that everyone has a right to education and that "Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace". Furthermore, Article 28 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child states that, "School discipline shall be administered in a manner consistent with the child's dignity. Education should be directed to the development of the child's personality, talents and abilities, the respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, responsible life in a free society, understanding, tolerance and equality, the development of respect for the natural environment".

Human rights are more than just inspiration.

HRE is also a legitimate political demand. The message of the Forum Living, learning, Acting for Human Rights recognises that the "values that guide the action of the Council of Europe are universal values for all of us and are centred on the inalienable dignity of every human being". The message goes further in recalling that human rights are more than just inspiration: they are also moral and political commands that apply to the relations between states and people, as much as within states and amongst people.

- Human rights education in the United Nations

The United Nations has an irreplaceable role to play with regard to human rights education in the world. The World Conference on Human Rights, held in Vienna in 1993, reaffirmed the essential role of human rights education, training and public information in the promotion of human rights. In 1994, the United Nations Decade for Human Rights Education was proclaimed by the General Assembly, spanning the period 1 January 1995 to 31 December 2004.

The World Programme on HRE was established in 2004 to promote the development of a culture of human rights.

As a result of the evaluation of the decade, a World Programme for Human Rights Education was established in 2004. The first phase of the programme focused on human rights education in the primary and secondary school systems. All states were expected and encouraged to develop initiatives within the framework of the World Programme and its Plan of Action. The Human Rights Council decided to focus the second phase (2010-2014) on human rights education for higher education and on human rights training programmes for teachers and educators, civil servants, law enforcement officials and military personnel at all levels. Accordingly, in September 2010 it adopted the Plan of Action for the second phase, prepared by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. It also encouraged member states to continue the implementation of human rights education in primary and secondary school systems. The open-ended World Programme remains a common collective framework for action as well as a platform for co-operation between Governments and all other stakeholders.

“every individual and every organ of society shall strive by teaching and education to promote respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms” Preamble of the UN Declaration on Human Rights Education and Training

In December 2011 the General Assembly adopted the UN Declaration on Human Rights Education and Training. The declaration is considered ground-breaking because it is the first instrument devoted specifically to HRE and, therefore, is a very valuable tool for advocacy and raising awareness of the importance of HRE. The declaration recognises that "Everyone has the right to know, seek and receive information about all human rights and fundamental freedoms and should have access to human rights education and training" and that "Human rights education and training is essential for the promotion of universal respect for and observance of all human rights and fundamental freedoms for all, in accordance with the principles of the universality, indivisibility and interdependence of human rights." The declaration also contains a broad definition of human rights education and training which encompasses education about, through and for human rights. The Declaration places on states the main responsibility "to promote and ensure human rights education and training" (Article 7).

Within the UN system, human rights education is co-ordinated by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, based in Geneva, under the authority of the Human Rights Council.

- Human rights education in Europe

The Council of Europe

Commitments to human rights are also commitments to human rights education. Investments in human rights education secure everyone’s future; short-term cuts in education result in long-term losses. Message of the forum Living, Learning, Acting for Human Rights 2009

For the Member States of the Council of Europe, human rights are meant to be more than just assertions: human rights are part of their legal framework, and should therefore be an integral part of young people's education. The European nations made a strong contribution to the twentieth century's most important proclamation of human rights, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 10 December 1948. The European Convention on Human Rights, which has legal force for all member states of the Council of Europe, drew its principles and inspiration from the UN document, and was adopted two years later. The emergence of human rights as we know them today owes much to the massive human rights violations during World War II in Europe and beyond.

Back in 1985 the Committee of Ministers issued Recommendation R (85) 7 to the Member States of the Council of Europe about teaching and learning about human rights in schools. The recommendation emphasised that all young people should learn about human rights as part of their preparation for life in a pluralistic democracy.

The recommendation was reinforced by the Second Summit of the Council of Europe (1997), when the Heads of State and Government of the member States decided to "launch an initiative for education for democratic citizenship with a view to promoting citizens' awareness of their rights and responsibilities in a democratic society". The project on Education for Democratic Citizenship that ensued has played a major role in promoting and supporting the inclusion of education for democratic citizenship and human rights education in school systems. The setting up of the Human Rights Education Youth Programme, and the publication and translations of Compass and, later on, of Compasito, contributed further to the recognition of education to human rights, in particular through non-formal education and youth work.

