Literature Reviews: systematic searching at various levels

- for assignments

- for dissertations / theses

- Search strategy and searching

- Boolean Operators

- Search strategy template

- Screening & critiquing

- Citation Searching

- Google Scholar (with Lean Library)

- Resources for literature reviews

- Adding a referencing style to EndNote

- Exporting from different databases

PRISMA Flow Diagram

- Grey Literature

- What is the PRISMA Flow Diagram?

- How should I use it?

- When should I use it?

- PRISMA Links

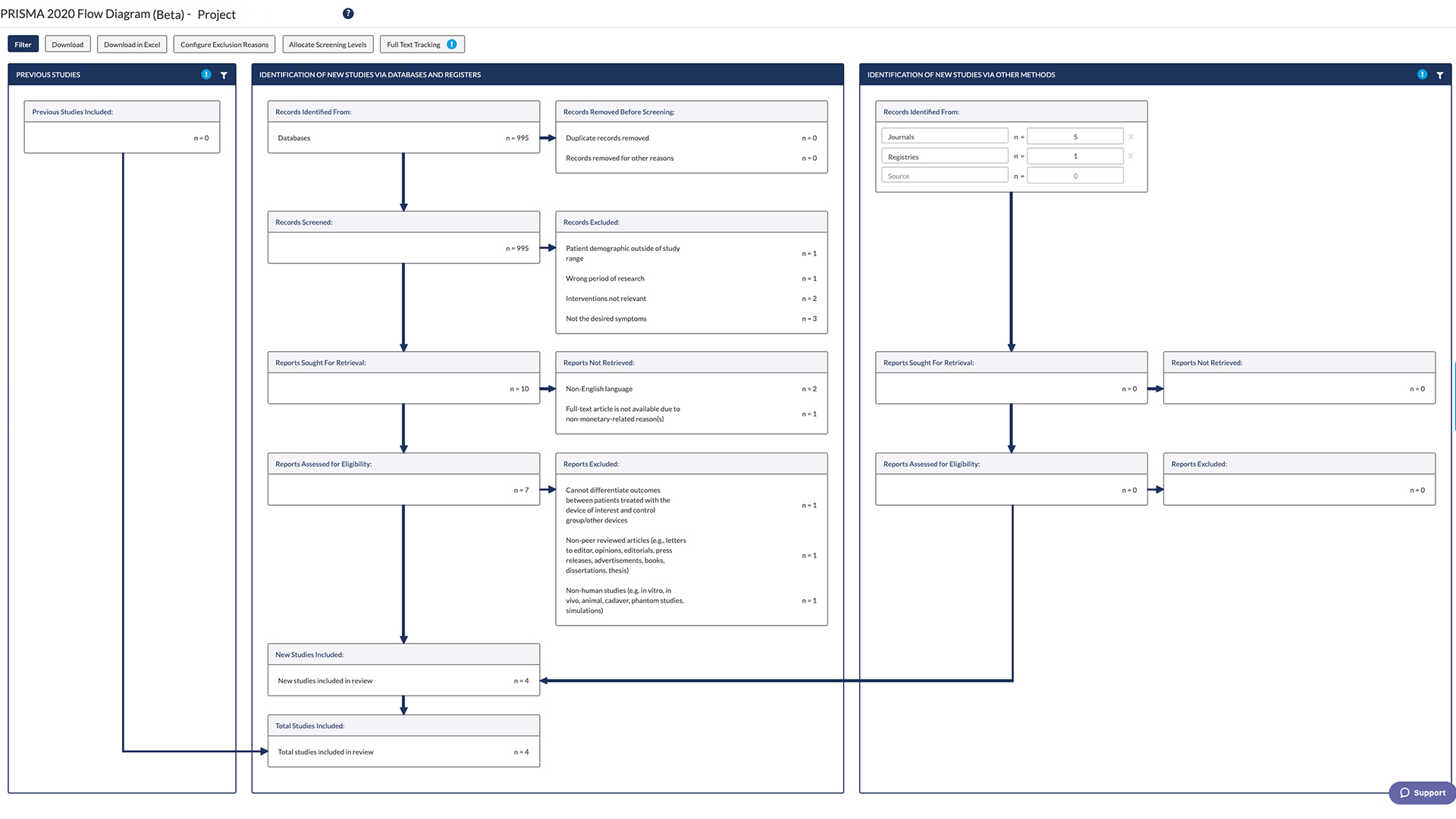

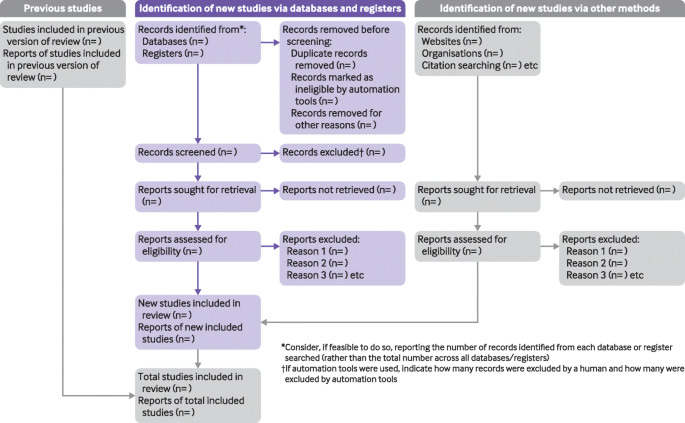

The PRISMA Flow Diagram is a tool that can be used to record different stages of the literature search process--across multiple resources--and clearly show how a researcher went from, 'These are the databases I searched for my terms', to, 'These are the papers I'm going to talk about'.

PRISMA is not inflexible; it can be modified to suit the research needs of different people and, indeed, if you did a Google images search for the flow diagram you would see many different versions of the diagram being used. It's a good idea to have a look at a couple of those examples, and also to have a look at a couple of the articles on the PRISMA website to see how it has--and can--be used.

