ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Impact of the covid-19 pandemic on physical and mental health in lower and upper middle-income asian countries: a comparison between the philippines and china.

- 1 College of Medicine, University of the Philippines Manila, Manila, Philippines

- 2 Faculty of Education, Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience, Huaibei Normal University, Huaibei, China

- 3 Department of Psychological Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

- 4 Southeast Asia One Health University Network, Chiang Mai, Thailand

- 5 Department of Psychological Medicine, National University Health System, Singapore, Singapore

- 6 Institute of Health Innovation and Technology (iHealthtech), National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

Objective: The differences between the physical and mental health of people living in a lower-middle-income country (LMIC) and upper-middle-income country (UMIC) during the COVID-19 pandemic was unknown. This study aimed to compare the levels of psychological impact and mental health between people from the Philippines (LMIC) and China (UMIC) and correlate mental health parameters with variables relating to physical symptoms and knowledge about COVID-19.

Methods: The survey collected information on demographic data, physical symptoms, contact history, and knowledge about COVID-19. The psychological impact was assessed using the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R), and mental health status was assessed by the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21).

Findings: The study population included 849 participants from 71 cities in the Philippines and 861 participants from 159 cities in China. Filipino (LMIC) respondents reported significantly higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress than Chinese (UMIC) during the COVID-19 ( p < 0.01) while only Chinese respondents' IES-R scores were above the cut-off for PTSD symptoms. Filipino respondents were more likely to report physical symptoms resembling COVID-19 infection ( p < 0.05), recent use of but with lower confidence on medical services ( p < 0.01), recent direct and indirect contact with COVID ( p < 0.01), concerns about family members contracting COVID-19 ( p < 0.001), dissatisfaction with health information ( p < 0.001). In contrast, Chinese respondents requested more health information about COVID-19. For the Philippines, student status, low confidence in doctors, dissatisfaction with health information, long daily duration spent on health information, worries about family members contracting COVID-19, ostracization, and unnecessary worries about COVID-19 were associated with adverse mental health. Physical symptoms and poor self-rated health were associated with adverse mental health in both countries ( p < 0.05).

Conclusion: The findings of this study suggest the need for widely available COVID-19 testing in MIC to alleviate the adverse mental health in people who present with symptoms. A health education and literacy campaign is required in the Philippines to enhance the satisfaction of health information.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 30 ( 1 ) and a pandemic on March 11, 2020 ( 2 ). COVID-19 predominantly presents with respiratory symptoms (cough, sneezing, and sore throat), along with fever, fatigue and myalgia. It is thought to spread through droplets, contaminated surfaces, and asymptomatic individuals ( 3 ). By the end of April, over 3 million people have been infected globally ( 4 ).

The first country to identify the novel virus as the cause of the pandemic was China. The authorities responded with unprecedented restrictions on movement. The response included stopping public transport before Chinese New Year, an annual event that sees workers' mass emigration to their hometowns, and a lockdown of whole cities and regions ( 1 ). Two new hospitals specifically designed for COVID-19 patients were rapidly built in Wuhan. Such measures help slow the transmission of COVID-19 in China. As of May 2, there are 83,959 confirmed cases and 4,637 deaths from the virus in China ( 4 ). The Philippines was also affected early by the current crisis. The first case was suspected on January 22, and the country reported the first death from COVID-19 outside of mainland China ( 5 ). Similar to China, the Philippines implemented lockdowns in Manila. Other measures included the closure of schools and allowing arrests for non-compliance with measures ( 6 ). At the beginning of May, the Philippines recorded 8,772 cases and 579 deaths ( 4 ).

China was one of the more severely affected countries in Asia in the early stage of pandemic ( 7 ) while the Philippines is still experiencing an upward trend in the COVID-19 cases ( 6 ). The gross national income (GNI) per capita of the Philippines and China are USD 3,830 and 9,460, respectively, were classified with lower (LMIC) and upper-middle-income countries (UMIC) by the Worldbank ( 8 ). During the COVID-19 pandemic, five high-income countries (HIC), including the United States, Italy, the United Kingdom, Spain, and France, account for 70% of global deaths ( 9 ). The HIC faced the following challenges: (1) the lack of personal protection equipment (PPE) for healthcare workers; (2) the delay in response strategy; (3) an overstretched healthcare system with the shortage of hospital beds, and (4) a large number of death cases from nursing homes ( 10 ). The COVID-19 crisis threatens to hit lower and middle-income countries due to lockdown excessively and economic recession ( 11 ). A systematic review on mental health in LMIC in Asia and Africa found that LMIC: (1) do not have enough mental health professionals; (2) the negative economic impact led to an exacerbation of mental issues; (3) there was a scarcity of COVID-19 related mental health research in Asian LMIC ( 12 ). This systematic review could not compare participants from different middle-income countries because each study used different questionnaires. During the previous Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic, the promotion of protective personal health practices to reduce transmission of the SARS virus was found to reduce the anxiety levels in the community ( 13 ).

Before COVID-19, previous studies found that stress might be a modifiable risk factor for depression in LMICs ( 14 ) and UMICs ( 15 – 17 ). Another study involving thirty countries found that unmodifiable risk factors for depression included female gender, and depression became more common in 2004 to 2014 compared to previous periods ( 18 ). Further, there were cultural differences in terms of patient-doctor relationship and attitudes toward healthcare systems before the COVID-19 pandemic. In China, <20% of the general public and medical professionals view the doctor and patient relationship as harmonious ( 19 ). In contrast, Filipino seemed to have more trust and be compliant to doctors' recommendations ( 20 ). Patient satisfaction was more important than hospital quality improvement to maintain patient loyalty to the Chinese healthcare system ( 21 ). For Filipinos, improvement in the quality of healthcare service was found to improve patients' satisfaction ( 22 ).

Based on the above studies, we have the following research questions: (1) whether COVID-19 pandemic could be an important stressor and risk factor for depression for the people living in LMIC and UMIC ( 23 ), (2) Are physical symptoms that resemble COVID-19 infection and other concerns be risk factors for adverse mental health? (3) Are knowledge of COVID-19 and health information protective factors for mental health? (4) Would there be any cultural differences in attitudes toward doctors and healthcare systems during the pandemic between China and the Philippines? We hypothesized that UMIC (China) would have better physical and mental health than LMIC (the Philippines). The aims of this study were (a) to compare the physical and mental health between citizens from an LMIC (the Philippines) and UMIC (China); (b) to correlate psychological impact, depression, anxiety, and stress scores with variables relating to physical symptoms, knowledge, and concerns about COVID-19 in people living in the Philippines (LMIC) and China (UMIC).

Study Design and Study Population

We conducted a cross-cultural and quantitative study to compare Filipinos' physical and mental health with Chinese during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study was conducted from February 28 to March 1 in China and March 28 to April 7, 2020 in the Philippines, when the number of COVID-19 daily reported cases increased in both countries. The Chinese participants were recruited from 159 cities and 27 provinces. The Filipino participants, on the other hand, were recruited from 71 cities and 40 provinces representing the Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao archipelago. A respondent-driven recruitment strategy was utilized in both countries. The recruitment started with a set of initial respondents who were associated with the Huaibei Normal University of China and the University of the Philippines Manila; who referred other participants by email and social network; these in turn refer other participants across different cities in China and the Philippines.

As both Chinese and Filipino governments recommended that the public minimize face-to-face interaction and isolate themselves during the study period, new respondents were electronically invited by existing study respondents. The respondents completed the questionnaires through an online survey platform (“SurveyStar,” Changsha Ranxing Science and Technology in China and Survey Monkey Online Survey in the Philippines). The Institutional Review Board of the University of Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board (UPMREB 2020-198-01) and Huaibei Normal University (China) approved the research proposal (HBU-IRB-2020-002). All respondents provided informed or implied consent. The collected data were anonymous and treated as confidential.

This study used the National University of Singapore COVID-19 questionnaire, and its psychometric properties had been established in the initial phase of the COVID-19 epidemic ( 24 ). The National University of Singapore COVID-19 questionnaire consisted of questions that covered several areas: (1) demographic data; (2) physical symptoms related to COVID-19 in the past 14 days; (3) contact history with COVID-19 in the past 14 days; and (4) knowledge and concerns about COVID-19.

Demographic data about age, gender, education, household size, marital status, parental status, and residential city in the past 14 days were collected. Physical symptoms related to COVID-19 included breathing difficulty, chills, coryza, cough, dizziness, fever, headache, myalgia, sore throat, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Respondents also rated their physical health status and stated their history of chronic medical illness. In the past 14 days, health service utilization variables included consultation with a doctor in the clinic, being quarantined by the health authority, recent testing for COVID-19 and medical insurance coverage. Knowledge and concerns related to COVID-19 included knowledge about the routes of transmission, level of confidence in diagnosis, source, and level of satisfaction of health information about COVID-19, the likelihood of contracting and surviving COVID-19 and the number of hours spent on viewing information about COVID-19 per day.

The psychological impact of COVID-19 was measured using the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R). The IES-R is a self-administered questionnaire that has been well-validated in the European and Asian population for determining the extent of psychological impact after exposure to a traumatic event (i.e., the COVID-19 pandemic) within one week of exposure ( 25 , 26 ). This 22-item questionnaire, composed of three subscales, aims to measure the mean avoidance, intrusion, and hyperarousal ( 27 ). The total IES-R score is divided into 0–23 (normal), 24–32 (mild psychological impact), 33–36 (moderate psychological impact) and >37 (severe psychological impact) ( 28 ). The total IES-R score > 24 suggests the presence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms ( 29 ).

The respondents' mental health status was measured using the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) and the calculation of scores was based on a previous Asian study ( 30 ). DASS has been demonstrated to be a reliable and valid measure in assessing mental health in Filipinos ( 31 – 33 ) and Chinese ( 34 , 35 ). IES-R and DASS-21 were previously used in research related to the COVID-19 epidemic ( 26 , 36 – 38 ).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic characteristics, physical symptom, and health service utilization variables, contact history variables, knowledge and concern variables, precautionary measure variables, and additional health information variables. To analyze the differences in the levels of psychological impact, levels of depression, anxiety and stress, the independent sample t -test was used to compare the mean score between the Filipino (LMIC) and Chinese (UMIC) respondents. The chi-squared test was used to analyze the differences in categorical variables between the two samples. We used linear regressions to calculate the univariate associations between independent and dependent variables, including the IES-S score and DASS stress, anxiety, and depression subscale scores for the Filipino and Chinese respondents separately with adjustment for age, marital status, and education levels. All tests were two-tailed, with a significance level of p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed on SPSS Statistic 21.0.

