- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Business Essentials

What Is Research and Development (R&D)?

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/wk_headshot_aug_2018_02__william_kenton-5bfc261446e0fb005118afc9.jpg)

Investopedia / Ellen Lindner

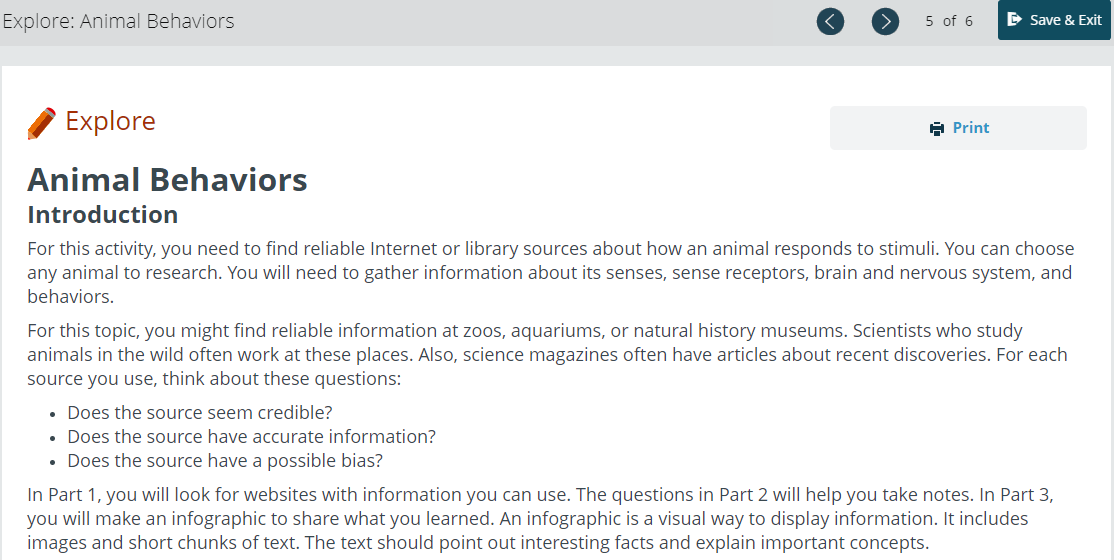

Research and development (R&D) is the series of activities that companies undertake to innovate. R&D is often the first stage in the development process that results in market research product development, and product testing.

Key Takeaways

- Research and development represents the activities companies undertake to innovate and introduce new products and services or to improve their existing offerings.

- R&D allows a company to stay ahead of its competition by catering to new wants or needs in the market.

- Companies in different sectors and industries conduct R&D—pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, and technology companies generally spend the most.

- R&D is often a broad approach to exploratory advancement, while applied research is more geared towards researching a more narrow scope.

- The accounting for treatment for R&D costs can materially impact a company's income statement and balance sheet.

Understanding Research and Development (R&D)

The concept of research and development is widely linked to innovation both in the corporate and government sectors. R&D allows a company to stay ahead of its competition. Without an R&D program, a company may not survive on its own and may have to rely on other ways to innovate such as engaging in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) or partnerships. Through R&D, companies can design new products and improve their existing offerings.

R&D is distinct from most operational activities performed by a corporation. The research and/or development is typically not performed with the expectation of immediate profit. Instead, it is expected to contribute to the long-term profitability of a company. R&D may often allow companies to secure intellectual property, including patents , copyrights, and trademarks as discoveries are made and products created.

Companies that set up and employ departments dedicated entirely to R&D commit substantial capital to the effort. They must estimate the risk-adjusted return on their R&D expenditures, which inevitably involves risk of capital. That's because there is no immediate payoff, and the return on investment (ROI) is uncertain. As more money is invested in R&D, the level of capital risk increases. Other companies may choose to outsource their R&D for a variety of reasons including size and cost.

Companies across all sectors and industries undergo R&D activities. Corporations experience growth through these improvements and the development of new goods and services. Pharmaceuticals, semiconductors , and software/technology companies tend to spend the most on R&D. In Europe, R&D is known as research and technical or technological development.

Many small and mid-sized businesses may choose to outsource their R&D efforts because they don't have the right staff in-house to meet their needs.

Types of Research and Development (R&D)

There are several different types of R&D that exist in the corporate world and within government. The type used depends entirely on the entity undertaking it and the results can differ.

Basic Research

There are business incubators and accelerators, where corporations invest in startups and provide funding assistance and guidance to entrepreneurs in the hope that innovations will result that they can use to their benefit.

M&As and partnerships are also forms of R&D as companies join forces to take advantage of other companies' institutional knowledge and talent.

Applied Research

One R&D model is a department staffed primarily by engineers who develop new products —a task that typically involves extensive research. There is no specific goal or application in mind with this model. Instead, the research is done for the sake of research.

Development Research

This model involves a department composed of industrial scientists or researchers, all of who are tasked with applied research in technical, scientific, or industrial fields. This model facilitates the development of future products or the improvement of current products and/or operating procedures.

The largest companies may also be the ones that drive the most R&D spend. For example, Amazon has reported $1.147 billion of research and development value on its 2023 annual report.

Advantages and Disadvantages of R&D

There are several key benefits to research and development. It facilitates innovation, allowing companies to improve existing products and services or by letting them develop new ones to bring to the market.

Because R&D also is a key component of innovation, it requires a greater degree of skill from employees who take part. This allows companies to expand their talent pool, which often comes with special skill sets.

The advantages go beyond corporations. Consumers stand to benefit from R&D because it gives them better, high-quality products and services as well as a wider range of options. Corporations can, therefore, rely on consumers to remain loyal to their brands. It also helps drive productivity and economic growth.

Disadvantages

One of the major drawbacks to R&D is the cost. First, there is the financial expense as it requires a significant investment of cash upfront. This can include setting up a separate R&D department, hiring talent, and product and service testing, among others.

Innovation doesn't happen overnight so there is also a time factor to consider. This means that it takes a lot of time to bring products and services to market from conception to production to delivery.

Because it does take time to go from concept to product, companies stand the risk of being at the mercy of changing market trends . So what they thought may be a great seller at one time may reach the market too late and not fly off the shelves once it's ready.

Facilitates innovation

Improved or new products and services

Expands knowledge and talent pool

Increased consumer choice and brand loyalty

Economic driver

Financial investment

Shifting market trends

R&D Accounting

R&D may be beneficial to a company's bottom line, but it is considered an expense . After all, companies spend substantial amounts on research and trying to develop new products and services. As such, these expenses are often reported for accounting purposes on the income statement and do not carry long-term value.

There are certain situations where R&D costs are capitalized and reported on the balance sheet. Some examples include but are not limited to:

- Materials, fixed assets, or other assets have alternative future uses with an estimable value and useful life.

- Software that can be converted or applied elsewhere in the company to have a useful life beyond a specific single R&D project.

- Indirect costs or overhead expenses allocated between projects.

- R&D purchased from a third party that is accompanied by intangible value. That intangible asset may be recorded as a separate balance sheet asset.

