Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- Product Demos

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

- Artificial Intelligence

- Market Research

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

- Experience Management

- What is a survey?

- Close-ended Questions

Try Qualtrics for free

Close-ended questions: everything you need to know.

7 min read In this guide, find out how you can use close-ended survey questions to gather quantifiable data and gain easy-to-analyze survey responses.

What is a close-ended question?

If you want to collect survey responses within a limited frame of options, close-ended questions (also closed-ended questions) and their question types are critical.

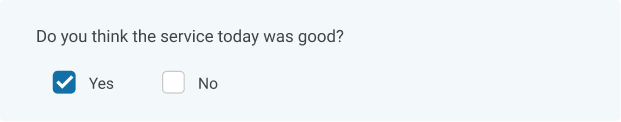

Close-ended questions ask respondents to choose from a predefined set of responses, typically one-word answers such as “yes/no”, “true/false”, or a set of multiple-choice questions.

For example: “Is the sky blue?” and the respondent then has to choose “Yes/No”.

The purpose of close-ended questions is to gather focused, quantitative data — numbers, dates, or a one-word answer — from respondents as it’s easy to group, compare and analyze.

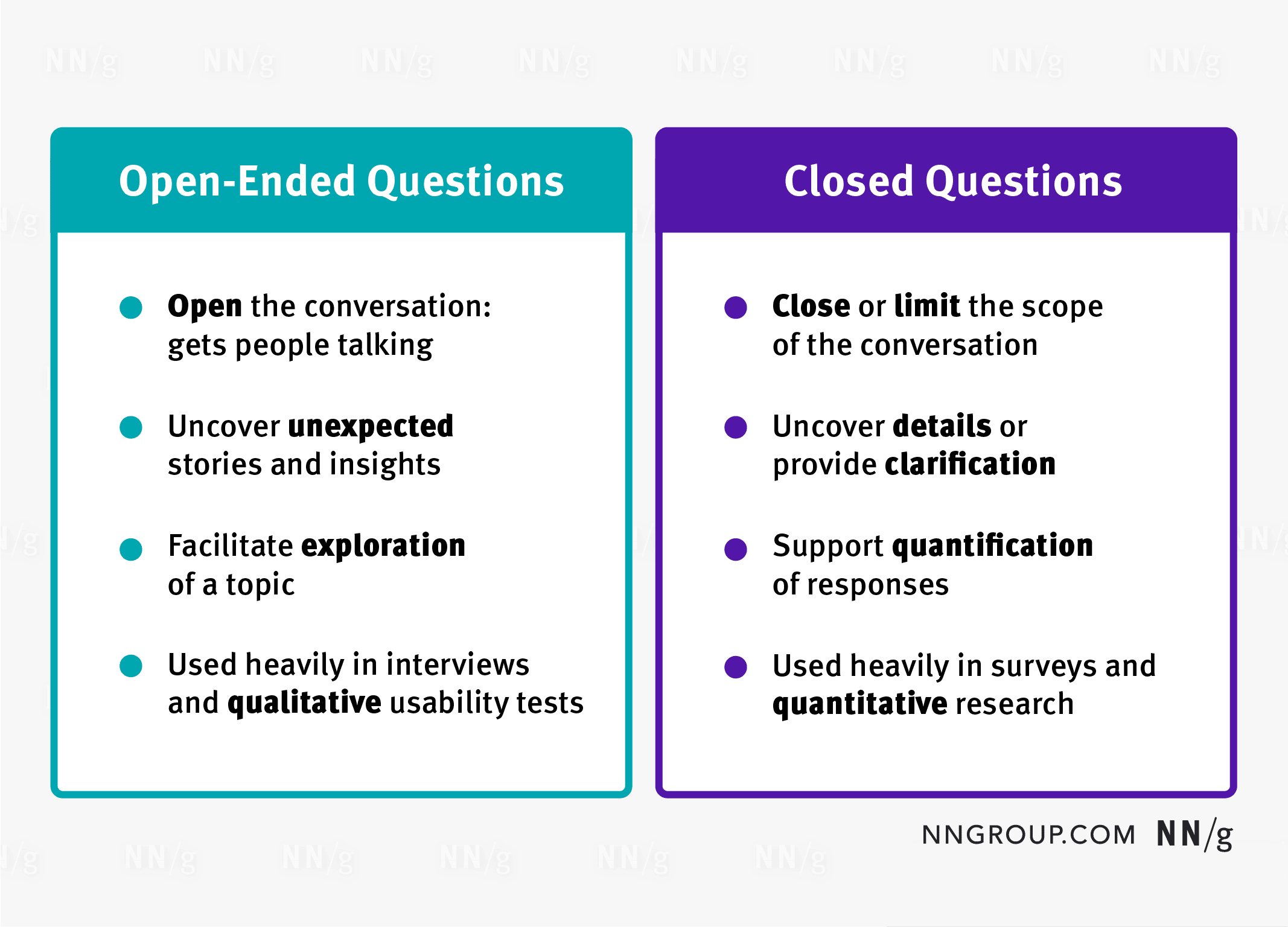

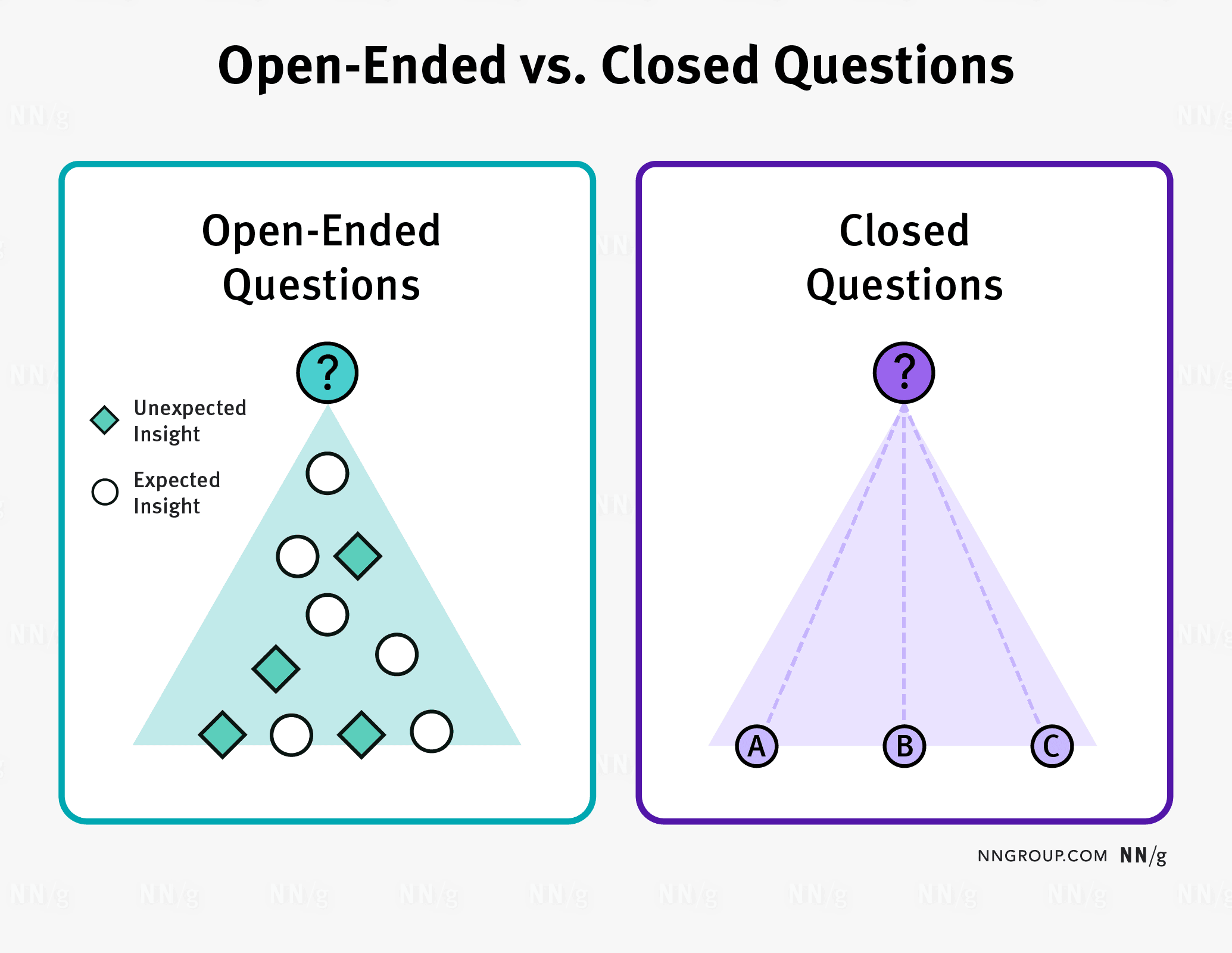

Also, researchers use close-ended questions because the results are statistically significant and help to show trends and percentages over time. Open-ended questions, on the other hand, provide qualitative data: information that helps you to understand your customers and the context behind their actions.

Ebook: The Qualtrics Handbook of Question Design

A close-ended vs open-ended question

Here are the main differences between open and closed-ended questions:

| Open-ended questions | Closed-ended questions |

|---|---|

| Qualitative | Quantitative |

| Contextual | Data-driven |

| Personalized | Manufactured |

| Exploratory | Focused |

More on open-ended questions

Open-ended questions are survey questions that begin with ‘who / what / where / when / why/ how’. Because there are no fixed responses, respondents have the freedom to answer in their own words — leading to more authentic and meaningful insights for researchers to leverage.

See below the differences between an open and a close-ended question:

Open-ended question requesting qualitative data

What are you feeling right now?

close-ended question requesting quantitative data

On a scale of 1-10 (where 1 is feeling terrible and 10 is feeling amazing), how are you feeling right now?

Both provide data, but the information differs based on the question (what are you feeling versus a numerical scale). With this in mind, researchers can design surveys that are fit-for-purpose depending on requirements.

However, best practice is to use a combination of open and close-ended survey questions. You might start with a close-ended question and follow up with an open-ended one so that respondents can explain their answers.

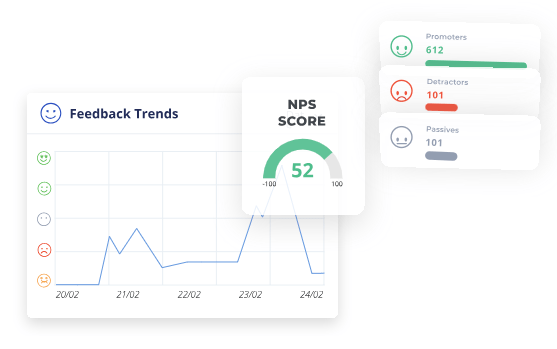

For example, if you’re curious about your company’s Net Promoter Score (NPS) , you could run a survey that includes these two questions:

- “How likely are you to recommend this product/service on a scale from 0 to 10?” (close-ended question) followed by:

- “Why have you responded this way?” (open-ended question)

This provides both quantitative and qualitative research data — so researchers have the numerical data but also the stories that contextualize how people answer.

Now, let’s look at the advantages and disadvantages of close-ended survey questions for collecting data.

Business advantages to using close-ended questions

- Easier and quicker to answer thanks to pre-populated answer choices.

