Music education sets up low-income youth for success

Should cell phones be banned from all California schools?

New school year brings new education laws

How earning a college degree put four California men on a path from prison to new lives | Documentary

Patrick Acuña’s journey from prison to UC Irvine | Video

Family reunited after four years separated by Trump-era immigration policy

Getting Students Back to School

Calling the cops: Policing in California schools

Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in Higher Education: California and Beyond

Superintendents: Well paid and walking away

Keeping California public university options open

August 28, 2024

Getting students back to school: Addressing chronic absenteeism

July 25, 2024

Adult education: Overlooked and underfunded

Nutrition education can be a game-changer for our youth

Elizabeth Falkner

August 22, 2022.

I’m fortunate to spend most of my time around good food. It’s both my job and my passion.

Growing up in Los Angeles, cooking at home with my mom had a big influence on me and started my lifelong love affair with food. My fondest memories include the school lunches my mom packed for us — a peanut butter sandwich on hearty sourdough bread — no jelly and no mushy white bread for the future chef and baker. There was always a piece of fruit, like an apple or an orange or sometimes celery or carrots. And of course, a homemade cookie, which sparked my interest in making better desserts.

Mom was the head dietitian for the Las Virgenes Unified School District where I attended school. She talked about how tight the state budgets were back in the 1990s into the early 2000s and worked hard at keeping sugar-loaded sodas out of schools and pushed to have salad bars.

It wasn’t until later in my culinary career that I began a deeper exploration into the correlation between nutrition and the impact it can have on overall health.

Today, there is a stronger general understanding of how the foods we put in our bodies impact our physical health. We know healthy eating is a key contributor to energy levels and social-emotional development. There is science behind being hangry . Still, studies have shown that over 40% of daily calories consumed by children ages 2-18 are empty, or lacking in any nutrition. Poor nutrition has a significant impact on a child’s ability to focus and can lower cognitive function, which is so important when it comes to learning in school, widening many of the equity gaps that exist particularly in our most underserved communities.

Further, every year, an alarming number of children are diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes, obesity and other chronic health-related issues, most of which become lifelong battles. According to the CDC, more than 40% of fourth and seventh graders in our state are considered either overweight or obese. Research has conclusively shown that youth living in underresourced communities have 2.31 times greater odds of being affected by obesity than children living in higher-income homes and are likely to face greater health care challenges than their more affluent peers.

One way to address this gap in nutrition equity is through improved nutrition education in our schools.

I have been a chef activist my entire career, raising money and awareness for many causes, and some of the most important ones to me are the organizations that create change for the future of food. For decades, California has worked to improve eating habits by offering healthier foods on school menus. Yet this is not the stand-alone solution that will drive change in lifelong behavior. Providing access to healthier food options coupled with integrating nutrition education in our school curriculum starting from an early age can equip our youth with knowledge to make better food choices, setting them up to live healthier lives.

We have a generation-changing opportunity to prioritize inclusive nutrition education in our schools to bridge the nutrition equity gap in California because every child should have the resources to eat healthily and learn how food impacts overall wellness. There are cost-effective ways to implement nutrition education in our schools by partnering with nonprofits that already have a good record of working in this area. Since 2008, Common Threads has taught over 130,000 Angelenos and provided more than 1.4 million hours of nutrition education for children, their parents, teachers, and families. Before the pandemic, the organization’s programming was present in over 200 schools throughout the Los Angeles region, helping young people learn about nutrition, how to make healthy meals and the importance of developing lifelong healthy eating habits. At many schools, these efforts complemented existing school activities like Glenfeliz Boulevard Elementary School’s farm-to-table gardening program , so students in the heart of LA can develop a hands-on relationship with food from the source.

Sadly, many of these kinds of programs were halted during the pandemic with school closures. As we near the new school year, it’s imperative that we prioritize the importance of nutrition education in our schools and the value of this kind of programming.

It will be an amazing day when all children who grow up in California, a state that leads in healthy food movements, in tech, and is always ahead in policy, can invest in solutions that help close the nutrition equity gap and build inclusive education in our schools that empowers youth and families to make nutritious food choices.

Elizabeth Falkner is a chef, restaurateur and advocate for nutrition equity in Los Angeles.

The opinions in this commentary are those of the author. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us .

Share Article

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. required fields are marked * *.

Click here to cancel reply.

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy .

EdSource Special Reports

California School Dashboard lacks pandemic focus, earns a D grade in report

The California School Dashboard makes it hard for the public to see how schools and districts are performing over multiple years, concludes the report’s lead author.

Communication with parents is key to addressing chronic absenteeism, panel says

Low-cost, scalable engagement through texting and post cards can make a huge difference in getting students back in the habit of attending classes.

Helping students with mental health struggles may help them return to school

In California, 1 in 4 students are chronically absent putting them academically behind. A new USC study finds links between absenteeism and mental health struggles.

Millions of kids are still skipping school. Could the answer be recess — and a little cash?

Data gathered from over 40 states shows absenteeism improved slightly but remains above pre-pandemic levels. School leaders are trying various strategies to get students back to school.

EdSource in your inbox!

Stay ahead of the latest developments on education in California and nationally from early childhood to college and beyond. Sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email.

Stay informed with our daily newsletter

- Skip to main content

- Skip to FDA Search

- Skip to in this section menu

- Skip to footer links

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- Search

- Menu

- Food Labeling & Nutrition

Nutrition Education Resources & Materials

Resources on the importance of good nutrition.

The Nutrition Facts Label

The Nutrition Facts label reflects current scientific information, including the link between diet and chronic diseases such as obesity and heart disease. The label makes it easier for you and your audience to make more informed food choices.

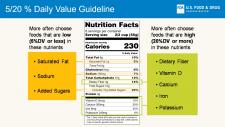

Learn about What’s on the Nutrition Facts Label , including details on: Calories, Serving Sizes, Added Sugars, and Percent Daily Value.

Industry members, read more about the changes to the Nutrition Facts label requirements .

More on the Nutrition Facts Label

How to Understand and Use the Nutrition Facts Label Learn how to use this information more effectively and easily.

Interactive Nutrition Facts Label An interactive way to learn about the Nutrition Facts label and discover the wealth of information it contains.

For Educators

Health Educator’s Nutrition Toolkit Teach your audience how to use the Nutrition Facts label and to make informed choices.

"Behind the Label” with FDA Information for Educators View this video for health educators that explains the changes to the Nutrition Facts label.

For Youth & Youth Educators

Read the Label Use these hands-on materials to challenge kids and families to look for and use the Nutrition Facts label.

Science and Our Food Supply | Curriculum for Middle/High School Teachers Introduce students to the fundamentals of informed food choices with this nutrition-based curriculum.

Whyville Snack Shack Games Kids can play two fun games that test their knowledge about using the Nutrition Facts label to make healthy snack choices.

For Older Adults

A How-To Guide for Older Adults Good nutrition can help older adults feel their best and stay strong. It can also help lower the risk of developing some health conditions that are common among older adults.

For Physicians & Healthcare Professionals

Physicians' Continuing Medical Education Program Resources for talking to patients about using the Nutrition Facts label to make healthy food choices.

Pediatricians' Continuing Medical Education Program Resources for talking to parents and patients about using the Nutrition Facts label to make healthy food choices.

More on Labeling

Gluten-Free Labeling Learn how gluten-free labeling can help your audience manage health and dietary intake — especially those with celiac disease.

Calories on the Menu | Menu Labeling Information Find out how calorie labeling on menus can help your community make informed and healthful decisions about meals and snacks.

Sodium | Look at the Label Learn the basics on sodium’s health effects, how-to’s for using the Nutrition Facts label to reduce sodium intake, and more.

Using the Nutrition Facts Label to Choose Milk and Plant-Based Beverages Use the Nutrition Facts Label to compare the nutrient content of different products to help you make the best choices for you and your family when choosing milk and plant-based beverages.

