- What is Strategy?

- Business Models

- Developing a Strategy

- Strategic Planning

- Competitive Advantage

- Growth Strategy

- Market Strategy

- Customer Strategy

- Geographic Strategy

- Product Strategy

- Service Strategy

- Pricing Strategy

- Distribution Strategy

- Sales Strategy

- Marketing Strategy

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Organizational Strategy

- HR Strategy – Organizational Design

- HR Strategy – Employee Journey & Culture

- Process Strategy

- Procurement Strategy

- Cost and Capital Strategy

- Business Value

- Market Analysis

- Problem Solving Skills

- Strategic Options

- Business Analytics

- Strategic Decision Making

- Process Improvement

- Project Planning

- Team Leadership

- Personal Development

- Leadership Maturity Model

- Leadership Team Strategy

- The Leadership Team

- Leadership Mindset

- Communication & Collaboration

- Problem Solving

- Decision Making

- People Leadership

- Strategic Execution

- Executive Coaching

- Strategy Coaching

- Business Transformation

- Strategy Workshops

- Leadership Strategy Survey

- Leadership Training

- Who’s Joe?

“A fact is a simple statement that everyone believes. It is innocent, unless found guilty. A hypothesis is a novel suggestion that no one wants to believe. It is guilty until found effective.”

– Edward Teller, Nuclear Physicist

During my first brainstorming meeting on my first project at McKinsey, this very serious partner, who had a PhD in Physics, looked at me and said, “So, Joe, what are your main hypotheses.” I looked back at him, perplexed, and said, “Ummm, my what?” I was used to people simply asking, “what are your best ideas, opinions, thoughts, etc.” Over time, I began to understand the importance of hypotheses and how it plays an important role in McKinsey’s problem solving of separating ideas and opinions from facts.

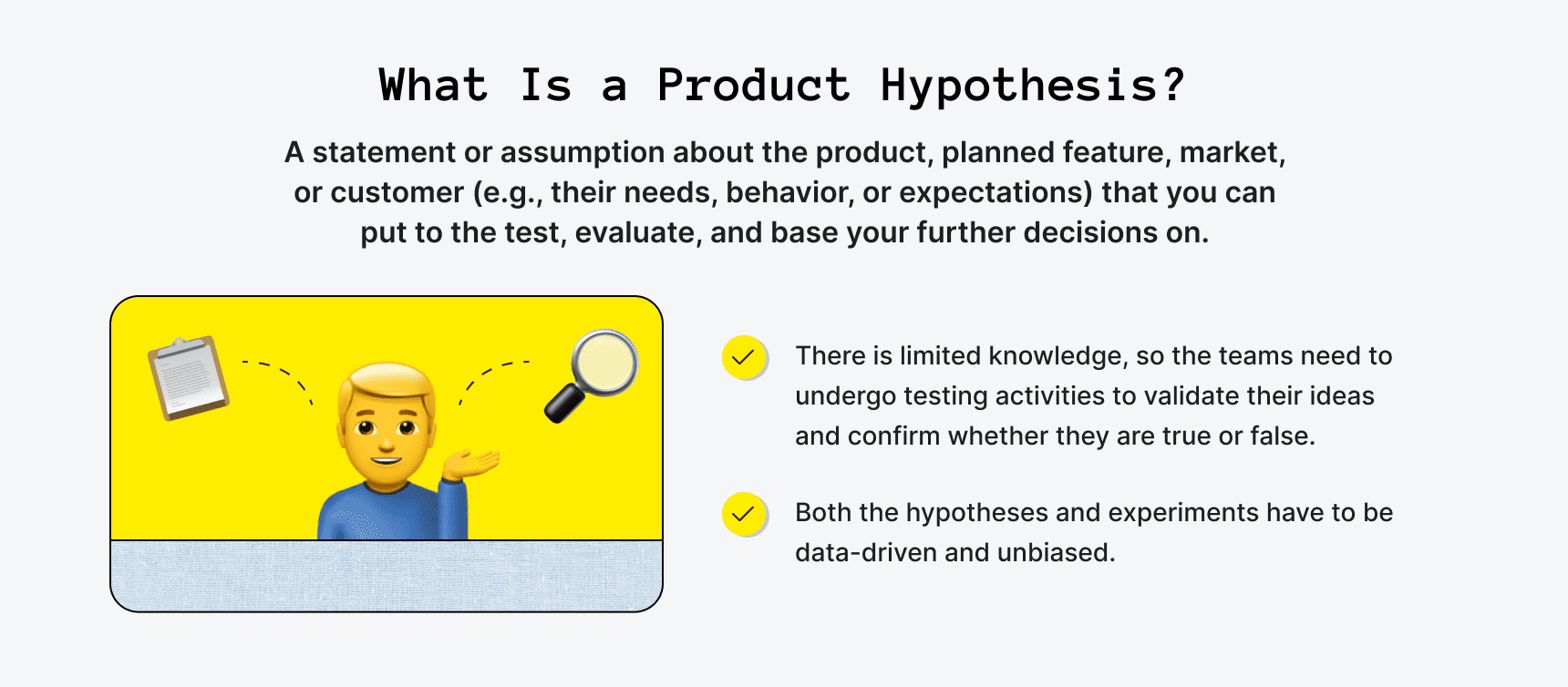

What is a Hypothesis?

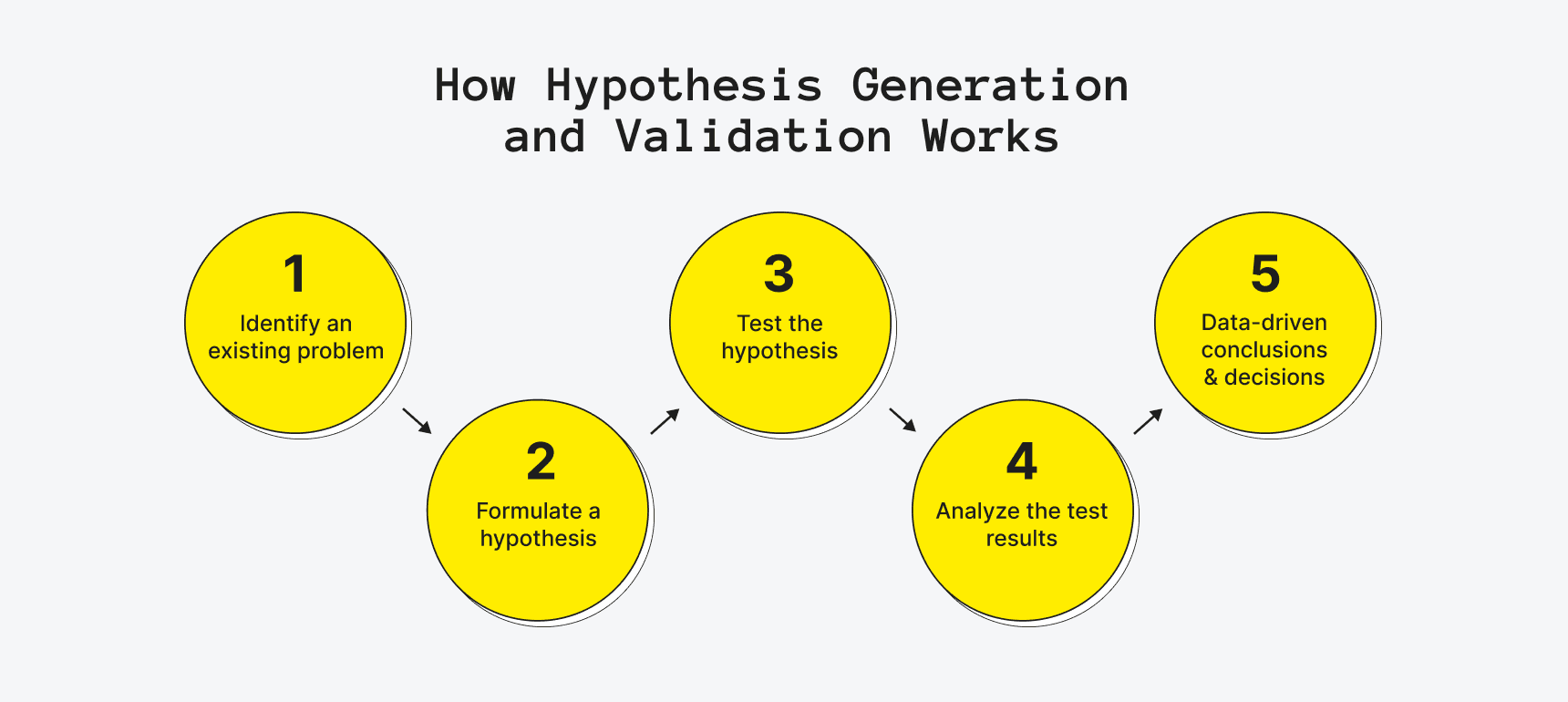

“Hypothesis” is probably one of the top 5 words used by McKinsey consultants. And, being hypothesis-driven was required to have any success at McKinsey. A hypothesis is an idea or theory, often based on limited data, which is typically the beginning of a thread of further investigation to prove, disprove or improve the hypothesis through facts and empirical data.

