- Undergraduate Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- Teacher Certification Options

- International Admissions Information

- Financial Aid and Scholarships

- Undergraduate Majors and Minors

- Master’s Programs

- Certificates of Advanced Study

- Doctoral Programs

- Online, Hybrid, and Flexible Programs

- Career Services and Certification

- For Families and Supporters

- Learning Communities

- Student Organizations

- Undergraduate Peer Advisors

- Bridge to the City

- Engaged BIPOC Scholar-Practitioner Program

- Field Placements & Internships

- Orange Holmes Scholars

- Spector/Warren Fellowship

- Study Abroad

- Research News

- Faculty Bookshelf

- Faculty Publications

- Grants & Awards

- Doctoral Dissertations

- Research Resources and Support

- Office of Professional Research and Development

- Atrocity Studies Annual Lecture

- Antiracist Algebra Coalition

- Ganders Lecture Series

- InquiryU@Solvay

- Intergroup Dialogue Program

- Otto’s Fall Reading Kickoff

- Psycho-Educational Teaching Laboratory

- The Study Council

- Writing Our Lives

- Center for Academic Achievement and Student Development

- Center on Disability and Inclusion

- Center for Experiential Pedagogy and Practice

- Latest News

- Upcoming Events

- Education Exchange

- Get Involved

- Advisory Board

- Tolley Medal

- Administration

- From the Dean

- Convocation

- Accreditation

- Request Info

- Grants & Awards

Suicide Risk: Case Studies and Vignettes

Identifying warning signs case study.

Taken from Patterson, C. W. (1981). Suicide. In Basic Psychopathology: A Programmed Text.

Instructions: Underline all words and phrases in the following case history that are related to INCREASED suicidal risk. Then answer the questions at the end of the exercise.

History of Present Illness

The client is a 65-year-old white male, divorced, living alone, admitted to the hospital in a near comatose condition yesterday because of an overdose of approximately thirty tablets of Valium, 5 mgm, combined with alcoholic intoxication. The client was given supportive care and is alert at the present time.

A heavy drinker, he has been unemployed from his janitorial job for the past three months because of his drinking. He acknowledges feeling increasingly depressed since being fired, and for the past two weeks has had insomnia, anorexia, and a ten pound weight loss. He indicates he wanted to die, had been thinking of suicide for the past week, planned the overdose, but had to “get drunk” because “I didn’t have the guts” [to kill myself]. He is unhappy that the attempt failed, states that, “nobody can help me” and he sees no way to help himself. He denies having any close relationships or caring how others would feel if he committed suicide (“who is there who cares?”). He views death as a “relief.” His use of alcohol has increased considerably in the past month. He denies having any hobbies or activities, “just drinking.”

Past Psychiatric History

Hospitalized in 1985 at Pleasantview Psychiatric Hospital for three months following a suicide attempt after his fourth wife left him. Treated with ECT, he did “pretty good, but only for about two years” thereafter.

Social History

An only child, his parents are deceased (father died by suicide when client was eight years old; mother died of “old age” two years ago). Raised in Boston, he moved to Los Angeles at twenty-one and has lived here since. Completed eighth grade (without any repeat) but quit to go to work (family needed money). Has never held a job longer than two years, usually quitting or being fired because of “my temper.” Usually worked as a laborer. Denies any physical problems other than feeling “tired all the time.” Currently living on Social Security income, he has no other financial resources. He received a bad conduct discharge from the army after three months for “disobeying an order and punching the officer.” He has had no legal problems other than several arrests in the past two years for public intoxication. Married and divorced four times, he has no children or close friends.

Mental Status Examination

65 y.o. W/M, short, thin, grey-haired, unkempt, with 2-3 day-old beard, lying passively in bed and avoiding eye contact. His speech was slow and he did not spontaneously offer information. Passively cooperative. Little movement of his extremities. His facial expression was sad and immobile.

Thought processes were logical and coherent, and no delusions or hallucinations were noted. Theme of talk centered around how hopeless the future was and his wishes to be dead. There were no thoughts about wishing to harm others.

Mood was one of depression. He was oriented to person, place, and time, and recent and remote memory was intact. He could perform simple calculations and his general fund of knowledge was fair. His intelligence was judged average.

Diagnostic Impression

- drug overdose (Valium and alcohol)

- Dysthymic Disorder (depression)

- Substance Use Disorder (alcohol)

Questions for Exercise

You have interviewed the client, obtained the above history, and now have to make some decisions about the client. He wants to leave the hospital.

- Is he a significant risk for suicide?

- discharging him as he wishes and with your concurrence?

- discharging him against medical advice (A.M.A.)?

- discharging him if he promises to see a therapist at a nearby mental health center within the next few days?

- holding him for purposes of getting his psychiatric in-client care even though he objects?

- Discuss briefly why you would not have chosen the other alternatives in question #2.

Identifying Warning Signs Case Study: Feedback/Answers

The client is a 65-year-old white male , divorced , living alone , admitted to the hospital in a near comatose condition yesterday because of an overdose of approximately thirty tablets of Valium, 5 mgm, combined with alcoholic intoxication. The client was given supportive care and is alert at the present time. A heavy drinker , he has been unemployed from his janitorial job for the past three months because of his drinking. He acknowledges feeling increasingly depressed since being fired, and for the past two weeks has had insomnia and a ten pound weight loss . He indicates he wanted to die, had been thinking of suicide for the past week, planned the overdose, but had to “get drunk” because “I didn’t have the guts” [to kill myself]. He is unhappy that the attempt failed , states that, “ nobody can help me ” and he sees no way to help himself. He denies having any close relationships or caring how others would feel if he committed suicide (“who is there who cares?”). He views death as a “relief.” His use of alcohol has increased considerably in the past month. He denies having any hobbies or activities , “just drinking.”

Hospitalized in 1985 at Pleasantview Psychiatric Hospital for three months following a suicide attempt after his fourth wife left him . Treated with ECT, he did “pretty good, but only for about two years” thereafter.

An only child, his parents are deceased ( father died by suicide when client was eight years old; mother died of “old age” two years ago). Raised in Boston, he moved to Los Angeles at twenty-one and has lived here since. Completed eighth grade (without any repeat) but quit to go to work (family needed money). Has never held a job longer than two years , usually quitting or being fired because of “ my temper .” Usually worked as a laborer. Denies any physical problems other than feeling “tired all the time.” Currently living on Social Security income, he has no other financial resources . He received a bad conduct discharge from the army after three months for “disobeying an order and punching the officer.” He has had no legal problems other than several arrests in the past two years for public intoxication. Married and divorced four times , he has no children or close friends .

65 y.o. W/M, short, thin, grey-haired, unkempt, with 2-3 day-old beard, lying passively in bed and avoiding eye contact. His speech was slow and he did not spontaneously offer information . Passively cooperative. Little movement of his extremities. His facial expression was sad and immobile. Thought processes were logical and coherent, and no delusions or hallucinations were noted. Theme of talk centered around how hopeless the future was and his wishes to be dead . There were no thoughts about wishing to harm others. Mood was one of depression . He was oriented to person, place, and time, and recent and remote memory was intact. He could perform simple calculations and his general fund of knowledge was fair. His intelligence was judged average.

- Is he a significant risk for suicide? Yes. The client presents a considerable suicidal risk, with respect to demographic characteristics, psychiatric diagnosis and mental status findings.

- Discuss briefly why you would not have chosen the other alternatives in question #2. The client appears to be actively suicidal at the present time,and may act upon his feelings. Nothing about his life has changed because of his attempt. He still is lonely, with limited social resources. He feels no remorse for his suicidal behavior and his future remains unaltered. He must be hospitalized until some therapeutic progress can be made.