- Provides measurable and statistically significant stats (quantitative data) that’s easy to analyze

- Gives better understanding of the question through answer options

- Higher response rates (respondents can quickly answer questions)

- Gets rid of irrelevant answers (as they are predetermined)

- Gives answers and data that is easy to compare

- They’re easy to customize

- You can categorize respondents based on answer choices

Business disadvantages to using close-ended questions

- Lacks detailed information (context)

- Can’t get customer opinions or comments (qualitative data)

- Doesn’t cover all possible answers and options

- Choices can often create confusion

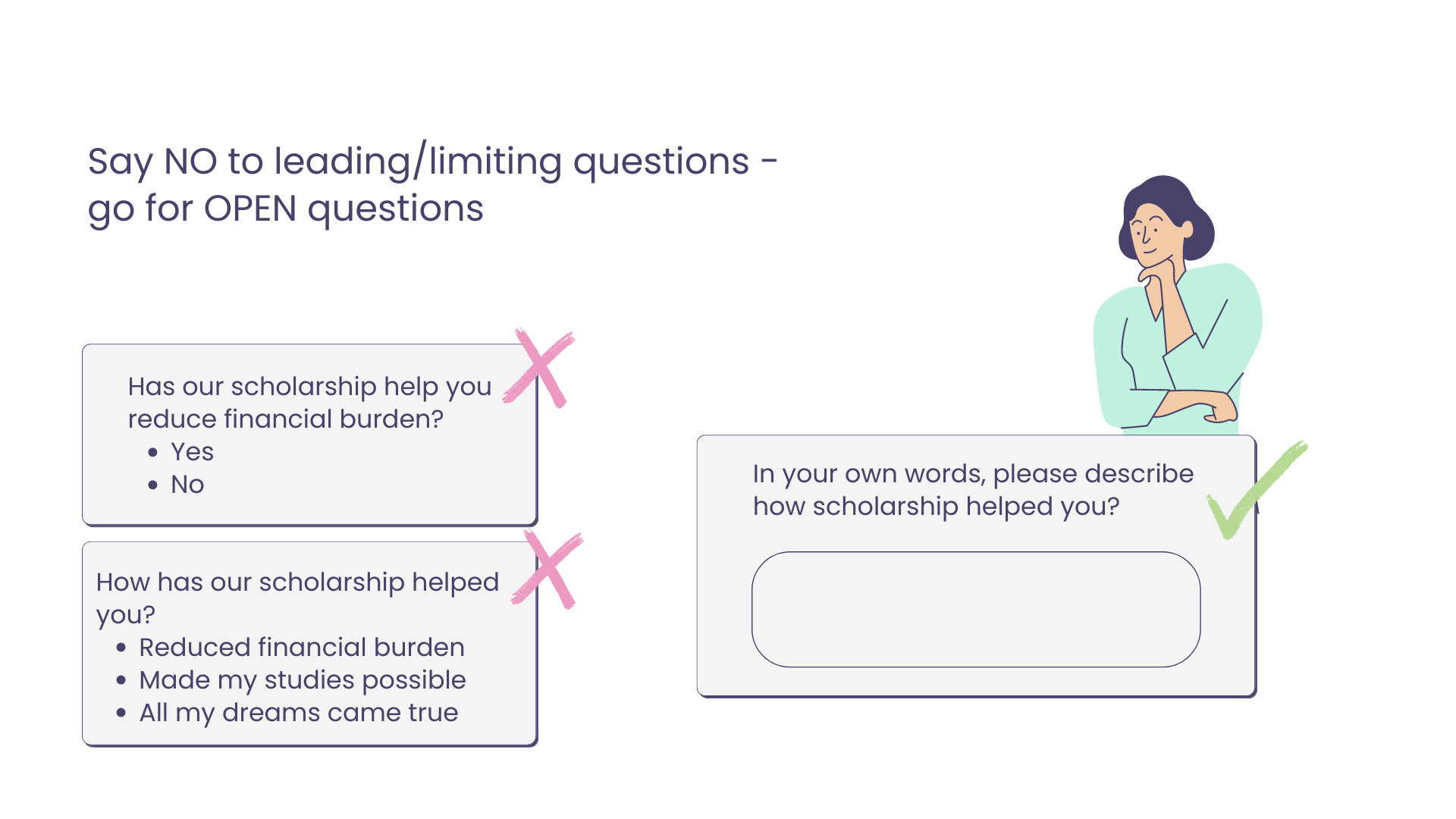

- Are sometimes suggestive and therefore leads to bias

- No neutral option for those who don’t have an answer

Having highlighted the advantages and disadvantages of close-ended survey questions for user research, what types of close-ended questions can you use to collect data?

Types of closed questions

Dichotomous questions.

These question types have two options as answers (Di = two or split), which ask the survey participant for a single-word answer. These include:

- True or False

- Agree or Disagree

For example:

- Are you thirsty? Yes or No

- Is the sky blue? True or False

- Is stealing bad? Agree or Disagree.

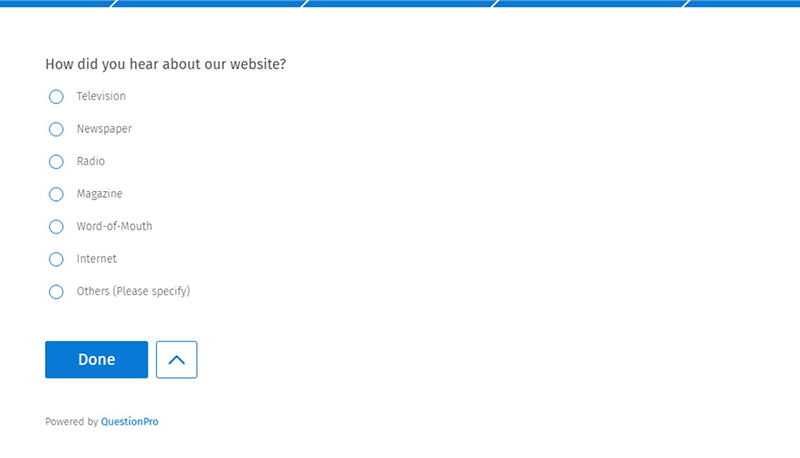

Multiple-choice questions

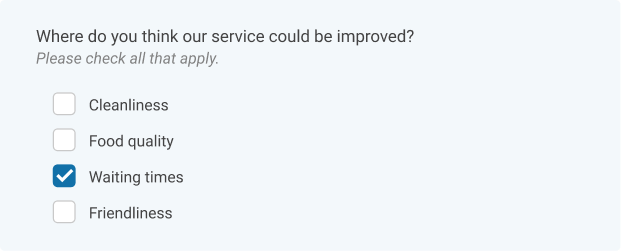

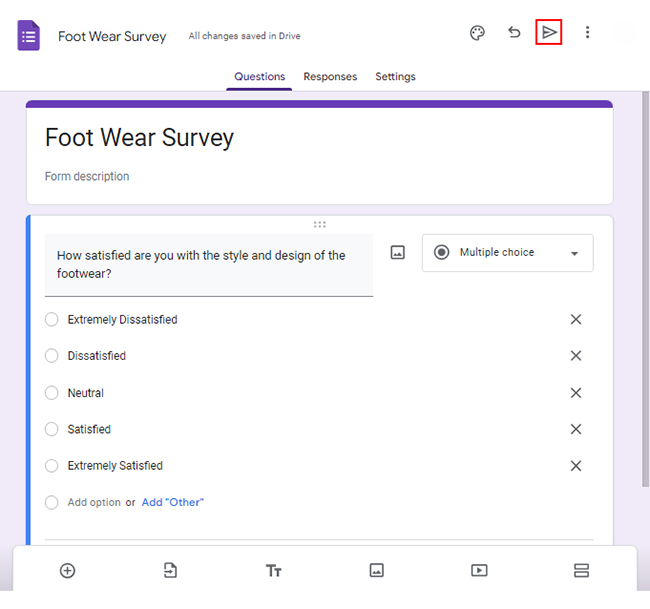

Multiple-choice questions form the basis of most research. These questions have several options and are usually displayed as a list of choices, a dropdown menu, or a select box.

Multiple-choice questions also come in different formats:

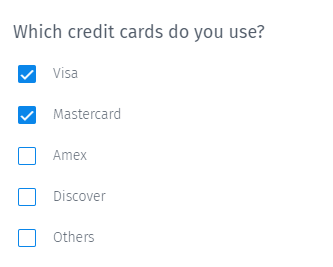

- Multi-select: Multi-select is used when you want participants to select more than one answer from a list.

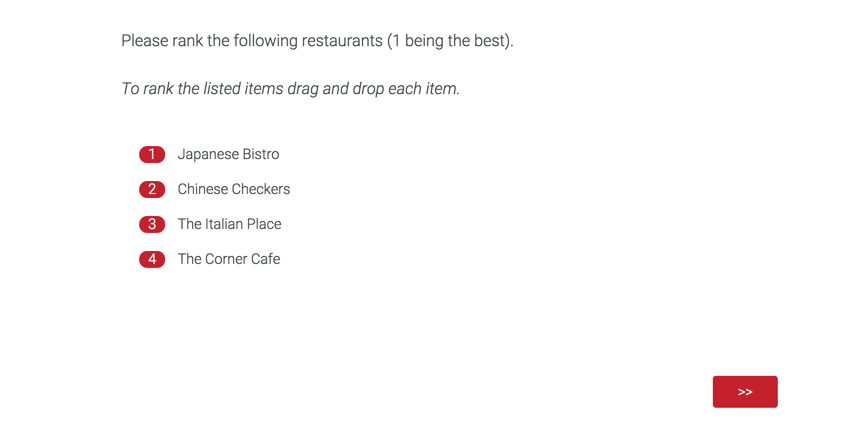

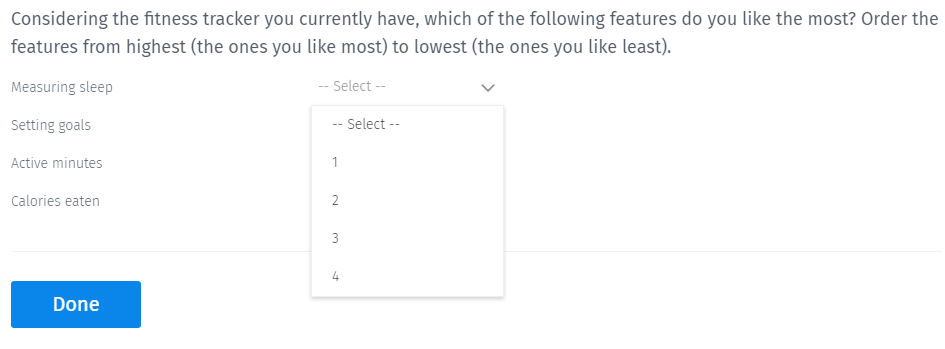

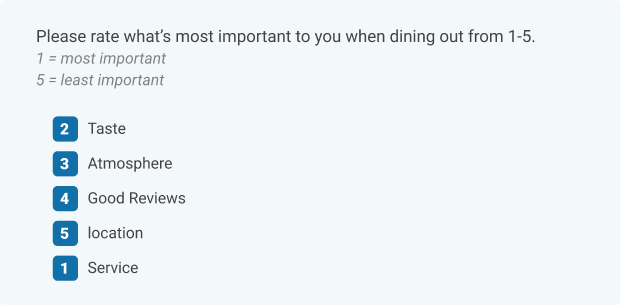

- Ranking order: Rank order is used to determine the order of preference for a list of items. This question type is best for measuring your respondents’ attitudes toward something.