Demographic Characteristics and Their Association With Psychological Impact and Adverse Mental Health Status

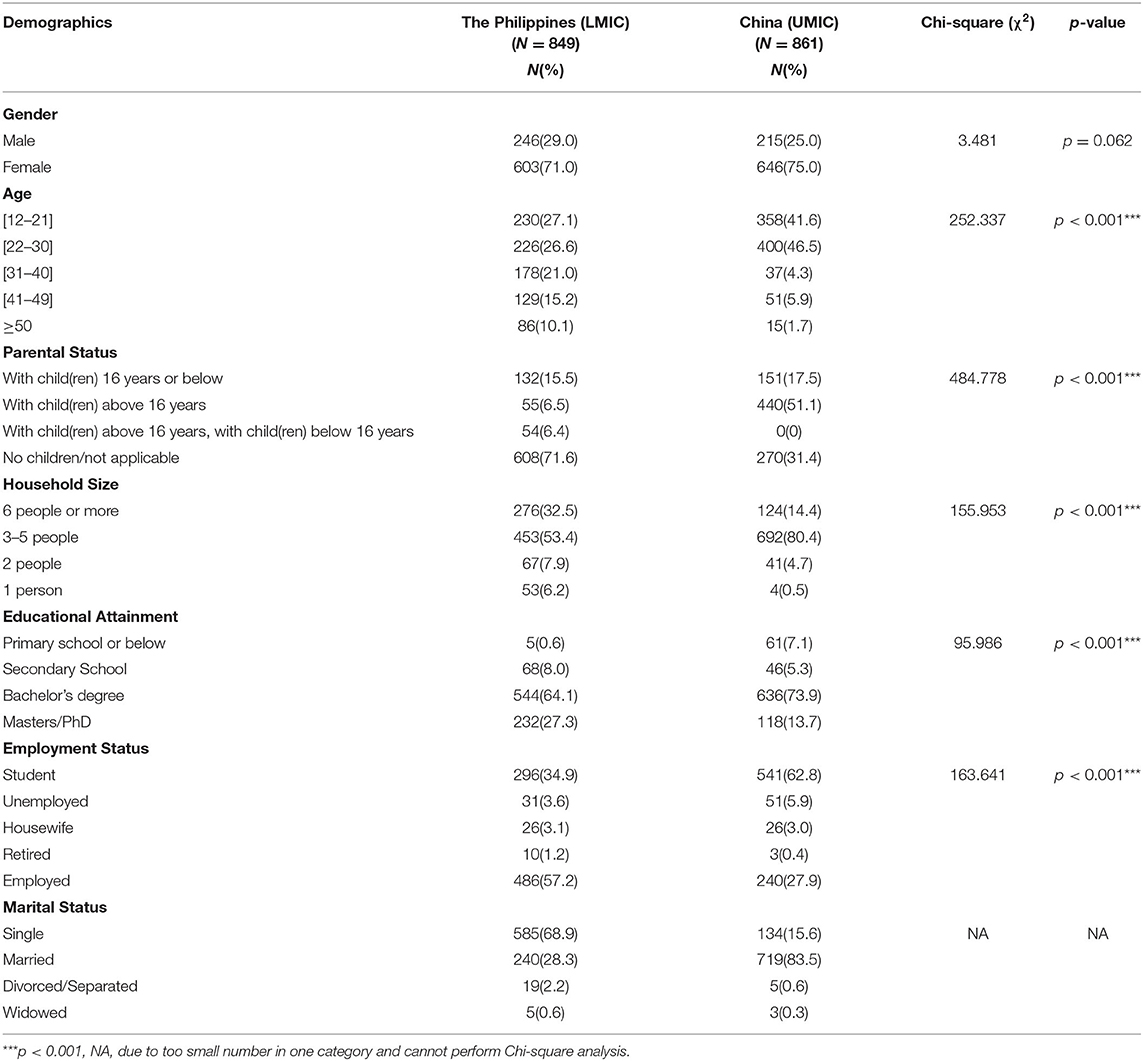

We received 849 responses from the Philippines and 861 responses from China for 1,710 individual respondents from both countries. The majority of Filipino respondents were women (71.0%), age between 22 and 30 years (26.6%), having a household size of 3–5 people (53.4%), high educational attainment (91.4% with a bachelor or higher degree), and married (68.9%). Similarly, the majority of Chinese respondents were women (75%), having a household size of 3–5 people (80.4%) and high educational attainment (91.4% with a bachelor or higher degree). There was a significantly higher proportion of Chinese respondents who had children younger than 16 years ( p < 0.001) and student status ( p < 0.001; See Table 1 ).

Table 1 . Comparison of demographic characteristics between Filipino (LMIC) and Chinese (UMIC) respondents ( N = 1,710).

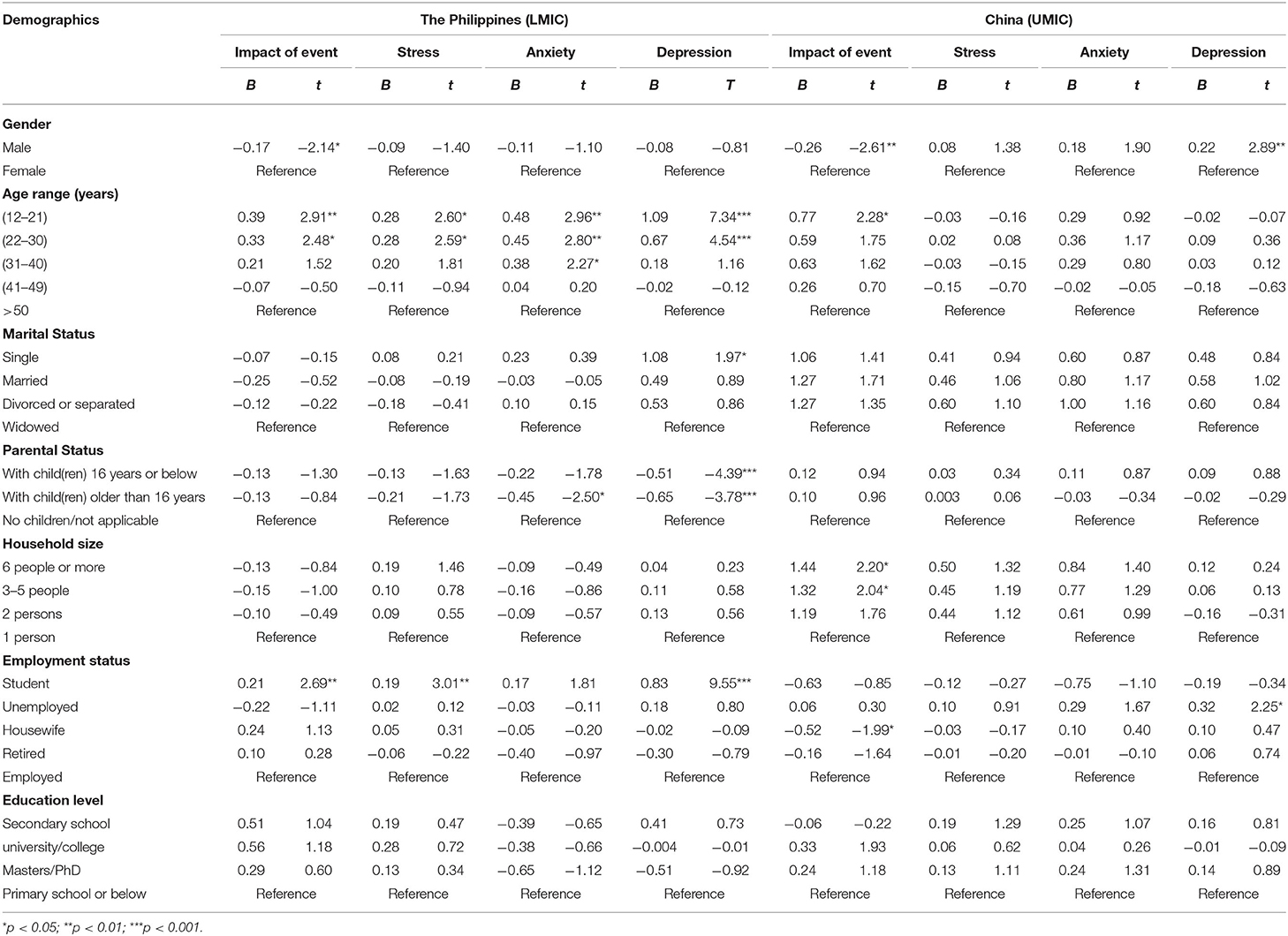

For Filipino respondents, the male gender and having a child were protective factors significantly associated with the lower score of IES-R ( p < 0.05) and depression ( p < 0.001), respectively. Single status was significantly associated with depression ( p < 0.05), and student status was associated with higher IES-R, stress and depression scores ( p < 0.01) (see Table 2 ). For Chinese respondents, the male gender was significantly associated with a lower score of IES-R but higher DASS depression scores ( p < 0.01). Notwithstanding, there were other differences between Filipino and China respondents. Chinese respondents who stayed in a household with 3–5 people ( p < 0.05) and more than 6 people ( p < 0.05) were significantly associated with a higher score of IES-R as compared to respondents who stayed alone.

Table 2 . Comparison of the association between demographic variables and the psychological impact as well as adverse mental health status between Filipino (LMIC) and Chinese (UMIC) respondents ( n = 1,710).