Short-Term Suicide Risk Vignettes

*Case study vignettes taken from Maris, R. W., Berman, A. L., Maltsberger, J. T., & Yufit, R. I. (Eds), (1992). Assessment and prediction of suicide. New York: Guilford. And originally cited in Stelmachers, Z. T., & Sherman, R. E. (1990). Use of case vignettes in suicide risk assessment. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 20, 65-84.

The assessment of suicide risk is a complicated process. The following vignettes are provided to promote discussion of suicide risk factors, assessment procedures, and intervention strategies. The “answers” are not provided, rather students are encouraged to discuss cases with each other and faculty. Two examples of how discussions may be facilitated are provided.

37-year-old white female, self-referred. Stated plan is to drive her car off a bridge. Precipitant seems to be verbal abuse by her boss; after talking to her nightly for hours, he suddenly refused to talk to her. As a result, patient feels angry and hurt, threatened to kill herself. She is also angry at her mother, who will not let patient smoke or bring men to their home. Current alcohol level is .15; patient is confused, repetitive, and ataxic. History reveals a previous suicide attempt (overdose) 7 years ago, which resulted in hospitalization. After spending the night at CIC and sobering, patient denies further suicidal intent.

16-year-old Native American female, self-referred following an overdose of 12 aspirins. Precipitant: could not tolerate rumors at school that she and another girl are sharing the same boyfriend. Denies being suicidal at this time (“I won’t do it again; I learned my lesson”). Reports that she has always had difficulty expressing her feelings. In the interview, is quiet, guarded, and initially quite reluctant to talk. Diagnostic impression: adjustment disorder.

49-year-old white female brought by police on a transportation hold following threats to overdose on aspirin (initially telephoned CIC and was willing to give her address). Patient feels trapped and abused, can’t cope at home with her schizophrenic sister. Wants to be in the hospital and continues to feel like killing herself. Husband indicates that the patient has been threatening to shoot him and her daughter but probably has no gun. Recent arrest for disorderly conduct (threatened police with a butcher knife). History of aspirin overdose 3 years ago. In the interview, patient is cooperative; appears depressed, anxious, helpless, and hopeless. Appetite and sleep are down, and so is her self-esteem. Is described as “anhedonic.” Alcohol level: .12.

23-year-od white male, self-referred. Patient bought a gun 2 months ago to kill himself and claims to have the gun and four shells in his car (police found the gun but no shells). Patient reports having planned time and place for suicide several times in the past. States that he cannot live any more with his “emotional pain” since his wife left him3 years ago. This pain has increased during the last week, but the patient cannot pinpoint any precipitant. Patient has a history of chemical dependency, but has been sober for 20 months and currently goes to AA.

22-year-old black male referred to CIC from the Emergency Room on a transportation hold. He referred himself to the Emergency Room after making fairly deep cuts on his wrists requiring nine stitches. Current stress is recent breakup with his girlfriend and loss of job. Has developed depressive symptoms for the last 2 months, including social withdrawal, insomnia, anhedonia, and decreased appetite. Blames his sister for the breakup with girlfriend. Makes threats to sister (“I will slice up that bitch, she is dead when I get out”). Patient is an alcoholic who just completed court-ordered chemical dependency treatment lasting 3 weeks. He is also on parole for attempted rape. There is a history of previous suicide attempts and assaultive behavior, which led to the patient being jailed. In the interview, patient is vague regarding recent events and history. He denies intent to kill himself but admits to still being quite ambivalent about it. Diagnostic impression: antisocial personality.

19-year-old white male found by roommate in a “sluggish” state following the ingestion of 10 sleeping pills (Sominex) and one bottle of whiskey. Recently has been giving away his possessions and has written a suicide note. After being brought to the Emergency Room, declares that he will do it again. Blood alcohol level: .23. For the last 3 or 4 weeks there has been sleep and appetite disturbance, with a 15-pound weight loss and subjective feelings of depression. Diagnostic impression: adjustment disorder with depressed mood versus major depressive episode. Patient refused hospitalization.

30-year-old white male brought from his place of employment by a personnel representative. Patient has been thinking of suicide “all the time” because he “can’t cope.” Has a knot in his stomach; sleep and appetite are down (sleeps only 3 hours per night); and plans either to shoot himself, jump off a bridge, or drive recklessly. Precipitant: constant fighting with his wife leading to a recent breakup (there is a long history of mutual verbal/physical abuse). There is a history of a serious suicide attempt: patient jumped off a ledge and fractured both legs; the precipitant for that attempt was a previous divorce. There is a history of chemical dependency with two courses of treatment. There is no current problem with alcohol or drugs. Patient is tearful, shaking, frightened, feeling hopeless, and at high risk for impulsive acting out. He states that life isn’t worthwhile.

Vignette Discussion Examples

Vignette example 1.

Twenty-six year old white female phoned her counselor, stated that she might take pills, and then hung up and kept the phone off the hook. The counselor called the police and the patient was brought to the crisis intervention center on a transportation hold. Patient was angry, denied suicidal attempt, and refused evaluation; described as selectively mute, which means she wouldn’t answer any of the questions she didn’t like.

Facilitator: How high a risk is this person for committing suicide? Low, moderate or high? Student Answer 1: Maybe moderate because the person is warning somebody, basically a plea for help. Facilitator: Okay, so we have suicidal talk. That’s one of our red flags. What else? She said she might take pills, so we didn’t know if she does have the pills. So she has a plan. The plan would be to take pills, but we don’t know if we have means. Student Answer 2: High. She’s also angry. I don’t know if she’s angry often. Facilitator: A person in this situation who is really thinking about killing themselves tends not to deny it. They tend not to deny it. There are exceptions to everything, but most of the time, for some reason, this is one of the things where people tend to mostly tell you the truth. If you ask people, they tend to tell you the truth. It’s a very funny thing about suicide that way. That’s certainly not true about most things. If you ask people how much they drink…But, “Are you thinking about killing yourself?” “Well, yes.” If you ask a question, you tend to get a more or less accurate, straight answer. Student question: Is that because it doesn’t matter anymore? If they’re going to die anyway, who’s going to care about what anybody thinks or what happens? Facilitator: My hypothesis would be, when someone is at that point, they’re talking about real, true things. They’re not into play. This is where they are. If they’re really looking at it, then they’re just at that place. What’s to hide at that point? You don’t have anything to lose. It’s a state of mind. And then if you’re not in that place—it’s like, how close are you to the edge of that cliff? “I’m not there. I know where that is, and I’m not there.” “If you get there, will you tell me?” “Yeah, I’m not there.” So, people have a sense—if they’ve gotten that close, they know where that line is, and they know about where they stand in regard to it, because it’s a very hard-edged, true thing.

Twenty-three year old white male, self-referred. Patient bought a gun two months ago to kill himself and claims to have the gun and four shells in his car. Police found the gun but no shells. Patient reports having planned time and place for suicide several times in the past. States that he cannot live anymore with his emotional pain since his wife left him three years ago. This pain has increased during the last week, but the patient cannot pinpoint any precipitant. Patient has a history of chemical dependency but has been sober for 20 months and currently goes to AA.

