Being Latina and the struggle of the dualities of two worlds

Reflections on why our identities can help create a better world for all of us.

A few days ago, I attended a Zoom presentation organized by ASUN entitled “What does it mean to be Latinx?” Every time I witness the complexity of identities in the Latinx community in the United States, I am amazed. Amazed that we are always perceived as a homogenous group, when in reality, we couldn’t come from more different backgrounds, and we couldn’t have more different and complex identities. Also, the challenges we face are as different as each of our stories. So, in the spirit of Hispanic Heritage Month, please indulge me in letting me tell you my story.

There is a well-known character in Mexican history that invokes both love and condemnation from most Mexicans. Her name was Malintzin but history knows her as La Malinche . Her story is similar to that of U.S.A.’s Pocahontas ; the beautiful indigenous woman who abandons her tribe to help the white man. (The legends omit how she became the property of such White men, but that’s another story).

La Malinche was a Nahúatl woman who was given to Hernán Cortés as a slave. Due to her upperclass education, she spoke two languages, an ability that made her very useful to Hernán Cortés in communicating with the indigenous people as he went about conquering Mexico. On one hand, she was intelligent and, clearly, resilient. But on the other hand, she helped Cortés begin the Spanish colonization of the Nuevo Mundo. This duality is what gives her such a complex identity. And this duality is one that follows me.

When I was in high school, several of my classmates would sometimes call me Malinchista . As you can imagine, that was NOT a compliment. By definition, a Malinchista is “a person who denies her own cultural heritage by preferring foreign cultural expressions” (I’m not making it up; look it up).

In my early teens, I discovered American football. While switching channels on the television, I stumbled across a game being played in several feet of snow. I had never seen this! The game was being played in Minnesota. That year, the Dallas Cowboys won the Super Bowl, and I became a die-hard fan of Roger Staubach and “America’s Team.” This marked the initiation of my love for all things American. I learned about Formula 1, Sports Illustrated and Tiger Beat. Yes, Tiger Beat introduced me to the American darlings of my generation. My bedroom walls were covered with pictures of American teen idols I had never seen before in my life (in the 1970s, Mexican TV programming didn’t broadcast many American TV shows; I only remember Dallas and The Partridge Family , which of course, I loved).

I also loved English-language songs. I used to spend my money buying cancioneros , books similar in format and quality to comic books, for people who were learning to play the guitar. The cancioneros had the lyrics of the songs along with the music notes. I literally used these cancioneros to practice my English. I would translate each word of the songs, and then I would play the records over and over until I memorized the lyrics and could actually follow the singer pronouncing the words. Do you know how hard it is to sing at full speed: “Now they know how many holes it takes to fill the Albert Hall?”

By the time I was in college, I had already spent time in the city of Dallas (and yes, I made the pilgrimage to Irving, Texas and the Cowboys’ stadium) – and perfected my English. I started studying English when I entered first grade. By middle school, my parents were paying a private tutor. In Mexico, English was accepted as the lingua franca needed to succeed in the world, and my parents were going to make sure I learned it. (My dad had taught himself English, and he shared my enthusiasm for English language magazines, although not for the Dallas Cowboys.) Learning a second language allowed me to learn about, navigate and integrate into a different culture. And, unlike La Malinche , I did this of my own volition.

When I made the decision to come to the United States to study, my father told me, “If you ever decide this is not for you or things don’t work out, come back home.” But I was not turning back. In my mind, America was the best place in the whole world (my small world, at least). I had spent a semester in an exchange program at the University of Oklahoma, and I knew back then I belonged in the United States. One of the things that caught my attention early on was the fact that people could wear their pajamas to class (I know you’ve seen it), and nobody blinked an eye. One could wear her hair in blue spikes or wear slippers to the grocery store, and no one would say a thing. To me, that was amazing! People didn’t bother you, judge you or care what you wore. I felt America was the place where not only public services worked, but where you could be yourself and you could be free to be whomever you wanted to be. There was a sense of freedom that was refreshing.

However, for a long time I felt like I didn’t belong here, and I didn’t belong in Mexico, either. Navigating two worlds was not precisely difficult but sometimes unsettling . You spend your time “live switching” from English to Spanish to Spanglish and back again. You mix Cholula with Five Guys hamburgers. You watch American soccer but listen to the Mexican commentators (otherwise it’s like listening to golf announcers). And you truly think Mexican soccer fans are like the old Oakland Raiders fans, only worse. Women in Mexico are as rabid fans as many men, but, at least back in my day (I feel ancient now), you didn’t see many women go to the stadiums. As a woman, I never felt safe. I only went to a match if my male friends went with me. This is one of the most striking differences between the U.S. and Mexico: American soccer fans are so mild-mannered in comparison!

Another striking difference I noticed when I first came to the U.S. was that I was not getting cat calls out when I was out walking in the streets. In Mexico, everywhere I went (since I was a preteen, for goodness’ sake), I would be subjected to cat calls and whistles – and the harassment only got worse the older I got. My experience as a woman was of always being on high alert. But when I came to the U.S., I felt respected. I could exist without being harassed continually. Women here seemed to have a voice and the same opportunities as men to grow and pursue their dreams. I felt free to pursue a career and to not be expected to only dream of marrying and having children. Although, over the years, I’ve come to realize there still is much room for improvement.

Back in the 1500s La Malinche did what she could to survive (did I say historians think she died before she was 30?). History asked her to do a task she didn’t want, and she did her best. I am sure she considered her options and bought time, respect and the right to live in the best way she could. She used her skills to earn a place in history, and although her role continues to be debated, I cannot blame her. Did I turn my back on my country? Or did I look for a better life? My circle of Latina friends in the U.S. is full of intelligent, professional women who left their countries and built a better life – a different life – here in the United States. They all miss their families, and they all support their biological families in many ways. What they can do from here, however, is more than they could have done had they stayed in their countries of origin.

Being Latina in America is both an honor and a challenge. We struggle with the dualities of our worlds. We struggle with the adjectives that define us. We are a complex mix of races, traditions and experiences. We care for our people, and we work tirelessly to do what must be done to help each other. The complexity of our identities can help us create a better world for all of us, a world where our differences are not viewed as a threat but as an asset. A world where we all thrive. ¡Sí, se puede!

By: Claudia Ortega-Lukas Graphic Designer & Communications Professional

Optimism Series Domestic Mining Green Opportunities

Nevada Gold Mines Professor Pengbo Chu in the Department of Mining and Metallurgical Engineering sees domestic mining as a way to change the mining industry into a green industry

Art 100 student stickers

The artwork is displayed throughout campus and was created using equipment from the DeLaMare Science and Engineering Library (DLM) Makerspace and Art Department’s Fablab

Optimism Series curb the effects of climate change

Associate Professor Julie Loisel in the Department of Geography outlines some of the solutions we can implement to aid in the global fight against climate change

Investing in women's health

Global researcher and advocate for the improvement of child and maternal nutrition, Angeline Jeyakumar, discusses iron deficiency, a common issue in women's health, for National Women's Health Month

Editor's Picks

AsPIre working group provides community, networking for Asian, Pacific Islander faculty and staff

University confers more than 3,000 degrees during spring commencement ceremonies

Father and son set to receive doctoral degrees May 17

Strong advisory board supports new Supply Chain and Transportation Management program in College of Business