The PRISMA 2020 Statement was published in 2021. It consists of a checklist and a flow diagram , and is intended to be accompanied by the PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration document.

In order to encourage dissemination of the PRISMA 2020 Statement, it has been published in several journals.

- How to use the PRISMA Flow Diagram for literature reviews A PDF [3.81MB] of the PowerPoint used to create the video. Each slide that has notes has a callout icon on the top right of the page which can be toggled on or off to make the notes visible.

There is also a PowerPoint version of the document and if you are a member of the University of Derby you can access the PRISMA Flow Diagram PPT via the link. (You will need to log in / be logged in with your University credentials to access this.)

This is an example of how you could fill in the PRISMA flow diagram when conducting a new review. It is not a hard and fast rule but it should give you an idea of how you can use it.

For more detailed information, please have a look at this article:

Page, M.J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T.C., Mulrow, C.D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J.M., Akl, E.A., Brennan, S.E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J.M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M.M., Li, T., Loder, E.W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L.A., Stewart, L.A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A.C., Welch, V.A., Whiting,P. & Moher, D. (2021) 'The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews', BMJ 372:(71). doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 .

- Example of PRISMA 2020 diagram This is an example of *one* of the PRISMA 2020 flow diagrams you can use when reporting on your research process. There is more than one form that you can use so for other forms and advice please look at the PRISMA website for full details.

Start using the flow diagram as you start searching the databases you've decided upon.

Make sure that you record the number of results that you found per database (before removing any duplicates) as per the filled in example. You can also do a Google images search for the PRISMA flow diagram to see the different ways in which people have used them to express their search processes.

- Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) PRISMA is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. PRISMA focuses on the reporting of reviews evaluating randomized trials, but can also be used as a basis for reporting systematic reviews of other types of research, particularly evaluations of interventions.

- Prisma Flow Diagram This link will take you to downloadable Word and PDF copies of the flow diagram. These are modifiable and act as a starting point for you to record the process you engaged in from first search to the papers you ultimately discuss in your work. more... less... Do an image search on the internet for the flow diagram and you will be able to see all the different ways that people have modified the diagram to suit their personal research needs.

You can access the various checklists via the Equator website and the articles explaining PRISMA and its various extensions are available via PubMed.

Page, M.J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T.C., Mulrow, C.D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J.M., Akl, E.A., Brennan, S.E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J.M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M.M., Li, T., Loder, E.W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L.A., Stewart, L.A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A.C., Welch, V.A., Whiting, P., & Moher, D. (2021) ' The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews,' BMJ . Mar 29; 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 .

Page, M.J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T.C., Mulrow, C.D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J.M., Akl, E.A., Brennan, S.E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J.M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M.M., Li, T., Loder, E.W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L.A., Stewart, L.A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A.C., Welch, V.A., Whiting, P., & McKenzie, J.E. (2021) 'PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews', BMJ, Mar 29; 372:n160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160 .

Page, M.J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T.C., Mulrow, C.D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J.M., Akl, E.A., Brennan, S.E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J.M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M.M., Li, T., Loder, E.W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L.A., Stewart, L.A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A.C., Welch, V.A., Whiting, P., & Moher, D. (2021) ' The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews,' Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, June; 134:178-189. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.001 .

- << Previous: Exporting from different databases

- Next: Grey Literature >>

- Last Updated: Sep 25, 2024 11:09 AM

- URL: https://libguides.derby.ac.uk/literature-reviews

♨️ A step-by-step process

Using the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines involves a step-by-step process to ensure that your systematic review or meta-analysis is reported transparently and comprehensively. Below are the key steps to follow when using PRISMA 2020:

1. Understand the PRISMA 2020 Checklist: Familiarize yourself with the PRISMA 2020 Checklist and its 27 essential items. You can access the checklist and an explanation of each item from the official PRISMA website or publication.

2. Plan Your Systematic Review: Before starting your review, clearly define your research question, objectives, and inclusion/exclusion criteria for selecting studies. Ensure that your research question aligns with the PRISMA 2020 framework.

3. Develop a Protocol: Create a systematic review protocol that outlines the methodology you'll use, including search strategies, data extraction methods, and the approach to assessing risk of bias (if applicable). Register your protocol on a relevant platform like PROSPERO.

4. Conduct the Literature Search: Search for relevant studies using a systematic and comprehensive approach. Document the search strategy, databases used, search terms, and any filters applied. Ensure that your search covers the time period and study designs specified in your protocol.

5. Study Selection: Implement your inclusion/exclusion criteria to screen and select studies. Maintain detailed records of the screening process, including reasons for exclusion.

6. Data Extraction: Extract data from the selected studies using a predefined template. Include information on study characteristics, outcomes, and any other relevant data points. Ensure that your data extraction process is consistent and well-documented.

7. Risk of Bias Assessment: If applicable, assess the risk of bias in the included studies. Use appropriate tools or criteria and clearly report the results of the assessment.

8. Data Synthesis and Meta-Analysis: If relevant, conduct data synthesis and meta-analysis. Follow established statistical methods and guidelines for pooling data, calculating effect sizes, and assessing heterogeneity.

9. Report According to PRISMA 2020: When writing your systematic review or meta-analysis manuscript, ensure that you follow the PRISMA 2020 Checklist. Address each of the 27 items in the checklist in your manuscript. This includes providing clear information on your research question, search strategy, inclusion/exclusion criteria, data extraction process, risk of bias assessment, and results.

10. Transparency and Supplementary Materials: Provide supplementary materials such as a PRISMA flow diagram showing the study selection process and a summary table of included studies. These add to the transparency of your review.

11. Peer Review and Revision: Submit your manuscript to a peer-reviewed journal that accepts systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Be prepared to respond to reviewers' comments and make necessary revisions to adhere to PRISMA 2020.