The first step in being hypothesis-driven is to focus on the highest potential ideas and theories of how to solve a problem or realize an opportunity.

Let’s go over an example of being hypothesis-driven.

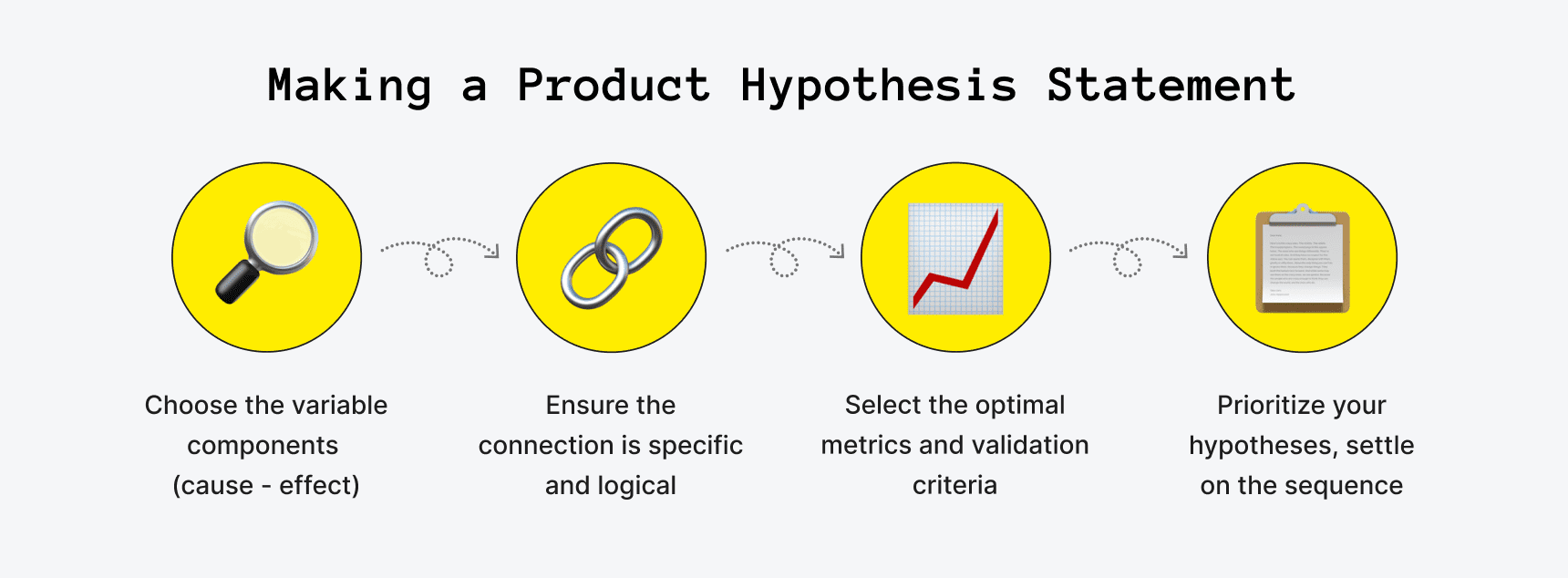

Let’s say you own a website, and you brainstorm ten ideas to improve web traffic, but you don’t have the budget to execute all ten ideas. The first step in being hypothesis-driven is to prioritize the ten ideas based on how much impact you hypothesize they will create.

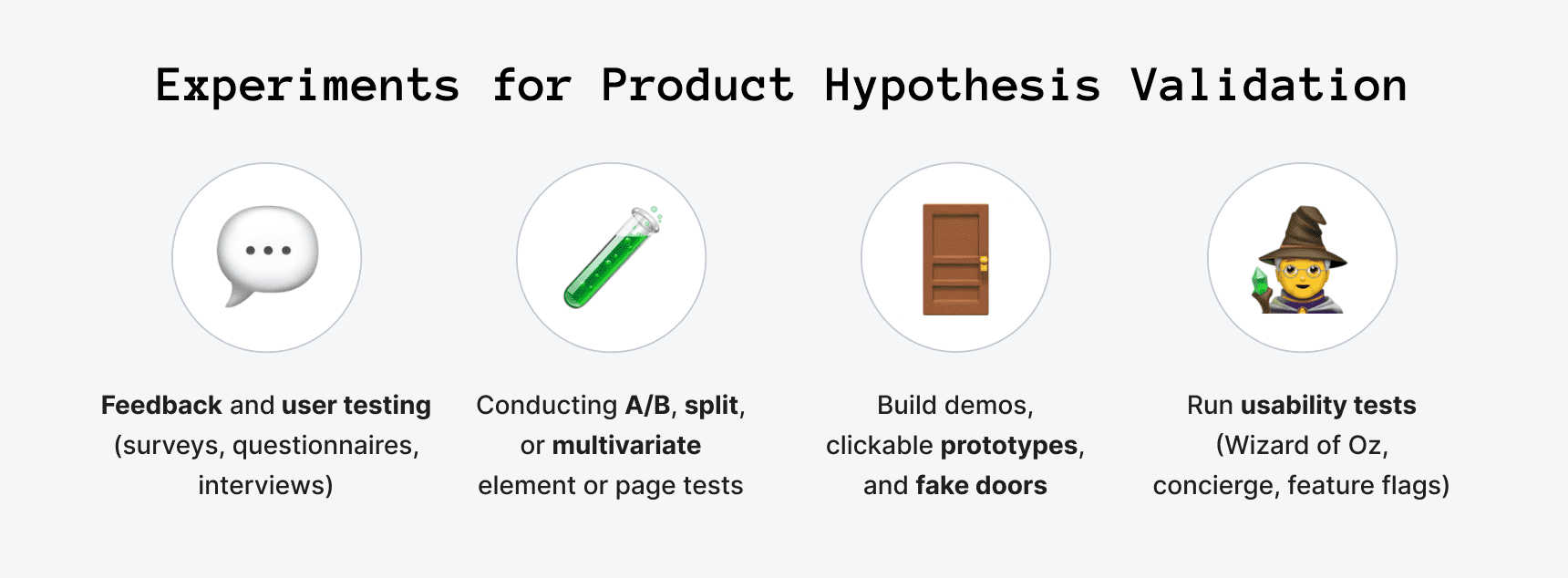

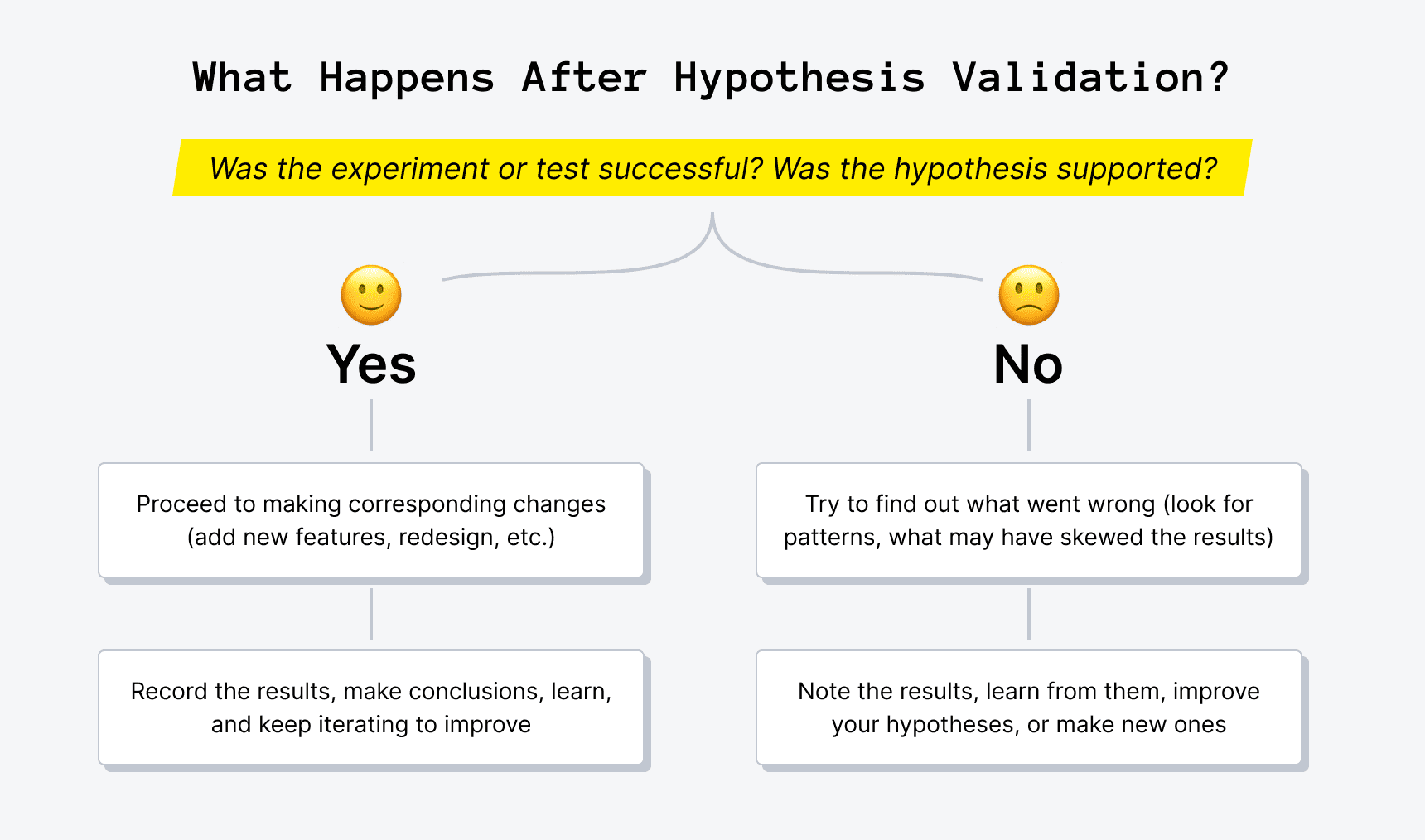

The second step in being hypothesis-driven is to apply the scientific method to your hypotheses by creating the fact base to prove or disprove your hypothesis, which then allows you to turn your hypothesis into fact and knowledge. Running with our example, you could prove or disprove your hypothesis on the ideas you think will drive the most impact by executing:

1. An analysis of previous research and the performance of the different ideas 2. A survey where customers rank order the ideas 3. An actual test of the ten ideas to create a fact base on click-through rates and cost

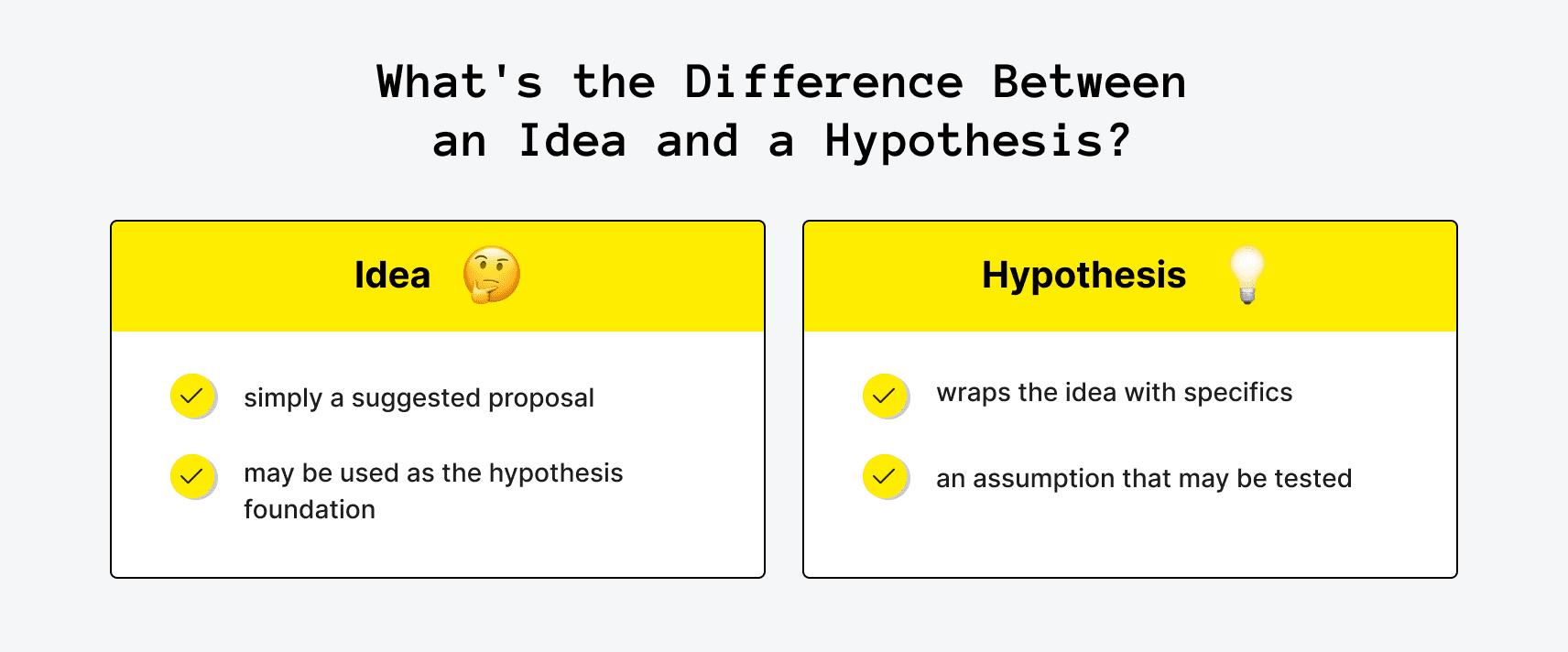

While there are many other ways to validate the hypothesis on your prioritization , I find most people do not take this critical step in validating a hypothesis. Instead, they apply bad logic to many important decisions . An idea pops into their head, and then somehow it just becomes a fact.

One of my favorite lousy logic moments was a CEO who stated,

“I’ve never heard our customers talk about price, so the price doesn’t matter with our products , and I’ve decided we’re going to raise prices.”

Luckily, his management team was able to do a survey to dig deeper into the hypothesis that customers weren’t price-sensitive. Well, of course, they were and through the survey, they built a fantastic fact base that proved and disproved many other important hypotheses.

Why is being hypothesis-driven so important?

Imagine if medicine never actually used the scientific method. We would probably still be living in a world of lobotomies and bleeding people. Many organizations are still stuck in the dark ages, having built a house of cards on opinions disguised as facts, because they don’t prove or disprove their hypotheses. Decisions made on top of decisions, made on top of opinions, steer organizations clear of reality and the facts necessary to objectively evolve their strategic understanding and knowledge. I’ve seen too many leadership teams led solely by gut and opinion. The problem with intuition and gut is if you don’t ever prove or disprove if your gut is right or wrong, you’re never going to improve your intuition. There is a reason why being hypothesis-driven is the cornerstone of problem solving at McKinsey and every other top strategy consulting firm.

How do you become hypothesis-driven?

Most people are idea-driven, and constantly have hypotheses on how the world works and what they or their organization should do to improve. Though, there is often a fatal flaw in that many people turn their hypotheses into false facts, without actually finding or creating the facts to prove or disprove their hypotheses. These people aren’t hypothesis-driven; they are gut-driven.

The conversation typically goes something like “doing this discount promotion will increase our profits” or “our customers need to have this feature” or “morale is in the toilet because we don’t pay well, so we need to increase pay.” These should all be hypotheses that need the appropriate fact base, but instead, they become false facts, often leading to unintended results and consequences. In each of these cases, to become hypothesis-driven necessitates a different framing.

• Instead of “doing this discount promotion will increase our profits,” a hypothesis-driven approach is to ask “what are the best marketing ideas to increase our profits?” and then conduct a marketing experiment to see which ideas increase profits the most.

• Instead of “our customers need to have this feature,” ask the question, “what features would our customers value most?” And, then conduct a simple survey having customers rank order the features based on value to them.

• Instead of “morale is in the toilet because we don’t pay well, so we need to increase pay,” conduct a survey asking, “what is the level of morale?” what are potential issues affecting morale?” and what are the best ideas to improve morale?”

Beyond, watching out for just following your gut, here are some of the other best practices in being hypothesis-driven:

Listen to Your Intuition

Your mind has taken the collision of your experiences and everything you’ve learned over the years to create your intuition, which are those ideas that pop into your head and those hunches that come from your gut. Your intuition is your wellspring of hypotheses. So listen to your intuition, build hypotheses from it, and then prove or disprove those hypotheses, which will, in turn, improve your intuition. Intuition without feedback will over time typically evolve into poor intuition, which leads to poor judgment, thinking, and decisions.

Constantly Be Curious

I’m always curious about cause and effect. At Sports Authority, I had a hypothesis that customers that received service and assistance as they shopped, were worth more than customers who didn’t receive assistance from an associate. We figured out how to prove or disprove this hypothesis by tying surveys to transactional data of customers, and we found the hypothesis was true, which led us to a broad initiative around improving service. The key is you have to be always curious about what you think does or will drive value, create hypotheses and then prove or disprove those hypotheses.

Validate Hypotheses

You need to validate and prove or disprove hypotheses. Don’t just chalk up an idea as fact. In most cases, you’re going to have to create a fact base utilizing logic, observation, testing (see the section on Experimentation ), surveys, and analysis.

Be a Learning Organization

The foundation of learning organizations is the testing of and learning from hypotheses. I remember my first strategy internship at Mercer Management Consulting when I spent a good part of the summer combing through the results, findings, and insights of thousands of experiments that a banking client had conducted. It was fascinating to see the vastness and depth of their collective knowledge base. And, in today’s world of knowledge portals, it is so easy to disseminate, learn from, and build upon the knowledge created by companies.