Comparison Between the Filipino (LMIC) and Chinese (UMIC) Respondents and Their Mental Health Status

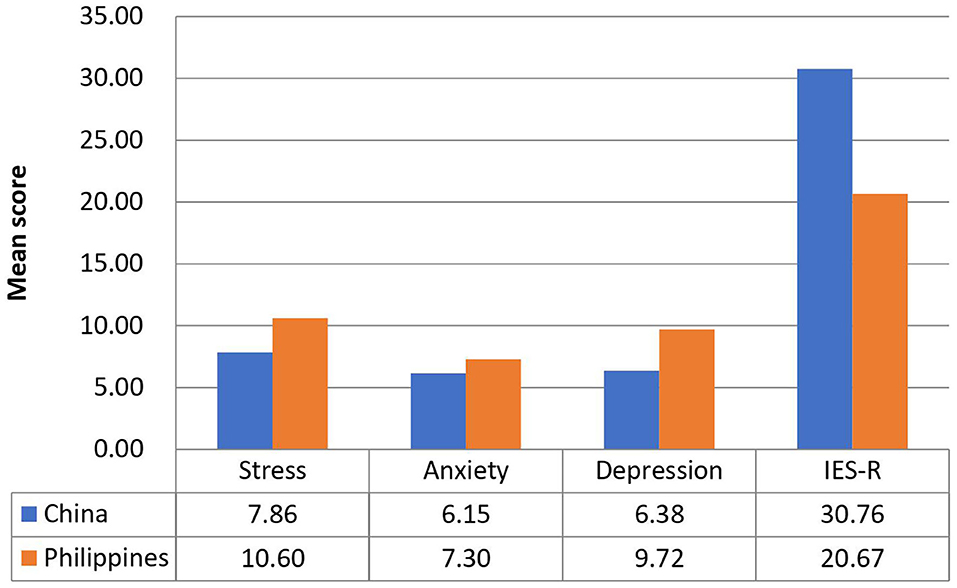

Figure 1 compares the mean scores of DASS-stress, anxiety, and depression subscales and IES-R scores between the Filipino and Chinese respondents. For the DASS-stress subscale, Filipino respondents reported significantly higher stress ( p < 0.001), anxiety ( p < 0.01), and depression ( p < 0.01) than Chinese (UMIC). For IES-R, Filipino (LMIC) had significantly lower scores than Chinese ( p < 0.001). The mean IES-R scores of Chinese were higher than 24 points, indicating the presence of PTSD symptoms in Chinese respondents only.

Figure 1 . Comparison of the mean scores of DASS-stress, anxiety and depression subscales, and IES-R scores between Filipino and Chinese respondents.

Physical Symptoms, Health Status, and Its Association With Psychological Impact and Adverse Mental Health Status

There were significant differences between Filipino (LMIC) and Chinese (UMIC) respondents regarding physical symptoms resembling COVID-19 and health status. There was a significantly higher proportion of Filipino respondents who reported headache ( p < 0.001), myalgia ( p < 0.001), cough ( p < 0.001), breathing difficulty ( p < 0.001), dizziness ( p < 0.05), coryza ( p < 0.001), sore throat ( p < 0.001), nausea and vomiting ( p < 0.001), recent consultation with a doctor ( p < 0.01), recent hospitalization ( p < 0.001), chronic illness ( p < 0.001), direct ( p < 0.001), and indirect ( p < 0.001) contact with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 as compared to Chinese (see Supplementary Table 1 ). Significantly more Chinese respondents were under quarantine ( p < 0.001).

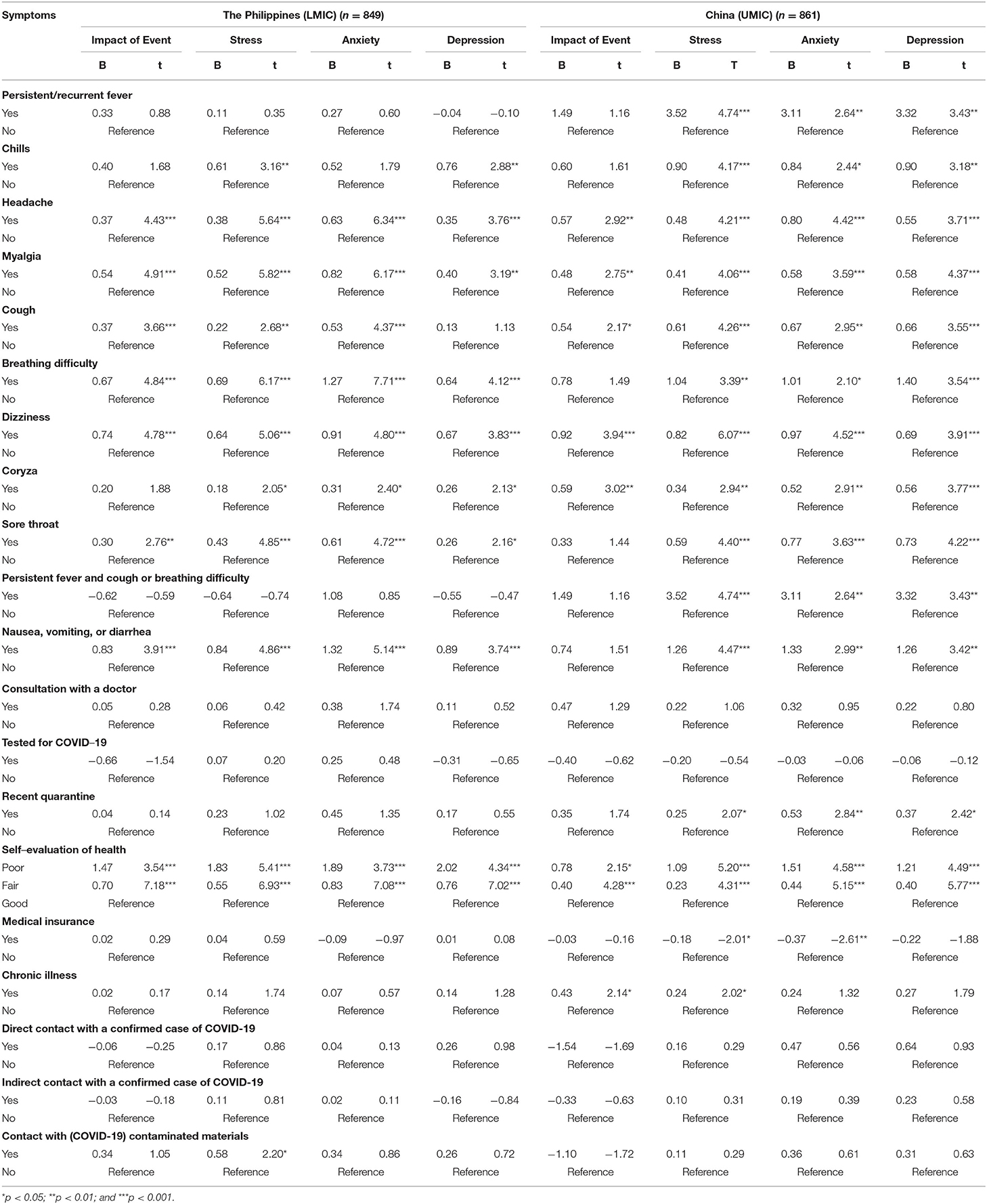

Linear regression showed that headache, myalgia, cough, dizziness, coryza as well as poor self-rated physical health were significantly associated with higher IES-R scores, DASS-21 stress, anxiety, and depression subscale scores in both countries after adjustment for confounding factors ( p < 0.05; see Table 3 ). Furthermore, breathing difficulty, sore throat, and gastrointestinal symptoms were significantly associated with higher DASS-21 stress, anxiety and depression subscale scores in both countries ( p < 0.05). Chills were significantly associated with higher DASS-21 stress and depression scores ( p < 0.01) in both countries. Recent quarantine was associated with higher DASS-21 subscale scores in Chinese respondents only ( p < 0.05).

Table 3 . Association between physical health status and contact history and the perceived impact of COVID-19 outbreak as well as adverse mental health status during the epidemic after adjustment for age, gender, and marital status ( n = 1,710).

Perception, Knowledge, and Concerns About COVID-19 and Its Association With Psychological Impact and Adverse Mental Health Status

Filipino (LMIC) and Chinese (UMIC) respondents held significantly different perceptions in terms of knowledge and concerns related to COVID-19 (see Supplementary Table 2 ). For the routes of transmission, there were significantly more Filipino respondents who agreed that droplets transmitted the COVID-19 ( p < 0.001) and contact via contaminated objects ( p < 0.001), but significantly more Chinese agreed with the airborne transmission ( p < 0.001). For the detection and risk of contracting COVID-19, there were significantly more Filipino who were not confident about their doctor's ability to diagnose COVID-19 ( p < 0.001). There were significantly more Filipino respondents who were worried about their family members contracting COVID-19 ( p < 0.001). For health information, there were significantly more Filipino who were unsatisfied with the amount of health information ( p < 0.001) and spent more than three hours per day on the news related to COVID-19 ( p < 0.001). There were significantly more Chinese respondents who felt ostracized by other countries ( p < 0.001).

