- Project Management

Home » Free Resources » »

What Is Problem Solving in Project Management? Here’s Everything You Need to Know

- Written by Contributing Writer

- Updated on August 26, 2024

In project management , problem-solving is a crucial and necessary skill. Whether you have failed to consider every possible factor impacting a project, a problem arises through no fault of your own, or conditions change that create issues, problems must be addressed promptly to keep projects on track.

In this article, we will define problem-solving and how it impacts projects, provide real-world examples of problem-solving, and give you a structured, step-by-step process to solve problems. We’ll also show you how earning a project management certification can help you gain practical experience in problem-solving methods.

What Is Problem-Solving?

Problem-solving is a process to identify roadblocks or defects that arise during a project. A structured system to define problems, identify root causes, brainstorm and test solutions, and monitor results can affect change to improve performance and overcome challenges.

Effective problem-solving enables teams to deal with uncertainties or gaps in planning to minimize the impact on outcomes.

The Importance of Problem-Solving in Project Management

During a project and operation, problems can arise at any time. You may find that your planning before launching a product, for example, did not consider all the factors that impact results. You may find that you were too optimistic about project timelines, performance, or workforce. Or, as many of us discovered over the past few years, supply chain disruption may make even the best project plans obsolete.

Regardless, your job is identifying, solving, and overcoming these problems. Project managers must be skilled in leading team members through a structured approach to resolving problems.

Proactive problem-solving requires careful consideration of all the variables in a project, including preparation to:

- Achieve project objectives

- Address obstacles before they arise

- Manage project risks and contingency plans

- Manage communication and collaboration

- Provide a framework for time and cost management

- Provide a pathway for continuous improvement

Also Read: 10 Tips on How to Increase Productivity in the Workplace

Problem-Solving Steps in Project Management

While the process you choose to solve problems may vary, here is a seven-step framework many project managers use. This problem-solving method combines primary and secondary problem-solving steps.

#1. Define the Problem

- Gather data and information from key stakeholders, team members, and project documentation. Include any relevant reporting or data analysis

- Itemized key details, such as a description of the problem, timelines, outcomes, and impact

- Frame the issue as a problem statement

A good example of a problem statement might be: An unexpected demand spike has exceeded our current production capacity. How can we still meet customer deadlines for delivery?

#2. Analyze Root Causes

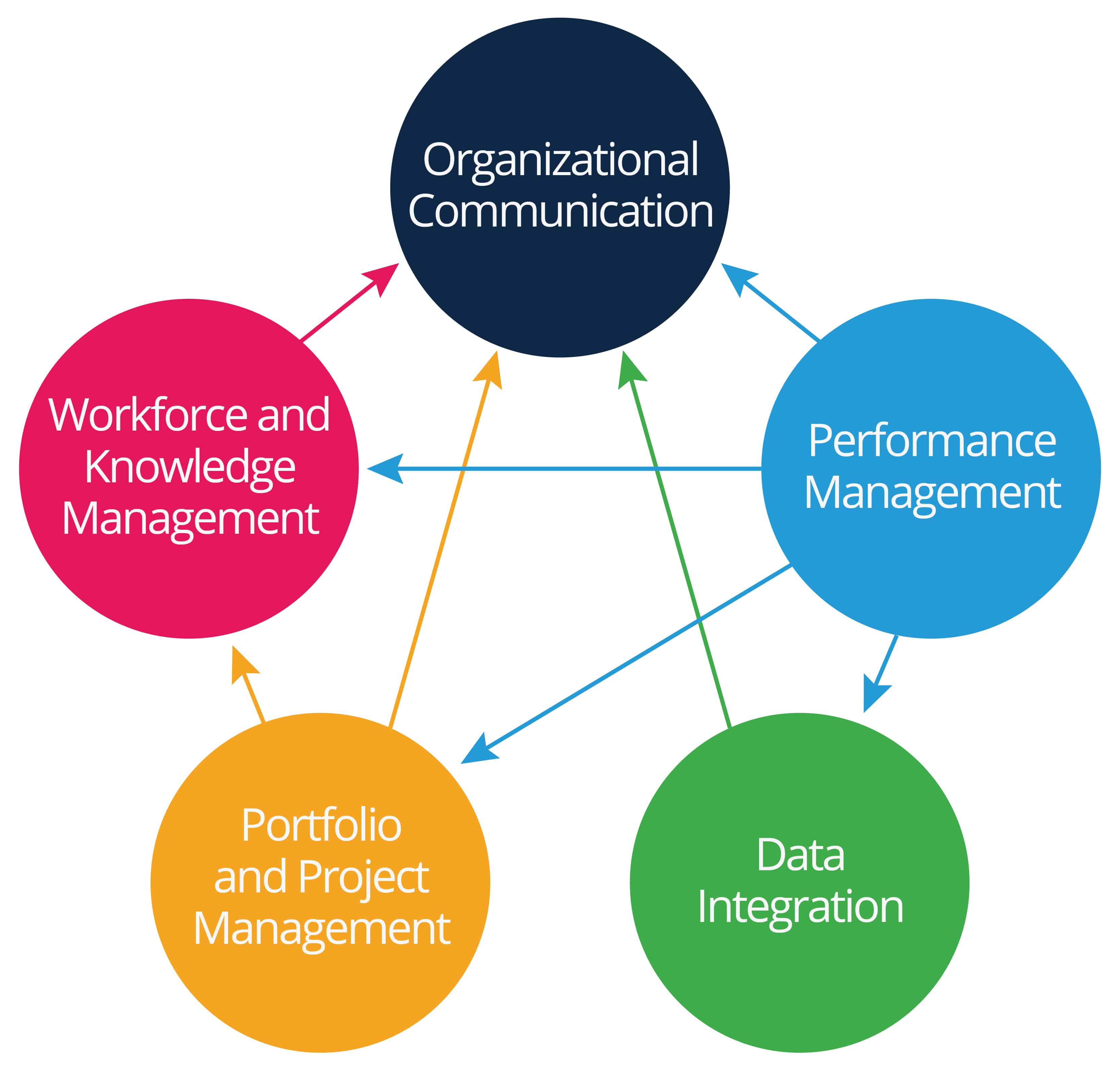

- Break down issues into smaller components to diagnose bottlenecks or problems

- Identify the organizational, mechanical, environmental, or operational factors that contribute

- Distinguish between one-time issues vs. systematic, ongoing areas that need improvement

When analyzing root causes, it’s common to find multiple factors contributing to a problem. As such, it is essential to prioritize issues that have the most significant impact on outcomes.

#3. Brainstorm Potential Solutions

- Holding specific sessions focused on brainstorming ideas to resolve root causes

- Build on ideas or suggest combinations or iterations

- Categorize solutions by types, such as process or input changes, adding additional resources, outsourcing, etc.)

In brainstorming, you should refrain from immediately analyzing suggestions to keep ideas coming.

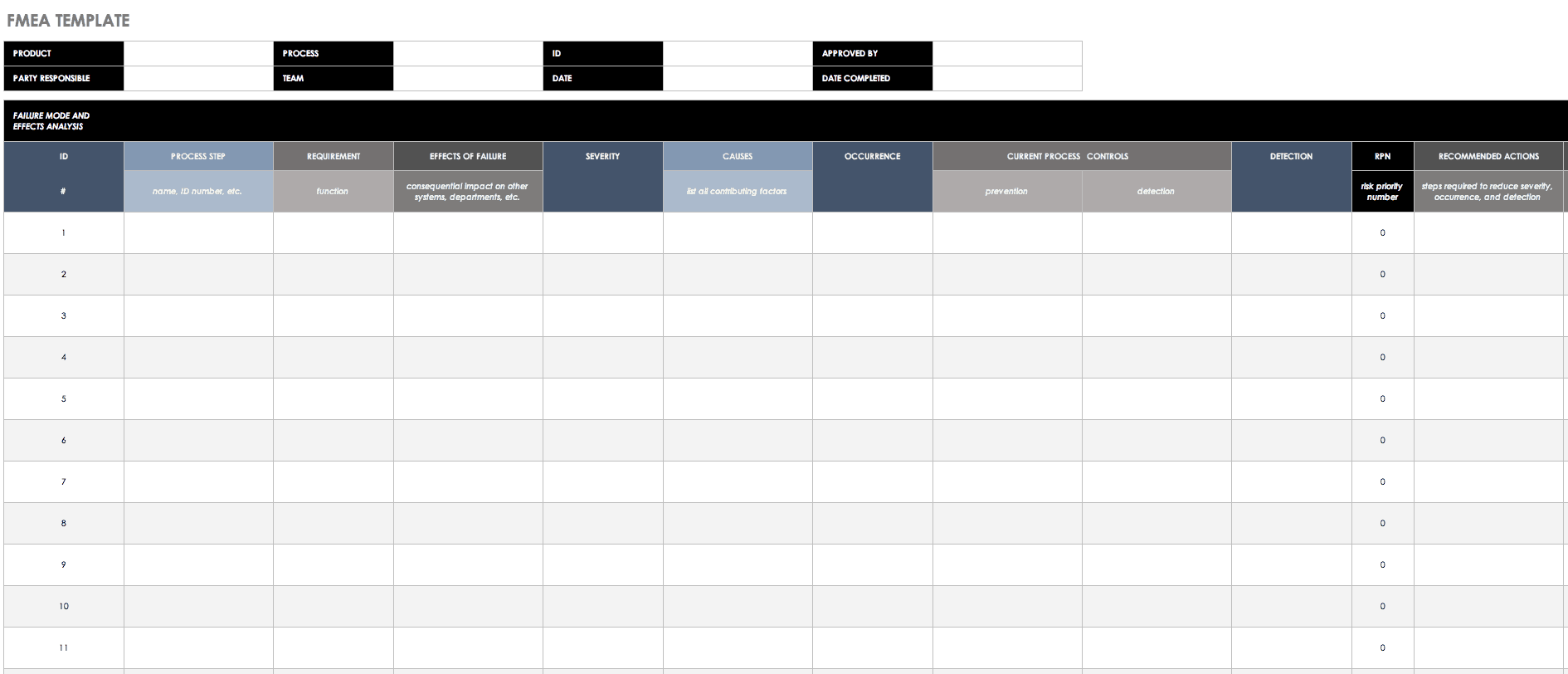

#4. Evaluate Potential Solutions

- Reframe the problem and concern for team members, providing a framework for evaluation such as cost, timing, and feasibility

- With ideas in hand, it is time to evaluate potential solutions. Project managers often employ strategies such as weighted scoring models to rank ideas.