12. Publish and Share: Once your systematic review or meta-analysis is accepted and published, consider sharing it on platforms like PROSPERO or other relevant databases for greater visibility.

Throughout the process, maintaining transparency, consistency, and adherence to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines will help ensure that your systematic review or meta-analysis is of high quality and can be effectively used by researchers, policymakers, and practitioners in your field.

Last updated 1 year ago

This website may not work correctly because your browser is out of date. Please update your browser .

- PRISMA flow diagram generator

Resource link

- PRISMA flow diagram templates

This tool, developed by PRISMA, can be used to develop a PRISMA flow diagram in order to report on systematic reviews.

The flow diagram depicts the flow of information through the different phases of a systematic review. It maps out the number of records identified, included and excluded, and the reasons for exclusions.

The aim of the PRISMA Statement is to help authors report a wide array of systematic reviews to assess the benefits and harms of a health care intervention. PRISMA focuses on ways in which authors can ensure the transparent and complete reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

We have adopted the definitions of systematic review and meta-analysis used by the Cochrane Collaboration [9]. A systematic review is a review of a clearly formulated question that uses systematic and explicit methods to identify, select, and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review. Statistical methods (meta-analysis) may or may not be used to analyse and summarise the results of the included studies. Meta-analysis refers to the use of statistical techniques in a systematic review to integrate the results of included studies.

PRISMA (n.d.). PRISMA Flow Diagram Generator . Retrieved from: https://estech.shinyapps.io/prisma_flowdiagram/

PRISMA (n.d.). PRISMA Flow Diagram Generator . Retrieved from: http://prisma-statement.org/PRISMAStatement/

'PRISMA flow diagram generator' is referenced in:

- Systematic review

Back to top

© 2022 BetterEvaluation. All right reserved.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 23, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, what is your plagiarism score.

- UNC Libraries

- HSL Academic Process

- Systematic Reviews

- Step 8: Write the Review

Systematic Reviews: Step 8: Write the Review

Created by health science librarians.

- Step 1: Complete Pre-Review Tasks

- Step 2: Develop a Protocol

- Step 3: Conduct Literature Searches

- Step 4: Manage Citations

- Step 5: Screen Citations

- Step 6: Assess Quality of Included Studies

- Step 7: Extract Data from Included Studies

About Step 8: Write the Review

Write your review, report your review with prisma, review sections, plain language summaries for systematic reviews, writing the review- webinars.

- Writing the Review FAQs

Check our FAQ's

Email us

Call (919) 962-0800

Make an appointment with a librarian

Request a systematic or scoping review consultation

Search the FAQs

In Step 8, you will write an article or a paper about your systematic review. It will likely have five sections: introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. You will:

- Review the reporting standards you will use, such as PRISMA.

- Gather your completed data tables and PRISMA chart.

- Write the Introduction to the topic and your study, Methods of your research, Results of your research, and Discussion of your results.

- Write an Abstract describing your study and a Conclusion summarizing your paper.

- Cite the studies included in your systematic review and any other articles you may have used in your paper.

- If you wish to publish your work, choose a target journal for your article.

The PRISMA Checklist will help you report the details of your systematic review. Your paper will also include a PRISMA chart that is an image of your research process.

Click an item below to see how it applies to Step 8: Write the Review.

Reporting your review with PRISMA

To write your review, you will need the data from your PRISMA flow diagram . Review the PRISMA checklist to see which items you should report in your methods section.

Managing your review with Covidence

When you screen in Covidence, it will record the numbers you need for your PRISMA flow diagram from duplicate removal through inclusion of studies. You may need to add additional information, such as the number of references from each database, citations you find through grey literature or other searching methods, or the number of studies found in your previous work if you are updating a systematic review.

How a librarian can help with Step 8

A librarian can advise you on the process of organizing and writing up your systematic review, including:

- Applying the PRISMA reporting templates and the level of detail to include for each element

- How to report a systematic review search strategy and your review methodology in the completed review

- How to use prior published reviews to guide you in organizing your manuscript

Reporting standards & guidelines

Be sure to reference reporting standards when writing your review. This helps ensure that you communicate essential components of your methods, results, and conclusions. There are a number of tools that can be used to ensure compliance with reporting guidelines. A few review-writing resources are listed below.

- Cochrane Handbook - Chapter 15: Interpreting results and drawing conclusions

- JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis - Chapter 1: systematic reviews

- PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) The aim of the PRISMA Statement is to help authors improve the reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Tools for writing your review

- RevMan (Cochrane Training)

- Methods Wizard (Systematic Review Accelerator) The Methods Wizard is part of the Systematic Review Accelerator created by Bond University and the Institute for Evidence-Based Healthcare.

- UNC HSL Systematic Review Manuscript Template Systematic review manuscript template(.doc) adapted from the PRISMA 2020 checklist. This document provides authors with template for writing about their systematic review. Each table contains a PRISMA checklist item that should be written about in that section, the matching PRISMA Item number, and a box where authors can indicate if an item has been completed. Once text has been added, delete any remaining instructions and the PRISMA checklist tables from the end of each section.

- The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews The PRISMA 2020 statement replaces the 2009 statement and includes new reporting guidance that reflects advances in methods to identify, select, appraise, and synthesise studies.

- PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews This document is intended to enhance the use, understanding and dissemination of the PRISMA 2020 Statement. Through examples and explanations, the meaning and rationale for each checklist item are presented.

The PRISMA checklist

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) is a 27-item checklist used to improve transparency in systematic reviews. These items cover all aspects of the manuscript, including title, abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and funding. The PRISMA checklist can be downloaded in PDF or Word files.

- PRISMA 2020 Checklists Download the 2020 PRISMA Checklists in Word or PDF formats or download the expanded checklist (PDF).

The PRISMA flow diagram

The PRISMA Flow Diagram visually depicts the flow of studies through each phase of the review process. The PRISMA Flow Diagram can be downloaded in Word files.

- PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagrams The flow diagram depicts the flow of information through the different phases of a systematic review. It maps out the number of records identified, included and excluded, and the reasons for exclusions. Different templates are available depending on the type of review (new or updated) and sources used to identify studies.

Documenting grey literature and/or hand searches

If you have also searched additional sources, such as professional organization websites, cited or citing references, etc., document your grey literature search using the flow diagram template version 1 PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources or the version 2 PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for updated systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources .

Complete the boxes documenting your database searches, Identification of studies via databases and registers, according to the PRISMA flow diagram instructions. Complete the boxes documenting your grey literature and/or hand searches on the right side of the template, Identification of studies via other methods, using the steps below.

Need help completing the PRISMA flow diagram?

There are different PRISMA flow diagram templates for new and updated reviews, as well as different templates for reviews with and without grey literature searches. Be sure you download the correct template to match your review methods, then follow the steps below for each portion of the diagram you have available.

View the step-by-step explanation of the PRISMA flow diagram

Step 1: Preparation Download the flow diagram template version 1 PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only or the version 2 PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for updated systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only .

| Run the search for each NOTE:Some citation managers automatically remove duplicates | |

| To avoid reviewing duplicate articles, If you are using Covidence to screen your articles, you can | |

| The next step is to add the number of articles that you will screen. This should be the number of records identified minus the number from the duplicates removed box. | |

| You will need to screen the titles and abstracts for articles which are relevant to your research question. Any articles that appear to help you provide an answer to your research question should be included. Record the number of articles excluded through title/abstract screening in the box to the right titled "Records excluded." You can optionally add exclusion reasons at this level, but they are not required until full text screening. | |

| This is the number of articles you obtain in preparation for full text screening. Subtract the number of excluded records (Step 5) from the total number screened (Step 4) and this will be your number sought for retrieval. | |

| List the number of articles for which you are unable to find the full text. Remember to use Find@UNC and to request articles to see if we can order them from other libraries before automatically excluding them. | |

| This should be the number of reports sought for retrieval (Step 6) minus the number of reports not retrieved (Step 7). Review the full text for these articles to assess their eligibility for inclusion in your systematic review. | |

| After reviewing all articles in the full-text screening stage for eligibility, enter the total number of articles you exclude in the box titled "Reports excluded," and then list your reasons for excluding the articles as well as the number of records excluded for each reason. Examples include wrong setting, wrong patient population, wrong intervention, wrong dosage, etc. You should only count an excluded article once in your list even if if meets multiple exclusion criteria. | |

| The final step is to subtract the number |

View the step-by-step explanation of the grey literature & hand searching portion of the PRISMA flow diagram

Step 1: Preparation Download the flow diagram template version 1 PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources or the version 2 PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for updated systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources .

| If you have identified articles through other sources than databases (such as manual searches through reference lists of articles you have found or search engines like Google Scholar), enter the total number of records from each source type in the box on the top right of the flow diagram. | |

| This should be the total number of reports you obtain from each grey literature source. | |

| List the number of documents for which you are unable to find the full text. Remember to use Find@UNC and to request items to see if we can order them from other libraries before automatically excluding them. | |

| This should be the number of grey literature reports sought for retrieval (Step 2) minus the number of reports not retrieved (Step 3). Review the full text for these items to assess their eligibility for inclusion in your systematic review. | |

| After reviewing all items in the full-text screening stage for eligibility, enter the total number of articles you exclude in the box titled "Reports Excluded," and then list your reasons for excluding the item as well as the number of items excluded for each reason. Examples include wrong setting, wrong patient population, wrong intervention, wrong dosage, etc. You should only count an excluded item once in your list even if if meets multiple exclusion criteria. | |

| The final step is to subtract the number of excluded articles or records during the eligibility review of full-texts from the total number of articles reviewed for eligibility. Enter this number in the box labeled "Studies included in review," combining numbers with your database search results in this box if needed. You have now completed your PRISMA flow diagram, which you can now include in the results section of your article or assignment. |

View the step-by-step explanation of review update portion of the PRISMA flow diagram

Step 1: Preparation Download the flow diagram template version 2 PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for updated systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only or the version 2 PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for updated systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources .

| In the Previous

| |

| At the bottom of the column, There will also be a box for the total number of studies included in your |

For more information about updating your systematic review, see the box Updating Your Review? on the Step 3: Conduct Literature Searches page of the guide.

Sections of a Scientific Manuscript

Scientific articles often follow the IMRaD format: Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion. You will also need a title and an abstract to summarize your research.

You can read more about scientific writing through the library guides below.

- Structure of Scholarly Articles & Peer Review • Explains the standard parts of a medical research article • Compares scholarly journals, professional trade journals, and magazines • Explains peer review and how to find peer reviewed articles and journals

- Writing in the Health Sciences (For Students and Instructors)

- Citing & Writing Tools & Guides Includes links to guides for popular citation managers such as EndNote, Sciwheel, Zotero; copyright basics; APA & AMA Style guides; Plagiarism & Citing Sources; Citing & Writing: How to Write Scientific Papers

Sections of a Systematic Review Manuscript

Systematic reviews follow the same structure as original research articles, but you will need to report on your search instead of on details like the participants or sampling. Sections of your manuscript are shown as bold headings in the PRISMA checklist.

| Title | Describe your manuscript and state whether it is a systematic review, meta-analysis, or both. |

|---|---|

| Abstract | Structure the abstract and include (as applicable): background, objectives, data sources, study eligibility criteria, participants, interventions, quality assessment and synthesis methods, results, limitations, conclusions, implications of key findings, and systematic review registration number. |

| Introduction | Describe the rationale for the review and provide a statement of questions being addressed. |

| Methods | Include details regarding the protocol, eligibility criteria, databases searched, full search strategy of at least one database (often reported in appendix), and the study selection process. Describe how data were extracted and analyzed. If a librarian is part of your research team, that person may be best suited to write this section. |

| Results | Report the numbers of articles screened at each stage using a PRISMA diagram. Include information about included study characteristics, risk of bias (quality assessment) within studies, and results across studies. |

| Discussion | Summarize main findings, including the strength of evidence and limitations of the review. Provide a general interpretation of the results and implications for future research. |

| Funding | Describe any sources of funding for the systematic review. |

| Appendix | Include entire search strategy for at least one database in the appendix (include search strategies for all databases searched for more transparency). |

Refer to the PRISMA checklist for more information.

