An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.9(8); 2017 Aug

Case Reports, Case Series – From Clinical Practice to Evidence-Based Medicine in Graduate Medical Education

Jerry w sayre.

1 Family Medicine, North Florida Regional Medical Center

Hale Z Toklu

2 Graduate Medical Education, North Florida Regional Medical Center

Joseph Mazza

3 Department of Clinical Research, Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation

Steven Yale

4 Internal Medicine, University of Central Florida College of Medicine

Case reports and case series or case study research are descriptive studies that are prepared for illustrating novel, unusual, or atypical features identified in patients in medical practice, and they potentially generate new research questions. They are empirical inquiries or investigations of a patient or a group of patients in a natural, real-world clinical setting. Case study research is a method that focuses on the contextual analysis of a number of events or conditions and their relationships. There is disagreement among physicians on the value of case studies in the medical literature, particularly for educators focused on teaching evidence-based medicine (EBM) for student learners in graduate medical education. Despite their limitations, case study research is a beneficial tool and learning experience in graduate medical education and among novice researchers. The preparation and presentation of case studies can help students and graduate medical education programs evaluate and apply the six American College of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) competencies in the areas of medical knowledge, patient care, practice-based learning, professionalism, systems-based practice, and communication. A goal in graduate medical education should be to assist residents to expand their critical thinking, problem-solving, and decision-making skills. These attributes are required in the teaching and practice of EBM. In this aspect, case studies provide a platform for developing clinical skills and problem-based learning methods. Hence, graduate medical education programs should encourage, assist, and support residents in the publication of clinical case studies; and clinical teachers should encourage graduate students to publish case reports during their graduate medical education.

Introduction

Case reports and case series or case study research are descriptive studies to present patients in their natural clinical setting. Case reports, which generally consist of three or fewer patients, are prepared to illustrate features in the practice of medicine and potentially create new research questions that may contribute to the acquisition of additional knowledge in the literature. Case studies involve multiple patients; they are a qualitative research method and include in-depth analyses or experiential inquiries of a person or group in their real-world setting. Case study research focuses on the contextual analysis of several events or conditions and their relationships [ 1 ]. In addition to their teaching value for students and graduate medical education programs, case reports provide a starting point for novice investigators, which may prepare and encourage them to seek more contextual writing experiences for future research investigation. It may also provide senior physicians with clues about emerging epidemics or a recognition of previously unrecognized syndromes. Limitations primarily involve the lack of generalizability and implications in clinical practice, which are factors extraneous to the learning model (Table (Table1 1 ).

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| One case to initiate a signal (case report) | No control (uncontrolled) |

| Provide stronger evidence with multiple cases (cases series) | Difficult to compare different cases |

| Observational | Cases may not be generalizable |

| Educational | Selection bias |

| Easy to do (fast and no financial support needed) | Unknown future outcome/follow-up |

| Identify rare manifestations of a disease or drug |

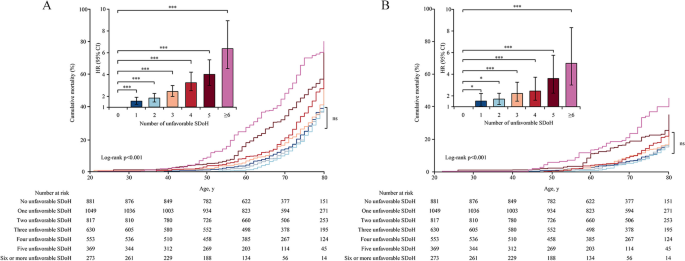

There is disagreement among physicians on the value of case reports in the medical literature and in evidence-based medicine (EBM) [ 2 ]. EBM aims to optimize decision-making by using evidence from well-conducted research. Therefore, not all data has the same value as the evidence. The pyramid (Figure (Figure1) 1 ) classifies publications based on their study outlines and according to the power of evidence they provide [ 2 - 3 ]. In the classical pyramid represented below, systematic reviews and a meta-analysis are expected to provide the strongest evidence. However, a recent modification of the pyramid was suggested by Murad et al. [ 2 ]: the meta-analysis and systematic reviews are removed from the pyramid and are suggested to be a lens through which evidence is viewed (Figure 1 ).

Modified from Murad et al. [ 2 ]

Because case reports do not rank highly in the hierarchy of evidence and are not frequently cited, as they describe the clinical circumstances of single patients, they are seldom published by high-impact medical journals. However, case reports are proposed to have significant educational value because they advance medical knowledge and constitute evidence for EBM. In addition, well-developed publication resources can be difficult to find, especially for medical residents; those that do exist vary in quality and may not be suitable for the aim and scope of the journals. Over the last several years, a number (approximately 160) of new peer-reviewed journals that focus on publishing case reports have emerged. These are mostly open-access journals with considerably high acceptance rates [ 4 ]. Packer et al. reported a 6% publication rate for case reports [ 5 ]; however, they did not disclose the number of papers submitted but rejected and neither did they state whether any of the reported cases were submitted to open-access journals.

The development of open-access journals has created a new venue for students and faculty to publish. In contrast to subscription-based and peer-reviewed e-journals, many of these new case report journals are not adequately reviewed and, instead, have a questionably high acceptance rate [ 4 ]. There, however, remains the issue of the fee-based publication of case reports in open-access journals without proper peer reviews, which increases the burden of scientific literature. Trainees should be made aware of the potential for academic dilution, particularly with some open-access publishers. While case reports with high-quality peer reviews are associated with a relatively low acceptance rate, this rigorous process introduces trainees to the experience and expectations of peer reviews and addresses other issues or flaws not considered prior to submission. We believe that these are important skills that should be emphasized and experienced during training, and authors should seek these journals for the submission of their manuscripts.

Importance of Case Reports and Case Series in Graduate Medical Education

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has challenged faculties to adapt teaching methodologies to accommodate the different learning modalities of the next generation of physicians. As evidenced by its implementation by ACGME, competency-based medical education is rapidly gaining international acceptance, moving from classic didactic lectures to self-directed learning opportunities with experiential learning aids in the development of critical cognitive and scholarly skills. As graduate medical educators, we are in agreement with Packer et al. about the value of the educational benefits resulting from student-generated case reports [ 5 ]. Case study assignments help residents develop a variety of key skills, as previously described. EBM is an eventual decision-making process for executing the most appropriate treatment approach by using the tools that are compatible with the national health policy, medical evidence, and the personal factors of physician and patient (Figure (Figure2). The 2 ). The practice of identifying and developing a case study creates a learning opportunity for listening skills and appreciation for the patient’s narrative as well as for developing critical learning and thinking skills that are directly applicable to the practice of EBM. This critically important process simultaneously enhances both the medical and the humanistic importance of physician-patient interaction. In addition, case-based learning is an active learner-centered approach for medical students and residents. It serves as a curricular context, which can promote the retention of information and evidence-based thinking.