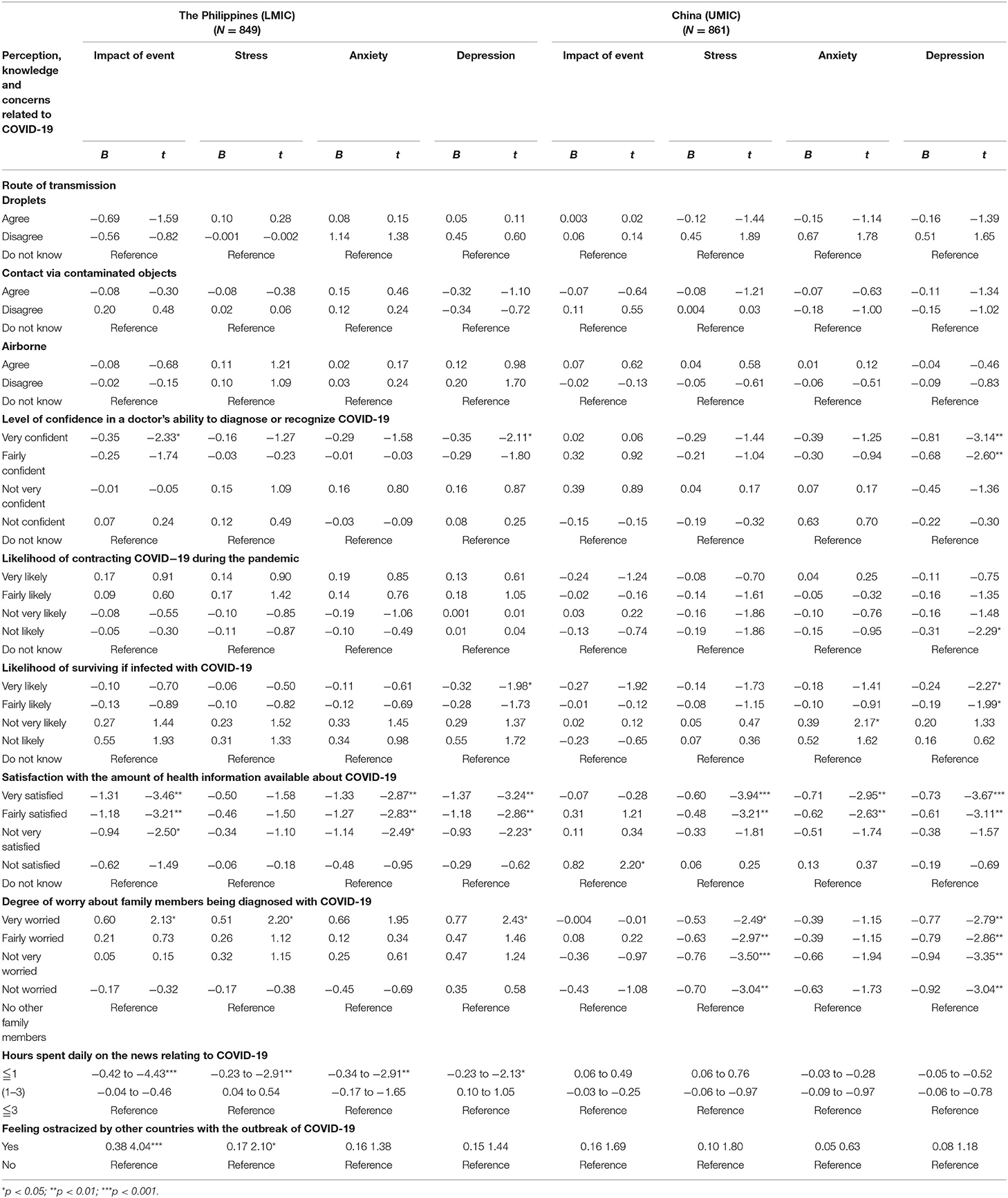

Linear regression analysis after adjustment of confounding factors showed that the Filipino and Chinese respondents showed different findings (see Table 4 ). Chinese respondents who reported a very low perceived likelihood of contracting COVID-19 were significantly associated with lower DASS depression scores ( p < 0.05). There were similarities between the two countries. Filipino and Chinese respondents who perceived a very high likelihood of survival were significantly associated with lower DASS-21 depression scores ( p < 0.05). Regarding the level of confidence in the doctor's ability to diagnose COVID-19, both Filipino and Chinese respondents who were very confident in their doctors were significantly associated with lower DASS-21 depression scores ( p < 0.01). Filipino and Chinese respondents who were satisfied with health information were significantly associated with lower DASS-21 anxiety and depression scores ( p < 0.01). Chinese and Filipino respondents who were worried about their family members contracting COVID-19 were associated with higher IES-R and DASS-21 subscale scores ( p < 0.05). In contrast, only Filipino respondents who spent <1 h per day monitoring COVID-19 information was significantly associated with lower IES-R and DASS-21 stress and anxiety scores ( p < 0.05). Filipino respondents who felt ostracized were associated with higher IES-R and stress scores ( p < 0.05).

Table 4 . Comparison of association of knowledge and concerns related to COVID-19 with mental health status after adjustment for age, gender, and marital status ( N = 1,710).

Health Information About COVID-19 and Its Association With Psychological Impact and Adverse Mental Health Status

Filipino (LMIC) and Chinese (UMIC) respondents held significantly different views on the information required about COVID-19. There were significantly more Chinese respondents who needed information on the symptoms related to COVID-19, prevention methods, management and treatment methods, regular information updates, more personalized information, the effectiveness of drugs and vaccines, number of infected by geographical locations, travel advice and transmission methods as compared to Filipino ( p < 0.01; See Supplementary Table 3 ). In contrast, there were significantly more Filipino respondents who needed information on other countries' strategies and responses than Chinese ( p < 0.001).

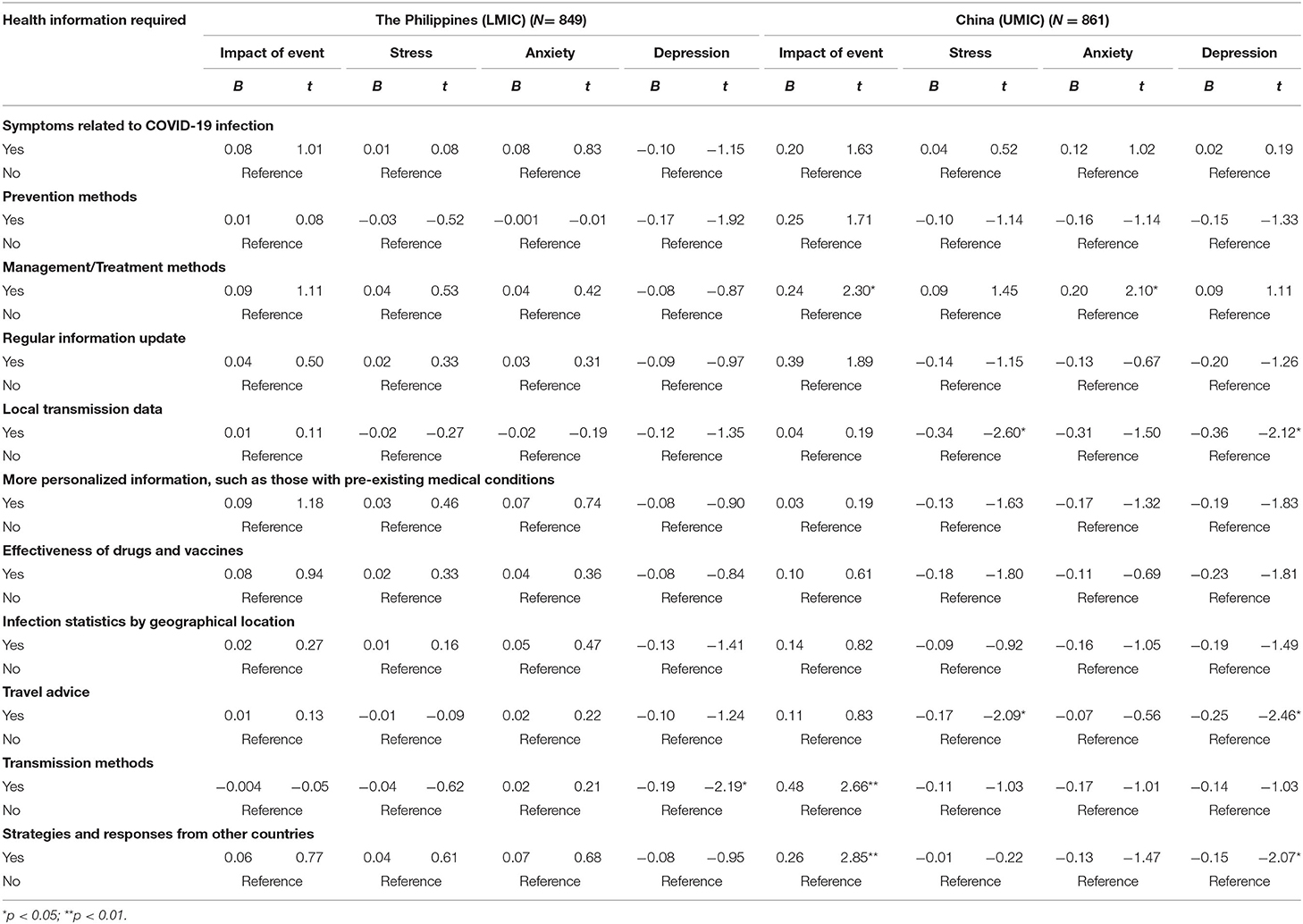

Information on management methods and transmission methods were significantly associated with higher IES-R scores in Chinese respondents ( p < 0.05; see Table 5 ). Travel advice, local transmission data, and other countries' responses were significantly associated with lower DASS-21 stress and depression scores in Chinese respondents only ( p < 0.05). There was only one significant association observed in Filipino respondents; information on transmission methods was significantly associated with lower DASS-21 depression scores ( p < 0.05).

Table 5 . Comparison of the association between information needs about COVID-19 and the psychological impact as well as adverse mental health status between Filipino (LMIC) and Chinese (UMIC) participants after adjustment for age, gender, and marital status ( N = 1,710).

To our best knowledge, this is the first study that compared the physical and mental health as well as knowledge, attitude and belief about COVID-19 between citizens from an LMIC (The Philippines) and UMIC (China). Filipino respondents reported significantly higher levels of depression, anxiety and stress than Chinese during the COVID-19, but only the mean IES-R scores of Chinese respondents were above the cut-off scores for PTSD symptoms. Filipino respondents were more likely to report physical symptoms resembling COVID-19 infection, recent use of medical services with lower confidence, recent direct, and indirect contact with COVID, concerns about family members contracting COVID-19 and dissatisfaction with health information. In contrast, Chinese respondents requested more health information about COVID-19 and were more likely to stay at home for more than 20–24 h per day. For the Filipino, student status, low confidence in doctors, unsatisfaction of health information, long hours spent on health information, worries about family members contracting COVID-19, ostracization, unnecessary worries about COVID-19 were associated with adverse mental health.

The most important implication of the present study is to understand the challenges faced by a sample of people from an LMIC (The Philippines) compared to a sample of people from a UMIC (China) in Asia. As physical symptoms resembling COVID-19 infection (e.g., headache, myalgia, dizziness, and coryza) were associated with adverse mental health in both countries, this association could be due to lack of confidence in healthcare system and lack of testing for coronavirus. Previous research demonstrated that adverse mental health such as depression could affect the immune system and lead to physical symptoms such as malaise and other somatic symptoms ( 39 , 40 ). Based on our findings, the strategic approach to safeguard physical and mental health for middle-income countries would be cost-effective and widely available testing for people present with COVID-19 symptoms, providing a high quality of health information about COVID-19 by health authorities.

Students were afraid that confinement and learning online would hinder their progress in their studies ( 41 ). This may explain why students from the Philippines reported higher levels of IES-R and depression scores. Schools and colleges should evaluate the blended implementation of online and face-to-face learning to optimize educational outcomes when local spread is under control. As a significantly higher proportion of Filipino respondents lack confidence in their doctors, health authorities should ensure adequate training and develop hospital facilities to isolate COVID-19 cases and prevent COVID-19 spread among healthcare workers and patients ( 42 ). Besides, our study found that Filipino respondents were dissatisfied with health information. In contrast, Chinese respondents demanded more health information related to COVID-19. The difference could be due to stronger public health campaign launched by the Chinese government including national health education campaigns, a health QR (Quick Response) code system and community engagement that effectively curtailed the spread of COVID-19 ( 43 ). The high expectation for health information could be explained by high education attainment of participants as about 91.4 and 87.6% of participants from China and the Philippines have a university education.

