This document originally came from the Journal of Mammalogy courtesy of Dr. Ronald Barry, a former editor of the journal.

WRITING A SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH ARTICLE | Format for the paper | Edit your paper! | Useful books | FORMAT FOR THE PAPER Scientific research articles provide a method for scientists to communicate with other scientists about the results of their research. A standard format is used for these articles, in which the author presents the research in an orderly, logical manner. This doesn't necessarily reflect the order in which you did or thought about the work. This format is: | Title | Authors | Introduction | Materials and Methods | Results (with Tables and Figures ) | Discussion | Acknowledgments | Literature Cited | TITLE Make your title specific enough to describe the contents of the paper, but not so technical that only specialists will understand. The title should be appropriate for the intended audience. The title usually describes the subject matter of the article: Effect of Smoking on Academic Performance" Sometimes a title that summarizes the results is more effective: Students Who Smoke Get Lower Grades" AUTHORS 1. The person who did the work and wrote the paper is generally listed as the first author of a research paper. 2. For published articles, other people who made substantial contributions to the work are also listed as authors. Ask your mentor's permission before including his/her name as co-author. ABSTRACT 1. An abstract, or summary, is published together with a research article, giving the reader a "preview" of what's to come. Such abstracts may also be published separately in bibliographical sources, such as Biologic al Abstracts. They allow other scientists to quickly scan the large scientific literature, and decide which articles they want to read in depth. The abstract should be a little less technical than the article itself; you don't want to dissuade your potent ial audience from reading your paper. 2. Your abstract should be one paragraph, of 100-250 words, which summarizes the purpose, methods, results and conclusions of the paper. 3. It is not easy to include all this information in just a few words. Start by writing a summary that includes whatever you think is important, and then gradually prune it down to size by removing unnecessary words, while still retaini ng the necessary concepts. 3. Don't use abbreviations or citations in the abstract. It should be able to stand alone without any footnotes. INTRODUCTION What question did you ask in your experiment? Why is it interesting? The introduction summarizes the relevant literature so that the reader will understand why you were interested in the question you asked. One to fo ur paragraphs should be enough. End with a sentence explaining the specific question you asked in this experiment. MATERIALS AND METHODS 1. How did you answer this question? There should be enough information here to allow another scientist to repeat your experiment. Look at other papers that have been published in your field to get some idea of what is included in this section. 2. If you had a complicated protocol, it may helpful to include a diagram, table or flowchart to explain the methods you used. 3. Do not put results in this section. You may, however, include preliminary results that were used to design the main experiment that you are reporting on. ("In a preliminary study, I observed the owls for one week, and found that 73 % of their locomotor activity occurred during the night, and so I conducted all subsequent experiments between 11 pm and 6 am.") 4. Mention relevant ethical considerations. If you used human subjects, did they consent to participate. If you used animals, what measures did you take to minimize pain? RESULTS 1. This is where you present the results you've gotten. Use graphs and tables if appropriate, but also summarize your main findings in the text. Do NOT discuss the results or speculate as to why something happened; t hat goes in th e Discussion. 2. You don't necessarily have to include all the data you've gotten during the semester. This isn't a diary. 3. Use appropriate methods of showing data. Don't try to manipulate the data to make it look like you did more than you actually did. "The drug cured 1/3 of the infected mice, another 1/3 were not affected, and the third mouse got away." TABLES AND GRAPHS 1. If you present your data in a table or graph, include a title describing what's in the table ("Enzyme activity at various temperatures", not "My results".) For graphs, you should also label the x and y axes. 2. Don't use a table or graph just to be "fancy". If you can summarize the information in one sentence, then a table or graph is not necessary. DISCUSSION 1. Highlight the most significant results, but don't just repeat what you've written in the Results section. How do these results relate to the original question? Do the data support your hypothesis? Are your results consistent with what other investigators have reported? If your results were unexpected, try to explain why. Is there another way to interpret your results? What further research would be necessary to answer the questions raised by your results? How do y our results fit into the big picture? 2. End with a one-sentence summary of your conclusion, emphasizing why it is relevant. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This section is optional. You can thank those who either helped with the experiments, or made other important contributions, such as discussing the protocol, commenting on the manuscript, or buying you pizza. REFERENCES (LITERATURE CITED) There are several possible ways to organize this section. Here is one commonly used way: 1. In the text, cite the literature in the appropriate places: Scarlet (1990) thought that the gene was present only in yeast, but it has since been identified in the platypus (Indigo and Mauve, 1994) and wombat (Magenta, et al., 1995). 2. In the References section list citations in alphabetical order. Indigo, A. C., and Mauve, B. E. 1994. Queer place for qwerty: gene isolation from the platypus. Science 275, 1213-1214. Magenta, S. T., Sepia, X., and Turquoise, U. 1995. Wombat genetics. In: Widiculous Wombats, Violet, Q., ed. New York: Columbia University Press. p 123-145. Scarlet, S.L. 1990. Isolation of qwerty gene from S. cerevisae. Journal of Unusual Results 36, 26-31. EDIT YOUR PAPER!!! "In my writing, I average about ten pages a day. Unfortunately, they're all the same page." Michael Alley, The Craft of Scientific Writing A major part of any writing assignment consists of re-writing. Write accurately Scientific writing must be accurate. Although writing instructors may tell you not to use the same word twice in a sentence, it's okay for scientific writing, which must be accurate. (A student who tried not to repeat the word "hamster" produced this confusing sentence: "When I put the hamster in a cage with the other animals, the little mammals began to play.") Make sure you say what you mean. Instead of: The rats were injected with the drug. (sounds like a syringe was filled with drug and ground-up rats and both were injected together) Write: I injected the drug into the rat.

- Be careful with commonly confused words:

Temperature has an effect on the reaction. Temperature affects the reaction.

I used solutions in various concentrations. (The solutions were 5 mg/ml, 10 mg/ml, and 15 mg/ml) I used solutions in varying concentrations. (The concentrations I used changed; sometimes they were 5 mg/ml, other times they were 15 mg/ml.)

Less food (can't count numbers of food) Fewer animals (can count numbers of animals)

A large amount of food (can't count them) A large number of animals (can count them)

The erythrocytes, which are in the blood, contain hemoglobin. The erythrocytes that are in the blood contain hemoglobin. (Wrong. This sentence implies that there are erythrocytes elsewhere that don't contain hemoglobin.)

Write clearly

1. Write at a level that's appropriate for your audience.

"Like a pigeon, something to admire as long as it isn't over your head." Anonymous

2. Use the active voice. It's clearer and more concise than the passive voice.

Instead of: An increased appetite was manifested by the rats and an increase in body weight was measured. Write: The rats ate more and gained weight.

3. Use the first person.

Instead of: It is thought Write: I think

Instead of: The samples were analyzed Write: I analyzed the samples

4. Avoid dangling participles.

"After incubating at 30 degrees C, we examined the petri plates." (You must've been pretty warm in there.)

Write succinctly

1. Use verbs instead of abstract nouns

Instead of: take into consideration Write: consider

2. Use strong verbs instead of "to be"

Instead of: The enzyme was found to be the active agent in catalyzing... Write: The enzyme catalyzed...