Modified from Toklu et al. 2015 [ 3 ]

The value of case studies in the medical literature is controversial among physicians. Despite their limitations, clinical case reports and case series are beneficial tools in graduate medical education. The preparation and presentation of case studies can help students and residents acquire and apply clinical competencies in the areas of medical knowledge, practice-based learning, systems-based practice, professionalism, and communication. In this aspect, case studies provide a tool for developing clinical skills through problem-based learning methods. As a result, journals should encourage the publication of clinical case studies from graduate medical education programs through a commonly applied peer-review process, and clinical teachers should promote medical residents to publish case reports during their graduate medical education.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Health Case Studies

(29 reviews)

Glynda Rees, British Columbia Institute of Technology

Rob Kruger, British Columbia Institute of Technology

Janet Morrison, British Columbia Institute of Technology

Copyright Year: 2017

Publisher: BCcampus

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Jessica Sellars, Medical assistant office instructor, Blue Mountain Community College on 10/11/23

This is a book of compiled and very well organized patient case studies. The author has broken it up by disease patient was experiencing and even the healthcare roles that took place in this patients care. There is a well thought out direction and... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

This is a book of compiled and very well organized patient case studies. The author has broken it up by disease patient was experiencing and even the healthcare roles that took place in this patients care. There is a well thought out direction and plan. There is an appendix to refer to as well if you are needing to find something specific quickly. I have been looking for something like this to help my students have a base to do their project on. This is the most comprehensive version I have found on the subject.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

This is a book compiled of medical case studies. It is very accurate and can be used to learn from great care and mistakes.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

This material is very relevant in this context. It also has plenty of individual case studies to utilize in many ways in all sorts of medical courses. This is a very useful textbook and it will continue to be useful for a very long time as you can still learn from each study even if medicine changes through out the years.

Clarity rating: 5

The author put a lot of thought into the ease of accessibility and reading level of the target audience. There is even a "how to use this resource" section which could be extremely useful to students.

Consistency rating: 5

The text follows a very consistent format throughout the book.

Modularity rating: 5

Each case study is individual broken up and in a group of similar case studies. This makes it extremely easy to utilize.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

The book is very organized and the appendix is through. It flows seamlessly through each case study.

Interface rating: 5

I had no issues navigating this book, It was clearly labeled and very easy to move around in.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

I did not catch any grammar errors as I was going through the book

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

This is a challenging question for any medical textbook. It is very culturally relevant to those in medical or medical office degrees.

I have been looking for something like this for years. I am so happy to have finally found it.

Reviewed by Cindy Sun, Assistant Professor, Marshall University on 1/7/23

Interestingly, this is not a case of ‘you get what you pay for’. Instead, not only are the case studies organized in a fashion for ease of use through a detailed table of contents, the authors have included more support for both faculty and... read more

Interestingly, this is not a case of ‘you get what you pay for’. Instead, not only are the case studies organized in a fashion for ease of use through a detailed table of contents, the authors have included more support for both faculty and students. For faculty, the introduction section titled ‘How to use this resource’ and individual notes to educators before each case study contain application tips. An appendix overview lists key elements as issues / concepts, scenario context, and healthcare roles for each case study. For students, learning objectives are presented at the beginning of each case study to provide a framework of expectations.

The content is presented accurately and realistic.

The case studies read similar to ‘A Day In the Life of…’ with detailed intraprofessional communications similar to what would be overheard in patient care areas. The authors present not only the view of the patient care nurse, but also weave interprofessional vantage points through each case study by including patient interaction with individual professionals such as radiology, physician, etc.

In addition to objective assessment findings, the authors integrate standard orders for each diagnosis including medications, treatments, and tests allowing the student to incorporate pathophysiology components to their assessments.

Each case study is arranged in the same framework for consistency and ease of use.

This compilation of eight healthcare case studies focusing on new onset and exacerbation of prevalent diagnoses, such as heart failure, deep vein thrombosis, cancer, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease advancing to pneumonia.

Each case study has a photo of the ‘patient’. Simple as this may seem, it gives an immediate mental image for the student to focus.

Interface rating: 4

As noted by previous reviewers, most of the links do not connect active web pages. This may be due to the multiple options for accessing this resource (pdf download, pdf electronic, web view, etc.).

Grammatical Errors rating: 4

A minor weakness that faculty will probably need to address prior to use is regarding specific term usages differences between Commonwealth countries and United States, such as lung sound descriptors as ‘quiet’ in place of ‘diminished’ and ‘puffers’ in place of ‘inhalers’.

The authors have provided a multicultural, multigenerational approach in selection of patient characteristics representing a snapshot of today’s patient population. Additionally, one case study focusing on heart failure is about a middle-aged adult, contrasting to the average aged patient the students would normally see during clinical rotations. This option provides opportunities for students to expand their knowledge on risk factors extending beyond age.

This resource is applicable to nursing students learning to care for patients with the specific disease processes presented in each case study or for the leadership students focusing on intraprofessional communication. Educators can assign as a supplement to clinical experiences or as an in-class application of knowledge.

Reviewed by Stephanie Sideras, Assistant Professor, University of Portland on 8/15/22

The eight case studies included in this text addressed high frequency health alterations that all nurses need to be able to manage competently. While diabetes was not highlighted directly, it was included as a potential comorbidity. The five... read more

The eight case studies included in this text addressed high frequency health alterations that all nurses need to be able to manage competently. While diabetes was not highlighted directly, it was included as a potential comorbidity. The five overarching learning objectives pulled from the Institute of Medicine core competencies will clearly resonate with any faculty familiar with Quality and Safety Education for Nurses curriculum.

The presentation of symptoms, treatments and management of the health alterations was accurate. Dialogue between the the interprofessional team was realistic. At times the formatting of lab results was confusing as they reflected reference ranges specific to the Canadian healthcare system but these occurrences were minimal and could be easily adapted.

The focus for learning from these case studies was communication - patient centered communication and interprofessional team communication. Specific details, such as drug dosing, was minimized, which increases longevity and allows for easy individualization of the case data.

While some vocabulary was specific to the Canadian healthcare system, overall the narrative was extremely engaging and easy to follow. Subjective case data from patient or provider were formatted in italics and identified as 'thoughts'. Objective and behavioral case data were smoothly integrated into the narrative.

The consistency of formatting across the eight cases was remarkable. Specific learning objectives are identified for each case and these remain consistent across the range of cases, varying only in the focus for the goals for each different health alterations. Each case begins with presentation of essential patient background and the progress across the trajectory of illness as the patient moves from location to location encountering different healthcare professionals. Many of the characters (the triage nurse in the Emergency Department, the phlebotomist) are consistent across the case situations. These consistencies facilitate both application of a variety of teaching methods and student engagement with the situated learning approach.

Case data is presented by location and begins with the patient's first encounter with the healthcare system. This allows for an examination of how specific trajectories of illness are manifested and how care management needs to be prioritized at different stages. This approach supports discussions of care transitions and the complexity of the associated interprofessional communication.

