Masks Strongly Recommended but Not Required in Maryland

Respiratory viruses continue to circulate in Maryland, so masking remains strongly recommended when you visit Johns Hopkins Medicine clinical locations in Maryland. To protect your loved one, please do not visit if you are sick or have a COVID-19 positive test result. Get more resources on masking and COVID-19 precautions .

- Vaccines

- Masking Guidelines

- Visitor Guidelines

Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Cecelia scheeler's college essay.

I can open doors with my feet.

I developed this ability at the tender age of four after I was diagnosed with severe obsessive compulsive disorder. Since my diagnosis, my life has been a series of fluctuating dosage levels, revolving door compulsions, and mad dashes for the bathroom sink.

OCD takes many different forms, but few of them are what you see on Monk . Sure, many of us obsessive-compulsives have had the urge to take a bath in germicide or organize our wardrobe by color at one point or another, but obsessions can be about anything at all. Despite what the media may lead you to believe, OCD is not simply about cleanliness and organization. Simple routines like brushing one’s hair can become a two hour process. But over the past few years, I have realized that my disorder doesn'’t need to be an obstacle in my path to success.

That’s not to say that it hasn’t been a rough ride. After my initial diagnosis, I was prescribed medication and had few symptoms throughout elementary school. Occasionally, I would relapse, and then I would start flicking light switches on and off and on and off and on and off and on and off at a seizure-inducing pace. But eventually, the lights would stay off, and I’d walk away.

Then came middle school.

I don’t think anyone enjoys middle school. Most people have horror stories to tell about the time they were hit up for their lunch money or given a swirly in the toilet or some other such misery. But I can say with a certain amount of confidence that my middle school experience was probably worse than most.

I entered sixth grade at the age of ten, just as puberty set in at full force, changing my body chemistry in a way that caused my medication to stop working entirely. This was unfortunate, as middle school kids tolerate weirdness about as well as Glenn Beck “tolerates” Obama. I was given a number of nasty nicknames and I quickly carved out a comfy little niche for myself at the low end of the popularity scale. At the high end was Heaven (no, really, that was her name), a girl with white-blond hair and an orange, spray-on tan. At the opposite end was me, the girl who would, on occasion, make weird noises at the back of her throat and shake her head like a wet dog.

High school has been a vast improvement. My peers at Carver Center for Arts and Technology are understanding and supportive. My dosage levels are stable. I no longer possess some of the more noticeable tics (such as the “wet dog shake”), though I have since gained a particularly consistent tic that involves typing certain words multiple multiple multiple multiple multiple multiple multiple times. That’s the thing about OCD. It’s always there. Whenever you get rid of one obsession, a shiny new one takes its place. It’s like Netflix, except it’s not as cool.

In the summer before my senior year, I resolved to step outside my narrow comfort zone, and so I attended a Japanese language immersion camp in rural Minnesota for two weeks. During that time, I shared a bathroom with sixty other girls, took five-minute showers, slept in a bug infested cabin, and managed not to have a total OCD meltdown. From this experience, I realized that my OCD can’t dictate what I am capable of doing. I proved to myself that I’m perfectly able to have new experiences that will push me beyond my boundaries – I now feel confident that I can succeed in the new and unfamiliar environment of college.

These days, I’ve been opening doors with the appropriate appendage.

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

100 OCD Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

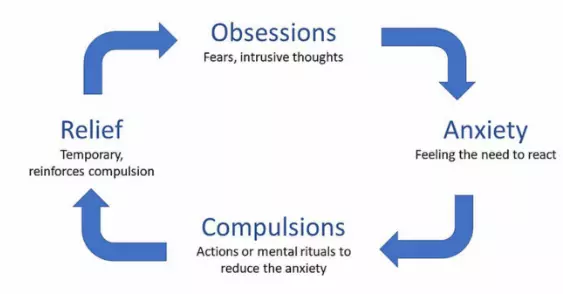

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a mental health condition characterized by intrusive thoughts and repetitive behaviors. People with OCD often struggle with unwanted thoughts or obsessions that cause anxiety, leading them to engage in rituals or compulsions to alleviate their distress. If you are studying psychology or mental health, writing an essay on OCD can be a fascinating and informative topic. To help you get started, here are 100 OCD essay topic ideas and examples:

- The history and evolution of OCD as a recognized mental health disorder.

- Common obsessions and compulsions associated with OCD.

- The prevalence of OCD in different demographic groups.

- The role of genetics in the development of OCD.

- How OCD is diagnosed and treated in clinical settings.

- The relationship between OCD and other mental health disorders, such as anxiety and depression.

- The impact of OCD on daily functioning and quality of life.

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy as a treatment for OCD.

- The use of medication in managing OCD symptoms.

- The stigma and misconceptions surrounding OCD.

- The neurobiological basis of OCD.

- The effects of childhood trauma on the development of OCD.

- The link between OCD and perfectionism.

- The role of family dynamics in the maintenance of OCD symptoms.

- The impact of OCD on relationships and social interactions.

- The effectiveness of exposure therapy in treating OCD.

- The relationship between OCD and hoarding disorder.

- The cultural differences in the presentation and treatment of OCD.

- The impact of OCD on academic and occupational performance.

- The use of mindfulness techniques in managing OCD symptoms.

- The role of stress in triggering OCD symptoms.

- The challenges of living with OCD in a society that values productivity and efficiency.

- The role of self-care in managing OCD symptoms.

- The link between OCD and body dysmorphic disorder.

- The comorbidity of OCD with substance use disorders.

- The impact of media portrayals of OCD on public perceptions.

- The relationship between OCD and eating disorders.

- The effectiveness of virtual reality therapy in treating OCD.

- The role of peer support groups in managing OCD symptoms.

- The impact of trauma-focused therapy on OCD symptoms.

- The relationship between OCD and intrusive thoughts.

- The use of relaxation techniques in managing OCD symptoms.

- The impact of OCD on financial well-being.

- The effectiveness of teletherapy in treating OCD.

- The link between OCD and trichotillomania (hair-pulling disorder).

- The role of exercise in managing OCD symptoms.

- The relationship between OCD and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

- The impact of sleep disturbances on OCD symptoms.

- The use of art therapy in managing OCD symptoms.

- The effectiveness of group therapy in treating OCD.

- The relationship between OCD and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- The impact of stigma on help-seeking behaviors among individuals with OCD.

- The role of peer support groups in reducing feelings of isolation among individuals with OCD.

- The relationship between OCD and substance use disorders.

- The impact of OCD on romantic relationships.

- The use of cognitive restructuring in managing OCD symptoms.

- The relationship between OCD and social anxiety disorder.

- The role of mindfulness-based stress reduction in treating OCD.

- The impact of OCD on academic performance.

- The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy in managing OCD symptoms.

- The relationship between OCD and body-focused repetitive behaviors (e.g., skin picking).

- The impact of stigma on treatment adherence among individuals with OCD.

- The role of animal-assisted therapy in managing OCD symptoms.

- The relationship between OCD and impulse control disorders.

- The impact of OCD on family dynamics.

- The use of biofeedback in managing OCD symptoms.

- The relationship between OCD and sleep disorders.

- The impact of OCD on self-esteem.

- The role of occupational therapy in managing OCD symptoms.

- The relationship between OCD and personality disorders.

- The impact of OCD on parenting.

- The use of exposure and response prevention therapy in treating OCD.

- The relationship between OCD and emotional dysregulation.

- The impact of OCD on physical health.

- The role of dialectical behavior therapy in managing OCD symptoms.

- The relationship between OCD and schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

- The impact of OCD on social functioning.

- The use of technology in managing OCD symptoms (e.g., apps, online therapy).

- The relationship between OCD and trauma-related disorders.

- The impact of OCD on cognitive functioning.

- The role of spirituality in managing OCD symptoms.

- The relationship between OCD and attachment disorders.