- Consider the pros and cons in relation to project objectives

As you narrow the list, getting additional insight from subject matter experts to evaluate real-world viability is helpful. For example, if you are proposing a process change in operating a machine, get feedback from skilled operators before implementing changes.

#5. Decide on a Plan of Action

- Make a decision on which course of action you want to pursue and make sure the solution aligns with your organizational goals

- Create an action plan to implement the changes, including key milestones

- Assign project ownership, deadlines, resources, and budgets

Defining what outcomes you need to achieve to declare success is also essential. Are you looking for incremental change or significant improvements, and what timeline are you establishing for measurement?

#6. Implement the Action Plan

- Communicate the plan with key stakeholders

- Provide any training associated with the changes

- Allocate resources necessary for implementation

As part of the action plan, you will also want to detail the measures and monitoring you will put in place to assess process outcomes.

#7. Monitor and Track Results

- Track solution performance against the action plan and key milestones

- Solicit feedback from the project team on problem-solving effectiveness

- Ensure the solution resolves the root cause, creating the desired results without negatively impacting other areas of the operation

You should refine results or start the process over again to increase performance. For example, you may address the root cause but find a need for secondary problem-solving in project management, focusing on other factors.

These problem-solving steps are used repeatedly in lean management and Six Sigma strategies for continuous improvement.

Also Read: 5 Project Management Steps You Need to Know

How Can Project Management Tools Help You Solve Problems?

Project management software can guide teams through problem-solving, acting as a central repository to provide visibility into the stages of a project.

The best project management software will include the following:

- Issue tracking to capture problems as they arise

- Chat and real-time collaboration for discussion and brainstorming

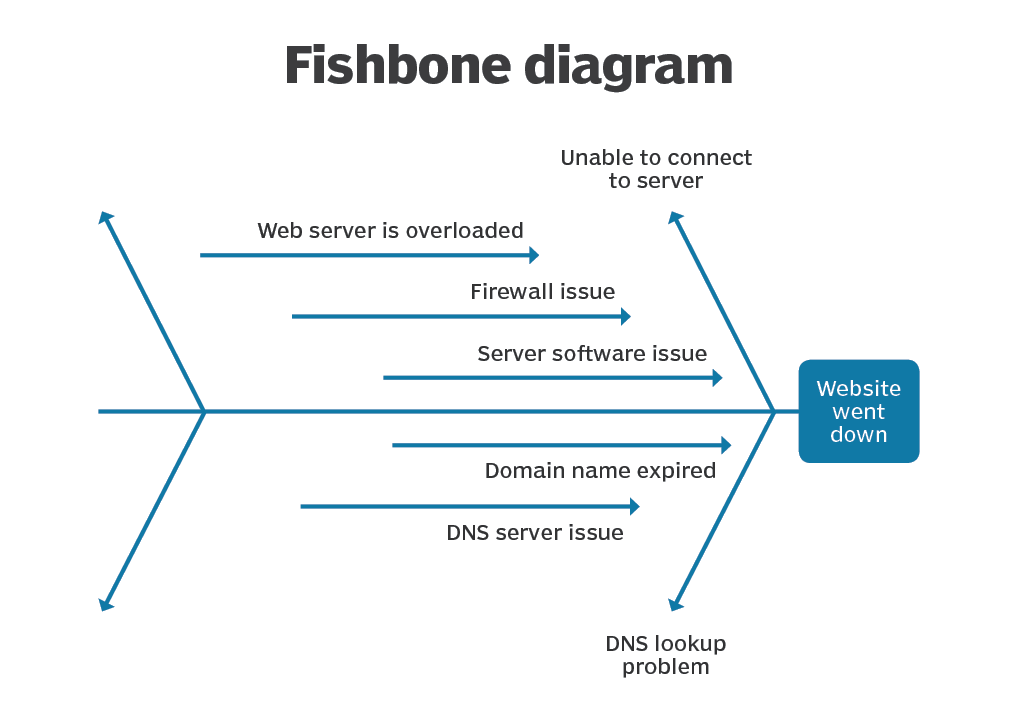

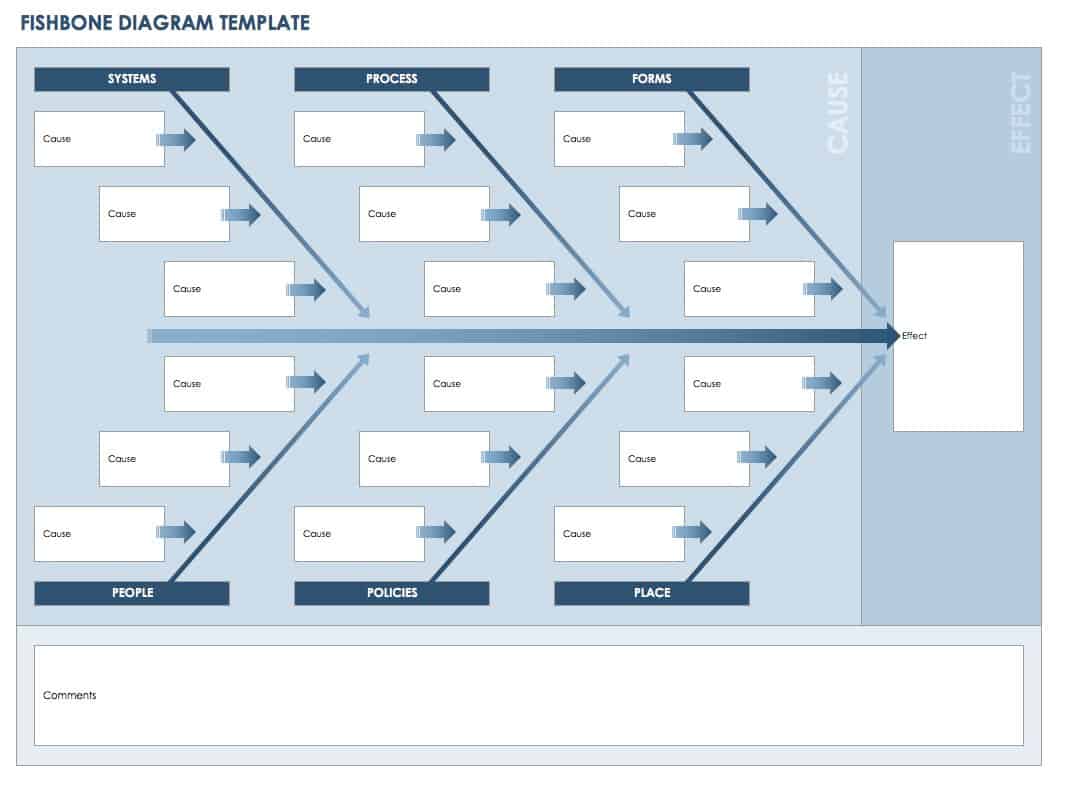

- Templates for analysis, such as fishbone diagrams

- Action plans, assigning tasks, ownership, and accountability

- Dashboards for updates to monitor solutions

- Reporting on open issues, mitigation, and resolution

Examples of Problem-Solving

Here are some examples of the problem-solving process demonstrating how team members can work through the process to achieve results.

Sign-ups for a New Software Solution Were Well Below First-Month Targets

After analyzing the data, a project team identifies the root cause as inefficient onboarding and account configurations. They then brainstorm solutions. Ideas include re-architecting the software, simplifying onboarding steps, improving the initial training and onboarding process, or applying additional resources to guide customers through the configuration process.

After weighing alternatives, the company invests in streamlining onboarding and developing software to automate configuration.

A Project Was at Risk of Missing a Hard Deadline Due to Supplier Delays

In this case, you already know the root cause: Your supplier cannot deliver the necessary components to complete the project on time. Brainstorming solutions include finding alternative sources for components, considering project redesigns to use different (available) components, negotiating price reductions with customers due to late delivery, or adjusting the scope to complete projects without this component.

After evaluating potential solutions, the project manager might negotiate rush delivery with the original vendor. While this might be more expensive, it enables the business to meet customer deadlines. At the same time, project schedules might be adjusted to account for later-than-expected part delivery.

A Construction Project Is Falling Behind Due to Inclement Weather

Despite months of planning, a major construction project has fallen behind schedule due to bad weather, preventing concrete and masonry work. The problem-solving team brainstorms the problem and evaluates solutions, such as constructing temporary protection from the elements, heating concrete to accelerate curing, and bringing on additional crews once the weather clears.

The project team might decide to focus on tasks not impacted by weather earlier in the process than expected to postpone exterior work until the weather clears.

Also Read: Understanding KPIs in Project Management

Improve Your Problem-Solving and Project Management Skills

This project management course delivered by Simpliearn, in collaboration wiht the University of Massachusetts, can boost your career journey as a project manager. This 24-week online bootcamp aligns with Project Management Institute (PMI) practices, the Project Management Professional (PMP®) certification, and IASSC-Lean Six Sigma.

This program teaches skills such as:

- Agile management

- Customer experience design

- Design thinking

- Digital transformation

- Lean Six Sigma Green Belt

You might also like to read:

5 Essential Project Management Steps You Need to Know

Project Management Frameworks and Methodologies Explained

13 Key Project Management Principles and How to Use Them

Project Management Phases: A Full Breakdown

How To Develop a Great Project Management Plan in 2023

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Recommended Articles

Career Prep: Tips for Gaining a Project Manager Certification

Discover how a project manager certification can boost your career. Learn about the benefits, types, and how to choose the right certification for your professional growth.

30+ Behavioral Interview Questions and How to Answer Them

Learn to craft answers that highlight your skills and experience. Prepare for your job switch with these common behavioral interview questions and answers.

What is Scope Creep in Project Management, and How to Avoid It?

What is scope creep? Understand this issue and how it can threaten your project’s success. Explore common causes, effects, and practical tips to manage and prevent it in project management.

6 Top Open-Source Project Management Tools for 2025

Manage your projects efficiently with the best open-source project management software tools of 2024. Our guide covers the top 6 free, customizable project management tools.

Top 8 Project Manager Interview Questions and Answers for 2024-25

Before you arrive for your scheduled interview for a new project manager position, it makes sense to do whatever you can to prepare for the

What are Project Management Frameworks and Methodologies?