NEXT SECTION: DISAGGREGATION

DOWNLOAD STRATEGY PRESENTATION TEMPLATES

THE $150 VALUE PACK - 600 SLIDES 168-PAGE COMPENDIUM OF STRATEGY FRAMEWORKS & TEMPLATES 186-PAGE HR & ORG STRATEGY PRESENTATION 100-PAGE SALES PLAN PRESENTATION 121-PAGE STRATEGIC PLAN & COMPANY OVERVIEW PRESENTATION 114-PAGE MARKET & COMPETITIVE ANALYSIS PRESENTATION 18-PAGE BUSINESS MODEL TEMPLATE

JOE NEWSUM COACHING

EXECUTIVE COACHING STRATEGY COACHING ELEVATE360 BUSINESS TRANSFORMATION STRATEGY WORKSHOPS LEADERSHIP STRATEGY SURVEY & WORKSHOP STRATEGY & LEADERSHIP TRAINING

THE LEADERSHIP MATURITY MODEL

Explore other types of strategy.

BIG PICTURE WHAT IS STRATEGY? BUSINESS MODEL COMP. ADVANTAGE GROWTH

TARGETS MARKET CUSTOMER GEOGRAPHIC

VALUE PROPOSITION PRODUCT SERVICE PRICING

GO TO MARKET DISTRIBUTION SALES MARKETING

ORGANIZATIONAL ORG DESIGN HR & CULTURE PROCESS PARTNER

EXPLORE THE TOP 100 STRATEGIC LEADERSHIP COMPETENCIES

TYPES OF VALUE MARKET ANALYSIS PROBLEM SOLVING

OPTION CREATION ANALYTICS DECISION MAKING PROCESS TOOLS

PLANNING & PROJECTS PEOPLE LEADERSHIP PERSONAL DEVELOPMENT

Pursue the Next You in 2024 with 20% Tuition Reduction on September Courses!

An Overview of Management Theories: Classical, Behavioral, and Modern Approaches

Last Updated June 30, 2022

In both theory and practice, business management is at a crisis point . The world is changing — and changing quickly. There is no single management philosophy that answers every need. The best managers are flexible and blend methods. They adapt several management theories as needed to handle new situations.

Some people may believe in the Great Man Theory of Leadership . Others know that management is like anything else: Practice and education improve performance. Understanding different management theories help managers prioritize the processes, relationships and information that impact an organization’s success.

How should a leader set goals and guide their teams to realize them? Many heads are better than one, and this article covers three types of management approaches and many of the individual theories categorized within them.

Three Types of Management Theories

While ideas overlap between the categories, these three classifications differentiate management according to their focus and the era they came from:

- Classical management theory: emerged from the Industrial Revolution and revolves around maximizing efficiency and production.

- Behavioral management theory: started in the early 20 th century and addresses the organization’s human and social elements.

- Modern management theory: followed on the heels of World War II and combines mathematical principles with sociology to develop holistic approaches to management.

The origin of one movement doesn’t indicate the conclusion of the previous one. All three of these approaches still exist in contemporary practice.

Newer is not always better either. Each philosophy was born out of changing ideals and emerging possibilities, but today’s business world is complex. Different theories better suit different needs.

Classical Management Theory

Classical management theory prioritizes profit and assumes that personal gain motivates employees. It aims to streamline operations and increase productivity.

Major concepts include specialization, incentivization, and hierarchical structure. The first two contribute to employee efficiency and drive. Centralized leadership simplifies decision-making, and a meritocratic chain of commands provides order and oversight. At every level, standardization reduces waste and error.

There are many strengths to classical management theory. It provides clarity for both the organization and its personnel, and specialization and sound hiring practices place employees in positions they can handle and even master.

Shortcomings of classical management theory can include:

- The treatment of workers as machines without accounting for the role job satisfaction and workplace culture play in an organization’s success

- The difficulty of applying some of its principles outside a limited manufacturing context

- A top-down approach to communication that neglects employee input and prevents collaboration

- Failure to provide for creativity and innovation, which rigid structures and hyper specialization can stifle

The following management approaches belong to the overarching category of classical management theory:

Scientific Management Theory

Scientific management theory is sometimes called Taylorism after its founder Frederick Winslow Taylor, a mechanical engineer. Taylor employed scientific methods to develop organizational principles that suited mass production needs. After creating and proving his theory as a manager and consultant, he wrote ” The Principles of Scientific Management ” in 1911.

Taylor wanted to replace outdated, “rule-of-thumb” methods with more efficient processes. To this end, he identified four core principles of good management. The manager:

- Develops a science consisting of best practices for all elements of their employees’ work

- Selects and trains employees accordingly

- Works with employees to ensure that the science is followed

- Assumes half the responsibility for all work through process development, guidance, and maintenance

Today, many companies have adopted a version of the scientific management theory . By standardizing tools and procedures, they hope to increase productivity and reduce the reliance on individual talent and workers.

Bureaucratic Management Theory

Max Weber was one of the foremost scholars of the late 19 th and early 20 th century. He strongly influenced — and continues to influence — economic, religious, and political sociology. He explains bureaucratic management theory in “ Economy and Society ,” published posthumously in 1922.

Weber believed that standard rules and well-defined roles maximize the efficiency of an organization. Everyone should understand the responsibilities and expectations of their position, their place within a clear hierarchy and general corporate policies. Hiring decisions and the application of rules should be impersonal, guided only by reason and established codes.

Weber’s theory provides for orderly and scalable institutions. At least some element of bureaucracy informs most large organizations, whether they’re public, private, or profit driven.

Administrative Management Theory

Just as scientific management theory is sometimes called Taylorism, administrative management theory is sometimes called Fayolism.

Henri Fayol was a mining engineer who sought to codify the responsibilities of management and the principles of effective administration. He outlined these in “ General and Industrial Management ” in 1916.

His guide identifies 14 principles of management:

- Division of work: Divide work into tasks and between employees.

- Authority: Balance responsibility with commensurate authority.

- Unity of command: Give each employee one direct manager.

- Unity of direction: Align goals between employees.

- Equity: Treat all employees equally.

- Order: Maintain order through an organized workforce.

- Discipline: Establish and follow rules and regulations.

- Initiative: Encourage employees to show initiative.

- Remuneration: Pay employees fairly for the work they do.

- Stability: Ensure that employees feel secure in their positions.

- Scalar chain: Establish a clear hierarchy of command.

- Subordination of individual interest: Prioritize group needs.

- Esprit de corps: Inspire group unity and pride.

- A balance between centralization and delegation: Concentrate ultimate authority but delegate individual decisions.

According to Fayol, managers need to develop practices that foster each of the 14 principles.

Behavioral Management Theory

Behavioral management theory places the person rather than the process at the heart of business operations. It examines the business as a social system as well as a formal organization. Therefore, productivity depends on proper motivation, group dynamics, personal psychology, and efficient processes.

Behavioral management theory humanizes business. Feelings have a practical impact on operations. Team spirit, public recognition, and personal pride encourage employees to perform better. Individual relationships also play a role. Employees are more likely to go the extra mile for a boss they respect and who respects them.

Shortcomings of behavioral management theory include:

- The difficulty of balancing personal relationships with professional conduct

- An inclination toward socially motivated hiring practices that can be unjust

- The danger of assuming that all individuals respond the same way to the same situations and for the same reasons

Common behavioral management theories include the following:

Human Relations Theory

The fundamental texts on human relations theory evolved from an experiment following classical theory. Elton Mayo worked as part of a team evaluating the impact on the productivity of various workplace conditions at the Hawthorne Works, a large factory complex. Early results were self-contradicting; changes in opposite directions both improved productivity.

Mayo realized that the researchers’ attention to the workers was the common factor. It instilled pride and fulfilled particular social needs of the workers. This led to the development of the “Hawthorne effect,” a principle of research that suggests researcher attention affects the subjects in a study and impacts the results.

In business management, the Hawthorne studies led to articulating the role that human relations play in business operations. Mayo and later theorists developed several related conclusions, including:

- Group dynamics affect job performance.

- Communication between employees and employers must go in both directions.

- Production standards depend more on workplace culture than on official objectives.

- In addition to compensation, perceived value affects performance.

- Workers prefer to participate in the decision-making process.

- Integration between departments or groups positively impacts an organization.

In the modern workplace, sanctioned social activities and open, defined communication channels owe a debt to human relations theory.

Theory X and Theory Y

Douglas McGregor primarily investigated the way managers motivate their employees. The same tactics don’t work across the board, and individuals require different types of oversight or encouragement. In 1960, McGregor developed Theory X and Theory Y in response, laid out in “ The Human Side of Enterprise .”

This management theory divides workers into two camps that require two leadership styles. Theory X workers lack drive. Managers need to provide large amounts of structure and direction to get them to accomplish the necessary work. These workers demand an authoritarian style of management.

Theory Y workers are self-motivated individuals who enjoy their work and find it fulfilling. They benefit from a more participative environment that fosters growth and development.

McGregor’s theory of differentiated management practices remains relevant, but neither workers nor managers tend to exist at the extreme ends of what should be a more nuanced spectrum. The approach also neglects the reciprocal effect managers and workers can have on one another. A natural self-starter can have their ambition micromanaged out of them.

Modern Management Theory

Modern management theory adopts an approach to management that balances scientific methodology with humanistic psychology. It uses emerging technologies and statistical analysis to make decisions, streamline operations and quantify performance. At the same time, it values individual job satisfaction and a healthy corporate culture.

This category of theories is more holistic and flexible than its predecessors. Data-driven decisions can remove human bias while still accommodating employee health and happiness indicators. Modern management theory also allows organizations to adapt to complex, fluid situations with local solutions instead of positing a single, overriding principle to drive management.