Consider including a Plain Language Summary (PLS) when you publish your systematic review. Like an abstract, a PLS gives an overview of your study, but is specifically written and formatted to be easy for non-experts to understand.

Tips for writing a PLS:

- Use clear headings e.g. "why did we do this study?"; "what did we do?"; "what did we find?"

- Use active voice e.g. "we searched for articles in 5 databases instead of "5 databases were searched"

- Consider need-to-know vs. nice-to-know: what is most important for readers to understand about your study? Be sure to provide the most important points without misrepresenting your study or misleading the reader.

- Keep it short: Many journals recommend keeping your plain language summary less than 250 words.

- Check journal guidelines: Your journal may have specific guidelines about the format of your plain language summary and when you can publish it. Look at journal guidelines before submitting your article.

Learn more about Plain Language Summaries:

- Rosenberg, A., Baróniková, S., & Feighery, L. (2021). Open Pharma recommendations for plain language summaries of peer-reviewed medical journal publications. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 37(11), 2015–2016. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2021.1971185

- Lobban, D., Gardner, J., & Matheis, R. (2021). Plain language summaries of publications of company-sponsored medical research: what key questions do we need to address? Current Medical Research and Opinion, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2021.1997221

- Cochrane Community. (2022, March 21). Updated template and guidance for writing Plain Language Summaries in Cochrane Reviews now available. https://community.cochrane.org/news/updated-template-and-guidance-writing-plain-language-summaries-cochrane-reviews-now-available

- You can also look at our Health Literacy LibGuide: https://guides.lib.unc.edu/healthliteracy

How to Approach Writing a Background Section

What Makes a Good Discussion Section

Writing Up Risk of Bias

Developing Your Implications for Research Section

- << Previous: Step 7: Extract Data from Included Studies

- Next: FAQs >>

- Last Updated: Jul 15, 2024 4:55 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.unc.edu/systematic-reviews

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 9:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

Steps in the literature review process.

- What is a literature review?

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Tools

- You may need to some exploratory searching of the literature to get a sense of scope, to determine whether you need to narrow or broaden your focus

- Identify databases that provide the most relevant sources, and identify relevant terms (controlled vocabularies) to add to your search strategy

- Finalize your research question

- Think about relevant dates, geographies (and languages), methods, and conflicting points of view

- Conduct searches in the published literature via the identified databases

- Check to see if this topic has been covered in other discipline's databases

- Examine the citations of on-point articles for keywords, authors, and previous research (via references) and cited reference searching.

- Save your search results in a citation management tool (such as Zotero, Mendeley or EndNote)

- De-duplicate your search results

- Make sure that you've found the seminal pieces -- they have been cited many times, and their work is considered foundational

- Check with your professor or a librarian to make sure your search has been comprehensive

- Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of individual sources and evaluate for bias, methodologies, and thoroughness

- Group your results in to an organizational structure that will support why your research needs to be done, or that provides the answer to your research question

- Develop your conclusions

- Are there gaps in the literature?

- Where has significant research taken place, and who has done it?

- Is there consensus or debate on this topic?

- Which methodological approaches work best?

- For example: Background, Current Practices, Critics and Proponents, Where/How this study will fit in

- Organize your citations and focus on your research question and pertinent studies

- Compile your bibliography

Note: The first four steps are the best points at which to contact a librarian. Your librarian can help you determine the best databases to use for your topic, assess scope, and formulate a search strategy.

Videos Tutorials about Literature Reviews

This 4.5 minute video from Academic Education Materials has a Creative Commons License and a British narrator.

Recommended Reading

- Last Updated: Aug 26, 2024 5:59 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

How To Write An A-Grade Literature Review

3 straightforward steps (with examples) + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | October 2019

Quality research is about building onto the existing work of others , “standing on the shoulders of giants”, as Newton put it. The literature review chapter of your dissertation, thesis or research project is where you synthesise this prior work and lay the theoretical foundation for your own research.

Long story short, this chapter is a pretty big deal, which is why you want to make sure you get it right . In this post, I’ll show you exactly how to write a literature review in three straightforward steps, so you can conquer this vital chapter (the smart way).

Overview: The Literature Review Process

- Understanding the “ why “

- Finding the relevant literature

- Cataloguing and synthesising the information

- Outlining & writing up your literature review

- Example of a literature review

But first, the “why”…

Before we unpack how to write the literature review chapter, we’ve got to look at the why . To put it bluntly, if you don’t understand the function and purpose of the literature review process, there’s no way you can pull it off well. So, what exactly is the purpose of the literature review?

Well, there are (at least) four core functions:

- For you to gain an understanding (and demonstrate this understanding) of where the research is at currently, what the key arguments and disagreements are.

- For you to identify the gap(s) in the literature and then use this as justification for your own research topic.

- To help you build a conceptual framework for empirical testing (if applicable to your research topic).

- To inform your methodological choices and help you source tried and tested questionnaires (for interviews ) and measurement instruments (for surveys ).

Most students understand the first point but don’t give any thought to the rest. To get the most from the literature review process, you must keep all four points front of mind as you review the literature (more on this shortly), or you’ll land up with a wonky foundation.