Nevada Today

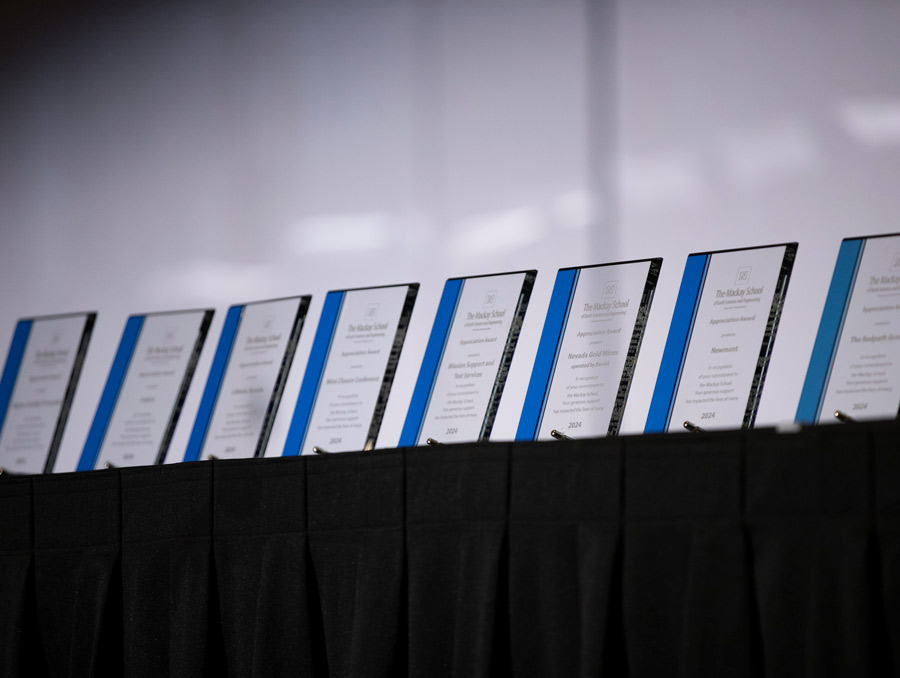

Mackay School celebrates another year of excellence

The annual John W. Mackay Banquet took place on April 26

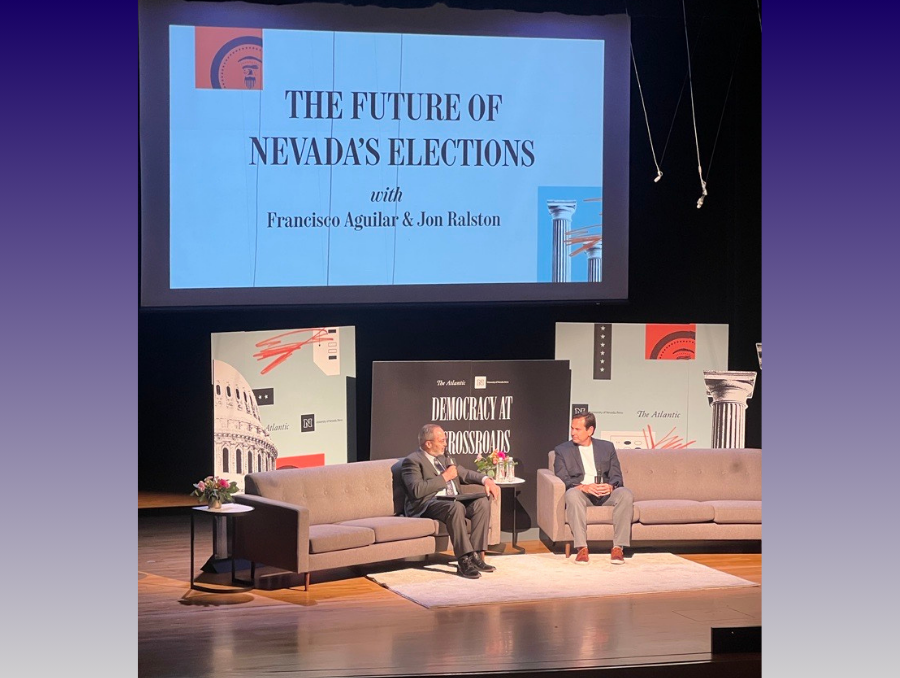

Publication 'The Atlantic' gifts complimentary access to University community

Following the ‘Democracy at a Crossroads’ event, students, faculty and staff can access the publication through the University Libraries

Visit Lake Tahoe on May 30 to learn about “The Promise of Chemical Ecology”

Neurodegenerative disease prevention, “blue zones” and environmental conservation to be discussed at the Hitchcock Center for Chemical Ecology keynote presentation

Reynolds School of Journalism looks back at the spring 2024 semester

Dean Yun recaps the highlights of the semester in the semester in review video

Co-chair of AsPIre Cydney Giroux discusses the group, why she finds it important and plans for the future

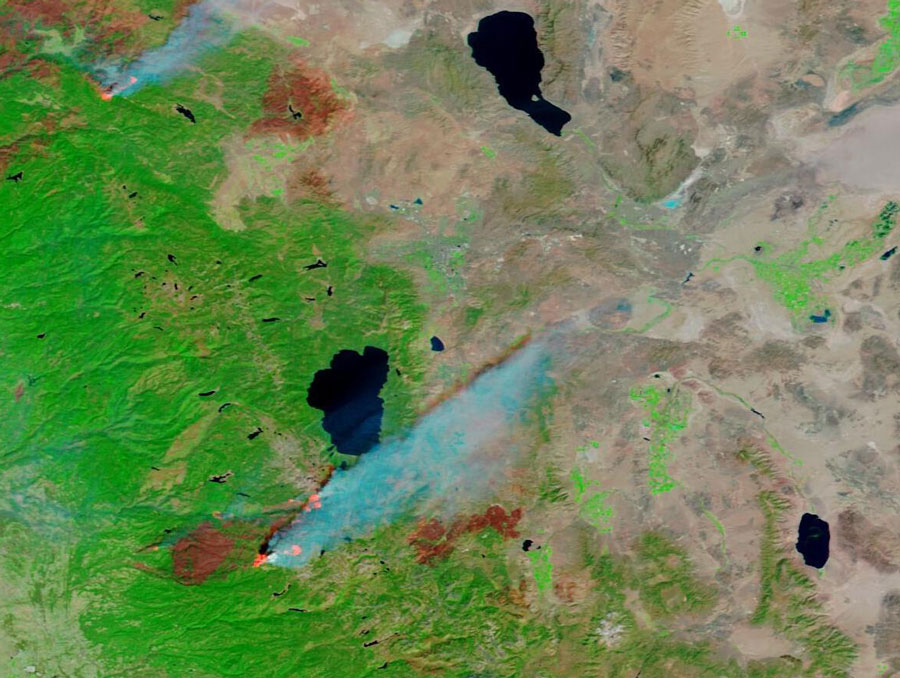

Lake Tahoe Wildfire Summit explores interdisciplinary solutions

University of Nevada, Reno researchers and scholars share their expertise and collaborate on potential wildfire management solutions

Grads Of The Pack: Emily Thao-Singh

Thao-Singh graduated from the School of Public Health and gave a speech at the Asian Pacific Islander Affinity Graduation Ceremony

Medical School class of 2024 commencement celebrates overcoming COVID-19 challenges

The University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine graduated 69 new doctors

- Accessibility & Inclusivity

- Breaking News

- International

- Clubs & Orgs

- Humans of SB

- In Memoriam

- Santa Barbara

- Top Features

- Arts & Culture

- Film & TV

- Local Artists

- Local Musicians

- Student Art

- Theater & Dance

- Top A&E

- App Reviews

- Environment

- Nature of UCSB

- Nature of IV

- Top Science & Tech

- Campus Comment

- Letters to the Editor

- Meet Your Neighbor

- Top Opinions

- Illustrations

- Editorial Board

Earth Day Isla Vista – Celebrating Through Music, Nature, and Fun

In photos: men’s basketball: gauchos vs uc davis, art as a weapon against invasion – film reminds us of…, opportunity for all uc office of the president yet to make…, the top boba places in isla vista – a journey into…, getting kozy: isla vista’s newest coffee shop, a call for natural sustainability: the story and mission of the…, tasa night market 2023: fostering community and featuring budding clubs at…, in photos – daedalum luminarium, an art installation, creating characters we love: the screenwriting process in our flag means…, indigo de souza and the best-case anticlimax, a spectrum of songs: ucsb’s college of creative studies set to…, nature in i.v. – black mold, southern california is in super bloom, from love to likes: social media’s role in relationships, the gloom continues: a gray may, the rise of ai girlfriends: connecting with desires and discussing controversy,…, letter to the editor: dining hall laborers have had enough, do…, is studying abroad worth it for a ucsb student, workers at ucsb spotlight: being a writing tutor for clas, the immense struggles of first-generation latino college students.

