The War on Terror and the Demonization of Student Protests

A s the incoming freshman class of 2028 moves into dorms and considers its first set of course offerings at universities across the country, some of them may notice features of campus life they were not expecting.

At the University of Pennsylvania, a sign has been posted on the College Green informing students that all “events, demonstrations, rallies, protests, and large gatherings require prior University approval.” At Columbia University, the activist group Students for Justice in Palestine has been permanently banned from Instagram, a platform where it had amassed more than 120,000 followers. At NYU, security guards have been stationed around fenced-off benches so that students are unable to assemble there, and the University of Michigan has instructed students and faculty to call the police if they run into any “disruptive protests.”

Universities have taken these measures because they are desperate to avoid a reprise of the pro-Palestinian and antiwar protests that roiled American campuses during the previous academic year, resulting in Congressional hearings, the resignation of multiple university presidents, the deployment of city police on campus grounds, the mass arrest of students, and (in Columbia’s case) the cancellation of commencement.

Read More: What America’s Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

It isn’t hard to understand why universities have taken these steps: there’s nothing career administrators dislike more than unpredictable events, negative media attention, and outraged donors. In doing so, however, they have not just failed to live up to their commitment to protect freedom of speech for their students—they have also revived an ugly episode from the early years of our now-concluded war on terror.

In the years following September 11, 2001, as the Bush administration sent Americans to war in Afghanistan and then Iraq, schools throughout the country were roiled by protests, including widespread student walkouts. On the campus of Denver, Colorado’s three Auraria colleges, students even established an encampment . With antiwar activism exploding across America, these student actions became part of a long linage of campus protest movements, including those during the Vietnam War in the ‘60s and the anti-Apartheid protests of the ‘80s.

But instead of welcoming their students’ contributions to the country’s most important political debate, many university administrators cooperated with government and law enforcement agencies in subjecting protesters to surveillance and repression.

Many Muslim and Arab students during this period were already dealing with a hostile campus atmosphere characterized by suspicion, harassment, and intimidation. On September 14, 2001, a Muslim student at Arizona State University was beaten and pelted with eggs in a parking lot, and two men at the University of North Carolina in Greensboro beat a Lebanese student while shouting “Go home, terrorist!” Other Muslim and Arab students reported being singled out for hostile questioning by their professors. Muslim student associations (MSAs) should have served as a refuge for students during this period, but they became targets as well, as when someone threw rocks through the windows of the MSA office at Wayne State University.

What’s more, it soon became clear that students faced surveillance and intimidation from government agencies as well. After September 11, the FBI began enlisting hundreds of campus police departments to help out in surveilling what the Washington Post ominously described as “insular communities of Middle Eastern students.” And in 2003, the Department of Homeland Security began requiring that institutions of higher education furnish federal law enforcement with names, addresses, and other information about all foreign students studying inside the United States, with any unapproved change in address or college major resulting in immediate deportation.

As some faculty objected at the time, this kind of blanket surveillance—as opposed to targeted investigations into specific acts of criminal activity—could only have a chilling effect on students’ willingness to participate in political debate, especially given the FBI’s well-known history of targeting student activists during the Vietnam era. But these objections largely went unaddressed. Hundreds of campuses welcomed the increased FBI presence, and, as the sociologist Lori Peek noted in her book Behind the Backlash , “about two hundred colleges and universities … turned over personal information about foreign students and faculty members to the FBI, most of the time without a subpoena or a court order.”

During this same period, the New York Police Department also established what it called the Demographics Unit, an intelligence operation tasked with gathering covert information on Muslim communities throughout the NYC metropolitan area. MSAs in New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania were all subject to police surveillance . In one instance, the NYPD even sent an undercover officer on an MSA whitewater rafting trip to upstate New York in 2008. The officer reported back to his superiors that “in addition to the regularly scheduled events (Rafting), the group prayed at least four times a day.”

This surveillance didn’t just sow distrust within MSAs—how could students be sure that the new member wasn’t actually an undercover agent?—it also made it difficult and in many cases impossible for Muslim students at American universities to engage publicly in civic life.

“When it came to the MSA and the activities we would do,” one college student named Malaika said to researcher Sunaina Maira, who spoke to students for her book The 9/11 Generation: Youth, Rights, and Solidarity in the War on Terror . “We tried to avoid all politics. We didn’t know where that would lead and we wanted to keep it strictly educational.” So instead of participating in debates on the day’s most important political issues, Muslim students found themselves simply trying to explain, over and over, that they were just as American as anyone else. Anything more ambitious than a friendly, anodyne presentation explaining how Muslims celebrated different holidays could draw an immediate firestorm of criticism.

This repressive atmosphere persisted for years. As late as 2013, for instance, when Students for Justice in Palestine organized a group of students at Northeastern University to stage a walkout at an event where Israeli soldiers were speaking, the university condemned the students, forced them to produce a “ civility statement ,” and put the campus SJP group on probation.

Read More: How the Idea of the College Campus Captured American Imaginations—And Politics

The parallels between America’s repression of Muslim student activity back in the 2000s and administrator attempts to stamp out pro-Palestinian protests on college campuses today are striking. In both cases, university and government officials have worked to silence Muslim and Arab students whose families have been directly impacted by U.S. support for military violence abroad. In both cases, students who object to America’s role in fueling that violence have been slandered as terrorist sympathizers (and, today, as antisemites). And in both cases, these violations of students’ First Amendment rights have been justified on the spurious grounds that peaceful protesters and student groups present some unspecified but grave “threat” to their wider student communities.

The most vivid recent illustration of this mindset is NYU’s revised “Guidance and Expectations on Student Conduct,” which declares that Zionism is now a protected aspect of religious identity and suggests that the university may now treat criticism of Zionism as tantamount to antisemitism. If guidelines like these were actually about combating antisemitism, then universities would not also be evicting and suspending Jewish student protesters, or banning groups such as Jewish Voice for Peace from their campuses. By drawing a false equivalence between Zionism and Judaism, administrators are declaring that such a debate is bigoted by definition, and thus shouldn’t be allowed to happen at all.

At Columbia University, where the most unsettling scenes of police repression played out at the end of the last academic year, protests started up immediately upon students’ return to campus, with several dozen demonstrators picketing on the first day of the new semester.

Recent actions have not approached the scale of what occurred in the spring, but that should not be mistaken as a sign that student anger about the war has dissipated. For one thing, protests take planning, and students have only just returned to campus. For another, they no longer have the advantage of surprising university administrators who spent the summer developing new campus policies and security measures. At Columbia, for example, campus access has been restricted to people with university IDs, and the University of California system has banned both encampments and the use of masks.

If last spring is any guide, students who decide to defy these bans will face suspension, expulsion, and arrest—punishments, in other words, that can severely impact their ability to acquire a degree or find a job after graduation.

These threats may work—it’s not easy to keep speaking up when doing so may cost you a college degree, or when truck-mounted doxing billboards park outside campus, identify students by name, and identify them as “leading antisemites.” But student groups at Columbia have insisted they will keep going “ no matter the individual cost ,” and their promises should not be taken lightly. With Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu scheduled to address the United Nations in New York at the end of September, and with a closely contested U.S. election to follow soon after, one should not be surprised if student protesters are move back toward the center of the political firestorm surrounding U.S. support for Israel’s war.

In the early 2000s, the repression of student political activity in the U.S. contributed to one of the most conformist political climates this country has ever seen and made it easier for the Bush administration to launch one of the most wasteful and brutal wars in American history. Today, many of our most prestigious universities are making the same mistakes.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Economy is Doing in the Swing States

- Harris Battles For the Bro Vote

- Our Guide to Voting in the 2024 Election

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at [email protected]

Home — Essay Samples — War

Essays on War

The assassination of patrice lumumba: a historical analysis, analysis of "a rumor of war" by philip caputo, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

The Mexican-american War: Causes, Consequences, and Legacy

Conspiracy theories of the vietnam war, "pink and say": a summary and analysis, the missouri compromise: a precursor to civil war, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

The Adam-onís Treaty: a Landmark in U.s.-spanish Relations

The causes and effects of world war ii: a comprehensive analysis, women in combat: advancing gender equality and military effectiveness, why is ww1 inevitable, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

The Importance of The Marines

The titanic research paper, alas, babylon: analysis, the day lincoln was shot analysis, why the civil war was avoidable, pros and cons of reconstruction, glory and the movie glory, analysis of cornerstone speech, richard nixon's speech rhetorical analysis, topics in this category.