R&D Considerations

Before taking on the task of research and development, it's important for companies and governments to consider some of the key factors associated with it. Some of the most notable considerations are:

- Objectives and Outcome: One of the most important factors to consider is the intended goals of the R&D project. Is it to innovate and fill a need for certain products that aren't being sold? Or is it to make improvements on existing ones? Whatever the reason, it's always important to note that there should be some flexibility as things can change over time.

- Timing: R&D requires a lot of time. This involves reviewing the market to see where there may be a lack of certain products and services or finding ways to improve on those that are already on the shelves.

- Cost: R&D costs a great deal of money, especially when it comes to the upfront costs. And there may be higher costs associated with the conception and production of new products rather than updating existing ones.

- Risks: As with any venture, R&D does come with risks. R&D doesn't come with any guarantees, no matter the time and money that goes into it. This means that companies and governments may sacrifice their ROI if the end product isn't successful.

Research and Development vs. Applied Research

Basic research is aimed at a fuller, more complete understanding of the fundamental aspects of a concept or phenomenon. This understanding is generally the first step in R&D. These activities provide a basis of information without directed applications toward products, policies, or operational processes .

Applied research entails the activities used to gain knowledge with a specific goal in mind. The activities may be to determine and develop new products, policies, or operational processes. While basic research is time-consuming, applied research is painstaking and more costly because of its detailed and complex nature.

R&D Tax Credits

The IRS offers a R&D tax credit to encourage innovation and significantly reduction their tax liability. The credit calls for specific types of spend such as product development, process improvement, and software creation.

Enacted under Section 41 of the Internal Revenue Code, this credit encourages innovation by providing a dollar-for-dollar reduction in tax obligations. The eligibility criteria, expanded by the Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes (PATH) Act of 2015, now encompass a broader spectrum of businesses. The credit tens to benefit small-to-midsize enterprises.

To claim R&D tax credits, businesses must document their qualifying expenses and complete IRS Form 6765 (Credit for Increasing Research Activities). The credit, typically ranging from 6% to 8% of annual qualifying expenses, offers businesses a direct offset against federal income tax liabilities. Additionally, businesses can claim up to $250,000 per year against their payroll taxes.

Example of Research and Development (R&D)

One of the more innovative companies of this millennium is Apple Inc. As part of its annual reporting, it has the following to say about its research and development spend:

In 2023, Apple reported having spent $29.915 billion. This is 8% of their annual total net sales. Note that Apple's R&D spend was reported to be higher than the company's selling, general and administrative costs (of $24.932 billion).

Note that the company doesn't go into length about what exactly the R&D spend is for. According to the notes, the company's year-over-year growth was "driven primarily by increases in headcount-related expenses". However, this does not explain the underlying basis carried from prior years (i.e. materials, patents, etc.).

What Is Research and Development?

Research and development refers to the systematic process of investigating, experimenting, and innovating to create new products, processes, or technologies. It encompasses activities such as scientific research, technological development, and experimentation conducted to achieve specific objectives to bring new items to market.

What Types of Activities Can Be Found in Research and Development?

Research and development activities focus on the innovation of new products or services in a company. Among the primary purposes of R&D activities is for a company to remain competitive as it produces products that advance and elevate its current product line. Since R&D typically operates on a longer-term horizon, its activities are not anticipated to generate immediate returns. However, in time, R&D projects may lead to patents, trademarks, or breakthrough discoveries with lasting benefits to the company.

Why Is Research and Development Important?

Given the rapid rate of technological advancement, R&D is important for companies to stay competitive. Specifically, R&D allows companies to create products that are difficult for their competitors to replicate. Meanwhile, R&D efforts can lead to improved productivity that helps increase margins, further creating an edge in outpacing competitors. From a broader perspective, R&D can allow a company to stay ahead of the curve, anticipating customer demands or trends.

The Bottom Line

There are many things companies can do in order to advance in their industries and the overall market. Research and development is just one way they can set themselves apart from their competition. It opens up the potential for innovation and increasing sales. However, it does come with some drawbacks—the most obvious being the financial cost and the time it takes to innovate.

Amazon. " 2023 Annual Report ."

Internal Revenue Service. " Research Credit ."

Internal Revenue Service. " About Form 6765, Credit for Increasing Research Activities ."

Apple. " 2023 Annual Report ."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/research_pharma-5bfc322b46e0fb0051bf11a0.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, March 20). Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 21 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Building an R&D strategy for modern times

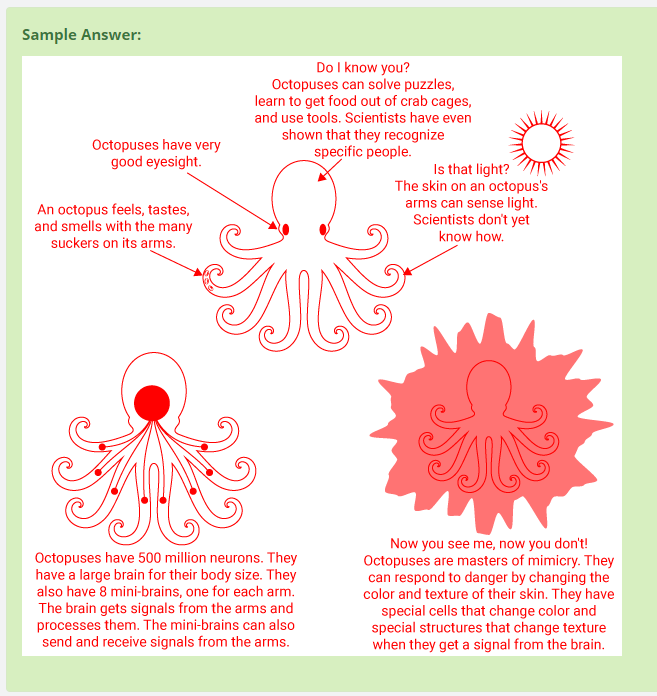

The global investment in research and development (R&D) is staggering. In 2019 alone, organizations around the world spent $2.3 trillion on R&D—the equivalent of roughly 2 percent of global GDP—about half of which came from industry and the remainder from governments and academic institutions. What’s more, that annual investment has been growing at approximately 4 percent per year over the past decade. 1 2.3 trillion on purchasing-power-parity basis; 2019 global R&D funding forecast , Supplement, R&D Magazine, March 2019, rdworldonline.com.