At the heart of every successful project is one or more project management framework. In this article, we dive deep into these powerful tools and how you can harness them.

Project Management Bootcamp

Learning Format

Online Bootcamp

Program benefits.

- 25 in-demand tools covered

- Aligned with PMI-PMP® and IASSC-Lean Six Sigma

- Masterclasses from top faculty of UMass Amherst

- UMass Amherst Alumni Association membership

- Become a Project Manager

- Certification

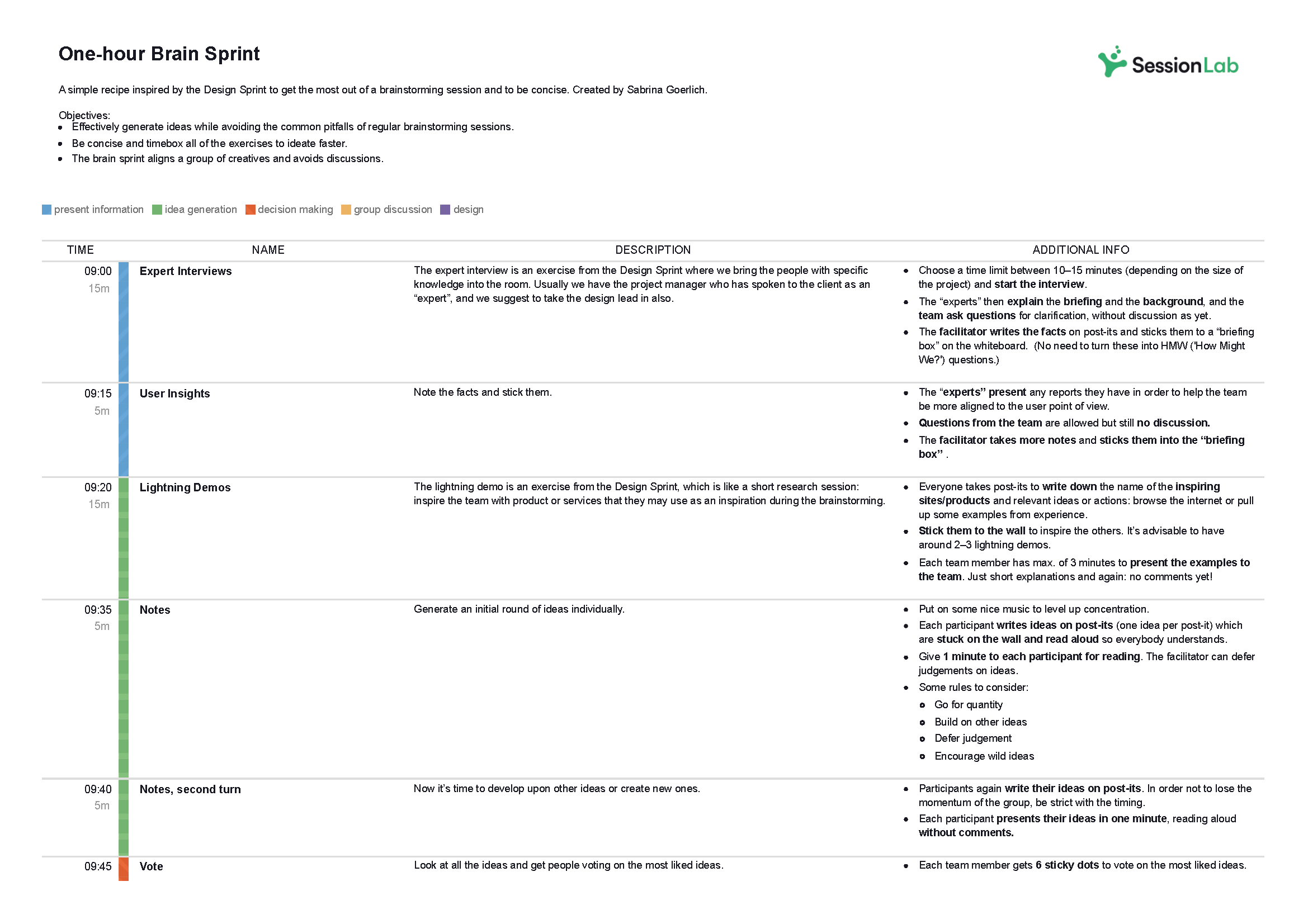

Problem Solving Techniques for Project Managers

Learn which problem solving techniques and strategies can help you effectively handle the challenges you face in your projects.

Problem Solving Techniques: A 5-Step Approach

Some problems are small and can be resolved quickly. Other problems are large and may require significant time and effort to solve. These larger problems are often tackled by turning them into formal projects.

"A project is a problem scheduled for solution."

- Joseph M. Juran

Problem Solving is one of the Tools & Techniques used for Managing Quality and Controlling Resources.

Modules 8 and 9 of the PM PrepCast cover Project Quality Management and Project Resource Management.

Consider this study program if you're preparing to take your CAPM or PMP Certification exam.

Disclosure: I may receive a commission if you purchase the PM PrepCast with this link.

Whether the problem you are focusing on is small or large, using a systematic approach for solving it will help you be a more effective project manager.

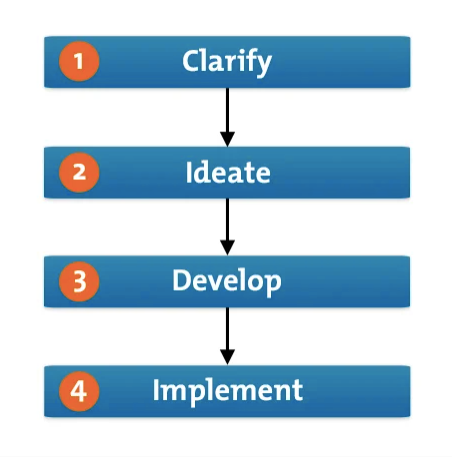

This approach defines five problem solving steps you can use for most problems...

Define the Problem

Determine the causes, generate ideas, select the best solution, take action.

The most important of the problem solving steps is to define the problem correctly. The way you define the problem will determine how you attempt to solve it.

For example, if you receive a complaint about one of your project team members from a client, the solutions you come up with will be different based on the way you define the problem.

If you define the problem as poor performance by the team member you will develop different solutions than if you define the problem as poor expectation setting with the client.

Once you have defined the problem, you are ready to dig deeper and start to determine what is causing it. You can use a fishbone diagram to help you perform a cause and effect analysis.

If you consider the problem as a gap between where you are now and where you want to be, the causes of the problem are the obstacles that are preventing you from closing that gap immediately.

This level of analysis is important to make sure your solutions address the actual causes of the problem instead of the symptoms of the problem. If your solution fixes a symptom instead of an actual cause, the problem is likely to reoccur since it was never truly solved.

Once the hard work of defining the problem and determining its causes has been completed, it's time to get creative and develop possible solutions to the problem.

Two great problem solving methods you can use for coming up with solutions are brainstorming and mind mapping .

After you come up with several ideas that can solve the problem, one problem solving technique you can use to decide which one is the best solution to your problem is a simple trade-off analysis .

To perform the trade-off analysis, define the critical criteria for the problem that you can use to evaluate how each solution compares to each other. The evaluation can be done using a simple matrix. The highest ranking solution will be your best solution for this problem.

Pass your PMP Exam!

The PM Exam Simulator is an online exam simulator.

Realistic exam sample questions so you can pass your CAPM or PMP Certification exam.

Disclosure: I may receive a commission if you purchase the PM Exam Simulator with this link.

Once you've determined which solution you will implement, it's time to take action. If the solution involves several actions or requires action from others, it is a good idea to create an action plan and treat it as a mini-project.

Using this simple five-step approach can increase the effectiveness of your problem solving skills .

For more problem solving strategies and techniques, subscribe to my newsletter below.

Related Articles About Problem Solving Techniques

Fishbone Diagram: Cause and Effect Analysis Using Ishikawa Diagrams

A fishbone diagram can help you perform a cause and effect analysis for a problem. Step-by-step instructions on how to create this type of diagram. Also known as Ishikara or Cause and Effect diagrams.

Do You Want More Project Management Tips?

Subscribe to Project Success Tips , my FREE Project Management Newsletter where I share tips and techniques that you can use to get your Project Management Career off to a great start .

As a BONUS for signing up, you'll receive access to my Subscribers Only Download Page ! This is where you can download my " Become A Project Manager Checklist " and other project management templates.

Don't wait...

- Become a PM

- Problem Solving Techniques

New! Comments

Home Privacy Policy About Contact

Copyright © 2010-2021 | ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Project-Management-Skills.com

40 problem-solving techniques and processes

All teams and organizations encounter challenges. Approaching those challenges without a structured problem solving process can end up making things worse.

Proven problem solving techniques such as those outlined below can guide your group through a process of identifying problems and challenges , ideating on possible solutions , and then evaluating and implementing the most suitable .

In this post, you'll find problem-solving tools you can use to develop effective solutions. You'll also find some tips for facilitating the problem solving process and solving complex problems.