- World War I

- World War II

Popular Categories

- Vietnam War

- Invasion of Iraq

- American Civil War

- Atomic Bomb

- Cruise Missile

- Effects of War

- Guerrilla Warfare

- Hundred Years War

- Israeli Palestinian Conflict

- Mexican War

- Modern Warfare

- Nuclear War

- Nuclear Weapon

- Russia and Ukraine War

- Seven Years War

- Soviet-Afghan War

- Syrian Civil War

- Tet Offensive

- The Spanish American War

- Trench Warfare

- Women in Combat

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write the Political and Global Issues College Essay

Essays are one of the best parts of the college application process. With your grades in, your test scores decided, and your extracurriculars developed over your years in high school, your essays are the last piece of your college application that you have immediate control over. With them, you get to add a voice to your other stats, a “face” to the name, so to speak. They’re an opportunity to reveal what’s important to you and what sets you apart from other applicants and tell the admissions committee why you’d be an excellent addition to their incoming student class.

Throughout your college applications process, there are many different types of essays you’ll be asked to write. Some of the most popular essay questions you’ll see might include writing about an extracurricular, why you want to matriculate at a school, and what you want to study.

Increasingly, you might also see a supplemental college essay asking you to discuss a political or global issue that you’re passionate about. Asking this type of question helps colleges understand what you care about outside of your personal life and how you will be an active global citizen.

Some examples from the 2019-2020 cycle include:

Georgetown University’s Walsh School of Foreign Service : Briefly discuss a current global issue, indicating why you consider it important and what you suggest should be done to deal with it.

Yeshiva University Honors Programs : What is one issue about which you are passionate?

Pitzer College : Pitzer College is known for our students’ intellectual and creative activism. If you could work on a cause that is meaningful to you through a project, artistic, academic, or otherwise, what would you do?

Your GPA and SAT don’t tell the full admissions story

Our chancing engine factors in extracurricular activities, demographics, and other holistic details. We’ll let you know what your chances are at your dream schools — and how to improve your chances!

Our chancing engine factors in extracurricular activities, demographic, and other holistic details.

Our chancing engine factors in extracurricular activities, demographic, and other holistic details. We’ll let you know what your chances are at your dream schools — and how to improve your chances!

Tips for Writing the Political and Global Issues College Essay

Pick an issue close to your life.

When you first see a political and global issues prompt, your gut reaction might be to go with a big-picture topic that’s all over the news, like poverty or racism. The problem with these topics is that you usually have a page or less to talk about the issue and why it matters to you. Students also might not have a direct personal connection to such a broad topic. The goal of this essay is to reveal your critical thinking skills, but the higher-level goal of every college essay is to learn more about who you are.

Rather than go with a broad issue that you’re not personally connected to, see if there’s just one facet of it that you can contend with. This is especially important if the prompt simply asks for “an issue,” and not necessarily a “global issue.” While some essay prompts will specifically ask that you address a global issue (like Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service), there are still ways to approach it from a more focused perspective.

For example, if you were to talk about world hunger, you could start with the hunger you see in your community, which is a food desert. For your solution, you can discuss your plan to build a community garden, so the town is able to access fresh produce. Food deserts, of course, aren’t the only reason world hunger exists; so, you should also explore some other reasons, and other solutions. Maybe there is a better way to prevent and recuperate produce currently being wasted, for instance. If the prompt doesn’t specifically ask for a global issue, however, you could simply focus on food deserts.

For another example, maybe you want to talk about climate change. A more personal and focused approach would deal with happenings in your community, or a community you’ve had contact with. For instance, perhaps your local river was polluted because of textile industry waste; in this case, it would be fitting to address fast fashion specifically (which is still a global issue).

Remember your audience

As you’re approaching this essay, take care to understand the political ramifications of what you’re suggesting and how the school you’re addressing might react to it. Make sure you understand the school’s political viewpoints, and keep in mind that schools are hoping to see how you might fit on their campus based on your response.

So, if you’re applying to a school known for being progressive, like Oberlin or Amherst, you might not want to write an essay arguing that religious freedom is under threat in America. Or, if you’re applying to Liberty University, you should probably avoid writing an essay with a strong pro-LGBTQ stance. You don’t have to take the opposite position, but try picking a different issue that won’t raise the same concerns.

If you have no political alignment, choose economics

If you find yourself applying to a school with which you share no political viewpoints, you might want to consider if the school would even be a good fit for you. Why do you really want to go there? Are those reasons worth it? If you think so, consider writing about an economic issue, which tend to be less contentious than social issues.

For instance, you could write about the impact of monopolies because your parents own an independent bookstore that has been affected by Amazon. Or you could discuss tax breaks for companies that keep or move their production domestically, after seeing how your town changed when factories were moved abroad. Maybe tax filing is a cause you’re really passionate about, and you think the government should institute a free electronic system for all. No matter what you write about here, the key is to keep it close to home however you can.

Pick the best possible framing

When you’re writing an essay that doesn’t fully align with the political views of the school you’re applying to, you’ll want to minimize the gap between your viewpoint and that of the school. While they still might disagree with your views, this will give your essay (and therefore you) the best possible chance. Let’s say you’re applying to a school with progressive economic views, while you firmly believe in free markets. Consider these two essay options:

Option 1: You believe in free markets because they have pulled billions out of terrible poverty in the developing world.

Option 2: “Greed is good,” baby! Nothing wrong with the rich getting richer.

Even if you believe equally in the two reasons above personally, essay option 1 would be more likely to resonate with an admissions committee at a progressive school.

Let’s look at another, more subtle example:

Option 1: Adding 500 police officers to the New York City public transit system to catch fare evaders allows officers to unfairly and systematically profile individuals based on their race.

Option 2: The cost of hiring 500 additional police officers in the New York City public transit system is higher than the money that would be recouped by fare evasion.

While you might believe both of these things, a school that places a lower priority on race issues may respond better to the second option’s focus on the fallible economics of the issue.

Structuring the Essay

Depending on how long the essay prompt is, you’ll want to use your time and word count slightly differently. For shorter essays (under 250 words), focus on your personal connection rather than the issue itself. You don’t have much space and you need to make it count. For standard essays (250-500 words), you can spend about half the time on the issue and half the time on your personal connection. This should allow you to get more into the nuance. For longer essays, you can write more on the issue itself. But remember, no matter how long the essay is, they ultimately want to learn about you–don’t spend so much time on the issue that you don’t bring it back to yourself.

Want help with your college essays to improve your admissions chances? Sign up for your free CollegeVine account and get access to our essay guides and courses. You can also get your essay peer-reviewed and improve your own writing skills by reviewing other students’ essays.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

Help inform the discussion

- X (Twitter)

William McKinley: Life Before the Presidency

William McKinley was born on January 29, 1843, in the small town of Niles, Ohio. He lived there until age ten, when he moved with his family to nearby Poland, Ohio. His loving family provided William Jr., the seventh of eight children, with a fun-filled childhood that was also carefully guided by his parents. Like most young boys, he spent his childhood fishing, hunting, ice skating, horseback riding, and swimming. His father owned a small iron foundry and instilled in young William a strong work ethic and a respectful attitude. Nancy Allison McKinley, his devoutly religious mother, taught him the value of prayer, courtesy, and honesty in all dealings.

Education and Military Service

Education was important to William, and he studied hard at a school run by the Presbyterian seminary in his hometown of Poland, Ohio. Upon graduation, he entered Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania, in 1860. He attended Allegheny for only one term, however, because of illness and financial difficulties.

When the Civil War started, William joined the Twenty-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry. During the war, the young private proved himself a valiant soldier on the battlefield, especially at the bloody battle of Antietam. As a commissioned officer, Second Lieutenant McKinley served on the staff of Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes, future President of the United States. His relationship with Hayes, whom he considered his mentor, remained constant throughout his life. He ended his four-year stint in the Army as a brevet major, gaining a title that would stay with him throughout his political career.

Law and Political Career

When the Civil War ended, McKinley returned to Ohio to begin his career in law and politics. He studied law at Albany Law School and, after passing the bar exam in 1867, began his legal practice in Canton, Ohio. At a Canton picnic in 1869—the year he entered politics—McKinley met and began courting his future wife, Ida Saxton, marrying her two years later. He was twenty-seven and she was twenty-three at the time.

Although practicing law was his profession, being involved with the Republican organization secured his future. His first election in 1869 was for county prosecutor. He ran successfully for Congress in 1876 and served until 1891, with the exception of one brief period when he lost in the election of 1882. As a congressman, McKinley became chair of the House Ways and Means Committee in 1889. In that powerful position, he drafted and steered to passage the McKinley Tariff of 1890. Because this strongly protectionist measure increased consumer prices considerably, angry voters rejected McKinley and many other Republicans in the 1890 election. Stunned by his defeat, McKinley returned home to Ohio and ran for governor in 1891, a race which he won, but only by a narrow margin.