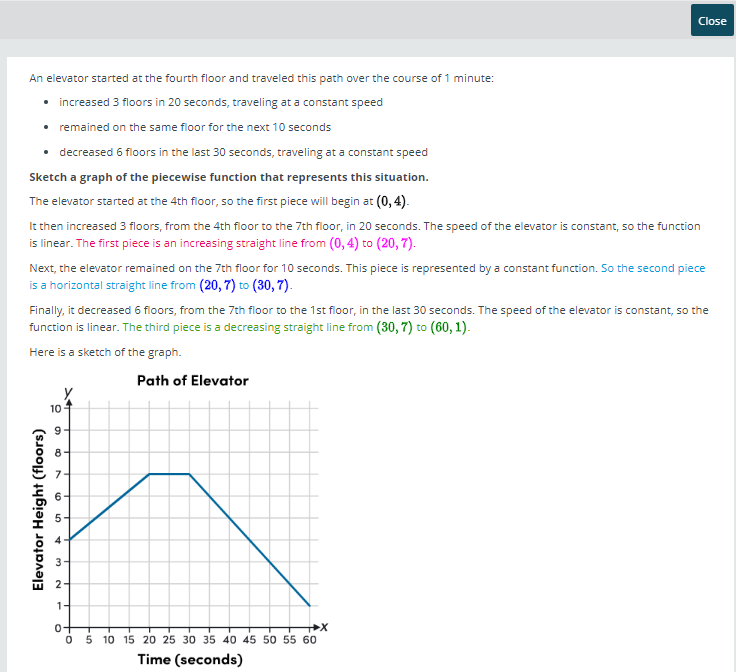

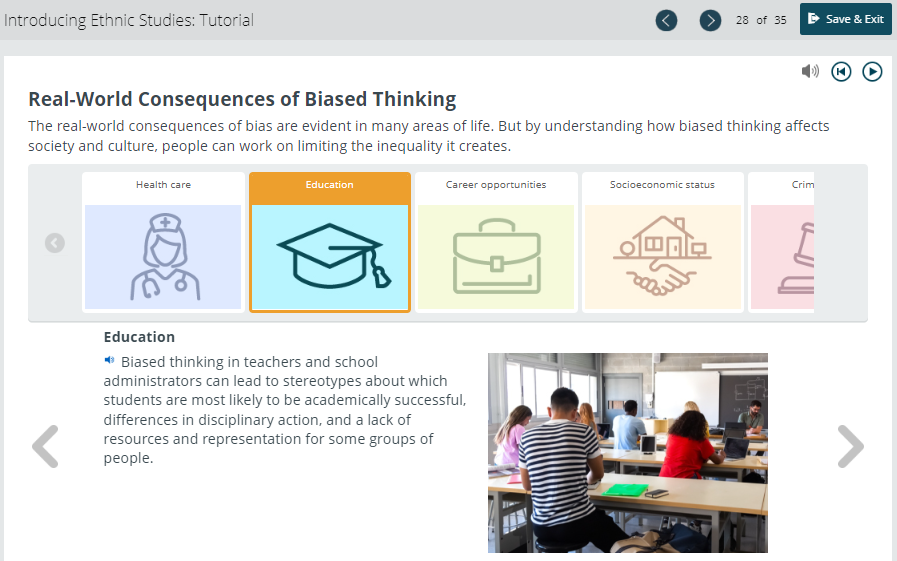

While the pharmaceutical sector garners much attention due to its high R&D spending as a percentage of revenues, a comparison based on industry profits shows that several industries, ranging from high tech to automotive to consumer, are putting more than 20 percent of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) back into innovation research (Exhibit 1).

What do organizations expect to get in return? At the core, they hope their R&D investments yield the critical technology from which they can develop new products, services, and business models. But for R&D to deliver genuine value, its role must be woven centrally into the organization’s mission. R&D should help to both deliver and shape corporate strategy, so that it develops differentiated offerings for the company’s priority markets and reveals strategic options, highlighting promising ways to reposition the business through new platforms and disruptive breakthroughs.

Yet many enterprises lack an R&D strategy that has the necessary clarity, agility, and conviction to realize the organization’s aspirations. Instead of serving as the company’s innovation engine, R&D ends up isolated from corporate priorities, disconnected from market developments, and out of sync with the speed of business. Amid a growing gap in performance between those that innovate successfully and those that do not, companies wishing to get ahead and stay ahead of competitors need a robust R&D strategy that makes the most of their innovation investments. Building such a strategy takes three steps: understanding the challenges that often work as barriers to R&D success, choosing the right ingredients for your strategy, and then pressure testing it before enacting it.

Overcoming the barriers to successful R&D

The first step to building an R&D strategy is to understand the four main challenges that modern R&D organizations face:

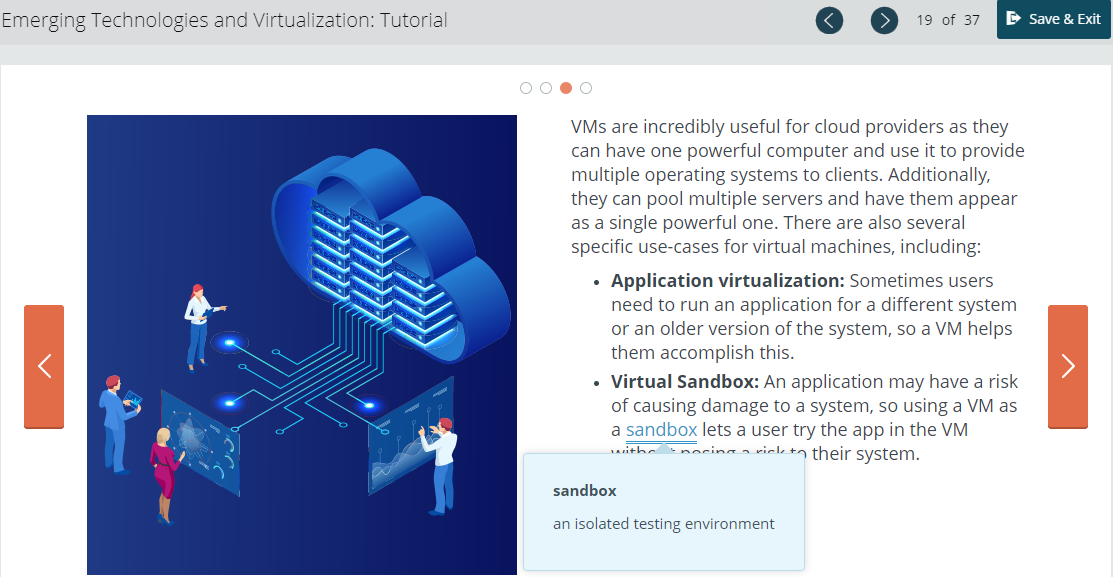

Innovation cycles are accelerating. The growing reliance on software and the availability of simulation and automation technologies have caused the cost of experimentation to plummet while raising R&D throughput. The pace of corporate innovation is further spurred by the increasing emergence of broadly applicable technologies, such as digital and biotech, from outside the walls of leading industry players.

But incumbent corporations are only one part of the equation. The trillion dollars a year that companies spend on R&D is matched by the public sector. Well-funded start-ups, meanwhile, are developing and rapidly scaling innovations that often threaten to upset established business models or steer industry growth into new areas. Add increasing investor scrutiny of research spending, and the result is rising pressure on R&D leaders to quickly show results for their efforts.

R&D lacks connection to the customer. The R&D group tends to be isolated from the rest of the organization. The complexity of its activities and its specialized lexicon make it difficult for others to understand what the R&D function really does. That sense of working inside a “black box” often exists even within the R&D organization. During a meeting of one large company’s R&D leaders, a significant portion of the discussion focused on simply getting everyone up to speed on what the various divisions were doing, let alone connecting those efforts to the company’s broader goals.

Given the challenges R&D faces in collaborating with other functions, going one step further and connecting with customers becomes all the more difficult. While many organizations pay lip service to customer-centric development, their R&D groups rarely get the opportunity to test products directly with end users. This frequently results in market-back product development that relies on a game of telephone via many intermediaries about what the customers want and need.