Shortcomings of the modern management approach include:

- The prioritization of information that can be difficult, expensive, and time-consuming to collect

- The gap between theoretical flexibility and practical agility

- The tendency of some strains to be descriptive rather than prescriptive

Two popular strains of modern management theory are systems theory and contingency theory:

Systems Management Theory

It’s no surprise that Ludwig Von Bertalanffy, who developed systems management theory, was a biologist. This theory borrows heavily from that discourse. Systems theory proposes that each business is like a single living organism. Distinct elements play different roles but ultimately work together to support the business’s health. The role of management is to facilitate cooperation and holistic process flows.

Systems management theory sometimes leans more toward metaphorical description than prescriptive application. However, you can see evidence of the approach in technological architectures and tools that standardize services and open access to information. For example, innovations such as data fabric help break down departmental silos.

Contingency Management Theory

Contingency management theory addresses the complexity and variability of the modern work environment. Fred Fiedler realized that no one set of characteristics – no single approach – provided the best leadership in all situations. Success instead depended on the leader’s suitability to the situation in which they found themselves.

Fiedler focused on three factors that determine that situation:

- Task structure: How well defined is the job?

- Leader-member relations: How well does the leader work with team members?

- Leader position power: How much authority does the leader have? To what extent can they distribute punishments and rewards?

Managers can be classified as having a task-oriented or a people-oriented style. Task-oriented managers organize teams to accomplish projects quickly and effectively. People-oriented managers are good at handling team conflict, building relationships, and facilitating synergy. Task-oriented leaders thrive in both highly favorable and unfavorable conditions, but people-oriented leaders do better in more moderate configurations.

The least-preferred coworker (LPC) scale is a common management tool developed by Fiedler to help leaders pinpoint their style. The scale asks you to identify the coworker you have the hardest time working with and rate them. Relationship-oriented managers tend to score higher on the LPC scale than task-oriented managers.

What’s Next for Management Theory?

It’s time for a new category of management theory. The business world requires more than a single new idea, and it’s ripe for a constellation of new theories.

Ecology and technology continue to reshape our concerns, resources, and possibilities. Remote work physically distances coworkers, and worldwide health and climate concerns create fragile relationships with globalization. Equity is no longer “a nice idea” but an urgent imperative. Volatile conditions lead people to search for meaning at work and everywhere else.

No one truly knows what’s next. But it will likely build on and cherry-pick from the above management approaches, reorienting them around a new philosophical core. Familiarize yourself with predominant principles today and prepare yourself for a new movement tomorrow.

Related Articles

Take the next step in your career with a program guide!

By completing this form and clicking the button below, I consent to receiving calls, text messages and/or emails from BISK, its client institutions, and their representatives regarding educational services and programs. I understand calls and texts may be directed to the number I provide using automatic dialing technology. I understand that this consent is not required to purchase goods or services. If you would like more information relating to how we may use your data, please review our privacy policy .

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Creating Brand Value

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

A Beginner’s Guide to Hypothesis Testing in Business

- 30 Mar 2021

Becoming a more data-driven decision-maker can bring several benefits to your organization, enabling you to identify new opportunities to pursue and threats to abate. Rather than allowing subjective thinking to guide your business strategy, backing your decisions with data can empower your company to become more innovative and, ultimately, profitable.

If you’re new to data-driven decision-making, you might be wondering how data translates into business strategy. The answer lies in generating a hypothesis and verifying or rejecting it based on what various forms of data tell you.

Below is a look at hypothesis testing and the role it plays in helping businesses become more data-driven.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is Hypothesis Testing?

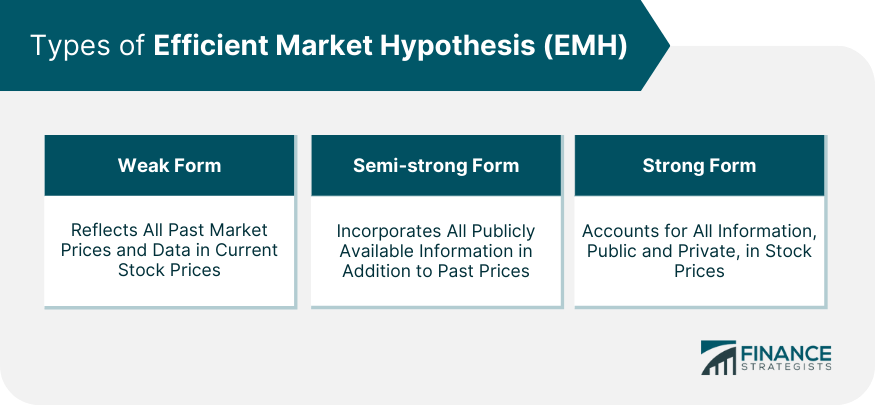

To understand what hypothesis testing is, it’s important first to understand what a hypothesis is.

A hypothesis or hypothesis statement seeks to explain why something has happened, or what might happen, under certain conditions. It can also be used to understand how different variables relate to each other. Hypotheses are often written as if-then statements; for example, “If this happens, then this will happen.”

Hypothesis testing , then, is a statistical means of testing an assumption stated in a hypothesis. While the specific methodology leveraged depends on the nature of the hypothesis and data available, hypothesis testing typically uses sample data to extrapolate insights about a larger population.

Hypothesis Testing in Business

When it comes to data-driven decision-making, there’s a certain amount of risk that can mislead a professional. This could be due to flawed thinking or observations, incomplete or inaccurate data , or the presence of unknown variables. The danger in this is that, if major strategic decisions are made based on flawed insights, it can lead to wasted resources, missed opportunities, and catastrophic outcomes.

The real value of hypothesis testing in business is that it allows professionals to test their theories and assumptions before putting them into action. This essentially allows an organization to verify its analysis is correct before committing resources to implement a broader strategy.

As one example, consider a company that wishes to launch a new marketing campaign to revitalize sales during a slow period. Doing so could be an incredibly expensive endeavor, depending on the campaign’s size and complexity. The company, therefore, may wish to test the campaign on a smaller scale to understand how it will perform.

In this example, the hypothesis that’s being tested would fall along the lines of: “If the company launches a new marketing campaign, then it will translate into an increase in sales.” It may even be possible to quantify how much of a lift in sales the company expects to see from the effort. Pending the results of the pilot campaign, the business would then know whether it makes sense to roll it out more broadly.

Related: 9 Fundamental Data Science Skills for Business Professionals

Key Considerations for Hypothesis Testing

1. alternative hypothesis and null hypothesis.

In hypothesis testing, the hypothesis that’s being tested is known as the alternative hypothesis . Often, it’s expressed as a correlation or statistical relationship between variables. The null hypothesis , on the other hand, is a statement that’s meant to show there’s no statistical relationship between the variables being tested. It’s typically the exact opposite of whatever is stated in the alternative hypothesis.

For example, consider a company’s leadership team that historically and reliably sees $12 million in monthly revenue. They want to understand if reducing the price of their services will attract more customers and, in turn, increase revenue.

In this case, the alternative hypothesis may take the form of a statement such as: “If we reduce the price of our flagship service by five percent, then we’ll see an increase in sales and realize revenues greater than $12 million in the next month.”

The null hypothesis, on the other hand, would indicate that revenues wouldn’t increase from the base of $12 million, or might even decrease.

Check out the video below about the difference between an alternative and a null hypothesis, and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more explainer content.

2. Significance Level and P-Value

Statistically speaking, if you were to run the same scenario 100 times, you’d likely receive somewhat different results each time. If you were to plot these results in a distribution plot, you’d see the most likely outcome is at the tallest point in the graph, with less likely outcomes falling to the right and left of that point.

With this in mind, imagine you’ve completed your hypothesis test and have your results, which indicate there may be a correlation between the variables you were testing. To understand your results' significance, you’ll need to identify a p-value for the test, which helps note how confident you are in the test results.

In statistics, the p-value depicts the probability that, assuming the null hypothesis is correct, you might still observe results that are at least as extreme as the results of your hypothesis test. The smaller the p-value, the more likely the alternative hypothesis is correct, and the greater the significance of your results.

3. One-Sided vs. Two-Sided Testing

When it’s time to test your hypothesis, it’s important to leverage the correct testing method. The two most common hypothesis testing methods are one-sided and two-sided tests , or one-tailed and two-tailed tests, respectively.

Typically, you’d leverage a one-sided test when you have a strong conviction about the direction of change you expect to see due to your hypothesis test. You’d leverage a two-sided test when you’re less confident in the direction of change.

4. Sampling

To perform hypothesis testing in the first place, you need to collect a sample of data to be analyzed. Depending on the question you’re seeking to answer or investigate, you might collect samples through surveys, observational studies, or experiments.

A survey involves asking a series of questions to a random population sample and recording self-reported responses.

Observational studies involve a researcher observing a sample population and collecting data as it occurs naturally, without intervention.

Finally, an experiment involves dividing a sample into multiple groups, one of which acts as the control group. For each non-control group, the variable being studied is manipulated to determine how the data collected differs from that of the control group.

Learn How to Perform Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis testing is a complex process involving different moving pieces that can allow an organization to effectively leverage its data and inform strategic decisions.