Facilitator: How high a risk is this person for committing suicide? Low, moderate or high? On a scale from 0 to 7 (7 being very high). Student Answer 1: High. On a scale of 0 to 7? Student Answer: Six. Student Answer 2: I would say three. I think it would be lower because if he’s already bought the gun two months ago and he’s self-referring himself to get help, he wants to live. He has not made peace with whatever, and he’s more likely not give away his things, and he’s going to AA meetings. I think it’s lower than really an extreme…I would say a three or four. Student Answer 3: I would say a four or five, moderate. Student Answer 4: About a five..several times and hasn’t followed through, tells me he doesn’t really want to follow through with it. Facilitator: And there are no shells, right? So we can see some of the red flags are there, but some of them aren’t. He’s still sober… Student: He has a support group. Student: He’s not using, though he bought a gun—so that’s a concern. There is a lot there. Student: He may not have the shells so he doesn’t have the opportunity to. So does that make him more…? Student 2: Think I’ll change mine to a five. Facilitator: So the mean was 4.68, so 5 was the mode. If we’re saying this is a moderate risk, what things would we look for that would make this a high risk? Student: Take away AA. Student: If he falls off the wagon, he goes right to the top. Student: And if he finds the shells. Facilitator: Because it probably is not that hard to find shells. All these stores around here, you can get shells quicker than you can get a gun, so he’s only a five-minute purchase away from having lethal—in contrast to not having the gun. Student: Could there be a difference in the time? Let’s say his wife left him just four to six months ago rather than three years. Would that be something that would be more serious? Facilitator: Yes, or if his wife just left him. So, say his wife left him a month ago that would bump it up. So that’s unresolved. That’s taking a person that was worried and that’s pushing him higher. Student: It also raises the homicide rate. Facilitator: Yes, because these tend to be murder-suicides. How often have we seen that? Murder-suicide is a big deal. If she won’t be with me, she won’t be with anybody.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med

- v.3(1); 2019 Feb

A Single-session Crisis Intervention Therapy Model for Emergency Psychiatry

Associated data.

Presentations for anxiety and depression constitute the fastest growing category of mental health diagnoses seen in emergency departments (EDs). Even non-psychiatric clinicians must be prepared to provide psychotherapeutic interventions for these patients, just as they might provide motivational interviewing for a patient with substance use disorders. This case report of an 18-year-old woman with suicidal ideation illustrates the practicality and utility of a brief, single-session, crisis intervention model that facilitated discharge from the ED. This report will help practitioners to apply this model in their own practice and identify patients who may require psychiatric hospitalization.

INTRODUCTION

Symptoms of anxiety and depression are the most common reasons to present for emergency psychiatric care. 1 The broad differential for depressive and anxiety symptoms includes major depressive, post-traumatic stress, adjustment, substance-induced, and personality disorders. 2 Because medications are not indicated for some of these conditions, all emergency department (ED) clinicians must be prepared to provide brief, non-pharmacologic treatment. This case report demonstrates a single-session, crisis intervention model for ED patients presenting with anxiety and depression.

CASE REPORT

An 18-year-old woman was brought to the ED by ambulance. Paramedics reported that the patient was on the phone with her mother and said she wanted to be dead. Her mother lives in another country and called emergency services. The patient was tearful and “very stressed” on arrival. Vital signs, a routine urine toxicology screen, and pregnancy test were unremarkable. She reported suicidal thoughts for about a week attributed to poor grades in college, family conflict, and financial obligations. She had missed several appointments with her therapist and prescriber and had recently run out of sertraline (Zoloft). She declined to provide her mother’s phone number.

The patient described a history of abuse at a young age. She had one prior psychiatric hospitalization after walking into traffic in a suicide attempt at age 15. Other episodes of self-harm started at age 10 and were non-suicidal in nature. Her biological father had minimal contact with the patient. Her grandmother had been diagnosed with schizophrenia. The patient denied access to firearms.

Concerned about multiple suicide safety risk factors, the emergency psychiatrist began a structured, single-session psychotherapy. The psychiatrist and patient wrote a timeline of events preceding the presentation ( Figure 1 ). In so doing, she provided more details of her history. Ten months prior, she had to leave her apartment due to conflicts with roommates. Beginning college, she worried about tuition and found two jobs. Despite several attempts to re-schedule her therapy appointments around her work schedule, the therapist’s office did not return her calls. The patient also revealed that a supportive stepfather lived nearby. The morning of her ED visit, she received another reminder about her tuition bill. She was talking with a roommate about this bill; however, she felt her roommate did not fully appreciate her challenges, and she then called her mother.

A timeline of stressors preceding the patient’s emergency department visit.

The psychiatrist and patient agreed all this would be stressful for anyone. Her affect evolved from tearful to more composed, and she identified some immediate goals: find a new therapist; talk with her school about a tuition grant; identify a tutor; and spend more time doing things she enjoys ( Supplemental Figure ). She agreed to let the resident call her mother who could help complete these tasks. The patient’s mother corroborated the patient’s history. In fact, the mother had already spoken with the school about help with tuition and had begun searching for new outpatient providers.

To complete discharge planning, a nurse made an appointment for the patient with a new outpatient provider. The patient completed a written safety plan and was offered a follow-up call. The family was apprised of local crisis resources. Within an hour, the evaluating psychiatrist felt that this patient’s acute risk was significantly mitigated through safety planning, mobilization of social supports, connection to treatment, and acute de-escalation to justify discharge. After six months, she had persistent resolution of suicidal thoughts without recurrent self-harm or inpatient hospitalization.

This brief psychotherapy emphasizes active problem-solving and is adapted from a multi-session model built for integrated care settings. 3 Specialized single-session psychotherapies have been described for other psychiatric conditions including insomnia, 4 gambling, 5 agitation, 6 and suicidal ideation. 7 Therapy models described for ED settings are often applied by non-psychiatric staff, for example, motivational interviewing for substance use 8 and safety planning for suicidality. 9 , 10

This model uses the concept of crisis as a framework for assessment and treatment. A crisis occurs when a person’s usual coping skills are inadequate to a life stressor. 11 A crisis may be precipitated by medical illness or interpersonal conflicts. A patient’s ability to cope with stressors arises from individual temperament, life experiences, personal skills, and social network. When a crisis develops, individuals are unable to access these strengths to resolve the crisis. Anxiety, depression, a sense of feeling overwhelmed, or suicidal ideation ensues in a patient with perhaps little psychiatric treatment history and a high level of functioning that includes stable employment and relationships. Some patients manifest primitive coping skills such as somatization that precipitate an ED visit. A crisis may also relate to worsening symptoms in patients with chronic psychiatric illness, for example, increased suicidal ideation in a patient with borderline personality disorder. Crisis does not fit neatly into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , 5 th edition, (DSM-5) but is most closely related to the diagnosis of adjustment disorder. 12

Single-session therapy leverages the crisis model to help patients and providers understand the origins of the ED visit and begin actively resolving the crisis. This intervention may be delivered by emergency physicians or ED behavioral health consultants including social workers or nurses. Patients most likely to benefit from this therapy present in the context of a discrete life stressor and have a history of better psychological functioning and insight.

CPC-EM Capsule

What do we already know about this clinical entity?

Anxiety, depression, and adjustment reactions represent the fastest-growing category of reasons for psychiatric presentations to the emergency department (ED) .

What makes this presentation of disease reportable?

This case demonstrates how a single-session crisis therapy in the ED may avert hospitalization for a depressed, suicidal patient .

What is the major learning point?

ED clinicians should be prepared to recommend or deliver brief psychotherapy for these common psychiatric presentations .

How might this improve emergency medicine practice?

Most suicidal ED patients are hospitalized. However, most patients with depression or suicidality can be safely treated in the ED and discharged .

One-Session Crisis Intervention Psychotherapy

The goals of this intervention include ameliorating anxiety and depressive symptoms, initiating treatment, and identifying patients who may need referral for more intensive psychiatric treatment. These steps and their therapeutic benefits are summarized in Table .

Summary of working steps and therapeutic processes for one-session crisis intervention therapy.

| Stage | Working steps | Therapeutic process |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Recognize the crisis and identify the precipitant(s) | ) | |

| 2. Characterize the patient’s response | ||

| 3. Formulate together | ||

| 4. Identify behavioral goals and offer concrete support | ) | |

| 5. Engage social supports | ) |

DSM-5 , Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; ED , emergency department.

