Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Seven Strategies for Grammar Instruction

- Share article

The new question-of-the-week is:

How should we teach grammar to students?

Our students need to learn grammar, but the real question is how to teach it in ways that don’t bore them out of their minds.

Today, Jeremy Hyler, Sean Ruday, Joy Hamm, and Sarah Golden share their recommendations.

I’d also like to share my favorite grammar-instruction strategy—concept attainment.

In this inductive learning strategy, the teacher places examples, typically (though not always) from unnamed student work, under the categories of “Yes” and “No” and displays them on a document camera.

The teacher starts by covering up the examples and shows them one by one. After students see each new one, they work in pairs to try to determine why some examples are under “Yes” and others under “No” until they identify the “rule.”

The class constructs their own understanding of why the examples are in their categories. It’s a great tool for many lessons, and I like it especially for grammar and other writing.

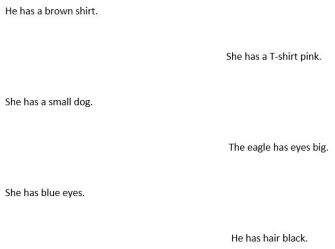

Here’s an example I used in my English-language learner class to teach about the appropriate placement of adjectives:

Concept attainment effectively turns instruction into sort of a “puzzle.”

You can see more examples of concept attainment here and here .

Now, it’s time for today’s guests:

Using Social Media

Jeremy Hyler is a middle school English and science teacher in Michigan. He has co-authored Create, Compose, Connect! Reading, Writing, and Learning with Digital Tools (Routledge/Eye on Education), From Texting to Teaching: Grammar Instruction in a Digital Age , as well as Ask, Explore, Write . Jeremy blogs at MiddleWeb . He can be found on Twitter @jeremybballer and at his website jeremyhyler40.com :

The question on how we approach grammar instruction has been debated for over 100 years. The debate has always been whether grammar should be taught in isolation or in context with the reading and writing that is being done in the classroom. Even the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) has a position statement on not teaching grammar in isolation.

Let’s be honest, it is impossible to try to shove every grammar skill into our students’ brains. And, yes, that is what often happens as we try to rush through the curriculum we have in front of us. As an educator with over 20 years experience, I don’t know every grammar skill in my heart. We have to begin very simply with two practices: Teach students the difference between formal and informal spaces and show students how the grammar skills they are learning can be applied to their own writing. Students will not see the value in grammar unless we actually show them how it’s applied. Furthermore, as teachers, we need to respect the spaces students write in day to day.

Seven years ago while at a conference, I created a template using Google Slides of the spaces students typically write in from day to day. The template ranges from Facebook to text messaging to Snapchat. I feel in order for students to have a better understanding of grammar skills, they need to know whether the spaces they write in the most are formal or informal. This discussion with students often leads to great conversations and insight about audience and who they are writing for when in a given space. When students are able to grasp how writing might change in these spaces, we then examine the grammar skill such as adjectives and how it is used in a mentor text we are reading at the time.

Students not only need to understand the different writing spaces they themselves write in, but how authors are using grammar and why authors might choose to make certain moves in the books we are reading. Once this is established, students then get to “play” with the mentor sentence and how it might look in the different spaces they write in on a daily basis. The template is a way for teachers to formatively assess student writing, and at the same time, it gives students a way to see how skills could be applied to different writing spaces.

As students grasp the current grammar lesson through the template, I then have them apply the skills to a formal piece of writing in class such as a literary analysis, compare/contrast, or argument paper. While students are writing, I ask them to use the highlight feature in Google Docs, so I can see they have correctly applied the skill they learned to their own writing. Plus, it makes it easier for me as their teacher to grade.

Though what I do takes more time than what most teachers want to take, students do grasp the concepts and retain the skills I am trying to teach them more so than if I were rapidly going through grammar and flooding their backpacks with worksheets. By scaffolding, I am building students toward the reason grammar is important while at the same time respecting the spaces they write in daily.

Five-Step Process

Sean Ruday is an associate professor of English education at Longwood University and a former classroom teacher. He has written 11 books on literacy instruction, all published by Routledge Eye on Education. His website is www.seanruday.weebly.com :

When I conduct workshops for teachers on grammar instruction, I ask participants to begin with a fast write on “teaching grammar.” A theme that often emerges from these responses is the challenge of teaching grammar in ways that are both engaging and effective.

