An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Measuring best practices for workplace safety, health and wellbeing: The Workplace Integrated Safety and Health Assessment

Glorian sorensen.

1 Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA

2 Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA

Emily Sparer

Jessica a.r. williams.

3 University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City, KS

Daniel Gundersen

Leslie i. boden.

4 Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, MA

Jack T. Dennerlein

5 Northeastern University, Boston, MA

Dean Hashimoto

6 Partners HealthCare, Inc., Boston, MA

7 Boston College Law School, Newton Centre, MA

Jeffrey N. Katz

8 Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA

Deborah L. McLellan

Cassandra a. okechukwu, nicolaas p. pronk.

9 HealthPartners Institute, Minneapolis, MN

Anna Revette

Gregory r. wagner, associated data.

To present a measure of effective workplace organizational policies, programs and practices that focuses on working conditions and organizational facilitators of worker safety, health and wellbeing: the Workplace Integrated Safety and Health (WISH) Assessment.

Development of this assessment used an iterative process involving a modified Delphi method, extensive literature reviews, and systematic cognitive testing.

The assessment measures six core constructs identified as central to best practices for protecting and promoting worker safety, health and wellbeing: leadership commitment; participation; policies, programs and practices that foster supportive working conditions; comprehensive and collaborative strategies; adherence to federal and state regulations and ethical norms; and data-driven change.

Conclusions

The WISH Assessment holds promise as a tool that may inform organizational priority setting and guide research around causal pathways influencing implementation and outcomes related to these approaches.

INTRODUCTION

Efforts to protect and promote the safety, health, and wellbeing of workers have increasingly focused on integrating the complex and dynamic systems of the work organization and work environment. 1 – 3 The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) applies this integrated approach in the Total Worker Health ® (TWH) initiative by attending to “policies, programs, and practices that integrate protection from work-related safety and health hazards with promotion of injury and illness prevention efforts to advance worker well-being.” 4 NIOSH has defined best practices as a set of essential elements for TWH that prioritizes a hazard-free work environment and recognizes the significant role of job-related factors in workers’ health and wellbeing. 5 , 6

Increasingly, others have also emphasized the importance of improvements in working conditions as central to best practice recommendations. 7 – 15 For example, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s efforts have focused on building a culture of health in the workplace. 16 Continuous improvement systems have relied on employee participation as a means of shaping positive working conditions. 17 – 19 In Great Britain, continuous improvement processes are employed through a set of “management standards” that assess and address stressors in the workplace, including demands, control, support, relationships, role, and organizational change. 20 Researchers have reported benefits to this integrated systems approach, including reductions in pain and occupational injury and disability rates; 21 – 26 strengthened health and safety programs; 27 , 28 improvements in health behaviors; 29 – 38 enhanced rates of employee participation in programs; 39 and reduced costs. 28

Assessment of the extent to which a workplace adheres to best practice recommendations related to an integrated systems approach is important for several reasons. Understanding relationships between working conditions and worker safety and health outcomes can inform priority-setting and decision making for researchers, policy-makers, and employers alike, and may motivate employer actions to improve workplace conditions. 40 In turn, identifying the impact of worker health and safety on business-related outcomes, such as worker performance, productivity, and turnover, may help to demonstrate the importance of protecting and promoting worker health for the bottom line. 41 Baseline data with follow up assessments can also provide a means for tracking improvements in working conditions and related health outcomes over time. An important part of the process for evaluating workplace adherence to recommendations and understanding its relationship to worker and business outcomes is the creation of assessment tools that effectively capture implementation of best practice recommendations.

In 2013, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Center for Work, Health and Wellbeing published a set of “Indicators of Integration” that were designed to assess the extent to which an organization has implemented an approach integrating occupational safety and health with worksite health promotion. 1 This instrument assessed four domains: organizational leadership and commitment; collaboration between health protection and worksite health promotion; supportive organizational policies and practices (including accountability and training, management and employee engagement, benefits and incentives to support workplace health promotion and protection, integrated evaluation and surveillance); and comprehensive program content. The instrument was validated in two samples, 42 , 43 and has played as useful role in the evolving dialogue around integrated approaches to worker safety, health and wellbeing. 44 , 45 There is a need, however, for building on this work toward assessment of more conceptually grounded and practical constructs that measure the implementation of systems approaches focusing on improving working conditions as a means of protecting and promoting worker safety, health and wellbeing.

This manuscript describes an improved measure that reflects the Center’s conceptual model, which articulates the central role of working conditions in shaping health and safety outcomes as well as enterprise outcomes such as absenteeism and turnover ( Figure 1 ). 2 Working conditions, placed centrally in the model as core determinants of worker health and safety, encompass the physical environment and the organization of work (i.e., psycho-social factors, job design and demands, health and safety climate). The model highlights the potential interactions across systems, guiding exploration of the shared effects of the physical environment and the organization of work. Working conditions serve as a pathway from enterprise and workforce characteristics and effective policies, programs, and practices, to worker safety and health outcomes, as well as to more proximal outcomes such as health-related behaviors. Effective policies, programs, and practices may also contribute to improvements in enterprise outcomes such as turnover and health care costs. Feedback loops underscore the complexity of the system of inter-relationships across multiple dimensions, and highlight the potential synergy of intervention effects.

Systems level conceptual model centered around working conditions.

The purpose of this paper is to present a new measure of effective workplace organizational policies, programs and practices that focuses on working conditions as well as organizational facilitators of worker safety, health and wellbeing: the Workplace Integrated Safety and Health (WISH) Assessment. The objective of the WISH Assessment is to evaluate the extent to which workplaces implement effective comprehensive approaches to protect and promote worker health, safety and wellbeing. The policies, programs and practices encompassed by these approaches include both those designed to prevent work-related injuries and illnesses, and those designed to enhance overall workforce health and wellbeing.

Like the Indicators of Integration, this assessment is designed to be completed at the organizational level by employer representatives, such as directors of human resources, occupational safety, or employee health. These representatives are likely to be knowledgeable of organizational priorities, as well as policies, programs and practices related to workplace safety and health. Moreover, these representatives are in the position to influence the cultural and structural re-alignment necessary for integrated approaches. These organizational assessments are increasingly being used by policymakers, organizational leadership, and health and safety committees to guide goal setting and decision making. Organizational assessments such as this one may additionally complement worker surveys that can effectively capture employee practices as well as their perceptions of working conditions.

The WISH Assessment differs from the Indicators of Integration in two important ways: it embraces an increased focus on the central role of working conditions (as illustrated in Figure 1 ), and it expands assessment of best practice systems approaches to include a broader definition of protecting and promoting worker safety, health and wellbeing. This paper also describes the methods used to develop this instrument.

Investigators from the Harvard Chan School Center for Work, Health and Wellbeing, a TWH Center for Excellence representing multiple institutions in the Boston area, developed the WISH Assessment. 46 This instrument measures workplace-level implementation of policies, programs and practices that protect and promote worker safety, health and wellbeing. Accordingly, the intended respondents are organizational representatives who are knowledgeable about existing policies, programs and practices at workplaces, such as executives at small businesses, or directors of human resources or safety departments. Development of the WISH Assessment relied on an iterative process involving a modified Delphi method, extensive literature reviews, and systematic cognitive testing.