- The impact of OCD on body image.

- The use of exposure therapy in managing OCD symptoms in children.

- The relationship between OCD and neurodevelopmental disorders.

- The role of family therapy in managing OCD symptoms.

In conclusion, writing an essay on OCD can be a rewarding experience, allowing you to explore the complexities of this mental health condition and its impact on individuals' lives. With these 100 essay topic ideas and examples, you can delve into various aspects of OCD and contribute to the understanding and awareness of this disorder. Good luck with your essay writing!

Want to research companies faster?

Instantly access industry insights

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Leverage powerful AI research capabilities

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2024 Pitchgrade

OCD is so much more than handwashing or tidying. As a historian with the disorder, here’s what I’ve learned

PhD Candidate in History, University of Sheffield

Disclosure statement

Eva Surawy Stepney receives funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) via the White Rose College of the Arts and Humanities (WRoCAH).

University of Sheffield provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Readers are advised that this article contains explicit discussion of suicide and suicidal and obsessional thoughts. If you are in need of support, contact details are included at the end of the article.

At the age of 12, “out of nowhere”, Matt says he started having repetitive thoughts concerning whether he wanted to end his life. Every time he saw a knife, he would ask himself: “Am I going to stab myself?” Or, when he was near a ledge: “Am I going to jump?”

Matt had heard a lot about teenage depression, and thought this must be what was going on. But it was confusing, he says: “I didn’t feel suicidal, I really enjoyed my life. I just had an intense fear of doing something to hurt myself.”

Shortly afterwards, pre-empted by hearing about a notorious banned film, Matt began questioning whether he, like the central character, might be a serial killer. These thoughts “kept coming and coming” and he would lie in bed running over scenarios, trying to work out whether he was “going crazy”:

I really needed help. I didn’t know who to talk to. But it wasn’t on my radar to think about this as OCD.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a significant mental health diagnosis in the 21st century. The World Health Organization (WHO) lists it as one of the ten most disabling illnesses in terms of loss of earning and reduced quality of life, and OCD is frequently cited as the fourth most common mental disorder globally after depression, substance abuse and social phobia (anxiety about social interactions).

Yet everything Matt knew about OCD, he tells me, came from daytime talkshows where “people were washing their hands 1,000 times a day – it was all about external and really extreme behaviours”. And that didn’t feel like what he was going through.

Across the world, we’re seeing unprecedented levels of mental illness at all ages, from children to the very old – with huge costs to families, communities and economies. In this series , we investigate what’s causing this crisis, and report on the latest research to improve people’s mental health at all stages of life.

A similar experience is recounted in the 2011 book Taking Control of OCD by John (not his real name) who, after a colleague had taken their own life, became “inundated with thoughts” about what he might do to himself. Every time he crossed the road, John thought: “What would happen if I stopped moving and was run over by a bus?” He also had thoughts of murdering those he loved. John recalled:

Try as I might, I just couldn’t chase the thoughts out of my head … When I tried to explain what was going on to my girlfriend, I couldn’t find a way of articulating what was happening to me … At the time, I thought OCD was all about triple-checking you had locked the front door and that your drawers were tidy.

Despite the prevalence of OCD in contemporary society, the experiences of Matt and John reflect two important features of this disorder. First, that the stereotype of OCD is one of washing and checking behaviours – the compulsions aspect, defined clinically as “repetitive behaviours that a person feels driven to perform”. And that obsessions – defined as “ unwanted, unpleasant thoughts ” often of a harmful, sexual or blasphemous nature – are viewed as obscure, confusing and unrecognisable as OCD.

People who experience obsessional thoughts are therefore frequently unable to identify their symptoms as OCD – and neither , very often, are the experts they see in clinical settings. Due to mischaracterisations of the disorder, OCD sufferers with non-typical, less visible presentations usually go undiagnosed for ten or more years .

When John visited his GP, he was diagnosed with depression. He recalled that the GP concentrated more on the visible effects of his distress - a lack of appetite and disrupted sleeping patterns. The thoughts remained invisible. As he put it:

I don’t know how you’re supposed to tell someone you don’t know that you have thoughts about killing people you love.

Even for those with “textbook” OCD such as my friend Abby, “the compulsion is just the tip of the iceberg”. Abby was able to self-diagnose at the age of 12, when she experienced handwashing and locking door compulsions. She says people still think of her as “Abby [who] likes to wash her hands a lot”.

Now, she tells me, “I realise that I have no interest in washing my hands – I’m a pretty messy person, and I don’t mind other people being messy.” Rather than a love of cleaning, her acts were related to the altogether scarier obsessional thought: “What if I am going to hurt other people?”

Clinical guidelines, such as those provided in the UK by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence , define OCD as being characterised by both compulsions and obsessions. So, why do the difficulties encountered by Matt, John and Abby – of recognising the internal thoughts that dominate their lives – appear to be so common ?

My experience of OCD

From the age of 16, I have also suffered with thoughts that I later came to associate with OCD, but which began as invisible and tormenting. An article I wrote in 2014, entitled The Unseen Obsession , described my experience of having left university midway through my studies due to a single thought that gathered “such power that I even ended up attacking my body in an attempt to eliminate its force”. I wrote:

I have suffered with obsessional thoughts for the last four years, and can safely say that [OCD] is far from being about clean hands.

My obsessions have taken many forms since my teenage years. They began with me wondering whether things really existed, whether my parents were really who they said they were, and whether I wanted to harm – and was a risk to – my family, friends, even my dog.

Many of us know what it is like to ruminate about a person, a conflict, or something else we feel anxious about. But for those with obsessional thoughts (diagnosed or otherwise), this is quite different to simply “overthinking”. As I attempted to explain in my article:

Conversations falter as the thought leaps through your mind. Other topics seem less important, and time to yourself provides space to assess, analyse, and look for evidence of the thought being ‘true’ … [Obsessing] is like fighting: you push and shove your thoughts away and they come back with twice as much force. You spend time trying to avoid them and they pop up everywhere, taunting and mocking your failed attempt at running away.

It took me six months of weekly therapy sessions before I felt able to voice my obsessional thought to my therapist – someone I had known for a number of years. My unwillingness to be open about it was not only tied up with feelings of shame about its taboo content, but also my inability to see such thinking as part of a recognised disorder.

The question of what constitutes OCD, why we understand – and misunderstand – it as we do, as well as my own experience of living with it, led me to study how OCD became recognised and categorised as a mental health disorder .

In particular, my research shows that there are important insights to be gained from the research decisions made by a group of influential clinical psychologists in south London in the early 1970s – shedding light on why so many people, myself included, still struggle to recognise and make sense of our obsessional thoughts.

The origin of the concepts

Categories of mental illness are not stable across time. As medical, scientific, and public knowledge about an illness changes, so does how it is experienced and diagnosed.

Prior to the 1970s, “obsessions” and “compulsions” did not exist in a unified category – rather, they appeared in an array of psychiatric classifications. At the start of the 20th century, for example, British doctor James Shaw defined verbal obsessions as “a mode of cerebral activity in which a thought – mostly obscene or blasphemous – forces itself into consciousness”.

Such cerebral activity could, according to Shaw, arise in hysteria, neurasthenia , or as a precursor to delusions. One of his patients – a woman who experienced “irresistible, obscene, blasphemous and unutterable thoughts” – was diagnosed with obsessional melancholia, a “form of insanity”.

The symptom arose from what Shaw defined as “nervous weakness”, an explanation that reflected the broader 19th-century view that obsessional thoughts were indicative of a fragile nervous system – either inherited, or weakened through overwork, alcohol or promiscuous behaviour (described as “ degeneration theory ”). Notably, Shaw did not mention any form of repetitive behaviour in relation to these verbal obsessions.