For example, one teacher expressed, “Sure, I know some ways to teach grammar, but I definitely don’t know the best way. I can use textbooks and workbooks, but that doesn’t get any kind of results with my students.” This insightful point is reflected in research on grammar instruction, which has found that out-of-context grammar instruction with no connection to authentic writing often leads to student disengagement (Woltjer, 1998) and has very little impact on student writing (Weaver, 1998).

To address this issue, I use a five-step approach to grammar instruction that uses mentor texts to help students see grammatical concepts as tools that authors purposefully and authentically use to maximize the effectiveness of writing. After students are able to think of grammatical concepts in this way, they can analyze the importance of these concepts in published works, use them strategically in their own writing, and reflect on the impact those concepts had on the effectiveness of their pieces. The steps of the process and their descriptions follow:

1. Discuss the fundamental components of a grammatical concept.

Before students begin thinking about how published authors use a specific grammatical concept and why it is important to effective writing, they must understand the fundamentals of that concept. To facilitate this, I recommend conducting mini lessons with anchor charts and accessible examples to illustrate key attributes of grammatical concepts such as prepositional phrases, subordinate clauses, or specific nouns. Knowledge of these fundamentals will then enable students to think more analytically about grammatical concepts.

2. Show students examples from literature of that concept.

The next step in this process is to show students examples from literature of the grammatical concept you’re discussing. It’s best to select examples from texts that interest your students and are at their general reading levels. This practice is especially effective because it shows students that grammatical concepts don’t just exist in isolated grammar exercises—instead, they are found in literature and are tools published writers use authentically.

3. Talk with students about why the grammatical concept is important to the piece of literature.

This instructional practice is a logical follow-up to the previous one; after you show students examples from literature of a particular grammatical concept, talk with them about why that grammatical concept is important to the pieces of literature. The specific conversation you’ll have about this topic will vary based on the grammatical concept, but each conversation should be based on the same “big idea”: How does the use of this grammatical concept enhance this piece of literature?

4. Work with students as they apply the concept to their own writing.

After students understand why a specific grammatical concept enhances a published text, the next step is to ask them to strategically use that concept in their own writing. To do this, students identify instances in their works where the piece could be enhanced by the concept and use it in those situations; this requires students to approach the concept as a purposefully used tool just as published authors do.

5. Ask students to reflect on the concept’s impact.

Finally, I recommend asking students to reflect on the importance of the focal grammatical concept. To engage students in this kind of reflection, I first ask them to think about how they used the grammatical concept in their own writing. To facilitate this, I ask the students to find an example of the concept in their writing and explain what it does to enhance the piece. After students share their responses with the class, I ask them to reflect on why this concept is an important tool for effective writing.

- Teaching English-Language Learners

Joy Hamm has taught 11 years in a variety of English-language settings, ranging from kindergarten to adult learners. The last few years working with middle and high school Newcomers and completing her M.Ed. in TESOL have fostered stronger advocacy in her district and beyond:

Grammar is best embedded through targeted expressive and receptive practice in the context of content. Begin with formatively assessing students’ prior grammar knowledge by gathering at least three writing samples per student in order to analyze grammar patterns. Often multiple proficiency levels are in the same ESOL class, so target one grammar error largely observed, such as past tense irregular verbs or repetitive sentence structure. Next, provide students with multiple opportunities and modalities to learn and practice the new grammar concept using the four language domains.

For example, your analysis may reveal that your ELs need instruction about conjunctions. First, create an anchor chart of conjunctions as a visual display and begin with a read-aloud mentor text full of conjunctions (visit Jenn Larson’s blog for examples). Pause often to think aloud as students listen and begin to make connections. Display other samples on the board or as tangible sentence strips and get small groups talking about how sentence meaning changes based on the conjunction used, etc. Next, provide guided practice where students combine sentences using modified content-area text examples and share their results with the class. Also, use this interactive time for brief moments of direct instruction as needed.

Once students have lots of receptive exposure to the grammar concept, begin their expressive application through typed writing prompts or peer speaking activities which are related to your content material. Your EQ should emphasize using a variety of conjunctions along with answering the content prompt. (Continue to exhibit the anchor chart of conjunction vocabulary as a scaffold!) Additionally, provide students with ownership by modeling your own writing. Display your PC computer screen and use the Ctrl+F keys to search how many times you used different conjunctions throughout your writing. Discuss with students how you could combine sentences or create new meaning by using a different conjunction from the anchor chart. Finish with students going back to their own writing and using the Ctrl+F keys to revise their own writing.