Delphi method and literature review

The Center’s conceptual model 2 and related literature provided a guiding framework for the development of the WISH Assessment. As a starting point, we used constructs and related measures included in the Center’s published 1 and validated 42 , 43 Indicators of Integration tool. Based on an extensive review of literature, we expanded and revised the constructs captured by the instrument from four to seven. Next, we reviewed these constructs and their definitions using an iterative modified Delphi process 47 with an expert review panel, including Center investigators. We reviewed the literature to identify extant items for these and similar constructs, placing a priority on the inclusion of validated measures where feasible. To ensure content validity and adequate coverage across attributes for each construct, we reviewed working drafts of the instrument with the Center’s External Advisory Board, as well as members of other TWH Centers of Excellence. 48 Through repeated discussions, iterative review and revisions in six meetings over ten months, the Center members reached consensus related to a set of core domains and related measures. The working draft of the instrument was further reviewed by a survey methodologist, and prepared for cognitive testing. Following three rounds of cognitive testing and revision, as described below, Center investigators again reviewed and finalized this working version of the WISH Assessment.

Cognitive testing methods

The purpose of cognitive testing is to ensure that the items included on a survey effectively measure the intended constructs and are uniformly understood by potential respondents. The process focuses on the performance of each candidate item when used with members of the intended respondent group, and specifically assesses comprehension, information retrieval, judgment/estimation, and selection of response category. 49 , 50 In the development of the WISH Assessment, we tested the instrument through three rounds of interviews.

Data Collection

Participants were asked to fill out the self-administered paper (N=15) or web (N=4) survey and participate in a telephone-administered qualitative interview with a trained interviewer. Participants received the survey 48 hours prior to the interview, and were encouraged to complete the survey as close to the actual interview as possible. They were not explicitly encouraged to consult with others, nor were they told not to.

The semi-structured interviews were conducted using a structured interview guide and retrospective probing techniques. The first round focused on comprehension of key attributes for each item (e.g., concepts of integration and collaborative environments) and of key words or phrases in the context of the question and instrument. Items revised following round 1 were again tested in a second round using the same approach. The focus of round 2 was to assess the adequacy of revisions in addressing the problems identified in round 1. A third round of interviews was conducted to confirm there were no additional problems due to revisions based on round 2. Across all rounds, the interviews concluded with a series of questions about the participant’s overall experience in completing the survey. For example, participants could provide general feedback on the survey content and the time required to complete the survey, and could comment on questions that didn’t fit within the survey or were duplicative. Participants were compensated with a $20 Amazon gift card for their time.

Participants were selected using purposive sampling to ensure diversity across industries and organizational roles, and included directors of human resources, occupational health, safety, and similar positions from hospitals (n=9), risk management (n=2), technology (n=2), transportation (n=2), community health center (n=1), manufacturing (n=1), laboratory research and development (n=1), and emergency response (n=1). Participants were identified through the Center for Work, Health and Wellbeing, and included attendees at a continuing education course and former collaborators on other projects. New participants were included in subsequent rounds of testing in order to ensure that revisions to items from each round adequately addressed the limitations, and that items were appropriately and uniformly interpreted among respondents.

Following each round, feedback was summarized by item. Participant feedback was used to determine if the question wording needed modification. Each item was first considered on its own, and then assessed in terms of its fit in measuring its construct. A survey methodologist made suggested revisions which were then reviewed and discussed by the author team and interviewers to ensure that they retained substantive focus on the construct. We revised items when participants found terminology unclear or when participants’ answers did not map onto the intended construct. An item was removed if it was found to be redundant or did not adequately map onto the intended construct, and its deletion did not compromise content validity. We analyzed data across industry, and also assessed responses specific to the hospital industry, which included the most respondents.

Description of the constructs and measures

We identified six core constructs as central to best practices for protecting and promoting worker safety, health and wellbeing through the Delphi process and literature review. The items included in each construct with their response categories are included in Table 1 . Following the Indicators of Integration, this assessment was designed to be answered by one or more persons within an organization who are likely to be familiar with the organization’s policies, programs and practices related to worker safety, health and wellbeing. Below, we present each construct, including its definition, rationale for inclusion, and sources of the items included.

Workplace Integrated Safety and Health (WISH) Assessment

| This brief survey is designed to assess the extent to which organizations effectively implement integrated approaches to worker safety, health and wellbeing. The term “integrated approaches” refers to policies, programs, and practices that aim to prevent work-related injuries and illnesses and enhance overall workforce health and wellbeing. This survey is meant to be completed by health and safety representatives, either in human resources or in safety, at the middle management level. There are no right or wrong answers–Your responses are meant to reflect your understanding of policies, practices and programs currently implemented within your organization. |

| 1. The following questions refer to leadership commitment. We define the term “leadership commitment” to mean the following: An organization’s leadership makes worker safety, health, and well-being a clear priority for the entire organization. They drive accountability and provide the necessary resources and environment to create positive working conditions. Response Categories: Please indicate how often you feel your organization or its leaders do each of the following: Not all the time, some of the time, most of the time, all of the time. |

| a. The company’s leadership, such as senior leaders and middle managers, communicate their commitment to a work environment that supports employee safety, health, and wellbeing. |

| b. The organization allocates enough resources such as enough workers and money to implement policies or programs to protect and promote worker safety and health. |

| c. Our company’s leadership, such as senior leaders and managers, take responsibility for ensuring a safe and healthy work environment. |

| d. Worker health and safety are part of the organization’s mission, vision or business objectives. |

| e. The importance of health and safety is communicated across all levels of the organization, both formally and informally. |

| f. The importance of health and safety is consistently reflected in actions across all levels of the organization, both formally and informally. |

| 2. The following questions refer to participation. We define the term “participation” to mean the following: Stakeholders at every level of an organization, including organized labor or other worker organizations if present, help plan and carry out efforts to protect and promote worker safety and health. Response categories: For these collaborative activities or programs, please indicate how often you believe your organization implements each: not at all, some of the time, most of the time, all of the time. |

| a. Managers and employees work together in planning, implementing, and evaluating comprehensive safety and health programs, policies, and practices for employees. |

| b. This company has a joint worker-management committee that addresses efforts to protect and promote worker safety and health. |

| c. In this organization, managers across all levels consistently seek employee involvement and feedback in decision making. |

| d. Employees are encouraged to voice concerns about working conditions without fear of retaliation. |

| e. Leadership, such as supervisors and managers, initiate discussions with employees to identify hazards or other concerns in the work environment. |

| 3. The following questions refer to policies, programs, and practices focused on positive working conditions. We define this term to mean the following: The organization enhances worker safety, health, and well-being with policies and practices that improve working conditions. Response categories: For each of the following policies or practices, please indicate the degree to which they are implemented at your company: not at all, somewhat, mostly, completely. |

| a. The workplace is routinely evaluated by staff trained to identify potential health and safety hazards. |

| b. Supervisors are responsible for identifying unsafe working conditions on their units. |

| c. Supervisors are responsible for correcting unsafe working conditions on their units. |

| d. This workplace provides a supportive environment for safe and healthy behaviors, such as a tobacco-free policy, healthy food options, or facilities for physical activity. |

| e. Organizational policies or programs are in place to support employees when they are dealing with personal or family issues. |

| f. Leadership, such as supervisors and managers, make sure that workers are able to take their entitled breaks during work (e.g. meal breaks). |

| g. Supervisors and managers make sure workers are able to take their earned times away from work such as sick time, vacation, and parental leave. |

| h. This organization ensures that policies to prevent harm to employees from abuse, harassment, discrimination, and violence are followed. |

| i. This organization has trainings for workers and managers across all levels to prevent harm to employees from abuse, harassment, discrimination, and violence. |

| j. This workplace provides support to employees who are returning to work after time off due to work-related health conditions. |

| k. This workplace provides support to employees who are returning to work after time off due to non-work related health conditions. |

| l. This organization takes proactive measures to make sure that the employee’s workload is reasonable, for example, that employees can usually complete their assigned job tasks within their shift. |

| m. Employees have the resources such as equipment and training do their jobs safely and well. |

| n. All employees in this organization receive paid leave, including sick leave. |