1. Recognize the Crisis and Identify the Precipitant

Patients in crisis present to the ED with a range of psychiatric symptoms including anxiety, depression, fatigue, or poor sleep. After excluding a somatic etiology of psychiatric symptoms and ensuring acute safety, the clinician must elucidate the onset of the patient’s psychiatric symptoms. In the ED it is important to keep in mind that suicidality is often a symptom of underlying distress, does not necessarily indicate the presence of a severe psychiatric disorder, and can be treated in outpatient settings. 13

Writing a timeline with the patient helps identify life stressors driving the crisis. This technique is helpful for several reasons. First, many patients in crisis feel overwhelmed and are challenged to recall and reconstruct a helpful history. A structured framework focuses the interview on the acute presentation. A timeline is easy for both clinicians and patients to interpret. And, in the act of writing a timeline together, the clinician and patient build therapeutic rapport that itself is part of the healing process. Finally, the resulting product can be used to later formulate the crisis state with the patient.

2. Characterize the Patient’s Response

The patient’s emotional and behavioral responses to the crisis state should be considered in guiding treatment. 14

Validate the patient’s emotional response to the crisis. The emotional response is often readily described by the patient: stressed, overwhelmed, anxious, or alone. The clinician may validate the emotional state by noting it to be an understandable response to the clear stressors described in the timeline. A patient’s endorsement of depression is not synonymous with major depressive disorder (a specific diagnosis with precise diagnostic criteria).

Behavioral responses are characterized by immobility, avoidance, or adaptation. Immobility is a sense of feeling stuck and persistently unable to problem-solve, as this patient felt initially. Some patients avoid their problems entirely, thereby prolonging the crisis and exacerbating its consequences. Immobile and avoidant patients need help identifying the precipitant of the crisis and brainstorming possible solutions. Immobile or avoidant patients who cannot demonstrate more adaptive skills may require referral to specialty psychiatric care.

Patients who demonstrate adaptive responses to crisis are positioned to grow from their crisis and manage their lives more effectively. In this case, the patient moved from a more immobile stance to one characterized by greater initiative and adaptation.

3. Formulate Together

With a timeline of precipitants and a sense of the patient’s response styles, the clinician formulates the acute crisis aloud with the patient. What are the precipitants? How do these make the patient feel? What does the patient need to address the crisis? What choices are available?

The resulting conversation is both diagnostic and therapeutic. This patient experienced relief from an expert’s explanation of why she did not feel well. The clinician validated the severity of the patient’s stressors while offering optimism and active problem-solving.

A broad psychiatric differential should always be considered. Cognitive impairment related to severe depression or disorganization due to psychosis may be recognized in the course of therapy. Such symptoms complicate less-restrictive outpatient treatment and may alter disposition planning. Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome was considered less likely here given the timing and quality of her depressive symptoms.

4. Identify Behavioral Goals and Offer Concrete Support

The clinician helps the patient generate a to-do list of goals to resolve the crisis. This patient’s list is included as Supplemental Figure . Goals should be specific, realistic, and accomplishable in the near future. 15 Patients with more aspirational goals (e.g., feel better) should identify intermediate steps that are specific and accomplishable. Solutions-focused thinking can be introduced by asking, “If things were going well in your life, how would things look four weeks from now?” This conversation invites the patient to anticipate potential obstacles to resolution of the crisis—and also begin envisioning discharge from the ED.

Clinicians need to provide practical support for patients. For example, this patient needed help making an international phone call. Making an appointment for an outpatient provider improves outpatient adherence and reduces ED return rates. 16 , 17 Identifying triggers for suicidal thoughts, coping skills, and supportive contacts through a safety plan reduces the risk of subsequent self-harm and improves symptom burden. 9 , 18 , 19

5. Engage Social Supports

Patients in crisis are quick to say they have nobody to help them when, in fact, supportive friends or family are indeed available. This social network should be mobilized while the patient is in the ED.

A hub-and-spoke diagram helps the patient recognize persons who can help resolve the crisis ( Figure 2 ). The patient is in the middle hub. As many other persons as possible are written around the spokes of the wheel. Supportive persons are connected to the hub with a solid line, and less-supportive contacts are connected with a dashed line. The most important one or two persons are starred.

A hub-and-spoke diagram of the patient’s social supports.

The clinician should contact these supportive persons. Collateral information provides a stronger diagnostic and suicide safety assessment. 20 In this instance, that the patient’s mother described so many supportive actions already underway illustrates how the crisis state induces a perception of isolation and hopelessness. Social supports should be enlisted to help in treatment planning. For example, family may take the patient to a follow-up appointment. When collateral information introduces new data worrying for safety risk or a social network is truly unavailable, the clinician may more strongly consider more intensive treatment including hospitalization.

Most ED visits for suicidal ideation still result in hospitalization. 21 This single-session, crisis intervention complements the traditional expectations of emergency psychiatric evaluations by providing clinicians a way to treat symptoms of anxiety and depression in the ED. This model may also assist in the treatment of boarding psychiatric patients and encourage further studies of psychotherapy in the emergency setting.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments.

The author would like to thank Dr. Robert Feinstein, MD, for his mentorship and intellectual contributions to this model. Also, Dr. Jack Gende, DO, deserves thanks for his superb care of this patient. Dr. Simpson presented an earlier iteration of this model at the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine Annual Meeting, November 9–12, 2016, in Austin, TX.

Section Editor: Shadi Lahham, MD

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_cpcem

Documented patient informed consent and/or Institutional Review Board approval has been obtained and filed for publication of this case report.

Conflicts of Interest : By the CPC-EM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Claire Malengret and Claire Dall'Osto

This chapter provides a foundation for understanding the nature of a crisis, how a person may be impacted by a crisis, and the models, processes, and strategies a crisis counsellor uses to assess and intervene when people in crisis seek help and support. With an emphasis on how crisis intervention differs from other counselling interventions, a case study is provided with the aim to help the reader reflect on and apply relevant crisis models of assessment and intervention learned in this chapter. Further differentiation is made between crisis stressors resulting in exposure to a traumatic event and ongoing traumatic stress responses requiring long-term counselling, psychiatric services, or specialised mental health intervention. Due to the nature of crisis work, there is a high prevalence of burnout and work-related stress in this field. As such, counsellors working in crisis work need to practice self-care, regular clinical supervision, and the continuing maintenance of the counsellor’s general health and wellbeing.

Learning Objectives

- Describe the nature of crisis.

- Identify the types of crisis.

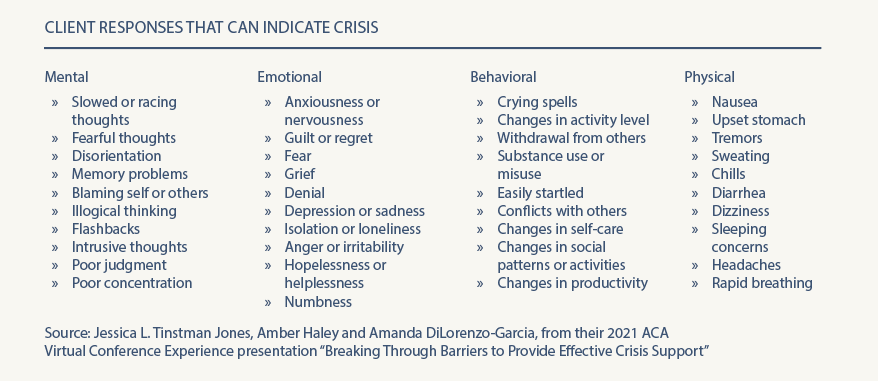

- Recognise and understand common emotional, physical, behavioural, and cognitive reactions of people in crisis.

- Analyse the major theories underpinning crisis counselling interventions.

- Examine the importance and role of the therapeutic relationship within crisis counselling.

- Apprehend the ethical implications and professional issues of crisis intervention.

- Identify trauma definitions, assessment, and treatment approaches.

- Identify and reflect on your own personal history and experiences of crisis, including responses.