Okay – with the why out the way, let’s move on to the how . As mentioned above, writing your literature review is a process, which I’ll break down into three steps:

- Finding the most suitable literature

- Understanding , distilling and organising the literature

- Planning and writing up your literature review chapter

Importantly, you must complete steps one and two before you start writing up your chapter. I know it’s very tempting, but don’t try to kill two birds with one stone and write as you read. You’ll invariably end up wasting huge amounts of time re-writing and re-shaping, or you’ll just land up with a disjointed, hard-to-digest mess . Instead, you need to read first and distil the information, then plan and execute the writing.

Step 1: Find the relevant literature

Naturally, the first step in the literature review journey is to hunt down the existing research that’s relevant to your topic. While you probably already have a decent base of this from your research proposal , you need to expand on this substantially in the dissertation or thesis itself.

Essentially, you need to be looking for any existing literature that potentially helps you answer your research question (or develop it, if that’s not yet pinned down). There are numerous ways to find relevant literature, but I’ll cover my top four tactics here. I’d suggest combining all four methods to ensure that nothing slips past you:

Method 1 – Google Scholar Scrubbing

Google’s academic search engine, Google Scholar , is a great starting point as it provides a good high-level view of the relevant journal articles for whatever keyword you throw at it. Most valuably, it tells you how many times each article has been cited, which gives you an idea of how credible (or at least, popular) it is. Some articles will be free to access, while others will require an account, which brings us to the next method.

Method 2 – University Database Scrounging

Generally, universities provide students with access to an online library, which provides access to many (but not all) of the major journals.

So, if you find an article using Google Scholar that requires paid access (which is quite likely), search for that article in your university’s database – if it’s listed there, you’ll have access. Note that, generally, the search engine capabilities of these databases are poor, so make sure you search for the exact article name, or you might not find it.

Method 3 – Journal Article Snowballing

At the end of every academic journal article, you’ll find a list of references. As with any academic writing, these references are the building blocks of the article, so if the article is relevant to your topic, there’s a good chance a portion of the referenced works will be too. Do a quick scan of the titles and see what seems relevant, then search for the relevant ones in your university’s database.

Method 4 – Dissertation Scavenging

Similar to Method 3 above, you can leverage other students’ dissertations. All you have to do is skim through literature review chapters of existing dissertations related to your topic and you’ll find a gold mine of potential literature. Usually, your university will provide you with access to previous students’ dissertations, but you can also find a much larger selection in the following databases:

- Open Access Theses & Dissertations

- Stanford SearchWorks

Keep in mind that dissertations and theses are not as academically sound as published, peer-reviewed journal articles (because they’re written by students, not professionals), so be sure to check the credibility of any sources you find using this method. You can do this by assessing the citation count of any given article in Google Scholar. If you need help with assessing the credibility of any article, or with finding relevant research in general, you can chat with one of our Research Specialists .

Alright – with a good base of literature firmly under your belt, it’s time to move onto the next step.

Need a helping hand?

Step 2: Log, catalogue and synthesise

Once you’ve built a little treasure trove of articles, it’s time to get reading and start digesting the information – what does it all mean?

While I present steps one and two (hunting and digesting) as sequential, in reality, it’s more of a back-and-forth tango – you’ll read a little , then have an idea, spot a new citation, or a new potential variable, and then go back to searching for articles. This is perfectly natural – through the reading process, your thoughts will develop , new avenues might crop up, and directional adjustments might arise. This is, after all, one of the main purposes of the literature review process (i.e. to familiarise yourself with the current state of research in your field).

As you’re working through your treasure chest, it’s essential that you simultaneously start organising the information. There are three aspects to this:

- Logging reference information

- Building an organised catalogue

- Distilling and synthesising the information

I’ll discuss each of these below:

2.1 – Log the reference information

As you read each article, you should add it to your reference management software. I usually recommend Mendeley for this purpose (see the Mendeley 101 video below), but you can use whichever software you’re comfortable with. Most importantly, make sure you load EVERY article you read into your reference manager, even if it doesn’t seem very relevant at the time.

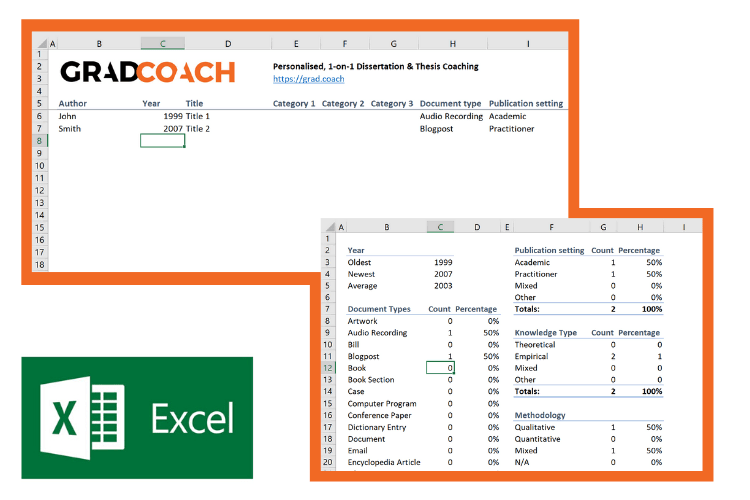

2.2 – Build an organised catalogue

In the beginning, you might feel confident that you can remember who said what, where, and what their main arguments were. Trust me, you won’t. If you do a thorough review of the relevant literature (as you must!), you’re going to read many, many articles, and it’s simply impossible to remember who said what, when, and in what context . Also, without the bird’s eye view that a catalogue provides, you’ll miss connections between various articles, and have no view of how the research developed over time. Simply put, it’s essential to build your own catalogue of the literature.

I would suggest using Excel to build your catalogue, as it allows you to run filters, colour code and sort – all very useful when your list grows large (which it will). How you lay your spreadsheet out is up to you, but I’d suggest you have the following columns (at minimum):

- Author, date, title – Start with three columns containing this core information. This will make it easy for you to search for titles with certain words, order research by date, or group by author.