During speaking practice, have ELs record using speakpipe.com, another free online tool, or their phone. After recording their responses to the EQ content prompt, students will relisten to themselves or another student’s recording and focus on the variety of conjunctions or complex sentences heard. After students evaluate and provide feedback for one another, they will rerecord themselves and send me both recorded links. I always require both because I often grade my ELs on the progress made between the first and second recording. This is also more equitable for multiproficiency levels in one class.

‘Sentence Expansion’

Sarah Golden is currently the coordinator of language arts for the lower and middle school divisions at The Windward School ’s Manhattan campus. She is on the faculty of The Windward Institute and presents the workshop Expository Writing Instruction: Part Two – Grades 4-9:

Grammar should be taught to students in context using specific sentence activities such as sentence combining and expansion. I have found this to be most effective in my own practice teaching students of all ages, and it is also supported by research. Utilizing the direct (explicit) teaching model, a specific grammatical concept should first be taught and modeled by the teacher, in the context of a specific sentence activity. This is most effective when done in a whole-class lesson that promotes a high level of student participation. Then, students should practice the newly learned concept, so they may reach mastery and generalization of the skill. With plenty of guided practice at the sentence level, students will ultimately begin to incorporate the learned structures and concepts into their independent writing.

Very young students could begin learning basic sentence structure, sentence boundaries, and the components of a sentence by engaging in oral or written activities that require them to identify sentences and fragments. When students identify fragments, they must always be required to change the fragments into a sentence (MacDermott-Duffy, 2018). As students move up through the grades, this activity can be used to teach other grammatical structures such as dependent clauses.

Another way to introduce students to or reinforce grammatical concepts used in writing is through a strategy, which in the Windward Expository Writing Program (MacDermott-Duffy, 2018) is called sentence expansion . In this strategy, students are provided with a short unelaborated sentence and prompted, using question words, to add words, phrases, or clauses to the given simple sentence. This enables students to learn and practice skills like appropriate pronoun use, adverbial clauses, and the use of appositive phrases or relative clauses. Additionally, students can practice different sentence structures if they are prompted to start with, for instance, the subordinating clause or information generated by a specific question word.

A third strategy, and one which is particularly effective and strongly supported by research (Saddler, 2007 as cited in MacDermott-Duffy 2018), is sentence combining. In this strategy, students combine simple sentences into more complex, and therefore longer, sentences using a variety of strategies that help students learn grammatical concepts including punctuation, tense and number agreement, parts of speech, coordinating and subordinating conjunctions, and relative clauses (MacDermott-Duffy, 2018; Scott, C. et al., 2006 as cited in MacDermott-Duffy, 2018).

Thanks to Jeremy, Sean, Joy, and Sarah for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones are not yet available). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

- Race & Racism in Schools

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Facing Gender Challenges in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech in the Classroom

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in Schools

- Reading Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- Entering the Teaching Profession

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in Schools

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

Teaching and Learning English Grammar: Research Findings and Future Directions - 2015 - Front matter and Table of Contents

Christison, M.A., Christian, D., Duff, P., & Spada, N. (Eds.). (2015). Teaching and learning English grammar: Research findings and future directions. New York: Routledge. ABSTRACT An important contribution to the emerging body of research-based knowledge about English grammar, this volume presents empirical studies along with syntheses and overviews of previous and ongoing work on the teaching and learning of grammar for learners of English as a second/foreign language. A variety of approaches are explored, including form-focused instruction, content and language integration, corpus-based lexicogrammatical approaches, and social perspectives on grammar instruction.... You'll find the (draft) chapter by Duff, Ferreira & Zappa-Hollman under 'Articles' on this site. TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword --Joanne Dresner Preface --MaryAnn Christison, Donna Christian, Patricia A. Duff, and Nina Spada Part I. Overview of English grammar instruction Chapter 1. An overview of teaching grammar in ELT --Marianne Celce-Murcia Part II. Focus on form in second language acquisition Chapter 2. Focus on form: Addressing grammatical accuracy in an occupation-specific language program --Antonella Valeo Chapter 3. Teaching English grammar in context: The timing of form-focused intervention --Junko Hondo Chapter 4. Form-focused instruction and learner investment: Case study of a high school student in Japan ---Yasuyo Tomita Chapter 5: The influence of pretask instructions and pretask planning on focus on form during Korean EFL task-based interaction --Sujung Park Part III. The use of technology in teaching grammar Chapter 6. The role of corpus research in the design of advanced level grammar instruction --Michael J. McCarthy Chapter 7. Corpus-based lexicogrammatical approach to grammar instruction: Its use and effects in EFL and ESL contexts --Dilin Liu and Ping Jiang Chapter 8. Creating corpus-based vocabulary lists for two verb tenses: A lexicogrammar approach --Keith S. Folse Part IV. Instructional design and grammar Chapter 9. Putting (functional) grammar to work in content-based English for academic purposes instruction --Patricia A. Duff, Alfredo A. Ferreira, and Sandra Zappa-Hollman Chapter 10. Integrating grammar in adult TESOL classrooms --Anne Burns and Simon Borg Chapter 11. Teacher and learner preferences for integrated and isolated form-focused instruction --Nina Spada and Marília dos Santos Lima Chapter 12. Form-focused approaches to learning, teaching, and researching grammar --Rod Ellis Epilogue --Kathleen M. Bailey