- Recognise and understand the impact of crisis counselling work on the counsellor and the need to implement self-care practices and stress management strategies.

Introduction

We live in a world where millions of people are confronted with crisis-provoking events each year that they cannot cope with or resolve on their own and, therefore, will often seek help from counsellors. Examples of crisis-inducing events include natural disasters such as bushfires, sexual assaults, terrorist attacks, the death of a loved one, a suicide attempt, domestic violence, relationship breakdown, retirement, promotion, and demotion, change in school status, pregnancy, divorce, physical illness, unemployment, and more recently, a world pandemic. These situations can be a turning point in a person’s life—either one of growth, strength, and opportunity or health decline, dysfunction, and emotional illness (Roberts & Dziegielewski, 1995; Roberts, 2005; Hoff et al., 2009). When people experience a crisis, it is the support they receive during and immediately after the crisis that often plays a crucial part in determining the impact of the crisis on their lives (France, 2014). Therefore, it is imperative crisis counsellors have the understanding, skills, and knowledge to offer a short-term intervention that assists people in crisis to cope, stabilise and receive the support and resources they need.

What is a crisis?

When a person experiences a crisis, they experience severe disruption of their psychological equilibrium and are unable to use their usual ways of coping. This then results in a state of disequilibrium and impaired functioning (Lewis & Roberts, 2001; Roberts, 2005). Because the person is unable to draw on their everyday problem-solving methods during a crisis, and there is a sense of diminished control over the events and limited options, they may experience confusion or bewilderment (Hendricks, 1985; Pollio, 1995).

Crisis states are temporary, lasting from hours through to an estimated six weeks, as the body cannot sustain being ‘off balance’ or in a state of disequilibrium, indefinitely. Resolving a crisis effectively may take some months, and this may involve learning new skills, reappraising the situation differently, or adapting to the new situation. Because people may resolve the crisis in a maladaptive or adaptive manner, some may be impacted by various mental health conditions such as depression, substance abuse, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Roberts, 2005).

There are four types of crises that a person may experience and include:

- developmental crisis or crisis in the life cycle (adjustments to transitions such as ageing, parenting)

- situational crisis (sexual assault, natural disaster, car accident)

- existential crisis (inner turmoil or conflicts in relation to the way a person lives their life, and views of their meaning and purpose)

- systemic crisis (the impact of colonisation on our First nations’ people or the 2009 Victorian ‘Black Saturday’ bushfires) (James & Myer, 2008).

Crisis is in the eye of the beholder

It is important to note the difficult task of defining a crisis. This is due to the subjectivity of the concept. Although the main reason for a crisis is usually preceded by a traumatic or hazardous event, it is imperative to realise that the individual’s perception of the event and their inability to cope with the event are two other conditions to consider. Focusing only on the event itself also suggests that one can categorise a crisis but that all people may respond in the same manner to a particular event. Thus, it is not the actual event that activates a crisis state, but how a person interprets or perceives these events, how they cope, and the degree to which they have access to social resources, that determine how they respond. In other words, crisis is in the eye of the beholder (Hoff et al., 2009; Hoffer & Martin, 2020).

This perception is influenced by several factors in a person’s life, such as personal characteristics, biological, gender, culture, attachment style, previous life experiences, social context, personal values, level of resilience, influences, availability of social support, previous trauma, and history of major mental illness (Loughran, 2011; Roberts & Ottens, 2005). It is also important to understand that people who are reacting to a crisis are not necessarily showing pathological responses but normal crisis responses to an abnormal event (Bateman, 2010; Hobfoll et al., 2007; James, 2008).

Principles and characteristics of crisis

The following principles and characteristics help to create an understanding of the nature of a crisis, and emphasise not only the important work of a crisis counsellor but the values and philosophical assumptions that need to guide their practice:

- crisis embodies both danger and opportunity for the person experiencing the crisis

- crisis contains the seeds of growth and impetus for change

- crisis is usually time limited but may develop into a prolonged crisis if the person experiences a series of stressful situations after the crisis

- crisis is often complex and difficult to resolve

- a crisis counsellor’s experiences of crisis in their personal life may greatly enhance their effectiveness in crisis intervention

- quick fixes may not be applicable to many crisis situations

- crisis confronts people with choices

- emotional disequilibrium or disorganization accompany crisis

- the resolution of crisis and the personhood of crisis workers interrelate (James, 2008, p. 19).

Learning activity 1

- How do you think your previous life experiences of crisis may increase your effectiveness as a crisis counsellor?

- What personal qualities do you possess that may enhance an intervention that you use with a person who has experienced a crisis?

- What are the risks of having unresolved crisis experiences as a counsellor, and how might this impact your effectiveness in crisis work?

Common reactions to a crisis

Listed here are some of the common reactions a person might experience, which are normal responses given the abnormality of the event they have experienced.

| Emotional

| Physical |

| Behavioural | Cognitive

|

Table content sourced from Massazza et al ., (2021) used under a CC BY licence and Wahlström et al ., (2013) used under a CC BY-NC licence.

Learning activity 2

Imagine your life on a timeline from when you were born up until today. On this timeline, plot the most important or critical events (positive or negative) in your life that were turning points or changed you in some way.

- Looking at the critical events on your timeline, which events would you see as a crisis?

- How did those events change you?

What is crisis counselling?

Crisis counselling is an immediate response to people experiencing overwhelming events and may prevent the potential negative impact of psychological trauma. It focuses on the here and now, dealing with the immediate presenting needs at the point of crisis, and providing emergency psychological care to assist in helping the person return to an adaptive level of functioning (Flannery & Everly, 2000; Hobfoll et al., 2007).

The key goals that underpin crisis counselling frameworks and models are:

- meeting the person who is experiencing a crisis where they are at

- assessing and monitoring the person’s level of risk

- assisting them in mobilising of resources

- stabilising (by reducing distress

- improved or restored adaptive functioning (where possible) (Roberts & Ottens, 2005).

The difference between crisis counselling and other counselling interventions

Crisis counselling is different to the provision of ongoing therapeutic support. Because crisis counselling offers short-term strategies to prevent damage during and immediately after the person has experienced a crisis or devastating event, it requires that the counsellor be more active and directive than usual (James, 2008). Ongoing counselling may follow on from crisis to ensure the long-term improvement of a person’s mental health and wellbeing, but this is not the goal of crisis counselling. Instead, the goal is to provide a responsive and timely intervention to return a person to previous levels of functioning through the implementation of mobilising necessary resources, including the facilitation of links to these resources (Flannery & Everly, 2000). Given crisis counselling is the implementation of a short-term measure of support, it is often referred to as brief intervention or brief therapy. The timeframe for crisis counselling is between six to ten weeks and is guided by specific relevant models, guiding principles, and actions (Hendricks, 1985).

Case study: A bushfire crisis

You are part of a mobile service team who travels to a fire-affected area to provide support to individuals, families and emergency services workers affected by the recent bushfires. You arrive at a regional town that has just been devastated by catastrophic bushfires. A recovery centre has been set up at the local town hall and 700 individuals and families are presently seeking support at this recovery centre. You are assigned to Brett (35), a cattle farmer whose property, livestock, and beloved dog were lost in the fires. Brett is a third-generation cattle farmer on his family property. Within the first few minutes of meeting him, you observe that recalling these events for him results in constant tearfulness, and a questioning of what he could have done to be more prepared to have a different outcome. Brett explains that he has not slept in several days, and if he does sleep, he has nightmares. He also expresses to you that he does not know what the future holds for him now. Brett explains that he cannot focus for very long because he finds it difficult to believe this has happened to him. You observe that Brett appears to be numb and detached and unable to articulate his narrative in a linear and clear manner. Brett explains that he feels concerned for his ten employees who are no longer able to support their families. He also mentions that recently he went through a divorce which he felt devastated by at the time.