Furthermore, the governments must employ communication experts to craft information, education, and messaging materials that are target-appropriate to each level of understanding in the community. That the Chinese Government rapidly deployed medical personnel and treated COVID-19 patients at rapidly-built hospitals ( 44 ) is in itself a confidence-building measure. Nevertheless, recent quarantine was associated with higher DASS-21 subscale scores in Chinese respondents only. It could be due to stricter control and monitoring of movements imposed by the Chinese government during the lockdown ( 45 ). Chinese respondents who stayed with more than three family members were associated with higher IES-R scores. The high IES-R scores could be due to worries of the spread of COVID-19 to family members and overcrowded home environment during the lockdown. The Philippines also converted sports arena into quarantine/isolation areas for COVID-19 patients with mild symptoms. These prompt actions helped restore public confidence in the healthcare system ( 46 ). A recent study reported that cultural factors, demand pressure for information, the ease of information dissemination via social networks, marketing incentives, and the poor legal regulation of online contents are the main reasons for misinformation dissemination during the COVID-19 pandemic ( 47 ). Bastani and Bahrami ( 47 ) recommended the engagement of health professionals and authorities on social media during the pandemic and the improvement of public health literacy to counteract misinformation.

Chinese respondents were more likely to feel ostracized and Filipino respondents associated ostracization with adverse mental health. Recently, the editor-in-chief of The Lancet , Richard Horton, expressed concern of discrimination of a country or particular ethnic group, saying that while it is important to understand the origin and inter-species transmission of the coronavirus, it was both unhelpful and unscientific to point to a country as the origin of the Covid-19 pandemic, as such accusation could be highly stigmatizing and discriminatory ( 48 ). The global co-operation involves an exchange of expertise, adopting effective prevention strategies, sharing resources, and technologies among UMIC and LIMC to form a united front on tackling the COVID-19 pandemic remains a work in progress.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of this study lay in the fact that we performed in-depth analysis and studied the relationship between physical and mental outcomes and other variables related to COVID-19 in the Philippines and China. However, there are several limitations to be considered when interpreting the results. Although the Philippines is a LMIC and China is a UMIC, the findings cannot be generalized to other LIMCs and UMICs. Another limitation was the potential risk of sampling bias. This bias could be due to the online administration of questionnaires, and the majority of respondents from both countries were respondents with good educational attainment and internet access. We could not reach out to potential respondents without internet access (e.g., those who stayed in the countryside or remote areas). Further, our findings may not be generalizable to other middle-income countries.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Filipinos (LMIC) respondents reported significantly higher levels of depression, anxiety and stress than Chinese (UMIC). Filipino respondents were more likely to report physical symptoms resembling COVID-19 infection, recent use of medical services with lower confidence, recent direct and indirect contact with COVID, concerns about family members contracting COVID-19 and dissatisfaction with health information than Chinese. For the current COVID-19 and future pandemic, Middle income countries need to adopt the strategic approach to safeguard physical and mental health by establishing cost-effective and widely available testing for people who present with COVID-19 symptoms; provision of high quality and accurate health information about COVID-19 by health authorities. Our findings urge middle income countries to prevent ostracization of a particular ethnic group, learn from each other, and unite to address the challenge of the COVID-19 pandemic and safeguard physical and mental health.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board (UPMREB 2020- 198-01) and Huaibei Normal University (China) approved the research proposal (HBU-IRB-2020-002).

Author Contributions

Concept and design: CW, MT, CT, RP, VK, and RH. Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data: CW, MT, CT, RP, LX, CHa, XW, YT, and VK. Drafting of the manuscript: CW, MT, CT, RH, and JA. Critical revision of the manuscript: MT, CT, CHo, and JA. Statistical analysis: CW, PR, RP, LX, XW, and YT. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.568929/full#supplementary-material

1. Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O'Neill N, Khan M, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, et al. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int J Surg. (2020) 76:71–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Mahase E. Covid-19: WHO declares pandemic because of “alarming levels” of spread, severity, and inaction. BMJ. (2020) 368:m1036. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1036

3. Singhal T. A review of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19). Indian J. Pediatr. (2020) 87:281–6. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03263-6

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Oxford. Oxford U of. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) - Statistics and Research . (2020). Available online at: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus%0D (accessed May 17, 2020).

Google Scholar

5. Edrada EM, Lopez EB, Villarama JB, Salva Villarama EP, Dagoc BF, Smith C, et al. First COVID-19 infections in the Philippines: a case report. Trop Med Health. (2020) 48:21. doi: 10.1186/s41182-020-00218-7

6. CNN. TIMELINE: How the Philippines is Handling COVID-19. (2020). Available online at: https://cnnphilippines.com/news/2020/4/21/interactive-timeline-PH-handling-COVID-19.html (accessed May 17, 2020).

7. Worldmeters. COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. (2020). Available online at: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed December 4 2020).

8. WorldBank. World Bank National Accounts Data, and OECD National Accounts Data Files . (2020). Available online at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD (accessed April 16 2020).

9. Schellekens P, Sourrouille D. The Unreal Dichotomy in COVID-19 Mortality between High-Income and Developing Countries. (2020). Available online at: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2020/05/05/the-unreal-dichotomy-in-covid-19-mortality-between-high-income-and-developing-countries/ (accessed May 10 2020).

10. Medicalexpress. ‘Slow Response’: How Britain Became Worst-Hit in Europe by Virus. (2020). Available online at: https://medicalxpress.com/news/2020-05-response-britain-worst-hit-europe-virus.html (accessed May 8 2020).

11. Mamun MA, Ullah I. COVID-19 suicides in Pakistan, dying off not COVID-19 fear but poverty? - The forthcoming economic challenges for a developing country. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 87:163–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.028

12. Kar SK, Oyetunji TP, Prakash AJ, Ogunmola OA, Tripathy S, Lawal MM, et al. Mental health research in the lower-middle-income countries of Africa and Asia during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. Neurol Psychiatry Brain Res. (2020) 38:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.npbr.2020.10.003

13. Leung GM, Lam TH, Ho LM, Ho SY, Chan BH, Wong IO, et al. The impact of community psychological responses on outbreak control for severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2003) 57:857–63. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.11.857

14. Cristóbal-Narváez P, Haro JM, Koyanagi A. Perceived stress and depression in 45 low- and middle-income countries. J Affect Disord. (2020) 274:799–805. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.04.020

15. Vallejo MA, Vallejo-Slocker L, Fernández-Abascal EG, Mañanes G. Determining factors for stress perception assessed with the perceived stress scale (PSS-4) in Spanish and other European samples. Front Psychol. (2018) 9:37. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00037

16. Shin C, Kim Y, Park S, Yoon S, Ko YH, Kim YK, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of depression in general population of Korea: results from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2014. J Korean Med Sci. (2017) 32:1861–9. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.11.1861

17. Olsen LR, Mortensen EL, Bech P. Prevalence of major depression and stress indicators in the Danish general population. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2004) 109:96–103. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-690X.2003.00231.x

18. Lim GY, Tam WW, Lu Y, Ho CS, Zhang MW, Ho RC. Prevalence of depression in the community from 30 countries between 1994 and (2014). Sci Rep. (2018) 8:2861. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21243-x

19. Sang T, Zhou H, Li M, Li W, Shi H, Chen H, et al. Investigation of the differences between the medical personnel's and general population's view on the doctor-patient relationship in China by a cross-sectional survey. Global Health. (2020) 16:99. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-41725/v2

20. Ferrer RR, Ramirez M, Beckman LJ, Danao LL, Ashing-Giwa KT. The impact of cultural characteristics on colorectal cancer screening adherence among Filipinos in the United States: a pilot study. Psychooncology. (2011) 20:862–70. doi: 10.1002/pon.1793

21. Lei P, Jolibert A. A three-model comparison of the relationship between quality, satisfaction and loyalty: an empirical study of the Chinese healthcare system. BMC Health Serv Res. (2012) 12:436. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-436

22. Peabody JW, Florentino J, Shimkhada R, Solon O, Quimbo S. Quality variation and its impact on costs and satisfaction: evidence from the QIDS study. Med Care. (2010) 48:25–30. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181bd47b2

23. Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, Lui LMW, Gill H, Phan L, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. (2020) 277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001

24. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, McIntyre RS, et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 87:40–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028

25. Zhang MW, Ho CS, Fang P, Lu Y, Ho RC. Usage of social media and smartphone application in assessment of physical and psychological well-being of individuals in times of a major air pollution crisis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2014) 2:e16. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.2827

26. Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Tan BYQ, Jing M, Goh Y, Ngiam NJH, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 88:559–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049

27. Zhang MWB, Ho CSH, Fang P, Lu Y, Ho RCM. Methodology of developing a smartphone application for crisis research and its clinical application. Technol Health Care. (2014) 22:547–59. doi: 10.3233/THC-140819

28. Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S. Psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale - Revised. Behav Res Ther. (2003) 41:1489–96. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.010

29. Lee SM, Kang WS, Cho A-R, Kim T, Park JK. Psychological impact of the 2015 MERS outbreak on hospital workers and quarantined hemodialysis patients. Compr Psychiatry. (2018) 87:123–7. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.10.003

30. Le TA, Le MQT, Dang AD, Dang AK, Nguyen CT, Pham HQ, et al. Multi-level predictors of psychological problems among methadone maintenance treatment patients in difference types of settings in Vietnam. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. (2019) 14:39. doi: 10.1186/s13011-019-0223-4

31. Cheung JTK, Tsoi VWY, Wong KHK, Chung RY. Abuse and depression among Filipino foreign domestic helpers. A cross-sectional survey in Hong Kong. Public Health. (2019) 166:121–7. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.09.020

32. Tee ML, Tee CA, Anlacan JP, Aligam KJG, Reyes PWC, Kuruchittham V, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines. J Affect Disord. (2020) 277:379–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.043

33. Tee CA, Salido EO, Reyes PWC, Ho RC, Tee ML. Psychological State and Associated Factors During the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic among filipinos with rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus. Open Access Rheumatol. (2020) 12:215–22. doi: 10.2147/OARRR.S269889

34. Ho CSH, Tan ELY, Ho RCM, Chiu MYL. Relationship of anxiety and depression with respiratory symptoms: comparison between depressed and non-depressed smokers in Singapore. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:163. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16010163

35. Quek TC, Ho CS, Choo CC, Nguyen LH, Tran BX, Ho RC. Misophonia in Singaporean psychiatric patients: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:1410. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15071410

36. Hao F, Tan W, Jiang L, Zhang L, Zhao X, Zou Y, et al. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 87:100–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.069

37. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:E1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729

38. Tan BYQ, Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Jing M, Goh Y, Yeo LLL, et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in Singapore. Ann Intern Med . (2020) 173:317–20. doi: 10.7326/M20-1083

39. Liu Y, Ho RC, Mak A. Interleukin (IL)-6, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and soluble interleukin-2 receptors (sIL-2R) are elevated in patients with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Affect Disord. (2012) 139:230–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.003

40. Viljoen M, Panzer A. Proinflammatory cytokines: a common denominator in depression and somatic symptoms? Can J Psychiatry. (2005) 50:128. doi: 10.1177/070674370505000216

41. Li HY, Cao H, Leung DYP, Mak YW. The psychological impacts of a COVID-19 outbreak on college students in China: a longitudinal study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:3933. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113933

42. Krishnakumar B, Rana S. COVID 19 in INDIA: strategies to combat from combination threat of life and livelihood. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. (2020) 53:389–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.024

43. Huang Y, Wu Q, Wang P, Xu Y, Wang L, Zhao Y, et al. Measures undertaken in China to avoid COVID-19 infection: internet-based, cross-sectional survey study. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e18718. doi: 10.2196/18718

44. Salo J. China Orders 1,400 Military Doctors, Nurses to Treat Coronavirus. (2020). Available online at: https://nypost.com/2020/02/02/china-orders-14000-military-doctors-nurses-to-treat-coronavirus/ (accessed March 22, 2020).