CFSAN Education Resource Library

FDA's Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) has a wealth of nutrition education materials.

Consumers, educators, teachers, dietitians, and health professionals are invited to explore CFSAN’s Education Resource Library – a catalog of downloadable and printable materials and videos on nutrition (including labeling and dietary supplements), food safety, and cosmetics.

Education Newsletter

Get regular FDA email updates delivered on this topic to your inbox.

Healthy Food Choices in Schools

3 Ways Nutrition Influences Student Learning Potential and School Performance

Advocates of child health have experimented with students’ diets in the United States for more than twenty years. Initial studies focused on benefits of improving the health of students are apparent. Likewise, improved nutrition has the potential to positively influence students’ academic performance and behavior.

Though researchers are still working to definitively prove the link, existing data suggests that with better nutrition students are better able to learn, students have fewer absences, and students’ behavior improves, causing fewer disruptions in the classroom. [1]

Improve Nutrition to Increase Brain Function

Several studies show that nutritional status can directly affect mental capacity among school-aged children. For example, iron deficiency, even in early stages, can decrease dopamine transmission, thus negatively impacting cognition. [2] Deficiencies in other vitamins and minerals, specifically thiamine, vitamin E, vitamin B, iodine, and zinc, are shown to inhibit cognitive abilities and mental concentration. [3] Additionally, amino acid and carbohydrate supplementation can improve perception, intuition, and reasoning. [4] There are also a number of studies showing that improvements in nutrient intake can influence the cognitive ability and intelligence levels of school-aged children. [5]

Provide a Balanced Diet for Better Behaviors and Learning Environments

Good Nutrition helps students show up at school prepared to learn. Because improvements in nutrition make students healthier, students are likely to have fewer absences and attend class more frequently. Studies show that malnutrition leads to behavior problems [6] , and that sugar has a negative impact on child behavior. [7] However, these effects can be counteracted when children consume a balanced diet that includes protein, fat, complex carbohydrates, and fiber. Thus students will have more time in class, and students will have fewer interruptions in learning over the course of the school year. Additionally, students’ behavior may improve and cause fewer disruptions in the classroom, creating a better learning environment for each student in the class.

Promote Diet Quality for Positive School Outcomes

Sociologists and economists have looked more closely at the impact of a student’s diet and nutrition on academic and behavioral outcomes. Researchers generally find that a higher quality diet is associated with better performance on exams, [8] and that programs focused on increasing students’ health also show modest improvements in students’ academic test scores. [9] Other studies find that improving the quality of students’ diets leads to students being on task more often, increases math test scores, possibly increases reading test scores, and increases attendance. [10] Additionally, eliminating the sale of soft drinks in vending machines in schools and replacing them with other drinks had a positive effect on behavioral outcomes such as tardiness and disciplinary referrals. [11]

Every student has the potential to do well in school. Failing to provide good nutrition puts them at risk for missing out on meeting that potential. However, taking action today to provide healthier choices in schools can help to set students up for a successful future full of possibilities.

Contributor

David Just Phd- Cornell Center for Behavioral Economics in Child Nutrition Programs

[1] Sorhaindo, A., & Feinstein, L. (2006). What is the relationship between child nutrition and school outcomes. Wider Benefits of Learning Research Report No.18. Centre for Research on the Wider Benefits of Learning

[2] Pollitt E. (1993). Iron deficiency and cognitive function. Annual Review of Nutrition, 13, 521–537.

[3] Chenoweth, W. (2007). Vitamin B complex deficiency and excess. In R. Kliegman, H. Jenson, R. Behrman, & B. Stanton (Eds.), Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 18 th edition . Philadelphia: Saunders.

Greenbaum, L. (2007a). Vitamin E deficiency. In R. Kliegman, H. Jenson, R. Behrman, & B. Stanton (Eds.), Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 18 th Edition . Philadelphia: Saunders.

Greenbaum, L. (2007b). Micronutrient mineral deficiencies. In R. Kliegman, H. Jenson, R. Behrman, & B. Stanton (Eds.), Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 18 th Edition . Philadelphia: Saunders.

Bryan, J., Osendarp, S., Hughes, D., Calvaresi, E., Baghurst, K. & van Klinken, J. (2004). Nutrients for cognitive development in school-aged children. Nutrition Reviews, 62 (8), 295–306.

Delange, F. (2000) The role of iodine in brain development. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 59 , 75–79. Sandstead, H. (2000). Causes of iron and zinc deficiencies and their effects on brain. Journal of Nutrition, 130 , 347–349.

[4] Lieberman, H. (2003). Nutrition, brain function, and cognitive performance. Appetite, 40, 245–254.

Frisvold, D. (2012). Nutrition and cognitive achievement: An evaluation of the school breakfast program. Working Paper, Emory University.

[5] Benton, D. & Roberts, G. (1988). Effect of vitamin and mineral supplementation on intelligence in a sample of schoolchildren. The Lancet, 1, 140–143.

Schoenthaler, S., Amos, S., Doraz, W., Kelly, M., & Wakefield, J. (1991). Controlled trial of vitamin – mineral supplementation on intelligence and brain function. Personality and Individual Differences, 12, 343–350.

Benton, D. & Buts, J. (1990). Vitamins/mineral supplementation and intelligence. The Lancet, 335, 1158–1160.

Nelson, M. (1992) Vitamin and mineral supplementation and academic performance in schoolchildren. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 51, 303–313.

Eysenck, H., & Schoenthaler, S. (1997). Raising IQ level by vitamin and mineral supplementation. In R. Sternberg and E. Grigorenko (Eds.), Intelligence, heredity and environment (pp. 363 – 392). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[6] Kleinman, R., Murphy, J., Little, M., Pagano, M., Wehler, C., Regal, K., & Jellinek, M. (1998) Hunger in children in the United States: Potential behavioral and emotional correlates. Pediatrics, 101(1), e3.

[7] Jones, T., Borg, W., Boulware, S., McCarthy, G., Sherwin, R., Tamborlane, W. (1995). Enhanced adrenomedullary response and increased susceptibility to neuroglygopenia: Mechanisms underlying the adverse effect of sugar ingestion in children. Journal of Pediatrics, 126, 171–177.

[8] Florence, M., Asbridge, M., & Veugelers, P. (2008). Diet quality and academic performance. Journal of School Health, 78, 209–215.

[9] Meyers, A., Sampson, A., Wietzman, M., Rogers, B., & Kayne, H. (1989). School breakfast program and school performance. American Journal of Diseases of Children, 143, 1234–1239.

Kleinman, R., Murphy, J., Little, M., Pagano, M., Wehler, C., Regal, K., & Jellinek, M. (1998) Hunger in children in the United States: Potential behavioral and emotional correlates. Pediatrics, 101(1), e3.

[10] Powell, C., Walker, S., Chang, S., & Grantham-McGregor, S. (1998). Nutrition and education: A randomized trial of the effects of breakfast in rural primary school children. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 68, 873–879.

Cueto, S. (2001). Breakfast and dietary balance: The enKid study. Public Health Nutrition, 4, 1429–1431.

Storey, H., Pearce, J., Ashfield-Watt, P., Wood, L., Baines, E., & Nelson, M. (2011). A randomized controlled trial of the effect of school food and dining room modifications on classroom behaviour in secondary school children. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 65, 32–38.

Hollar, D., Messiah, S., Lopez-Mitnik, G., Hollar, T., Almon, M., & Agatston, A. (2010). Effect of a two-year obesity prevention intervention on percentile changes in body mass index and academic performance in low income elementary school children. American Journal of Public Health, 100(4), 646–653.

[11] Price, J. (2012). De-fizzing schools: The effect on student behavior of having vending machines in schools. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review, 41(1), 92–99.