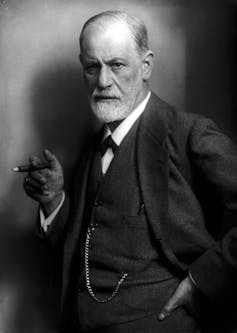

At a similar time to Shaw’s writings, Sigmund Freud, the Austrian founder of psychoanalysis, developed his psychoanalytic category of “ Zwangsneurose – translated in Britain as "obsessional neurosis” and in the US as “compulsion neurosis”. In Freud’s writings , the “Zwang” referred to persistent ideas that emerged from a repressed conflict between unresolved childhood impulses (those of love and hate) and the critical self (ego).

Freud’s most famous case study , published in 1909, featured the “Rat Man”, a former Austrian army officer who possessed a variety of elaborate symptoms. In the first instance, he had become obsessed that he would fall victim to a horrific rat-based punishment that had been recounted to him by a colleague. The patient also expressed that if he had certain desires such as a wish to see a woman naked, his already-deceased father “will be bound to die”.

The Rat Man was described by Freud as engaging in a “system of ceremonial defences” and “elaborate manoeuvres full of contradictions” that have been read by some as the behavioural aspects of what would become OCD. However, there are crucial differences between the “defences” of Freud’s client and the compulsions of OCD, including that the former largely involved thinking rather than acting, and were by no means consistent or stereotyped.

This article is part of Conversation Insights The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

The psychoanalytic category of “obsessional neurosis” was adopted and modified in Britain during the first world war, and became a staple – but inconsistently defined – diagnosis in British psychiatric textbooks of the inter-war period. Up to the 1950s, the terms “obsession” and “compulsion” were being used interchangeably in psychiatric writing. The complexity surrounding their meaning is demonstrated in the writings of Aubrey Lewis , a leading figure in post-war British psychiatry, who referred to “obsessional illnesses” as being made up of “compulsive thoughts” and “compulsive inner speech”.

Like Freud, Lewis mentioned the “complex rituals” of the obsessional – such as the patient “who is perpetually putting himself in the greatest trouble to ensure that he never steps on a worm inadvertently”. But he cautioned against “the dangers of associating any kind of repetitious activity with obsessionality”, writing that “it certainly cannot be judged on behaviourist grounds”.

Defining OCD by visible behaviour

OCD began to emerge in the form we recognise it today from the early 1970s – and was established as a formal psychiatric disorder through its inclusion in the third and fourth editions of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (commonly known as DSM-III and DSM-IV) in 1980 and 1994.

The centrality of visible and measurable behaviours in the categorisation of OCD – particularly washing and checking – can be traced back to a series of experiments conducted by clinical psychologists in the early 1970s at the Institute of Psychiatry and the Maudsley Hospital in south London.

Under the direction of South African psychologist Stanley Rachman, the complex array of symptoms contained in the categories of obsessional illness and obsessional neurosis were divided into two: “visible” compulsive rituals, and “invisible” obsessional ruminations. While Rachman and his colleagues conducted a large research programme on compulsive behaviours, obsessions were relegated to the backburner.

For example, in their investigation of ten psychiatric inpatients diagnosed with obsessional neurosis, “compulsions had to be present for entry into the trial and patients complaining of ruminations were excluded” – a statement reiterated throughout subsequent experiments.

Indeed, this study did not merely require patients to exhibit some form of visible compulsion. The ten patients included were exclusively those with “visible handwashing” behaviour, which was viewed as the “easiest” symptom to experiment on. Likewise, the second round of studies only included patients who engaged in visible “checking” behaviour, such as whether a door was unlocked.

In a 1971 paper , Rachman offered his rationale for taking this approach, explaining how “obsessional ruminators raise special problems for the clinical psychologist because of their subjective, private nature”. This, he argued, was in contrast with “the other main feature of obsessional neurosis, compulsive behaviour, which can be approached with greater ease. It is visible, has a predictable quality, and many reproducible analogies in animal research”.

Rachman viewed compulsions as “visible” and “predictable” in large part due to the way clinical psychology had developed as a new profession in Britain, at the Maudsley Hospital in particular, in the decades following the second world war. To differentiate their practice from the existing mental health professions of psychiatry (medically trained doctors specialising in mental health) and psychoanalysis (talking therapy derived from Freud), these early clinical psychologists presented themselves as “ applied scientists ” who brought scientific methods from the laboratory to a clinical setting. Their conception of science was rooted in empiricism – with an emphasis on visibility, measurability and experimentation.

As part of this commitment to empirical science, these clinical psychologists adopted a model of anxiety derived from 20th-century behaviourism. This focus on observable behaviour was viewed as having much greater scientific value than psychoanalysis, which dealt with the “ unverifiable ” and “unscientific” realm of thoughts and thinking.

So, when obsessional ruminations gained a renewed focus in the mid-1970s, it was through this lens of visible compulsive behaviours. Rachman and his colleagues started talking about “mental compulsions” (such as saying a good thought after a bad thought) as “equivalent to handwashing”- rather than focusing on the importance and content of these thoughts in their own right.

In the early 1980s, clinical psychology came under pressure from cognitive psychologists (those concerned with thinking and language) for its reductive focus on behaviour. But despite this move to include cognitive approaches , the centrality of visible behavioural compulsions has continued to characterise perceptions of OCD in cultural and clinical domains.

This is perhaps most evident in media portrayals of the disorder – a critique taken up by cultural scholars such as Dana Fennell , who look at representations of OCD in TV and film.

The archetypal portrayal of OCD has not been helped by the recent publicity given to David Beckham and his extensive tidying . When I ask Abby what she thought about the attention that Beckham’s OCD was receiving in the media, she replies: “It’s so boring. It’s the same presentation that always gets thought of as OCD.”

Limitations to the ‘gold standard’ treatment

This archetypal portrayal of OCD also relates to how it is treated. The “gold standard” treatment in the UK today is the behavioural technique of exposure and ritual prevention (ERP), either on its own or combined with cognitive therapy. ERP gained acceptance from the experiments of Rachman and colleagues in the early 1970s, when they were exclusively working with patients with observable behaviours.

One of their key studies involved patients from the Maudsley Hospital who repeatedly washed their hands. They were told to touch smears of dog excrement and put hamsters in their bags and in their hair, while being prevented from washing for increased lengths of time.

Such experiments were again governed by observability and measurability. The “success” of ERP treatment – and its perceived superiority over psychiatric and psychoanalytic methods – was demonstrated by a reduction in the patients’ visible handwashing behaviour.

Today, if you are diagnosed with OCD by a psychiatrist and given OCD-specialist treatment via the NHS, you will most likely be told to undergo the same kind of ERP procedure that hospital inpatients were experimentally given in the 1970s: touching a set of items that you fear (exposure) while being prevented from engaging in your usual compulsive behaviour.

An identical method is also used when it comes to obsessional thoughts. Patients are asked to identify their worrying obsession, then either expose themselves to provoking situations or repeat the thought in their mind without engaging in “mental compulsions” – such as counting, replacing a bad thought with a good thought, or trying to “solve” the content of the obsessional thought.

It’s certainly true that this form of behavioural therapy can be hugely helpful in the treatment of OCD symptoms. Abby, after undergoing ERP for 14 years, said she had “developed a lot of practices around not giving into my [washing and checking] compulsions”.

I also found the approach beneficial in reducing the threatening quality of my obsessional thoughts. Repeating “I want to hurt my family” or “I don’t really exist” to myself over and over again, without actually trying to solve these issues, reduced the time I spent ruminating.

However, while being a huge advocate of ERP, Abby also observed that “sometimes when I get rid of a compulsion, it doesn’t mean I just get rid of the obsession.” While the “outward compulsions” disappear, “it doesn’t mean my mind stops cycling and mental questioning”.