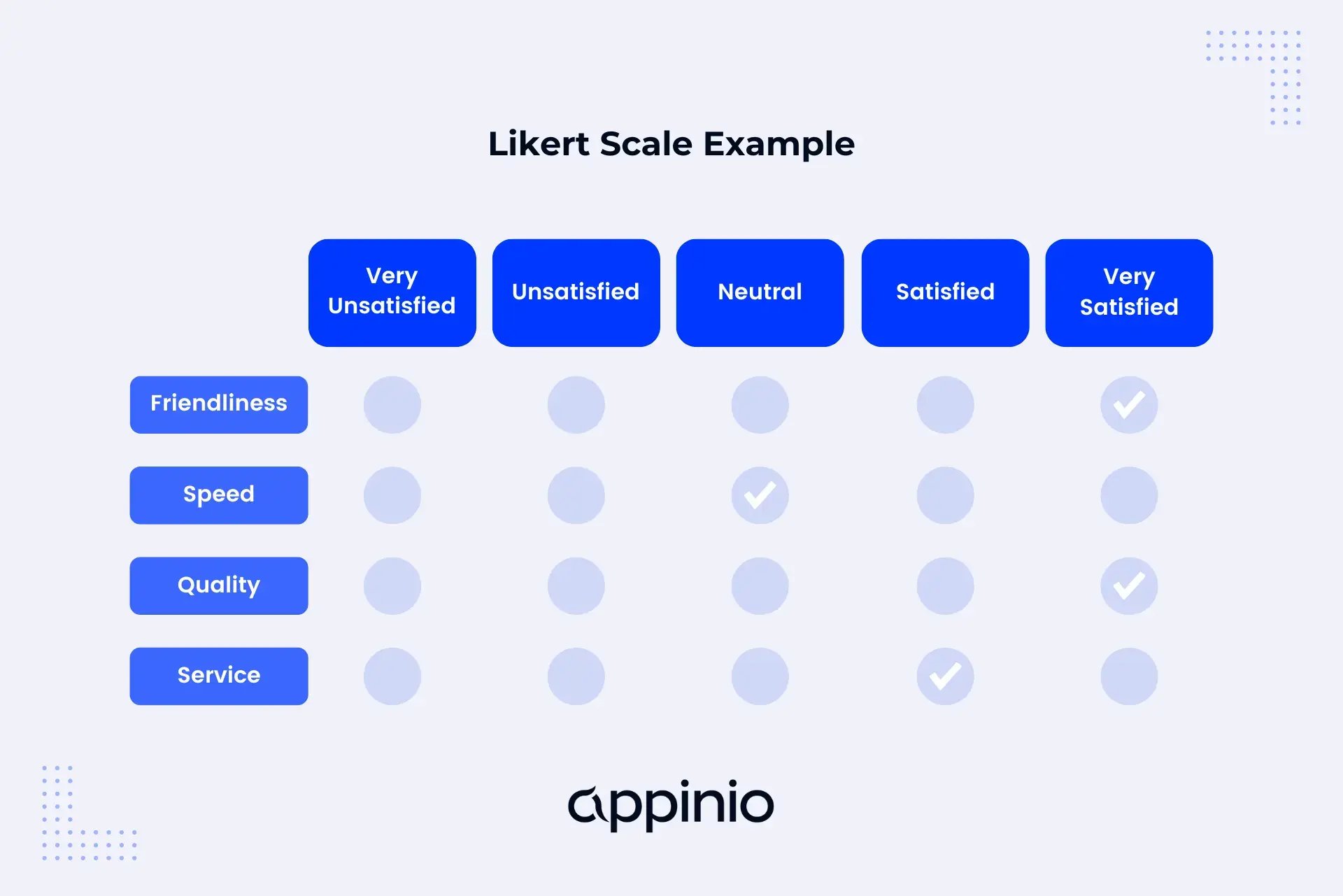

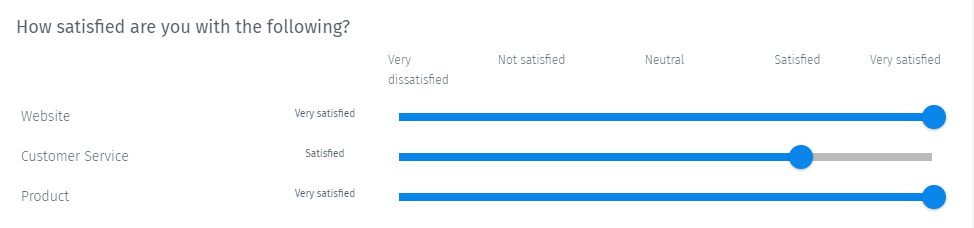

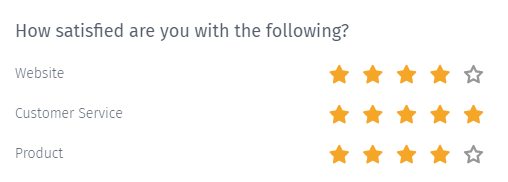

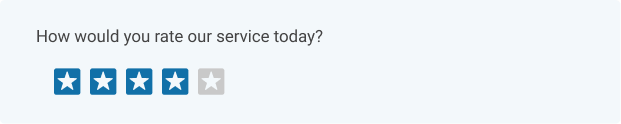

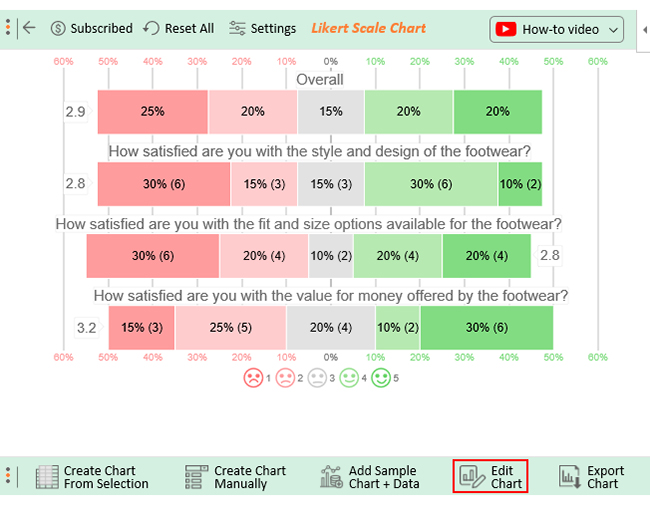

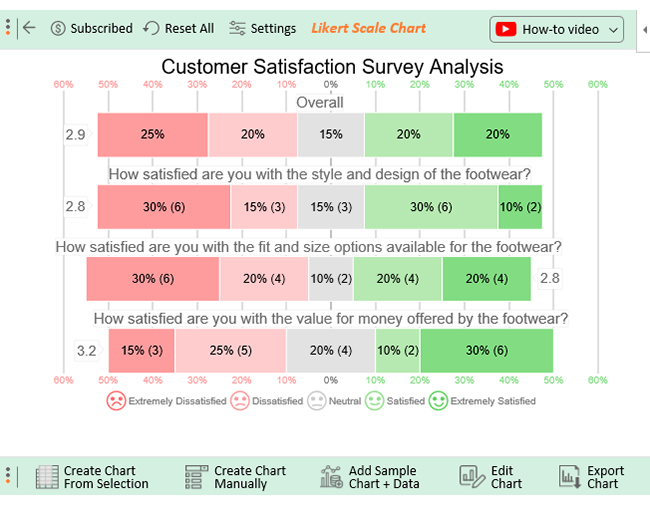

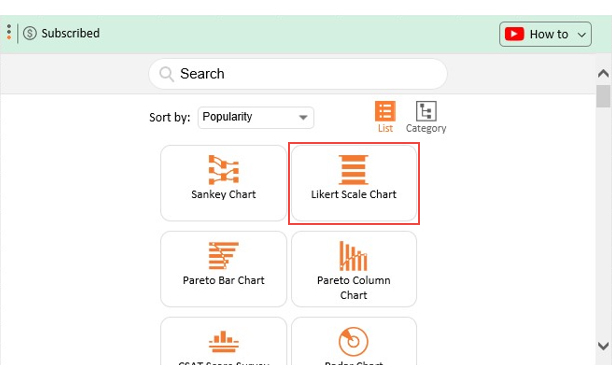

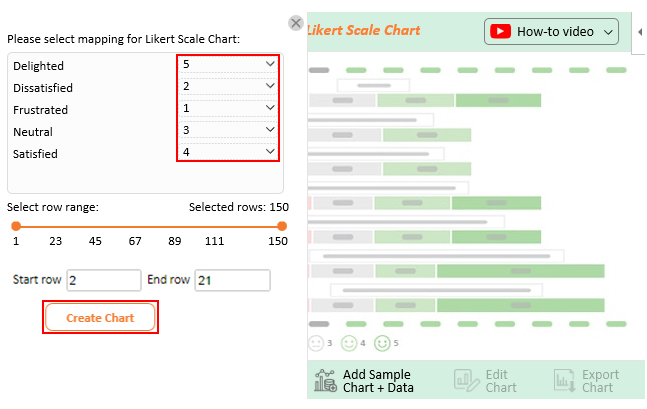

- Rating order or rating scale: Rating questions ask respondents to indicate their levels for aspects such as agreement, satisfaction, or frequency. An example is a Likert scale.

- Matrix table: Matrix questions collect multiple pieces of information in one question. This type provides an effective way to condense your survey or to group similar items into one question.

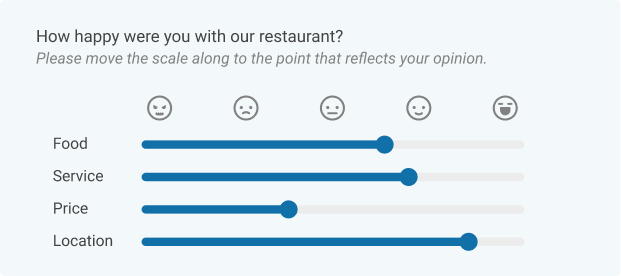

- Sliders: Sliders let respondents indicate their level of preference with a draggable bar rather than a traditional button or checkbox.

- Simple, direct, comprehensible

- Jargon-free

- Specific and concrete (rather than general and abstract)

- Unambiguous

- Not double-barreled

- Positive, not negative

- Not leading

- Include filter questions

- Easy to read aloud

- Not emotionally charged

- Inclusive of all possible responses

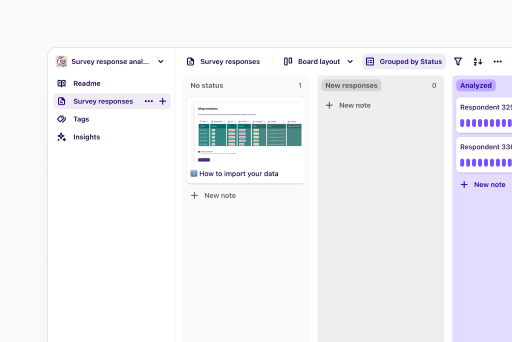

What Qualtrics survey analysis tools can help you?

Whatever your choice of the survey instrument, a good tool will make it easy for your researchers to create and deploy quantitative research studies, as well as empower respondents to answer in the fastest and most authentic ways possible.