The text is well organized. The case that has two levels of complexity is clearly identified

The internal links between the table of contents and case specific locations work consistently. In the EPUB and the Digital PDF the external hyperlinks are inconsistently valid.

The grammatical errors were minimal and did not detract from readability

Cultural diversity is present across the cases in factors including race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, family dynamics and sexual orientation.

The level of detail included in these cases supports a teaching approach to address all three spectrums of learning - knowledge, skills and attitudes - necessary for the development of competent practice. I also appreciate the inclusion of specific assessment instruments that would facilitate a discussion of evidence based practice. I will enjoy using these case to promote clinical reasoning discussions of data that is noticed and interpreted with the resulting prioritizes that are set followed by reflections that result from learner choices.

Reviewed by Chris Roman, Associate Professor, Butler University on 5/19/22

It would be extremely difficult for a book of clinical cases to comprehensively cover all of medicine, and this text does not try. Rather, it provides cases related to common medical problems and introduces them in a way that allows for various... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

It would be extremely difficult for a book of clinical cases to comprehensively cover all of medicine, and this text does not try. Rather, it provides cases related to common medical problems and introduces them in a way that allows for various learning strategies to be employed to leverage the cases for deeper student learning and application.

The narrative form of the cases is less subject to issues of accuracy than a more content-based book would be. That said, the cases are realistic and reasonable, avoiding being too mundane or too extreme.

These cases are narrative and do not include many specific mentions of drugs, dosages, or other aspects of clinical care that may grow/evolve as guidelines change. For this reason, the cases should be “evergreen” and can be modified to suit different types of learners.

Clarity rating: 4

The text is written in very accessible language and avoids heavy use of technical language. Depending on the level of learner, this might even be too simplistic and omit some details that would be needed for physicians, pharmacists, and others to make nuanced care decisions.

The format is very consistent with clear labeling at transition points.

The authors point out in the introductory materials that this text is designed to be used in a modular fashion. Further, they have built in opportunities to customize each cases, such as giving dates of birth at “19xx” to allow for adjustments based on instructional objectives, etc.

The organization is very easy to follow.

I did not identify any issues in navigating the text.

The text contains no grammatical errors, though the language is a little stiff/unrealistic in some cases.

Cases involve patients and members of the care team that are of varying ages, genders, and racial/ethnic backgrounds

Reviewed by Trina Larery, Assistant Professor, Pittsburg State University on 4/5/22

The book covers common scenarios, providing allied health students insight into common health issues. The information in the book is thorough and easily modified if needed to include other scenarios not listed. The material was easy to understand... read more

The book covers common scenarios, providing allied health students insight into common health issues. The information in the book is thorough and easily modified if needed to include other scenarios not listed. The material was easy to understand and apply to the classroom. The E-reader format included hyperlinks that bring the students to subsequent clinical studies.

Content Accuracy rating: 4

The treatments were explained and rationales were given, which can be very helpful to facilitate effective learning for a nursing student or novice nurse. The case studies were accurate in explanation. The DVT case study incorrectly identifies the location of the clot in the popliteal artery instead of in the vein.

The content is relevant to a variety of different types of health care providers and due to the general nature of the cases, will remain relevant over time. Updates should be made annually to the hyperlinks and to assure current standard of practice is still being met.

Clear, simple and easy to read.

Consistent with healthcare terminology and framework throughout all eight case studies.

The text is modular. Cases can be used individually within a unit on the given disease process or relevant sections of a case could be used to illustrate a specific point providing great flexibility. The appendix is helpful in locating content specific to a certain diagnosis or a certain type of health care provider.

The book is well organized, presenting in a logical clear fashion. The appendix allows the student to move about the case study without difficulty.

The interface is easy and simple to navigate. Some links to external sources might need to be updated regularly since those links are subject to change based on current guidelines. A few hyperlinks had "page not found".

Few grammatical errors were noted in text.

The case studies include people of different ethnicities, socioeconomic status, ages, and genders to make this a very useful book.

I enjoyed reading the text. It was interesting and relevant to today's nursing student. There are roughly 25 broken online links or "pages not found", care needs to be taken to update at least annually and assure links are valid and utilizing the most up to date information.

Reviewed by Benjamin Silverberg, Associate Professor/Clinician, West Virginia University on 3/24/22

The appendix reviews the "key roles" and medical venues found in all 8 cases, but is fairly spartan on medical content. The table of contents at the beginning only lists the cases and locations of care. It can be a little tricky to figure out what... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 3 see less

The appendix reviews the "key roles" and medical venues found in all 8 cases, but is fairly spartan on medical content. The table of contents at the beginning only lists the cases and locations of care. It can be a little tricky to figure out what is going on where, especially since each case is largely conversation-based. Since this presents 8 cases (really 7 with one being expanded upon), there are many medical topics (and venues) that are not included. It's impossible to include every kind of situation, but I'd love to see inclusion of sexual health, renal pathology, substance abuse, etc.

Though there are differences in how care can be delivered based on personal style, changing guidelines, available supplies, etc, the medical accuracy seems to be high. I did not detect bias or industry influence.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

Medications are generally listed as generics, with at least current dosing recommendations. The text gives a picture of what care looks like currently, but will be a little challenging to update based on new guidelines (ie, it can be hard to find the exact page in which a medication is dosed/prescribed). Even if the text were to be a little out of date, an instructor can use that to point out what has changed (and why).

Clear text, usually with definitions of medical slang or higher-tier vocabulary. Minimal jargon and there are instances where the "characters" are sorting out the meaning as well, making it accessible for new learners, too.

Overall, the style is consistent between cases - largely broken up into scenes and driven by conversation rather than descriptions of what is happening.

There are 8 (well, again, 7) cases which can be reviewed in any order. Case #2 builds upon #1, which is intentional and a good idea, though personally I would have preferred one case to have different possible outcomes or even a recurrence of illness. Each scene within a case is reasonably short.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

These cases are modular and don't really build on concepts throughout. As previously stated, case #2 builds upon #1, but beyond that, there is no progression. (To be sure, the authors suggest using case #1 for newer learners and #2 for more advanced ones.) The text would benefit from thematic grouping, a longer introduction and debriefing for each case (there are learning objectives but no real context in medical education nor questions to reflect on what was just read), and progressively-increasing difficulty in medical complexity, ethics, etc.

I used the PDF version and had no interface issues. There are minimal photographs and charts. Some words are marked in blue but those did not seem to be hyperlinked anywhere.

No noticeable errors in grammar, spelling, or formatting were noted.

I appreciate that some diversity of age and ethnicity were offered, but this could be improved. There were Canadian Indian and First Nations patients, for example, as well as other characters with implied diversity, but there didn't seem to be any mention of gender diverse or non-heterosexual people, or disabilities. The cases tried to paint family scenes (the first patient's dog was fairly prominently mentioned) to humanize them. Including more cases would allow for more opportunities to include sex/gender minorities, (hidden) disabilities, etc.