Some contemporary clinicians have referred to ERP, designed around visible symptom reduction, as a “ whack-a-mole technique ” – you get rid one symptom (obsession or compulsion) and another pops up.

ERP is frequently accompanied with cognitive therapy techniques, such as cognitive restructuring (identifying beliefs and providing evidence for and against them), or being told that obsessions are “just thoughts”, that they are meaningless, and that you do not want to enact them.

Despite the success of cognitive-behaviour therapy (CBT) and ERP in scientific trials, a major review of evidence in 2021 questioned whether the effects of the approach in treating OCD had been overstated – reflecting the high proportion of OCD cases that are designated as “ treatment resistant ”.

I also believe there are some crucial limitations to contemporary treatments for OCD. Exposure (ERP) techniques stem from a period in which thoughts were not being considered at all by clinical psychologists, while CBT designates the content of obsessional thoughts as unimportant. Matt, like me, has found that CBT “can only take you so far”, explaining:

Part of this was that [CBT therapists] are so committed to the idea that thoughts don’t have meaning … [They] treat your symptom and once those are gone, you should get on with your life. I didn’t find that there was a way of thinking about [my] ruminations in the context of my whole life.

Experiences of alternative treatments

So much of my understanding about OCD has changed since I first wrote about it for Rethink Mental Illness almost a decade ago. Thinking about the historical development and categorisation of OCD has, it turns out, given me a greater sense of ease regarding this widely misunderstood condition. I feel less bound by our current conceptual frameworks, and more able to reflect on what I think is helpful in terms of how to successfully manage my obsessional thoughts.

For example, despite being warned away from psychoanalysis from a young age (my mum is a clinical psychologist, and psychologists are often fervently anti-psychoanalytic!), I have found psychoanalysis incredibly helpful in becoming comfortable with my thoughts.

This is because CBT typically focuses on present symptoms without looking into their meaning or how they relate to your personal history, and this comes into tension with my desire, as a historian, to think about the past. In contrast, psychoanalysis locates obsessional thoughts in history – pointing to childhood as a crucial point of psychic development. I have been able to understand my obsessions as the result of a deep childhood fear concerning the death of my loved ones, from which I developed a rigid desire for control.

As a young teenager trying to determine what was going on with him, Matt went to the public library and took out a Freud reader . He describes this as “the worst possible thing for a 14-year-old to read”, as it made him believe “that I did really have all these [murderous suicidal] impulses and all my fears are true”.

Despite this experience, while training to become a social worker, he “got into psychoanalysis as an alternate way to think about therapy and think about my own experience”. For him, psychoanalysis revealed the opposite to the image of “OCD as handwashing”.

Instead, he says, it focused on the aspects of “obsessionality that are internal”, showing him that the “mind is so powerful that it can produce a lot of imaginary fears”. It also allowed him to see “OCD symptoms as wrapped up with my whole life”.

Particularly profound in psychoanalytic thought is the acceptance of the complexity and unknowability at the heart of human experience. As Jaqueline Rose, professor of humanities at Birkbeck, University of London, wrote: :

Psychoanalysis begins with a mind in flight, a mind that cannot take the measure of its own pain. It begins, that is, with the recognition that the world – or what Freud sometimes refers to as ‘civilisation’ – makes demands on human subjects that are too much to bear.

This idea of “a mind in flight” has helped me think about my obsessions – whether my parents are really who they say they are; am I going to hurt those I love? – as part of a battle for certainty and control that is both unattainable and understandable, considering the world we live in.

The aim of psychoanalytic treatment is not to eradicate symptoms but to bring to light the difficult knots that humans have to deal with. Matt refers to psychoanalysis as acknowledging “a sort of messiness of the mind … I’ve found the psychoanalytic view of accepting your own messiness extremely helpful”. Rose similarly describes psychoanalysis as “the opposite of housework in how it deals with the mess we make”.

In the UK, psychoanalysis has been rejected within NHS service provision. And I believe this is, at least in part, a result of historical critiques levelled at it by clinical psychologists as they developed behaviour therapies to treat OCD in the late 20th century.

‘A lot of emotion and sadness’

While compulsive behaviour such as handwashing and checking is widely perceived as “representative” of OCD, the tormenting experience of having obsessional thoughts is still rarely acknowledged and discussed. The shame and confusion attached to such thoughts, coupled with the feeling of being misunderstood, make this an important issue to address, particularly when misdiagnosis of OCD is so high.

My PhD on the history of OCD has also showed me the ways in which psychological research shapes how we conceive of diagnostic categories – and consequently, ourselves. While psychology’s commitment to objectivity, empiricism and visibility has provided tools that are tremendously useful in the clinic, my research sheds lights on how the often-exclusive focus on visible symptoms has at times trumped the appreciation of the complex experience of having obsessional thoughts.

I first met Matt in 2019 at the first OCD in Society conference, held at Queen Mary University of London, where he was giving a presentation on the “multiple meanings of OCD”. We discussed our own experiences of the disorder, and what we thought that history, psychoanalysis and anthropology could contribute to understandings of OCD.

Matt was 34, and he told me this was the first time he “had ever voiced the internal stuff out loud, and heard other people talk about it”. Recalling how this made him feel, he continued:

I felt a lot of emotion and sadness. The isolation had been such a big part of my life that I had stopped noticing it. Then being out of the isolation was such a relief, it made me realise how bad it had been.

If you are experiencing suicidal thoughts and need support, you can call your GP, NHS 111 , or free helplines including Samaritans (116 123), Calm (0800 585858) or Papyrus (0800 068 4141).

In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Hotline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is on 13 11 14. Hotlines in other countries can be found here .

For you: more from our Insights series :

How to solve our mental health crisis

How music heals us, even when it’s sad – by a neuroscientist leading a new study of musical therapy

Unlocking new clues to how dementia and Alzheimer’s work in the brain – Uncharted Brain podcast series

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter .

- Mental health

- Sigmund Freud

- Mental illness

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder

- Mental illness stigma

- Mental health care

- Psychoanalysis

- Insights series

- Obsessive compulsive disorder

- Tackling the mental health crisis

Indigenous Graduate Research Program Coordinator

Director of STEM

Community member - Training Delivery and Development Committee (Volunteer part-time)

Chief Executive Officer

Head of Evidence to Action

97 OCD Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best ocd topic ideas & essay examples, 🥇 most interesting ocd topics to write about, 📌 simple & easy ocd essay titles, ❓ ocd research questions.

- Intake Report and Treatment Plan: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) According to Joan, her whole life from childhood has been accompanied by her overambitious to achieve in every task, her conscientious nature, never-making mistakes behavior, and her avoidance to indicate the presence of a mistake […]

- OCD: The Four D’s Diagnostic Indicators Firstly, obsessive thoughts often interfere with the usual people’s acts and cause a surge of panic, disturbing to complete their work.

- Obsessive – Compulsive Personality Disorder: Diagnosis and Treatment Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder is the term used to refer to a mental condition in which a victim is too preoccupied with perfectionism, orderliness, and interpersonal and mental control, at the expense of efficiency, openness and […]

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder One of them is the Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder the syndrome which causes people to have recurring, unwanted thoughts and drives them to uncontrollable, repetitive actions.

- The Obsessive-Compulsive Psychological Disorder In addition, the disorder affects the way he relates with the likes of Simon Bishop and the gay painter both of whom are his neighbors.

- Psychological Issues: Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Nevertheless, the study showed that the majority of the correspondents who suffered from the disease were Judaism. Moreover, individuals suffering from the disorder refrain from visiting hospitals in fear of humiliation and guilt attributed to […]

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: Definition, Types and Causes Efforts to raise people’s awareness about OCD have been on the rise since the late 1990s and the first decade of the 21st century.

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in an Asian American Patient The issue of substance use should also be addressed as one of the possible factors that may have exacerbated the patient’s sense of anxiety and prompted the aggravation of her OCD.