| 4. The following questions refer to comprehensive and collaborative strategies. We define this term to mean the following: Employees from across the organization work together to develop comprehensive health and safety initiatives. Response categories: For the following collaborative or comprehensive policies, programs, or practices, please indicate the degree to which your company implements each: not at all, somewhat, mostly, completely. |

| a. This company has a comprehensive approach to promote and protect worker safety and health. This includes collaborative efforts across departments as well as education and programs for individuals and policies about the work environment. |

| b. This company has a comprehensive approach to worker wellbeing. This includes collaboration across departments in efforts to prevent work-related illness and injury and to promote worker health. |

| c. This company coordinates policies, programs, and practices for worker health safety, and wellbeing across departments. |

| d. Managers are held accountable for implementing best practices to protect worker safety, health, and wellbeing, for example through their performance reviews. |

| e. Managers are given resources, such as equipment and trainings, for implementing best practices to protect and promote worker safety, health, and wellbeing. |

| f. This company prioritizes protection and promotion of worker safety and health when selecting vendors and subcontractors. |

| 5. The following questions refer to adherence. We define the term “adherence” to mean the following: The organization adheres to federal and state regulations, as well as ethical norms, that advance worker safety, health, and well-being. Response categories: For each of the following statements, please indicate the degree to which you believe your company adheres to or prioritizes standards and regulations: not at all, somewhate, mostly, completely. |

| a. This organization complies with standards for legal conduct. |

| b. In this organization, people show sincere respect for others’ ideas, values, beliefs |

| c. This workplace complies with regulations aimed at eliminating or minimizing potential exposures to recognized hazards. |

| d. This company ensures that safeguards regarding worker confidentiality, privacy and non-retaliation protections are followed. |

| e. The wages for the lowest-paid employees in this organization seem to be enough to cover basic living expenses such as housing and food. |

| 6. The following questions refer to data-driven change. We define this term to mean the following: Regular evaluation guides an organization’s priority setting, decision making, and continuous improvement of worker safety, health, and well-being initiatives. Response categories: Please indicate the degree to which your company does each of the following: not at all, somewhat,mostly, completely. |

| a. The effects of policies and programs to promote worker safety and health are measured using data from multiple sources, such as injury data, employee feedback, and absence records |

| b. Data from multiple sources on health, safety, and wellbeing are integrated and presented to leadership on a regular basis. |

| c. Evaluations of policies, programs and practices to protect and promote worker health are used to improve future efforts. |

| d. Integrated data on employee safety and health outcomes are coordinated across all relevant departments. |

Leadership Commitment , defined as: “Leadership makes worker safety, health, and well-being a clear priority for the entire organization. They drive accountability and provide the necessary resources and environment to create positive working conditions.” This construct was included in our Indicators of Integration; items in the WISH Assessment were adapted from this prior measure, as well as from other sources. 1 , 41 , 51 , 52 Organizational leadership has been linked to an array of worker safety, health and wellbeing outcomes, 53 , 54 including organizational safety climate, 55 , 56 job-related wellbeing, 57 , 58 workplace injuries, 59 , 60 and health behaviors. 61 , 62 This element recognizes that top management is ultimately responsible for setting priorities that define worker and worksite safety and health as part of the organization’s vision and mission. 14 , 16 Leadership roles include providing the resources needed for implementing best practices related to worker safety, health and wellbeing; establishing accountability for implementation of relevant policies and practices; and effectively communicating these priorities through formal and informal channels. 51 , 52

Participation , defined as: “Stakeholders at every level of an organization, including labor unions or other worker organizations if present, help plan and carry out efforts to protect and promote worker safety and health.” Many organizations have mechanisms in place to engage employees and managers in decision making and planning. These mechanisms may be used in planning and implementing integrated policies and programs, for example through joint worker-management committees that combine efforts to protect and promote worker safety, health and wellbeing. 7 , 63 , 64 Employee participation in decision-making facilitates a broader organizational culture of health, safety and wellbeing. Participation also includes encouraging employees to identify and report threats to safety and health, without fear of retaliation and with the expectation that their concerns will be addressed. Items included were adapted from the Indicators of Integration 1 and a self-assessment checklist from the Center for the Promotion of Health in the New England Workplace. 65

Policies, programs and practices that foster supportive working conditions , defined as: “The organization enhances worker safety, health, and well-being with policies and practices that improve working conditions.” These policies, programs and practices are central to the conceptual model presented in Figure 1 . Items include measures of the physical work environment and the organization of work (i.e., psychosocial factors, job tasks, demands, and resources), and are drawn from multiple sources. 1 , 41 , 66 – 69 The focus on working conditions is based on principles of prevention articulated in a hierarchy of controls framework, which has been applied within TWH. 10 , 70 Eliminating or reducing recognized hazards, whether in the physical work environment or the organizational environment, provides the most effective means of reducing exposure to potential for hazards on the job. Policies and processes to protect workers from physical hazards include routine inspections of the work environment, with mechanisms in place for correction of identified hazards, as well as policies that support safe and healthy behaviors, such as tobacco control policies. A supportive work organization includes safeguards against job strain, work overload, and harassment, 7 , 71 – 74 as well as supports for workers as they address work-life balance, return to work after an illness or injury, and take entitled breaks, including meal breaks as well as sick and vacation time. 75 , 76

Comprehensive and collaborative strategies , defined as: “Employees from across the organization work together to develop comprehensive health and safety initiatives.” Measures were adapted from our Indicators of Integration 1 and also relied on recent recommendations from the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 41 Although efforts to protect and promote worker safety and health have traditionally functioned independently, this construct acknowledges the benefits derived from collaboration across departments within an organization to protect and promote worker safety and health, both through policies about the work environment as well as education for workers. These efforts carry through into the selection of subcontractors and vendors, recognizing their impact on working conditions.

Adherence , defined as: “ The organization adheres to federal and state regulations, as well as ethical norms, that advance worker safety, health, and well-being.” The importance of this construct has been recognized by multiple organizations, whose contributions and metrics were incorporated in the measures included here. 7 , 77 – 79 Employers have a legal obligation to provide a safe and healthy work environment. 7 , 68 There is also significant agreement that any system that includes health and safety metrics must include safeguards for employee confidentiality and privacy. 7 , 41

Data-driven change , defined as: “Regular evaluation guides an organization’s priority setting, decision making, and continuous improvement of worker safety, health, and well-being initiatives.” Building health metrics into corporate reporting underscores the importance of worker health and safety as a business priority. 16 , 80 Feedback to leadership based on evaluation and monitoring of integrated programs, policies and practices can provide a basis for ongoing quality improvement. An integrated system that reports outcomes related both to occupational health as well as health behaviors and other health and wellbeing indicators can point to shared root causes within the conditions of work. 1 , 14

Cognitive testing results

We tested the WISH Assessment in three rounds of cognitive testing with a total of 19 participants. (See Appendix 1 for changes made to the items across the three rounds of testing.) On average, participants completed the self-administered survey in about 10–15 minutes, and the cognitive interviews took an average of 45 minutes. In the first round of cognitive testing, three participants completed a web version of the survey, and five, a paper-and-pencil version. Because we found no differences in concerns raised, the second round used only a paper survey, whereas the third included web respondents to confirm no differences in the final instrument. Changes made to the survey items were based on input from multiple respondents over the three rounds of interviews, and did not rely specifically on input from any one individual.

For items with uniform interpretation, revisions were made if respondents suggested a word or phrase that would clarify the question that investigators felt retained substantive focus. In addition, some items were dropped because they revealed multiple sources of problems, were too difficult to answer, or were identified as redundant. The first round of testing led to the removal of seven items and the modifying of 24 items. The second round of cognitive testing revealed that problems with the question wording remained with 15 questions in the context of the full survey. No additional questions were removed. These specific questions were updated and re-tested among three participants.