Member states should aim to provide “every person within their territory with the opportunity of education for democratic citizenship and human rights education”. Council of Europe Charter on Education for Democratic Citizenship and Human Rights Education

In 2010, the Council of Europe Charter on Education for Democratic Citizenship and Human Rights Education was adopted by the Committee of Ministers within the framework of Recommendation CM/Rec (2010) 7. The charter calls on member states to include education for democratic citizenship and human rights education in the curricula for formal education at pre-primary, primary and secondary school level, in general, and for vocational education and training. The charter also calls on the member states to "foster the role of non-governmental organisations and youth organisations in education for democratic citizenship and human rights education, especially in non-formal education. They should recognise them and their activities as a valued part of the educational system, provide them where possible with the support they need and make full use of the expertise they can contribute to all forms of education". "Providing every person within their territory with the opportunity of education for democratic citizenship and human rights education" should be the aim of state policies and legislation dealing with HRE according to the charter. The charter sets out objectives and principles for human rights education and recommends action in the fields of monitoring, evaluation and research. The charter is accompanied by an explanatory memorandum which provides details and examples on the content and practical use of the charter.

The role of human rights education in relation to the protection and promotion of human rights in the Council of Europe was further reinforced with the creation, in 1999, of the post of Commissioner for Human Rights. The Commissioner is entrusted with "promoting education in and awareness of human rights" alongside assisting member states in the implementation of human rights standards, identifying possible shortcomings in the law and practice and providing advice regarding the protection of human rights across Europe. Fulfilling his mandate, the Commissioner gives particular attention to human rights education and considers that human rights can only be achieved if people are informed about their rights and know how to use them. Human rights education is therefore central to the effective implementation of European standards. In a number of reports, he called upon national authorities to reinforce human rights education. School children and youth, but also teachers and government officials must be educated to promote the values of tolerance and respect for others. In a viewpoint entitled "Human rights education is a priority – more concrete action is needed" 5 , he stated that, "more emphasis has been placed on preparing the pupils for the labour market rather than developing life skills which would incorporate human rights values". There should be both "human rights through education" and "human rights in education".

The promotion of the right to human rights education in the Council of Europe is thus cross-sectorial and multi-disciplinary. The Council of Europe liaises and co-ordinates its work on HRE with other international organisations, including UNESCO, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, the OSCE (Organisation for Co-operation and Security in Europe) and the Fundamental Rights Agency of the European Union. It has also acted as regional co-ordinator for the UN World Programme on Human Rights Education.

The European Wergeland Centre

The European Wergeland Centre , located in Oslo, Norway, is a Resource Centre working on Education for Intercultural Understanding, Human Rights and Democratic Citizenship. The Centre was established in 2008 as a co-operative project between Norway and the Council of Europe. The main target groups are education professionals, researchers, decision makers and other multipliers. The activities of the Wergeland Centre include:

- training for teacher trainers, teachers and other educators

- research and development activities

- conferences and networking services, including an online expert database

- an electronic platform for disseminating information, educational materials and good practices.

The European Union

In 2007 the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) was established as an advisory body to help ensure that fundamental rights of people living in the EU are protected. The FRA, based in Vienna, Austria, is an independent body of the European Union (EU), established to provide assistance and expertise to the European Union and its Member States when they are implementing Community law, on fundamental rights matters. The FRA also has a mission to raise public awareness about fundamental rights, which include human rights as defined by the European Convention on Human Rights and those of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.

The youth programmes of the European Union have, over the years, dedicated particular attention to equality, active citizenship and human rights education.

Many youth projects carried out within the framework of the Youth and Erasmus programmes are based on non-formal learning and provide important opportunities for young people to discover human rights values and human rights education.

- Youth policy and human rights education

The Council of Europe has a longstanding record of associating young people with the process of European construction, and of considering youth policy as an integral part of its work. The first activities for youth leaders were held in 1967 and in 1972 the European Youth Centre and the European Youth Foundation were set up. The relationship between the Council of Europe and youth has developed consistently since then, with young people and youth organisations being important actors and partners at key defining moments for for the organisation and for Europe. Whether in the democratisation processes of the former communist countries, in peace building and conflict transformation in conflict areas or in the fight against racism, antisemitism, xenophobia and intolerance, young people and their organisations have always counted on the Council of Europe and reciprocally the Council has been able to rely on them. Soft and deep security on the European continent cannot be envisaged without the contribution of human rights education and democratic participation.