- Discussion: Anxiety Disorder and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders To be diagnosed with a specific phobia, one must exhibit several symptoms, including excessive fear, panic, and anxiety. Specific phobias harm the physical, emotional, and social well-being of an individual.

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder in Adults Obsessive Compulsive Disorder is an anxiety disorder that is represented by uncontrollable, repetitive and unwanted thoughts.

- Neurotransmission and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder The proteins and the other substances that the neuron needs for its function are manufactured by the cell body or soma and the nucleus and the neuron is known as the “manufacturing and recyling plant”.

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in a Young Woman After Bess’s mother’s serious intervention into the course of her life, Bess was absorbed in her studies and later in her work.

- Psychodynamic and Cognitive-Behavioral Approaches of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder In this article, after overviewing both the psychodynamic and cognitive behavioral models of OCD, Kempke and Luyten point out that as opposed to the cognitive behavioral model, the arena of psychodynamic approach to OCD is […]

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Minor Psychiatric Illnesses However, the severe obsessive-compulsive disorder may lead to major incapacitation adversely affecting the life of the victims. When an individual exhibits or complains about obsession or compulsion or both to the extent that his normal […]

- Howard Hughes’s Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder The purpose of this paper is to discuss the obsessive-compulsive disorder in the case of Howard Hughes, with the help of the Big Five personality model.

- Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder and Care Hospitalization is a rare treatment method for patients who have an obsessive compulsory personality disorder. For instance, new drugs such as Prozac and SRRI are proved to offer a reprieve to patients suffering obsessive compulsory […]

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Diagnostics Developmental Disorder: No diagnosis No diagnosis can be made since the woman used to be an active member of her community. Medical Disorder: No diagnosis The client maintains that she does not have medical issues.

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Its Causes While it is possible to clearly articulate the symptoms of OCD, the final and definite answer to the question about the causes of the disorder is yet to be found. Currently, it is hypothesised that […]

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Diagnosis and Therapy The ritual, i.e, the street corner, may be a response to an obsessional theme or a way to lower an underlying anxiety.

- Experience of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder The obsessive-compulsive disorder is a rather common psychiatric illness, which has a tendency to occupy a significant time in the mind of the patient and provides a feeling that he/she is not in control of […]

- Mindfulness Therapy for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder It is important to introduce the patient to the mindfulness intervention as early as possible by inviting him to take part in a 5-minute mindfulness-of-breath exercise in order to note particular reflections about the nature […]

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) – Psychology The other sign relates to the fear of lacking the need in life and consequently losing whatever has been acquired and is in possession.

- The Treatment of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder Thus, Madam Y is to be convinced of the therapist’s good intentions. Unconditional positive regard is also one of the most important ways which is to be used to help Madam Y.

- Brief Overview of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) The strange acts torment the mind and the distractions affect the social wellbeing of the patient. The brain has the “orbital frontal cortex” that is responsible of reporting and soliciting the rest of the brain […]

- Freud’s Theory of Personality Development and OCD The ego, on the other hand, is in the middle and manages both the desires of the Id and those of the superego.

- Invasive Circuitry-Based Neurotherapeutics: Stereotactic Ablation and Deep Brain Stimulation for OCD

- Autism Spectrum Traits in Children and Adolescents With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Symptoms Predict Poorer Response to Gamma Ventral Capsulotomy for Intractable OCD

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Anxiety and OCD Spectrum Disorders

- Identical Symptomatology but Different Diagnosis: Treatment Implications of an OCD Versus Schizophrenia Diagnosis

- Childhood-Onset Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Tic-Related Subtype of OCD?

- Reduced Anterior Cingulate Glutamatergic Concentrations in Childhood OCD and Major Depression Versus Healthy Controls

- Neural Responses of OCD Patients Towards Disorder-Relevant, Generally Disgust-Inducing, and Fear-Inducing Pictures

- Dealing With Corona Virus Anxiety and OCD

- The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Patients With OCD

- Recent Life Events and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD): The Role of Pregnancy & Delivery

- Basic Neurotransmission and the Psychotropic Treatment of OCD

- The Characteristics, Common Symptoms, and Treatments of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), a Neurological Anxiety Disorder

- Social Factors That May Contribute or Result From OCD

- Are “Obsessive” Beliefs Specific to OCD?: A Comparison Across Anxiety Disorders

- Wisconsin Card Sorting Task (WCST) Errors and Cerebral Blood Flow in Obsessive‐Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) Between ADHD and OCD

- Treatment Non-response in OCD: Methodological Issues and Operational Definitions

- The Symptoms, Treatment, and Combination of Therapies for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- The Other Side of COVID-19: Impact on Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and Hoarding

- Should OCD Be Classified as an Anxiety Disorder in DSM‐V?

- Evaluation of Biological Explanations of OCD

- OCD in Children and Adolescents: A Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment Manual

- A New Infection-Triggered, Autoimmune Subtype of Pediatric OCD and Tourette’s Syndrome

- Parents With OCD and the Influences on Children

- Social Movements and Awareness and Educate the Public About OCD

- Hoarding in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Results From the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study

- Women Are at Greater Risk of OCD Than Men: A Meta-Analytic Review of Ocd Prevalence Worldwide

- Compulsive Hoarding: OCD Symptom, Distinct Clinical Syndrome, or Both?

- Does Comorbid Major Depressive Disorder Influence Outcome of Exposure and Response Prevention for OCD?

- Repeated Cortico-Striatal Stimulation Generates Persistent OCD-Like Behavior

- Quality of Life in OCD: Differential Impact of Obsessions, Compulsions, and Depression Comorbidity

- What Should the Diagnostic Criteria for OCD Be?

- Characterizing the Hoarding Phenotype in Individuals With OCD: Associations With Comorbidity, Severity, and Gender

- Compassion-Focused Group Therapy for Treatment-Resistant OCD: Initial Evaluation Using a Multiple Baseline Design

- High Rates of OCD Symptom Misidentification by Mental Health Professionals

- Widespread Structural Brain Changes in OCD: A Systematic Review of Voxel-Based Morphometry Studies

- Causes and Triggers for Obsessive Compulsive-Disorder (OCD)

- Distinct Subcortical Volume Alterations in Pediatric and Adult OCD: A Worldwide Meta- and Mega-Analysis

- Treating OCD With Exposure and Response Prevention

- What Is OCD Behaviour?

- What Are the Types of OCD?

- Is OCD a Form of Anxiety?

- What Causes OCD?

- What Are the Main Symptoms of OCD?

- Is OCD a Mental Disability?

- Can OCD Be Fully Cured?

- How Can You Tell if Someone Has OCD?

- What Happens if OCD Is Not Treated?

- Is OCD a Permanent Condition?

- How Long Does OCD Usually Last?

- What Are the Main Causes of OCD?

- How Many People With OCD Recover?

- What Does Undiagnosed OCD Look Like?

- Is OCD a Form of Addiction?

- Can OCD Be Triggered by Trauma?

- What Childhood Trauma Causes OCD?

- How OCD Takes the Living Out of Life?

- What Is Childhood and Adolescent OCD?

- How Is OCD Treated for Children With Compulsive Disorder?

- What Analysis of Genome-Wide Associations of Complications of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder?

- How Are OCD and Genes Related?

- Can OCD Cause Psychosis?

- Who Is Most Commonly Affected by OCD?

- Gambling Essay Titles

- Bipolar Disorder Research Ideas

- ADHD Essay Ideas

- Bulimia Topics

- Anorexia Essay Ideas

- Disorders Ideas

- Abnormal Psychology Paper Topics

- Dissociative Identity Disorder Essay Topics

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, March 2). 97 OCD Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/ocd-essay-topics/

"97 OCD Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 2 Mar. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/ocd-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2024) '97 OCD Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 2 March.

IvyPanda . 2024. "97 OCD Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/ocd-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "97 OCD Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/ocd-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "97 OCD Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/ocd-essay-topics/.