There are several things to look out for when considering a survey solution, including:

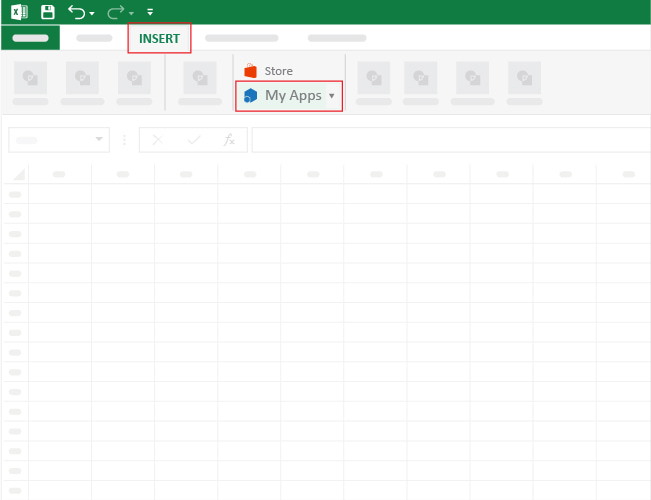

- Functionality Choose a cloud-based platform that’s optimized for mobile, desktop, tablet, and more.

- Integrations Choose a software tool that plugs straight into your existing systems via APIs.

- Ease of use Choose a software tool that has a user-friendly drag-and-drop interface.

- Statistical analysis tools Choose a software tool that automatically does data analysis, that generates deep insights and future predictions with just a few clicks.

- Dashboards and reporting Choose a software tool that presents your data in dashboards in real-time, giving you clear results of statistical significance and showing strengths and deficiencies.

- The ability to act on results Choose a software tool that helps leaders make strategies and development decisions with greater speed and confidence.

Qualtrics CoreXM has “built-for-purpose” technology that empowers everyone to gather insights and take action. Through a suite of best-in-class analytics tools and an intuitive drag-and-drop interface, you can run end-to-end surveys, market research projects, and more to capture high-quality insights.

Start Creating World Class Surveys

Related resources

Survey vs questionnaire 12 min read, response bias 13 min read, double barreled question 11 min read, likert scales 14 min read, survey research 15 min read, survey bias types 24 min read, post event survey questions 10 min read, request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

Close-Ended Questions: Examples and How to Use Them

- by Alice Ananian

- August 20, 2024

Imagine you’re a detective trying to solve a complex case with a room full of witnesses and time running out. Would you ask each witness to recount their entire day, or fire off a series of quick, specific questions to piece together the puzzle? This scenario illustrates the power of close-ended questions – a vital tool not just for detectives, but for researchers, marketers, educators, and professionals across all fields. In the vast landscape of data collection and analysis , asking the right questions can mean the difference between drowning in a sea of irrelevant information and uncovering precise, actionable insights.

Whether you’re conducting market research , gauging customer satisfaction, or designing an academic study, understanding how to craft and utilize close-ended questions effectively can be a game-changer. In this comprehensive guide, we’ll unlock the potential of close-ended questions, exploring what they are, their benefits, types, and how to use them to supercharge your data collection efforts. Get ready to transform your research from a time-consuming ordeal into a streamlined, efficient process.

What Are Close-Ended Questions?

Close-ended questions, also known as closed-ended questions, are queries that can be answered with a simple “yes” or “no,” or with a specific piece of information. These questions typically have a limited set of possible answers, often presented as multiple choice, rating scales, or dropdown menus. Unlike open-ended questions that allow respondents to provide free-form answers, close-ended questions offer a structured format that’s easy to answer and analyze.

For example:

- “Do you enjoy reading fiction books?” (Yes/No)

- “How often do you exercise?” (Daily/Weekly/Monthly/Never)

- “On a scale of 1-5, how satisfied are you with our service?” (1 = Very Dissatisfied, 5 = Very Satisfied)

These questions provide clear, concise data points that can be quickly collected and analyzed, making them invaluable in many fields.

Benefits of Using Closed-Ended Questions

Close-ended questions offer several advantages that make them a popular choice in various research and data collection scenarios:

Ease of Analysis

The structured nature of close-ended questions makes data analysis straightforward. Responses can be easily quantified, compared, and visualized using statistical tools.

Time-efficient

Both for respondents and researchers, close-ended questions are quicker to answer and process compared to open-ended questions.

Higher Response Rates

The simplicity of close-ended questions often leads to higher response rates, as participants find them less intimidating and time-consuming.

Reduced Ambiguity

With predefined answer options, there’s less room for misinterpretation of responses, leading to more reliable data.

Easier Comparisons

Standardized answers make it simpler to compare responses across different groups or time periods.

Focused Responses

Close-ended questions help keep respondents on topic, ensuring you get the specific information you’re seeking.

Scalability

These questions are ideal for large-scale surveys where processing open-ended responses would be impractical.

Consistency

They provide a uniform frame of reference for all respondents, leading to more consistent data.

By leveraging these benefits, researchers and professionals can gather precise, actionable data to inform decision-making processes across various fields.

Collect Insights From Your True Customers

Types of Close-Ended Questions

Close-ended questions come in various forms, each serving a specific purpose in data collection. Understanding these types can help you choose the most appropriate format for your research needs:

Dichotomous Questions: These offer two mutually exclusive options, typically yes/no, true/false, or agree/disagree.

Example: “Have you ever traveled outside your country?” (Yes/No)

Multiple Choice Questions: These provide a list of preset options, from which respondents choose one or more answers.

Example: “Which of the following social media platforms do you use? (Select all that apply)”

- TikTok

Rating Scale Questions: Also known as Likert scale questions, these ask respondents to rate something on a predefined scale.

Example: “How satisfied are you with our customer service?”

1 (Very Dissatisfied) to 5 (Very Satisfied)

Semantic Differential Questions: These use opposite adjectives at each end of a scale, allowing respondents to choose a point between them.

Example: “How would you describe our product?”

Unreliable 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 Reliable

Ranking Questions: These ask respondents to order a list of items based on preference or importance.

Example: “Rank the following factors in order of importance when choosing a hotel (1 being most important, 4 being least)”

- Price

- Location

- Amenities

- Customer reviews

Dropdown Questions: Similar to multiple choice, but presented in a dropdown menu format, useful for long lists of options.

Example: “In which country were you born?” (Dropdown list of countries)

Understanding these types allows you to choose the most appropriate format for gathering the specific data you need.

Examples of Close-Ended Questions

To illustrate how close-ended questions can be applied across various fields, here are some examples:

Market Research

- “How likely are you to recommend our product to a friend?” (Scale of 0-10)

- “Which of these features is most important to you?” (Multiple choice)

Employee Satisfaction Surveys

- “Do you feel your work is valued by your manager?” (Yes/No)

- “How would you rate your work-life balance?” (Scale of 1-5)

Academic Research

- “What is your highest level of education?” (Dropdown menu)

- “How often do you engage in physical exercise?” (Multiple choice: Daily, Weekly, Monthly, Rarely, Never)

Customer Feedback

- “Was your issue resolved during this interaction?” (Yes/No)

- “How would you rate the quality of our product?” (Scale of 1-5)

Political Polling

- “Do you plan to vote in the upcoming election?” (Yes/No/Undecided)

- “Which of the following issues is most important to you?” (Multiple choice)

Healthcare Surveys

- “Have you been diagnosed with any chronic conditions?” (Yes/No)

- “On a scale of 1-10, how would you rate your current health?”

These examples demonstrate the versatility of close-ended questions across different sectors and research needs.

How to Ask Close-Ended Questions

Crafting effective close-ended questions requires careful consideration. Here are some best practices to follow:

1. Be Clear and Specific: Ensure your question is unambiguous and focuses on a single concept.

Good: “Do you own a car?”

Poor: “Do you own a car or bike?”

2. Provide Exhaustive Options: When using multiple choice, make sure your options cover all possible answers.

Include an “Other” option if necessary.

3. Avoid Leading Questions: Frame your questions neutrally to prevent biasing responses.

Good: “How would you rate our service?”

Poor: “How amazing was our excellent service?”

4. Use Appropriate Scales: Choose scales that match the level of detail you need. A 5-point scale is often sufficient, but you might need a 7 or 10-point scale for more nuanced data.

5. Balance Your Scales: For rating questions, provide an equal number of positive and negative options.

6. Consider Your Audience: Use language and examples that are familiar to your respondents.

7. Pilot Test Your Questions: Before launching a full survey, test your questions with a small group to identify any issues or ambiguities.

By following these guidelines, you can create close-ended questions that yield reliable, actionable data.

When to Use Close-Ended Questions

While close-ended questions are powerful tools, they’re not suitable for every situation. Here are some scenarios where they’re particularly effective:

1. Large-Scale Surveys: When you need to collect data from a large number of respondents quickly and efficiently.

2. Quantitative Research: When you need numerical data for statistical analysis.

3. Benchmarking: When you want to compare results across different groups or time periods.

4. Initial Screening: To quickly identify respondents who meet specific criteria for further research.

5. Customer Satisfaction Measurement: To get a clear picture of customer sentiment using standardized metrics.

6. Performance Evaluations: To gather consistent feedback on employee or process performance.

7. Market Segmentation: To categorize respondents based on demographic or behavioral characteristics.

However, it’s important to note that close-ended questions may not be ideal when:

- You need in-depth, explanatory information

- You’re exploring a new topic and don’t know all possible answer options

- You want to understand the reasoning behind responses

In these cases, open-ended questions or a mix of both types might be more appropriate.

Close-ended questions are a fundamental tool for researchers, marketers, and educators due to their ability to efficiently collect precise data. It’s essential to comprehend the variations of these questions, when to use them, and how to craft them effectively to enhance data collection quality. Remember, while they are effective in many scenarios, they should occasionally be integrated with open-ended questions to achieve a comprehensive view.

Consider your objectives when designing surveys. Are quick, comparable data points necessary, or is there a need for in-depth explanations? The answer will guide your choice between close-ended and open-ended questions or a strategic mix of the two. Mastering the art of asking the right questions is a skill that can significantly improve your research insights, providing you with a powerful tool to make informed decisions and progress your projects.

What is the difference between closed-ended and open-ended questions?

Closed-ended questions provide respondents with a fixed set of options to choose from, while open-ended questions allow respondents to answer in their own words. Here’s a quick comparison:

Closed-ended questions:

- Have predefined answer choices

- Yield quantitative data

- Are easier to analyze statistically

- Take less time to answer

Example: “Do you enjoy reading? (Yes/No)”

Open-ended questions:

- Allow free-form responses

- Yield qualitative data

- Provide more detailed, nuanced information

- Take more time to answer and analyze

Example: “What do you enjoy about reading?”

Each type has its strengths, and many effective surveys use a combination of both to gather comprehensive insights.

Can closed-ended questions be used in qualitative research?

Yes, closed-ended questions can be utilized in qualitative research not only for participant screening, context setting, and data triangulation but also in mixed-methods research and as follow-ups to open-ended inquiries. Despite this, their use should be limited and strategic, as the primary aim of qualitative research is to elicit rich and descriptive responses using open-ended questions.