Edward Colmenares

Editor-in-Chief

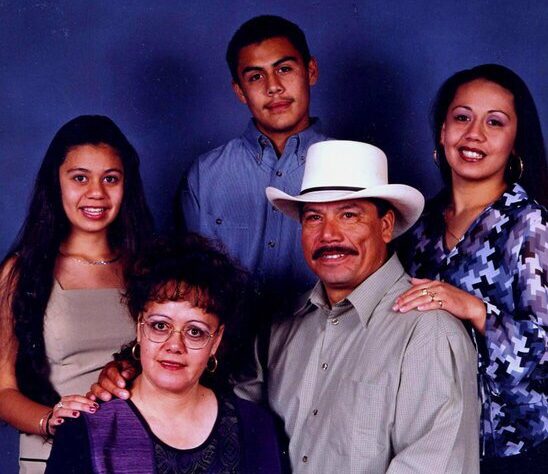

Imagine being tasked with setting the precedent of success for your entire family at 17 years old. No matter the personal cost, it is now your responsibility to lift your family out of poverty. This is the crucial promise many first-generation Latine college students make when they head off to higher education. Once they reach college, however, these students only uncover a disheartening reality. They were set up to fail from the start.

Stricken with discouragement when comparing childhoods with their wealthier peers, these first-generation Latine students recognize that university was not intended for them. Since the inception of higher education institutions, and up until a couple of generations ago, there was no reasonable path for these students to even attend university, and the few lucky enough to enroll could only do so under the demeaning conditions of systematic racism.

From K-12, Latine students are at a disadvantage. Born to immigrant, working-class parents, Latine children begin their educational journey with a lack of socioeconomic privileges that their peers have become accustomed to by pre-school. Often, neither parent in the household speaks English fluently enough to teach their child(ren) the language. Spanish is all these kids know, as they suddenly enter an environment where they will be excluded because of the simple fact that they speak a different language that isn’t English. Thus, a striking 82 percent of all students K-12 situated in California English language learning programs are Latine.

Any English learned at school then becomes a tool for the parents and family as these students commonly become a resource for translating, whether spoken in a movie or present in billing letters. It is important to note that a large portion of Latine parents did not make it past high school due to a lack of educational resources in their home country, so it is particularly difficult for them to learn English upon reaching the U.S.

Many Latine children are familiar with poverty. Representing 17 percent of the American workforce , Latine families are actively working to improve the lives of their children but can commonly only do so through exhausting manual labor. In agricultural, construction, or housekeeping occupations, the Latine population composes over half or close to half of the labor force . However, the unreliability and unlivable wages of these jobs severely limits the financial capacities of these working families.

As a result, Latine children in California K-12 schools account for 71 percent of all economically disadvantaged students and 73 percent of all homeless students. Considering that these same Latine children make up over one-half of all California students, it is an unfortunate reality that poverty strikes these children at disproportionately high rates.

When looking at Latine high school seniors graduating and potentially enrolling in the University of California (UC) or California State University (CSU) system, only 44 percent would even be eligible to apply. In order to qualify for either of these public institutions, a series of A-G courses must first be completed in high school, but the low-income school districts where these students are from are not sufficiently informing or preparing them for the admission requirements of higher education.

Getting into a four-year university is simply not a possibility for a majority of first-generation Latine. Out of 1,391,503 Latine undergraduates in California, 72 percent enroll in community colleges optimistically planning to transfer after two years. However, after six years, only about a third of these students actually end up enrolling in four-year colleges or universities while the rest drop out or postpone their education indefinitely.

The good news is that Latine students who are lucky enough to attend a major California four-year institution do tend to be first-generation. In both the UC and CSU system three out of four Latino students are the first in their family to reach higher education, which is over double that of other races. This luck has a limit though, as these students will face certain struggles the rest of the student body does not.

First and foremost comes the stress of paying for higher education, and Latine communities are granted less state and federal financial aid when compared to other races. Furthermore, expected contributions from parents and family members are significantly lower. On average, families of Latine students are expected to pay $5,911, compared to $13,319 for white families .

To make up for a lack of family funds, a majority of Latine students find employment to cover tuition and the cost of living. At the expense of academic performance and social participation, about 32 percent of all employed Latine students are working full-time with the rest being employed part-time. It is discouraging that so many of these Latine students must work long hours while trying to maintain a reasonable commitment to school, and this stress contributes to higher dropout rates.

Each year, the amount of Latine students entering higher education rises, so it’s not all bad news. However, proportional to the number of other races, Latine are at a severe disadvantage on all academic grounds, especially those who desire to be the first in their families to attend college. Without proper accommodations and consideration, beginning from grade school, Latine students will commonly find themselves unable to reach any adequate mantle of success for their families and will continue in poverty.

- Science & Tech

About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets and Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Services

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

- Priorities for the GSB's Future

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Business Transformation

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships and Prizes

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

Error message

“what does being hispanic mean to you”.

Members of the Hispanic Business Student Association share personal thoughts on their heritage and how it informs who they are and how they lead.

October 01, 2020

The Hispanic Business Student Association is a community of students interested in the cultural and professional issues that affect the Latino community. | Illustrations by Laura Pichardo

“For me, being Hispanic means standing on our ancestors’ shoulders to transform spaces not created for us and witnessing my parents’ sacrifices in pursuit of a better life — all while indulging in Mariachi music,” says Valeria Martinez, MBA ’21.

Hispanic Heritage Month begins each year on September 15 — the anniversary of independence for Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. Mexico and Chile celebrate their independence days on September 16 and September 18. To mark this year’s celebration, members of Stanford GSB’s Hispanic Business Student Association answer the question, “What does being Hispanic mean to you?”

— Jenny Luna

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom .

Explore More

Interim gsb dean named as search process begins.

Changemakers: Teaching Young People a Recipe for Success in the Restaurant Industry

Stanford GSB Professor Neil Malhotra Named Carnegie Fellow

MBA Program The Stanford MBA Program is a full-time, two-year general management program that helps you develop your vision and the skills to achieve it.

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Get Involved

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- Career Advancement

- Career Change

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- Information for Recommenders

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- After You’re Admitted

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- Videos, Code & Data

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Marketing Camp

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Reading Materials

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

- Founding Donors

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Program Contacts

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- Join a Board

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Social Impact

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Hispanic — Hispanic And Hispanic Culture

Hispanic and Hispanic Culture

- Categories: Hispanic

About this sample

Words: 763 |

Published: Mar 14, 2024

Words: 763 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1619 words

1 pages / 1139 words

2 pages / 1071 words

2 pages / 823 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Hispanic

Black African Americans and Hispanic/Latinos are two distinct cultural groups with rich histories and unique identities. Understanding the historical, cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic factors that shape these communities [...]

Do people already assume you speak Spanish because you are of Hispanic descent? Do they judge when they find out you don't? If you don’t understand your culture would that make you any less of a member to your ethnic group. [...]

Bartolome de las Casas once stated, “Upon this herd of gentle sheep, the Spaniards descended like starving wolves and tigers and lions. ” Las Casas believed that Natives were peaceful and non-deserving of the torment and [...]

Introduction to the Quinceañera celebration in Spanish culture Definition of Quinceañera and its cultural significance Exploration of the origins of Quinceañeras Evolution of the celebration from pre-Hispanic [...]

The idea of American dream is deeply stuck in the American people’s minds. American people strongly believe that if they had work hard enough, one day they will reach the American dream and become successful, even when people [...]

We always wonder why bad things happen, maybe the answer is right in front of us but we’re just too blind or na?ve to see it. Most would like to think that all people know the difference between right and wrong. The problem is [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Forgotten password

Please enter the email address that you use to login to TeenInk.com, and we'll email you instructions to reset your password.