Related papers

Received: April 15, 2019 Accepted: May 20, 2019 Published: May 31, 2019 Volume: 2 Issue: 3 DOI: 10.32996/ijllt.2019.2.3.24 Studies and research reveal that most English language learners (ELLs) encounter challenges when they write an academic paper in English due to lack of grammar. As most international universities require passing international tests as TOEFL, IELTS, GMAT, GRE, and other tests with high level, most international students fail to achieve this requirement. The reason, as some studies and research reveal, is attributed to lack of pedagogical grammar, namely in writing. Hence, this paper focuses on how to teach pedagogical grammar to help ELLs write effectively in academic situations. The paper is based on literature review and interviewing nine ELLs, regarding the challenges they encounter while writing in academic situations. The researcher has used qualitative research method to fulfill this study, trying to investigate about the challenges that ELLs encounter whil...

The Canadian Modern Language Review / La revue canadienne des langues vivantes, 2004

Duff, P., Ferreira, A., & Zappa-Hollman, S. (2015). In M. Christison, D. Christian, P. Duff & N. Spada (Eds.), Teaching and learning English grammar: Research findings and future directions (pp.139-158). New York: Routledge. ABSTRACT A growing body of curriculum development, instruction, and research focuses on ways of attending to grammar systematically in content-based academic English programs (Coffin, 2010). This work examines the functions of the grammatical structures to be learned to express particular meanings in oral and written texts within and beyond sentences in authentic discourse contexts (Derewianka & Jones, 2012). Content areas in which explicit grammatical instruction has been integrated successfully include social studies, history, geography, English, and mathematics in K-12 and higher education programs (e.g., Christie, 2004; Mohan, 1986; Schleppegrell, Achugar & Oteíza, 2004). In this chapter, we first discuss the changing contexts for the teaching of English grammar across educational programs and curriculum worldwide, particularly with relatively advanced learners engaged in English-medium instruction (i.e., content and language integrated learning). Next, we discuss traditional approaches to grammar instruction and research and then review some promising functional approaches being taken up by language educators and content specialists in the US, Australia, and other countries, and at our own institution in Canada. We provide theoretical and research foundations and examples of the implementation and effectiveness of such approaches to the teaching and learning of (discourse) grammar by examining nominalization and grammatical metaphor, for example. We conclude by discussing some implications of developments in this area for teacher education--for language instructors, teacher educators, and content specialists--as well as for program development and future research on grammar instruction.

Tesol Quarterly, 1998

TESL Canada Journal, 2000

This article examines a number of adult ESL grammar textbooks via an author designed checklist to analyze how well they incorporate the findings from research in communicative language teaching (CLT) and in form1ocused instruction (FFI). It concludes that although a few textbooks incorporate some of the research findings in CLT and FFI, they are not necessarily those chosen by the teaching institutions.

LiBRI. Linguistic and Literary Broad Research and Innovation, 2011

The present paper reports on a study that was carried out to compare the effectiveness of three instructional techniques, namely dialogues, focused tasks, and games on teaching grammar. The participants were 48 pre-intermediate EFL students that formed three experimental groups. A posttest consisting of 20 productive items was administered at the end of the treatment period which lasted for four sessions. The results revealed no statistically significant difference between the three groups. This suggests that the three instructional techniques had relatively the same effect on the accurate grammatical production of the learners.

Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 2004

Schenck, Andrew. An Investigation of the Relationship Between Grammar Type and Efficacy of Form-Focused Instruction. The New Studies of English Language & Literature 69 (2018): 223-248. Because phonological, semantic, and morphosyntactic characteristics of grammatical features can have a significant impact on form-focused instruction, utilization of different grammatical features to test new language teaching techniques may conflate determinations of efficacy or inefficacy. The purpose of this study was to holistically examine different types of instruction, comparing them with grammatical features to evaluate effectiveness. Forty-six experimental studies of form-focused instruction were selected for study. Comparison of effect sizes suggests that the efficacy of form-focused instruction differs considerably based upon the type of grammatical feature targeted. Input-based instruction (e.g.,input enhancement or explicit rule presentation) appears more useful for features like the plural -s, past -ed, and third person singular -s, which are phonologically insalient, yet morphologically regular. Output-based instruction (e.g., corrective feedback or recasts), in contrast, appears more effective with grammatical features such as questions, phrasal verbs, conditionals, and articles, which are syntactically or semantically complex. Overall, the results suggest that differences in grammar be considered before curricula or pedagogical interventions are designed. (State University of New York, Korea)

Some Notes on My Life 1934-1959, 1994

Projections of Jerusalem in Europe, edited by Bianca Kühnel, Neta Bodner, and Renana Bartal, 2023

Ariosto e gli antichi. Riscritture dei classici nell'"Orlando furioso", 2022

Isara solutions, 2022

Terres et Territoires, Acta Universitatis Carolinae Interpretationes, Vol. XI / No. 2 / 2021, 2021

Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 1996

American Journal of Enology and Viticulture, 2017

AAPG Bulletin, 2006

NeuroImage, 2012

European Heart Journal, 2007

Biodiversitas Journal of Biological Diversity

Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2010

Related topics

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- CAL Solutions

- Annual Reports

- Professional Development

Adult Literacy and Language Education

Dual Language and Multilingual Education

Immigrants and Newcomers

International Language Education

PreK-12 EL Education

Testing and Assessment

World Languages

- Resource Archive

Publications & Products

Teaching and learning english grammar: research findings and future directions.

Edited by MaryAnn Christison, Donna Christian, Patricia A. Duff, and Nina Spada Published by Routledge and the International Research Foundation for English Language Education ( TIRF )

An important contribution to the emerging body of research-based knowledge about English grammar, this volume presents empirical studies along with syntheses and overviews of previous and ongoing work on the teaching and learning of grammar for learners of English as a second/foreign language. It explores a variety of approaches, including form-focused instruction, content and language integration, corpus-based lexicogrammatical approaches, and social perspectives on grammar instruction.

Nine chapter authors are Priority Research Grant or Doctoral Dissertation Grant awardees from The International Research Foundation for English Language Education (TIRF), and four overview chapters are written by well-known experts in English language education. Each research chapter addresses issues that motivated the research, the context of the research, data collection and analysis, findings and discussion, and implications for practice, policy, and future research. The TIRF-sponsored research was made possible by a generous gift from Betty Azar. This book honors her contributions to the field and recognizes her generosity in collaborating with TIRF to support research on English grammar.

Teaching and Learning English Grammar is the second volume in the Global Research on Teaching and Learning English Series, co-published by Routledge and TIRF. 2015 236 pages

Order online from the publisher website . Enter code AF001 at checkout to receive a 20% discount.

- Employee Resources

- Permissions

- Privacy Policy

Powered by World Data Inc.

Grammar still matters – but teachers are struggling to teach it

Professor of Linguistics, Lancaster University

Disclosure statement

Willem Hollmann is affiliated with the Committee for Linguistics in Education (CLiE) and with the Education Committee of the Linguistics Association of Great Britain (LAGB).

Lancaster University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Do you know what a suffix is, or how to distinguish adjectives from adverbs ? If you have a six or seven-year-old, the chances are they do. Or at least, the UK government now says they should – by the end of year 2, to be specific.

In year 3, primary schoolers turn their attention to prefixes and conjunctions. By the time pupils head to secondary school, they are expected to know what determiners and adverbials are. They should be able to recognise a relative clause as a special type of subordinate clause. And their creative writing should showcase modal verbs and the active and passive voice.

Obviously, for all this to happen, teachers need to be comfortable with these terms and the concepts they cover. And if you went to school before 1960, you probably are. However, between 1960 and 1988, English – in England and Wales – was taught in a virtually grammar-free manner.