Projects have few accountability metrics. R&D groups in most sectors lack effective mechanisms to measure and communicate progress; the pharmaceutical industry, with its standard pipeline for new therapeutics that provides well-understood metrics of progress and valuation implications, is the exception, not the rule. When failure is explained away as experimentation and success is described in terms of patents, rather than profits, corporate leaders find it hard to quantify R&D’s contribution.

Yet proven metrics exist to effectively measure progress and outcomes. A common challenge we observe at R&D organizations, ranging from automotive to chemical companies, is how to value the contribution of a single component that is a building block of multiple products. One specialty-chemicals company faced this challenge in determining the value of an ingredient it used in its complex formulations. It created categorizations to help develop initial business cases and enable long-term tracking. This allowed pragmatic investment decisions at the start of projects and helped determine the value created after their completion.

Even with outcomes clearly measured, the often-lengthy period between initial investment and finished product can obscure the R&D organization’s performance. Yet, this too can be effectively managed by tracking the overall value and development progress of the pipeline so that the organization can react and, potentially, promptly reorient both the portfolio and individual projects within it.

Incremental projects get priority. Our research indicates that incremental projects account for more than half of an average company’s R&D investment, even though bold bets and aggressive reallocation of the innovation portfolio deliver higher rates of success. Organizations tend to favor “safe” projects with near-term returns—such as those emerging out of customer requests—that in many cases do little more than maintain existing market share. One consumer-goods company, for example, divided the R&D budget among its business units, whose leaders then used the money to meet their short-term targets rather than the company’s longer-term differentiation and growth objectives.

Focusing innovation solely around the core business may enable a company to coast for a while—until the industry suddenly passes it by. A mindset that views risk as something to be avoided rather than managed can be unwittingly reinforced by how the business case is measured. Transformational projects at one company faced a higher internal-rate-of-return hurdle than incremental R&D, even after the probability of success had been factored into their valuation, reducing their chances of securing funding and tilting the pipeline toward initiatives close to the core.

As organizations mature, innovation-driven growth becomes increasingly important, as their traditional means of organic growth, such as geographic expansion and entry into untapped market segments, diminish. To succeed, they need to develop R&D strategies equipped for the modern era that treat R&D not as a cost center but as the growth engine it can become.

Would you like to learn more about our Strategy & Corporate Finance Practice ?

Choosing the ingredients of a winning r&d strategy.

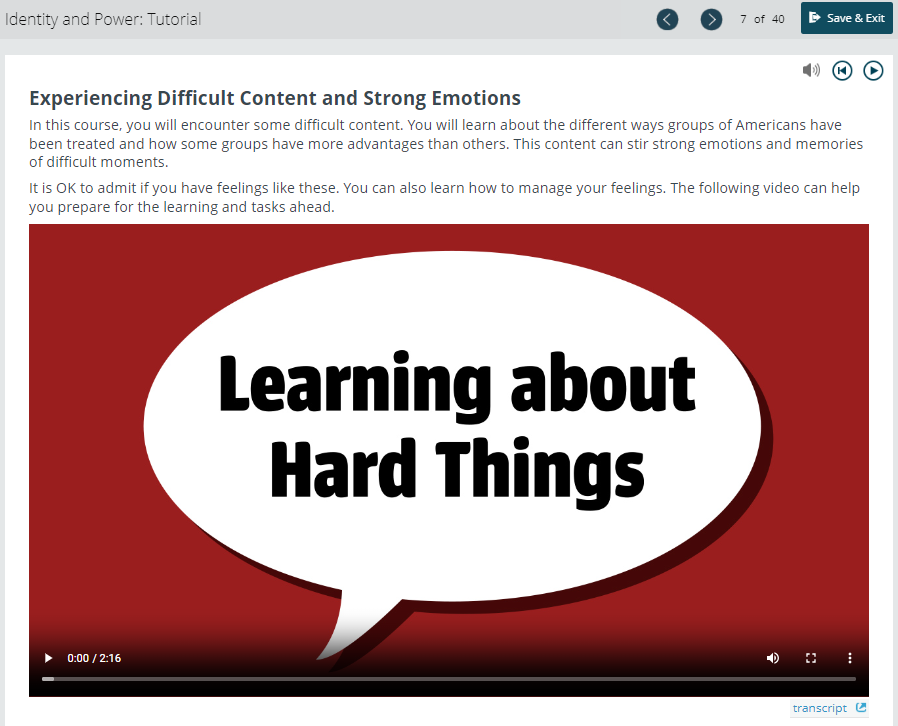

Given R&D’s role as the innovation driver that advances the corporate agenda, its guiding strategy needs to link board-level priorities with the technologies that are the organization’s focus (Exhibit 2). The R&D strategy must provide clarity and commitment to three central elements: what we want to deliver, what we need to deliver it, and how we will deliver it.

What we want to deliver. To understand what a company wants to and can deliver, the R&D, commercial, and corporate-strategy functions need to collaborate closely, with commercial and corporate-strategy teams anchoring the R&D team on the company’s priorities and the R&D team revealing what is possible. The R&D strategy and the corporate strategy must be in sync while answering questions such as the following: At the highest level, what are the company’s goals? Which of these will require R&D in order to be realized? In short, what is the R&D organization’s purpose?

Bringing the two strategies into alignment is not as easy as it may seem. In some companies, what passes for corporate strategy is merely a five-year business plan. In others, the corporate strategy is detailed but covers only three to five years—too short a time horizon to guide R&D, especially in industries such as pharma or semiconductors where the product-development cycle is much longer than that. To get this first step right, corporate-strategy leaders should actively engage with R&D. That means providing clarity where it is lacking and incorporating R&D feedback that may illuminate opportunities, such as new technologies that unlock growth adjacencies for the company or enable completely new business models.

Secondly, the R&D and commercial functions need to align on core battlegrounds and solutions. Chief technology officers want to be close to and shape the market by delivering innovative solutions that define new levels of customer expectations. Aligning R&D strategy provides a powerful forum for identifying those opportunities by forcing conversations about customer needs and possible solutions that, in many companies, occur only rarely. Just as with the corporate strategy alignment, the commercial and R&D teams need to clearly articulate their aspirations by asking questions such as the following: Which markets will make or break us as a company? What does a winning product or service look like for customers?

When defining these essential battlegrounds, companies should not feel bound by conventional market definitions based on product groups, geographies, or customer segments. One agricultural player instead defined its markets by the challenges customers faced that its solutions could address. For example, drought resistance was a key battleground no matter where in the world it occurred. That framing clarified the R&D–commercial strategy link: if an R&D project could improve drought resistance, it was aligned to the strategy.

The dialogue between the R&D, commercial, and strategy functions cannot stop once the R&D strategy is set. Over time, leaders of all three groups should reexamine the strategic direction and continuously refine target product profiles as customer needs and the competitive landscape evolve.

What we need to deliver it. This part of the R&D strategy determines what capabilities and technologies the R&D organization must have in place to bring the desired solutions to market. The distinction between the two is subtle but important. Simply put, R&D capabilities are the technical abilities to discover, develop, or scale marketable solutions. Capabilities are unlocked by a combination of technologies and assets, and focus on the outcomes. Technologies, however, focus on the inputs—for example, CRISPR is a technology that enables the genome-editing capability.