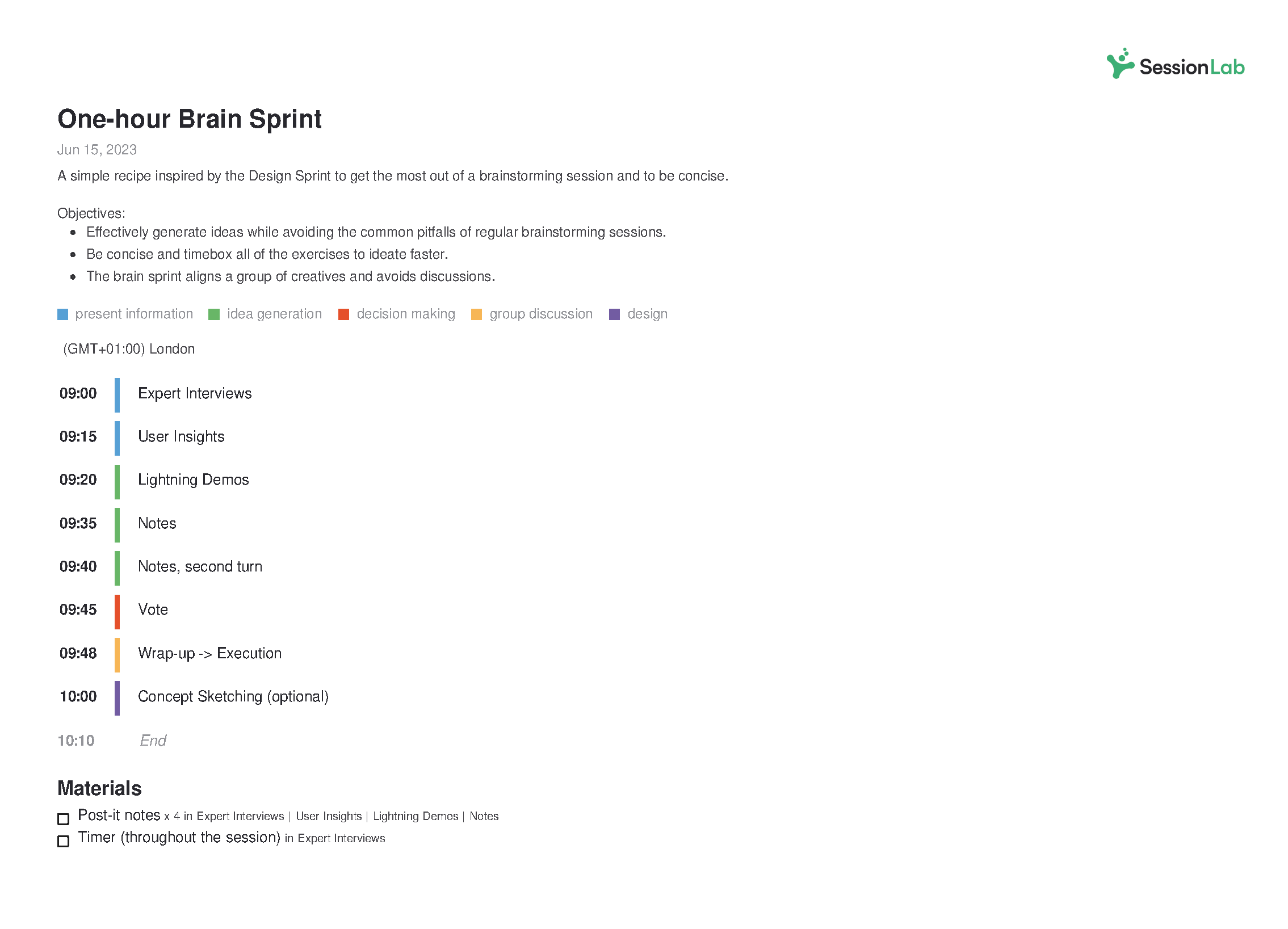

Design your next session with SessionLab

Join the 150,000+ facilitators using SessionLab.

Recommended Articles

A step-by-step guide to planning a workshop, 54 great online tools for workshops and meetings, how to create an unforgettable training session in 8 simple steps.

- 18 Free Facilitation Resources We Think You’ll Love

What is problem solving?

Problem solving is a process of finding and implementing a solution to a challenge or obstacle. In most contexts, this means going through a problem solving process that begins with identifying the issue, exploring its root causes, ideating and refining possible solutions before implementing and measuring the impact of that solution.

For simple or small problems, it can be tempting to skip straight to implementing what you believe is the right solution. The danger with this approach is that without exploring the true causes of the issue, it might just occur again or your chosen solution may cause other issues.

Particularly in the world of work, good problem solving means using data to back up each step of the process, bringing in new perspectives and effectively measuring the impact of your solution.

Effective problem solving can help ensure that your team or organization is well positioned to overcome challenges, be resilient to change and create innovation. In my experience, problem solving is a combination of skillset, mindset and process, and it’s especially vital for leaders to cultivate this skill.

What is the seven step problem solving process?

A problem solving process is a step-by-step framework from going from discovering a problem all the way through to implementing a solution.

With practice, this framework can become intuitive, and innovative companies tend to have a consistent and ongoing ability to discover and tackle challenges when they come up.

You might see everything from a four step problem solving process through to seven steps. While all these processes cover roughly the same ground, I’ve found a seven step problem solving process is helpful for making all key steps legible.

We’ll outline that process here and then follow with techniques you can use to explore and work on that step of the problem solving process with a group.

The seven-step problem solving process is:

1. Problem identification

The first stage of any problem solving process is to identify the problem(s) you need to solve. This often looks like using group discussions and activities to help a group surface and effectively articulate the challenges they’re facing and wish to resolve.

Be sure to align with your team on the exact definition and nature of the problem you’re solving. An effective process is one where everyone is pulling in the same direction – ensure clarity and alignment now to help avoid misunderstandings later.

2. Problem analysis and refinement

The process of problem analysis means ensuring that the problem you are seeking to solve is the right problem . Choosing the right problem to solve means you are on the right path to creating the right solution.

At this stage, you may look deeper at the problem you identified to try and discover the root cause at the level of people or process. You may also spend some time sourcing data, consulting relevant parties and creating and refining a problem statement.

Problem refinement means adjusting scope or focus of the problem you will be aiming to solve based on what comes up during your analysis. As you analyze data sources, you might discover that the root cause means you need to adjust your problem statement. Alternatively, you might find that your original problem statement is too big to be meaningful approached within your current project.

Remember that the goal of any problem refinement is to help set the stage for effective solution development and deployment. Set the right focus and get buy-in from your team here and you’ll be well positioned to move forward with confidence.

3. Solution generation

Once your group has nailed down the particulars of the problem you wish to solve, you want to encourage a free flow of ideas connecting to solving that problem. This can take the form of problem solving games that encourage creative thinking or techniquess designed to produce working prototypes of possible solutions.

The key to ensuring the success of this stage of the problem solving process is to encourage quick, creative thinking and create an open space where all ideas are considered. The best solutions can often come from unlikely places and by using problem solving techniques that celebrate invention, you might come up with solution gold.

4. Solution development

No solution is perfect right out of the gate. It’s important to discuss and develop the solutions your group has come up with over the course of following the previous problem solving steps in order to arrive at the best possible solution. Problem solving games used in this stage involve lots of critical thinking, measuring potential effort and impact, and looking at possible solutions analytically.

During this stage, you will often ask your team to iterate and improve upon your front-running solutions and develop them further. Remember that problem solving strategies always benefit from a multitude of voices and opinions, and not to let ego get involved when it comes to choosing which solutions to develop and take further.

Finding the best solution is the goal of all problem solving workshops and here is the place to ensure that your solution is well thought out, sufficiently robust and fit for purpose.

5. Decision making and planning

Nearly there! Once you’ve got a set of possible, you’ll need to make a decision on which to implement. This can be a consensus-based group decision or it might be for a leader or major stakeholder to decide. You’ll find a set of effective decision making methods below.

Once your group has reached consensus and selected a solution, there are some additional actions that also need to be decided upon. You’ll want to work on allocating ownership of the project, figure out who will do what, how the success of the solution will be measured and decide the next course of action.

Set clear accountabilities, actions, timeframes, and follow-ups for your chosen solution. Make these decisions and set clear next-steps in the problem solving workshop so that everyone is aligned and you can move forward effectively as a group.

Ensuring that you plan for the roll-out of a solution is one of the most important problem solving steps. Without adequate planning or oversight, it can prove impossible to measure success or iterate further if the problem was not solved.

6. Solution implementation

This is what we were waiting for! All problem solving processes have the end goal of implementing an effective and impactful solution that your group has confidence in.

Project management and communication skills are key here – your solution may need to adjust when out in the wild or you might discover new challenges along the way. For some solutions, you might also implement a test with a small group and monitor results before rolling it out to an entire company.

You should have a clear owner for your solution who will oversee the plans you made together and help ensure they’re put into place. This person will often coordinate the implementation team and set-up processes to measure the efficacy of your solution too.

7. Solution evaluation

So you and your team developed a great solution to a problem and have a gut feeling it’s been solved. Work done, right? Wrong. All problem solving strategies benefit from evaluation, consideration, and feedback.

You might find that the solution does not work for everyone, might create new problems, or is potentially so successful that you will want to roll it out to larger teams or as part of other initiatives.

None of that is possible without taking the time to evaluate the success of the solution you developed in your problem solving model and adjust if necessary.

Remember that the problem solving process is often iterative and it can be common to not solve complex issues on the first try. Even when this is the case, you and your team will have generated learning that will be important for future problem solving workshops or in other parts of the organization.

It’s also worth underlining how important record keeping is throughout the problem solving process. If a solution didn’t work, you need to have the data and records to see why that was the case. If you go back to the drawing board, notes from the previous workshop can help save time.

What does an effective problem solving process look like?

Every effective problem solving process begins with an agenda . In our experience, a well-structured problem solving workshop is one of the best methods for successfully guiding a group from exploring a problem to implementing a solution.

The format of a workshop ensures that you can get buy-in from your group, encourage free-thinking and solution exploration before making a decision on what to implement following the session.