While grammar made a comeback in 1988, with the introduction of the national curriculum, many teachers today feel ill-prepared to teach it. And that’s because, as I and other language experts have pointed out , they themselves were never taught much, if any, grammar. And appropriate teaching support and materials are lacking.

Of course, grammar at school often becomes a political issue , with liberals rejecting a more conservative insistence on so-called correct grammar. But as a Dutch linguist, my perspective is that learning grammar isn’t about speaking properly. It is about gaining a broader understanding of one’s own language and how to use it creatively. It’s also a useful tool for learning other languages.

Grammar-free teaching

Before 1960, the way in which British schools taught English grammar was based on Latin. Categories that had been developed for Latin grammar were imposed on English. That frequently made little sense because English is a very different language.

From the 1920s, this Latinate approach was highly criticised , and the argument against English grammar in schools gathered force in the 1940s and 1950s. Studies in Scotland and England in the middle of the 20th century claimed that the subject was essentially too difficult for children.

Research suggests the disappearance of grammar from the English school curriculum in 1960 is also due to an increased emphasis on English literature. The idea was that children would pick up the needed grammar more or less as they went along.

The 1970s marked a turning point. The government published several critical reports , citing in particular high levels of illiteracy in England and Wales. This led to a U-turn in policy, with grammar gradually returning to the classroom from 1988.

Research in the years that followed showed that student teachers didn’t have the knowledge they needed to teach it, though. The authors of a 1995 study of 99 student teachers in Newcastle noted –- and subsequent researchers concurred – that without significant input during training, teachers would struggle.

Why grammar matters

Teachers’ knowledge about grammar remains problematic. A 2016 case study of a primary school in the north-west of England (which was rated “good” by Ofsted) analysed data collected over ten months from June 2014 to March 2015 on what teachers knew.

When questioned about the terms specified in the national curriculum, including adjective, conjunction and determiner, the teachers only got about half of the questions right. Teaching-support staff fared even worse.

Why should we care about whether our teachers are well equipped to teach grammar? In the first instance, we should because they have to. It is crucial that teachers have the knowledge and confidence to support pupils through statutory subjects , on which, in non-pandemic times at least, they will be formally tested .

A growing body of evidence also shows that teaching grammar may enhance students’ writing development . This is because knowledge about concepts such as active and passive voice may allow for more precise and productive conversations between teachers and students about textual effects and possibilities. And it may enable students to shape their prose more consciously.

It can also help them learn new languages . If learners already have a conscious awareness of linguistic features such as tenses, that helps them to recognise and discuss what is the same or different in another tongue . And though more research is needed , some scholars have even suggested that grammar teaching may improve general thinking skills .

Many publishers have stepped into the gap left by the government and have produced support materials to help (student) teachers master the grammatical terms the curriculum specifies. But publishers operate in a free market without oversight from the Department for Education. Also, the materials have generally not had any input from academic grammarians. As a result, they often contain mistakes.

These are not just typos. For instance, one book aimed at teachers analyses “have” as a modal verb, which it is not, and suggests that modal verbs form tenses, which they do not. Another grammar book categorises “don’t touch!” as an exclamation, while it is actually a straightforward example of a command. Such errors are not dissimilar to the suggestion that seven times seven is 48, when all year 4s are of course taught that it is in fact 49.

Furthermore, it is well known that teachers experience more job stress than other professionals. In this context it may not be reasonable to expect them to have to independently procure and work through professional development materials in a subject area of such importance.

Our baseline argument is that when it comes to recognising the importance of grammar, the curriculum is on point. However, the government should equip its teachers to teach it. It needs to commission research into the exact nature of the gaps in their knowledge. And it should get academic grammarians on board in developing appropriate support materials and training.

- National Curriculum

- Teacher training

- Primary school

- English language

- English grammar

Postdoctoral Research Associate

Project Manager – Contraceptive Development

Editorial Internship

Integrated Management of Invasive Pampas Grass for Enhanced Land Rehabilitation

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The research: spotlight on a grammar case study ... Citing McQuade, Constance Weaver, the author of Teaching Grammar in Context (1996), argued that we should teach aspects of grammar that are most relevant to writing, such as subject-verb agreement, sentence combining, and punctuation. Significantly, Weaver asserted that the most effective ...