If you’re interested in better understanding hypothesis testing and the role it can play within your organization, one option is to complete a course that focuses on the process. Doing so can lay the statistical and analytical foundation you need to succeed.

Do you want to learn more about hypothesis testing? Explore Business Analytics —one of our online business essentials courses —and download our Beginner’s Guide to Data & Analytics .

About the Author

- Data, AI, & Machine Learning

- Managing Technology

- Social Responsibility

- Workplace, Teams, & Culture

- AI & Machine Learning

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Big ideas Research Projects

- Artificial Intelligence and Business Strategy

- Responsible AI

- Future of the Workforce

- Future of Leadership

- All Research Projects

- AI in Action

- Most Popular

- The Truth Behind the Nursing Crisis

- Coaching for the Future-Forward Leader

- Measuring Culture

Our summer 2024 issue highlights ways to better support customers, partners, and employees, while our special report shows how organizations can advance their AI practice.

- Past Issues

- Upcoming Events

- Video Archive

- Me, Myself, and AI

- Three Big Points

Why Hypotheses Beat Goals

- Developing Strategy

- Skills & Learning

Not long ago, it became fashionable to embrace failure as a sign of a company’s willingness to take risks. This trend lost favor as executives recognized that what they wanted was learning, not necessarily failure. Every failure can be attributed to a raft of missteps, and many failures do not automatically contribute to future success.

Certainly, if companies want to aggressively pursue learning, they must accept that failures will happen. But the practice of simply setting goals and then being nonchalant if they fail is inadequate.

Instead, companies should focus organizational energy on hypothesis generation and testing. Hypotheses force individuals to articulate in advance why they believe a given course of action will succeed. A failure then exposes an incorrect hypothesis — which can more reliably convert into organizational learning.

What Exactly Is a Hypothesis?

When my son was in second grade, his teacher regularly introduced topics by asking students to state some initial assumptions. For example, she introduced a unit on whales by asking: How big is a blue whale? The students all knew blue whales were big, but how big? Guesses ranged from the size of the classroom to the size of two elephants to the length of all the students in class lined up in a row. Students then set out to measure the classroom and the length of the row they formed, and they looked up the size of an elephant. They compared their results with the measurements of the whale and learned how close their estimates were.

Note that in this example, there is much more going on than just learning the size of a whale. Students were learning to recognize assumptions, make intelligent guesses based on those assumptions, determine how to test the accuracy of their guesses, and then assess the results.

This is the essence of hypothesis generation. A hypothesis emerges from a set of underlying assumptions. It is an articulation of how those assumptions are expected to play out in a given context. In short, a hypothesis is an intelligent, articulated guess that is the basis for taking action and assessing outcomes.

Get Updates on Transformative Leadership

Evidence-based resources that can help you lead your team more effectively, delivered to your inbox monthly.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up

Privacy Policy

Hypothesis generation in companies becomes powerful if people are forced to articulate and justify their assumptions. It makes the path from hypothesis to expected outcomes clear enough that, should the anticipated outcomes fail to materialize, people will agree that the hypothesis was faulty.

Building a culture of effective hypothesizing can lead to more thoughtful actions and a better understanding of outcomes. Not only will failures be more likely to lead to future successes, but successes will foster future successes.

Why Is Hypothesis Generation Important?

Digital technologies are creating new business opportunities, but as I’ve noted in earlier columns , companies must experiment to learn both what is possible and what customers want. Most companies are relying on empowered, agile teams to conduct these experiments. That’s because teams can rapidly hypothesize, test, and learn.

Hypothesis generation contrasts starkly with more traditional management approaches designed for process optimization. Process optimization involves telling employees both what to do and how to do it. Process optimization is fine for stable business processes that have been standardized for consistency. (Standardized processes can usually be automated, specifically because they are stable.) Increasingly, however, companies need their people to steer efforts that involve uncertainty and change. That’s when organizational learning and hypothesis generation are particularly important.

Shifting to a culture that encourages empowered teams to hypothesize isn’t easy. Established hierarchies have developed managers accustomed to directing employees on how to accomplish their objectives. Those managers invariably rose to power by being the smartest person in the room. Such managers can struggle with the requirements for leading empowered teams. They may recognize the need to hold teams accountable for outcomes rather than specific tasks, but they may not be clear about how to guide team efforts.

Some newer companies have baked this concept into their organizational structure. Leaders at the Swedish digital music service Spotify note that it is essential to provide clear missions to teams . A clear mission sets up a team to articulate measurable goals. Teams can then hypothesize how they can best accomplish those goals. The role of leaders is to quiz teams about their hypotheses and challenge their logic if those hypotheses appear to lack support.

A leader at another company told me that accountability for outcomes starts with hypotheses. If a team cannot articulate what it intends to do and what outcomes it anticipates, it is unlikely that team will deliver on its mission. In short, the success of empowered teams depends upon management shifting from directing employees to guiding their development of hypotheses. This is how leaders hold their teams accountable for outcomes.

Members of empowered teams are not the only people who need to hone their ability to hypothesize. Leaders in companies that want to seize digital opportunities are learning through their experiments which strategies hold real promise for future success. They must, in effect, hypothesize about what will make the company successful in a digital economy. If they take the next step and articulate those hypotheses and establish metrics for assessing the outcomes of their actions, they will facilitate learning about the company’s long-term success. Hypothesis generation can become a critical competency throughout a company.

How Does a Company Become Proficient at Hypothesizing?

Most business leaders have embraced the importance of evidence-based decision-making. But developing a culture of evidence-based decision-making by promoting hypothesis generation is a new challenge.

For one thing, many hypotheses are sloppy. While many people naturally hypothesize and take actions based on their hypotheses, their underlying assumptions may go unexamined. Often, they don’t clearly articulate the premise itself. The better hypotheses are straightforward and succinctly written. They’re pointed about the suppositions they’re based on. And they’re shared, allowing an audience to examine the assumptions (are they accurate?) and the postulate itself (is it an intelligent, articulated guess that is the basis for taking action and assessing outcomes?).

Related Articles

Seven-Eleven Japan offers a case in how do to hypotheses right.

For over 30 years, Seven-Eleven Japan was the most profitable retailer in Japan. It achieved that stature by relying on each store’s salesclerks to decide what items to stock on that store’s shelves. Many of the salesclerks were part-time, but they were each responsible for maximizing turnover for one part of the store’s inventory, and they received detailed reports so they could monitor their own performance.

The language of hypothesis formulation was part of their process. Each week, Seven-Eleven Japan counselors visited the stores and asked salesclerks three questions:

- What did you hypothesize this week? (That is, what did you order?)

- How did you do? (That is, did you sell what you ordered?)

- How will you do better next week? (That is, how will you incorporate the learning?)

By repeatedly asking these questions and checking the data for results, counselors helped people throughout the company hypothesize, test, and learn. The result was consistently strong inventory turnover and profitability.

How can other companies get started on this path? Evidence-based decision-making requires data — good data, as the Seven-Eleven Japan example shows. But rather than get bogged down with the limits of a company’s data, I would argue that companies can start to change their culture by constantly exposing individual hypotheses. Those hypotheses will highlight what data matters most — and the need of teams to test hypotheses will help generate enthusiasm for cleaning up bad data. A sense of accountability for generating and testing hypotheses then fosters a culture of evidence-based decision-making.

The uncertainties and speed of change in the current business environment render traditional management approaches ineffective. To create the agile, evidence-based, learning culture your business needs to succeed in a digital economy, I suggest that instead of asking What is your goal? you make it a habit to ask What is your hypothesis?

About the Author

Jeanne Ross is principal research scientist for MIT’s Center for Information Systems Research . Follow CISR on Twitter @mit_cisr .

More Like This

Add a comment cancel reply.

You must sign in to post a comment. First time here? Sign up for a free account : Comment on articles and get access to many more articles.

Comment (1)

Richard jones.

What Is A Research (Scientific) Hypothesis? A plain-language explainer + examples

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

If you’re new to the world of research, or it’s your first time writing a dissertation or thesis, you’re probably noticing that the words “research hypothesis” and “scientific hypothesis” are used quite a bit, and you’re wondering what they mean in a research context .

“Hypothesis” is one of those words that people use loosely, thinking they understand what it means. However, it has a very specific meaning within academic research. So, it’s important to understand the exact meaning before you start hypothesizing.

Research Hypothesis 101

- What is a hypothesis ?

- What is a research hypothesis (scientific hypothesis)?

- Requirements for a research hypothesis

- Definition of a research hypothesis

- The null hypothesis

What is a hypothesis?

Let’s start with the general definition of a hypothesis (not a research hypothesis or scientific hypothesis), according to the Cambridge Dictionary:

Hypothesis: an idea or explanation for something that is based on known facts but has not yet been proved.

In other words, it’s a statement that provides an explanation for why or how something works, based on facts (or some reasonable assumptions), but that has not yet been specifically tested . For example, a hypothesis might look something like this:

Hypothesis: sleep impacts academic performance.

This statement predicts that academic performance will be influenced by the amount and/or quality of sleep a student engages in – sounds reasonable, right? It’s based on reasonable assumptions , underpinned by what we currently know about sleep and health (from the existing literature). So, loosely speaking, we could call it a hypothesis, at least by the dictionary definition.