As governor, McKinley worked to control—and, he hoped, to lessen—the discord between management and labor. He developed a system of arbitration designed to settle labor disagreements and convinced Ohio Republicans, many of whom refused to acknowledge the rights of labor, to support his arbitration program. McKinley, while sympathetic to workers, proved unwilling to acquiesce to all of their demands, calling out the National Guard in 1894 to curtail strike-related violence by the members of the United Mine Workers. In the face of the economic woes of the mid-1890s, McKinley showed himself to be a skilled and able politician. He even gained widespread public sympathy when his own financial fortunes suffered during the economic depression of 1893—he had co-signed the loans of a friend who subsequently went bankrupt. Winning favor with the voters, he was returned to the governor's office in 1894. With congressional and gubernatorial experience under his belt, as well as widespread popularity in the Republican Party, McKinley was in position to make a run for the White House in 1896.

Lewis L. Gould

Professor Emeritus of American History University of Texas

More Resources

William mckinley presidency page, william mckinley essays, life in brief, life before the presidency (current essay), campaigns and elections, domestic affairs, foreign affairs, death of the president, family life, the american franchise, impact and legacy.

Quick Links

- About the Essay Competitions

- Competition Rules

- 2024 Judges

- SECDEF Essay Competition

- CJCS Essay Competition

February 2025: Coordinators provide names of judges to NDU Press.

April 2025: Deadline for schools to submit nominated papers to NDU Press (POC: Jeff Smotherman, [email protected] ).

May 2025: Judges report first-round scores to NDU Press.

May 2025: Judges attend final-round conference at NDU.

For further information, please contact:

Jeff Smotherman Managing Editor 703-965-6949 [email protected]

Secretary of Defense and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Strategic Essay Competitions

Are you a Professional Military Education (PME) student? Imagine your winning essay appearing in a future issue of Joint Force Quarterly and a chance to catch the ear of the Secretary of Defense (SECDEF) or the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) on an important national security issue. Recognition by peers await the winners.

Who's Eligible: Students at the PME colleges, schools, and other educational programs, including Service research fellows and international students.

What: Research and write an original, unclassified essay in one (or more) various categories.

When: Essays may be written during the 2024–2025 academic year. Colleges are responsible for running their own internal competitions to select nominees, and must meet these deadlines:

- April 2025: Colleges submit nominated essays to NDU Press for first-round judging

- May 2025: Final-round judging and selection of winners

For complete information and competition rules, see your college’s essay coordinator or go to:

- SECDEF National Strategy Essay Competition

- CJCS National Defense and Military Strategy Essay Competition

How to Write a Great College Essay

Your college admissions essay is a key component of your college application. Unlike standardized test scores and grades, your essay gives your application a more human element. The power of a well-crafted college essay is not to be discounted, so use it to let your personality and background shine through. Here’s how to write a great college essay:

To write a great college essay, begin with brainstorming

Before drafting any portion of your essay, commit your ideas to paper. Jot down all the topics that come to mind for a potential essay—even those that may seem a bit outlandish.

Next, let some time pass (at least 24 hours) before you revisit your list of ideas. With a fresh set of eyes, add more topics or eliminate others until, over time, you are left with the idea that will become your essay.

[RELATED: 4 Reasons to Start Your College Essay This Week ]

To write a great college essay, compose a strong opening

The opening of your college essay is critical. You must captivate your reader from the very start, perhaps through suspense, humor, or the like. The first few lines of your essay are the hook that determine whether your reader will continue on feeling bored or intrigued.

To write a great college essay, aim to be different

The astounding volume of applications received by colleges has made it necessary for admissions counselors to get through many essays in a single day. If you want your essay to stand out amongst the vast competition, you must be different. Share a story that no one else could have told or discuss a random yet fascinating topic no other person has chosen. Always, however, steer clear of controversial or potentially offensive themes.

To write a great college essay, be genuine

If you want your college essay to have compelling emotion, you must be genuine. Avoid making up stories—real life is more interesting than fiction. When you retell true events you lived through, your writing naturally reflects the feelings you experienced in each moment.

To write a great college essay, spice up your vocabulary

A handful of advanced vocabulary words can give your essay an impressive touch. You do not need to add a three-syllable word to each line to produce such an effect; two or three well-used words in total is enough. If you have the perfect opportunity to include a word like “visceral” in your essay, seize it.

On the other hand, misused words, malapropisms, and typos can have a jarring effect on your reader. Before including an uncommon word in your essay, make sure to verify its definition and spelling.

To write a great college essay, mind your punctuation

Punctuation is sometimes an overlooked factor in essay writing. And though it may not be the most important factor, it is assumed that a high school senior knows the basic rules of punctuation use. Proper punctuation may not earn you extra points, but improper punctuation can certainly cost you points.

Give yourself a refresher course on how to use commas and periods, the most commonly used punctuation marks. Before including a less common mark such as a semicolon or an em dash, make sure you understand the rules that govern its use.

To write a great college essay, get feedback

Show your essay to at least two trusted people before you submit the final version. Ask for honest feedback, and be open to their suggestions. Rather than getting defensive, try to understand the reasons behind their criticisms.

Be aware that you may need to revise your essay several times, but this is completely normal. Be patient, positive, and open to improvement.

[RELATED: 3 Steps to Edit Your Essay ]

Your essay is an essential component of your college application. To succeed on it, think of it as a process.

Any topics you want to know more about? Let us know! The Varsity Tutors Blog editors love hearing your feedback and opinions. Feel free to email us at [email protected] .

Get Started Today

Maximize Your Potential

Unlock your learning opportunities with Varsity Tutors! Whether you’re preparing for a big exam or looking to master a new skill, our tailored 1:1 tutoring sessions and comprehensive learning programs are designed to fit your unique needs. Benefit from personalized guidance, flexible scheduling, and a wealth of resources to accelerate your education.

Related Posts

Can you pass the Citizenship Test? Visit this page to test your civics knowledge!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Elementary Curriculum

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Spanish Influence on American History

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

Press Releases

History teacher of the year, wunneanatsu lamb-cason has been named the 2024 national history teacher of the year .

Learn more about Lamb-Cason's achievements as an educator, advocate, author, and storyteller at Riverbend High School in Fredericksburg, Virginia.

Image: Wunneanatsu Lamb-Cason, 2024 National History Teacher of the Year

The Citizenship Test

Civics and american history.

The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History is excited to introduce our new Citizenship hub. Take the US Naturalization Exam—available in short, intermediate, full, and Kahoot! formats—and receive real-time feedback on your results!

Book Breaks: Now free and open to all!

Sundays at 2 p.m. et (11 a.m. pt) on zoom.

Upcoming Session: October 27, 2024 Author: Fareed Zakaria, CNN Book : Age of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the Present

All Audiences

Every Sunday

New Self-Paced Course

The early republic.

This course explores the American struggle to establish a republic on a national scale. Award-winning historian Alan Taylor examines the politics, economy, social structure, and culture of the union created by the American Revolution and the bitter but creative debates over the meaning of the Revolution and the proper form of republican government.

Regular Price: $39.99

Affiliate Price: $29.99

Image: An engraving of Thomas Jefferson by Cornelius Tiebout after a portrait by Rembrandt Peale, Philadelphia, 1801. (Yale University Art Gallery)

15 Professional Development Hours

Hamilton Education Program Online

Explore the newly redesigned EduHam Online website. It includes classroom account creation, a historical research library, a program roadmap, and a video library. You can now access the site using your Gilder Lehrman login and password (or create an account for free).

Master's Degree in American History

Register for spring 2025 courses.

MA students can choose from a wide variety of courses each semester. Browse fall courses, watch lecture previews, meet the professors, and see course details.

Spring Semester Dates

- Courses Start : Thursday, February 6, 2025

- Course Registration Ends: Wednesday, February 12, 2025

Learn with the Gilder Lehrman Institute

- MA in American History

Our master’s degree program gives K–12 educators an affordable way to earn a graduate degree while working full time.

Explore American history from your own home, in your own time, and at your own pace! Educators can obtain professional development credit.

These self-paced courses in American history are taught by the nation's top historians and are completely free for high school students.

Upcoming Events

- American Historical Holidays

Election Day

Deepen your knowledge of this holiday with historical documents, essays, videos, and lesson plans from the Gilder Lehrman Institute.

Veterans Day

Open House: MA in American History

Q&A session for prospective students to learn about the Gettysburg College–Gilder Lehrman master's degree program.

Upcoming Deadlines

Scholarly Fellowship Applications

Apply for a $3000 short-term research fellowship in the field of American history.