3. Use short words.

|

Instead of: Write: possess have sufficient enough utilize use demonstrate show assistance help terminate end

4. Use concise terms.

Instead of: Write: prior to before due to the fact that because in a considerable number of cases often the vast majority of most during the time that when in close proximity to near it has long been known that I'm too lazy to look up the reference

5. Use short sentences. A sentence made of more than 40 words should probably be rewritten as two sentences.

"The conjunction 'and' commonly serves to indicate that the writer's mind still functions even when no signs of the phenomenon are noticeable." Rudolf Virchow, 1928

Check your grammar, spelling and punctuation

1. Use a spellchecker, but be aware that they don't catch all mistakes.

"When we consider the animal as a hole,..." Student's paper

2. Your spellchecker may not recognize scientific terms. For the correct spelling, try Biotech's Life Science Dictionary or one of the technical dictionaries on the reference shelf in the Biology or Health Sciences libraries.

3. Don't, use, unnecessary, commas.

4. Proofread carefully to see if you any words out.

USEFUL BOOKS

Victoria E. McMillan, Writing Papers in the Biological Sciences , Bedford Books, Boston, 1997 The best. On sale for about $18 at Labyrinth Books, 112th Street. On reserve in Biology Library

Jan A. Pechenik, A Short Guide to Writing About Biology , Boston: Little, Brown, 1987

Harrison W. Ambrose, III & Katharine Peckham Ambrose, A Handbook of Biological Investigation , 4th edition, Hunter Textbooks Inc, Winston-Salem, 1987 Particularly useful if you need to use statistics to analyze your data. Copy on Reference shelf in Biology Library.

Robert S. Day, How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper , 4th edition, Oryx Press, Phoenix, 1994. Earlier editions also good. A bit more advanced, intended for those writing papers for publication. Fun to read. Several copies available in Columbia libraries.

William Strunk, Jr. and E. B. White, The Elements of Style , 3rd ed. Macmillan, New York, 1987. Several copies available in Columbia libraries. Strunk's first edition is available on-line.

Loading metrics

Open Access

Ten simple rules for structuring papers

Affiliations Optimize Science, Mill Valley, California, United States of America, Janelia Research Campus, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Ashburn, Virginia, United States of America

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, United States of America

- Brett Mensh,

- Konrad Kording

Published: September 28, 2017

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005619

- See the preprint

- Reader Comments

9 Nov 2017: The PLOS Computational Biology Staff (2017) Correction: Ten simple rules for structuring papers. PLOS Computational Biology 13(11): e1005830. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005830 View correction

Citation: Mensh B, Kording K (2017) Ten simple rules for structuring papers. PLoS Comput Biol 13(9): e1005619. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005619

Editor: Scott Markel, Dassault Systemes BIOVIA, UNITED STATES

Copyright: © 2017 Mensh, Kording. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Good scientific writing is essential to career development and to the progress of science. A well-structured manuscript allows readers and reviewers to get excited about the subject matter, to understand and verify the paper’s contributions, and to integrate these contributions into a broader context. However, many scientists struggle with producing high-quality manuscripts and are typically untrained in paper writing. Focusing on how readers consume information, we present a set of ten simple rules to help you communicate the main idea of your paper. These rules are designed to make your paper more influential and the process of writing more efficient and pleasurable.

Introduction

Writing and reading papers are key skills for scientists. Indeed, success at publishing is used to evaluate scientists [ 1 ] and can help predict their future success [ 2 ]. In the production and consumption of papers, multiple parties are involved, each having their own motivations and priorities. The editors want to make sure that the paper is significant, and the reviewers want to determine whether the conclusions are justified by the results. The reader wants to quickly understand the conceptual conclusions of the paper before deciding whether to dig into the details, and the writer wants to convey the important contributions to the broadest audience possible while convincing the specialist that the findings are credible. You can facilitate all of these goals by structuring the paper well at multiple scales—spanning the sentence, paragraph, section, and document.

Clear communication is also crucial for the broader scientific enterprise because “concept transfer” is a rate-limiting step in scientific cross-pollination. This is particularly true in the biological sciences and other fields that comprise a vast web of highly interconnected sub-disciplines. As scientists become increasingly specialized, it becomes more important (and difficult) to strengthen the conceptual links. Communication across disciplinary boundaries can only work when manuscripts are readable, credible, and memorable.

The claim that gives significance to your work has to be supported by data and by a logic that gives it credibility. Without carefully planning the paper’s logic, writers will often be missing data or missing logical steps on the way to the conclusion. While these lapses are beyond our scope, your scientific logic must be crystal clear to powerfully make your claim.

Here we present ten simple rules for structuring papers. The first four rules are principles that apply to all the parts of a paper and further to other forms of communication such as grants and posters. The next four rules deal with the primary goals of each of the main parts of papers. The final two rules deliver guidance on the process—heuristics for efficiently constructing manuscripts.

Principles (Rules 1–4)

Writing is communication. Thus, the reader’s experience is of primary importance, and all writing serves this goal. When you write, you should constantly have your reader in mind. These four rules help you to avoid losing your reader.

Rule 1: Focus your paper on a central contribution, which you communicate in the title

Your communication efforts are successful if readers can still describe the main contribution of your paper to their colleagues a year after reading it. Although it is clear that a paper often needs to communicate a number of innovations on the way to its final message, it does not pay to be greedy. Focus on a single message; papers that simultaneously focus on multiple contributions tend to be less convincing about each and are therefore less memorable.

The most important element of a paper is the title—think of the ratio of the number of titles you read to the number of papers you read. The title is typically the first element a reader encounters, so its quality [ 3 ] determines whether the reader will invest time in reading the abstract.

The title not only transmits the paper’s central contribution but can also serve as a constant reminder (to you) to focus the text on transmitting that idea. Science is, after all, the abstraction of simple principles from complex data. The title is the ultimate refinement of the paper’s contribution. Thinking about the title early—and regularly returning to hone it—can help not only the writing of the paper but also the process of designing experiments or developing theories.

This Rule of One is the most difficult rule to optimally implement because it comes face-to-face with the key challenge of science, which is to make the claim and/or model as simple as the data and logic can support but no simpler. In the end, your struggle to find this balance may appropriately result in “one contribution” that is multifaceted. For example, a technology paper may describe both its new technology and a biological result using it; the bridge that unifies these two facets is a clear description of how the new technology can be used to do new biology.

Rule 2: Write for flesh-and-blood human beings who do not know your work

Because you are the world’s leading expert at exactly what you are doing, you are also the world’s least qualified person to judge your writing from the perspective of the naïve reader. The majority of writing mistakes stem from this predicament. Think like a designer—for each element, determine the impact that you want to have on people and then strive to achieve that objective [ 4 ]. Try to think through the paper like a naïve reader who must first be made to care about the problem you are addressing (see Rule 6) and then will want to understand your answer with minimal effort.

Define technical terms clearly because readers can become frustrated when they encounter a word that they don’t understand. Avoid abbreviations and acronyms so that readers do not have to go back to earlier sections to identify them.

The vast knowledge base of human psychology is useful in paper writing. For example, people have working memory constraints in that they can only remember a small number of items and are better at remembering the beginning and the end of a list than the middle [ 5 ]. Do your best to minimize the number of loose threads that the reader has to keep in mind at any one time.