This delineation protects against the common pitfall of the R&D organization fixating on components of a capability instead of the capability itself—potentially missing the fact that the capability itself has evolved. Consider the dawn of the digital age: in many engineering fields, a historical reliance on talent (human number crunchers) was suddenly replaced by the need for assets (computers). Those who focused on hiring the fastest mathematicians were soon overtaken by rivals who recognized the capability provided by emerging technologies.

The simplest way to identify the needed capabilities is to go through the development processes of priority solutions step by step—what will it take to produce a new product or feature? Being exhaustive is not the point; the goal is to identify high-priority capabilities, not to log standard operating procedures.

Prioritizing capabilities is a critical but often contentious aspect of developing an R&D strategy. For some capabilities, being good is sufficient. For others, being best in class is vital because it enables a faster path to market or the development of a better product than those of competitors. Take computer-aided design (CAD), which is used to design and prototype engineering components in numerous industries, such as aerospace or automotive. While companies in those sectors need that capability, it is unlikely that being the best at it will deliver a meaningful advantage. Furthermore, organizations should strive to anticipate which capabilities will be most important in the future, not what has mattered most to the business historically.

Once capabilities are prioritized, the R&D organization needs to define what being “good” and “the best” at them will mean over the course of the strategy. The bar rises rapidly in many fields. Between 2009 and 2019, the cost of sequencing a genome dropped 150-fold, for example. 2 Kris A. Wetterstrand, “DNA sequencing costs: Data,” NHGRI Genome Sequencing Program (GSP), August 25, 2020, genome.gov. Next, the organization needs to determine how to develop, acquire, or access the needed capabilities. The decision of whether to look internally or externally is crucial. An automatic “we can build it better” mindset diminishes the benefits of specialization and dilutes focus. Additionally, the bias to building everything in-house can cut off or delay access to the best the world has to offer—something that may be essential for high-priority capabilities. At Procter & Gamble, it famously took the clearly articulated aspiration of former CEO A. G. Lafley to break the company’s focus on in-house R&D and set targets for sourcing innovation externally. As R&D organizations increasingly source capabilities externally, finding partners and collaborating with them effectively is becoming a critical capability in its own right.

How we will do it. The choices of operating model and organizational design will ultimately determine how well the R&D strategy is executed. During the strategy’s development, however, the focus should be on enablers that represent cross-cutting skills and ways of working. A strategy for attracting, developing, and retaining talent is one common example.

Another is digital enablement, which today touches nearly every aspect of what the R&D function does. Artificial intelligence can be used at the discovery phase to identify emerging market needs or new uses of existing technology. Automation and advanced analytics approaches to experimentation can enable high throughput screening at a small scale and distinguish the signal from the noise. Digital (“in silico”) simulations are particularly valuable when physical experiments are expensive or dangerous. Collaboration tools are addressing the connectivity challenges common among geographically dispersed project teams. They have become indispensable in bringing together existing collaborators, but the next horizon is to generate the serendipity of chance encounters that are the hallmark of so many innovations.

Testing your R&D strategy

Developing a strategy for the R&D organization entails some unique challenges that other functions do not face. For one, scientists and engineers have to weigh considerations beyond their core expertise, such as customer, market, and economic factors. Stakeholders outside R&D labs, meanwhile, need to understand complex technologies and development processes and think along much longer time horizons than those to which they are accustomed.

For an R&D strategy to be robust and comprehensive enough to serve as a blueprint to guide the organization, it needs to involve stakeholders both inside and outside the R&D group, from leading scientists to chief commercial officers. What’s more, its definition of capabilities, technologies, talent, and assets should become progressively more granular as the strategy is brought to life at deeper levels of the R&D organization. So how can an organization tell if its new strategy passes muster? In our experience, McKinsey’s ten timeless tests of strategy apply just as well to R&D strategy as to corporate and business-unit strategies. The following two tests are the most important in the R&D context:

- Does the organization’s strategy tap the true source of advantage? Too often, R&D organizations conflate technical necessity (what is needed to develop a solution) with strategic importance (distinctive capabilities that allow an organization to develop a meaningfully better solution than those of their competitors). It is also vital for organizations to regularly review their answers to this question, as capabilities that once provided differentiation can become commoditized and no longer serve as sources of advantage.

- Does the organization’s strategy balance commitment-rich choices with flexibility and learning? R&D strategies may have relatively long time horizons but that does not mean they should be insulated from changes in the outside world and never revisited. Companies should establish technical, regulatory, or other milestones that serve as clear decision points for shifting resources to or away from certain research areas. Such milestones can also help mark progress and gauge whether strategy execution is on track.

Additionally, the R&D strategy should be simply and clearly communicated to other functions within the company and to external stakeholders. To boost its clarity, organizations might try this exercise: distill the strategy into a set of fill-in-the-blank components that define, first, how the world will evolve and how the company plans to refocus accordingly (for example, industry trends that may lead the organization to pursue new target markets or segments); next, the choices the R&D function will make in order to support the company’s new focus (which capabilities will be prioritized and which de-emphasized); and finally, how the R&D team will execute the strategy in terms of concrete actions and milestones. If a company cannot fit the exercise on a single page, it has not sufficiently synthesized the strategy—as the famed physicist Richard Feynman observed, the ultimate test of comprehension is the ability to convey something to others in a simple manner.

Cascading the strategy down through the R&D organization will further reinforce its impact. For example, asking managers to communicate the strategy to their subordinates will deepen their own understanding. A useful corollary is that those hearing the strategy for the first time are introduced to it by their immediate supervisors rather than more distant R&D leaders. One R&D group demonstrated the broad benefits of this communication model: involving employees in developing and communicating the R&D strategy helped it double its Organizational Health Index strategic clarity score, which measures one of the four “power practices” highly connected to organizational performance.

R&D represents a massive innovation investment, but as companies confront globalized competition, rapidly changing customer needs, and technological shifts coming from an ever-wider range of fields, they are struggling to deliver on R&D’s full potential. A clearly articulated R&D strategy that supports and informs the corporate strategy is necessary to maximize the innovation investment and long-term company value.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

The innovation commitment

The eight essentials of innovation

The Committed Innovator: An interview with Salesforce’s Simon Mulcahy

Research and Development (R&D)

- Reference work entry

- pp 5516–5517

- Cite this reference work entry

- Sakari Kainulainen 3

544 Accesses

Mode 2 knowledge production (Mode 2) ; Mode 2 knowledge production ; Research and development and innovations (R&D&I)

Research and development (R&D) is a broad category describing the entity of basic research, applied research, and development activities. In general research and development means systematic activities in order to increase knowledge and use of this knowledge when developing new products, processes, or services. Nowadays innovation activities are strongly tight into the concept of research and development. In the broadest meaning, research and development consists of every activity from the basic research to the (successful) marketing of a product or (effective) launching of a new process (R&D&I).

Description

Research and development work is mostly related to business organizations. Development activities are targeted for them to development of new products and their success within the markets. A new product can be seen as the end of the chain of which...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Nowotny, H., Schwartzman, S., Scott, P., & Trow, M. (1994). The new production of knowledge: The dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies . London: Sage.