EduHam Online Competition and Lottery

Last day to submit your best creative piece for the chance to see Hamilton in New York City!

Apply to Master's Degree Program

Applications close for the Spring 2025 semester.

Every Sunday at 2:00 pm ET (11:00 am PT) on Zoom

Join us for our weekly interview series in which historians discuss their acclaimed books followed by a Q&A with the at-home audience. Please click any of the upcoming episodes to register. You can purchase any of the books featured on our bookshop.org page, for which we receive an affiliate commission.

Browse Past Episodes Learn More

David Greenberg, Rutgers University

John Lewis: A Life

Fareed Zakaria, CNN

Age of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the Present

Noliwe Rooks, Brown University

A Passionate Mind in Relentless Pursuit: The Vision of Mary McLeod Bethune

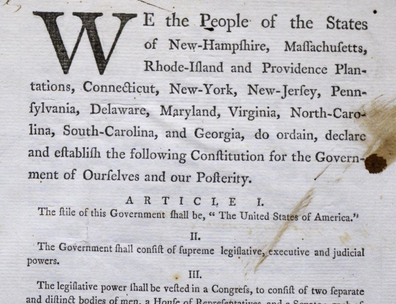

Our Historical Documents

In 1991, Richard Gilder and Lewis Lehrman embarked on a mission to create one of the most important repositories of historical American documents in the country. Today, the Gilder Lehrman Collection contains 86,000+ items documenting the political, social, and economic history of the United States.

Our catalog is free to search . K–12 students, K–12 educators, and parents can access a selection of 7,800+ full-sized images for free. Others can purchase an annual History Resources subscription for $25. Log In Subscribe

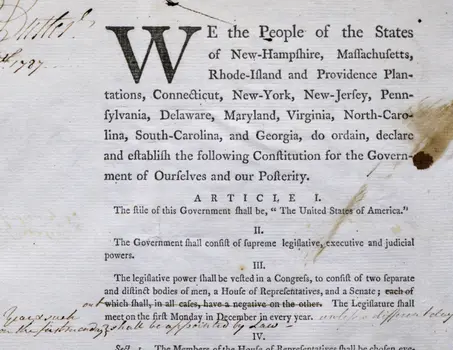

We hold many rare copies of foundational American documents, like this first draft of the US Constitution

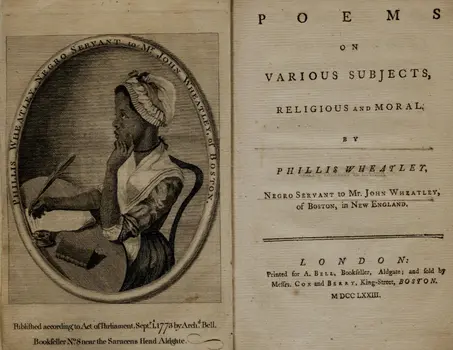

Discover 2,000+ individuals who lived through the American Revolution, like the poet Phillis Wheatley .

Bring history to life with visual sources, like this US War Department recruitment poster (ca. 1944–1945).

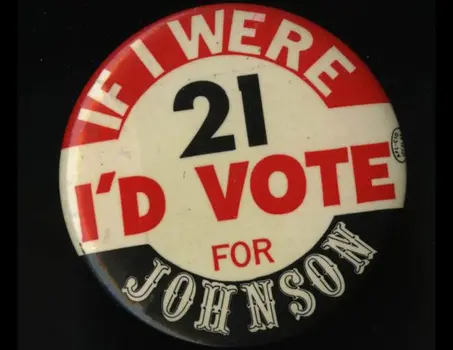

In addition to documents, the Collection includes objects, like this campaign button for Lyndon Johnson .

Our Collection highlights the contributions of many Americans, like those of a female pilot in the 1910s.

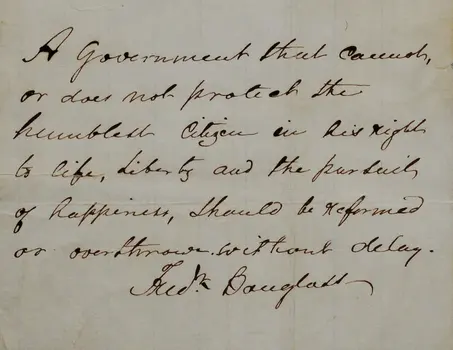

Explore the fight against slavery through abolitionist writings, like this note by Frederick Douglass .

History Now

The Online Journal of the Gilder Lehrman Institute

History Now features essays by the nation’s leading historians and provides the latest in American history scholarship for teachers, students, and general readers.

History Now is completely free for all K-12 students and teachers. Others can purchase a one-year subscription for $25.

Log In Subscribe

Latest Issues

Black Entrepreneurship in America

The Jewish Legacy in American History

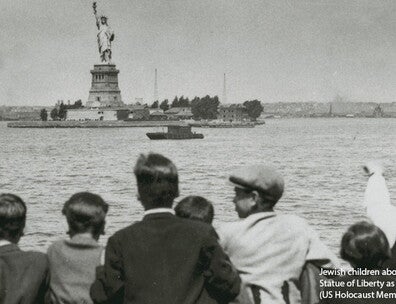

World War II: Portraits of Service

How to research a world war ii veteran.

Learn about the historical research process in this step-by-step guide. As you progress, you will have opportunities to apply what you are learning.

Image : American Servicemen and women in Paris celebrating the unconditional surrender of the Japanese, August 15, 1945 (National Archives, 111-SC-210241)

Stay up to date with all the work that we do to combat historical illiteracy and invigorate the study of the past.

See Our News

Catch up on the highlights from our work with students, teachers, researchers, and the general public.

Read Newsletter

See all official press releases for our important events, significant programs, and special initiatives.

View Press Releases

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

Expository Essay

Expository essay generator.

An expository essay is a quintessential part of academic writing that delves into explaining or clarifying a topic in a comprehensive manner. This type of essay requires the writer to investigate an idea, evaluate evidence, expound on the idea, and set forth an argument concerning that idea in a clear and concise manner. Discovering exemplary essay examples can greatly enhance understanding and mastery of this style. Here, we provide a complete guide with examples to empower students and educators in crafting effective expository essays

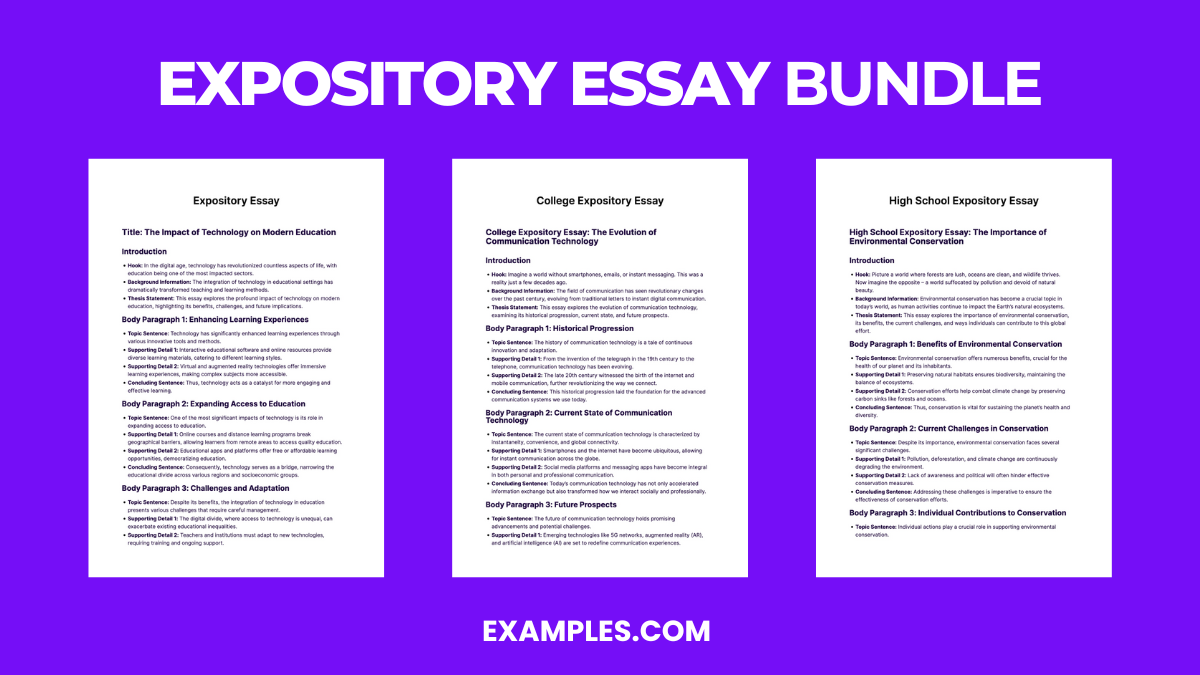

Download Expository Essay Bundle

In school, it is an unavoidable truth that you will be asked to write something about a topic which sometimes you are so eager to finish. There are also times when you feel like you do not want to write anything at all. Well, that is just normal. We all go through those times.One of the things that we do in school is essay writing . As we all know, it is never an easy job to write especially college essays . However, having the right disposition and enthusiasm makes it all so easy. By the time you start to write, all those ideas keep coming and you wouldn’t realize you’re already done.