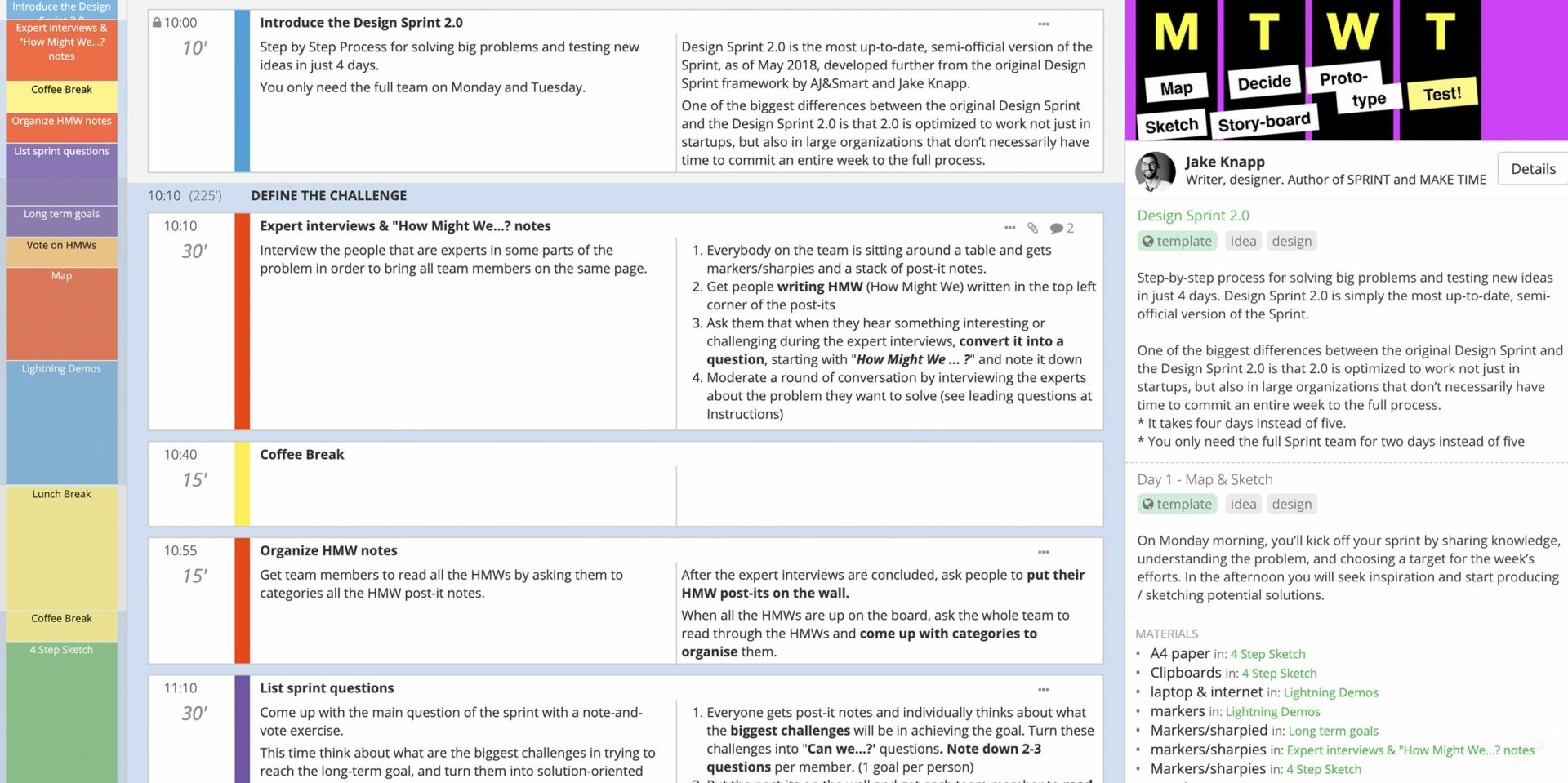

This Design Sprint 2.0 template is an effective problem solving process from top agency AJ&Smart. It’s a great format for the entire problem solving process, with four-days of workshops designed to surface issues, explore solutions and even test a solution.

Check it for an example of how you might structure and run a problem solving process and feel free to copy and adjust it your needs!

For a shorter process you can run in a single afternoon, this remote problem solving agenda will guide you effectively in just a couple of hours.

Whatever the length of your workshop, by using SessionLab, it’s easy to go from an idea to a complete agenda . Start by dragging and dropping your core problem solving activities into place . Add timings, breaks and necessary materials before sharing your agenda with your colleagues.

The resulting agenda will be your guide to an effective and productive problem solving session that will also help you stay organized on the day!

Complete problem-solving methods

In this section, we’ll look at in-depth problem-solving methods that provide a complete end-to-end process for developing effective solutions. These will help guide your team from the discovery and definition of a problem through to delivering the right solution.

If you’re looking for an all-encompassing method or problem-solving model, these processes are a great place to start. They’ll ask your team to challenge preconceived ideas and adopt a mindset for solving problems more effectively.

Six Thinking Hats

Individual approaches to solving a problem can be very different based on what team or role an individual holds. It can be easy for existing biases or perspectives to find their way into the mix, or for internal politics to direct a conversation.

Six Thinking Hats is a classic method for identifying the problems that need to be solved and enables your team to consider them from different angles, whether that is by focusing on facts and data, creative solutions, or by considering why a particular solution might not work.

Like all problem-solving frameworks, Six Thinking Hats is effective at helping teams remove roadblocks from a conversation or discussion and come to terms with all the aspects necessary to solve complex problems.

The Six Thinking Hats #creative thinking #meeting facilitation #problem solving #issue resolution #idea generation #conflict resolution The Six Thinking Hats are used by individuals and groups to separate out conflicting styles of thinking. They enable and encourage a group of people to think constructively together in exploring and implementing change, rather than using argument to fight over who is right and who is wrong.

Lightning Decision Jam

Featured courtesy of Jonathan Courtney of AJ&Smart Berlin, Lightning Decision Jam is one of those strategies that should be in every facilitation toolbox. Exploring problems and finding solutions is often creative in nature, though as with any creative process, there is the potential to lose focus and get lost.

Unstructured discussions might get you there in the end, but it’s much more effective to use a method that creates a clear process and team focus.

In Lightning Decision Jam, participants are invited to begin by writing challenges, concerns, or mistakes on post-its without discussing them before then being invited by the moderator to present them to the group.

From there, the team vote on which problems to solve and are guided through steps that will allow them to reframe those problems, create solutions and then decide what to execute on.

By deciding the problems that need to be solved as a team before moving on, this group process is great for ensuring the whole team is aligned and can take ownership over the next stages.

Lightning Decision Jam (LDJ) #action #decision making #problem solving #issue analysis #innovation #design #remote-friendly It doesn’t matter where you work and what your job role is, if you work with other people together as a team, you will always encounter the same challenges: Unclear goals and miscommunication that cause busy work and overtime Unstructured meetings that leave attendants tired, confused and without clear outcomes. Frustration builds up because internal challenges to productivity are not addressed Sudden changes in priorities lead to a loss of focus and momentum Muddled compromise takes the place of clear decision- making, leaving everybody to come up with their own interpretation. In short, a lack of structure leads to a waste of time and effort, projects that drag on for too long and frustrated, burnt out teams. AJ&Smart has worked with some of the most innovative, productive companies in the world. What sets their teams apart from others is not better tools, bigger talent or more beautiful offices. The secret sauce to becoming a more productive, more creative and happier team is simple: Replace all open discussion or brainstorming with a structured process that leads to more ideas, clearer decisions and better outcomes. When a good process provides guardrails and a clear path to follow, it becomes easier to come up with ideas, make decisions and solve problems. This is why AJ&Smart created Lightning Decision Jam (LDJ). It’s a simple and short, but powerful group exercise that can be run either in-person, in the same room, or remotely with distributed teams.

Problem Definition Process

While problems can be complex, the problem-solving methods you use to identify and solve those problems can often be simple in design.

By taking the time to truly identify and define a problem before asking the group to reframe the challenge as an opportunity, this method is a great way to enable change.

Begin by identifying a focus question and exploring the ways in which it manifests before splitting into five teams who will each consider the problem using a different method: escape, reversal, exaggeration, distortion or wishful. Teams develop a problem objective and create ideas in line with their method before then feeding them back to the group.

This method is great for enabling in-depth discussions while also creating space for finding creative solutions too!

Problem Definition #problem solving #idea generation #creativity #online #remote-friendly A problem solving technique to define a problem, challenge or opportunity and to generate ideas.

The 5 Whys

Sometimes, a group needs to go further with their strategies and analyze the root cause at the heart of organizational issues. An RCA or root cause analysis is the process of identifying what is at the heart of business problems or recurring challenges.

The 5 Whys is a simple and effective method of helping a group go find the root cause of any problem or challenge and conduct analysis that will deliver results.

By beginning with the creation of a problem statement and going through five stages to refine it, The 5 Whys provides everything you need to truly discover the cause of an issue.

The 5 Whys #hyperisland #innovation This simple and powerful method is useful for getting to the core of a problem or challenge. As the title suggests, the group defines a problems, then asks the question “why” five times, often using the resulting explanation as a starting point for creative problem solving.

World Cafe is a simple but powerful facilitation technique to help bigger groups to focus their energy and attention on solving complex problems.

World Cafe enables this approach by creating a relaxed atmosphere where participants are able to self-organize and explore topics relevant and important to them which are themed around a central problem-solving purpose. Create the right atmosphere by modeling your space after a cafe and after guiding the group through the method, let them take the lead!

Making problem-solving a part of your organization’s culture in the long term can be a difficult undertaking. More approachable formats like World Cafe can be especially effective in bringing people unfamiliar with workshops into the fold.

World Cafe #hyperisland #innovation #issue analysis World Café is a simple yet powerful method, originated by Juanita Brown, for enabling meaningful conversations driven completely by participants and the topics that are relevant and important to them. Facilitators create a cafe-style space and provide simple guidelines. Participants then self-organize and explore a set of relevant topics or questions for conversation.

Discovery & Action Dialogue (DAD)

One of the best approaches is to create a safe space for a group to share and discover practices and behaviors that can help them find their own solutions.

With DAD, you can help a group choose which problems they wish to solve and which approaches they will take to do so. It’s great at helping remove resistance to change and can help get buy-in at every level too!

This process of enabling frontline ownership is great in ensuring follow-through and is one of the methods you will want in your toolbox as a facilitator.

Discovery & Action Dialogue (DAD) #idea generation #liberating structures #action #issue analysis #remote-friendly DADs make it easy for a group or community to discover practices and behaviors that enable some individuals (without access to special resources and facing the same constraints) to find better solutions than their peers to common problems. These are called positive deviant (PD) behaviors and practices. DADs make it possible for people in the group, unit, or community to discover by themselves these PD practices. DADs also create favorable conditions for stimulating participants’ creativity in spaces where they can feel safe to invent new and more effective practices. Resistance to change evaporates as participants are unleashed to choose freely which practices they will adopt or try and which problems they will tackle. DADs make it possible to achieve frontline ownership of solutions.

Design Sprint 2.0

Want to see how a team can solve big problems and move forward with prototyping and testing solutions in a few days? The Design Sprint 2.0 template from Jake Knapp, author of Sprint, is a complete agenda for a with proven results.

Developing the right agenda can involve difficult but necessary planning. Ensuring all the correct steps are followed can also be stressful or time-consuming depending on your level of experience.

Use this complete 4-day workshop template if you are finding there is no obvious solution to your challenge and want to focus your team around a specific problem that might require a shortcut to launching a minimum viable product or waiting for the organization-wide implementation of a solution.

Open space technology

Open space technology- developed by Harrison Owen – creates a space where large groups are invited to take ownership of their problem solving and lead individual sessions. Open space technology is a great format when you have a great deal of expertise and insight in the room and want to allow for different takes and approaches on a particular theme or problem you need to be solved.