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- Conditionally

- Newsletter Signup

This Is What It's Like To Live With OCD

Courtesy of the writer

I am not shy about having OCD. On the contrary, I am obnoxiously vocal about it. I talk about it, I write about it, and I laugh about it. Constantly. When I applied to college, OCD was the topic of my personal essay. I joked that OCD is a lot like Netflix in that, as soon as you send one symptom back to the distributor, you get a shiny new one in the mail. (Yeah, I wrote that essay in 2010 and it’s already ridiculously dated. Netflix once sent DVDs through the mail . Those were dark times.)

I don’t talk about my OCD with anything even approaching sincerity. I handle most of my problems through a thick veneer of sarcasm and mockery. It provides a comfortable distance from something that can otherwise be overwhelming. I feel much less like I’m whining when I’m joking. And humor makes it easier to share with others.

I was diagnosed with severe OCD (and ADHD) when I was four years old, so I don’t really remember what it’s like to live without it. That’s right; my psychiatric history is now old enough to vote. That sort of makes it easier—it’s hard to miss normal when you’ve never known it. And I was fortunate enough to have what many people don’t: access to superb mental health services, and a mother who recognized the symptoms when I started washing my hands until they bled and when I began edging around the pile of dirty clothes in the laundry room like I was afraid it would swallow me whole. Despite the severity of my obsessions and compulsions, I’ve been successful because of this support.

This sort of germophobia is what most people think of when they hear of OCD, but the symptoms of OCD vary greatly over time and from person to person. Some of my obsessions weren’t so easy to recognize as such—in kindergarten, I would spend story time straightening my socks, unable to get them in the exact position I wanted. I had to change my underwear multiple times a day because I was constantly convinced that it was wet. I remember going to Disney World a few months before I was diagnosed—my father walked around the amusement park with a bag full of little girls’ panties. (That would have been fun to explain to security: “No officer, I’m not a pervert; my daughter’s just crazy.”)

My parents have done so much to help me overcome my OCD. As I grew up, they encouraged me to be open with them about my struggles with mental illness . It was expected that I would share my problems and go to them for support. Outside the house, however, the message was clear: don’t talk about OCD. Don’t talk about mental illness. It’s weird; it makes people uncomfortable; it’s not socially acceptable. But I couldn’t have hidden my OCD if I tried, and, oh, I tried.

In middle school, as I hit puberty and my body chemistry changed, my medication stopped working. Entirely. My symptoms skyrocketed, but still I tried with everything I had to hide them. Some of my compulsions were easy to cover up. When I had to spin the dial of my combination lock four times before I could open my locker, I could pretend that I’d gotten my code wrong and had to try again. But it’s pretty noticeable when the girl sitting beside you in math class has to bang her chair against the ground eight times before she can sit down. (Particularly if she came in halfway through class because she was busy spinning her combination lock.) And there was no good excuse I could think of to cover that up. So I stopped trying.

I started talking about my OCD all the time, to explain my actions, to try to make people understand.

I started with my peers: tweens with no filter who had never seen a person beat her chest like Tarzan or hold up an entire line full of kids by stopping in the middle of the hallway to hop on one foot. They rudely demanded to know why I freaked out whenever I smudged ink across my paper or why I sometimes shook my head like a wet dog. I did my best to explain my disorder in simple terms that even a ten-year-old could understand. But at that age, my peers still lacked the emotional if not the general intelligence to understand my condition. (Tweens and sociopaths have that in common.) I decided: If they wanted me to shut up and sit down, I was gonna stand and shout from the mountaintops. Never let anyone tell you that spite is a poor motivator.

High school was better. I applied and was accepted to a writing program at Carver Center for Arts and Technology, where my peers were understanding and empathetic. My medication stabilized and I began cognitive behavioral therapy. I exchanged my more noticeable compulsions for subtler ones. I didn’t hide my symptoms, but I learned to control them for my own benefit. Part of controlling compulsions is acknowledging and accepting the consequences of not performing them: “If I don’t proofread my English paper a fifth time, the worst case scenario is that I miss a typo.” This sort of reasoning helps bring my obsessions into perspective—a few points off an essay for a typo is not the end of the world. I’ll survive.

The summer before I went to college, I went to see a specialist in tic disorders, who informed me that my specific type of OCD is called Tourettic OCD, which is basically Tourette’s Syndrome and OCD slammed into one diagnosis. The Tourette’s was not a new development. It had always been there, lurking in the shadow of my OCD. In medicine, comorbidity is the simultaneous existence of two or more disorders in a patient. For most people, it’s a word that means life just got a lot more complicated. But I was elated—this doctor had given me more words, new language, to describe my experiences. I learned to differentiate between compulsions and tics and went off to college with new strategies for handling my mental illnesses.

Despite this, my first semester was still like getting thrown into the deep end without floaties. OCD hates changes in routine. College meant roommates, living away from home, and sharing a bathroom with an entire hall of strangers. But there’s nothing quite like trial by fire, and after a few nervous breakdowns, I settled into a new routine and my symptoms abated. I went through the same ordeal just this past year after graduation—transition periods are always rough for me, but I get through them with a lot of lorazepam and a mantra of this, too, shall pass .

Cecelia, front-center, with her college fencing teammates.

I still have my daily challenges. The cough I developed during a recent bout of illness has stuck with me in the form of a tic. It takes me a long time to get ready in the morning when I have to check and recheck my backpack to make sure I have everything I need. The skin of my knuckles is rough and calloused from trying to crack them too often. I still spend way too much time worrying about climate change.

When someone asks me why I exhibit some strange behavior or another, or so much as casts a curious glance my way when they see me blinking sporadically, I talk them through my diagnosis. I tell them about my evolving understanding over the years as I gained more information and science progressed. Then I talk them through my ever-changing symptoms and my treatment. (I have been on, at various points in my life, Paxil, Zoloft, Luvox, Prozac, Buspar, Lexapro, Ativan, clonazepam, Concerta, Focalin, Adderall, Strattera, and Daytrana. My psychiatrist has also been trying to talk me into testing out antipsychotics for years). Most difficult to explain are the urges that cause my tics. There are really no words for it, but I imagine it’s similar to the feeling of thousands of ants crawling across your skin. What can you do but try to shake them off? I explain to curious parties how OCD can manifest differently in different people. And I make jokes about it. I refuse to be ashamed of my condition. In public, I don’t surreptitiously slip my medication past my lips between sips from my water bottle—I toss a Zoloft into the air, throw my head back, and see if I can catch it in my mouth. I don’t mean to brag, but my mouth-eye coordination is unparalleled.

I’ve come a long way from the terrified little girl who cowered around dirty laundry, as my psychiatrist frequently reminds me . “I’m so proud of you,” she told me just the other day. “Just a few years ago, you couldn’t touch the sink faucet in your own bathroom.”

“Yeah, and now look at me,” I said. “You know, I was at the mall earlier and I dropped part of my cookie on the floor, and I just picked it up and ate it.”

“That’s disgusting,” she said. “Don’t do that again.”

I am not my OCD, but my OCD has played an enormous role in shaping who I am. So I can’t talk about myself without talking about it, and I really like talking about myself. Talking about OCD got me into my first-choice school. Talking about it got me here, on SELF.com. And I hope talking about it can also do others a world of good.

When we talk about OCD, we raise awareness of mental illness. We disseminate information so that people can recognize their symptoms and get a diagnosis, get treatment, get help. We open doors for those who’ve always known that something is wrong with them, but who have never had the words to articulate it. We deepen understanding and reduce stigma among the general public. We increase the chances of getting funding for research that could lead to better treatments. And we make life a little easier for people like me.

For information on OCD and treatment options, visit the National Institute of Mental Health website .