- Poetry All Poetry Free Verse Song Lyrics Sonnet Haiku Limerick Ballad

- Fiction All Fiction Action-Adventure Fan Fiction Historical Fiction Realistic Fiction Romance Sci-fi/Fantasy Scripts & Plays Thriller/Mystery All Novels Action-Adventure Fan Fiction Historical Fiction Realistic Fiction Romance Sci-fi/Fantasy Thriller/Mystery Other

- Nonfiction All Nonfiction Bullying Books Academic Author Interviews Celebrity interviews College Articles College Essays Educator of the Year Heroes Interviews Memoir Personal Experience Sports Travel & Culture All Opinions Bullying Current Events / Politics Discrimination Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking Entertainment / Celebrities Environment Love / Relationships Movies / Music / TV Pop Culture / Trends School / College Social Issues / Civics Spirituality / Religion Sports / Hobbies All Hot Topics Bullying Community Service Environment Health Letters to the Editor Pride & Prejudice What Matters

- Reviews All Reviews Hot New Books Book Reviews Music Reviews Movie Reviews TV Show Reviews Video Game Reviews Summer Program Reviews College Reviews

- Art/Photo Art Photo Videos

- Summer Guide Program Links Program Reviews

- College Guide College Links College Reviews College Essays College Articles

Summer Guide

- College Guide

- Song Lyrics

All Fiction

- Action-Adventure

- Fan Fiction

- Historical Fiction

- Realistic Fiction

- Sci-fi/Fantasy

- Scripts & Plays

- Thriller/Mystery

All Nonfiction

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Personal Experience

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Community Service

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

All Reviews

- Hot New Books

- Book Reviews

- Music Reviews

- Movie Reviews

- TV Show Reviews

- Video Game Reviews

Summer Program Reviews

- College Reviews

- Writers Workshop

- Regular Forums

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- College Links

I was born Hispanic

Describe any experience of cultural difference, positive or negative, you have had or observed. What did you learn from it? “My girlfriend…you know the tall brunette, well she swore he was just a friend… but when…” “Be quiet, Matt. I’m trying to teach.” Quivering with impatience, the words had absolutely no effect. “No! Hold on…I’m not finished yet.” Returning to his tragic love story, Matt faced me and the rest of the table, his loyal listeners. Yet again the teacher interrupts. “Matt do we have a problem?” It was more of a threatening command than a concerned questioned. Annoyed, he replies, “Yeah we do. You won’t let me finish.” “Come see me after school.” There wasn’t a day when the teacher wasn’t disrespected, talked back to, and simply ignored. This was expected of the Hispanic students; the lack of respect for education, the expectation that they wouldn’t amount to much in school. But in Sophomore English those degraded values and flimsy ideas towards education and its impact was almost every kid’s mindset. Each student contributed graying attitudes and negligence that weaved a unique environment. A class culture that impacted me as much as my Hispanic culture did concerning what role education would play in my life. I never was exposed to people who valued education. Of course, I saw Caucasian kids who planned to go to college, but they were...well, they didn’t have an accent. They didn’t have immigrant parents who depending on me for translating. They weren’t expected to be pregnant at sixteen or jumped into a gang. None of it. They had parents who spoke English fluently and who paid them for their grades. They were expected to attend college. They were expected to fulfill the American Dream. Yet, in sophomore English, it didn’t really matter what race, background you were. Everyone there hated English. Despite this common ground, I stayed close to mis amigas. Within my comfort zone, I watched the blond girl sitting next to me bring vodka, usually on Mondays because she was still hung-over from the weekend. I wondered if I should say anything when I saw the homegurl toss marijuana out the class room window to the homeboy waiting outside. Education meant nothing to them at all. Despite being exposed to this, I didn’t perfectly assimilate like the ten other failing students did, but it affected what goals I had. I struggled even seeing myself at community college. At the end of the year, the teacher advised me to take AP Language and Composition as a junior. She also offered it to two of my friends. We agreed. Liars! My friends had dropped the class. Walking into AP English, I felt highlighted in that room. Further into that period, just the way these students talked and acted was already intimidatingly different from last year. They participated in class discussions. They did homework. They fretted about their grades. Most of them had taken Honors Sophomore English, the one where there weren’t hung-over students bringing vodka. They practice fierce academic vocabulary. Last year they just cussed hella. Isolated both ethnically and intellectually, I wanted to drop the class but stuck it out. This scholarly culture valued education, despite their financial or ethnic background, respected education as their sacred road to rewarding future. During group discussions, I found out that my different perspective as a Hispanic student could also contribute ideas or values or unearth details. Seeing fellow Hispanic students focus academically and succeed in an AP class culture helped me assimilate into obtaining an AP mindset where education is in the limelight. In my Hispanic peers, I watched unfolding success when society foretold failure. I was born Hispanic, but I wasn’t born into a failing stereotype. I embrace my roots, my different yet enlightening perspective, but I refuse to tolerate any limitations. I will guard my education, planting it in promising academic soil, an environment rich and diverse where I will be able to grow as I did in my AP Language and Literature class

Similar Articles

Join the discussion.

This article has 0 comments.

- Subscribe to Teen Ink magazine

- Submit to Teen Ink

- Find A College

- Find a Summer Program

Share this on

Send to a friend.

Thank you for sharing this page with a friend!

Tell my friends

Choose what to email.

Which of your works would you like to tell your friends about? (These links will automatically appear in your email.)

Send your email

Delete my account, we hate to see you go please note as per our terms and conditions, you agreed that all materials submitted become the property of teen ink. going forward, your work will remain on teenink.com submitted “by anonymous.”, delete this, change anonymous status, send us site feedback.

If you have a suggestion about this website or are experiencing a problem with it, or if you need to report abuse on the site, please let us know. We try to make TeenInk.com the best site it can be, and we take your feedback very seriously. Please note that while we value your input, we cannot respond to every message. Also, if you have a comment about a particular piece of work on this website, please go to the page where that work is displayed and post a comment on it. Thank you!

Pardon Our Dust

Teen Ink is currently undergoing repairs to our image server. In addition to being unable to display images, we cannot currently accept image submissions. All other parts of the website are functioning normally. Please check back to submit your art and photography and to enjoy work from teen artists around the world!