Throughout the cognitive testing process, we found several items to have either ambiguous terminology resulting in non-uniform or restrictive interpretation, inadequate framing of key terms and constructs, or lack of knowledge or perceived ability to provide an answer, resulting in poor information retrieval or mapping to the construct. Items measuring integration or collaboration within an organization were more often identified as problematic; to address this concern, we included a description of these constructs in the survey’s introduction to frame the survey for respondents. Although there was uniform interpretation of items asking about employee’s living wage, some respondents reported they did not have knowledge to provide an accurate answer. Most other items revealed uniform interpretation and no concerns regarding information retrieval or selecting response categories.

Looking at the items by construct, we identified particular concerns with items measuring two domains: “ policies, programs, and practices that foster supportive working conditions” and “adherence ” to norms and regulations. To address these concerns, we revised these items by improving the description of constructs or the terms in the respective sections’ introductions, using less ambiguous wording and integrating appropriate examples as necessary. We found commonalities across the responses in the remaining four domains, and describe our specific remediation process for each of these domains:

Leadership commitment

In round 1, we found a lack of clarity for the concept of “leadership.” For example, one respondent from the health care industry reported that: “[senior leaders and middle managers] should be distinguished and not conflated because there are several layers of management.” As a result, several respondents expressed difficulty retrieving accurate information due to level-specific answers. One respondent from a laboratory research and development company noted “[…] leadership communicate their commitment to safety and health through written policies. If you were to add supervisors – people closer to the front line – it would be different.” We addressed this concern by rewriting the introduction for this domain to clearly define “leadership commitment” and remove mention of leadership levels. However, we retained the wording “[…] such as senior leaders and middle managers, […]” in two items to reflect that organizations have channels through which commitment is communicated or enforced.

Participation

The questions for collaborative participation were largely identified as clear and uniformly interpreted. However, there was lack of clarity regarding who the key stakeholders were, particularly in the introduction. In addition, respondents reported that the introduction was too wordy and had a high literacy bar. Given these concerns and the suggestion that the use of the term “culture” was too academic, so we omitted use of this term. Some respondents expressed difficulty retrieving an appropriate answer due to this lack of clear framing of items in the introduction. We addressed this concern by rewriting the introduction to emphasize the definition of “participation” in the context of an organization’s activities that ensure worker safety and health. Feedback from round 2 found that this helped frame the item set more clearly. However, the word “encourage” in “In this organizational culture, managers encourage employees to get involved in making decisions” was identified as ambiguous. This was changed to “[…] seek employee involvement and feedback […]”.

Comprehensive and collaborative strategies

The most common feedback, expressed among several participants in multiple industries, for items in this domain was difficulty with the concept of “comprehensive,” i.e., that programming should address both prevention of illness and injury and promotion of worker health and safety. To a lesser extent, respondents also found difficulty with the “collaborative” concept. For example, some respondents including those from the hospital industry and in risk management, expressed difficulty responding to an item that included both “prevent” and “enhance,” which were perceived as “two different questions within this question.” We addressed these concerns by more clearly defining the two core constructs in a revised introduction. Moreover, we revised items to retain both “prevent and promote” while more clearly framing the question in context of collaboration. For example, the item “This company has a comprehensive approach to worker wellbeing that includes efforts to prevent work-related illness and injury as well as to enhance worker health” was revised to “This company has a comprehensive approach to worker wellbeing. This includes collaboration across departments in efforts to prevent work-related illness and injury and to promote worker health.”

Data-driven change

For this domain, we found evidence of poor cueing for the concepts of integration and coordination in the context of using data to produce organizational change. For example, several respondents from the hospital industry expressed that they did not understand what was meant by “integrated” in the context of “Summary reports on integrated policies and programs are presented to leadership on a regular basis, while also protecting employee confidentiality,” or “coordinated system” in context of “Data related to employee safety and health outcomes are integrated within a coordinated system.” Remediation focused on clarifying the context and definitions for integration and coordination. First, the introduction was revised to explicitly define data-driven change. Secondly, items were reworded to clarify integration and coordination. For example, “Summary reports on integrated policies and programs are presented to leadership on a regular basis, while also protecting employee confidentiality” was revised to “Data from multiple sources on health, safety, and wellbeing are integrated and presented to leadership on a regular basis.”

Our analyses also underscored commonalities across industries even when these issues seemed industry-specific. For example, comments from several participants suggested that a product-based mission may often dominate concerns about worker safety and health. In healthcare, this may be manifested by prioritizing patient care and safety over worker health and safety, or in other industries by a focus on production or timeline goals. Across industries, there was widespread agreement that Employee Assistant Programs was the primary resource for supporting employees dealing with personal or family issues.

Effective policies, programs and practices contribute to improvements in worker health, safety and wellbeing, as well as to enterprise outcomes such as improved employee morale, reduced absence and turnover, potentially reduced healthcare costs, and improved quality of services. 2 , 40 , 81 – 84 This manuscript presents the Workplace Integrated Safety and Health (WISH) Assessment, designed to evaluate the extent to which organizations implement best practice recommendations for an integrated, systems approach to protecting and promoting worker safety, health and wellbeing. This instrument builds on the Indicators of Integration, previously published and validated by the Center for Work, Health and Wellbeing. 1 , 42 , 43 We have expanded this tool based on the conceptual model presented in Figure 1 , 2 which prioritizes working conditions as determinants of worker safety, health and wellbeing. In addition, the WISH Assessment is designed to measure the extent to which an organization implements best practice recommendations. These constructs have also been used to inform in the Center’s guidelines for implementing best practice integrated approaches. 8

A growing range of metrics are available to assess organizational approaches to worker safety and health. The Integrated Health & Safety Index (IHS Index), created by the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine in collaboration with the Underwriters Laboratories, focuses on translating health and safety into value for businesses using three dimensions: economic, environmental and social standards. 41 By focusing on value, this measure has the potential to bolster the business case for health and safety. 41 , 85 The HERO Health and Well-being Best Practices Scorecard in Collaboration with Mercer is an online tool that allows employers to receive emailed feedback on their health and well-being practices. 86 Similarly, the American Heart Association’s Workplace Health Achievement Index provides an on-line self-assessment scorecard that includes comparisons with other companies. 87 The health metrics designed by the Vitality Institute include both a long and short form questionnaire, both with automatic scoring. 88 The Center for the Promotion of Health in the New England Workplace (CPH-NEW) has developed a tool to assess organizational readiness for implementing an integrated approach 11 and is developing a tool that focuses on participatory engagement of workers, with the goal of involving workers in the process of prioritizing health and safety issues and then developing and evaluating the proposed solutions. 89 Other measures of the work environment, such as the Health and Safety Executive Managements Standards Indicator Tool used in the United Kingdom, are designed to be taken by workers and so can provide detailed information on conditions as they are experienced by workers, but do not capture company-level policies and programs. 90 The WISH Assessment, designed to assess a company’s use of best practices for health and safety, is substantially shorter than the IHS Index and the HERO Scorecard, does not require the compilation of metrics and does not use individual employee data. In addition, in comparison to these other measures, the WISH Assessment can be used to guide organizations towards best practices and can be easily completed by organizations that might not have the resources to use the more extensive assessments.

Next steps in the development of the WISH Assessment include validation of the instrument across multiple samples, and design and testing of a scoring system. We validated the Indicators of Integration in two samples and found it to have convergent validity and high internal consistency, and to express one unified factor even when slight changes were made to adapt the measure. 42 , 43 We expect to follow a similar approach in validating this tool and assessing its dimensionality in large samples using factor analysis. Our goal is to design a scoring system that would be appropriate for both applied and research applications. As such, we expect the scoring algorithm to be simple enough for auto-calculation.