Rule 3: Stick to the context-content-conclusion (C-C-C) scheme

The vast majority of popular (i.e., memorable and re-tellable) stories have a structure with a discernible beginning, a well-defined body, and an end. The beginning sets up the context for the story, while the body (content) advances the story towards an ending in which the problems find their conclusions. This structure reduces the chance that the reader will wonder “Why was I told that?” (if the context is missing) or “So what?” (if the conclusion is missing).

There are many ways of telling a story. Mostly, they differ in how well they serve a patient reader versus an impatient one [ 6 ]. The impatient reader needs to be engaged quickly; this can be accomplished by presenting the most exciting content first (e.g., as seen in news articles). The C-C-C scheme that we advocate serves a more patient reader who is willing to spend the time to get oriented with the context. A consequent disadvantage of C-C-C is that it may not optimally engage the impatient reader. This disadvantage is mitigated by the fact that the structure of scientific articles, specifically the primacy of the title and abstract, already forces the content to be revealed quickly. Thus, a reader who proceeds to the introduction is likely engaged enough to have the patience to absorb the context. Furthermore, one hazard of excessive “content first” story structures in science is that you may generate skepticism in the reader because they may be missing an important piece of context that makes your claim more credible. For these reasons, we advocate C-C-C as a “default” scientific story structure.

The C-C-C scheme defines the structure of the paper on multiple scales. At the whole-paper scale, the introduction sets the context, the results are the content, and the discussion brings home the conclusion. Applying C-C-C at the paragraph scale, the first sentence defines the topic or context, the body hosts the novel content put forth for the reader’s consideration, and the last sentence provides the conclusion to be remembered.

Deviating from the C-C-C structure often leads to papers that are hard to read, but writers often do so because of their own autobiographical context. During our everyday lives as scientists, we spend a majority of our time producing content and a minority amidst a flurry of other activities. We run experiments, develop the exposition of available literature, and combine thoughts using the magic of human cognition. It is natural to want to record these efforts on paper and structure a paper chronologically. But for our readers, most details of our activities are extraneous. They do not care about the chronological path by which you reached a result; they just care about the ultimate claim and the logic supporting it (see Rule 7). Thus, all our work must be reformatted to provide a context that makes our material meaningful and a conclusion that helps the reader to understand and remember it.

Rule 4: Optimize your logical flow by avoiding zig-zag and using parallelism

Avoiding zig-zag..

Only the central idea of the paper should be touched upon multiple times. Otherwise, each subject should be covered in only one place in order to minimize the number of subject changes. Related sentences or paragraphs should be strung together rather than interrupted by unrelated material. Ideas that are similar, such as two reasons why we should believe something, should come one immediately after the other.

Using parallelism.

Similarly, across consecutive paragraphs or sentences, parallel messages should be communicated with parallel form. Parallelism makes it easier to read the text because the reader is familiar with the structure. For example, if we have three independent reasons why we prefer one interpretation of a result over another, it is helpful to communicate them with the same syntax so that this syntax becomes transparent to the reader, which allows them to focus on the content. There is nothing wrong with using the same word multiple times in a sentence or paragraph. Resist the temptation to use a different word to refer to the same concept—doing so makes readers wonder if the second word has a slightly different meaning.

The components of a paper (Rules 5–8)

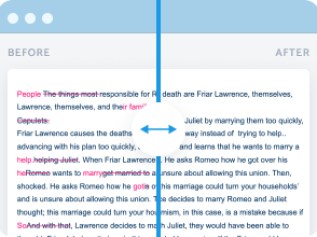

The individual parts of a paper—abstract, introduction, results, and discussion—have different objectives, and thus they each apply the C-C-C structure a little differently in order to achieve their objectives. We will discuss these specialized structures in this section and summarize them in Fig 1 .

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Note that the abstract is special in that it contains all three elements (Context, Content, and Conclusion), thus comprising all three colors.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005619.g001

Rule 5: Tell a complete story in the abstract

The abstract is, for most readers, the only part of the paper that will be read. This means that the abstract must convey the entire message of the paper effectively. To serve this purpose, the abstract’s structure is highly conserved. Each of the C-C-C elements is detailed below.

The context must communicate to the reader what gap the paper will fill. The first sentence orients the reader by introducing the broader field in which the particular research is situated. Then, this context is narrowed until it lands on the open question that the research answered. A successful context section sets the stage for distinguishing the paper’s contributions from the current state of the art by communicating what is missing in the literature (i.e., the specific gap) and why that matters (i.e., the connection between the specific gap and the broader context that the paper opened with).

The content (“Here we”) first describes the novel method or approach that you used to fill the gap or question. Then you present the meat—your executive summary of the results.

Finally, the conclusion interprets the results to answer the question that was posed at the end of the context section. There is often a second part to the conclusion section that highlights how this conclusion moves the broader field forward (i.e., “broader significance”). This is particularly true for more “general” journals with a broad readership.

This structure helps you avoid the most common mistake with the abstract, which is to talk about results before the reader is ready to understand them. Good abstracts usually take many iterations of refinement to make sure the results fill the gap like a key fits its lock. The broad-narrow-broad structure allows you to communicate with a wider readership (through breadth) while maintaining the credibility of your claim (which is always based on a finite or narrow set of results).

Rule 6: Communicate why the paper matters in the introduction

The introduction highlights the gap that exists in current knowledge or methods and why it is important. This is usually done by a set of progressively more specific paragraphs that culminate in a clear exposition of what is lacking in the literature, followed by a paragraph summarizing what the paper does to fill that gap.

As an example of the progression of gaps, a first paragraph may explain why understanding cell differentiation is an important topic and that the field has not yet solved what triggers it (a field gap). A second paragraph may explain what is unknown about the differentiation of a specific cell type, such as astrocytes (a subfield gap). A third may provide clues that a particular gene might drive astrocytic differentiation and then state that this hypothesis is untested (the gap within the subfield that you will fill). The gap statement sets the reader’s expectation for what the paper will deliver.

The structure of each introduction paragraph (except the last) serves the goal of developing the gap. Each paragraph first orients the reader to the topic (a context sentence or two) and then explains the “knowns” in the relevant literature (content) before landing on the critical “unknown” (conclusion) that makes the paper matter at the relevant scale. Along the path, there are often clues given about the mystery behind the gaps; these clues lead to the untested hypothesis or undeveloped method of the paper and give the reader hope that the mystery is solvable. The introduction should not contain a broad literature review beyond the motivation of the paper. This gap-focused structure makes it easy for experienced readers to evaluate the potential importance of a paper—they only need to assess the importance of the claimed gap.

The last paragraph of the introduction is special: it compactly summarizes the results, which fill the gap you just established. It differs from the abstract in the following ways: it does not need to present the context (which has just been given), it is somewhat more specific about the results, and it only briefly previews the conclusion of the paper, if at all.

Rule 7: Deliver the results as a sequence of statements, supported by figures, that connect logically to support the central contribution

The results section needs to convince the reader that the central claim is supported by data and logic. Every scientific argument has its own particular logical structure, which dictates the sequence in which its elements should be presented.