The stated aim of the youth policy of the Council of Europe is to "provide young people, i.e. girls and boys, young women and young men with equal opportunities and experience which enable them to develop the knowledge, skills and competences to play a full part in all aspects of society" 6 .

Providing young people with equal opportunities and experiences enabling them to play a full part in society.

The role of young people, youth organisations and youth policy in promoting the right to human rights education is also clearly spelt out in the priorities for the youth policy of the Council of Europe, one of which is Human Rights and Democracy, implemented with a special emphasis on:

- ensuring young people's full enjoyment of human rights and human dignity, and encouraging their commitment in this regard

- promoting young people's active participation in democratic processes and structures

- promoting equal opportunities for the participation of all young people in all aspects of their everyday lives

- effectively implementing gender equality and preventing all forms of gender-based violence

- promoting awareness education and action among young people on environment and sustainable development

- facilitating access for all young people to information and counselling services.

The youth policy of the Council of Europe also foresees close co-operation between child and youth policies, as the two groups, children and young people, overlap to a large extent.

In 2000, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary for the European Convention on Human Rights, the Directorate of Youth and Sport launched its Human Rights Education Youth Programme . The programme has ensured the mainstreaming of HRE in the Council's work with young people and in youth policy and youth work. Young people and youth organisations have taken a central role in the programme as educators and advocates for human rights and have made significant contributions to the Council of Europe's work.

A further dimension to the programme was the publication of Compass in 2002 and its subsequent translation in more than 30 languages. A programme of European and national training courses for trainers and multipliers has contributed to the emergence of formal and informal networks of educators and advocates for HRE which is producing visible results, although these differ profoundly from one country to another. The success of the Human Rights Education Youth Programme has also been built on:

- The support for key regional and national training activities for trainers of teachers and youth workers in the member states, organised in co-operation with national organisations and institutions

- The development of formal and informal networks of organisations and educators for human rights education through non-formal learning approaches at European and national levels

- The mainstreaming of human rights education approaches and methods in the overall programme of activities of the youth sector of the Council of Europe

- The development of innovative training and learning approaches and quality standards for human rights education and non-formal learning, such as the introduction of e-learning by the Advanced Compass Training in Human Rights Education

- Providing the educational approaches and resources for the All Different – All Equal European youth campaign for Diversity, Human Rights and Participation

- The dissemination of the Living Library as a methodology for intercultural learning, combating stereotypes and prejudices

- The provision of the political and educational framework for intercultural dialogue activities

The programme has also mobilised thousands of young people across Europe through the support of pilot projects on human rights education by the European Youth Foundation.

In 2009, on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the Council of Europe, a youth forum on human rights education – Learning, Living, Acting for Human Rights – brought together more than 250 participants at the European youth centres in Budapest and Strasbourg. The participants in the forum issued a message to the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe. The message stresses the principles and needs for HRE in Europe through:

- securing adequate levels of multiplication and relaying through projects and partners at national and local levels, and through developing optimal communication between the European, the national and the local levels of action;

- seeking alliances between formal and non-formal education actors and with human rights institutions for the setting up of national human rights education programmes;

- developing the capacity of non-governmental partners while seeking greater involvement of governmental youth partners;

- supporting trans-national co-operation and networks for human rights education;

- deepening awareness about specific human rights issues affecting young people (e.g. violence, and exclusion);

- including a gender awareness perspective and an intercultural dimension as inherent to the concept of equality in human dignity;

- closely linking human rights education activities with the realities of young people, youth work, youth policy and non-formal learning;

- considering the necessary overlapping and the complementary nature of human rights education with children and with youth;

- recognising and promoting human rights education as a human right, and raising awareness about this;

- taking into account the protection of the freedom and security of human rights activists and educators;

- mainstreaming minority issues, including gender, ethnicity, religion or belief, ability and sexual-orientation issues;

- supporting the active participation and ownership of young people and children in educational processes;

- raising awareness of the responsibility of states and public authorities in promoting and supporting human rights education in the formal and non-formal education fields.

- HRE with young people

It seems obvious that young people should be concerned with human rights education, but the reality is that most young people in Europe have little access to human rights education. Compass was developed to change this.

Human rights education with young people benefits not only society, but also the young people themselves. In contemporary societies young people are increasingly confronted by processes of social exclusion, of religious, ethnic and national differences, and by the disadvantages – and advantages – of globalisation. Human rights education addresses these issues and can help people to make sense of the different beliefs, attitudes and values, and the apparent contradictions of the modern multi-cultural societies that they live in.