Start by bringing your participants together to align around a central theme and focus their efforts. Explain the ground rules to help guide the problem-solving process and then invite members to identify any issue connecting to the central theme that they are interested in and are prepared to take responsibility for.

Once participants have decided on their approach to the core theme, they write their issue on a piece of paper, announce it to the group, pick a session time and place, and post the paper on the wall. As the wall fills up with sessions, the group is then invited to join the sessions that interest them the most and which they can contribute to, then you’re ready to begin!

Everyone joins the problem-solving group they’ve signed up to, record the discussion and if appropriate, findings can then be shared with the rest of the group afterward.

Open Space Technology #action plan #idea generation #problem solving #issue analysis #large group #online #remote-friendly Open Space is a methodology for large groups to create their agenda discerning important topics for discussion, suitable for conferences, community gatherings and whole system facilitation

Techniques to identify and analyze problems

Using a problem-solving method to help a team identify and analyze a problem can be a quick and effective addition to any workshop or meeting.

While further actions are always necessary, you can generate momentum and alignment easily, and these activities are a great place to get started.

We’ve put together this list of techniques to help you and your team with problem identification, analysis, and discussion that sets the foundation for developing effective solutions.

Let’s take a look!

Fishbone Analysis

Organizational or team challenges are rarely simple, and it’s important to remember that one problem can be an indication of something that goes deeper and may require further consideration to be solved.

Fishbone Analysis helps groups to dig deeper and understand the origins of a problem. It’s a great example of a root cause analysis method that is simple for everyone on a team to get their head around.

Participants in this activity are asked to annotate a diagram of a fish, first adding the problem or issue to be worked on at the head of a fish before then brainstorming the root causes of the problem and adding them as bones on the fish.

Using abstractions such as a diagram of a fish can really help a team break out of their regular thinking and develop a creative approach.

Fishbone Analysis #problem solving ##root cause analysis #decision making #online facilitation A process to help identify and understand the origins of problems, issues or observations.

Problem Tree

Encouraging visual thinking can be an essential part of many strategies. By simply reframing and clarifying problems, a group can move towards developing a problem solving model that works for them.

In Problem Tree, groups are asked to first brainstorm a list of problems – these can be design problems, team problems or larger business problems – and then organize them into a hierarchy. The hierarchy could be from most important to least important or abstract to practical, though the key thing with problem solving games that involve this aspect is that your group has some way of managing and sorting all the issues that are raised.

Once you have a list of problems that need to be solved and have organized them accordingly, you’re then well-positioned for the next problem solving steps.

Problem tree #define intentions #create #design #issue analysis A problem tree is a tool to clarify the hierarchy of problems addressed by the team within a design project; it represents high level problems or related sublevel problems.

SWOT Analysis

Chances are you’ve heard of the SWOT Analysis before. This problem-solving method focuses on identifying strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats is a tried and tested method for both individuals and teams.

Start by creating a desired end state or outcome and bare this in mind – any process solving model is made more effective by knowing what you are moving towards. Create a quadrant made up of the four categories of a SWOT analysis and ask participants to generate ideas based on each of those quadrants.

Once you have those ideas assembled in their quadrants, cluster them together based on their affinity with other ideas. These clusters are then used to facilitate group conversations and move things forward.

SWOT analysis #gamestorming #problem solving #action #meeting facilitation The SWOT Analysis is a long-standing technique of looking at what we have, with respect to the desired end state, as well as what we could improve on. It gives us an opportunity to gauge approaching opportunities and dangers, and assess the seriousness of the conditions that affect our future. When we understand those conditions, we can influence what comes next.

Agreement-Certainty Matrix

Not every problem-solving approach is right for every challenge, and deciding on the right method for the challenge at hand is a key part of being an effective team.

The Agreement Certainty matrix helps teams align on the nature of the challenges facing them. By sorting problems from simple to chaotic, your team can understand what methods are suitable for each problem and what they can do to ensure effective results.

If you are already using Liberating Structures techniques as part of your problem-solving strategy, the Agreement-Certainty Matrix can be an invaluable addition to your process. We’ve found it particularly if you are having issues with recurring problems in your organization and want to go deeper in understanding the root cause.

Agreement-Certainty Matrix #issue analysis #liberating structures #problem solving You can help individuals or groups avoid the frequent mistake of trying to solve a problem with methods that are not adapted to the nature of their challenge. The combination of two questions makes it possible to easily sort challenges into four categories: simple, complicated, complex , and chaotic . A problem is simple when it can be solved reliably with practices that are easy to duplicate. It is complicated when experts are required to devise a sophisticated solution that will yield the desired results predictably. A problem is complex when there are several valid ways to proceed but outcomes are not predictable in detail. Chaotic is when the context is too turbulent to identify a path forward. A loose analogy may be used to describe these differences: simple is like following a recipe, complicated like sending a rocket to the moon, complex like raising a child, and chaotic is like the game “Pin the Tail on the Donkey.” The Liberating Structures Matching Matrix in Chapter 5 can be used as the first step to clarify the nature of a challenge and avoid the mismatches between problems and solutions that are frequently at the root of chronic, recurring problems.

Organizing and charting a team’s progress can be important in ensuring its success. SQUID (Sequential Question and Insight Diagram) is a great model that allows a team to effectively switch between giving questions and answers and develop the skills they need to stay on track throughout the process.

Begin with two different colored sticky notes – one for questions and one for answers – and with your central topic (the head of the squid) on the board. Ask the group to first come up with a series of questions connected to their best guess of how to approach the topic. Ask the group to come up with answers to those questions, fix them to the board and connect them with a line. After some discussion, go back to question mode by responding to the generated answers or other points on the board.

It’s rewarding to see a diagram grow throughout the exercise, and a completed SQUID can provide a visual resource for future effort and as an example for other teams.

SQUID #gamestorming #project planning #issue analysis #problem solving When exploring an information space, it’s important for a group to know where they are at any given time. By using SQUID, a group charts out the territory as they go and can navigate accordingly. SQUID stands for Sequential Question and Insight Diagram.

To continue with our nautical theme, Speed Boat is a short and sweet activity that can help a team quickly identify what employees, clients or service users might have a problem with and analyze what might be standing in the way of achieving a solution.

Methods that allow for a group to make observations, have insights and obtain those eureka moments quickly are invaluable when trying to solve complex problems.

In Speed Boat, the approach is to first consider what anchors and challenges might be holding an organization (or boat) back. Bonus points if you are able to identify any sharks in the water and develop ideas that can also deal with competitors!

Speed Boat #gamestorming #problem solving #action Speedboat is a short and sweet way to identify what your employees or clients don’t like about your product/service or what’s standing in the way of a desired goal.

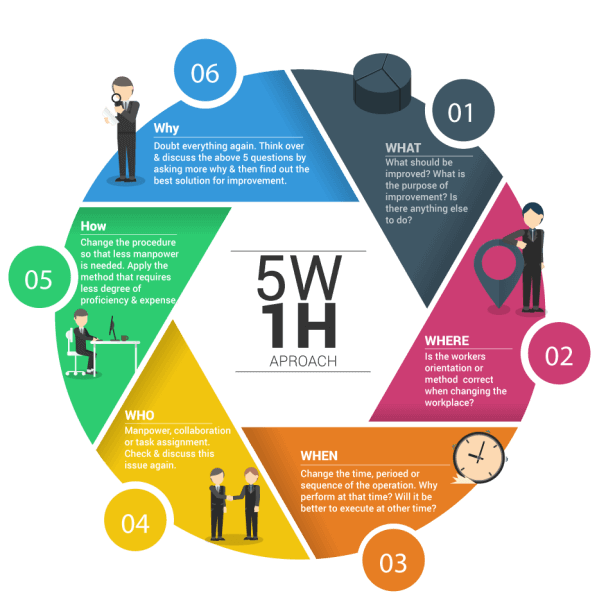

The Journalistic Six

Some of the most effective ways of solving problems is by encouraging teams to be more inclusive and diverse in their thinking.

Based on the six key questions journalism students are taught to answer in articles and news stories, The Journalistic Six helps create teams to see the whole picture. By using who, what, when, where, why, and how to facilitate the conversation and encourage creative thinking, your team can make sure that the problem identification and problem analysis stages of the are covered exhaustively and thoughtfully. Reporter’s notebook and dictaphone optional.

The Journalistic Six – Who What When Where Why How #idea generation #issue analysis #problem solving #online #creative thinking #remote-friendly A questioning method for generating, explaining, investigating ideas.

Individual and group perspectives are incredibly important, but what happens if people are set in their minds and need a change of perspective in order to approach a problem more effectively?

Flip It is a method we love because it is both simple to understand and run, and allows groups to understand how their perspectives and biases are formed.

Participants in Flip It are first invited to consider concerns, issues, or problems from a perspective of fear and write them on a flip chart. Then, the group is asked to consider those same issues from a perspective of hope and flip their understanding.

No problem and solution is free from existing bias and by changing perspectives with Flip It, you can then develop a problem solving model quickly and effectively.

Flip It! #gamestorming #problem solving #action Often, a change in a problem or situation comes simply from a change in our perspectives. Flip It! is a quick game designed to show players that perspectives are made, not born.

LEGO Challenge

Now for an activity that is a little out of the (toy) box. LEGO Serious Play is a facilitation methodology that can be used to improve creative thinking and problem-solving skills.

The LEGO Challenge includes giving each member of the team an assignment that is hidden from the rest of the group while they create a structure without speaking.

What the LEGO challenge brings to the table is a fun working example of working with stakeholders who might not be on the same page to solve problems. Also, it’s LEGO! Who doesn’t love LEGO!

LEGO Challenge #hyperisland #team A team-building activity in which groups must work together to build a structure out of LEGO, but each individual has a secret “assignment” which makes the collaborative process more challenging. It emphasizes group communication, leadership dynamics, conflict, cooperation, patience and problem solving strategy.

What, So What, Now What?

If not carefully managed, the problem identification and problem analysis stages of the problem-solving process can actually create more problems and misunderstandings.

The What, So What, Now What? problem-solving activity is designed to help collect insights and move forward while also eliminating the possibility of disagreement when it comes to identifying, clarifying, and analyzing organizational or work problems.