What is an expository essay?

An expository essay is a genre of writing that investigates an idea, evaluates evidence, expounds on the idea, and sets forth an argument concerning that idea in a clear and concise manner. This type of essay requires the writer to define a topic, use examples, statistics, and facts to explain it to the reader. Expository essays are factual and devoid of the writer’s opinions, focusing instead on delivering straightforward information and analysis on a subject. Their primary purpose is to educate or explain, providing a comprehensive understanding of the topic to the reader.

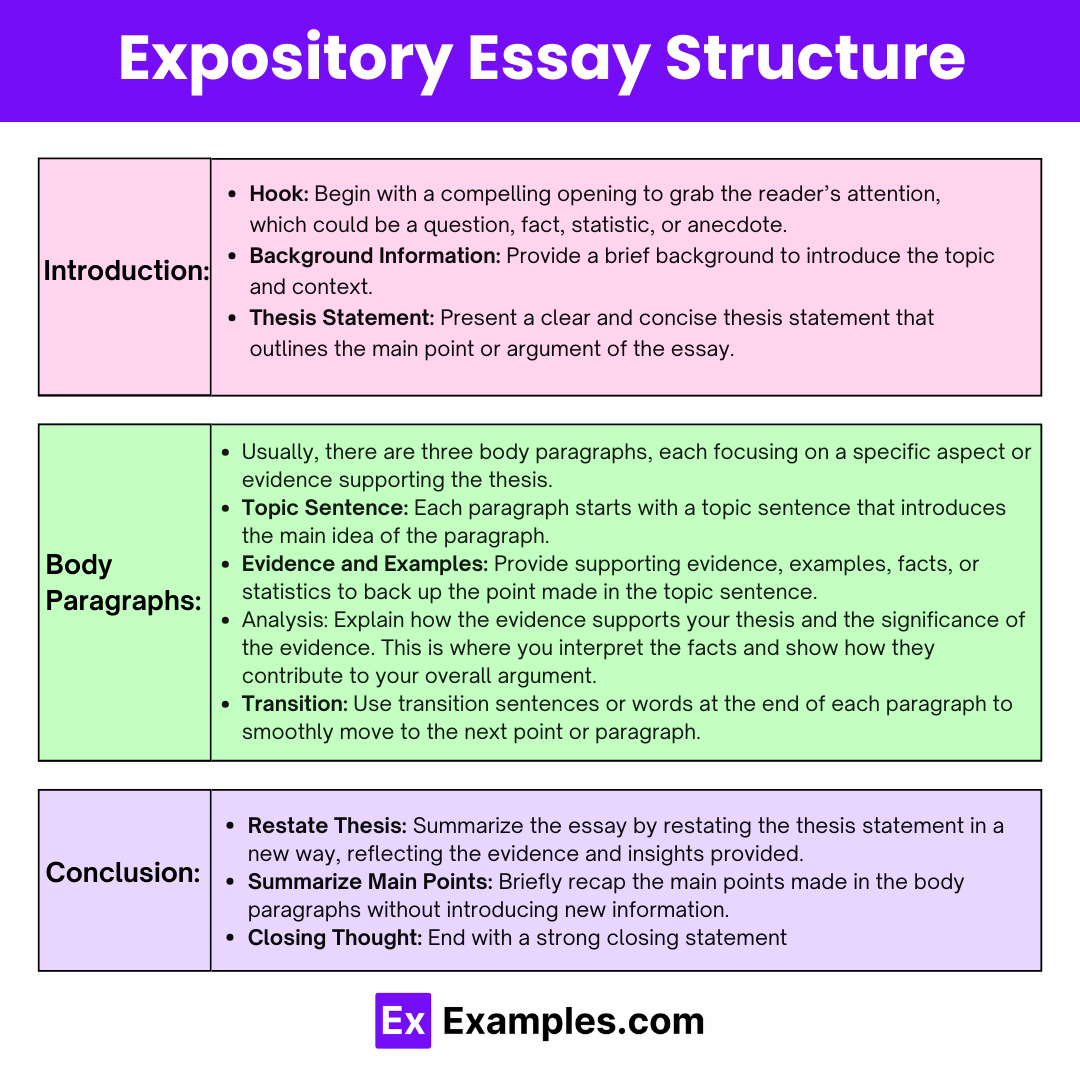

Structure of an Expository Essay

It typically consists of five paragraphs, but the length can vary depending on the depth of the topic. Here’s a breakdown of the traditional structure:

Download This Image

Introduction:

Hook: Begin with a compelling opening to grab the reader’s attention, which could be a question, fact, statistic, or anecdote. Background Information: Provide a brief background to introduce the topic and context. Thesis Statement: Present a clear and concise thesis statement that outlines the main point or argument of the essay.

Body Paragraphs:

Usually, there are three body paragraphs, each focusing on a specific aspect or evidence supporting the thesis. Topic Sentence: Each paragraph starts with a topic sentence that introduces the main idea of the paragraph. Evidence and Examples: Provide supporting evidence, examples, facts, or statistics to back up the point made in the topic sentence. Analysis: Explain how the evidence supports your thesis and the significance of the evidence. This is where you interpret the facts and show how they contribute to your overall argument. Transition: Use transition sentences or words at the end of each paragraph to smoothly move to the next point or paragraph.

Conclusion:

Restate Thesis: Summarize the essay by restating the thesis statement in a new way, reflecting the evidence and insights provided. Summarize Main Points: Briefly recap the main points made in the body paragraphs without introducing new information. Closing Thought: End with a strong closing statement that reinforces the importance of the topic or provides a call to action or thought-provoking statement to leave a lasting impression on the reader.

The primary purpose of expository writing is to explain, inform, or describe. It aims to present a balanced and objective explanation of a topic, process, or concept, based on facts without the writer’s personal opinions influencing the content.

- Educate Readers: It provides readers with a thorough understanding of a subject through clear, concise, and informative content.

- Clarify Complex Ideas: By breaking down complicated subjects into more manageable parts, it helps readers grasp difficult concepts or processes.

- Enhance Critical Thinking: Encourages readers to think critically about the subject matter as they process the information presented.

- Improve Research Skills: Involves researching and presenting facts, which cultivates research and analytical skills in both the writer and the reader.

- Present Objective Analysis: Offers an unbiased perspective, allowing readers to form their own opinions based on the presented facts.

How Do You Write an Expository Essay

Writing an expository essay involves a clear, focused approach that communicates information to the reader in a concise and effective manner. Follow these steps to write a compelling expository essay:

Choose a Topic: Select a topic that is interesting, manageable, and relevant to your assignment’s requirements. It should be broad enough to write about but narrow enough to cover comprehensively in your essay. Conduct Research: Gather information from credible sources to thoroughly understand your topic. Note down important facts, statistics, and examples that will help you explain your topic clearly. Create a Thesis Statement: Develop a clear thesis statement that outlines the main point or argument of your essay. This statement will guide the direction of your essay and inform the reader about your focus. Outline Your Essay: Organize your thoughts and research into an outline. Structure your essay into an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. This will help you maintain a logical flow when writing. Write the First Draft: Using your outline as a guide, write the first draft of your essay. Focus on getting your ideas down; you can refine and edit your work in subsequent drafts. Revise and Edit: Review your essay for clarity and coherence. Ensure each paragraph effectively supports your thesis and that your argument flows logically.Check for grammatical errors, punctuation, and spelling. Ensure that your language is clear, concise, and free of jargon. Cite Your Sources: Properly cite all the sources you used to gather information. This will add credibility to your essay and prevent plagiarism. Finalize Your Essay: Make any necessary revisions based on your review and feedback from others, if available.Ensure your essay meets the assignment criteria and is polished and professional.