- NAEYC Login

- Member Profile

- Hello Community

- Accreditation Portal

- Online Learning

- Online Store

Popular Searches: DAP ; Coping with COVID-19 ; E-books ; Anti-Bias Education ; Online Store

You are here

Most recent.

Meal Kits as a Strengths-Based Practice in the Mississippi Delta

Authored by.

Healthy Young Children, Sixth Edition

Ask HELLO. What to Do When a Child Won’t Eat

Spring 2021

Will You Pass the Peas, Please?

Farm to Early Care and Education: Growing Healthy Eaters, Classrooms, and Communities

Healthy Habits

Science, Nutrition, and Safety

Browse Articles For Families By Topic

Ramps & Pathways: A Constructivist Approach to Physics With Young Children

Celebrating Hispanic Heritage and Eating Right with José-Luis Orozco

"I Helped Mama Too!" Cooking With a Tiny Helper

Healthy, Fit Families

"I Helped Mama Too!" Cooking with a Tiny Helper

How a Cooking Class Became a Lesson in Engaging Children

Buon Appetito: Sharing a Love of Food with Infants and Toddlers

Let’s Eat (Well)!

Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards; Guidelines for Early Care and Early Education Programs (3rd ed.)

30 Million Kids in American Schools Deserve Better Nutrition

In the news / 23 February 2023

A closer look at the USDA’s latest proposal on added sugars in school meals

As a Stanford Impact Labs postdoctoral fellow working closely with Dr. Anisha Patel at the Stanford School of Medicine, I focus my research on understanding how policies that facilitate a healthy food environment improve health and prevent the onset of noncommunicable diseases, with the potential to reduce health disparities.

When the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) announced its current proposal to limit added sugars in school meals, I sat down with Stanford Impact Labs’ Kate Green Tripp to discuss the implications.

In early February 2023, the USDA announced new nutrition standards for school meals. What is important to understand about this?

School meals currently serve about 30 million children between the ages of 5 and 18 in the U.S. The majority of these kids are low-income or at increased risk of food and nutrition insecurity. School meals were first introduced in 1946 with the aim of improving food security, which simply means access to food.

In 2010, the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act strengthened nutrition standards for school meals to improve not only food security but also nutrition security — in other words, access to healthy and nutritious food. These standards limit the amount of salt, fat, and calories in school meals and standardize other requirements, such as ensuring that meals include whole grains, fruit, and vegetables. Yet no standard currently limits added sugar in school meals. The need for such a check has become urgent because research shows that school meals exceed the daily limit recommendation of added sugars per day.

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) recommend consuming less than 10% of total daily calories from added sugar, and the American Heart Association recommends limiting added sugar to less than 25 grams (~6 teaspoons) per day. On Feb. 3, 2023, the USDA announced a new proposed rule on nutrition standards for school meals, which established a reduction of sodium and the first-ever limit on added sugars in school meals, in alignment with the DGA. If these new nutrition standards are implemented, school meals will be required to limit added sugar to less than 10% of total calories per day.

What does the average school meal look like now, specifically when it comes to sugar content?

Anecdotally, we know school meals have a lot of sugar, though few studies have evaluated the added sugar content. One study that assessed the amount of added sugars in school meals in 2014-2015 found that 92% of schools exceeded the limit recommendation (less than 10% of calories) in school breakfasts. The same study found that 67% of schools exceeded the limit recommendation in school lunches.

At the end of 2020, Dr. Anisha Patel , associate professor at Stanford — in partnership with Cultiva La Salud, the Dolores Huerta Foundation, and the UC Nutrition Policy Institute — performed a photovoice study to evaluate the perception of school meals among parents in elementary schools in the San Joaquin Valley.

At that time, schools were operating virtually because of the COVID-19 pandemic, but parents were allowed to pick up meals for their kids. For this study, parents were asked to take photos of the foods they received, and then in focus groups, they discussed their perception of the meals. One topic parents discussed was the healthfulness of the meals. In particular, parents perceived that school meals were “ full of sugar . ¨ Working alongside two student interns in Dr. Patel’s lab — Jonathan Tyes, a medical student at the University of Louisville, and Brandon Cortes, a high school student — I used the photographs that parents provided to quantitatively evaluate the amount of added sugar in school meals.

We found that parents’ instincts were right: School meals are high in added sugar, and on average, school meals contain eight teaspoons (33 grams) of added sugars per day, which is two more teaspoons than the American Heart Association recommends as a daily limit. Like the previous study, we identified that the top sources of added sugar were items that are commonly consumed at breakfast, such as flavored milk, yogurt, pastries, bread, and dry fruit. We discovered some cases in which a single breakfast of a blueberry muffin, dry fruit, and low-fat milk provided up to 10 teaspoons of added sugar — almost twice the daily limit, all in one dose as a child’s start to the day.

What do we know about the health effects of sugar on school-age kids?

Added sugar is associated with many adverse health outcomes. For example, in the short term, sugar increases the risk of tooth cavities . Added sugar is the leading cause of tooth decay in children, and high added sugar consumption in children is associated with excess weight gain, which increases the risk of being overweight or obese. Added sugar is also associated with cardiovascular risk factors in children, such as lipid alterations, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and high blood pressure. In overweight or obese children, a high intake of added sugar is also associated with insulin resistance.

A closer look at nutrition in American kids reveals alarming numbers:

- Children in the U.S. consume an average of 17 teaspoons (70.8 grams) of added sugar per day.

- About 8 in 10 school-age children in the U.S. consume more than 10% of calories from added sugar.

- More than one-third of children in the U.S. meet the definition of overweight or obese .

- 1 in 5 adolescents have pre-diabetes .

- 1 in 5 children ages 6-11 and more than half of adolescents have experienced dental caries.

What will it take for the proposed standards to be implemented?

It is important to note that the USDA's proposed rule is simply that: a proposal. The USDA will receive public comments for 60 days before developing the final rule. If the proposed rule doesn’t change, the policy will not be fully implemented until the 2027-2028 school year to allow schools to adjust to the necessary change s. In the meantime, in the 2025-2026 school year, the amount of added sugar will be limited on items that are the primary sources of added sugars in school meals, such as grain-based desserts (no more than 2 oz equivalents/week), breakfast cereals (no more than 6 grams/oz), yogurt (no more than 12 grams/6 oz), and flavored milk (no more than 10 grams/8 oz).

I would like to see this policy be implemented sooner rather than later with stricter standards, but I am hopeful and recognize this as a huge step in the right direction. However, I anticipate the proposal will see a lot of pushback from the food industry, which is known for using a variety of tactics to prevent and delay health policies that could affect their economic interests. That makes this a particularly critical moment for children's health advocates to submit comments supporting these standards and to remain vigilant until the standards are fully implemented.

In other exciting news, California is also considering passing a bill that would limit added sugar in school meals based on the American Heart Association recommendation of less than 25 grams/day. If this bill passes, California will be the first state to have stricter added-sugar criteria, and this measure will likely be implemented sooner than the USDA standard.

Share this In the news

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Childhood Nutrition Facts

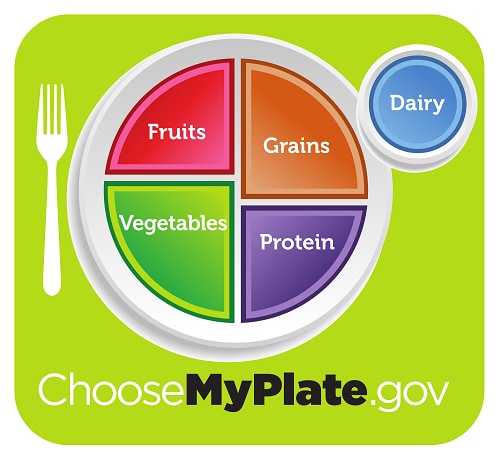

Healthy eating in childhood and adolescence is important for proper growth and development and to prevent various health conditions. 1,2 The Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025 recommend that people aged 2 years or older follow a healthy eating pattern that includes the following 2 :

- A variety of fruits and vegetables.