Learning activity 3

- From Brett’s reactions, what suggests that he is experiencing a crisis?

- What is the contributing factor that disrupts Brett’s equilibrium most? Is it the nature of the crisis event itself or the way Brett responds?

- Are there any risk factors to consider in Brett’s case?

Traumatic stress, crisis, and trauma

The term crisis is not interchangeable with traumatic stress and trauma. Dulmus and Hilarski (2003) explain a person is in a crisis state when they have experienced a situation or event and they have been unable to cope with it by utilising their usual coping mechanisms to lessen the impact of the event. This results in the person entering a state of disequilibrium (Roberts & Ottens, 2005).

Traumatic stress is when a crisis or event, such as child abuse, rape, combat trauma, and catastrophic natural disasters, overwhelms normal coping skills and is perceived as life-threatening (Behrman & Reid, 2002). Trauma can be defined as ‘… an experience of extreme stress or shock that is/or was, at some point, part of life’ (Gomes, 2014).

It is adaptive and normal for a person who has been exposed to a traumatic event to exhibit some anxiety in the early stages as this enables them to maintain vigilance as a way to increase safety. Others may feel numb after being exposed to a traumatic event. This is also an adaptive and normal response as much-needed insulation is provided to a person’s psychological system after the traumatic event (McNally et al., 2003). Those who do experience a traumatic injury can suffer from long-lasting consequences that impact them physically, cognitively, emotionally, and financially (Herrera-Escobar et al., 2021).

It is common for acute stress symptoms to be experienced after a traumatic event. When a person is exposed to a threat, neurotransmitters and hormones inform a physical response. The sympathetic nervous system is activated through a series of interconnected neurons that initiate a fight or flight response. The body releases glucose and adrenalin, increases heart rate and respiration, and remains in a state of high alert to manage any additional threat. At this point in time, the person is trying to make sense of their experience and is often feeling afraid and vulnerable as they attempt to rationalise what just occurred. Anxiety, loss of appetite, irritability, sleep difficulties, concentration difficulties, and hypervigilance can occur whilst in this physiological state. Warchal and Graham (2011) further explain that a person can have recurrent and involuntary memories of the traumatic event. A heightened state of arousal makes it difficult for them to respond normally, make decisions, and complete paperwork to link them to resources. Walsh (2007) explains that most people adapt and cope and therefore do not suffer long-term disturbance.

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Ongoing therapeutic support is required if a person continues to experience feelings of helplessness, intense fear or horror, re-living the traumatic event, hypervigilance, or emotional numbness. Norris et al. (2002) identified ongoing support to include long-term counselling or psychiatric services, or specialised mental health intervention. People generally possess enough resilience to circumvent the development of trauma symptoms that inform a formal trauma diagnosis, such as post-traumatic stress disorder. The DSM5-TR classifies PTSD as an anxiety disorder that can develop after exposure to a traumatic event (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2022). Rosenman (2002) reported that 57% of the Australian population reported a lifetime experience of a specified trauma. There are four different categories PTSD can be clustered into: (1) recurrent re-experiences of the traumatic event in the form of intrusive thoughts, nightmares, or flashbacks; (2) numbing and avoidance of trauma-related stimuli; (3) hyperarousal and reactivity; and (4) alterations in cognitions and mood (APA, 2022).

The origins and development of crisis counselling interventions

The research and development of crisis intervention originates in the 1940’s when the reactions of people whose loved ones had died in a fire at a nightclub in Boston in 1943 were recorded and studied by psychiatrist Erich Lindemann and his colleagues (Lindemann, 1944). Another psychiatrist, Gerald Caplan, expanded on this work and developed a four-stage model of crisis reactions (or phases of reactions that a person in a crisis may experience) which have formed the foundation for later contributions from theorists in crisis counselling. Caplan (1961, 1964) describes these phases as follows:

Phase 1 : increase in tension and distress from the crisis-inducing event

Phase 2 : there is an escalation in the disruption of the person’s life as they are stuck and cannot resolve the crisis quickly

Phase 3 : the person cannot resolve the crisis through their usual problem-solving methods

Phase 4 : the person resolves the crisis by mental collapse or deterioration, or they partially resolve it by adopting new ways of coping.

Erikson’s (1963) stage model of developmental crises and Roberts’ (1995) seven-stage crisis intervention model have led to the development of numerous crisis intervention models, particularly in the last two decades. Erikson’s focus was on World War II veterans’ disconnect from their culture together with the confusion associated with the traumatic war experiences rather than focusing on men suffering from repressed conflicts. Erikson assessed that veterans were experiencing confusion of identity about what they were and who they were in direct opposition to the lens of repressed conflict being used during this time period.

Characteristics of the crisis counsellor

The crisis counsellor’s ability to remain calm and simultaneously avoid subjective involvement in the crisis is crucial. This means that crisis counselling may not be suitable for every counsellor (Shapiro & Koocher, 1996). A crisis counsellor should communicate in a manner that is patient, sensitive, self-aware, and compassionate. Other characteristics and behaviours include warmth, understanding and acceptance, being available but not intrusive or controlling, trustworthy, empathic, caring, displaying effective listening skills, encouraging the person seeking appropriate referrals and support, and being able to maintain confidentiality (Bateman, 2010; Rainer & Brown, 2011; Westefeld & Heckman-Stone, 2003).

The crisis counsellor aims to establish a therapeutic relationship as they do in general counselling, however in crisis counselling, they do so in a shorter time-frame period. Other crisis intervention skills include encouragement, basic attending and listening skills, reflection of emotions, and instilling hope (cf. Ivey & Ivey, 2007; James, 2008).

Key crisis interventions

As mentioned previously, crisis intervention provides the opportunity for the crisis counsellor to help facilitate an independent decision-making process with the client by promoting them as the agent of change in their life and assisting them to identify and utilise their own resources (France, 2014).

When determining if crisis intervention is the most relevant intervention, several categories are to be considered. These include:

- a cumulative effect

- the impact on a person

- their family and community

- the unexpectedness and duration of the event or situation; and

- a person’s level of control over the event or situation (Hendricks, 1985).

Critical incident stress debriefing

Developed in 1974 by Jeffrey T. Mitchell, critical incident stress debriefing (CISD) or psychological debriefing is a seven-phase supportive crisis intervention process that was initially used with small groups of first responders such as firefighters, paramedics, and police officers to help them manage their reactions and distress following their exposure to a traumatic event (Mitchell, 1983). Over time, CISD became an intervention used with groups outside of emergency services, such as hospitals, businesses, schools, community groups and churches. However, although CISD is used extensively, current research shows mixed results for the use of this intervention with some findings suggesting that it is ineffective in preventing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and even contributing to the worsening of stress-related symptoms in individuals who received this type of intervention (Bledsoe, 2003).

The next section will address assessment in crisis intervention followed by an outline of two key crisis interventions, Roberts’ seven-stage model of crisis intervention and psychological first aid, and an application of these interventions to Brett’s case.

Assessment in crisis intervention

The responsibility of the crisis counsellor is to conduct a structured assessment in a timely and responsive manner to assess whether psychological homeostasis has been disrupted, there is evidence of dysfunction and distress, and usual coping mechanisms are not able to be utilised. Assessment is ongoing throughout the intervention process and allows the crisis counsellor to evaluate the person’s affective and cognitive state, and behavioural functioning. By assessing these three areas, the crisis counsellor can evaluate and monitor how adaptively or maladaptively the person is functioning, including whether they are a danger to themselves or others, and then apply the most appropriate intervention (James, 2008).

Listed below are examples of what a crisis counsellor is looking for across the three domains when assessing people who have experienced a crisis:

- Do they appear to be emotionally overwhelmed or severely withdrawn?

- Is what they are saying coherent and logical or are they not making sense?