Facilitation is all about bringing groups together so that might work on a shared goal and the best problem-solving strategies ensure that teams are aligned in purpose, if not initially in opinion or insight.

Throughout the three steps of this game, you give everyone on a team to reflect on a problem by asking what happened, why it is important, and what actions should then be taken.

This can be a great activity for bringing our individual perceptions about a problem or challenge and contextualizing it in a larger group setting. This is one of the most important problem-solving skills you can bring to your organization.

W³ – What, So What, Now What? #issue analysis #innovation #liberating structures You can help groups reflect on a shared experience in a way that builds understanding and spurs coordinated action while avoiding unproductive conflict. It is possible for every voice to be heard while simultaneously sifting for insights and shaping new direction. Progressing in stages makes this practical—from collecting facts about What Happened to making sense of these facts with So What and finally to what actions logically follow with Now What . The shared progression eliminates most of the misunderstandings that otherwise fuel disagreements about what to do. Voila!

Journalists

Problem analysis can be one of the most important and decisive stages of all problem-solving tools. Sometimes, a team can become bogged down in the details and are unable to move forward.

Journalists is an activity that can avoid a group from getting stuck in the problem identification or problem analysis stages of the process.

In Journalists, the group is invited to draft the front page of a fictional newspaper and figure out what stories deserve to be on the cover and what headlines those stories will have. By reframing how your problems and challenges are approached, you can help a team move productively through the process and be better prepared for the steps to follow.

Journalists #vision #big picture #issue analysis #remote-friendly This is an exercise to use when the group gets stuck in details and struggles to see the big picture. Also good for defining a vision.

Problem-solving techniques for brainstorming solutions

Now you have the context and background of the problem you are trying to solving, now comes the time to start ideating and thinking about how you’ll solve the issue.

Here, you’ll want to encourage creative, free thinking and speed. Get as many ideas out as possible and explore different perspectives so you have the raw material for the next step.

Looking at a problem from a new angle can be one of the most effective ways of creating an effective solution. TRIZ is a problem-solving tool that asks the group to consider what they must not do in order to solve a challenge.

By reversing the discussion, new topics and taboo subjects often emerge, allowing the group to think more deeply and create ideas that confront the status quo in a safe and meaningful way. If you’re working on a problem that you’ve tried to solve before, TRIZ is a great problem-solving method to help your team get unblocked.

Making Space with TRIZ #issue analysis #liberating structures #issue resolution You can clear space for innovation by helping a group let go of what it knows (but rarely admits) limits its success and by inviting creative destruction. TRIZ makes it possible to challenge sacred cows safely and encourages heretical thinking. The question “What must we stop doing to make progress on our deepest purpose?” induces seriously fun yet very courageous conversations. Since laughter often erupts, issues that are otherwise taboo get a chance to be aired and confronted. With creative destruction come opportunities for renewal as local action and innovation rush in to fill the vacuum. Whoosh!

Mindspin

Brainstorming is part of the bread and butter of the problem-solving process and all problem-solving strategies benefit from getting ideas out and challenging a team to generate solutions quickly.

With Mindspin, participants are encouraged not only to generate ideas but to do so under time constraints and by slamming down cards and passing them on. By doing multiple rounds, your team can begin with a free generation of possible solutions before moving on to developing those solutions and encouraging further ideation.

This is one of our favorite problem-solving activities and can be great for keeping the energy up throughout the workshop. Remember the importance of helping people become engaged in the process – energizing problem-solving techniques like Mindspin can help ensure your team stays engaged and happy, even when the problems they’re coming together to solve are complex.

MindSpin #teampedia #idea generation #problem solving #action A fast and loud method to enhance brainstorming within a team. Since this activity has more than round ideas that are repetitive can be ruled out leaving more creative and innovative answers to the challenge.

The Creativity Dice

One of the most useful problem solving skills you can teach your team is of approaching challenges with creativity, flexibility, and openness. Games like The Creativity Dice allow teams to overcome the potential hurdle of too much linear thinking and approach the process with a sense of fun and speed.

In The Creativity Dice, participants are organized around a topic and roll a dice to determine what they will work on for a period of 3 minutes at a time. They might roll a 3 and work on investigating factual information on the chosen topic. They might roll a 1 and work on identifying the specific goals, standards, or criteria for the session.

Encouraging rapid work and iteration while asking participants to be flexible are great skills to cultivate. Having a stage for idea incubation in this game is also important. Moments of pause can help ensure the ideas that are put forward are the most suitable.

The Creativity Dice #creativity #problem solving #thiagi #issue analysis Too much linear thinking is hazardous to creative problem solving. To be creative, you should approach the problem (or the opportunity) from different points of view. You should leave a thought hanging in mid-air and move to another. This skipping around prevents premature closure and lets your brain incubate one line of thought while you consciously pursue another.

Idea and Concept Development

Brainstorming without structure can quickly become chaotic or frustrating. In a problem-solving context, having an ideation framework to follow can help ensure your team is both creative and disciplined.

In this method, you’ll find an idea generation process that encourages your group to brainstorm effectively before developing their ideas and begin clustering them together. By using concepts such as Yes and…, more is more and postponing judgement, you can create the ideal conditions for brainstorming with ease.

Idea & Concept Development #hyperisland #innovation #idea generation Ideation and Concept Development is a process for groups to work creatively and collaboratively to generate creative ideas. It’s a general approach that can be adapted and customized to suit many different scenarios. It includes basic principles for idea generation and several steps for groups to work with. It also includes steps for idea selection and development.

Problem-solving techniques for developing and refining solutions

The success of any problem-solving process can be measured by the solutions it produces. After you’ve defined the issue, explored existing ideas, and ideated, it’s time to develop and refine your ideas in order to bring them closer to a solution that actually solves the problem.

Use these problem-solving techniques when you want to help your team think through their ideas and refine them as part of your problem solving process.

Improved Solutions

After a team has successfully identified a problem and come up with a few solutions, it can be tempting to call the work of the problem-solving process complete. That said, the first solution is not necessarily the best, and by including a further review and reflection activity into your problem-solving model, you can ensure your group reaches the best possible result.

One of a number of problem-solving games from Thiagi Group, Improved Solutions helps you go the extra mile and develop suggested solutions with close consideration and peer review. By supporting the discussion of several problems at once and by shifting team roles throughout, this problem-solving technique is a dynamic way of finding the best solution.

Improved Solutions #creativity #thiagi #problem solving #action #team You can improve any solution by objectively reviewing its strengths and weaknesses and making suitable adjustments. In this creativity framegame, you improve the solutions to several problems. To maintain objective detachment, you deal with a different problem during each of six rounds and assume different roles (problem owner, consultant, basher, booster, enhancer, and evaluator) during each round. At the conclusion of the activity, each player ends up with two solutions to her problem.

Four Step Sketch

Creative thinking and visual ideation does not need to be confined to the opening stages of your problem-solving strategies. Exercises that include sketching and prototyping on paper can be effective at the solution finding and development stage of the process, and can be great for keeping a team engaged.

By going from simple notes to a crazy 8s round that involves rapidly sketching 8 variations on their ideas before then producing a final solution sketch, the group is able to iterate quickly and visually. Problem-solving techniques like Four-Step Sketch are great if you have a group of different thinkers and want to change things up from a more textual or discussion-based approach.

Four-Step Sketch #design sprint #innovation #idea generation #remote-friendly The four-step sketch is an exercise that helps people to create well-formed concepts through a structured process that includes: Review key information Start design work on paper, Consider multiple variations , Create a detailed solution . This exercise is preceded by a set of other activities allowing the group to clarify the challenge they want to solve. See how the Four Step Sketch exercise fits into a Design Sprint

Ensuring that everyone in a group is able to contribute to a discussion is vital during any problem solving process. Not only does this ensure all bases are covered, but its then easier to get buy-in and accountability when people have been able to contribute to the process.

1-2-4-All is a tried and tested facilitation technique where participants are asked to first brainstorm on a topic on their own. Next, they discuss and share ideas in a pair before moving into a small group. Those groups are then asked to present the best idea from their discussion to the rest of the team.

This method can be used in many different contexts effectively, though I find it particularly shines in the idea development stage of the process. Giving each participant time to concretize their ideas and develop them in progressively larger groups can create a great space for both innovation and psychological safety.

1-2-4-All #idea generation #liberating structures #issue analysis With this facilitation technique you can immediately include everyone regardless of how large the group is. You can generate better ideas and more of them faster than ever before. You can tap the know-how and imagination that is distributed widely in places not known in advance. Open, generative conversation unfolds. Ideas and solutions are sifted in rapid fashion. Most importantly, participants own the ideas, so follow-up and implementation is simplified. No buy-in strategies needed! Simple and elegant!

15% Solutions

Some problems are simpler than others and with the right problem-solving activities, you can empower people to take immediate actions that can help create organizational change.

Part of the liberating structures toolkit, 15% solutions is a problem-solving technique that focuses on finding and implementing solutions quickly. A process of iterating and making small changes quickly can help generate momentum and an appetite for solving complex problems.

Problem-solving strategies can live and die on whether people are onboard. Getting some quick wins is a great way of getting people behind the process.

It can be extremely empowering for a team to realize that problem-solving techniques can be deployed quickly and easily and delineate between things they can positively impact and those things they cannot change.

15% Solutions #action #liberating structures #remote-friendly You can reveal the actions, however small, that everyone can do immediately. At a minimum, these will create momentum, and that may make a BIG difference. 15% Solutions show that there is no reason to wait around, feel powerless, or fearful. They help people pick it up a level. They get individuals and the group to focus on what is within their discretion instead of what they cannot change. With a very simple question, you can flip the conversation to what can be done and find solutions to big problems that are often distributed widely in places not known in advance. Shifting a few grains of sand may trigger a landslide and change the whole landscape.

Problem-solving techniques for making decisions and planning

After your group is happy with the possible solutions you’ve developed, now comes the time to choose which to implement. There’s more than one way to make a decision and the best option is often dependant on the needs and set-up of your group.

Sometimes, it’s the case that you’ll want to vote as a group on what is likely to be the most impactful solution. Other times, it might be down to a decision maker or major stakeholder to make the final decision. Whatever your process, here’s some techniques you can use to help you make a decision during your problem solving process.

How-Now-Wow Matrix

The problem-solving process is often creative, as complex problems usually require a change of thinking and creative response in order to find the best solutions. While it’s common for the first stages to encourage creative thinking, groups can often gravitate to familiar solutions when it comes to the end of the process.