- Whole grains.

- Fat-free and low-fat dairy products.

- A variety of protein foods.

These guidelines also recommend that individuals limit calories from solid fats (major sources of saturated and trans fatty acids) and added sugars, and reduce sodium intake. 2 Unfortunately, most children and adolescents do not follow the recommendations set forth in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans . 2–4

Healthy eating can help individuals achieve and maintain a healthy body weight, consume important nutrients, and reduce the risk of developing health conditions such as 1,2

- High blood pressure.

- Heart disease.

- Type 2 diabetes.

- Osteoporosis.

- Iron deficiency.

- Dental caries (cavities).

The US Department of Agriculture provides healthy eating plans through MyPlate.gov .

- Schools are in a unique position to provide students with opportunities to learn about and practice healthy eating behaviors. 15

- Eating a healthy breakfast is associated with improved cognitive function (especially memory), reduced absenteeism, and improved mood. 16–18

- Adequate hydration may also improve cognitive function in children and adolescents, which is important for learning. 19–23

- Between 2001 and 2010, consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages among children and adolescents decreased, but still accounts for 10% of total caloric intake. 10

- Between 2003 and 2010, total fruit intake and whole fruit intake among children and adolescents increased. However, most youth still do not meet fruit and vegetable recommendations. 11,12

- Empty calories from added sugars and solid fats contribute to 40% of daily calories for children and adolescents age 2–18 years—affecting the overall quality of their diets. Approximately half of these empty calories come from six sources: soda, fruit drinks, dairy desserts, grain desserts, pizza, and whole milk. 4 Most youth do not consume the recommended amount of total water. 13

- CDC School Nutrition Environment

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025

- National Cancer Institute’s Risk Factor Monitoring and Methods: Food Sources Data on US dietary intake of the top food sources

- School Health Guidelines to Promote Healthy Eating and Physical Activity

- Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Agriculture . Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2015.

- US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans . 8th Edition. December 2015. Available at http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/ .

- Krebs-Smith SM, Guenther PM, Subar AF, et al. Americans do not meet federal dietary recommendations. Journal of Nutrition. 2010;140:1832–1838.

- Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Dietary Sources of Energy, Solid fats, and added sugars among children and adolescents in the united States. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2010;110:1477–1484.

- Institute of Medicine. Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press ; 2004.

- Kushi LH, Byers T, Doyle C, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention: Reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2006;56:254–281.

- Kaiser LL, Townsend MS. Food insecurity among US children: Implications for nutrition and health. Topics in Clinical Nutrition. 2005;20:313–320.

- Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA. Food insufficiency and American school-aged children’s cognitive, academic and psychosocial developments. Pediatrics ,2001;108:44–53.

- Kleinman RE, Murphy JM, Little M, et al. Hunger in children in the United States: Potential behavioral and emotional correlates. Pediatrics, 1998;101:1–6.

- Mesirow MA, Welsh JA. Changing beverage consumption patterns have resulted in fewer liquid calories in the diets of US children: National health and nutrition examination survey 2001–2010. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics . 2015;115(4):559–66.

- Kim SA, Moore LV, Galuska D, et al. Vital Signs: Fruit and vegetable intake among children—United States, 2003–2010. MMWR . 2014; 63(No. RR-31):671–6.

- Drewnowski A, Rehm CD. Socioeconomic gradient in consumption of whole fruit and 100% fruit juice among US children and adults. Nutr J. 2015;14:3.

- Drewnowski A, Rehm CD, Constant F. Water and beverage consumption among children age 4–13 years in the United States: Analyses of 2005–2010 NHANES data. Nutr J. 2013;12(1):85.

- US Department of Agriculture. MyPlate.gov .

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. School health guidelines to promote healthy eating and physical activity. MMWR . 2011;60(RR05):1–76.

- Taras HL. Nutrition and student performance at school. Journal of School Health. 2005;75:199–213.

- Rampersaud GC, Pereira MA, Girard BL, et al. Breakfast habits, nutritional status, body weight, and academic performance in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2005;105:743–760.

- Hoyland A, Dye L, Lawton CL. A systematic review of the effect of breakfast on the cognitive performance of children and adolescents. Nutrition Research Reviews. 2009;22:220–243.

- Popkin BM, D’Anci KE, Rosenberg IH. Water, hydration, and health. Nutrition Reviews. 2010;68(8):439–458.

- Kempton MJ, Ettinger U, Foster R, et al. Dehydration affects brain structure and function in healthy adolescents. Human Brain Mapping. 2011;32:71–79.

- Edmonds CJ, Jeffes B. Does having a drink help you think? 6 to 7-year-old children show improvements in cognitive performance from baseline to test after having a drink of water. Appetite. 2009;53:469–472.

- Edmonds CJ, Burford D. Should children drink more water? The effects of drinking water on cognition in children. Appetite. 2009;52:776–779.

- Benton D, Burgess N. The effect of the consumption of water on the memory and attention of children. Appetite. 2009;53:143–146.

Healthy Youth

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PMC10674981

Nutrition and Food Literacy: Framing the Challenges to Health Communication

Paula silva.

1 Laboratory of Histology and Embryology, Department of Microscopy, School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences (ICBAS), University of Porto (U.Porto), Rua Jorge Viterbo Ferreira 228, 4050-313 Porto, Portugal

2 iNOVA Media Lab, ICNOVA-NOVA Institute of Communication, NOVA School of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, 1069-061 Lisbon, Portugal

Rita Araújo

3 Departamento de Artes e Humanidades, Escola Superior de Comunicação, Administração e Turismo, Instituto Politécnico de Bragança, Campus do Cruzeiro—Avenida 25 de Abril, Cruzeiro, Lote 2, Apartado 128, 5370-202 Mirandela, Portugal; [email protected]

Felisbela Lopes

4 Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade, Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade do Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal; tp.ohnimu.sci@alebsilef

Sumantra Ray

5 NNEdPro Global Institute for Food, Nutrition & Health, Cambridge CB4 0WS, UK; [email protected]

6 School of Biomedical Sciences, Ulster University at Coleraine, Coleraine BT52 1SA, UK

7 Fitzwilliam College, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 0DG, UK

Associated Data

Not applicable.

Nutrition and food literacy are two important concepts that are often used interchangeably, but they are not synonymous. Nutrition refers to the study of how food affects the body, while food literacy refers to the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to make informed decisions about food and its impact on health. Despite the growing awareness of the importance of food literacy, food illiteracy remains a global issue, affecting people of all ages, backgrounds, and socioeconomic status. Food illiteracy has serious health implications as it contributes to health inequities, particularly among vulnerable populations. In addition, food literacy is a complex and multidisciplinary field, and there are numerous challenges to health communication that must be addressed to effectively promote food literacy and improve health outcomes. Addressing food illiteracy and the challenges to health communication is essential to promote health equity and improve health outcomes for all populations.