45. Burki T. China's successful control of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. (2020) 20:1240–1. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30800-8

46. Esguerra DJ. Philippine Arena to Start Accepting COVID-19 Patients Next Week . (2020). Available online at: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1255623/philippine-arena-to-start-accepting-covid-19-patients-next-week (accessed November 18, 2020).

47. Bastani P, Bahrami MA. COVID-19 related misinformation on social media: a qualitative study from Iran. J Med Internet Res. (2020). doi: 10.2196/preprints.18932. [Epub ahead of print].

48. Catherine W. It's Unfair to Blame China for Coronavirus Pandemic, Lancet Editor Tells State Media. (2020). Available online at: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/science/article/3082606/its-unfair-blame-china-coronavirus-pandemic-lancet-editor-tells (accessed May 8, 2020).

Keywords: anxiety, China, COVID-19, depression, middle-income, knowledge, precaution, Philippines

Citation: Tee M, Wang C, Tee C, Pan R, Reyes PW, Wan X, Anlacan J, Tan Y, Xu L, Harijanto C, Kuruchittham V, Ho C and Ho R (2021) Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical and Mental Health in Lower and Upper Middle-Income Asian Countries: A Comparison Between the Philippines and China. Front. Psychiatry 11:568929. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.568929

Received: 02 June 2020; Accepted: 22 December 2020; Published: 09 February 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Tee, Wang, Tee, Pan, Reyes, Wan, Anlacan, Tan, Xu, Harijanto, Kuruchittham, Ho and Ho. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cuiyan Wang, wcy@chnu.edu.cn

† These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Philippines

- Most Cited Papers

- Most Downloaded Papers

- Newest Papers

- Last »

- Southeast Asian Studies Follow Following

- Philippine Studies Follow Following

- Southeast Asia Follow Following

- Philippine History Follow Following

- Colonial Philippines Follow Following

- Southeast Asian history Follow Following

- Colonialism Follow Following

- Global History Follow Following

- Asian Studies Follow Following

- The Moros Of Mindanao In Southern Philippines Follow Following

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- Academia.edu Journals

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Research Papers

Big Data for a Climate Disaster-Resilient Country, Philippines Ebinezer R. Florano

A Veto Players Analysis of Subnational Territorial Reform in Indonesia Michael A. Tumanut

The Politics of Municipal Merger in the Philippines Michael A. Tumanut

2018 AGPA Conference papers

Management of Social Media for Disaster Risk Reduction and Mitigation in Philippine Local Government Units Erwin A. Alamapy, Maricris Delos Santos, and Xavier Venn Asuncion

An Assessment of the Impact of GAD Programs on the Retention Intentions of Female Uniformed Personnel of the Philippine Navy Michelle C. Castillo

Contextualizing Inclusive Business: Amelioration of ASEAN Economic Community Arman V. Cruz

The impact of mobile financial services in low- and lower middle-income countries Erwin A. Alampay, Goodiel Charles Moshi, Ishita Ghosh, Mina Lyn C. Peralta and Juliana Harshanti

How Cities Are Promoting Clean Energy and Dealing with Problems Along the Way Rizalino B. Cruz Impact Assessment Methods: Toward Institutional Impact Assessment Romeo B. Ocampo

Philippine Technocracy and Politico-administrative Realities During the Martial Law Period (1972–1986): Decentralization, Local governance and Autonomy Concerns of Prescient Technocrats Alex B. Brillantes, Jr. and Abigail Modino

Policy Reforms to Improve the Quality of Public Services in the Philippines Maria Fe Villamejor-Mendoza

Compliance with, and Effective Implementation of Multilateral Environmental Agreements: Looking Back at the Transboundary Haze Pollution Problem in the ASEAN Region Ebinezer R. Florano, Ph.D.

ASEAN, Food Security, and Land Rights: Enlarging a Democratic Space for Public Services in the ASEAN Maria Faina L. Diola, DPA

Public Finance in the ASEAN: Trend and Patterns Jocelyn C. Cuaresma, DPA

Private Sector Engagement in Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation: Implications in Regional Governance Maria Fe Villamejor-Mendoza , Ph.D.

Philippine Response to Curb Human Trafficking of Migrant Workers Lizan Perante-Calina

Local Heritage Networking for ASEAN Connectivity Salvacion Manuel-Arlante

Financing Universal Healthcare and the ASEAN: Focus on the Philippine Sin Tax Law Abigail A. Modino

Decentralized Local Governance in Asian Region:Good Practices of Mandaluyong City, Philippines Rose Gay E. Gonzales- Castaneda

Disaster-Resilient Community Index: Measuring the Resiliency of Barangays in Tacloban, Iligan, Dagupan and Marikina Ebinezer R. Florano , Ph.D.

Towards Attaining the Vision “Pasig Green City”: Thinking Strategically, Acting Democratically Ebinezer R. Florano , Ph.D.

Community Governance for Disaster Recovery and Resilience: Four Case Studies in the Philippines Ebinezer R. Florano , Ph.D.

Mainstreaming Integrated Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction in Local development Plans in the Philippines Ebinezer R. Florano , Ph.D.

Building Back a Better Nation: Disaster Rehabilitation and Recovery in the Philippines Ebinezer R. Florano , Ph.D. and Joe-Mar S. Perez

The New Public Management Then and Now: Lessons from the Transition in Central and Eastern Europe Wolfgang Drechsler and Tiina Randma-Liiv

Optimizing ICT Budgets through eGovernment Projects Harmonization Erwin A. Alampay

ICT Sector Performance Review for Philippines Erwin A. Alampay

The Challenges to the Futures of Public Administration Education Maria Fe Villamejor-Mendoza

Enhancing Trust and Performance in the Philippine Public Enterprises: A Revisit of Recent Reforms and Transformations Maria Fe Villamejor-Mendoza

The Legal Framework for the Philippine Third Sector: Progressive or Regressive? Ma. Oliva Z. Domingo

Roles of Community and Communal Law in Disaster Management in the Philippines: The Case of Dagupan City Ebinezer R. Florano

Revisiting Meritocracy in Asian Settings: Dimensions of colonial Influences and Indigenous Traditions Danilo R. Reyes

The openness of the University of the Philippines Open University: Issues and Prospects Maria Fe Villamejor-Mendoza

Equity and Fairness in Public-Private Partnerships: The Case of Airport Infrastructure Development in the Philippines Maria Fe Villamejor- Mendoza

Restoring Trust and Building Integrity in Government: Issues and Concerns in the Philippines and Areas for Reform Alex B. Brillantes, Jr. and Maricel T. Fernandez

Competition in Electricity Markets: The Case of the Philippines Maria Fe Villamejor-Mendoza

Economic Reforms for Philippine Competitiveness, UP Open University Maria Fe Villamejor-Mendoza and G.H. Ambat (Eds)

Open Access to Educational Resources: The Wave of the Future? Maria Fe Villamejor-Mendoza

Climate Change Governance in the Philippines and Means of Implementation diagram Ebinezer R. Florano

Mobile 2.0: M-money for the BoP in the Philippines Erwin A. Alampay and Gemma Bala

When Social Networking Websites Meet Mobile Commerce Erwin A. Alampay

Monitoring Employee Use of the Internet in Philippine Organizations Erwin A. Alampay

Living the Information Society Erwin A. Alampay

Analysing Socio-Demographic Differences in the Access & Use of ICTs in the Philippines Using the Capability Approach, Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries Erwin A. Alampay

Measuring Capabilities in the Information Society Erwin A. Alampay

Modes of Learning and Performance Among U.P. Open University Graduates, Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries Victoria A. Bautista and Ma. Anna T. Quimbo

Copyright © 2024 | NCPAG

Participatory Educational Research

Add to my library.

Carrie Danae Bravo Feliz Danielle Dimalanta Kate Ashley Jusay Martina Ysabel Vitug Almighty Tabuena

- Abinuman, A. (2017). What's wrong with Filipino art and why is it under-appreciated? Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Candy. Retrieved from https://www.candymag.com/lifestyle/what-s-wrong-with-filipino-art-and-why-is-it-under-appreciated-a1580-20170722

- Ahmed, T. S. A. (2017). Assessment of students’ awareness of the national heritage (Case study: The preparatory year students at the University of Hail, Saudi Arabia). Cogent Social Sciences, 3(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2017.1306202

- Baraceros, E. L. (2016). Practical research 2. Philippines: Rex Book Store, Inc.

- Chiakiamco, C. (2010). The struggle for Philippine art - then and now. Philippines: Philstar Global Corp. Retrieved from https://www.philstar.com/lifestyle/arts-and-culture/2010/05/17/575439/struggle-philippine-art-then-and-now

- Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

- Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed). USA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- David, E .J .R. (2013). Brown skin, white minds: Filipino-American postcolonial psychology. Charlotte, North Carolina, United States: Information Age Publishing.

- Desirazu, N. (2019). The importance of art appreciation. Bangalore: EducationWorld. Retrieved from https://www.educationworld.in/the-importance-of-art-appreciation/

- Eliasson, O. (2016). Why art has the power to change the world. Switzerland: World Economic Forum. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/why-art-has-the-power-to-change-the-world/

- Ishiguro, C., Yokosawa, K., & Okada, T. (2016). Eye movements during art appreciation by students taking a photo creation course. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(1074). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01074

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of Emotion. American Psychologist, 46(8), 819-834.

- Leder, H., Gerger, G., Dressler, S., & Schabmann, A. (2012). How art is appreciated. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 6(1), 2-10. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026396

- Matamoros, S. P. & Sumi, A. (2017). Spanish artistic appreciation methodology in Japan: Learning own culture through art. Going to art museum with kindergarten children. Memoirs of the Faculty of Human Development University of Toyama, 12(1), 21-40.