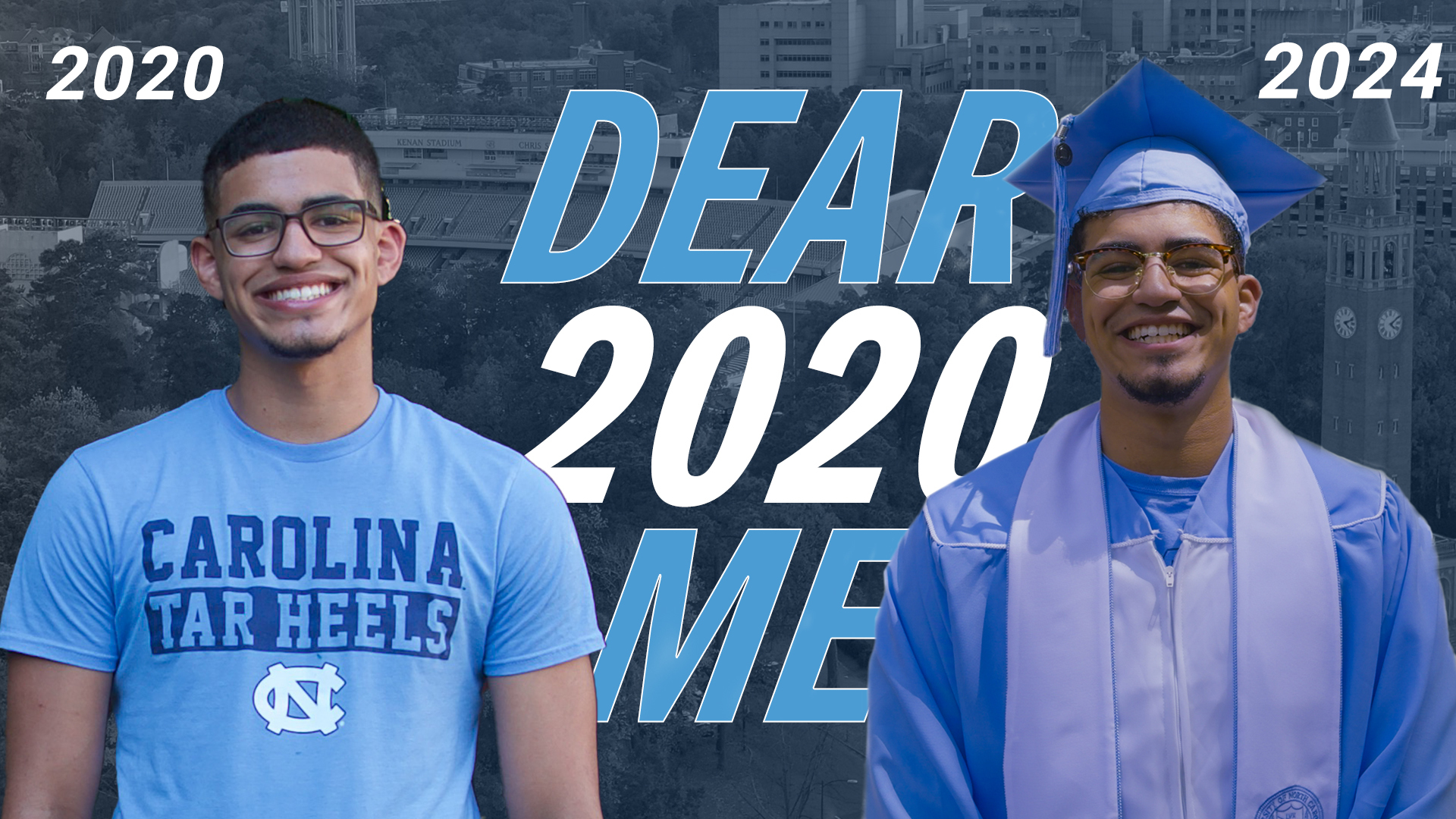

Latina first-generation college students draw on lessons, mentor others

ANAHEIM, Calif. — Noemi Rodriguez, 21, aspires to make an impact in her community through her work after college. But as she maneuvers through her final year at University of California, San Diego, balancing school, work and commuting has been an ongoing challenge.

"My mom had told me from the beginning, 'If you want to go to school, it’s going to be on your own account,'" said Rodriguez, who's worked part time at Jamba Juice while going to school full time and taking on a second job in the summer to help pay for tuition and cover some of the family’s bills.

Latinos are more likely to be first-generation college students than any other racial or ethnic group: More than 4 in 10 (44 percent) Hispanic students are the first in their family to attend college, according to educational nonprofit organization Excelencia in Education .

Monday was the annual National First-Generation College Celebration, marking the anniversary of the Higher Education Act of 1965, which greatly expanded college opportunities through financial assistance tools such as grants and work-study programs.

While the celebration is one day, many higher education institutions carry out weeklong and even monthlong celebrations.

In California, Hispanics make up 43 percent of public college undergraduates, according to a report by The Campaign for College Opportunity . The organization, composed of a coalition of groups, aims to boost opportunities for the state's Latinos to attend and graduate from college.

Latino college enrollment and degree obtainment are continuing to rise, and there have been encouraging trends in California, which has the country's largest Latino population, making up almost 4 in 10 (39 percent) Californians. A little over half (51 percent) of the state's Latinos are under 30.

The report noted that almost 9 in 10 (87 percent) of Latino 19-year-olds have a high school diploma or equivalent credential, compared to 73 percent 10 years ago. In the last five years, four-year graduation rates doubled for Hispanics enrolled as full-time, first-year students in the California State University system — from 9 percent to 18 percent for Latinos and from 15 percent to 29 percent for Latinas.

However, only 18 percent of Latino and 29 percent of Latina freshmen at the California State University system are graduating in four years.

Rodriguez is a success coach for the UCSD Student Success Coaching Program , which supports incoming and continuing first-generation students like her through mentoring, helping them balance school and work and giving them access to resources and support services. After graduation, she plans to continue mentoring students, drawing on her own experiences.

The first in her family to attend a four-year university, Rodriguez recalled dealing with impostor syndrome in high school before she was admitted to UCSD, a topic of discussion among many first-generation students.

"When I talked to other people outside of my school, they all did a lot better than me and had higher SAT scores, higher grades," Rodriguez, who is double majoring in political science and ethnic studies at UCSD, said. "Even though I know I did a lot, I didn't think that I was going to get in."

Daisy Gomez-Fuentes, 23, a graduate student at San Diego State University, works for the school's Latinx Resource Center as a peer mentor and graduate assistant.

She provides students with guidance by supporting them across coursework, answering questions they have about classes, advising them on how to ask for letters of recommendation and holding workshops regarding impostor syndrome and best practices to stay organized throughout the semester.

“As a first-gen, I’m paving the way for future generations by breaking cycles and barriers and essentially becoming a resource and a mentor to other first-gen students,” Gomez-Fuentes, who earned a bachelor’s degree earlier this year in Chicana/o/x studies from California State University, Fullerton, said.

She is planning to obtain a doctorate in sociology and become a professor. Under 6 percent of Latinas have a graduate degree, compared to 15 percent for white women.

'I see myself'

For Brenda Elizondo, 21, helping first-gen students is a full-circle moment.

Elizondo works in youth development services for the Boys and Girls Club of Garden Grove, helping many first-generation youths from low-income areas grow as students.

"For me, it really just means a lot because I was part of this program, as well," Elizondo, who's a full-time student at Cal State Fullerton, said.

She said participating in the program as a child helped distract her from troubles at home. There would be times when there wasn’t any food on the table, she said.

Now, as an adult, she juggles three jobs while being the sole caretaker for her mother, who is 42 living with several chronic conditions. As the eldest of her siblings, she also provides for her two younger brothers, who are 17 and 13.

“I do feel like it gets overwhelming,” Elizondo said. “There’s times that I feel like maybe this isn’t for me, maybe I should drop out.” But serving as an example for her brothers is what is motivating her to continue college, she said.

Having her mom and siblings watch her walk at graduation would feel “like crossing that line at a marathon,” Elizondo said. She said she expects to graduate in 2022 and is pursuing a career in journalism to tell stories about people in her community who she feels don’t have a platform.

The guidance Elizondo is providing at the Boys and Girls Club is a step to helping more Latino youth on the pathway to college.

"Being able to offer that support, whether it's emotional, anything, just for these kids, it means a lot," she said, "because when I see them, I see myself."

Follow NBC Latino on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram .

Edwin Flores reports and produces for NBC Latino and is based in Anaheim, California.

What do you think? Leave a respectful comment.

Kelly Field, The Hechinger Report Kelly Field, The Hechinger Report

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/education/more-hispanics-are-going-to-college-and-graduating-but-disparity-persists

More Hispanics are going to college and graduating, but disparity persists

SALEM, Mass. — When Elycea Almodovar was searching for a college three years ago, she had just two criteria: It had to be diverse, and it had to have a record of actually graduating students like her — not just taking their money and letting them drop out.

Salem State, the most diverse public university in her home state of Massachusetts, checked both boxes. Its student body was 8 percent Hispanic, and growing, and the graduation gap between its white and Hispanic students had narrowed at the time to less than two percentage points, well below the national average of 10 percentage points. The school was doing so much better than its peers that it was named a top 10 institution for Latino student success by The Education Trust , which advocates for low-income and racial minority college-going.

Almodovar, the daughter of Puerto Rican parents who moved to the mainland, was sold. She enrolled in the fall of 2015, and immediately felt at home, she recalled.

“I was like, ‘Yes, this is where I want to be,’” said Almodovar, who is now a junior.

As the Hispanic population in the United States has exploded, so has the number of Hispanics pursuing higher education. Between 2000 and 2015, the college-going rate among Hispanic high school graduates grew from 22 to 37 percent, according to the U.S. Department of Education . Hispanic undergraduate enrollment more than doubled, to 3 million. More than a quarter of young Hispanics — 28 percent — now have at least an associate degree, up from 15 percent in 2000.