This Video Shows How Some People With OCD Feel Everyday:

Photo Credit: Daniel Grizelj / Getty

SELF does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Any information published on this website or by this brand is not intended as a substitute for medical advice, and you should not take any action before consulting with a healthcare professional.

- Have your assignments done by seasoned writers. 24/7. Contact us:

- +1 (213) 221-0069

- [email protected]

How to Write A College Essay on OCD: Intro to Conclusion

Writing a College Essay on OCD

Mental illnesses are common. Over half of Americans are diagnosed with a mental disorder during their life. Mental illnesses are disorders that affect a person’s thinking, mood, feelings, and behavior.

The diseases may be occasional or chronic. They can affect the patient’s ability to relate to others and their daily functions.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is increasingly gaining recognition in recent years. As more people become aware of the psychological illness, the affected are increasingly inclined to seek care.

A person diagnosed with OCD is likely to find it challenging to cope with their symptoms and lead a regular life. It can be very challenging to Stop or cope with obsessive thinking and manage compulsion.

What is OCD

OCD is a mental health condition that affects people of all backgrounds and ages, including children and the elderly. It is characterized by unpleasant thoughts, anxieties, or obsessions that result in compulsions or repetitive activities.

Obsessions and compulsions create severe distress by interfering with daily activities.

When OCD develops, the person becomes trapped in a loop of obsessions and compulsions.

Obsessions are unwelcome, intrusive thoughts, ideas, or desires that cause severe distress.

Compulsions are acts that a person engages in to banish obsessions or reduce distress.

The person recognizes that their compulsions are absurd and unreasonable. Yet, they refuse to give up because they fear the repercussions.

How to Write a College Essay on OCD

Writing a college essay on OCD involves:

1. Starting with a Plan

The initial step in any essay should be to create a documented plan. Start formulating a plan as soon as you receive your OCD essay question and give it some attention.

2. Initiating your Research

After considering the question and establishing an initial approach, gather information and evidence.

3. Create a Point of Contention

Every good OCD essay has a strong and well-supported argument. Contention refers to your essay’s core topic or argument. It serves as both a response to the query and a focal point for your writing.

4. Outline your Essay

Start penning down a possible essay format once you have completed most of your research and have a strong argument. This doesn’t have to be complicated.

A simple outline will do.

5. Create a Captivating Introduction

The introduction is the pivot of your essay. It is also where you give an overview of your work. Have a short, confident, and punchy introduction.

It is essential because it is the reader’s initial experience with your writing. It is also your first answer to the question and explanation of your viewpoint.

6. Compose Complete Paragraphs

Write 100 to 200-word long paragraphs that are mini-essays in themselves. Avoid the mistake many students make of writing short, one- or two-line paragraphs.

7. Conclude with a Strong Statement

Restate or emphasize your essay’s main point in the last paragraph of your essay. Aim for a solid, polished, and smooth ending.

8. Cite and Reference your Sources

Use Citations or references to credible sources to back up the facts, ideas, and arguments in your essay. This is one of the ways to avoid plagiarism in your essay.

9. Proofread, Edit, and get Feedback

Proofread, edit, and redraft your essay, if necessary, before sending it for evaluation.

OCD is a well-researched subject. There aren’t a lot of new studies that you can include in your OCD essay. As a result, you can use the following plan to organize your OCD essay.

1st point in OCD essay

You can describe how OCD develops. According to scientists, psychological and biological variables are thought to induce OCD.

OCD Essay Point 2

Then, in your essay about OCD, discuss the disorder’s symptoms. Focus on Obsessions or intrusive thoughts, and compulsions. Compulsions are mental acts or compulsive behaviors that a person feels compelled to engage in owing to an obsession.

Usually, the practices help lessen or prevent pain due to an obsession. Common compulsions include:

- Repeated cleaning of household items

- Counting to a specific number repeatedly

- Seeking acceptance or reassurance all the time

- Putting items in a particular order or arrangement

- Checking switches, locks, or appliances regularly

- Ritualized or excessive hand washing, tooth brushing, showering, or toileting

OCD Essay Point 3

Finally, discuss OCD treatment options, including pharmacological, behavioral, and cognitive approaches. A patient can concentrate on learning to manage symptoms under the supervision of a skilled therapist and through behavioral therapy.

Explain that a person can learn to effectively manage symptoms and regain function in their lives if they are committed to this treatment.

If you find this method for writing an OCD essay to be too broad, your essay could narrow your focus on symptoms, for example. You can explain how obsessions influence a person in your OCD essay.

Also, you could discuss the typical items that people are obsessed with, the negative repercussions of compulsions, and so on.

Besides, you can interview someone with OCD to make your essay more informative and engaging. Remember that it takes up a lot of time in a person’s life and creates significant impairment.

Also, keep in mind that patients can get help irrespective of their ideas and behaviors or the severity of their symptoms.

Best Sources for Your References on OCD Essay

OCD-related organizations and resources include:

Mental Health America

International OCD Foundation

National Alliance on Mental Illness

Anxiety Disorders Association of America

National Institute on Mental Health. OCD

The American Psychiatric Association (APA)

The Top 100 Cited Articles on Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

OCD – MedlinePlus https://medlineplus.gov

OCD – NCBI https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov › books ›

9 Examples of OCD Essay Topics

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder essay topic examples include:

OCD In Children

Living with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

OCD- Psychiatric Disease

Research on Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

OCD: Causes and Treatment

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in The Aviator

Outline and Evaluate Psychological Explanations For OCD

Clinical Psychology OCD treatment and approaches

Outline and evaluate Two Biological Explanations for OCD

Other Info on OCD in School

Many people who do not have OCD also experience troubling thoughts or actions. However, these thoughts and habits rarely cause problems in everyday life.

OCD patients have persistent thoughts and strict habits. Failure to engage in the behaviors creates a lot of distress. Many people with OCD are aware or suspect that their obsessions are irrational or unreal.

Ignoring Compulsions can lead to severe manic episodes. Students with OCD may find it difficult to concentrate in class or finish projects.

They feel compelled to undertake routines such as hand washing, rewriting sentences, or reorganizing notes. Intrusive thoughts can be both distracting and disturbing to the learning process.

Others may believe they are, which is known as limited insight. People with OCD have a hard time disengaging from their obsessive thoughts or stopping their compulsive behaviors.

It persists even when they are aware that their obsessions are unrealistic. In the United States, OCD affects two to three percent of the population. It is slightly more prevalent in women than men.

Typically, OCD starts in infancy, adolescence, or early adulthood. The average age of onset is 19 years old. An OCD diagnosis requires obsessions and compulsions that last more than one hour a day.

These cause significant discomfort and interfere with work or social functioning.

Obsessions are recurring and persistent ideas, impulses, or pictures that elicit unpleasant emotions like worry or revulsion. Many people with OCD are aware that their thoughts, impulses, or images are excessive or irrational.

However, logic and reasoning will not be able to alleviate the anguish caused by these unwanted thoughts. Most OCD patients try to distract themselves from the obsessions by performing compulsions, or suppressing or ignoring the obsessions.

James Lotta

Related posts.

Simple Ways on How to Write Your Essay Without Plagiarism

Writing Essay without Plagiarism: 9 ways to avoid plagiarism

what Respondus Records

Does Respondus Record you, Sound or Screen? Is it Safe?

writing Single-spaced Essay

Single Spaced Essay in Word: What it is, Meaning and Format

Overcoming OCD – The College Student’s Guide

This site is for you if you:

- Have been diagnosed with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Worry that you might have OCD

- Think you might be going crazy because of confusing fears and worries that won’t go away.

- Have strange intrusive thoughts you don’t understand and feel compelled to perform certain actions in response to these thoughts

You’re not alone, and there is an effective treatment for OCD — so you can look forward to relief from OCD and getting your life back.

You’re not alone. Approximately 1 in 40 U.S. adults has OCD. With Cognitive Behavior Therapy, relief can be just a couple of months away.