The special Eurobarometer report of March 2008, "Attitudes of European citizens towards the environment", states that Europeans attach an overwhelming importance to protecting the environment and that 96% say that it is either very or fairly important to them. Young people in particular are very willing to commit their energy and enthusiasm to issues that concern them. One example are the 100,000 who demonstrated for action to be taken to combat climate change in Copenhagen in December 2009. As human rights educators, we need to harness that energy. That they will take up ideas and act on them is evident from the many programmes that already exist for young people – from the small scale activities carried out on a relatively ad hoc basis in individual youth clubs or schools to the major international programmes conducted by the Council of Europe and the European Union.

One example of the contribution made by human rights educated young people in Europe is in the preparation of country reports for the Minorities Rights Group. These reports, used by governments, NGOs, journalists and academics, offer analysis of minority issues, include the voices of those communities and give practical guidance and recommendations on ways to move forward. In this way human rights education can be seen as complementary to the work of the European Court of Human Rights in sending clear messages that violations will not be tolerated. However, HRE offers more: it is also a positive way to prevent violations in the first place and thus to secure better functioning and more effective prevention and sanction mechanisms. People who have acquired values of respect and equality, attitudes of empathy and responsibility and who have developed skills to work co-operatively and think critically will be less ready to violate the human rights of others in the first place. Young people also act as educators and facilitators of human rights education processes and therefore are an important support and resource for developing plans for HRE at national and local level.

- Towards a culture of human rights

You can cut all the flowers but you cannot keep spring from coming. Pablo Neruda

"All roads lead to Rome" is a common idiom meaning that there are many ways of getting to your goal. Just as all roads lead to Rome, so there are many different ways to delivering HRE. Thus, human rights education is perhaps best described in terms of what it sets out to achieve: the establishment of a culture where human rights are understood, defended and respected, or to paraphrase the participants of the 2009 Forum on Human Rights Education with Young People, "a culture where human rights are learned, lived and ‘acted' for".

A human rights culture is not merely a culture where everyone knows their rights, because knowledge does not necessarily equal respect, and without respect we shall always have violations. So how can we describe a human rights culture and what qualities would its adherents have? The authors of this manual worked on these questions and have formulated some (but not exclusive) answers. A human rights culture is one where people:

- Have knowledge about and respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms

- Have a sense of individual self-respect and respect for others; they value human dignity

- Demonstrate attitudes and behaviours that show respect for the rights of others

- Practise genuine gender equality in all spheres

- Show respect, understanding and appreciation of cultural diversity, particularly towards different national, ethnic, religious, linguistic and other minorities and communities

- Are empowered and active citizens

- Promote democracy, social justice, communal harmony, solidarity and friendship between people and nations

- Are active in furthering the activities of international institutions aimed at the creation of a culture of peace, based upon universal values of human rights, international understanding, tolerance and non-violence.

These ideals will be manifested differently in different societies because of differing social, economic, historical and political experiences and realities. It follows that there will also be different approaches to HRE. There may be different views about the best or most appropriate way to move towards a culture of human rights, but that is as it should be. Individuals, groups of individuals, communities and cultures have different starting points and concerns. A culture of human rights ought to take into account and respect those differences.

1 Words emphasised by the editors 2 Committee of Ministers Recommendation CM/Rec(2010)7 on the Council of Europe Charter on Education for Democratic Citizenship and Human Rights Education 3 http://www.amnesty.org/en/human-rights-education 4 Betty A. Reardon: Educating for Human Dignity – Learning about rights and responsibilities, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995 5 www.fra.europa.eu (accessed on 13 October 2010) 6 Resolution of the Committee of Minister on the youth policy of the Council of Europe, CM/Res(2008)23 United Nations, Plan of Action of the World Programme for Human Rights Education – First phase, Geneva, 2006

Download Compass

- Human rights education is a fundamental human right

- Chapter 1 - Human Rights Education and Compass: an introduction

- Chapter 2 - Practical Activities and Methods for Human Rights Education

- Chapter 3 - Taking Action for Human Rights

- Chapter 4 - Understanding Human Rights

- Chapter 5 - Background Information on Global Human Rights Themes

A network dedicated to building a culture of human rights

Human Rights Education

Human Rights Education Video from Amnesty Ireland on Vimeo .

WHAT IS HUMAN RIGHTS EDUCATION?