Expository Essay Samples

- Essay on Internet

- Essay on Cyber Crime

- Essay on Road Safety

- Essay on National Disaster

- Essay on Floods

- Essay on Education Rules

- Essay on Politics

- Essay on World War 1

- Essay on Cold war

- Essay on Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Expository Essay Examples

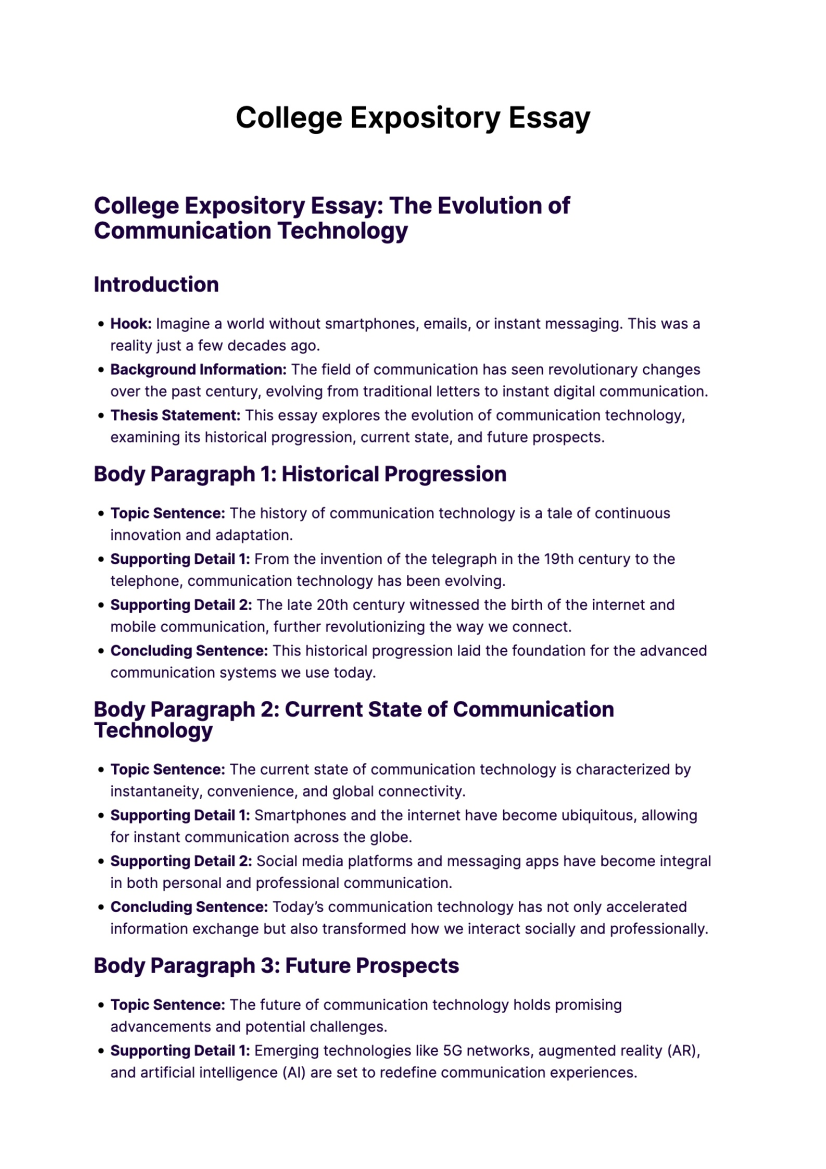

[/ns_col] free download [/ns_row] college expository essay.

Free Download

Fee Download

Essay Format

Short Expository Essay

Expository Essay Sample

Expository Education

College Expository

Basic Expository Essay

High School Expository Essay

Types of Expository Essays

Expository essays are a fundamental aspect of expository writing , encompassing various forms that cater to different academic requirements and personal expressions. Each type serves a unique purpose and requires a specific approach to effectively convey information and ideas.

- Definition Essay This type of essay explores the meaning of a concept or term. It goes beyond the basic dictionary definition, providing deeper insights and personal interpretations. Ideal for exploring abstract concepts, a Definition Essay encourages critical thinking and analytical skills.

- Classification Essay In a Classification Essay, objects or ideas are sorted into categories. This form of essay is particularly useful for organizing complex information into more digestible sections, making it easier for the reader to understand and analyze the topic.

- Process Essay Also known as a “How-To” essay, the Process Essay outlines the steps required to complete a task or procedure. It is sequential and detailed, ensuring the reader can follow along and understand each stage of the process.

- Comparison and Contrast Essay This essay type examines the similarities and differences between two or more subjects. It’s a powerful tool for analysis, helping students develop critical thinking by evaluating various aspects of the subjects being compared.

- Cause and Effect Essay The Cause and Effect Essay delves into the reasons behind a specific event or situation (the cause) and its outcomes (the effect). It’s essential in academic settings for developing a student’s ability to establish logical connections and reason systematically.

- Problem and Solution Essay This essay identifies a problem and proposes one or more solutions. It not only encourages critical thinking but also fosters creativity and problem-solving skills as students explore viable solutions to real-world issues.

Each of these types of expository essays serves as a tool for students and educators to explore and convey complex ideas and information. From high school essays to more advanced academic essays, the ability to effectively write various types of expository essays is a valuable skill in educational development. Whether it’s a personal essay reflecting on individual experiences or a concept essay explaining abstract ideas, mastering these forms equips students with the capability to communicate effectively and think critically

- Tips to Write an Expository Essay

- Choose a Topic That Interests You

- Conduct Thorough Research

- Create a Detailed Outline

- Craft a Strong Thesis Statement

- Use Clear and Concise Language

- Incorporate Evidence and Examples

- Analyze the Evidence

- Follow a Logical Structure

- Write in the Third Person

- Keep Your Writing Objective

- Revise for Clarity and Cohesion

- Edit for Grammar and Spelling Mistakes

- Seek Feedback from Peers or Teachers

- Practice Writing Regularly

Guidelines to Write Expository Essay

Some people find expository writing harder than descriptive writing . Probably because it is at times difficult to present an idea and expand it so the readers can get a grasp of it. Here are a few guidelines you can use.

- Do an intensive research. Oftentimes, the problem with expository writers is that they don’t have enough points to present for the idea. Do your research.

- Widen your vocabulary. It is easier to write when you have the right words to use. You don’t have to browse your dictionary from time to time.

- Design a method. Be a little creative. There may be some methods that people use to write but it is still better if you have one for your own.

Benefits of Expository Essay

Essay writing provides a lot of benefits to students in the academe. Not only it gives them credits from their teachers, it also boosts their confidence in expressing their ideas.

Expository essays provide a better understanding of a certain topic. We cannot avoid that at times, there are things that are presented vaguely making us question what it really means. Expository essay conclusion explains it logically so we can grasp the its true meaning.

Another benefit is expository essays present a fair and balanced analysis of the idea. It eliminates writer’s opinions and emotions just like in a persuasive writing .

When Should You Write an Expository Essay?

- In Academic Assignments: Expository essays are commonly assigned in academic settings to assess students’ understanding and ability to explain complex concepts clearly.

- For Standardized Tests: Many standardized tests include expository writing sections that require candidates to organize and express their thoughts on a given topic.

- When Explaining Processes: Whenever there’s a need to describe how something works or the steps in a process, an expository essay format is ideal for providing clear instructions.

- To Clarify Concepts: Use an expository essay to break down difficult concepts or ideas into understandable parts for educational purposes or to inform a general audience.

- In Professional Settings: Professionals might write expository essays in the form of reports, manuals, or proposals to convey information or explain procedures within a company.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Define an expository essay and its main objective

Outline the structure of a standard expository essay.

Describe the process of selecting a topic for an expository essay.

Explain the importance of research in expository essay writing.

Analyze the role of the thesis statement in expository essays

Discuss the differences between expository and narrative essays

Examine techniques for developing paragraphs in expository essays

Explain how to effectively conclude an expository essay

Describe methods for maintaining objectivity in expository writing

Analyze the impact of audience on expository essay content

Search form

Department of history.