Google Scholar

Gulbrandsen, M. The role of basic research in innovation. Confluence , 55 . Retrieved from http://www.cas.uio.no/Publications/Seminar/Confluence_Gulbrandsen.pdf

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Diaconia University of Applied Sciences, Sturenkatu 2, Helsinki, 00510, Finland

Sakari Kainulainen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sakari Kainulainen .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of Northern British Columbia, Prince George, BC, Canada

Alex C. Michalos

(residence), Brandon, MB, Canada

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Kainulainen, S. (2014). Research and Development (R&D). In: Michalos, A.C. (eds) Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_2482

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_2482

Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN : 978-94-007-0752-8

Online ISBN : 978-94-007-0753-5

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

How Does Research and Development Influence Design?

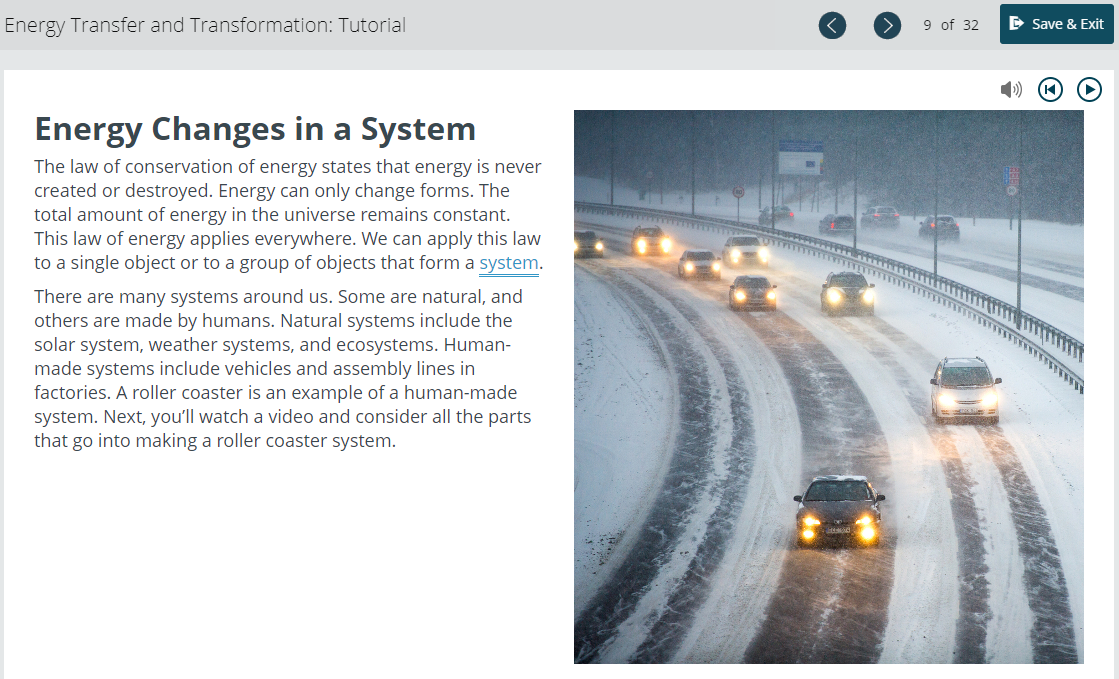

How does research and development influence design? Research and development (R&D) is an integral part of any product design process. From concept to completion, R&D teams help bring ideas to life by testing the feasibility of new products and features.

In this blog post, we will explore how research can be used to inform decisions throughout a project’s lifecycle as well as discuss best practices for maximizing the impact that R&D has on design outcomes. We’ll also look at how technology can enhance traditional methods of conducting research, allowing teams to gain valuable insights faster than ever before. So let’s answer: how does research and development influence design?

Table of Contents

The Role of R&D in Design Processes

Market research, user testing, prototyping, leveraging technology to enhance research and development efforts, data management, collaboration, analytics and insights, challenges of leveraging technologies, best practices for maximizing the impact of research and development on design outcomes, conclusion: how does research and development influence design.

Research and development help to identify problems, develop solutions, and create new products or services that meet customer needs. R&D can also be used to improve existing designs by identifying areas for improvement or creating innovative approaches to problem-solving. Let’s look closer and answer: how does research and development influence design?

R&D plays a critical role in the design process by providing insights into customer needs and preferences, as well as technological advancements that could impact product performance.

Through research activities such as market analysis, surveys, prototype testing, and data collection from competitors’ products or services, designers gain valuable information about what their target audience wants and how best to deliver it. This knowledge can then be used to inform decisions about product features, materials selection, and manufacturing processes, resulting in improved designs that better meet user requirements.

Market research is a critical component of product development as it provides insights into consumer behavior and preferences. Through market research, designers can gain a better understanding of their target audience’s needs and wants which allows them to create more effective designs that appeal to customers.

For example, if a company wanted to launch a new line of clothing they could use market research data such as surveys or focus groups to determine what type of styles people prefer so they could tailor their designs accordingly.

User testing is another important aspect of product development as it allows designers to get feedback from real users on how well their products perform in practice. This information can be used by designers when making decisions about features or functionality so they can ensure that the result meets user expectations.

For instance, if an app was being developed, then user testing would help identify any potential usability issues before it was released so adjustments could be made accordingly.

Prototyping is also essential for successful product development as it allows designers to test out ideas before committing resources towards full-scale production. By creating prototypes early on in the process, designers can quickly iterate on concepts until they find one that works best for their intended purpose without having wasted time or money on something that may not have been viable in the long run anyway.

For example, if an automotive manufacturer wanted to develop a new car model then prototyping would allow them to experiment with different body shapes and materials. This will help them find one suitable for mass production at scale while minimizing costs associated with trial-and-error approaches.

Key Takeaway: R&D is an essential part of the design process, providing valuable insights into customer needs and technological advancements that can be used to inform decisions about product features.

Now that we’ve answered “how does research and development influence design,” let’s look at how to enhance R&D efforts. Leveraging technology for research and development (R&D) efforts can be a powerful tool to help teams achieve their goals. Technology can provide access to data, facilitate collaboration, and enable faster decision-making. Here are some of the benefits of leveraging technology for R&D efforts:

Technology provides access to large amounts of data that would otherwise be difficult or impossible to obtain. It also allows teams to collaborate more effectively by enabling them to share information quickly and easily across multiple locations. Additionally, technology enables faster decision-making by providing real-time insights into trends in the market or industry as well as competitor activities.

Organizing data is a key part of research and development. Leveraging technology can help streamline the process, making it easier for teams to access and analyze data quickly.

For example, Cypris provides an integrated platform that centralizes all the data sources R&D teams need into one place. This allows them to easily search through their information without having to switch between multiple systems or manually compile reports.

Technology also helps facilitate collaboration among team members who may be located in different parts of the world. By leveraging cloud-based tools such as Google Docs or Slack, researchers can work together on projects from anywhere with an internet connection.

These tools allow users to share documents, have conversations in real-time, assign tasks, and more – all within a single platform. Additionally, they provide version control so everyone is always working off the same document or set of instructions at any given time.

Finally, technology makes it easier for teams to uncover insights from their research by providing powerful analytics capabilities right out of the box. With the right analytics, teams can quickly identify trends in their data, make informed decisions about future projects, and develop new products faster than ever before.