This growth has compelled colleges including Salem State, whose student body went from 5 to 14 percent Hispanic over the past decade, to pay more attention to lingering achievement gaps between their white and Hispanic students. In pockets across the country, institutions are adding Latino leadership programs, hiring more diverse faculty and expanding their cultural programming.

To some extent, those efforts appear to be working. More than half of Hispanic students — 54 percent — now finish a bachelor’s degree within six years, up from 46 percent in 2002, the Education Department says .

That’s the good news: More Hispanics are going to college, and their graduation rates are rising.

Elycea Almodovar, a junior at Salem State University, right, walks on campus with her roommate, Sabrina Ornae, a junior. Almodovar was drawn to the school because of its diversity. Photo by Gretchen Ertl for The Hechinger Report

The bad news? This progress remains uneven. Nationwide, the proportion of Hispanics who graduate within six years is still 10 percentage points lower than the proportion of whites, according to the Education Department . The proportion who graduate in four is nearly 14 percentage points lower.

This disparity is leaving many Hispanics stuck in low- and middle-wage jobs, with profound implications for them in particular and the U.S. economy in general. Hispanics comprise the nation’s largest minority group, expected to make up 29 percent of the population by 2060, according to the Census Bureau . Already, one in every four elementary-school students is Hispanic, the U.S. Department of Education reports .

If the divide isn’t narrowed, there won’t be enough educated workers to fill the high-skilled jobs left vacant by retiring baby boomers and annual household incomes for all Americans would drop by 5 percent by 2060, according to research conducted at Rice University .

But eliminating longstanding achievement gaps isn’t easy, as Salem State has discovered.

Since Almodovar enrolled, the graduation gap there has re-opened, reaching as high as 11 percentage points. Racist and anti-immigrant graffiti has appeared on the campus baseball diamond and bike path. And some students have begun demanding that the administration do more to diversify a faculty that is far whiter than its student body.

In a campus climate survey , fewer than half of nonwhite students and faculty said they were “comfortable” at Salem State.

The college’s successes — and its setbacks — show how hard it can be to build an inclusive campus and eliminate racial achievement gaps, especially in a time of deep national divisions.

The stubborn gulf between white and Hispanic students is at least partly due to systemic disparities in education. Compared to their white peers, Hispanic students are less likely to attend preschool, and more likely to attend low-performing public primary and secondary schools with inexperienced teachers and high leadership turnover.

A weak academic foundation limits many Hispanics’ options for college. Nearly two-thirds end up in overcrowded and underfunded community colleges or second-tier public universities, while only 15 percent attend one of the 500 most selective colleges, where graduation rates are the highest, according to the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce .

Hispanic students are also disproportionately low-income and the first in their families to seek higher educations, characteristics that make them more likely to drop out.

A sign on the Salem State University campus was hung in response to racist graffiti. Photo by Gretchen Ertl for The Hechinger Report

“We’re determined to get all our students across the finish line in the same amount of time, but we’re not all at the same starting line,” said Andrew Hamilton, associate dean for student success at the University of Houston.

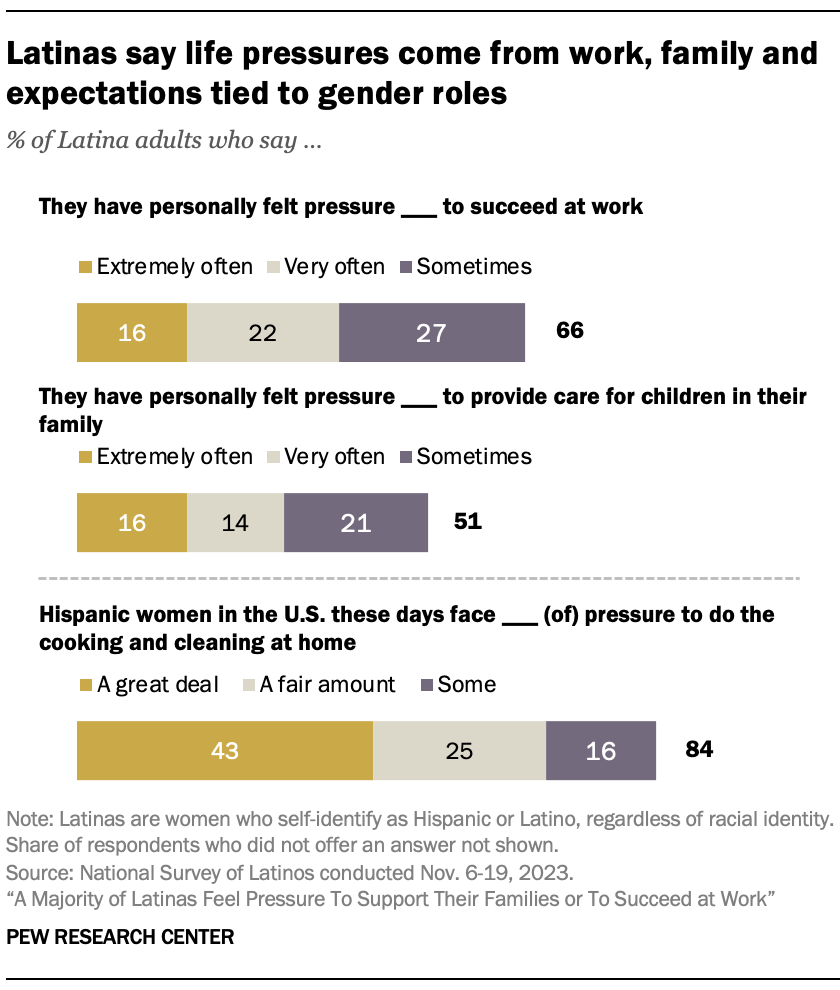

Cultural expectations can create additional hurdles. Hispanic men, socialized to be providers, may feel pressure to drop out and work to support their families. Women, raised to be caregivers, can find themselves “caught between two sets of demands”: their families’ and their professors’, said Jennifer Morton, an assistant professor of philosophy at the City College of New York, who grew up in Peru.

READ MORE: How failing to get more Hispanics to college could drag down all Americans’ income

But demographics are not destiny. What institutions do with the students they have matters deeply. Even institutions with similar student bodies can have dramatically different results.

Take Massachusetts state colleges. From 2013 to 2015, the achievement gap between white and Hispanic students at Salem State averaged 1.5 percentage points, according to The Education Trust, which compared Hispanic outcomes at various colleges. But at Fitchburg State, the gap averaged 14.8 percentage points, and at Worcester State, 11.7 percentage points. The three colleges enroll similar shares of low-income students with similar SAT scores.

“It’s difficult to provide a recipe for student success,” said Andrew Nichols, the author of the report. “So much is institution-specific.”

Still, he said, there are two things that seem to work for most colleges: enrolling a critical mass of Hispanic students and hiring diverse faculty.

Salem State has made progress on both fronts. As the Hispanic population in Salem and neighboring Lynn has grown, the college has added bilingual admissions counselors and translated its recruiting materials into Spanish. It’s begun offering information sessions for immigrant parents in Spanish and has set aside scholarships for Hispanic students.

Carlos Santiago, Massachusetts’ commissioner of higher education, said that native language outreach matters to Hispanic families.

“It says something about the importance of Latino students to that institution,” he said.

Another thing that helps: “Having leaders and faculty that look like them,” he said.

That’s been a bigger challenge for Salem State. Though the college doubled its number of full-time Hispanic faculty between 2012 and 2016, Hispanics still made up fewer than 5 percent of full-time faculty — 16 out of 349. That year, only six full-time professors were Hispanic women.

Almodovar says her professors have been “phenomenal,” but she wishes she’d had more than one nonwhite professor in her three years at Salem State. Her freshman year, she took an advanced Spanish class with “a white guy who learned it in college.”

“You learn better when you can relate to the professor,” she said.