You’re Not Crazy

It’s normal to be concerned about your symptoms and maybe even a little afraid of what is happening to you. But you’re not “crazy” or any other label that makes you feel worse. OCD is a fairly common disorder that is neurobiological in nature. Researchers have found that certain areas of the brain work differently in individuals who have OCD compared to those who don’t. There is absolutely no reason to be ashamed of having this disorder, but it’s important that you understand it and learn how to control it. With effective treatment, you should be able to do whatever you want in life and be whatever you want to be.

What Exactly IS OCD?

OCD is a disorder that has a neurobiological basis. It interferes with how the brain functions, and its effects can actually be seen on brain scans. With OCD, a person has two specific symptoms:

Obsessions — disturbing, recurring thoughts, fears, doubts or urges that won’t go away. It’s as if your brain got stuck in the “worry” position and can’t restart.

Compulsions — repetitive actions, or “rituals,” that you feel compelled to do to feel better. These actions can be done overtly, like washing your hands, or covertly, like saying mental prayers. Unfortunately, you feel better only temporarily. The more you perform the compulsions, the stronger and more frequent the obsessions become.

Learn more about OCD and its symptoms

You’re Not Alone

When you consider that one in 40 adults and one in 100 children has OCD, it’s obvious that you are certainly not alone. This is a fairly common disorder and it is treatable. OCD sufferers come from every age group, race, ethnicity and socioeconomic background.

Why Haven’t I Heard of OCD Before Now?

OCD isn’t a new disorder, but it was not well understood — and little was published about its symptoms and treatment — until the past few decades. Even today, not all physiciians, psychologists, educators or campus administrators recognize OCD when they see it.

Learn more about the rise in awareness today.

What is the Treatment for OCD? How Fast Does It Work?

Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT), sometimes accompanied by medication, is the gold standard treatment for OCD. It is recommended by nationally- recognized institutions such as the Mayo Clinic and Harvard Medical School. Some studies show that more than 85% of people who complete a course of CBT experience significant relief from OCD symptoms. Relief can be just a couple of months away.

In some ways, OCD is like other health conditions such as asthma, allergies or diabetes. When properly treated, these chronic conditions are manageable, and are actually managed by millions of people around you. Like these other conditions, OCD requires a commitment to treatment. While there is currently no cure for OCD, CBT can help you get better and teach you how to keep your OCD under control.

Learn more about CBT.

What About Medication? Can’t I Just Take Some Pills?

Today’s easy answer for just about everything seems to be to take a pill. But for OCD, medication alone isn’t the best treatment.

Find out why CBT is the clear treatment recommendation.

Why is OCD happening to me now?

Illness can happen at any time, and college life is a stressful time that can be vastly different from your pre-college life at home. In fact, it’s not unusual to first have OCD symptoms at college. Read more about why college can “trigger” OCD.

Could My Symptoms Be Some Other Mental Disorder?

A number of conditions frequently co-exist, or “partner” with OCD. Disorders that can occur with OCD – referred to as “comorbid” disorders – include depression, bipolar disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism, tic disorders (including Tourette Syndrome), eating disorders and anxiety disorders. And there are several other disorders related to OCD that may also be comorbid with OCD. As a result, it can be confusing to try to sort out what your particular symptoms actually are.

Learn more about related conditions and disorders of the “OCD Spectrum”.

What’s Wrong With Doing My Compulsions? It Makes Me Feel Better.

Continuing to perform rituals in response to your obsessions can actually make your OCD worse.

Learn more about why you need to overcome OCD through treatment.

Where Can I Go For Help?

Start with your college or university’s student health center or counseling service. Tell them you think you might have OCD and want to see a cognitive behavior therapist. If your counseling center doesn’t have a cognitive behavior therapist on board, ask them to help you find one. If the staff doesn’t have information about cognitive behavior therapists for OCD, you can contact Beyond OCD to discuss therapy options for OCD. Your goal is to get relief from OCD as soon as possible.

Can a Support Group Help Me?

A support group can provide information, encouragement and emotional support for people who have OCD. It can play a very important role in OCD recovery, but it’s not a substitute for treatment.

Learn more about support groups.

When Money Is A Problem

If your student health center or counseling service is able to provide Cognitive Behavior Therapy, it may be covered under your student health insurance. If you need to go to a cognitive behavior therapist in private practice, it could be more costly. When money is an issue, it can present challenges to getting OCD treatment, but don’t give up.

Learn more about finding financial help.

Frequently Asked Questions about OCD and Its Treatment

Of course you have questions about OCD. Here are some of the most frequently asked questions by college students:

- What causes OCD?

- Is OCD inherited? Can stress cause OCD?

- Why can’t a person just stop their OCD?

- Is there an online test I can take to see if I have OCD?

- What’s the best treatment for OCD?

- Can you guarantee I’ll get better with treatment?

- Do I have to be hospitalized to treat my OCD?

- What if I don’t get treatment for my OCD?

- My college “doesn’t treat OCD”. Now What Can I Do? Should I change schools to get OCD treatment?

- What are my options if my school offers CBT but limits the number of visits?

- Should I take a leave of absence to get treatment?

- Are there accommodations available through disabilities services?

- Should I tell my family I have OCD?

- What Is OCD?

- Cognitive Behavior Therapy

Dealing with OCD in College

Stephen Smith, founder of nOCD, first had the idea to make a treatment app for people with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) after experiencing intrusive thoughts for the first time during college. OCD was taking over his life, but he couldn’t find effective or affordable treatment on campus, forcing him to withdraw from school while he pursued therapy. It’s fairly typical for OCD symptoms to surface for the first time between the ages of 21 and 25, sometimes triggered by periods of increased stress and responsibility. For Stephen and many others, college living provides the perfect storm of factors for OCD to rear its ugly head.

On-campus counseling centers are a great resource for many students who experience mental health problems during college, but for students with OCD, they might miss the mark. OCD is a chronic disorder in which recurring thoughts, urges, or images (obsessions) trigger anxiety, decreased temporarily by rituals or behaviors (compulsions) that actually serve to reinforce obsessions over time. It can be debilitating, but effective treatment does exist. The accepted standard is a combination of medication and exposure response prevention (ERP), in which a therapist works with a patient to expose him or her to anxiety-triggering thoughts or images while tolerating distress without the help of an OCD ritual. Despite the prevalence of the disorder – approximately 1 in 40 people worldwide meet the criteria – there are very few therapists trained in ERP. Those who do specialize in OCD typically have no shortage of clients, and rarely accept insurance. Finding OCD treatment anywhere is hard; finding OCD treatment at college can be impossible.

Technological solutions like nOCD can be an especially good option for college students:. young people, who tend to be tech savvy and excited about innovation might benefit from customizable ERP exercises, automatic tracking, and a social network of other real people with OCD. Below are some common problems faced by college students struggling to feel better, and how a tool like nOCD may help.

Between studying for exams, showing up to practice, and going to parties, how do I make time for ERP? By the time I get home, I’m exhausted, and purposefully triggering my anxiety is the last thing I want to do. ERP is challenging and exhausting – just like OCD. But even a few minutes of ERP per day will contribute to recovery, while sending a powerful message to OCD that you’re working to regain control over its unwelcome presence. Traditionally, ERP took place in weekly sessions in a therapist’s office. But research suggests treatment is more effective when delivered through a variety of planned and unplanned exposures that are built into daily activities. For example, if a student suffers from harm OCD, and fears she’ll lose control and hurt someone while holding a sharp object, she might build her exposures into the meals she’s already attending in the dining hall, purposefully triggering her anxiety and delaying the accompanying ritual by holding a butter knife at breakfast or a steak knife at dinner. Using an app to help build ERP into her daily life and track progress means she doesn’t have to set aside free time she probably doesn’t have to start to feel better.