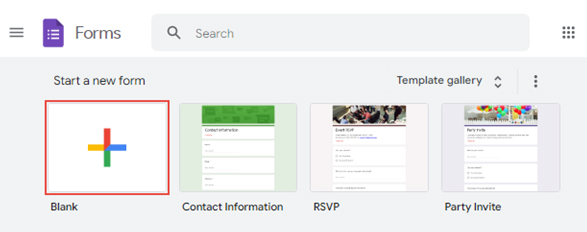

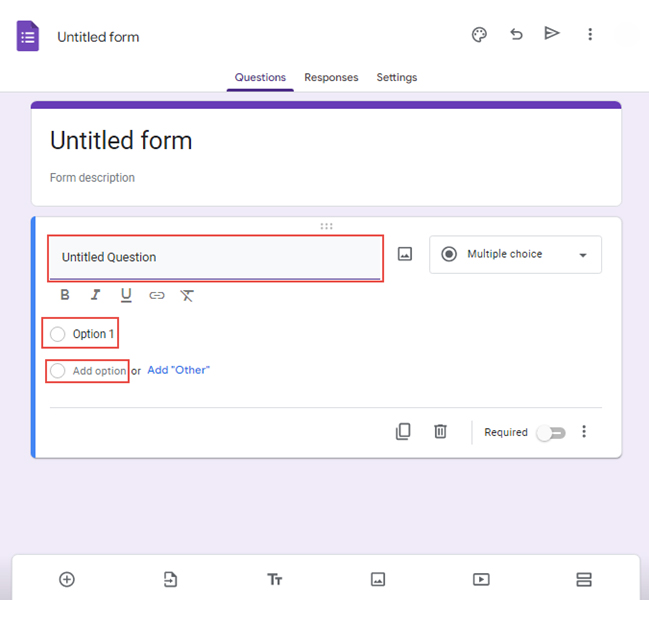

What tools can help in creating closed-ended questions?

Some of the top tools for creating closed-ended questions include Google Forms, SurveyMonkey , Qualtrics , Typeform , and LimeSurvey . These platforms are user-friendly and offer a range of question types, advanced features, and analysis tools. While these tools simplify the process, high-quality surveys require sound question design principles and subject expertise.

Alice Ananian

Alice has over 8 years experience as a strong communicator and creative thinker. She enjoys helping companies refine their branding, deepen their values, and reach their intended audiences through language.

Related Articles

10 Best Startup Incubators Worldwide

- by Arman Khachikyan

- February 8, 2024

5 Steps to Conduct Market Opportunity Analysis [Example Included]

- June 3, 2024

Close-Ended Questions: Definition, Types, Examples

Appinio Research · 15.12.2023 · 32min read

Are you seeking a powerful tool to gather structured data efficiently and gain valuable insights in your research, surveys, or communication? Close-ended questions, characterized by their predefined response options, offer a straightforward and effective way to achieve your goals . In this guide, we'll explore the world of close-ended questions, from their definition and characteristics to best practices, common pitfalls to avoid, and real-world examples. Whether you're a researcher, survey designer, or communicator, mastering close-ended questions will empower you to collect, analyze, and leverage data effectively for informed decision-making.

What are Close-Ended Questions?

Close-ended questions are a fundamental component of surveys, questionnaires , and research instruments. They are designed to gather specific and structured data by offering respondents a limited set of predefined response options.

Characteristics of Close-Ended Questions

Close-ended questions possess several defining characteristics that set them apart from open-ended questions.

- Limited Response Options: Close-ended questions present respondents with a finite set of answer choices, typically in the form of checkboxes, radio buttons, or a predefined list.

- Quantitative Data: The responses to close-ended questions yield quantitative data , making it easier to analyze statistically and draw numerical conclusions.

- Efficiency: They are efficient for data collection, as respondents can select from predetermined options, reducing response time and effort.

- Standardization: Close-ended questions ensure that all respondents receive the same set of questions and response options, promoting consistency in data collection .

- Objective Measurement: The structured nature of close-ended questions helps maintain objectivity in data collection, as personal interpretations are minimized.

Importance of Close-Ended Questions

Close-ended questions play a vital role in various communication contexts, offering several advantages that contribute to their significance.

- Clarity and Precision: Close-ended questions are crafted to elicit specific, focused responses, helping to avoid ambiguity and ensuring that respondents understand the intended query.

- Efficiency in Data Collection: They facilitate efficient data collection in scenarios where time and resources are limited, such as large-scale surveys, market research , or customer feedback.

- Quantitative Analysis: Close-ended responses can be quantified, allowing for statistical analysis, making them indispensable for empirical research and data-driven decision-making.

- Comparative Studies : They enable straightforward comparisons between different groups, individuals, or time periods, contributing to a better understanding of trends and patterns.

- Standardized Research: In academic and scientific research, close-ended questions contribute to the standardization of data collection methods, increasing the reliability of studies.

- Structured Interviews: In structured interviews , close-ended questions help interviewers cover specific topics systematically and consistently, ensuring that all key points are addressed.

- Reduced Respondent Burden: By providing predefined options, close-ended questions simplify the response process, reducing the cognitive load on respondents.

- Quantitative Feedback in Business: In business and customer service, close-ended questions provide numerical feedback that can be used to assess customer satisfaction, product performance, and service quality.

- Public Opinion Polls: Close-ended questions are commonly employed in public opinion polling to gauge public sentiment on various political, social, or economic issues.

Understanding close-ended questions and characteristics, as well as their importance in communication, empowers researchers, survey designers, and communicators to effectively collect and analyze structured data to inform decisions, policies, and strategies.

Types of Close-Ended Questions

Close-ended questions are versatile tools used in surveys and research to gather specific, structured data. Let's explore the various types of close-ended questions to understand their unique characteristics and applications.

Yes/No Questions

Yes/no questions are the simplest form of close-ended questions. Respondents are presented with a binary choice and are required to select either "Yes" or "No." These questions are excellent for gathering clear-cut information and can be used in a variety of research contexts.

For example, in a customer satisfaction survey, you might ask, "Were you satisfied with our service?" with the options "Yes" or "No."

Multiple-Choice Questions

Multiple-choice questions provide respondents with a list of options, and they are asked to select one or more answers from the provided choices. These questions offer flexibility and are ideal when you want to capture a range of possible responses.

For instance, in a product feedback survey, you could ask, "Which of the following features do you find most valuable?" with a list of feature options for respondents to choose from.

Rating Scale Questions

Rating scale questions ask respondents to rate something on a numerical scale. Commonly used scales range from 1 to 5 or 1 to 7, allowing participants to express their opinions or attitudes quantitatively. These questions are widely used in fields such as psychology, marketing, and customer feedback.

For instance, you might use a rating scale question like, "On a scale of 1 to 5, how satisfied are you with our customer service?"

Dichotomous Questions

Dichotomous questions are a subset of yes/no questions but may include more nuanced options beyond a simple "yes" or "no." They provide respondents with two contrasting choices, making them suitable for situations where a binary decision is necessary but requires more detail.

For example, in a political survey, you could ask, "Do you support the proposed policy: strongly support, somewhat support, somewhat oppose, strongly oppose?"

Forced-Choice Questions

Forced-choice questions present respondents with a set of options and require them to select only one choice, eliminating the possibility of choosing multiple answers. These questions are useful when you want to force respondents to make a decision, even if they are indecisive or unsure.

In employee performance evaluations, for instance, you might ask, "Which area should the employee focus on for improvement this quarter?" with a list of specific areas to choose from.

Understanding the characteristics and applications of these close-ended question types will help you design surveys and questionnaires that effectively collect the data you need for your research or decision-making processes.

Why Are Close-Ended Questions Used?

Close-ended questions offer several advantages when incorporated into surveys, questionnaires, and research instruments. These advantages make them a valuable choice for collecting structured data.

- Efficient Data Collection: Close-ended questions streamline the data collection process. Respondents can quickly choose from predefined options, reducing the time and effort required to complete surveys or questionnaires.

- Standardized Responses: With close-ended questions, all respondents receive the same set of questions and response options. This standardization ensures consistency in data collection and simplifies the analysis process.

- Statistical Analysis: Close-ended responses can be easily quantified, making them ideal for statistical analysis. Researchers can use statistical tools to identify patterns , correlations , and trends within the data.

- Ease of Comparison: The structured nature of close-ended questions enables easy comparison of responses across different participants, groups, or time periods. This comparability is particularly valuable in longitudinal studies and market research.

- Reduced Ambiguity: Close-ended questions leave little room for ambiguity in responses, as they provide clear and predefined options. This clarity helps minimize misinterpretation of answers.

- Objective Data: Close-ended questions generate objective data, making it easier to draw conclusions based on quantitative information. This objectivity is especially important in fields like psychology and social sciences.

Disadvantages of Close-Ended Questions

While close-ended questions have their advantages, it's essential to be aware of their limitations and potential drawbacks. Here are some disadvantages associated with using close-ended questions.

- Limited Insight into Participant's Perspective: Close-ended questions may restrict respondents from fully expressing their thoughts, feelings, or experiences. This limitation can lead to a lack of depth in understanding participant perspectives.

- Risk of Bias: The phrasing of close-ended questions can introduce bias. Biased questions may unintentionally influence respondents to select specific responses, leading to skewed results.

- Difficulty Capturing Nuanced Opinions: Some topics require nuanced responses that cannot be adequately captured by predefined answer options. Close-ended questions may oversimplify complex issues.

- Inability to Explore Unforeseen Issues: Close-ended questions limit researchers to the options provided in the questionnaire. They may not account for unforeseen issues or emerging insights that open-ended questions could capture.

- Possible Social Desirability Bias: Respondents may choose answers they believe are socially acceptable or expected, rather than their actual opinions or experiences. This can result in inaccurate data.

- Limited Qualitative Data: Close-ended questions prioritize quantitative data. If qualitative insights are essential for your research, incorporating open-ended questions is necessary to capture detailed narratives.

Understanding both the advantages and disadvantages of close-ended questions is crucial for effective survey and questionnaire design. Depending on your research goals and the nature of the data you seek, you can make informed decisions about when and how to use close-ended questions in your data collection process.

When to Use Close-Ended Questions?

Close-ended questions are a valuable tool in research and surveys, but knowing when to deploy them is essential for effective data collection. Let's explore the various contexts and scenarios in which close-ended questions are particularly advantageous.

Surveys and Questionnaires

Surveys and questionnaires are perhaps the most common and well-suited applications for close-ended questions. They offer several advantages in this context.

- Efficiency: In surveys and questionnaires, respondents often face time constraints. Close-ended questions allow them to provide structured responses quickly, leading to higher completion rates.

- Ease of Data Entry: Close-ended responses are typically easier to process and enter into databases or analysis software. This reduces the chances of data entry errors.

- Comparability: When conducting large-scale surveys, the ability to compare responses across participants becomes crucial. Close-ended questions provide standardized response options for easy comparison.

- Quantitative Data: Surveys often aim to gather quantitative data for statistical analysis. Close-ended questions are well-suited for this purpose, as they generate numerical data that can be analyzed using various statistical techniques.

Quantitative Research

In quantitative research , where the primary goal is to obtain numerical data that can be subjected to statistical analysis , close-ended questions play a significant role. They are favored in quantitative research due to:

- Measurement Precision: Close-ended questions enable precise measurement of specific variables or constructs. Researchers can assign numerical values to responses, facilitating quantitative analysis.

- Hypothesis Testing: Quantitative research often involves hypothesis testing. Close-ended questions provide structured data that can be directly used to test hypotheses and draw statistical inferences.

- Large Sample Sizes: Quantitative research often requires large sample sizes to ensure the reliability of findings. Close-ended questions are efficient in collecting data from a large number of participants.

- Data Consistency: The standardized nature of close-ended questions ensures that all respondents are presented with the same set of options, reducing response variations due to question wording.