For example, a paper may set up a hypothesis, verify that a method for measurement is valid in the system under study, and then use the measurement to disprove the hypothesis. Alternatively, a paper may set up multiple alternative (and mutually exclusive) hypotheses and then disprove all but one to provide evidence for the remaining interpretation. The fabric of the argument will contain controls and methods where they are needed for the overall logic.

In the outlining phase of paper preparation (see Rule 9), sketch out the logical structure of how your results support your claim and convert this into a sequence of declarative statements that become the headers of subsections within the results section (and/or the titles of figures). Most journals allow this type of formatting, but if your chosen journal does not, these headers are still useful during the writing phase and can either be adapted to serve as introductory sentences to your paragraphs or deleted before submission. Such a clear progression of logical steps makes the paper easy to follow.

Figures, their titles, and legends are particularly important because they show the most objective support (data) of the steps that culminate in the paper’s claim. Moreover, figures are often viewed by readers who skip directly from the abstract in order to save time. Thus, the title of the figure should communicate the conclusion of the analysis, and the legend should explain how it was done. Figure making is an art unto itself; the Edward Tufte books remain the gold standard for learning this craft [ 7 , 8 ].

The first results paragraph is special in that it typically summarizes the overall approach to the problem outlined in the introduction, along with any key innovative methods that were developed. Most readers do not read the methods, so this paragraph gives them the gist of the methods that were used.

Each subsequent paragraph in the results section starts with a sentence or two that set up the question that the paragraph answers, such as the following: “To verify that there are no artifacts…,” “What is the test-retest reliability of our measure?,” or “We next tested whether Ca 2+ flux through L-type Ca 2+ channels was involved.” The middle of the paragraph presents data and logic that pertain to the question, and the paragraph ends with a sentence that answers the question. For example, it may conclude that none of the potential artifacts were detected. This structure makes it easy for experienced readers to fact-check a paper. Each paragraph convinces the reader of the answer given in its last sentence. This makes it easy to find the paragraph in which a suspicious conclusion is drawn and to check the logic of that paragraph. The result of each paragraph is a logical statement, and paragraphs farther down in the text rely on the logical conclusions of previous paragraphs, much as theorems are built in mathematical literature.

Rule 8: Discuss how the gap was filled, the limitations of the interpretation, and the relevance to the field

The discussion section explains how the results have filled the gap that was identified in the introduction, provides caveats to the interpretation, and describes how the paper advances the field by providing new opportunities. This is typically done by recapitulating the results, discussing the limitations, and then revealing how the central contribution may catalyze future progress. The first discussion paragraph is special in that it generally summarizes the important findings from the results section. Some readers skip over substantial parts of the results, so this paragraph at least gives them the gist of that section.

Each of the following paragraphs in the discussion section starts by describing an area of weakness or strength of the paper. It then evaluates the strength or weakness by linking it to the relevant literature. Discussion paragraphs often conclude by describing a clever, informal way of perceiving the contribution or by discussing future directions that can extend the contribution.

For example, the first paragraph may summarize the results, focusing on their meaning. The second through fourth paragraphs may deal with potential weaknesses and with how the literature alleviates concerns or how future experiments can deal with these weaknesses. The fifth paragraph may then culminate in a description of how the paper moves the field forward. Step by step, the reader thus learns to put the paper’s conclusions into the right context.

Process (Rules 9 and 10)

To produce a good paper, authors can use helpful processes and habits. Some aspects of a paper affect its impact more than others, which suggests that your investment of time should be weighted towards the issues that matter most. Moreover, iteratively using feedback from colleagues allows authors to improve the story at all levels to produce a powerful manuscript. Choosing the right process makes writing papers easier and more effective.

Rule 9: Allocate time where it matters: Title, abstract, figures, and outlining

The central logic that underlies a scientific claim is paramount. It is also the bridge that connects the experimental phase of a research effort with the paper-writing phase. Thus, it is useful to formalize the logic of ongoing experimental efforts (e.g., during lab meetings) into an evolving document of some sort that will ultimately steer the outline of the paper.

You should also allocate your time according to the importance of each section. The title, abstract, and figures are viewed by far more people than the rest of the paper, and the methods section is read least of all. Budget accordingly.

The time that we do spend on each section can be used efficiently by planning text before producing it. Make an outline. We like to write one informal sentence for each planned paragraph. It is often useful to start the process around descriptions of each result—these may become the section headers in the results section. Because the story has an overall arc, each paragraph should have a defined role in advancing this story. This role is best scrutinized at the outline stage in order to reduce wasting time on wordsmithing paragraphs that don’t end up fitting within the overall story.

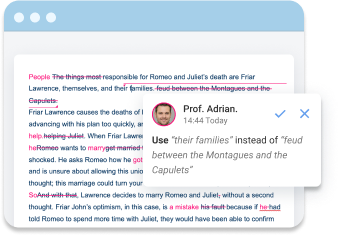

Rule 10: Get feedback to reduce, reuse, and recycle the story

Writing can be considered an optimization problem in which you simultaneously improve the story, the outline, and all the component sentences. In this context, it is important not to get too attached to one’s writing. In many cases, trashing entire paragraphs and rewriting is a faster way to produce good text than incremental editing.

There are multiple signs that further work is necessary on a manuscript (see Table 1 ). For example, if you, as the writer, cannot describe the entire outline of a paper to a colleague in a few minutes, then clearly a reader will not be able to. You need to further distill your story. Finding such violations of good writing helps to improve the paper at all levels.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005619.t001

Successfully writing a paper typically requires input from multiple people. Test readers are necessary to make sure that the overall story works. They can also give valuable input on where the story appears to move too quickly or too slowly. They can clarify when it is best to go back to the drawing board and retell the entire story. Reviewers are also extremely useful. Non-specific feedback and unenthusiastic reviews often imply that the reviewers did not “get” the big picture story line. Very specific feedback usually points out places where the logic within a paragraph was not sufficient. It is vital to accept this feedback in a positive way. Because input from others is essential, a network of helpful colleagues is fundamental to making a story memorable. To keep this network working, make sure to pay back your colleagues by reading their manuscripts.

This paper focused on the structure, or “anatomy,” of manuscripts. We had to gloss over many finer points of writing, including word choice and grammar, the creative process, and collaboration. A paper about writing can never be complete; as such, there is a large body of literature dealing with issues of scientific writing [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ].

Personal style often leads writers to deviate from a rigid, conserved structure, and it can be a delight to read a paper that creatively bends the rules. However, as with many other things in life, a thorough mastery of the standard rules is necessary to successfully bend them [ 18 ]. In following these guidelines, scientists will be able to address a broad audience, bridge disciplines, and more effectively enable integrative science.

Acknowledgments

We took our own advice and sought feedback from a large number of colleagues throughout the process of preparing this paper. We would like to especially thank the following people who gave particularly detailed and useful feedback:

Sandra Aamodt, Misha Ahrens, Vanessa Bender, Erik Bloss, Davi Bock, Shelly Buffington, Xing Chen, Frances Cho, Gabrielle Edgerton, multiple generations of the COSMO summer school, Jason Perry, Jermyn See, Nelson Spruston, David Stern, Alice Ting, Joshua Vogelstein, Ronald Weber.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 4. Carter M (2012) Designing Science Presentations: A Visual Guide to Figures, Papers, Slides, Posters, and More: Academic Press.