Human Rights Educators USA defines human rights education (HRE) as

… a lifelong process of teaching and learning that helps individuals develop the knowledge, skills, and values to fully exercise and protect the human rights of themselves and others; to fulfill their responsibilities in the context of internationally agreed upon human rights principles; and to achieve justice and peace in our world.

For a discussion of various conceptions of human rights education, see:

- Nancy Flowers, “What is Human Rights Education?”

- Council of Europe, Compasito, a Manual on Human Rights Education for Children , Chapter 2, “What is Human Rights Education?”

WHAT ARE THE GOALS OF HRE?

The mandate for human rights education is clear: For more than sixty years the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) has charged “every individual and every organ of society ” to “strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedom.” The 2012 UN Declaration for Human Rights Education and Training further emphasizes “the fundamental importance of human rights education and training in contributing to the promotion, protection and effective realization of all human rights” and reaffirms “that governments are “duty-bound …to ensure that education is aimed at strengthening respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms.”

The goals of human rights education include learning about human rights, for human rights, and in human rights.

Learning about Human Rights Knowing about your rights is the first step in promoting greater respect for human rights. All segments of society need to understand the provisions of the Universal Declaration of Human rights (UDHR, 1948) and how these international standards affect governments and individuals. They also need to understand the interdependence of rights, both civil and political rights and social, economic, and cultural rights.

Learning for Human Rights Education for human rights means understanding and embracing the principles of human equality and dignity and the commitment to respect and protect the rights of all people. It has little to do with what we know; the “test” for this kind of learning is how we act. The ultimate goal of education for human rights is empowerment, giving people the knowledge and skills to become responsible and engaged citizen committed to building a just civil society.

Learning in Human Rights Educators face a double challenge. First to teach in such a way as to respect human rights in the classroom and the school environment itself. For learning to have practical benefit, students need not only to learn about human rights, but also to learn in an environment that models them.

The second challenge is personally to model human rights values. Human rights education encourages everyone to use human rights as a frame of reference in their institutions and in their relationships with others . It especially challenges educators, as role models, critically to examine their own attitudes and behaviors and, ultimately, to transform them in order to advance peace, social harmony and respect for the rights of all.

One Practice, Many Goals

In this new field, the goals and the content needed to achieve these goals are under continual and generally creative debate. Among the goals that motivate most human rights educators are:

- developing critical analysis of their life situation;

- changing attitudes;

- changing behaviors;

- clarifying values;

- developing solidarity;

- analyzing situations in human rights terms;

- strategizing and implementing appropriate responses to injustice.

For more on the goals of human rights education:

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, ABC, Teaching Human Rights: Practical Activities for Primary and Secondary School

- Council of Europe, Compass

WHY TEACH HUMAN RIGHTS?

Each declaration or treaty expressing human rights principles or humanitarian law standards, commits all state parties to educate their people about these internationally agreed-upon rights and standards. In the US this responsibility to educate exists at different levels within the federal system and within different agencies at state and local levels. Because today local, national, and international spheres have become increasingly interdependent, the quality of human rights provided in pre-collegiate education carries national and global consequences. Today’s students must understand fundamental principles of human rights to appropriately exercise their civic responsibilities and take their places in the world at large.

Active Citizenship Human rights education is essential to active citizenship in a democratic and pluralistic civil society. Citizens need to be able to think critically, make moral choices, take principled positions on issues, and devise democratic courses of action. Participation in the democratic process means, among other things, an understanding and conscious commitment to the fundamental values of human rights and democracy, such as equality and fairness, and being able to recognize problems such as racism, sexism, and other injustices as violations of those values. Active citizenship also means participation in the democratic process, motivated by a sense of personal responsibility for promoting and protecting the rights of all. But to be engaged in this way, citizens must first be informed.

Informed Activism Learning is also essential to human rights activism. Only people who understand human rights will work to secure and defend them for themselves and others. The better informed activists are, the more effective their activism. Furthermore, activists must themselves serve as catalysts for human rights learning in their own schools, workplaces, and neighborhoods.

THE CONTENT OF HUMAN RIGHTS EDUCATION

Human rights education intersects with and reinforces many other forms of education, including peace education, global education, law-related education, development education, environmental education, and moral or values education. HRE is distinct from these related fields, however, by being grounded in principles based on international human rights documents.

1. Fundamental Principles of Human Rights:

For schools the core content of HRE is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child . These documents provide principles and ideas with which to assess experience and build a school culture that values human rights. The rights they embody are universal , meaning that all human beings are entitled to them, on an equal basis.