1. Introduction

The world is becoming increasingly complex. It is hard to keep up with everything that is going on in the news, let alone all the information needed to know just to navigate your day-to-day life. Every day, people worldwide feel confused about what to eat for health. People look for science-based information but struggle with the vast amount of information and do not know what to believe. People feel that scientists do not agree with each other and are constantly changing their minds. With so much information about what people should eat and how much exercise they should do each day, it can be difficult for even the most educated people to sort through it all, and this confusion can lead them to make unhealthy choices when they are not aware of what they are doing [ 1 , 2 ]. In the first part of the paper, we attempted to clarify the differences between nutrition and food literacy, which are often wrongly used as synonyms. We explored food illiteracy as a major global issue that leads to poor health outcomes and even death [ 3 ]. Food illiteracy also promotes health inequities, especially if it is combined with other factors such as poverty and a lack of access to fresh foods or proper nutrition education programs [ 4 ]. Food literacy is an important aspect of health literacy because it helps individuals make informed decisions about what they eat and how it affects their health [ 2 ]. In a world where processed and fast foods are often more convenient and accessible than nutritious options [ 5 ], having food literacy can make a big difference in a person’s overall health and well-being. It can also help to prevent chronic health conditions such as obesity, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes, which are often related to poor diet and nutrition [ 6 ]. In the last part of the paper, we explain how food literacy must be framed in the context of health literacy, the importance of both knowledge and skills in food and nutrition, and the broader understanding of health and wellness that is necessary for individuals to make informed choices and decisions about their health.

We conducted a literature review to provide an overview of the challenges to health communication concerning nutrition and food literacy. The results are presented as a topical review. We would like to emphasize that this manuscript constitutes a literature review that offers a comprehensive summary of the research findings gathered from diverse sources. Its purpose is to present a holistic overview of existing research on a specific topic without strictly adhering to rigorous systematic review methodologies, such as a formal systematic search strategy or strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. Scopus and Web of Science were used to conduct the search. Multiple search terms were used, including “nutrition literacy”, “food literacy”, “nutritional literacy”, “health literacy”, “health communication”, and “science communication”. Only reports written in English were considered, regardless of whether they were published. A strategy known as “pearl-fishing” or “chaining” chaining’ was employed to identify relevant research articles. This involved a thorough examination of references in other articles, as well as recent articles that cited older, pertinent articles. The selection was limited to papers published in English in peer-reviewed journals and book chapters. Initially, the abstracts were reviewed to gauge their relevance, resulting in the identification of 215 papers. Each of these studies was meticulously studied and analyzed. This process led to the discovery of additional pertinent references, resulting in the inclusion of 161 additional relevant papers in this comprehensive review.

3. Health, Nutrition, and Food Literacy

According to Scopus and Web of Science, nutrition literacy appeared first in the title of a scientific document in 1995 in a study carried out by Sullivan and Gottschall-Pass that was carried out to assess the food label nutrition knowledge of healthy Canadians, i.e., to evaluate their nutrition literacy [ 7 ]. Nutrition literacy continued to be used without a specific definition; it was used under the umbrella of the more general term health literacy. The definition of nutrition literacy evolved from the tripartite model of health literacy developed by Don Nutbeam, who defined it as a set of cognitive and social abilities that affect an individual’s motivation and capacity to access, understand, and manage information that allows the promotion and maintenance of a healthy status. According to this definition, health literacy is more than being able to read package inserts or being successful in appointments and exam schedules, rather it is being able to make informed decisions [ 8 ].

Don Nutbeam [ 8 ] identified three health literacy levels: functional, communicative/interactive, and critical. A functional or basic level of health literacy implies knowing how to read and write, understanding simple health messages, and being able to act according to the health information provided. The functional level highlights the importance of knowing health risks, health services, and a set of healthcare recommendations. This includes understanding the labelling of prescription drugs and the ability to read instructions for taking prescription medication. This information is usually distributed to the public through leaflets as the objective is to obtain global benefits [ 8 ]. The communicative/interactive level involves a more advanced cognitive level and developed skills that allow individuals to seek and use health information to respond to changing needs. At this level, the focus is on improving individual capacities such as lifestyle changes and the effective use of health services. It also involves the ability to discuss information with health professionals to make informed decisions [ 8 ]. For example, it includes understanding a treatment option and how that treatment compares with other options. The most advanced level is critical literacy, which implies an even more advanced cognitive level that allows the individual to critically analyze health information and use the results of their analysis to be alert and thus acquire control over their life events [ 8 ]. However, the definition of these three levels of health literacy has some limitations. They only apply to literate communities and assume that a high level of education corresponds to a high level of health literacy and that this is a prerequisite or guarantee that the person will respond in the desired way, which may not correspond to reality [ 9 ].

Nutrition and food literacy are two linked concepts related to the ability to understand and apply knowledge about food. Understanding the differences between these concepts is crucial. Definitions in the literature are presented in Table 1 . Briefly, nutrition literacy (sometimes mentioned as nutritional literacy) has to do with understanding the role of various nutrients in healthy eating, as well as how to read nutrition labels and make healthy food choices. Food literacy focuses more on the social aspects of food: how it is produced, where it comes from, who grows it, and how these things affect our health.

Nutrition and food literacy definitions found in the literature.

| “Nutritional literacy, as a specific form of health literacy, requires both general literacy and computational skill. It is not surprising to find that higher levels of nutrition knowledge have been associated with nutrition label use.” | Blitstein, J.L.; Evans, W.D. Use of Nutrition Facts Panels among Adults Who Make Household Food Purchasing Decisions. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 2006, 38, 360–364, doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2006.02.009. (p. 1) |

| “Adequate health literacy and nutrition literacy require an individual not only to read well, but also to understand health and nutrition concepts and to have basic quantitative skills (defined as numeracy: the ability to use and understand numbers in daily life, including the ability to read and interpret nutrition information. People without these skills may have difficulty understanding concepts of healthful diets, reading nutrition information, and measuring a portion size.” | Neuhauser, L.; Rothschild, R.; Rodríguez, F.M. MyPyramid.gov: Assessment of Literacy, Cultural and Linguistic Factors in the USDA Food Pyramid Web Site. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 2007, 39, 219–225, doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2007.03.005. (p. 220) |

| “Nutrition literacy can be defined similarly to health literacy as the degree to which individuals can obtain, process, and understand the basic health (nutrition) information and services they need to make appropriate health (nutrition) decisions, with the qualification that the definition is nutrition-specific.” | Silk, K.J.; Sherry, J.; Winn, B.; Keesecker, N.; Horodynski, M.A.; Sayir, A. Increasing Nutrition Literacy: Testing the Effectiveness of Print, Web site, and Game Modalities. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 2008, 40, 3–10, doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2007.08.012. (p. 4) |

| “Nutrition literacy may be defined as the degree to which people have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic nutrition information.” | Zoellner, J.; Connell, C.; Bounds, W.; Crook, L.; Yadrick, K. Nutrition literacy status and preferred nutrition communication channels among adults in the lower Mississippi Delta. Preventing Chronic Disease 2009, 6, doi:19755004. (p. 2) |

| “In other words, at what point is this client no longer dependent on expert knowledge? When do his or her food choices reflect what is right for him or her 80% to 90% of the time? That is when the person achieves nutrition literacy. Fortunately, the term can and should be individualized according to the goals set at the beginning of the relationship. When that individual says, “I can do this on my own”, the dietetics practitioner will have succeeded.” | Escott-Stump, S.A. Our nutrition literacy challenge: Making the 2010 dietary guidelines relevant for consumers. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2011, 111, 979, doi:10.1016/j.jada.2011.05.024. (p. 979) |

| “…‘nutrition literacy’ can mean the extent to which people access, understand and use nutrition information. In this context, consumers’ nutrition literacy is critical in their interpretation of noninterpretative front-of-pack food labelling and menu labelling.” | Watson, W.L.; Chapman, K.; King, L.; Kelly, B.; Hughes, C.; Yu Louie, J.C.; Crawford, J.; Gill, T.P. How well do Australian shoppers understand energy terms on food labels? Public Health Nutrition 2013, 16, 409–417, doi:10.1017/s1368980012000900. (p. 410) |