- 6. Schimel J (2012) Writing science: how to write papers that get cited and proposals that get funded. USA: OUP.

- 7. Tufte ER (1990) Envisioning information. Graphics Press.

- 8. Tufte ER The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Graphics Press.

- 9. Lisberger SG (2011) From Science to Citation: How to Publish a Successful Scientific Paper. Stephen Lisberger.

- 10. Simons D (2012) Dan's writing and revising guide. http://www.dansimons.com/resources/Simons_on_writing.pdf [cited 2017 Sep 9].

- 11. Sørensen C (1994) This is Not an Article—Just Some Thoughts on How to Write One. Syöte, Finland: Oulu University, 46–59.

- 12. Day R (1988) How to write and publish a scientific paper. Phoenix: Oryx.

- 13. Lester JD, Lester J (1967) Writing research papers. Scott, Foresman.

- 14. Dumont J-L (2009) Trees, Maps, and Theorems. Principiae. http://www.treesmapsandtheorems.com/ [cited 2017 Sep 9].

- 15. Pinker S (2014) The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century. Viking Adult.

- 18. Strunk W (2007) The elements of style. Penguin.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Academic writing

- How to write a lab report

How To Write A Lab Report | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Published on May 20, 2021 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on July 23, 2023.

A lab report conveys the aim, methods, results, and conclusions of a scientific experiment. The main purpose of a lab report is to demonstrate your understanding of the scientific method by performing and evaluating a hands-on lab experiment. This type of assignment is usually shorter than a research paper .

Lab reports are commonly used in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. This article focuses on how to structure and write a lab report.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Structuring a lab report, introduction, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about lab reports.

The sections of a lab report can vary between scientific fields and course requirements, but they usually contain the purpose, methods, and findings of a lab experiment .

Each section of a lab report has its own purpose.

- Title: expresses the topic of your study

- Abstract : summarizes your research aims, methods, results, and conclusions

- Introduction: establishes the context needed to understand the topic

- Method: describes the materials and procedures used in the experiment

- Results: reports all descriptive and inferential statistical analyses

- Discussion: interprets and evaluates results and identifies limitations

- Conclusion: sums up the main findings of your experiment

- References: list of all sources cited using a specific style (e.g. APA )

- Appendices : contains lengthy materials, procedures, tables or figures

Although most lab reports contain these sections, some sections can be omitted or combined with others. For example, some lab reports contain a brief section on research aims instead of an introduction, and a separate conclusion is not always required.

If you’re not sure, it’s best to check your lab report requirements with your instructor.

Check for common mistakes

Use the best grammar checker available to check for common mistakes in your text.

Fix mistakes for free

Your title provides the first impression of your lab report – effective titles communicate the topic and/or the findings of your study in specific terms.

Create a title that directly conveys the main focus or purpose of your study. It doesn’t need to be creative or thought-provoking, but it should be informative.

- The effects of varying nitrogen levels on tomato plant height.

- Testing the universality of the McGurk effect.

- Comparing the viscosity of common liquids found in kitchens.

An abstract condenses a lab report into a brief overview of about 150–300 words. It should provide readers with a compact version of the research aims, the methods and materials used, the main results, and the final conclusion.

Think of it as a way of giving readers a preview of your full lab report. Write the abstract last, in the past tense, after you’ve drafted all the other sections of your report, so you’ll be able to succinctly summarize each section.

To write a lab report abstract, use these guiding questions:

- What is the wider context of your study?

- What research question were you trying to answer?

- How did you perform the experiment?

- What did your results show?

- How did you interpret your results?

- What is the importance of your findings?

Nitrogen is a necessary nutrient for high quality plants. Tomatoes, one of the most consumed fruits worldwide, rely on nitrogen for healthy leaves and stems to grow fruit. This experiment tested whether nitrogen levels affected tomato plant height in a controlled setting. It was expected that higher levels of nitrogen fertilizer would yield taller tomato plants.

Levels of nitrogen fertilizer were varied between three groups of tomato plants. The control group did not receive any nitrogen fertilizer, while one experimental group received low levels of nitrogen fertilizer, and a second experimental group received high levels of nitrogen fertilizer. All plants were grown from seeds, and heights were measured 50 days into the experiment.

The effects of nitrogen levels on plant height were tested between groups using an ANOVA. The plants with the highest level of nitrogen fertilizer were the tallest, while the plants with low levels of nitrogen exceeded the control group plants in height. In line with expectations and previous findings, the effects of nitrogen levels on plant height were statistically significant. This study strengthens the importance of nitrogen for tomato plants.

Your lab report introduction should set the scene for your experiment. One way to write your introduction is with a funnel (an inverted triangle) structure:

- Start with the broad, general research topic

- Narrow your topic down your specific study focus

- End with a clear research question

Begin by providing background information on your research topic and explaining why it’s important in a broad real-world or theoretical context. Describe relevant previous research on your topic and note how your study may confirm it or expand it, or fill a gap in the research field.

This lab experiment builds on previous research from Haque, Paul, and Sarker (2011), who demonstrated that tomato plant yield increased at higher levels of nitrogen. However, the present research focuses on plant height as a growth indicator and uses a lab-controlled setting instead.

Next, go into detail on the theoretical basis for your study and describe any directly relevant laws or equations that you’ll be using. State your main research aims and expectations by outlining your hypotheses .

Based on the importance of nitrogen for tomato plants, the primary hypothesis was that the plants with the high levels of nitrogen would grow the tallest. The secondary hypothesis was that plants with low levels of nitrogen would grow taller than plants with no nitrogen.

Your introduction doesn’t need to be long, but you may need to organize it into a few paragraphs or with subheadings such as “Research Context” or “Research Aims.”

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

A lab report Method section details the steps you took to gather and analyze data. Give enough detail so that others can follow or evaluate your procedures. Write this section in the past tense. If you need to include any long lists of procedural steps or materials, place them in the Appendices section but refer to them in the text here.

You should describe your experimental design, your subjects, materials, and specific procedures used for data collection and analysis.

Experimental design

Briefly note whether your experiment is a within-subjects or between-subjects design, and describe how your sample units were assigned to conditions if relevant.

A between-subjects design with three groups of tomato plants was used. The control group did not receive any nitrogen fertilizer. The first experimental group received a low level of nitrogen fertilizer, while the second experimental group received a high level of nitrogen fertilizer.

Describe human subjects in terms of demographic characteristics, and animal or plant subjects in terms of genetic background. Note the total number of subjects as well as the number of subjects per condition or per group. You should also state how you recruited subjects for your study.

List the equipment or materials you used to gather data and state the model names for any specialized equipment.

List of materials

35 Tomato seeds

15 plant pots (15 cm tall)

Light lamps (50,000 lux)

Nitrogen fertilizer

Measuring tape

Describe your experimental settings and conditions in detail. You can provide labelled diagrams or images of the exact set-up necessary for experimental equipment. State how extraneous variables were controlled through restriction or by fixing them at a certain level (e.g., keeping the lab at room temperature).

Light levels were fixed throughout the experiment, and the plants were exposed to 12 hours of light a day. Temperature was restricted to between 23 and 25℃. The pH and carbon levels of the soil were also held constant throughout the experiment as these variables could influence plant height. The plants were grown in rooms free of insects or other pests, and they were spaced out adequately.