When selecting solutions, you don’t want to lose your creative energy! The How-Now-Wow Matrix from Gamestorming is a great problem-solving activity that enables a group to stay creative and think out of the box when it comes to selecting the right solution for a given problem.

Problem-solving techniques that encourage creative thinking and the ideation and selection of new solutions can be the most effective in organisational change. Give the How-Now-Wow Matrix a go, and not just for how pleasant it is to say out loud.

How-Now-Wow Matrix #gamestorming #idea generation #remote-friendly When people want to develop new ideas, they most often think out of the box in the brainstorming or divergent phase. However, when it comes to convergence, people often end up picking ideas that are most familiar to them. This is called a ‘creative paradox’ or a ‘creadox’. The How-Now-Wow matrix is an idea selection tool that breaks the creadox by forcing people to weigh each idea on 2 parameters.

Impact and Effort Matrix

All problem-solving techniques hope to not only find solutions to a given problem or challenge but to find the best solution. When it comes to finding a solution, groups are invited to put on their decision-making hats and really think about how a proposed idea would work in practice.

The Impact and Effort Matrix is one of the problem-solving techniques that fall into this camp, empowering participants to first generate ideas and then categorize them into a 2×2 matrix based on impact and effort.

Activities that invite critical thinking while remaining simple are invaluable. Use the Impact and Effort Matrix to move from ideation and towards evaluating potential solutions before then committing to them.

Impact and Effort Matrix #gamestorming #decision making #action #remote-friendly In this decision-making exercise, possible actions are mapped based on two factors: effort required to implement and potential impact. Categorizing ideas along these lines is a useful technique in decision making, as it obliges contributors to balance and evaluate suggested actions before committing to them.

If you’ve followed each of the problem-solving steps with your group successfully, you should move towards the end of your process with heaps of possible solutions developed with a specific problem in mind. But how do you help a group go from ideation to putting a solution into action?

Dotmocracy – or Dot Voting -is a tried and tested method of helping a team in the problem-solving process make decisions and put actions in place with a degree of oversight and consensus.

One of the problem-solving techniques that should be in every facilitator’s toolbox, Dot Voting is fast and effective and can help identify the most popular and best solutions and help bring a group to a decision effectively.

Dotmocracy #action #decision making #group prioritization #hyperisland #remote-friendly Dotmocracy is a simple method for group prioritization or decision-making. It is not an activity on its own, but a method to use in processes where prioritization or decision-making is the aim. The method supports a group to quickly see which options are most popular or relevant. The options or ideas are written on post-its and stuck up on a wall for the whole group to see. Each person votes for the options they think are the strongest, and that information is used to inform a decision.

Straddling the gap between decision making and planning, MoSCoW is a simple and effective method that allows a group team to easily prioritize a set of possible options.

Use this method in a problem solving process by collecting and summarizing all your possible solutions and then categorize them into 4 sections: “Must have”, “Should have”, “Could have”, or “Would like but won‘t get”.

This method is particularly useful when its less about choosing one possible solution and more about prioritorizing which to do first and which may not fit in the scope of your project. In my experience, complex challenges often require multiple small fixes, and this method can be a great way to move from a pile of things you’d all like to do to a structured plan.

MoSCoW #define intentions #create #design #action #remote-friendly MoSCoW is a method that allows the team to prioritize the different features that they will work on. Features are then categorized into “Must have”, “Should have”, “Could have”, or “Would like but won‘t get”. To be used at the beginning of a timeslot (for example during Sprint planning) and when planning is needed.

When it comes to managing the rollout of a solution, clarity and accountability are key factors in ensuring the success of the project. The RAACI chart is a simple but effective model for setting roles and responsibilities as part of a planning session.

Start by listing each person involved in the project and put them into the following groups in order to make it clear who is responsible for what during the rollout of your solution.

- Responsibility (Which person and/or team will be taking action?)

- Authority (At what “point” must the responsible person check in before going further?)

- Accountability (Who must the responsible person check in with?)

- Consultation (Who must be consulted by the responsible person before decisions are made?)

- Information (Who must be informed of decisions, once made?)

Ensure this information is easily accessible and use it to inform who does what and who is looped into discussions and kept up to date.

RAACI #roles and responsibility #teamwork #project management Clarifying roles and responsibilities, levels of autonomy/latitude in decision making, and levels of engagement among diverse stakeholders.

Problem-solving warm-up activities

All facilitators know that warm-ups and icebreakers are useful for any workshop or group process. Problem-solving workshops are no different.

Use these problem-solving techniques to warm up a group and prepare them for the rest of the process. Activating your group by tapping into some of the top problem-solving skills can be one of the best ways to see great outcomes from your session.

Check-in / Check-out

Solid processes are planned from beginning to end, and the best facilitators know that setting the tone and establishing a safe, open environment can be integral to a successful problem-solving process. Check-in / Check-out is a great way to begin and/or bookend a problem-solving workshop. Checking in to a session emphasizes that everyone will be seen, heard, and expected to contribute.

If you are running a series of meetings, setting a consistent pattern of checking in and checking out can really help your team get into a groove. We recommend this opening-closing activity for small to medium-sized groups though it can work with large groups if they’re disciplined!

Check-in / Check-out #team #opening #closing #hyperisland #remote-friendly Either checking-in or checking-out is a simple way for a team to open or close a process, symbolically and in a collaborative way. Checking-in/out invites each member in a group to be present, seen and heard, and to express a reflection or a feeling. Checking-in emphasizes presence, focus and group commitment; checking-out emphasizes reflection and symbolic closure.

Doodling Together

Thinking creatively and not being afraid to make suggestions are important problem-solving skills for any group or team, and warming up by encouraging these behaviors is a great way to start.

Doodling Together is one of our favorite creative ice breaker games – it’s quick, effective, and fun and can make all following problem-solving steps easier by encouraging a group to collaborate visually. By passing cards and adding additional items as they go, the workshop group gets into a groove of co-creation and idea development that is crucial to finding solutions to problems.

Doodling Together #collaboration #creativity #teamwork #fun #team #visual methods #energiser #icebreaker #remote-friendly Create wild, weird and often funny postcards together & establish a group’s creative confidence.

Show and Tell

You might remember some version of Show and Tell from being a kid in school and it’s a great problem-solving activity to kick off a session.

Asking participants to prepare a little something before a workshop by bringing an object for show and tell can help them warm up before the session has even begun! Games that include a physical object can also help encourage early engagement before moving onto more big-picture thinking.

By asking your participants to tell stories about why they chose to bring a particular item to the group, you can help teams see things from new perspectives and see both differences and similarities in the way they approach a topic. Great groundwork for approaching a problem-solving process as a team!

Show and Tell #gamestorming #action #opening #meeting facilitation Show and Tell taps into the power of metaphors to reveal players’ underlying assumptions and associations around a topic The aim of the game is to get a deeper understanding of stakeholders’ perspectives on anything—a new project, an organizational restructuring, a shift in the company’s vision or team dynamic.

Constellations

Who doesn’t love stars? Constellations is a great warm-up activity for any workshop as it gets people up off their feet, energized, and ready to engage in new ways with established topics. It’s also great for showing existing beliefs, biases, and patterns that can come into play as part of your session.

Using warm-up games that help build trust and connection while also allowing for non-verbal responses can be great for easing people into the problem-solving process and encouraging engagement from everyone in the group. Constellations is great in large spaces that allow for movement and is definitely a practical exercise to allow the group to see patterns that are otherwise invisible.

Constellations #trust #connection #opening #coaching #patterns #system Individuals express their response to a statement or idea by standing closer or further from a central object. Used with teams to reveal system, hidden patterns, perspectives.

Draw a Tree

Problem-solving games that help raise group awareness through a central, unifying metaphor can be effective ways to warm-up a group in any problem-solving model.

Draw a Tree is a simple warm-up activity you can use in any group and which can provide a quick jolt of energy. Start by asking your participants to draw a tree in just 45 seconds – they can choose whether it will be abstract or realistic.

Once the timer is up, ask the group how many people included the roots of the tree and use this as a means to discuss how we can ignore important parts of any system simply because they are not visible.

All problem-solving strategies are made more effective by thinking of problems critically and by exposing things that may not normally come to light. Warm-up games like Draw a Tree are great in that they quickly demonstrate some key problem-solving skills in an accessible and effective way.

Draw a Tree #thiagi #opening #perspectives #remote-friendly With this game you can raise awarness about being more mindful, and aware of the environment we live in.

Closing activities for a problem-solving process

Each step of the problem-solving workshop benefits from an intelligent deployment of activities, games, and techniques. Bringing your session to an effective close helps ensure that solutions are followed through on and that you also celebrate what has been achieved.

Here are some problem-solving activities you can use to effectively close a workshop or meeting and ensure the great work you’ve done can continue afterward.

One Breath Feedback

Maintaining attention and focus during the closing stages of a problem-solving workshop can be tricky and so being concise when giving feedback can be important. It’s easy to incur “death by feedback” should some team members go on for too long sharing their perspectives in a quick feedback round.

One Breath Feedback is a great closing activity for workshops. You give everyone an opportunity to provide feedback on what they’ve done but only in the space of a single breath. This keeps feedback short and to the point and means that everyone is encouraged to provide the most important piece of feedback to them.

One breath feedback #closing #feedback #action This is a feedback round in just one breath that excels in maintaining attention: each participants is able to speak during just one breath … for most people that’s around 20 to 25 seconds … unless of course you’ve been a deep sea diver in which case you’ll be able to do it for longer.

Who What When Matrix

Matrices feature as part of many effective problem-solving strategies and with good reason. They are easily recognizable, simple to use, and generate results.

The Who What When Matrix is a great tool to use when closing your problem-solving session by attributing a who, what and when to the actions and solutions you have decided upon. The resulting matrix is a simple, easy-to-follow way of ensuring your team can move forward.

Great solutions can’t be enacted without action and ownership. Your problem-solving process should include a stage for allocating tasks to individuals or teams and creating a realistic timeframe for those solutions to be implemented or checked out. Use this method to keep the solution implementation process clear and simple for all involved.

Who/What/When Matrix #gamestorming #action #project planning With Who/What/When matrix, you can connect people with clear actions they have defined and have committed to.

Response cards

Group discussion can comprise the bulk of most problem-solving activities and by the end of the process, you might find that your team is talked out!