- Categories or keywords – You can either create multiple columns, one for each category/theme and then tick the relevant categories, or you can have one column with keywords.

- Key arguments/points – Use this column to succinctly convey the essence of the article, the key arguments and implications thereof for your research.

- Context – Note the socioeconomic context in which the research was undertaken. For example, US-based, respondents aged 25-35, lower- income, etc. This will be useful for making an argument about gaps in the research.

- Methodology – Note which methodology was used and why. Also, note any issues you feel arise due to the methodology. Again, you can use this to make an argument about gaps in the research.

- Quotations – Note down any quoteworthy lines you feel might be useful later.

- Notes – Make notes about anything not already covered. For example, linkages to or disagreements with other theories, questions raised but unanswered, shortcomings or limitations, and so forth.

If you’d like, you can try out our free catalog template here (see screenshot below).

2.3 – Digest and synthesise

Most importantly, as you work through the literature and build your catalogue, you need to synthesise all the information in your own mind – how does it all fit together? Look for links between the various articles and try to develop a bigger picture view of the state of the research. Some important questions to ask yourself are:

- What answers does the existing research provide to my own research questions ?

- Which points do the researchers agree (and disagree) on?

- How has the research developed over time?

- Where do the gaps in the current research lie?

To help you develop a big-picture view and synthesise all the information, you might find mind mapping software such as Freemind useful. Alternatively, if you’re a fan of physical note-taking, investing in a large whiteboard might work for you.

Step 3: Outline and write it up!

Once you’re satisfied that you have digested and distilled all the relevant literature in your mind, it’s time to put pen to paper (or rather, fingers to keyboard). There are two steps here – outlining and writing:

3.1 – Draw up your outline

Having spent so much time reading, it might be tempting to just start writing up without a clear structure in mind. However, it’s critically important to decide on your structure and develop a detailed outline before you write anything. Your literature review chapter needs to present a clear, logical and an easy to follow narrative – and that requires some planning. Don’t try to wing it!

Naturally, you won’t always follow the plan to the letter, but without a detailed outline, you’re more than likely going to end up with a disjointed pile of waffle , and then you’re going to spend a far greater amount of time re-writing, hacking and patching. The adage, “measure twice, cut once” is very suitable here.

In terms of structure, the first decision you’ll have to make is whether you’ll lay out your review thematically (into themes) or chronologically (by date/period). The right choice depends on your topic, research objectives and research questions, which we discuss in this article .

Once that’s decided, you need to draw up an outline of your entire chapter in bullet point format. Try to get as detailed as possible, so that you know exactly what you’ll cover where, how each section will connect to the next, and how your entire argument will develop throughout the chapter. Also, at this stage, it’s a good idea to allocate rough word count limits for each section, so that you can identify word count problems before you’ve spent weeks or months writing!

PS – check out our free literature review chapter template…

3.2 – Get writing

With a detailed outline at your side, it’s time to start writing up (finally!). At this stage, it’s common to feel a bit of writer’s block and find yourself procrastinating under the pressure of finally having to put something on paper. To help with this, remember that the objective of the first draft is not perfection – it’s simply to get your thoughts out of your head and onto paper, after which you can refine them. The structure might change a little, the word count allocations might shift and shuffle, and you might add or remove a section – that’s all okay. Don’t worry about all this on your first draft – just get your thoughts down on paper.

Once you’ve got a full first draft (however rough it may be), step away from it for a day or two (longer if you can) and then come back at it with fresh eyes. Pay particular attention to the flow and narrative – does it fall fit together and flow from one section to another smoothly? Now’s the time to try to improve the linkage from each section to the next, tighten up the writing to be more concise, trim down word count and sand it down into a more digestible read.

Once you’ve done that, give your writing to a friend or colleague who is not a subject matter expert and ask them if they understand the overall discussion. The best way to assess this is to ask them to explain the chapter back to you. This technique will give you a strong indication of which points were clearly communicated and which weren’t. If you’re working with Grad Coach, this is a good time to have your Research Specialist review your chapter.

Finally, tighten it up and send it off to your supervisor for comment. Some might argue that you should be sending your work to your supervisor sooner than this (indeed your university might formally require this), but in my experience, supervisors are extremely short on time (and often patience), so, the more refined your chapter is, the less time they’ll waste on addressing basic issues (which you know about already) and the more time they’ll spend on valuable feedback that will increase your mark-earning potential.

Literature Review Example

In the video below, we unpack an actual literature review so that you can see how all the core components come together in reality.

Let’s Recap

In this post, we’ve covered how to research and write up a high-quality literature review chapter. Let’s do a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- It is essential to understand the WHY of the literature review before you read or write anything. Make sure you understand the 4 core functions of the process.

- The first step is to hunt down the relevant literature . You can do this using Google Scholar, your university database, the snowballing technique and by reviewing other dissertations and theses.

- Next, you need to log all the articles in your reference manager , build your own catalogue of literature and synthesise all the research.

- Following that, you need to develop a detailed outline of your entire chapter – the more detail the better. Don’t start writing without a clear outline (on paper, not in your head!)

- Write up your first draft in rough form – don’t aim for perfection. Remember, done beats perfect.

- Refine your second draft and get a layman’s perspective on it . Then tighten it up and submit it to your supervisor.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

38 Comments

Thank you very much. This page is an eye opener and easy to comprehend.

This is awesome!

I wish I come across GradCoach earlier enough.

But all the same I’ll make use of this opportunity to the fullest.

Thank you for this good job.

Keep it up!

You’re welcome, Yinka. Thank you for the kind words. All the best writing your literature review.

Thank you for a very useful literature review session. Although I am doing most of the steps…it being my first masters an Mphil is a self study and one not sure you are on the right track. I have an amazing supervisor but one also knows they are super busy. So not wanting to bother on the minutae. Thank you.

You’re most welcome, Renee. Good luck with your literature review 🙂

This has been really helpful. Will make full use of it. 🙂

Thank you Gradcoach.