This tool may ultimately serve multiple purposes. As a research tool, it may provide a measure of workplace best practices that can be examined as determinants of worker safety and health outcomes. After being validated, the WISH Assessment may be used to explore organizational characteristics that may be associated with implementation of best practices. This instrument also responds to calls for practical tools for organizations implementing an integrated approach and focusing on working conditions. 41 The Center used the Indicators of Integration as part of a larger assessment process in three small-to-medium manufacturing businesses to inform organizations’ priority setting and decision making around the integration of occupational safety and health and health promotion. 91 In-person group discussions with key staff and executive leaders were used to rate each question on the scorecard, resulting in actionable steps based on identified gaps. Similarly, a validated WISH Assessment could be translated into a scorecard to be used to inform priority setting, decision making and to monitor changes over time in conditions of work and related health and safety outcomes. The Center has also applied the constructs defined in the WISH Assessment in its new best practice guidelines, 8 which include suggestions for formal and informal policies and practices ( Table 2 ).

Example Policies and Practices by each WISH construct.

| Construct | Formal Policies | Informal Practices |

|---|---|---|

| Physical environment Work organization Psychosocial environment | Physical environment Work organization Psychosocial environment | |

McLellan D, Moore W, Nagler E, Sorensen G. 2017. Implementing an integrated approach: Weaving worker health, safety, and well-being into the fabric of your organization. Dana-Farber Cancer Institute: Boston, MA. http://centerforworkhealth.sph.harvard.edu/

These indicators describe policies, programs and practices within the control of a specific organization or enterprise, and are most likely to apply to organizations that employ approximately 100 or more employees. The cognitive testing conducted to refine the items included in the WISH Assessment included representatives from organizations in selected settings; the generalizability of these results may therefore be restricted to similar types of organizations. There remains a need for exploring how this measure may function in different industries and across organizations of varying size. Although the purpose of the WISH instrument is to provide a measure that might be broadly useful across industries, we also recognize that each industry faces particular challenges due to the nature of what they do; supplementary questions may be needed to address these industry-specific concerns. Although this measure has not yet been validated, we believe it is important to share it and to explore opportunities for collaboration with other researchers interested in testing its psychometric properties and across populations and settings, in order to further develop this tool. It will ultimately be important as well to develop mechanisms for scoring this instrument, taking account potential weighting across the domains included.

Growing evidence clearly documents the benefits to be derived from integrated systems approaches for protecting and promoting worker safety, health and wellbeing. Practical, validated measures of best practices that are supported by existing evidence and do not place an undue burden on respondents are needed to support systematic study and organizational change. In cognitive testing, we demonstrated that the items included in this instrument effectively assess the defined constructs. Our goal was to create a measure that will be broadly useful and valid across industry, and might contribute to understanding differences and similarities by industry. Thus, the general applicability of this instrument is a strength in that it would allow for comparisons across industries, if so desired by substantive research. We also recognize the potential benefits of industry-specific versions of this instrument which may use this broader instrument as a base set of measures while also expanding on areas that are unique to a given industry. This may help increase understanding of industry-specific health and safety challenges. The WISH Assessment holds promise as a tool that may inform organizational priority setting and guide research around causal pathways influencing implementation and outcomes related to these approaches.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental digital content, acknowledgments.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (U19 OH008861) for the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Center for Work, Health and Well-being.

Conflict of Interest noted: None

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Systematic literature review on the effects of occupational safety and health (OSH) interventions at the workplace

Affiliation.

- 1 Johan Hviid Andersen, Professor, Department of Occupational Medicine, Danish Ramazzini Centre, Regional Hospital West Jutland - University Clinic, Gl. Landevej 61, 7400 Herning, Denmark. [email protected].

- PMID: 30370910

- DOI: 10.5271/sjweh.3775

Objectives The aim of this review was to assess the evidence that occupational safety and health (OSH) legislative and regulatory policy could improve the working environment in terms of reduced levels of industrial injuries and fatalities, musculoskeletal disorders, worker complaints, sick leave and adverse occupational exposures. Methods A systematic literature review covering the years 1966‒2017 (February) was undertaken to capture both published and gray literature studies of OSH work environment interventions with quantitative measures of intervention effects. Studies that met specified in- and exclusion criteria went through an assessment of methodological quality. Included studies were grouped into five thematic domains: (i) introduction of OHS legislation, (ii) inspection/enforcement activity, (iii) training, such as improving knowledge, (iv), campaigns, and (v) introduction of technical device, such as mechanical lifting aids. The evidence synthesis was based on meta-analysis and a modified Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach. Results The search for peer-reviewed literature identified 14 743 journal articles of which 45 fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were eligible for meta-analysis. We identified 5181 articles and reports in the gray literature, of which 16 were evaluated qualitatively. There was moderately strong evidence for improvement by OHS legislation and inspections with respect to injuries and compliance. Conclusions This review indicates that legislative and regulatory policy may reduce injuries and fatalities and improve compliance with OHS regulation. A major research gap was identified with respect to the effects of OSH regulation targeting psychological and musculoskeletal disorders.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Systematic review of qualitative literature on occupational health and safety legislation and regulatory enforcement planning and implementation. MacEachen E, Kosny A, Ståhl C, O'Hagan F, Redgrift L, Sanford S, Carrasco C, Tompa E, Mahood Q. MacEachen E, et al. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2016 Jan;42(1):3-16. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3529. Epub 2015 Oct 13. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2016. PMID: 26460511 Review.

- A systematic literature review of the effectiveness of occupational health and safety regulatory enforcement. Tompa E, Kalcevich C, Foley M, McLeod C, Hogg-Johnson S, Cullen K, MacEachen E, Mahood Q, Irvin E. Tompa E, et al. Am J Ind Med. 2016 Nov;59(11):919-933. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22605. Epub 2016 Jun 7. Am J Ind Med. 2016. PMID: 27273383 Review.

- Occupational safety and health enforcement tools for preventing occupational diseases and injuries. Mischke C, Verbeek JH, Job J, Morata TC, Alvesalo-Kuusi A, Neuvonen K, Clarke S, Pedlow RI. Mischke C, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Aug 30;(8):CD010183. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010183.pub2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013. PMID: 23996220 Review.

- Workplace health understandings and processes in small businesses: a systematic review of the qualitative literature. MacEachen E, Kosny A, Scott-Dixon K, Facey M, Chambers L, Breslin C, Kyle N, Irvin E, Mahood Q; Small Business Systematic Review Team. MacEachen E, et al. J Occup Rehabil. 2010 Jun;20(2):180-98. doi: 10.1007/s10926-009-9227-7. J Occup Rehabil. 2010. PMID: 20140483 Review.

- Exploratory Study on Occupational Health Hazards among Health Care Workers in the Philippines. Faller EM, Bin Miskam N, Pereira A. Faller EM, et al. Ann Glob Health. 2018 Aug 31;84(3):338-341. doi: 10.29024/aogh.2316. Ann Glob Health. 2018. PMID: 30835385 Free PMC article.

- Effectiveness of Occupational Safety and Health interventions: a long way to go. Vitrano G, Micheli GJL. Vitrano G, et al. Front Public Health. 2024 May 9;12:1292692. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1292692. eCollection 2024. Front Public Health. 2024. PMID: 38784580 Free PMC article. Review.

- Occupational health and safety regulatory interventions to improve the work environment: An evidence and gap map of effectiveness studies. Bondebjerg A, Filges T, Pejtersen JH, Kildemoes MW, Burr H, Hasle P, Tompa E, Bengtsen E. Bondebjerg A, et al. Campbell Syst Rev. 2023 Dec 11;19(4):e1371. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1371. eCollection 2023 Dec. Campbell Syst Rev. 2023. PMID: 38089568 Free PMC article.