But that’s not good enough…

Unfortunately, that’s not quite sophisticated enough to describe a research hypothesis (also sometimes called a scientific hypothesis), and it wouldn’t be acceptable in a dissertation, thesis or research paper . In the world of academic research, a statement needs a few more criteria to constitute a true research hypothesis .

What is a research hypothesis?

A research hypothesis (also called a scientific hypothesis) is a statement about the expected outcome of a study (for example, a dissertation or thesis). To constitute a quality hypothesis, the statement needs to have three attributes – specificity , clarity and testability .

Let’s take a look at these more closely.

Need a helping hand?

Hypothesis Essential #1: Specificity & Clarity

A good research hypothesis needs to be extremely clear and articulate about both what’ s being assessed (who or what variables are involved ) and the expected outcome (for example, a difference between groups, a relationship between variables, etc.).

Let’s stick with our sleepy students example and look at how this statement could be more specific and clear.

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

As you can see, the statement is very specific as it identifies the variables involved (sleep hours and test grades), the parties involved (two groups of students), as well as the predicted relationship type (a positive relationship). There’s no ambiguity or uncertainty about who or what is involved in the statement, and the expected outcome is clear.

Contrast that to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – and you can see the difference. “Sleep” and “academic performance” are both comparatively vague , and there’s no indication of what the expected relationship direction is (more sleep or less sleep). As you can see, specificity and clarity are key.

Hypothesis Essential #2: Testability (Provability)

A statement must be testable to qualify as a research hypothesis. In other words, there needs to be a way to prove (or disprove) the statement. If it’s not testable, it’s not a hypothesis – simple as that.

For example, consider the hypothesis we mentioned earlier:

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

We could test this statement by undertaking a quantitative study involving two groups of students, one that gets 8 or more hours of sleep per night for a fixed period, and one that gets less. We could then compare the standardised test results for both groups to see if there’s a statistically significant difference.

Again, if you compare this to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – you can see that it would be quite difficult to test that statement, primarily because it isn’t specific enough. How much sleep? By who? What type of academic performance?

So, remember the mantra – if you can’t test it, it’s not a hypothesis 🙂

Defining A Research Hypothesis

You’re still with us? Great! Let’s recap and pin down a clear definition of a hypothesis.

A research hypothesis (or scientific hypothesis) is a statement about an expected relationship between variables, or explanation of an occurrence, that is clear, specific and testable.

So, when you write up hypotheses for your dissertation or thesis, make sure that they meet all these criteria. If you do, you’ll not only have rock-solid hypotheses but you’ll also ensure a clear focus for your entire research project.

What about the null hypothesis?

You may have also heard the terms null hypothesis , alternative hypothesis, or H-zero thrown around. At a simple level, the null hypothesis is the counter-proposal to the original hypothesis.

For example, if the hypothesis predicts that there is a relationship between two variables (for example, sleep and academic performance), the null hypothesis would predict that there is no relationship between those variables.

At a more technical level, the null hypothesis proposes that no statistical significance exists in a set of given observations and that any differences are due to chance alone.

And there you have it – hypotheses in a nutshell.

If you have any questions, be sure to leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to help you. If you need hands-on help developing and testing your hypotheses, consider our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the research journey.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

17 Comments

Very useful information. I benefit more from getting more information in this regard.

Very great insight,educative and informative. Please give meet deep critics on many research data of public international Law like human rights, environment, natural resources, law of the sea etc

In a book I read a distinction is made between null, research, and alternative hypothesis. As far as I understand, alternative and research hypotheses are the same. Can you please elaborate? Best Afshin

This is a self explanatory, easy going site. I will recommend this to my friends and colleagues.

Very good definition. How can I cite your definition in my thesis? Thank you. Is nul hypothesis compulsory in a research?

It’s a counter-proposal to be proven as a rejection

Please what is the difference between alternate hypothesis and research hypothesis?

It is a very good explanation. However, it limits hypotheses to statistically tasteable ideas. What about for qualitative researches or other researches that involve quantitative data that don’t need statistical tests?

In qualitative research, one typically uses propositions, not hypotheses.

could you please elaborate it more

I’ve benefited greatly from these notes, thank you.

This is very helpful

well articulated ideas are presented here, thank you for being reliable sources of information

Excellent. Thanks for being clear and sound about the research methodology and hypothesis (quantitative research)

I have only a simple question regarding the null hypothesis. – Is the null hypothesis (Ho) known as the reversible hypothesis of the alternative hypothesis (H1? – How to test it in academic research?

this is very important note help me much more

Hi” best wishes to you and your very nice blog”

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- What Is Research Methodology? Simple Definition (With Examples) - Grad Coach - […] Contrasted to this, a quantitative methodology is typically used when the research aims and objectives are confirmatory in nature. For example,…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Module 1: Introduction to Organizational Behavior

History of management theory, learning outcomes.

- Describe the history of management theory

So what is management theory? First, let’s break down the term. Theories help us understand our experiences by using research and observable facts. Management is the act of supervising and directing people, tasks, and things [1] . So, simply put, management theory is a collection of understandings and findings that help managers best support their teams and goals.

The Importance of Management Theories

Management theories help organizations to focus, communicate, and evolve. Using management theory in the workplace allows leadership to focus on their main goals. When a management style or theory is implemented, it automatically streamlines the top priorities for the organization. Management theory also allows us to better communicate with people we work with which in turn allows us to work more efficiently. By understanding management theory, basic assumptions about management styles and goals can be assumed and can save time during daily interactions and meetings within an organization.

Theories can only reach so far, and management theories are no exception. There is no such thing as a one-size-fits-all management theory. What may work for one organization may not be relevant for another. Therefore, when one theory does not fit a particular situation, it is important to explore the option of developing a new theory that would lead in a new, more applicable direction. While some theories can stand the test of time, other theories may grow to be irrelevant and new theories will develop in their place.

The Evolution of Management Theory

While the next section will get into the nitty-gritty behind the history of different types of management theory, it is important to have a basic understanding as to why management theory was such an important and ground-breaking idea. The Industrial Revolution is at the center of management theory. From the late 1700s through the early 1900s, the Industrial Revolution brought extraordinary change to the workplace and forever transformed the way companies operate.

While productivity goals can be set easily, managing a team to meet productivity goals was not so simple. For the first time, managers had to find new and innovative ways to motivate a sizable number of employees to perform. Since this was a new concept, research, observations, experiments, and trial and error were all used to find new and better ways to manage employees. The Industrial Revolution gave birth to a variety of management theories and concepts, many of which are still relevant and essential in today’s workforce. In addition, many management theories have developed since the end of the Industrial Revolution as society continues to evolve. Each management theory plays a role in modern management theory and how it is implemented.

PRactice Question

Let’s take a look at some key management theories, explore their history and reasoning, and learn about the masterminds behind them.

- Taylor, F. W. (1914). The Principles of Scientific Management . Harper. ↵

- History of Management Theory. Authored by : Freedom Learning Group. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Untitled. Authored by : Elevate. Provided by : Unsplash. Located at : https://unsplash.com/photos/rT1lK2GEVdg . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved . License Terms : Unsplash License

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Definition, Format, Examples, and Tips

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis.

- Operationalization

Hypothesis Types

Hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. It is a preliminary answer to your question that helps guide the research process.

Consider a study designed to examine the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance. The hypothesis might be: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

At a Glance

A hypothesis is crucial to scientific research because it offers a clear direction for what the researchers are looking to find. This allows them to design experiments to test their predictions and add to our scientific knowledge about the world. This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. At this point, researchers then begin to develop a testable hypothesis.

Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore numerous factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk adage that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

How to Formulate a Good Hypothesis

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

The Importance of Operational Definitions

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

Operational definitions are specific definitions for all relevant factors in a study. This process helps make vague or ambiguous concepts detailed and measurable.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in various ways. Clearly defining these variables and how they are measured helps ensure that other researchers can replicate your results.

Replicability

One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable.

Replication means repeating an experiment in the same way to produce the same results. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. For example, how would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

To measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming others. The researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness in this situation.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent and dependent variables.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative population sample and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have higher reading scores than students who do not receive the intervention."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "There is no difference in anxiety levels between people who take St. John's wort supplements and those who do not."

- "There is no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

- "There is no difference in aggression levels between children who play first-person shooter games and those who do not."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "People who take St. John's wort supplements will have less anxiety than those who do not."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

- "Children who play first-person shooter games will show higher levels of aggression than children who do not."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when conducting an experiment is difficult or impossible. These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can examine how the variables are related. This research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Thompson WH, Skau S. On the scope of scientific hypotheses . R Soc Open Sci . 2023;10(8):230607. doi:10.1098/rsos.230607

Taran S, Adhikari NKJ, Fan E. Falsifiability in medicine: what clinicians can learn from Karl Popper [published correction appears in Intensive Care Med. 2021 Jun 17;:]. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06432-z

Eyler AA. Research Methods for Public Health . 1st ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2020. doi:10.1891/9780826182067.0004

Nosek BA, Errington TM. What is replication ? PLoS Biol . 2020;18(3):e3000691. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000691

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies . Perspect Clin Res . 2019;10(1):34-36. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

The Craft of Writing a Strong Hypothesis

Table of Contents

Writing a hypothesis is one of the essential elements of a scientific research paper. It needs to be to the point, clearly communicating what your research is trying to accomplish. A blurry, drawn-out, or complexly-structured hypothesis can confuse your readers. Or worse, the editor and peer reviewers.