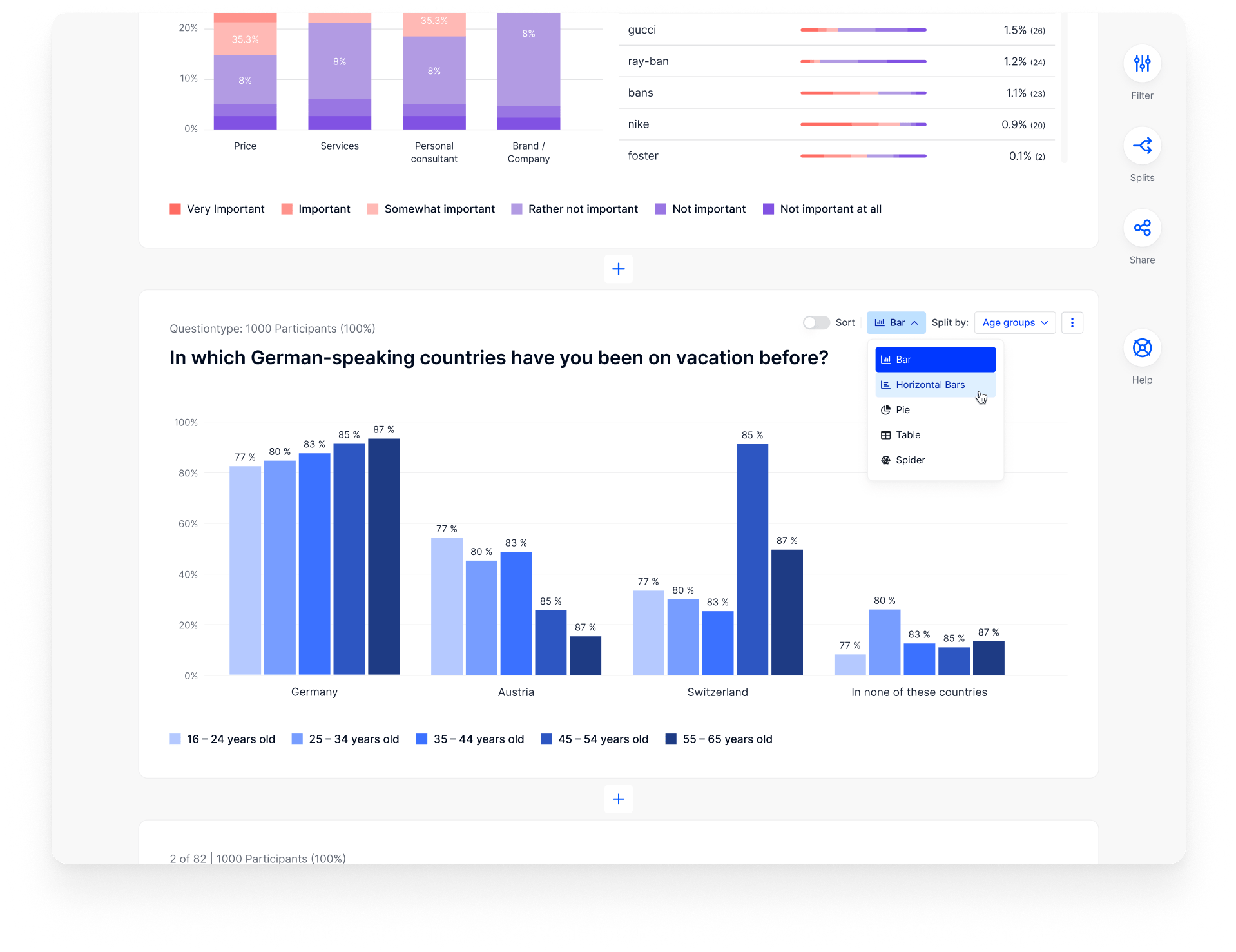

Market Research

Market researchers frequently rely on close-ended questions to gather insights into consumer behavior , preferences, and opinions. Close-ended questions are well-suited for market research for the following reasons:

- Comparative Analysis: Close-ended questions make it easy to compare customer responses across different demographics , regions, or time periods. This comparative analysis informs marketing strategies and product development .

- Quantitative Insights: Market research often involves the collection of quantitative data to measure customer satisfaction, brand perception , and market trends. Close-ended questions provide numerical data for analysis.

- Efficiency in Data Processing: Market research often deals with large volumes of data. Close-ended questions simplify data processing and analysis, enabling faster decision-making.

- Benchmarking: Companies use close-ended questions to benchmark their performance against competitors. Standardized response options make it possible to gauge how a company fares in comparison to others in the industry.

As you navigate the intricate world of research and surveys, striking the right balance between close-ended and open-ended questions is key to uncovering valuable insights. To streamline your data collection process and gain a holistic understanding of your research objectives, you should explore the capabilities of Appinio.

Appinio offers versatile tools to help you craft well-rounded surveys, harnessing the power of both structured and open-ended questions. Ready to elevate your research game? Book a demo today and experience how Appinio can enhance your data collection efforts, enabling you to make informed decisions based on comprehensive insights.

Book a Demo

How to Craft Close-Ended Questions?

Designing close-ended questions that yield accurate and meaningful data requires careful consideration of various factors. Let's delve into the fundamental principles and best practices for crafting practical close-ended questions.

Clarity and Simplicity

Clarity and simplicity are fundamental when formulating close-ended questions. Your goal is to make it easy for respondents to understand and respond accurately.

- Use Clear Language: Frame questions using straightforward and clear language. Avoid jargon, technical terms, or complex vocabulary that may confuse respondents.

- Avoid Double-Barreled Questions: Double-barreled questions combine multiple ideas or topics into one question, making it challenging for respondents to provide a precise answer. Split such questions into separate inquiries.

- Keep It Concise: Long and convoluted questions can overwhelm respondents. Keep your questions concise and to the point.

- Use Everyday Language: Ensure that your questions are phrased in a way that resonates with your target audience. Use language they are familiar with to maximize comprehension.

Avoiding Leading Questions

It's crucial to avoid leading questions when crafting close-ended questions. Leading questions can unintentionally influence respondents to provide a specific answer rather than expressing their genuine opinions. To steer clear of them:

- Stay Neutral: Phrase questions in a neutral and unbiased manner. Avoid any language or tone that suggests a preferred answer.

- Balance Positive and Negative Wording: If you have a set of response options that include both positive and negative statements, ensure they are balanced to avoid bias.

- Pretest for Bias: Conduct pretesting with a diverse group of respondents to identify any potential bias in your questions. Adjust questions as needed based on feedback.

Balancing Response Options

Balancing response options is essential to ensure that your close-ended questions provide accurate and comprehensive data.

- Mutually Exclusive Options: Ensure that response options are mutually exclusive, meaning respondents can choose only one option that best aligns with their perspective.

- Exhaustive Choices: Include all relevant response options to cover a full range of possible answers. Leaving out options can lead to incomplete or skewed data.

- Avoiding Overloading: Be cautious not to overload respondents with too many response choices. Striking the right balance between providing choices and avoiding overwhelming respondents is essential.

Pilot Testing

Before deploying your survey or questionnaire, pilot testing is a crucial step to refine your close-ended questions. Pilot testing involves administering the survey to a small group of participants to identify and address any issues.

- Select a Representative Sample : To ensure realistic feedback, choose a sample that closely resembles your target audience .

- Gather Feedback: Collect feedback on your questions' clarity, wording, and comprehensibility. Ask participants if any questions were confusing or if they felt any bias in the questions.

- Iterate and Revise: Based on the feedback received during pilot testing, make necessary revisions to your close-ended questions to improve their quality and effectiveness.

Crafting effective close-ended questions is a skill that improves with practice. By focusing on clarity, neutrality, balance, and thorough testing, you can create questions that elicit reliable and insightful responses from your survey or research participants.

How to Analyze Close-Ended Responses?

Once you've collected close-ended responses in your survey or research, the next crucial step is to analyze and interpret the data effectively. We'll explore the various methods and techniques for making sense of close-ended responses.

Data Cleaning

Data cleaning is an essential preliminary step in the analysis process. It involves identifying and rectifying inconsistencies, errors, or outliers in your close-ended responses.

- Identify Missing Data: Check for missing responses and decide how to handle them—whether by imputing values or excluding incomplete responses from analysis.

- Outlier Detection: Identify outliers in your data that may skew the results. Determine whether outliers are genuine data points or errors that need correction.

- Standardization: Ensure that all data is in a consistent format. This may involve converting responses to a common scale or addressing variations in how respondents answered.

- Data Validation: Validate responses against predefined criteria to ensure accuracy and reliability. Flag any responses that deviate from expected patterns.

- Documentation: Keep a detailed record of the data cleaning process, including the rationale for decisions made. This documentation is crucial for transparency and reproducibility.

Frequency Distribution

Frequency distribution is a fundamental technique for understanding the distribution of responses in your data. It provides an overview of how often participants chose each response option. To create a frequency distribution:

- Tabulate Responses: Count the number of times each response option was selected for each close-ended question.

- Create Frequency Tables: Organize the data into frequency tables, displaying response options and their corresponding frequencies.

- Visualize Data: Visual representations such as bar charts or histograms can help you quickly grasp the distribution of responses.

- Identify Patterns: Examine the frequency distribution for patterns , trends, or anomalies. This step can reveal insights about respondent preferences or tendencies.

Cross-Tabulation

Cross-tabulation is a powerful technique that allows you to explore relationships between two or more variables in your close-ended responses. It's particularly useful for identifying patterns or correlations between variables.

- Select Variables: Choose the variables you want to analyze for relationships. These variables can be from different questions in your survey.

- Create Cross-Tabulation Tables: Create tables that show how responses to one variable relate to responses to another variable. This involves counting how many participants fall into each combination of responses.

- Calculate Percentages: Convert the counts into percentages to understand the proportion of respondents in each category.

- Analyze Patterns: Examine the cross-tabulation tables to identify significant patterns, associations, or trends between variables.

Drawing Conclusions

Drawing conclusions from close-ended responses involves making sense of the data and using it to answer your research questions or hypotheses.

- Statistical Analysis: Depending on your research design, apply statistical tests or techniques to determine the significance of relationships or differences in responses.

- Contextual Understanding: Consider the broader context in which the data was collected. Understand how external factors may have influenced the responses.

- Comparative Analysis: Compare your findings to existing literature or benchmarks to provide context and insights.

- Limitations: Acknowledge any limitations in your analysis, such as sample size , potential bias, or data collection constraints.

- Actionable Insights: Ensure that your conclusions provide actionable insights or recommendations based on the data collected.

- Report Findings: Present your findings in a clear and accessible manner, using visuals, tables, and narrative explanations to convey the results effectively.

Effectively analyzing and interpreting close-ended responses is critical for deriving meaningful insights and making informed decisions in your research or survey projects. By following these steps and techniques, you can unlock the valuable information hidden within your data.

Close-Ended Questions Examples

To better understand how close-ended questions are crafted and used effectively, let's delve into some real-world examples across different fields and scenarios. These examples will illustrate the diversity of close-ended questions and their applications.

Example 1: Customer Satisfaction Survey

Question: On a scale of 1 to 5, how satisfied are you with our product?

- Very Dissatisfied

- Dissatisfied

- Neutral

- Satisfied

- Very Satisfied

This is a classic example of a rating scale question . Respondents are asked to rate their satisfaction level on a numerical scale. The predefined response options allow for quantifiable data collection, making it easy to analyze and track changes in customer satisfaction over time.

Example 2: Employee Feedback

Question: Did you receive adequate training for your new role?

This yes/no question is straightforward and ideal for capturing specific information. It provides a binary response, making it easy to categorize employees who received adequate training from those who did not.

Example 3: Political Opinion Poll

Question: Which political party do you align with the most?