- Mateo, F. V. (2016). Challenging Filipino colonial mentality with Philippine art. (Unpublished master’s thesis). The University of San Francisco. https://repository.usfca.edu/thes/196

- Mercado, A. (2018). Is the Philippines still interested in contemporary art? Philippines: Philstar Global Corp. Retrieved from https://www.philstar.com/lifestyle/arts-and-culture/2018/12/03/1873577/philippines-still-interested-contemporary-art

- National Commission for Culture and the Arts (2016). Arts awake: Measuring the state of Philippine culture. Cebu City, Philippines: SunStar Publishing Inc. Retrieved from https://www.sunstar.com.ph/article/68334/Lifestyle/Arts-awake-Measuring-the-state-of-Philippine-culture

- Nova Southeastern University (2020). Mixed methods. USA: Abraham S. Fischler College of Education and School of Criminal Justice, Nova Southeastern University.

- Oclos, A. (2018). Archie Oclos: Social awareness through street art and the beauty and chaos of Philippine life. Native Province. Retrieved from https://www.nativeprovince.com/blogs/news/archie-oclos

- Papouli, E. (2017). The role of arts in raising ethical awareness and knowledge of the European refugee crisis among social work students. An example from the classroom. Social Work Education, 36(7), 775-793. http://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2017.1353074

- Pelowski. M., Markey, P. S., Lauring, J.O., Leder, H. (2016). Visualizing the impact of art: An update and comparison of current psychological models of art experience. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10(160). http://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00160

- Perez, M. J. V. & Templeza, M. R. (2012). Local studies centers: Transforming history, culture and heritage in the Philippines. IFLA World Library and Information Congress. Retrieved from https://www.ifla.org/past-wlic/2012/180-perez-en.pdf

- Postma, S. (2018). Recovering beauty in art. Scott Postma. Retrieved from https://www.scottpostma.net/2018/04/25/recovering-beauty-in-art/

- Rudd, M. A. (2015). Awareness of Humanities, Arts and Social Science (HASS) research is related to patterns of citizens’ community and cultural engagement. Social Sciences, 4(2), 313-338. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4020313

- Scherer, K. R., Shorr, A. & Johnstone, T. (ed) (2001). Appraisal processes in emotion: theory, methods, research. Canary, NC: Oxford University Press

- Sova, R. B. (2015). Art appreciation as a learned competence: A museum-based qualitative study of adult art specialist and art non-specialist visitors. Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal, 5(4), 141-157.

- Tabuena, A. C. (2019). Effectiveness of classroom assessment techniques in improving performance of students in music and piano. Global Researchers Journal, 6(1), 68-78.

- Tabuena, A. C., Bartolome, J. E. M. B. & Taboy D. K. R. (2020). Preferred teaching practices among junior high school teachers and its impact towards readiness of grade seven students in the secondary school. International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development, 4(4), 588-596. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4105703

- Untivero, D. (2017). Protecting our Filipino heritage. Tatler Asia Limited. Retrieved from https://ph.asiatatler.com/life/Protecting-Our-Filipino-Heritage

- Vanner, C. & Kimani, M. (2017). The role of triangulation in sensitive art-based research with children. Qualitative Research Journal, 17(2), 77-88. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-12-2016-0073

- Watzlawick, P., Weakland, J., & Fisch, R. (1974). Change: Principles of problem formation and problem resolution. NY: Norton

- Zimmermann, K. A. (2017). What is culture? Live Science. Retrieved from https://www.livescience.com/21478-what-is-culture-definition-of-culture.html

Inclination State on the Philippine Culture and Arts Using the Appraisal Theory: Factors of Progress and Deterioration

This study aimed to examine the inclination state among selected Filipinos using the Appraisal Theory in evaluating the appreciation level as an advocacy perspective towards the Philippine culture and arts. This study employed a transformative mixed method research design, both quantitative and qualitative views were considered through a survey questionnaire, an interview, and an assessment process conducted at Espiritu Santo Parochial School of Manila, Inc. and the National Commission for Culture and the Arts, Philippines. They were selected through convenience-quota and purposive sampling based on the subjects’ basic knowledge and appreciation of Philippine culture and heritage. The data were analyzed using frequency distribution and content analysis. Hake factor analysis was also used to measure the appraisal level in terms of art awareness and appreciation. The results revealed that the respondents grasped a high appraisal of the Philippine culture and arts. This implied progress factors in terms of art as a form of communication, museums as the priority tool for preservation and promotion, and the country’s identity and cultural history as to reframe art appreciation. On the contrary, they adapted more to the culture and arts of other countries than to cultural roots due to factors that cause it to deteriorate such as foreign cultures and modern technologies adaptation, lack of knowledge and participation, and the primordialism of ethnocentrism. The researchers assessed that the theory exposed understanding emotions as it is evident that the respondents can reframe others with their beliefs and values towards Philippine culture and arts.

appraisal level , appraisal theory , deterioration , inclination state , Philippine arts , Philippine culture

| Primary Language | English |

|---|---|

| Subjects | Other Fields of Education, Special Education and Disabled Education |

| Journal Section | Research Articles |

| Authors | Carrie Danae Bravo This is me This is me This is me This is me |

| Publication Date | January 1, 2022 |

| Acceptance Date | July 4, 2021 |

| Published in Issue |

| APA | Bravo, C. D., Dimalanta, F. D., Jusay, K. A., Vitug, M. Y., et al. (2022). Inclination State on the Philippine Culture and Arts Using the Appraisal Theory: Factors of Progress and Deterioration. Participatory Educational Research, 9(1), 388-403. https://doi.org/10.17275/per.22.21.9.1 |

Artificial Intelligence and the Integration of the Industrial Revolution 6.0 in Ethnomusicology: Demands, Interventions and Implications

Musicologist, https://doi.org/10.33906/musicologist.1286472, usefulness and challenges of clustered self-directed learning modules in entrepreneurship for senior high school distance learning, turkish online journal of distance education, https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.1143460.

- Article Files

- Journal Home Page

- Volume: 8 Issue: 3

- Volume: 8 Issue: 4

- Volume: 9 Issue: 1

- Volume: 9 Issue: 2

- Volume: 9 Issue: 3

Philippine E-Journals

Home ⇛ psychology and education: a multidisciplinary journal ⇛ vol. 6 no. 8 (2023), a quantitative study: impact of public teacher qualifications and teaching experience on students' academic performance and satisfaction.

Nikki Numeron | Myra Arado | Flordelyn Perez

Discipline: Education

Student feedback is a crucial indicator of how well teachers and the educational system are performing. Maintaining high standards of quality and assessing teacher effectiveness as well as student academic performance depend on students' satisfaction. The goal of the study was to investigate the impact of public school teacher qualifications and teaching experience on students’ academic performance and satisfaction. The study was conducted at the selected elementary schools in Agusan del Sur, Philippines. It has been randomly picked based on the criteria and guidelines portrayed by the researchers. The study has utilized a quantitative research approach with a descriptive research design. The study has used a descriptive survey questionnaire. The participants in the study were 50 randomly selected public elementary teachers and another 40 randomly selected samples of students from the said schools. The reliability tests were just performed to measure the internal consistency and construct validity of the scales of the study. Furthermore, the study used a linear regression to greatly attain the main objectives of the study as well as a multiple moderation regression, known as the MMR test, to attest to the relationships between the given objectives. Based on the findings, the linear regression analysis was applied to investigate the relationship between teachers’ experience, qualifications, and the level of students’ satisfaction. It was stated on the table that the R2 value of public teacher experience was 0.512 and their qualifications were 0.611, whereas the students’ satisfaction score of 0.877 had significantly increased based on their perceived interest in the teaching methods of the teachers in the actual setting. Model 1 findings: effective knowledge sharing has been extensively researched and found to have significant effects on student satisfaction and academic performance (R2 = 0.678; p 0.000; beta coefficient = 0.694, respectively). Also, (Model 2: R2 = 0.522; p 0.000; beta coefficient = 0.759), which is significantly correlated to the level of student satisfaction Model 3: R2 = 0.711, p<0.000, and beta coefficient = 0.473, respectively, with a 95% confidence level based on the outcome. The findings show that teacher qualification predicts student satisfaction more accurately than teacher experience. The association between teachers' experience and qualifications and student satisfaction was somewhat mediated by teacher methods, skills, and knowledge-sharing efficiency.

References:

- Aguinis, H. (2004). Regression analysis for categorical moderators: Guilford Press. Aldridge, S., & Rowley, J. (1998). Measuring customer satisfaction in higher education. Quality Assurance in Education, 6(4), 197-204.

- Aslam, U., Rehman, M., Imram, M. I., & Muqadas, F. (2016). The Impact of Teacher Qualifications and Experience on Student Satisfaction: A Mediating and Moderating Research Model. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences 2016, Vol. 10 (3), 505- 524 Pak J Commer Soc Sci.

- Butron, P. V. V. (2021). Responsiveness, Emotions, and Tasks of Teachers in the New Normal of Education in the Philippines. Journal homepage: www. ijrpr. com ISSN, 2582, 7421.

- Chapman, D. W., Al-Barwani, T., Al Mawali, F., & Green, E. (2012). Ambivalent journey: Teacher career paths in Oman. International Review of Education, 58(3), 387- 403.

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approach: Sage publications.

- Douglas, J. A., Douglas, A., McClelland, R. J., & Davies, J. (2015). Understanding student satisfaction and dissatisfaction: an interpretive study in the UK higher education context. Studies in Higher Education, 40(2), 329-349.

- Johnson, S. M., Kraft, M. A., & Papay, J. P. (2012). How context matters in high-need schools: The effects of teachers’ working conditions on their professional satisfaction and their students’ achievement. Teachers College Record, 114(10), 1-39.

- Lenton, P. (2015). Determining student satisfaction: An economic analysis of the National Student Survey. Economics of Education Review, 47, 118-127.

- Mendoza, E. M., Cimagala, L. C. P., Villagonzalo, A. P., Guillarte, M. C., Saro, J. M. (2022). Coping Mechanisms and Teachers' Innovative Practices in Distance Learning: Challenges and Difficulties for the Modular Teaching and Learning Approach. Psychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary Journal.

- Michaelowa, K. (2002). Teacher job satisfaction, student achievement, and the cost of primary education in Francophone SubSaharan Africa: HWWA Discussion Paper.

- Sekaran, U. (2014). Research methods for business: A skill building approach. John Wiley & Sons.