Make a Gift

- Robert D. Cross Memorial Lecture Series

- Faculty Resources

- Emeritus Faculty

- Affiliated Faculty

- Graduate Students

- Department Staff

- Department Contacts

- Office Hours

- The PhD Program

- Fields of Study

- How to Apply

- Our Students

- Placement History

- Department Forms

- Distinguished Majors Program

- Research Opportunities & Awards

- Transfer Credit

- History Teachers Education

- Graduation Details

- Concentrations

- History Internship Program

Publications

- The Caribbean

- Europe & Russia

- Global & International

- Latin America

- The Middle East

- US & Canada

- Ancient & Classical (pre-500)

- Medieval & Post-Classical (c.500-1400)

- Early Modern (c.1400-1800)

- 19th Century

- 20th Century

- Cultural & Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Economic History & History of Capitalism

- Empires & Colonialism

- Environmental History

- Genocide & Violence

- History of Slavery

- Intellectual History & History of Ideas

- Jewish History

- Labor History

- Legal History

- Material Culture

- Military & War History

- Political History

- Race & Ethnicity

- Religious History

- Science, Medicine, & Technology

- Spatial History, Frontiers, & Migration

- Transnational & Diplomatic History

- Women, Gender, & Sexuality

- History Course Concentrations per Semester

- Spring 2025

- Spring 2024

- Spring 2023

- Previously Offered Courses

- Full Course Catalog

Postdoctoral Research Associate Justin McBrien writes for TIME

Postdoctoral Research Associate Justin McBrien has written an article for TIME that shows Hurricane Helene's damage is not unprecedented and "How America Forgot a Crucial Lesson From Hurricane Disasters of the Past".

https://time.com/7072620/hurricane-lesson-helene-camille-history/

Postdoctoral Research Associate Justin McBrien has written an article for TIME that shows Hurricane Helene's damage is not unprecedented and "How America Forgot a Crucial Lesson From Hurricane Disa

Congratulations to PhD Crystal Luo for Best Dissertation

Congratulations to recent UVA Department of History PhD Crystal Luo for receiving the best dissertation award from the Urban History Association.

Please click HERE for more infomation.

Welcome the Visiting Associate Professor Melissa Vise

Please welcome our new Visiting Associate Professor, Melissa Vise!

Vise received her Ph.D. from Northwestern University in medieval and early modern history (2015) and her master’s in theological studies from the University of Notre Dame (2008).

She has written articles for the Speculum , Viator and American Journal for Legal History. She also has a book release, The Unruly Tongue: Speech and Violence in Medieval Italy (University of Pennsylvania Press), scheduled for January 2025.

Full profile can be read here: https://as.virginia.edu/faculty-profile/melissa-vise

Professor Joseph Seeley selected for the 2024-2025 U.S.-Korea NextGen Scholars Program

Congratulations to Professor Joseph Seeley, who was selected for the 2024-2025 U.S.-Korea NextGen Scholars Program.

An initiative by the CSIS Office of the Korea Chair and the USC Korean Studies Institute with support from The Korea Foundation to help mentor the next generation of Korea specialists in the United States.

These scholars were selected in a national competition. The scholars all displayed exemplary scholarship in wide-rangingdisciplines, from American studies, ethnomusicology, history, political science, philosophy, to international relations.

Learn more about the program here: https://www.csis.org/programs/korea-chair/projects/us-korea-nextgen-scholars-program

The Long 1989

Decades of global revolution.

How Athens, Georgia Launched the Alternative Scene and Changed American Culture

The Cigarette

A political history.

Petersburg to Appomattox

The end of the war in virginia.

To the End of Revolution

The chinese communist party and tibet, 1949–1959.

Lens of War

Exploring iconic photographs of the civil war.

The Associational State

American governance in the twentieth century.

Discovering Tuberculosis

A global history, 1900 to the present.

Enlightenment Underground

Radical germany, 1680-1720.

Cold Harbor to the Crater The End of the Overland Campaign

Ruling Minds

Psychology in the british empire.

Causes Won and Lost

The end of the civil war.

The American War

A history of the civil war era.

Shaper Nations

Strategies for a changing world.

When Sunday Comes

Gospel music in the soul and hip-hop eras.

Confronting Saddam Hussein

George w. bush and the invasion of iraq.

The Age of Eisenhower

America and the world in the 1950s.

Performing Filial Piety in Northern Song China

Family, state, and native place.

Rooted Cosmopolitans

Jews and human rights in the twentieth century.

Piracy and Law in the Ottoman Mediterranean

Singing the Resurrection

Body, community, and belief in reformation europe.

A Sea of Debt

Law and economic life in the western indian ocean, 1780-1950.

Armies of Deliverance

A new history of the civil war.

The Law of Strangers

Jewish lawyers and international law in the twentieth century.

To Build a Better World

Choices to end the cold war and create a global commonwealth.

Unfree Marks: The Slaves' Economy and the Rise of Capitalism in South Carolina

Ghosts From the Past?

Assessing recent developments in religious freedom in south asia.

That Tyrant, Persuasion

How rhetoric shaped the roman world.

The Unsettled Plain

An environmental history of the late ottoman frontier.

The Man Who Understood Democracy

The life of alexis de tocqueville.

Paradoxes of Nostalgia

Cold war triumphalism and global disorder since 1989.

The New Era In American Mathematics, 1920-1950

Hurt Sentiments

Secularism and belonging in south asia.

Communism's Public Sphere

The Japanese Ideology

A marxist critique of liberalism and fascism.

The War That Made America

Essays inspired by the scholarship of gary w. gallagher.

The Black Tax

150 years of theft, exploitation and dispossession in america.

In the Pines

A lynching, a lie, a reckoning.

A Very Short Introduction

Not In My Backyard

How citizen activists nationalized local politics in the fight to save green springs.

Citizenship, Belonging, and the Partition of India

Chinese Autobiographical Writing

An anthology of personal accounts.

Age of Emergency

Living with violence at the end of the british empire.

Culture as Politics in Cold War Poland and East Germany

Border of Water and Ice

The yalu river and japan's empire in korea and manchuria.

Savings and Trust

The rise and betrayal of freedman's bank, corcoran department of history.

The University of Virginia's Corcoran Department of History has long been one of the anchors for liberal and humane education in the College of Arts & Sciences. Members of the Department are nationally and internationally recognized for their scholarship and teaching. As scholars, the faculty specialize in a wide range of disciplines — cultural, diplomatic, economic, environmental history, history of science & technology, intellectual, legal, military, political, public history, and social history. Areas of interest span the globe from Africa, to East Asia, Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, South Asia, and the United States. As teachers, our faculty seek above all to lead students to reflect more deeply on the role historical forces and processes play in the human condition. Offering over 100 courses a year, the faculty teach introductory surveys as well as seminars and colloquia to undergraduates and graduate students. The Department's intellectual breadth is enhanced by its close relationship with the Carter G. Woodson Institute for African-American & African Studies , the Center for Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies (CREEES) , the Classics Department , an emerging Law & History nexus between the Department and the School of Law , the Miller Center for Study of the American Presidency, and the Committee on the History of Environment, Science, and Technology (CHEST) . Members of the Department are also closely involved with several interdisciplinary programs in the College of Arts & Sciences such as, American Studies , Latin American Studies , Middle-Eastern Studies , Medieval Studies Program , and Women, Gender, & Sexuality Studies . Others work at the convergence of humanities and digital technology, both in research and in novel approaches to historical pedagogy.

Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

How to Write a Great College Essay, Step-by-Step

College Admissions , College Essays

Writing your personal statement for your college application is an undeniably overwhelming project. Your essay is your big shot to show colleges who you are—it's totally reasonable to get stressed out. But don't let that stress paralyze you.

This guide will walk you through each step of the essay writing process to help you understand exactly what you need to do to write the best possible personal statement . I'm also going to follow an imaginary student named Eva as she plans and writes her college essay, from her initial organization and brainstorming to her final edits. By the end of this article, you'll have all the tools you need to create a fantastic, effective college essay.

So how do you write a good college essay? The process starts with finding the best possible topic , which means understanding what the prompt is asking for and taking the time to brainstorm a variety of options. Next, you'll determine how to create an interesting essay that shows off your unique perspective and write multiple drafts in order to hone your structure and language. Once your writing is as effective and engaging as possible, you'll do a final sweep to make sure everything is correct .

This guide covers the following steps:

#1: Organizing #2: Brainstorming #3: Picking a topic #4: Making a plan #5: Writing a draft #6: Editing your draft #7: Finalizing your draft #8: Repeating the process

Step 1: Get Organized

The first step in how to write a college essay is figuring out what you actually need to do. Although many schools are now on the Common App, some very popular colleges, including Rutgers and University of California, still have their own applications and writing requirements. Even for Common App schools, you may need to write a supplemental essay or provide short answers to questions.

Before you get started, you should know exactly what essays you need to write. Having this information allows you to plan the best approach to each essay and helps you cut down on work by determining whether you can use an essay for more than one prompt.

Start Early

Writing good college essays involves a lot of work: you need dozens of hours to get just one personal statement properly polished , and that's before you even start to consider any supplemental essays.

In order to make sure you have plenty of time to brainstorm, write, and edit your essay (or essays), I recommend starting at least two months before your first deadline . The last thing you want is to end up with a low-quality essay you aren't proud of because you ran out of time and had to submit something unfinished.