- Effects of the Labor Inspection Authority's regulatory tools on physician-certified sick leave and employee health in Norwegian home-care services - a cluster randomized controlled trial. Finnanger Garshol B, Knardahl S, Emberland JS, Skare Ø, Johannessen HA. Finnanger Garshol B, et al. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2024 Jan 1;50(1):28-38. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.4126. Epub 2023 Oct 30. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2024. PMID: 37903341 Free PMC article. Clinical Trial.

- PROTOCOL: Occupational health and safety regulatory interventions to improve the work environment: An evidence and gap map of effectiveness studies. Bondebjerg A, Filges T, Pejtersen JH, Viinholt BCA, Burr H, Hasle P, Tompa E, Birkefoss K, Bengtsen E. Bondebjerg A, et al. Campbell Syst Rev. 2022 Apr 12;18(2):e1231. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1231. eCollection 2022 Jun. Campbell Syst Rev. 2022. PMID: 36911348 Free PMC article.

- Study of purchasing behavior evolution of work-safety-service based on hierarchical mixed supervision. Jingjing Z, Wei L. Jingjing Z, et al. Front Psychol. 2022 Nov 30;13:991539. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.991539. eCollection 2022. Front Psychol. 2022. PMID: 36532995 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health

Miscellaneous

- NCI CPTAC Assay Portal

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Health Safety & Wellbeing at Work: A review of the literature

In the changing world of work, health, safety and well-being are matters of continued and increasing concern for governments, employers and workers. The following document reviews the amassing body of literature in this field, focusing on topics and themes that are relevant to both local and global contexts. The key question guiding the review is a deceptively simple one: What makes for good health and safety at work? More specifically, the review is driven by the following questions: 1) What are the key factors of health, safety and well-being at work? 2) What can New Zealand learn from other jurisdictions? 3) What is the future of health, safety and well-being at work?

Related Papers

IOSH Research Report

Paul Almond

Work, Employment & Society

Clive Smallman

New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations

Paul Duignan

Gerard Zwetsloot

There is growing attention in industry for the Vision Zero strategy, which in terms of work-related health and safety is often labelled as Zero Accident Vision or Zero Harm. The consequences of a genuine commitment to Vision Zero for addressing health, safety and well-being and their synergies are discussed. The Vision Zero for work-related health, safety and well-being is based on the assumption that all accidents, harm and work-related diseases are preventable. Vision Zero for health, safety and well-being is then the ambition and commitment to create and ensure safe and healthy work and to prevent all accidents, harm and work-related diseases in order to achieve excellence in health, safety and well-being. Implementation of Vision Zero is a process – rather than a target, and healthy organizations make use of a wide range of options to facilitate this process. There is sufficient evidence that fatigue, stress and work organization factors are important determinants of safety beha...

International journal of …

Chris Cunningham

Chief Hyginus Chika Onuegbu JP,LLM, MA,MSc, FCTI, FCA

When a worker leaves his residence to work for the upkeep of his family and contribute to the economy of his society and nation, he does so with a believe that he will come back to the warm embrace of his family at least the way he was when he left them. He does not expect that the work will howsoever lead to his death or disability or injury or ill health. There is therefore no gainsaying that he has a right to demand this from the society and the nation and that his employer, the society and nation have a duty to ensure that this right to safety and health at work is respected.

Cristina Leovaridis

3rd International Conference on Human Security, 4-5 November 2016, Belgrade, Serbia, ISBN 978-86-80144-09-2

Valentina Ranaldi

Safety Science

Maureen Dollard

Ciencia & Tecnología para la Salud Visual y Ocular

Ivonne Constanza Valero-Pacheco

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Oman Chapter of Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review

Vartikka Indermun

IZA Institute of Labor Economics Discussion Paper Series

Ioannis Theodossiou

Procedia Economics and Finance

Rares Munteanu

Isaac Mintah

Journal of Education and Practice

Rosemary Mbogo

Valentine Smith , Zaheer Rajack

International Journal for Research in Applied Science & Engineering Technology (IJRASET)

IJRASET Publication

Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology

David Whyte

catherine grant

PsycEXTRA Dataset

Ala'a Shehabi

Muhammad Rafiqul Islam

Safety and Health for Workers - Research and Practical Perspective

Bankole Fasanya

Regulating Workplace Risks

Annie Thébaud-Mony

Elsa Underhill

Journal of Developing Country Studies, Vol 2, No.9, 2012. ISSN 2224-607X (Paper) ISSN 2225-0565 (Online)

Ruby Melody Agbola

Wesley McTernan

Frontiers in Psychology

Fabrizio Bracco

professor Tareq abdhulkadhum naser Alasadi

aditya jain

Risk Analysis VIII

Taleb Mounia

Doni Sutrisno

Mabelene Sim

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Open access

- Published: 20 June 2023

Impact assessment of e-trainings in occupational safety and health: a literature review

- Mohammad Mahdi Barati Jozan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5197-6260 1 ,

- Babak Daneshvar Ghorbani 2 ,

- Md Saifuddin Khalid ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3731-2564 3 ,

- Aynaz Lotfata ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7511-1755 4 &

- Hamed Tabesh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3081-0488 1

BMC Public Health volume 23 , Article number: 1187 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

6491 Accesses

4 Citations

Metrics details

Implementing workplace preventive interventions reduces occupational accidents and injuries, as well as the negative consequences of those accidents and injuries. Online occupational safety and health training is one of the most effective preventive interventions. This study aims to present current knowledge on e-training interventions, make recommendations on the flexibility, accessibility, and cost-effectiveness of online training, and identify research gaps and obstacles.

All studies that addressed occupational safety and health e-training interventions designed to address worker injuries, accidents, and diseases were chosen from PubMed and Scopus until 2021. Two independent reviewers conducted the screening process for titles, abstracts, and full texts, and disagreements on the inclusion or exclusion of an article were resolved by consensus and, if necessary, by a third reviewer. The included articles were analyzed and synthesized using the constant comparative analysis method.

The search identified 7,497 articles and 7,325 unique records. Following the title, abstract, and full-text screening, 25 studies met the review criteria. Of the 25 studies, 23 were conducted in developed and two in developing countries. The interventions were carried out on either the mobile platform, the website platform, or both. The study designs and the number of outcomes of the interventions varied significantly (multi-outcomes vs. single-outcome). Obesity, hypertension, neck/shoulder pain, office ergonomics issues, sedentary behaviors, heart disease, physical inactivity, dairy farm injuries, nutrition, respiratory problems, and diabetes were all addressed in the articles.

According to the findings of this literature study, e-trainings can significantly improve occupational safety and health. E-training is adaptable, affordable, and can increase workers’ knowledge and abilities, resulting in fewer workplace injuries and accidents. Furthermore, e-training platforms can assist businesses in tracking employee development and ensuring that training needs are completed. Overall, this analysis reveals that e-training has enormous promise in the field of occupational safety and health for both businesses and employees.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Occupational injuries and diseases are among the most serious public health issues [ 1 ]. According to the most recent International Labor Organization report (2017), over 2.78 million workers die each year as a result of occupational accidents and work-related diseases [ 2 ]. The most serious negative consequences of occupational accidents and injuries are long-term disabilities [ 3 ] reduced ability to perform job duties [ 3 , 4 , 5 ], early retirement [ 3 ], medical care expenditure [ 4 , 5 ], absenteeism [ 4 , 5 , 6 ], presenteeism [ 4 , 5 ], and death [ 3 ]. These cost the global economy 3.94% of the global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) [ 2 ]. In various countries, these costs range from 1.8 to 6% of GDP [ 3 ].Treatment and preventive interventions are two types of interventions used to reduce occupational diseases and injuries, as well as the negative consequences of these events [ 7 ].