The text (originally from 2017) could use an update. It could be used in conjunction with other Open Texts, as a compliment to other coursework, or purely by itself. The focus is meant to be on improving communication, but there are only 3 short pages at the beginning of the text considering those issues (which are really just learning objectives). In addition to adding more cases and further diversity, I personally would love to see more discussion before and after the case to guide readers (and/or instructors). I also wonder if some of the ambiguity could be improved by suggesting possible health outcomes - this kind of counterfactual comparison isn't possible in real life and could be really interesting in a text. Addition of comprehension/discussion questions would also be worthwhile.

Reviewed by Danielle Peterson, Assistant Professor, University of Saint Francis on 12/31/21

This text provides readers with 8 case studies which include both chronic and acute healthcare issues. Although not comprehensive in regard to types of healthcare conditions, it provides a thorough look at the communication between healthcare... read more

This text provides readers with 8 case studies which include both chronic and acute healthcare issues. Although not comprehensive in regard to types of healthcare conditions, it provides a thorough look at the communication between healthcare workers in acute hospital settings. The cases are primarily set in the inpatient hospital setting, so the bulk of the clinical information is basic emergency care and inpatient protocol: vitals, breathing, medication management, etc. The text provides a table of contents at opening of the text and a handy appendix at the conclusion of the text that outlines each case’s issue(s), scenario, and healthcare roles. No index or glossary present.

Although easy to update, it should be noted that the cases are taking place in a Canadian healthcare system. Terms may be unfamiliar to some students including “province,” “operating theatre,” “physio/physiotherapy,” and “porter.” Units of measurement used include Celsius and meters. Also, the issue of managed care, health insurance coverage, and length of stay is missing for American students. These are primary issues that dictate much of the healthcare system in the US and a primary job function of social workers, nurse case managers, and medical professionals in general. However, instructors that wish to add this to the case studies could do so easily.

The focus of this text is on healthcare communication which makes it less likely to become obsolete. Much of the clinical information is stable healthcare practice that has been standard of care for quite some time. Nevertheless, given the nature of text, updates would be easy to make. Hyperlinks should be updated to the most relevant and trustworthy sources and checked frequently for effectiveness.

The spacing that was used to note change of speaker made for ease of reading. Although unembellished and plain, I expect students to find this format easy to digest and interesting, especially since the script is appropriately balanced with ‘human’ qualities like the current TV shows and songs, the use of humor, and nonverbal cues.

A welcome characteristic of this text is its consistency. Each case is presented in a similar fashion and the roles of the healthcare team are ‘played’ by the same character in each of the scenarios. This allows students to see how healthcare providers prioritize cases and juggle the needs of multiple patients at once. Across scenarios, there was inconsistency in when clinical terms were hyperlinked.

The text is easily divisible into smaller reading sections. However, since the nature of the text is script-narrative format, if significant reorganization occurs, one will need to make sure that the communication of the script still makes sense.

The text is straightforward and presented in a consistent fashion: learning objectives, case history, a script of what happened before the patient enters the healthcare setting, and a script of what happens once the patient arrives at the healthcare setting. The authors use the term, “ideal interactions,” and I would agree that these cases are in large part, ‘best case scenarios.’ Due to this, the case studies are well organized, clear, logical, and predictable. However, depending on the level of student, instructors may want to introduce complications that are typical in the hospital setting.

The interface is pleasing and straightforward. With exception to the case summary and learning objectives, the cases are in narrative, script format. Each case study supplies a photo of the ‘patient’ and one of the case studies includes a link to a 3-minute video that introduces the reader to the patient/case. One of the highlights of this text is the use of hyperlinks to various clinical practices (ABG, vital signs, transfer of patient). Unfortunately, a majority of the links are broken. However, since this is an open text, instructors can update the links to their preference.

Although not free from grammatical errors, those that were noticed were minimal and did not detract from reading.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

Cultural diversity is visible throughout the patients used in the case studies and includes factors such as age, race, socioeconomic status, family dynamics, and sexual orientation. A moderate level of diversity is noted in the healthcare team with some stereotypes: social workers being female, doctors primarily male.

As a social work instructor, I was grateful to find a text that incorporates this important healthcare role. I would have liked to have seen more content related to advance directives, mediating decision making between the patient and care team, emotional and practical support related to initial diagnosis and discharge planning, and provision of support to colleagues, all typical roles of a medical social worker. I also found it interesting that even though social work was included in multiple scenarios, the role was only introduced on the learning objectives page for the oncology case.

Reviewed by Crystal Wynn, Associate Professor, Virginia State University on 7/21/21

The text covers a variety of chronic diseases within the cases; however, not all of the common disease states were included within the text. More chronic diseases need to be included such as diabetes, cancer, and renal failure. Not all allied... read more

The text covers a variety of chronic diseases within the cases; however, not all of the common disease states were included within the text. More chronic diseases need to be included such as diabetes, cancer, and renal failure. Not all allied health care team members are represented within the case study. Key terms appear throughout the case study textbook and readers are able to click on a hyperlink which directs them to the definition and an explanation of the key term.

Content is accurate, error-free and unbiased.

The content is up-to-date, but not in a way that will quickly make the text obsolete within a short period of time. The text is written and/or arranged in such a way that necessary updates will be relatively easy and straightforward to implement.

The text is written in lucid, accessible prose, and provides adequate context for any jargon/technical terminology used

The text is internally consistent in terms of terminology and framework.

The text is easily and readily divisible into smaller reading sections that can be assigned at different points within the course. Each case can be divided into a chronic disease state unit, which will allow the reader to focus on one section at a time.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 3

The topics in the text are presented in a logical manner. Each case provides an excessive amount of language that provides a description of the case. The cases in this text reads more like a novel versus a clinical textbook. The learning objectives listed within each case should be in the form of questions or activities that could be provided as resources for instructors and teachers.

Interface rating: 3

There are several hyperlinks embedded within the textbook that are not functional.

The text contains no grammatical errors.

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

The text is not culturally insensitive or offensive in any way. More examples of cultural inclusiveness is needed throughout the textbook. The cases should be indicative of individuals from a variety of races and ethnicities.

Reviewed by Rebecca Hillary, Biology Instructor, Portland Community College on 6/15/21

This textbook consists of a collection of clinical case studies that can be applicable to a wide range of learning environments from supplementing an undergraduate Anatomy and Physiology Course, to including as part of a Medical or other health... read more

This textbook consists of a collection of clinical case studies that can be applicable to a wide range of learning environments from supplementing an undergraduate Anatomy and Physiology Course, to including as part of a Medical or other health care program. I read the textbook in E-reader format and this includes hyperlinks that bring the students to subsequent clinical study if the book is being used in a clinical classroom. This book is significantly more comprehensive in its approach from other case studies I have read because it provides a bird’s eye view of the many clinicians, technicians, and hospital staff working with one patient. The book also provides real time measurements for patients that change as they travel throughout the hospital until time of discharge.