Human rights include civil and political rights , such as the right to life, liberty and freedom of expression: rights also found in the US Constitution and Bill of Rights. Human rights also include economic, social, and cultural rights such as the right to participate in culture, the right to food, and the right to work and receive an education. Human rights are indivisible , meaning that no right can be considered “less important” or “non-essential.” And human rights are interdependent , part of a complementary framework. For example, your right to participate in government is directly affected by your right to express yourself, to form associations, to get an education, and even to obtain the necessities of life.

With the UDHR as its foundation, a framework of international human rights law has evolved since the mid-20th century. The chart below shows the principal human rights treaties. Stars indicate those treaties which the USA has ratified and has a legal responsibility to implement.

PRINCIPAL HUMAN RIGHTS CONVENTIONS

- International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR, 1966)

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR, 1966)

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD, 1965)

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women

- Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishmen t (CAT, 1984)

- The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC, 1989)

- Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (ICMW, 1990)

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD, 2006)

- International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (2006)

- Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (Refugee Convention, 1951)

2. A Human Rights Perspective on Social Issues

Human rights education offers a distinctly different approach to familiar topics from history, as well as contemporary issues. For example, often-taught historical topics like the Civil War, the Age of Exploration, or US immigration can look quite different through a human rights lens, Likewise, discussing current national or school issues like internet freedom, school violence, or federal health policies from a human rights perspective can add an important new dimension.

For more on the content of human rights education:

- Nancy Flowers, The Human Rights Education Handbook , Part III, “The Content of Human Rights Education”

- Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE), Guidelines on Human rights Education for Secondary Schools

METHODOLOGIES FOR HUMAN RIGHTS EDUCATION

No matter what the setting – classroom, service learning program, university, or community center – common principles inform the methods for effectively teaching and learning human rights. These include using participatory methods for learning such as role plays, discussion, debates, mock trials, games, and simulations. Learners should be encouraged to engage in an open-minded examination of human rights concerns and critically reflect on their environment with opportunities to draw their own conclusions and envision their choices in presented situations. Universal human rights represent a positive value system , a standard to which everyone is entitled. Learners can make connections between these values and their own lived experiences. This approach recognizes that the individual can make a difference and provides opportunities to explore examples of individuals who have done so.

Learners should examine both the international/global dimension and the domestic implications of human rights themes and consider how they relate to questions of diversity, economic inequality, and the relationship between individual choices and collective well-being. These intersections provide an opportunity to incorporate a variety of perspectives (e.g., race, gender, sexual orientation, religion, cultural/national traditions). In addition, human rights should be explicitly linked to relevant provisions of international, regional, national and state laws, treaties and declarations, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Geneva Conventions .

For more on human rights education methodologies see:

- Richard Pierre Claude, Methodologies for Human Rights Education

- Council of Europe, Human Rights Album Methodology Handbook

- Nancy Flowers, The Human Rights Education Handbook , Part IV, “ Methods for Human Rights Education”

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Human Rights Training

THE AUDIENCE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS EDUCATION

Who needs human rights education? The simple answer is, of course, everyone. However, human rights education is especially critical for some groups:

- Young children and their parents: Educational research shows conclusively that attitudes about equality and human dignity are largely set before the age of ten. Human rights education cannot start too young.

- Teachers, principals, and educators of all kinds: No one should be licensed to enter the teaching profession without a fundamental grounding in human rights, especially the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC).

Veteran teachers present a particular challenge because human rights education involves not only new information, but also introduces attitudes and methodologies that may challenge their accustomed authority in the classroom. Nevertheless, most teachers around the world share a common trait: a genuine concern for children. This motivation and a systematic in-service training program linked to recertification or promotion can achieve a basic knowledge of human rights for all teachers.

- Doctors and nurses, lawyers and judges, social workers, journalists, police, and military officials: Some people urgently need to understand human rights because of the power they wield or the positions of responsibility they hold. Human rights courses should be fundamental to the curriculum of medical schools, law schools, universities, police and military academies, and other professional training institutions.

- Especially vulnerable populations: Human rights education must not be limited to formal schooling. Many people never attend school. Many live far from administrative centers. Yet they, as well as refugees, minorities, migrant workers, indigenous peoples, the disabled, and the poor, are often among the most powerless and vulnerable to abuse. Such people have no less right to know their rights and far greater need.