- Democratic Party

- Republican Party

- Independent

- Other (please specify): ________________

This multiple-choice question allows respondents to choose their political affiliation from a set of predefined options. It also provides an "Other" category with an open-ended field for respondents to specify a different affiliation, ensuring inclusivity.

Example 4: Product Feature Prioritization

Question: Please rank the following product features in order of importance, with 1 being the most important and 5 being the least important:

- Price

- Durability

- User-Friendliness

- Performance

- Design

In this example, respondents are asked to rank product features based on their preferences. This type of close-ended question helps gather valuable insights into which features customers prioritize when making purchasing decisions.

Example 5: Healthcare Patient Feedback

Question: How would you rate the quality of care you received during your recent hospital stay?

- Excellent

- Very Good

This rating scale question assesses patient satisfaction with the quality of healthcare services . It allows for the collection of quantitative data that can be analyzed to identify areas for improvement in patient care.

These examples showcase the versatility of close-ended questions in various domains, including customer feedback, employee assessments, political polling, product development, and healthcare. When crafting close-ended questions, consider the specific context, the type of data you need, and the preferences of your target audience to design questions that yield valuable and actionable insights.

Best Practices for Close-Ended Questionnaires

Creating effective close-ended questionnaires and surveys requires attention to detail and adherence to best practices. Here are some tips to ensure your questionnaires yield high-quality data.

- Clear and Concise Language: Use clear, simple, and jargon-free language to ensure respondents understand the questions easily.

- Logical Flow: Organize questions in a logical order, starting with easy-to-answer and non-sensitive questions before moving to more complex or sensitive topics.

- Avoid Double Negatives: Ensure questions are phrased positively, avoiding double negatives that can confuse respondents.

- Provide Clear Instructions: Include clear instructions at the beginning of the questionnaire to guide respondents on how to complete it.

- Use Consistent Scales: If you're using rating scales, keep the scale consistent throughout the questionnaire. For example, if you use a 1-5 scale, maintain that scale for all relevant questions.

- Randomize Response Order: To minimize order bias, consider randomizing the order of response options for multiple-choice questions.

- Pretest Questionnaires: Conduct pilot testing with a small group of participants to identify and rectify any issues with question clarity, wording, or bias.

- Limit Open-Ended Questions: While focusing on close-ended questions, consider including a few strategic open-ended questions to capture qualitative insights where necessary.

Common Close-Ended Questions Mistakes to Avoid

Avoiding common mistakes is essential to ensure the quality and reliability of your close-ended questionnaires. Here are some pitfalls to steer clear of:

- Biased Questions: Avoid framing questions in a way that leads respondents toward a particular answer or opinion.

- Ambiguity: Ensure questions are clear and unambiguous to prevent confusion among respondents.

- Overloading Respondents: Don't overwhelm respondents with too many close-ended questions. Balance with open-ended questions when needed.

- Ignoring Response Options: Ensure that response options cover the full range of possible answers and don't miss out on relevant choices.

- Using Double-Barreled Questions: Avoid combining multiple ideas or topics into a single question, as it can lead to imprecise responses.

- Neglecting Pilot Testing: Skipping pilot testing can result in issues with question wording or formatting that could have been resolved beforehand.

- Lack of Variability: Ensure that response options have sufficient variability to capture nuances in responses. Avoid creating questions with very similar answer choices.

- Failure to Update Questions: Over time, the relevance of certain questions may change. Regularly review and update your questionnaires to reflect current contexts and concerns.

- Neglecting Privacy and Sensitivity: Be mindful of sensitive or personal questions, and provide options for respondents to decline or skip such questions.

By adhering to best practices and avoiding common mistakes, you can design close-ended questionnaires that collect accurate, unbiased, and actionable data while providing a positive experience for respondents.

Close-ended questions are a valuable tool for anyone looking to collect specific, structured data efficiently and accurately. They offer clarity, ease of analysis, and standardization, making them essential in various fields , from research and surveys to business and communication. By understanding the characteristics, best practices, and potential pitfalls of close-ended questions, you can harness their power to gain insights, make informed decisions, and drive positive outcomes in your endeavors. So, whether you're conducting surveys, analyzing customer feedback, or conducting research, remember that well-crafted close-ended questions are your key to unlocking valuable data and understanding your audience or participants better. Start using close-ended questions wisely, and watch your ability to collect, analyze, and act on data soar, ultimately leading you toward more successful and informed outcomes in your professional pursuits.

How to Use Close-Ended Questions for Market Research?

Introducing Appinio , the real-time market research platform that revolutionizes the way you leverage close-ended questions for market research. With Appinio, you can conduct your own market research in minutes, gaining valuable insights for data-driven decision-making.

- Speedy Insights: From questions to insights in minutes. Appinio's lightning-fast platform ensures you get the answers you need when you need them.

- User-Friendly: No need for a PhD in research. Appinio's intuitive platform is designed for everyone, making market research accessible to all.

- Global Reach: Survey your defined target group from over 90 countries, with the ability to narrow down from 1200+ characteristics.

Say goodbye to boring, intimidating, and overpriced market research—Appinio is here to make it exciting, intuitive, and seamlessly integrated into your everyday decision-making.

Get free access to the platform!

Join the loop 💌

Be the first to hear about new updates, product news, and data insights. We'll send it all straight to your inbox.

Get the latest market research news straight to your inbox! 💌

Wait, there's more

19.09.2024 | 8min read

Track Your Customer Retention & Brand Metrics for Post-Holiday Success

16.09.2024 | 10min read

Creative Checkup – Optimize Advertising Slogans & Creatives for ROI

03.09.2024 | 8min read

Get your brand Holiday Ready: 4 Essential Steps to Smash your Q4

- Solutions Industry Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Member Experience Technology Use case AskWhy Communities Audience InsightsHub InstantAnswers Digsite LivePolls Journey Mapping GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys Research Edition

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Webinars Help center

Close Ended Questions

Close ended questions and its types are critical for collecting survey responses within a limited range of options. they are the foundation of all statistical analysis techniques applied on questionnaires and surveys..

Join over 10 million users

Content Index

- What are Close Ended Questions?

- Types of Close Ended Questions with Examples

When to use Close Ended Questions?

Advantages of close ended questions, what are open ended questions, examples of open ended questions, difference between open ended and closed ended questions.

Watch the 1-minute tour

What are Close Ended Questions: Definition

Close ended questions are defined as question types that ask respondents to choose from a distinct set of pre-defined responses, such as “yes/no” or among set multiple choice questions . In a typical scenario, closed-ended questions are used to gather quantitative data from respondents.

Closed-ended questions come in a multitude of forms but are defined by their need to have explicit options for a respondent to select from.

However, one should opt for the most applicable question type on a case-by-case basis, depending on the objective of the survey . To understand more about the close ended questions, let us first know its types.

Types of Close Ended Questions with Survey Examples

Dichotomous question.

These close ended question are indicative questions that can be answered either in one of the two ways, “yes” or “no” or “true” or “false”.

Multiple choice question

Multiple choice closed ended questions are easy and flexible and helps the researcher obtain data that is clean and easy to analyse. It typically consists of stem - the question, correct answer, closest alternative and distractors.

Types of Multiple Choice Questions

1. likert scale multiple choice questions.

These closed ended questions, typically are 5 pointer or above scale questions where the respondent is required to complete the questionnaire that needs them to indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree.

2. Rating Scale Multiple Choice Questions

These close ended survey questions require the respondents to assign a fixed value in response, usually numeric. The number of scale points depends on what sort of questions a researcher is asking.

3. Checklist type Multiple Choice Questions

This type of closed ended question expects the respondents to make choices from the many options that have been stated, the respondent can choose one or more options depending on the question being asked.

4. Rank Order Multiple Choice Question

These closed ended questions come with multiple options from which the respondent can choose based on their preference from most prefered to least prefered (usually in bullet points).

While answering a survey, it is most likely that you may end up answering only close ended questions. There is a specific reason to this, close ended question helps gather actionable, quantitative data. Let’s look at the definitive instances where closed-ended questions are useful.

Closed Ended Questions have very distinct responses, one can use these responses by allocating a value to every answer. This makes it easy to compare responses of different individuals which, in turn, enables statistical analysis of survey findings.

For example: respondents have to rate a product from 1 to 5 (where 1= Horrible, 2=Bad, 3=Average, 4= Good, and 5=Excellent) an average rating of 2.5 would mean the product is below average.

To restrict the responses:

To reduce doubts, to increase consistency and to understand the outlook of a parameter across the respondents close ended questions work the best as they have a specific set of responses, that restricts the respondents and allows the person conducting the survey obtain a more concrete result.

For example, if you ask open ended question “Tell me about your mobile usage”, you will end up receiving a lot of unique responses. Instead one can use close ended question (multiple choice), “How many hours do you use your mobile in a day”, 0-5 hours, 5-10 hours, 10-15 hours. Here you can easily analyse the data form a conclusion saying, “54% of the respondents use their mobile for 0-5 hours a day.”

To conduct surveys on a large scale:

Close ended questions are often asked to collect facts about respondents. They usually take less time to answer. Close ended questions work the best when the sample population of the respondents is large.

For example, if an organization wants to collect information on the gadgets provided to its employees instead of asking a question like, “What gadgets has the organization provided to you?”, it is easier to give the employees specific choice like, laptop, tablet, phone, mouse, others. This way the employees will be able to choose quickly and correctly.

They are easy to understand hence the respondents don’t need to spend much time on reading the questions time and again. Close ended questions are quick to respond to.

When the data is obtained and needs to be compared closed ended question provide better insight.

Since close ended questions are quantifiable, the statistical analysis of the same becomes much easier.

Since the response to the questions are straightforward it is much likely that the respondents will answer on sensitive or even personal questions.

Although, many organizations use open ended questions in their survey, using close ended question is beneficial because closed-ended questions come in a variety of forms. They are usually categorized based on the need to have specific options for the respondents, so that they can select them without any hesitation.

The open-ended questions are questions that cannot be answered by a simple ‘Yes’ or ‘No’, and require respondents to elaborate on their answers. They are textual responses and generally used for qualitative analysis. Responses to these questions are analyzed for their sentiments to understand if the respondent is satisfied or not.

Open-ended questions are typically used to ask comments or suggestions that may not have been covered in the survey questions prior. Survey takers can explain their responses, feedback, experiences, etc. and convey their feelings or concerns.

How can we improve your experience?

Do you have any comments or suggestions?

What would you like to see differently in our product or service?

What are the challenges you have faced while using our product or service?

How can we help you to grow your business?

How can we help you to perform better?

What did you like/dislike most about the event?

The selection between open-ended and closed-ended questions depends mainly on the below factors.

Type of data : Closed-ended questions are used when you need to collect data that will be used for statistical analysis. They collect quantitative data and offer a clear direction of the trends. The statements inferred from the quantitative data are unambiguous and hardly leave any scope for debate. Open-ended questions, on the other hand, collect qualitative data pertaining to emotions and experiences that can be subjective in nature. Qualitative data is used to generate sentiment analysis reports, text analytics, and word cloud report.

Depth of data : Closed-ended questions can be used to questions that collect quantifiable data needed for the primary analysis. To dig into the reasons behind the response, open-ended questions can be used. It will help you understand why respondents gave specific feedback or a rating.

Situation : At times, the options mentioned in the survey do not cover all the possible scenarios. Open-ended questions help to cover this gap and offers freedom to the respondents to convey whatever they want to. Whereas closed-ended questions are simple and easy to answer. It does not take much time to answer them and so are quite respondent-friendly.