Each case gave an accurate sense of the chaos that would be present in an emergency situation and show how the conditions affect the practitioners as well as the patients. The reader gets an accurate big picture--a feel for each practitioner’s point of view as well as the point of view of the patient and the patient’s family as the clock ticks down and the patients are subjected to a number of procedures. The clinical information contained in this textbook is all in hyperlinks containing references to clinical skills open text sources or medical websites. I did find one broken link on an external medical resource.

The diseases presented are relevant and will remain so. Some of the links are directly related to the Canadian Medical system so they may not be applicable to those living in other regions. Clinical links may change over time but the text itself will remain relevant.

Each case study clearly presents clinical data as is it recorded in real time.

Each case study provides the point of view of several practitioners and the patient over several days. While each of the case studies covers different pathology they all follow this same format, several points of view and data points, over a number of days.

The case studies are divided by days and this was easy to navigate as a reader. It would be easy to assign one case study per body system in an Anatomy and Physiology course, or to divide them up into small segments for small in class teaching moments.

The topics are presented in an organized way showing clinical data over time and each case presents a large number of view points. For example, in the first case study, the patient is experiencing difficulty breathing. We follow her through several days from her entrance to the emergency room. We meet her X Ray Technicians, Doctor, Nurses, Medical Assistant, Porter, Physiotherapist, Respiratory therapist, and the Lab Technicians running her tests during her stay. Each practitioner paints the overall clinical picture to the reader.

I found the text easy to navigate. There were not any figures included in the text, only clinical data organized in charts. The figures were all accessible via hyperlink. Some figures within the textbook illustrating patient scans could have been helpful but I did not have trouble navigating the links to visualize the scans.

I did not see any grammatical errors in the text.

The patients in the text are a variety of ages and have a variety of family arrangements but there is not much diversity among the patients. Our seven patients in the eight case studies are mostly white and all cis gendered.

Some of the case studies, for example the heart failure study, show clinical data before and after drug treatments so the students can get a feel for mechanism in physiological action. I also liked that the case studies included diet and lifestyle advice for the patients rather than solely emphasizing these pharmacological interventions. Overall, I enjoyed reading through these case studies and I plan to utilize them in my Anatomy and Physiology courses.

Reviewed by Richard Tarpey, Assistant Professor, Middle Tennessee State University on 5/11/21

As a case study book, there is no index or glossary. However, medical and technical terms provide a useful link to definitions and explanations that will prove useful to students unfamiliar with the terms. The information provided is appropriate... read more

As a case study book, there is no index or glossary. However, medical and technical terms provide a useful link to definitions and explanations that will prove useful to students unfamiliar with the terms. The information provided is appropriate for entry-level health care students. The book includes important health problems, but I would like to see coverage of at least one more chronic/lifestyle issue such as diabetes. The book covers adult issues only.

Content is accurate without bias

The content of the book is relevant and up-to-date. It addresses conditions that are prevalent in today's population among adults. There are no pediatric cases, but this does not significantly detract from the usefulness of the text. The format of the book lends to easy updating of data or information.

The book is written with clarity and is easy to read. The writing style is accessible and technical terminology is explained with links to more information.

Consistency is present. Lack of consistency is typically a problem with case study texts, but this book is consistent with presentation, format, and terminology throughout each of the eight cases.

The book has high modularity. Each of the case studies can be used independently from the others providing flexibility. Additionally, each case study can be partitioned for specific learning objectives based on the learning objectives of the course or module.

The book is well organized, presenting students conceptually with differing patient flow patterns through a hospital. The patient information provided at the beginning of each case is a wonderful mechanism for providing personal context for the students as they consider the issues. Many case studies focus on the problem and the organization without students getting a patient's perspective. The patient perspective is well represented in these cases.

The navigation through the cases is good. There are some terminology and procedure hyperlinks within the cases that do not work when accessed. This is troubling if you intend to use the text for entry-level health care students since many of these links are critical for a full understanding of the case.

There are some non-US variants of spelling and a few grammatical errors, but these do not detract from the content of the messages of each case.

The book is inclusive of differing backgrounds and perspectives. No insensitive or offensive references were found.

I like this text for its application flexibility. The book is useful for non-clinical healthcare management students to introduce various healthcare-related concepts and terminology. The content is also helpful for the identification of healthcare administration managerial issues for students to consider. The book has many applications.

Reviewed by Paula Baldwin, Associate Professor/Communication Studies, Western Oregon University on 5/10/21

The different case studies fall on a range, from crisis care to chronic illness care. read more

The different case studies fall on a range, from crisis care to chronic illness care.

The contents seems to be written as they occurred to represent the most complete picture of each medical event's occurence.

These case studies are from the Canadian medical system, but that does not interfere with it's applicability.

It is written for a medical audience, so the terminology is mostly formal and technical.

Some cases are shorter than others and some go in more depth, but it is not problematic.

The eight separate case studies is the perfect size for a class in the quarter system. You could combine this with other texts, videos or learning modalities, or use it alone.

As this is a case studies book, there is not a need for a logical progression in presentation of topics.

No problems in terms of interface.

I have not seen any grammatical errors.

I did not see anything that was culturally insensitive.

I used this in a Health Communication class and it has been extraordinarily successful. My studies are analyzing the messaging for the good, the bad, and the questionable. The case studies are widely varied and it gives the class insights into hospital experiences, both front and back stage, that they would not normally be able to examine. I believe that because it is based real-life medical incidents, my students are finding the material highly engaging.

Reviewed by Marlena Isaac, Instructor, Aiken Technical College on 4/23/21

This text is great to walk through patient care with entry level healthcare students. The students are able to take in the information, digest it, then provide suggestions to how they would facilitate patient healing. Then when they are faced with... read more

This text is great to walk through patient care with entry level healthcare students. The students are able to take in the information, digest it, then provide suggestions to how they would facilitate patient healing. Then when they are faced with a situation in clinical they are not surprised and now how to move through it effectively.

The case studies provided accurate information that relates to the named disease.

It is relevant to health care studies and the development of critical thinking.

Cases are straightforward with great clinical information.

Clinical information is provided concisely.

Appropriate for clinical case study.

Presented to facilitate information gathering.

Takes a while to navigate in the browser.

Cultural Relevance rating: 1

Text lacks adequate representation of minorities.

Reviewed by Kim Garcia, Lecturer III, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley on 11/16/20

The book has 8 case studies, so obviously does not cover the whole of medicine, but the cases provided are descriptive and well developed. Cases are presented at different levels of difficulty, making the cases appropriate for students at... read more

The book has 8 case studies, so obviously does not cover the whole of medicine, but the cases provided are descriptive and well developed. Cases are presented at different levels of difficulty, making the cases appropriate for students at different levels of clinical knowledge. The human element of both patient and health care provider is well captured. The cases are presented with a focus on interprofessional interaction and collaboration, more so than teaching medical content.

Content is accurate and un-biased. No errors noted. Most diagnostic and treatment information is general so it will remain relevant over time. The content of these cases is more appropriate for teaching interprofessional collaboration and less so for teaching the medical care for each diagnosis.