| “Functional nutrition literacy refers to proficiency in applying basic literacy skills, such as reading and understanding food labelling and grasping the essence of nutrition information guidelines. Interactive nutrition literacy comprises more advanced literacy skills, such as the cognitive and interpersonal communication skills needed to interact appropriately with nutrition counsellors, as well as interest in seeking and applying adequate nutrition information for the purpose of improving one’s nutritional status and behaviour. Critical nutrition literacy refers to being proficient in critically analyzing nutrition information and advice, as well as having the will to participate in actions to address nutritional barriers in personal, social, and global perspectives. CNL is part of scientific literacy– ‘the capacity to use scientific knowledge, to identify questions and to draw evidence-based conclusions’ i.e., proficiency in describing, explaining and predicting scientific phenomena, and understanding the processes of scientific inquiries as well as the premises of scientific evidence and conclusion.” | Guttersrud, O.; Dalane, J.O.; Pettersen, S. Improving measurement in nutrition literacy research using Rasch modelling: Examining construct validity of stage-specific ‘critical nutrition literacy’ scales. Public Health Nutrition 2014, 17, 877–883, doi:10.1017/S1368980013000530. (p. 887) |

| “Nutrition literacy focuses mainly on abilities to understand nutrition information, which can be seen as a prerequisite for a wider range of skills described under the term food literacy. Thus, nutrition literacy can be seen a subset of food literacy.” | Krause, C.; Sommerhalder, K.; Beer-Borst, S.; Abel, T. Just a subtle difference? Findings from a systematic review on definitions of nutrition literacy and food literacy. Health Promotion International 2016, 33, 378–389, doi:10.1093/heapro/daw084. (p. 387) |

| “We defined food literacy as the capacity of an individual to obtain, interpret and understand basic food and nutrition information and services and the competence to use that information and services in ways that are health-enhancing. This definition was derived from the accepted definition of health literacy…” | Kolasa, K.M.; Peery, A.; Harris, N.G.; Shovelin, K. Food Literacy Partners Program: A Strategy To Increase Community Food Literacy. Topics in Clinical Nutrition 2001, 16, 1–10. (p. 5) |

| “…food literacy as more than knowledge; it also involves the motivation to apply nutrition information to food choices. Whereas food knowledge is the possession of food-related information, food literacy entails both understanding nutrition information and acting on that knowledge in ways consistent with promoting nutrition goals and “food well-being”.” | Block, L.G.; Grier, S.A.; Childers, T.L.; Davis, B.; Ebert, J.E.J.; Kumanyika, S.; Laczniak, R.N.; Machin, J.E.; Motley, C.M.; Peracchio, L.; et al. From nutrients to nurturance: A conceptual introduction to food well-being. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing 2011, 30, 5–13, doi:10.1509/jppm.30.1.5. (p. 7) |

| “…expands traditional measures of nutrition knowledge to include not only what people know about food but their ability to use that information to facilitate higher levels of food well-being. Food literacy ranges from declarative types of knowledge (e.g., knowing what asparagus is and what types of the nutrients asparagus might provide) to procedural knowledge (e.g., how to cook this vegetable).” | Bublitz, M.G.; Peracchio, L.A.; Andreasen, A.R.; Kees, J.; Kidwell, B.; Miller, E.G.; Motley, C.M.; Peter, P.C.; Rajagopal, P.; Scott, M.L. The quest for eating right: Advancing food well-being. Journal of Research for Consumers 2011, 1. (pp. 3–4) |

| “Food literacy was seen mainly as an individual’s ability to read, understand, and act upon labels on fresh, frozen, canned, frozen, processed, and takeout food.” | Fordyce-Voorham, S. Identification of essential food skills for skill-based healthful eating programs in secondary schools. J Nutr Educ Behav 2011, 43, 116–122, doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2009.12.002. (p. 119) |

| “I take the inspiration for food literacy from the notions of ‘health literacy’ in public health literature. The concept was born out of public health policy’s endeavor to educate people to seek healthier lifestyles and adhere to prescribed advice and was used to explain ‘the relationship between the patient literacy levels and their ability to comply with prescribed therapeutic regimens’.” | Kimura, A.H. Food education as food literacy: Privatized and gendered food knowledge in contemporary Japan. Agriculture and Human Values 2011, 28, 465–482, doi:10.1007/s10460-010-9286-6. (p. 479) |

| “Food literacy is the ‘capacity of an individual to obtain, interpret and understand basic food and nutrition information and services as well as the competence to use that information and available services that are health enhancing.’” | Pendergast, D.; Garvis, S.; Kanasa, H. Insight from the Public on Home Economics and Formal Food Literacy. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 2011, 39, 415–430, doi:10.1111/j.1552-3934.2011.02079.x. (p. 418) |

| “…the relative ability to basically understand the nature of food and how it is important to you, and how able you are to gain information about food, process it, analyze it and act upon it.” | Vidgen, H.A.; Gallegos, D. What is food literacy and does it influence what we eat: a study of Australian food experts. 2011. (p. ii) |

| “… a complex, interrelated, person-centred set of skills that are necessary to provide and prepare safe, nutritious, and culturally-acceptable meals for all members of one’s household.” | Thomas, H.M.; Irwin, J.D. Cook It Up! A community-based cooking program for at-risk youth: Overview of a food literacy intervention. BMC Research Notes 2011, 4, 495, doi:10.1186/1756-0500-4-495. (p. 6) |

| “A collection of inter-related knowledge, skills and behaviours required to plan, manage, select, prepare and eat foods to meet needs and determine food intake. Food literacy is the scaffolding that empowers individuals, households, communities or nations to protect diet quality through change and support dietary resilience over time.” | Vidgen, H.A.; Gallegos, D. Defining food literacy, its components, development and relationship to food intake: A case study of young people and disadvantage. 2012. (p. vii) |

| “…the capacity of an individual to obtain, process and understand basic food information about food and nutrition as well as the competence to use that information in order to make appropriate health decisions.” | Murimi, M.W. Healthy literacy, nutrition education, and food literacy. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 2013, 45, 195, doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2013.03.014. (p. 195) |

| “…focuses on food and nutrition information to help individuals make appropriate eating decisions.” | Rawl, R.; Kolasa, K.M.; Lee, J.; Whetstone, L.M. A Learn and Serve Nutrition Program: The Food Literacy Partners Program. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 2008, 40, 49–51, doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2007.04.372. (p. 49) |

| “…a set of skills and attributes that help people sustain the daily preparation of healthy, tasty, affordable meals for themselves and their families. Food literacy builds resilience, because it includes food skills (techniques, knowledge and planning ability), the confidence to improvise and problem-solve, and the ability to access and share information. Food literacy is made possible through external support with healthy food access and living conditions, broad learning opportunities, and positive socio-cultural environments.” | Desjardins, E. Making Something out of Nothing: Food Literacy Among Youth, Young Pregnant Women and Young Parents Who are at Risk for Poor Health. A Locally Driven Collaborative Project. 2013. At: (accessed on 23 January 2023) (p. 70) |

| “Food literacy can be defined as an individual’s food related knowledge, attitudes, and skills. This broad definition of food literacy incorporates household perception, assessment, and management of the risks associated with their food choices. Individuals’ food literacy level influences their food-related decisions, which ultimately impact their diet and health as well as the environment.” | Howard, A.; Brichta, J. What’s to Eat?: Improving Food Literacy in Canada. 2013. (p. 2) |

| “Food literacy is the ability to “read the world” in terms of food, thereby recreating it and remaking ourselves. It involves a full-cycle understanding of food—where it is grown, how it is produced, who benefits and who loses when it is purchased, who can access it (and who can’t), and where it goes when we are finished with it. It includes an appreciation of the cultural significance of food, the capacity to prepare healthy meals and make healthy decisions, and the recognition of the environmental, social, economic, cultural, and political implications of those decisions.” | Sumner, J. Food literacy and adult education: Learning to read the world by eating. Canadian Journal for the Study of Adult Education 2013, 25, 79–92. (p. 86) |