A captivating hypothesis is not too intricate. This blog will take you through the process so that, by the end of it, you have a better idea of how to convey your research paper's intent in just one sentence.

What is a Hypothesis?

The first step in your scientific endeavor, a hypothesis, is a strong, concise statement that forms the basis of your research. It is not the same as a thesis statement , which is a brief summary of your research paper .

The sole purpose of a hypothesis is to predict your paper's findings, data, and conclusion. It comes from a place of curiosity and intuition . When you write a hypothesis, you're essentially making an educated guess based on scientific prejudices and evidence, which is further proven or disproven through the scientific method.

The reason for undertaking research is to observe a specific phenomenon. A hypothesis, therefore, lays out what the said phenomenon is. And it does so through two variables, an independent and dependent variable.

The independent variable is the cause behind the observation, while the dependent variable is the effect of the cause. A good example of this is “mixing red and blue forms purple.” In this hypothesis, mixing red and blue is the independent variable as you're combining the two colors at your own will. The formation of purple is the dependent variable as, in this case, it is conditional to the independent variable.

Different Types of Hypotheses

Types of hypotheses

Some would stand by the notion that there are only two types of hypotheses: a Null hypothesis and an Alternative hypothesis. While that may have some truth to it, it would be better to fully distinguish the most common forms as these terms come up so often, which might leave you out of context.

Apart from Null and Alternative, there are Complex, Simple, Directional, Non-Directional, Statistical, and Associative and casual hypotheses. They don't necessarily have to be exclusive, as one hypothesis can tick many boxes, but knowing the distinctions between them will make it easier for you to construct your own.

1. Null hypothesis

A null hypothesis proposes no relationship between two variables. Denoted by H 0 , it is a negative statement like “Attending physiotherapy sessions does not affect athletes' on-field performance.” Here, the author claims physiotherapy sessions have no effect on on-field performances. Even if there is, it's only a coincidence.

2. Alternative hypothesis

Considered to be the opposite of a null hypothesis, an alternative hypothesis is donated as H1 or Ha. It explicitly states that the dependent variable affects the independent variable. A good alternative hypothesis example is “Attending physiotherapy sessions improves athletes' on-field performance.” or “Water evaporates at 100 °C. ” The alternative hypothesis further branches into directional and non-directional.

- Directional hypothesis: A hypothesis that states the result would be either positive or negative is called directional hypothesis. It accompanies H1 with either the ‘<' or ‘>' sign.

- Non-directional hypothesis: A non-directional hypothesis only claims an effect on the dependent variable. It does not clarify whether the result would be positive or negative. The sign for a non-directional hypothesis is ‘≠.'

3. Simple hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement made to reflect the relation between exactly two variables. One independent and one dependent. Consider the example, “Smoking is a prominent cause of lung cancer." The dependent variable, lung cancer, is dependent on the independent variable, smoking.

4. Complex hypothesis

In contrast to a simple hypothesis, a complex hypothesis implies the relationship between multiple independent and dependent variables. For instance, “Individuals who eat more fruits tend to have higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.” The independent variable is eating more fruits, while the dependent variables are higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.

5. Associative and casual hypothesis

Associative and casual hypotheses don't exhibit how many variables there will be. They define the relationship between the variables. In an associative hypothesis, changing any one variable, dependent or independent, affects others. In a casual hypothesis, the independent variable directly affects the dependent.

6. Empirical hypothesis

Also referred to as the working hypothesis, an empirical hypothesis claims a theory's validation via experiments and observation. This way, the statement appears justifiable and different from a wild guess.

Say, the hypothesis is “Women who take iron tablets face a lesser risk of anemia than those who take vitamin B12.” This is an example of an empirical hypothesis where the researcher the statement after assessing a group of women who take iron tablets and charting the findings.

7. Statistical hypothesis

The point of a statistical hypothesis is to test an already existing hypothesis by studying a population sample. Hypothesis like “44% of the Indian population belong in the age group of 22-27.” leverage evidence to prove or disprove a particular statement.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

Writing a hypothesis is essential as it can make or break your research for you. That includes your chances of getting published in a journal. So when you're designing one, keep an eye out for these pointers:

- A research hypothesis has to be simple yet clear to look justifiable enough.

- It has to be testable — your research would be rendered pointless if too far-fetched into reality or limited by technology.

- It has to be precise about the results —what you are trying to do and achieve through it should come out in your hypothesis.

- A research hypothesis should be self-explanatory, leaving no doubt in the reader's mind.

- If you are developing a relational hypothesis, you need to include the variables and establish an appropriate relationship among them.

- A hypothesis must keep and reflect the scope for further investigations and experiments.

Separating a Hypothesis from a Prediction

Outside of academia, hypothesis and prediction are often used interchangeably. In research writing, this is not only confusing but also incorrect. And although a hypothesis and prediction are guesses at their core, there are many differences between them.

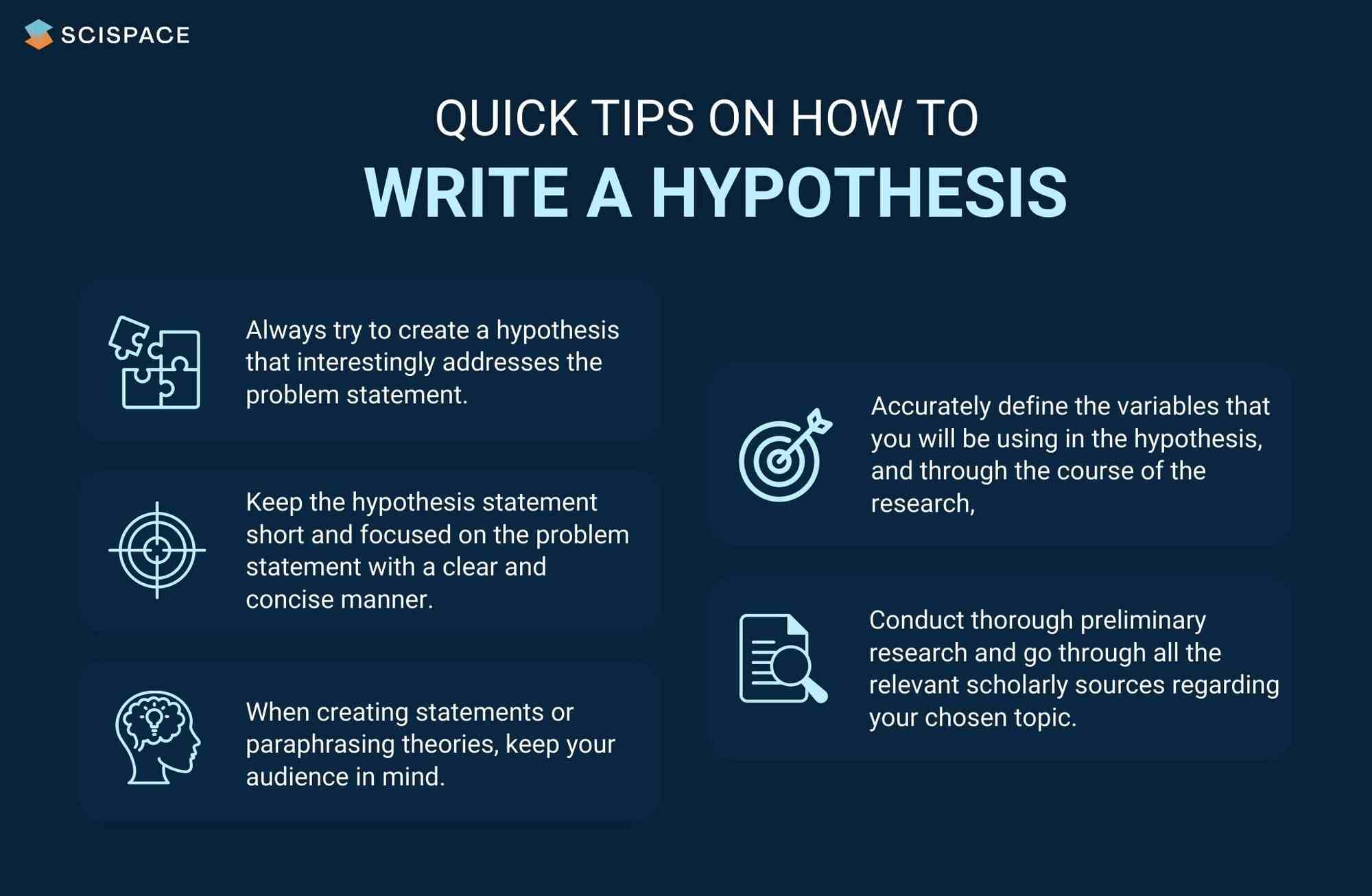

A hypothesis is an educated guess or even a testable prediction validated through research. It aims to analyze the gathered evidence and facts to define a relationship between variables and put forth a logical explanation behind the nature of events.