- Activists and Non-Profit Organizations: Many human rights activists lack a grounding in the human rights framework and many human rights scholars know next to nothing about the strategies of advocacy. Few people working in nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) recognize that they may be engaged in human rights work. Especially in the United States, where social and economic justice is rarely framed in human rights language, many activists who work on issues like fair wages, health care, and housing need to understand their work in a human rights context and recognize their solidarity with other workers for social and economic justice.

- Public office holders, whether elected or appointed : In a democracy no one can serve the interests of the people who does not understand and support human rights.

- Power Holders: This group includes members of the business and banking community, landowners, traditional and religious leaders, and anyone whose decisions and policies affect many peoples’ lives. As possessors of power, they are often highly resistant, regarding human rights as a threat to their position and often working directly or indirectly to impede human rights education. To reach those in power, human rights need to be presented as benefiting the community and themselves, offering long-term stability and furthering development.

| The core values of HRE USA and its partner organizations include transparency and critical thinking skills. We believe that human rights--and human rights education--belong to everyone, and that the full realization of human rights means that access to human rights education materials must never be conditioned upon the subscription to any particular religious faith, ideology, political affiliation, or membership in any particular organization and that any organizational connections should be openly acknowledged. |

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Publication

Human rights education: key success factors

Why human rights education matters

Despite significant progress, human rights and fundamental freedoms are violated every day around the world. These violations range from barriers to educational access, discrimination based on gender, race, and religion, to racism, hate speech and violent conflicts. For example, 2023 marked the 13th time peacefulness has deteriorated in the last 15 years, and 79 countries witnessed increased levels of conflict.

Human rights violations are an affront to just, peaceful and inclusive societies and require urgent, collective and sustained efforts at all levels. Education lies at the centre of these efforts to achieve human rights. Effective human rights education inculcates knowledge, skills, values, beliefs and attitudes that encourage all individuals to uphold their own rights and those of others.

This study, commissioned by UNESCO in cooperation with the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), examines the impact of human rights education (HRE) pedagogies and good practices worldwide, with a specific focus on the primary and secondary levels in formal education. Using a data-driven approach that includes a literature review and surveys and interviews with informants, the study identifies key success factors for impactful HRE and provides recommendations for future research and practice.

The study finds that HRE can have a positive impact on learners’ knowledge and understanding of human rights, as well as their attitudes and behaviours related to human rights. It is an essential resource for education stakeholders looking to promote HRE at all levels of society and through a lifelong learning lens.

Related items

- Civic education

- Human rights

- Human rights education

- Topics: Display

- See more add

Other recent publications

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Human rights education.

- A. Kayum Ahmed A. Kayum Ahmed Columbia University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1573

- Published online: 26 April 2021

Human rights education (HRE) can be described as a tool for popularizing and giving effect to the universal human rights regime. The United Nations (UN) defines HRE as (a) acquiring knowledge about human rights and the skills to exercise these rights, (b) developing values, attitudes, and beliefs that support and reinforce human rights; and (c) defending and advancing human rights through behavior and action. HRE is therefore an ideological instrument deployed as a tactic to inspire agency and activism, primarily as a counterbalance to state power. HRE as tactics is used to denote the education and training of individuals and groups working toward claiming certain protections for themselves or on behalf of those on the margins of society. This typology encompasses the range of legal, advocacy, and policy tools available within human rights frameworks to uphold and protect the rights of individuals and communities. But it is also important to recognize that human rights discourses can been appropriated by certain states to strengthen their sovereign power. HRE as sovereignty acknowledges that states, as well as corporations and far-right civil society groups, can appropriate human rights language in order to reinforce power and legitimacy. States who engage in HRE as sovereignty deliberately employ human rights language with the aim of constructing a self-serving narrative that entrenches power or legitimizes their behavior and actions. HRE as sovereignty characterizes the appropriation of HRE to entrench power through the creation of an official, immutable narrative embedded in human rights language.