Determine What You Need to Do

As I touched on above, each college has its own essay requirements, so you'll need to go through and determine what exactly you need to submit for each school . This process is simple if you're only using the Common App, since you can easily view the requirements for each school under the "My Colleges" tab. Watch out, though, because some schools have a dedicated "Writing Supplement" section, while others (even those that want a full essay) will put their prompts in the "Questions" section.

It gets trickier if you're applying to any schools that aren't on the Common App. You'll need to look up the essay requirements for each college—what's required should be clear on the application itself, or you can look under the "how to apply" section of the school's website.

Once you've determined the requirements for each school, I recommend making yourself a chart with the school name, word limit, and application deadline on one side and the prompt or prompts you need to respond to on the other . That way you'll be able to see exactly what you need to do and when you need to do it by.

The hardest part about writing your college essays is getting started.

Decide Where to Start

If you have one essay that's due earlier than the others, start there. Otherwise, start with the essay for your top choice school.

I would also recommend starting with a longer personal statement before moving on to shorter supplementary essays , since the 500-700 word essays tend to take quite a bit longer than 100-250 word short responses. The brainstorming you do for the long essay may help you come up with ideas you like for the shorter ones as well.

Also consider whether some of the prompts are similar enough that you could submit the same essay to multiple schools . Doing so can save you some time and let you focus on a few really great essays rather than a lot of mediocre ones.

However, don't reuse essays for dissimilar or very school-specific prompts, especially "why us" essays . If a college asks you to write about why you're excited to go there, admissions officers want to see evidence that you're genuinely interested. Reusing an essay about another school and swapping out the names is the fastest way to prove you aren't.

Example: Eva's College List

Eva is applying early to Emory University and regular decision to University of Washington, UCLA, and Reed College. Emory, the University of Washington, and Reed both use the Common App, while University of Washington, Emory, and Reed all use the Coalition App.

Even though she's only applying to four schools, Eva has a lot to do: two essays for UW, four for the UCLA application, one for the Common App (or the Coalition App), and two essays for Emory. Many students will have fewer requirements to complete, but those who are applying to very selective schools or a number of schools on different applications will have as many or even more responses to write.

Eva's first deadline is early decision for Emory, she'll start by writing the Common App essay, and then work on the Emory supplements. (For the purposes of this post, we'll focus on the Common App essay.)

Pro tip: If this sounds like a lot of work, that's because it is. Writing essays for your college applications is demanding and takes a lot of time and thought. You don't have to do it alone, though. PrepScholar has helped students like you get into top-tier colleges like Stanford, Yale, Harvard, and Brown. Our essay experts can help you craft amazing essays that boost your chances of getting into your dream school .

Step 2: Brainstorm

Next up in how to write a college essay: brainstorming essay ideas. There are tons of ways to come up with ideas for your essay topic: I've outlined three below. I recommend trying all of them and compiling a list of possible topics, then narrowing it down to the very best one or, if you're writing multiple essays, the best few.

Keep in mind as you brainstorm that there's no best college essay topic, just the best topic for you . Don't feel obligated to write about something because you think you should—those types of essays tend to be boring and uninspired. Similarly, don't simply write about the first idea that crosses your mind because you don't want to bother trying to think of something more interesting. Take the time to come up with a topic you're really excited about and that you can write about in detail.

Analyze the Prompts

One way to find possible topics is to think deeply about the college's essay prompt. What are they asking you for? Break them down and analyze every angle.

Does the question include more than one part ? Are there multiple tasks you need to complete?

What do you think the admissions officers are hoping to learn about you ?

In cases where you have more than one choice of prompt, does one especially appeal to you ? Why?

Let's dissect one of the University of Washington prompts as an example:

"Our families and communities often define us and our individual worlds. Community might refer to your cultural group, extended family, religious group, neighborhood or school, sports team or club, co-workers, etc. Describe the world you come from and how you, as a product of it, might add to the diversity of the UW. "

This question is basically asking how your personal history, such as your childhood, family, groups you identify with etc. helped you become the person you are now. It offers a number of possible angles.

You can talk about the effects of either your family life (like your relationship with your parents or what your household was like growing up) or your cultural history (like your Jewish faith or your Venezuelan heritage). You can also choose between focusing on positive or negative effects of your family or culture. No matter what however, the readers definitely want to hear about your educational goals (i.e. what you hope to get out of college) and how they're related to your personal experience.

As you try to think of answers for a prompt, imagine about what you would say if you were asked the question by a friend or during a get-to-know-you icebreaker. After all, admissions officers are basically just people who you want to get to know you.

The essay questions can make a great jumping off point, but don't feel married to them. Most prompts are general enough that you can come up with an idea and then fit it to the question.

Consider Important Experiences, Events, and Ideas in Your Life

What experience, talent, interest or other quirk do you have that you might want to share with colleges? In other words, what makes you you? Possible topics include hobbies, extracurriculars, intellectual interests, jobs, significant one-time events, pieces of family history, or anything else that has shaped your perspective on life.

Unexpected or slightly unusual topics are often the best : your passionate love of Korean dramas or your yearly family road trip to an important historical site. You want your essay to add something to your application, so if you're an All-American soccer player and want to write about the role soccer has played in your life, you'll have a higher bar to clear.

Of course if you have a more serious part of your personal history—the death of a parent, serious illness, or challenging upbringing—you can write about that. But make sure you feel comfortable sharing details of the experience with the admissions committee and that you can separate yourself from it enough to take constructive criticism on your essay.

Think About How You See Yourself

The last brainstorming method is to consider whether there are particular personality traits you want to highlight . This approach can feel rather silly, but it can also be very effective.

If you were trying to sell yourself to an employer, or maybe even a potential date, how would you do it? Try to think about specific qualities that make you stand out. What are some situations in which you exhibited this trait?

Example: Eva's Ideas

Looking at the Common App prompts, Eva wasn't immediately drawn to any of them, but after a bit of consideration she thought it might be nice to write about her love of literature for the first one, which asks about something "so meaningful your application would be incomplete without it." Alternatively, she liked the specificity of the failure prompt and thought she might write about a bad job interview she had had.

In terms of important events, Eva's parents got divorced when she was three and she's been going back and forth between their houses for as long as she can remember, so that's a big part of her personal story. She's also played piano for all four years of high school, although she's not particularly good.

As for personal traits, Eva is really proud of her curiosity—if she doesn't know something, she immediately looks it up, and often ends up discovering new topics she's interested in. It's a trait that's definitely come in handy as a reporter for her school paper.

Step 3: Narrow Down Your List

Now you have a list of potential topics, but probably no idea where to start. The next step is to go through your ideas and determine which one will make for the strongest essay . You'll then begin thinking about how best to approach it.

What to Look for in a College Essay Topic

There's no single answer to the question of what makes a great college essay topic, but there are some key factors you should keep in mind. The best essays are focused, detailed, revealing and insightful, and finding the right topic is vital to writing a killer essay with all of those qualities.

As you go through your ideas, be discriminating—really think about how each topic could work as an essay. But don't be too hard on yourself ; even if an idea may not work exactly the way you first thought, there may be another way to approach it. Pay attention to what you're really excited about and look for ways to make those ideas work.

Consideration 1: Does It Matter to You?

If you don't care about your topic, it will be hard to convince your readers to care about it either. You can't write a revealing essay about yourself unless you write about a topic that is truly important to you.

But don't confuse important to you with important to the world: a college essay is not a persuasive argument. The point is to give the reader a sense of who you are , not to make a political or intellectual point. The essay needs to be personal.

Similarly, a lot of students feel like they have to write about a major life event or their most impressive achievement. But the purpose of a personal statement isn't to serve as a resume or a brag sheet—there are plenty of other places in the application for you to list that information. Many of the best essays are about something small because your approach to a common experience generally reveals a lot about your perspective on the world.

Mostly, your topic needs to have had a genuine effect on your outlook , whether it taught you something about yourself or significantly shifted your view on something else.

Consideration 2: Does It Tell the Reader Something Different About You?

Your essay should add something to your application that isn't obvious elsewhere. Again, there are sections for all of your extracurriculars and awards; the point of the essay is to reveal something more personal that isn't clear just from numbers and lists.

You also want to make sure that if you're sending more than one essay to a school—like a Common App personal statement and a school-specific supplement—the two essays take on different topics.

Consideration 3: Is It Specific?

Your essay should ultimately have a very narrow focus. 650 words may seem like a lot, but you can fill it up very quickly. This means you either need to have a very specific topic from the beginning or find a specific aspect of a broader topic to focus on.

If you try to take on a very broad topic, you'll end up with a bunch of general statements and boring lists of your accomplishments. Instead, you want to find a short anecdote or single idea to explore in depth .