| “Functional food literacy: basic communication of credible, evidence-based food and nutrition information, involving accessing, understanding and evaluating information. Interactive food literacy: development of personal skills regarding food and nutrition issues, involving decision making, goal setting and practices to enhance nutritional health and well-being Critical food literacy: respecting different cultural, family and religious beliefs in respect to food and nutrition (including nutritional health), understanding the wider context of food production and nutritional health, and advocating for personal, family and community changes that enhance nutritional health.” | Slater, J. Is cooking dead? The state of Home Economics Food and Nutrition education in a Canadian province. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2013, 37, 617–624, doi:10.1111/ijcs.12042. (p. 623) |

| “Food literacy is the scaffolding that empowers individuals, households, communities or nations to protect diet quality through change and strengthen dietary resilience over time. It is composed of a collection of inter-related knowledge, skills and behaviours required to plan, manage, select, prepare and eat food to meet needs and determine intake.” | Vidgen, H.A.; Gallegos, D. Defining food literacy and its components. Appetite 2014, 76, 50–59, doi:10.1016/j.appet.2014.01.010. (p. 54) |

| “Food literacy is the ability of an individual to understand food in a way that they develop a positive relationship with it, including food skills and practices across the lifespan in order to navigate, engage, and participate within a complex food system. It’s the ability to make decisions to support the achievement of personal health and a sustainable food system considering environmental, social, economic, cultural, and political components.” | Cullen, T.; Hatch, J.; Martin, W.; Higgins, J.W.; Sheppard, R. Food literacy: Definition and framework for action. Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice and Research 2015, 76, 140–145, doi:10.3148/cjdpr-2015-010. (p. 143) |

| “We suggest using the term food literacy instead of nutrition literacy to describe the wide range of skills needed for a healthy and responsible nutrition behaviour. When measuring food literacy, we suggest the following core abilities and skills be taken into account: reading, understanding, and judging the quality of information; gathering and exchanging knowledge related to food and nutrition themes; practical skills like shopping and preparing food; and critically reflecting on factors that influence personal choices about food, and understanding the impact of those choices on society.” | Krause, C.; Sommerhalder, K.; Beer-Borst, S.; Abel, T. Just a subtle difference? Findings from a systematic review on definitions of nutrition literacy and food literacy. Health Promotion International 2016, 33, 378–389, doi:10.1093/heapro/daw084. (p. 387) |

| “‘food literacy’ encompasses a more holistic approach to describe the practicalities needed to meet nutrition recommendations: plan, management, selection, preparation, and consumption.” | Garcia, A.L.; Reardon, R.; McDonald, M.; Vargas-Garcia, E.J. Community Interventions to Improve Cooking Skills and Their Effects on Confidence and Eating Behaviour. Current Nutrition Reports 2016, 5, 315–322, doi:10.1007/s13668-016-0185-3. (p. 316) |

| “…food literacy is a complex phenomenon made up of multiple attributes, including those that are both intrinsic and extrinsic. By conceptualizing these attributes, the results of the present scoping review provide the foundation for the development of a measurement tool that can support monitoring and the evaluation of interventions to support food literacy.” | Perry, E.A.; Thomas, H.; Samra, H.R.; Edmonstone, S.; Davidson, L.; Faulkner, A.; Petermann, L.; Manafò, E.; Kirkpatrick, S.I. Identifying attributes of food literacy: A scoping review. Public Health Nutrition 2017, 20, 2406–2415, doi:10.1017/S1368980017001276. (p. 2413) |

| “Food Literacy (FL) is the combination of knowledge, skills, and behaviours required to plan, select, manage, prepare, and consume foods that meet nutritional recommendations. Understood to be an important component of healthy living, FL is associated with confidence, autonomy, and empowerment towards food.” | Bomfim, M.C.C.; Wallace, J.R. Pirate bri’s grocery adventure: Teaching food literacy through shopping. In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems—Proceedings, 2018., (p. 2) |

Nutrition literacy is the level to which people can acquire, process, and comprehend the fundamental nutritional data and services that they need to make correct dietary decisions [ 10 ]. This implies having the knowledge of nutritional principles and the ability to understand, analyze, and use nutritional information; that is, to know the nutrients and their health effects [ 11 ]. It involves an individual’s capacity to acquire, understand, and use nutritional information from several sources [ 12 ]. This includes knowing how foods are digested, their relationship with health, and how to use this information to make healthy choices.

Having nutrition literacy may not be sufficient to achieve the desired well-being and health. It is necessary to have food literacy; that is, to have knowledge, skills, and behaviors that are interrelated and that are necessary to decide, handle, choose, cook, and eat food [ 13 , 14 , 15 ]. Food literacy is an individual’s ability to make decisions that lead to better individual health status and lead to a sustainable food system considering all social, environmental, cultural, economic, and political factors [ 16 ]. Krause et al. (2016) defined nutrition literacy as a subfield of food, with both being specific dimensions of health literacy [ 17 ]. According to the authors, nutrition and food literacy are different but complementary concepts. The main difference lies in the skills needed to be literate in nutrition, food, or health. Thus, nutrition literacy consists of the ability to understand basic nutritional information, which is a requirement for a broader array of skills defined for food literacy. The authors suggest the use of food literacy instead of nutrition literacy as it is broader and includes the skills necessary for healthy and responsible eating behavior [ 17 ].

Vidgen (2016) identified eight domains of food literacy: (1) access; (2) management and planning; (3) selection; (4) knowledge of food origin; (5) preparation; (6) eating; (7) nutrition; and (8) language [ 18 ]. Truman et al. (2017) expanded the components of the definition of food literacy by considering six core themes: (1) capabilities and behaviors; (2) healthy food and choices; (3) culture; (4) knowledge; (5) emotions; and (6) food systems [ 15 ].

Food literacy measurement involves evaluating the following skills: reading, understanding, and analyzing information; gathering and sharing nutrition and food knowledge; shopping and preparing food; and evaluating the factors that impact their individual food choices and their influence on society [ 17 ].

Vettori et al. (2019) highlight the importance of evaluating the skills needed to access and adhere to a healthy diet when measuring nutrition and food literacy [ 19 ]. A nutrition and food-literate community includes people who eat to ensure their health and well-being while ensuring a sustainable food system. Nutrition and food literacy reflect the individual’s inspiration to adopt suitable behaviors and healthy food choices for oneself, others, and the environment [ 19 ].

Health, food, and nutrition literacy are critical factors that impact every level of prevention in health and disease ( Figure 1 ). Primary prevention refers to actions taken to prevent the disease onset. Health literacy is essential in promoting healthy lifestyles and behaviors that can prevent chronic diseases. Eating a healthy diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins can reduce the risk of developing conditions like heart disease, diabetes, and certain types of cancer. Education about the importance of a balanced diet and how to read nutrition labels can also help people make healthier food choices [ 20 , 21 ]. Secondary prevention refers to actions taken to detect and treat a disease early before it causes significant harm. Food and nutrition literacy is critical in secondary prevention because it enables individuals to make informed decisions about their diet and lifestyle to manage chronic conditions such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and diabetes. For example, individuals with food and nutrition literacy may be able to modify their diet to reduce their risk of developing complications from these conditions [ 20 ]. Finally, tertiary prevention focuses on managing the complications and symptoms of chronic diseases. Health literacy is essential in tertiary prevention because it enables individuals to understand their condition and adhere to their treatment plan. Education about how to read food labels, plan meals, and cook healthy foods can help these individuals better manage their condition and prevent complications [ 20 ].

Health, nutrition, and food literacy play a critical role in the prevention and management of diseases across all stages of prevention. The authors acknowledge NNEdPro for the figure conceptualization.