- Sagales, J., Gonzaga, E., Gonzaga, D. & Miranda, M. (2021). Coping mechanisms of public teachers during the pandemic: an evaluative review. International Journal of Current Research, 12,(9), 13836-13839

- Saro, J., Cuasito, R., Doliguez, Z., Maglinte, F., Pableo, R., (2022). Teaching Competencies and Coping Mechanisms among the Selected Public Primary and Secondary Schools in Agusan del Sur Division: Teachers in the New Normal Education. Psychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 3(10), 969-974.

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2012). Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: Relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and emotional exhaustion. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(6), 1029-1038.

- Veldman, I., Van Tartwijk, J., Brekelmans, M., & Wubbels, T. (2013). Job satisfaction and teacher–student relationships across the teaching career: Four case studies. Teaching and Teacher Education, 32, 55-65.

Share Article:

ISSN 2822-4353 (Online)

- Cite this paper

- ">Indexing metadata

- Print version

Copyright © 2024 KITE Digital Educational Solutions | Exclusively distributed by CE-Logic Terms and Conditions -->

A Correlational Inquiry of COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in the Philippines

4 Pages Posted: 22 Jun 2020

Nelma Mae Loja

Davao del norte state college, rolando villamor jr, jayson macarine, mark van buladaco.

Date Written: June 11, 2020

The world is now in a pandemic crisis because of the new coronavirus, which causes COVID-19 disease. The Philippines is one of the countries that has been hit by the pandemic, and it is still continuing. There significant new cases and new deaths every day in the country. This paper inquires the relationship of COVID-19 number of cases and the number of deaths in the Philippines. As of May 07, 2020, there are 339 new cases, just for that day, and the Philippines already has 10,343 number of coronavirus cases. The data was acquired from the Department of Health, Philippines Data Drop Repository. The result shows that there is a strong relationship between the two variables with r=0.797. Moreover, there is a significant relationship between the number of cases and the number of deaths in the Philippines for the COVID-19 disease with a p-value of 0.000 (Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level 2-tailed).

Note: Funding: None to declare Declaration of Interest: None to declare

Keywords: Correlational Research, Pandemic, COVID-19, Deaths, Recoveries, Philippines

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

Panabo City Philippines

Mark Van Buladaco (Contact Author)

Davao del norte state college ( email ).

New Visayas Panabo City, Davao del Norte Philippines

Do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on SSRN?

Paper statistics, related ejournals, covid-19 ejournal.

Subscribe to this free journal for more curated articles on this topic

Human Health & Disease eJournal

Subscribe to this fee journal for more curated articles on this topic

Public Health eJournal

Infectious diseases ejournal.

250 Grade 12 Quantitative Research Topics for Senior High School Students in the Philippines

Greetings, dear senior high school students in the Philippines! If you’re on the hunt for that ideal quantitative research topic for your Grade 12 project, you’ve struck gold! You’re in for a treat because we’ve got your back. Within the pages of this blog, we’ve meticulously assembled an extensive catalog of 250 intriguing quantitative research themes for your exploration.

We completely grasp that the process of selecting the right topic might feel a tad overwhelming. To alleviate those concerns, we’ve crafted this resource to simplify your quest. We’re about to embark on a journey of discovery together, one that will empower you to make a well-informed choice for your research project. So, without further ado, let’s plunge headfirst into this wealth of research possibilities!

What is Quantitative Research?

Quantitative research is a type of research that deals with numbers and data. It involves collecting and analyzing numerical information to draw conclusions or make predictions. It’s all about using statistics and mathematical methods to answer research questions. Now, let’s explore some exciting quantitative research topics suitable for Grade 12 students in the Philippines.

Unlock educational insights at newedutopics.com . Explore topics, study tips, and more! Get started on your learning journey today.

- How Social Media Affects Academic Performance

- Factors Influencing Students’ Choice of College Courses

- The Relationship Between Study Habits and Grades

- The Effect of Parental Involvement on Students’ Achievements

- Bullying in High Schools: Prevalence and Effects

- How Does Nutrition Affect Student Concentration and Learning?

- Examining the Relationship Between Exercise and Academic Performance

- The Influence of Gender on Math and Science Performance

- Investigating the Factors Leading to School Dropouts

- The Effect of Peer Pressure on Decision-Making Among Teens

- Exploring the Connection Between Socioeconomic Status and Academic Achievement

- Assessing the Impact of Technology Use in Education

- The Correlation Between Sleep Patterns and Academic Performance

- Analyzing the Impact of Classroom Size on Student Engagement

- The Role of Extracurricular Activities in Character Development

- Investigating the Use of Alternative Learning Modalities During the Pandemic

- The Effectiveness of Online Learning Platforms

- The Influence of Parental Expectations on Career Choices

- The Relationship Between Music and Concentration While Studying

- Examining the Link Between Personality Traits and Academic Success

Now that we’ve given you a taste of the topics, let’s break them down into different categories:

Education and Academic Performance:

- The Impact of Teacher-Student Relationships on Learning

- Exploring the Benefits of Homework in Learning

- Analyzing the Effectiveness of Different Teaching Methods

- Investigating the Use of Technology in Teaching

- The Role of Educational Field Trips in Learning

- The Relationship Between Reading Habits and Academic Success

- Assessing the Impact of Standardized Testing on Students

- The Effect of School Uniforms on Student Behavior

- Analyzing the Benefits of Bilingual Education

- How Classroom Design Influences Student Engagement

Health and Wellness:

- Analyzing the Connection Between Fast Food Consumption and Health Outcomes

- Exploring How Physical Activity Impacts Mental Health

- Investigating the Prevalence of Stress Among Senior High School Students

- The Effect of Smoking on Academic Performance

- The Relationship Between Nutrition and Physical Fitness

- Analyzing the Impact of Vaccination Programs on Public Health

- Understanding the Importance of Sleep in Mental and Emotional Well-being

- Investigating the Use of Herbal Remedies in Health Management

- The Effect of Screen Time on Eye Health

- Examining the Connection Between Drug Abuse and Academic Performance

Social Issues:

- Exploring the Factors Leading to Teenage Pregnancy

- Analyzing the Impact of Social Media on Body Image

- Investigating the Causes of Youth Involvement in Juvenile Delinquency

- The Effect of Cyberbullying on Mental Health

- The Relationship Between Gender Equality and Education

- Assessing the Impact of Poverty on Student Achievement

- The Influence of Religion on Moral Values

- Analyzing the Role of Filipino Culture in Shaping Values

- The Effect of Political Instability on Education

- Investigating the Impact of Mental Health Awareness Campaigns

Technology and Innovation:

- The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Education

- Examining the Impact of E-Learning Platforms on Student Performance

- Exploring the Application of Virtual Reality in Education

- The Effect of Smartphone Use on Classroom Distractions

- The Relationship Between Coding Skills and Future Employment

- Assessing the Benefits of Gamification in Education

- The Influence of Online Gaming on Academic Performance

- Analyzing the Role of 3D Printing in Education

- Investigating the Use of Drones in Environmental Research

- Analyzing How Social Networking Sites Affect Socialization

Environmental Concerns:

- Assessing the Effects of Climate Change Awareness on Conservation Efforts

- Investigating the Impact of Pollution on Local Ecosystems

- Exploring the Link Between Waste Management Practices and Environmental Sustainability

- Analyzing the Benefits of Renewable Energy Sources

- The Effect of Deforestation on Biodiversity

- Exploring Sustainable Agriculture Practices

- The Role of Ecotourism in Conservation

- Investigating the Impact of Plastic Waste on Marine Life

- Analyzing Water Quality in Local Rivers and Lakes

- Assessing the Importance of Coral Reef Conservation

Economic Issues:

- The Influence of Economic Status on Educational Opportunities

- Examining the Impact of Inflation on Student Expenses

- Investigating the Role of Microfinance in Poverty Alleviation

- Analyzing the Effects of Unemployment on Youth

- The Relationship Between Entrepreneurship Education and Business Success

- The Effect of Taxation on Small Businesses

- Assessing the Impact of Tourism on Local Economies

- The Role of Online Marketplaces in Small Business Growth

- Investigating the Benefits of Financial Literacy Programs

- Analyzing the Impact of Foreign Investments on the Philippine Economy

Cultural and Historical Topics:

- Exploring the Influence of Spanish Colonization on Filipino Culture

- Analyzing the Role of Filipino Heroes in Nation-Building

- Investigating the Impact of K-Pop on Filipino Youth Culture

- The Relationship Between Traditional and Modern Filipino Values

- Assessing the Importance of Philippine Indigenous Languages

- The Effect of Colonial Mentality on Identity

- The Role of Filipino Cuisine in Tourism

- Investigating the Influence of Filipino Art on National Identity

- Analyzing the Significance of Historical Landmarks

- Examining the Role of Traditional Filipino Clothing in Society

Government and Politics:

- The Influence of Social Media on Political Participation

- Investigating Voter Education and Awareness Campaigns

- Analyzing the Impact of Political Dynasties on Local Governance

- Assessing the Effectiveness of Disaster Response Programs

- The Relationship Between Corruption and Public Services

- The Role of Youth in Nation-Building

- Investigating the Impact of Martial Law on Philippine Society

- Analyzing the Role of Social Movements in Policy Change

- Assessing the Importance of Good Governance in National Development

- The Effect of Federalism on Local Autonomy

Science and Technology:

- Exploring Advances in Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering

- Analyzing the Impact of Space Exploration on Scientific Discovery

- Investigating the Use of Nanotechnology in Medicine

- The Relationship Between STEM Education and Innovation

- The Effect of Pollution on Biodiversity

- Assessing the Benefits of Solar Energy in the Philippines

- The Role of Robotics in Industry Automation

- Investigating the Potential of Hydrogen Fuel Cells

- Analyzing the Use of 5G Technology in Communication

- The Impact of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare

Healthcare and Medicine:

- The Influence of Traditional Medicine Practices on Health

- Investigating the Impact of Mental Health Stigma

- Analyzing the Use of Telemedicine in Remote Areas

- The Relationship Between Diet and Chronic Diseases

- Assessing the Effectiveness of Healthcare Access Programs

- The Role of Nurses in Public Health

- Investigating the Benefits of Medical Missions

- Analyzing the Impact of Healthcare Quality on Patient Outcomes

- Assessing the Importance of Health Education

- The Effect of Access to Clean Water on Public Health

Business and Finance:

- Exploring the Impact of E-Commerce on Local Businesses

- Analyzing the Role of Digital Payment Systems

- Investigating Consumer Behavior in Online Shopping

- The Relationship Between Customer Loyalty and Business Success