The campus of Salem State University in Salem, Mass. Salem State, which went from 5 to 15 percent Hispanic over the past decade, is paying more attention to lagging graduation rates among its Hispanic students. Photo by Gretchen Ertl for The Hechinger Report

More diverse faculty and staff is at the top of a list of demands issued by a Salem State student movement called Black, Brown, and Proud, which has also appealed for faculty training in creating a “culturally responsive teaching environment.”

Meanwhile, some students have blasted the Board of Trustees for picking John Keenan, a white former state legislator with minimal experience in higher education, to be president of the college over Anny Morrobel-Sosa, a former provost and dean who was born in the Dominican Republic.

In his inaugural address in January, Keenan acknowledged that Salem State had work to do to become “as inclusive as we are diverse.”

Scott James, executive vice president, says the college is “committed to getting our employee population to mirror our student population.”

The challenge, he said, is that faculty turnover is slow, and “we’re chasing a student body that continues to get more diverse.”

But Guillermo Avila-Saavedra, the college’s faculty fellow for Latino student success, said students need to see themselves reflected in more than just the faculty. They need to see Hispanics represented in reading materials, building names and visiting speakers.

Avila-Saavedra is preparing a report that will ask the administration to name a room in the campus center after Cesar Chavez, the late co-founder of the National Farm Workers Association, and to create a hall of Latino alumni.

Such symbolism “goes a long way towards demonstrating an inclusive campus,” he said.

An historic seaport, Salem has long been a place that welcomes new immigrants – a socioeconomically diverse city with “sea captains’ mansions around the corner from tenement houses,” as Mayor Kimberley Driscoll, a Salem State alumna, put it.

Yet Salem, whose name is synonymous with the witch trials of the 1600s, is also a place with an ugly history of intolerance.

Lately, both sides have been showing, as residents wrestle over an ordinance that declared the city a “sanctuary” for undocumented immigrants.

Scott James, executive vice president of Salem State. James says the college is “committed to getting our employee population to mirror our student population.” Photo by Gretchen Ertl for The Hechinger Report

Those tensions have spilled over onto the Salem State campus. Last year, when Almodovar was a sophomore, a hacker posted a tweet on the university’s official Twitter account that read “We don’t need u immigrant thieves in our school.” Twice in her junior year, someone scrawled racist graffiti on campus, proclaiming “white power,” and “Whites Only USA.”

Some on campus believe the recent uptick in deportations of undocumented immigrants living in the U.S. and uncertainty around the future of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, program may be partly to blame for the college’s backsliding on retention. Over the past two years, the college’s six-year graduation rate for Hispanic full-time freshmen has fallen more than five percentage points, to 45 percent.

READ MORE: First-gen students at elite colleges go from lonely and overwhelmed to empowered and provoking change

For Hispanic students, “there’s a lot of anxiety around what happens next,” said Rebecca Comage, director of diversity and multicultural affairs. “It impacts not only their academic performance, but also their wellness and mental health.”

That uncertainty isn’t likely to disappear before Almodovar graduates, but Santiago believes Salem State, at least, may be approaching a “tipping point,” where pushback against the college’s growing diversity gives way to acceptance. He predicts it will occur when Hispanics make up a quarter of the student population.

“When I was a student, Latino students were ignored, we were such a small percentage of students,” he recalled. As the Hispanic student population grows, “you’re going to go from invisibility to pushback, to ultimately an acceptance.”

This story about Hispanic Progress in Higher Education was produced by The Hechinger Report , a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up here for Hechinger’s higher-education newsletter.

Kelly Field is a journalist based in Boston who has also reported for The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Support Provided By: Learn more

Educate your inbox

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

A mentoring program that aims to keep Latino males in school

Education Sep 13

- Personal Essay

For the White Latina Struggling With Her Identity — I've Been There, Too

:upscale()/2017/09/20/755/n/37139775/tmp_MIWro7_0669c47b935e633a_annie-gray-376025.jpg)

For most of my life, I would shrug off the fact that my parents left everything behind in their native land to ensure that their three kids could reach their potential — something that couldn't be achieved back home in Argentina. I didn't realize until recently that everything that I have and will achieve in life is due to them overcoming their fears of leaving our home and our family and diving headfirst into the unknown. I owe it to them – and to the ones still struggling with their Latino identity — to write this.

In my first school in the United States, my bilingual teacher asked me to speak to her. Anything at all. With the option to either speak in English or Spanish, I refused both. Angry at having to choose one or the other, at having to choose who I was, I didn't talk for two months. That was my first encounter of my confused identity.

I knew early on I didn't fit any specific mold. No one assumed that I spoke Spanish at school. My last name didn't have anything "Hispanic" about it. I didn't fit the stereotypical Latina label for my peers. My cousins would tell me that I had no choice but to think in English, being the "gringa" that I was. I didn't fit the stereotypical Argentinian label for them, and no matter how hard I tried, I didn't fit the stereotypical American label for myself. It was exhausting. But in my own house, surrounded by my supportive family, I knew what I was: I was a young immigrant. I was born in Argentina. But why didn't I feel as Argentinian as I should?

Being a white, blond, blue-eyed, Jewish Argentinian challenged everyone's views of what they thought a Latinx was. "How are you Hispanic AND Jewish? It's not possible!" I got this question way too many times. Since I moved to the United States at the age of 3, the American lifestyle was all that I knew. My older brothers had the connection to Argentina that, for the majority of my childhood, was nonexistent. While they had the slight accents to have others question their nationality, no one batted an eye when I spoke. While they had the middle school with a large Latino community, I had a white, private school. While they had the memories imprinted in their brains of what home was, I had only the stories I heard and easily forgot.

I remember when my family would make fun of my Spanish accent through our FaceTime calls; I felt betrayed by my own tongue. I remember when my parents' broken English would embarrass me. I struggled with being an Americanized Latina. I didn't know which side I wanted to embrace. Little did I know that I didn't have to choose just one; I could be both. But instead of trying to accept my ethnicity and my differences, I would do anything to avoid the whole Latina stereotype. The most diverse title I would have accepted in my preteen years would have been Jewish.

Looking back, I wish that I had gotten over the fact that we weren't your typical Brady Bunch family sooner. But I'm glad that I realized that I didn't care that we didn't fit any specific label. I got out of my sheltered bubble, and I appreciate it all in a way I never thought I could.

While I used to be embarrassed about something as minuscule as my parents' accents, I now realize how ridiculous that was. My dad works hour after hour as a doctor, even going to work in the middle of a Category 4 hurricane to help his patients. My mom donates not only her time and effort but also her whole heart to anyone in need. My two older brothers study and work their whole days but will do anything to brighten people's days. Despite the negative stigma and reputation that immigrants get repeatedly here, I know first-hand that it isn't the least bit true, and it won't ever tear down the pride I have for my family and my community.

I realized that my parents' accents didn't stop them from impacting the world, from impacting us. Their dedication — from learning a new language to working hard just to be able to spoil us and give us a better life – paved a path for me to follow. They taught me to embrace our differences, for they are the ones that make us who we are. They taught me to speak out for what I believe in. They taught me to stay humble, empathetic, and grateful.

While I learned to take pride in my roots, I still struggle with some of my identity today. My small but noticeable Spanish accent makes me stand out to my family. My common Argentinian name is still mocked at school. But that doesn't make me any less proud of who I am. I can't imagine a life without the support of my loud, loving, Hispanic family, a life without blasting our favorite Spanish music, a life without showing our whole city who we are — Latinos. And am I proud to be one.

5 Practices to Better Serve Latino College Students

What i’ve learned in my 15 years in higher education.