The content is relevant to a variety of different types of health care providers (nurses, radiologic technicians, medical laboratory personnel, etc) and due to the general nature of the cases, will remain relevant over time.

Easy to read. Clear headings are provided for sections of each case study and these section headings clearly tell when time has passed or setting has changed. Enough description is provided to help set the scene for each part of the case. Much of the text is written in the form of dialogue involving patient, family and health care providers, making it easy to adapt for role play. Medical jargon is limited and links for medical terms are provided to other resources that expound on medical terms used.

The text is consistent in structure of each case. Learning objectives are provided. Cases generally start with the patient at home and move with the patient through admission, testing and treatment, using a variety of healthcare services and encountering a variety of personnel.

The text is modular. Cases could be used individually within a unit on the given disease process or relevant sections of a case could be used to illustrate a specific point. The appendix is helpful in locating content specific to a certain diagnosis or a certain type of health care provider.

Each case follows a patient in a logical, chronologic fashion. A clear table of contents and appendix are provided which allows the user to quickly locate desired content. It would be helpful if the items in the table of contents and appendix were linked to the corresponding section of the text.

The hyperlinks to content outside this book work, however using the back arrow on your browser returns you to the front page of the book instead of to the point at which you left the text. I would prefer it if the hyperlinks opened in a new window or tab so closing that window or tab would leave you back where you left the text.

No grammatical errors were noted.

The text is culturally inclusive and appropriate. Characters, both patients and care givers are of a variety of races, ethnicities, ages and backgrounds.

I enjoyed reading the cases and reviewing this text. I can think of several ways in which I will use this content.

Reviewed by Raihan Khan, Instructor/Assistant Professor, James Madison University on 11/3/20

The book contains several important health issues, however still missing some chronic health issues that the students should learn before they join the workforce, such as diabetes-related health issues suffered by the patients. read more

The book contains several important health issues, however still missing some chronic health issues that the students should learn before they join the workforce, such as diabetes-related health issues suffered by the patients.

The health information contained in the textbook is mostly accurate.

I think the book is written focusing on the current culture and health issues faced by the patients. To keep the book relevant in the future, the contexts especially the culture/lifestyle/health care modalities, etc. would need to be updated regularly.

The language is pretty simple, clear, and easy to read.

There is no complaint about consistency. One of the main issues of writing a book, consistency was well managed by the authors.

The book is easy to explore based on how easy the setup is. Students can browse to the specific section that they want to read without much hassle of finding the correct information.

The organization is simple but effective. The authors organized the book based on what can happen in a patient's life and what possible scenarios students should learn about the disease. From that perspective, the book does a good job.

The interface is easy and simple to navigate. Some links to external sources might need to be updated regularly since those links are subject to change that is beyond the author's control. It's frustrating for the reader when the external link shows no information.

The book is free of any major language and grammatical errors.

The book might do a little better in cultural competency. e.g. Last name Singh is mainly for Sikh people. In the text Harj and Priya Singh are Muslim. the authors can consult colleagues who are more familiar with those cultures and revise some cultural aspects of the cases mentioned in the book.

The book is a nice addition to the open textbook world. Hope to see more health issues covered by the book.

Reviewed by Ryan Sheryl, Assistant Professor, California State University, Dominguez Hills on 7/16/20

This text contains 8 medical case studies that reflect best practices at the time of publication. The text identifies 5 overarching learning objectives: interprofessional collaboration, client centered care, evidence-based practice, quality... read more

This text contains 8 medical case studies that reflect best practices at the time of publication. The text identifies 5 overarching learning objectives: interprofessional collaboration, client centered care, evidence-based practice, quality improvement, and informatics. While the case studies do not cover all medical conditions or bodily systems, the book is thorough in conveying details of various patients and medical team members in a hospital environment. Rather than an index or glossary at the end of the text, it contains links to outside websites for more information on medical tests and terms referenced in the cases.

The content provided is reflective of best practices in patient care, interdisciplinary collaboration, and communication at the time of publication. It is specifically accurate for the context of hospitals in Canada. The links provided throughout the text have the potential to supplement with up-to-date descriptions and definitions, however, many of them are broken (see notes in Interface section).

The content of the case studies reflects the increasingly complex landscape of healthcare, including a variety of conditions, ages, and personal situations of the clients and care providers. The text will require frequent updating due to the rapidly changing landscape of society and best practices in client care. For example, a future version may include inclusive practices with transgender clients, or address ways medical racism implicitly impacts client care (see notes in Cultural Relevance section).

The text is written clearly and presents thorough, realistic details about working and being treated in an acute hospital context.

The text is very straightforward. It is consistent in its structure and flow. It uses consistent terminology and follows a structured framework throughout.

Being a series of 8 separate case studies, this text is easily and readily divisible into smaller sections. The text was designed to be taken apart and used piece by piece in order to serve various learning contexts. The parts of each case study can also be used independently of each other to facilitate problem solving.

The topics in the case studies are presented clearly. The structure of each of the case studies proceeds in a similar fashion. All of the cases are set within the same hospital so the hospital personnel and service providers reappear across the cases, giving a textured portrayal of the experiences of the various service providers. The cases can be used individually, or one service provider can be studied across the various studies.

The text is very straightforward, without complex charts or images that could become distorted. Many of the embedded links are broken and require updating. The links that do work are a very useful way to define and expand upon medical terms used in the case studies.

Grammatical errors are minimal and do not distract from the flow of the text. In one instance the last name Singh is spelled Sing, and one patient named Fred in the text is referred to as Frank in the appendix.

The cases all show examples of health care personnel providing compassionate, client-centered care, and there is no overt discrimination portrayed. Two of the clients are in same-sex marriages and these are shown positively. It is notable, however, that the two cases presenting people of color contain more negative characteristics than the other six cases portraying Caucasian people. The people of color are the only two examples of clients who smoke regularly. In addition, the Indian client drinks and is overweight, while the First Nations client is the only one in the text to have a terminal diagnosis. The Indian client is identified as being Punjabi and attending a mosque, although there are only 2% Muslims in the Punjab province of India. Also, the last name Singh generally indicates a person who is a Hindu or Sikh, not Muslim.

Reviewed by Monica LeJeune, RN Instructor, LSUE on 4/24/20

Has comprehensive unfolding case studies that guide the reader to recognize and manage the scenario presented. Assists in critical thinking process. read more

Has comprehensive unfolding case studies that guide the reader to recognize and manage the scenario presented. Assists in critical thinking process.

Accurately presents health scenarios with real life assessment techniques and patient outcomes.

Relevant to nursing practice.

Clearly written and easily understood.

Consistent with healthcare terminology and framework

Has a good reading flow.

Topics presented in logical fashion

Easy to read.

No grammatical errors noted.

Text is not culturally insensitive or offensive.

Good book to have to teach nursing students.

Reviewed by april jarrell, associate professor, J. Sargeant Reynolds Community College on 1/7/20

The text is a great case study tool that is appropriate for nursing school instructors to use in aiding students to learn the nursing process. read more

The text is a great case study tool that is appropriate for nursing school instructors to use in aiding students to learn the nursing process.