Create a free account

- Sample questions

- Sample reports

- Survey logic

- Integrations

- Professional services

- Survey Software

- Customer Experience

- Communities

- Polls Explore the QuestionPro Poll Software - The World's leading Online Poll Maker & Creator. Create online polls, distribute them using email and multiple other options and start analyzing poll results.

- Research Edition

- InsightsHub

- Survey Templates

- Case Studies

- AI in Market Research

- Quiz Templates

- Qualtrics Alternative Explore the list of features that QuestionPro has compared to Qualtrics and learn how you can get more, for less.

- SurveyMonkey Alternative

- VisionCritical Alternative

- Medallia Alternative

- Likert Scale Complete Likert Scale Questions, Examples and Surveys for 5, 7 and 9 point scales. Learn everything about Likert Scale with corresponding example for each question and survey demonstrations.

- Conjoint Analysis

- Net Promoter Score (NPS) Learn everything about Net Promoter Score (NPS) and the Net Promoter Question. Get a clear view on the universal Net Promoter Score Formula, how to undertake Net Promoter Score Calculation followed by a simple Net Promoter Score Example.

- Offline Surveys

- Customer Satisfaction Surveys

- Employee Survey Software Employee survey software & tool to create, send and analyze employee surveys. Get real-time analysis for employee satisfaction, engagement, work culture and map your employee experience from onboarding to exit!

- Market Research Survey Software Real-time, automated and advanced market research survey software & tool to create surveys, collect data and analyze results for actionable market insights.

- GDPR & EU Compliance

- Employee Experience

- Customer Journey

- Executive Team

- In the news

- Testimonials

- Advisory Board

QuestionPro in your language

- Encuestas Online

- Pesquisa Online

- Umfrage Software

- برامج للمسح

Awards & certificates

The experience journal.

Find innovative ideas about Experience Management from the experts

- © 2021 QuestionPro Survey Software | +1 (800) 531 0228

- Privacy Statement

- Terms of Use

- Cookie Settings

Instant insights, infinite possibilities

Closed-ended questions: Overview, uses, and examples

Last updated

20 March 2024

Reviewed by

Do you value the simplicity and elegance of a yes-or-no question?

These simple questions—known as closed-ended questions—are the fundamental tools you can use to collect quantitative data.

In this article, we will cover everything you need to know about closed-ended questions, including the different types, use cases, and best practices to gain easy-to-analyze data you can use to improve your business.

Free template to analyze your survey results

Analyze your survey results in a way that's easy to digest for your clients, colleagues or users.

- What are closed-ended questions?

Closed-ended questions encourage the reader to respond with one of the predetermined options you or your team have selected. The most common answer formats for closed-ended questions are yes/no, true/false, or a set list of multiple-choice answers.

Closed-ended questions aim to direct the responder to answer your question in a standardized way that produces controlled quantitative data about your target audience.

For example, the question, “Did you enjoy the latest feature update to our platform?” is a closed-ended question that requires either a “yes” or “no” answer. It will give your team a quick understanding of the overall customer opinion of the update.

Over time, researchers can use closed-ended questions to collect statistical information about your brand or product. These quantitative insights can be incredibly valuable when making future brand decisions, as they give your team a better understanding of your target demographic, their purchasing trends, and more.

- Closed-ended vs. open-ended questions

Depending on the type of information you want to collect from your survey or questionnaire, there are two overarching categories of questions you can use. Each style of question offers unique benefits and needs to be used correctly to produce accurate and helpful insights that your team can use.

Closed-ended questions

Closed-ended questions collect quantitative data and encourage the participant to answer from a list of predetermined options. They help teams collect easily measurable data about a specific metric they’re tracking. Closed-ended questions are rigid, focused, and data-driven.

An example of a closed-ended, data-driven question:

On a scale from 1 to 5 (1 being horrible, and 5 being excellent), how would you rate your recent visit to our store?

Open-ended questions

Open-ended questions collect qualitative data and encourage participants to provide subjective, personal responses based on their experiences and opinions. They help your team collect a more nuanced understanding of a subject, e.g., a particular pain point or positive experience related to a product or service.

These questions are exploratory, encouraging participants to write sentences or paragraphs to share their thoughts.

An example of an open-ended, personalized question:

Tell us about your most recent visit to our store.

Important note: The most effective surveys contain closed and open-ended questions to collect a diverse range of data. Understanding the core benefits of each question style is necessary to pick the right question style for your survey. From there, your team will collect information from your survey to produce helpful insights to improve your work and future projects.

- Types of closed-ended questions

To collect the most accurate data, you need to understand the different types of closed-ended questions. Before you begin your next round of research, consider the following types of survey questions to ensure you collect the correct type of quantitative data.

Dichotomous questions

Dichotomous questions (based on the word “dichotomy” – to be divided into two mutually exclusive categories) refer to questions that have only two possible answers.

Questions that can be answered with “yes/no,” “true/false,” “thumbs up/thumbs down,” or “agree/disagree” are examples of dichotomous questions. They can be incredibly effective for collecting quick, simple participant responses.

While dichotomous questions do not offer the participant options for nuanced responses, these questions are incredibly effective for getting snapshot data about a specific tracking metric.

Examples of dichotomous closed-ended questions include:

Have you heard of [X product] before? (Yes or no)

You have bought a product from [X brand] in the last six months. (True or false)

How was your recent call with our sales team? (Thumbs up or thumbs down)

The price of our premium service tier matches its value. (Agree or disagree)

Rating-scale questions

Rating-scale questions use a pre-set scale of responses to encourage participants to provide feedback on their experiences, opinions, or preferences.

Commonly used in customer experience surveys, the goal of this type of closed-ended question is to collect quantitative data that is standardized and easy to analyze.

Depending on the content of the question you are asking, examples of types of measures you can use for rating questions include a 10-point rating scale, the Likert scale (from strongly disagree to strongly agree), or a rating based on level of satisfaction (very dissatisfied to very satisfied).

As a great way to collect more nuanced information that does not require rigorous analysis, examples of rating-scale closed-ended questions include:

[X customer service worker] was supportive during our call. (Rate from strongly agree to strongly disagree)

On a scale from 1 to 10, (1 being very unlikely and 10 being very likely), how likely are you to recommend our products to a friend?

How satisfied were you with the latest software update? (Rate from very satisfied to very dissatisfied)

Multiple-choice questions

Multiple-choice questions offer the participant a selection of possible answers, but, unlike questions at school, there are no right or wrong answers.

Designed to tread the line between getting more nuanced participant answers but still being easy to analyze and interpret, well-written multiple-choice survey questions must include answers specific to the information you want to collect.

This easy-to-understand survey question style often has a higher engagement rate. Integrating multiple-choice questions into key sections of your survey is a great way to collect information from your target audience.

Examples of multiple-choice closed-ended questions include:

How did you hear about our company? (Answers could include online, from a friend, on social media, etc.)

Which restaurant interests you most for the company Christmas party? (Answers would include the restaurants being considered)

How long have you been using our products or services? (Answers could include month or year ranges)

Important note: In some cases, adding “Other” as a possible answer option for multiple-choice questions may be appropriate if your provided answers do not cover all possible responses. If you choose to do this (which is very common and can be an effective way to collect additional insights), you need to be aware that the question is no longer truly closed-ended. By adding the option to write out their answer, the question becomes more open-ended, which can make the data harder to analyze and less standardized.

Ranking-order questions

Ranking-order questions are a style of closed-ended question that asks the participants to order a list of predetermined answers based on the type of information your team is looking to collect. This is a great tool for collecting information about a list of related options.

Used to gain insights into the preferences or opinions of your participants, these types of questions are still structured and easy to analyze. Additionally, the advantage of using ranking-style closed-ended questions is that you not only discover which option is most in demand but you also gain insights into the overall ordering of all possible options.

Examples of ranking-order closed-ended questions include:

Rank the following product features based on your preferences. (From most likely to use to least likely to use)

Organize these possible new logos. (From your favorite to least favorite)

Rank the following product brands. (From most appealing to least appealing)

- Closed-ended questions pros and cons

Because closed-ended questions produce a certain type of data from your target audience, it is important to understand their advantages and disadvantages before using them in your next survey.

Closed-ended questions can improve your survey because they:

Are quick and easy to fill out

Offer standardized responses for easy analysis

Increase survey response rates

Naturally group participants based on responses

Are customizable to the specific metric you are tracking

Avoid incorrect and irrelevant responses

Reduce participant confusion

Closed-ended questions can be limited because they:

Can lack nuance and personalization

Produce responses with limited context

Can offer choices that alienate participants if not written correctly i.e., there is no response option provided that accurately captures how they think or feel

Are highly susceptible to bias

Can encourage participants to “just pick an answer”

Cannot cover all possible answer options

- When to use closed-ended questions

Like any other data-collection tool, there are specific instances where using closed-ended questions will benefit your team. Consider using closed-ended questions if you need to collect data in the following scenarios:

Surveys with a large sample size

If you’re sending your survey to hundreds or thousands of potential respondents, using closed-ended questions can be a helpful way to increase response rates and simplify your data.

Survey response rates can vary greatly, but even receiving a 10% response rate based on a sample size of multiple thousands of people can result in a ton of analysis work if you ask open-ended questions.

Using well-written, closed-ended questions is a great way to tackle this problem while still collecting meaningful insights that can improve your products and services.

Examples of scenarios where relying on closed-ended questions can be beneficial are:

Sending a customer-experience survey to people who purchased from you in the past month

Collecting demographic information about one of your brand’s customer personas

Surveying your top users about a recent software launch

Quick feedback or check-ins

If you are looking to collect survey results to get a general idea of the current situation, using closed-ended questions can help improve your response rate.

Perfect for employee check-ins or post-purchase customer experience surveys, closed-ended questions can give your team a quick snapshot into the particular metric you’re tracking.

As a great tool for assessing employee satisfaction or doing a quick “vibe check” with your target audience, asking a short closed-ended question like, “Are you happy with the service you receive from our team?” is a great way to collect fast feedback your team can act on.

Time-sensitive inquiries

Do you need to collect some data but you’re on a tight timeline? Improve your response rate and get the insights you need by making your survey quick and easy with closed-ended questions.

Examples of time-sensitive situations perfect for closed-ended questions are:

Asking about a customer’s experience after they connect with your support team

Quickly surveying your team about their current workload before a meeting

Checking for possible tech issues during the first 24 hours of a new feature launch

Measuring customer satisfaction

If you’re looking to gain a better understanding of your customer’s opinions and preferences about your brand, your products or services, or newly launched features, well-written rating-scale questions can be incredibly helpful.

When paired with a few open-ended questions to collect more personalized answers, rating-scale and ranking closed-ended questions can help you collect quantitative data about your customer’s shopping experience, product opinions, and more.

- Analyze closed-ended question data with Dovetail

Closed-ended questions are a helpful tool your team can use when creating a survey or questionnaire to collect specific, easy-to-analyze quantitative data.

Created as a one-stop shop for everything to do with customer insights, Dovetail is a great solution for your research analysis. You will benefit from fast, accurate, and compelling results that will guide your brand’s future decisions.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous survey findings faster?

Do you share your survey findings with others?

Do you analyze survey data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 4 March 2023

Last updated: 28 June 2024

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 20 March 2024

Last updated: 22 February 2024

Last updated: 23 May 2023

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 26 July 2023

Last updated: 14 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2023

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Last updated: 30 January 2024

Latest articles