Your experimental procedure should describe the exact steps you took to gather data in chronological order. You’ll need to provide enough information so that someone else can replicate your procedure, but you should also be concise. Place detailed information in the appendices where appropriate.

In a lab experiment, you’ll often closely follow a lab manual to gather data. Some instructors will allow you to simply reference the manual and state whether you changed any steps based on practical considerations. Other instructors may want you to rewrite the lab manual procedures as complete sentences in coherent paragraphs, while noting any changes to the steps that you applied in practice.

If you’re performing extensive data analysis, be sure to state your planned analysis methods as well. This includes the types of tests you’ll perform and any programs or software you’ll use for calculations (if relevant).

First, tomato seeds were sown in wooden flats containing soil about 2 cm below the surface. Each seed was kept 3-5 cm apart. The flats were covered to keep the soil moist until germination. The seedlings were removed and transplanted to pots 8 days later, with a maximum of 2 plants to a pot. Each pot was watered once a day to keep the soil moist.

The nitrogen fertilizer treatment was applied to the plant pots 12 days after transplantation. The control group received no treatment, while the first experimental group received a low concentration, and the second experimental group received a high concentration. There were 5 pots in each group, and each plant pot was labelled to indicate the group the plants belonged to.

50 days after the start of the experiment, plant height was measured for all plants. A measuring tape was used to record the length of the plant from ground level to the top of the tallest leaf.

In your results section, you should report the results of any statistical analysis procedures that you undertook. You should clearly state how the results of statistical tests support or refute your initial hypotheses.

The main results to report include:

- any descriptive statistics

- statistical test results

- the significance of the test results

- estimates of standard error or confidence intervals

The mean heights of the plants in the control group, low nitrogen group, and high nitrogen groups were 20.3, 25.1, and 29.6 cm respectively. A one-way ANOVA was applied to calculate the effect of nitrogen fertilizer level on plant height. The results demonstrated statistically significant ( p = .03) height differences between groups.

Next, post-hoc tests were performed to assess the primary and secondary hypotheses. In support of the primary hypothesis, the high nitrogen group plants were significantly taller than the low nitrogen group and the control group plants. Similarly, the results supported the secondary hypothesis: the low nitrogen plants were taller than the control group plants.

These results can be reported in the text or in tables and figures. Use text for highlighting a few key results, but present large sets of numbers in tables, or show relationships between variables with graphs.

You should also include sample calculations in the Results section for complex experiments. For each sample calculation, provide a brief description of what it does and use clear symbols. Present your raw data in the Appendices section and refer to it to highlight any outliers or trends.

The Discussion section will help demonstrate your understanding of the experimental process and your critical thinking skills.

In this section, you can:

- Interpret your results

- Compare your findings with your expectations

- Identify any sources of experimental error

- Explain any unexpected results

- Suggest possible improvements for further studies

Interpreting your results involves clarifying how your results help you answer your main research question. Report whether your results support your hypotheses.

- Did you measure what you sought out to measure?

- Were your analysis procedures appropriate for this type of data?

Compare your findings with other research and explain any key differences in findings.

- Are your results in line with those from previous studies or your classmates’ results? Why or why not?

An effective Discussion section will also highlight the strengths and limitations of a study.

- Did you have high internal validity or reliability?

- How did you establish these aspects of your study?

When describing limitations, use specific examples. For example, if random error contributed substantially to the measurements in your study, state the particular sources of error (e.g., imprecise apparatus) and explain ways to improve them.

The results support the hypothesis that nitrogen levels affect plant height, with increasing levels producing taller plants. These statistically significant results are taken together with previous research to support the importance of nitrogen as a nutrient for tomato plant growth.

However, unlike previous studies, this study focused on plant height as an indicator of plant growth in the present experiment. Importantly, plant height may not always reflect plant health or fruit yield, so measuring other indicators would have strengthened the study findings.

Another limitation of the study is the plant height measurement technique, as the measuring tape was not suitable for plants with extreme curvature. Future studies may focus on measuring plant height in different ways.

The main strengths of this study were the controls for extraneous variables, such as pH and carbon levels of the soil. All other factors that could affect plant height were tightly controlled to isolate the effects of nitrogen levels, resulting in high internal validity for this study.

Your conclusion should be the final section of your lab report. Here, you’ll summarize the findings of your experiment, with a brief overview of the strengths and limitations, and implications of your study for further research.

Some lab reports may omit a Conclusion section because it overlaps with the Discussion section, but you should check with your instructor before doing so.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

A lab report conveys the aim, methods, results, and conclusions of a scientific experiment . Lab reports are commonly assigned in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields.

The purpose of a lab report is to demonstrate your understanding of the scientific method with a hands-on lab experiment. Course instructors will often provide you with an experimental design and procedure. Your task is to write up how you actually performed the experiment and evaluate the outcome.

In contrast, a research paper requires you to independently develop an original argument. It involves more in-depth research and interpretation of sources and data.

A lab report is usually shorter than a research paper.

The sections of a lab report can vary between scientific fields and course requirements, but it usually contains the following:

- Abstract: summarizes your research aims, methods, results, and conclusions

- References: list of all sources cited using a specific style (e.g. APA)

- Appendices: contains lengthy materials, procedures, tables or figures

The results chapter or section simply and objectively reports what you found, without speculating on why you found these results. The discussion interprets the meaning of the results, puts them in context, and explains why they matter.

In qualitative research , results and discussion are sometimes combined. But in quantitative research , it’s considered important to separate the objective results from your interpretation of them.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, July 23). How To Write A Lab Report | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved September 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-writing/lab-report/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, guide to experimental design | overview, steps, & examples, how to write an apa methods section, how to write an apa results section, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

BIOLOGY JUNCTION

Test And Quizzes for Biology, Pre-AP, Or AP Biology For Teachers And Students

A Step-By-Step Guide on Writing a Biology Research Paper

For many students, writing a biology research paper can seem like a daunting task. They want to come up with the best possible report, but they don’t realize that planning the entire writing process can improve the quality of their work and save them time while writing. In this article, you’ll learn how to find a good topic, outline your paper, use statistical tests, and avoid using hedge words.

Finding a good topic

The first step in writing a well-constructed biology research paper is choosing a topic. There are a variety of topics to choose from within the biological field. Choose one that interests you and captures your attention. A compelling topic motivates you to work hard and produce a high-quality paper.

While choosing a topic, keep in mind that biology research is time-consuming and requires extensive research. For this reason, choosing a topic that piques the interest of the reader is crucial. In addition to this, you should choose a topic that is appropriate for the type of biology paper you need to write. After all, you do not want to bore the reader with an inane paper.

A good biology research paper topic should be well-supported by solid scientific evidence. Select a topic only after thorough research, and be sure to include steps and references from reliable sources. A biological research paper topic can be an interesting journey into the world of nature. You could choose to research the effects of stress on the human body or investigate the biological mechanisms of the human reproductive system.