- When observing their behaviours, are they pacing? Are they having difficulty breathing?

- Are they able to sit calmly?

- Are they unresponsive?

When people express suicidal ideation or have a plan to suicide, it is crucial to conduct a rapid suicide risk assessment which includes gathering information by inquiring about the following:

- How long they have been having suicidal thoughts?

- Have they made any suicide attempts in the past?

- Have they recently sought help?

- Do they have a plan to suicide?

- If they do have a plan, do they have access to the means to carry out this plan?

Further information and guidelines on suicide risk assessment can be found at the end of this chapter in the Recommended referral and resources list section. There is also a specific chapter in this book related to suicide.

Helplines – phone counselling and support

There is a range of organisations in Australia that provide support for people who are in crisis and need to talk to someone about their distress. Due to their convenience, accessibility, affordability, and relative anonymity, these helplines are a common form of crisis support.

Lifeline Australia 13 11 14

beyondblue 1300 22 4636

Mensline Australia 1300 78 99 78

Kids Help Line 1800 55 1800

1800RESPECT 1800 737 732

Roberts’ seven-stage crisis model

Roberts’ (1995, 2005) seven-stage model of crisis intervention is a cognitive-behaviourally based, systematic, and structured model used for crisis assessment and intervention. It is a common model used by crisis counsellors to help people build and restore their ways of coping and improve their problem-solving skills that a crisis may evoke.

With a focus on strengths and resiliency, these sequential stages can be applied to a broad range of crisis situations and are as follows:

- plan and conduct a thorough assessment including, danger to self and others, imminent danger, lethality

- make psychological contact, establish rapport and rapidly establish the collaborative relationship by showing genuine respect for the individual and having a non-judgmental attitude

- identify major problems or the dimensions of the problems including the precipitating event

- encourage exploration of feelings and emotions including active listening, reassurance and validation

- generate and explore alternatives including untapped resources and new coping strategies

- develop and formulate an action plan

- plan follow-up and leave the door open for booster sessions which may occur three to six months later (Roberts, 2005, p. 21).

Psychological first aid

Identified as the first level of post-incident short-term care, psychological first aid is an evidenced-based model that provides emotional and practical support to individuals, groups, and communities impacted by a natural disaster, catastrophic event, traumatic or terrorist event, or another emergency situation (Australian Red Cross & Australian Psychological Society, 2010; Ruzek et al., 2007). The aim of psychological first aid is to help people reduce their initial symptoms, have their current needs met, and support them in implementing adaptive coping strategies.

Psychological first aid meets the following four basic standards:

- Consistent with evidence and research on risk and resilience following trauma (that is, evidence-informed)

- Applicable and practical in field settings (compared with a medical/health professional office somewhere)

- Appropriate for developmental levels across the lifespan (e.g., there are different techniques available for supporting children, adolescents, and adults)

- Culturally informed and delivered in a flexible manner, as it is often offered by members of the same community as the supported individuals (Ruzek et al., 2007).

Psychological first aid is based on the understanding that, just as natural disasters, catastrophic events, traumatic or terrorist events, or other emergency situation differ vastly from each other, so do the psychological reactions of individuals, groups and communities experiencing them. Because some of these reactions can interfere with an individual’s ability to cope and manage the crisis, psychological first aid can help in their recovery. Psychological first aid has five basic elements that are to promote:

- self-efficacy (self-empowerment)

- connectedness

- hope (Hobfoll et al., 2007).

Case study: Crisis intervention

Roberts’ seven-stage model of crisis intervention

Using Roberts’ (2005) seven-stage model as an intervention with Brett, your first step is to conduct a psychosocial and lethality assessment. As he tells his story to you, you need to gather information such as whether he has any emotional support, any medical needs, how he is coping, and whether he is currently using any drugs and/or alcohol. Assessing any imminent danger and ascertaining whether Brett may be at risk of suicide is also a priority in this initial stage. Although in this case, Brett may not talk about having suicidal thoughts (i.e., suicidal ideation) or have a suicide plan, he does say, “I don’t know what the future holds for me now”, which at this point would prompt a probing question in checking what he means. It would be important to consider other risk factors, such as previous mental health issues, being socially isolated, or recently experienced a significant loss (for example, Brett has recently divorced which may be a risk factor in his case).

The second stage is about building rapport with Brett which you may have established already from taking the time to be present and hear his story in the assessment stage. This stage is crucial in developing a therapeutic relationship with Brett and, therefore, it is important you show a genuine interest in his story, respect and accept him, and also display fundamental qualities and characteristics of a crisis counsellor as discussed earlier in the chapter.

Crisis intervention is focused on the major problems, so in this next stage, you are wanting to find out why Brett has sought help now. This might seem obvious as you might assume it is the devastation of the fire. This may not be the priority issue, therefore, at this point you are not only finding out about the event that ‘was the last straw’ but you are also helping Brett prioritise the problems to work through. It is important that you gain an understanding of why those problems make it a crisis for him.

In stage four of this model (i.e., encourage exploration of feelings and emotions) you are actively listening to Brett’s story, allowing him to express and vent his feelings, and giving him the opportunity to articulate what it is about the situation that is making it difficult for him to cope. You may challenge some of his responses by giving him correct information and reframing his statements and interpretations about the situation.

Generating and exploring alternatives (stage 5) can be ‘tricky’ as the timing needs to be appropriate to help Brett explore options in moving forward to resolve the crisis. If you have established rapport, listened to his story, and Brett feels heard and understood, he may be more open to this. A strategy may include asking Brett, “How have you coped in the past when you’ve been through a crisis and felt the same way you do now?”.

Stage six includes implementing an action plan to address some of the problems he has identified, for example, making an appointment with his general practitioner regarding the poor sleep patterns he is experiencing. This stage also involves asking questions that may help Brett make meaning from the crisis such as, “Why did this happen?”, “What does it mean?”, “What are the alternatives that could have been put in place to prevent the event?”, “Who was involved?”, and “What responses to the crisis potentially made it worse (cognitively and behaviourally)?” (Roberts & Ottens, 2005).

The final stage is planning to follow up with Brett two to six weeks later in order to evaluate if the crisis is being resolved, and to also check his physical and cognitive state, how his overall functioning is, any stressors and how he is handling them, and any referrals to external agencies such as housing, medical, legal etc. You may also schedule a ‘booster’ session a month after this crisis intervention has been completed.

The application of psychological first aid to the case study requires an expansion of the five core principles of psychological first aid. In your immediate work with Brett, the intervention includes efforts to:

- reduce his distress by modelling calm, and making Brett feel safe and secure

- identify and assist Brett with his current needs

- establish a human connection with Brett

- facilitate Brett’s social support

- help Brett understand the disaster and its context

- help Brett identify his own strengths and abilities to cope

- foster belief in Brett’s ability to cope

- give Brett hope

- assist with early screening for Brett needing further or specialised help

- promote adaptive functioning in Brett

- get Brett through the first period of high-intensity and uncertainty

- set Brett up to be able to naturally recover from an event

- reduce the chance of post-traumatic stress disorder for Brett (Australian Red Cross & Australian Psychological Society, 2010, p. 11).

Brett is a 35-year-old independent Australian male farmer who may believe that expressing emotions or feelings is a sign of weakness. Bleich et al. (2003) explain that when an individual believes they are weak, “going crazy” or believes there is “something wrong with me”, an effective strategy in the intervention is to normalise and reassure Brett “you are neither sick nor crazy; you are going through a crisis, and having a normal reaction to an abnormal situation”. It is important to remind Brett that he is safe in order to minimise his vigilance. Promoting calm for Brett, immediately after his rural town was devastated by catastrophic bush fires, can assist Brett to foster positive emotions. It is advisable to intervene and limit Brett’s exposure to media coverage as this may trigger negative emotional states. The challenge for you is to convince Brett that he does not need to be as vigilant and limit media exposure as all day exposure is too much (Fredrickson, 2001).