The content is accurate and evidence based. There is no bias noted

The content in the text is relevant, up to date for nursing students. It will be easy to update content as needed because the framework allows for addition to the content.

The text is clear and easy to understand.

Framework and terminology is consistent throughout the text; the case study is a continual and takes the student on a journey with the patient. Great for learning!

The case studies can be easily divided into smaller sections to allow for discussions, and weekly studies.

The text and content progress in a logical, clear fashion allowing for progression of learning.

No interface issues noted with this text.

No grammatical errors noted in the text.

No racial or culture insensitivity were noted in the text.

I would recommend this text be used in nursing schools. The use of case studies are helpful for students to learn and practice the nursing process.

Reviewed by Lisa Underwood, Practical Nursing Instructor, NTCC on 12/3/19

The text provides eight comprehensive case studies that showcase the different viewpoints of the many roles involved in patient care. It encompasses the most common seen diagnoses seen across healthcare today. Each case study comes with its own... read more

The text provides eight comprehensive case studies that showcase the different viewpoints of the many roles involved in patient care. It encompasses the most common seen diagnoses seen across healthcare today. Each case study comes with its own set of learning objectives that can be tweaked to fit several allied health courses. Although the case studies are designed around the Canadian Healthcare System, they are quite easily adaptable to fit most any modern, developed healthcare system.

Content Accuracy rating: 3

Overall, the text is quite accurate. There is one significant error that needs to be addressed. It is located in the DVT case study. In the study, a popliteal artery clot is mislabeled as a DVT. DVTs are located in veins, not in arteries. That said, the case study on the whole is quite good. This case study could be used as a learning tool in the classroom for discussion purposes or as a way to test student understanding of DVTs, on example might be, "Can they spot the error?"

At this time, all of the case studies within the text are current. Healthcare is an ever evolving field that rests on the best evidence based practice. Keeping that in mind, educators can easily adapt the studies as the newest evidence emerges and changes practice in healthcare.

All of the case studies are well written and easy to understand. The text includes several hyperlinks and it also highlights certain medical terminology to prompt readers as a way to enhance their learning experience.

Across the text, the language, style, and format of the case studies are completely consistent.

The text is divided into eight separate case studies. Each case study may be used independently of the others. All case studies are further broken down as the focus patient passes through each aspect of their healthcare system. The text's modularity makes it possible to use a case study as individual work, group projects, class discussions, homework or in a simulation lab.

The case studies and the diagnoses that they cover are presented in such a way that educators and allied health students can easily follow and comprehend.

The book in itself is free of any image distortion and it prints nicely. The text is offered in a variety of digital formats. As noted in the above reviews, some of the hyperlinks have navigational issues. When the reader attempts to access them, a "page not found" message is received.

There were minimal grammatical errors. Some of which may be traced back to the differences in our spelling.

The text is culturally relevant in that it includes patients from many different backgrounds and ethnicities. This allows educators and students to explore cultural relevance and sensitivity needs across all areas in healthcare. I do not believe that the text was in any way insensitive or offensive to the reader.

By using the case studies, it may be possible to have an open dialogue about the differences noted in healthcare systems. Students will have the ability to compare and contrast the Canadian healthcare system with their own. I also firmly believe that by using these case studies, students can improve their critical thinking skills. These case studies help them to "put it all together".

Reviewed by Melanie McGrath, Associate Professor, TRAILS on 11/29/19

The text covered some of the most common conditions seen by healthcare providers in a hospital setting, which forms a solid general base for the discussions based on each case. read more

The text covered some of the most common conditions seen by healthcare providers in a hospital setting, which forms a solid general base for the discussions based on each case.

I saw no areas of inaccuracy

As in all healthcare texts, treatments and/or tests will change frequently. However, everything is currently up-to-date thus it should be a good reference for several years.

Each case is written so that any level of healthcare student would understand. Hyperlinks in the text is also very helpful.

All of the cases are written in a similar fashion.

Although not structured as a typical text, each case is easily assigned as a stand-alone.

Each case is organized clearly in an appropriate manner.

I did not see any issues.

I did not see any grammatical errors

The text seemed appropriately inclusive. There are no pediatric cases and no cases of intellectually-impaired patients, but those types of cases introduce more advanced problem-solving which perhaps exceed the scope of the text. May be a good addition to the text.

I found this text to be an excellent resource for healthcare students in a variety of fields. It would be best utilized in inter professional courses to help guide discussion.

Reviewed by Lynne Umbarger, Clinical Assistant Professor, Occupational Therapy, Emory and Henry College on 11/26/19

While the book does not cover every scenario, the ones in the book are quite common and troublesome for inexperienced allied health students. The information in the book is thorough enough, and I have found the cases easy to modify for educational... read more

While the book does not cover every scenario, the ones in the book are quite common and troublesome for inexperienced allied health students. The information in the book is thorough enough, and I have found the cases easy to modify for educational purposes. The material was easily understood by the students but challenging enough for classroom discussion. There are no mentions in the book about occupational therapy, but it is easy enough to add a couple words and make inclusion simple.

Very nice lab values are provided in the case study, making it more realistic for students.

These case studies focus on commonly encountered diagnoses for allied health and nursing students. They are comprehensive, realistic, and easily understood. The only difference is that the hospital in one case allows the patient's dog to visit in the room (highly unusual in US hospitals).

The material is easily understood by allied health students. The cases have links to additional learning materials for concepts that may be less familiar or should be explored further in a particular health field.

The language used in the book is consistent between cases. The framework is the same with each case which makes it easier to locate areas that would be of interest to a particular allied health profession.

The case studies are comprehensive but well-organized. They are short enough to be useful for class discussion or a full-blown assignment. The students seem to understand the material and have not expressed that any concepts or details were missing.

Each case is set up like the other cases. There are learning objectives at the beginning of each case to facilitate using the case, and it is easy enough to pull out material to develop useful activities and assignments.

There is a quick chart in the Appendix to allow the reader to determine the professions involved in each case as well as the pertinent settings and diagnoses for each case study. The contents are easy to access even while reading the book.

As a person who attends carefully to grammar, I found no errors in all of the material I read in this book.

There are a greater number of people of different ethnicities, socioeconomic status, ages, and genders to make this a very useful book. With each case, I could easily picture the person in the case. This book appears to be Canadian and more inclusive than most American books.

I was able to use this book the first time I accessed it to develop a classroom activity for first-year occupational therapy students and a more comprehensive activity for second-year students. I really appreciate the links to a multitude of terminology and medical lab values/issues for each case. I will keep using this book.