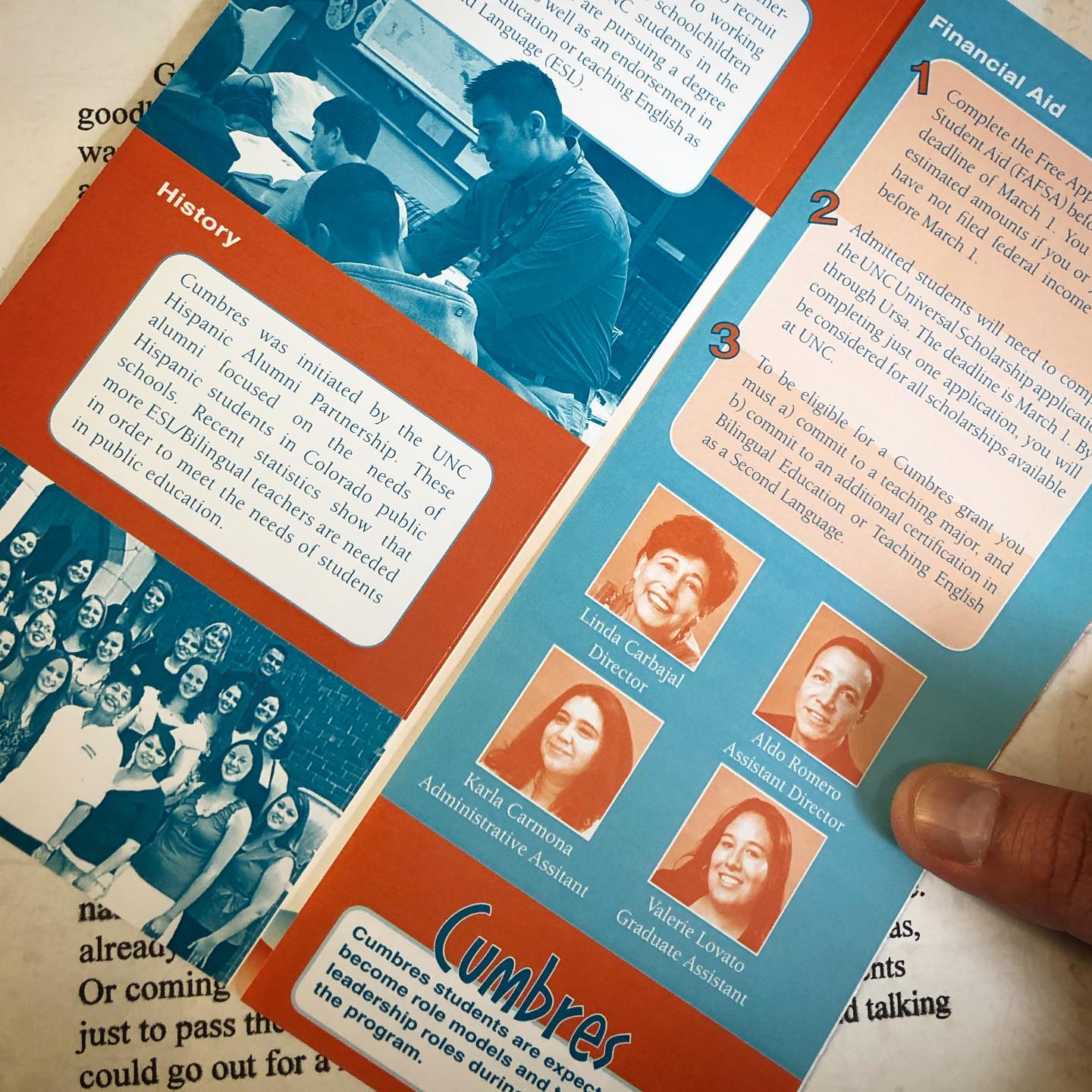

by Cristóbal (Chris) Garcia, Staff Fellow for Hispanic Serving Institution Initiatives, University of Northern Colorado

Nearly 1,000 U.S. colleges and universities are designated as current or emerging Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSI) . With 31% of the Latino population under the age of 18 and Latino enrollment in higher education surpassing the growth rate of any other ethnic identity or racial group, institutions of higher learning across the U.S. are preparing for future enrollment that is increasingly Latino.

However, even for schools at the forefront of serving Latino students, we continue to see gaps in retention and graduation rates between Latino students and their white counterparts. For Latino students, this can mean more time in college, more educational debt, a longer wait to launch a career, and less economic opportunity throughout their lifetime.

I have spent nearly 15 years working in higher education; I currently co-lead HSI Initiatives at the University of Northern Colorado (UNC) and serve as a member of Colorado’s statewide HSI Consortium. I am proudly Mexican-American, have lived on both sides of the U.S.–Mexico border, and have had the privilege of growing up both bilingual and bicultural.

For me, and so many Latinos in the U.S., education is a pathway to possibility. As leaders in higher education, we share the opportunity and responsibility to better serve the students and families who are enrolling and investing in our institutions. To truly serve Latino students in our spaces of higher learning, let’s consider that student “success” is not simply because of a student’s academic experience; It also includes an enriching experience that integrates their cultural identity and social well-being.

Below, I have identified five focus areas to better serve Latino-identifying students on higher education campuses.

Addressing Implicit Bias in Higher Education

In my experience, as staff and faculty at colleges and universities begin to ask the question of how to better serve students who have not traditionally had access to higher education, they may come across entrenched experiences of implicit bias in their campus and local communities.

In November 2020, our HSI working group conducted a series of interviews as part of UNC’s strategic plan to become a designated HSI by 2025. In these instances, we heard faculty and alumni say things like:

“Does this mean I have to lessen the academic rigor in my classes?” “This isn’t the school that I remember.” “Will we lose our accreditation?”

Embedded in these questions and comments is an implicit bias that becoming an HSI and better serving Latino students would decrease the academic effectiveness of the institution as a whole. This unconscious bias often leads to discrimination against people of color, including Latino students, faculty, and staff. Therefore, it is crucial for our campus communities to proactively address this issue through professional development on implicit bias, asset-based language, combating anti-racist and anti-black discrimination, and diversity, equity, and inclusion.

In addition to anti-bias training, I encourage campuses to take a step further and highlight the power of biculturalism and bilingualism many Latino students and other students of color bring to their university communities.

Read more: The Cognitive Benefits of Being Bilingual

Bridging the Communication Gap and Improving Storytelling

At UNC, we recognize that we aren’t just serving students but their entire families. Simply translating campus documents into Spanish is not enough; we must tell our story to students and their families in the language they identify best with and through the messaging they best connect with.

By highlighting key points about the college experience, institutions of higher education can:

Better inform prospective students and their families about the topics they truly care about — like the quality of educational programs and campus culture Create a better frame of reference for the college experience — especially for students who are the first in their families to attend college Contextualize college costs and financial aid processes — acknowledging that college is both an investment of time and financial resources Highlight the tangible benefits of college — finding a community on campus, the return on investment of a college degree, career advancement opportunities, and the strength of an alumni network

This messaging is important for Latino and first-generation families as they decide to invest in a college education or prepare for their children to move away from home with the promise of a better life.

My parents always told me, “No queremos que trabajes tan duro como nosotros / We don’t want you to work as hard as we do.” And for them, the pathway to a more fulfilled life was a solid education. In my experience, they were right.

Highlighting Latino Identity and Excellence in Creative Ways

Above is “Centro de Educación de Aztlan” created by Mexican/Chicana artist and UNC alumna Brenda Vargas-Gonzalez and muralist Leo Tanguma

College is a time for students to explore their various identities and find their voices in advocacy and action. This reflection is often stimulated by creating accessible and culturally reflective spaces on college campuses.

On an annual basis, UNC professor Dr. Jonathan Alcántar curates exhibits and programming and invites world-renowned Latino-identifying artists to our campus. In 2022, he launched several arts initiatives, including the Latinx Film Festival, in collaboration with UNC’s College of Performing and Visual Arts. He invited alumna Brenda Vargas-Gonzalez and muralist Leo Tanguma to transform an existing academic space into a culturally reflective study area they renamed “El Centro de Educación de Aztlan.”

Higher education institutions can continue supporting this reflection and exploration by hosting activities, reframing academic spaces, and encouraging the formation of Latino-centered student organizations that celebrate their culture and heritage.

Through these experiences, Latino students can connect with fellow university and local community members and learn more about themselves and their culture.

Promoting Unique Programming Tied to Latino Customs and Culture