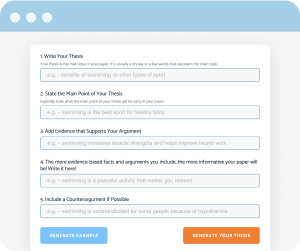

Outlining your paper

The first step in drafting a biological research paper is to create an outline. This is meant to be a roadmap that helps you understand and visualize the subject. An outline can help you avoid common writing mistakes and shape your paper into a serious piece of work. The next step is to gather information about the subject that will support your main idea.

Once you have a topic, you can start writing your outline. Outlines should include at least one idea, a brief introduction, and a conclusion. The introduction, ideas, and conclusion should be numbered in the order you plan to present your information. The main ideas are generally a collection of facts and figures. For example, in a literature review, these points might be chapters from a book, a series of dates from history, or the methods and results of a scientific paper.

When writing a biological research paper, you should use scholarly sources. While there is a lot of misinformation on the internet, it’s best to stick to academic essay writing service to get the most accurate information. Most libraries allow you to select a peer-review filter that will restrict your search results to academic journals. It’s also helpful to be familiar with the differences between scholarly and popular sources.

Using statistical tests

Using statistical tests when writing a biological paper requires that you make certain assumptions about the results you are describing. The most common statistical tests are parametric tests that are based on assumptions about conditions or parameters. About 22% of the papers in our review reported violations of these assumptions, and such violations can lead to inappropriate or invalid conclusions.

Statistical tests are important in biological research because they allow researchers to determine if their data is statistically significant or not. The power of these tests depends on the size of the dataset. Larger datasets produce more significant results. The power of these tests also depends on the assumption of independence between measurements. This is important because the results can be different if there are duplications or different levels of replications.

Hypothesis tests are useful in evaluating experimental data. They identify differences and patterns in data. They are useful tools for structuring biological research.

Avoiding hedge words

Hedge words are phrases or words used to express uncertainty in a scientific paper. They can help writers avoid making inaccurate claims while still being respectful of the reader’s opinion. However, writers must be careful to avoid using too many hedges.

Listed below are a few guidelines to help you avoid these words:

- Hedge words shift the burden of responsibility from the writer to the reader.

- Hedge words can be a sign of uncertainty or overstatement. They can also be used to limit the scope of an assertion. They also convey an opinion or hypothesis. When choosing a hedging strategy, be careful not to use words such as “no data” or “unreliable.” These words can convey a degree of uncertainty and imply that the findings cannot be confirmed.

The use of hedge words is common in academic writing. However, they hurt your audience. It is a linguistic strategy that writers use as a way to reassure readers. The goal is to guide readers and make them feel comfortable with the idea that the author does not know all the answers.

Choosing a format

Biological research papers have different formats, and you should choose one that suits the nature of your paper. It should be based on credible and peer-reviewed sources. The best sources to use for biology papers are books, specialized journals, and databases. Avoid personal blogs, social networks, and internet discussions, as these are not suitable for a research paper.

Biology research papers focus on a specific issue and present different arguments in support of a thesis. Traditionally, they are based on peer-reviewed sources, but you can also conduct your independent research and present unique findings. Biology is a complex field of study. The subject matter varies, from the basic structure of living things to the functions of different organs. It also explores the process of evolution and the life span of different species.

Formatting your bibliography

When writing a biological research paper, the format of your bibliography is crucial. It should follow a standardized citation style such as the “Author, Date” scientific style. The format should be arranged alphabetically by author, and you should use numbered references to indicate key sources.

Reference lists must be comprehensive and contain enough information to enable readers to find the sources themselves. Although the format is not as important as completeness, it can help readers quickly identify the authors and sources. Bibliographies are usually reverse-indented to make them easier to find.

In-text citations should include the author’s last name, preferred name, and the page number. Usually, authors do not separate their surname and year of publication. In addition, you should also include the location, which is usually the publisher’s office.

If a work has more than four authors, you should list up to ten in the reference list. The first author’s surname should be used, followed by “et al.” Likewise, you should list more than ten authors in the reference list.

When writing a biological research paper, it is important to ensure that your bibliography is formatted properly. When you write the title, you should use boldface and uppercase letters. The title should also be focused, not too long or too short. It should take one or two lines and all text should be double-spaced. You should also type the author’s name after the title. Don’t forget to indicate the location of your research as well as the date you submitted the paper.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

How to write your first research paper

Affiliation.

- 1 Graduate Writing Center, Yale Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 21966034

- PMCID: PMC3178846

Writing a research manuscript is an intimidating process for many novice writers in the sciences. One of the stumbling blocks is the beginning of the process and creating the first draft. This paper presents guidelines on how to initiate the writing process and draft each section of a research manuscript. The paper discusses seven rules that allow the writer to prepare a well-structured and comprehensive manuscript for a publication submission. In addition, the author lists different strategies for successful revision. Each of those strategies represents a step in the revision process and should help the writer improve the quality of the manuscript. The paper could be considered a brief manual for publication.

Keywords: revision; scientific paper; writing process.

Copyright © 2011.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- [How to write a scientific paper]. Parati G, Valentini M. Parati G, et al. Ital Heart J Suppl. 2005 Apr;6(4):189-96. Ital Heart J Suppl. 2005. PMID: 15902941 Italian.

- Writing for publication Part II--The writing process. Clarke LK. Clarke LK. ORL Head Neck Nurs. 1999 Spring;17(2):23-4. ORL Head Neck Nurs. 1999. PMID: 10690126

- Time-saving tips for preparing your manuscript: strategies for acceptance on the first attempt! Hotter AN. Hotter AN. Nurse Author Ed. 1998 Winter;8(1):1-3. Nurse Author Ed. 1998. PMID: 9582785

- Journal Publishing: A Review of the Basics. Kennedy MS. Kennedy MS. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2018 Nov;34(4):361-371. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2018.09.004. Epub 2018 Sep 25. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2018. PMID: 30266551 Review.

- Approach to manuscript preparation and submission: how to get your paper accepted. Kern MJ, Bonneau HN. Kern MJ, et al. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2003 Mar;58(3):391-6. doi: 10.1002/ccd.10442. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2003. PMID: 12594709 Review. No abstract available.

- Systematic review of conceptual criticisms of homeopathy. Schulz VM, Ücker A, Scherr C, Tournier A, Jäger T, Baumgartner S. Schulz VM, et al. Heliyon. 2023 Oct 21;9(11):e21287. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21287. eCollection 2023 Nov. Heliyon. 2023. PMID: 38074879 Free PMC article.

- ChatGPT in academic writing: Maximizing its benefits and minimizing the risks. Mondal H, Mondal S. Mondal H, et al. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2023 Dec 1;71(12):3600-3606. doi: 10.4103/IJO.IJO_718_23. Epub 2023 Nov 20. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2023. PMID: 37991290 Free PMC article. Review.

- Development of a Scientific Writing Course to Increase Fellow Scholarship. Moore AL, Chaisson NF. Moore AL, et al. ATS Sch. 2022 Sep 30;3(3):390-398. doi: 10.34197/ats-scholar.2022-0023PS. eCollection 2022 Oct. ATS Sch. 2022. PMID: 36312809 Free PMC article.