- human rights education

- human rights

- sovereignty

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Education. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 30 June 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [185.126.86.119]

- 185.126.86.119

Character limit 500 /500

- Achievement Gap

- Alternative Education

- American Education Awards

- Assessment & Evaluation

- Education during COVID-19

- Education Economics

- Education Environment

- Education in the United States during COVID-19

- Education Issues

- Education Policy

- Education Psychology

- Education Scandals and Controversies

- Education Reform

- Education Theory

- Education Worldwide

- Educational Leadership

- Educational Philosophy

- Educational Research

- Educational Technology

- Federal Education Legislation

- Higher Education Worldwide

- Homeless Education

- Homeschooling in the United States

- Migrant Education

- Neglected/Deliquent Students

- Sociology of Education

- Bipolar Disorder

- Cerebral Palsy

- Down Syndrome

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Social Anxiety

- Special Needs Services

- Tourette Syndrome (TS)

- View all Special Needs Topics

- After School Programs

- Alternative Schools

- At-Risk Students

- Camp Services

- Colleges & Universities

- Driving Schools

- Educational Businesses

- Financial Aid

- Higher Education

- International Programs

- Jewish Community Centers

- K-12 Schools

- Language Studies

- Organizations

- Professional Development

- Prom Services

- School Assemblies

- School Districts

- School Field Trips

- School Health

- School Supplies

- School Travel

- School Vendors

- Schools Worldwide

- Special Education

- Special Needs

- Study Abroad

- Teaching Abroad

- Volunteer Programs

- Youth Sports

- Academic Standards

- Assembly Programs

- Blue Ribbon Schools Program

- Educational Accreditation

- Educational Television Channels

- Education in the United States

- History of Education in the United States

- Reading Education in the U.S.

- School Grades

- School Meal Programs

- School Types

- School Uniforms

- Special Education in the United States

- Systems of Formal Education

- U.S. Education Legislation

- Academic Dishonesty

- Childcare State Licensing Requirements

- Classroom Management

- Education Subjects

- Educational Practices

- Educational Videos

- Interdisciplinary Teaching

- Job and Interview Tips

- Lesson Plans | Grades

- State Curriculum Standards

- Substitute Teaching

- Teacher Salary

- Teacher Training Programs

- Teaching Methods

- Training and Certification

- Academic Competitions

- Admissions Testing

- Career Planning

- College Admissions

- Drivers License

- Educational Programs

- Educational Television

- High School Dropouts

- Senior Proms

- Sex Education

- Standardized Testing

- Student Financial Aid

- Student Television Stations

- Summer Learning Loss

Search the United Nations

- Member States

Main Bodies

- Secretary-General

- Secretariat

- Emblem and Flag

- ICJ Statute

- Nobel Peace Prize

- Peace and Security

- Human Rights

- Humanitarian Aid

- Sustainable Development and Climate

- International Law

- Global Issues

- Official Languages

- Observances

- Events and News

- Get Involved

- Israel-Gaza

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is a milestone document in the history of human rights. Drafted by representatives with different legal and cultural backgrounds from all regions of the world, the Declaration was proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on 10 December 1948 ( General Assembly resolution 217 A ) as a common standard of achievements for all peoples and all nations. It sets out, for the first time, fundamental human rights to be universally protected and it has been translated into over 500 languages . The UDHR is widely recognized as having inspired, and paved the way for, the adoption of more than seventy human rights treaties, applied today on a permanent basis at global and regional levels (all containing references to it in their preambles).

Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world,

Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people,

Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law,

Whereas it is essential to promote the development of friendly relations between nations,

Whereas the peoples of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom,

Whereas Member States have pledged themselves to achieve, in co-operation with the United Nations, the promotion of universal respect for and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms,

Whereas a common understanding of these rights and freedoms is of the greatest importance for the full realization of this pledge,

Now, therefore,

The General Assembly,

Proclaims this Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations, to the end that every individual and every organ of society, keeping this Declaration constantly in mind, shall strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms and by progressive measures, national and international, to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance, both among the peoples of Member States themselves and among the peoples of territories under their jurisdiction.

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty.

Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.

No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms.

No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

Everyone has the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law.

All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination.

Everyone has the right to an effective remedy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or by law.

No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile.

Everyone is entitled in full equality to a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal, in the determination of his rights and obligations and of any criminal charge against him.

- Everyone charged with a penal offence has the right to be presumed innocent until proved guilty according to law in a public trial at which he has had all the guarantees necessary for his defence.

- No one shall be held guilty of any penal offence on account of any act or omission which did not constitute a penal offence, under national or international law, at the time when it was committed. Nor shall a heavier penalty be imposed than the one that was applicable at the time the penal offence was committed.

No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.

- Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state.

- Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.

- Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution.

- This right may not be invoked in the case of prosecutions genuinely arising from non-political crimes or from acts contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations.

- Everyone has the right to a nationality.

- No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality.

- Men and women of full age, without any limitation due to race, nationality or religion, have the right to marry and to found a family. They are entitled to equal rights as to marriage, during marriage and at its dissolution.