The crisis counsellor and self-care

In their book, The Resilient Practitioner, Skovholt and Trotter-Mathison (2016) offer their insights and research on burnout and compassion fatigue for those in the helping profession and emphasise the importance of implementing self-care strategies in its prevention. Given the demands of the work of a crisis counsellor and the risk of vicarious traumatisation, protective and proactive approaches are imperative in the sustainability and vitality of a career where one is working intensely with human suffering and adversity. Tools and approaches, such as frequent supervision, high commitment to self-care, creating a personal balance of caring for self and caring for others, proactively and directly confronting stressors at work and at home, and ensuring that one has enriching relationships and activities outside of the work environment, are essential components in professional wellness and in the prevention of burnout and compassion fatigue (Adamson et al., 2014; Skovholt & Trotter-Mathison, 2016).

Learning activity 4

The development of a self-care plan can assist the crisis counsellor in supporting their wellbeing, reducing stress, and sustaining positive mental health in the long-term.

List five self-care strategies that you might use to promote and enhance your mental health and wellbeing

Counsellor reflections

Due to the nature and intensity of the role, crisis counselling may not be a suitable specialisation of counselling for every counsellor. Based on my experience, this type of work requires a counsellor to have the ability to remain calm and operate in a systematic and rational manner whilst assessing a client’s level of instability and distress. Building rapport quickly with a client facing a crisis is vital to the effectiveness of the intervention, which highlights again how important it is for the crisis counsellor to show acceptance, empathy, and genuineness to the client.

Working as a frontline crisis counsellor is demanding, and, therefore, it is imperative that ongoing support and clinical supervision are received to minimise and manage compassion fatigue and vicarious trauma. Additionally, I have found that a strong commitment to self-practices such as mindfulness, yoga, and muscle relaxation have reduced work-related stress and burnout over the years.

This chapter has provided a brief foundation for intervening with people who have experienced a crisis. With a primary focus on psychological first aid and Roberts’ seven-stage model of crisis intervention, and an application of these models to a case study, this chapter has covered the essentials in understanding the nature and types of crisis, the common reactions of a person who has experienced a crisis, and the impact of ongoing traumatic stress responses that require long-term counselling intervention. A list of other supports available, referrals and resources are included at the end of this chapter for your information and further reading.

Recommended referral and resources list

Australian Psychological Society: Psychological first aid . This resource is a useful guide to supporting people affected by a disaster. The guide provides an overview of the implementation of best practices in psychological first aid as an immediate intervention following a traumatic event or disaster.

Suicide risk assessment . Working with the suicidal person Clinical practice guidelines for emergency departments and mental health services (Department of Health, Melbourne, Victoria, 2010).

Guidelines for integrated suicide-related crisis and follow-up care in emergency departments and other acute settings (2017).

Other Resources for telephone and online crisis support:

- Life in Mind : Australian suicide prevention services.

- Standby : Support after suicide. Face-to-face and telephone support.

Other counselling resources

Psychological first aid : This video [11:07] provides information on the application of psychological first aid to assist individuals to reduce stress symptoms and assist in meeting an individual’s basic needs and identify resources to aid in a healthy recovery, immediately following a crisis, such as a personal crisis, natural disaster, traumatic event or natural disaster.

Glossary of terms

compassion fatigue— a state of feeling emotional and physically exhausted from helping people who are distressed or traumatised resulting in a diminished ability to show compassion or empathise

crisis — a time of intense difficulty or danger

hypervigilance — being in a state of increased alertness where one is sensitive to surroundings

intervention — the action or process of intervening

model — describes how counsellors can implement theories

stress — a state of mental or emotional strain or tension resulting from adverse or demanding circumstances

principles — a fundamental truth or proposition that serves as the foundation for a system of belief or behaviour or for a chain of reasoning

reaction — something done, felt, or thought in response to a situation or event

suicidal ideation — thoughts of wanting to take one’s own life or suicide

theory — a plausible or scientifically acceptable general principle offered to explain a hypothesis or belief

therapeutic relationship — refers to the consistent and close association that exists between the counsellor and client. This is also known as a therapeutic alliance.

trauma — a deeply distressing or disturbing experience

vicarious trauma — trauma symptoms that a counsellor may experience as a result of the ongoing exposure to trauma stories from their clients

Reference List

Adamson, C., Beddoe, L., & Davys, A. (2014). Building resilient practitioners: Definitions and practitioner understandings. The British Journal of Social Work, 44 (3), 522-541. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcs142

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Text revised (5th ed.). https://dsm.psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Australian Red Cross and Australian Psychological Society. (2010). Psychological first aid: An Australian guide .

Bateman, V. L. (2010) The interface between trauma and grief following the Victorian bushfires: Clinical interventions beyond the crisis, Grief Matters: The Australian Journal of Grief and Bereavement, 13 (2), 43- 48.

Behrman, G., & Reid, W. J. (2002). Post trauma intervention: Basic tasks. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 2 , 39-47.

Bledsoe, B. E. (2003). Critical incident stress management (CISM): Benefit or risk for emergency services. Prehospital Emergency Care, 7 (2), 272-279.

Bleich, A., Gelkopf, M., & Solomon, Z. (2003). Exposure to terrorism, stress-related mental health symptoms, and coping behaviors among a nationally representative sample in Israel. Journal of the American Medical Association, 290 (5) 612-616.

Caplan, G. (1961). An approach to community mental health. Grune and Stratton.

Caplan, G. (1964). Principles of preventative psychiatry. Basic Books.

Department of Health, Melbourne, Victoria (2010). Working with the suicidal person: Clinical practice guidelines for emergency departments and mental health services . www.health.vic.gov.au/mentalhealth

Dulmus, C. N., & Hilarski, C. (2003). When stress constitutes trauma and trauma constitutes crisis. The stress–trauma-crisis continuum. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 3 , 27-35.

Erikson, E. (1963). Childhood and Anxiety (2nd ed.). Norton.

Flannery, R. B., & Everly, G. S. (2000). Crisis intervention: A review . International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 2 (2), 119-125.

France, K. (2014). Crisis intervention: A handbook of immediate person-to- person help (6th ed.). Charles Thomas Pub.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broader-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist , 56 , 218-226.

Hendricks, J. E. (1985). Crisis intervention: Contemporary issues for on-site interveners . Charles C Thomas.

Herrera-Escobar, J., Osman, S., Das, S. Toppo, A, Orlas, C., Castillo-Angeles, M., Rosario, A., Janjua, M., Arain, M., Reidy, E., Jarman, M., Nehra, D., Price, M., Bulger, E., & Haider, A. (2021). Long-term patient-reported outcomes and patient-reported outcome measures after injury: the National Trauma Research Action Plan (NTRAP) scoping review. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery , 90 (5), 891–900. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000003108

Hobfoll, S. E., Watson, P., Bell, C. C., Bryant, R. A., Brymer, M. J., Friedman, M. J., Friedman, M., Gersons, B. P. R., de Jong, J. T. V. M., Layne, C. M., Maguen, S., Neria, Y., Norwood, A. E., Pynoos, R. S., Reissman, D., Ruzek, J. I., Shalev, A. Y., Solomon, Z., Steinberg, A. M., & Ursano, R. J. (2007). Five essential elements of immediate and mid-term mass trauma intervention: Empirical evidence. Psychiatry, 70 (4), 283-315.

Hoff, L. A., Hallisey, B. J., & Hoff, M. (2009). People in crisis: Clinical and diversity perspectives (6th ed.). Routledge.

Hoffer, K., & Martin, T. (2020). Prepare for recovery: Approaches for psychosocial response and recovery. Journal of Business Continuity & Emergency Planning , 13 (4), 340–351.