- Why Do Manuscripts Get Rejected? A Content Analysis of Rejection Reports from the Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine. Menon V, Varadharajan N, Praharaj SK, Ameen S. Menon V, et al. Indian J Psychol Med. 2022 Jan;44(1):59-65. doi: 10.1177/0253717620965845. Epub 2020 Nov 11. Indian J Psychol Med. 2022. PMID: 35509668 Free PMC article.

- What Constitutes Authorship in the Social Sciences? Pruschak G. Pruschak G. Front Res Metr Anal. 2021 Mar 23;6:655350. doi: 10.3389/frma.2021.655350. eCollection 2021. Front Res Metr Anal. 2021. PMID: 33870072 Free PMC article.

- Hayes JR. In: The Science of Writing: Theories, Methods, Individual Differences, and Applications. Levy CM, Ransdell SE, editors. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1996. A new framework for understanding cognition and affect in writing; pp. 1–28.

- Silvia PJ. How to Write a Lot. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007.

- Whitesides GM. Whitesides’ Group: Writing a Paper. Adv Mater. 2004;16(15):1375–1377.

- Soto D, Funes MJ, Guzmán-García A, Warbrick T, Rotshtein T, Humphreys GW. Pleasant music overcomes the loss of awareness in patients with visual neglect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(14):6011–6016. - PMC - PubMed

- Hofmann AH. Scientific Writing and Communication. Papers, Proposals, and Presentations. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010.

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Europe PubMed Central

- PubMed Central

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Biology Research: Getting Started: Writing & Citing

- Grant Proposals

- Research Design/Methods

- Finding Articles

- Writing & Citing

- Research Tips

- Background Information

Writing/Publishing

Links to Writing and Style Guides

- APA Style and Grammar Guidelines This comprehensive site from the American Psychological Association offers advice on topics that include paper formatting, in-text citations, references, and bias-free language.

- Ecological Society of America Style format for the journals Ecology, Ecological Applications, Ecological Monographs

Other Resources

- Conducting and Writing a Literature Review How to find and put together background information on your topic

- Guidelines for Effective Professional and Academic Writing A concise guide from the University of Florida/Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

- How to Write Scientific Reports A comprehensive guide from the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill's Writing Center

- Materials and Methods An example of how to write up what was done and how it was done in your research.

- Poster and Presentation Resources Advice on presenting academic research and an extensive list of poster resources

- Writing in the Disciplines: Biology Examples of citing your sources from the University of Richmond Writing Center, from Bates College Department of Biology.

Selected Literature Review Books

Health and Sciences Librarian

Literature Review Tutorial

- Literature Reviews: An Overview for Graduate Students What is a literature review? What purpose does it serve in research? What should you expect when writing one? This tutorial from North Carolina State University answers these questions.

Creating Your Bibliography

- RefWorks Bibliographic management tools, such as RefWorks, allow you to organize and manage citations for your bibliography, and work with Microsoft Word to allow insertion of citations as you write a paper.

- RefWorks Information See the RefWorks for Biology page for more information.

- << Previous: Finding Articles

- Next: RefWorks >>

- Last Updated: Aug 25, 2024 7:42 PM

- URL: https://libguides.jsu.edu/bioresearch

Writing an Introduction for a Scientific Paper

Dr. michelle harris, dr. janet batzli, biocore.

This section provides guidelines on how to construct a solid introduction to a scientific paper including background information, study question , biological rationale, hypothesis , and general approach . If the Introduction is done well, there should be no question in the reader’s mind why and on what basis you have posed a specific hypothesis.

Broad Question : based on an initial observation (e.g., “I see a lot of guppies close to the shore. Do guppies like living in shallow water?”). This observation of the natural world may inspire you to investigate background literature or your observation could be based on previous research by others or your own pilot study. Broad questions are not always included in your written text, but are essential for establishing the direction of your research.

Background Information : key issues, concepts, terminology, and definitions needed to understand the biological rationale for the experiment. It often includes a summary of findings from previous, relevant studies. Remember to cite references, be concise, and only include relevant information given your audience and your experimental design. Concisely summarized background information leads to the identification of specific scientific knowledge gaps that still exist. (e.g., “No studies to date have examined whether guppies do indeed spend more time in shallow water.”)

Testable Question : these questions are much more focused than the initial broad question, are specific to the knowledge gap identified, and can be addressed with data. (e.g., “Do guppies spend different amounts of time in water <1 meter deep as compared to their time in water that is >1 meter deep?”)

Biological Rationale : describes the purpose of your experiment distilling what is known and what is not known that defines the knowledge gap that you are addressing. The “BR” provides the logic for your hypothesis and experimental approach, describing the biological mechanism and assumptions that explain why your hypothesis should be true.

The biological rationale is based on your interpretation of the scientific literature, your personal observations, and the underlying assumptions you are making about how you think the system works. If you have written your biological rationale, your reader should see your hypothesis in your introduction section and say to themselves, “Of course, this hypothesis seems very logical based on the rationale presented.”

- A thorough rationale defines your assumptions about the system that have not been revealed in scientific literature or from previous systematic observation. These assumptions drive the direction of your specific hypothesis or general predictions.

- Defining the rationale is probably the most critical task for a writer, as it tells your reader why your research is biologically meaningful. It may help to think about the rationale as an answer to the questions— how is this investigation related to what we know, what assumptions am I making about what we don’t yet know, AND how will this experiment add to our knowledge? *There may or may not be broader implications for your study; be careful not to overstate these (see note on social justifications below).

- Expect to spend time and mental effort on this. You may have to do considerable digging into the scientific literature to define how your experiment fits into what is already known and why it is relevant to pursue.

- Be open to the possibility that as you work with and think about your data, you may develop a deeper, more accurate understanding of the experimental system. You may find the original rationale needs to be revised to reflect your new, more sophisticated understanding.

- As you progress through Biocore and upper level biology courses, your rationale should become more focused and matched with the level of study e ., cellular, biochemical, or physiological mechanisms that underlie the rationale. Achieving this type of understanding takes effort, but it will lead to better communication of your science.

***Special note on avoiding social justifications: You should not overemphasize the relevance of your experiment and the possible connections to large-scale processes. Be realistic and logical —do not overgeneralize or state grand implications that are not sensible given the structure of your experimental system. Not all science is easily applied to improving the human condition. Performing an investigation just for the sake of adding to our scientific knowledge (“pure or basic science”) is just as important as applied science. In fact, basic science often provides the foundation for applied studies.

Hypothesis / Predictions : specific prediction(s) that you will test during your experiment. For manipulative experiments, the hypothesis should include the independent variable (what you manipulate), the dependent variable(s) (what you measure), the organism or system , the direction of your results, and comparison to be made.

|

|

We hypothesized that reared in warm water will have a greater sexual mating response. (The dependent variable “sexual response” has not been defined enough to be able to make this hypothesis testable or falsifiable. In addition, no comparison has been specified— greater sexual mating response as compared to what?) | We hypothesized that ) reared in warm water temperatures ranging from 25-28 °C ( ) would produce greater ( ) numbers of male offspring and females carrying haploid egg sacs ( ) than reared in cooler water temperatures of 18-22°C. |

If you are doing a systematic observation , your hypothesis presents a variable or set of variables that you predict are important for helping you characterize the system as a whole, or predict differences between components/areas of the system that help you explain how the system functions or changes over time.

|

|