Really agreed. Admirable effort

thank you for this beautiful well explained recap.

Thank you so much for your guide of video and other instructions for the dissertation writing.

It is instrumental. It encouraged me to write a dissertation now.

Thank you the video was great – from someone that knows nothing thankyou

an amazing and very constructive way of presetting a topic, very useful, thanks for the effort,

It is timely

It is very good video of guidance for writing a research proposal and a dissertation. Since I have been watching and reading instructions, I have started my research proposal to write. I appreciate to Mr Jansen hugely.

I learn a lot from your videos. Very comprehensive and detailed.

Thank you for sharing your knowledge. As a research student, you learn better with your learning tips in research

I was really stuck in reading and gathering information but after watching these things are cleared thanks, it is so helpful.

Really helpful, Thank you for the effort in showing such information

This is super helpful thank you very much.

Thank you for this whole literature writing review.You have simplified the process.

I’m so glad I found GradCoach. Excellent information, Clear explanation, and Easy to follow, Many thanks Derek!

You’re welcome, Maithe. Good luck writing your literature review 🙂

Thank you Coach, you have greatly enriched and improved my knowledge

Great piece, so enriching and it is going to help me a great lot in my project and thesis, thanks so much

This is THE BEST site for ANYONE doing a masters or doctorate! Thank you for the sound advice and templates. You rock!

Thanks, Stephanie 🙂

This is mind blowing, the detailed explanation and simplicity is perfect.

I am doing two papers on my final year thesis, and I must stay I feel very confident to face both headlong after reading this article.

thank you so much.

if anyone is to get a paper done on time and in the best way possible, GRADCOACH is certainly the go to area!

This is very good video which is well explained with detailed explanation

Thank you excellent piece of work and great mentoring

Thanks, it was useful

Thank you very much. the video and the information were very helpful.

Good morning scholar. I’m delighted coming to know you even before the commencement of my dissertation which hopefully is expected in not more than six months from now. I would love to engage my study under your guidance from the beginning to the end. I love to know how to do good job

Thank you so much Derek for such useful information on writing up a good literature review. I am at a stage where I need to start writing my one. My proposal was accepted late last year but I honestly did not know where to start

Like the name of your YouTube implies you are GRAD (great,resource person, about dissertation). In short you are smart enough in coaching research work.

This is a very well thought out webpage. Very informative and a great read.

Very timely.

I appreciate.

Very comprehensive and eye opener for me as beginner in postgraduate study. Well explained and easy to understand. Appreciate and good reference in guiding me in my research journey. Thank you

Thank you. I requested to download the free literature review template, however, your website wouldn’t allow me to complete the request or complete a download. May I request that you email me the free template? Thank you.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- The PRISMA 2020...

The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews

PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews

- Related content

- Peer review

- Joanne E McKenzie , associate professor 1 ,

- Patrick M Bossuyt , professor 2 ,

- Isabelle Boutron , professor 3 ,

- Tammy C Hoffmann , professor 4 ,

- Cynthia D Mulrow , professor 5 ,

- Larissa Shamseer , doctoral student 6 ,

- Jennifer M Tetzlaff , research product specialist 7 ,

- Elie A Akl , professor 8 ,

- Sue E Brennan , senior research fellow 1 ,

- Roger Chou , professor 9 ,

- Julie Glanville , associate director 10 ,

- Jeremy M Grimshaw , professor 11 ,

- Asbjørn Hróbjartsson , professor 12 ,

- Manoj M Lalu , associate scientist and assistant professor 13 ,

- Tianjing Li , associate professor 14 ,

- Elizabeth W Loder , professor 15 ,

- Evan Mayo-Wilson , associate professor 16 ,

- Steve McDonald , senior research fellow 1 ,

- Luke A McGuinness , research associate 17 ,

- Lesley A Stewart , professor and director 18 ,

- James Thomas , professor 19 ,

- Andrea C Tricco , scientist and associate professor 20 ,

- Vivian A Welch , associate professor 21 ,

- Penny Whiting , associate professor 17 ,

- David Moher , director and professor 22

- 1 School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

- 2 Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Amsterdam University Medical Centres, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 3 Université de Paris, Centre of Epidemiology and Statistics (CRESS), Inserm, F 75004 Paris, France

- 4 Institute for Evidence-Based Healthcare, Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, Bond University, Gold Coast, Australia

- 5 University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas, USA; Annals of Internal Medicine

- 6 Knowledge Translation Program, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, Toronto, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

- 7 Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada

- 8 Clinical Research Institute, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon; Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

- 9 Department of Medical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon, USA

- 10 York Health Economics Consortium (YHEC Ltd), University of York, York, UK

- 11 Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada; Department of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

- 12 Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Odense (CEBMO) and Cochrane Denmark, Department of Clinical Research, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark; Open Patient data Exploratory Network (OPEN), Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark

- 13 Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Canada; Clinical Epidemiology Program, Blueprint Translational Research Group, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada; Regenerative Medicine Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada

- 14 Department of Ophthalmology, School of Medicine, University of Colorado Denver, Denver, Colorado, United States; Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

- 15 Division of Headache, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Head of Research, The BMJ , London, UK

- 16 Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Indiana University School of Public Health-Bloomington, Bloomington, Indiana, USA

- 17 Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

- 18 Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, York, UK

- 19 EPPI-Centre, UCL Social Research Institute, University College London, London, UK

- 20 Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael's Hospital, Unity Health Toronto, Toronto, Canada; Epidemiology Division of the Dalla Lana School of Public Health and the Institute of Health Management, Policy, and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; Queen's Collaboration for Health Care Quality Joanna Briggs Institute Centre of Excellence, Queen's University, Kingston, Canada

- 21 Methods Centre, Bruyère Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

- 22 Centre for Journalology, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

- Correspondence to: M J Page matthew.page{at}monash.edu

- Accepted 4 January 2021