That’s why R&D teams need to have a platform that provides comprehensive insights into their data.

One challenge is ensuring that the right technology is selected based on an organization’s specific needs and objectives. Another challenge is ensuring that the chosen technology integrates seamlessly with existing systems within an organization’s infrastructure so it can be utilized efficiently without disrupting operations or introducing security risks. Finally, there may also be challenges related to cost considerations when implementing new technologies such as software licensing fees or hardware costs associated with deploying new systems or upgrading existing ones.

Key Takeaway: Technology can be a powerful tool for R&D teams to help them achieve their goals by providing access to data, facilitating collaboration, and enabling faster decision-making. However, organizations must consider cost considerations when selecting the right technology that integrates seamlessly with existing systems without introducing security risks.

Research and development (R&D) is an essential component of any successful design process. To maximize the impact of R&D on design outcomes, teams should focus on integrating research into their processes early and often.

This includes setting up a feedback loop between research and design to ensure that insights from research are informing decisions throughout the entire process. Additionally, teams should strive to create a culture where experimentation is encouraged, as this will allow them to explore different solutions quickly and efficiently.

Apple is one company that has successfully leveraged best practices for maximizing the impact of R&D on design outcomes. By creating a strong feedback loop between their research team and product designers, they have been able to rapidly develop innovative products such as iPhones and iPads.

Similarly, Amazon has also used its in-house research team to inform its product designs; by leveraging customer data collected through its platform, Amazon has been able to create highly personalized experiences tailored specifically to each user’s needs.

One challenge with implementing best practices for maximizing the impact of R&D on design outcomes is finding ways to effectively communicate insights from research back into product development cycles without sacrificing speed or efficiency. Additionally, it can be difficult to find ways to incentivize collaboration between researchers and designers so that both groups are working together towards common goals instead of operating independently from one another.

Finally, there may be organizational challenges associated with establishing an effective feedback loop between these two groups if they exist within separate departments or silos within an organization’s structure.

Key Takeaway: To maximize the impact of R&D on design outcomes, teams should focus on creating a feedback loop between research and design that encourages experimentation. Challenges may arise from communication issues or organizational silos, but with proper planning. these can be overcome.

How does research and development influence design? Research and development is an essential part of the design process, as it provides valuable insight into customer needs and preferences which can be used to inform decision-making throughout the entire product lifecycle.

By leveraging technology to enhance R&D efforts, teams can maximize their impact on product innovation and ensure they are making informed decisions based on data-driven insights. Ultimately, understanding how research and development influence design is key for any organization looking to stay ahead of the competition in today’s ever-evolving market landscape.

Are you an R&D or innovation team looking for a platform to accelerate your time to insights? Cypris is the perfect solution. Our research platform has been specifically designed with teams in mind and provides easy access to data sources that can help take your projects from concept to completion quickly. Take advantage of our innovative technology today and see how much faster your ideas become reality!

Similar insights you might enjoy

Gallium Nitride Innovation Pulse

Carbon Capture & Storage Innovation Pulse

Featured in:

Companies often spend resources on certain investigative undertakings in an effort to make discoveries that can help develop new products or way of doing things or work towards enhancing pre-existing products or processes. These activities come under the Research and Development (R&D) umbrella.

R&D is an important means for achieving future growth and maintaining a relevant product in the market . There is a misconception that R&D is the domain of high tech technology firms or the big pharmaceutical companies. In fact, most established consumer goods companies dedicate a significant part of their resources towards developing new versions of products or improving existing designs . However, where most other firms may only spend less than 5 percent of their revenue on research, industries such as pharmaceutical, software or high technology products need to spend significantly given the nature of their products.

© Shutterstock.com | Alexander Raths

In this article, we look at 1) types of R&D , 2) understanding similar terminology , 3) making the R&D decision , 4) basic R&D process , 5) creating an effective R&D process , 6) advantages of R&D , and 7) R&D challenges .

TYPES OF R&D

A US government agency, the National Science Foundation defines three types of R&D .

Basic Research

When research aims to understand a subject matter more completely and build on the body of knowledge relating to it, then it falls in the basic research category. This research does not have much practical or commercial application. The findings of such research may often be of potential interest to a company

Applied Research

Applied research has more specific and directed objectives. This type of research aims to determine methods to address a specific customer/industry need or requirement. These investigations are all focused on specific commercial objectives regarding products or processes.

Development

Development is when findings of a research are utilized for the production of specific products including materials, systems and methods. Design and development of prototypes and processes are also part of this area. A vital differentiation at this point is between development and engineering or manufacturing. Development is research that generates requisite knowledge and designs for production and converts these into prototypes. Engineering is utilization of these plans and research to produce commercial products.

UNDERSTANDING SIMILAR TERMINOLOGY

There are a number of terms that are often used interchangeably. Thought there is often overlap in all of these processes, there still remains a considerable difference in what they represent. This is why it is important to understand these differences.

The creation of new body of knowledge about existing products or processes, or the creation of an entirely new product is called R&D. This is systematic creative work, and the resulting new knowledge is then used to formulate new materials or entire new products as well as to alter and improve existing ones

Innovation includes either of two events or a combination of both of them. These are either the exploitation of a new market opportunity or the development and subsequent marketing of a technical invention. A technical invention with no demand will not be an innovation.

New Product Development

This is a management or business term where there is some change in the appearance, materials or marketing of a product but no new invention. It is basically the conversion of a market need or opportunity into a new product or a product upgrade

When an idea is turned into information which can lead to a new product then it is called design. This term is interpreted differently from country to country and varies between analytical marketing approaches to a more creative process.

Product Design

Misleadingly thought of as the superficial appearance of a product, product design actually encompasses a lot more. It is a cross functional process that includes market research, technical research, design of a concept, prototype creation, final product creation and launch . Usually, this is the refinement of an existing product rather than a new product.

MAKING THE R&D DECISION

Investment in R&D can be extensive and a long term commitment. Often, the required knowledge already exists and can be acquired for a price. Before committing to investment in R&D, a company needs to analyze whether it makes more sense to produce their own knowledge base or acquire existing work. The influence of the following factors can help make this decision.

Proprietariness

If the nature of the research is such that it can be protected through patents or non-disclosure agreements , then this research becomes the sole property of the company undertaking it and becomes much more valuable. Patents can allow a company several years of a head start to maximize profits and cement its position in the market. This sort of situation justifies the cost of the R&D process. On the other hand, if the research cannot be protected, then it may be easily copied by a competitor with little or no monetary expense. In this case, it may be a good idea to acquire research.

Setting up a R&D wing only makes sense if the market growth rate is slow or relatively moderate. In a fast paced environment, competitors may rush ahead before research has been completed, making the entire process useless.

Because of its nature, R&D is not always a guaranteed success commercially. In this regard, it may be desirable to acquire the required research to convert it into necessary marketable products. There is significantly less risk in acquisition as there may be an opportunity to test the technology out before formally purchasing anything.

Considering the long term potential success of a product, acquiring technology is less risky but more costly than generating own research. This is because license fees or royalties may need to be paid and there may even be an arrangement that requires payments tied to sales figures and may continue for as long as the license period. There is also the danger of geographical limitations or other restrictive caveats. In addition, if the technology changes mid license, all the investment will become a sunk cost. Setting up R&D has its own costs associated with it. There needs to be massive initial investment that leads to negative cash flow for a long time. But it does protect the company from the rest of the limitations of acquiring research.