Teaching grammar is a potentially face-threatening exercise as it provides opportunities for students to test teachers' knowledge ... (PCK) in language teaching, more research into the knowledge bases needed by language teachers is required (Andrews, 2003; 2007a; 2007b). Grammar is thought by some to be an important component

Research on grammar teaching covers a variety of topics and adopts plural perspectives. The III International Conference on Teaching Grammar (Congram19), held at the Autonomous University of ...

Abstract. This selective review of the second language acquisition and applied linguistics research literature on grammar learning and teaching falls into three categories: where research has had little impact (the non-interface position), modest impact (form-focused instruction), and where it potentially can have a large impact (reconceiving ...

Despite undeniable advances in research on language learning strategies in the last several decades, empirical investigations of actions and thoughts that learners engage in to better understand and use grammar structures in different contexts, or grammar learning strategies (GLS), remain scarce. Moreover, there is a paucity of studies

2. Show students examples from literature of that concept. The next step in this process is to show students examples from literature of the grammatical concept you're discussing. It's best to ...

TESL Canada Journal, 2000. This article examines a number of adult ESL grammar textbooks via an author designed checklist to analyze how well they incorporate the findings from research in communicative language teaching (CLT) and in form1ocused instruction (FFI).

Edited by MaryAnn Christison, Donna Christian, Patricia A. Duff, and Nina Spada Published by Routledge and the International Research Foundation for English Language Education (). An important contribution to the emerging body of research-based knowledge about English grammar, this volume presents empirical studies along with syntheses and overviews of previous and ongoing work on the teaching ...

In this chapter we briefly review the major developments in the research on the teaching of grammar over the past few decades. This review addresses two main issues: (1) whether grammar teaching makes any difference to language learning; and (2) what kinds of grammar teaching have been suggested to facilitate second language learning.

Our research has demonstrated that teaching grammar as choice can improve students' writing attainment (Jones, Myhill, and Bailey 2013; Myhill et al 2012), but also that in some contexts the efficacy of the pedagogy is limited if teachers are not confident in implementation (Tracey et al. 2019).

With the rise of communicative methodology in the late 1970s, the role of grammar. instruction in second language learning was downplayed, and it was even suggested. that teaching grammar was not ...

research is grammar teaching [1-3]. Debates on teaching grammar actually focused on the ways whether it is taught implicitly or explicitly and deductively or inductively which is aimed at helping students master it so that they can use it in their communication skill both in oral and written language [4, 5]. In terms of teaching

through comprehensive analysis. of past research. DOI 10.1515/iral-2015-0038. Abstract: Holistic study of grammar instruction is needed not only to establish. the effectiveness of pedagogical ...

While grammar made a comeback in 1988, with the introduction of the national curriculum, many teachers today feel ill-prepared to teach it. And that's because, as I and other language experts ...

The place of grammar within the teaching of writing has long been contested, and a vast body of research has found no correlation between grammar teaching and writing attainment. However, recent studies of contextualized grammar teaching have argued that if grammar input is intrinsically linked to the demands of the writing being taught, a ...

An important contribution to the emerging body of research-based knowledge about English grammar, this volume presents empirical studies along with syntheses and overviews of previous and ongoing work on the teaching and learning of grammar for learners of English as a second/foreign language.

Hinkel, E. (2013). Research findings on teaching grammar for academic writing. English Teaching, 68(4), 3-21. In recent years, in ESL pedagogy, the research on identifying simple and complex grammatical structures and vocabulary has been motivated by the goal of helping learners to improve the quality and sophistication of their second language ...

This selective review of the second language acquisition and applied linguistics research literature on grammar learning and teaching falls into three categories: where research has had little impact (the non-interface position), modest impact (form-focused instruction), and where it potentially can have a large impact (reconceiving grammar). Overall, I argue that not much second language ...

Effective Ways of Teaching Grammar. 6. Richard & Rogers (2003, Ibid) state that th is method approaches "… language. learning as the analysis of language (mental exercising of learning ...

For example, stories, poems, texts. Grammar I usually teach in Hebrew. (Teacher 4) If I speak only in English when explaining grammar, not all the kids will get it. It will get into half of the students' heads. Therefore, I explain the rules of grammar in Hebrew. (Teacher 5) ... Language Teaching Research, 26(4), 642-670.

grammar instruction in the teaching of writing - whether grammar and writing should be taught separately, or in an integrated manner in the English Language writing class. This paper describes an action research project aimed at contributing to this debate through some teachers'