Preventive interventions in occupational health aim to change the work condition to prevent occupational accidents and reduce their harmful effects. There are three types of preventive interventions: primary preventive interventions, secondary preventive interventions, and tertiary preventive interventions [ 7 ]. Primary preventive interventions aim to create conditions that will help to prevent occupational disease and injury. In other words, these interventions aim to eliminate or reduce workers’ exposure to workplace hazards. Secondary and tertiary preventive interventions attempt to prevent disease or injury progression in the post-accident steps [ 7 ]. The primary preventive interventions are divided into three types: Environmental interventions, clinical interventions, and behavioral interventions are the first three [ 8 ]. Environmental interventions attempt to eliminate the causes of occupational accidents by altering work methods, equipment, and physical space [ 9 ]. Clinical interventions (for example, pre-employment medical examinations [ 10 ]) use therapeutic methods to prevent disease [ 8 ]. Behavioral interventions aim to change workers’ behavior in order for them to be safer at work [ 8 ].

Many developing and developed countries implement occupational safety and health programs (OSH) for workers due to the importance of safe behavior in reducing the costs of occupational accidents and their negative consequences [ 11 ]. The most important component of the OSH program has been introduced as education [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has also identified worker, employee, and occupational medicine specialist training as a key component in improving worker health [ 17 ].

The two main approaches in occupational education are class-based education and e-learning. Simple and low-cost solution [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ], greater convenience [ 21 ], availability [ 18 , 21 , 22 , 24 ], high acceptance among the workforce [ 25 ], enhanced self-management and adherence in the target population [ 26 , 27 , 28 ], primary source for health-related information [ 29 , 30 ], internet availability for users [ 31 , 32 , 33 ], mobile phone availability for users [ 34 , 35 ], ability to use a personalized approach [ 23 ], flexibility to fit the users’ schedules [ 33 ], reach large numbers of participants [ 23 , 33 ] and prefer technology-enhanced educational programs [ 29 ] are the most important reasons that have made e-learning as a suitable alternative to traditional and class-based education.

In the last decade, studies [ 20 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ] have been conducted to evaluate the provision of online and personalized occupational health and safety training content. Systematic reviews have been conducted on the impact of occupational health and safety e-training in limited cases [ 23 , 40 , 41 , 42 ], such as limiting studies to a geographical area [ 41 ], an occupational safety and health problem [ 23 , 40 , 42 ], a type of intervention [ 23 ], and etc. The limitations of systematic reviews did not have the comprehensive outlook on e-training role in the behavioral change and improve health. Given these relevant premises, the goal of this study is to conduct a systematic review of published studies that have used e-training to reduce occupational accidents through the end of 2021.

With the increasing use of technology in the delivery of training programs, e-learning has become a popular mode of training delivery with several potential benefits, such as flexibility, accessibility, and cost-effectiveness. This study seeks to evaluate the impact of e-trainings in occupational safety and health by conducting a comprehensive literature review. The findings of this study contribute to the ongoing discussions on how technology can be leveraged to improve workplace safety measures and reduce accidents and injuries. Moreover, it is essential to understand the effectiveness of e-training programs compared to traditional training methods and identify best practices for developing effective e-training programs. This study aims to fill this gap in current knowledge by providing a comprehensive analysis of the existing literature on e-trainings in occupational safety and health.

This study has two primary objectives: providing up-to-date details on online occupational health and safety training interventions and offering recommendations, discussing research gaps and challenges in online occupational health and safety training interventions.

Materials and methods

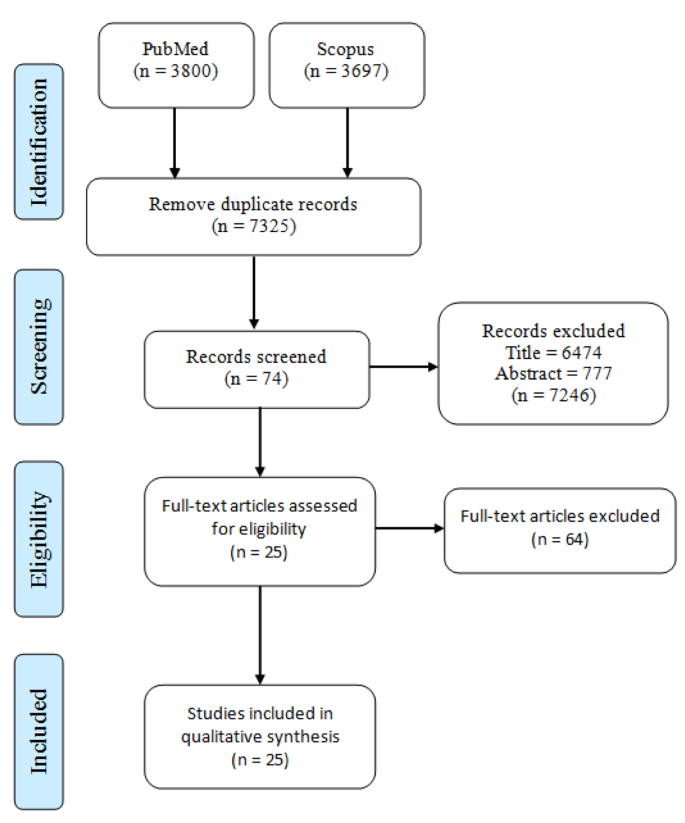

As a paper selection methodology, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [ 43 ] was utilized, which involves four phases: identification, screening, eligibility, and included. The first phase sets the search technique and databases used in the search. The title, abstract, and full text of the publications are assessed in the following steps, based on the inclusion-exclusion criteria set for the systematic review. The included articles are then determined. The qualitative synthesis is completed after the finalization of the included articles.

Identification phase: search strategy

A computer-based literature search in the PubMed and Scopus databases was carried out. These databases were searched until the end of 2021. The search used a combination of text terms and a hierarchically regulated vocabulary that was tailored to each database. The text terms were divided into workplace safety and health (Group 1) and e-training (Group 2). These groups were joined together with “AND.“ Group 1 terms included occupational health, occupational safety, workplace health, and workplace safety. e-Training, e-Education, online training, online learning, mobile training, and mobile education were all included in Group 2. The terms from each of the three categories were then joined together with “OR.“

Screening and eligibility phase

Determining the inclusion and exclusion criteria and the screening process are two important activities of this phase.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for this study involved educational interventions aimed at improving occupational safety and health among workers (Intervention) and published in English (Language) by the end of 2021 (Publication period). The interventions were designed for workers (Population) and delivered educational content through web or mobile-based platforms (Technology). The final inclusion criterion was that the interventions evaluate primarily outcomes related to occupational safety and health.

However, certain types of studies were excluded from the analysis. The interventions that were considered included those which examined multiple components or did not isolate the impact of training as a specific intervention component. The study population was also limited to excluding students, health professionals, disabled workers, military personnel, and drivers (Population). Outcome measures related to mental health, sleep, stress, and addiction were also excluded (Outcome). Similarly, studies utilizing 3D animation, Virtual Reality, Virtual game-based simulation, and 360-degree panoramas were excluded (Technology). Lastly, studies forced to use online education due to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) conditions were not considered.

Screening process

Two reviewers independently reviewed titles, abstracts, and full texts based on inclusion/exclusion criteria. Disagreements between the two reviewers on the inclusion/exclusion of an article were settled by consensus and, if required, by a third reviewer.

Included phase: analysis

A meta-analysis of the impact of e-training on enhancing occupational safety and health is impossible due to the different nature of the literature on the type of treatments, study design, primary and secondary outcomes, and evaluation approaches. As a result, this study explains the nature of the included studies’ implementation practice models in order to highlight the studies’ strengths and limitations and make recommendations for future research.