All these aspects need to be carefully assessed and a pros vs. cons assessment needs to be conducted before the make or buy decision is finalized.

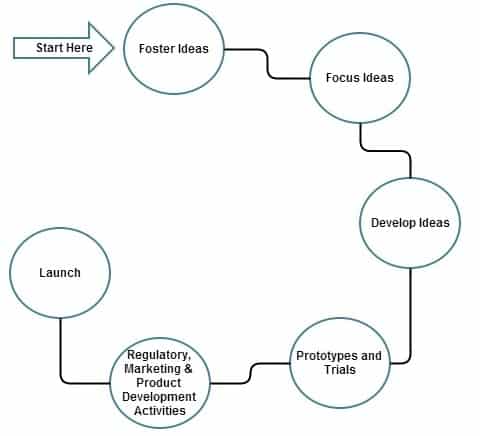

BASIC R&D PROCESS

Foster Ideas

At this point the research team may sit down to brainstorm. The discussion may start with an understanding and itemization of the issues faced in their particular industry and then narrowed down to important or core areas of opportunity or concern.

Focus Ideas

The initial pool of ideas is vast and may be generic. The team will then sift through these and locate ideas with potential or those that do not have insurmountable limitations. At this point the team may look into existing products and assess how original a new idea is and how well it can be developed.

Develop Ideas

Once an idea has been thoroughly researched, it may be combined with a market survey to assess market readiness. Ideas with true potential are once again narrowed down and the process of turning research into a marketable commodity begins.

Prototypes and Trials

Researchers may work closely with product developers to understand and agree on how an idea may be turned into a practical product. As the process iterates, the prototype complexity may start to increase and issues such as mass production and sales tactics may begin to enter the process.

Regulatory, Marketing & Product Development Activities

As the product takes shape, the process that began with R&D divides into relevant areas necessary to bring the research product to the market. Regulatory aspects are assessed and work begins to meet all the criteria for approvals and launch. The marketing function begins developing strategies and preparing their materials while sales, pricing and distribution are also planned for.

The product that started as a research question will now be ready for its biggest test, the introduction to the market. The evaluation of the product continues at this stage and beyond, eventually leading to possible re-designs if needed. At any point in this process the idea may be abandoned. Its feasibility may be questioned or the research may not reveal what the business hoped for. It is therefore important to analyze each idea critically at every stage and not become emotionally invested in anything.

CREATING AN EFFECTIVE R&D PROCESS

A formal R&D function adds great value to any organization. It can significantly contribute towards organizational growth and sustained market share. However, all business may not have the necessary resources to set up such a function. In such cases, or in organizations where a formal R&D function is not really required, it is a good idea to foster an R&D mindset . When all employees are encouraged to think creatively and with a research oriented thought process, they all feel invested in the business and there will be the possibility of innovation and unique ideas and solutions. This mindset can be slowly inculcated within the company by following the steps mentioned below.

Assess Customer Needs

It is a good idea to regularly scan and assess the market and identify whether the company’s offering is doing well or if it is in trouble. If it is successful, encourage employees to identify reasons for success so that these can then be used as benchmarks or best practices. If the product is not doing well, then encourage teams to research reasons why. Perhaps a competitor is offering a better solution or perhaps the product cannot meet the customer’s needs effectively.

Identify Objectives

Allow your employees to see clearly what the business objectives are. The end goal for a commercial enterprise is to enhance profits. If this is the case, then all research the employees engage in should focus on reaching this goal while fulfilling a customer need.

Define and Design Processes

A definite project management process helps keep formal and informal research programs on schedule. Realistic goals and targets help focus the process and ensures that relevant and realistic timelines are decided upon.

Create a Team

A team may need to be created if a specific project is on the agenda. This team should be cross functional and will be able to work towards a specific goal in a systematic manner. If the surrounding organizational environment also has a research mindset then they will be better prepared and suited to assist the core team when ever needed.

Whenever needed, it may be a good idea to outsource research projects. Universities and specific research organizations can help achieve research objectives that may not be manageable within a limited organizational budget.

ADVANTAGES OF R&D

Though setting up an R&D function is not an easy task by any means, it has its unique advantages for the organization. These include the following.

Research and Development expenses are often tax deductible. This depends on the country of operations of course but a significant write-off can be a great way to offset large initial investments. But it is important to understand what kind of research activities are deductible and which ones are not. Generally, things like market research or an assessment of historical information are not deductible.

A company can use research to identify leaner and more cost effective means of manufacturing. This reduction in cost can either help provide a more reasonably priced product to the customer or increase the profit margin.

When an investor sets out to put their resources into any company, they tend to prefer those who can become market leaders and innovate constantly. An effective R&D function goes a long way in helping to achieve these objectives for a company. Investors see this as a proactive approach to business and they may end up financing the costs associated with maintaining this R&D function.

Recruitment

Top talent is also attracted to innovative companies doing exciting things. With a successful Research and Development function, qualified candidates will be excited to join the company.

Through R&D based developments, companies can acquire patents for their products. These can help them gain market advantage and cement their position in the industry. This one time product development can lead to long term profits.

R&D CHALLENGES

R&D also has many challenges associated with it. These may include the following.

Initial setup costs as well as continued investment are necessary to keep research work cutting edge and relevant. Not all companies may find it feasible to continue this expenditure.

Increased Timescales

Once a commitment to R&D is made, it may take many years for the actual product to reach the market and a number of years will be filled with no return on continued heavy investment.

Uncertain Results

Not all research that is undertaken yields results. Many ideas and solutions are scrapped midway and work has to start from the beginning.

Market Conditions

There is always the danger that a significant new invention or innovation will render years of research obsolete and create setbacks in the industry with competitors becoming front runners for the customer’s business.

It is important for any business to understand the advantages and disadvantages of engaging in Research and Development activities. Once these are studied, then the step can be taken towards becoming and R&D organization.

In the meanwhile, it is good practice to inculcate a research mind set and research oriented thinking within all employees, no matter what their functional area of expertise. This will help bring about new ideas, new solutions and an innovative way of approaching all business problems, whether small or large.

Comments are closed.

Related posts

6 Steps Help You Coach Employees Effectively

Most employers do not always review the performance of their employees except the traditional annual …

Data Storytelling Links Emotions and Rational Decisions

Did you know the human brain is more likely to take in information from a story over pure …

Mark Cuban’s 12 Rules for Startups

Mark Cuban is a billionaire investor and owner of the Dallas Mavericks, with a lot of experience …

408,000 + job opportunities

Not yet a member? Sign Up

join cleverism

Find your dream job. Get on promotion fasstrack and increase tour lifetime salary.

Post your jobs & get access to millions of ambitious, well-educated talents that are going the extra mile.

First name*

Company name*

Company Website*

E-mail (work)*

Login or Register

Password reset instructions will be sent to your E-mail.

Module 1: Lifespan Development

Developmental research designs, learning outcomes.

- Compare advantages and disadvantages of developmental research designs (cross-sectional, longitudinal, and sequential)