Reviewed by Cindy Krentz, Assistant Professor, Metropolitan State University of Denver on 6/15/19

The book covers eight case studies of common inpatient or emergency department scenarios. I appreciated that they had written out the learning objectives. I liked that the patient was described before the case was started, giving some... read more

The book covers eight case studies of common inpatient or emergency department scenarios. I appreciated that they had written out the learning objectives. I liked that the patient was described before the case was started, giving some understanding of the patient's background. I think it could benefit from having a glossary. I liked how the authors included the vital signs in an easily readable bar. I would have liked to see the labs also highlighted like this. I also felt that it would have been good written in a 'what would you do next?' type of case study.

The book is very accurate in language, what tests would be prudent to run and in the day in the life of the hospital in all cases. One inaccuracy is that the authors called a popliteal artery clot a DVT. The rest of the DVT case study was great, though, but the one mistake should be changed.

The book is up to date for now, but as tests become obsolete and new equipment is routinely used, the book ( like any other health textbook) will need to be updated. It would be easy to change, however. All that would have to happen is that the authors go in and change out the test to whatever newer, evidence-based test is being utilized.

The text is written clearly and easy to understand from a student's perspective. There is not too much technical jargon, and it is pretty universal when used- for example DVT for Deep Vein Thrombosis.

The book is consistent in language and how it is broken down into case studies. The same format is used for highlighting vital signs throughout the different case studies. It's great that the reader does not have to read the book in a linear fashion. Each case study can be read without needing to read the others.

The text is broken down into eight case studies, and within the case studies is broken down into days. It is consistent and shows how the patient can pass through the different hospital departments (from the ER to the unit, to surgery, to home) in a realistic manner. The instructor could use one or more of the case studies as (s)he sees fit.

The topics are eight different case studies- and are presented very clearly and organized well. Each one is broken down into how the patient goes through the system. The text is easy to follow and logical.

The interface has some problems with the highlighted blue links. Some of them did not work and I got a 'page not found' message. That can be frustrating for the reader. I'm wondering if a glossary could be utilized (instead of the links) to explain what some of these links are supposed to explain.

I found two or three typos, I don't think they were grammatical errors. In one case I think the Canadian spelling and the United States spelling of the word are just different.

This is a very culturally competent book. In today's world, however, one more type of background that would merit delving into is the trans-gender, GLBTQI person. I was glad that there were no stereotypes.

I enjoyed reading the text. It was interesting and relevant to today's nursing student. Since we are becoming more interprofessional, I liked that we saw what the phlebotomist and other ancillary personnel (mostly different technicians) did. I think that it could become even more interdisciplinary so colleges and universities could have more interprofessional education- courses or simulations- with the addition of the nurse using social work, nutrition, or other professional health care majors.

Reviewed by Catherine J. Grott, Interim Director, Health Administration Program, TRAILS on 5/5/19

The book is comprehensive but is specifically written for healthcare workers practicing in Canada. The title of the book should reflect this. read more

The book is comprehensive but is specifically written for healthcare workers practicing in Canada. The title of the book should reflect this.

The book is accurate, however it has numerous broken online links.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 3

The content is very relevant, but some links are out-dated. For example, WHO Guidelines for Safe Surgery 2009 (p. 186) should be updated.

The book is written in clear and concise language. The side stories about the healthcare workers make the text interesting.

The book is consistent in terms of terminology and framework. Some terms that are emphasized in one case study are not emphasized (with online links) in the other case studies. All of the case studies should have the same words linked to online definitions.

Modularity rating: 3

The book can easily be parsed out if necessary. However, the way the case studies have been written, it's evident that different authors contributed singularly to each case study.

The organization and flow are good.

Interface rating: 1

There are numerous broken online links and "pages not found."

The grammar and punctuation are correct. There are two errors detected: p. 120 a space between the word "heart" and the comma; also a period is needed after Dr (p. 113).

I'm not quite sure that the social worker (p. 119) should comment that the patient and partner are "very normal people."

There are roughly 25 broken online links or "pages not found." The BC & Canadian Guidelines (p. 198) could also include a link to US guidelines to make the text more universal . The basilar crackles (p. 166) is very good. Text could be used compare US and Canadian healthcare. Text could be enhanced to teach "soft skills" and interdepartmental communication skills in healthcare.

Reviewed by Lindsey Henry, Practical Nursing Instructor, Fletcher on 5/1/19

I really appreciated how in the introduction, five learning objectives were identified for students. These objectives are paramount in nursing care and they are each spelled out for the learner. Each Case study also has its own learning... read more

I really appreciated how in the introduction, five learning objectives were identified for students. These objectives are paramount in nursing care and they are each spelled out for the learner. Each Case study also has its own learning objectives, which were effectively met in the readings.

As a seasoned nurse, I believe that the content regarding pathophysiology and treatments used in the case studies were accurate. I really appreciated how many of the treatments were also explained and rationales were given, which can be very helpful to facilitate effective learning for a nursing student or novice nurse.

The case studies are up to date and correlate with the current time period. They are easily understood.

I really loved how several important medical terms, including specific treatments were highlighted to alert the reader. Many interventions performed were also explained further, which is great to enhance learning for the nursing student or novice nurse. Also, with each scenario, a background and history of the patient is depicted, as well as the perspectives of the patient, patients family member, and the primary nurse. This really helps to give the reader a full picture of the day in the life of a nurse or a patient, and also better facilitates the learning process of the reader.

These case studies are consistent. They begin with report, the patient background or updates on subsequent days, and follow the patients all the way through discharge. Once again, I really appreciate how this book describes most if not all aspects of patient care on a day to day basis.

Each case study is separated into days. While they can be divided to be assigned at different points within the course, they also build on each other. They show trends in vital signs, what happens when a patient deteriorates, what happens when they get better and go home. Showing the entire process from ER admit to discharge is really helpful to enhance the students learning experience.

The topics are all presented very similarly and very clearly. The way that the scenarios are explained could even be understood by a non-nursing student as well. The case studies are very clear and very thorough.

The book is very easy to navigate, prints well on paper, and is not distorted or confusing.

I did not see any grammatical errors.

Each case study involves a different type of patient. These differences include race, gender, sexual orientation and medical backgrounds. I do not feel the text was offensive to the reader.

I teach practical nursing students and after reading this book, I am looking forward to implementing it in my classroom. Great read for nursing students!

Reviewed by Leah Jolly, Instructor, Clinical Coordinator, Oregon Institute of Technology on 4/10/19

Good variety of cases and pathologies covered. read more

Good variety of cases and pathologies covered.

Content Accuracy rating: 2

Some examples and scenarios are not completely accurate. For example in the DVT case, the sonographer found thrombus in the "popliteal artery", which according to the book indicated presence of DVT. However in DVT, thrombus is located in the vein, not the artery. The patient would also have much different symptoms if located in the artery. Perhaps some of these inaccuracies are just typos, but in real-life situations this simple mistake can make a world of difference in the patient's course of treatment and outcomes.

Good examples of interprofessional collaboration. If only it worked this way on an every day basis!

Clear and easy to read for those with knowledge of medical terminology.

Good consistency overall.

Broken up well.

Topics are clear and logical.

Would be nice to simply click through to the next page, rather than going through the table of contents each time.