A comprehensive understanding of nutrition literacy is imperative in today’s complex world. It should not be isolated from the two other critical components of health and food literacy. This integration is of paramount importance in providing individuals with a comprehensive understanding of how their dietary choices affect their overall health and broader societal and economic well-being. Health literacy emphasizes the importance of informed decision making in health matters. Food literacy extends health literacy scope to include the social, cultural, economic, and environmental dimensions of food. This broader understanding of nutrition literacy extends beyond simply acquiring knowledge and interpreting food labels. It serves as a reminder that nutrition literacy encompasses a wider social, cultural, and political context, operating at personal, interpersonal, and societal levels. The inclusion of these elements in nutrition literacy helps individuals make healthier food choices and appreciates the wider implications of their dietary decisions. Therefore, a comprehensive conception of nutrition literacy ought to incorporate crucial components of both health and food literacy to provide individuals with a comprehensive understanding of the significance of nutrition in their lives. It is not simply a matter of knowing what to consume; it also involves understanding the rationale behind its significance and integration into the broader context of health and sustainability. This comprehensive approach has the potential to lead to healthy individuals and a sustainable global community [ 12 ].

4. The Emergence of Food Illiteracy as a Global Issue

The increase in non-communicable diseases related to unhealthy lifestyle habits, including diet, is usually related to food illiteracy increase [ 22 , 23 ]. The latter could be explained by the lack of knowledge about navigating the complex food system and ensuring regular food intake according to nutritional recommendations [ 19 ]. Food systems have become highly complex in the 21st century with the “nutrition transition”, characterized by the increase in variety, availability, and accessibility of processed and ultra-processed and low nutrient and energy-dense food [ 24 , 25 , 26 ]. This type of food is typically mass-produced and has a long shelf life. In addition, it is a very popular food type because it is heavily marketed and easily available in supermarkets, restaurants, and vending machines, or because it can be ordered on the Internet and consumed at home. Today, people have less time to prepare meals from scratch than ever before, which can lead them to consume unhealthy foods that are easy to prepare. The consumption of pre-prepared food and the increase in takeout meals reduces the time spent in the kitchen. Consequently, a decline in cooking and food preparation skills has been observed. As older people stop cooking, they miss the opportunity to teach younger people [ 24 , 26 , 27 ].

The emergence of food illiteracy as a global issue due to the modern lifestyle and diet of many people around the world is a serious problem [ 24 ]. Several factors contribute to food illiteracy, including a lack of access to education about healthy eating, lack of access to affordable healthy food, lack of time to cook healthy meals, lack of knowledge about how to prepare healthy meals, and high levels of stress, which can lead to unhealthy eating habits [ 28 ]. These determinants of health play a significant role in shaping food and health literacy [ 17 ]. They are crucial for governments when determining equity and resource allocations. Therefore, directing more funding towards increasing literacy, especially among disadvantaged groups, can be a key strategy in addressing the broader issue of food illiteracy and its associated health challenges.

Food illiteracy is a growing problem in many countries worldwide as people are exposed to misinformation about the food they consume and its effects on their health [ 29 ]. When people have a low level of food literacy, they may be unaware of how much salt or sugar is in their food or how many calories are in a serving. They may not know which ingredients are good or bad for them. They might not realize what types of foods they should eat more often or less often, based on their age or health status [ 30 , 31 , 32 ]. There are two types of food illiteracy: the first is when people do not know what certain foods are or how to prepare them, and the second is when people have a poor understanding of the nutritional value of different foods and do not know how to properly balance meals [ 28 ]. This lack of knowledge about what we eat has led to unprecedented rates of obesity and diabetes, which often lead to other health problems such as cardiovascular disease and kidney disease. Although many people know that diet plays a role in weight gain and obesity, they may not realize that diet also has an impact on diabetes [ 33 ]. Research has suggested that certain dietary habits can help reverse diabetes by enhancing insulin sensitivity and reducing blood sugar levels [ 34 ]. If the prevalence of obesity continues to increase, almost half of the world’s adult population will become overweight or obese by 2030 [ 35 ]. The government and health authorities have highlighted the health and social complications related to inappropriate dietary patterns [ 36 ].

Children’s food literacy rates are low. Many schools or day-cares do not provide students with healthy meals during school hours; instead, they rely on parents to pack lunches from home or provide snacks from vending machines that only offer sugary snacks such as chips or candy bars instead of healthier options such as fruits or yoghurt bars [ 37 ]. Early life stages represent an important period since lifelong habits are developed and life circumstances influence health outcomes in adulthood. The important social, emotional, and cognitive changes that occur during youth mean that there is a greater tendency to engage in risky behaviors during this life phase. Irresponsible eating habits can have negative health effects with individual, familial, and social consequences [ 38 ]. Therefore, improving healthy eating habits and lifestyles in the early stages of life is of major concern worldwide. Eating is a socially constructed practice that is important for understanding and pursuing health [ 39 ]. However, food and eating practices occupy a relatively minor place in the scholarship. Communication with the public is the initial stage of the behavior-change process and is a crucial piece of effective public policy [ 40 ]. To combat this problem, governments should invest more money in educating children about healthy eating habits at school so that they can make good choices throughout their lives [ 41 ].

Food illiteracy has also been shown to be a major contributor to food waste. Approximately one-third of all food produced worldwide is wasted, and this number continues to increase annually [ 42 ]. This is a problem because of wasted resources and can have serious health, social, economic, and environmental effects [ 43 ]. Food waste begins at home, where consumers often buy more than they need or want and then waste what is left over when they do so [ 44 ]. The health effects of food waste are numerous. For example, the loss of nutrients from discarded fruits and vegetables means that people who eat this food have a lower nutritional intake than those who do not [ 45 ]. Additionally, when food is discarded instead of eaten, it causes greenhouse gas emissions by rotting in landfills [ 46 , 47 ]. Food waste also has economic and environmental effects. If more fruits and vegetables are eaten rather than thrown away after reaching their expiration dates, more money would be saved by consumers who would not need to buy new produce. Moreover, people consume more processed foods than ever before, causing them to throw away more packaging [ 48 ]. However, there are other factors at play here too: climate change is causing droughts around the world, which means that crops are failing due to a lack of rain and heat stress on plants during ripening periods. The result is less food available for everyone, from farmers down to consumers, which means higher prices on produce at grocery stores which causes consumers to buy less healthy foods overall because they are too expensive for their budgets [ 49 ].

Measuring food literacy is of the utmost importance. According to a recent scoping review, there are now 12 tools available to assess adult food literacy. The authors found that even though most of them cover all four aspects of food literacy, theoretical frameworks are rarely applied. They also concluded that existing tools have only been tested in a few situations, and they mainly rely on biased self-reporting techniques [ 50 ]. The self-perceived food literacy scale (SPFL) and the short food literacy questionnaire (SFLQ) are the ones that have been validated in more countries [ 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 ]. Both primarily concentrate on individuals’ skills and competencies needed for making appropriate food choices [ 57 ]. The SPFL scale was created by Poelman et al. (2018) to measure adults’ food literacy concerning healthy diets, knowledge, skills, and behaviors necessary for the appropriate planning, management, selection, preparation, and consumption of food [ 53 ]. Despite limited application, generally, SPFL revealed that better food literacy was linked to better impulse control, less impulsive behavior, and healthier food consumption [ 53 ] and that adults with a low and medium level of education have a low food literacy level [ 58 ]. The relationship between Body Mass Index (BMI) and SPFL was also analyzed, and depending on the context, BMI may predict [ 52 , 59 ] or have no effect on the SPFL final score [ 58 ].

The SFLQ [ 57 ] scale has been used in food and nutrition intervention research to assess respondents’ functional, interactive, and critical food literacy abilities. Consumers in Italy who had received specialized education in human nutrition scored higher on the SFLQ and SPFL than those without this knowledge. Furthermore, the SFLQ scores were notably higher among women [ 59 ].

5. Food Literacy Health Inequities