The comparative analysis method is used for the analysis and synthesis in order to extract the themes emerging from the evidence [ 44 ]. This method, like other qualitative data analysis methods, involved coding data into themes and then categorizing and drawing conclusions based on them. These codes contained a concept associated with that part of the article from which the code is extracted. To maintain consistency and create non-overlapping code sets, a clear definition was provided for each code [ 45 ]. The qualitative content analysis process includes eight steps: data preparation, reading the article carefully several times to obtain a sense of the whole, determining the critical information of each part of the article (transcripts), defining the unit of analysis using themes, development of coding scheme to organize data, coding the entire article based on the developed coding scheme, conclusion based on the coded data, and describing and interpreting the findings [ 45 ]. Two reviewers independently read the articles in-depth and coded them. The reviewers and the lead author compiled the obtained results, and if there were any differences, they tried to resolve them. The disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Each article was reviewed to extract methods, parameters, and the purpose of evaluating e-training. The following codes were extracted for each article: the purpose of study, study design, population study, the unit of allocation (workplace/individual), country, primary/secondary outcomes, platform, educational content structure, and evaluation of the study.

The computer-based literature search yielded 7,497 articles, of which 7,325 were identified after removing 172 duplicate papers. Six thousand four hundred articles were removed during the title review phase and 777 articles were removed during the abstract review phase. 64 articles were removed during the title review phase. Finally, 25 articles met the criteria for inclusion. Figure 1 depicts PRISMA flow diagram of this systematic review study. The articles included in this review are listed in Table 1 in appendix .

PRISMA flow diagram

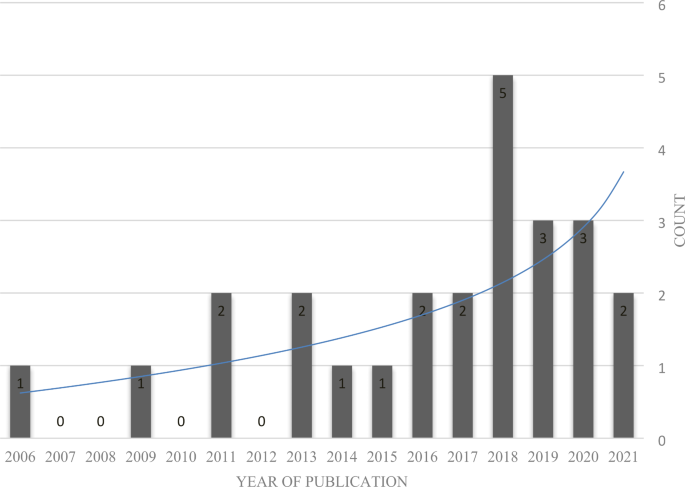

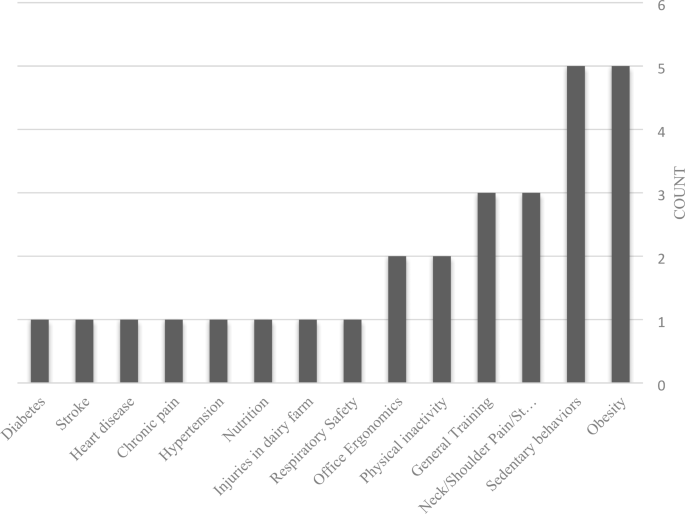

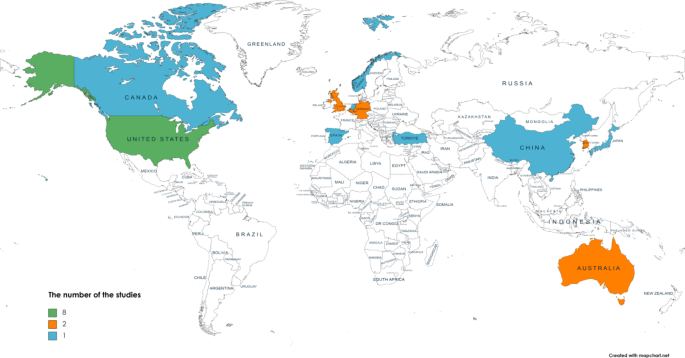

The summary of the evaluation of the articles is shown in Table 1 . E-training has been used in 9 areas of occupational safety and health: sedentary behaviors, obesity, neck/shoulder pain/stiffness and Low Back Pain (LBP), physical inactivity, office ergonomics, hypertension, nutrition, respiratory, and multi-topic. The number of the included studies based on the year of publication, topic and country is given in Figs. 2 and 3 , and Fig. 4 respectively.

The number of the included studies based on the publication year

The number of the included studies based on the topic

The number of the included studies based on each country. USA (n = 8); Australia, South Korea, UK, Germany, Belgium (n = 2), Japan, Turkey, Norway, Canada, Spain, China, Netherlands (n = 1)

Sedentary behaviors

A sedentary lifestyle is a significant public health concern in modern society [ 32 , 35 , 46 , 47 ], as it can lead to poor physical and mental health [ 48 , 49 , 50 ] and the development of serious diseases such as cancer, obesity, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease [ 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 ]. Sedentary behavior is defined as any waking behavior (sitting, reclining, or lying posture) that consumes 1.5 metabolic equivalents of energy [ 52 ] and is prevalent in office settings [ 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 ]. Inactive activities account for nearly 65–82% of working time in industrialized countries [ 64 , 65 , 66 ], and 54–77% of office workers sit all day [ 66 , 67 , 68 ]. To address the negative consequences of sedentary behavior in the workplace, effective interventions must be designed, including encouraging desk-based employees to spend at least 2–4 h standing or doing light activity, taking regular breaks from sitting [ 69 ], considering environmental factors [ 70 , 71 ]., addressing concerns about productivity [ 72 ], and increasing awareness among employees and employers through training programs [ 73 ]. E-training has been used in [ 36 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 ] to reduce sedentary behavior and address the mentioned challenges.

A theory-driven, web-based, computer-tailored application called Start to Stand has been developed to reduce sedentary behavior at work [ 36 ]. The application includes both mandatory and optional components. In the mandatory component, personalized advice on how to interrupt and reduce sitting was provided, and the optional component has five non-committal sections: interruptions in sedentary behaviors, replacing sedentary behaviors with standing, sedentary behaviors during commuting, sedentary behaviors during work breaks (e.g., lunch), and developing a sedentary behavior change action plan that motivates participants to achieve their objectives by creating an action plan. The application uses various theories, such as the Theory of Planned Behavior [ 77 ], self-determination theory [ 78 , 79 ], and self-regulation theory [ 80 ], to provide recommendations to users. In order to evaluate the implemented application, the accessibility of participants and the acceptability were reported. One hundred and twelve employees from public city service were invited to participate in the study. The feasibility test showed that education, employment status, level of breaks at work, and attitudes towards interrupting sitting at work were influential in requesting advice, and 39% of participants requested at least one non-committal section from the optional component. The acceptability test revealed that most participants found the advice interesting, relevant, and motivating. The majority of participants (98.0%) reported that they had reduced their sedentary behavior or intended to do so.